User login

Helping Patients With Intellectual Disabilities Make Informed Decisions

BOSTON — Primary care clinicians caring for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities often recommend guardianship, a responsibility with life-altering implications.

But only approximately 30% of primary care residency programs in the United States provide training on how to assess the ability of patients with disabilities to make decisions for themselves, and much of this training is optional, according to a recent study cited during a workshop at the 2024 annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

Assessing the capacity of patients with disabilities involves navigating a maze of legal, ethical, and clinical considerations, according to Mary Thomas, MD, MPH, a clinical fellow in geriatrics at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who co-moderated the workshop.

Guardianship, while sometimes necessary, can be overly restrictive and diminish patient autonomy, she said. The legal process — ultimately decided through the courts — gives a guardian permission to manage medical care and make decisions for someone who cannot make or communicate those decisions themselves.

Clinicians can assess patients through an evaluation of functional capacity, which allows them to observe a patient’s demeanor and administer a cognition test. Alternatives such as supported decision-making may be less restrictive and can better serve patients, she said. Supported decision-making allows for a person with disabilities to receive assistance from a supporter who can help a patient process medical conditions and treatment needs. The supporter helps empower capable patients to decide on their own.

Some states have introduced legislation that would legally recognize supported decision-making as a less restrictive alternative to guardianship or conservatorship, in which a court-appointed individual manages all aspects of a person’s life.

Sara Mixter, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and a co-moderator of the workshop, called the use of inclusive language in patient communication the “first step toward fostering an environment where patients feel respected and understood.”

Inclusive conversations can include person-first language and using words such as “caregiver” rather than “caretaker.”

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Mixter also called for the directors of residency programs to provide more training on disabilities. They cited a 2023 survey of directors, many of whom said that educational boards do not require training in disability-specific care and that experts in the care of people with disabilities are few and far between.

“Education and awareness are key to overcoming the challenges we face,” Dr. Thomas said. “Improving our training programs means we can ensure that all patients receive the care and respect they deserve.”

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Mixter report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON — Primary care clinicians caring for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities often recommend guardianship, a responsibility with life-altering implications.

But only approximately 30% of primary care residency programs in the United States provide training on how to assess the ability of patients with disabilities to make decisions for themselves, and much of this training is optional, according to a recent study cited during a workshop at the 2024 annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

Assessing the capacity of patients with disabilities involves navigating a maze of legal, ethical, and clinical considerations, according to Mary Thomas, MD, MPH, a clinical fellow in geriatrics at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who co-moderated the workshop.

Guardianship, while sometimes necessary, can be overly restrictive and diminish patient autonomy, she said. The legal process — ultimately decided through the courts — gives a guardian permission to manage medical care and make decisions for someone who cannot make or communicate those decisions themselves.

Clinicians can assess patients through an evaluation of functional capacity, which allows them to observe a patient’s demeanor and administer a cognition test. Alternatives such as supported decision-making may be less restrictive and can better serve patients, she said. Supported decision-making allows for a person with disabilities to receive assistance from a supporter who can help a patient process medical conditions and treatment needs. The supporter helps empower capable patients to decide on their own.

Some states have introduced legislation that would legally recognize supported decision-making as a less restrictive alternative to guardianship or conservatorship, in which a court-appointed individual manages all aspects of a person’s life.

Sara Mixter, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and a co-moderator of the workshop, called the use of inclusive language in patient communication the “first step toward fostering an environment where patients feel respected and understood.”

Inclusive conversations can include person-first language and using words such as “caregiver” rather than “caretaker.”

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Mixter also called for the directors of residency programs to provide more training on disabilities. They cited a 2023 survey of directors, many of whom said that educational boards do not require training in disability-specific care and that experts in the care of people with disabilities are few and far between.

“Education and awareness are key to overcoming the challenges we face,” Dr. Thomas said. “Improving our training programs means we can ensure that all patients receive the care and respect they deserve.”

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Mixter report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON — Primary care clinicians caring for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities often recommend guardianship, a responsibility with life-altering implications.

But only approximately 30% of primary care residency programs in the United States provide training on how to assess the ability of patients with disabilities to make decisions for themselves, and much of this training is optional, according to a recent study cited during a workshop at the 2024 annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

Assessing the capacity of patients with disabilities involves navigating a maze of legal, ethical, and clinical considerations, according to Mary Thomas, MD, MPH, a clinical fellow in geriatrics at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who co-moderated the workshop.

Guardianship, while sometimes necessary, can be overly restrictive and diminish patient autonomy, she said. The legal process — ultimately decided through the courts — gives a guardian permission to manage medical care and make decisions for someone who cannot make or communicate those decisions themselves.

Clinicians can assess patients through an evaluation of functional capacity, which allows them to observe a patient’s demeanor and administer a cognition test. Alternatives such as supported decision-making may be less restrictive and can better serve patients, she said. Supported decision-making allows for a person with disabilities to receive assistance from a supporter who can help a patient process medical conditions and treatment needs. The supporter helps empower capable patients to decide on their own.

Some states have introduced legislation that would legally recognize supported decision-making as a less restrictive alternative to guardianship or conservatorship, in which a court-appointed individual manages all aspects of a person’s life.

Sara Mixter, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and a co-moderator of the workshop, called the use of inclusive language in patient communication the “first step toward fostering an environment where patients feel respected and understood.”

Inclusive conversations can include person-first language and using words such as “caregiver” rather than “caretaker.”

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Mixter also called for the directors of residency programs to provide more training on disabilities. They cited a 2023 survey of directors, many of whom said that educational boards do not require training in disability-specific care and that experts in the care of people with disabilities are few and far between.

“Education and awareness are key to overcoming the challenges we face,” Dr. Thomas said. “Improving our training programs means we can ensure that all patients receive the care and respect they deserve.”

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Mixter report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Former UCLA Doctor Receives $14 Million in Gender Discrimination Retrial

A California jury has awarded $14 million to a former University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) oncologist who claimed she was paid thousands less than her male colleagues and wrongfully terminated after her complaints of gender-based harassment and intimidation were ignored by program leadership.

The decision comes after a lengthy 8-year legal battle in which an appellate judge reversed a previous jury decision in her favor.

Lauren Pinter-Brown, MD, a hematologic oncologist, was hired in 2005 by the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine — now called UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. As the school’s lymphoma program director, she conducted clinical research alongside other oncology doctors, including Sven de Vos, MD.

She claimed that her professional relationship with Dr. de Vos became contentious after he demonstrated “oppositional” and “disrespectful” behavior at team meetings, such as talking over her and turning his chair so Dr. Pinter-Brown faced his back. Court documents indicated that Dr. de Vos refused to use Dr. Pinter-Brown’s title in front of colleagues despite doing so for male counterparts.

Dr. Pinter-Brown argued that she was treated as the “butt of a joke” by Dr. de Vos and other male colleagues. In 2016, she sued Dr. de Vos, the university, and its governing body, the Board of Regents, for wrongful termination.

She was awarded a $13 million verdict in 2018. However, the California Court of Appeals overturned it in 2020 after concluding that several mistakes during the court proceedings impeded the school’s right to a fair and impartial trial. The case was retried, culminating in the even higher award of $14 million issued on May 9.

“Two juries have come to virtually identical findings showing multiple problems at UCLA involving gender discrimination,” Dr. Pinter-Brown’s attorney, Carney R. Shegerian, JD, told this news organization.

A spokesperson from UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine said administrators are carefully reviewing the new decision.

The spokesperson told this news organization that the medical school and its health system remain “deeply committed to maintaining a workplace free from discrimination, intimidation, retaliation, or harassment of any kind” and fostering a “respectful and inclusive environment ... in research, medical education, and patient care.”

Gender Pay Disparities Persist in Medicine

The gender pay gap in medicine is well documented. The 2024 Medscape Physician Compensation Report found that male doctors earn about 29% more than their female counterparts, with the disparity growing larger among specialists. In addition, a recent JAMA Health Forum study found that male physicians earned 21%-24% more per hour than female physicians.

Dr. Pinter-Brown, who now works at the University of California, Irvine, alleged that she was paid $200,000 less annually, on average, than her male colleagues.

That’s not surprising, says Martha Gulati, MD, professor and director of preventive cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles. She coauthored a commentary about gender disparities in JAMA Network Open. Dr. Gulati told this news organization that even a “small” pay disparity of $100,000 annually adds up.

“Let’s say the [male physician] invests it at 3% and adds to it yearly. Even without a raise, in 20 years, that is approximately $3 million,” Dr. Gulati explained. “Once you find out you are paid less than your male colleagues, you are upset. Your sense of value and self-worth disappears.”

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, president-elect of the American Medical Women’s Association, said that gender discrimination is likely more prevalent than research indicates. She told this news organization that self-doubt and fear of retaliation keep many from exposing the mistreatment.

Although more women are entering medicine, too few rise to the highest positions, Dr. Barrett said.

“Unfortunately, many are pulled and pushed into specialties and subspecialties that have lower compensation and are not promoted to leadership, so just having numbers isn’t enough to achieve equity,” Dr. Barrett said.

Dr. Pinter-Brown claimed she was repeatedly harassed and intimidated by Dr. de Vos from 2008 to 2015. Despite voicing concerns multiple times about the discriminatory behavior, the only resolutions offered by the male-dominated program leadership were for her to separate from the group and conduct lymphoma research independently or to avoid interacting with Dr. de Vos, court records said.

Even the school’s male Title IX officer, Jan Tillisch, MD, who handled gender-based discrimination complaints, reportedly made sexist comments. When Dr. Pinter-Brown sought his help, he allegedly told her that she had a reputation as an “angry woman” and “diva,” court records showed.

According to court documents, Dr. Pinter-Brown endured nitpicking and research audits as retaliation for speaking out, temporarily suspending her research privileges. She said she was subsequently removed from the director position and replaced by Dr. de Vos.

Female physicians who report discriminatory behavior often have unfavorable outcomes and risk future career prospects, Dr. Gulati said.

To shift this dynamic, she said institutions must increase transparency and practices that support female doctors receiving “equal pay for equal work.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A California jury has awarded $14 million to a former University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) oncologist who claimed she was paid thousands less than her male colleagues and wrongfully terminated after her complaints of gender-based harassment and intimidation were ignored by program leadership.

The decision comes after a lengthy 8-year legal battle in which an appellate judge reversed a previous jury decision in her favor.

Lauren Pinter-Brown, MD, a hematologic oncologist, was hired in 2005 by the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine — now called UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. As the school’s lymphoma program director, she conducted clinical research alongside other oncology doctors, including Sven de Vos, MD.

She claimed that her professional relationship with Dr. de Vos became contentious after he demonstrated “oppositional” and “disrespectful” behavior at team meetings, such as talking over her and turning his chair so Dr. Pinter-Brown faced his back. Court documents indicated that Dr. de Vos refused to use Dr. Pinter-Brown’s title in front of colleagues despite doing so for male counterparts.

Dr. Pinter-Brown argued that she was treated as the “butt of a joke” by Dr. de Vos and other male colleagues. In 2016, she sued Dr. de Vos, the university, and its governing body, the Board of Regents, for wrongful termination.

She was awarded a $13 million verdict in 2018. However, the California Court of Appeals overturned it in 2020 after concluding that several mistakes during the court proceedings impeded the school’s right to a fair and impartial trial. The case was retried, culminating in the even higher award of $14 million issued on May 9.

“Two juries have come to virtually identical findings showing multiple problems at UCLA involving gender discrimination,” Dr. Pinter-Brown’s attorney, Carney R. Shegerian, JD, told this news organization.

A spokesperson from UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine said administrators are carefully reviewing the new decision.

The spokesperson told this news organization that the medical school and its health system remain “deeply committed to maintaining a workplace free from discrimination, intimidation, retaliation, or harassment of any kind” and fostering a “respectful and inclusive environment ... in research, medical education, and patient care.”

Gender Pay Disparities Persist in Medicine

The gender pay gap in medicine is well documented. The 2024 Medscape Physician Compensation Report found that male doctors earn about 29% more than their female counterparts, with the disparity growing larger among specialists. In addition, a recent JAMA Health Forum study found that male physicians earned 21%-24% more per hour than female physicians.

Dr. Pinter-Brown, who now works at the University of California, Irvine, alleged that she was paid $200,000 less annually, on average, than her male colleagues.

That’s not surprising, says Martha Gulati, MD, professor and director of preventive cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles. She coauthored a commentary about gender disparities in JAMA Network Open. Dr. Gulati told this news organization that even a “small” pay disparity of $100,000 annually adds up.

“Let’s say the [male physician] invests it at 3% and adds to it yearly. Even without a raise, in 20 years, that is approximately $3 million,” Dr. Gulati explained. “Once you find out you are paid less than your male colleagues, you are upset. Your sense of value and self-worth disappears.”

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, president-elect of the American Medical Women’s Association, said that gender discrimination is likely more prevalent than research indicates. She told this news organization that self-doubt and fear of retaliation keep many from exposing the mistreatment.

Although more women are entering medicine, too few rise to the highest positions, Dr. Barrett said.

“Unfortunately, many are pulled and pushed into specialties and subspecialties that have lower compensation and are not promoted to leadership, so just having numbers isn’t enough to achieve equity,” Dr. Barrett said.

Dr. Pinter-Brown claimed she was repeatedly harassed and intimidated by Dr. de Vos from 2008 to 2015. Despite voicing concerns multiple times about the discriminatory behavior, the only resolutions offered by the male-dominated program leadership were for her to separate from the group and conduct lymphoma research independently or to avoid interacting with Dr. de Vos, court records said.

Even the school’s male Title IX officer, Jan Tillisch, MD, who handled gender-based discrimination complaints, reportedly made sexist comments. When Dr. Pinter-Brown sought his help, he allegedly told her that she had a reputation as an “angry woman” and “diva,” court records showed.

According to court documents, Dr. Pinter-Brown endured nitpicking and research audits as retaliation for speaking out, temporarily suspending her research privileges. She said she was subsequently removed from the director position and replaced by Dr. de Vos.

Female physicians who report discriminatory behavior often have unfavorable outcomes and risk future career prospects, Dr. Gulati said.

To shift this dynamic, she said institutions must increase transparency and practices that support female doctors receiving “equal pay for equal work.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A California jury has awarded $14 million to a former University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) oncologist who claimed she was paid thousands less than her male colleagues and wrongfully terminated after her complaints of gender-based harassment and intimidation were ignored by program leadership.

The decision comes after a lengthy 8-year legal battle in which an appellate judge reversed a previous jury decision in her favor.

Lauren Pinter-Brown, MD, a hematologic oncologist, was hired in 2005 by the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine — now called UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. As the school’s lymphoma program director, she conducted clinical research alongside other oncology doctors, including Sven de Vos, MD.

She claimed that her professional relationship with Dr. de Vos became contentious after he demonstrated “oppositional” and “disrespectful” behavior at team meetings, such as talking over her and turning his chair so Dr. Pinter-Brown faced his back. Court documents indicated that Dr. de Vos refused to use Dr. Pinter-Brown’s title in front of colleagues despite doing so for male counterparts.

Dr. Pinter-Brown argued that she was treated as the “butt of a joke” by Dr. de Vos and other male colleagues. In 2016, she sued Dr. de Vos, the university, and its governing body, the Board of Regents, for wrongful termination.

She was awarded a $13 million verdict in 2018. However, the California Court of Appeals overturned it in 2020 after concluding that several mistakes during the court proceedings impeded the school’s right to a fair and impartial trial. The case was retried, culminating in the even higher award of $14 million issued on May 9.

“Two juries have come to virtually identical findings showing multiple problems at UCLA involving gender discrimination,” Dr. Pinter-Brown’s attorney, Carney R. Shegerian, JD, told this news organization.

A spokesperson from UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine said administrators are carefully reviewing the new decision.

The spokesperson told this news organization that the medical school and its health system remain “deeply committed to maintaining a workplace free from discrimination, intimidation, retaliation, or harassment of any kind” and fostering a “respectful and inclusive environment ... in research, medical education, and patient care.”

Gender Pay Disparities Persist in Medicine

The gender pay gap in medicine is well documented. The 2024 Medscape Physician Compensation Report found that male doctors earn about 29% more than their female counterparts, with the disparity growing larger among specialists. In addition, a recent JAMA Health Forum study found that male physicians earned 21%-24% more per hour than female physicians.

Dr. Pinter-Brown, who now works at the University of California, Irvine, alleged that she was paid $200,000 less annually, on average, than her male colleagues.

That’s not surprising, says Martha Gulati, MD, professor and director of preventive cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles. She coauthored a commentary about gender disparities in JAMA Network Open. Dr. Gulati told this news organization that even a “small” pay disparity of $100,000 annually adds up.

“Let’s say the [male physician] invests it at 3% and adds to it yearly. Even without a raise, in 20 years, that is approximately $3 million,” Dr. Gulati explained. “Once you find out you are paid less than your male colleagues, you are upset. Your sense of value and self-worth disappears.”

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, president-elect of the American Medical Women’s Association, said that gender discrimination is likely more prevalent than research indicates. She told this news organization that self-doubt and fear of retaliation keep many from exposing the mistreatment.

Although more women are entering medicine, too few rise to the highest positions, Dr. Barrett said.

“Unfortunately, many are pulled and pushed into specialties and subspecialties that have lower compensation and are not promoted to leadership, so just having numbers isn’t enough to achieve equity,” Dr. Barrett said.

Dr. Pinter-Brown claimed she was repeatedly harassed and intimidated by Dr. de Vos from 2008 to 2015. Despite voicing concerns multiple times about the discriminatory behavior, the only resolutions offered by the male-dominated program leadership were for her to separate from the group and conduct lymphoma research independently or to avoid interacting with Dr. de Vos, court records said.

Even the school’s male Title IX officer, Jan Tillisch, MD, who handled gender-based discrimination complaints, reportedly made sexist comments. When Dr. Pinter-Brown sought his help, he allegedly told her that she had a reputation as an “angry woman” and “diva,” court records showed.

According to court documents, Dr. Pinter-Brown endured nitpicking and research audits as retaliation for speaking out, temporarily suspending her research privileges. She said she was subsequently removed from the director position and replaced by Dr. de Vos.

Female physicians who report discriminatory behavior often have unfavorable outcomes and risk future career prospects, Dr. Gulati said.

To shift this dynamic, she said institutions must increase transparency and practices that support female doctors receiving “equal pay for equal work.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Resource Menu Gives Choice to Caregivers Struggling to Meet Basic Needs

Screenings may not be the way to get needed resources to children and their caregivers, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS).

Caregivers and parents who were asked if they wanted assistance in several areas of need, including transportation and childcare, were nearly twice as likely to say they wanted such help than those who received a screening on current hardships. Generally, each questionnaire is administered in front of their children in primary care or pediatric hospital settings.

“Families have a lot of concern about being seen a different way by their healthcare team, being seen as unfit, and having child protective services involved in their childcare for issues related to poverty,” said Danielle Cullen, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Cullen and her colleagues analyzed data from nearly 4000 caregivers of children up to age 21 at emergency departments or primary care clinics at CHOP between 2021 and 2023.

Caregivers were randomly assigned to one of three arms — screening with a version of WE CARE (Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education), use of an online menu of options for help in areas like housing, or neither approach.

Caregivers in all three arms received a map of resources and a follow-up text from a resource navigator to assist them as needed.

Nearly 40% of caregivers who presented with the digital menu said they wanted resources compared with 29% of those who were screened (P < .001). Non-native English speakers given the menu were 2.5 times more likely to say yes to resources compared with those who were screened.

“We need to be thoughtful about these mandates to screen for social determinants of health: It’s not that straightforward,” said Esther K. Chung, MD, a pediatrician and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington Medicine in Seattle, who was not involved in the study. “What we’re getting from this study is that patients want choice, and the menu provides them choice.”

Dr. Cullen said the menu option allows caregivers to make choices based on their priorities and not on whether they meet the screening thresholds for need.

While some health clinics utilize tablet forms for screenings to offer more privacy with questions, asking direct questions about income, food insecurity, and housing stability can be stigmatizing, Dr. Cullen said.

“Screening positive for social risk doesn’t mean that you actually want resources, and on the flip side, the literature shows that about half of the people who screen negative want resources,” she said.

Dr. Cullen and her team also conducted follow-up interviews with caregivers and found many feared that their clinician would assume a medical condition was connected to living conditions. They also had concerns about insurance companies gaining access to the data and using it to deny coverage or raise costs.

Spanish-speaking caregivers cited fears about their immigration status, experiences of discrimination, and language barriers when trying to access resources.

Participants said a few key strategies could make screening less intimidating, such as abstaining from screening during a serious medical visit, asking for consent to record answers in medical records, and communicating in an empathetic manner.

“Some families are a bit surprised when we ask about things like housing and food insecurity, but I think as long as we contextualize it, we can minimize the stigma associated with it,” Dr. Chung said. “That takes quite a bit of nuance and skill.”

The study was funded by the William T. Grant Foundation and the Emergency Medicine Foundation. The authors reported no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Screenings may not be the way to get needed resources to children and their caregivers, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS).

Caregivers and parents who were asked if they wanted assistance in several areas of need, including transportation and childcare, were nearly twice as likely to say they wanted such help than those who received a screening on current hardships. Generally, each questionnaire is administered in front of their children in primary care or pediatric hospital settings.

“Families have a lot of concern about being seen a different way by their healthcare team, being seen as unfit, and having child protective services involved in their childcare for issues related to poverty,” said Danielle Cullen, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Cullen and her colleagues analyzed data from nearly 4000 caregivers of children up to age 21 at emergency departments or primary care clinics at CHOP between 2021 and 2023.

Caregivers were randomly assigned to one of three arms — screening with a version of WE CARE (Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education), use of an online menu of options for help in areas like housing, or neither approach.

Caregivers in all three arms received a map of resources and a follow-up text from a resource navigator to assist them as needed.

Nearly 40% of caregivers who presented with the digital menu said they wanted resources compared with 29% of those who were screened (P < .001). Non-native English speakers given the menu were 2.5 times more likely to say yes to resources compared with those who were screened.

“We need to be thoughtful about these mandates to screen for social determinants of health: It’s not that straightforward,” said Esther K. Chung, MD, a pediatrician and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington Medicine in Seattle, who was not involved in the study. “What we’re getting from this study is that patients want choice, and the menu provides them choice.”

Dr. Cullen said the menu option allows caregivers to make choices based on their priorities and not on whether they meet the screening thresholds for need.

While some health clinics utilize tablet forms for screenings to offer more privacy with questions, asking direct questions about income, food insecurity, and housing stability can be stigmatizing, Dr. Cullen said.

“Screening positive for social risk doesn’t mean that you actually want resources, and on the flip side, the literature shows that about half of the people who screen negative want resources,” she said.

Dr. Cullen and her team also conducted follow-up interviews with caregivers and found many feared that their clinician would assume a medical condition was connected to living conditions. They also had concerns about insurance companies gaining access to the data and using it to deny coverage or raise costs.

Spanish-speaking caregivers cited fears about their immigration status, experiences of discrimination, and language barriers when trying to access resources.

Participants said a few key strategies could make screening less intimidating, such as abstaining from screening during a serious medical visit, asking for consent to record answers in medical records, and communicating in an empathetic manner.

“Some families are a bit surprised when we ask about things like housing and food insecurity, but I think as long as we contextualize it, we can minimize the stigma associated with it,” Dr. Chung said. “That takes quite a bit of nuance and skill.”

The study was funded by the William T. Grant Foundation and the Emergency Medicine Foundation. The authors reported no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Screenings may not be the way to get needed resources to children and their caregivers, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS).

Caregivers and parents who were asked if they wanted assistance in several areas of need, including transportation and childcare, were nearly twice as likely to say they wanted such help than those who received a screening on current hardships. Generally, each questionnaire is administered in front of their children in primary care or pediatric hospital settings.

“Families have a lot of concern about being seen a different way by their healthcare team, being seen as unfit, and having child protective services involved in their childcare for issues related to poverty,” said Danielle Cullen, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Cullen and her colleagues analyzed data from nearly 4000 caregivers of children up to age 21 at emergency departments or primary care clinics at CHOP between 2021 and 2023.

Caregivers were randomly assigned to one of three arms — screening with a version of WE CARE (Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education), use of an online menu of options for help in areas like housing, or neither approach.

Caregivers in all three arms received a map of resources and a follow-up text from a resource navigator to assist them as needed.

Nearly 40% of caregivers who presented with the digital menu said they wanted resources compared with 29% of those who were screened (P < .001). Non-native English speakers given the menu were 2.5 times more likely to say yes to resources compared with those who were screened.

“We need to be thoughtful about these mandates to screen for social determinants of health: It’s not that straightforward,” said Esther K. Chung, MD, a pediatrician and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington Medicine in Seattle, who was not involved in the study. “What we’re getting from this study is that patients want choice, and the menu provides them choice.”

Dr. Cullen said the menu option allows caregivers to make choices based on their priorities and not on whether they meet the screening thresholds for need.

While some health clinics utilize tablet forms for screenings to offer more privacy with questions, asking direct questions about income, food insecurity, and housing stability can be stigmatizing, Dr. Cullen said.

“Screening positive for social risk doesn’t mean that you actually want resources, and on the flip side, the literature shows that about half of the people who screen negative want resources,” she said.

Dr. Cullen and her team also conducted follow-up interviews with caregivers and found many feared that their clinician would assume a medical condition was connected to living conditions. They also had concerns about insurance companies gaining access to the data and using it to deny coverage or raise costs.

Spanish-speaking caregivers cited fears about their immigration status, experiences of discrimination, and language barriers when trying to access resources.

Participants said a few key strategies could make screening less intimidating, such as abstaining from screening during a serious medical visit, asking for consent to record answers in medical records, and communicating in an empathetic manner.

“Some families are a bit surprised when we ask about things like housing and food insecurity, but I think as long as we contextualize it, we can minimize the stigma associated with it,” Dr. Chung said. “That takes quite a bit of nuance and skill.”

The study was funded by the William T. Grant Foundation and the Emergency Medicine Foundation. The authors reported no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PAS 2024

Exploring Skin Pigmentation Adaptation: A Systematic Review on the Vitamin D Adaptation Hypothesis

The risk for developing skin cancer can be somewhat attributed to variations in skin pigmentation. Historically, lighter skin pigmentation has been observed in populations living in higher latitudes and darker pigmentation in populations near the equator. Although skin pigmentation is a conglomeration of genetic and environmental factors, anthropologic studies have demonstrated an association of human skin lightening with historic human migratory patterns.1 It is postulated that migration to latitudes with less UVB light penetration has resulted in a compensatory natural selection of lighter skin types. Furthermore, the driving force behind this migration-associated skin lightening has remained unclear.1

The need for folate metabolism, vitamin D synthesis, and barrier protection, as well as cultural practices, has been postulated as driving factors for skin pigmentation variation. Synthesis of vitamin D is a UV radiation (UVR)–dependent process and has remained a prominent theoretical driver for the basis of evolutionary skin lightening. Vitamin D can be acquired both exogenously or endogenously via dietary supplementation or sunlight; however, historically it has been obtained through UVB exposure primarily. Once UVB is absorbed by the skin, it catalyzes conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which is converted to vitamin D in the kidneys.2,3 It is suggested that lighter skin tones have an advantage over darker skin tones in synthesizing vitamin D at higher latitudes where there is less UVB, thus leading to the adaptation process.1 In this systematic review, we analyzed the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis and assessed the validity of evidence supporting this theory in the literature.

Methods

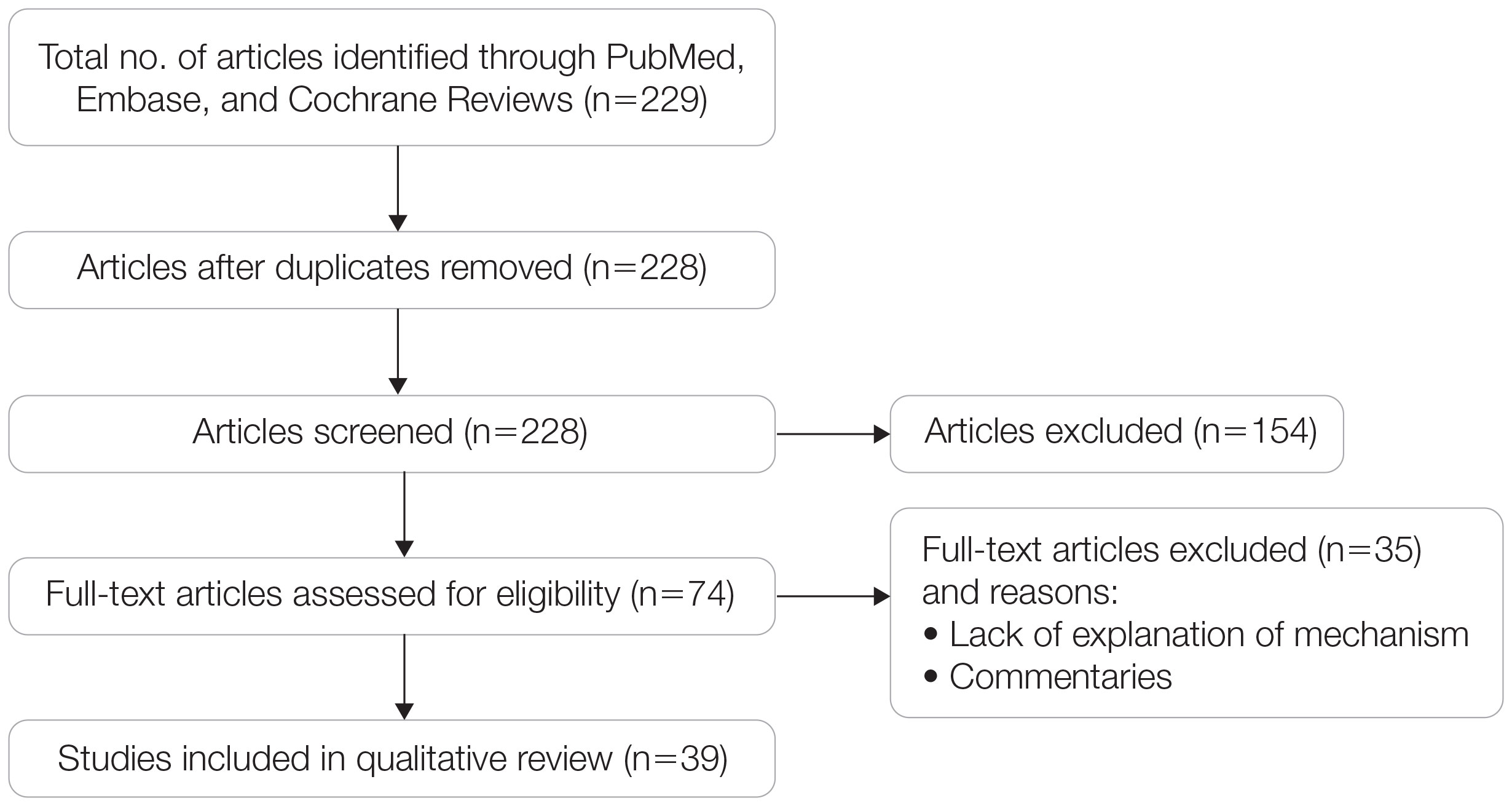

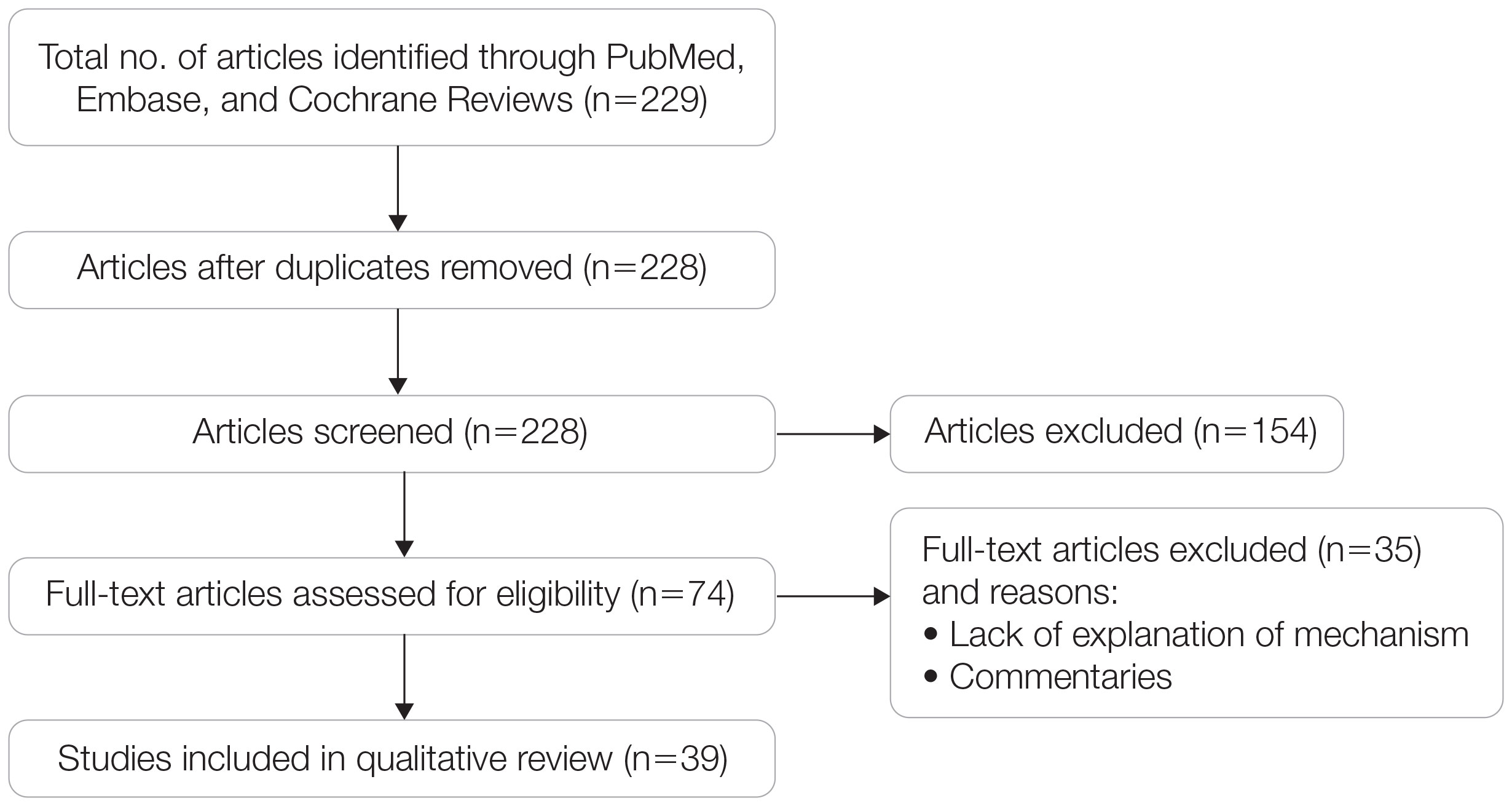

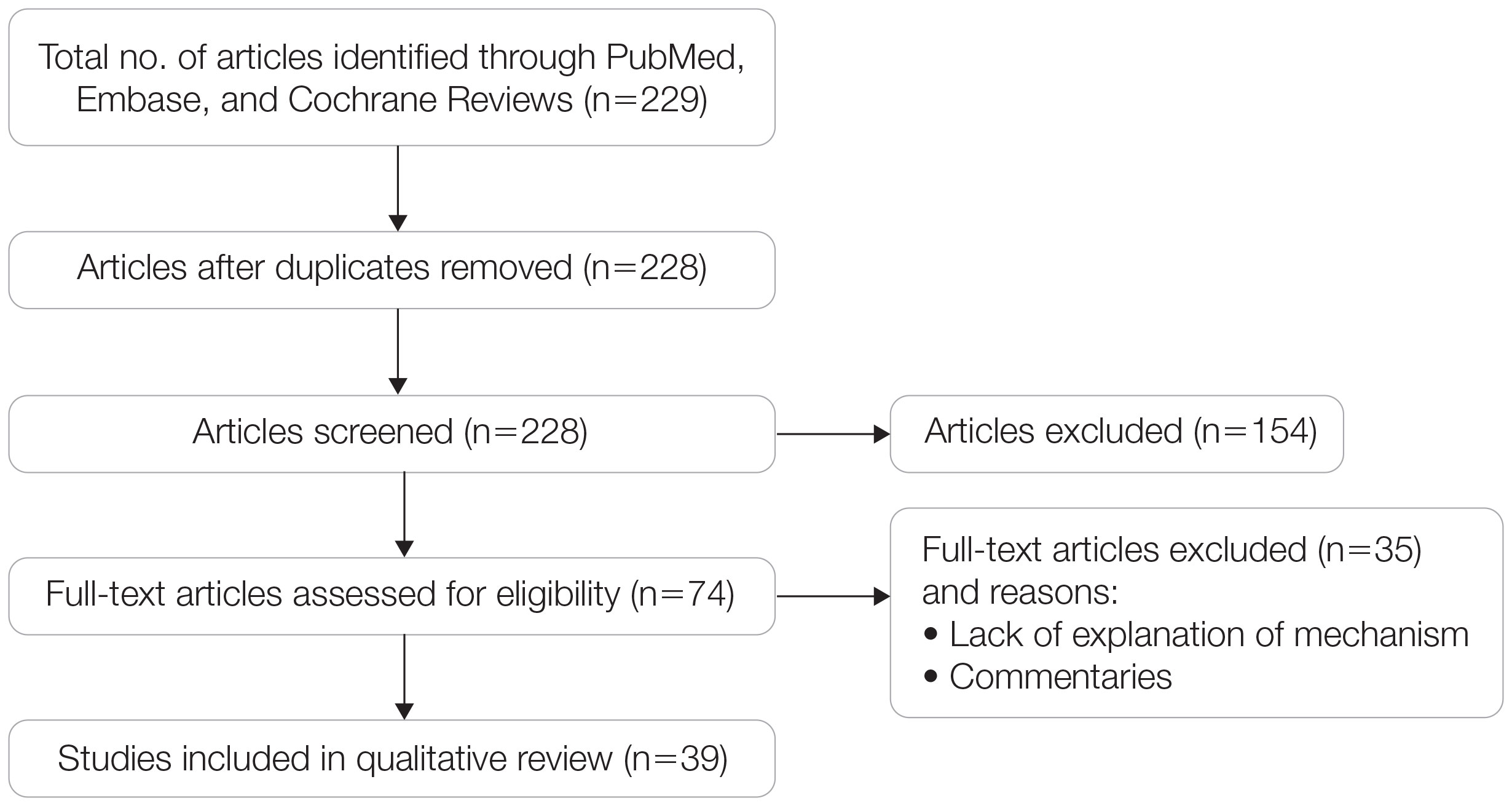

A search of PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Reviews database was conducted using the terms evolution, vitamin D, and skin to generate articles published from 2010 to 2022 that evaluated the influence of UVR-dependent production of vitamin D on skin pigmentation through historical migration patterns (Figure). Studies were excluded during an initial screening of abstracts followed by full-text assessment if they only had abstracts and if articles were inaccessible for review or in the form of case reports and commentaries.

The following data were extracted from each included study: reference citation, affiliated institutions of authors, author specialties, journal name, year of publication, study period, type of article, type of study, mechanism of adaptation, data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver, and data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver. Data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver were recorded from statistically significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotations. Data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver also were recorded from significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotes. The mechanism of adaptation was based on vitamin D synthesis modulation, melanin upregulation, genetic selections, genetic drift, mating patterns, increased vitamin D sensitivity, interbreeding, and diet.

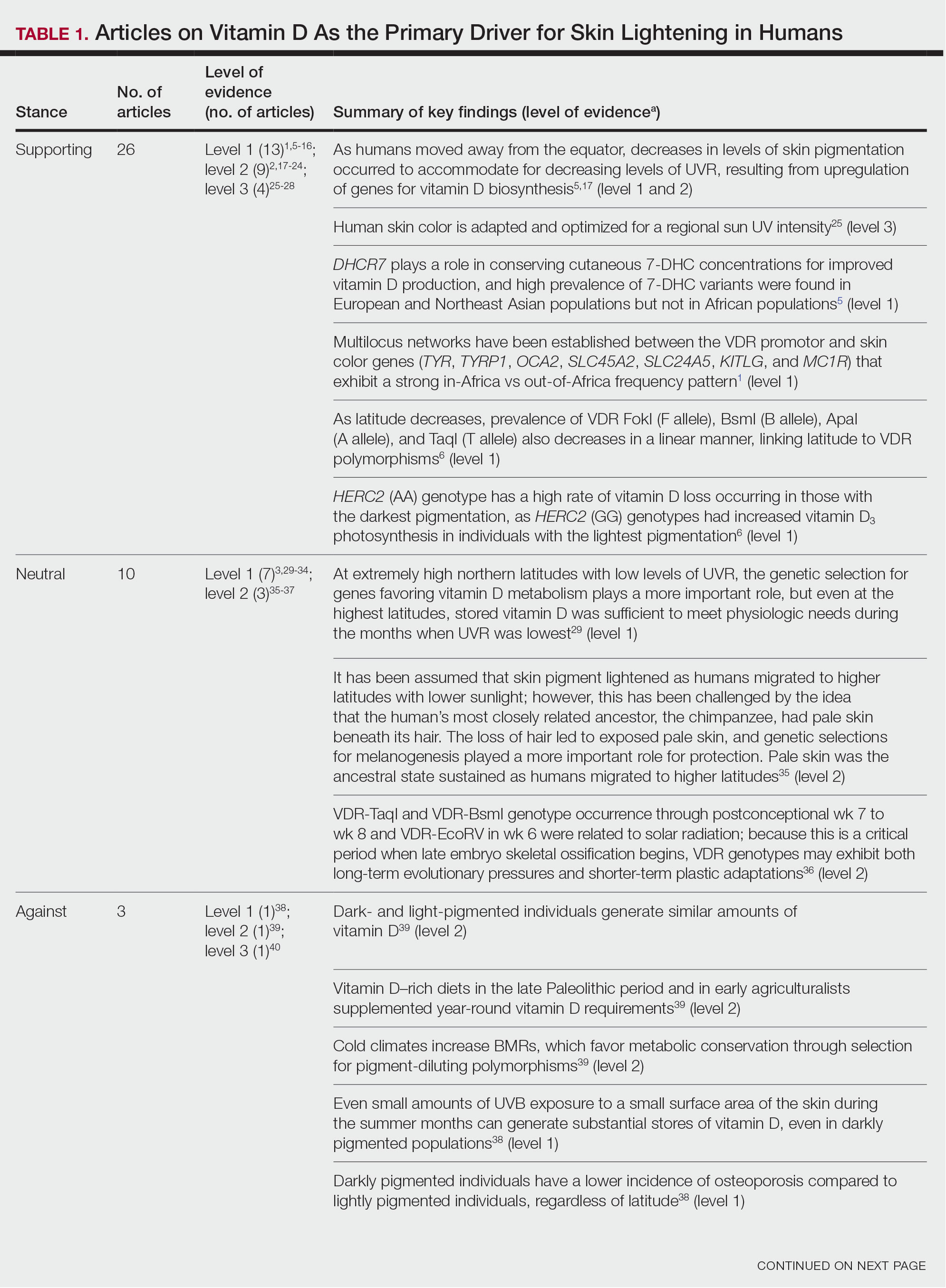

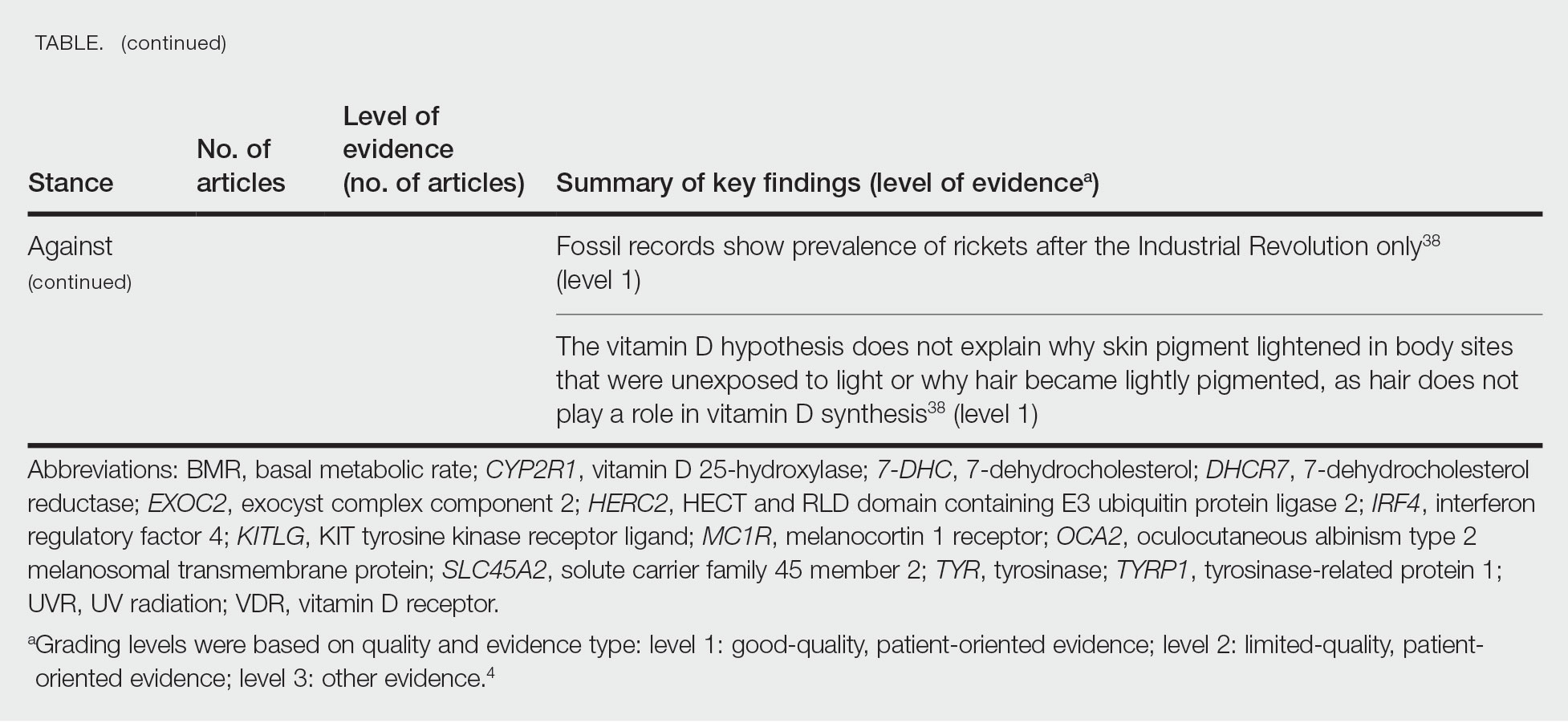

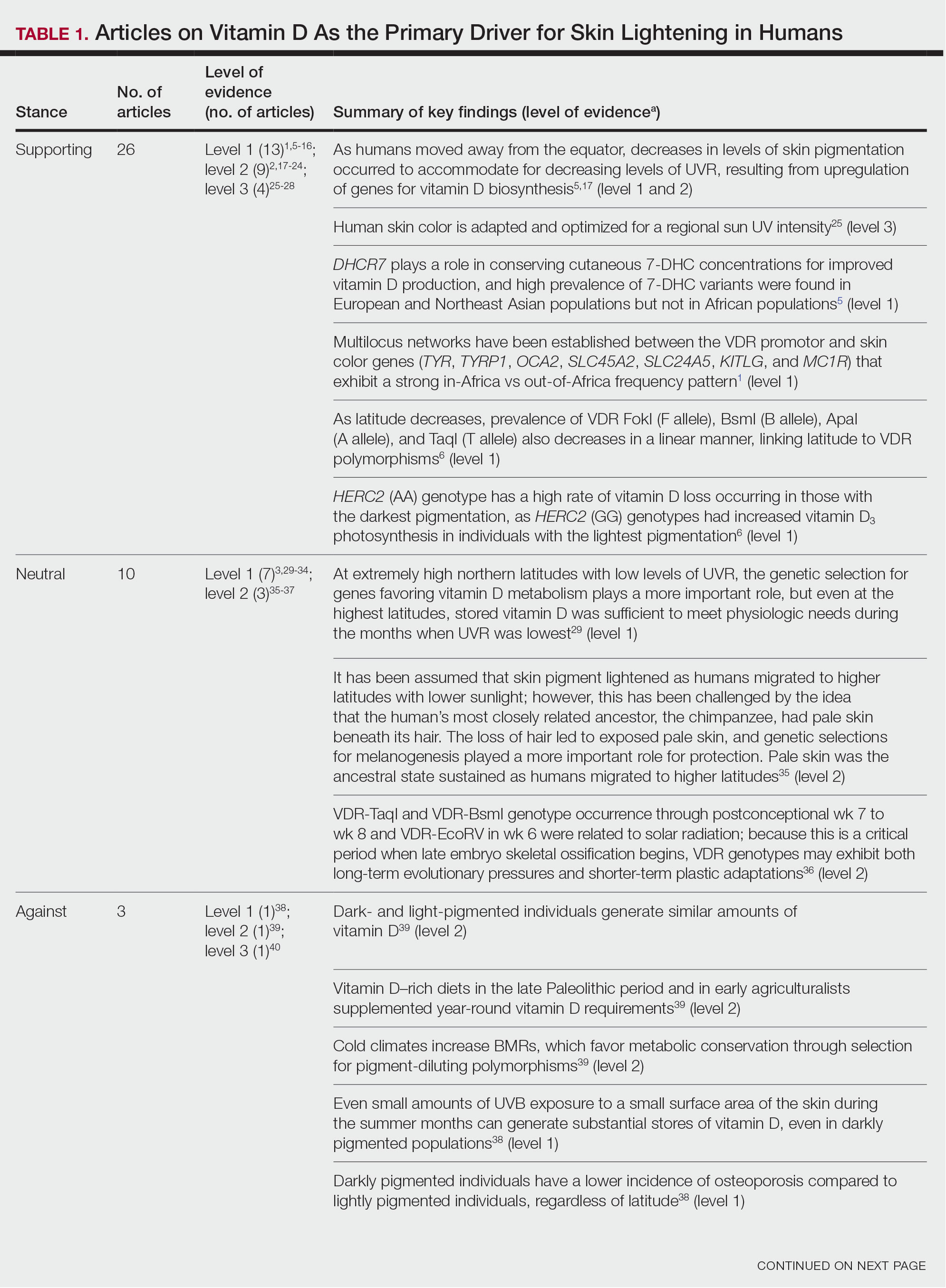

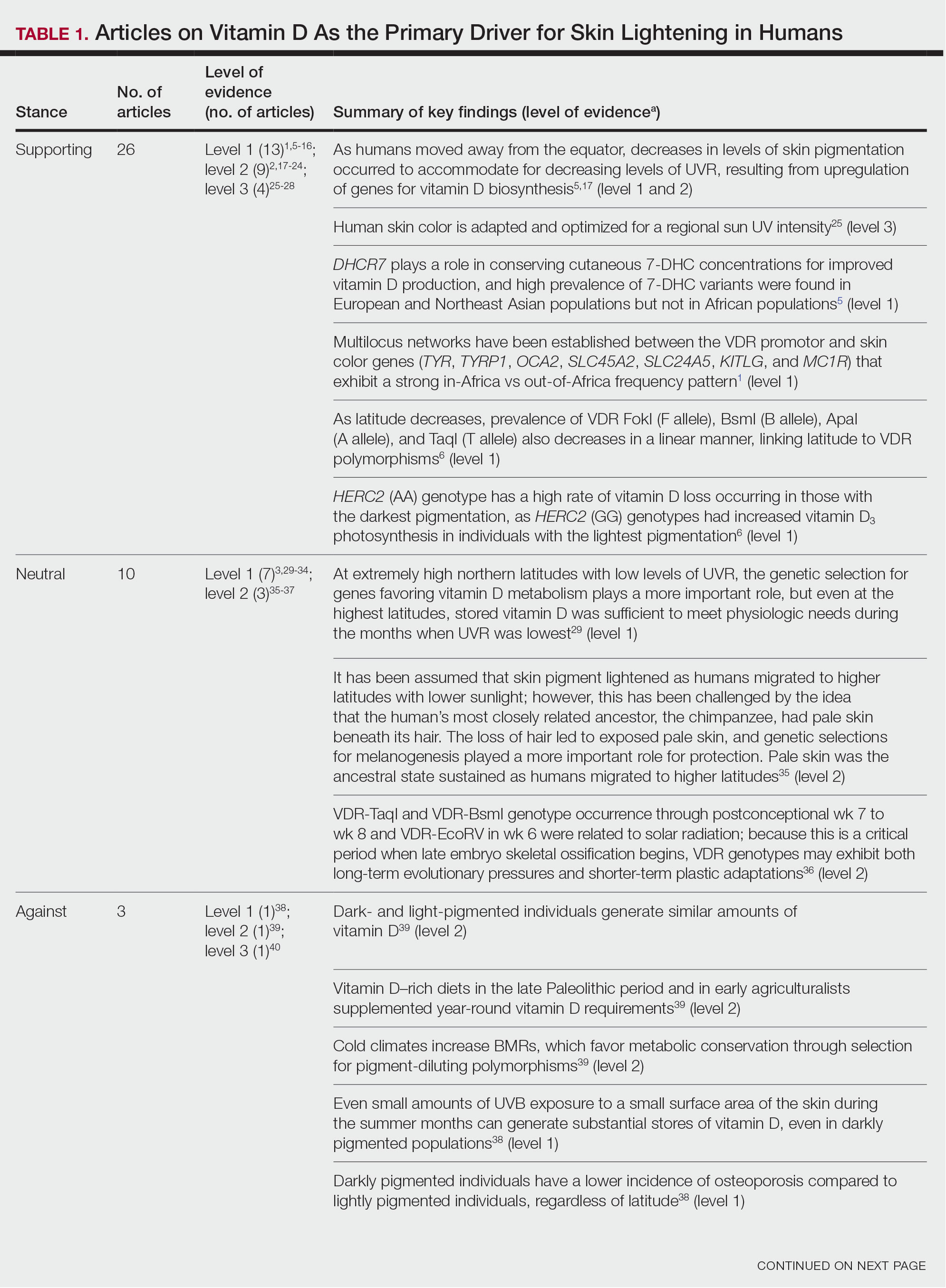

Studies included in the analysis were placed into 1 of 3 categories: supporting, neutral, and against. Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) criteria were used to classify the level of evidence of each article.4 Each article’s level of evidence was then graded (Table 1). The SORT grading levels were based on quality and evidence type: level 1 signified good-quality, patient-oriented evidence; level 2 signified limited-quality, patient-oriented evidence; and level 3 signified other evidence.4

Results

Article Selection—A total of 229 articles were identified for screening, and 39 studies met inclusion criteria.1-3,5-40 Systematic and retrospective reviews were the most common types of studies. Genomic analysis/sequencing/genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were the most common methods of analysis. Of these 39 articles, 26 were classified as supporting the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis, 10 were classified as neutral, and 3 were classified as against (Table 1).

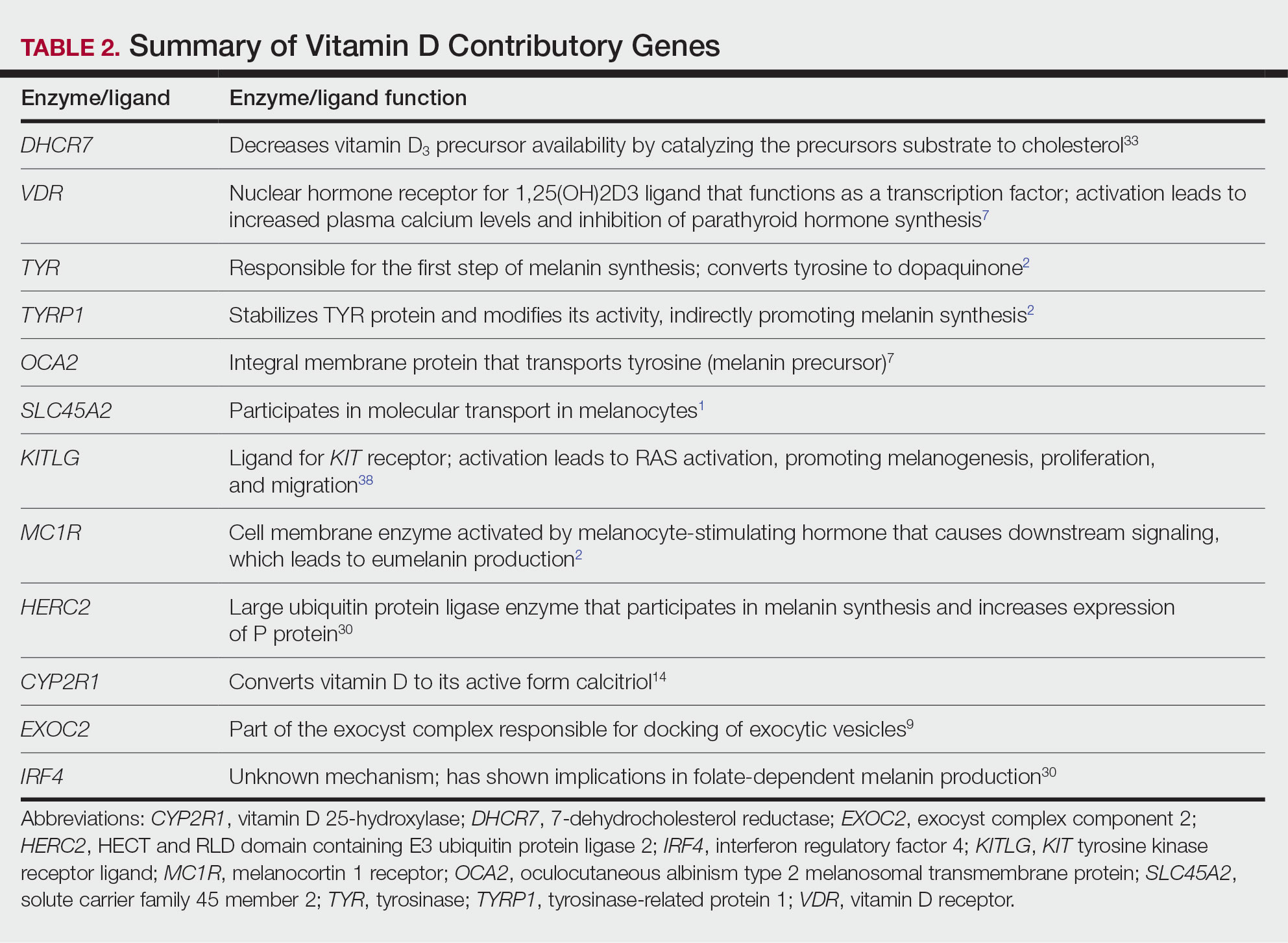

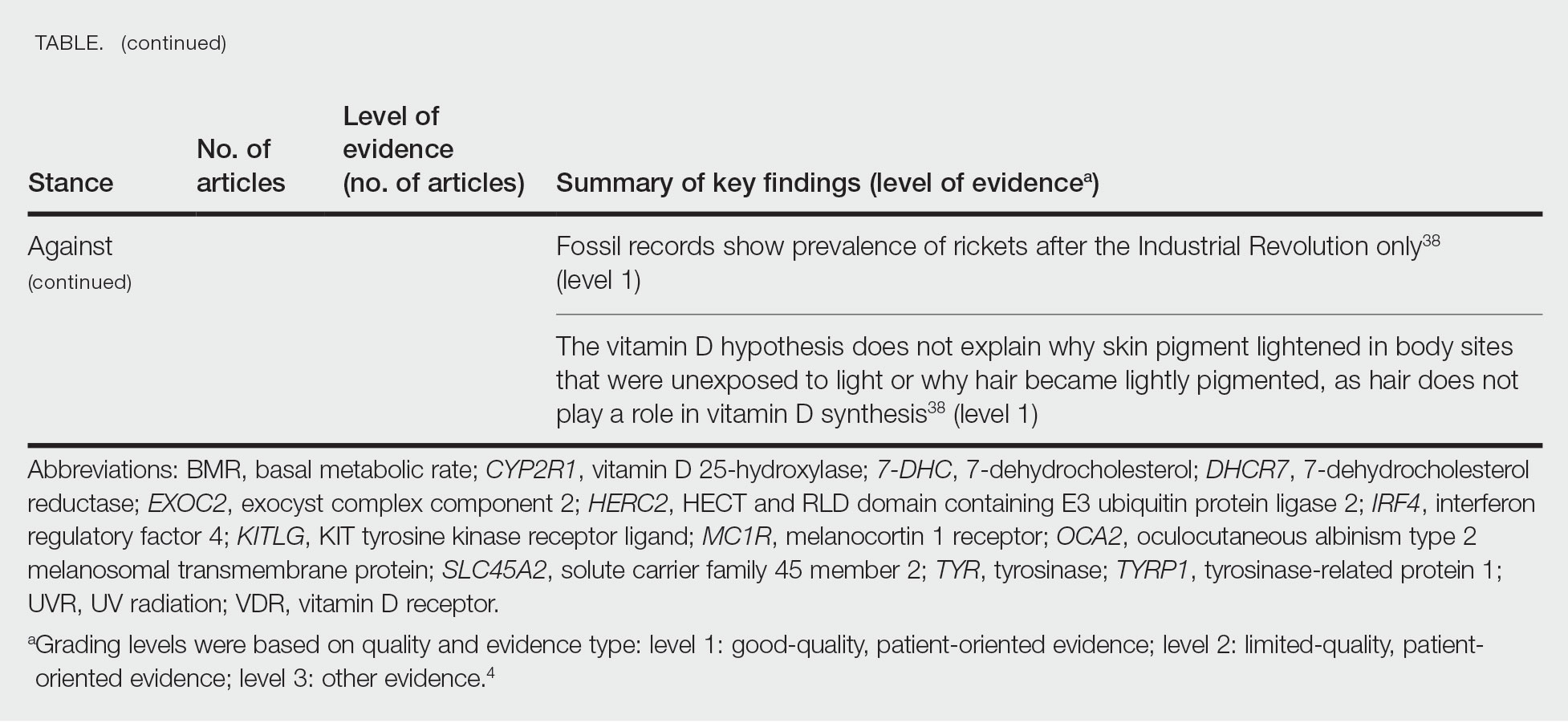

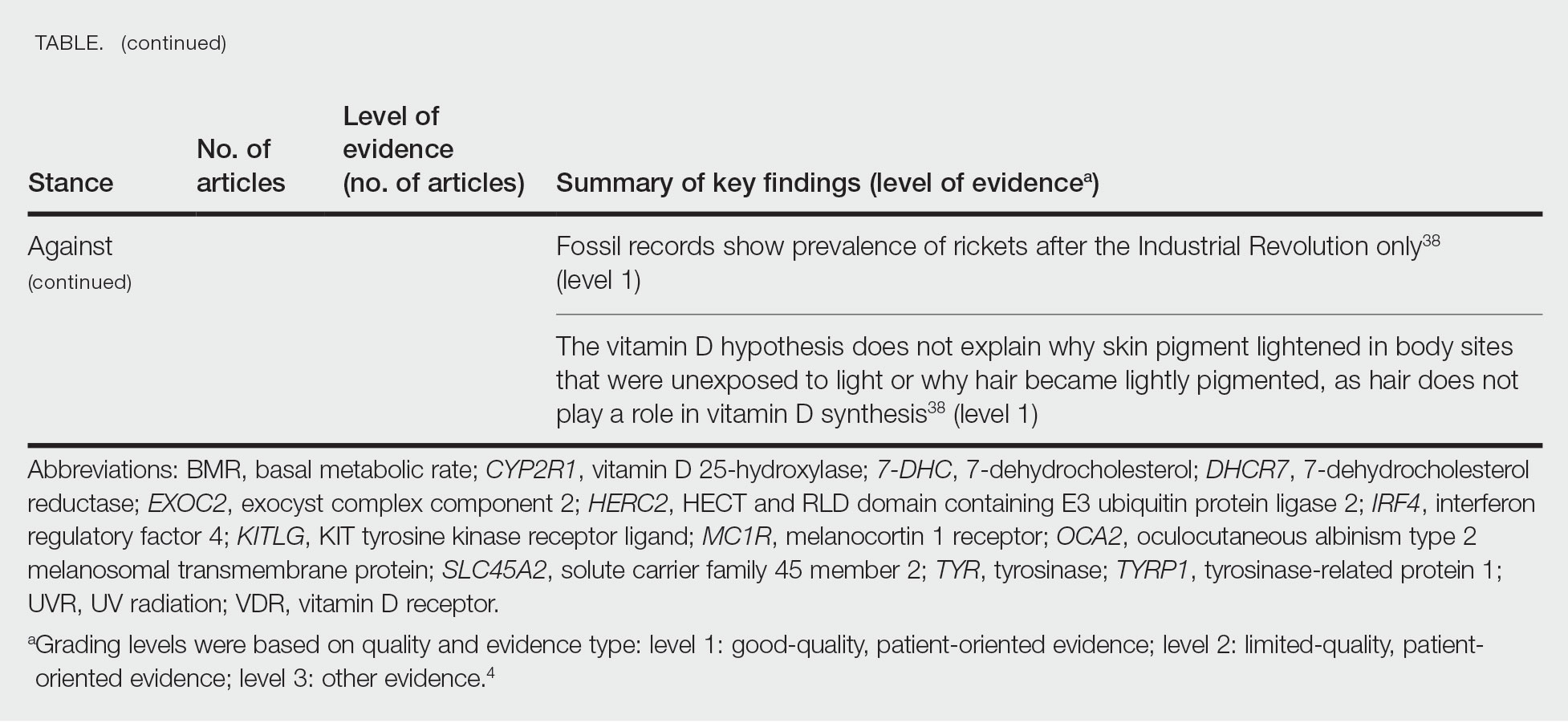

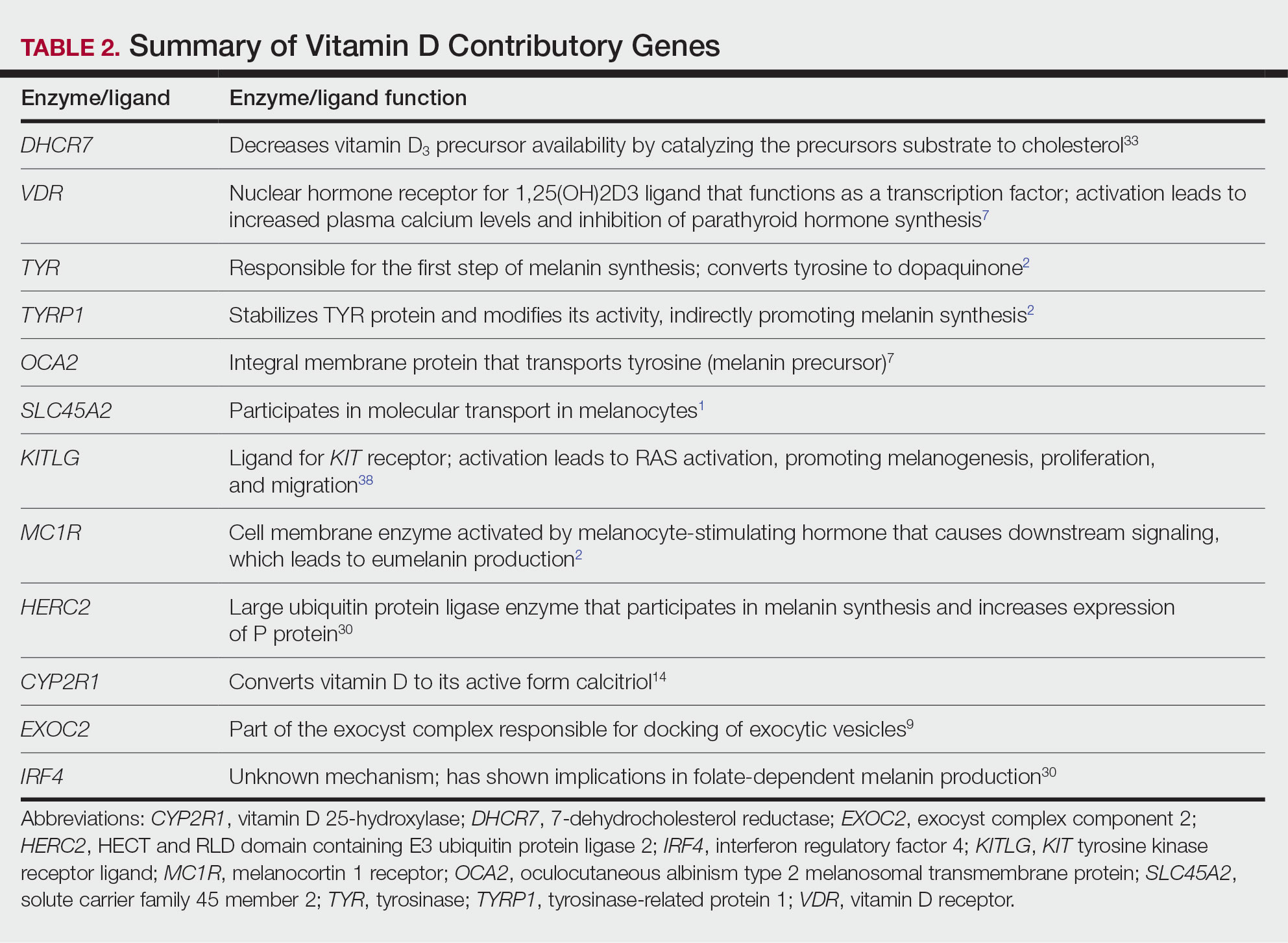

Of the articles classified as supporting the vitamin D hypothesis, 13 articles were level 1 evidence, 9 were level 2, and 4 were level 3. Key findings supporting the vitamin D hypothesis included genetic natural selection favoring vitamin D synthesis genes at higher latitudes with lower UVR and the skin lightening that occurred to protect against vitamin D deficiency (Table 1). Specific genes supporting these findings included 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7), vitamin D receptor (VDR), tyrosinase (TYR), tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1), oculocutaneous albinism type 2 melanosomal transmembrane protein (OCA2), solute carrier family 45 member 2 (SLC45A2), solute carrier family 4 member 5 (SLC24A5), Kit ligand (KITLG), melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), and HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 (HERC2)(Table 2).

Of the articles classified as being against the vitamin D hypothesis, 1 article was level 1 evidence, 1 was level 2, and 1 was level 3. Key findings refuting the vitamin D hypothesis included similar amounts of vitamin D synthesis in contemporary dark- and light-pigmented individuals, vitamin D–rich diets in the late Paleolithic period and in early agriculturalists, and metabolic conservation being the primary driver (Table 1).

Of the articles classified as neutral to the hypothesis, 7 articles were level 1 evidence and 3 were level 2. Key findings of these articles included genetic selection favoring vitamin D synthesis only for populations at extremely northern latitudes, skin lightening that was sustained in northern latitudes from the neighboring human ancestor the chimpanzee, and evidence for long-term evolutionary pressures and short-term plastic adaptations in vitamin D genes (Table 1).

Comment

The importance of appropriate vitamin D levels is hypothesized as a potent driver in skin lightening because the vitamin is essential for many biochemical processes within the human body. Proper calcification of bones requires activated vitamin D to prevent rickets in childhood. Pelvic deformation in women with rickets can obstruct childbirth in primitive medical environments.15 This direct reproductive impairment suggests a strong selective pressure for skin lightening in populations that migrated northward to enhance vitamin D synthesis.

Of the 39 articles that we reviewed, the majority (n=26 [66.7%]) supported the hypothesis that vitamin D synthesis was the main driver behind skin lightening, whereas 3 (7.7%) did not support the hypothesis and 10 (25.6%) were neutral. Other leading theories explaining skin lightening included the idea that enhanced melanogenesis protected against folate degradation; genetic selection for light-skin alleles due to genetic drift; skin lightening being the result of sexual selection; and a combination of factors, including dietary choices, clothing preferences, and skin permeability barriers.

Articles With Supporting Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—As Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa, migration patterns demonstrated the correlation between distance from the equator and skin pigmentation from natural selection. Individuals with darker skin pigment required higher levels of UVR to synthesize vitamin D. According to Beleza et al,1 as humans migrated to areas of higher latitudes with lower levels of UVR, natural selection favored the development of lighter skin to maximize vitamin D production. Vitamin D is linked to calcium metabolism, and its deficiency can lead to bone malformations and poor immune function.35 Several genes affecting melanogenesis and skin pigment have been found to have geospatial patterns that map to different geographic locations of various populations, indicating how human migration patterns out of Africa created this natural selection for skin lightening. The gene KITLG—associated with lighter skin pigmentation—has been found in high frequencies in both European and East Asian populations and is proposed to have increased in frequency after the migration out of Africa. However, the genes TYRP1, SLC24A5, and SLC45A2 were found at high frequencies only in European populations, and this selection occurred 11,000 to 19,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum (15,000–20,000 years ago), demonstrating the selection for European over East Asian characteristics. During this period, seasonal changes increased the risk for vitamin D deficiency and provided an urgency for selection to a lighter skin pigment.1

The migration of H sapiens to northern latitudes prompted the selection of alleles that would increasevitamin D synthesis to counteract the reduced UV exposure. Genetic analysis studies have found key associations between genes encoding for the metabolism of vitamin D and pigmentation. Among this complex network are the essential downstream enzymes in the melanocortin receptor 1 pathway, including TYR and TYRP1. Forty-six of 960 single-nucleotide polymorphisms located in 29 different genes involved in skin pigmentation that were analyzed in a cohort of 2970 individuals were significantly associated with serum vitamin D levels (P<.05). The exocyst complex component 2 (EXOC2), TYR, and TYRP1 gene variants were shown to have the greatest influence on vitamin D status.9 These data reveal how pigment genotypes are predictive of vitamin D levels and the epistatic potential among many genes in this complex network.

Gene variation plays an important role in vitamin D status when comparing genetic polymorphisms in populations in northern latitudes to African populations. Vitamin D3 precursor availability is decreased by 7-DHCR catalyzing the precursors substrate to cholesterol. In a study using GWAS, it was found that “variations in DHCR7 may aid vitamin D production by conserving cutaneous 7-DHC levels. A high prevalence of DHCR7 variants were found in European and Northeast Asian populations but not in African populations, suggesting that selection occurred for these DHCR7 mutations in populations who migrated to more northern latitudes.5 Multilocus networks have been established between the VDR promotor and skin color genes (Table 2) that exhibit a strong in-Africa vs out-of-Africa frequency pattern. It also has been shown that genetic variation (suggesting a long-term evolutionary inclination) and epigenetic modification (indicative of short-term exposure) of VDR lends support to the vitamin D hypothesis. As latitude decreases, prevalence of VDR FokI (F allele), BsmI (B allele), ApaI (A allele), and TaqI (T allele) also decreases in a linear manner, linking latitude to VDR polymorphisms. Plasma vitamin D levels and photoperiod of conception—UV exposure during the periconceptional period—also were extrapolative of VDR methylation in a study involving 80 participants, where these 2 factors accounted for 17% of variance in methylation.6

Other noteworthy genes included HERC2, which has implications in the expression of OCA2 (melanocyte-specific transporter protein), and IRF4, which encodes for an important enzyme in folate-dependent melanin production. In an Australian cross-sectional study that analyzed vitamin D and pigmentation gene polymorphisms in conjunction with plasma vitamin D levels, the most notable rate of vitamin D loss occurred in individuals with the darkest pigmentation HERC2 (AA) genotype.31 In contrast, the lightest pigmentation HERC2 (GG) genotypes had increased vitamin D3 photosynthesis. Interestingly, the lightest interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) TT genotype and the darkest HERC2 AA genotype, rendering the greatest folate loss and largest synthesis of vitamin D3, were not seen in combination in any of the participants.30 In addition to HERC2, derived alleles from pigment-associated genes SLC24A5*A and SLC45A2*G demonstrated greater frequencies in Europeans (>90%) compared to Africans and East Asians, where the allelic frequencies were either rare or absent.1 This evidence delineates not only the complexity but also the strong relationship between skin pigmentation, latitude, and vitamin D status. The GWAS also have supported this concept. In comparing European populations to African populations, there was a 4-fold increase in the frequencies of “derived alleles of the vitamin D transport protein (GC, rs3755967), the 25(OH)D3 synthesizing enzyme (CYP2R1, rs10741657), VDR (rs2228570 (commonly known as FokI polymorphism), rs1544410 (Bsm1), and rs731236 (Taq1) and the VDR target genes CYP24A1 (rs17216707), CD14 (rs2569190), and CARD9 (rs4077515).”32

Articles With Evidence Against the Vitamin D Theory—This review analyzed the level of support for the theory that vitamin D was the main driver for skin lightening. Although most articles supported this theory, there were articles that listed other plausible counterarguments. Jablonski and Chaplin3 suggested that humans living in higher latitudes compensated for increased demand of vitamin D by placing cultural importance on a diet of vitamin D–rich foods and thus would not have experienced decreased vitamin D levels, which we hypothesize were the driver for skin lightening. Elias et al39 argued that initial pigment dilution may have instead served to improve metabolic conservation, as the authors found no evidence of rickets—the sequelae of vitamin D deficiency—in pre–industrial age human fossils. Elias and Williams38 proposed that differences in skin pigment are due to a more intact skin permeability barrier as “a requirement for life in a desiccating terrestrial environment,” which is seen in darker skin tones compared to lighter skin tones and thus can survive better in warmer climates with less risk of infections or dehydration.

Articles With Neutral Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—Greaves41 argued against the idea that skin evolved to become lighter to protect against vitamin D deficiency. They proposed that the chimpanzee, which is the human’s most closely related species, had light skin covered by hair, and the loss of this hair led to exposed pale skin that created a need for increased melanin production for protection from UVR. Greaves41 stated that the MC1R gene (associated with darker pigmentation) was selected for in African populations, and those with pale skin retained their original pigment as they migrated to higher latitudes. Further research has demonstrated that the genetic natural selection for skin pigment is a complex process that involves multiple gene variants found throughout cultures across the globe.

Conclusion

Skin pigmentation has continuously evolved alongside humans. Genetic selection for lighter skin coincides with a favorable selection for genes involved in vitamin D synthesis as humans migrated to northern latitudes, which enabled humans to produce adequate levels of exogenous vitamin D in low-UVR areas and in turn promoted survival. Early humans without access to supplementation or foods rich in vitamin D acquired vitamin D primarily through sunlight. In comparison to modern society, where vitamin D supplementation is accessible and human lifespans are prolonged, lighter skin tone is now a risk factor for malignant cancers of the skin rather than being a protective adaptation. Current sun behavior recommendations conclude that the body’s need for vitamin D is satisfied by UV exposure to the arms, legs, hands, and/or face for only 5 to 30 minutes between 10

The hypothesis that skin lightening primarily was driven by the need for vitamin D can only be partially supported by our review. Studies have shown that there is a corresponding complex network of genes that determines skin pigmentation as well as vitamin D synthesis and conservation. However, there is sufficient evidence that skin lightening is multifactorial in nature, and vitamin D alone may not be the sole driver. The information in this review can be used by health care providers to educate patients on sun protection, given the lesser threat of severe vitamin D deficiency in developed communities today that have access to adequate nutrition and supplementation.

Skin lightening and its coinciding evolutionary drivers are a rather neglected area of research. Due to heterogeneous cohorts and conservative data analysis, GWAS studies run the risk of type II error, yielding a limitation in our data analysis.9 Furthermore, the data regarding specific time frames in evolutionary skin lightening as well as the intensity of gene polymorphisms are limited.1 Further studies are needed to determine the interconnectedness of the current skin-lightening theories to identify other important factors that may play a role in the process. Determining the key event can help us better understand skin-adaptation mechanisms and create a framework for understanding the vital process involved in adaptation, survival, and disease manifestation in different patient populations.

- Beleza S, Santos AM, McEvoy B, et al. The timing of pigmentation lightening in Europeans. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:24-35. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207

- Carlberg C. Nutrigenomics of vitamin D. Nutrients. 2019;11:676. doi:10.3390/nu11030676

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. The roles of vitamin D and cutaneous vitamin D production in human evolution and health. Int J Paleopathol. 2018;23:54-59. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2018.01.005

- Weiss BD. SORT: strength of recommendation taxonomy. Fam Med. 2004;36:141-143.

- Wolf ST, Kenney WL. The vitamin D–folate hypothesis in human vascular health. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiology. 2019;317:R491-R501. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00136.2019

- Lucock M, Jones P, Martin C, et al. Photobiology of vitamins. Nutr Rev. 2018;76:512-525. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuy013

- Hochberg Z, Hochberg I. Evolutionary perspective in rickets and vitamin D. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:306. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00306

- Rossberg W, Saternus R, Wagenpfeil S, et al. Human pigmentation, cutaneous vitamin D synthesis and evolution: variants of genes (SNPs) involved in skin pigmentation are associated with 25(OH)D serum concentration. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:1429-1437.

- Saternus R, Pilz S, Gräber S, et al. A closer look at evolution: variants (SNPs) of genes involved in skin pigmentation, including EXOC2, TYR, TYRP1, and DCT, are associated with 25(OH)D serum concentration. Endocrinology. 2015;156:39-47. doi:10.1210/en.2014-1238

- López S, García Ó, Yurrebaso I, et al. The interplay between natural selection and susceptibility to melanoma on allele 374F of SLC45A2 gene in a south European population. PloS One. 2014;9:E104367. doi:1371/journal.pone.0104367

- Lucock M, Yates Z, Martin C, et al. Vitamin D, folate, and potential early lifecycle environmental origin of significant adult phenotypes. Evol Med Public Health. 2014;2014:69-91. doi:10.1093/emph/eou013

- Hudjashov G, Villems R, Kivisild T. Global patterns of diversity and selection in human tyrosinase gene. PloS One. 2013;8:E74307. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074307

- Khan R, Khan BSR. Diet, disease and pigment variation in humans. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75:363-367. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2010.03.033

- Kuan V, Martineau AR, Griffiths CJ, et al. DHCR7 mutations linked to higher vitamin D status allowed early human migration to northern latitudes. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:144. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-144

- Omenn GS. Evolution and public health. Proc National Acad Sci. 2010;107(suppl 1):1702-1709. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906198106

- Yuen AWC, Jablonski NG. Vitamin D: in the evolution of human skin colour. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74:39-44. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2009.08.007

- Vieth R. Weaker bones and white skin as adaptions to improve anthropological “fitness” for northern environments. Osteoporosis Int. 2020;31:617-624. doi:10.1007/s00198-019-05167-4

- Carlberg C. Vitamin D: a micronutrient regulating genes. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25:1740-1746. doi:10.2174/1381612825666190705193227

- Haddadeen C, Lai C, Cho SY, et al. Variants of the melanocortin‐1 receptor: do they matter clinically? Exp Dermatol. 2015;1:5-9. doi:10.1111/exd.12540

- Yao S, Ambrosone CB. Associations between vitamin D deficiency and risk of aggressive breast cancer in African-American women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;136:337-341. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.09.010

- Jablonski N. The evolution of human skin colouration and its relevance to health in the modern world. J Royal Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;42:58-63. doi:10.4997/jrcpe.2012.114

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc National Acad Sci. 2010;107(suppl 2):8962-8968. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914628107

- Hochberg Z, Templeton AR. Evolutionary perspective in skin color, vitamin D and its receptor. Hormones. 2010;9:307-311. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1281

- Jones P, Lucock M, Veysey M, et al. The vitamin D–folate hypothesis as an evolutionary model for skin pigmentation: an update and integration of current ideas. Nutrients. 2018;10:554. doi:10.3390/nu10050554

- Lindqvist PG, Epstein E, Landin-Olsson M, et al. Women with fair phenotypes seem to confer a survival advantage in a low UV milieu. a nested matched case control study. PloS One. 2020;15:E0228582. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228582

- Holick MF. Shedding new light on the role of the sunshine vitamin D for skin health: the lncRNA–skin cancer connection. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:391-392. doi:10.1111/exd.12386

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Epidermal pigmentation in the human lineage is an adaptation to ultraviolet radiation. J Hum Evol. 2013;65:671-675. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.06.004

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. The evolution of skin pigmentation and hair texture in people of African ancestry. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:113-121. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.11.003

- Jablonski NG. The evolution of human skin pigmentation involved the interactions of genetic, environmental, and cultural variables. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021;34:707-7 doi:10.1111/pcmr.12976

- Lucock MD, Jones PR, Veysey M, et al. Biophysical evidence to support and extend the vitamin D‐folate hypothesis as a paradigm for the evolution of human skin pigmentation. Am J Hum Biol. 2022;34:E23667. doi:10.1002/ajhb.23667

- Missaggia BO, Reales G, Cybis GB, et al. Adaptation and co‐adaptation of skin pigmentation and vitamin D genes in native Americans. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020;184:1060-1077. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31873

- Hanel A, Carlberg C. Skin colour and vitamin D: an update. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:864-875. doi:10.1111/exd.14142

- Hanel A, Carlberg C. Vitamin D and evolution: pharmacologic implications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;173:113595. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2019.07.024

- Flegr J, Sýkorová K, Fiala V, et al. Increased 25(OH)D3 level in redheaded people: could redheadedness be an adaptation to temperate climate? Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:598-609. doi:10.1111/exd.14119

- James WPT, Johnson RJ, Speakman JR, et al. Nutrition and its role in human evolution. J Intern Med. 2019;285:533-549. doi:10.1111/joim.12878

- Lucock M, Jones P, Martin C, et al. Vitamin D: beyond metabolism. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20:310-322. doi:10.1177/2156587215580491

- Jarrett P, Scragg R. Evolution, prehistory and vitamin D. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:646. doi:10.3390/ijerph17020646

- Elias PM, Williams ML. Re-appraisal of current theories for thedevelopment and loss of epidermal pigmentation in hominins and modern humans. J Hum Evol. 2013;64:687-692. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.02.003

- Elias PM, Williams ML. Basis for the gain and subsequent dilution of epidermal pigmentation during human evolution: the barrier and metabolic conservation hypotheses revisited. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2016;161:189-207. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23030

- Williams JD, Jacobson EL, Kim H, et al. Water soluble vitamins, clinical research and future application. Subcell Biochem. 2011;56:181-197. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2199-9_10

- Greaves M. Was skin cancer a selective force for black pigmentation in early hominin evolution [published online February 26, 2014]? Proc Biol Sci. 2014;281:20132955. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2955

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266-281. doi:10.1056/nejmra070553

- Bouillon R. Comparative analysis of nutritional guidelines for vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:466-479. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2017.31

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. US Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2014. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/call-to-action-prevent-skin-cancer.pdf

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al, eds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. National Academies Press; 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56070/

The risk for developing skin cancer can be somewhat attributed to variations in skin pigmentation. Historically, lighter skin pigmentation has been observed in populations living in higher latitudes and darker pigmentation in populations near the equator. Although skin pigmentation is a conglomeration of genetic and environmental factors, anthropologic studies have demonstrated an association of human skin lightening with historic human migratory patterns.1 It is postulated that migration to latitudes with less UVB light penetration has resulted in a compensatory natural selection of lighter skin types. Furthermore, the driving force behind this migration-associated skin lightening has remained unclear.1

The need for folate metabolism, vitamin D synthesis, and barrier protection, as well as cultural practices, has been postulated as driving factors for skin pigmentation variation. Synthesis of vitamin D is a UV radiation (UVR)–dependent process and has remained a prominent theoretical driver for the basis of evolutionary skin lightening. Vitamin D can be acquired both exogenously or endogenously via dietary supplementation or sunlight; however, historically it has been obtained through UVB exposure primarily. Once UVB is absorbed by the skin, it catalyzes conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which is converted to vitamin D in the kidneys.2,3 It is suggested that lighter skin tones have an advantage over darker skin tones in synthesizing vitamin D at higher latitudes where there is less UVB, thus leading to the adaptation process.1 In this systematic review, we analyzed the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis and assessed the validity of evidence supporting this theory in the literature.

Methods

A search of PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Reviews database was conducted using the terms evolution, vitamin D, and skin to generate articles published from 2010 to 2022 that evaluated the influence of UVR-dependent production of vitamin D on skin pigmentation through historical migration patterns (Figure). Studies were excluded during an initial screening of abstracts followed by full-text assessment if they only had abstracts and if articles were inaccessible for review or in the form of case reports and commentaries.

The following data were extracted from each included study: reference citation, affiliated institutions of authors, author specialties, journal name, year of publication, study period, type of article, type of study, mechanism of adaptation, data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver, and data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver. Data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver were recorded from statistically significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotations. Data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver also were recorded from significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotes. The mechanism of adaptation was based on vitamin D synthesis modulation, melanin upregulation, genetic selections, genetic drift, mating patterns, increased vitamin D sensitivity, interbreeding, and diet.

Studies included in the analysis were placed into 1 of 3 categories: supporting, neutral, and against. Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) criteria were used to classify the level of evidence of each article.4 Each article’s level of evidence was then graded (Table 1). The SORT grading levels were based on quality and evidence type: level 1 signified good-quality, patient-oriented evidence; level 2 signified limited-quality, patient-oriented evidence; and level 3 signified other evidence.4

Results

Article Selection—A total of 229 articles were identified for screening, and 39 studies met inclusion criteria.1-3,5-40 Systematic and retrospective reviews were the most common types of studies. Genomic analysis/sequencing/genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were the most common methods of analysis. Of these 39 articles, 26 were classified as supporting the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis, 10 were classified as neutral, and 3 were classified as against (Table 1).

Of the articles classified as supporting the vitamin D hypothesis, 13 articles were level 1 evidence, 9 were level 2, and 4 were level 3. Key findings supporting the vitamin D hypothesis included genetic natural selection favoring vitamin D synthesis genes at higher latitudes with lower UVR and the skin lightening that occurred to protect against vitamin D deficiency (Table 1). Specific genes supporting these findings included 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7), vitamin D receptor (VDR), tyrosinase (TYR), tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1), oculocutaneous albinism type 2 melanosomal transmembrane protein (OCA2), solute carrier family 45 member 2 (SLC45A2), solute carrier family 4 member 5 (SLC24A5), Kit ligand (KITLG), melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), and HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 (HERC2)(Table 2).

Of the articles classified as being against the vitamin D hypothesis, 1 article was level 1 evidence, 1 was level 2, and 1 was level 3. Key findings refuting the vitamin D hypothesis included similar amounts of vitamin D synthesis in contemporary dark- and light-pigmented individuals, vitamin D–rich diets in the late Paleolithic period and in early agriculturalists, and metabolic conservation being the primary driver (Table 1).

Of the articles classified as neutral to the hypothesis, 7 articles were level 1 evidence and 3 were level 2. Key findings of these articles included genetic selection favoring vitamin D synthesis only for populations at extremely northern latitudes, skin lightening that was sustained in northern latitudes from the neighboring human ancestor the chimpanzee, and evidence for long-term evolutionary pressures and short-term plastic adaptations in vitamin D genes (Table 1).

Comment

The importance of appropriate vitamin D levels is hypothesized as a potent driver in skin lightening because the vitamin is essential for many biochemical processes within the human body. Proper calcification of bones requires activated vitamin D to prevent rickets in childhood. Pelvic deformation in women with rickets can obstruct childbirth in primitive medical environments.15 This direct reproductive impairment suggests a strong selective pressure for skin lightening in populations that migrated northward to enhance vitamin D synthesis.

Of the 39 articles that we reviewed, the majority (n=26 [66.7%]) supported the hypothesis that vitamin D synthesis was the main driver behind skin lightening, whereas 3 (7.7%) did not support the hypothesis and 10 (25.6%) were neutral. Other leading theories explaining skin lightening included the idea that enhanced melanogenesis protected against folate degradation; genetic selection for light-skin alleles due to genetic drift; skin lightening being the result of sexual selection; and a combination of factors, including dietary choices, clothing preferences, and skin permeability barriers.

Articles With Supporting Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—As Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa, migration patterns demonstrated the correlation between distance from the equator and skin pigmentation from natural selection. Individuals with darker skin pigment required higher levels of UVR to synthesize vitamin D. According to Beleza et al,1 as humans migrated to areas of higher latitudes with lower levels of UVR, natural selection favored the development of lighter skin to maximize vitamin D production. Vitamin D is linked to calcium metabolism, and its deficiency can lead to bone malformations and poor immune function.35 Several genes affecting melanogenesis and skin pigment have been found to have geospatial patterns that map to different geographic locations of various populations, indicating how human migration patterns out of Africa created this natural selection for skin lightening. The gene KITLG—associated with lighter skin pigmentation—has been found in high frequencies in both European and East Asian populations and is proposed to have increased in frequency after the migration out of Africa. However, the genes TYRP1, SLC24A5, and SLC45A2 were found at high frequencies only in European populations, and this selection occurred 11,000 to 19,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum (15,000–20,000 years ago), demonstrating the selection for European over East Asian characteristics. During this period, seasonal changes increased the risk for vitamin D deficiency and provided an urgency for selection to a lighter skin pigment.1

The migration of H sapiens to northern latitudes prompted the selection of alleles that would increasevitamin D synthesis to counteract the reduced UV exposure. Genetic analysis studies have found key associations between genes encoding for the metabolism of vitamin D and pigmentation. Among this complex network are the essential downstream enzymes in the melanocortin receptor 1 pathway, including TYR and TYRP1. Forty-six of 960 single-nucleotide polymorphisms located in 29 different genes involved in skin pigmentation that were analyzed in a cohort of 2970 individuals were significantly associated with serum vitamin D levels (P<.05). The exocyst complex component 2 (EXOC2), TYR, and TYRP1 gene variants were shown to have the greatest influence on vitamin D status.9 These data reveal how pigment genotypes are predictive of vitamin D levels and the epistatic potential among many genes in this complex network.

Gene variation plays an important role in vitamin D status when comparing genetic polymorphisms in populations in northern latitudes to African populations. Vitamin D3 precursor availability is decreased by 7-DHCR catalyzing the precursors substrate to cholesterol. In a study using GWAS, it was found that “variations in DHCR7 may aid vitamin D production by conserving cutaneous 7-DHC levels. A high prevalence of DHCR7 variants were found in European and Northeast Asian populations but not in African populations, suggesting that selection occurred for these DHCR7 mutations in populations who migrated to more northern latitudes.5 Multilocus networks have been established between the VDR promotor and skin color genes (Table 2) that exhibit a strong in-Africa vs out-of-Africa frequency pattern. It also has been shown that genetic variation (suggesting a long-term evolutionary inclination) and epigenetic modification (indicative of short-term exposure) of VDR lends support to the vitamin D hypothesis. As latitude decreases, prevalence of VDR FokI (F allele), BsmI (B allele), ApaI (A allele), and TaqI (T allele) also decreases in a linear manner, linking latitude to VDR polymorphisms. Plasma vitamin D levels and photoperiod of conception—UV exposure during the periconceptional period—also were extrapolative of VDR methylation in a study involving 80 participants, where these 2 factors accounted for 17% of variance in methylation.6

Other noteworthy genes included HERC2, which has implications in the expression of OCA2 (melanocyte-specific transporter protein), and IRF4, which encodes for an important enzyme in folate-dependent melanin production. In an Australian cross-sectional study that analyzed vitamin D and pigmentation gene polymorphisms in conjunction with plasma vitamin D levels, the most notable rate of vitamin D loss occurred in individuals with the darkest pigmentation HERC2 (AA) genotype.31 In contrast, the lightest pigmentation HERC2 (GG) genotypes had increased vitamin D3 photosynthesis. Interestingly, the lightest interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) TT genotype and the darkest HERC2 AA genotype, rendering the greatest folate loss and largest synthesis of vitamin D3, were not seen in combination in any of the participants.30 In addition to HERC2, derived alleles from pigment-associated genes SLC24A5*A and SLC45A2*G demonstrated greater frequencies in Europeans (>90%) compared to Africans and East Asians, where the allelic frequencies were either rare or absent.1 This evidence delineates not only the complexity but also the strong relationship between skin pigmentation, latitude, and vitamin D status. The GWAS also have supported this concept. In comparing European populations to African populations, there was a 4-fold increase in the frequencies of “derived alleles of the vitamin D transport protein (GC, rs3755967), the 25(OH)D3 synthesizing enzyme (CYP2R1, rs10741657), VDR (rs2228570 (commonly known as FokI polymorphism), rs1544410 (Bsm1), and rs731236 (Taq1) and the VDR target genes CYP24A1 (rs17216707), CD14 (rs2569190), and CARD9 (rs4077515).”32

Articles With Evidence Against the Vitamin D Theory—This review analyzed the level of support for the theory that vitamin D was the main driver for skin lightening. Although most articles supported this theory, there were articles that listed other plausible counterarguments. Jablonski and Chaplin3 suggested that humans living in higher latitudes compensated for increased demand of vitamin D by placing cultural importance on a diet of vitamin D–rich foods and thus would not have experienced decreased vitamin D levels, which we hypothesize were the driver for skin lightening. Elias et al39 argued that initial pigment dilution may have instead served to improve metabolic conservation, as the authors found no evidence of rickets—the sequelae of vitamin D deficiency—in pre–industrial age human fossils. Elias and Williams38 proposed that differences in skin pigment are due to a more intact skin permeability barrier as “a requirement for life in a desiccating terrestrial environment,” which is seen in darker skin tones compared to lighter skin tones and thus can survive better in warmer climates with less risk of infections or dehydration.

Articles With Neutral Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—Greaves41 argued against the idea that skin evolved to become lighter to protect against vitamin D deficiency. They proposed that the chimpanzee, which is the human’s most closely related species, had light skin covered by hair, and the loss of this hair led to exposed pale skin that created a need for increased melanin production for protection from UVR. Greaves41 stated that the MC1R gene (associated with darker pigmentation) was selected for in African populations, and those with pale skin retained their original pigment as they migrated to higher latitudes. Further research has demonstrated that the genetic natural selection for skin pigment is a complex process that involves multiple gene variants found throughout cultures across the globe.

Conclusion

Skin pigmentation has continuously evolved alongside humans. Genetic selection for lighter skin coincides with a favorable selection for genes involved in vitamin D synthesis as humans migrated to northern latitudes, which enabled humans to produce adequate levels of exogenous vitamin D in low-UVR areas and in turn promoted survival. Early humans without access to supplementation or foods rich in vitamin D acquired vitamin D primarily through sunlight. In comparison to modern society, where vitamin D supplementation is accessible and human lifespans are prolonged, lighter skin tone is now a risk factor for malignant cancers of the skin rather than being a protective adaptation. Current sun behavior recommendations conclude that the body’s need for vitamin D is satisfied by UV exposure to the arms, legs, hands, and/or face for only 5 to 30 minutes between 10

The hypothesis that skin lightening primarily was driven by the need for vitamin D can only be partially supported by our review. Studies have shown that there is a corresponding complex network of genes that determines skin pigmentation as well as vitamin D synthesis and conservation. However, there is sufficient evidence that skin lightening is multifactorial in nature, and vitamin D alone may not be the sole driver. The information in this review can be used by health care providers to educate patients on sun protection, given the lesser threat of severe vitamin D deficiency in developed communities today that have access to adequate nutrition and supplementation.