User login

Some measures to control HAI sound better than they perform

SAN DIEGO – Some almost universally accepted measures against hospital-acquired infections are more costly, annoying, and time consuming than they’re worth, presenters agreed during a panel discussion at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Intra-abdominal antibiotic irrigation, chlorhexidine bathing, and even postsurgical antibiotic infusions have not consistently been shown to reduce infections. These measures do, however, ratchet up costs and can contribute to antibiotic resistance.

Some of these and other measures to prevent nosocomial infections may indeed reduce the risk, but the gain is small, said Charles H. Cook, MD.

“Chlorhexidine bathing, for example, is touted by many as a panacea for all the infections we’re talking about,” said Dr. Cook, a critical care surgeon at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, New York. “A recent meta-analysis in critical care units did find a reduced relative risk of 0.44 for central line bloodstream infections. But you needed to bathe 360 patients to prevent one infection. It’s what I call a long run for a short slide.”

Therese Duane, MD, FACS, agreed. A surgeon at the John Peter Smith Hospital, Ft. Worth, Tex., Dr. Duane reviewed three different guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infections: the ACS and Surgical Infection Society, the World Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In looking for similarities between the documents, she said she found several well-accepted practices that just aren’t supported by good data.

Presurgical antimicrobial infusions got a strong thumbs-up from all the groups, but only under a very specific circumstance: The medication has to be administered well in advance of surgery for it to be effective.

“Your goal is to get the appropriate concentration into the tissues by the time of incision,” Dr. Duane said. “It takes time to get there – if you give it after the incision, you have bleeding and cellular death, and the antimicrobials cannot get to that incision and do their job. If I’m starting a case and they haven’t been given, I don’t ever start them after the incision, because then you have all of the risks and none of the benefits. In my opinion, we need to move to no further antimicrobials once the incision or case is over because it serves no purpose and is inconsistent with good antibiotic stewardship.”

Adhesive drapes got a resounding “eh” from the guidelines, Dr. Duane said. “You really do not need them. They’re expensive and they’re not improving outcomes, so don’t waste your time or money. We need to think about minimizing what isn’t helpful and maximizing the things that are worthwhile. That’s the way to practice good socially responsible surgery without breaking the bank,” she said.

Antimicrobial sutures got weak recommendations, Dr. Duane said. The evidence supporting their use was not very strong, although she said she feels triclosan-coated sutures are helpful in all kinds of surgery. Preoperative showering with an antiseptic received strong support, with alcohol-containing preps superior to chlorhexidine, which is better than povidone-iodine–containing solutions.

Deep-space irrigation with aqueous iodophor also received a weak recommendation, but Dr. Duane said the evidence does not support the use of antibiotic-containing irrigation in either the abdomen or the incision. “And the guidelines came out strongly against using antimicrobial agents on the incision,” she said. None of the guidelines issued a recommendation for or against antimicrobial dressings.

Protocolized infection-control bundles are a very great help in reducing the incidence of surgical site infections, Dr. Duane added. “They increase attention to detail and decrease the rates of infection.”

Dr. Cook agreed. “Central line bundles are one of the things that work” for line-associated bloodstream infections, he said. Since their large-scale adoption, mortality from these infections has dropped significantly; it was hovering around 28,000 per year in the mid-2000s, he said. “That’s about how many men die from prostate cancer every year.”

Central line infections are very costly too, he added – around $46,000 per event. “That comes to around $2 billion in direct and indirect costs every year.”

A 2006 study demonstrated the efficacy of central line bundles in the fight against these potentially devastating infections.

The bundled intervention comprised hand washing, using full-barrier precautions during the insertion of central venous catheters, cleaning the skin with chlorhexidine, avoiding the femoral site if possible, and removing unnecessary catheters. The median rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections per 1,000 catheter-days decreased from 2.7 at baseline to 0 at 3 months after implementation of the study intervention.

Antibiotic-coated or impregnated catheters do not work as well. A 2016 Cochrane review of 57 studies determined that the devices didn’t improve sepsis, all-cause mortality, or catheter-related local infections.

The jury may still be out on coated dressings or securing devices, however. Another Cochrane review, of 22 studies, found a 40% decrease in central line–associated bloodstream infections with these items. “There was moderate evidence that tip colonization was reduced, but the authors said more research is needed.”

The evidence looks stronger for alcohol-impregnated port protectors, Dr. Cook said. Two studies in particular support their use. In an oncology unit, the rate of these infections dropped from 2.3 to 0.3 per 1,000 catheter days after the port protectors were instituted.

In the second study, infection rates declined from 1.43 to 0.69 per 1,000 line-days after the protectors came on board.

“The advantage was seen mostly in ICUs, so the recommendations are to use them there,” Dr. Cook said.

Neither Dr. Cook nor Dr. Duane had any relevant financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz Gal

SAN DIEGO – Some almost universally accepted measures against hospital-acquired infections are more costly, annoying, and time consuming than they’re worth, presenters agreed during a panel discussion at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Intra-abdominal antibiotic irrigation, chlorhexidine bathing, and even postsurgical antibiotic infusions have not consistently been shown to reduce infections. These measures do, however, ratchet up costs and can contribute to antibiotic resistance.

Some of these and other measures to prevent nosocomial infections may indeed reduce the risk, but the gain is small, said Charles H. Cook, MD.

“Chlorhexidine bathing, for example, is touted by many as a panacea for all the infections we’re talking about,” said Dr. Cook, a critical care surgeon at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, New York. “A recent meta-analysis in critical care units did find a reduced relative risk of 0.44 for central line bloodstream infections. But you needed to bathe 360 patients to prevent one infection. It’s what I call a long run for a short slide.”

Therese Duane, MD, FACS, agreed. A surgeon at the John Peter Smith Hospital, Ft. Worth, Tex., Dr. Duane reviewed three different guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infections: the ACS and Surgical Infection Society, the World Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In looking for similarities between the documents, she said she found several well-accepted practices that just aren’t supported by good data.

Presurgical antimicrobial infusions got a strong thumbs-up from all the groups, but only under a very specific circumstance: The medication has to be administered well in advance of surgery for it to be effective.

“Your goal is to get the appropriate concentration into the tissues by the time of incision,” Dr. Duane said. “It takes time to get there – if you give it after the incision, you have bleeding and cellular death, and the antimicrobials cannot get to that incision and do their job. If I’m starting a case and they haven’t been given, I don’t ever start them after the incision, because then you have all of the risks and none of the benefits. In my opinion, we need to move to no further antimicrobials once the incision or case is over because it serves no purpose and is inconsistent with good antibiotic stewardship.”

Adhesive drapes got a resounding “eh” from the guidelines, Dr. Duane said. “You really do not need them. They’re expensive and they’re not improving outcomes, so don’t waste your time or money. We need to think about minimizing what isn’t helpful and maximizing the things that are worthwhile. That’s the way to practice good socially responsible surgery without breaking the bank,” she said.

Antimicrobial sutures got weak recommendations, Dr. Duane said. The evidence supporting their use was not very strong, although she said she feels triclosan-coated sutures are helpful in all kinds of surgery. Preoperative showering with an antiseptic received strong support, with alcohol-containing preps superior to chlorhexidine, which is better than povidone-iodine–containing solutions.

Deep-space irrigation with aqueous iodophor also received a weak recommendation, but Dr. Duane said the evidence does not support the use of antibiotic-containing irrigation in either the abdomen or the incision. “And the guidelines came out strongly against using antimicrobial agents on the incision,” she said. None of the guidelines issued a recommendation for or against antimicrobial dressings.

Protocolized infection-control bundles are a very great help in reducing the incidence of surgical site infections, Dr. Duane added. “They increase attention to detail and decrease the rates of infection.”

Dr. Cook agreed. “Central line bundles are one of the things that work” for line-associated bloodstream infections, he said. Since their large-scale adoption, mortality from these infections has dropped significantly; it was hovering around 28,000 per year in the mid-2000s, he said. “That’s about how many men die from prostate cancer every year.”

Central line infections are very costly too, he added – around $46,000 per event. “That comes to around $2 billion in direct and indirect costs every year.”

A 2006 study demonstrated the efficacy of central line bundles in the fight against these potentially devastating infections.

The bundled intervention comprised hand washing, using full-barrier precautions during the insertion of central venous catheters, cleaning the skin with chlorhexidine, avoiding the femoral site if possible, and removing unnecessary catheters. The median rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections per 1,000 catheter-days decreased from 2.7 at baseline to 0 at 3 months after implementation of the study intervention.

Antibiotic-coated or impregnated catheters do not work as well. A 2016 Cochrane review of 57 studies determined that the devices didn’t improve sepsis, all-cause mortality, or catheter-related local infections.

The jury may still be out on coated dressings or securing devices, however. Another Cochrane review, of 22 studies, found a 40% decrease in central line–associated bloodstream infections with these items. “There was moderate evidence that tip colonization was reduced, but the authors said more research is needed.”

The evidence looks stronger for alcohol-impregnated port protectors, Dr. Cook said. Two studies in particular support their use. In an oncology unit, the rate of these infections dropped from 2.3 to 0.3 per 1,000 catheter days after the port protectors were instituted.

In the second study, infection rates declined from 1.43 to 0.69 per 1,000 line-days after the protectors came on board.

“The advantage was seen mostly in ICUs, so the recommendations are to use them there,” Dr. Cook said.

Neither Dr. Cook nor Dr. Duane had any relevant financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz Gal

SAN DIEGO – Some almost universally accepted measures against hospital-acquired infections are more costly, annoying, and time consuming than they’re worth, presenters agreed during a panel discussion at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Intra-abdominal antibiotic irrigation, chlorhexidine bathing, and even postsurgical antibiotic infusions have not consistently been shown to reduce infections. These measures do, however, ratchet up costs and can contribute to antibiotic resistance.

Some of these and other measures to prevent nosocomial infections may indeed reduce the risk, but the gain is small, said Charles H. Cook, MD.

“Chlorhexidine bathing, for example, is touted by many as a panacea for all the infections we’re talking about,” said Dr. Cook, a critical care surgeon at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, New York. “A recent meta-analysis in critical care units did find a reduced relative risk of 0.44 for central line bloodstream infections. But you needed to bathe 360 patients to prevent one infection. It’s what I call a long run for a short slide.”

Therese Duane, MD, FACS, agreed. A surgeon at the John Peter Smith Hospital, Ft. Worth, Tex., Dr. Duane reviewed three different guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infections: the ACS and Surgical Infection Society, the World Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In looking for similarities between the documents, she said she found several well-accepted practices that just aren’t supported by good data.

Presurgical antimicrobial infusions got a strong thumbs-up from all the groups, but only under a very specific circumstance: The medication has to be administered well in advance of surgery for it to be effective.

“Your goal is to get the appropriate concentration into the tissues by the time of incision,” Dr. Duane said. “It takes time to get there – if you give it after the incision, you have bleeding and cellular death, and the antimicrobials cannot get to that incision and do their job. If I’m starting a case and they haven’t been given, I don’t ever start them after the incision, because then you have all of the risks and none of the benefits. In my opinion, we need to move to no further antimicrobials once the incision or case is over because it serves no purpose and is inconsistent with good antibiotic stewardship.”

Adhesive drapes got a resounding “eh” from the guidelines, Dr. Duane said. “You really do not need them. They’re expensive and they’re not improving outcomes, so don’t waste your time or money. We need to think about minimizing what isn’t helpful and maximizing the things that are worthwhile. That’s the way to practice good socially responsible surgery without breaking the bank,” she said.

Antimicrobial sutures got weak recommendations, Dr. Duane said. The evidence supporting their use was not very strong, although she said she feels triclosan-coated sutures are helpful in all kinds of surgery. Preoperative showering with an antiseptic received strong support, with alcohol-containing preps superior to chlorhexidine, which is better than povidone-iodine–containing solutions.

Deep-space irrigation with aqueous iodophor also received a weak recommendation, but Dr. Duane said the evidence does not support the use of antibiotic-containing irrigation in either the abdomen or the incision. “And the guidelines came out strongly against using antimicrobial agents on the incision,” she said. None of the guidelines issued a recommendation for or against antimicrobial dressings.

Protocolized infection-control bundles are a very great help in reducing the incidence of surgical site infections, Dr. Duane added. “They increase attention to detail and decrease the rates of infection.”

Dr. Cook agreed. “Central line bundles are one of the things that work” for line-associated bloodstream infections, he said. Since their large-scale adoption, mortality from these infections has dropped significantly; it was hovering around 28,000 per year in the mid-2000s, he said. “That’s about how many men die from prostate cancer every year.”

Central line infections are very costly too, he added – around $46,000 per event. “That comes to around $2 billion in direct and indirect costs every year.”

A 2006 study demonstrated the efficacy of central line bundles in the fight against these potentially devastating infections.

The bundled intervention comprised hand washing, using full-barrier precautions during the insertion of central venous catheters, cleaning the skin with chlorhexidine, avoiding the femoral site if possible, and removing unnecessary catheters. The median rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections per 1,000 catheter-days decreased from 2.7 at baseline to 0 at 3 months after implementation of the study intervention.

Antibiotic-coated or impregnated catheters do not work as well. A 2016 Cochrane review of 57 studies determined that the devices didn’t improve sepsis, all-cause mortality, or catheter-related local infections.

The jury may still be out on coated dressings or securing devices, however. Another Cochrane review, of 22 studies, found a 40% decrease in central line–associated bloodstream infections with these items. “There was moderate evidence that tip colonization was reduced, but the authors said more research is needed.”

The evidence looks stronger for alcohol-impregnated port protectors, Dr. Cook said. Two studies in particular support their use. In an oncology unit, the rate of these infections dropped from 2.3 to 0.3 per 1,000 catheter days after the port protectors were instituted.

In the second study, infection rates declined from 1.43 to 0.69 per 1,000 line-days after the protectors came on board.

“The advantage was seen mostly in ICUs, so the recommendations are to use them there,” Dr. Cook said.

Neither Dr. Cook nor Dr. Duane had any relevant financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz Gal

FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Early evidence shows that surgery can alter gut microbiome

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Hypothyroidism carries higher surgical risk not captured by calculator

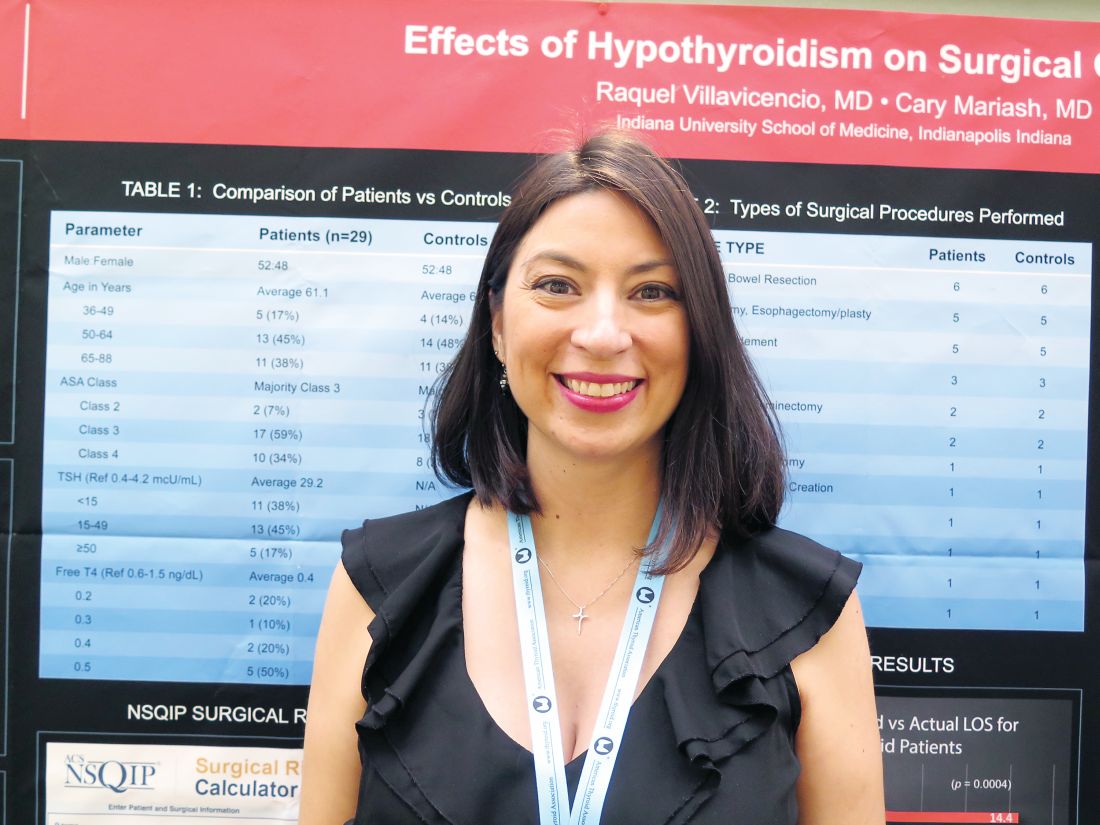

VICTORIA, B.C. – Even with contemporary anesthesia and surgical techniques, patients who are overtly hypothyroid at the time of major surgery have a rockier course, suggests a retrospective cohort study of 58 patients in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Actual length of stay for hypothyroid patients was twice that predicted by a commonly used risk calculator, whereas actual and predicted stays aligned well for euthyroid patients. The hypothyroid group had more cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation, ileus, reintubation, and death, although numbers were too small for statistical comparison.

“This will have an impact on how we look at patients, especially from a hospital standpoint and management. That’s quite a bit longer stay and quite a bit more cost. And the longer you stay, the more complications you have, too, so it could be riskier for the patient as well,” said first author Raquel Villavicencio, MD, a fellow at Indiana University at the time of the study, and now a clinical endocrinologist at Community Hospital in Indianapolis.

“Although we don’t consider hypothyroidism an absolute contraindication to surgery, especially if it’s necessary surgery, certainly anybody who is having elective surgery should have it postponed, in our opinion, until they are rendered euthyroid,” she said. “More studies are needed to look at this a little bit closer.”

Explaining the study’s rationale, Dr. Villavicencio noted, “This was a question that came up maybe three or four times a year, where we would get a hypothyroid patient and had to decide whether or not to clear them for surgery.”

Previous studies conducted at large institutions, the Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Hospital, had conflicting findings and were done about 30 years ago, she said. Anesthesia and surgical care have improved substantially since then, leading the investigators to hypothesize that hypothyroidism would not carry higher surgical risk today.

Dr. Villavicencio and her coinvestigator, Cary Mariash, MD, used their institutional database to identify 29 adult patients with a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of greater than 10 mcU/mL alone or with a TSH level exceeding the upper limit of normal along with a free thyroxine (T4) level of less than 0.6 ng/dL who underwent surgery during 2010-2015. They matched each patient on age, sex, and surgical procedure with a control euthyroid patient.

The mean TSH level in the hypothyroid group was 29.2 mcU/mL. The majority of patients in each group – 59% of the hypothyroid group and 62% of the euthyroid group – had an American Surgical Association class of 3, denoting that this was a fairly sick population. The groups were generally similar on rates of comorbidity, except that the euthyroid patients had a slightly higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea.

In both groups, the majority of procedures were laparotomy and/or bowel resection; pharyngolaryngectomy and esophagectomy/esophagoplasty; and wound or bone debridement.

Main results showed that in the hypothyroid group, hospital length of stay predicted with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator was 6.9 days, but actual length of stay was 14.4 days (P = .0004). In contrast, in the euthyroid group, predicted length of stay was a similar at 7.1 days, and actual length of stay was statistically indistinguishable at 9.2 days (P = .1).

“Hypothyroidism is not taken into account with this calculator,” Dr. Villavicencio noted, adding that she was unaware of any surgical calculators that do.

One patient in the hypothyroid group died, compared with none in the euthyroid group. In terms of postoperative cardiac complications, two patients in the hypothyroid group experienced atrial fibrillation, and there was one case of pulseless electrical–activity arrest in each group.

The groups did not differ on incidence of hypothermia, bradycardia, hyponatremia, time to extubation, and hypotension. However, mean arterial pressure tended to be lower in the hypothyroid group (51 mm Hg) than in the euthyroid group (56 mm Hg), and the former more often needed vasopressors. Furthermore, postoperative ileus and reintubation were more common in the hypothyroid group.

“I think that there are kind of a lot of little things that add up to explain [the longer stay],” said Dr. Villavicencio, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Even with contemporary anesthesia and surgical techniques, patients who are overtly hypothyroid at the time of major surgery have a rockier course, suggests a retrospective cohort study of 58 patients in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Actual length of stay for hypothyroid patients was twice that predicted by a commonly used risk calculator, whereas actual and predicted stays aligned well for euthyroid patients. The hypothyroid group had more cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation, ileus, reintubation, and death, although numbers were too small for statistical comparison.

“This will have an impact on how we look at patients, especially from a hospital standpoint and management. That’s quite a bit longer stay and quite a bit more cost. And the longer you stay, the more complications you have, too, so it could be riskier for the patient as well,” said first author Raquel Villavicencio, MD, a fellow at Indiana University at the time of the study, and now a clinical endocrinologist at Community Hospital in Indianapolis.

“Although we don’t consider hypothyroidism an absolute contraindication to surgery, especially if it’s necessary surgery, certainly anybody who is having elective surgery should have it postponed, in our opinion, until they are rendered euthyroid,” she said. “More studies are needed to look at this a little bit closer.”

Explaining the study’s rationale, Dr. Villavicencio noted, “This was a question that came up maybe three or four times a year, where we would get a hypothyroid patient and had to decide whether or not to clear them for surgery.”

Previous studies conducted at large institutions, the Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Hospital, had conflicting findings and were done about 30 years ago, she said. Anesthesia and surgical care have improved substantially since then, leading the investigators to hypothesize that hypothyroidism would not carry higher surgical risk today.

Dr. Villavicencio and her coinvestigator, Cary Mariash, MD, used their institutional database to identify 29 adult patients with a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of greater than 10 mcU/mL alone or with a TSH level exceeding the upper limit of normal along with a free thyroxine (T4) level of less than 0.6 ng/dL who underwent surgery during 2010-2015. They matched each patient on age, sex, and surgical procedure with a control euthyroid patient.

The mean TSH level in the hypothyroid group was 29.2 mcU/mL. The majority of patients in each group – 59% of the hypothyroid group and 62% of the euthyroid group – had an American Surgical Association class of 3, denoting that this was a fairly sick population. The groups were generally similar on rates of comorbidity, except that the euthyroid patients had a slightly higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea.

In both groups, the majority of procedures were laparotomy and/or bowel resection; pharyngolaryngectomy and esophagectomy/esophagoplasty; and wound or bone debridement.

Main results showed that in the hypothyroid group, hospital length of stay predicted with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator was 6.9 days, but actual length of stay was 14.4 days (P = .0004). In contrast, in the euthyroid group, predicted length of stay was a similar at 7.1 days, and actual length of stay was statistically indistinguishable at 9.2 days (P = .1).

“Hypothyroidism is not taken into account with this calculator,” Dr. Villavicencio noted, adding that she was unaware of any surgical calculators that do.

One patient in the hypothyroid group died, compared with none in the euthyroid group. In terms of postoperative cardiac complications, two patients in the hypothyroid group experienced atrial fibrillation, and there was one case of pulseless electrical–activity arrest in each group.

The groups did not differ on incidence of hypothermia, bradycardia, hyponatremia, time to extubation, and hypotension. However, mean arterial pressure tended to be lower in the hypothyroid group (51 mm Hg) than in the euthyroid group (56 mm Hg), and the former more often needed vasopressors. Furthermore, postoperative ileus and reintubation were more common in the hypothyroid group.

“I think that there are kind of a lot of little things that add up to explain [the longer stay],” said Dr. Villavicencio, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Even with contemporary anesthesia and surgical techniques, patients who are overtly hypothyroid at the time of major surgery have a rockier course, suggests a retrospective cohort study of 58 patients in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Actual length of stay for hypothyroid patients was twice that predicted by a commonly used risk calculator, whereas actual and predicted stays aligned well for euthyroid patients. The hypothyroid group had more cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation, ileus, reintubation, and death, although numbers were too small for statistical comparison.

“This will have an impact on how we look at patients, especially from a hospital standpoint and management. That’s quite a bit longer stay and quite a bit more cost. And the longer you stay, the more complications you have, too, so it could be riskier for the patient as well,” said first author Raquel Villavicencio, MD, a fellow at Indiana University at the time of the study, and now a clinical endocrinologist at Community Hospital in Indianapolis.

“Although we don’t consider hypothyroidism an absolute contraindication to surgery, especially if it’s necessary surgery, certainly anybody who is having elective surgery should have it postponed, in our opinion, until they are rendered euthyroid,” she said. “More studies are needed to look at this a little bit closer.”

Explaining the study’s rationale, Dr. Villavicencio noted, “This was a question that came up maybe three or four times a year, where we would get a hypothyroid patient and had to decide whether or not to clear them for surgery.”

Previous studies conducted at large institutions, the Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Hospital, had conflicting findings and were done about 30 years ago, she said. Anesthesia and surgical care have improved substantially since then, leading the investigators to hypothesize that hypothyroidism would not carry higher surgical risk today.

Dr. Villavicencio and her coinvestigator, Cary Mariash, MD, used their institutional database to identify 29 adult patients with a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of greater than 10 mcU/mL alone or with a TSH level exceeding the upper limit of normal along with a free thyroxine (T4) level of less than 0.6 ng/dL who underwent surgery during 2010-2015. They matched each patient on age, sex, and surgical procedure with a control euthyroid patient.

The mean TSH level in the hypothyroid group was 29.2 mcU/mL. The majority of patients in each group – 59% of the hypothyroid group and 62% of the euthyroid group – had an American Surgical Association class of 3, denoting that this was a fairly sick population. The groups were generally similar on rates of comorbidity, except that the euthyroid patients had a slightly higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea.

In both groups, the majority of procedures were laparotomy and/or bowel resection; pharyngolaryngectomy and esophagectomy/esophagoplasty; and wound or bone debridement.

Main results showed that in the hypothyroid group, hospital length of stay predicted with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator was 6.9 days, but actual length of stay was 14.4 days (P = .0004). In contrast, in the euthyroid group, predicted length of stay was a similar at 7.1 days, and actual length of stay was statistically indistinguishable at 9.2 days (P = .1).

“Hypothyroidism is not taken into account with this calculator,” Dr. Villavicencio noted, adding that she was unaware of any surgical calculators that do.

One patient in the hypothyroid group died, compared with none in the euthyroid group. In terms of postoperative cardiac complications, two patients in the hypothyroid group experienced atrial fibrillation, and there was one case of pulseless electrical–activity arrest in each group.

The groups did not differ on incidence of hypothermia, bradycardia, hyponatremia, time to extubation, and hypotension. However, mean arterial pressure tended to be lower in the hypothyroid group (51 mm Hg) than in the euthyroid group (56 mm Hg), and the former more often needed vasopressors. Furthermore, postoperative ileus and reintubation were more common in the hypothyroid group.

“I think that there are kind of a lot of little things that add up to explain [the longer stay],” said Dr. Villavicencio, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Actual length of stay was significantly longer than calculator-predicted length of stay among hypothyroid patients (14.4 vs. 6.9 days, P = .0004) but not among euthyroid patients (9.2 vs. 7.1 days; P = .1).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 29 hypothyroid patients and 29 matched euthyroid patients undergoing major surgery.

Disclosures: Dr. Villavicencio disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

State regulations for tattoo facilities increased blood donor pools

SAN DIEGO – Tattoos are rapidly moving into mainstream America, and as more states regulate tattoo facilities, persons with tattoos can be blood donors without compromising patient safety, Mary Townsend of Blood Systems Inc. reported at the annual meeting of the American Association of Blood Banks.

“Two big states – Arizona and California – were added to the list of approved states, and we had a gain of 2,216 donors in California during a 3-month period and a gain of 4,035 donors in Arizona over 4 months,” Ms. Townsend said.

Both the AABB and the Food and Drug Administration require a 12-month deferral of donors after they have received tattoos using nonsterile needles or reusable ink. The FDA’s current 2015 guidance also states that tattooed donors can give plasma as soon as the inked area has healed if they reside in a state with applied inspections and licenses for tattoo facilities, and if a sterile needle and ink were used.

Blood Systems monitors state regulations to see if they require tattoo establishments to be licensed and require the use of sterile needles and non-reusable ink. To be considered an approved state, the regulations have to be statewide, covering all jurisdictions.

In the study, Ms. Townsend and her colleagues compared the rates of donors who were deferred before and after Arizona and California were added to the list of approved states, to determine the potential gain in donors with changes in state tattoo licensing regulations.

They analyzed blood centers in California and Arizona before and after implementation of state tattoo regulations, and also screened individuals who had received tattoos in those states with the question: “In the past 12 months have you had a tattoo?” and if the answer was ‘yes,’ if the tattoo was applied by a state regulated facility.

For California, they compared two periods – 3 months before regulations were implemented (February to April of 2015) and 3 months after (February to April of 2016) regulations were implemented. For Arizona, they selected a 4-month period (December 2015 to March 2016) and 4 months afterward (December 2016 to March 2017).

A higher proportion of donors who came to centers to donate blood admitted to having gotten a tattoo within the last 12 months in the postregulatory period in both states. The increase in donors occurred immediately following the addition of both states to the Acceptable States List. Accepted donors increased 13-fold in California and 3-fold in Arizona. The absolute number of accepted donors with tattoos rose from 13 to 567 in California and from 151 to 1,496 in Arizona, which represented an annual potential gain of 2,216 and 4,035 additional blood donations.

For blood donors who received a tattoo in a regulated state, blood donations were reviewed for the presence of infectious disease markers including HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. All donors who had received a tattoo in a regulated state tested negative for HIV, HBV, and HCV.

“Roughly one in three people (in the United States) have a tattoo and, of those, about 70% have more than one tattoo. The bottom line is that 45 million Americans have at least one tattoo,” she said. As state regulations adhere to guidelines regarding tattoos and blood donation, the pool of donors increases.

SAN DIEGO – Tattoos are rapidly moving into mainstream America, and as more states regulate tattoo facilities, persons with tattoos can be blood donors without compromising patient safety, Mary Townsend of Blood Systems Inc. reported at the annual meeting of the American Association of Blood Banks.

“Two big states – Arizona and California – were added to the list of approved states, and we had a gain of 2,216 donors in California during a 3-month period and a gain of 4,035 donors in Arizona over 4 months,” Ms. Townsend said.

Both the AABB and the Food and Drug Administration require a 12-month deferral of donors after they have received tattoos using nonsterile needles or reusable ink. The FDA’s current 2015 guidance also states that tattooed donors can give plasma as soon as the inked area has healed if they reside in a state with applied inspections and licenses for tattoo facilities, and if a sterile needle and ink were used.

Blood Systems monitors state regulations to see if they require tattoo establishments to be licensed and require the use of sterile needles and non-reusable ink. To be considered an approved state, the regulations have to be statewide, covering all jurisdictions.

In the study, Ms. Townsend and her colleagues compared the rates of donors who were deferred before and after Arizona and California were added to the list of approved states, to determine the potential gain in donors with changes in state tattoo licensing regulations.

They analyzed blood centers in California and Arizona before and after implementation of state tattoo regulations, and also screened individuals who had received tattoos in those states with the question: “In the past 12 months have you had a tattoo?” and if the answer was ‘yes,’ if the tattoo was applied by a state regulated facility.

For California, they compared two periods – 3 months before regulations were implemented (February to April of 2015) and 3 months after (February to April of 2016) regulations were implemented. For Arizona, they selected a 4-month period (December 2015 to March 2016) and 4 months afterward (December 2016 to March 2017).

A higher proportion of donors who came to centers to donate blood admitted to having gotten a tattoo within the last 12 months in the postregulatory period in both states. The increase in donors occurred immediately following the addition of both states to the Acceptable States List. Accepted donors increased 13-fold in California and 3-fold in Arizona. The absolute number of accepted donors with tattoos rose from 13 to 567 in California and from 151 to 1,496 in Arizona, which represented an annual potential gain of 2,216 and 4,035 additional blood donations.

For blood donors who received a tattoo in a regulated state, blood donations were reviewed for the presence of infectious disease markers including HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. All donors who had received a tattoo in a regulated state tested negative for HIV, HBV, and HCV.

“Roughly one in three people (in the United States) have a tattoo and, of those, about 70% have more than one tattoo. The bottom line is that 45 million Americans have at least one tattoo,” she said. As state regulations adhere to guidelines regarding tattoos and blood donation, the pool of donors increases.

SAN DIEGO – Tattoos are rapidly moving into mainstream America, and as more states regulate tattoo facilities, persons with tattoos can be blood donors without compromising patient safety, Mary Townsend of Blood Systems Inc. reported at the annual meeting of the American Association of Blood Banks.

“Two big states – Arizona and California – were added to the list of approved states, and we had a gain of 2,216 donors in California during a 3-month period and a gain of 4,035 donors in Arizona over 4 months,” Ms. Townsend said.

Both the AABB and the Food and Drug Administration require a 12-month deferral of donors after they have received tattoos using nonsterile needles or reusable ink. The FDA’s current 2015 guidance also states that tattooed donors can give plasma as soon as the inked area has healed if they reside in a state with applied inspections and licenses for tattoo facilities, and if a sterile needle and ink were used.

Blood Systems monitors state regulations to see if they require tattoo establishments to be licensed and require the use of sterile needles and non-reusable ink. To be considered an approved state, the regulations have to be statewide, covering all jurisdictions.

In the study, Ms. Townsend and her colleagues compared the rates of donors who were deferred before and after Arizona and California were added to the list of approved states, to determine the potential gain in donors with changes in state tattoo licensing regulations.

They analyzed blood centers in California and Arizona before and after implementation of state tattoo regulations, and also screened individuals who had received tattoos in those states with the question: “In the past 12 months have you had a tattoo?” and if the answer was ‘yes,’ if the tattoo was applied by a state regulated facility.

For California, they compared two periods – 3 months before regulations were implemented (February to April of 2015) and 3 months after (February to April of 2016) regulations were implemented. For Arizona, they selected a 4-month period (December 2015 to March 2016) and 4 months afterward (December 2016 to March 2017).

A higher proportion of donors who came to centers to donate blood admitted to having gotten a tattoo within the last 12 months in the postregulatory period in both states. The increase in donors occurred immediately following the addition of both states to the Acceptable States List. Accepted donors increased 13-fold in California and 3-fold in Arizona. The absolute number of accepted donors with tattoos rose from 13 to 567 in California and from 151 to 1,496 in Arizona, which represented an annual potential gain of 2,216 and 4,035 additional blood donations.

For blood donors who received a tattoo in a regulated state, blood donations were reviewed for the presence of infectious disease markers including HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. All donors who had received a tattoo in a regulated state tested negative for HIV, HBV, and HCV.

“Roughly one in three people (in the United States) have a tattoo and, of those, about 70% have more than one tattoo. The bottom line is that 45 million Americans have at least one tattoo,” she said. As state regulations adhere to guidelines regarding tattoos and blood donation, the pool of donors increases.

AT AABB 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The absolute number of accepted donors with tattoos rose from 13 to 567 in California and from 151 to 1,496 in Arizona, which represented an annual potential gain of 2,216 and 4,035 additional blood donations.

Data source: An analysis of blood centers in California and Arizona before and after state tattoo regulations were implemented.

Disclosures: Dr. Townsend has no disclosures.

VIDEO: How to manage surgical pain in opioid addiction treatment

NEW ORLEANS – How do you manage surgical pain when someone is in treatment for opioid addiction? And how do you manage chronic pain?

It is possible to give patients opioids for post-op pain without increasing the risk of relapse, according to Margaret Chaplin, MD, a staff psychiatrist at Community Mental Health Affiliates in New Britain, Conn.

Dr. Chaplin generally uses buprenorphine and naloxone (Suboxone) for opioid use disorder, and she likes to keep her patients on it for surgery. That often means, however, talking with skeptical surgeons and anesthesiologists beforehand, and reminding them that buprenorphine itself has analgesic effects. Meanwhile, when her patients have chronic pain, sometimes they need help understanding that aspirin and acetaminophen help, even if they don’t give patients a warm, fuzzy feeling.

Dr. Chaplin shared those tips and more about pain management in opioid addiction in an interview at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

NEW ORLEANS – How do you manage surgical pain when someone is in treatment for opioid addiction? And how do you manage chronic pain?

It is possible to give patients opioids for post-op pain without increasing the risk of relapse, according to Margaret Chaplin, MD, a staff psychiatrist at Community Mental Health Affiliates in New Britain, Conn.

Dr. Chaplin generally uses buprenorphine and naloxone (Suboxone) for opioid use disorder, and she likes to keep her patients on it for surgery. That often means, however, talking with skeptical surgeons and anesthesiologists beforehand, and reminding them that buprenorphine itself has analgesic effects. Meanwhile, when her patients have chronic pain, sometimes they need help understanding that aspirin and acetaminophen help, even if they don’t give patients a warm, fuzzy feeling.

Dr. Chaplin shared those tips and more about pain management in opioid addiction in an interview at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

NEW ORLEANS – How do you manage surgical pain when someone is in treatment for opioid addiction? And how do you manage chronic pain?

It is possible to give patients opioids for post-op pain without increasing the risk of relapse, according to Margaret Chaplin, MD, a staff psychiatrist at Community Mental Health Affiliates in New Britain, Conn.

Dr. Chaplin generally uses buprenorphine and naloxone (Suboxone) for opioid use disorder, and she likes to keep her patients on it for surgery. That often means, however, talking with skeptical surgeons and anesthesiologists beforehand, and reminding them that buprenorphine itself has analgesic effects. Meanwhile, when her patients have chronic pain, sometimes they need help understanding that aspirin and acetaminophen help, even if they don’t give patients a warm, fuzzy feeling.

Dr. Chaplin shared those tips and more about pain management in opioid addiction in an interview at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

AT IPS 2017

Session highlights controversies in diverticulitis management

SAN DIEGO – During the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, a panel of experts discussed a wide range of evolving controversies in the management of complicated diverticulitis.

John Migaly, MD, kicked off the session by exploring the current evidence for laparoscopic lavage versus primary resection for Hinchey III diverticulitis. “Over the past two decades there has been a growing utilization of primary resection and reanastomoses with or without the use of ileostomy,” said Dr. Migaly, director of the general surgery residency program at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “And most recently over the last 5 or 10 years there’s been growing enthusiasm for laparoscopic lavage for Hinchey III diverticulitis. The enthusiasm for this procedure is based on [its accessibility] to all of us who operate on the colon in the acute setting.”

The DILALA trial makes the best case for laparoscopic lavage, “but it doesn’t make a very good one,” he commented. The trial was conducted in nine surgical departments in Sweden and Denmark (Ann Surg. 2016;263[1]:117-22). Hinchey III patients were randomized 1:1 to laparoscopic lavage or the Hartmann procedure. The primary outcome was reoperations within 12 months. An early analysis of the short-term outcomes in 83 patients found similar 30-day and 90-day mortality and morbidity. Its authors concluded that laparoscopic lavage had equivalent morbidity and mortality compared with radical resection, shorter operative time, shorter time in the recovery unit, a shorter hospital stay, but no difference in the rate of reoperation.

“It was found to be safe and feasible,” Dr. Migaly said. One year later, the researchers presented their 12-month outcomes and came to the same conclusions. Limitations of the data are that it was conducted in nine centers “but they enrolled only 83 patients, so it seems underpowered,” he said. “And there was no mention of the incidence of abdominal abscess requiring percutaneous drainage or episodes of diverticulitis. The data seem a little less granular than the LADIES trial.”

The SCANDIV trial is the largest study on the topic to date, a randomized clinical superiority trial conducted at 21 centers in Sweden and Norway (JAMA 2015;314[13]:1364-75). Of the 509 patients screened, 415 were eligible and 199 were enrolled: 101 to laparoscopic lavage, 98 to colon resection. The primary endpoint was severe postoperative complications within 90 days, defined as a Clavien-Dindo score of over 3. The researchers found no difference in major complications nor in 90-day mortality between the two groups. The rate of reoperation was significantly higher in the lavage group, compared with the resection group (20.3% vs. 5.7%, respectively). Four sigmoid cancers were missed in the lavage group and, while the length of operation was significantly shorter in the lavage group, there were no differences between the two groups in hospital length of stay or quality of life.

A meta-analysis of the three randomized controlled trials that Dr. Migaly reviewed concluded that laparoscopic lavage, compared with resection, for Hinchey III diverticulitis increased the rate of total reoperations, the rate of reoperation for infection, and the rate of subsequent percutaneous drainage (J Gastrointest Surg 2017;21[9]:1491-99). A larger, more recent meta-analysis of 589 patients, including the three randomized controlled trials that Dr. Migaly discussed, concluded that laparoscopic lavage patients, compared with resection patients, had three times the risk of persistent peritonitis, intra-abdominal abscess, and emergency reoperative surgery. “Therefore, a reasonable conclusion would be that data at this point does not support the use of laparoscopic lavage,” he said.

The initial procedure of choice for most patients is abscess drainage via CT-guided percutaneous drainage. “There are some patients who are not candidates for percutaneous drainage, [such as] if the abscess is not accessible to the radiologist, if the patient is anticoagulated, and if the patient requires emergent surgical intervention irrespective of the abscess,” said Dr. Maron, a colorectal surgeon who practices at Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “There is also a question of cavity size. Most authors in the literature use a cut-off of 3-4 cm.”

The goal is complete drainage of the abscess, and sometimes multiple catheters will be required. One study found that predictors of successful abscess drainage included having a well-defined, unilocular abscess. The success rate fell to 63% for patients who presented with more complex abscesses, including those that were loculated, poorly defined, associated with a fistula, and contained feces or semisolid material (Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1009-13).

The 2014 ASCRS Practice Parameters includes the recommendation that elective colectomy should typically be considered after the patient recovers from an episode of complicated diverticulitis, “but some of the data may be calling that into question,” Dr. Maron said. In one series of 18 patients with an abscess treated percutaneously, 11 refused surgery and 7 had significant comorbidity (Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:331-6). Three patients died of a pre-existing condition and 7 of the 15 surviving patients had recurrent diverticulitis. Three underwent surgery and four were treated medically. The authors found no association between long-term failure and abscess location or previous episodes of diverticulitis.

In a larger study, researchers identified 218 patients who were initially treated with intravenous antibiotics and percutaneous drain (Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:622-6). About 10% of the patients required an urgent operation, while most of the other patients underwent elective resection, but 15% of patients did not undergo a subsequent colectomy. “Most of these patients were medically unfit to undergo surgery,” he noted. Abscess location was more commonly paracolic than pelvic. The mean abscess size was 4.2 cm, and the drain was left in for a median of 20 days. The recurrence rate in this series was only 30%, but none of the recurrences required surgery. The authors found that abscesses greater than 5 cm in size were associated with a greater risk of recurrence (P = .003). They concluded that observation after percutaneous drainage is safe in selected patients.

Based on results from this and other more recent studies, Dr. Maron said that it remains unclear whether surgeons should wait and watch or operate after successful percutaneous drainage of diverticular abscess. The data are “not as robust as we’d like … most of these are retrospective studies,” he said. “There’s quite a bit of inherent selection bias, and there is no standardization with regard to length of time of percutaneous drain, rationale for nonoperative management versus elective colectomy. What we do know is that there are some patients who can be managed safely without surgery. Unfortunately, there is no good algorithm I can offer you: Perhaps larger abscesses can portend a higher recurrence. I don’t think we’ll have a good answer to this until we perform a prospective randomized trial. However, we may learn some data from patients managed by peritoneal lavage and drain placement.”

Next, consider how to perform the procedure: laparoscopic or open? “But again, you’re going to look at how stable your patient is, what your skill set is, what equipment is available, and if the patient has had previous abdominal surgeries,” she advised. “In the traditional Hartmann procedure, you resect the perforated segment. You try not to open any tissue planes that you don’t have to. You do just enough so you can bring up a colostomy; you close the rectum or you make a mucous fistula. The problem with this operation is that up to 80% of these patients have their colostomy closed. That is why there is all this controversy. If there is any question, this [procedure] is always the safest option; there’s no anastomosis.”

What about a performing resection and a colorectal anastomosis? This is usually done more commonly in the elective situation, “when things are perfect, when you have healthy tissue,” Dr. Hull said. “If you do it in the emergent situation you have to think to yourself, ‘Could my patient tolerate a leak?’ You won’t want to do this operation on a 72-year-old who’s on steroids for chronic pulmonary disease and has coronary artery disease, because if they had a leak, they’d probably die.”

The third procedural option is to resect bowel (usually sigmoid) with colorectal anastomosis and diversion (loop ileostomy). “This is always my preferred choice,” Dr. Hull said. “I always am thinking, ‘Why can’t I do this?’ The reason is, closure of ileostomy is much easier than a Hartmann reversal, and 90% of these patients get reversed.” In a multicenter trial conducted by Swedish researchers, 62 patients were randomized to Hartmann’s procedure versus primary anastomosis with diverting ileostomy for perforated left-sided diverticulitis (Ann Surg. 2012;256[5]:819-27). The mortality and complications were similar, but the number of patients who got their stoma reversed was significantly less in the Hartmann’s group, compared with the primary anastomosis group (57% vs. 90%, respectively), and the serious complications were much higher in the Hartmann’s group (20% vs. 0). She cited an article from the World Journal of Emergency Surgery as one of the most comprehensive reviews of the subject.

So what is a surgeon to do? For an anastomosis after resection, “consider patient factors: Are they stable?” Dr. Hull said. “What are their comorbid conditions? You have to think, ‘What is my preference? Am I comfortable putting this back together?’ But a primary anastomosis is feasible, even in the acute setting with or without diverting ileostomy. The laparoscopic approach is typically preferred, but if that’s not in your armamentarium, the open [approach] is just fine. You should always perform a leak test. You can also do on table colonic lavage if feasible, especially if you have a large stool burden.”

None of the speakers reported having financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – During the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, a panel of experts discussed a wide range of evolving controversies in the management of complicated diverticulitis.

John Migaly, MD, kicked off the session by exploring the current evidence for laparoscopic lavage versus primary resection for Hinchey III diverticulitis. “Over the past two decades there has been a growing utilization of primary resection and reanastomoses with or without the use of ileostomy,” said Dr. Migaly, director of the general surgery residency program at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “And most recently over the last 5 or 10 years there’s been growing enthusiasm for laparoscopic lavage for Hinchey III diverticulitis. The enthusiasm for this procedure is based on [its accessibility] to all of us who operate on the colon in the acute setting.”

The DILALA trial makes the best case for laparoscopic lavage, “but it doesn’t make a very good one,” he commented. The trial was conducted in nine surgical departments in Sweden and Denmark (Ann Surg. 2016;263[1]:117-22). Hinchey III patients were randomized 1:1 to laparoscopic lavage or the Hartmann procedure. The primary outcome was reoperations within 12 months. An early analysis of the short-term outcomes in 83 patients found similar 30-day and 90-day mortality and morbidity. Its authors concluded that laparoscopic lavage had equivalent morbidity and mortality compared with radical resection, shorter operative time, shorter time in the recovery unit, a shorter hospital stay, but no difference in the rate of reoperation.

“It was found to be safe and feasible,” Dr. Migaly said. One year later, the researchers presented their 12-month outcomes and came to the same conclusions. Limitations of the data are that it was conducted in nine centers “but they enrolled only 83 patients, so it seems underpowered,” he said. “And there was no mention of the incidence of abdominal abscess requiring percutaneous drainage or episodes of diverticulitis. The data seem a little less granular than the LADIES trial.”

The SCANDIV trial is the largest study on the topic to date, a randomized clinical superiority trial conducted at 21 centers in Sweden and Norway (JAMA 2015;314[13]:1364-75). Of the 509 patients screened, 415 were eligible and 199 were enrolled: 101 to laparoscopic lavage, 98 to colon resection. The primary endpoint was severe postoperative complications within 90 days, defined as a Clavien-Dindo score of over 3. The researchers found no difference in major complications nor in 90-day mortality between the two groups. The rate of reoperation was significantly higher in the lavage group, compared with the resection group (20.3% vs. 5.7%, respectively). Four sigmoid cancers were missed in the lavage group and, while the length of operation was significantly shorter in the lavage group, there were no differences between the two groups in hospital length of stay or quality of life.

A meta-analysis of the three randomized controlled trials that Dr. Migaly reviewed concluded that laparoscopic lavage, compared with resection, for Hinchey III diverticulitis increased the rate of total reoperations, the rate of reoperation for infection, and the rate of subsequent percutaneous drainage (J Gastrointest Surg 2017;21[9]:1491-99). A larger, more recent meta-analysis of 589 patients, including the three randomized controlled trials that Dr. Migaly discussed, concluded that laparoscopic lavage patients, compared with resection patients, had three times the risk of persistent peritonitis, intra-abdominal abscess, and emergency reoperative surgery. “Therefore, a reasonable conclusion would be that data at this point does not support the use of laparoscopic lavage,” he said.

The initial procedure of choice for most patients is abscess drainage via CT-guided percutaneous drainage. “There are some patients who are not candidates for percutaneous drainage, [such as] if the abscess is not accessible to the radiologist, if the patient is anticoagulated, and if the patient requires emergent surgical intervention irrespective of the abscess,” said Dr. Maron, a colorectal surgeon who practices at Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “There is also a question of cavity size. Most authors in the literature use a cut-off of 3-4 cm.”

The goal is complete drainage of the abscess, and sometimes multiple catheters will be required. One study found that predictors of successful abscess drainage included having a well-defined, unilocular abscess. The success rate fell to 63% for patients who presented with more complex abscesses, including those that were loculated, poorly defined, associated with a fistula, and contained feces or semisolid material (Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1009-13).

The 2014 ASCRS Practice Parameters includes the recommendation that elective colectomy should typically be considered after the patient recovers from an episode of complicated diverticulitis, “but some of the data may be calling that into question,” Dr. Maron said. In one series of 18 patients with an abscess treated percutaneously, 11 refused surgery and 7 had significant comorbidity (Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:331-6). Three patients died of a pre-existing condition and 7 of the 15 surviving patients had recurrent diverticulitis. Three underwent surgery and four were treated medically. The authors found no association between long-term failure and abscess location or previous episodes of diverticulitis.

In a larger study, researchers identified 218 patients who were initially treated with intravenous antibiotics and percutaneous drain (Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:622-6). About 10% of the patients required an urgent operation, while most of the other patients underwent elective resection, but 15% of patients did not undergo a subsequent colectomy. “Most of these patients were medically unfit to undergo surgery,” he noted. Abscess location was more commonly paracolic than pelvic. The mean abscess size was 4.2 cm, and the drain was left in for a median of 20 days. The recurrence rate in this series was only 30%, but none of the recurrences required surgery. The authors found that abscesses greater than 5 cm in size were associated with a greater risk of recurrence (P = .003). They concluded that observation after percutaneous drainage is safe in selected patients.

Based on results from this and other more recent studies, Dr. Maron said that it remains unclear whether surgeons should wait and watch or operate after successful percutaneous drainage of diverticular abscess. The data are “not as robust as we’d like … most of these are retrospective studies,” he said. “There’s quite a bit of inherent selection bias, and there is no standardization with regard to length of time of percutaneous drain, rationale for nonoperative management versus elective colectomy. What we do know is that there are some patients who can be managed safely without surgery. Unfortunately, there is no good algorithm I can offer you: Perhaps larger abscesses can portend a higher recurrence. I don’t think we’ll have a good answer to this until we perform a prospective randomized trial. However, we may learn some data from patients managed by peritoneal lavage and drain placement.”

Next, consider how to perform the procedure: laparoscopic or open? “But again, you’re going to look at how stable your patient is, what your skill set is, what equipment is available, and if the patient has had previous abdominal surgeries,” she advised. “In the traditional Hartmann procedure, you resect the perforated segment. You try not to open any tissue planes that you don’t have to. You do just enough so you can bring up a colostomy; you close the rectum or you make a mucous fistula. The problem with this operation is that up to 80% of these patients have their colostomy closed. That is why there is all this controversy. If there is any question, this [procedure] is always the safest option; there’s no anastomosis.”

What about a performing resection and a colorectal anastomosis? This is usually done more commonly in the elective situation, “when things are perfect, when you have healthy tissue,” Dr. Hull said. “If you do it in the emergent situation you have to think to yourself, ‘Could my patient tolerate a leak?’ You won’t want to do this operation on a 72-year-old who’s on steroids for chronic pulmonary disease and has coronary artery disease, because if they had a leak, they’d probably die.”

The third procedural option is to resect bowel (usually sigmoid) with colorectal anastomosis and diversion (loop ileostomy). “This is always my preferred choice,” Dr. Hull said. “I always am thinking, ‘Why can’t I do this?’ The reason is, closure of ileostomy is much easier than a Hartmann reversal, and 90% of these patients get reversed.” In a multicenter trial conducted by Swedish researchers, 62 patients were randomized to Hartmann’s procedure versus primary anastomosis with diverting ileostomy for perforated left-sided diverticulitis (Ann Surg. 2012;256[5]:819-27). The mortality and complications were similar, but the number of patients who got their stoma reversed was significantly less in the Hartmann’s group, compared with the primary anastomosis group (57% vs. 90%, respectively), and the serious complications were much higher in the Hartmann’s group (20% vs. 0). She cited an article from the World Journal of Emergency Surgery as one of the most comprehensive reviews of the subject.

So what is a surgeon to do? For an anastomosis after resection, “consider patient factors: Are they stable?” Dr. Hull said. “What are their comorbid conditions? You have to think, ‘What is my preference? Am I comfortable putting this back together?’ But a primary anastomosis is feasible, even in the acute setting with or without diverting ileostomy. The laparoscopic approach is typically preferred, but if that’s not in your armamentarium, the open [approach] is just fine. You should always perform a leak test. You can also do on table colonic lavage if feasible, especially if you have a large stool burden.”

None of the speakers reported having financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – During the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, a panel of experts discussed a wide range of evolving controversies in the management of complicated diverticulitis.