User login

Posttraumatic stress may persist up to 9 months after pregnancy loss

new research suggests.

The outcomes of a prospective cohort study involving 737 women who had experienced miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy and 171 controls with healthy pregnancies were presented in a report in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

One month after their pregnancy loss, 29% of these women met the criteria for posttraumatic stress, 24% reported moderate to severe anxiety, and 11% reported moderate to severe depression. In comparison, just 13% of women in the control group met the criteria for anxiety, and 2% met the criteria for depression, which meant women who had experienced early pregnancy loss had a greater than twofold odds of anxiety and nearly fourfold (odds ratio, 3.88) greater odds of depression, reported Jessica Farren, PhD, of the Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital, London, and coauthors.

The most common posttraumatic symptom, experienced by 91% of respondents with posttraumatic stress at 1 month after the pregnancy, was reexperiencing symptoms, while 60% experienced avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms. At 3 months after the loss, 50% of those with posttraumatic stress reported an interruption of their general satisfaction with life.

While the incidence of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression decreased over time in the women who had early pregnancy loss, by the third month 21% still met the criteria for posttraumatic stress, and by 9 months, 18% still were experiencing posttraumatic stress. Similarly, moderate to severe anxiety was still present in 23% of women at 3 months and 17% at 9 months, and moderate to severe depression was still experienced by 8% of women at 3 months and 6% of women at 9 months.

Dr. Farren and coauthors wrote that, given the incidence of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy in the population, the high proportion of women still experiencing posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression at 9 months pointed to a significant public health issue. “It is recognized that PTSD in other contexts can have a significant impact on work, social interaction, health care utilization, and risks in future pregnancies,” they wrote. “Work is needed to evaluate strategies to effectively identify and treat affected women with these specific psychopathologies.”

The investigators also looked at the differences in outcomes in women who experienced miscarriage, compared with those who experienced ectopic pregnancy.

Of the 363 women who had a miscarriage, 30% met criteria for posttraumatic stress at 1 month, 20% at 3 months, and 17% at 9 months. Moderate to severe anxiety was reported by 25% women at 1 month, 22% at 3 months, and 17% at 9 months. Moderate to severe depression was reported by 12% at 1 month, 7% at 3 months, and 5% at 9 months.

Of the 74 women who had an ectopic pregnancy, 23% met criteria for posttraumatic stress at 1 month, 28% at 3 months, and 21% at 9 months. Moderate to severe anxiety was reported by 21% at 1 month, 30% at 3 months, and 23% at 9 months. Moderate to severe depression was reported by 7% at 1 month, 12% at 3 months, and 11% at 9 months.

The authors noted that the incidence of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression decreased more strongly over time in women who had experienced miscarriage, compared with those who experienced ectopic pregnancy, although they commented that the confidence intervals were wide.

One coauthor was supported by an Imperial Health Charity grant and another by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Farren J et al. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.102.

new research suggests.

The outcomes of a prospective cohort study involving 737 women who had experienced miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy and 171 controls with healthy pregnancies were presented in a report in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

One month after their pregnancy loss, 29% of these women met the criteria for posttraumatic stress, 24% reported moderate to severe anxiety, and 11% reported moderate to severe depression. In comparison, just 13% of women in the control group met the criteria for anxiety, and 2% met the criteria for depression, which meant women who had experienced early pregnancy loss had a greater than twofold odds of anxiety and nearly fourfold (odds ratio, 3.88) greater odds of depression, reported Jessica Farren, PhD, of the Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital, London, and coauthors.

The most common posttraumatic symptom, experienced by 91% of respondents with posttraumatic stress at 1 month after the pregnancy, was reexperiencing symptoms, while 60% experienced avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms. At 3 months after the loss, 50% of those with posttraumatic stress reported an interruption of their general satisfaction with life.

While the incidence of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression decreased over time in the women who had early pregnancy loss, by the third month 21% still met the criteria for posttraumatic stress, and by 9 months, 18% still were experiencing posttraumatic stress. Similarly, moderate to severe anxiety was still present in 23% of women at 3 months and 17% at 9 months, and moderate to severe depression was still experienced by 8% of women at 3 months and 6% of women at 9 months.

Dr. Farren and coauthors wrote that, given the incidence of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy in the population, the high proportion of women still experiencing posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression at 9 months pointed to a significant public health issue. “It is recognized that PTSD in other contexts can have a significant impact on work, social interaction, health care utilization, and risks in future pregnancies,” they wrote. “Work is needed to evaluate strategies to effectively identify and treat affected women with these specific psychopathologies.”

The investigators also looked at the differences in outcomes in women who experienced miscarriage, compared with those who experienced ectopic pregnancy.

Of the 363 women who had a miscarriage, 30% met criteria for posttraumatic stress at 1 month, 20% at 3 months, and 17% at 9 months. Moderate to severe anxiety was reported by 25% women at 1 month, 22% at 3 months, and 17% at 9 months. Moderate to severe depression was reported by 12% at 1 month, 7% at 3 months, and 5% at 9 months.

Of the 74 women who had an ectopic pregnancy, 23% met criteria for posttraumatic stress at 1 month, 28% at 3 months, and 21% at 9 months. Moderate to severe anxiety was reported by 21% at 1 month, 30% at 3 months, and 23% at 9 months. Moderate to severe depression was reported by 7% at 1 month, 12% at 3 months, and 11% at 9 months.

The authors noted that the incidence of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression decreased more strongly over time in women who had experienced miscarriage, compared with those who experienced ectopic pregnancy, although they commented that the confidence intervals were wide.

One coauthor was supported by an Imperial Health Charity grant and another by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Farren J et al. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.102.

new research suggests.

The outcomes of a prospective cohort study involving 737 women who had experienced miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy and 171 controls with healthy pregnancies were presented in a report in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

One month after their pregnancy loss, 29% of these women met the criteria for posttraumatic stress, 24% reported moderate to severe anxiety, and 11% reported moderate to severe depression. In comparison, just 13% of women in the control group met the criteria for anxiety, and 2% met the criteria for depression, which meant women who had experienced early pregnancy loss had a greater than twofold odds of anxiety and nearly fourfold (odds ratio, 3.88) greater odds of depression, reported Jessica Farren, PhD, of the Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital, London, and coauthors.

The most common posttraumatic symptom, experienced by 91% of respondents with posttraumatic stress at 1 month after the pregnancy, was reexperiencing symptoms, while 60% experienced avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms. At 3 months after the loss, 50% of those with posttraumatic stress reported an interruption of their general satisfaction with life.

While the incidence of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression decreased over time in the women who had early pregnancy loss, by the third month 21% still met the criteria for posttraumatic stress, and by 9 months, 18% still were experiencing posttraumatic stress. Similarly, moderate to severe anxiety was still present in 23% of women at 3 months and 17% at 9 months, and moderate to severe depression was still experienced by 8% of women at 3 months and 6% of women at 9 months.

Dr. Farren and coauthors wrote that, given the incidence of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy in the population, the high proportion of women still experiencing posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression at 9 months pointed to a significant public health issue. “It is recognized that PTSD in other contexts can have a significant impact on work, social interaction, health care utilization, and risks in future pregnancies,” they wrote. “Work is needed to evaluate strategies to effectively identify and treat affected women with these specific psychopathologies.”

The investigators also looked at the differences in outcomes in women who experienced miscarriage, compared with those who experienced ectopic pregnancy.

Of the 363 women who had a miscarriage, 30% met criteria for posttraumatic stress at 1 month, 20% at 3 months, and 17% at 9 months. Moderate to severe anxiety was reported by 25% women at 1 month, 22% at 3 months, and 17% at 9 months. Moderate to severe depression was reported by 12% at 1 month, 7% at 3 months, and 5% at 9 months.

Of the 74 women who had an ectopic pregnancy, 23% met criteria for posttraumatic stress at 1 month, 28% at 3 months, and 21% at 9 months. Moderate to severe anxiety was reported by 21% at 1 month, 30% at 3 months, and 23% at 9 months. Moderate to severe depression was reported by 7% at 1 month, 12% at 3 months, and 11% at 9 months.

The authors noted that the incidence of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression decreased more strongly over time in women who had experienced miscarriage, compared with those who experienced ectopic pregnancy, although they commented that the confidence intervals were wide.

One coauthor was supported by an Imperial Health Charity grant and another by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Farren J et al. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.102.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Are doctors really at highest risk for suicide?

In October 2012, Pamela Wible, MD, attended a memorial service in her town for a physician who had died by suicide. Sitting in the third row, she began to count all the colleagues she had lost to suicide, and the result shocked her: 3 in her small town alone, 10 if she expanded her scope to all the doctors she’d ever known.

And so she set out on a mission to document as many physician suicides as she could, in an attempt to understand why her fellow doctors were taking their lives. “I viewed this as a personal quest,” she said in an interview. “I wanted to find out why my friends were dying.” Over the course of 7 years, she documented more than 1,300 physician suicides in the United States with the help of individuals who have lost colleagues and loved ones. She maintains a suicide prevention hotline for medical students and doctors.

On her website, Dr. Wible calls high physician suicide rates a “public health crisis.” She states many conclusions from the stories she’s collected, among them that anesthesiologists are at highest risk for suicide among physicians.

The claim that doctors have a high suicide rate is a common one beyond Dr. Wible’s documentation project. Frequently cited papers contend that 300 physicians commit suicide per year, and that physicians’ suicide rate is higher than the general population. Researchers presenting at the American Psychiatric Association meeting in 2018 said physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession – double that of the general population, with one completed suicide every day – and Medscape’s coverage of the talk has been widely referenced as supporting evidence.

A closer look at the data behind these claims, however, reveals the difficulty of establishing reliable statistics. Dr. Wible acknowledges that her data are limited. “We do not have accurate numbers. These [statistics] have come to me organically,” she said. Incorrectly coded death certificates are one reason it’s hard to get solid information. “When we’re trying to figure out how many doctors do die by suicide, it’s very hard to know.”

Similar claims have been made at various times about dentists, construction workers, and farmers, perhaps in an effort to call attention to difficult working conditions and inadequate mental health care. Overall, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who researches physician wellness, mental health, and suicide. It’s critical to know the accurate numbers, she said, “so we can know if we’re making progress.”

Scrutinizing a statistic

The idea for the research presented at the APA meeting in 2018 came up a year earlier “when there were quite a number of physician deaths by suicide,” lead author Omotola T’Sarumi, MD, psychiatrist and chief resident at Columbia University’s Harlem Hospital in New York at the time of the presentation, said in an interview. The poster describes the methodology as a systematic review of research articles published in the last 10 years. Dr. T’Sarumi and colleagues concluded that the rate was 28-40 suicides per 100,000 doctors, compared with a rate of 12.3 per 100,000 for the general population. “That just stunned me,” she said. “We should be doing better.” A peer-reviewed article on the work has not been published.

The references on the poster show limited data to support the headline conclusion that physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession: four papers and a book chapter. The poster itself does not describe the methodology used to arrive at the numbers stated, and Dr. T’Sarumi said that she was unable to gain access to her previous research since moving to a new institution. Dr. Gold, the first author on one of the papers the poster cites, said there are “huge issues” with the work. “In my paper that they’re citing, I was not looking at rates of suicide,” she said. “This is just picking a couple of studies and highlighting them.”

Dr. Gold’s paper uses data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) to identify differences in risk factors and suicide methods between physicians and others who died by suicide in 17 states. The researchers did not attempt to quantify a difference in overall rates, but found that physicians who end their own lives are more likely to have a known mental health disorder with lower rates of medication treatment than nonphysicians. “Inadequate treatment and increased problems related to job stress may be potentially modifiable risk factors to reduce suicidal death among physicians,” the authors conclude.

The second study referenced in the 2018 poster, “A History of Physician Suicide in America” by Rupinder Legha, MD, offers a narrative history of physician suicide, including a reference to an 1897 editorial in the Philadelphia Medical and Surgical Reporter that says: “Our profession is more prone to suicide than any other.” The study does not, however, attempt to quantify that risk.

The third study referenced does offer a quantitative analysis based on death and census data in 26 states, and concludes that the suicide rate for white female physicians was about two times higher than the general population. For white male physicians and dentists, however, the study found that the overall rate of suicide was lower than in the general population, but higher in male physicians and dentists older than 55 years.

In search of reliable data

With all of the popular but poorly substantiated claims about physician suicide, Dr. Gold argues that getting accurate numbers is critical. Without them, there is no way to know if rates are increasing or decreasing over time, or if attempts to help physicians in crisis are effective.

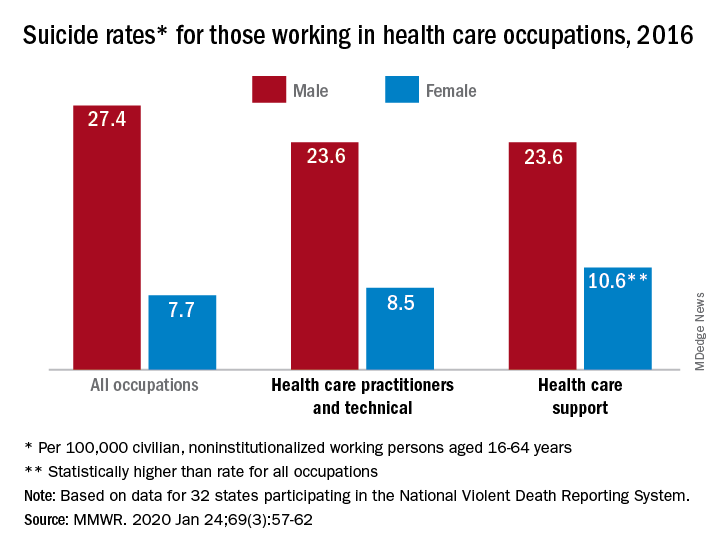

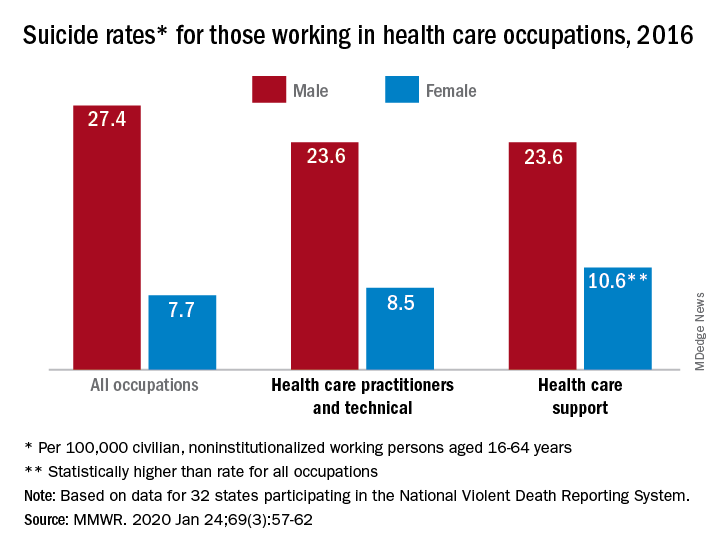

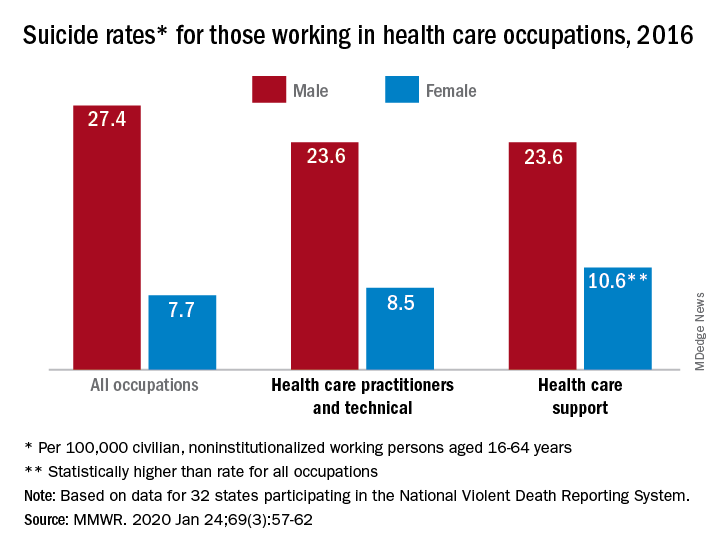

The CDC just released its own updated analysis of NVDRS data by major occupational groups across 32 states in 2016. It shows that males and females in the construction and extraction industries had the highest suicide rates: 49.4 per 100,000 and 25.5 per 100,000 respectively. Males in the “health care practitioners and technical” occupation group had a lower than average rate, while females in the same group had a higher than average rate.

The most reliable data that exist, according to Dr. Gold, are found in the CDC’s National Occupational Mortality Surveillance catalog, though it does not contain information from all states and is missing several years of records. Based on its data, the CDC provides a proportionate mortality ratio (PMR) that indicates whether the proportion of deaths tied to a given cause for a given occupation appears high or low, compared with all other occupations. But occupation data are often missing from the CDC’s records, which could make the PMRs unreliable. “You’re talking about relatively small numbers,” said Dr. Gold. “Even if we’re talking about 400 a year, the difference in one or two or five people being physicians could make a huge difference in the rate.”

The PMR for physicians who have died by intentional self-harm suggests that they are 2.5 times as likely as other populations to die by suicide. Filtering the data by race and gender, it appears black female physicians are at highest risk, more than five times as likely to die by suicide as other populations, while white males are twice as likely. Overall, the professionals with highest suicide risk in the database are hunters and trappers, followed by podiatrists, dentists, veterans, and nuclear engineers. Physicians follow with the fifth-highest rate.

The only way to get a true sense of physician suicide rates would be to collect all of the vital records data that states report to the federal government, according to Dr. Gold. “That would require 50 separate institutional review boards, so I doubt anyone is going to go to the effort to do that study,” she said.

Even without a reliable, exact number, it’s clear there are more physician suicides than there should be, Dr. Gold said. “This is a population that really should not be having a relatively high number of suicide deaths, whether it’s highest or not.”

As Dr. Legha wrote in his “History of Physician Suicide,” cited in the 2018 APA poster: “The problem of physician suicide is not solely a matter of whether or not it takes place at a rate higher than the general public. That a professional caregiver can fall ill and not receive adequate care and support, despite being surrounded by other caregivers, begs for a thoughtful assessment to determine why it happens at all.”

If you or someone you know is in need of support, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s toll-free number is 1-800-273-TALK (8255). A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In October 2012, Pamela Wible, MD, attended a memorial service in her town for a physician who had died by suicide. Sitting in the third row, she began to count all the colleagues she had lost to suicide, and the result shocked her: 3 in her small town alone, 10 if she expanded her scope to all the doctors she’d ever known.

And so she set out on a mission to document as many physician suicides as she could, in an attempt to understand why her fellow doctors were taking their lives. “I viewed this as a personal quest,” she said in an interview. “I wanted to find out why my friends were dying.” Over the course of 7 years, she documented more than 1,300 physician suicides in the United States with the help of individuals who have lost colleagues and loved ones. She maintains a suicide prevention hotline for medical students and doctors.

On her website, Dr. Wible calls high physician suicide rates a “public health crisis.” She states many conclusions from the stories she’s collected, among them that anesthesiologists are at highest risk for suicide among physicians.

The claim that doctors have a high suicide rate is a common one beyond Dr. Wible’s documentation project. Frequently cited papers contend that 300 physicians commit suicide per year, and that physicians’ suicide rate is higher than the general population. Researchers presenting at the American Psychiatric Association meeting in 2018 said physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession – double that of the general population, with one completed suicide every day – and Medscape’s coverage of the talk has been widely referenced as supporting evidence.

A closer look at the data behind these claims, however, reveals the difficulty of establishing reliable statistics. Dr. Wible acknowledges that her data are limited. “We do not have accurate numbers. These [statistics] have come to me organically,” she said. Incorrectly coded death certificates are one reason it’s hard to get solid information. “When we’re trying to figure out how many doctors do die by suicide, it’s very hard to know.”

Similar claims have been made at various times about dentists, construction workers, and farmers, perhaps in an effort to call attention to difficult working conditions and inadequate mental health care. Overall, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who researches physician wellness, mental health, and suicide. It’s critical to know the accurate numbers, she said, “so we can know if we’re making progress.”

Scrutinizing a statistic

The idea for the research presented at the APA meeting in 2018 came up a year earlier “when there were quite a number of physician deaths by suicide,” lead author Omotola T’Sarumi, MD, psychiatrist and chief resident at Columbia University’s Harlem Hospital in New York at the time of the presentation, said in an interview. The poster describes the methodology as a systematic review of research articles published in the last 10 years. Dr. T’Sarumi and colleagues concluded that the rate was 28-40 suicides per 100,000 doctors, compared with a rate of 12.3 per 100,000 for the general population. “That just stunned me,” she said. “We should be doing better.” A peer-reviewed article on the work has not been published.

The references on the poster show limited data to support the headline conclusion that physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession: four papers and a book chapter. The poster itself does not describe the methodology used to arrive at the numbers stated, and Dr. T’Sarumi said that she was unable to gain access to her previous research since moving to a new institution. Dr. Gold, the first author on one of the papers the poster cites, said there are “huge issues” with the work. “In my paper that they’re citing, I was not looking at rates of suicide,” she said. “This is just picking a couple of studies and highlighting them.”

Dr. Gold’s paper uses data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) to identify differences in risk factors and suicide methods between physicians and others who died by suicide in 17 states. The researchers did not attempt to quantify a difference in overall rates, but found that physicians who end their own lives are more likely to have a known mental health disorder with lower rates of medication treatment than nonphysicians. “Inadequate treatment and increased problems related to job stress may be potentially modifiable risk factors to reduce suicidal death among physicians,” the authors conclude.

The second study referenced in the 2018 poster, “A History of Physician Suicide in America” by Rupinder Legha, MD, offers a narrative history of physician suicide, including a reference to an 1897 editorial in the Philadelphia Medical and Surgical Reporter that says: “Our profession is more prone to suicide than any other.” The study does not, however, attempt to quantify that risk.

The third study referenced does offer a quantitative analysis based on death and census data in 26 states, and concludes that the suicide rate for white female physicians was about two times higher than the general population. For white male physicians and dentists, however, the study found that the overall rate of suicide was lower than in the general population, but higher in male physicians and dentists older than 55 years.

In search of reliable data

With all of the popular but poorly substantiated claims about physician suicide, Dr. Gold argues that getting accurate numbers is critical. Without them, there is no way to know if rates are increasing or decreasing over time, or if attempts to help physicians in crisis are effective.

The CDC just released its own updated analysis of NVDRS data by major occupational groups across 32 states in 2016. It shows that males and females in the construction and extraction industries had the highest suicide rates: 49.4 per 100,000 and 25.5 per 100,000 respectively. Males in the “health care practitioners and technical” occupation group had a lower than average rate, while females in the same group had a higher than average rate.

The most reliable data that exist, according to Dr. Gold, are found in the CDC’s National Occupational Mortality Surveillance catalog, though it does not contain information from all states and is missing several years of records. Based on its data, the CDC provides a proportionate mortality ratio (PMR) that indicates whether the proportion of deaths tied to a given cause for a given occupation appears high or low, compared with all other occupations. But occupation data are often missing from the CDC’s records, which could make the PMRs unreliable. “You’re talking about relatively small numbers,” said Dr. Gold. “Even if we’re talking about 400 a year, the difference in one or two or five people being physicians could make a huge difference in the rate.”

The PMR for physicians who have died by intentional self-harm suggests that they are 2.5 times as likely as other populations to die by suicide. Filtering the data by race and gender, it appears black female physicians are at highest risk, more than five times as likely to die by suicide as other populations, while white males are twice as likely. Overall, the professionals with highest suicide risk in the database are hunters and trappers, followed by podiatrists, dentists, veterans, and nuclear engineers. Physicians follow with the fifth-highest rate.

The only way to get a true sense of physician suicide rates would be to collect all of the vital records data that states report to the federal government, according to Dr. Gold. “That would require 50 separate institutional review boards, so I doubt anyone is going to go to the effort to do that study,” she said.

Even without a reliable, exact number, it’s clear there are more physician suicides than there should be, Dr. Gold said. “This is a population that really should not be having a relatively high number of suicide deaths, whether it’s highest or not.”

As Dr. Legha wrote in his “History of Physician Suicide,” cited in the 2018 APA poster: “The problem of physician suicide is not solely a matter of whether or not it takes place at a rate higher than the general public. That a professional caregiver can fall ill and not receive adequate care and support, despite being surrounded by other caregivers, begs for a thoughtful assessment to determine why it happens at all.”

If you or someone you know is in need of support, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s toll-free number is 1-800-273-TALK (8255). A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In October 2012, Pamela Wible, MD, attended a memorial service in her town for a physician who had died by suicide. Sitting in the third row, she began to count all the colleagues she had lost to suicide, and the result shocked her: 3 in her small town alone, 10 if she expanded her scope to all the doctors she’d ever known.

And so she set out on a mission to document as many physician suicides as she could, in an attempt to understand why her fellow doctors were taking their lives. “I viewed this as a personal quest,” she said in an interview. “I wanted to find out why my friends were dying.” Over the course of 7 years, she documented more than 1,300 physician suicides in the United States with the help of individuals who have lost colleagues and loved ones. She maintains a suicide prevention hotline for medical students and doctors.

On her website, Dr. Wible calls high physician suicide rates a “public health crisis.” She states many conclusions from the stories she’s collected, among them that anesthesiologists are at highest risk for suicide among physicians.

The claim that doctors have a high suicide rate is a common one beyond Dr. Wible’s documentation project. Frequently cited papers contend that 300 physicians commit suicide per year, and that physicians’ suicide rate is higher than the general population. Researchers presenting at the American Psychiatric Association meeting in 2018 said physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession – double that of the general population, with one completed suicide every day – and Medscape’s coverage of the talk has been widely referenced as supporting evidence.

A closer look at the data behind these claims, however, reveals the difficulty of establishing reliable statistics. Dr. Wible acknowledges that her data are limited. “We do not have accurate numbers. These [statistics] have come to me organically,” she said. Incorrectly coded death certificates are one reason it’s hard to get solid information. “When we’re trying to figure out how many doctors do die by suicide, it’s very hard to know.”

Similar claims have been made at various times about dentists, construction workers, and farmers, perhaps in an effort to call attention to difficult working conditions and inadequate mental health care. Overall, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who researches physician wellness, mental health, and suicide. It’s critical to know the accurate numbers, she said, “so we can know if we’re making progress.”

Scrutinizing a statistic

The idea for the research presented at the APA meeting in 2018 came up a year earlier “when there were quite a number of physician deaths by suicide,” lead author Omotola T’Sarumi, MD, psychiatrist and chief resident at Columbia University’s Harlem Hospital in New York at the time of the presentation, said in an interview. The poster describes the methodology as a systematic review of research articles published in the last 10 years. Dr. T’Sarumi and colleagues concluded that the rate was 28-40 suicides per 100,000 doctors, compared with a rate of 12.3 per 100,000 for the general population. “That just stunned me,” she said. “We should be doing better.” A peer-reviewed article on the work has not been published.

The references on the poster show limited data to support the headline conclusion that physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession: four papers and a book chapter. The poster itself does not describe the methodology used to arrive at the numbers stated, and Dr. T’Sarumi said that she was unable to gain access to her previous research since moving to a new institution. Dr. Gold, the first author on one of the papers the poster cites, said there are “huge issues” with the work. “In my paper that they’re citing, I was not looking at rates of suicide,” she said. “This is just picking a couple of studies and highlighting them.”

Dr. Gold’s paper uses data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) to identify differences in risk factors and suicide methods between physicians and others who died by suicide in 17 states. The researchers did not attempt to quantify a difference in overall rates, but found that physicians who end their own lives are more likely to have a known mental health disorder with lower rates of medication treatment than nonphysicians. “Inadequate treatment and increased problems related to job stress may be potentially modifiable risk factors to reduce suicidal death among physicians,” the authors conclude.

The second study referenced in the 2018 poster, “A History of Physician Suicide in America” by Rupinder Legha, MD, offers a narrative history of physician suicide, including a reference to an 1897 editorial in the Philadelphia Medical and Surgical Reporter that says: “Our profession is more prone to suicide than any other.” The study does not, however, attempt to quantify that risk.

The third study referenced does offer a quantitative analysis based on death and census data in 26 states, and concludes that the suicide rate for white female physicians was about two times higher than the general population. For white male physicians and dentists, however, the study found that the overall rate of suicide was lower than in the general population, but higher in male physicians and dentists older than 55 years.

In search of reliable data

With all of the popular but poorly substantiated claims about physician suicide, Dr. Gold argues that getting accurate numbers is critical. Without them, there is no way to know if rates are increasing or decreasing over time, or if attempts to help physicians in crisis are effective.

The CDC just released its own updated analysis of NVDRS data by major occupational groups across 32 states in 2016. It shows that males and females in the construction and extraction industries had the highest suicide rates: 49.4 per 100,000 and 25.5 per 100,000 respectively. Males in the “health care practitioners and technical” occupation group had a lower than average rate, while females in the same group had a higher than average rate.

The most reliable data that exist, according to Dr. Gold, are found in the CDC’s National Occupational Mortality Surveillance catalog, though it does not contain information from all states and is missing several years of records. Based on its data, the CDC provides a proportionate mortality ratio (PMR) that indicates whether the proportion of deaths tied to a given cause for a given occupation appears high or low, compared with all other occupations. But occupation data are often missing from the CDC’s records, which could make the PMRs unreliable. “You’re talking about relatively small numbers,” said Dr. Gold. “Even if we’re talking about 400 a year, the difference in one or two or five people being physicians could make a huge difference in the rate.”

The PMR for physicians who have died by intentional self-harm suggests that they are 2.5 times as likely as other populations to die by suicide. Filtering the data by race and gender, it appears black female physicians are at highest risk, more than five times as likely to die by suicide as other populations, while white males are twice as likely. Overall, the professionals with highest suicide risk in the database are hunters and trappers, followed by podiatrists, dentists, veterans, and nuclear engineers. Physicians follow with the fifth-highest rate.

The only way to get a true sense of physician suicide rates would be to collect all of the vital records data that states report to the federal government, according to Dr. Gold. “That would require 50 separate institutional review boards, so I doubt anyone is going to go to the effort to do that study,” she said.

Even without a reliable, exact number, it’s clear there are more physician suicides than there should be, Dr. Gold said. “This is a population that really should not be having a relatively high number of suicide deaths, whether it’s highest or not.”

As Dr. Legha wrote in his “History of Physician Suicide,” cited in the 2018 APA poster: “The problem of physician suicide is not solely a matter of whether or not it takes place at a rate higher than the general public. That a professional caregiver can fall ill and not receive adequate care and support, despite being surrounded by other caregivers, begs for a thoughtful assessment to determine why it happens at all.”

If you or someone you know is in need of support, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s toll-free number is 1-800-273-TALK (8255). A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

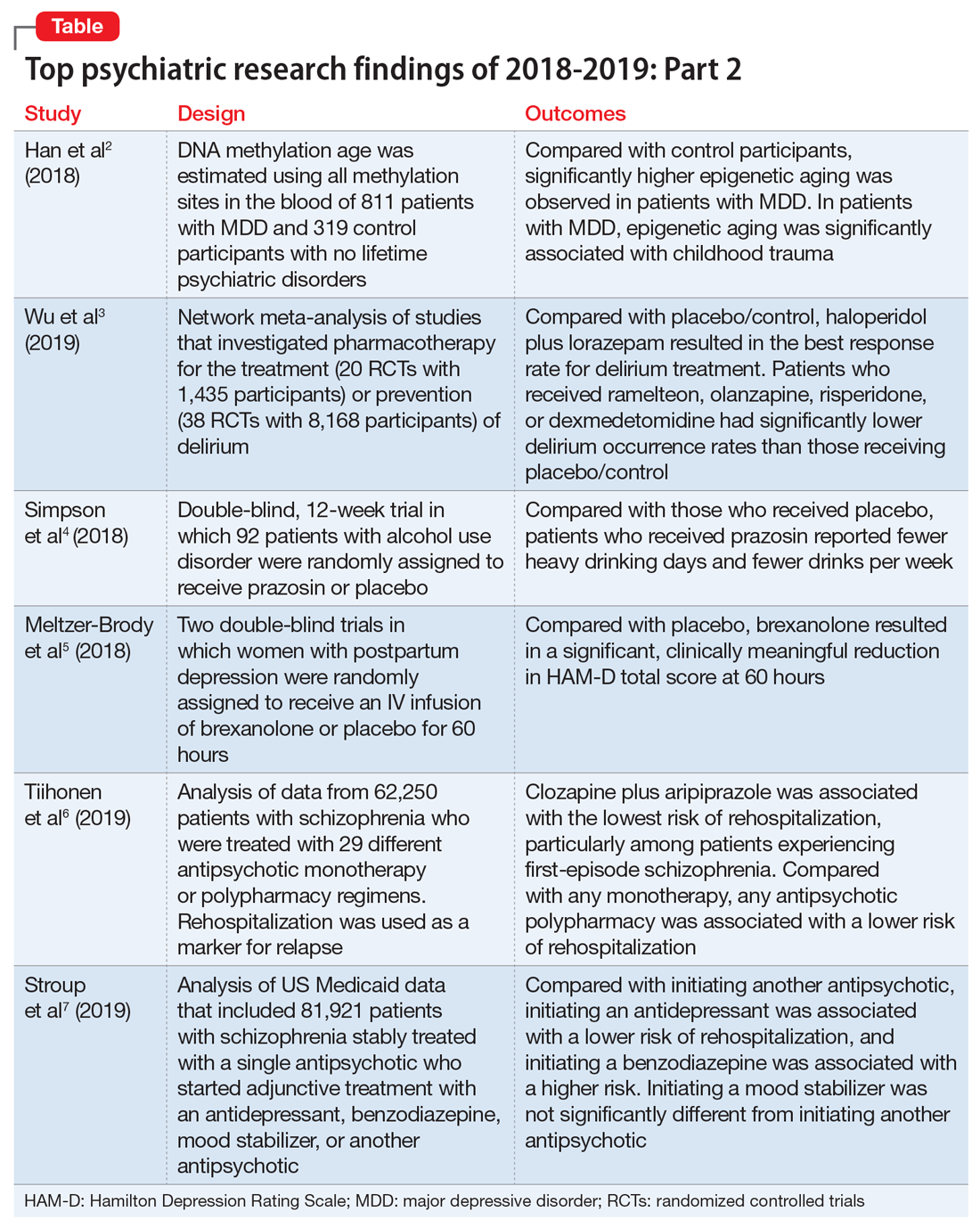

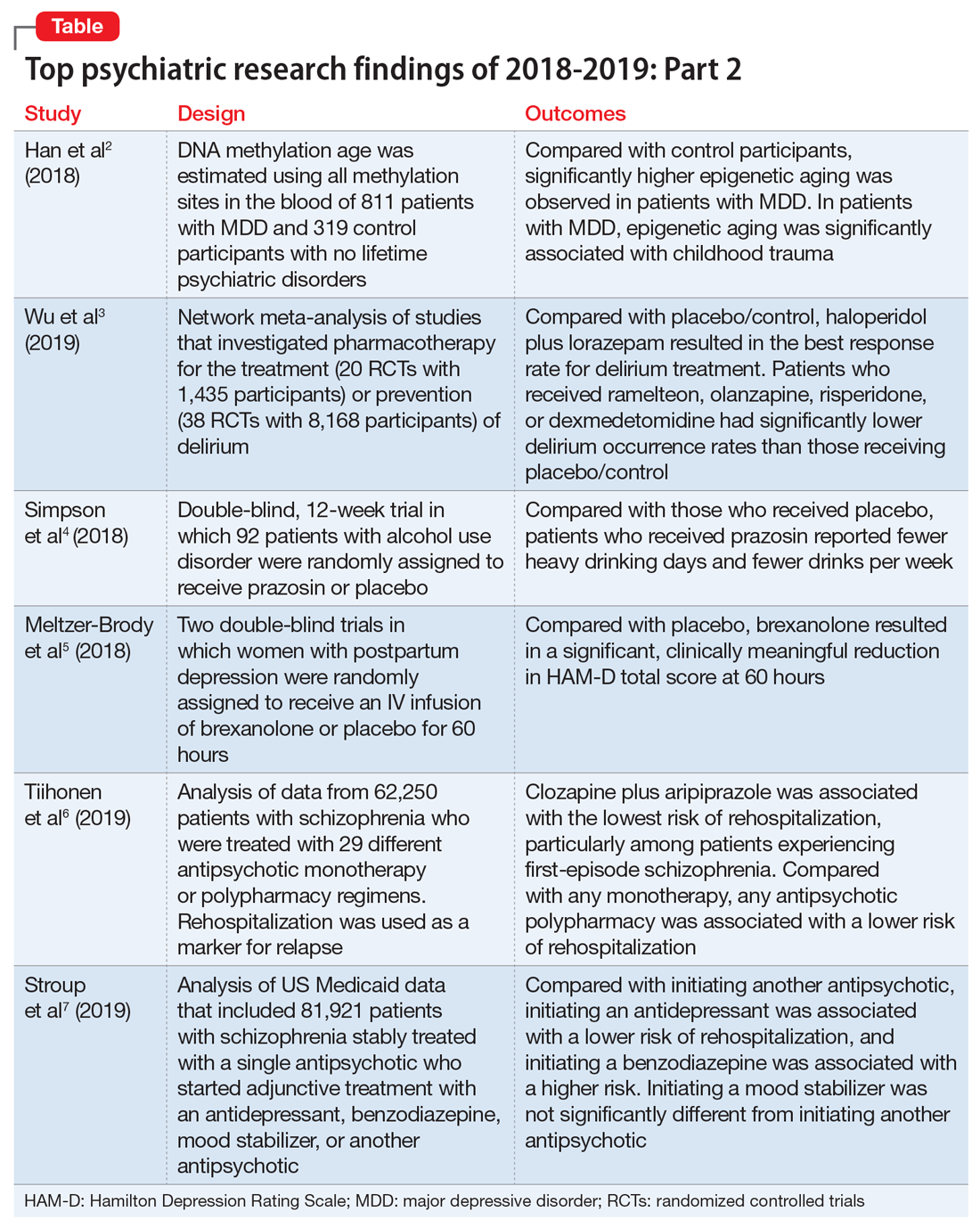

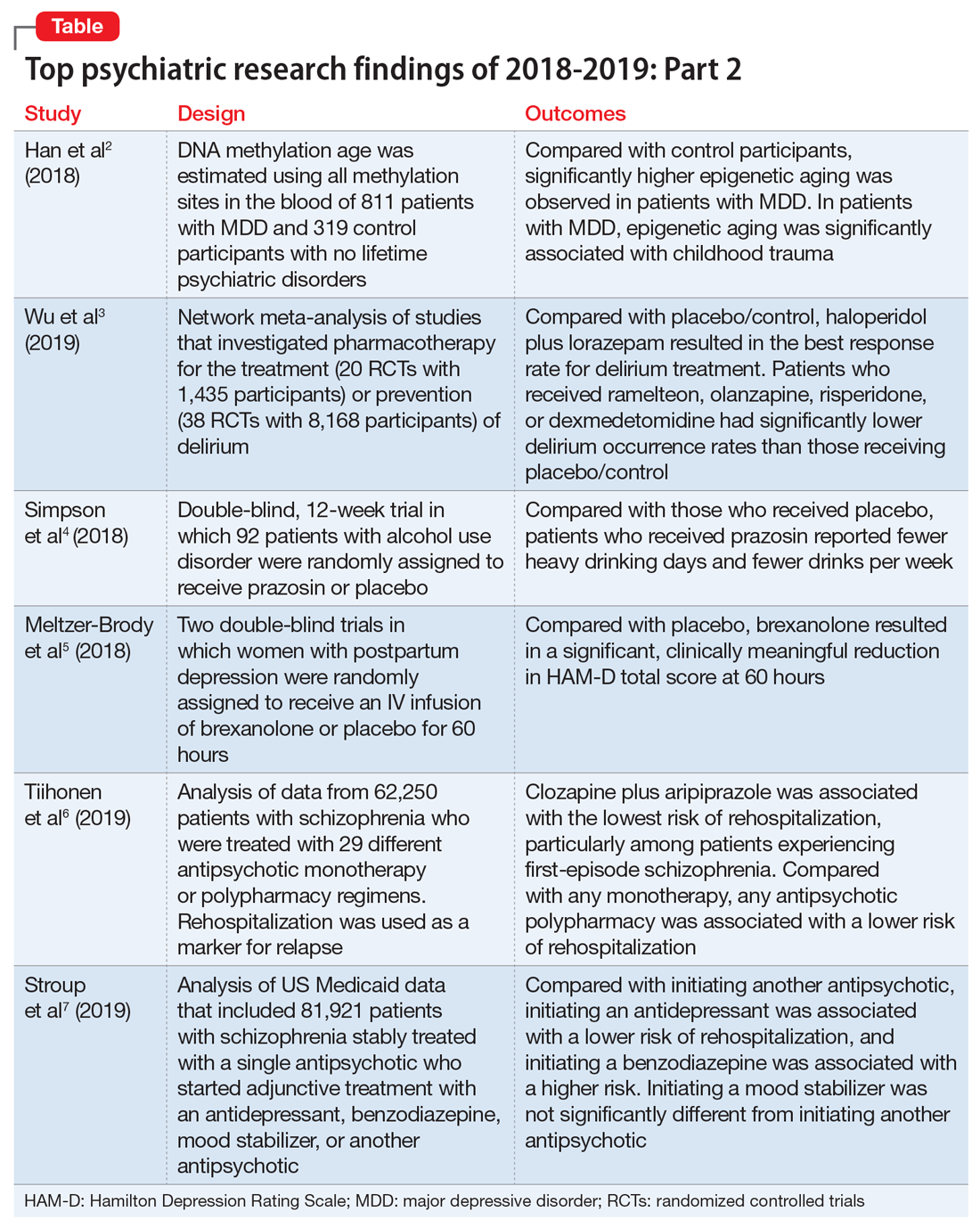

Top research findings of 2018-2019 for clinical practice

In Part 1 of this article, published in

1. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.

In light of the association of major depressive disorder (MDD) with an increased risk of aging-related diseases, Han et al2 examined whether MDD was associated with higher epigenetic aging in blood as measured by DNA methylation patterns. They also studied whether clinical characteristics of MDD had a further impact on these patterns, and whether the findings replicated in brain tissue. Many differentially methylated regions of our DNA tend to change as we age. Han et al2 used these age-sensitive differentially methylated regions to estimate chronological age, using DNA extracted from various tissues, including blood and brain.

Study design

- As a part of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), this study included 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants with no lifetime psychiatric disorders and low depressive symptoms (Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology score <14).

- Diagnosis of MDD and clinical characteristics were assessed by questionnaires and psychiatric interviews. Childhood trauma was assessed using the NEMESIS childhood trauma interview, which included a structured inventory of trauma exposure during childhood.

- DNA methylation age was estimated using all methylation sites in the blood of 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants. The residuals of the DNA methylation age estimates regressed on chronological age were calculated to indicate epigenetic aging.

- Analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and health status.

- Postmortem brain samples of 74 patients with MDD and 64 control participants were used for replication.

Outcomes

- Significantly higher epigenetic aging was observed in patients with MDD compared with control participants (Cohen’s d = 0.18), which suggests that patients with MDD are biologically older than their corresponding chronological age. There was a significant dose effect with increasing symptom severity in the overall sample.

- In the MDD group, epigenetic aging was positively and significantly associated with childhood trauma.

- The case-control difference was replicated in an independent analysis of postmortem brain samples.

Conclusion

- These findings suggest that patients with MDD and people with a history of childhood trauma may biologically age relatively faster than those without MDD or childhood trauma. These findings may represent a biomarker of aging and might help identify patients who may benefit from early and intensive interventions to reduce the physical comorbidities of MDD.

- This study raises the possibility that MDD may be causally related to epigenetic age acceleration. However, it only points out the associations; there are other possible explanations for this correlation, including the possibility that a shared risk factor accounts for the observed association.

2. Wu YC, Tseng PT, Tu YK, et al. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526-535.

Delirium is common and often goes underdiagnosed. It is particularly prevalent among hospitalized geriatric patients. Several medications have been suggested to have a role in treating or preventing delirium. However, it remains uncertain which medications provide the best response rate, the lowest rate of delirium occurrence, and the best tolerability. In an attempt to find answers to these questions, Wu et al3 reviewed studies that evaluated the use of various medications used for delirium.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated various pharmacologic agents used to treat or prevent delirium.

- Fifty-eight RCTs were included in the analyses. Of these, 20 RCTs with a total of 1,435 participants compared the outcomes of treatments of delirium, and 38 RCTs with a total of 8,168 participants examined prevention.

- A network meta-analysis was performed to determine if an agent or combinations of agents were superior to placebo or widely used medications.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam provided the best response rate for treating delirium compared with placebo/control.

- For delirium prevention, patients who received ramelteon, olanzapine, risperidone, or dexmedetomidine had significantly lower delirium occurrence rates than those receiving placebo/control.

- None of the pharmacologic treatments were significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared with placebo/control.

Conclusion

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam might be the best treatment and ramelteon the best preventive medicine for delirium. None of the pharmacologic interventions for treatment or prophylaxis increased all-cause mortality.

- However, network meta-analyses involve extrapolating treatment comparisons that are not made directly. As Blazer8 pointed out, both findings in this study (that haloperidol plus lorazepam is a unique intervention among the treatment trials and ramelteon is a unique intervention for prevention) seemed to be driven by 2 of the 58 studies that Wu et al3 examined.Wu et al3 also cautioned that both of these interventions needed to be further researched for efficacy.

3. Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Stappenbeck C, et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1216-1224.

While some evidence suggests that elevated brain noradrenergic activity is involved in the initiation and maintenance of alcohol use disorder,9 current medications used to treat alcohol use disorder do not target brain noradrenergic pathways. In an RCT, Simpson et al4 tested prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, for the treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Study design

- In this 12-week double-blind study, 92 participants with alcohol use disorder were randomly assigned to receive prazosin or placebo. Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder were excluded.

- Prazosin was titrated to a target dosing schedule of 4 mg in the morning, 4 mg in the afternoon, and 8 mg at bedtime by the end of Week 2. The behavioral platform was medical management. Participants provided daily data on their alcohol consumption.

- Generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to examine the impact of prazosin compared with placebo on number of drinks per week, number of drinking days per week, and number of heavy drinking days per week.

Outcomes

- Among the 80 participants who completed the titration period and were included in the primary analyses, prazosin was associated with self-reported fewer heavy drinking days, and fewer drinks per week (Palatino LT Std−8 vs Palatino LT Std−1.5 with placebo). Drinking days per week and craving showed no group differences.

- The rate of drinking and the probability of heavy drinking showed a greater decrease over time for participants receiving prazosin compared with those receiving placebo.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- These findings of moderate reductions in heavy drinking days and drinks per week with prazosin suggest that prazosin may be a promising harm-reduction treatment for alcohol use disorder.

4. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

Postpartum depression is among the most common complications of childbirth. It can result in considerable suffering for mothers, children, and families. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling has previously been reported to be involved in the pathophysiology of postpartum depression. Meltzer-Brody et al5 conducted 2 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials comparing brexanolone with placebo in women with postpartum depression at 30 clinical research centers and specialized psychiatric units in the United States.

Study design

- Participants were women age 18 to 45, Palatino LT Std≤6 months postpartum at screening, with postpartum depression as indicated by a qualifying 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score of ≥26 for Study 1 or 20 to 25 for Study 2.

- Of the 375 women who were screened simultaneously across both studies, 138 were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive a single IV injection of brexanolone, 90 μg/kg per hour (BRX90) (n = 45), brexanolone, 60 μg/kg per hour (BRX60) (n = 47), or placebo (n = 46) for 60 hours in Study 1, and 108 were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive BRX90 (n = 54) or placebo (n = 54) for 60 hours in Study 2.

- The primary efficacy endpoint was change in total score on the HAM-D from baseline to 60 hours. Patients were followed until Day 30.

Outcomes

- In Study 1, at 60 hours, the least-squares (LS) mean reduction in HAM-D total score from baseline was 19.5 points (standard error [SE] 1.2) in the BRX60 group and 17.7 points (SE 1.2) in the BRX90 group, compared with 14.0 points (SE 1.1) in the placebo group.

- In Study 2, at 60 hours, the LS mean reduction in HAM-D total score from baseline was 14.6 points (SE 0.8) in the BRX90 group compared with 12.1 points (SE 0.8) for the placebo group.

- In Study 1, one patient in the BRX60 group had 2 serious adverse events (suicidal ideation and intentional overdose attempt during follow-up). In Study 2, one patient in the BRX90 group had 2 serious adverse events (altered state of consciousness and syncope), which were considered treatment-related.

Conclusion

- Administration of brexanolone injection for postpartum depression resulted in significant, clinically meaningful reductions in HAM-D total score at 60 hours compared with placebo, with a rapid onset of action and durable treatment response during the study period. These results suggest that brexanolone injection has the potential to improve treatment options for women with this disorder.

Continue to: #5

5. Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Mehtälä J, et al. Association of antipsychotic polypharmacy vs monotherapy with psychiatric rehospitalization among adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):499-507.

In clinical practice, the use of multiple antipsychotic agents for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia is common but generally not recommended. The effectiveness of antipsychotic polypharmacy in preventing relapse of schizophrenia has not been established, and whether specific antipsychotic combinations are superior to monotherapies for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia is unknown. Tiihonen et al6 investigated the association of specific antipsychotic combinations with psychiatric rehospitalization, which was used as a marker for relapse.

Study design

- This study included 62,250 patients with schizophrenia, treated between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2015, in a comprehensive, nationwide cohort in Finland. Overall, 31,257 individuals (50.2%) were men, and the median age was 45.6 (interquartile range, 34.6 to 57.9).

- Patients were receiving 29 different antipsychotic monotherapy or polypharmacy regimens.

- Researchers analyzed data from April 24 to June 15, 2018 using psychiatric rehospitalization as a marker for relapse. To minimize selection bias, rehospitalization risks were investigated using within-individual analyses.

- The main outcome was the hazard ratio (HR) for psychiatric rehospitalization during use of polypharmacy vs monotherapy by the same patient.

Outcomes

- Clozapine plus aripiprazole was associated with the lowest risk of psychiatric rehospitalization, with a difference of 14% (HR, .86; CI, .79 to .94) compared with clozapine monotherapy in the analysis that included all polypharmacy periods, and 18% (HR, .82; CI, .75 to .89) in the conservatively defined polypharmacy analysis that excluded periods <90 days.

- Among patients experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia, the differences between clozapine plus aripiprazole vs clozapine monotherapy were greater, with a difference of 22% in the analysis that included all polypharmacy periods, and 23% in the conservatively defined polypharmacy analysis.

- At the aggregate level, any antipsychotic polypharmacy was associated with a 7% to 13% lower risk of psychiatric rehospitalization compared with any monotherapy.

- Clozapine was the only monotherapy among the 10 best treatments.

- Results on all-cause and somatic hospitalization, mortality, and other sensitivity analyses were in line with the primary outcomes.

Conclusion

- This study suggests that certain types of antipsychotic polypharmacy may reduce the risk of rehospitalization in patients with schizophrenia. Current treatment guidelines state that clinicians should prefer antipsychotic monotherapy and avoid polypharmacy. Tiihonen et al6 raise the question whether current treatment guidelines should continue to discourage antipsychotic polypharmacy in the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia.

- Despite the large administrative databases and sophisticated statistical methods used in this study, this approach has important limitations. As Goff10 points out, despite efforts to minimize bias, these results should be considered preliminary until confirmed by RCTs.

6. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic medications in patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):508-515.

In routine clinical practice, patients with schizophrenia are often treated with combinations of antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications. However, there is little evidence about the comparative effectiveness of these adjunctive treatment strategies. Stroup et al7 investigated the comparative real-world effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic treatments for patients with schizophrenia.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- This comparative effectiveness study used US Medicaid data from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2010. Data analysis was performed from January 1, 2017, to June 30, 2018.

- The study cohort included 81,921 adult outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia with a mean age of 40.7 (range: 18 to 64), including 37,515 women (45.8%). All patients were stably treated with a single antipsychotic and then started on an adjunctive antidepressant (n = 31,117), benzodiazepine (n = 11,941), mood stabilizer (n = 12,849), or another antipsychotic (n = 26,014).

- Researchers used multinomial logistic regression models to estimate propensity scores to balance covariates across the 4 medication groups. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to compare treatment outcomes during 365 days on an intention-to-treat basis.

- The main outcomes and measures included risk of hospitalization for a mental disorder (primary), emergency department (ED) visits for a mental disorder, and all-cause mortality.

Outcomes

- Compared with starting another antipsychotic, initiating use of an antidepressant was associated with a lower risk of psychiatric hospitalization, and initiating use of a benzodiazepine was associated with a higher risk. Initiating use of a mood stabilizer was not significantly different from initiating use of another antipsychotic.

- A similar pattern of associations was observed in psychiatric ED visits for initiating use of an antidepressant, benzodiazepine, or mood stabilizer.

- Initiating use of a mood stabilizer was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Conclusion

- Compared with the addition of a second antipsychotic, adding an antidepressant was associated with substantially reduced rates of hospitalization, whereas adding a benzodiazepine was associated with a modest increase in the risk of hospitalization. While the addition of a mood stabilizer was not associated with a significant difference in the risk of hospitalization, it was associated with higher mortality.

- Despite the limitations associated with this study, the associations of benzodiazepines and mood stabilizers with poorer outcomes warrant clinical caution and further investigation.

Bottom Line

Significantly higher epigenetic aging has been observed in patients with major depressive disorder. Haloperidol plus lorazepam might be an effective treatment for delirium; and ramelteon may be effective for preventing delirium. Prazosin reduces heavy drinking in patients with alcohol use disorder. A 60-hour infusion of brexanolone can help alleviate postpartum depression. Clozapine plus aripiprazole reduces the risk of rehospitalization among patients with schizophrenia. Adding an antidepressant to an antipsychotic also can reduce the risk of rehospitalization among patients with schizophrenia.

Related Resources

- NEJM Journal Watch. www.jwatch.org.

- F1000 Prime. https://f1000.com/prime/home.

- BMJ Journals Evidence-Based Mental Health. https://ebmh.bmj.com.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Prazosin • Minipress

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Saeed SA, Stanley JB. Top research findings of 2018-2019. First of 2 parts. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):13-18.

2. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.

3. Wu YC, Tseng PT, Tu YK, et al. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526-535.

4. Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Stappenbeck C, et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1216-1224.

5. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

6. Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Mehtälä J, et al. Association of antipsychotic polypharmacy vs monotherapy with psychiatric rehospitalization among adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):499-507.

7. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic medications in patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):508-515.

8. Blazer DG. Pharmacologic intervention for the treatment and prevention of delirium: looking beneath the modeling. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):472-473.

9. Koob GF. Brain stress systems in the amygdala and addiction. Brain Res. 2009;1293:61-75.

10. Goff DC. Can adjunctive pharmacotherapy reduce hospitalization in schizophrenia? Insights from administrative databases. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):468-469.

In Part 1 of this article, published in

1. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.

In light of the association of major depressive disorder (MDD) with an increased risk of aging-related diseases, Han et al2 examined whether MDD was associated with higher epigenetic aging in blood as measured by DNA methylation patterns. They also studied whether clinical characteristics of MDD had a further impact on these patterns, and whether the findings replicated in brain tissue. Many differentially methylated regions of our DNA tend to change as we age. Han et al2 used these age-sensitive differentially methylated regions to estimate chronological age, using DNA extracted from various tissues, including blood and brain.

Study design

- As a part of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), this study included 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants with no lifetime psychiatric disorders and low depressive symptoms (Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology score <14).

- Diagnosis of MDD and clinical characteristics were assessed by questionnaires and psychiatric interviews. Childhood trauma was assessed using the NEMESIS childhood trauma interview, which included a structured inventory of trauma exposure during childhood.

- DNA methylation age was estimated using all methylation sites in the blood of 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants. The residuals of the DNA methylation age estimates regressed on chronological age were calculated to indicate epigenetic aging.

- Analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and health status.

- Postmortem brain samples of 74 patients with MDD and 64 control participants were used for replication.

Outcomes

- Significantly higher epigenetic aging was observed in patients with MDD compared with control participants (Cohen’s d = 0.18), which suggests that patients with MDD are biologically older than their corresponding chronological age. There was a significant dose effect with increasing symptom severity in the overall sample.

- In the MDD group, epigenetic aging was positively and significantly associated with childhood trauma.

- The case-control difference was replicated in an independent analysis of postmortem brain samples.

Conclusion

- These findings suggest that patients with MDD and people with a history of childhood trauma may biologically age relatively faster than those without MDD or childhood trauma. These findings may represent a biomarker of aging and might help identify patients who may benefit from early and intensive interventions to reduce the physical comorbidities of MDD.

- This study raises the possibility that MDD may be causally related to epigenetic age acceleration. However, it only points out the associations; there are other possible explanations for this correlation, including the possibility that a shared risk factor accounts for the observed association.

2. Wu YC, Tseng PT, Tu YK, et al. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526-535.

Delirium is common and often goes underdiagnosed. It is particularly prevalent among hospitalized geriatric patients. Several medications have been suggested to have a role in treating or preventing delirium. However, it remains uncertain which medications provide the best response rate, the lowest rate of delirium occurrence, and the best tolerability. In an attempt to find answers to these questions, Wu et al3 reviewed studies that evaluated the use of various medications used for delirium.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated various pharmacologic agents used to treat or prevent delirium.

- Fifty-eight RCTs were included in the analyses. Of these, 20 RCTs with a total of 1,435 participants compared the outcomes of treatments of delirium, and 38 RCTs with a total of 8,168 participants examined prevention.

- A network meta-analysis was performed to determine if an agent or combinations of agents were superior to placebo or widely used medications.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam provided the best response rate for treating delirium compared with placebo/control.

- For delirium prevention, patients who received ramelteon, olanzapine, risperidone, or dexmedetomidine had significantly lower delirium occurrence rates than those receiving placebo/control.

- None of the pharmacologic treatments were significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared with placebo/control.

Conclusion

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam might be the best treatment and ramelteon the best preventive medicine for delirium. None of the pharmacologic interventions for treatment or prophylaxis increased all-cause mortality.

- However, network meta-analyses involve extrapolating treatment comparisons that are not made directly. As Blazer8 pointed out, both findings in this study (that haloperidol plus lorazepam is a unique intervention among the treatment trials and ramelteon is a unique intervention for prevention) seemed to be driven by 2 of the 58 studies that Wu et al3 examined.Wu et al3 also cautioned that both of these interventions needed to be further researched for efficacy.

3. Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Stappenbeck C, et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1216-1224.

While some evidence suggests that elevated brain noradrenergic activity is involved in the initiation and maintenance of alcohol use disorder,9 current medications used to treat alcohol use disorder do not target brain noradrenergic pathways. In an RCT, Simpson et al4 tested prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, for the treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Study design

- In this 12-week double-blind study, 92 participants with alcohol use disorder were randomly assigned to receive prazosin or placebo. Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder were excluded.

- Prazosin was titrated to a target dosing schedule of 4 mg in the morning, 4 mg in the afternoon, and 8 mg at bedtime by the end of Week 2. The behavioral platform was medical management. Participants provided daily data on their alcohol consumption.

- Generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to examine the impact of prazosin compared with placebo on number of drinks per week, number of drinking days per week, and number of heavy drinking days per week.

Outcomes

- Among the 80 participants who completed the titration period and were included in the primary analyses, prazosin was associated with self-reported fewer heavy drinking days, and fewer drinks per week (Palatino LT Std−8 vs Palatino LT Std−1.5 with placebo). Drinking days per week and craving showed no group differences.

- The rate of drinking and the probability of heavy drinking showed a greater decrease over time for participants receiving prazosin compared with those receiving placebo.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- These findings of moderate reductions in heavy drinking days and drinks per week with prazosin suggest that prazosin may be a promising harm-reduction treatment for alcohol use disorder.

4. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

Postpartum depression is among the most common complications of childbirth. It can result in considerable suffering for mothers, children, and families. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling has previously been reported to be involved in the pathophysiology of postpartum depression. Meltzer-Brody et al5 conducted 2 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials comparing brexanolone with placebo in women with postpartum depression at 30 clinical research centers and specialized psychiatric units in the United States.

Study design

- Participants were women age 18 to 45, Palatino LT Std≤6 months postpartum at screening, with postpartum depression as indicated by a qualifying 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score of ≥26 for Study 1 or 20 to 25 for Study 2.

- Of the 375 women who were screened simultaneously across both studies, 138 were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive a single IV injection of brexanolone, 90 μg/kg per hour (BRX90) (n = 45), brexanolone, 60 μg/kg per hour (BRX60) (n = 47), or placebo (n = 46) for 60 hours in Study 1, and 108 were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive BRX90 (n = 54) or placebo (n = 54) for 60 hours in Study 2.

- The primary efficacy endpoint was change in total score on the HAM-D from baseline to 60 hours. Patients were followed until Day 30.

Outcomes

- In Study 1, at 60 hours, the least-squares (LS) mean reduction in HAM-D total score from baseline was 19.5 points (standard error [SE] 1.2) in the BRX60 group and 17.7 points (SE 1.2) in the BRX90 group, compared with 14.0 points (SE 1.1) in the placebo group.

- In Study 2, at 60 hours, the LS mean reduction in HAM-D total score from baseline was 14.6 points (SE 0.8) in the BRX90 group compared with 12.1 points (SE 0.8) for the placebo group.

- In Study 1, one patient in the BRX60 group had 2 serious adverse events (suicidal ideation and intentional overdose attempt during follow-up). In Study 2, one patient in the BRX90 group had 2 serious adverse events (altered state of consciousness and syncope), which were considered treatment-related.

Conclusion

- Administration of brexanolone injection for postpartum depression resulted in significant, clinically meaningful reductions in HAM-D total score at 60 hours compared with placebo, with a rapid onset of action and durable treatment response during the study period. These results suggest that brexanolone injection has the potential to improve treatment options for women with this disorder.

Continue to: #5

5. Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Mehtälä J, et al. Association of antipsychotic polypharmacy vs monotherapy with psychiatric rehospitalization among adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):499-507.

In clinical practice, the use of multiple antipsychotic agents for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia is common but generally not recommended. The effectiveness of antipsychotic polypharmacy in preventing relapse of schizophrenia has not been established, and whether specific antipsychotic combinations are superior to monotherapies for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia is unknown. Tiihonen et al6 investigated the association of specific antipsychotic combinations with psychiatric rehospitalization, which was used as a marker for relapse.

Study design

- This study included 62,250 patients with schizophrenia, treated between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2015, in a comprehensive, nationwide cohort in Finland. Overall, 31,257 individuals (50.2%) were men, and the median age was 45.6 (interquartile range, 34.6 to 57.9).

- Patients were receiving 29 different antipsychotic monotherapy or polypharmacy regimens.

- Researchers analyzed data from April 24 to June 15, 2018 using psychiatric rehospitalization as a marker for relapse. To minimize selection bias, rehospitalization risks were investigated using within-individual analyses.

- The main outcome was the hazard ratio (HR) for psychiatric rehospitalization during use of polypharmacy vs monotherapy by the same patient.

Outcomes

- Clozapine plus aripiprazole was associated with the lowest risk of psychiatric rehospitalization, with a difference of 14% (HR, .86; CI, .79 to .94) compared with clozapine monotherapy in the analysis that included all polypharmacy periods, and 18% (HR, .82; CI, .75 to .89) in the conservatively defined polypharmacy analysis that excluded periods <90 days.

- Among patients experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia, the differences between clozapine plus aripiprazole vs clozapine monotherapy were greater, with a difference of 22% in the analysis that included all polypharmacy periods, and 23% in the conservatively defined polypharmacy analysis.

- At the aggregate level, any antipsychotic polypharmacy was associated with a 7% to 13% lower risk of psychiatric rehospitalization compared with any monotherapy.

- Clozapine was the only monotherapy among the 10 best treatments.

- Results on all-cause and somatic hospitalization, mortality, and other sensitivity analyses were in line with the primary outcomes.

Conclusion

- This study suggests that certain types of antipsychotic polypharmacy may reduce the risk of rehospitalization in patients with schizophrenia. Current treatment guidelines state that clinicians should prefer antipsychotic monotherapy and avoid polypharmacy. Tiihonen et al6 raise the question whether current treatment guidelines should continue to discourage antipsychotic polypharmacy in the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia.

- Despite the large administrative databases and sophisticated statistical methods used in this study, this approach has important limitations. As Goff10 points out, despite efforts to minimize bias, these results should be considered preliminary until confirmed by RCTs.

6. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic medications in patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):508-515.

In routine clinical practice, patients with schizophrenia are often treated with combinations of antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications. However, there is little evidence about the comparative effectiveness of these adjunctive treatment strategies. Stroup et al7 investigated the comparative real-world effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic treatments for patients with schizophrenia.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- This comparative effectiveness study used US Medicaid data from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2010. Data analysis was performed from January 1, 2017, to June 30, 2018.

- The study cohort included 81,921 adult outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia with a mean age of 40.7 (range: 18 to 64), including 37,515 women (45.8%). All patients were stably treated with a single antipsychotic and then started on an adjunctive antidepressant (n = 31,117), benzodiazepine (n = 11,941), mood stabilizer (n = 12,849), or another antipsychotic (n = 26,014).

- Researchers used multinomial logistic regression models to estimate propensity scores to balance covariates across the 4 medication groups. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to compare treatment outcomes during 365 days on an intention-to-treat basis.

- The main outcomes and measures included risk of hospitalization for a mental disorder (primary), emergency department (ED) visits for a mental disorder, and all-cause mortality.

Outcomes

- Compared with starting another antipsychotic, initiating use of an antidepressant was associated with a lower risk of psychiatric hospitalization, and initiating use of a benzodiazepine was associated with a higher risk. Initiating use of a mood stabilizer was not significantly different from initiating use of another antipsychotic.

- A similar pattern of associations was observed in psychiatric ED visits for initiating use of an antidepressant, benzodiazepine, or mood stabilizer.

- Initiating use of a mood stabilizer was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Conclusion

- Compared with the addition of a second antipsychotic, adding an antidepressant was associated with substantially reduced rates of hospitalization, whereas adding a benzodiazepine was associated with a modest increase in the risk of hospitalization. While the addition of a mood stabilizer was not associated with a significant difference in the risk of hospitalization, it was associated with higher mortality.

- Despite the limitations associated with this study, the associations of benzodiazepines and mood stabilizers with poorer outcomes warrant clinical caution and further investigation.

Bottom Line

Significantly higher epigenetic aging has been observed in patients with major depressive disorder. Haloperidol plus lorazepam might be an effective treatment for delirium; and ramelteon may be effective for preventing delirium. Prazosin reduces heavy drinking in patients with alcohol use disorder. A 60-hour infusion of brexanolone can help alleviate postpartum depression. Clozapine plus aripiprazole reduces the risk of rehospitalization among patients with schizophrenia. Adding an antidepressant to an antipsychotic also can reduce the risk of rehospitalization among patients with schizophrenia.

Related Resources

- NEJM Journal Watch. www.jwatch.org.

- F1000 Prime. https://f1000.com/prime/home.

- BMJ Journals Evidence-Based Mental Health. https://ebmh.bmj.com.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Prazosin • Minipress

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Risperidone • Risperdal

In Part 1 of this article, published in

1. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.

In light of the association of major depressive disorder (MDD) with an increased risk of aging-related diseases, Han et al2 examined whether MDD was associated with higher epigenetic aging in blood as measured by DNA methylation patterns. They also studied whether clinical characteristics of MDD had a further impact on these patterns, and whether the findings replicated in brain tissue. Many differentially methylated regions of our DNA tend to change as we age. Han et al2 used these age-sensitive differentially methylated regions to estimate chronological age, using DNA extracted from various tissues, including blood and brain.

Study design

- As a part of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), this study included 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants with no lifetime psychiatric disorders and low depressive symptoms (Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology score <14).

- Diagnosis of MDD and clinical characteristics were assessed by questionnaires and psychiatric interviews. Childhood trauma was assessed using the NEMESIS childhood trauma interview, which included a structured inventory of trauma exposure during childhood.

- DNA methylation age was estimated using all methylation sites in the blood of 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants. The residuals of the DNA methylation age estimates regressed on chronological age were calculated to indicate epigenetic aging.

- Analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and health status.

- Postmortem brain samples of 74 patients with MDD and 64 control participants were used for replication.

Outcomes

- Significantly higher epigenetic aging was observed in patients with MDD compared with control participants (Cohen’s d = 0.18), which suggests that patients with MDD are biologically older than their corresponding chronological age. There was a significant dose effect with increasing symptom severity in the overall sample.

- In the MDD group, epigenetic aging was positively and significantly associated with childhood trauma.

- The case-control difference was replicated in an independent analysis of postmortem brain samples.

Conclusion

- These findings suggest that patients with MDD and people with a history of childhood trauma may biologically age relatively faster than those without MDD or childhood trauma. These findings may represent a biomarker of aging and might help identify patients who may benefit from early and intensive interventions to reduce the physical comorbidities of MDD.

- This study raises the possibility that MDD may be causally related to epigenetic age acceleration. However, it only points out the associations; there are other possible explanations for this correlation, including the possibility that a shared risk factor accounts for the observed association.

2. Wu YC, Tseng PT, Tu YK, et al. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526-535.

Delirium is common and often goes underdiagnosed. It is particularly prevalent among hospitalized geriatric patients. Several medications have been suggested to have a role in treating or preventing delirium. However, it remains uncertain which medications provide the best response rate, the lowest rate of delirium occurrence, and the best tolerability. In an attempt to find answers to these questions, Wu et al3 reviewed studies that evaluated the use of various medications used for delirium.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated various pharmacologic agents used to treat or prevent delirium.

- Fifty-eight RCTs were included in the analyses. Of these, 20 RCTs with a total of 1,435 participants compared the outcomes of treatments of delirium, and 38 RCTs with a total of 8,168 participants examined prevention.

- A network meta-analysis was performed to determine if an agent or combinations of agents were superior to placebo or widely used medications.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam provided the best response rate for treating delirium compared with placebo/control.

- For delirium prevention, patients who received ramelteon, olanzapine, risperidone, or dexmedetomidine had significantly lower delirium occurrence rates than those receiving placebo/control.

- None of the pharmacologic treatments were significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared with placebo/control.