User login

FDA approves intranasal esketamine for refractory major depressive disorder

The spray (Spravato; Janssen Pharmaceuticals) will come in tamper-resistant prepackaged units of one, two, or three devices to deliver the prescribed doses of 28 mg, 56 mg, or 84 mg, respectively. To reduce the risk of diversion, misuse, or abuse, the drug will managed under an FDA Risk Evaluation and Management Strategy (REMS). It will only be available to prescribing clinicians who have undergone training on the risks of esketamine and the importance of monitoring patients after their dose is administered. Facilities licensed to dispense esketamine must have the ability to medically monitor patients for at least 2 hours after administration. Patients will self-administer the spray and will not be able to take any of it home.

The REMS will require both prescriber and the patient to both sign a Patient Enrollment Form clearly stating that patients understand the necessity of assisted transport to leave the health care facility and that there should be no driving or use of heavy machinery for the rest of the day on which they are treated.

A boxed warning on the label will note that patients are at risk for sedation and difficulty with attention, judgment, and thinking (dissociation); abuse and misuse; and suicidal thoughts and behaviors after administration of the drug.

Despite the FDA’s caveats, the approval of intranasal esketamine is seen as a substantial win for the psychiatric community, Tiffany Farchione, MD, acting director of the FDA division of psychiatry products, said in a statement. “There has been a long-standing need for additional effective treatments for treatment-resistant depression, a serious and life-threatening condition.”

“Spravato has the potential to change the treatment paradigm and offer new hope to the estimated one-third of people with major depressive disorder who have not responded to existing therapies,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of Janssen Research and Development.

The company “is working quickly to educate and certify treatment centers in accordance with the REMS so that health care providers can offer Spravato to appropriate patients,” according to a statement from Janssen. “Later this month, patients can visit www.SPRAVATO.com for a locater tool and to sign up to receive alerts when new treatment centers are available.”

Intranasal esketamine was evaluated in three short-term clinical trials and one longer-term maintenance-of-effect trial. One of the studies demonstrated a clinically significant effect in depression severity, in as little as 2 days for some patients. The two other short-term trials did not show significant benefit. However, in the maintenance study, patients in stable remission or with stable response who continued treatment with esketamine plus an oral antidepressant experienced a significantly longer time to relapse of depressive symptoms than patients on placebo spray plus an oral antidepressant. The most common side effects were disassociation, dizziness, nausea, sedation, vertigo, hypoesthesia, anxiety, lethargy, increased blood pressure, vomiting, and feeling drunk.

Patients with unstable or poorly controlled hypertension or pre-existing aneurysmal vascular disorders might be at increased risk for adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular effects. Esketamine might impair attention, judgment, thinking, reaction speed, and motor skills. It may cause fetal harm; women of childbearing age should be on reliable contraception. Breastfeeding women should not use it.

.

I’m not surprised by the FDA decision, given the strong endorsement from the advisory committees in mid-February based on the drug’s benefit-to-risk evaluation. This is an important advance for our field, and the FDA approval will allow more patients who suffer from treatment-resistant depression to gain access to this medication.

To date, ketamine (not the intranasal esketamine spray) has been offered primarily on a fee-for-service basis or in the context of a clinical trial. I anticipate this treatment to receive broad insurance coverage, but this remains to be determined.

Dr. Sanjay J. Mathew is the Marjorie Bintliff Johnson and Raleigh White Johnson Jr. Vice Chair for Research and professor in the Menninger department of psychiatry & behavioral sciences at the Baylor College of Medicine. He also is affiliated with the Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center in Houston. Dr. Mathew has served as a consultant for and has had research funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

I’m not surprised by the FDA decision, given the strong endorsement from the advisory committees in mid-February based on the drug’s benefit-to-risk evaluation. This is an important advance for our field, and the FDA approval will allow more patients who suffer from treatment-resistant depression to gain access to this medication.

To date, ketamine (not the intranasal esketamine spray) has been offered primarily on a fee-for-service basis or in the context of a clinical trial. I anticipate this treatment to receive broad insurance coverage, but this remains to be determined.

Dr. Sanjay J. Mathew is the Marjorie Bintliff Johnson and Raleigh White Johnson Jr. Vice Chair for Research and professor in the Menninger department of psychiatry & behavioral sciences at the Baylor College of Medicine. He also is affiliated with the Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center in Houston. Dr. Mathew has served as a consultant for and has had research funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

I’m not surprised by the FDA decision, given the strong endorsement from the advisory committees in mid-February based on the drug’s benefit-to-risk evaluation. This is an important advance for our field, and the FDA approval will allow more patients who suffer from treatment-resistant depression to gain access to this medication.

To date, ketamine (not the intranasal esketamine spray) has been offered primarily on a fee-for-service basis or in the context of a clinical trial. I anticipate this treatment to receive broad insurance coverage, but this remains to be determined.

Dr. Sanjay J. Mathew is the Marjorie Bintliff Johnson and Raleigh White Johnson Jr. Vice Chair for Research and professor in the Menninger department of psychiatry & behavioral sciences at the Baylor College of Medicine. He also is affiliated with the Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center in Houston. Dr. Mathew has served as a consultant for and has had research funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

The spray (Spravato; Janssen Pharmaceuticals) will come in tamper-resistant prepackaged units of one, two, or three devices to deliver the prescribed doses of 28 mg, 56 mg, or 84 mg, respectively. To reduce the risk of diversion, misuse, or abuse, the drug will managed under an FDA Risk Evaluation and Management Strategy (REMS). It will only be available to prescribing clinicians who have undergone training on the risks of esketamine and the importance of monitoring patients after their dose is administered. Facilities licensed to dispense esketamine must have the ability to medically monitor patients for at least 2 hours after administration. Patients will self-administer the spray and will not be able to take any of it home.

The REMS will require both prescriber and the patient to both sign a Patient Enrollment Form clearly stating that patients understand the necessity of assisted transport to leave the health care facility and that there should be no driving or use of heavy machinery for the rest of the day on which they are treated.

A boxed warning on the label will note that patients are at risk for sedation and difficulty with attention, judgment, and thinking (dissociation); abuse and misuse; and suicidal thoughts and behaviors after administration of the drug.

Despite the FDA’s caveats, the approval of intranasal esketamine is seen as a substantial win for the psychiatric community, Tiffany Farchione, MD, acting director of the FDA division of psychiatry products, said in a statement. “There has been a long-standing need for additional effective treatments for treatment-resistant depression, a serious and life-threatening condition.”

“Spravato has the potential to change the treatment paradigm and offer new hope to the estimated one-third of people with major depressive disorder who have not responded to existing therapies,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of Janssen Research and Development.

The company “is working quickly to educate and certify treatment centers in accordance with the REMS so that health care providers can offer Spravato to appropriate patients,” according to a statement from Janssen. “Later this month, patients can visit www.SPRAVATO.com for a locater tool and to sign up to receive alerts when new treatment centers are available.”

Intranasal esketamine was evaluated in three short-term clinical trials and one longer-term maintenance-of-effect trial. One of the studies demonstrated a clinically significant effect in depression severity, in as little as 2 days for some patients. The two other short-term trials did not show significant benefit. However, in the maintenance study, patients in stable remission or with stable response who continued treatment with esketamine plus an oral antidepressant experienced a significantly longer time to relapse of depressive symptoms than patients on placebo spray plus an oral antidepressant. The most common side effects were disassociation, dizziness, nausea, sedation, vertigo, hypoesthesia, anxiety, lethargy, increased blood pressure, vomiting, and feeling drunk.

Patients with unstable or poorly controlled hypertension or pre-existing aneurysmal vascular disorders might be at increased risk for adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular effects. Esketamine might impair attention, judgment, thinking, reaction speed, and motor skills. It may cause fetal harm; women of childbearing age should be on reliable contraception. Breastfeeding women should not use it.

.

The spray (Spravato; Janssen Pharmaceuticals) will come in tamper-resistant prepackaged units of one, two, or three devices to deliver the prescribed doses of 28 mg, 56 mg, or 84 mg, respectively. To reduce the risk of diversion, misuse, or abuse, the drug will managed under an FDA Risk Evaluation and Management Strategy (REMS). It will only be available to prescribing clinicians who have undergone training on the risks of esketamine and the importance of monitoring patients after their dose is administered. Facilities licensed to dispense esketamine must have the ability to medically monitor patients for at least 2 hours after administration. Patients will self-administer the spray and will not be able to take any of it home.

The REMS will require both prescriber and the patient to both sign a Patient Enrollment Form clearly stating that patients understand the necessity of assisted transport to leave the health care facility and that there should be no driving or use of heavy machinery for the rest of the day on which they are treated.

A boxed warning on the label will note that patients are at risk for sedation and difficulty with attention, judgment, and thinking (dissociation); abuse and misuse; and suicidal thoughts and behaviors after administration of the drug.

Despite the FDA’s caveats, the approval of intranasal esketamine is seen as a substantial win for the psychiatric community, Tiffany Farchione, MD, acting director of the FDA division of psychiatry products, said in a statement. “There has been a long-standing need for additional effective treatments for treatment-resistant depression, a serious and life-threatening condition.”

“Spravato has the potential to change the treatment paradigm and offer new hope to the estimated one-third of people with major depressive disorder who have not responded to existing therapies,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of Janssen Research and Development.

The company “is working quickly to educate and certify treatment centers in accordance with the REMS so that health care providers can offer Spravato to appropriate patients,” according to a statement from Janssen. “Later this month, patients can visit www.SPRAVATO.com for a locater tool and to sign up to receive alerts when new treatment centers are available.”

Intranasal esketamine was evaluated in three short-term clinical trials and one longer-term maintenance-of-effect trial. One of the studies demonstrated a clinically significant effect in depression severity, in as little as 2 days for some patients. The two other short-term trials did not show significant benefit. However, in the maintenance study, patients in stable remission or with stable response who continued treatment with esketamine plus an oral antidepressant experienced a significantly longer time to relapse of depressive symptoms than patients on placebo spray plus an oral antidepressant. The most common side effects were disassociation, dizziness, nausea, sedation, vertigo, hypoesthesia, anxiety, lethargy, increased blood pressure, vomiting, and feeling drunk.

Patients with unstable or poorly controlled hypertension or pre-existing aneurysmal vascular disorders might be at increased risk for adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular effects. Esketamine might impair attention, judgment, thinking, reaction speed, and motor skills. It may cause fetal harm; women of childbearing age should be on reliable contraception. Breastfeeding women should not use it.

.

Behavioral intervention improves physical activity in patients with diabetes

A behavioral intervention that involves regular counseling sessions could help patients with type 2 diabetes increase their levels of physical activity and decrease their amount of sedentary time, according to findings from a prospective, randomized trial of 300 physically inactive patients with type 2 diabetes.

“The primary strength of this study is the application of an intervention targeting both physical activity and sedentary time across all settings (e.g., leisure, transportation, household, and occupation), based on theoretical grounds and using several behavior-change techniques,” wrote Stefano Balducci, MD, of Sapienza University in Rome and his colleagues. The findings were published in JAMA.

Half the participants were randomized to an intervention that involved one individual theoretical counseling session with a diabetologist and eight biweekly theoretical and practical counseling sessions with an exercise specialist each year for 3 years. The other half received standard care in the form of recommendations from their general physician about increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary time. Both groups also received the same general treatment regimen according to guidelines.

The findings showed significant increases in volume of physical activity, light-intensity physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity in the intervention group during the first 4 months of the trial. Those increases also were greater than the increases seen in the usual care group. Patients in the intervention group also showed greater decreases in sedentary time, compared with those in the control group during the same time.

After 4 months, the increases in physical activity in the intervention group plateaued but remained stable until 2 years. After that, the levels of activity declined but still remained significantly higher than at baseline. The level of sedentary time also increased after 2 years but was still lower than at baseline.

By the end of the study, the intervention group accumulated 13.8 metabolic equivalent hours/week of physical activity volume, compared with 10.5 hours in the control group; 18.9 minutes/day of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity, compared with 12.5 minutes in the control group; and 4.6 hours/day of light-intensity physical activity, compared with 3.8 hours in the control group. In regard to sedentary time, the intervention group accumulated 10.9 hours/day, compared with 11.7 hours in the control group. All differences were statistically significant.

“The present findings support the need for interventions targeting all domains of behavior to obtain substantial lifestyle changes, not limited to moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity, which has little effect on sedentary time,” Dr. Balducci and his coauthors wrote. “This concept is consistent with a 2018 report showing that physical activity, sedentary time, and cardiorespiratory fitness are all important for cardiometabolic health.”

For the secondary outcomes of cardiorespiratory fitness and lower-body strength, the authors saw significant improvements in the intervention group, whereas the control group showed a worsening in those outcomes. The intervention group also showed significant improvements in fasting plasma glucose level, systolic blood pressure, total coronary heart disease 10-year risk score, and fatal coronary heart disease 10-year risk score. They also had significantly greater improvements than did the control group in total stroke risk score, hemoglobin A1c, fasting plasma glucose levels, and coronary heart disease risk.

In all, there were 41 adverse events in the intervention group, compared with 59 in the control group, outside of the sessions. During the sessions, participants in the intervention group experienced mild hypoglycemia (8 episodes), tachycardia/arrhythmia (3), and musculoskeletal injury or discomfort (19).

One of the limitations highlighted by the authors was that the benefits of their strategy could vary in other cohorts because of differences in climatic, socioeconomic, or cultural settings.

The study was supported by the Metabolic Fitness Association. Three authors declared grants and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies, and one author was an employee of Technogym. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Balducci S et al. JAMA. 2019;321:880-90.

A behavioral intervention that involves regular counseling sessions could help patients with type 2 diabetes increase their levels of physical activity and decrease their amount of sedentary time, according to findings from a prospective, randomized trial of 300 physically inactive patients with type 2 diabetes.

“The primary strength of this study is the application of an intervention targeting both physical activity and sedentary time across all settings (e.g., leisure, transportation, household, and occupation), based on theoretical grounds and using several behavior-change techniques,” wrote Stefano Balducci, MD, of Sapienza University in Rome and his colleagues. The findings were published in JAMA.

Half the participants were randomized to an intervention that involved one individual theoretical counseling session with a diabetologist and eight biweekly theoretical and practical counseling sessions with an exercise specialist each year for 3 years. The other half received standard care in the form of recommendations from their general physician about increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary time. Both groups also received the same general treatment regimen according to guidelines.

The findings showed significant increases in volume of physical activity, light-intensity physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity in the intervention group during the first 4 months of the trial. Those increases also were greater than the increases seen in the usual care group. Patients in the intervention group also showed greater decreases in sedentary time, compared with those in the control group during the same time.

After 4 months, the increases in physical activity in the intervention group plateaued but remained stable until 2 years. After that, the levels of activity declined but still remained significantly higher than at baseline. The level of sedentary time also increased after 2 years but was still lower than at baseline.

By the end of the study, the intervention group accumulated 13.8 metabolic equivalent hours/week of physical activity volume, compared with 10.5 hours in the control group; 18.9 minutes/day of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity, compared with 12.5 minutes in the control group; and 4.6 hours/day of light-intensity physical activity, compared with 3.8 hours in the control group. In regard to sedentary time, the intervention group accumulated 10.9 hours/day, compared with 11.7 hours in the control group. All differences were statistically significant.

“The present findings support the need for interventions targeting all domains of behavior to obtain substantial lifestyle changes, not limited to moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity, which has little effect on sedentary time,” Dr. Balducci and his coauthors wrote. “This concept is consistent with a 2018 report showing that physical activity, sedentary time, and cardiorespiratory fitness are all important for cardiometabolic health.”

For the secondary outcomes of cardiorespiratory fitness and lower-body strength, the authors saw significant improvements in the intervention group, whereas the control group showed a worsening in those outcomes. The intervention group also showed significant improvements in fasting plasma glucose level, systolic blood pressure, total coronary heart disease 10-year risk score, and fatal coronary heart disease 10-year risk score. They also had significantly greater improvements than did the control group in total stroke risk score, hemoglobin A1c, fasting plasma glucose levels, and coronary heart disease risk.

In all, there were 41 adverse events in the intervention group, compared with 59 in the control group, outside of the sessions. During the sessions, participants in the intervention group experienced mild hypoglycemia (8 episodes), tachycardia/arrhythmia (3), and musculoskeletal injury or discomfort (19).

One of the limitations highlighted by the authors was that the benefits of their strategy could vary in other cohorts because of differences in climatic, socioeconomic, or cultural settings.

The study was supported by the Metabolic Fitness Association. Three authors declared grants and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies, and one author was an employee of Technogym. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Balducci S et al. JAMA. 2019;321:880-90.

A behavioral intervention that involves regular counseling sessions could help patients with type 2 diabetes increase their levels of physical activity and decrease their amount of sedentary time, according to findings from a prospective, randomized trial of 300 physically inactive patients with type 2 diabetes.

“The primary strength of this study is the application of an intervention targeting both physical activity and sedentary time across all settings (e.g., leisure, transportation, household, and occupation), based on theoretical grounds and using several behavior-change techniques,” wrote Stefano Balducci, MD, of Sapienza University in Rome and his colleagues. The findings were published in JAMA.

Half the participants were randomized to an intervention that involved one individual theoretical counseling session with a diabetologist and eight biweekly theoretical and practical counseling sessions with an exercise specialist each year for 3 years. The other half received standard care in the form of recommendations from their general physician about increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary time. Both groups also received the same general treatment regimen according to guidelines.

The findings showed significant increases in volume of physical activity, light-intensity physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity in the intervention group during the first 4 months of the trial. Those increases also were greater than the increases seen in the usual care group. Patients in the intervention group also showed greater decreases in sedentary time, compared with those in the control group during the same time.

After 4 months, the increases in physical activity in the intervention group plateaued but remained stable until 2 years. After that, the levels of activity declined but still remained significantly higher than at baseline. The level of sedentary time also increased after 2 years but was still lower than at baseline.

By the end of the study, the intervention group accumulated 13.8 metabolic equivalent hours/week of physical activity volume, compared with 10.5 hours in the control group; 18.9 minutes/day of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity, compared with 12.5 minutes in the control group; and 4.6 hours/day of light-intensity physical activity, compared with 3.8 hours in the control group. In regard to sedentary time, the intervention group accumulated 10.9 hours/day, compared with 11.7 hours in the control group. All differences were statistically significant.

“The present findings support the need for interventions targeting all domains of behavior to obtain substantial lifestyle changes, not limited to moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity, which has little effect on sedentary time,” Dr. Balducci and his coauthors wrote. “This concept is consistent with a 2018 report showing that physical activity, sedentary time, and cardiorespiratory fitness are all important for cardiometabolic health.”

For the secondary outcomes of cardiorespiratory fitness and lower-body strength, the authors saw significant improvements in the intervention group, whereas the control group showed a worsening in those outcomes. The intervention group also showed significant improvements in fasting plasma glucose level, systolic blood pressure, total coronary heart disease 10-year risk score, and fatal coronary heart disease 10-year risk score. They also had significantly greater improvements than did the control group in total stroke risk score, hemoglobin A1c, fasting plasma glucose levels, and coronary heart disease risk.

In all, there were 41 adverse events in the intervention group, compared with 59 in the control group, outside of the sessions. During the sessions, participants in the intervention group experienced mild hypoglycemia (8 episodes), tachycardia/arrhythmia (3), and musculoskeletal injury or discomfort (19).

One of the limitations highlighted by the authors was that the benefits of their strategy could vary in other cohorts because of differences in climatic, socioeconomic, or cultural settings.

The study was supported by the Metabolic Fitness Association. Three authors declared grants and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies, and one author was an employee of Technogym. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Balducci S et al. JAMA. 2019;321:880-90.

FROM JAMA

Supplements and food-related therapy do not prevent depression in overweight adults

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: A combination of multinutrient supplements and food-related behavioral activation therapy did not reduce episodes of major depressive disorder in overweight adults.

Major finding: Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy.

Study details: A 2 x 2 factorial randomized clinical trial of 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries with elevated depressive symptoms and no major depressive disorder episode in the past 6 months.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

Source: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

Watch for depression symptom trajectory in high-risk young adults

Severity, variability of symptoms may be only predictor of suicide attempts.

Among the trajectories of clinical predictors of suicide attempt, depression symptoms were the only ones linked with an increased risk of suicide attempt in young adults whose parents have mood disorders, according to a longitudinal study.

Psychiatric diagnoses are well established as predictors of suicidal behavior; however, symptoms and risk can vary over the course of illness, and it is important to identify symptoms that can change over time, wrote Nadine M. Melhem, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and her associates. The report is in JAMA Psychiatry.

Between July 15, 1997, and Sept. 6, 2005, 663 adolescents and young adults (mean age, 23.8 years) whose parents have mood disorders were recruited and followed until Jan. 21, 2014. All participants were assessed at baseline and every year for up to 12 years (median follow-up, 8.1 years) for lifetime and current psychiatric disorders as well as suicidal ideation. In addition, participants were assessed at baseline and at each follow-up for the trajectory of depression symptoms, hopelessness, impulsivity, aggression, impulsive aggression, and irritability.

After the study period, participants were analyzed for all trajectories and separated into classes based on mean scores and variability. All trajectories except for depression had two classes, in which participants in class 2 had higher mean scores and variability; for depression, patients were separated into three classes, in which class 3 had the highest mean score and variability.

Over the study period, 71 of the 663 patients attempted suicide (10.7%), with 51 patients attempting suicide for the first time. The mean number of attempts was 1.2, and the median time from the last assessment to the attempt was 45 weeks.

(22.9% with vs. 27 without), class 2 impulsivity (38.8% vs. 21.7%), class 2 aggression (29.0% vs. 15.6%), class 2 impulsive aggression (76.5% vs. 52.2%), and class 2 irritability (39.4% vs. 22.7%). However, after adjustment for demographics, parental suicide attempts, and additional clinical characteristics, only class 3 depression remained associated with suicide attempts (odds ratio, 4.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-15.21; P = .01).

Other significant predictors of suicide attempts were younger age (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74-0.90; P less than .001), lifetime history of unipolar disorder (OR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.63-13.58; P = .004), lifetime history of bipolar disorder (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 0.96-12.04; P = .06), history of childhood abuse (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.40-6.38; P = .01), and parental suicide attempt (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.06-4.75; P = .04).

The investigators concluded that clinicians should “pay particular attention to the severity of both current and past depression and the variability in these symptoms, and monitor and treat depression symptoms over time to reduce symptom severity and fluctuation, and thus the likelihood for suicide attempt, in high-risk young adults.”

Dr. Melhem reported receiving research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Several other coauthors also reported conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Melhem NM et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4513.

Severity, variability of symptoms may be only predictor of suicide attempts.

Severity, variability of symptoms may be only predictor of suicide attempts.

Among the trajectories of clinical predictors of suicide attempt, depression symptoms were the only ones linked with an increased risk of suicide attempt in young adults whose parents have mood disorders, according to a longitudinal study.

Psychiatric diagnoses are well established as predictors of suicidal behavior; however, symptoms and risk can vary over the course of illness, and it is important to identify symptoms that can change over time, wrote Nadine M. Melhem, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and her associates. The report is in JAMA Psychiatry.

Between July 15, 1997, and Sept. 6, 2005, 663 adolescents and young adults (mean age, 23.8 years) whose parents have mood disorders were recruited and followed until Jan. 21, 2014. All participants were assessed at baseline and every year for up to 12 years (median follow-up, 8.1 years) for lifetime and current psychiatric disorders as well as suicidal ideation. In addition, participants were assessed at baseline and at each follow-up for the trajectory of depression symptoms, hopelessness, impulsivity, aggression, impulsive aggression, and irritability.

After the study period, participants were analyzed for all trajectories and separated into classes based on mean scores and variability. All trajectories except for depression had two classes, in which participants in class 2 had higher mean scores and variability; for depression, patients were separated into three classes, in which class 3 had the highest mean score and variability.

Over the study period, 71 of the 663 patients attempted suicide (10.7%), with 51 patients attempting suicide for the first time. The mean number of attempts was 1.2, and the median time from the last assessment to the attempt was 45 weeks.

(22.9% with vs. 27 without), class 2 impulsivity (38.8% vs. 21.7%), class 2 aggression (29.0% vs. 15.6%), class 2 impulsive aggression (76.5% vs. 52.2%), and class 2 irritability (39.4% vs. 22.7%). However, after adjustment for demographics, parental suicide attempts, and additional clinical characteristics, only class 3 depression remained associated with suicide attempts (odds ratio, 4.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-15.21; P = .01).

Other significant predictors of suicide attempts were younger age (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74-0.90; P less than .001), lifetime history of unipolar disorder (OR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.63-13.58; P = .004), lifetime history of bipolar disorder (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 0.96-12.04; P = .06), history of childhood abuse (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.40-6.38; P = .01), and parental suicide attempt (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.06-4.75; P = .04).

The investigators concluded that clinicians should “pay particular attention to the severity of both current and past depression and the variability in these symptoms, and monitor and treat depression symptoms over time to reduce symptom severity and fluctuation, and thus the likelihood for suicide attempt, in high-risk young adults.”

Dr. Melhem reported receiving research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Several other coauthors also reported conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Melhem NM et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4513.

Among the trajectories of clinical predictors of suicide attempt, depression symptoms were the only ones linked with an increased risk of suicide attempt in young adults whose parents have mood disorders, according to a longitudinal study.

Psychiatric diagnoses are well established as predictors of suicidal behavior; however, symptoms and risk can vary over the course of illness, and it is important to identify symptoms that can change over time, wrote Nadine M. Melhem, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and her associates. The report is in JAMA Psychiatry.

Between July 15, 1997, and Sept. 6, 2005, 663 adolescents and young adults (mean age, 23.8 years) whose parents have mood disorders were recruited and followed until Jan. 21, 2014. All participants were assessed at baseline and every year for up to 12 years (median follow-up, 8.1 years) for lifetime and current psychiatric disorders as well as suicidal ideation. In addition, participants were assessed at baseline and at each follow-up for the trajectory of depression symptoms, hopelessness, impulsivity, aggression, impulsive aggression, and irritability.

After the study period, participants were analyzed for all trajectories and separated into classes based on mean scores and variability. All trajectories except for depression had two classes, in which participants in class 2 had higher mean scores and variability; for depression, patients were separated into three classes, in which class 3 had the highest mean score and variability.

Over the study period, 71 of the 663 patients attempted suicide (10.7%), with 51 patients attempting suicide for the first time. The mean number of attempts was 1.2, and the median time from the last assessment to the attempt was 45 weeks.

(22.9% with vs. 27 without), class 2 impulsivity (38.8% vs. 21.7%), class 2 aggression (29.0% vs. 15.6%), class 2 impulsive aggression (76.5% vs. 52.2%), and class 2 irritability (39.4% vs. 22.7%). However, after adjustment for demographics, parental suicide attempts, and additional clinical characteristics, only class 3 depression remained associated with suicide attempts (odds ratio, 4.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-15.21; P = .01).

Other significant predictors of suicide attempts were younger age (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74-0.90; P less than .001), lifetime history of unipolar disorder (OR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.63-13.58; P = .004), lifetime history of bipolar disorder (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 0.96-12.04; P = .06), history of childhood abuse (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.40-6.38; P = .01), and parental suicide attempt (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.06-4.75; P = .04).

The investigators concluded that clinicians should “pay particular attention to the severity of both current and past depression and the variability in these symptoms, and monitor and treat depression symptoms over time to reduce symptom severity and fluctuation, and thus the likelihood for suicide attempt, in high-risk young adults.”

Dr. Melhem reported receiving research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Several other coauthors also reported conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Melhem NM et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4513.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Only depression symptoms were associated with a higher suicide attempt risk in young adults whose parents have mood disorders.

Major finding: The depression symptom trajectory with the highest mean scores and variability over time was the only measured trajectory that predicted suicide attempts (odds ratio, 4.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-15.21; P = .01).

Study details: A longitudinal study of 663 adolescents and younger adults whose parents have mood disorders.

Disclosures: Dr. Melhem reported receiving research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Several other coauthors also reported conflicts of interest.

Source: Melhem NM et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4513.

Management of treatment-resistant depression: A review of 3 studies

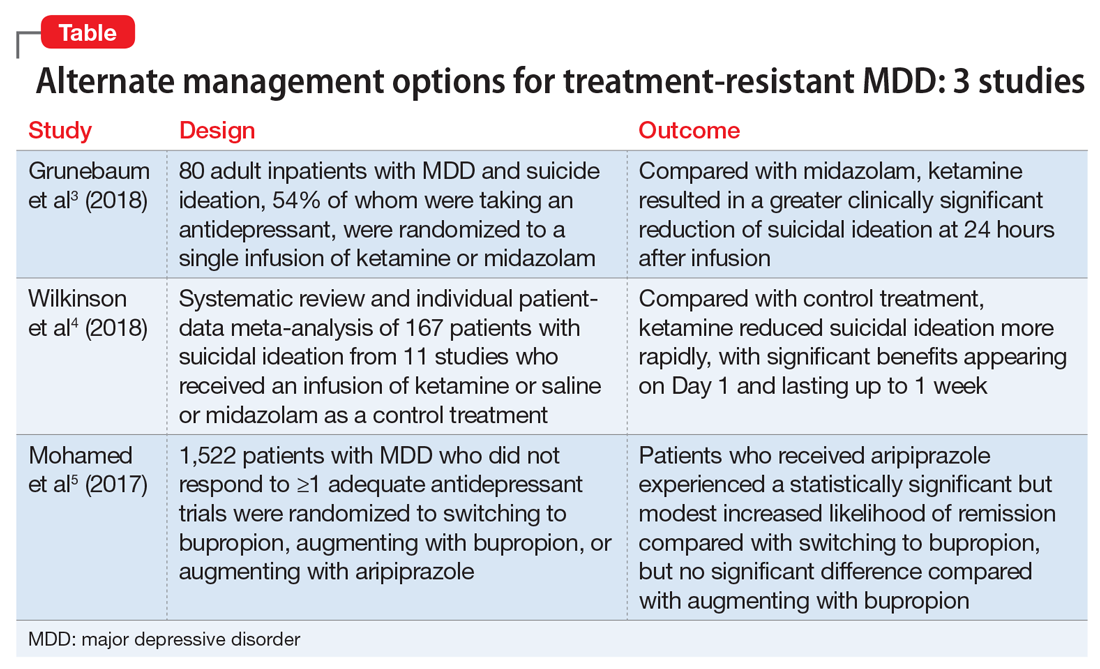

An estimated 7.1% of the adults in United States had a major depressive episode in 2017, and this prevalence has been trending upward over the past few years.1 The prevalence is even higher in adults between age 18 and 25 (13.1%).1 Like other psychiatric diagnoses, major depressive disorder (MDD) has a significant impact on productivity as well as daily functioning. Only one-third of patients with MDD achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication.2 This leaves an estimated 11.47 million people in the United States in need of an alternate regimen for management of their depressive episode.

The data on evidence-based biologic treatments for treatment-resistant depression are limited (other than for electroconvulsive therapy). Pharmacologic options include switching to a different medication, combining medications, and augmentation strategies or novel approaches such as ketamine and related agents. Here we summarize the findings from 3 recent studies that investigate alternate management options for MDD.

Ketamine: Randomized controlled trial

Traditional antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation by improving depressive symptoms, but this effect may take weeks. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

_

1. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

Grunebaum et al3 evaluated the acute effect of adjunctive subanesthetic IV ketamine on clinically significant suicidal ideation in patients with MDD, with a comparison arm that received an infusion of midazolam.

Study design

- 80 inpatients (age 18 to 65 years) with MDD who had a score ≥16 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and a score ≥4 on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI). Approximately one-half (54%) were taking an antidepressant

- Patients were randomly assigned to IV racemic ketamine hydrochloride, .5 mg/kg, or IV midazolam, .02 mg/kg, both administered in 100 mL normal saline over 40 minutes.

Outcomes

- Scale for Suicidal Ideation scores were assessed at screening, before infusion, 230 minutes after infusion, 24 hours after infusion, and after 1 to 6 weeks of follow-up. The average SSI score on Day 1 was 4.96 points lower in the ketamine group compared with the midazolam group. The proportion of responders (defined as patients who experienced a 50% reduction in SSI score) on Day 1 was 55% for patients in the ketamine group compared with 30% in the midazolam group.

Conclusion

- Compared with midazolam, ketamine produced a greater clinically meaningful reduction in suicidal ideation 24 hours after infusion.

Apart from the primary outcome of reduction in suicidal ideation, greater reductions were also found in overall mood disturbance, depression subscale, and fatigue subscale scores as assessed on the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Although the study noted improvement in depression scores, the proportion of responders on Day 1 in depression scales, including HAM-D and the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory, fell short of statistical significance. Overall, compared with the midazolam infusion, a single adjunctive subanesthetic ketamine infusion was associated with a greater clinically significant reduction in suicidal ideation on Day 1.

Continue to: Ketamine

Ketamine: Review and meta-analysis

Wilkinson et al4 conducted a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis of 11 similar comparison intervention studies examining the effects of ketamine in reducing suicidal thoughts.

2. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):150-158.

Study design

- Review of 11 studies of a single dose of IV ketamine for treatment of any psychiatric disorder. Only comparison intervention trials using saline placebo or midazolam were included:

- Individual patient-level data of 298 patients were obtained from 10 of the 11 trials. Analysis was performed on 167 patients who had suicidal ideation at baseline.

- Results were assessed by clinician-administered rating scales.

Outcomes

- Ketamine reduced suicidal ideation more rapidly compared with control infusions as assessed by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and HAM-D, with significant benefits appearing on Day 1 and extending up to Day 7. The mean MADRS score in the ketamine group decreased to 19.5 from 33.8 within 1 day of infusion, compared with a reduction to 29.2 from 32.9 in the control groups.

- The number needed to treat to be free of suicidal ideation for ketamine (compared with control) was 3.1 to 4.0 for all time points in the first week after infusion.

Conclusion

- This meta-analysis provided evidence from the largest sample to date (N = 298) that ketamine reduces suicidal ideation partially independently of mood symptoms.

While the anti-suicidal effects of ketamine appear to be robust in the above studies, the possibility of rebound suicidal ideation remains in the weeks or months following exposure. Also, these studies only prove a reduction in suicidal ideation; reduction in suicidal behavior was not studied. Nevertheless, ketamine holds considerable promise as a potential rapid-acting agent in patients at risk of suicide.

Continue to: Strategies for augmentation or switching

Strategies for augmentation or switching

Only one-third of the patients with depression achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication. The American Psychiatric Association’s current management guidelines2 for patients who do not respond to the first-choice antidepressant include multiple options. Switching strategies recommended in these guidelines include changing to an antidepressant of the same class, or to one from a different class (eg, from a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or from an SSRI to a tricyclic antidepressant). Augmentation strategies include augmenting with a non-monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressant from a different class, lithium, thyroid hormone, or an atypical antipsychotic.

The VAST-D trial5 evaluated the relative effectiveness and safety of 3 common treatments for treatment-resistant MDD:

- switching to bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with the second-generation antipsychotic aripiprazole.

3. Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

Study design

- A multi-site, randomized, single-blind, parallel-assignment trial of 1,522 patients at 35 US Veteran Health Administration medical centers with nonpsychotic MDD with a suboptimal response to at least one antidepressant (defined as a score of ≥16 on the Quick Inventory Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated questionnaire [QIDS-C16]).

- Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: switching to bupropion (n = 511), augmenting with bupropion (n = 506), or augmenting with aripiprazole (n = 505).

- The primary outcome was remission (defined as a QIDS-C16 score ≤5 at 2 consecutively scheduled follow-up visits). Secondary outcome was a reduction in QIDS-C16 score by ≥50%, or a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Improvement scale score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved).

Outcomes

- The aripiprazole group showed a modest, statistically significant remission rate (28.9%) compared with the bupropion switch group (22.3%), but did not show any statistically significant difference compared with the bupropion augmentation group.

- For the secondary outcome, there was a significantly higher response rate in the aripiprazole group (74.3%) compared with the bupropion switch group (62.4%) and bupropion augmentation group (65.6%). Response measured by the CGI– Improvement scale score also favored the aripiprazole group (79%) compared with the bupropion switch group (70%) and bupropion augmentation group (74%).

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Overall, the study found a statistically significant but modest increased likelihood of remission during 12 weeks of augmentation treatment with aripiprazole, compared with switching to bupropion monotherapy.

The studies discussed here, which are summarized in the Table,3-5 provide some potential avenues for research into interventions for patients who are acutely suicidal and those with treatment-resistant depression. Further research into long-term outcomes and adverse effects of ketamine use for suicidality in patients with depression is needed. The VAST-D trial suggests a need for further exploration into the efficacy of augmentation with second-generation antipsychotics for treatment-resistant depression.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Reports and detailed tables from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2017-NSDUH. Accessed November 12, 2018.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed November 12, 2018.

3. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

4. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):150-158.

5. Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

An estimated 7.1% of the adults in United States had a major depressive episode in 2017, and this prevalence has been trending upward over the past few years.1 The prevalence is even higher in adults between age 18 and 25 (13.1%).1 Like other psychiatric diagnoses, major depressive disorder (MDD) has a significant impact on productivity as well as daily functioning. Only one-third of patients with MDD achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication.2 This leaves an estimated 11.47 million people in the United States in need of an alternate regimen for management of their depressive episode.

The data on evidence-based biologic treatments for treatment-resistant depression are limited (other than for electroconvulsive therapy). Pharmacologic options include switching to a different medication, combining medications, and augmentation strategies or novel approaches such as ketamine and related agents. Here we summarize the findings from 3 recent studies that investigate alternate management options for MDD.

Ketamine: Randomized controlled trial

Traditional antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation by improving depressive symptoms, but this effect may take weeks. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

_

1. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

Grunebaum et al3 evaluated the acute effect of adjunctive subanesthetic IV ketamine on clinically significant suicidal ideation in patients with MDD, with a comparison arm that received an infusion of midazolam.

Study design

- 80 inpatients (age 18 to 65 years) with MDD who had a score ≥16 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and a score ≥4 on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI). Approximately one-half (54%) were taking an antidepressant

- Patients were randomly assigned to IV racemic ketamine hydrochloride, .5 mg/kg, or IV midazolam, .02 mg/kg, both administered in 100 mL normal saline over 40 minutes.

Outcomes

- Scale for Suicidal Ideation scores were assessed at screening, before infusion, 230 minutes after infusion, 24 hours after infusion, and after 1 to 6 weeks of follow-up. The average SSI score on Day 1 was 4.96 points lower in the ketamine group compared with the midazolam group. The proportion of responders (defined as patients who experienced a 50% reduction in SSI score) on Day 1 was 55% for patients in the ketamine group compared with 30% in the midazolam group.

Conclusion

- Compared with midazolam, ketamine produced a greater clinically meaningful reduction in suicidal ideation 24 hours after infusion.

Apart from the primary outcome of reduction in suicidal ideation, greater reductions were also found in overall mood disturbance, depression subscale, and fatigue subscale scores as assessed on the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Although the study noted improvement in depression scores, the proportion of responders on Day 1 in depression scales, including HAM-D and the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory, fell short of statistical significance. Overall, compared with the midazolam infusion, a single adjunctive subanesthetic ketamine infusion was associated with a greater clinically significant reduction in suicidal ideation on Day 1.

Continue to: Ketamine

Ketamine: Review and meta-analysis

Wilkinson et al4 conducted a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis of 11 similar comparison intervention studies examining the effects of ketamine in reducing suicidal thoughts.

2. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):150-158.

Study design

- Review of 11 studies of a single dose of IV ketamine for treatment of any psychiatric disorder. Only comparison intervention trials using saline placebo or midazolam were included:

- Individual patient-level data of 298 patients were obtained from 10 of the 11 trials. Analysis was performed on 167 patients who had suicidal ideation at baseline.

- Results were assessed by clinician-administered rating scales.

Outcomes

- Ketamine reduced suicidal ideation more rapidly compared with control infusions as assessed by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and HAM-D, with significant benefits appearing on Day 1 and extending up to Day 7. The mean MADRS score in the ketamine group decreased to 19.5 from 33.8 within 1 day of infusion, compared with a reduction to 29.2 from 32.9 in the control groups.

- The number needed to treat to be free of suicidal ideation for ketamine (compared with control) was 3.1 to 4.0 for all time points in the first week after infusion.

Conclusion

- This meta-analysis provided evidence from the largest sample to date (N = 298) that ketamine reduces suicidal ideation partially independently of mood symptoms.

While the anti-suicidal effects of ketamine appear to be robust in the above studies, the possibility of rebound suicidal ideation remains in the weeks or months following exposure. Also, these studies only prove a reduction in suicidal ideation; reduction in suicidal behavior was not studied. Nevertheless, ketamine holds considerable promise as a potential rapid-acting agent in patients at risk of suicide.

Continue to: Strategies for augmentation or switching

Strategies for augmentation or switching

Only one-third of the patients with depression achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication. The American Psychiatric Association’s current management guidelines2 for patients who do not respond to the first-choice antidepressant include multiple options. Switching strategies recommended in these guidelines include changing to an antidepressant of the same class, or to one from a different class (eg, from a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or from an SSRI to a tricyclic antidepressant). Augmentation strategies include augmenting with a non-monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressant from a different class, lithium, thyroid hormone, or an atypical antipsychotic.

The VAST-D trial5 evaluated the relative effectiveness and safety of 3 common treatments for treatment-resistant MDD:

- switching to bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with the second-generation antipsychotic aripiprazole.

3. Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

Study design

- A multi-site, randomized, single-blind, parallel-assignment trial of 1,522 patients at 35 US Veteran Health Administration medical centers with nonpsychotic MDD with a suboptimal response to at least one antidepressant (defined as a score of ≥16 on the Quick Inventory Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated questionnaire [QIDS-C16]).

- Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: switching to bupropion (n = 511), augmenting with bupropion (n = 506), or augmenting with aripiprazole (n = 505).

- The primary outcome was remission (defined as a QIDS-C16 score ≤5 at 2 consecutively scheduled follow-up visits). Secondary outcome was a reduction in QIDS-C16 score by ≥50%, or a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Improvement scale score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved).

Outcomes

- The aripiprazole group showed a modest, statistically significant remission rate (28.9%) compared with the bupropion switch group (22.3%), but did not show any statistically significant difference compared with the bupropion augmentation group.

- For the secondary outcome, there was a significantly higher response rate in the aripiprazole group (74.3%) compared with the bupropion switch group (62.4%) and bupropion augmentation group (65.6%). Response measured by the CGI– Improvement scale score also favored the aripiprazole group (79%) compared with the bupropion switch group (70%) and bupropion augmentation group (74%).

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Overall, the study found a statistically significant but modest increased likelihood of remission during 12 weeks of augmentation treatment with aripiprazole, compared with switching to bupropion monotherapy.

The studies discussed here, which are summarized in the Table,3-5 provide some potential avenues for research into interventions for patients who are acutely suicidal and those with treatment-resistant depression. Further research into long-term outcomes and adverse effects of ketamine use for suicidality in patients with depression is needed. The VAST-D trial suggests a need for further exploration into the efficacy of augmentation with second-generation antipsychotics for treatment-resistant depression.

An estimated 7.1% of the adults in United States had a major depressive episode in 2017, and this prevalence has been trending upward over the past few years.1 The prevalence is even higher in adults between age 18 and 25 (13.1%).1 Like other psychiatric diagnoses, major depressive disorder (MDD) has a significant impact on productivity as well as daily functioning. Only one-third of patients with MDD achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication.2 This leaves an estimated 11.47 million people in the United States in need of an alternate regimen for management of their depressive episode.

The data on evidence-based biologic treatments for treatment-resistant depression are limited (other than for electroconvulsive therapy). Pharmacologic options include switching to a different medication, combining medications, and augmentation strategies or novel approaches such as ketamine and related agents. Here we summarize the findings from 3 recent studies that investigate alternate management options for MDD.

Ketamine: Randomized controlled trial

Traditional antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation by improving depressive symptoms, but this effect may take weeks. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

_

1. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

Grunebaum et al3 evaluated the acute effect of adjunctive subanesthetic IV ketamine on clinically significant suicidal ideation in patients with MDD, with a comparison arm that received an infusion of midazolam.

Study design

- 80 inpatients (age 18 to 65 years) with MDD who had a score ≥16 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and a score ≥4 on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI). Approximately one-half (54%) were taking an antidepressant

- Patients were randomly assigned to IV racemic ketamine hydrochloride, .5 mg/kg, or IV midazolam, .02 mg/kg, both administered in 100 mL normal saline over 40 minutes.

Outcomes

- Scale for Suicidal Ideation scores were assessed at screening, before infusion, 230 minutes after infusion, 24 hours after infusion, and after 1 to 6 weeks of follow-up. The average SSI score on Day 1 was 4.96 points lower in the ketamine group compared with the midazolam group. The proportion of responders (defined as patients who experienced a 50% reduction in SSI score) on Day 1 was 55% for patients in the ketamine group compared with 30% in the midazolam group.

Conclusion

- Compared with midazolam, ketamine produced a greater clinically meaningful reduction in suicidal ideation 24 hours after infusion.

Apart from the primary outcome of reduction in suicidal ideation, greater reductions were also found in overall mood disturbance, depression subscale, and fatigue subscale scores as assessed on the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Although the study noted improvement in depression scores, the proportion of responders on Day 1 in depression scales, including HAM-D and the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory, fell short of statistical significance. Overall, compared with the midazolam infusion, a single adjunctive subanesthetic ketamine infusion was associated with a greater clinically significant reduction in suicidal ideation on Day 1.

Continue to: Ketamine

Ketamine: Review and meta-analysis

Wilkinson et al4 conducted a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis of 11 similar comparison intervention studies examining the effects of ketamine in reducing suicidal thoughts.

2. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):150-158.

Study design

- Review of 11 studies of a single dose of IV ketamine for treatment of any psychiatric disorder. Only comparison intervention trials using saline placebo or midazolam were included:

- Individual patient-level data of 298 patients were obtained from 10 of the 11 trials. Analysis was performed on 167 patients who had suicidal ideation at baseline.

- Results were assessed by clinician-administered rating scales.

Outcomes

- Ketamine reduced suicidal ideation more rapidly compared with control infusions as assessed by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and HAM-D, with significant benefits appearing on Day 1 and extending up to Day 7. The mean MADRS score in the ketamine group decreased to 19.5 from 33.8 within 1 day of infusion, compared with a reduction to 29.2 from 32.9 in the control groups.

- The number needed to treat to be free of suicidal ideation for ketamine (compared with control) was 3.1 to 4.0 for all time points in the first week after infusion.

Conclusion

- This meta-analysis provided evidence from the largest sample to date (N = 298) that ketamine reduces suicidal ideation partially independently of mood symptoms.

While the anti-suicidal effects of ketamine appear to be robust in the above studies, the possibility of rebound suicidal ideation remains in the weeks or months following exposure. Also, these studies only prove a reduction in suicidal ideation; reduction in suicidal behavior was not studied. Nevertheless, ketamine holds considerable promise as a potential rapid-acting agent in patients at risk of suicide.

Continue to: Strategies for augmentation or switching

Strategies for augmentation or switching