User login

Internists blame bureaucracy as top cause of burnout

Reported burnout among internal medicine physicians decreased over the past year based on data from Medscape’s annual survey of burnout and depression among physicians in the United States.

Approximately 80% of male internists and 85% of female internists said that their feelings of burnout and/or depression were driven by their jobs all or most of the time. The job-related stress and burnout come home with them — 76% of respondents overall said that burnout had negatively affected their personal relationships.

Too many bureaucratic tasks such as charting and paperwork were by far the top contributor to burnout, reported by 70% of respondents, with insufficient compensation and lack of respect from employers, colleagues, and staff as relatively distant second and third contributors (40% and 37%, respectively).

In addition, nearly half of the physicians said that their burnout was severe enough that they might leave medicine.

To help manage burnout, more internists reported positive coping strategies such as exercise (51%), talking with friends and family (47%), spending time alone (41%), and sleeping (40%), compared to less healthy strategies such as eating junk food, drinking alcohol, and using nicotine or cannabis products.

When asked what workplace measures would help with burnout, no one strategy rose to the top, but the top three were increased compensation (49%), additional support staff (48%), and more flexible work schedules (45%).

Notably, 62% of internists reported depression they defined as colloquial (feeling down or sad) and 27% described their depression as clinical. However, only 9% said they had sought professional help for depression, and 15% said they had sought help for burnout.

Staying in Practice Despite Burnout

The percentage of physicians across specialties who report depression and burnout worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, said Noel Deep, MD, an internal medicine physician in group practice in Antigo, Wisconsin, in an interview.

Since the pandemic, newer stressors have replaced the pandemic-related stressors, and increasing bureaucratic burdens and paperwork continue to cause more physicians to report burnout, he said.

“If not assessed and addressed, this will lead to attrition in the physician workforce leading to increased burden on other physicians and impact patient access to healthcare,” he added.

The survey findings reflect Dr. Deep’s observations. “When talking to physicians across specialties, I have heard universally from many physicians about their experiences and ongoing struggles with potential burnout and mood-related issues,” he said. “While many of them feel that they are getting to the point of burnout, most of them also stoically continue to provide care to patients because they feel an obligation to them,” he said.

This feeling of obligation to patients is why less than one third of the physicians who consider retiring or leaving medicine because of burnout actually do, he said.

As for measures to reduce burnout, “I personally feel that increasing the compensation will not lead to decreased burnout,” Dr. Deep said. Although more money may provide temporary satisfaction, it will not yield long-term improvement in burnout, he said. “Based on personal experiences and my interactions with physicians, providing them more autonomy and control over their practices ... would contribute to decreasing the burnout,” Dr. Deep emphasized.

What Is to Be Done?

“I would favor having physician leaders in healthcare organizations take the time to talk to physicians [and] provide mentoring programs when new physicians are recruited, with ongoing discussions at operations and governance meetings about physician health and wellness,” Dr. Deep said. Providing frequent updates to physicians about wellness resources and encouraging them to seek out help anonymously through Employee Assistance Programs and other counseling services would be beneficial, he added.

“I would also consider peer mentoring when possible. Employers, healthcare organizations, and other key stakeholders should continue to work toward decreasing the stigma of depression and burnout,” Dr. Deep said.

Employers can help physicians manage and reduce burnout and depression by engaging with them, listening to their concerns, and trying to address them, said Dr. Deep. These actions will increase physicians’ trust in their administrations and promote a positive and healthy work environment, he said. “This will lead to reduced attrition in the workforce, retention of experienced physicians and support staff, and lead to increased patient satisfaction as well.”

The data come from Medscape’s annual report on Physician Burnout & Depression, which included 9226 practicing physicians in the United States across more than 29 specialties.

Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose; he serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Internal Medicine News.

Reported burnout among internal medicine physicians decreased over the past year based on data from Medscape’s annual survey of burnout and depression among physicians in the United States.

Approximately 80% of male internists and 85% of female internists said that their feelings of burnout and/or depression were driven by their jobs all or most of the time. The job-related stress and burnout come home with them — 76% of respondents overall said that burnout had negatively affected their personal relationships.

Too many bureaucratic tasks such as charting and paperwork were by far the top contributor to burnout, reported by 70% of respondents, with insufficient compensation and lack of respect from employers, colleagues, and staff as relatively distant second and third contributors (40% and 37%, respectively).

In addition, nearly half of the physicians said that their burnout was severe enough that they might leave medicine.

To help manage burnout, more internists reported positive coping strategies such as exercise (51%), talking with friends and family (47%), spending time alone (41%), and sleeping (40%), compared to less healthy strategies such as eating junk food, drinking alcohol, and using nicotine or cannabis products.

When asked what workplace measures would help with burnout, no one strategy rose to the top, but the top three were increased compensation (49%), additional support staff (48%), and more flexible work schedules (45%).

Notably, 62% of internists reported depression they defined as colloquial (feeling down or sad) and 27% described their depression as clinical. However, only 9% said they had sought professional help for depression, and 15% said they had sought help for burnout.

Staying in Practice Despite Burnout

The percentage of physicians across specialties who report depression and burnout worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, said Noel Deep, MD, an internal medicine physician in group practice in Antigo, Wisconsin, in an interview.

Since the pandemic, newer stressors have replaced the pandemic-related stressors, and increasing bureaucratic burdens and paperwork continue to cause more physicians to report burnout, he said.

“If not assessed and addressed, this will lead to attrition in the physician workforce leading to increased burden on other physicians and impact patient access to healthcare,” he added.

The survey findings reflect Dr. Deep’s observations. “When talking to physicians across specialties, I have heard universally from many physicians about their experiences and ongoing struggles with potential burnout and mood-related issues,” he said. “While many of them feel that they are getting to the point of burnout, most of them also stoically continue to provide care to patients because they feel an obligation to them,” he said.

This feeling of obligation to patients is why less than one third of the physicians who consider retiring or leaving medicine because of burnout actually do, he said.

As for measures to reduce burnout, “I personally feel that increasing the compensation will not lead to decreased burnout,” Dr. Deep said. Although more money may provide temporary satisfaction, it will not yield long-term improvement in burnout, he said. “Based on personal experiences and my interactions with physicians, providing them more autonomy and control over their practices ... would contribute to decreasing the burnout,” Dr. Deep emphasized.

What Is to Be Done?

“I would favor having physician leaders in healthcare organizations take the time to talk to physicians [and] provide mentoring programs when new physicians are recruited, with ongoing discussions at operations and governance meetings about physician health and wellness,” Dr. Deep said. Providing frequent updates to physicians about wellness resources and encouraging them to seek out help anonymously through Employee Assistance Programs and other counseling services would be beneficial, he added.

“I would also consider peer mentoring when possible. Employers, healthcare organizations, and other key stakeholders should continue to work toward decreasing the stigma of depression and burnout,” Dr. Deep said.

Employers can help physicians manage and reduce burnout and depression by engaging with them, listening to their concerns, and trying to address them, said Dr. Deep. These actions will increase physicians’ trust in their administrations and promote a positive and healthy work environment, he said. “This will lead to reduced attrition in the workforce, retention of experienced physicians and support staff, and lead to increased patient satisfaction as well.”

The data come from Medscape’s annual report on Physician Burnout & Depression, which included 9226 practicing physicians in the United States across more than 29 specialties.

Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose; he serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Internal Medicine News.

Reported burnout among internal medicine physicians decreased over the past year based on data from Medscape’s annual survey of burnout and depression among physicians in the United States.

Approximately 80% of male internists and 85% of female internists said that their feelings of burnout and/or depression were driven by their jobs all or most of the time. The job-related stress and burnout come home with them — 76% of respondents overall said that burnout had negatively affected their personal relationships.

Too many bureaucratic tasks such as charting and paperwork were by far the top contributor to burnout, reported by 70% of respondents, with insufficient compensation and lack of respect from employers, colleagues, and staff as relatively distant second and third contributors (40% and 37%, respectively).

In addition, nearly half of the physicians said that their burnout was severe enough that they might leave medicine.

To help manage burnout, more internists reported positive coping strategies such as exercise (51%), talking with friends and family (47%), spending time alone (41%), and sleeping (40%), compared to less healthy strategies such as eating junk food, drinking alcohol, and using nicotine or cannabis products.

When asked what workplace measures would help with burnout, no one strategy rose to the top, but the top three were increased compensation (49%), additional support staff (48%), and more flexible work schedules (45%).

Notably, 62% of internists reported depression they defined as colloquial (feeling down or sad) and 27% described their depression as clinical. However, only 9% said they had sought professional help for depression, and 15% said they had sought help for burnout.

Staying in Practice Despite Burnout

The percentage of physicians across specialties who report depression and burnout worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, said Noel Deep, MD, an internal medicine physician in group practice in Antigo, Wisconsin, in an interview.

Since the pandemic, newer stressors have replaced the pandemic-related stressors, and increasing bureaucratic burdens and paperwork continue to cause more physicians to report burnout, he said.

“If not assessed and addressed, this will lead to attrition in the physician workforce leading to increased burden on other physicians and impact patient access to healthcare,” he added.

The survey findings reflect Dr. Deep’s observations. “When talking to physicians across specialties, I have heard universally from many physicians about their experiences and ongoing struggles with potential burnout and mood-related issues,” he said. “While many of them feel that they are getting to the point of burnout, most of them also stoically continue to provide care to patients because they feel an obligation to them,” he said.

This feeling of obligation to patients is why less than one third of the physicians who consider retiring or leaving medicine because of burnout actually do, he said.

As for measures to reduce burnout, “I personally feel that increasing the compensation will not lead to decreased burnout,” Dr. Deep said. Although more money may provide temporary satisfaction, it will not yield long-term improvement in burnout, he said. “Based on personal experiences and my interactions with physicians, providing them more autonomy and control over their practices ... would contribute to decreasing the burnout,” Dr. Deep emphasized.

What Is to Be Done?

“I would favor having physician leaders in healthcare organizations take the time to talk to physicians [and] provide mentoring programs when new physicians are recruited, with ongoing discussions at operations and governance meetings about physician health and wellness,” Dr. Deep said. Providing frequent updates to physicians about wellness resources and encouraging them to seek out help anonymously through Employee Assistance Programs and other counseling services would be beneficial, he added.

“I would also consider peer mentoring when possible. Employers, healthcare organizations, and other key stakeholders should continue to work toward decreasing the stigma of depression and burnout,” Dr. Deep said.

Employers can help physicians manage and reduce burnout and depression by engaging with them, listening to their concerns, and trying to address them, said Dr. Deep. These actions will increase physicians’ trust in their administrations and promote a positive and healthy work environment, he said. “This will lead to reduced attrition in the workforce, retention of experienced physicians and support staff, and lead to increased patient satisfaction as well.”

The data come from Medscape’s annual report on Physician Burnout & Depression, which included 9226 practicing physicians in the United States across more than 29 specialties.

Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose; he serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Internal Medicine News.

Progressively Worsening Scaly Patches and Plaques in an Infant

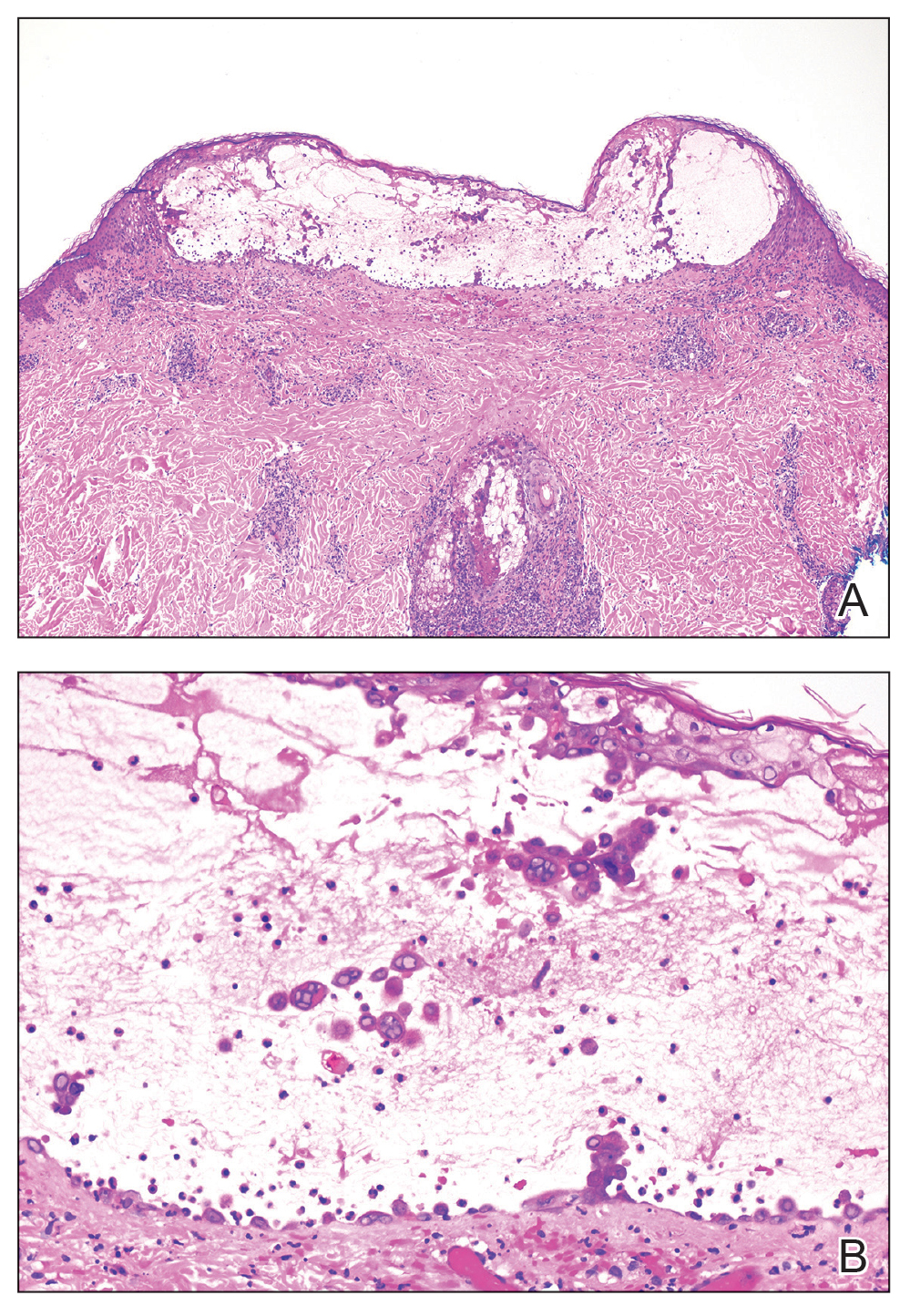

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

A 5-month-old male with moderately brown skin that rarely burns and tans profusely presented to the emergency department with a worsening red rash of more than 4 months’ duration. The patient had diffuse erythroderma and eczematous patches and plaques covering 95% of the total body surface area, including lichenified plaques on the arms and elbows, with no signs of infection. He initially presented for his 1-month appointment at the pediatric clinic with scaly patches and plaques on the face and trunk as well as diffuse xerosis. He was prescribed daily oatmeal baths and topical Minerin (Major Pharmaceuticals)—containing water, petrolatum, mineral oil, mineral wax, lanolin alcohol, methylchloroisothiazolinone, and methylisothiazolinone—to be applied to the whole body twice daily. At the patient’s 2-month well visit, symptoms persisted. The patient’s pediatrician increased application of Minerin to 2 to 3 times daily, and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% application 2 to 3 times daily was added.

Lichenoid Dermatosis on the Feet

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

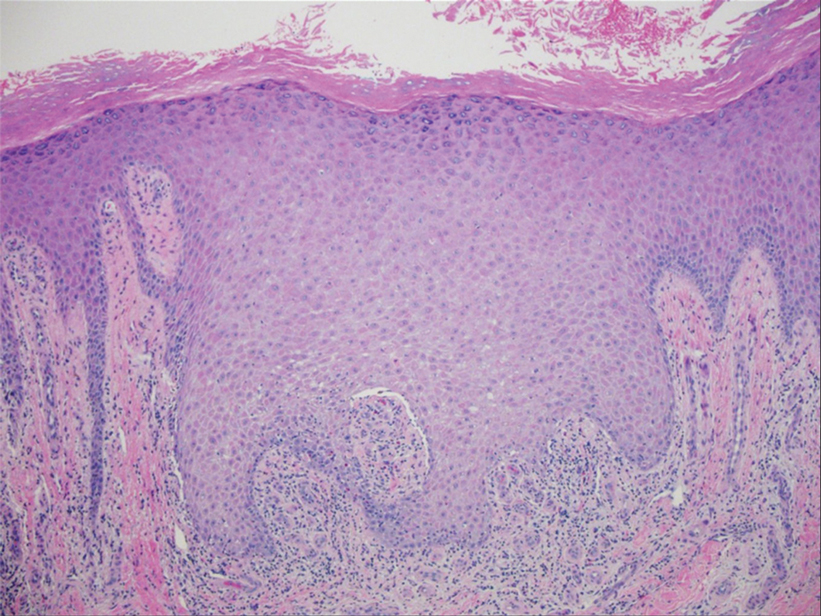

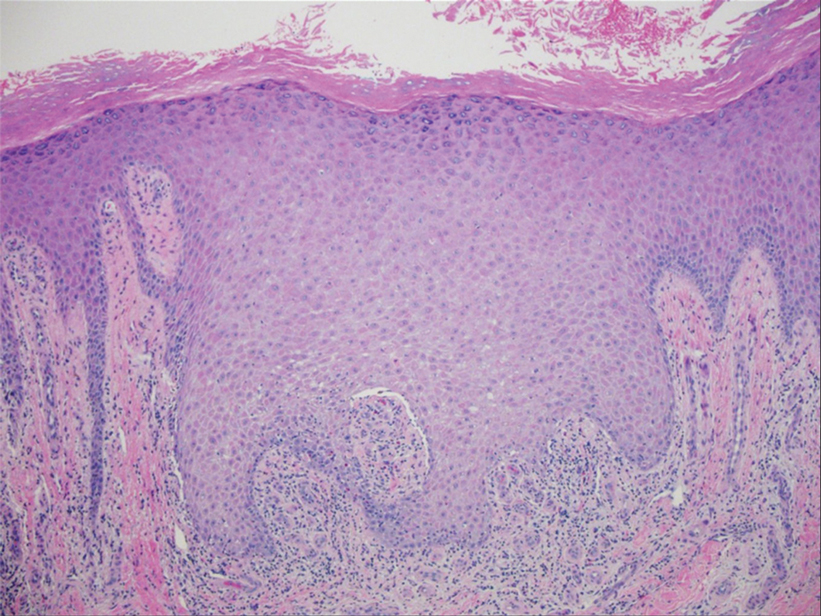

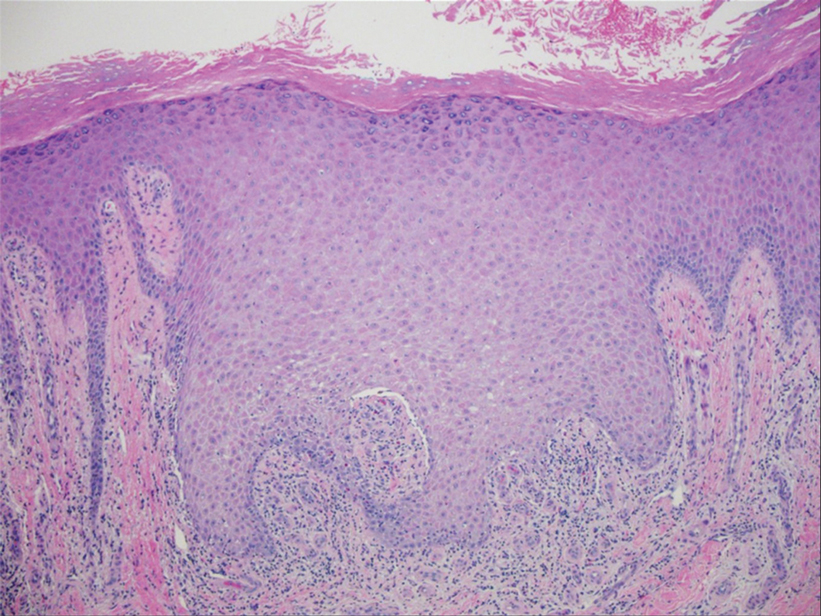

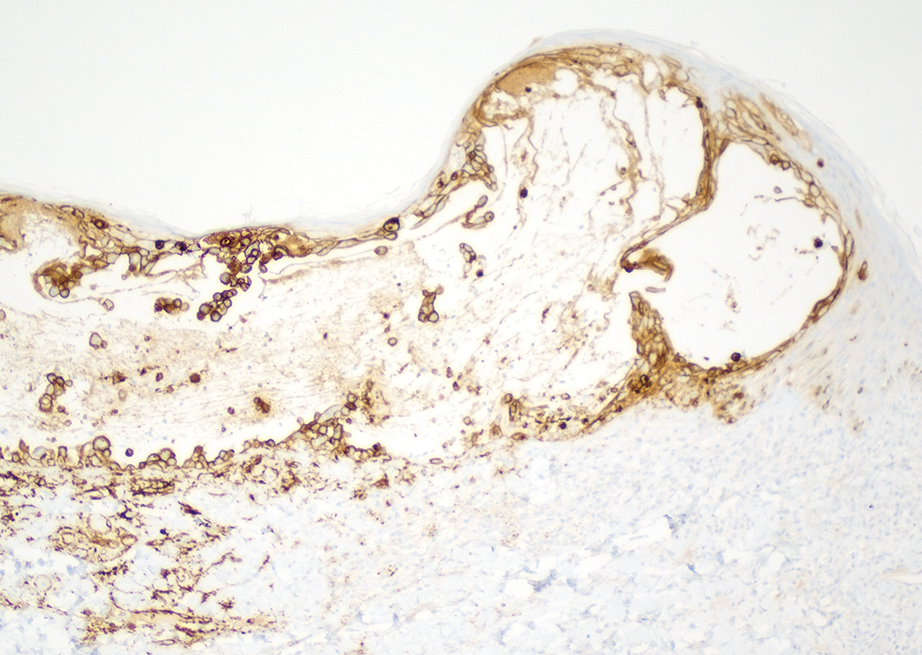

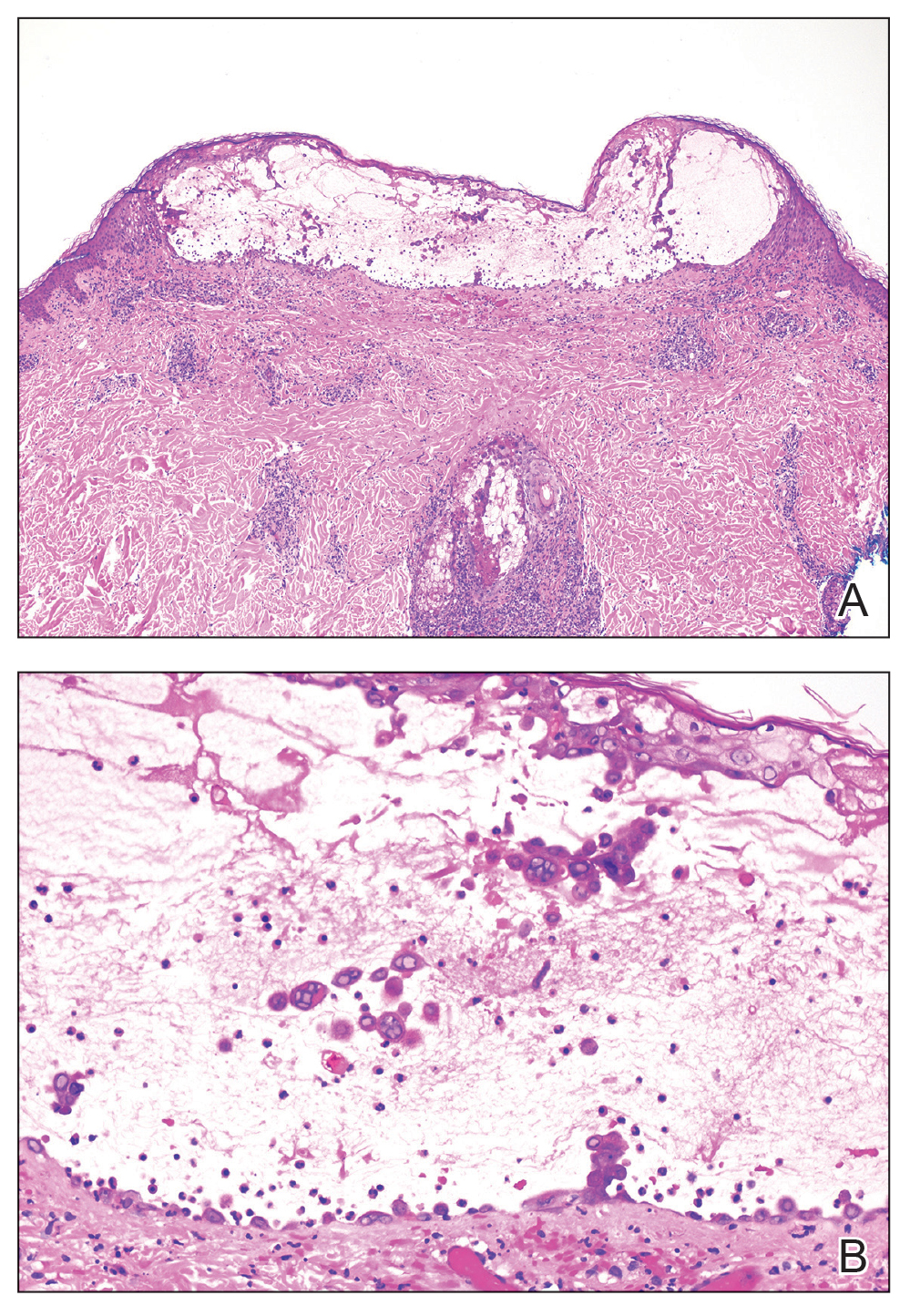

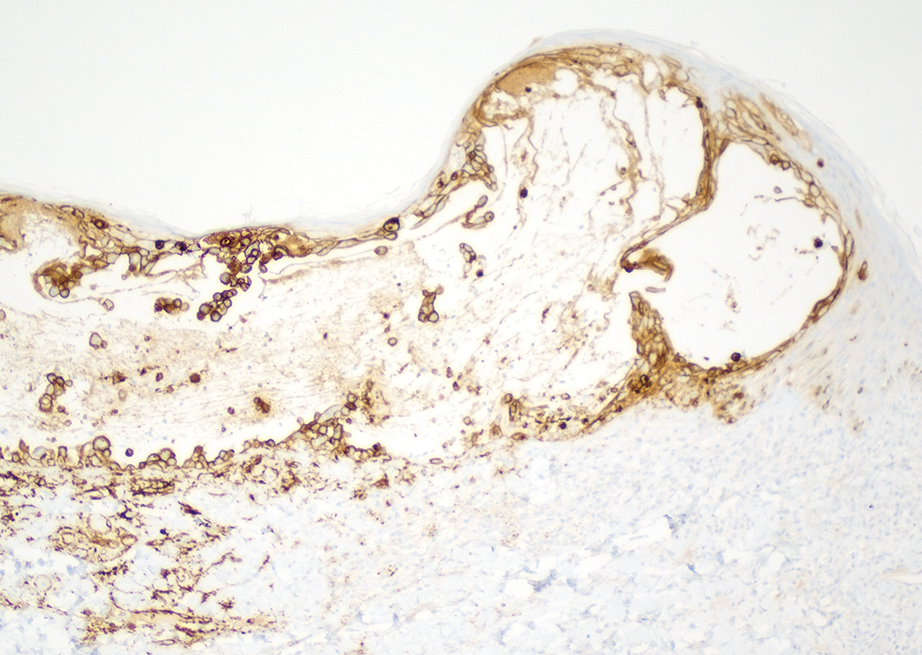

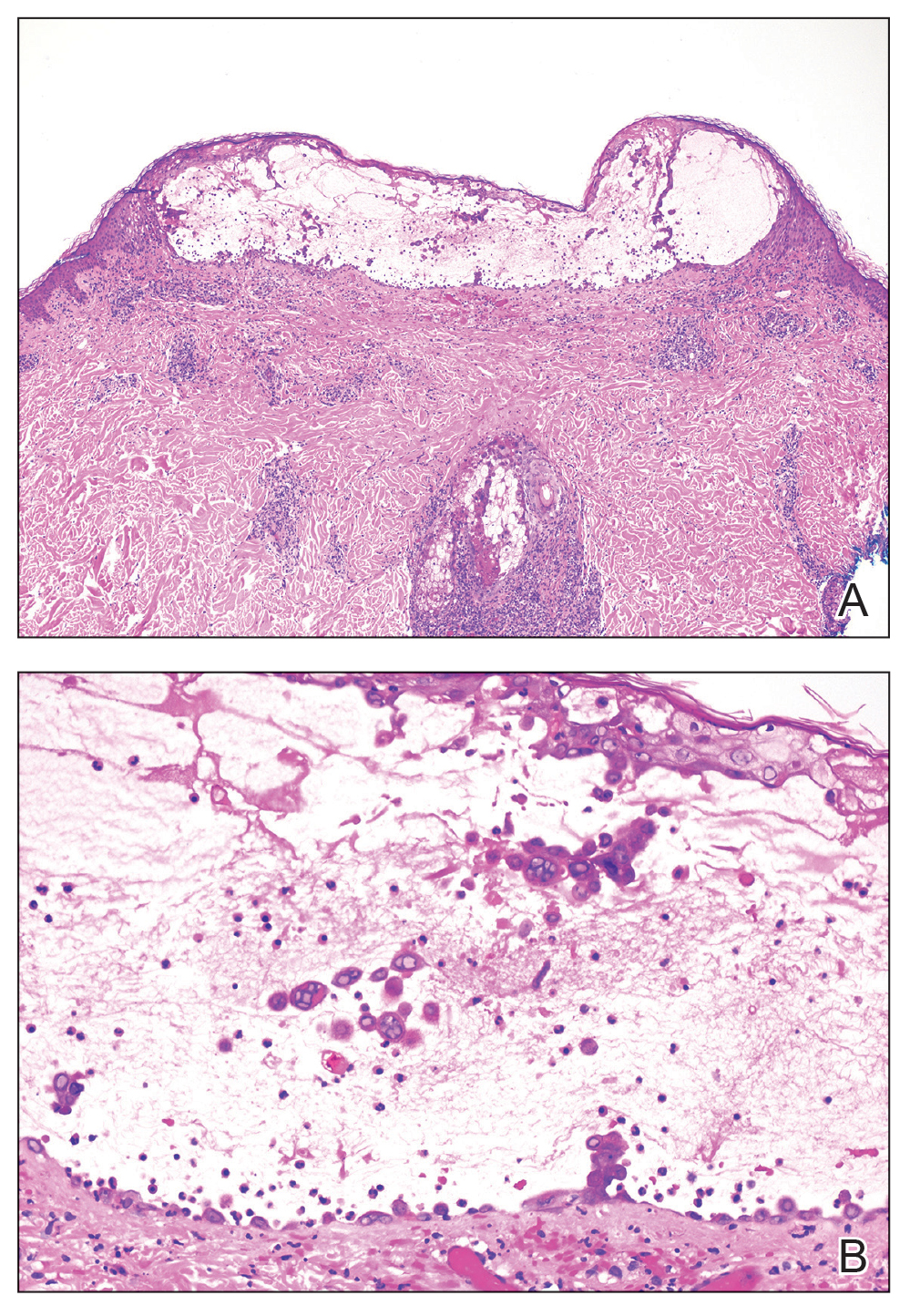

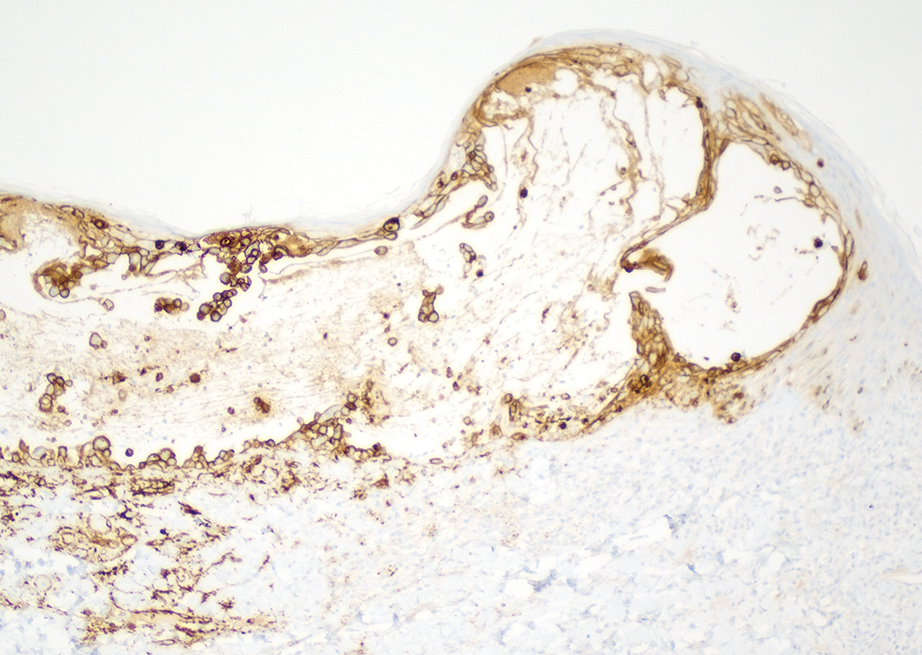

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

An 83-year-old woman presented for evaluation of hyperkeratotic plaques on the medial and lateral aspects of the left heel (top). Physical examination also revealed onychodystrophy of the toenails on the halluces (bottom). A crusted friable plaque on the lower lip and white plaques with peripheral reticulation and erosions on the buccal mucosa also were present. The patient had a history of nummular eczema, stasis dermatitis, and hand dermatitis. She denied a history of cold sores.

Dx Across the Skin Color Spectrum: Longitudinal Melanonychia

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is a pigmented linear band—brown, black, or gray—spanning the length of the nail plate due to the presence of excess melanin, which may be attributed to a benign or malignant process and may warrant further investigation.1,2 The majority of patients who present with LM are diagnosed with melanocytic activation of the nail matrix due to their inherent darker skin tone or various triggers including trauma, infection, and medications. Longitudinal melanonychia secondary to melanocytic activation often occurs spontaneously in patients with skin of color.3 Less commonly, LM is caused by a nail matrix nevus or lentigo; however, LM may arise secondary to subungual melanoma, a more dangerous cause.

A thorough clinical history including duration, recent changes in LM manifestation, nail trauma, or infection is helpful in evaluating patients with LM; however, a history of nail trauma can be misleading, as nail changes attributed to the trauma may in fact be melanoma. Irregularly spaced vertical lines of pigmentation ranging from brown to black with variations in spacing and width are characteristic of subungual melanoma.4 Nail dystrophy, granular hyperpigmentation, and Hutchinson sign (extension of pigmentation to the nail folds) also are worrisome features.5 In recent years, dermoscopy has become an important tool in the clinical examination of LM, with the development of criteria based on color and pattern recognition.5,6 Dermoscopy can be useful in screening potential candidates for biopsy. Although clinical examination and dermoscopy are essential to evaluating LM, the gold-standard diagnostic test when malignancy is suspected is a nail matrix biopsy.1,2,6,7

Epidemiology

It is not unusual for patients with darker skin tones to develop LM due to melanocytic activation of multiple nails with age. This finding can be seen in approximately 80% of African American individuals, 30% of Japanese individuals, and 50% of Hispanic individuals.2 It has even been reported that approximately 100% of Black patients older than 50 years will have evidence of LM.3

In a retrospective analysis, children presenting with LM tend to have a higher prevalence of nail matrix nevi compared to adults (56.1% [60/106] vs 34.3% [23/66]; P =.005).8 Involvement of a single digit in children is most likely indicative of a nevus; however, when an adult presents with LM in a single digit, suspicion for subungual melanoma should be raised.2,3,9

Two separate single-center retrospective studies showed the prevalence of subungual melanoma in patients presenting with melanonychia in Asia. Jin et al10 reported subungual melanoma in 6.2% (17/275) of Korean patients presenting with melanonychia at a general dermatology clinic from 2002 to 2014. Lyu et al8 studied LM in 172 Chinese patients in a dermatology clinic from 2018 to 2021 and reported 9% (6/66) of adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with subungual melanoma, with no reported cases in childhood (aged < 18 years).

Although the prevalence of subungual melanoma in patients with LM is low, it is an important diagnosis that should not be missed. In confirmed cases of subungual melanoma, two-thirds of lesions manifested as LM.3,10,11 Thus, LM arising in an adult in a single digit is more concerning for malignancy.2,3,7,9

Individuals of African and Asian descent as well as American Indian individuals are at highest risk for subungual melanoma with a poor prognosis compared to other types of melanoma, largely due to diagnosis at an advanced stage of disease.3,9 In a retrospective study of 25 patients with surgically treated subungual melanoma, the mean recurrence-free survival was 33.6 months. The recurrence-free survival was 66% at 1 year and 40% at 3 years, and the overall survival rate was 37% at 3 years.12

Key clinical features in individuals with darker skin tones

• In patients with darker skin tones, LM tends to occur on multiple nails as a result of melanocytic activation.2,13

• Several longitudinal bands may be noted on the same nail and the pigmentation of the bands may vary. With age, these longitudinal bands typically increase in number and width.13

• Pseudo-Hutchinson sign may be present due to ethnic melanosis of the proximal nail fold.13,14

• Dermoscopic findings of LM in patients with skin of color include wider bands (P = .0125), lower band brightness (P < .032), and higher frequency of changing appearance of bands (P = .0071).15

Worth noting

When patients present with LM, thorough examination of the nail plate, periungual skin, and distal pulp of all digits on all extremities with adequate lighting is important.2 Dermoscopy is useful, and a gel interface helps for examining the nail plates.7

Clinicians should be encouraged to biopsy or immediately refer patients with concerning nail unit lesions. Cases of LM most likely are benign, but if some doubt exists, the lesions should be biopsied or tracked closely with clinical and dermoscopic images, with a biopsy if changes occur.16 In conjunction with evaluation by a qualified clinician, patients also should be encouraged to take photographs, as the evolution of nail changes is a critical part of clinical decision-making on the need for a biopsy or referral.

Health disparity highlight

Despite the disproportionately high mortality rates from subungual melanoma in Black and Hispanic populations,3,9 studies often do not adequately represent these populations. Although subungual melanoma is rare, a delay in the diagnosis contributes to high morbidity and mortality rates.

1. Tosti A, Piraccini BM, de Farias DC. Dealing with melanonychia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:49-54. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.004

2. Piraccini BM, Dika E, Fanti PA. Tips for diagnosis and treatment of nail pigmentation with practical algorithm. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:185-195. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.12.002

3. Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. Assessment of patient knowledge of longitudinal melanonychia: a survey study of patients in outpatient clinics. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2:156-161. doi:10.1159/000452673

4. Singal A, Bisherwal K. Melanonychia: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Indian Dermatol J Online. 2020;11:1-11. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_167_19

5. Benati E, Ribero S, Longo C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic clues to differentiate pigmented nail bands: an International Dermoscopy Society study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:732-736. doi:10.1111/jdv.13991

6. Sawada M, Yokota K, Matsumoto T, et al. Proposed classification of longitudinal melanonychia based on clinical and dermoscopic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:581-585. doi:10.1111/ijd.12001

7. Starace M, Alessandrini A, Brandi N, et al. Use of nail dermoscopy in the management of melanonychia. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9:38-43. doi:10.5826/dpc.0901a10

8. Lyu A, Hou Y, Wang Q. Retrospective analysis of longitudinal melanonychia: a Chinese experience. Front Pediatr. 2023;10:1065758. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.1065758

9. Williams NM, Obayomi AO, Diaz-Perez, JA, et al. Monodactylous longitudinal melanonychia: a sign of Bowen’s disease in skin of color. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:306-310. doi:10.1159/000514221

10. Jin H, Kim JM, Kim GW, et al. Diagnostic criteria for and clinical review of melanonychia in Korean patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74,1121-1127. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.039

11. Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.053

12. LaRocca CJ, Lai L, Nelson RA, et al. Subungual melanoma: a single institution experience. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9:57. doi:10.3390/medsci9030057

13. Baran LR, Ruben BS, Kechijian P, et al. Non‐melanoma Hutchinson’s sign: a reappraisal of this important, remarkable melanoma simulant. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:495-501. doi:10.1111/jdv.14715

14. Sladden MJ, Mortimer NJ, Osborne JE. Longitudinal melanonychia and pseudo‐Hutchinson sign associated with amlodipine. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:219-220. doi:10.1111/j.13652133.2005.06668.x

15. Lee DK, Chang MJ, Desai AD, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic findings of benign longitudinal melanonychia due to melanocytic activation differ by skin type and predict likelihood of nail matrix biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:792-799. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1165

16. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is a pigmented linear band—brown, black, or gray—spanning the length of the nail plate due to the presence of excess melanin, which may be attributed to a benign or malignant process and may warrant further investigation.1,2 The majority of patients who present with LM are diagnosed with melanocytic activation of the nail matrix due to their inherent darker skin tone or various triggers including trauma, infection, and medications. Longitudinal melanonychia secondary to melanocytic activation often occurs spontaneously in patients with skin of color.3 Less commonly, LM is caused by a nail matrix nevus or lentigo; however, LM may arise secondary to subungual melanoma, a more dangerous cause.

A thorough clinical history including duration, recent changes in LM manifestation, nail trauma, or infection is helpful in evaluating patients with LM; however, a history of nail trauma can be misleading, as nail changes attributed to the trauma may in fact be melanoma. Irregularly spaced vertical lines of pigmentation ranging from brown to black with variations in spacing and width are characteristic of subungual melanoma.4 Nail dystrophy, granular hyperpigmentation, and Hutchinson sign (extension of pigmentation to the nail folds) also are worrisome features.5 In recent years, dermoscopy has become an important tool in the clinical examination of LM, with the development of criteria based on color and pattern recognition.5,6 Dermoscopy can be useful in screening potential candidates for biopsy. Although clinical examination and dermoscopy are essential to evaluating LM, the gold-standard diagnostic test when malignancy is suspected is a nail matrix biopsy.1,2,6,7

Epidemiology

It is not unusual for patients with darker skin tones to develop LM due to melanocytic activation of multiple nails with age. This finding can be seen in approximately 80% of African American individuals, 30% of Japanese individuals, and 50% of Hispanic individuals.2 It has even been reported that approximately 100% of Black patients older than 50 years will have evidence of LM.3

In a retrospective analysis, children presenting with LM tend to have a higher prevalence of nail matrix nevi compared to adults (56.1% [60/106] vs 34.3% [23/66]; P =.005).8 Involvement of a single digit in children is most likely indicative of a nevus; however, when an adult presents with LM in a single digit, suspicion for subungual melanoma should be raised.2,3,9

Two separate single-center retrospective studies showed the prevalence of subungual melanoma in patients presenting with melanonychia in Asia. Jin et al10 reported subungual melanoma in 6.2% (17/275) of Korean patients presenting with melanonychia at a general dermatology clinic from 2002 to 2014. Lyu et al8 studied LM in 172 Chinese patients in a dermatology clinic from 2018 to 2021 and reported 9% (6/66) of adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with subungual melanoma, with no reported cases in childhood (aged < 18 years).

Although the prevalence of subungual melanoma in patients with LM is low, it is an important diagnosis that should not be missed. In confirmed cases of subungual melanoma, two-thirds of lesions manifested as LM.3,10,11 Thus, LM arising in an adult in a single digit is more concerning for malignancy.2,3,7,9

Individuals of African and Asian descent as well as American Indian individuals are at highest risk for subungual melanoma with a poor prognosis compared to other types of melanoma, largely due to diagnosis at an advanced stage of disease.3,9 In a retrospective study of 25 patients with surgically treated subungual melanoma, the mean recurrence-free survival was 33.6 months. The recurrence-free survival was 66% at 1 year and 40% at 3 years, and the overall survival rate was 37% at 3 years.12

Key clinical features in individuals with darker skin tones

• In patients with darker skin tones, LM tends to occur on multiple nails as a result of melanocytic activation.2,13

• Several longitudinal bands may be noted on the same nail and the pigmentation of the bands may vary. With age, these longitudinal bands typically increase in number and width.13

• Pseudo-Hutchinson sign may be present due to ethnic melanosis of the proximal nail fold.13,14

• Dermoscopic findings of LM in patients with skin of color include wider bands (P = .0125), lower band brightness (P < .032), and higher frequency of changing appearance of bands (P = .0071).15

Worth noting

When patients present with LM, thorough examination of the nail plate, periungual skin, and distal pulp of all digits on all extremities with adequate lighting is important.2 Dermoscopy is useful, and a gel interface helps for examining the nail plates.7

Clinicians should be encouraged to biopsy or immediately refer patients with concerning nail unit lesions. Cases of LM most likely are benign, but if some doubt exists, the lesions should be biopsied or tracked closely with clinical and dermoscopic images, with a biopsy if changes occur.16 In conjunction with evaluation by a qualified clinician, patients also should be encouraged to take photographs, as the evolution of nail changes is a critical part of clinical decision-making on the need for a biopsy or referral.

Health disparity highlight

Despite the disproportionately high mortality rates from subungual melanoma in Black and Hispanic populations,3,9 studies often do not adequately represent these populations. Although subungual melanoma is rare, a delay in the diagnosis contributes to high morbidity and mortality rates.

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is a pigmented linear band—brown, black, or gray—spanning the length of the nail plate due to the presence of excess melanin, which may be attributed to a benign or malignant process and may warrant further investigation.1,2 The majority of patients who present with LM are diagnosed with melanocytic activation of the nail matrix due to their inherent darker skin tone or various triggers including trauma, infection, and medications. Longitudinal melanonychia secondary to melanocytic activation often occurs spontaneously in patients with skin of color.3 Less commonly, LM is caused by a nail matrix nevus or lentigo; however, LM may arise secondary to subungual melanoma, a more dangerous cause.

A thorough clinical history including duration, recent changes in LM manifestation, nail trauma, or infection is helpful in evaluating patients with LM; however, a history of nail trauma can be misleading, as nail changes attributed to the trauma may in fact be melanoma. Irregularly spaced vertical lines of pigmentation ranging from brown to black with variations in spacing and width are characteristic of subungual melanoma.4 Nail dystrophy, granular hyperpigmentation, and Hutchinson sign (extension of pigmentation to the nail folds) also are worrisome features.5 In recent years, dermoscopy has become an important tool in the clinical examination of LM, with the development of criteria based on color and pattern recognition.5,6 Dermoscopy can be useful in screening potential candidates for biopsy. Although clinical examination and dermoscopy are essential to evaluating LM, the gold-standard diagnostic test when malignancy is suspected is a nail matrix biopsy.1,2,6,7

Epidemiology

It is not unusual for patients with darker skin tones to develop LM due to melanocytic activation of multiple nails with age. This finding can be seen in approximately 80% of African American individuals, 30% of Japanese individuals, and 50% of Hispanic individuals.2 It has even been reported that approximately 100% of Black patients older than 50 years will have evidence of LM.3

In a retrospective analysis, children presenting with LM tend to have a higher prevalence of nail matrix nevi compared to adults (56.1% [60/106] vs 34.3% [23/66]; P =.005).8 Involvement of a single digit in children is most likely indicative of a nevus; however, when an adult presents with LM in a single digit, suspicion for subungual melanoma should be raised.2,3,9

Two separate single-center retrospective studies showed the prevalence of subungual melanoma in patients presenting with melanonychia in Asia. Jin et al10 reported subungual melanoma in 6.2% (17/275) of Korean patients presenting with melanonychia at a general dermatology clinic from 2002 to 2014. Lyu et al8 studied LM in 172 Chinese patients in a dermatology clinic from 2018 to 2021 and reported 9% (6/66) of adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with subungual melanoma, with no reported cases in childhood (aged < 18 years).

Although the prevalence of subungual melanoma in patients with LM is low, it is an important diagnosis that should not be missed. In confirmed cases of subungual melanoma, two-thirds of lesions manifested as LM.3,10,11 Thus, LM arising in an adult in a single digit is more concerning for malignancy.2,3,7,9

Individuals of African and Asian descent as well as American Indian individuals are at highest risk for subungual melanoma with a poor prognosis compared to other types of melanoma, largely due to diagnosis at an advanced stage of disease.3,9 In a retrospective study of 25 patients with surgically treated subungual melanoma, the mean recurrence-free survival was 33.6 months. The recurrence-free survival was 66% at 1 year and 40% at 3 years, and the overall survival rate was 37% at 3 years.12

Key clinical features in individuals with darker skin tones

• In patients with darker skin tones, LM tends to occur on multiple nails as a result of melanocytic activation.2,13

• Several longitudinal bands may be noted on the same nail and the pigmentation of the bands may vary. With age, these longitudinal bands typically increase in number and width.13

• Pseudo-Hutchinson sign may be present due to ethnic melanosis of the proximal nail fold.13,14

• Dermoscopic findings of LM in patients with skin of color include wider bands (P = .0125), lower band brightness (P < .032), and higher frequency of changing appearance of bands (P = .0071).15

Worth noting

When patients present with LM, thorough examination of the nail plate, periungual skin, and distal pulp of all digits on all extremities with adequate lighting is important.2 Dermoscopy is useful, and a gel interface helps for examining the nail plates.7

Clinicians should be encouraged to biopsy or immediately refer patients with concerning nail unit lesions. Cases of LM most likely are benign, but if some doubt exists, the lesions should be biopsied or tracked closely with clinical and dermoscopic images, with a biopsy if changes occur.16 In conjunction with evaluation by a qualified clinician, patients also should be encouraged to take photographs, as the evolution of nail changes is a critical part of clinical decision-making on the need for a biopsy or referral.

Health disparity highlight

Despite the disproportionately high mortality rates from subungual melanoma in Black and Hispanic populations,3,9 studies often do not adequately represent these populations. Although subungual melanoma is rare, a delay in the diagnosis contributes to high morbidity and mortality rates.

1. Tosti A, Piraccini BM, de Farias DC. Dealing with melanonychia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:49-54. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.004

2. Piraccini BM, Dika E, Fanti PA. Tips for diagnosis and treatment of nail pigmentation with practical algorithm. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:185-195. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.12.002

3. Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. Assessment of patient knowledge of longitudinal melanonychia: a survey study of patients in outpatient clinics. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2:156-161. doi:10.1159/000452673

4. Singal A, Bisherwal K. Melanonychia: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Indian Dermatol J Online. 2020;11:1-11. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_167_19

5. Benati E, Ribero S, Longo C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic clues to differentiate pigmented nail bands: an International Dermoscopy Society study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:732-736. doi:10.1111/jdv.13991

6. Sawada M, Yokota K, Matsumoto T, et al. Proposed classification of longitudinal melanonychia based on clinical and dermoscopic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:581-585. doi:10.1111/ijd.12001

7. Starace M, Alessandrini A, Brandi N, et al. Use of nail dermoscopy in the management of melanonychia. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9:38-43. doi:10.5826/dpc.0901a10

8. Lyu A, Hou Y, Wang Q. Retrospective analysis of longitudinal melanonychia: a Chinese experience. Front Pediatr. 2023;10:1065758. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.1065758

9. Williams NM, Obayomi AO, Diaz-Perez, JA, et al. Monodactylous longitudinal melanonychia: a sign of Bowen’s disease in skin of color. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:306-310. doi:10.1159/000514221

10. Jin H, Kim JM, Kim GW, et al. Diagnostic criteria for and clinical review of melanonychia in Korean patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74,1121-1127. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.039

11. Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.053

12. LaRocca CJ, Lai L, Nelson RA, et al. Subungual melanoma: a single institution experience. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9:57. doi:10.3390/medsci9030057

13. Baran LR, Ruben BS, Kechijian P, et al. Non‐melanoma Hutchinson’s sign: a reappraisal of this important, remarkable melanoma simulant. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:495-501. doi:10.1111/jdv.14715

14. Sladden MJ, Mortimer NJ, Osborne JE. Longitudinal melanonychia and pseudo‐Hutchinson sign associated with amlodipine. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:219-220. doi:10.1111/j.13652133.2005.06668.x

15. Lee DK, Chang MJ, Desai AD, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic findings of benign longitudinal melanonychia due to melanocytic activation differ by skin type and predict likelihood of nail matrix biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:792-799. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1165

16. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

1. Tosti A, Piraccini BM, de Farias DC. Dealing with melanonychia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:49-54. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.004

2. Piraccini BM, Dika E, Fanti PA. Tips for diagnosis and treatment of nail pigmentation with practical algorithm. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:185-195. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.12.002

3. Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. Assessment of patient knowledge of longitudinal melanonychia: a survey study of patients in outpatient clinics. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2:156-161. doi:10.1159/000452673

4. Singal A, Bisherwal K. Melanonychia: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Indian Dermatol J Online. 2020;11:1-11. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_167_19

5. Benati E, Ribero S, Longo C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic clues to differentiate pigmented nail bands: an International Dermoscopy Society study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:732-736. doi:10.1111/jdv.13991

6. Sawada M, Yokota K, Matsumoto T, et al. Proposed classification of longitudinal melanonychia based on clinical and dermoscopic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:581-585. doi:10.1111/ijd.12001

7. Starace M, Alessandrini A, Brandi N, et al. Use of nail dermoscopy in the management of melanonychia. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9:38-43. doi:10.5826/dpc.0901a10

8. Lyu A, Hou Y, Wang Q. Retrospective analysis of longitudinal melanonychia: a Chinese experience. Front Pediatr. 2023;10:1065758. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.1065758

9. Williams NM, Obayomi AO, Diaz-Perez, JA, et al. Monodactylous longitudinal melanonychia: a sign of Bowen’s disease in skin of color. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:306-310. doi:10.1159/000514221

10. Jin H, Kim JM, Kim GW, et al. Diagnostic criteria for and clinical review of melanonychia in Korean patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74,1121-1127. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.039

11. Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.053

12. LaRocca CJ, Lai L, Nelson RA, et al. Subungual melanoma: a single institution experience. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9:57. doi:10.3390/medsci9030057

13. Baran LR, Ruben BS, Kechijian P, et al. Non‐melanoma Hutchinson’s sign: a reappraisal of this important, remarkable melanoma simulant. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:495-501. doi:10.1111/jdv.14715

14. Sladden MJ, Mortimer NJ, Osborne JE. Longitudinal melanonychia and pseudo‐Hutchinson sign associated with amlodipine. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:219-220. doi:10.1111/j.13652133.2005.06668.x

15. Lee DK, Chang MJ, Desai AD, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic findings of benign longitudinal melanonychia due to melanocytic activation differ by skin type and predict likelihood of nail matrix biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:792-799. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1165

16. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

Trauma, Racism Linked to Increased Suicide Risk in Black Men

One in three Black men in rural America experienced suicidal or death ideation (SDI) in the past week, new research showed.