User login

Racial Disparities in the Diagnosis of Psoriasis

To the Editor:

Psoriasis affects 2% to 3% of the US population and is one of the more commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions.1-3 Experts agree that common cutaneous diseases such as psoriasis present differently in patients with skin of color (SOC) compared to non-SOC patients.3,4 Despite the prevalence of psoriasis, data on these morphologic differences are limited.3-5 We performed a retrospective chart review comparing characteristics of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients.

Through a search of electronic health records, we identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, diagnosis of psoriasis who were 18 years or older and were evaluated in the dermatology department between August 2015 and June 2020 at University Medical Center, an academic institution in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photographs and descriptions of lesions from these patients were reviewed. Patient data collected included age, sex, psoriasis classification, insurance status, self-identified race and ethnicity, location of lesion(s), biopsy, final diagnosis, and average number of visits or days required for accurate diagnosis. Self-identified SOC race and ethnicity categories included Black or African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and “other.”

All analyses were conducted using R-4.0.1 statistics software. Categorical variables were compared in SOC and non-SOC groups using Fisher exact tests. Continuous covariates were conducted using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In total, we reviewed 557 charts. Four patients who declined to identify their race or ethnicity were excluded, yielding 286 SOC and 267 non-SOC patients (N=553). A total of 276 patients (131 SOC; 145 non-SOC) with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis were excluded in the days to diagnosis analysis. Twenty patients (15, SOC; 5, non-SOC) were given a diagnosis of a disease other than psoriasis when evaluated in the dermatology department.

Distributions between racial groups differed for insurance status, sex, psoriasis classification, biopsy status, and days between first dermatology visit and diagnosis. Skin of color patients had significantly longer days between initial presentation to dermatology and final diagnosis vs non-SOC patients (180.11 and 60.27 days, respectively; P=.001). Skin of color patients had a higher rate of palmoplantar psoriasis and severe plaque psoriasis (ie, >10% body surface area involvement) at presentation.

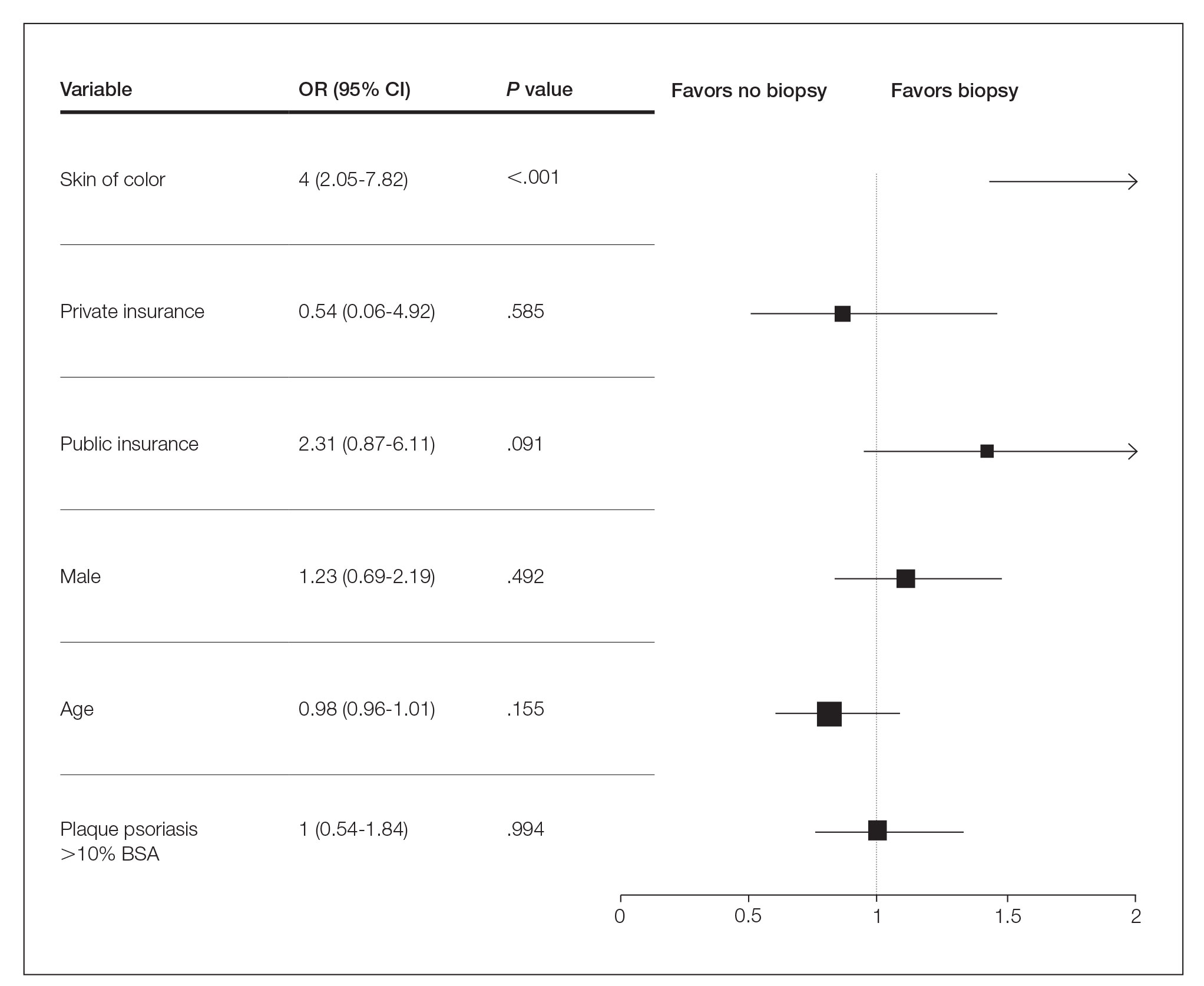

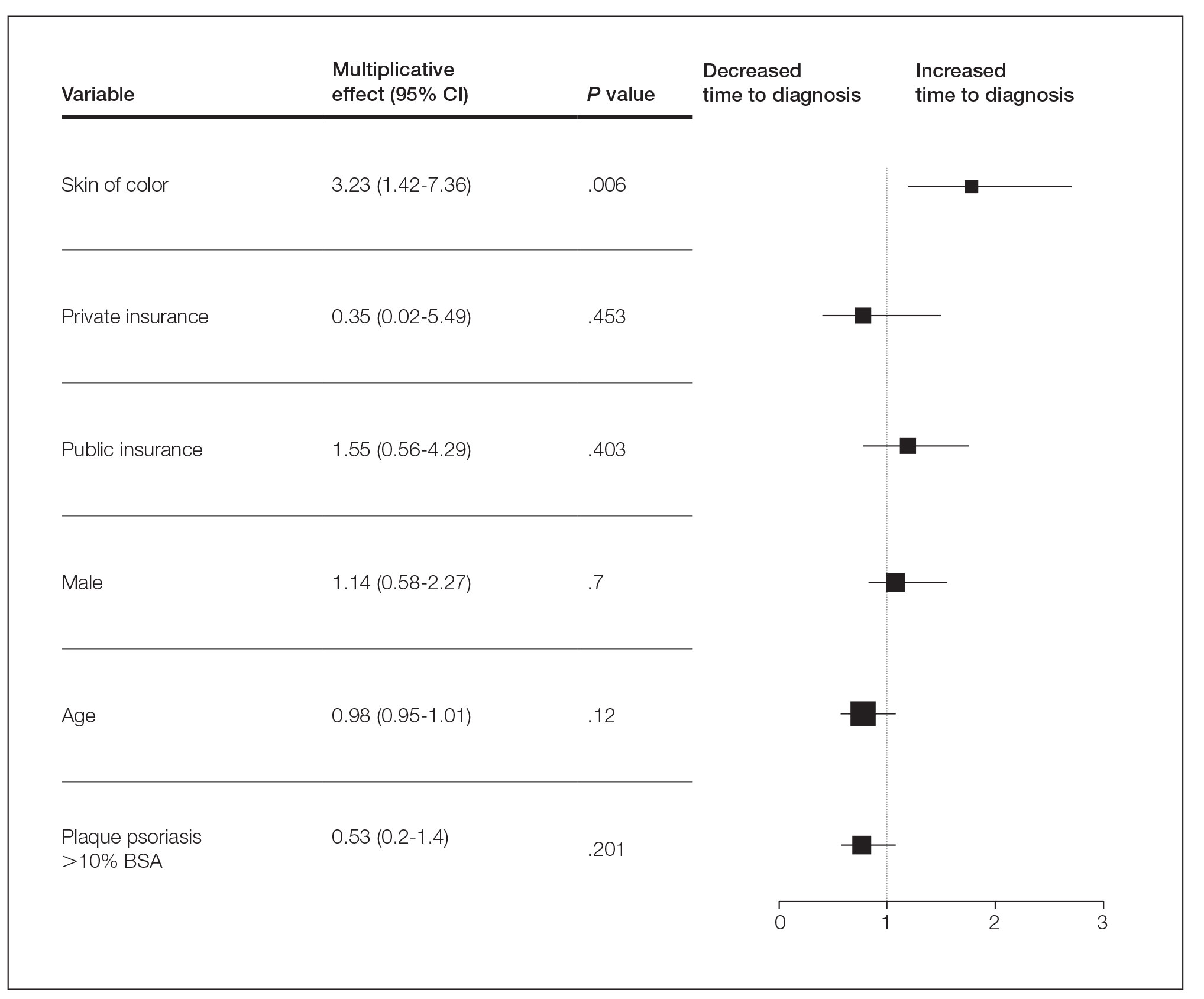

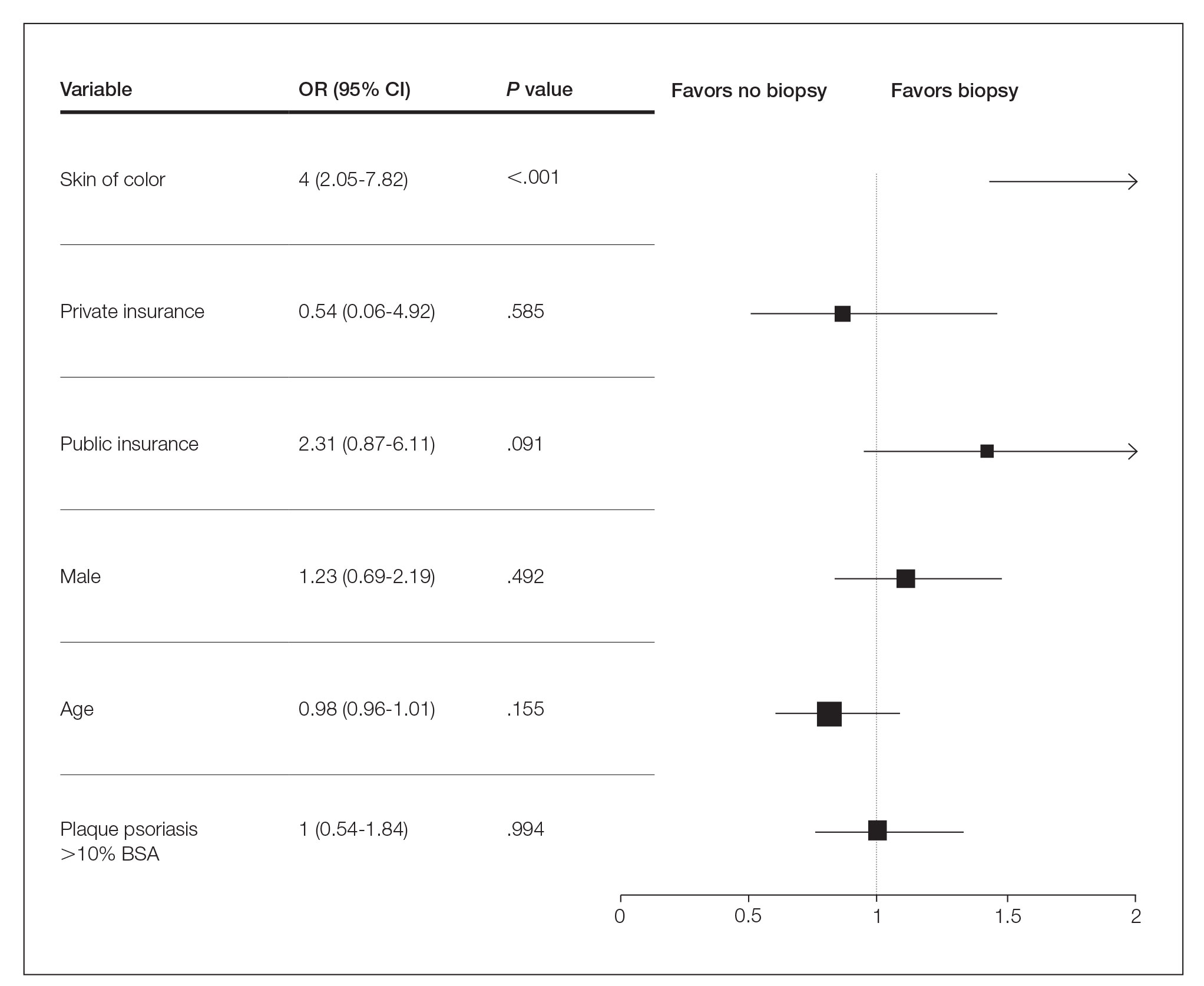

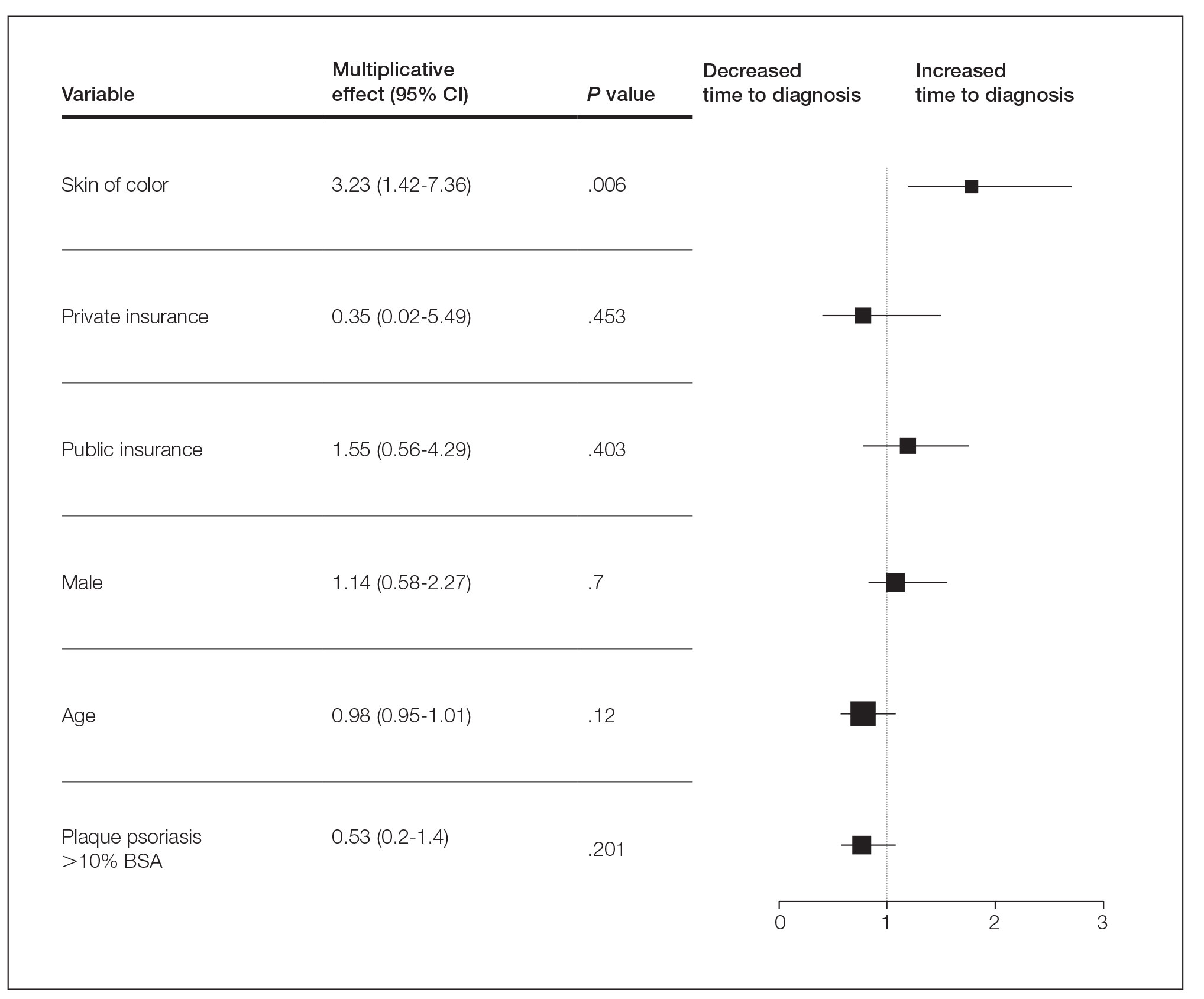

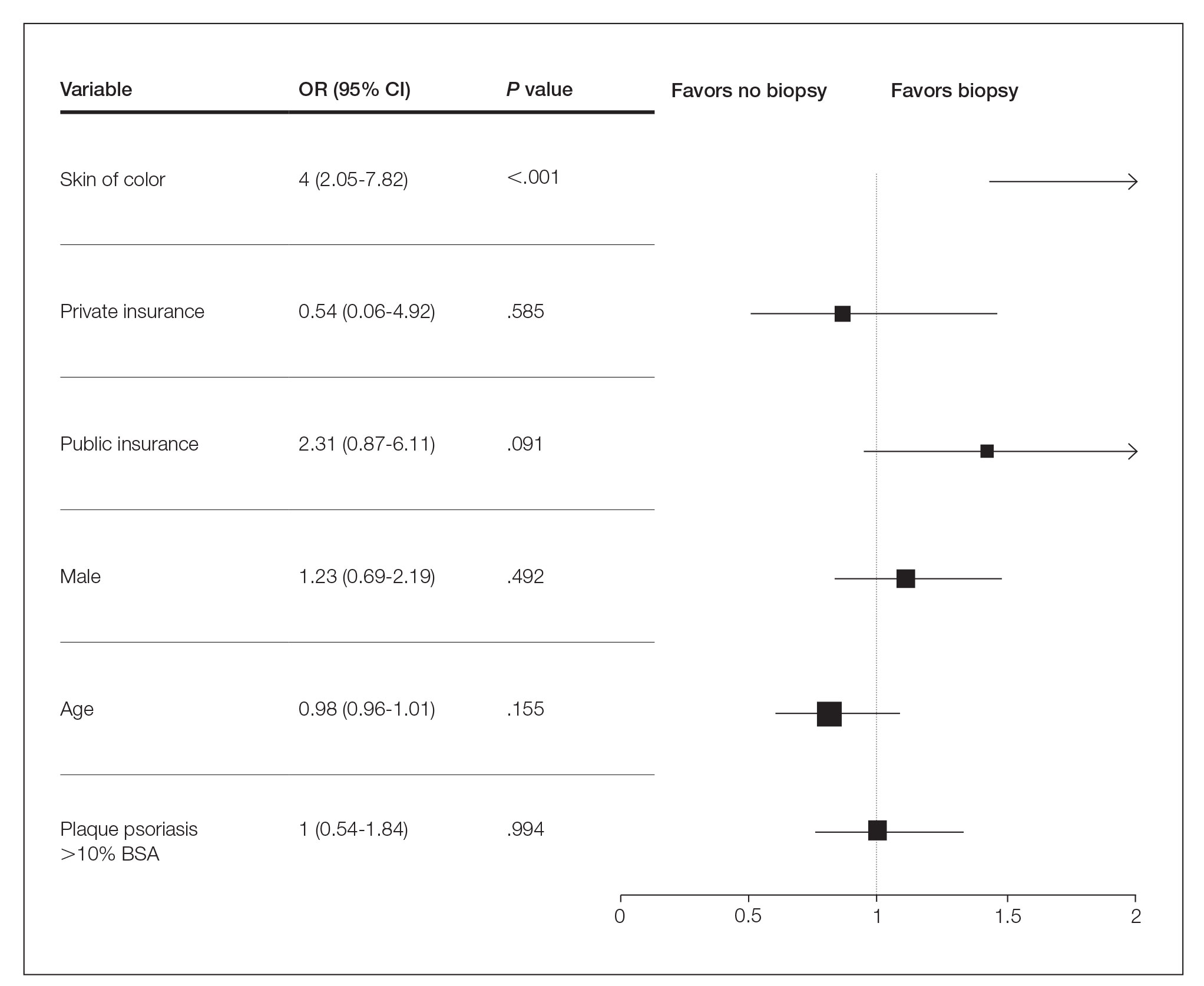

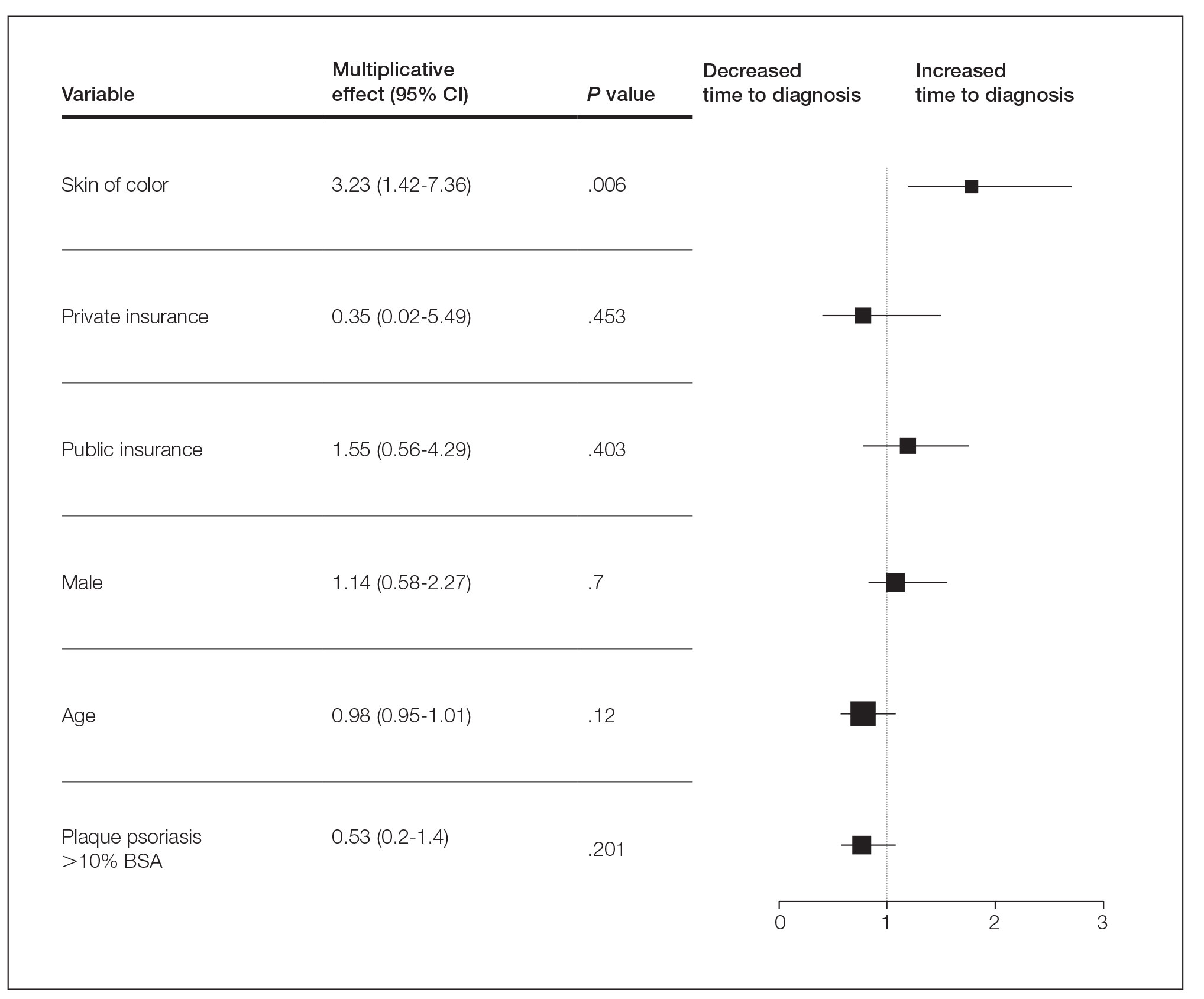

Several multivariable regression analyses were performed. Skin of color patients had significantly higher odds of biopsy compared to non-SOC patients (adjusted odds ratio [95% CI]=4 [2.05-7.82]; P<.001)(Figure 1). There were no significant predictors for severe plaque psoriasis involving more than 10% body surface area. Skin of color patients had a significantly longer time to diagnosis than non-SOC patients (P=.006)(Figure 2). On average, patients with SOC waited 3.23 times longer for a diagnosis than their non-SOC counterparts (95% CI, 1.42-7.36).

Our data reveal striking racial disparities in psoriasis care. Worse outcomes for patients with SOC compared to non-SOC patients may result from physicians’ inadequate familiarity with diverse presentations of psoriasis, including more frequent involvement of special body sites in SOC. Other likely contributing factors that we did not evaluate include socioeconomic barriers to health care, lack of physician diversity, missed appointments, and a paucity of literature on the topic of differentiating morphologies of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients. Our study did not examine the effects of sex, tobacco use, or prior or current therapy, and it excluded pediatric patients.

To improve dermatologic outcomes for our increasingly diverse patient population, more studies must be undertaken to elucidate and document disparities in care for SOC populations.

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.045

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7

To the Editor:

Psoriasis affects 2% to 3% of the US population and is one of the more commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions.1-3 Experts agree that common cutaneous diseases such as psoriasis present differently in patients with skin of color (SOC) compared to non-SOC patients.3,4 Despite the prevalence of psoriasis, data on these morphologic differences are limited.3-5 We performed a retrospective chart review comparing characteristics of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients.

Through a search of electronic health records, we identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, diagnosis of psoriasis who were 18 years or older and were evaluated in the dermatology department between August 2015 and June 2020 at University Medical Center, an academic institution in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photographs and descriptions of lesions from these patients were reviewed. Patient data collected included age, sex, psoriasis classification, insurance status, self-identified race and ethnicity, location of lesion(s), biopsy, final diagnosis, and average number of visits or days required for accurate diagnosis. Self-identified SOC race and ethnicity categories included Black or African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and “other.”

All analyses were conducted using R-4.0.1 statistics software. Categorical variables were compared in SOC and non-SOC groups using Fisher exact tests. Continuous covariates were conducted using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In total, we reviewed 557 charts. Four patients who declined to identify their race or ethnicity were excluded, yielding 286 SOC and 267 non-SOC patients (N=553). A total of 276 patients (131 SOC; 145 non-SOC) with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis were excluded in the days to diagnosis analysis. Twenty patients (15, SOC; 5, non-SOC) were given a diagnosis of a disease other than psoriasis when evaluated in the dermatology department.

Distributions between racial groups differed for insurance status, sex, psoriasis classification, biopsy status, and days between first dermatology visit and diagnosis. Skin of color patients had significantly longer days between initial presentation to dermatology and final diagnosis vs non-SOC patients (180.11 and 60.27 days, respectively; P=.001). Skin of color patients had a higher rate of palmoplantar psoriasis and severe plaque psoriasis (ie, >10% body surface area involvement) at presentation.

Several multivariable regression analyses were performed. Skin of color patients had significantly higher odds of biopsy compared to non-SOC patients (adjusted odds ratio [95% CI]=4 [2.05-7.82]; P<.001)(Figure 1). There were no significant predictors for severe plaque psoriasis involving more than 10% body surface area. Skin of color patients had a significantly longer time to diagnosis than non-SOC patients (P=.006)(Figure 2). On average, patients with SOC waited 3.23 times longer for a diagnosis than their non-SOC counterparts (95% CI, 1.42-7.36).

Our data reveal striking racial disparities in psoriasis care. Worse outcomes for patients with SOC compared to non-SOC patients may result from physicians’ inadequate familiarity with diverse presentations of psoriasis, including more frequent involvement of special body sites in SOC. Other likely contributing factors that we did not evaluate include socioeconomic barriers to health care, lack of physician diversity, missed appointments, and a paucity of literature on the topic of differentiating morphologies of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients. Our study did not examine the effects of sex, tobacco use, or prior or current therapy, and it excluded pediatric patients.

To improve dermatologic outcomes for our increasingly diverse patient population, more studies must be undertaken to elucidate and document disparities in care for SOC populations.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis affects 2% to 3% of the US population and is one of the more commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions.1-3 Experts agree that common cutaneous diseases such as psoriasis present differently in patients with skin of color (SOC) compared to non-SOC patients.3,4 Despite the prevalence of psoriasis, data on these morphologic differences are limited.3-5 We performed a retrospective chart review comparing characteristics of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients.

Through a search of electronic health records, we identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, diagnosis of psoriasis who were 18 years or older and were evaluated in the dermatology department between August 2015 and June 2020 at University Medical Center, an academic institution in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photographs and descriptions of lesions from these patients were reviewed. Patient data collected included age, sex, psoriasis classification, insurance status, self-identified race and ethnicity, location of lesion(s), biopsy, final diagnosis, and average number of visits or days required for accurate diagnosis. Self-identified SOC race and ethnicity categories included Black or African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and “other.”

All analyses were conducted using R-4.0.1 statistics software. Categorical variables were compared in SOC and non-SOC groups using Fisher exact tests. Continuous covariates were conducted using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In total, we reviewed 557 charts. Four patients who declined to identify their race or ethnicity were excluded, yielding 286 SOC and 267 non-SOC patients (N=553). A total of 276 patients (131 SOC; 145 non-SOC) with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis were excluded in the days to diagnosis analysis. Twenty patients (15, SOC; 5, non-SOC) were given a diagnosis of a disease other than psoriasis when evaluated in the dermatology department.

Distributions between racial groups differed for insurance status, sex, psoriasis classification, biopsy status, and days between first dermatology visit and diagnosis. Skin of color patients had significantly longer days between initial presentation to dermatology and final diagnosis vs non-SOC patients (180.11 and 60.27 days, respectively; P=.001). Skin of color patients had a higher rate of palmoplantar psoriasis and severe plaque psoriasis (ie, >10% body surface area involvement) at presentation.

Several multivariable regression analyses were performed. Skin of color patients had significantly higher odds of biopsy compared to non-SOC patients (adjusted odds ratio [95% CI]=4 [2.05-7.82]; P<.001)(Figure 1). There were no significant predictors for severe plaque psoriasis involving more than 10% body surface area. Skin of color patients had a significantly longer time to diagnosis than non-SOC patients (P=.006)(Figure 2). On average, patients with SOC waited 3.23 times longer for a diagnosis than their non-SOC counterparts (95% CI, 1.42-7.36).

Our data reveal striking racial disparities in psoriasis care. Worse outcomes for patients with SOC compared to non-SOC patients may result from physicians’ inadequate familiarity with diverse presentations of psoriasis, including more frequent involvement of special body sites in SOC. Other likely contributing factors that we did not evaluate include socioeconomic barriers to health care, lack of physician diversity, missed appointments, and a paucity of literature on the topic of differentiating morphologies of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients. Our study did not examine the effects of sex, tobacco use, or prior or current therapy, and it excluded pediatric patients.

To improve dermatologic outcomes for our increasingly diverse patient population, more studies must be undertaken to elucidate and document disparities in care for SOC populations.

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.045

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.045

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7

Practice Points

- Skin of color (SOC) patients can wait 3 times longer to receive a diagnosis of psoriasis than non-SOC patients.

- Patients with SOC more often present with severe forms of psoriasis and are more likely to have palmoplantar psoriasis.

- Skin of color patients can be 4 times as likely to require a biopsy to confirm psoriasis diagnosis compared to non-SOC patients.

Funding of cosmetic clinical trials linked to racial/ethnic disparity

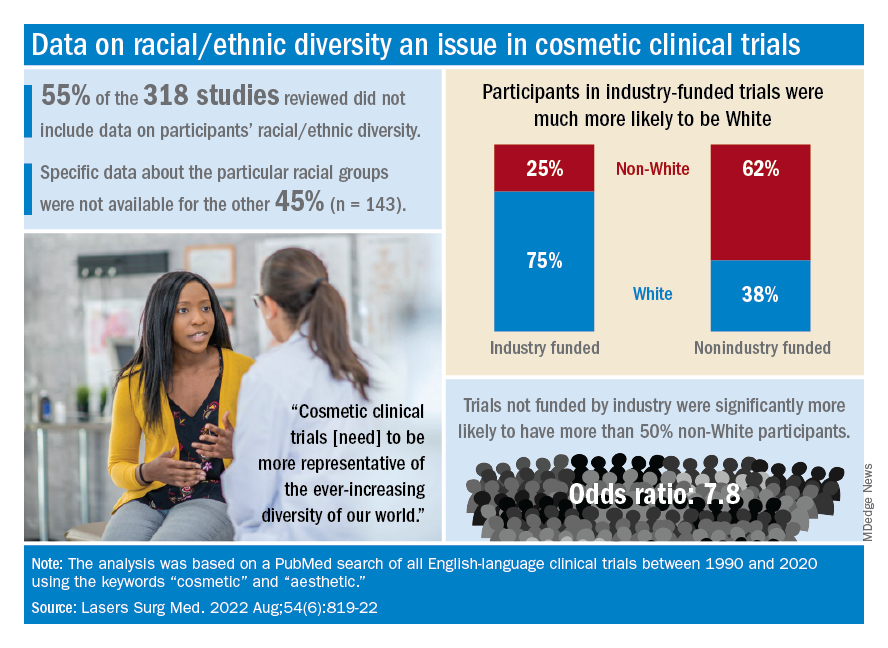

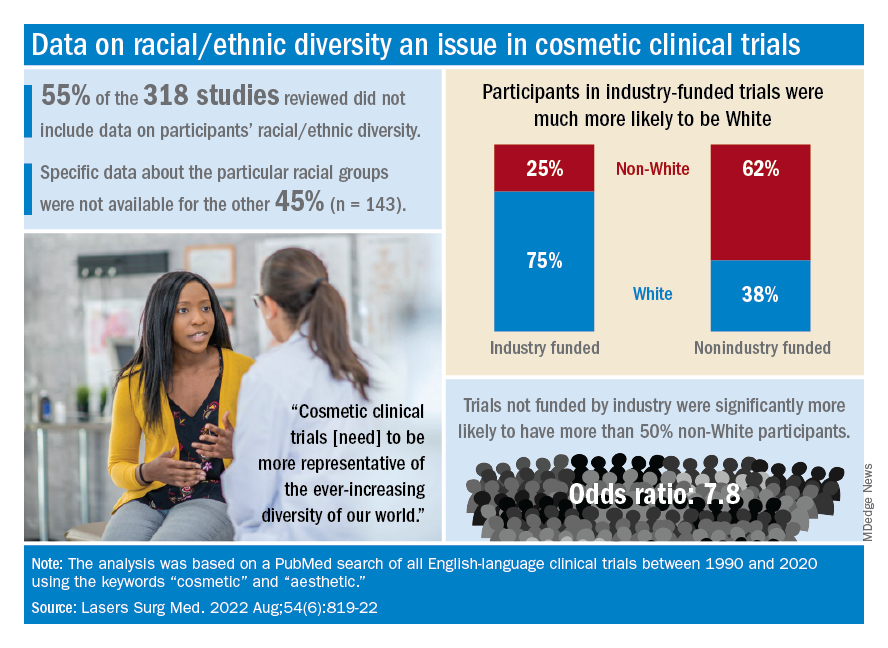

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

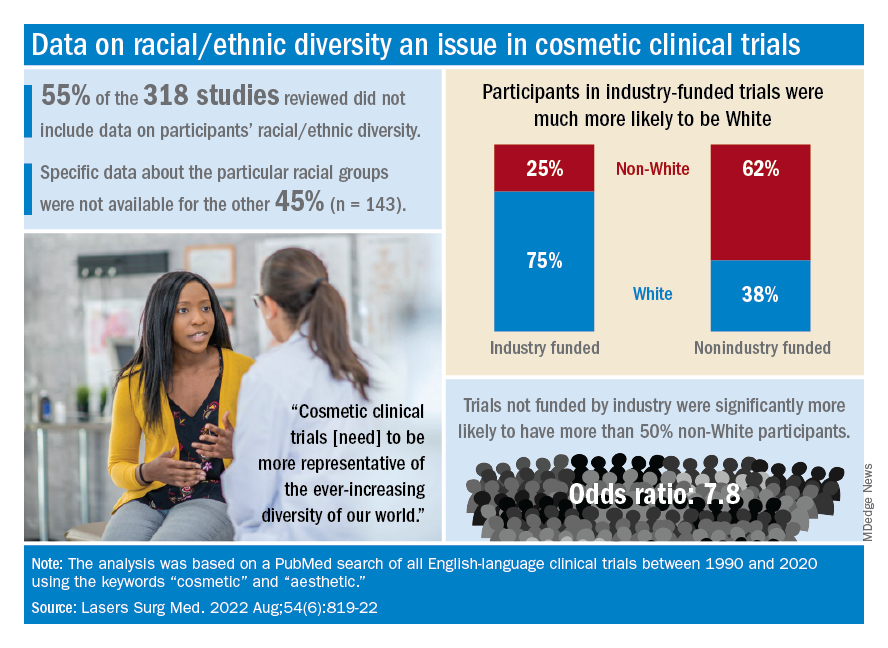

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM LASERS IN SURGERY AND MEDICINE

Differences in Underrepresented in Medicine Applicant Backgrounds and Outcomes in the 2020-2021 Dermatology Residency Match

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

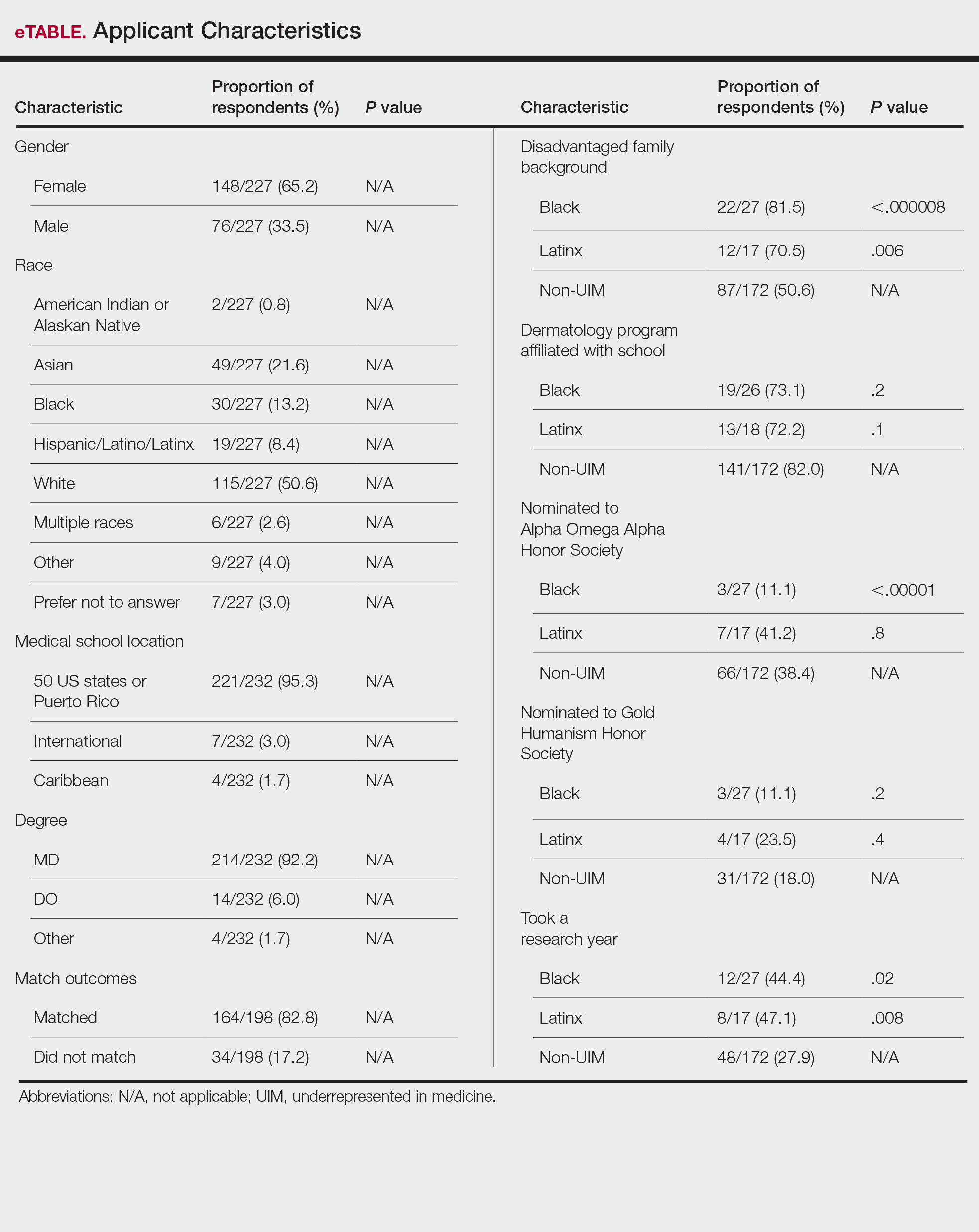

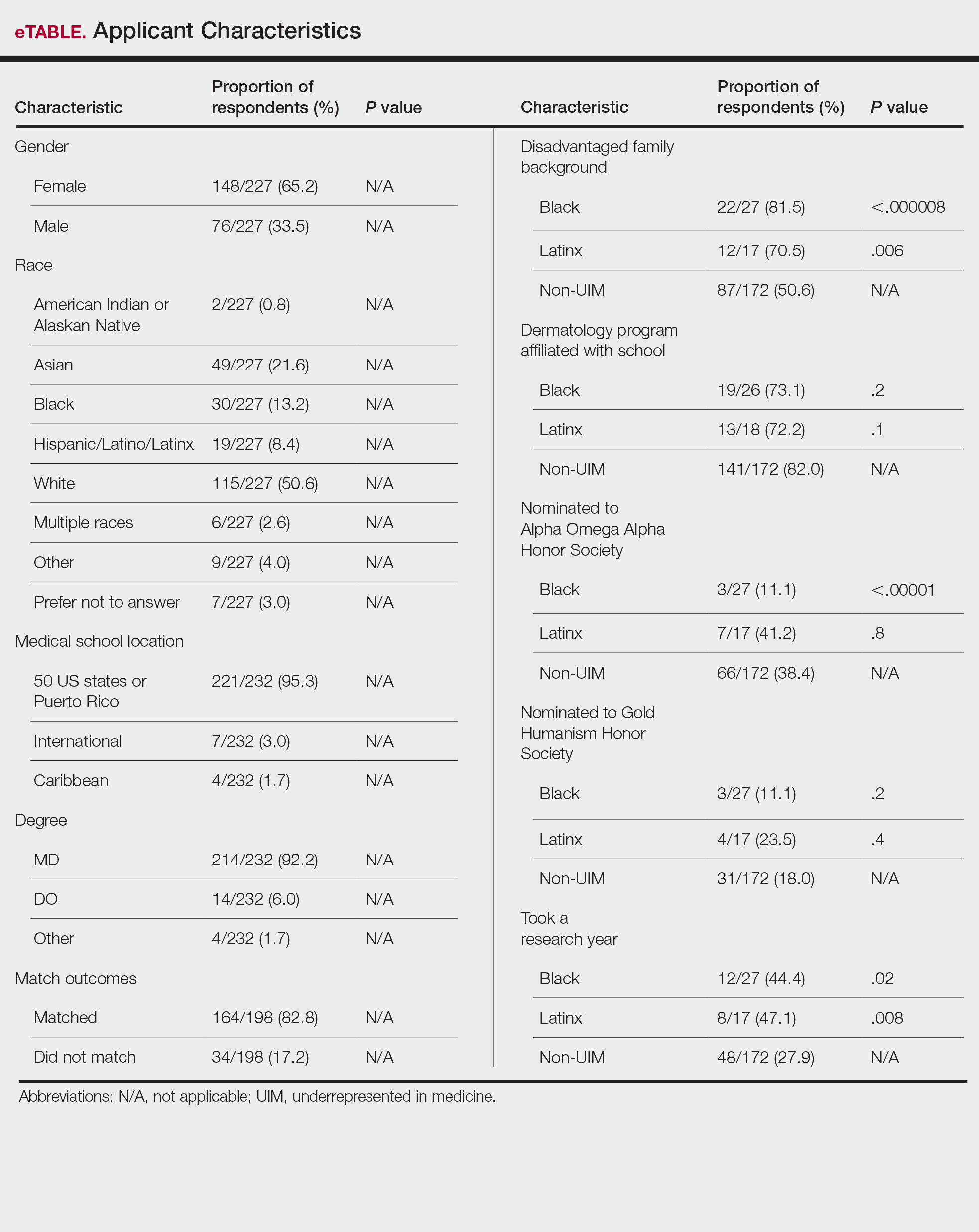

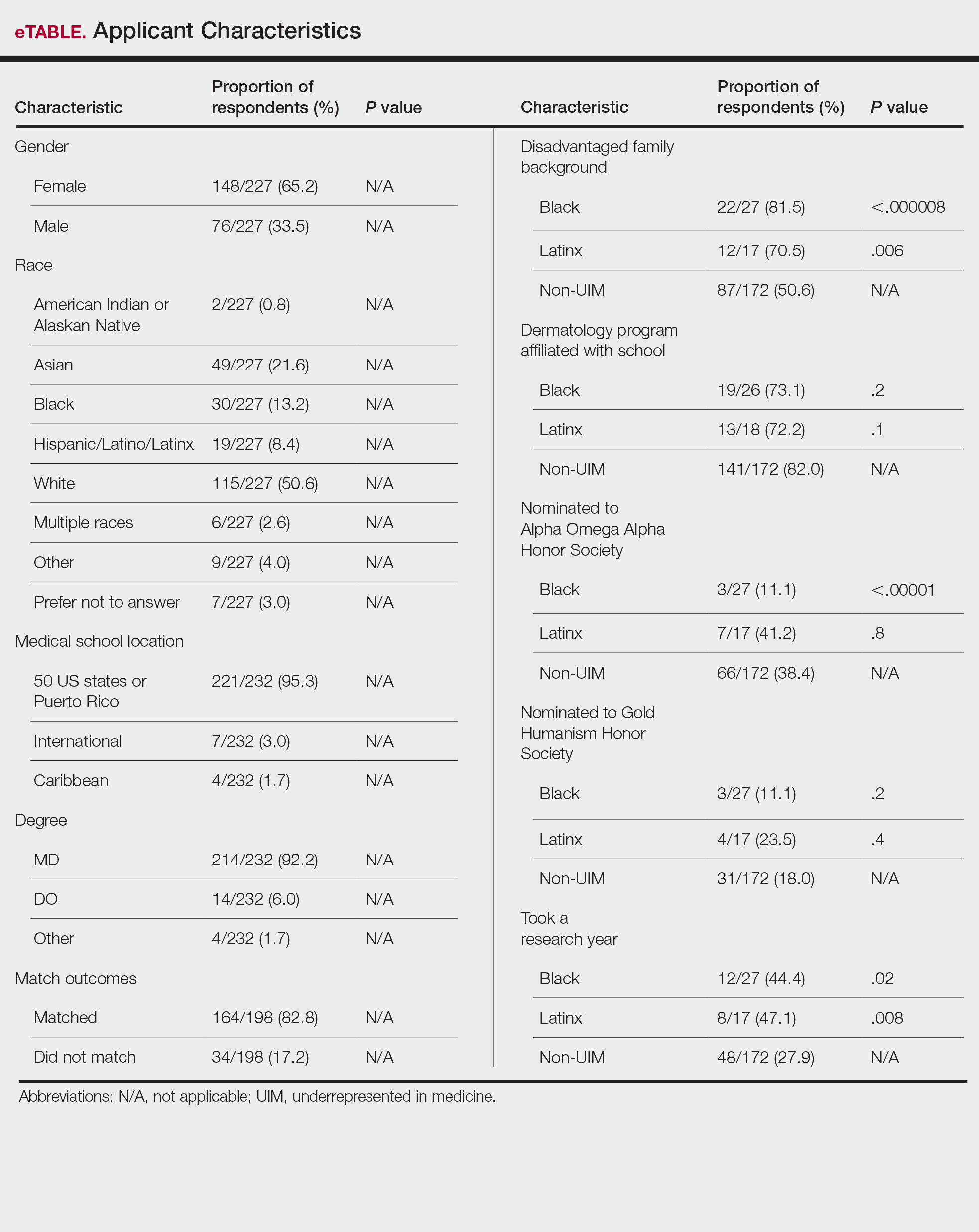

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

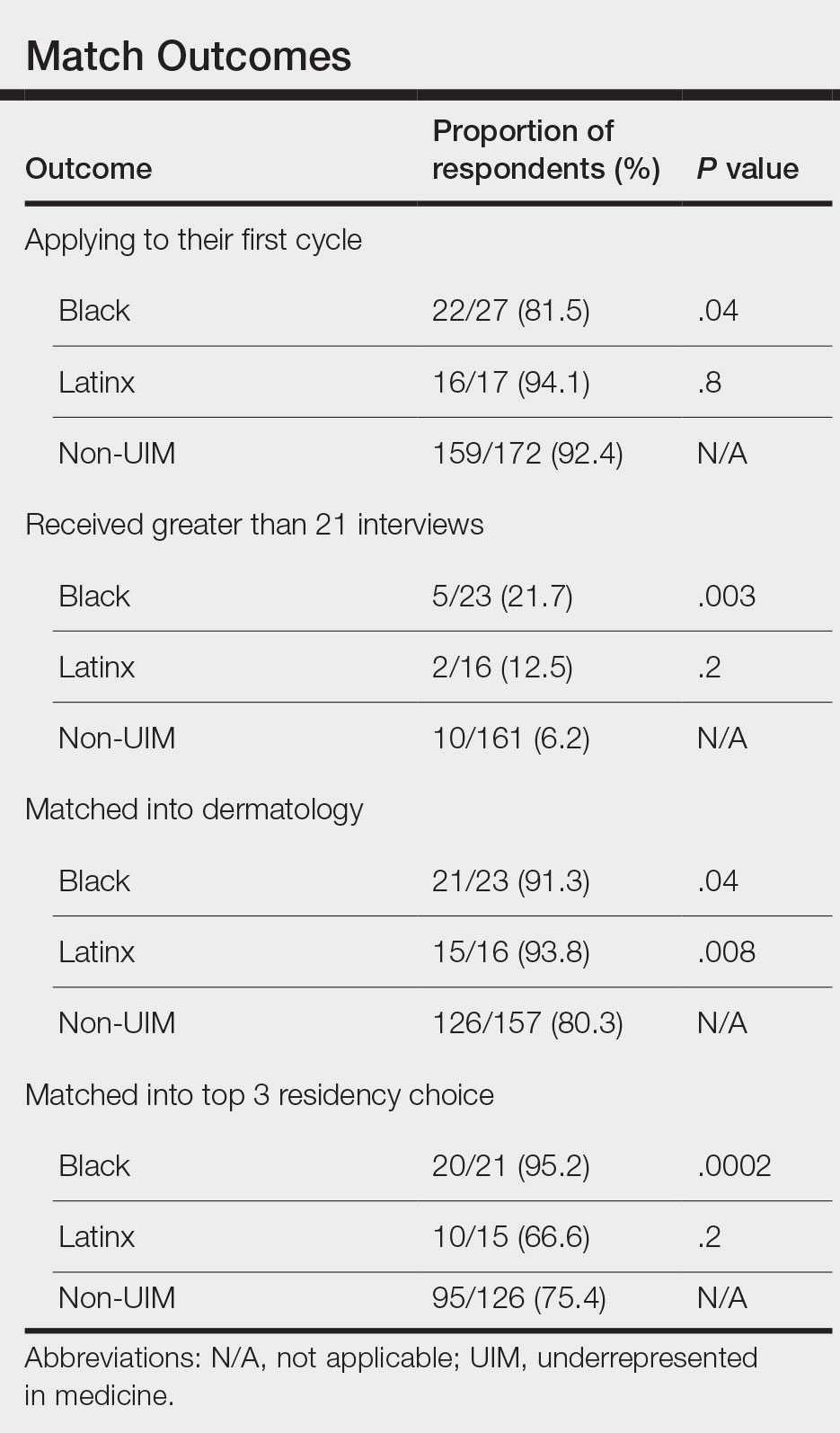

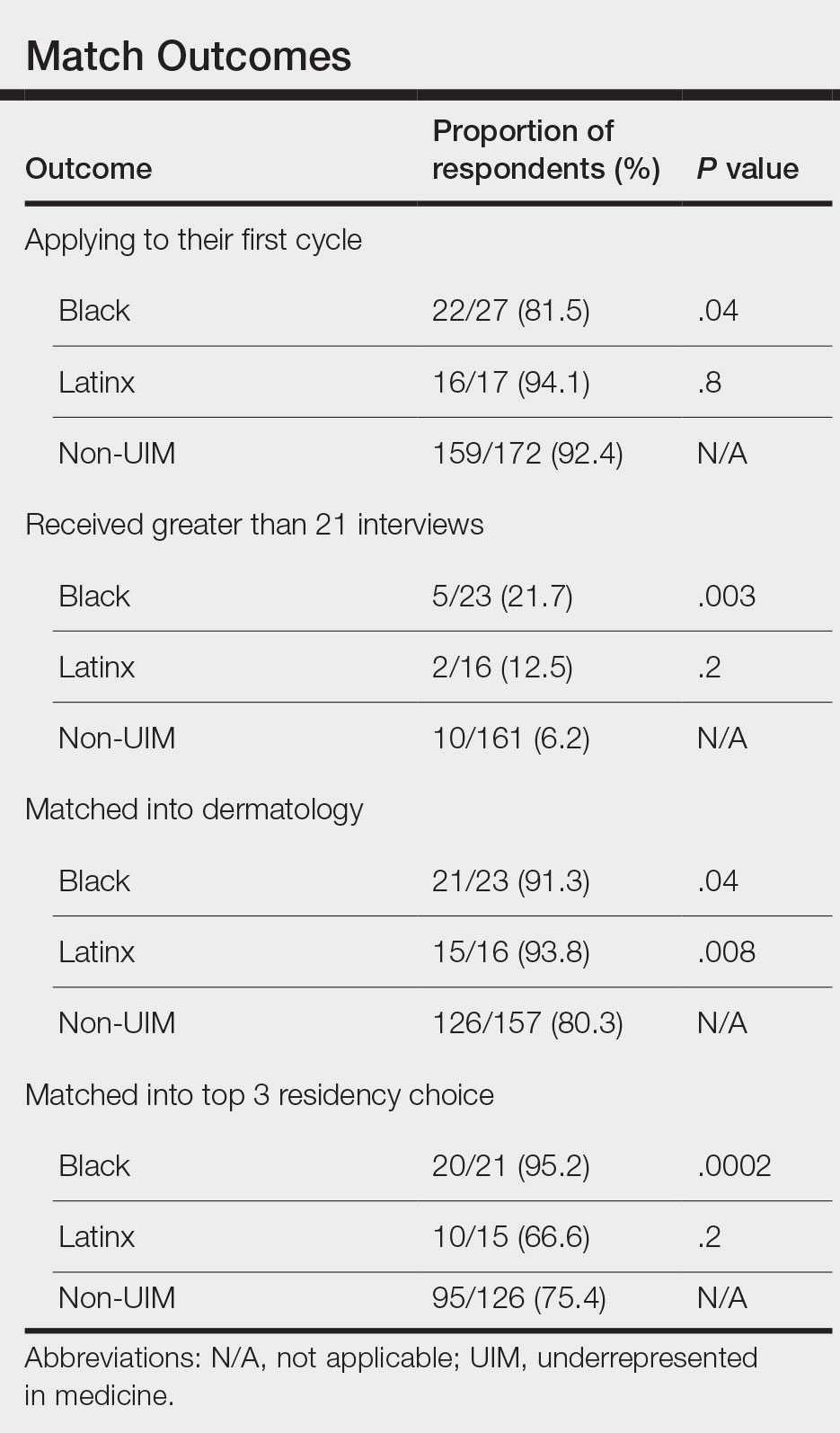

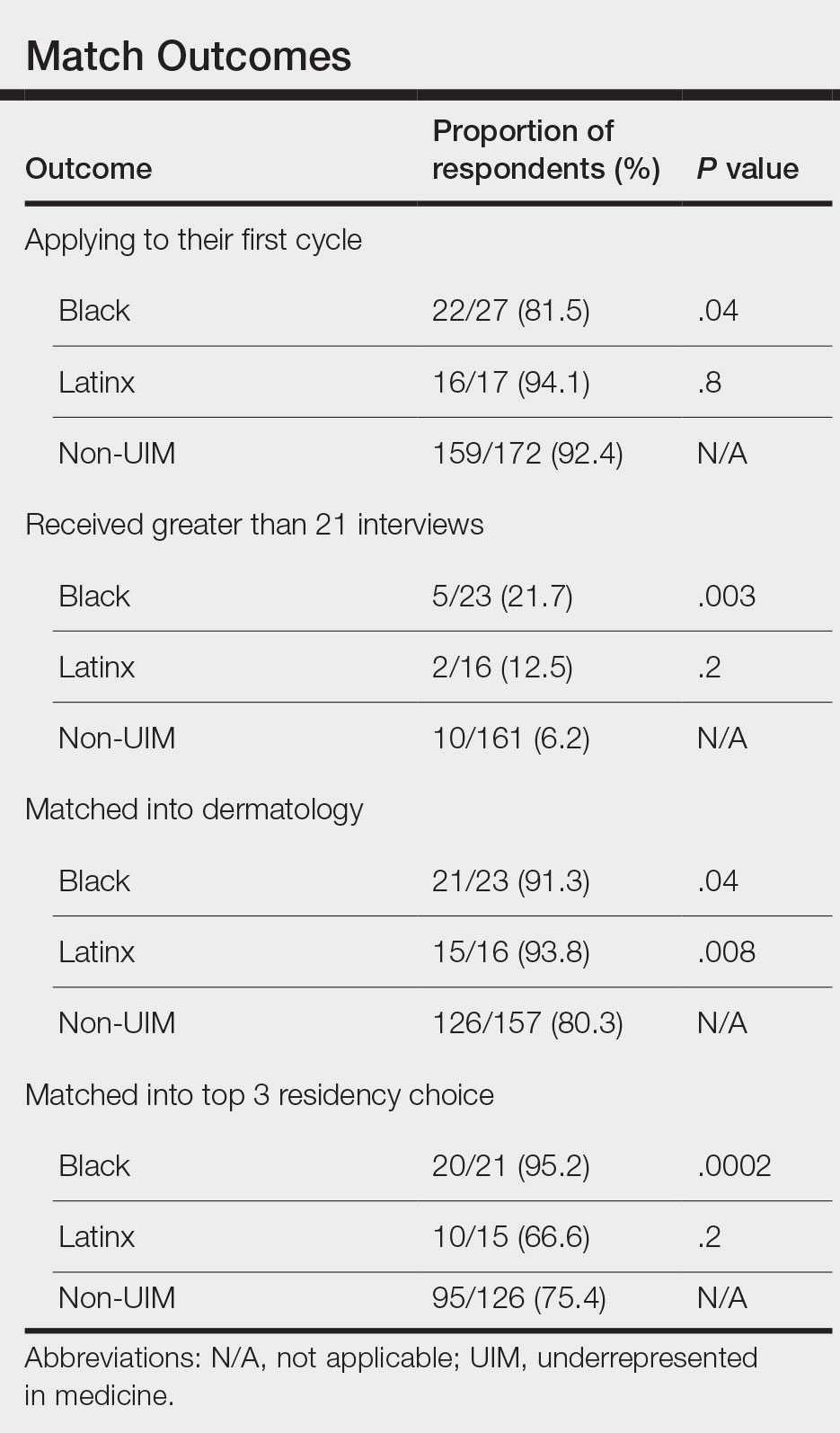

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

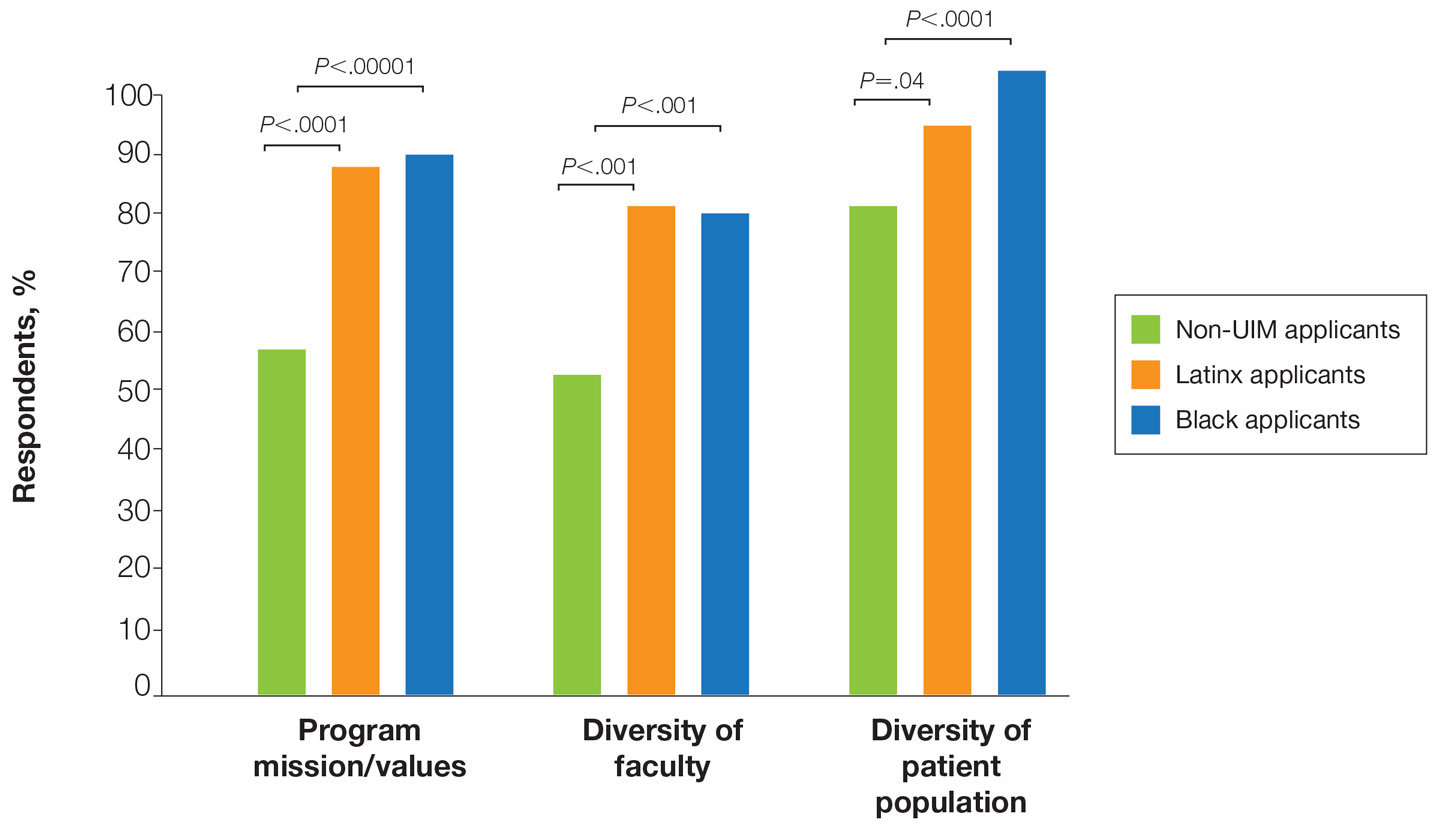

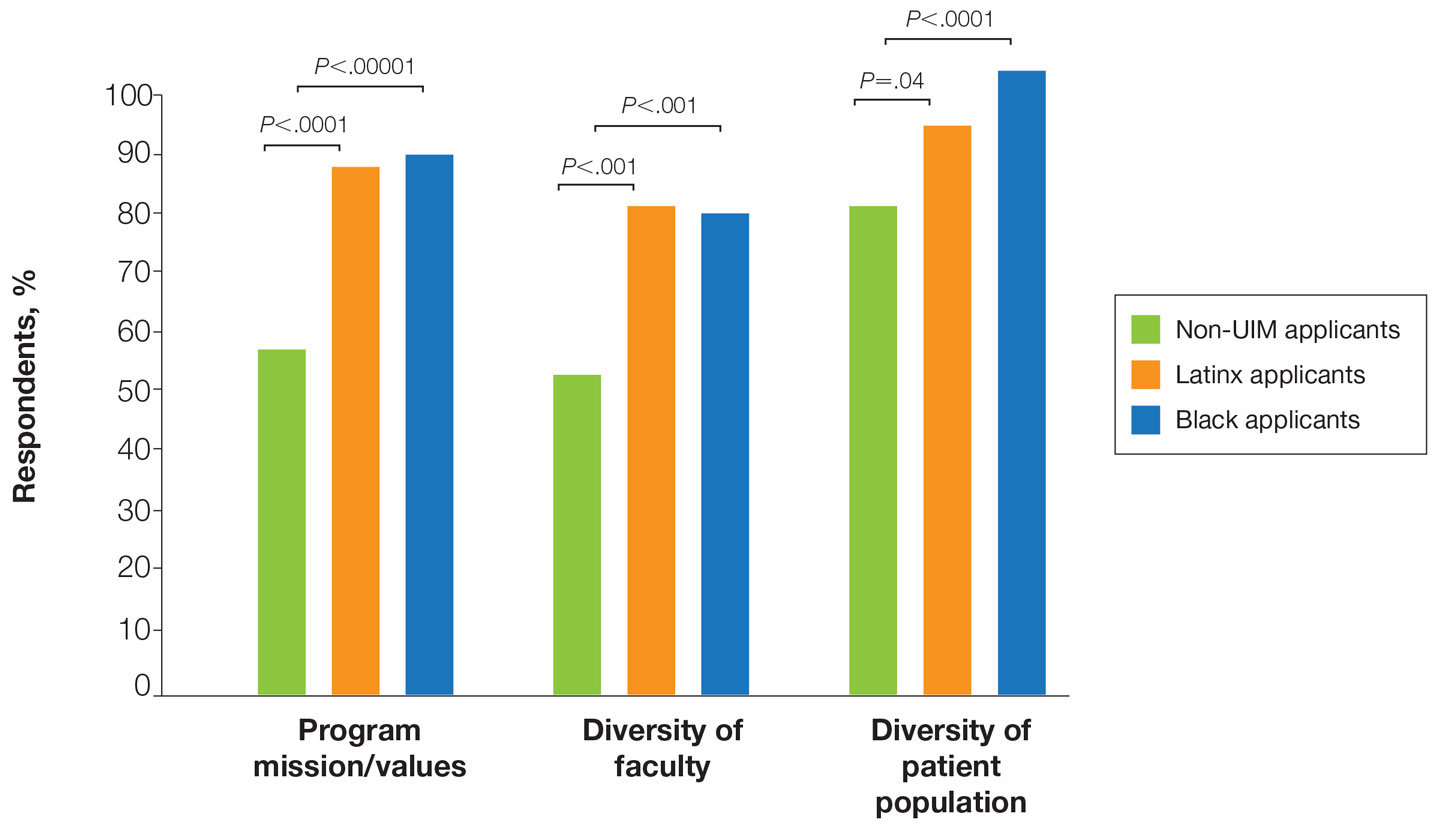

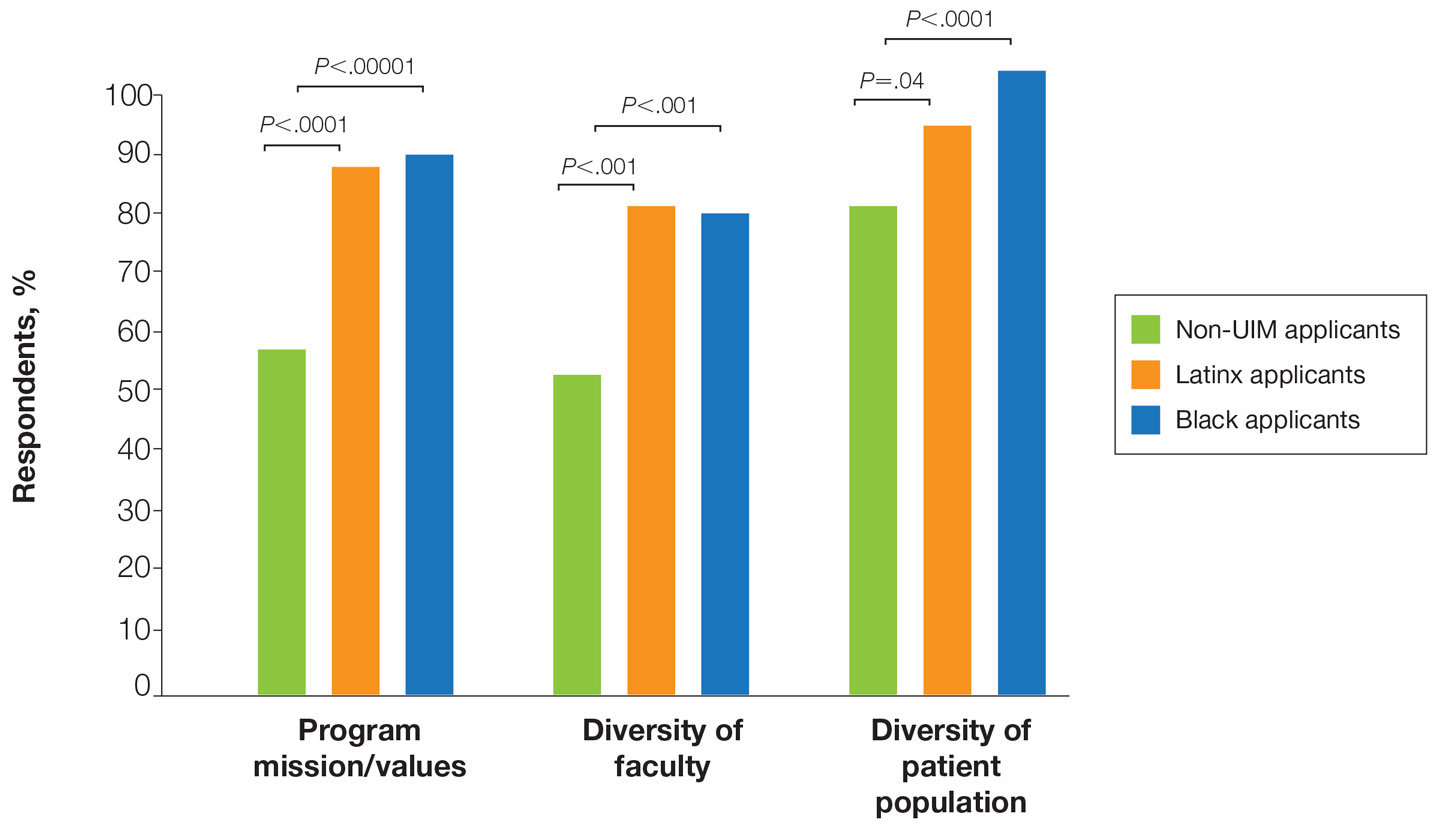

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Practice Points

- Underrepresented in medicine (UIM) dermatology residency applicants (Black and Latinx) are more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds and to have financial concerns about the residency application process.

- When choosing a dermatology residency program, diversity of patients and faculty are more important to UIM dermatology residency applicants than to their non-UIM counterparts.

- Increased awareness of and focus on a holistic review process by dermatology residency programs may contribute to higher rates of matching among Black applicants in our study.

Pigmented Papules on the Face, Neck, and Chest

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

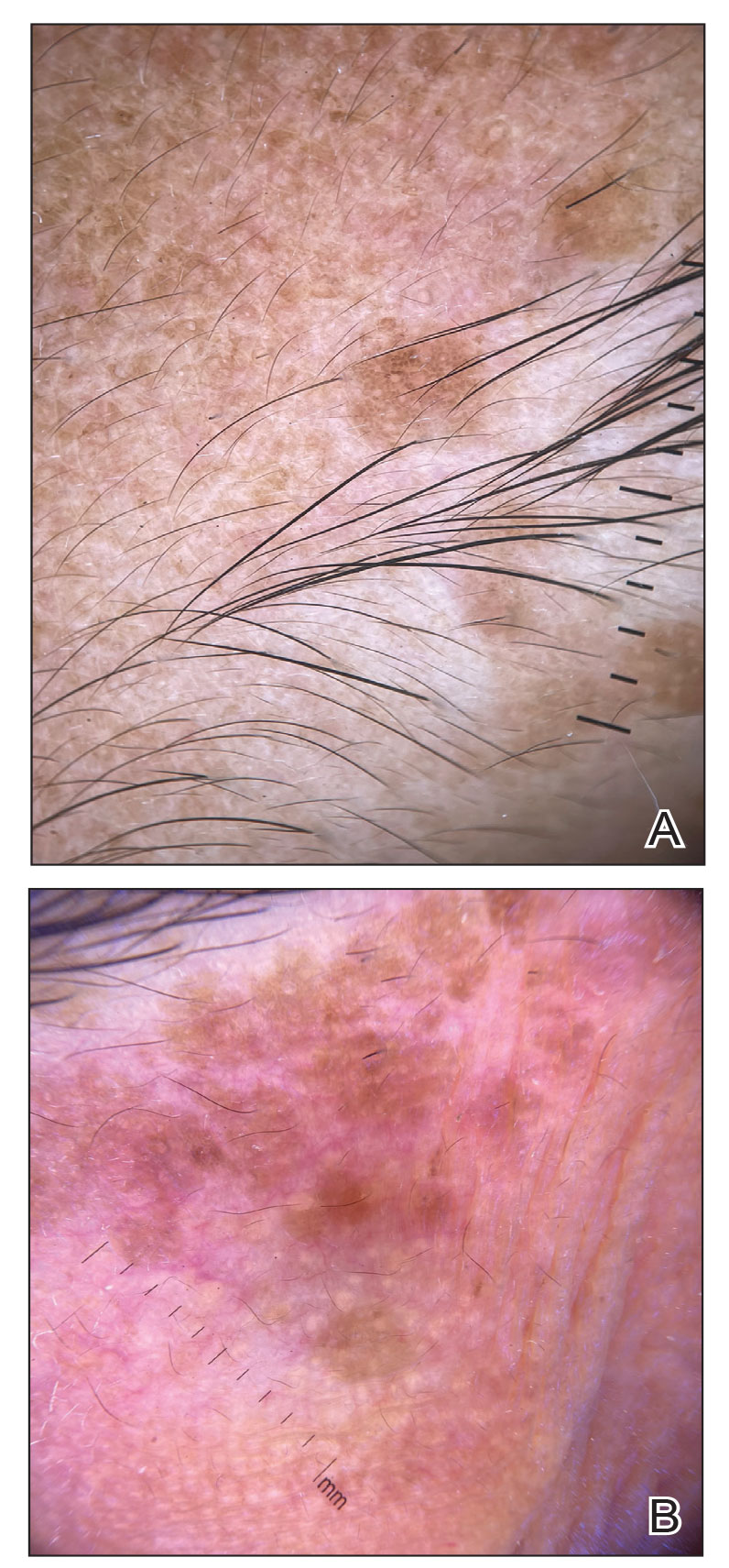

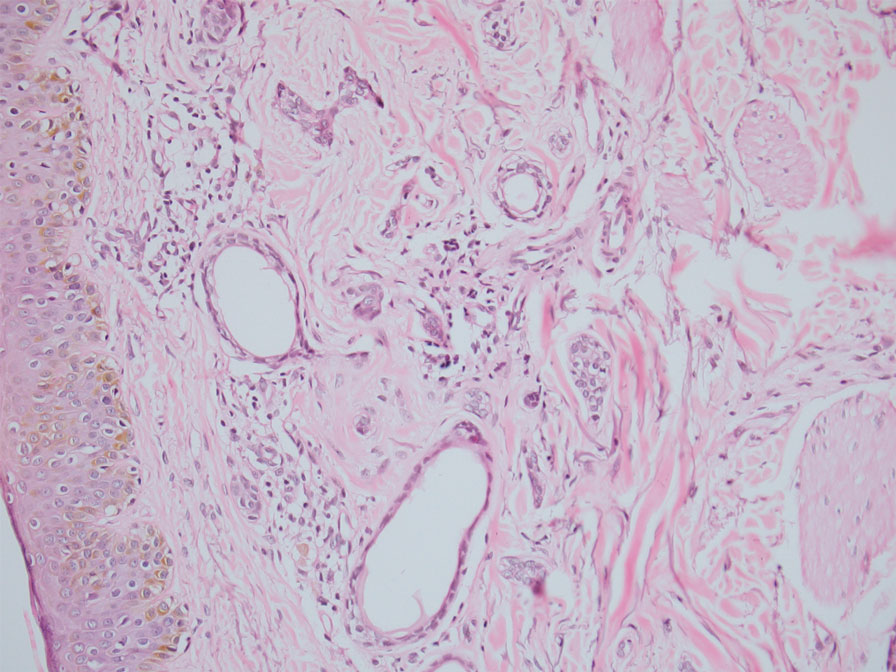

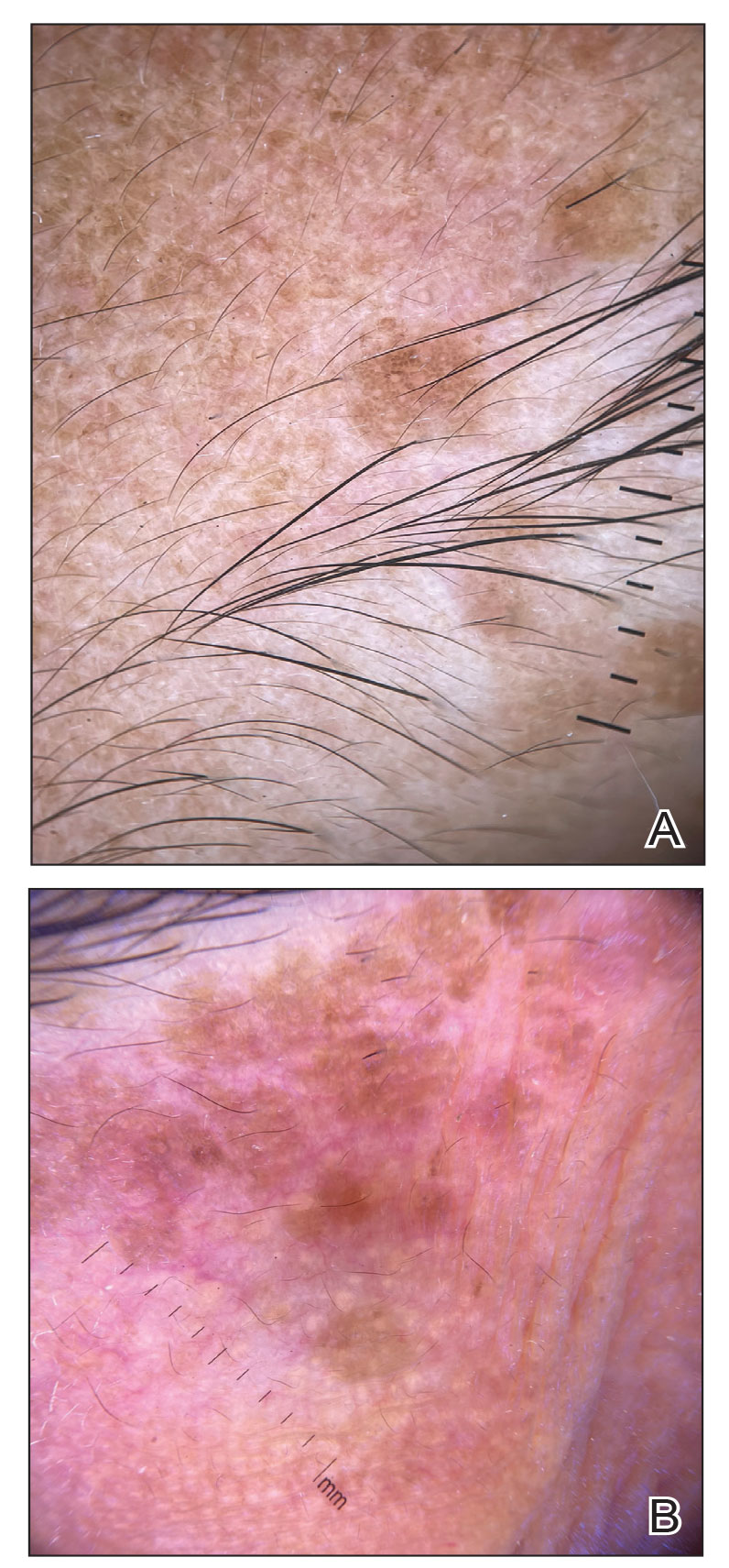

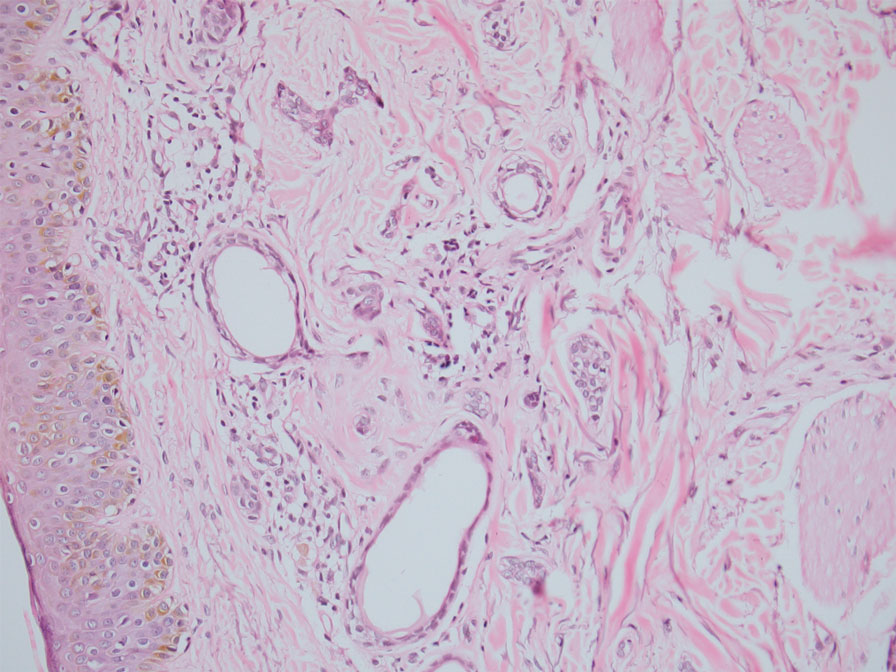

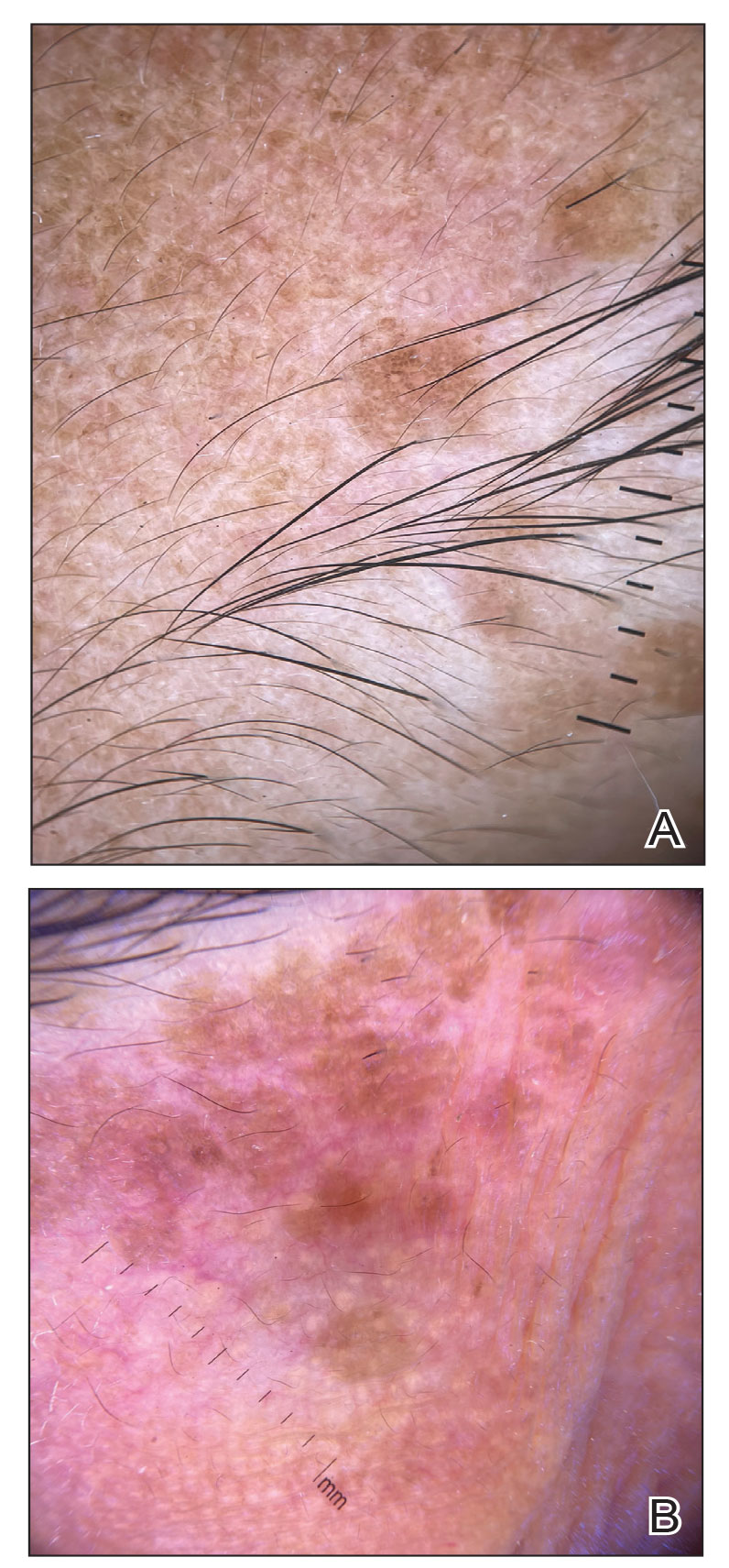

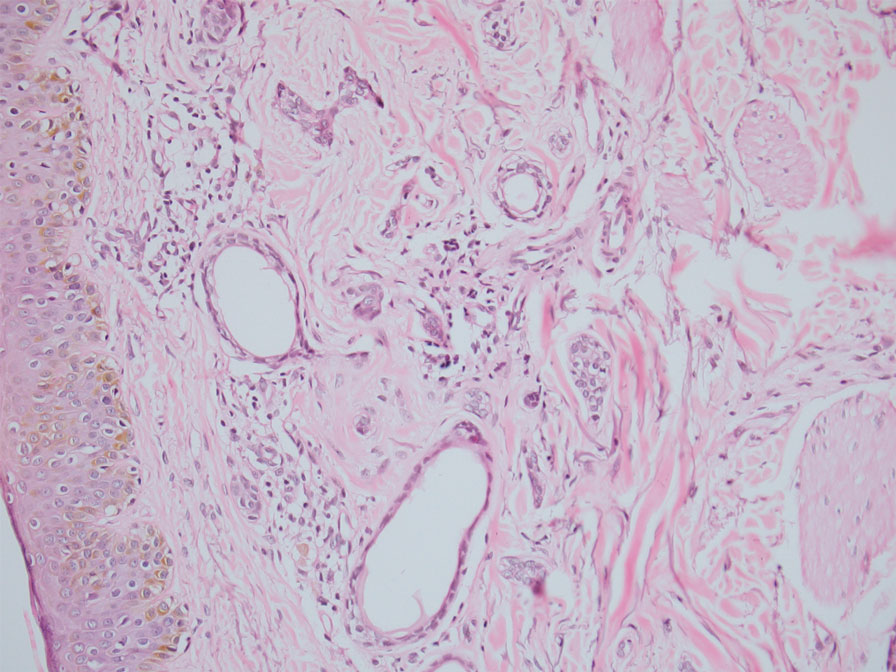

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234.e9-1240.e9.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Singh S, Tewari R, Gupta S. An unusual case of generalised eruptive syringoma in an adult male. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:389-391.

- Hayashi Y, Tanaka M, Nakajima S, et al. Unilateral linear syringoma in a Japanese female: dermoscopic differentiation from lichen lanus linearis. Dermatol Rep. 2011;3:E42.

- Sakiyama M, Maeda M, Fujimoto N, et al. Eruptive syringoma localized in intertriginous areas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:72-73.

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH Jr. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Hasson A, Farias MM, Nicklas C, et al. Periorbital syringoma treated with radiofrequency and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser in 5 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:879-880.

- Seo HM, Choi JY, Min J, et al. Carbon dioxide laser combined with botulinum toxin A for patients with periorbital syringomas [published online March 31, 2016]. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:149-153.

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234.e9-1240.e9.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Singh S, Tewari R, Gupta S. An unusual case of generalised eruptive syringoma in an adult male. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:389-391.

- Hayashi Y, Tanaka M, Nakajima S, et al. Unilateral linear syringoma in a Japanese female: dermoscopic differentiation from lichen lanus linearis. Dermatol Rep. 2011;3:E42.

- Sakiyama M, Maeda M, Fujimoto N, et al. Eruptive syringoma localized in intertriginous areas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:72-73.

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH Jr. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Hasson A, Farias MM, Nicklas C, et al. Periorbital syringoma treated with radiofrequency and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser in 5 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:879-880.

- Seo HM, Choi JY, Min J, et al. Carbon dioxide laser combined with botulinum toxin A for patients with periorbital syringomas [published online March 31, 2016]. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:149-153.