User login

What’s Eating You? Carpet Beetles (Dermestidae)

Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

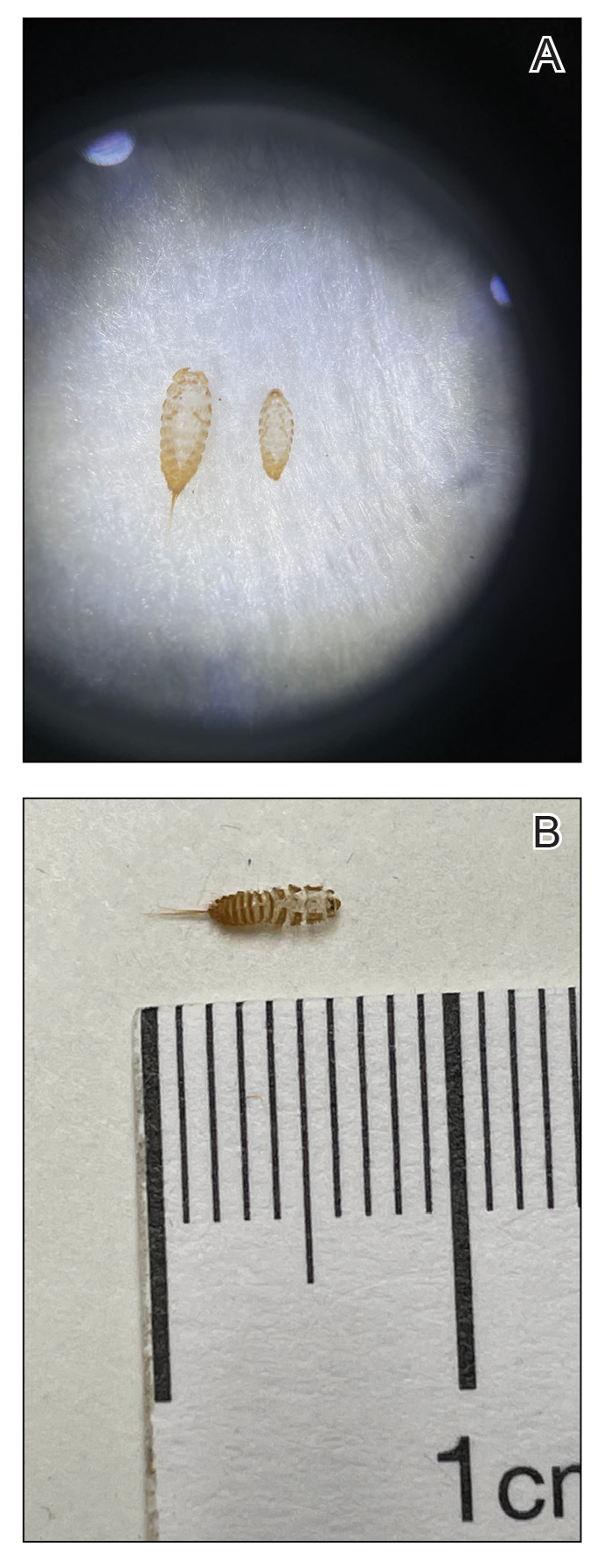

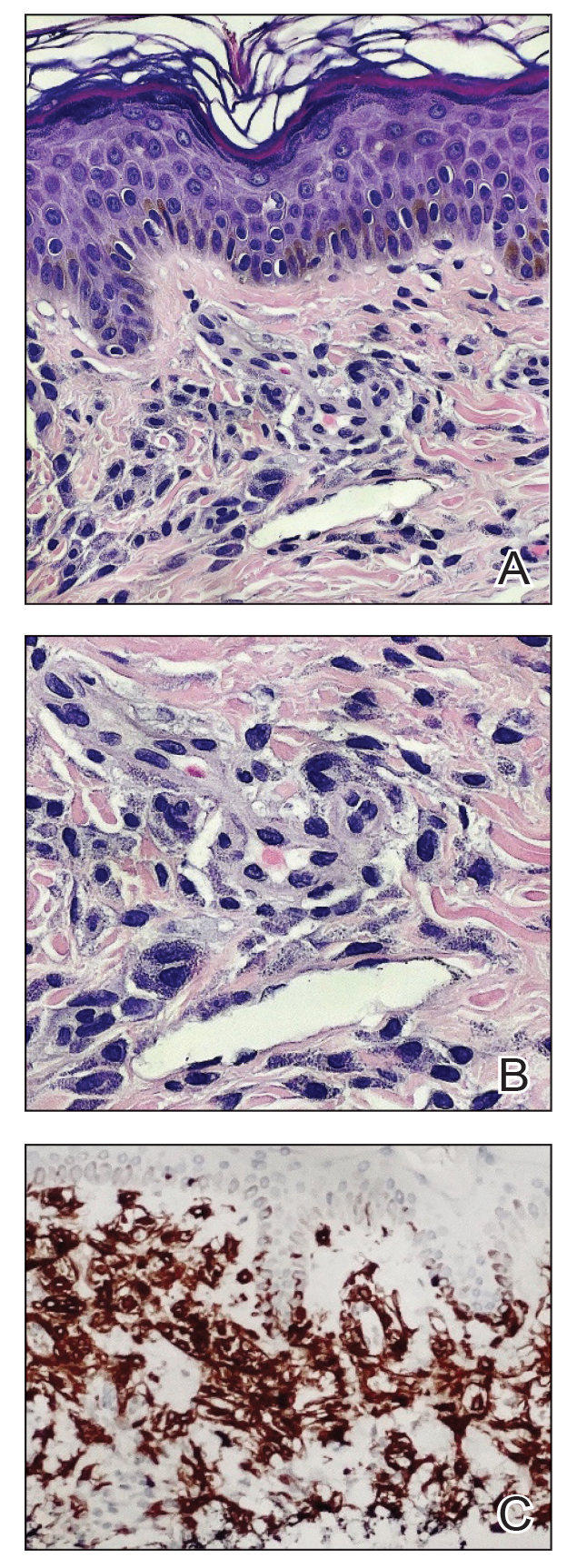

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

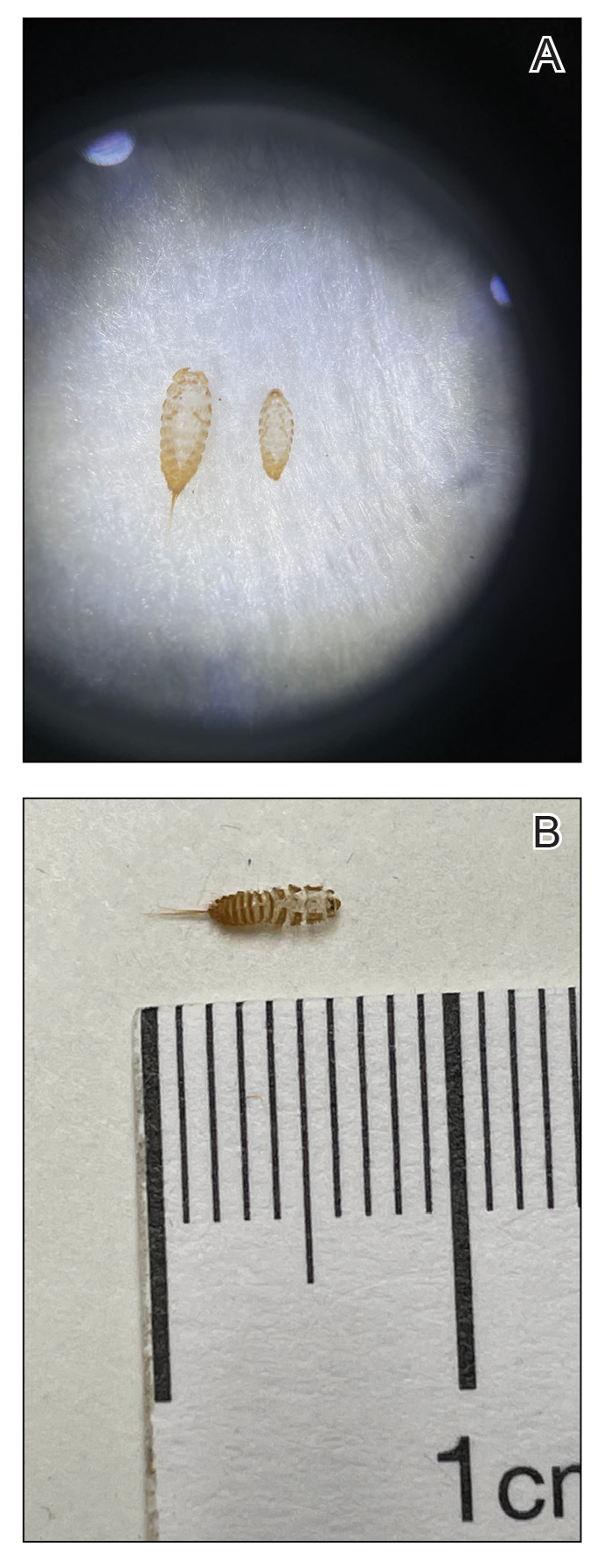

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

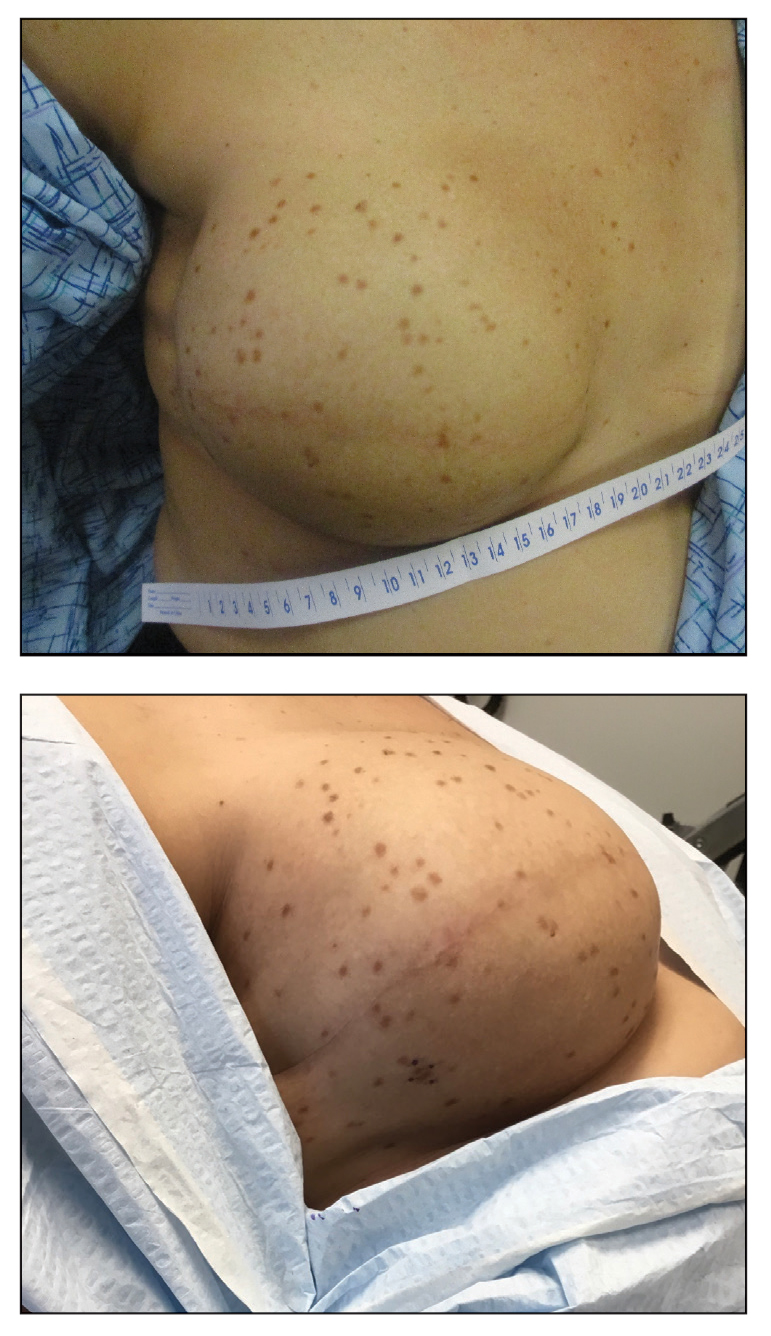

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.

When there are multiple potential suspected allergens or an unknown cause for symptoms despite a detailed history, allergy testing can be useful in confirming a diagnosis and directing management. Immediate-onset type 1 hypersensitivity reactions are evaluated using skin-prick testing or serum IgE levels, whereas delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions can be evaluated using patch testing. Type 1 reactions tend to present with classic allergy symptoms, especially where there are abundant mast cells to degranulate in the skin and mucosa of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts; these symptoms range from mild wheezing, urticaria, periorbital pruritus, and sneezing to outright asthma, diarrhea, rhinoconjunctivitis, and even anaphylaxis. With these reactions, initial exposure to an antigen such as chitin in the hastisetae leads to an asymptomatic sensitization against the antigen in which its introduction leads to a TH2-skewed cellular response, which promotes B-cell production of IgE antibodies. Upon subsequent exposure to this antigen, IgE antibodies bound to mast cells will lead them to degranulate with release of histamine and other proinflammatory molecules, resulting in clinical manifestations. The skin-prick test relies on introduction of potential antigens through the epidermis into the dermis with a sharp lancet to induce IgE antibody activation and then degranulation of the patient’s mast cells, resulting in a pruritic erythematous wheal. This IgE-mediated process has been shown to occur in response to dermestid larval parts among household dust, resulting in chronic coughing, sneezing, nasal pruritus, and asthma.15,17,22

Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions are T-cell mediated and also include a sensitization phase followed by symptom manifestation upon repeat exposure; however, these reactions usually are not immediate and can take up to 72 hours after exposure to manifest.23 This is because T cells specific to the antigen do not lead a process resulting in antibodies but instead recruit numerous other TH1-polarized mediators upon re-exposure to activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and macrophages to attempt to neutralize the antigen. Many type 4 reactions result in mostly cutaneous manifestations, such as contact dermatitis. Patch testing involves adhering potential allergens to the skin for a time with assessments at regular intervals to evaluate the level of reaction from weakly positive to severe. At minimum, most reports of dermestid-related manifestations include a rash such as erythematous papules, and several published cases involving patch testing have yielded positive results to various preparations of larval parts.3,14,21

Management and Treatment

Prevention of dermestid exposure is difficult given the myriad materials eaten by the larvae. An insect exterminator should verify and treat a carpet beetle infestation, while a dermatologist can treat symptomatic individuals. Treatment is driven by the severity of the patient’s discomfort and is aimed at both symptomatic relief and reducing dermestid exposure moving forward. Although in certain environments it will be nearly impossible to eradicate Dermestidae, cleaning thoroughly and regularly may go far to reduce exposure and associated symptoms.

Clothing and other materials such as bedding that will have direct skin contact should be washed to remove hastisetae and be stored in airtight containers in addition to items made with animal fibers, such as wool sweaters and down blankets. Mattresses, flooring, rugs, curtains, and other amenable areas should be vacuumed thoroughly, and the vacuum bag should be placed in the trash afterward. Protective pillow and mattress covers should be used. Stuffed animals in infested areas should be thrown away if not able to be completely washed and dried. Air conditioning systems may spread larval hairs away from the site of infestation and should be cleaned as much as possible. Surfaces where beetles and larvae also are commonly seen, such as windowsills, and hidden among closet and pantry items should also be wiped clean to remove both insects and potential substrate. In one case, scraping the wood flooring and applying a thick coat of varnish in addition to removing all stuffed animals from an affected individual’s home allowed for resolution of symptoms.17

Treatment for symptoms includes topical anti-inflammatory agents and/or oral antihistamines, with improvement in symptoms typically occurring within days and resolution dependent on level of exposure moving forward.

Final Thoughts

- Gumina ME, Yan AC. Carpet beetle dermatitis mimicking bullous impetigo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:329-331. doi:10.1111/pde.14453

- Bertone MA, Leong M, Bayless KM, et al. Arthropods of the great indoors: characterizing diversity inside urban and suburban homes. PeerJ. 2016;4:E1582. doi:10.7717/peerj.1582

- Siegel S, Lee N, Rohr A, et. al. Evaluation of dermestid sensitivity in museum personnel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:190. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(91)91488-F

- Brito FF, Mur P, Barber D, et al. Occupational rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma in a wool worker caused by Dermestidae spp. Allergy. 2002;57:1191-1194.

- Stengaard HL, Akerlund M, Grontoft T, et al. Future pest status of an insect pest in museums, Attagenus smirnovi: distribution and food consumption in relation to climate change. J Cult Herit. 2012;13:22l-227.

- Veer V, Negi BK, Rao KM. Dermestid beetles and some other insect pests associated with stored silkworm cocoons in India, including a world list of dermestid species found attacking this commodity. J Stored Products Research. 1996;32:69-89.

- Veer V, Prasad R, Rao KM. Taxonomic and biological notes on Attagenus and Anthrenus spp. (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) found damaging stored woolen fabrics in India. J Stored Products Research. 1991;27:189-198.

- Háva J. World Catalogue of Insects. Volume 13. Dermestidae (Coleoptera). Brill; 2015.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Di Giulio A, et al. Entangling the enemy: ecological, systematic, and medical implications of dermestid beetle Hastisetae. Insects. 2021;12:436. doi:10.3390/insects12050436

- Arae K, Morita H, Unno H, et al. Chitin promotes antigen-specific Th2 cell-mediated murine asthma through induction of IL-33-mediated IL-1β production by DCs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11721.

- Brinchmann BC, Bayat M, Brøgger T, et. al. A possible role of chitin in the pathogenesis of asthma and allergy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18:7-12.

- Bucolo C, Musumeci M, Musumeci S, et al. Acidic mammalian chitinase and the eye: implications for ocular inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:1-4.

- Hoverson K, Wohltmann WE, Pollack RJ, et al. Dermestid dermatitis in a 2-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:E228-E233. doi:10.1111/pde.12641

- Simon L, Boukari F, Oumarou H, et al. Anthrenus sp. and an uncommon cluster of dermatitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1940-1943. doi:10.3201/eid2707.203245

- Ahmed R, Moy R, Barr R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:428-432.

- MacArthur K, Richardson V, Novoa R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis: a possibly under-recognized entity. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:577-579.

- Cuesta-Herranz J, de las Heras M, Sastre J, et al. Asthma caused by Dermestidae (black carpet beetle): a new allergen in house dust. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(1 Pt 1):147-149.

- Bernstein J, Morgan M, Ghosh D, et al. Respiratory sensitization of a worker to the warehouse beetle Trogoderma variabile: an index case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1413-1416.

- Gorgojo IE, De Las Heras M, Pastor C, et al. Allergy to Dermestidae: a new indoor allergen? [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:AB105.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Battisti A. Occurrence, ecological function and medical importance of dermestid beetle hastisetae. PeerJ. 2020;8:E8340. doi:10.7717/peerj.8340

- Ramachandran J, Hern J, Almeyda J, et al. Contact dermatitis with cervical lymphadenopathy following exposure to the hide beetle, Dermestes peruvianus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:943-945.

- Horster S, Prinz J, Holm N, et al. Anthrenus-dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:328-331.

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Vashisht R, Zito PM. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.

When there are multiple potential suspected allergens or an unknown cause for symptoms despite a detailed history, allergy testing can be useful in confirming a diagnosis and directing management. Immediate-onset type 1 hypersensitivity reactions are evaluated using skin-prick testing or serum IgE levels, whereas delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions can be evaluated using patch testing. Type 1 reactions tend to present with classic allergy symptoms, especially where there are abundant mast cells to degranulate in the skin and mucosa of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts; these symptoms range from mild wheezing, urticaria, periorbital pruritus, and sneezing to outright asthma, diarrhea, rhinoconjunctivitis, and even anaphylaxis. With these reactions, initial exposure to an antigen such as chitin in the hastisetae leads to an asymptomatic sensitization against the antigen in which its introduction leads to a TH2-skewed cellular response, which promotes B-cell production of IgE antibodies. Upon subsequent exposure to this antigen, IgE antibodies bound to mast cells will lead them to degranulate with release of histamine and other proinflammatory molecules, resulting in clinical manifestations. The skin-prick test relies on introduction of potential antigens through the epidermis into the dermis with a sharp lancet to induce IgE antibody activation and then degranulation of the patient’s mast cells, resulting in a pruritic erythematous wheal. This IgE-mediated process has been shown to occur in response to dermestid larval parts among household dust, resulting in chronic coughing, sneezing, nasal pruritus, and asthma.15,17,22

Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions are T-cell mediated and also include a sensitization phase followed by symptom manifestation upon repeat exposure; however, these reactions usually are not immediate and can take up to 72 hours after exposure to manifest.23 This is because T cells specific to the antigen do not lead a process resulting in antibodies but instead recruit numerous other TH1-polarized mediators upon re-exposure to activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and macrophages to attempt to neutralize the antigen. Many type 4 reactions result in mostly cutaneous manifestations, such as contact dermatitis. Patch testing involves adhering potential allergens to the skin for a time with assessments at regular intervals to evaluate the level of reaction from weakly positive to severe. At minimum, most reports of dermestid-related manifestations include a rash such as erythematous papules, and several published cases involving patch testing have yielded positive results to various preparations of larval parts.3,14,21

Management and Treatment

Prevention of dermestid exposure is difficult given the myriad materials eaten by the larvae. An insect exterminator should verify and treat a carpet beetle infestation, while a dermatologist can treat symptomatic individuals. Treatment is driven by the severity of the patient’s discomfort and is aimed at both symptomatic relief and reducing dermestid exposure moving forward. Although in certain environments it will be nearly impossible to eradicate Dermestidae, cleaning thoroughly and regularly may go far to reduce exposure and associated symptoms.

Clothing and other materials such as bedding that will have direct skin contact should be washed to remove hastisetae and be stored in airtight containers in addition to items made with animal fibers, such as wool sweaters and down blankets. Mattresses, flooring, rugs, curtains, and other amenable areas should be vacuumed thoroughly, and the vacuum bag should be placed in the trash afterward. Protective pillow and mattress covers should be used. Stuffed animals in infested areas should be thrown away if not able to be completely washed and dried. Air conditioning systems may spread larval hairs away from the site of infestation and should be cleaned as much as possible. Surfaces where beetles and larvae also are commonly seen, such as windowsills, and hidden among closet and pantry items should also be wiped clean to remove both insects and potential substrate. In one case, scraping the wood flooring and applying a thick coat of varnish in addition to removing all stuffed animals from an affected individual’s home allowed for resolution of symptoms.17

Treatment for symptoms includes topical anti-inflammatory agents and/or oral antihistamines, with improvement in symptoms typically occurring within days and resolution dependent on level of exposure moving forward.

Final Thoughts

Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.

When there are multiple potential suspected allergens or an unknown cause for symptoms despite a detailed history, allergy testing can be useful in confirming a diagnosis and directing management. Immediate-onset type 1 hypersensitivity reactions are evaluated using skin-prick testing or serum IgE levels, whereas delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions can be evaluated using patch testing. Type 1 reactions tend to present with classic allergy symptoms, especially where there are abundant mast cells to degranulate in the skin and mucosa of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts; these symptoms range from mild wheezing, urticaria, periorbital pruritus, and sneezing to outright asthma, diarrhea, rhinoconjunctivitis, and even anaphylaxis. With these reactions, initial exposure to an antigen such as chitin in the hastisetae leads to an asymptomatic sensitization against the antigen in which its introduction leads to a TH2-skewed cellular response, which promotes B-cell production of IgE antibodies. Upon subsequent exposure to this antigen, IgE antibodies bound to mast cells will lead them to degranulate with release of histamine and other proinflammatory molecules, resulting in clinical manifestations. The skin-prick test relies on introduction of potential antigens through the epidermis into the dermis with a sharp lancet to induce IgE antibody activation and then degranulation of the patient’s mast cells, resulting in a pruritic erythematous wheal. This IgE-mediated process has been shown to occur in response to dermestid larval parts among household dust, resulting in chronic coughing, sneezing, nasal pruritus, and asthma.15,17,22

Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions are T-cell mediated and also include a sensitization phase followed by symptom manifestation upon repeat exposure; however, these reactions usually are not immediate and can take up to 72 hours after exposure to manifest.23 This is because T cells specific to the antigen do not lead a process resulting in antibodies but instead recruit numerous other TH1-polarized mediators upon re-exposure to activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and macrophages to attempt to neutralize the antigen. Many type 4 reactions result in mostly cutaneous manifestations, such as contact dermatitis. Patch testing involves adhering potential allergens to the skin for a time with assessments at regular intervals to evaluate the level of reaction from weakly positive to severe. At minimum, most reports of dermestid-related manifestations include a rash such as erythematous papules, and several published cases involving patch testing have yielded positive results to various preparations of larval parts.3,14,21

Management and Treatment

Prevention of dermestid exposure is difficult given the myriad materials eaten by the larvae. An insect exterminator should verify and treat a carpet beetle infestation, while a dermatologist can treat symptomatic individuals. Treatment is driven by the severity of the patient’s discomfort and is aimed at both symptomatic relief and reducing dermestid exposure moving forward. Although in certain environments it will be nearly impossible to eradicate Dermestidae, cleaning thoroughly and regularly may go far to reduce exposure and associated symptoms.

Clothing and other materials such as bedding that will have direct skin contact should be washed to remove hastisetae and be stored in airtight containers in addition to items made with animal fibers, such as wool sweaters and down blankets. Mattresses, flooring, rugs, curtains, and other amenable areas should be vacuumed thoroughly, and the vacuum bag should be placed in the trash afterward. Protective pillow and mattress covers should be used. Stuffed animals in infested areas should be thrown away if not able to be completely washed and dried. Air conditioning systems may spread larval hairs away from the site of infestation and should be cleaned as much as possible. Surfaces where beetles and larvae also are commonly seen, such as windowsills, and hidden among closet and pantry items should also be wiped clean to remove both insects and potential substrate. In one case, scraping the wood flooring and applying a thick coat of varnish in addition to removing all stuffed animals from an affected individual’s home allowed for resolution of symptoms.17

Treatment for symptoms includes topical anti-inflammatory agents and/or oral antihistamines, with improvement in symptoms typically occurring within days and resolution dependent on level of exposure moving forward.

Final Thoughts

- Gumina ME, Yan AC. Carpet beetle dermatitis mimicking bullous impetigo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:329-331. doi:10.1111/pde.14453

- Bertone MA, Leong M, Bayless KM, et al. Arthropods of the great indoors: characterizing diversity inside urban and suburban homes. PeerJ. 2016;4:E1582. doi:10.7717/peerj.1582

- Siegel S, Lee N, Rohr A, et. al. Evaluation of dermestid sensitivity in museum personnel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:190. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(91)91488-F

- Brito FF, Mur P, Barber D, et al. Occupational rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma in a wool worker caused by Dermestidae spp. Allergy. 2002;57:1191-1194.

- Stengaard HL, Akerlund M, Grontoft T, et al. Future pest status of an insect pest in museums, Attagenus smirnovi: distribution and food consumption in relation to climate change. J Cult Herit. 2012;13:22l-227.

- Veer V, Negi BK, Rao KM. Dermestid beetles and some other insect pests associated with stored silkworm cocoons in India, including a world list of dermestid species found attacking this commodity. J Stored Products Research. 1996;32:69-89.

- Veer V, Prasad R, Rao KM. Taxonomic and biological notes on Attagenus and Anthrenus spp. (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) found damaging stored woolen fabrics in India. J Stored Products Research. 1991;27:189-198.

- Háva J. World Catalogue of Insects. Volume 13. Dermestidae (Coleoptera). Brill; 2015.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Di Giulio A, et al. Entangling the enemy: ecological, systematic, and medical implications of dermestid beetle Hastisetae. Insects. 2021;12:436. doi:10.3390/insects12050436

- Arae K, Morita H, Unno H, et al. Chitin promotes antigen-specific Th2 cell-mediated murine asthma through induction of IL-33-mediated IL-1β production by DCs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11721.

- Brinchmann BC, Bayat M, Brøgger T, et. al. A possible role of chitin in the pathogenesis of asthma and allergy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18:7-12.

- Bucolo C, Musumeci M, Musumeci S, et al. Acidic mammalian chitinase and the eye: implications for ocular inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:1-4.

- Hoverson K, Wohltmann WE, Pollack RJ, et al. Dermestid dermatitis in a 2-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:E228-E233. doi:10.1111/pde.12641

- Simon L, Boukari F, Oumarou H, et al. Anthrenus sp. and an uncommon cluster of dermatitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1940-1943. doi:10.3201/eid2707.203245

- Ahmed R, Moy R, Barr R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:428-432.

- MacArthur K, Richardson V, Novoa R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis: a possibly under-recognized entity. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:577-579.

- Cuesta-Herranz J, de las Heras M, Sastre J, et al. Asthma caused by Dermestidae (black carpet beetle): a new allergen in house dust. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(1 Pt 1):147-149.

- Bernstein J, Morgan M, Ghosh D, et al. Respiratory sensitization of a worker to the warehouse beetle Trogoderma variabile: an index case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1413-1416.

- Gorgojo IE, De Las Heras M, Pastor C, et al. Allergy to Dermestidae: a new indoor allergen? [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:AB105.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Battisti A. Occurrence, ecological function and medical importance of dermestid beetle hastisetae. PeerJ. 2020;8:E8340. doi:10.7717/peerj.8340

- Ramachandran J, Hern J, Almeyda J, et al. Contact dermatitis with cervical lymphadenopathy following exposure to the hide beetle, Dermestes peruvianus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:943-945.

- Horster S, Prinz J, Holm N, et al. Anthrenus-dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:328-331.

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Vashisht R, Zito PM. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Gumina ME, Yan AC. Carpet beetle dermatitis mimicking bullous impetigo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:329-331. doi:10.1111/pde.14453

- Bertone MA, Leong M, Bayless KM, et al. Arthropods of the great indoors: characterizing diversity inside urban and suburban homes. PeerJ. 2016;4:E1582. doi:10.7717/peerj.1582

- Siegel S, Lee N, Rohr A, et. al. Evaluation of dermestid sensitivity in museum personnel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:190. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(91)91488-F

- Brito FF, Mur P, Barber D, et al. Occupational rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma in a wool worker caused by Dermestidae spp. Allergy. 2002;57:1191-1194.

- Stengaard HL, Akerlund M, Grontoft T, et al. Future pest status of an insect pest in museums, Attagenus smirnovi: distribution and food consumption in relation to climate change. J Cult Herit. 2012;13:22l-227.

- Veer V, Negi BK, Rao KM. Dermestid beetles and some other insect pests associated with stored silkworm cocoons in India, including a world list of dermestid species found attacking this commodity. J Stored Products Research. 1996;32:69-89.

- Veer V, Prasad R, Rao KM. Taxonomic and biological notes on Attagenus and Anthrenus spp. (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) found damaging stored woolen fabrics in India. J Stored Products Research. 1991;27:189-198.

- Háva J. World Catalogue of Insects. Volume 13. Dermestidae (Coleoptera). Brill; 2015.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Di Giulio A, et al. Entangling the enemy: ecological, systematic, and medical implications of dermestid beetle Hastisetae. Insects. 2021;12:436. doi:10.3390/insects12050436

- Arae K, Morita H, Unno H, et al. Chitin promotes antigen-specific Th2 cell-mediated murine asthma through induction of IL-33-mediated IL-1β production by DCs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11721.

- Brinchmann BC, Bayat M, Brøgger T, et. al. A possible role of chitin in the pathogenesis of asthma and allergy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18:7-12.

- Bucolo C, Musumeci M, Musumeci S, et al. Acidic mammalian chitinase and the eye: implications for ocular inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:1-4.

- Hoverson K, Wohltmann WE, Pollack RJ, et al. Dermestid dermatitis in a 2-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:E228-E233. doi:10.1111/pde.12641

- Simon L, Boukari F, Oumarou H, et al. Anthrenus sp. and an uncommon cluster of dermatitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1940-1943. doi:10.3201/eid2707.203245

- Ahmed R, Moy R, Barr R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:428-432.

- MacArthur K, Richardson V, Novoa R, et al. Carpet beetle dermatitis: a possibly under-recognized entity. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:577-579.

- Cuesta-Herranz J, de las Heras M, Sastre J, et al. Asthma caused by Dermestidae (black carpet beetle): a new allergen in house dust. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(1 Pt 1):147-149.

- Bernstein J, Morgan M, Ghosh D, et al. Respiratory sensitization of a worker to the warehouse beetle Trogoderma variabile: an index case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1413-1416.

- Gorgojo IE, De Las Heras M, Pastor C, et al. Allergy to Dermestidae: a new indoor allergen? [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:AB105.

- Ruzzier E, Kadej M, Battisti A. Occurrence, ecological function and medical importance of dermestid beetle hastisetae. PeerJ. 2020;8:E8340. doi:10.7717/peerj.8340

- Ramachandran J, Hern J, Almeyda J, et al. Contact dermatitis with cervical lymphadenopathy following exposure to the hide beetle, Dermestes peruvianus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:943-945.

- Horster S, Prinz J, Holm N, et al. Anthrenus-dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:328-331.

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Vashisht R, Zito PM. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Practice Points

- Given their ubiquity, dermatologists should be aware of the potential for hypersensitivity reactions to carpet beetles (Dermestidae).

- Pruritic erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles are the most common manifestations of exposure to larval hairs.

- Treatment is symptom based, and future exposure can be greatly diminished with thorough cleaning of the patient’s environment.

Hemorrhagic Crescent Sign in Pseudocellulitis

To the Editor:

Cellulitis is the most common reason for skin-related hospital admissions.1 Despite its frequency, it is suspected that many cases of cellulitis are misdiagnosed as other etiologies presenting with similar symptoms such as a ruptured Baker cyst. These cysts are located behind the knee and can present with calf pain, peripheral edema, and erythema when ruptured. Symptoms of a ruptured Baker cyst can be indistinguishable from cellulitis as well as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), both manifesting with lower extremity pain, swelling, and erythema, making diagnosis challenging.2 The hemorrhagic crescent sign—a crescent of ecchymosis distal to the medial malleolus and on the foot that results from synovial injury or rupture—can be a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate between the causes of acute swelling and pain of the leg.2 When observed, the hemorrhagic crescent sign supports testing for synovial pathology at the knee.

A 63-year-old man presented to an outside hospital for evaluation of a fever (temperature, 101 °F [38.3 °C]), as well as pain, edema, and erythema of the right lower leg of 2 days’ duration. He had a history of leg cellulitis, gout, diabetes mellitus, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy. On admission, he was found to have elevated C-reactive protein (45 mg/L [reference range, <8 mg/L]) and mild leukocytosis (13,500 cells/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000 cells/μL]). A venous duplex scan did not demonstrate signs of thrombosis. Antibiotic therapy was started for suspected cellulitis including levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and linezolid. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, the patient continued to be febrile and experienced progressive erythema and swelling of the right lower leg, at which point he was transferred to our institution. A new antibiotic regimen of vancomycin, cefepime, and clindamycin was started and showed no improvement, after which dermatology was consulted.

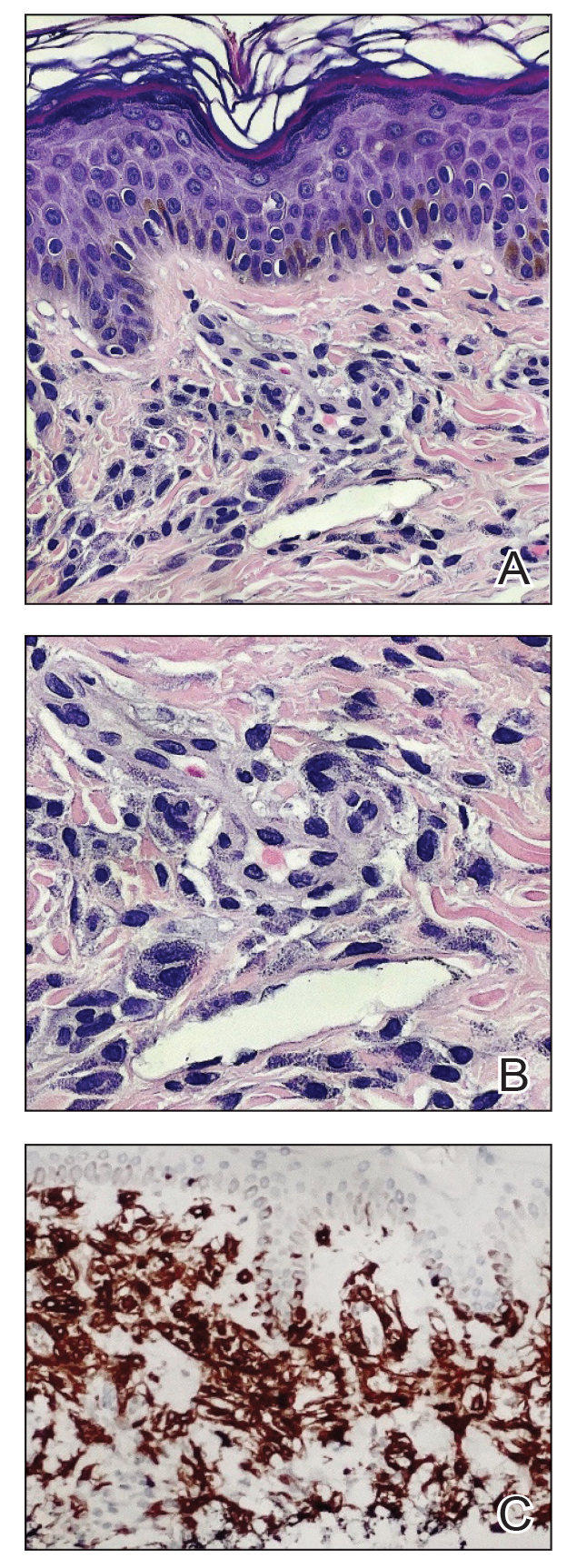

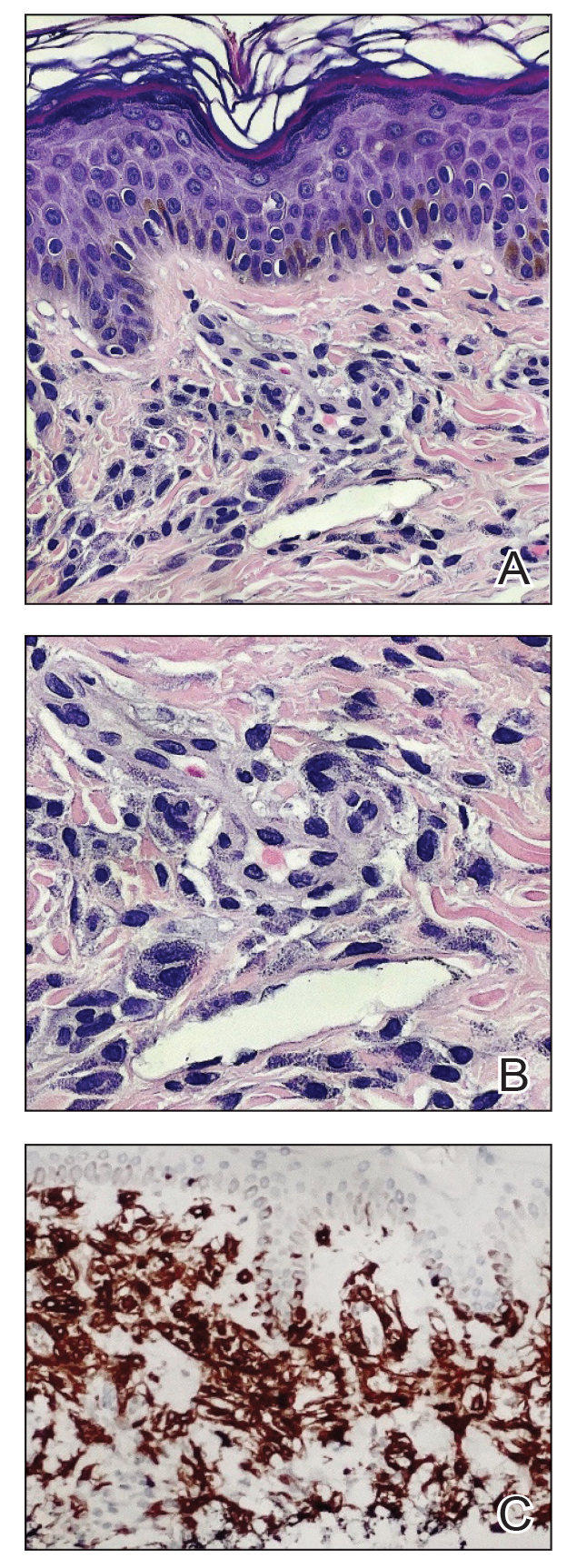

Physical examination revealed unilateral edema and calor of the right lower leg with a demarcated erythematous rash extending to the level of the knee. Furthermore, a hemorrhagic crescent sign was present below the right medial malleolus (Figure). The popliteal fossa was supple, though the patient was adamant that he had a Baker cyst. Punch biopsies demonstrated epidermal spongiosis and extensive edema with perivascular inflammation. No organisms were found by stain and culture. Ultrasound records confirmed a Baker cyst present at least 4 months prior; however, a repeat ultrasound showed resolution. A diagnosis of pseudocellulitis secondary to Baker cyst rupture was made, and corticosteroids were started, resulting in marked reduction in erythema and edema of the lower leg and hospital discharge.

This case highlights the importance of early involvement of dermatology when cellulitis is suspected. A study of 635 patients in the United Kingdom referred to dermatology for lower limb cellulitis found that 210 (33%) patients did not have cellulitis and only 18 (3%) required hospital admission.3 Dermatology consultations have been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory skin disease by decreasing length of stay and reducing readmissions.4

Our patient had several risk factors for cellulitis, including obesity, lymphedema, and chronic kidney disease, in addition to having fevers and unilateral involvement. However, failure of symptoms to improve with broad-spectrum antibiotics made a diagnosis of cellulitis less likely. In this case, a severe immune response to the ruptured Baker cyst mimicked the presentation of cellulitis.

Ruptured Baker cysts have been reported to cause acute leg swelling, mimicking the symptoms of cellulitis or DVT.2,5 The presence of a hemorrhagic crescent sign can be a useful diagnostic tool, as in our patient, because it has been reported as an indication of synovial injury or rupture, supporting the exclusion of cellulitis or DVT when it is observed.6 Prior reports have observed ecchymosis on the foot in as little as 1 day after the onset of calf swelling and at the lateral malleolus 3 days after the onset of calf swelling.5

Following suspicion of a ruptured Baker cyst causing pseudocellulitis, an ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography shows a large hypoechoic space behind the calf muscles, which is pathognomonic of a ruptured Baker cyst.7

In conclusion, when a hemorrhagic crescent sign is observed, one should be suspicious for a ruptured Baker cyst or other synovial pathology as an etiology of pseudocellulitis. Early recognition of the hemorrhagic crescent sign can help rule out cellulitis and DVT, thereby reducing the amount of intravenous antibiotic prescribed, decreasing the length of hospital stay, and reducing readmission.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.7.726

- Von Schroeder HP, Ameli FM, Piazza D, et al. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causes ecchymosis of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:316-317.

- Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1326-1328.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;53:523-528.

- Dunlop D, Parker PJ, Keating JF. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causing posterior compartment syndrome. Injury. 1997;28:561-562.

- Kraag G, Thevathasan EM, Gordon DA, et al. The hemorrhagic crescent sign of acute synovial rupture. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:477-478.

- Sato O, Kondoh K, Iyori K, et al. Midcalf ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ruptured Baker’s cysts. Surg Today. 2001;31:410-413. doi:10.1007/s005950170131

To the Editor:

Cellulitis is the most common reason for skin-related hospital admissions.1 Despite its frequency, it is suspected that many cases of cellulitis are misdiagnosed as other etiologies presenting with similar symptoms such as a ruptured Baker cyst. These cysts are located behind the knee and can present with calf pain, peripheral edema, and erythema when ruptured. Symptoms of a ruptured Baker cyst can be indistinguishable from cellulitis as well as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), both manifesting with lower extremity pain, swelling, and erythema, making diagnosis challenging.2 The hemorrhagic crescent sign—a crescent of ecchymosis distal to the medial malleolus and on the foot that results from synovial injury or rupture—can be a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate between the causes of acute swelling and pain of the leg.2 When observed, the hemorrhagic crescent sign supports testing for synovial pathology at the knee.

A 63-year-old man presented to an outside hospital for evaluation of a fever (temperature, 101 °F [38.3 °C]), as well as pain, edema, and erythema of the right lower leg of 2 days’ duration. He had a history of leg cellulitis, gout, diabetes mellitus, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy. On admission, he was found to have elevated C-reactive protein (45 mg/L [reference range, <8 mg/L]) and mild leukocytosis (13,500 cells/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000 cells/μL]). A venous duplex scan did not demonstrate signs of thrombosis. Antibiotic therapy was started for suspected cellulitis including levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and linezolid. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, the patient continued to be febrile and experienced progressive erythema and swelling of the right lower leg, at which point he was transferred to our institution. A new antibiotic regimen of vancomycin, cefepime, and clindamycin was started and showed no improvement, after which dermatology was consulted.

Physical examination revealed unilateral edema and calor of the right lower leg with a demarcated erythematous rash extending to the level of the knee. Furthermore, a hemorrhagic crescent sign was present below the right medial malleolus (Figure). The popliteal fossa was supple, though the patient was adamant that he had a Baker cyst. Punch biopsies demonstrated epidermal spongiosis and extensive edema with perivascular inflammation. No organisms were found by stain and culture. Ultrasound records confirmed a Baker cyst present at least 4 months prior; however, a repeat ultrasound showed resolution. A diagnosis of pseudocellulitis secondary to Baker cyst rupture was made, and corticosteroids were started, resulting in marked reduction in erythema and edema of the lower leg and hospital discharge.

This case highlights the importance of early involvement of dermatology when cellulitis is suspected. A study of 635 patients in the United Kingdom referred to dermatology for lower limb cellulitis found that 210 (33%) patients did not have cellulitis and only 18 (3%) required hospital admission.3 Dermatology consultations have been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory skin disease by decreasing length of stay and reducing readmissions.4

Our patient had several risk factors for cellulitis, including obesity, lymphedema, and chronic kidney disease, in addition to having fevers and unilateral involvement. However, failure of symptoms to improve with broad-spectrum antibiotics made a diagnosis of cellulitis less likely. In this case, a severe immune response to the ruptured Baker cyst mimicked the presentation of cellulitis.

Ruptured Baker cysts have been reported to cause acute leg swelling, mimicking the symptoms of cellulitis or DVT.2,5 The presence of a hemorrhagic crescent sign can be a useful diagnostic tool, as in our patient, because it has been reported as an indication of synovial injury or rupture, supporting the exclusion of cellulitis or DVT when it is observed.6 Prior reports have observed ecchymosis on the foot in as little as 1 day after the onset of calf swelling and at the lateral malleolus 3 days after the onset of calf swelling.5

Following suspicion of a ruptured Baker cyst causing pseudocellulitis, an ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography shows a large hypoechoic space behind the calf muscles, which is pathognomonic of a ruptured Baker cyst.7

In conclusion, when a hemorrhagic crescent sign is observed, one should be suspicious for a ruptured Baker cyst or other synovial pathology as an etiology of pseudocellulitis. Early recognition of the hemorrhagic crescent sign can help rule out cellulitis and DVT, thereby reducing the amount of intravenous antibiotic prescribed, decreasing the length of hospital stay, and reducing readmission.

To the Editor:

Cellulitis is the most common reason for skin-related hospital admissions.1 Despite its frequency, it is suspected that many cases of cellulitis are misdiagnosed as other etiologies presenting with similar symptoms such as a ruptured Baker cyst. These cysts are located behind the knee and can present with calf pain, peripheral edema, and erythema when ruptured. Symptoms of a ruptured Baker cyst can be indistinguishable from cellulitis as well as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), both manifesting with lower extremity pain, swelling, and erythema, making diagnosis challenging.2 The hemorrhagic crescent sign—a crescent of ecchymosis distal to the medial malleolus and on the foot that results from synovial injury or rupture—can be a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate between the causes of acute swelling and pain of the leg.2 When observed, the hemorrhagic crescent sign supports testing for synovial pathology at the knee.

A 63-year-old man presented to an outside hospital for evaluation of a fever (temperature, 101 °F [38.3 °C]), as well as pain, edema, and erythema of the right lower leg of 2 days’ duration. He had a history of leg cellulitis, gout, diabetes mellitus, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy. On admission, he was found to have elevated C-reactive protein (45 mg/L [reference range, <8 mg/L]) and mild leukocytosis (13,500 cells/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000 cells/μL]). A venous duplex scan did not demonstrate signs of thrombosis. Antibiotic therapy was started for suspected cellulitis including levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and linezolid. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, the patient continued to be febrile and experienced progressive erythema and swelling of the right lower leg, at which point he was transferred to our institution. A new antibiotic regimen of vancomycin, cefepime, and clindamycin was started and showed no improvement, after which dermatology was consulted.

Physical examination revealed unilateral edema and calor of the right lower leg with a demarcated erythematous rash extending to the level of the knee. Furthermore, a hemorrhagic crescent sign was present below the right medial malleolus (Figure). The popliteal fossa was supple, though the patient was adamant that he had a Baker cyst. Punch biopsies demonstrated epidermal spongiosis and extensive edema with perivascular inflammation. No organisms were found by stain and culture. Ultrasound records confirmed a Baker cyst present at least 4 months prior; however, a repeat ultrasound showed resolution. A diagnosis of pseudocellulitis secondary to Baker cyst rupture was made, and corticosteroids were started, resulting in marked reduction in erythema and edema of the lower leg and hospital discharge.

This case highlights the importance of early involvement of dermatology when cellulitis is suspected. A study of 635 patients in the United Kingdom referred to dermatology for lower limb cellulitis found that 210 (33%) patients did not have cellulitis and only 18 (3%) required hospital admission.3 Dermatology consultations have been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory skin disease by decreasing length of stay and reducing readmissions.4

Our patient had several risk factors for cellulitis, including obesity, lymphedema, and chronic kidney disease, in addition to having fevers and unilateral involvement. However, failure of symptoms to improve with broad-spectrum antibiotics made a diagnosis of cellulitis less likely. In this case, a severe immune response to the ruptured Baker cyst mimicked the presentation of cellulitis.

Ruptured Baker cysts have been reported to cause acute leg swelling, mimicking the symptoms of cellulitis or DVT.2,5 The presence of a hemorrhagic crescent sign can be a useful diagnostic tool, as in our patient, because it has been reported as an indication of synovial injury or rupture, supporting the exclusion of cellulitis or DVT when it is observed.6 Prior reports have observed ecchymosis on the foot in as little as 1 day after the onset of calf swelling and at the lateral malleolus 3 days after the onset of calf swelling.5

Following suspicion of a ruptured Baker cyst causing pseudocellulitis, an ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography shows a large hypoechoic space behind the calf muscles, which is pathognomonic of a ruptured Baker cyst.7

In conclusion, when a hemorrhagic crescent sign is observed, one should be suspicious for a ruptured Baker cyst or other synovial pathology as an etiology of pseudocellulitis. Early recognition of the hemorrhagic crescent sign can help rule out cellulitis and DVT, thereby reducing the amount of intravenous antibiotic prescribed, decreasing the length of hospital stay, and reducing readmission.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.7.726

- Von Schroeder HP, Ameli FM, Piazza D, et al. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causes ecchymosis of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:316-317.

- Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1326-1328.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;53:523-528.

- Dunlop D, Parker PJ, Keating JF. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causing posterior compartment syndrome. Injury. 1997;28:561-562.

- Kraag G, Thevathasan EM, Gordon DA, et al. The hemorrhagic crescent sign of acute synovial rupture. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:477-478.

- Sato O, Kondoh K, Iyori K, et al. Midcalf ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ruptured Baker’s cysts. Surg Today. 2001;31:410-413. doi:10.1007/s005950170131

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.7.726

- Von Schroeder HP, Ameli FM, Piazza D, et al. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causes ecchymosis of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:316-317.

- Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1326-1328.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;53:523-528.

- Dunlop D, Parker PJ, Keating JF. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causing posterior compartment syndrome. Injury. 1997;28:561-562.

- Kraag G, Thevathasan EM, Gordon DA, et al. The hemorrhagic crescent sign of acute synovial rupture. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:477-478.

- Sato O, Kondoh K, Iyori K, et al. Midcalf ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ruptured Baker’s cysts. Surg Today. 2001;31:410-413. doi:10.1007/s005950170131

Practice Points

- Pseudocellulitis is common in patients presenting with cellulitislike symptoms.

- A hemorrhagic crescent at the medial malleolus should lead to the suspicion on bursa or joint pathology as a cause of pseudocellulitis.

Burning Skin Patches on the Face, Neck, and Chest

The Diagnosis: Gastric Acid Dermatitis

After further discussion, the patient indicated that he had vomited during the night of alcohol consumption, and the vomitus remained on the affected areas until the next morning, indicating that excessive alcohol ingestion stimulated abundant secretion of gastric acid, which caused the symptoms. Additionally, the presence of clothing acted as a buffer in the unaffected areas, which helped make the final diagnosis of gastric acid dermatitis. The patient was treated with external application of recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor gel (21,000 IU/5 g) once daily, and the lesions greatly improved within 7 days. The burning pain of the throat, stomach, and esophagus resolved after consultation with an otolaryngologist and a gastroenterologist.

Gastric acid dermatitis is a new term used to describe an acute skin burn caused by the patient's own gastric acid. Generally, the pH of human gastric acid is between 0.9 and 1.8 but will be diluted after eating and will gradually increase to approximately 3.5, which is not enough to induce burns on the skin.1 In addition, the skin barrier is capable of preventing transient gastric acid corrosion.2,3 However, the release of a large amount of gastric acid after excessive alcohol ingestion coupled with 1 night of lethargy left enough acid and time to induce skin burns in our patient.

Dermatitis caused by other allergic or chemical factors, such as Paederus dermatitis, was excluded, as the patient’s manifestation occurred during the inactive period of Paederus fuscipes. Furthermore, the patient denied any history of contact with chemicals in the last month. Food eruptions primarily manifest as systemic anaphylaxis with eruptive and pruritic rashes after consumption of seafood, eggs, milk, or other proteins, while alcoholic contact dermatitis is a form of irritating dermatitis that could be easily induced again by direct skin contact with alcohol.

Management of gastric acid dermatitis is similar to that for other chemical burns. Because scarring seldom occurs, the central issue is to restore the skin barrier as quickly as possible and to avoid or alleviate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Treatments to restore the skin barrier include recombinant bovine or human-derived basic fibroblast growth factor gel, moist exposed burn ointment, and medical sodium hyaluronate gelatin. To treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, some whitening agents such as compound superoxide dismutase arbutin cream and hydroquinone cream as well as the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser are effective to ameliorate the skin condition. If skin burns are on sun-exposed areas, photoprotection is necessary to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Acknowledgment—We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ergun P, Kipcak S, Dettmar PW, et al. Pepsin and pH of gastric juice in patients with gastrointestinal reflux disease and subgroups. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:512-517. doi:10.1097 /MCG.0000000000001560

- Mitamura Y, Ogulur I, Pat Y, et al. Dysregulation of the epithelial barrier by environmental and other exogenous factors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:615-626. doi:10.1111/cod.13959

- Kuo SH, Shen CJ, Shen CF, et al. Role of pH value in clinically relevant diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:107. doi:10.3390 /diagnostics10020107

The Diagnosis: Gastric Acid Dermatitis

After further discussion, the patient indicated that he had vomited during the night of alcohol consumption, and the vomitus remained on the affected areas until the next morning, indicating that excessive alcohol ingestion stimulated abundant secretion of gastric acid, which caused the symptoms. Additionally, the presence of clothing acted as a buffer in the unaffected areas, which helped make the final diagnosis of gastric acid dermatitis. The patient was treated with external application of recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor gel (21,000 IU/5 g) once daily, and the lesions greatly improved within 7 days. The burning pain of the throat, stomach, and esophagus resolved after consultation with an otolaryngologist and a gastroenterologist.

Gastric acid dermatitis is a new term used to describe an acute skin burn caused by the patient's own gastric acid. Generally, the pH of human gastric acid is between 0.9 and 1.8 but will be diluted after eating and will gradually increase to approximately 3.5, which is not enough to induce burns on the skin.1 In addition, the skin barrier is capable of preventing transient gastric acid corrosion.2,3 However, the release of a large amount of gastric acid after excessive alcohol ingestion coupled with 1 night of lethargy left enough acid and time to induce skin burns in our patient.

Dermatitis caused by other allergic or chemical factors, such as Paederus dermatitis, was excluded, as the patient’s manifestation occurred during the inactive period of Paederus fuscipes. Furthermore, the patient denied any history of contact with chemicals in the last month. Food eruptions primarily manifest as systemic anaphylaxis with eruptive and pruritic rashes after consumption of seafood, eggs, milk, or other proteins, while alcoholic contact dermatitis is a form of irritating dermatitis that could be easily induced again by direct skin contact with alcohol.

Management of gastric acid dermatitis is similar to that for other chemical burns. Because scarring seldom occurs, the central issue is to restore the skin barrier as quickly as possible and to avoid or alleviate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Treatments to restore the skin barrier include recombinant bovine or human-derived basic fibroblast growth factor gel, moist exposed burn ointment, and medical sodium hyaluronate gelatin. To treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, some whitening agents such as compound superoxide dismutase arbutin cream and hydroquinone cream as well as the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser are effective to ameliorate the skin condition. If skin burns are on sun-exposed areas, photoprotection is necessary to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Acknowledgment—We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

The Diagnosis: Gastric Acid Dermatitis

After further discussion, the patient indicated that he had vomited during the night of alcohol consumption, and the vomitus remained on the affected areas until the next morning, indicating that excessive alcohol ingestion stimulated abundant secretion of gastric acid, which caused the symptoms. Additionally, the presence of clothing acted as a buffer in the unaffected areas, which helped make the final diagnosis of gastric acid dermatitis. The patient was treated with external application of recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor gel (21,000 IU/5 g) once daily, and the lesions greatly improved within 7 days. The burning pain of the throat, stomach, and esophagus resolved after consultation with an otolaryngologist and a gastroenterologist.

Gastric acid dermatitis is a new term used to describe an acute skin burn caused by the patient's own gastric acid. Generally, the pH of human gastric acid is between 0.9 and 1.8 but will be diluted after eating and will gradually increase to approximately 3.5, which is not enough to induce burns on the skin.1 In addition, the skin barrier is capable of preventing transient gastric acid corrosion.2,3 However, the release of a large amount of gastric acid after excessive alcohol ingestion coupled with 1 night of lethargy left enough acid and time to induce skin burns in our patient.

Dermatitis caused by other allergic or chemical factors, such as Paederus dermatitis, was excluded, as the patient’s manifestation occurred during the inactive period of Paederus fuscipes. Furthermore, the patient denied any history of contact with chemicals in the last month. Food eruptions primarily manifest as systemic anaphylaxis with eruptive and pruritic rashes after consumption of seafood, eggs, milk, or other proteins, while alcoholic contact dermatitis is a form of irritating dermatitis that could be easily induced again by direct skin contact with alcohol.

Management of gastric acid dermatitis is similar to that for other chemical burns. Because scarring seldom occurs, the central issue is to restore the skin barrier as quickly as possible and to avoid or alleviate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Treatments to restore the skin barrier include recombinant bovine or human-derived basic fibroblast growth factor gel, moist exposed burn ointment, and medical sodium hyaluronate gelatin. To treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, some whitening agents such as compound superoxide dismutase arbutin cream and hydroquinone cream as well as the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser are effective to ameliorate the skin condition. If skin burns are on sun-exposed areas, photoprotection is necessary to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Acknowledgment—We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ergun P, Kipcak S, Dettmar PW, et al. Pepsin and pH of gastric juice in patients with gastrointestinal reflux disease and subgroups. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:512-517. doi:10.1097 /MCG.0000000000001560

- Mitamura Y, Ogulur I, Pat Y, et al. Dysregulation of the epithelial barrier by environmental and other exogenous factors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:615-626. doi:10.1111/cod.13959

- Kuo SH, Shen CJ, Shen CF, et al. Role of pH value in clinically relevant diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:107. doi:10.3390 /diagnostics10020107

- Ergun P, Kipcak S, Dettmar PW, et al. Pepsin and pH of gastric juice in patients with gastrointestinal reflux disease and subgroups. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:512-517. doi:10.1097 /MCG.0000000000001560

- Mitamura Y, Ogulur I, Pat Y, et al. Dysregulation of the epithelial barrier by environmental and other exogenous factors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:615-626. doi:10.1111/cod.13959

- Kuo SH, Shen CJ, Shen CF, et al. Role of pH value in clinically relevant diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:107. doi:10.3390 /diagnostics10020107

A 26-year-old man presented with a burning skin rash around the mouth, neck, and chest after 1 night of lethargy due to excessive alcohol consumption 2 days prior. He also reported a sore throat and burning pain in the stomach and esophagus. Physical examination revealed signs of severe epidermal necrosis, including erythema, blisters, serous discharge, and superficial crusts on the perioral region, as well as well-defined erythema on the anterior neck and chest. Gastroscopy and laryngoscopy showed extensive mucosal erosion. A laboratory workup revealed no abnormalities.

Tangled Truths: Unraveling the Link Between Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia and Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is an increasingly common diagnosis, especially in middle-aged women, and was first described by Kossard1 in 1994. It is a variant of lichen planopilaris (LPP), a progressive scarring cicatricial alopecia that affects the frontotemporal area of the scalp, eyebrows, and sometimes even body hair.1 Although its etiology remains unclear, genetic causes, drugs, hormones, and environmental exposures—including certain chemicals found in sunscreens—have been implicated in its pathogenesis.2,3 An association between contact allergy to ingredients in personal care products and FFA diagnosis has been suggested; however, there is no evidence of causality to date. In this article, we highlight the potential relationship between contact allergy and FFA as well as clinical considerations for management.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Frontal fibrosing alopecia typically manifests with gradual symmetric recession of the frontal hairline leading to bandlike hair loss along the forehead, sometimes extending to the temporal region.4 Some patients may experience symptoms of scalp itching, burning, or tenderness that may precede or accompany the hair loss. Perifollicular erythema may be visible during the early stages and can be visualized on trichoscopy. The affected skin may appear pale and shiny and may have a smooth texture with a distinct lack of follicular openings. Aside from scalp involvement, other manifestations may include lichen planus pigmentosus, facial papules, body hair involvement, hypochromic lesions, diffuse redness on the face and neck, and prominent frontal veins.5 Although most FFA cases have characteristic clinical features and trichoscopic findings, biopsy for histopathologic examination is still recommended to confirm the diagnosis and ensure appropriate treatment.4 Classic histopathologic features include perifollicular lymphocytic inflammation, follicular destruction, and scarring.

Pathophysiology of FFA

The pathogenesis of FFA is thought to involve a variety of triggers, including immune-mediated inflammation, stress, genetics, hormones, and possibly environmental factors.6 Frontal fibrosing alopecia demonstrates considerable upregulation in cytotoxic helper T cells (TH1) and IFN-γ activity resulting in epithelial hair follicle stem cell apoptosis and replacement of normal epithelial tissue with fibrous tissue.7 There is some suspicion of genetic susceptibility in the onset of FFA as suggested by familial reports and genome-wide association studies.8-10 Hormonal and autoimmune factors also have been linked to FFA, including an increased risk for thyroid disease and the postmenopausal rise of androgen levels.6

Allergic Contact Dermatitis and FFA

Although they are 2 distinct conditions with differing etiologies, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and FFA may share environmental triggers, especially in susceptible individuals. This may support the coexistence and potential association between ACD and FFA.

In one case report, a woman who developed facial eczema followed by FFA showed positive patch tests to the UV filters drometrizole trisiloxane and ethylhexyl salicylate, which were listed as ingredients in her sunscreens. Avoidance of these allergens reportedly led to notable improvement of the symptoms.11 Case-control studies have found an association between the use of facial sunscreen and risk for FFA.12 A 2016 questionnaire that assessed a wide range of lifestyle, social, and medical factors related to FFA found that the use of sunscreens was significantly higher in patients with FFA than controls (P<.001), pointing to sunscreens as a potential contributing factor, but further research has been inconclusive. A higher frequency of positive patch tests to hydroperoxides of linalool and balsam of Peru (BoP) in patients with FFA have been documented; however, a direct cause cannot be established.2

In a 2020 prospective study conducted at multiple international centers, 65% (13/20) of FFA patients and 37.5% (9/24) of the control group had a positive patch test reaction to one or more allergens (P=.003). The most common allergens that were identified included cobalt chloride (positive in 35% [7/20] of patients with FFA), nickel sulfate (25% [5/20]), and potassium dichromate (15% [3/20]).13 In a recent 2-year cohort study of 42 patients with FFA who were referred for patch testing, the most common allergens included gallates, hydroperoxides of linalool, and other fragrances.14 After a 3-month period of allergen avoidance, 70% (29/42) of patients had decreased scalp erythema on examination, indicating that avoiding relevant allergens may reduce local inflammation. Furthermore, 76.2% (32/42) of patients with FFA showed delayed-type hypersensitivity to allergens found in daily personal care products such as shampoos, sunscreens, and moisturizers, among others.14 Notably, the study lacked a control group. A case-control study of 36 Hispanic women conducted in Mexico also resulted in 83.3% (15/18) of patients with FFA and 55.5% (10/18) of controls having at least 1 positive patch test; in the FFA group, these included iodopropynyl butylcarbamate (16.7% [3/18]) and propolis (16.7% [3/18]).15

Most recently, a retrospective study conducted by Shtaynberger et al16 included 12 patients with LPP or FFA diagnosed via clinical findings or biopsy. It also included an age- and temporally matched control group tested with identical allergens. Among the 12 patients who had FFA/LPP, all had at least 1 allergen identified on patch testing. The most common allergens identified were propolis (positive in 50% [6/12] of patients with FFA/LPP), fragrance mix I (16%), and methylisothiazolinone (16% [2/12]). Follow-up data were available for 9 of these patients, of whom 6 (66.7%) experienced symptom improvement after 6 months of allergen avoidance. Four (44.4%) patients experienced decreased follicular redness or scaling, 2 (22.2%) patients experienced improved scalp pain/itch, 2 (22.2%) patients had stable/improved hair density, and 1 (1.1%) patient had decreased hair shedding. Although this suggests an environmental trigger for FFA/LPP, the authors stated that changes in patient treatment plans could have contributed to their improvement. The study also was limited by its small size and its overall generalizability.16

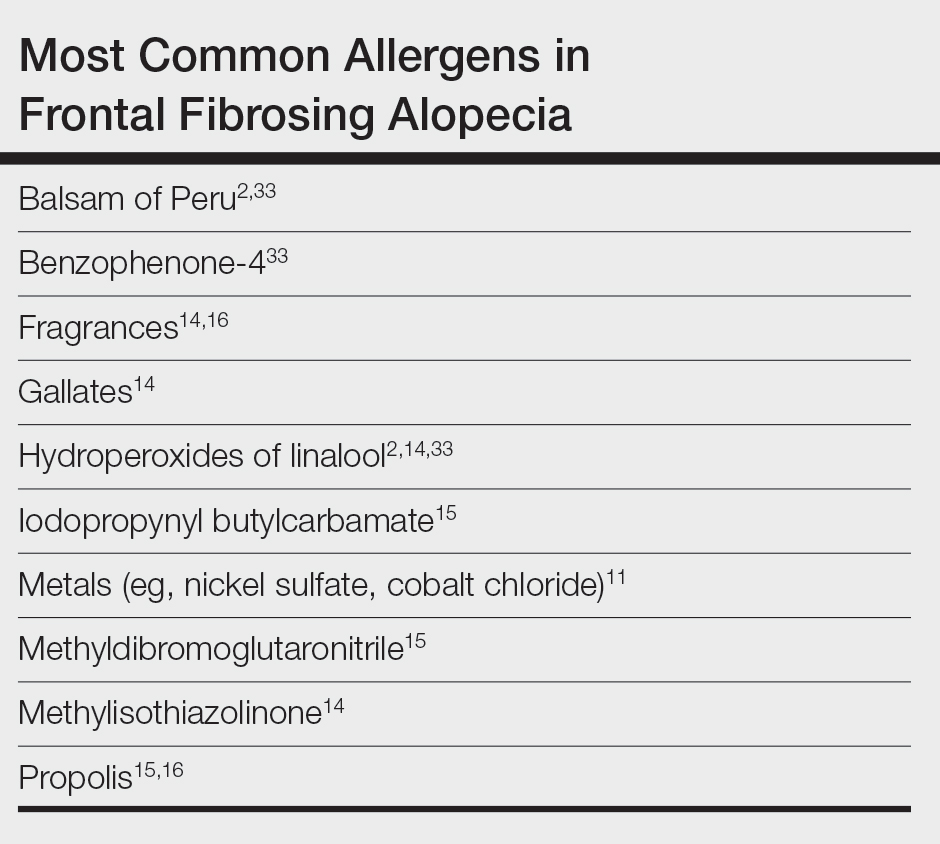

These studies have underscored the significance of patch testing in individuals diagnosed with FFA and have identified common allergens prevalent in this patient population. They have suggested that patients with FFA are more likely to have positive patch tests, and in some cases patients could experience improvements in scalp pruritus and erythema with allergen avoidance; however, we emphasize that a causal association between contact allergy and FFA remains unproven to date.

Most Common Allergens Pertinent to FFA

Preservatives—In some studies, patients with FFA have had positive patch tests to preservatives such as gallates and methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone (MCI/MI).14 Gallates are antioxidants that are used in food preservation, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics due to their ability to inhibit oxidation and rancidity of fats and oils.17 The most common gallates include propyl gallate, octyl gallate, and dodecyl gallate. Propyl gallate is utilized in some waxy or oily cosmetics and personal care items including sunscreens, shampoos, conditioners, bar soaps, facial cleansers, and moisturizers.18 Typically, if patients have a positive patch test to one gallate, they should be advised to avoid all gallate compounds, as they can cross-react.

Similarly, MCI/MI can prevent product degradation through their antibacterial and antifungal properties. This combination of MCI and MI is used as an effective method of prolonging the shelf life of cosmetic products and commonly is found in sunscreens, facial moisturizing creams, shampoos, and conditioners19; it is banned from use in leave-on products in the European Union and Canada due to increased rates of contact allergy.20 In patients with FFA who commonly use facial sunscreen, preservatives can be a potential allergen exposure to consider.

Iodopropynyl butylcarbamate also is a preservative used in cosmetic formulations. Similar to MCI/MI, it is a potent fungicide and bactericide. This allergen can be found in hair care products, bodywashes, and other personal products.21

UV Light–Absorbing Agents—A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2022 showed a significant (P<.001) association between sunscreen use and FFA.22 A majority of allergens identified on patch testing included UVA- and UVB-absorbing agents found in sunscreens and other products including cosmetics,11,12 such as drometrizole trisiloxane, ethylhexyl salicylate, avobenzone, and benzophenone-4. Drometrizole trisiloxane is a photostabilizer and a broad-spectrum UV filter that is not approved for use in sunscreens in the United States.23 It also is effective in stabilizing and preventing the degradation of avobenzone, a commonly used UVA filter.24