User login

FDA finalizes guidance for power morcellators in gynecologic surgery

The agency noted that physicians should conduct a thorough preoperative screening and that the devices should only be used for hysterectomies and myomectomies. Clinicians should not use the devices in cases involving uterine malignancy or suspected uterine malignancy.

In addition, clinicians should not use morcellators to remove uterine tissue containing suspected fibroids in women older than 50 years or who are postmenopausal. Nor should the devices be used for women who are “candidates for removal of tissue (en bloc) through the vagina or via a minilaparotomy incision,” the agency said.

The safety communication, which was issued on Dec. 29, 2020, updates previous guidance from February 2020. The updated recommendations are consistent with final labeling guidance for laparoscopic power morcellators, also issued by the FDA on Dec. 29.

Risk of disease spread

Prior evidence suggests that use of uncontained power morcellators in women with malignant uterine tissue can spread disease.

Even among women who do not have malignant uterine tissue, containment is important. The agency noted an association between uncontained power morcellation and the spread of benign uterine tissue, such as parasitic myomas and disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis, which could require additional surgeries.

In 2016, the FDA approved the PneumoLiner, a containment system for isolating uterine tissue that is not suspected of containing cancer.

“While unsuspected cancer can occur at any age, the prevalence of unsuspected cancer in women undergoing hysterectomy for fibroids increases with age such that the benefit-risk profile of using [laparoscopic power morcellators] is worse in older women when compared to younger women,” according to the new labeling guidance. “Also, the surgical technique of en bloc tissue removal eliminates the need to perform morcellation, thereby reducing the risk of iatrogenic dissemination and upstaging of an occult sarcoma. A thorough preoperative screening should be conducted; however, it is important to note that no screening procedure that can reliably detect sarcoma preoperatively has been identified.”

“The FDA will continue to review the latest data and scientific literature on laparoscopic power morcellation, including gathering real-world evidence from patients, providers and others, and encouraging innovation to better detect uterine cancer and develop containment systems for gynecologic surgery,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in a news release. “The FDA seeks to ensure women and their health care providers are fully informed when considering laparoscopic power morcellators for gynecologic surgeries.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency noted that physicians should conduct a thorough preoperative screening and that the devices should only be used for hysterectomies and myomectomies. Clinicians should not use the devices in cases involving uterine malignancy or suspected uterine malignancy.

In addition, clinicians should not use morcellators to remove uterine tissue containing suspected fibroids in women older than 50 years or who are postmenopausal. Nor should the devices be used for women who are “candidates for removal of tissue (en bloc) through the vagina or via a minilaparotomy incision,” the agency said.

The safety communication, which was issued on Dec. 29, 2020, updates previous guidance from February 2020. The updated recommendations are consistent with final labeling guidance for laparoscopic power morcellators, also issued by the FDA on Dec. 29.

Risk of disease spread

Prior evidence suggests that use of uncontained power morcellators in women with malignant uterine tissue can spread disease.

Even among women who do not have malignant uterine tissue, containment is important. The agency noted an association between uncontained power morcellation and the spread of benign uterine tissue, such as parasitic myomas and disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis, which could require additional surgeries.

In 2016, the FDA approved the PneumoLiner, a containment system for isolating uterine tissue that is not suspected of containing cancer.

“While unsuspected cancer can occur at any age, the prevalence of unsuspected cancer in women undergoing hysterectomy for fibroids increases with age such that the benefit-risk profile of using [laparoscopic power morcellators] is worse in older women when compared to younger women,” according to the new labeling guidance. “Also, the surgical technique of en bloc tissue removal eliminates the need to perform morcellation, thereby reducing the risk of iatrogenic dissemination and upstaging of an occult sarcoma. A thorough preoperative screening should be conducted; however, it is important to note that no screening procedure that can reliably detect sarcoma preoperatively has been identified.”

“The FDA will continue to review the latest data and scientific literature on laparoscopic power morcellation, including gathering real-world evidence from patients, providers and others, and encouraging innovation to better detect uterine cancer and develop containment systems for gynecologic surgery,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in a news release. “The FDA seeks to ensure women and their health care providers are fully informed when considering laparoscopic power morcellators for gynecologic surgeries.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency noted that physicians should conduct a thorough preoperative screening and that the devices should only be used for hysterectomies and myomectomies. Clinicians should not use the devices in cases involving uterine malignancy or suspected uterine malignancy.

In addition, clinicians should not use morcellators to remove uterine tissue containing suspected fibroids in women older than 50 years or who are postmenopausal. Nor should the devices be used for women who are “candidates for removal of tissue (en bloc) through the vagina or via a minilaparotomy incision,” the agency said.

The safety communication, which was issued on Dec. 29, 2020, updates previous guidance from February 2020. The updated recommendations are consistent with final labeling guidance for laparoscopic power morcellators, also issued by the FDA on Dec. 29.

Risk of disease spread

Prior evidence suggests that use of uncontained power morcellators in women with malignant uterine tissue can spread disease.

Even among women who do not have malignant uterine tissue, containment is important. The agency noted an association between uncontained power morcellation and the spread of benign uterine tissue, such as parasitic myomas and disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis, which could require additional surgeries.

In 2016, the FDA approved the PneumoLiner, a containment system for isolating uterine tissue that is not suspected of containing cancer.

“While unsuspected cancer can occur at any age, the prevalence of unsuspected cancer in women undergoing hysterectomy for fibroids increases with age such that the benefit-risk profile of using [laparoscopic power morcellators] is worse in older women when compared to younger women,” according to the new labeling guidance. “Also, the surgical technique of en bloc tissue removal eliminates the need to perform morcellation, thereby reducing the risk of iatrogenic dissemination and upstaging of an occult sarcoma. A thorough preoperative screening should be conducted; however, it is important to note that no screening procedure that can reliably detect sarcoma preoperatively has been identified.”

“The FDA will continue to review the latest data and scientific literature on laparoscopic power morcellation, including gathering real-world evidence from patients, providers and others, and encouraging innovation to better detect uterine cancer and develop containment systems for gynecologic surgery,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in a news release. “The FDA seeks to ensure women and their health care providers are fully informed when considering laparoscopic power morcellators for gynecologic surgeries.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer linked to number of oral sex partners

Having oral sex with more than 10 previous partners was associated with a 4.3 times’ greater likelihood of developing human papillomavirus (HPV)–related oropharyngeal cancer, according to new findings.

The study also found that having more partners in a shorter period (i.e., greater oral sex intensity) and starting oral sex at a younger age were associated with higher odds of having HPV-related cancer of the mouth and throat.

The new study, published online on Jan. 11 in Cancer, confirms previous findings and adds more nuance, say the researchers.

Previous studies have demonstrated that oral sex is a strong risk factor for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, which has increased in incidence in recent decades, particularly cancer of the base of the tongue and palatine and lingual tonsils.

“Our research adds more nuance in our understanding of how people acquire oral HPV infection and HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer,” said study author Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore. “It suggests that risk of infection is not only from the number of oral sexual partners but that the timing and type of partner also influence risk.”

The results of the study do not change the clinical care or screening of patients, Dr. D’Souza noted, but the study does add context for patients and providers in understanding, “Why did I get HPV-oropharyngeal cancer?” she said.

“We know that people who develop HPV-oropharyngeal cancer have a wide range of sexual histories, but we do not suggest sexual history be used for screening, as many patients have low-risk sexual histories,” she said. “By chance, it only takes one partner who is infected to acquire the infection, while others who have had many partners by chance do not get exposed, or who are exposed but clear the infection.”

Reinforces the need for vaccination

Approached for comment, Joseph Califano, MD, physician-in-chief at the Moores Cancer Center and director of the Head and Neck Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, noted that similar data have been published before. The novelty here is in the timing and intensity of oral sex. “It’s not new data, but it certainly reinforces what we knew,” he said in an interview.

These new data are not going to change monitoring, he suggested. “It’s not going to change how we screen, because we don’t do population-based screening for oropharyngeal cancer,” Dr. Califano said.

“It does underline the fact that vaccination is really the key to preventing HPV-mediated cancers,” he said.

He pointed out that some data show lower rates of high-risk oral HPV shedding by children who have been appropriately vaccinated.

“This paper really highlights the fact we need to get people vaccinated early, before sexual debut,” he said. “In this case, sexual debut doesn’t necessarily mean intercourse but oral sex, and that’s a different concept of when sex starts.”

These new data “reinforce the fact that early exposure is what we need to focus on,” he said.

Details of the new findings

The current study by Dr. D’Souza and colleagues included 163 patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer who were enrolled in the Papillomavirus Role in Oral Cancer Viral Etiology (PROVE) study. These patients were compared with 345 matched control persons.

All participants completed a behavioral survey and provided a blood sample. For the patients with cancer, a tumor sample was obtained.

The majority of participants were male (85% and 82%), were aged 50-69 years, were currently married or living with a partner, and identified as heterosexual. Case patients were more likely to report a history of sexually transmitted infection than were control participants (P = .003).

Case patients were more likely to have ever performed oral sex compared to control persons (98.8% vs 90.4%; P < .001) and to have performed oral sex at the time of their sexual debut (33.3% of case patients vs 21.4% of control persons; P = .004; odds ratio [OR], 1.8).

Significantly more case patients than control persons reported starting oral sex before they were 18 years old (37.4% of cases vs. 22.6% of controls; P < .001; OR, 3.1), and they had a greater number of lifetime oral sex partners (44.8% of cases and 19.1% of controls reported having more than 10 partners; P < .001; OR, 4.3).

Intensity of oral sexual exposure, which the authors measured by number of partners per 10 years, was also significantly higher among cases than controls (30.8% vs 11.1%; P < .001; OR, 5.6).

After adjustment for confounders (such as the lifetime number of oral sex partners and tobacco use), ever performing oral sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.4), early age of first oral sex encounter (20 years: aOR, 1.8), and oral sex intensity (aOR, 2.8) all remained significantly associated with increased odds of HPV-oropharyngeal cancer.

The type of sexual partner, such as partners who were older (OR, 1.7) and having a partner who engaged in extramarital sex (OR, 1.6), were also associated with increased odds of developing HPV-oropharyngeal cancer. In addition, seropositivity for antibodies to HPV16 E6 (OR, 286) and any HPV16 E protein (E1, E2, E6, E7; OR, 163) were also associated with increased odds of developing the disease.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Dr. D’Souza and Dr. Califano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Having oral sex with more than 10 previous partners was associated with a 4.3 times’ greater likelihood of developing human papillomavirus (HPV)–related oropharyngeal cancer, according to new findings.

The study also found that having more partners in a shorter period (i.e., greater oral sex intensity) and starting oral sex at a younger age were associated with higher odds of having HPV-related cancer of the mouth and throat.

The new study, published online on Jan. 11 in Cancer, confirms previous findings and adds more nuance, say the researchers.

Previous studies have demonstrated that oral sex is a strong risk factor for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, which has increased in incidence in recent decades, particularly cancer of the base of the tongue and palatine and lingual tonsils.

“Our research adds more nuance in our understanding of how people acquire oral HPV infection and HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer,” said study author Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore. “It suggests that risk of infection is not only from the number of oral sexual partners but that the timing and type of partner also influence risk.”

The results of the study do not change the clinical care or screening of patients, Dr. D’Souza noted, but the study does add context for patients and providers in understanding, “Why did I get HPV-oropharyngeal cancer?” she said.

“We know that people who develop HPV-oropharyngeal cancer have a wide range of sexual histories, but we do not suggest sexual history be used for screening, as many patients have low-risk sexual histories,” she said. “By chance, it only takes one partner who is infected to acquire the infection, while others who have had many partners by chance do not get exposed, or who are exposed but clear the infection.”

Reinforces the need for vaccination

Approached for comment, Joseph Califano, MD, physician-in-chief at the Moores Cancer Center and director of the Head and Neck Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, noted that similar data have been published before. The novelty here is in the timing and intensity of oral sex. “It’s not new data, but it certainly reinforces what we knew,” he said in an interview.

These new data are not going to change monitoring, he suggested. “It’s not going to change how we screen, because we don’t do population-based screening for oropharyngeal cancer,” Dr. Califano said.

“It does underline the fact that vaccination is really the key to preventing HPV-mediated cancers,” he said.

He pointed out that some data show lower rates of high-risk oral HPV shedding by children who have been appropriately vaccinated.

“This paper really highlights the fact we need to get people vaccinated early, before sexual debut,” he said. “In this case, sexual debut doesn’t necessarily mean intercourse but oral sex, and that’s a different concept of when sex starts.”

These new data “reinforce the fact that early exposure is what we need to focus on,” he said.

Details of the new findings

The current study by Dr. D’Souza and colleagues included 163 patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer who were enrolled in the Papillomavirus Role in Oral Cancer Viral Etiology (PROVE) study. These patients were compared with 345 matched control persons.

All participants completed a behavioral survey and provided a blood sample. For the patients with cancer, a tumor sample was obtained.

The majority of participants were male (85% and 82%), were aged 50-69 years, were currently married or living with a partner, and identified as heterosexual. Case patients were more likely to report a history of sexually transmitted infection than were control participants (P = .003).

Case patients were more likely to have ever performed oral sex compared to control persons (98.8% vs 90.4%; P < .001) and to have performed oral sex at the time of their sexual debut (33.3% of case patients vs 21.4% of control persons; P = .004; odds ratio [OR], 1.8).

Significantly more case patients than control persons reported starting oral sex before they were 18 years old (37.4% of cases vs. 22.6% of controls; P < .001; OR, 3.1), and they had a greater number of lifetime oral sex partners (44.8% of cases and 19.1% of controls reported having more than 10 partners; P < .001; OR, 4.3).

Intensity of oral sexual exposure, which the authors measured by number of partners per 10 years, was also significantly higher among cases than controls (30.8% vs 11.1%; P < .001; OR, 5.6).

After adjustment for confounders (such as the lifetime number of oral sex partners and tobacco use), ever performing oral sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.4), early age of first oral sex encounter (20 years: aOR, 1.8), and oral sex intensity (aOR, 2.8) all remained significantly associated with increased odds of HPV-oropharyngeal cancer.

The type of sexual partner, such as partners who were older (OR, 1.7) and having a partner who engaged in extramarital sex (OR, 1.6), were also associated with increased odds of developing HPV-oropharyngeal cancer. In addition, seropositivity for antibodies to HPV16 E6 (OR, 286) and any HPV16 E protein (E1, E2, E6, E7; OR, 163) were also associated with increased odds of developing the disease.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Dr. D’Souza and Dr. Califano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Having oral sex with more than 10 previous partners was associated with a 4.3 times’ greater likelihood of developing human papillomavirus (HPV)–related oropharyngeal cancer, according to new findings.

The study also found that having more partners in a shorter period (i.e., greater oral sex intensity) and starting oral sex at a younger age were associated with higher odds of having HPV-related cancer of the mouth and throat.

The new study, published online on Jan. 11 in Cancer, confirms previous findings and adds more nuance, say the researchers.

Previous studies have demonstrated that oral sex is a strong risk factor for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, which has increased in incidence in recent decades, particularly cancer of the base of the tongue and palatine and lingual tonsils.

“Our research adds more nuance in our understanding of how people acquire oral HPV infection and HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer,” said study author Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore. “It suggests that risk of infection is not only from the number of oral sexual partners but that the timing and type of partner also influence risk.”

The results of the study do not change the clinical care or screening of patients, Dr. D’Souza noted, but the study does add context for patients and providers in understanding, “Why did I get HPV-oropharyngeal cancer?” she said.

“We know that people who develop HPV-oropharyngeal cancer have a wide range of sexual histories, but we do not suggest sexual history be used for screening, as many patients have low-risk sexual histories,” she said. “By chance, it only takes one partner who is infected to acquire the infection, while others who have had many partners by chance do not get exposed, or who are exposed but clear the infection.”

Reinforces the need for vaccination

Approached for comment, Joseph Califano, MD, physician-in-chief at the Moores Cancer Center and director of the Head and Neck Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, noted that similar data have been published before. The novelty here is in the timing and intensity of oral sex. “It’s not new data, but it certainly reinforces what we knew,” he said in an interview.

These new data are not going to change monitoring, he suggested. “It’s not going to change how we screen, because we don’t do population-based screening for oropharyngeal cancer,” Dr. Califano said.

“It does underline the fact that vaccination is really the key to preventing HPV-mediated cancers,” he said.

He pointed out that some data show lower rates of high-risk oral HPV shedding by children who have been appropriately vaccinated.

“This paper really highlights the fact we need to get people vaccinated early, before sexual debut,” he said. “In this case, sexual debut doesn’t necessarily mean intercourse but oral sex, and that’s a different concept of when sex starts.”

These new data “reinforce the fact that early exposure is what we need to focus on,” he said.

Details of the new findings

The current study by Dr. D’Souza and colleagues included 163 patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer who were enrolled in the Papillomavirus Role in Oral Cancer Viral Etiology (PROVE) study. These patients were compared with 345 matched control persons.

All participants completed a behavioral survey and provided a blood sample. For the patients with cancer, a tumor sample was obtained.

The majority of participants were male (85% and 82%), were aged 50-69 years, were currently married or living with a partner, and identified as heterosexual. Case patients were more likely to report a history of sexually transmitted infection than were control participants (P = .003).

Case patients were more likely to have ever performed oral sex compared to control persons (98.8% vs 90.4%; P < .001) and to have performed oral sex at the time of their sexual debut (33.3% of case patients vs 21.4% of control persons; P = .004; odds ratio [OR], 1.8).

Significantly more case patients than control persons reported starting oral sex before they were 18 years old (37.4% of cases vs. 22.6% of controls; P < .001; OR, 3.1), and they had a greater number of lifetime oral sex partners (44.8% of cases and 19.1% of controls reported having more than 10 partners; P < .001; OR, 4.3).

Intensity of oral sexual exposure, which the authors measured by number of partners per 10 years, was also significantly higher among cases than controls (30.8% vs 11.1%; P < .001; OR, 5.6).

After adjustment for confounders (such as the lifetime number of oral sex partners and tobacco use), ever performing oral sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.4), early age of first oral sex encounter (20 years: aOR, 1.8), and oral sex intensity (aOR, 2.8) all remained significantly associated with increased odds of HPV-oropharyngeal cancer.

The type of sexual partner, such as partners who were older (OR, 1.7) and having a partner who engaged in extramarital sex (OR, 1.6), were also associated with increased odds of developing HPV-oropharyngeal cancer. In addition, seropositivity for antibodies to HPV16 E6 (OR, 286) and any HPV16 E protein (E1, E2, E6, E7; OR, 163) were also associated with increased odds of developing the disease.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Dr. D’Souza and Dr. Califano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Home pregnancy tests—Is ectopic always on your mind?

CASE Unidentified ectopic pregnancy leads to rupture*

A 33-year-old woman (G1 P0010) with 2 positive home pregnancy tests presents to the emergency department (ED) reporting intermittent vaginal bleeding for 3 days. Her last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago, but she reports that her menses are always irregular. She has a history of asymptomatic chlamydia, as well as spontaneous abortion 2 years prior. At present, she denies abdominal pain or vaginal discharge.

Upon examination her vital signs are: temperature, 98.3 °F; pulse, 112 bpm, with a resting rate of 16 bpm; blood pressure (BP), 142/91 mm Hg; pulse O2, 99%; height, 4’ 3”; weight, 115 lb. Her labs are: hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 38%; serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 236 mIU/mL. Upon pelvic examination, no active bleeding is noted. She agrees to be followed up by her gynecologist and is given a prescription for serum hCG in 2 days. She is instructed to return to the ED should she have pain or increased vaginal bleeding.

Three days later, the patient follows up with her gynecologist reporting mild cramping. She notes having had an episode of heavy vaginal bleeding and a “weakly positive” home pregnancy test. Transvaginal ultrasonography notes endometrial thickness 0.59 mm and unremarkable adnexa. A urine pregnancy test performed in the office is positive; urinalysis is positive for nitrites. With the bleeding slowed, the gynecologist’s overall impression is that the patient has undergone complete spontaneous abortion. She prescribes Macrobid for the urinary tract infection. She does not obtain the ED-prescribed serum HCG levels, as she feels, since complete spontaneous abortion has occurred there is no need to obtain a follow-up serum HCG.

Five days later, the patient returns to the ED reporting abdominal pain after eating. Fever and productive cough of 2 days are noted. The patient states that she had a recent miscarriage. The overall impression of the patient’s condition is bronchitis, and it is noted on the patient’s record, “unlikely ectopic pregnancy and pregnancy test may be false positive,” hence a pregnancy test is not ordered. Examination reveals mild suprapubic tenderness with no rebound; no pelvic exam is performed. The patient is instructed to follow up with a health care clinic within a week, and to return to the ED with severe abdominal pain, higher fever, or any new concerning symptoms. A Zithromax Z-pak is prescribed.

Four days later, the patient is brought by ambulance to the ED of the local major medical center with severe abdominal pain involving the right lower quadrant. She states that she had a miscarriage 3 weeks prior and was recently treated for bronchitis. She has dizziness when standing. Her vital signs are: temperature, 97.8 °F; heart rate, 95 bpm; BP, 72/48 mm Hg; pulse O2, 100%. She reports her abdominal pain to be 6/10.

The patient is given a Lactated Ringer’s bolus of 1,000 mL for a hypotensive episode. Computed tomography is obtained and notes, “low attenuation in the left adnexa with a dilated fallopian tube.” A large heterogeneous collection of fluid in the pelvis is noted with active extravasation, consistent with an “acute bleed.”

The patient is brought to the operating room with a diagnosis of probable ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Intraoperatively she is noted to have a right ruptured ectopic and left tubo-ovarian abscess. The surgeon proceeds with right salpingectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy. Three liters of hemoperitoneum is found.

She is followed postoperatively with serum hCG until levels are negative. Her postoperative course is uneventful. Her only future option for pregnancy is through assisted reproductive technology (ART) with in vitro fertilization (IVF). The patient sues the gynecologist and second ED physician for presumed inappropriate assessment for ectopic pregnancy.

*The “facts” of this case are a composite, drawn from several cases to illustrate medical and legal issues. The statement of facts should be considered hypothetical.

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?...

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

A defense verdict is returned.

Medical considerations

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 2% of all pregnancies, with a higher incidence (about 4%) among infertility patients.1 Up to 10% of ectopic pregnancies have no symptoms.2

Clinical presentations. Classic signs of ectopic pregnancy include:

- abdominal pain

- vaginal bleeding

- late menses (often noted).

A recent case of ectopic pregnancy presenting with chest pain was reported.3 Clinicians must never lose site of the fact that ectopic pregnancy is the most common cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester, with an incidence of 1% to 10% of all first-trimester deaths.4

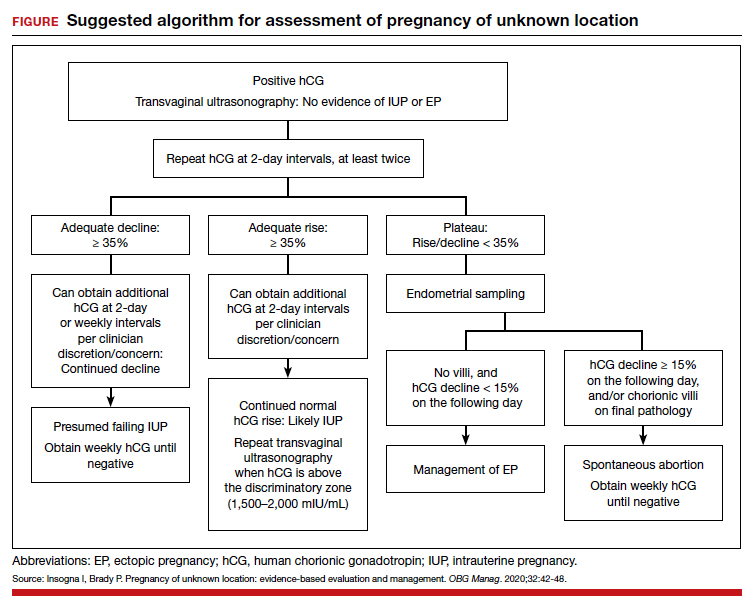

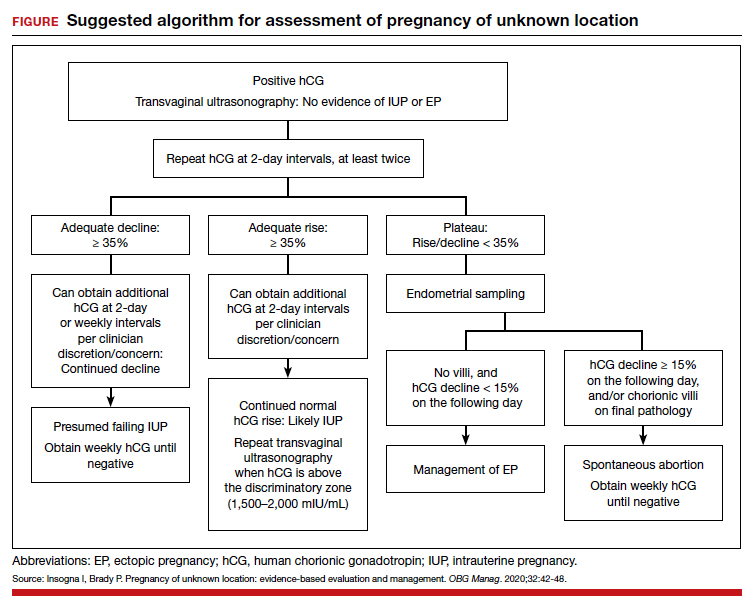

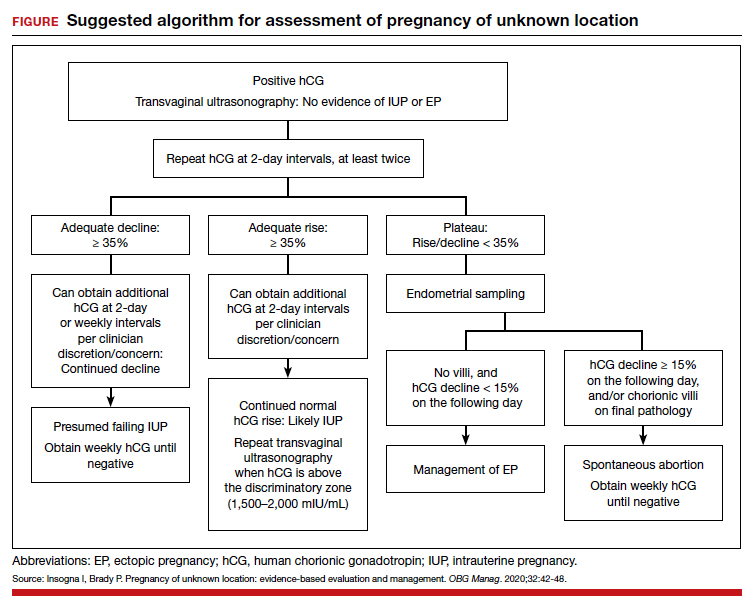

Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, as demonstrated in the opening case. “The silent epidemic of chlamydia” comes to mind, and tobacco smoking can adversely affect tubal cilia, as can pelvic adhesions and/or prior tubal surgery. All of these factors can predispose a patient to ectopic pregnancy; in addition, intrauterine devices, endometriosis, tubal ligation (or ligation reversal), all can set the stage for an ectopic pregnancy.5 Appropriate serum hCG monitoring during early pregnancy can assist in sorting out pregnancies of unknown location (PUL; FIGURE). First trimester ultrasonography, at 5 weeks gestation, usually identifies early intrauterine gestation.

Imaging. With regard to pelvic sonography, the earliest sign of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is a sac eccentrically located in the decidua.6 As the IUP progresses, it becomes equated with a “double decidual sign,” with double rings of tissue around the sac.6 If the pregnancy is located in an adnexal mass, it is frequently inhomogeneous or noncystic in appearance (ie, “the blob” sign); the positive predictive value (PPV) is 96%.2 The PPV of transvaginal ultrasound is 80%, as paratubal, paraovarian, ovarian cyst, and hydrosalpinx can affect the interpretation.7

Heterotopic pregnancy includes an intrauterine gestation and an ectopic pregnancy. This presentation includes the presence of a “pseudosac” in the endometrial cavity plus an extrauterine gestation. Heterotopic pregnancies have become somewhat more common as ART/IVF has unfolded, especially prior to the predominance of single embryo transfer.

Managing ectopic pregnancy

For cases of early pregnancy complicated by intermittent bleeding and/or pain, monitoring with serum hCG levels at 48-hour intervals to distinguish a viable IUP from an abnormal IUP or an ectopic is appropriate. The “discriminatory zone” collates serum hCG levels with findings on ultrasonography. Specific lower limits of serum hCG levels are not clear cut, with recommendations of 3,500 mIU/mL to provide sonographic evidence of an intrauterine gestation “to avoid misdiagnosis and possible interruption of intrauterine pregnancy,” as conveyed in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018 practice bulletin.8 Serum progesterone levels also have been suggested to complement hCG levels; a progesterone level of <20 nmol/L is consistent with an abnormal pregnancy, whereas levels >25 nmol/L are suggestive of a viable pregnancy.2 Inhibin A levels also have been suggested to be helpful, but they are not an ideal monitoring tool.

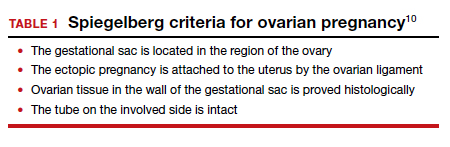

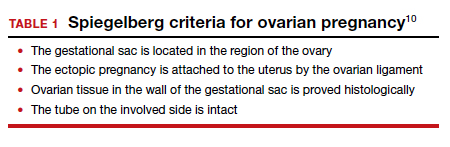

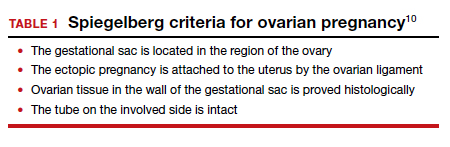

While most ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube, other locations also can be abdominal or ovarian. In addition, cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can occur and often is associated with delay in diagnosis and greater morbidity due to such delay.9 With regard to ovarian ectopic, Spiegelberg criteria are established for diagnosis (TABLE 1).10

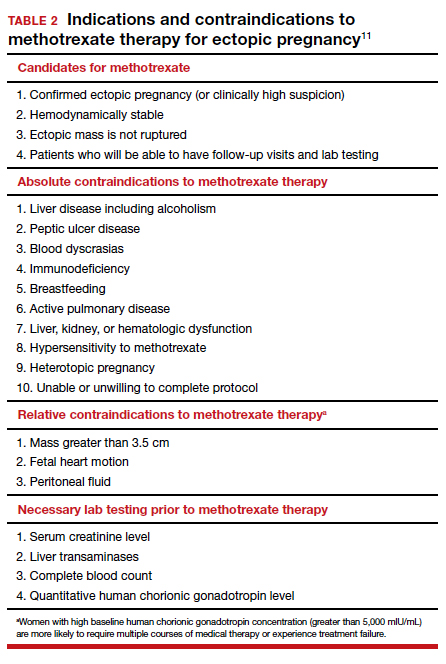

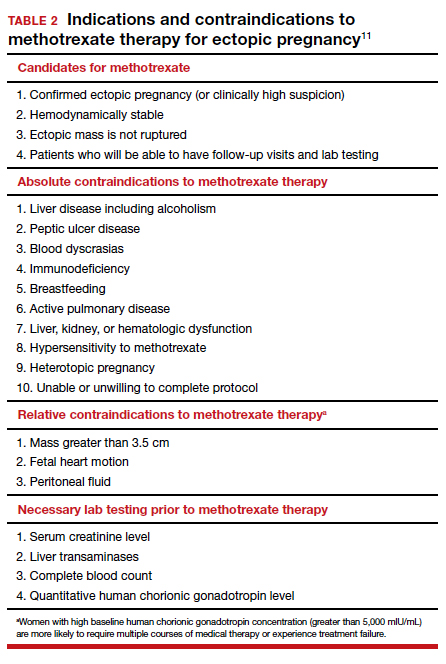

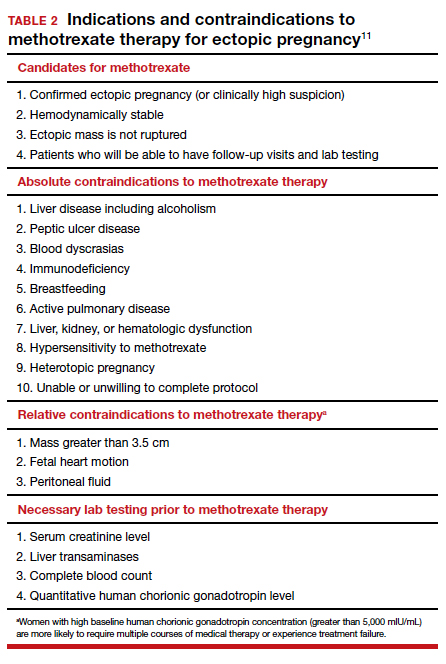

Appropriate management of an ectopic pregnancy is dependent upon the gestational age, serum hCG levels, and imaging findings, as well as the patient’s symptoms and exam findings. Treatment is established in large part on a case-by-case basis and includes, for early pregnancy, expectant management and use of methotrexate (TABLE 2).11 Dilation and curettage may be used to identify the pregnancy’s location when the serum hCG level is below 2,000 mIU/mL and there is no evidence of an IUP on ultrasound. Surgical treatment can include minimally invasive salpingostomy or salpingectomy and, depending on circumstance, laparotomy may be indicated.

Fertility following ectopic pregnancy varies and is affected by location, treatment, predisposing factors, total number of ectopic pregnancies, and other factors. Ectopic pregnancy, although rare, also can occur with use of IVF. Humans are not unique with regard to ectopic pregnancies, as they also occur in sheep.12

Continue to: Legal perspective...

Legal perspective

Lawsuits related to ectopic pregnancy are not a new phenomenon. In fact, in 1897, a physician in Ohio who misdiagnosed an “extrauterine pregnancy” as appendicitis was the center of a malpractice lawsuit.13 Unrecognized or mishandled ectopic pregnancy can result in serious injuries—in the range of 1% to 10% (see above) of maternal deaths are related to ectopic pregnancy.14 Ectopic pregnancy cases, therefore, have been the subject of substantial litigation over the years. An informal, noncomprehensive review of malpractice lawsuits brought from 2000 to 2019, found more than 300 ectopic pregnancy cases. Given the large number of malpractice claims against ObGyns,15 ectopic pregnancy cases are only a small portion of all ObGyn malpractice cases.16

A common claim: negligent diagnosis or treatment

The most common basis for lawsuits in cases of ectopic pregnancy is the clinician’s negligent failure to properly diagnose the ectopic nature of the pregnancy. There are also a number of cases claiming negligent treatment of an identified ectopic pregnancy. Not every missed diagnosis, or unsuccessful treatment, leads to liability, of course. It is only when a diagnosis or treatment fails to meet the standard of care within the profession that there should be liability. That standard of care is generally defined by what a reasonably prudent physician would do under the circumstances. Expert witnesses, who are familiar with the standard of practice within the specialty, are usually necessary to establish what that practice is. Both the plaintiff and the defense obtain experts, the former to prove what the standard of care is and that the standard was not met in the case at hand. The defense experts are usually arguing that the standard of care was met.17 Inadequate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy or other condition may arise from a failure to take a sufficient history, conduct an appropriately thorough physical examination, recognize any of the symptoms that would suggest it is present, use and conduct ultrasound correctly, or follow-up appropriately with additional testing.18

A malpractice claim of negligent treatment can involve any the following circumstances19:

- failure to establish an appropriate treatment plan

- prescribing inappropriate medications for the patient (eg, methotrexate, when it is contraindicated)

- delivering the wrong medication or the wrong amount of the right medication

- performing a procedure badly

- undertaking a new treatment without adequate instruction and preparation.

Given the nature and risks of ectopic pregnancy, ongoing, frequent contact with the patient is essential from the point at which the condition is suspected. The greater the risk of harm (probability or consequence), the more careful any professional ought to be. Because ectopic pregnancy is not an uncommon occurrence, and because it can have devastating effects, including death, a reasonably prudent practitioner would be especially aware of the clinical presentations discussed above.20 In the opening case, the treatment plan was not well documented.

Negligence must lead to patient harm. In addition to negligence (proving that the physician did not act in accordance with the standard of care), to prevail in a malpractice case, the plaintiff-patient must prove that the negligence caused the injury, or worsened it. If the failure to make a diagnosis would not have made any difference in a harm the patient suffered, there are no damages and no liability. Suppose, for example, that a physician negligently failed to diagnose ectopic pregnancy, but performed surgery expecting to find the misdiagnosed condition. In the course of the surgery, however, the surgeon discovered and appropriately treated the ectopic pregnancy. (A version of this happened in the old 19th century case mentioned above.) The negligence of the physician did not cause harm, so there are no damages and no liability.

Continue to: Informed consent is vital...

Informed consent is vital

A part of malpractice is informed consent (or the absence of it)—issues that can arise in any medical care.21 It is wise to pay particular attention in cases where the nature of the illness is unknown, and where there are significant uncertainties and the nature of testing and treatment may change substantially over a period of a few days or few weeks. As always, informed consent should include a discussion of what process or procedure is proposed, its risks and benefits, alternative approaches that might be available, and the risk of doing nothing. Frequently, the uncertainty of ectopic pregnancy complicates the informed consent process.22

Because communication with the patient is an essential function of informed consent, the consent process should productively be used in PUL and similar cases to inform the patient about the uncertainty, and the testing and (nonsurgical) treatment that will occur. This is an opportunity to reinforce the message that the patient must maintain ongoing communication with the physician’s office about changes in her condition, and appear for each appointment scheduled. If more invasive procedures—notably surgery—become required, a separate consent process should be completed, because the risks and considerations are now meaningfully different than when treatment began. As a general matter, any possible treatment that may result in infertility or reduced reproductive capacity should specifically be included in the consent process.

In the hypothetical case, the gynecologist failed to obtain a follow-up serum hCG level. In addition, the record did not reflect ectopic pregnancy in the differential diagnosis. As noted above, the patient had predisposing factors for an ectopic pregnancy. The physician should have acknowledged the history of sexually transmitted disease predisposing her to an ectopic pregnancy. Monitoring of serum hCG levels until they are negative is appropriate with ectopic, or presumed ectopic, pregnancy management. Appropriate monitoring did not occur in this case. Each of these errors (following up on serum hCG levels and the inadequacy of notations about the possibility of ectopic pregnancy) seem inconsistent with the usual standard of care. Furthermore, as a result of the outcome, the only future option for the patient to pursue pregnancy was IVF.

Other legal issues

There are a number of other legal issues that are associated with the topic of ectopic pregnancy. There is evidence, for example, that Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals treat ectopic pregnancies differently,23 which may reflect different views on taking a life or the use of methotrexate and its association with abortion.24 In addition, the possibility of an increase in future ectopic pregnancies is one of the “risks” of abortion that pro-life organizations have pushed to see included in abortion informed consent.25 This has led some commentators to conclude that some Catholic hospitals violate federal law in managing ectopic pregnancy. There is also evidence of “overwhelming rates of medical misinformation on pregnancy center websites, including a link between abortion and ectopic pregnancy.”26

The fact that cesarean deliveries are related to an increased risk for ectopic pregnancy (because of the risk of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy) also has been cited as information that should play a role in the consent process for cesarean delivery.27 In terms of liability, failed tubal ligation leads to a 33% risk of ectopic pregnancy.28 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is also commonly included in surrogacy contracts.29

Why the outcome was for the defense

The opening hypothetical case illustrates some of the uncertainties of medical malpractice cases. As noted, there appeared a deviation from the usual standard of care, particularly the failure to follow up on the serum hCG level. The weakness in the medical record, failing to note the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, also was probably an error but, apparently, the court felt that this did not result in any harm to the patient.

The question arises of how there would be a defense verdict in light of the failure to track consecutive serum hCG levels. A speculative explanation is that there are many uncertainties in most lawsuits. Procedural problems may result in a case being limited, expert witnesses are essential to both the plaintiff and defense, with the quality of their review and testimony possibly uneven. Judges and juries may rely on one expert witness rather than another, juries vary, and the quality of advocacy differs. Any of these situations can contribute to the unpredictability of the outcome of a case. In the case above, the liability was somewhat uncertain, and the various other factors tipped in favor of a defense verdict. ●

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1990‒1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:46-48.

- Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T. Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;20:250-261.

- Dichter E, Espinosa J, Baird J, Lucerna A. An unusual emergency department case: ruptured ectopic pregnancy presenting as chest pain. World J Emerg Med. 2017;8:71-73.

- Cecchino GN, Araujo E, Elito J. Methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: when and how. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:417- 423.

- Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Cracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic firsttrimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:36-43.

- Carusi D. Pregnancy of unknown location: evaluation and management. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:95-100.

- Barnhart KT, Fay CA, Suescum M, et al. Clinical factors affecting the accuracy of ultrasonography in symptomatic first-trimester pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:299-306.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin No. 193: tubal ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e91-e103.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10-year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3224-3230.

- Spiegelberg O. Zur casuistic der ovarial schwangerschaft. Arch Gynecol. 1978;13:73.

- OB Hospitalist Group. Methotrexate use for ectopic pregnancies guidelines. https://www.obhg.com/wp-content /uploads/2020/01/Methotrexate-Use-for-EctopicPregnancies_2016-updates.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- Brozos C, Kargiannis I, Kiossis E, et al. Ectopic pregnancy through a caesarean scar in a ewe. N Z Vet J. 2013;61:373-375.

- Tucker v. Gillette, 12 Ohio Cir. Dec. 401 (Cir. Ct. 1901).

- Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:366-373.

- Matthews LR, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Reproductive surgery malpractice patterns. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:e42-e43.

- Kim B. The impact of malpractice risk on the use of obstetrics procedures. J Legal Studies. 2006;36:S79-S120.

- Abinader R, Warsof S. Complications involving obstetrical ultrasound. In: Warsof S, Shwayder JM, eds. Legal Concepts and Best Practices in Obstetrics: The Nuts and Bolts Guide to Mitigating Risk. 2019;45-48.

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:837-843.

- Shwayder JM. IUP diagnosed and treated as ectopic: How bad can it get? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2019;64:49-46.

- Kaplan AI. Should this ectopic pregnancy have been diagnosed earlier? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:53.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee opinion 439: informed consent. Reaffirmed 2015. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2009/08 /informed-consent. Accessed December 9, 2020.

- Shwayder JM. Liability in ob/gyn ultrasound. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:32-49.

- Fisher LN. Institutional religious exemptions: a balancing approach. BYU Law Review. 2014;415-444.

- Makdisi J. Aquinas’s prohibition of killing reconsidered. J Catholic Legal Stud. 2019:57:67-128.

- Franzonello A. Remarks of Anna Franzonello. Alb Law J Sci Tech. 2012;23:519-530.

- Malcolm HE. Pregnancy centers and the limits of mandated disclosure. Columbia Law Rev. 2019;119:1133-1168.

- Kukura E. Contested care: the limitations of evidencebased maternity care reform. Berkeley J Gender Law Justice. 2016;31:241-298.

- Donley G. Contraceptive equity: curing the sex discrimination in the ACA’s mandate. Alabama Law Rev. 2019;71:499-560.

- Berk H. Savvy surrogates and rock star parents: compensation provisions, contracting practices, and the value of womb work. Law Social Inquiry. 2020;45:398-431.

CASE Unidentified ectopic pregnancy leads to rupture*

A 33-year-old woman (G1 P0010) with 2 positive home pregnancy tests presents to the emergency department (ED) reporting intermittent vaginal bleeding for 3 days. Her last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago, but she reports that her menses are always irregular. She has a history of asymptomatic chlamydia, as well as spontaneous abortion 2 years prior. At present, she denies abdominal pain or vaginal discharge.

Upon examination her vital signs are: temperature, 98.3 °F; pulse, 112 bpm, with a resting rate of 16 bpm; blood pressure (BP), 142/91 mm Hg; pulse O2, 99%; height, 4’ 3”; weight, 115 lb. Her labs are: hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 38%; serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 236 mIU/mL. Upon pelvic examination, no active bleeding is noted. She agrees to be followed up by her gynecologist and is given a prescription for serum hCG in 2 days. She is instructed to return to the ED should she have pain or increased vaginal bleeding.

Three days later, the patient follows up with her gynecologist reporting mild cramping. She notes having had an episode of heavy vaginal bleeding and a “weakly positive” home pregnancy test. Transvaginal ultrasonography notes endometrial thickness 0.59 mm and unremarkable adnexa. A urine pregnancy test performed in the office is positive; urinalysis is positive for nitrites. With the bleeding slowed, the gynecologist’s overall impression is that the patient has undergone complete spontaneous abortion. She prescribes Macrobid for the urinary tract infection. She does not obtain the ED-prescribed serum HCG levels, as she feels, since complete spontaneous abortion has occurred there is no need to obtain a follow-up serum HCG.

Five days later, the patient returns to the ED reporting abdominal pain after eating. Fever and productive cough of 2 days are noted. The patient states that she had a recent miscarriage. The overall impression of the patient’s condition is bronchitis, and it is noted on the patient’s record, “unlikely ectopic pregnancy and pregnancy test may be false positive,” hence a pregnancy test is not ordered. Examination reveals mild suprapubic tenderness with no rebound; no pelvic exam is performed. The patient is instructed to follow up with a health care clinic within a week, and to return to the ED with severe abdominal pain, higher fever, or any new concerning symptoms. A Zithromax Z-pak is prescribed.

Four days later, the patient is brought by ambulance to the ED of the local major medical center with severe abdominal pain involving the right lower quadrant. She states that she had a miscarriage 3 weeks prior and was recently treated for bronchitis. She has dizziness when standing. Her vital signs are: temperature, 97.8 °F; heart rate, 95 bpm; BP, 72/48 mm Hg; pulse O2, 100%. She reports her abdominal pain to be 6/10.

The patient is given a Lactated Ringer’s bolus of 1,000 mL for a hypotensive episode. Computed tomography is obtained and notes, “low attenuation in the left adnexa with a dilated fallopian tube.” A large heterogeneous collection of fluid in the pelvis is noted with active extravasation, consistent with an “acute bleed.”

The patient is brought to the operating room with a diagnosis of probable ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Intraoperatively she is noted to have a right ruptured ectopic and left tubo-ovarian abscess. The surgeon proceeds with right salpingectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy. Three liters of hemoperitoneum is found.

She is followed postoperatively with serum hCG until levels are negative. Her postoperative course is uneventful. Her only future option for pregnancy is through assisted reproductive technology (ART) with in vitro fertilization (IVF). The patient sues the gynecologist and second ED physician for presumed inappropriate assessment for ectopic pregnancy.

*The “facts” of this case are a composite, drawn from several cases to illustrate medical and legal issues. The statement of facts should be considered hypothetical.

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?...

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

A defense verdict is returned.

Medical considerations

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 2% of all pregnancies, with a higher incidence (about 4%) among infertility patients.1 Up to 10% of ectopic pregnancies have no symptoms.2

Clinical presentations. Classic signs of ectopic pregnancy include:

- abdominal pain

- vaginal bleeding

- late menses (often noted).

A recent case of ectopic pregnancy presenting with chest pain was reported.3 Clinicians must never lose site of the fact that ectopic pregnancy is the most common cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester, with an incidence of 1% to 10% of all first-trimester deaths.4

Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, as demonstrated in the opening case. “The silent epidemic of chlamydia” comes to mind, and tobacco smoking can adversely affect tubal cilia, as can pelvic adhesions and/or prior tubal surgery. All of these factors can predispose a patient to ectopic pregnancy; in addition, intrauterine devices, endometriosis, tubal ligation (or ligation reversal), all can set the stage for an ectopic pregnancy.5 Appropriate serum hCG monitoring during early pregnancy can assist in sorting out pregnancies of unknown location (PUL; FIGURE). First trimester ultrasonography, at 5 weeks gestation, usually identifies early intrauterine gestation.

Imaging. With regard to pelvic sonography, the earliest sign of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is a sac eccentrically located in the decidua.6 As the IUP progresses, it becomes equated with a “double decidual sign,” with double rings of tissue around the sac.6 If the pregnancy is located in an adnexal mass, it is frequently inhomogeneous or noncystic in appearance (ie, “the blob” sign); the positive predictive value (PPV) is 96%.2 The PPV of transvaginal ultrasound is 80%, as paratubal, paraovarian, ovarian cyst, and hydrosalpinx can affect the interpretation.7

Heterotopic pregnancy includes an intrauterine gestation and an ectopic pregnancy. This presentation includes the presence of a “pseudosac” in the endometrial cavity plus an extrauterine gestation. Heterotopic pregnancies have become somewhat more common as ART/IVF has unfolded, especially prior to the predominance of single embryo transfer.

Managing ectopic pregnancy

For cases of early pregnancy complicated by intermittent bleeding and/or pain, monitoring with serum hCG levels at 48-hour intervals to distinguish a viable IUP from an abnormal IUP or an ectopic is appropriate. The “discriminatory zone” collates serum hCG levels with findings on ultrasonography. Specific lower limits of serum hCG levels are not clear cut, with recommendations of 3,500 mIU/mL to provide sonographic evidence of an intrauterine gestation “to avoid misdiagnosis and possible interruption of intrauterine pregnancy,” as conveyed in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018 practice bulletin.8 Serum progesterone levels also have been suggested to complement hCG levels; a progesterone level of <20 nmol/L is consistent with an abnormal pregnancy, whereas levels >25 nmol/L are suggestive of a viable pregnancy.2 Inhibin A levels also have been suggested to be helpful, but they are not an ideal monitoring tool.

While most ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube, other locations also can be abdominal or ovarian. In addition, cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can occur and often is associated with delay in diagnosis and greater morbidity due to such delay.9 With regard to ovarian ectopic, Spiegelberg criteria are established for diagnosis (TABLE 1).10

Appropriate management of an ectopic pregnancy is dependent upon the gestational age, serum hCG levels, and imaging findings, as well as the patient’s symptoms and exam findings. Treatment is established in large part on a case-by-case basis and includes, for early pregnancy, expectant management and use of methotrexate (TABLE 2).11 Dilation and curettage may be used to identify the pregnancy’s location when the serum hCG level is below 2,000 mIU/mL and there is no evidence of an IUP on ultrasound. Surgical treatment can include minimally invasive salpingostomy or salpingectomy and, depending on circumstance, laparotomy may be indicated.

Fertility following ectopic pregnancy varies and is affected by location, treatment, predisposing factors, total number of ectopic pregnancies, and other factors. Ectopic pregnancy, although rare, also can occur with use of IVF. Humans are not unique with regard to ectopic pregnancies, as they also occur in sheep.12

Continue to: Legal perspective...

Legal perspective

Lawsuits related to ectopic pregnancy are not a new phenomenon. In fact, in 1897, a physician in Ohio who misdiagnosed an “extrauterine pregnancy” as appendicitis was the center of a malpractice lawsuit.13 Unrecognized or mishandled ectopic pregnancy can result in serious injuries—in the range of 1% to 10% (see above) of maternal deaths are related to ectopic pregnancy.14 Ectopic pregnancy cases, therefore, have been the subject of substantial litigation over the years. An informal, noncomprehensive review of malpractice lawsuits brought from 2000 to 2019, found more than 300 ectopic pregnancy cases. Given the large number of malpractice claims against ObGyns,15 ectopic pregnancy cases are only a small portion of all ObGyn malpractice cases.16

A common claim: negligent diagnosis or treatment

The most common basis for lawsuits in cases of ectopic pregnancy is the clinician’s negligent failure to properly diagnose the ectopic nature of the pregnancy. There are also a number of cases claiming negligent treatment of an identified ectopic pregnancy. Not every missed diagnosis, or unsuccessful treatment, leads to liability, of course. It is only when a diagnosis or treatment fails to meet the standard of care within the profession that there should be liability. That standard of care is generally defined by what a reasonably prudent physician would do under the circumstances. Expert witnesses, who are familiar with the standard of practice within the specialty, are usually necessary to establish what that practice is. Both the plaintiff and the defense obtain experts, the former to prove what the standard of care is and that the standard was not met in the case at hand. The defense experts are usually arguing that the standard of care was met.17 Inadequate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy or other condition may arise from a failure to take a sufficient history, conduct an appropriately thorough physical examination, recognize any of the symptoms that would suggest it is present, use and conduct ultrasound correctly, or follow-up appropriately with additional testing.18

A malpractice claim of negligent treatment can involve any the following circumstances19:

- failure to establish an appropriate treatment plan

- prescribing inappropriate medications for the patient (eg, methotrexate, when it is contraindicated)

- delivering the wrong medication or the wrong amount of the right medication

- performing a procedure badly

- undertaking a new treatment without adequate instruction and preparation.

Given the nature and risks of ectopic pregnancy, ongoing, frequent contact with the patient is essential from the point at which the condition is suspected. The greater the risk of harm (probability or consequence), the more careful any professional ought to be. Because ectopic pregnancy is not an uncommon occurrence, and because it can have devastating effects, including death, a reasonably prudent practitioner would be especially aware of the clinical presentations discussed above.20 In the opening case, the treatment plan was not well documented.

Negligence must lead to patient harm. In addition to negligence (proving that the physician did not act in accordance with the standard of care), to prevail in a malpractice case, the plaintiff-patient must prove that the negligence caused the injury, or worsened it. If the failure to make a diagnosis would not have made any difference in a harm the patient suffered, there are no damages and no liability. Suppose, for example, that a physician negligently failed to diagnose ectopic pregnancy, but performed surgery expecting to find the misdiagnosed condition. In the course of the surgery, however, the surgeon discovered and appropriately treated the ectopic pregnancy. (A version of this happened in the old 19th century case mentioned above.) The negligence of the physician did not cause harm, so there are no damages and no liability.

Continue to: Informed consent is vital...

Informed consent is vital

A part of malpractice is informed consent (or the absence of it)—issues that can arise in any medical care.21 It is wise to pay particular attention in cases where the nature of the illness is unknown, and where there are significant uncertainties and the nature of testing and treatment may change substantially over a period of a few days or few weeks. As always, informed consent should include a discussion of what process or procedure is proposed, its risks and benefits, alternative approaches that might be available, and the risk of doing nothing. Frequently, the uncertainty of ectopic pregnancy complicates the informed consent process.22

Because communication with the patient is an essential function of informed consent, the consent process should productively be used in PUL and similar cases to inform the patient about the uncertainty, and the testing and (nonsurgical) treatment that will occur. This is an opportunity to reinforce the message that the patient must maintain ongoing communication with the physician’s office about changes in her condition, and appear for each appointment scheduled. If more invasive procedures—notably surgery—become required, a separate consent process should be completed, because the risks and considerations are now meaningfully different than when treatment began. As a general matter, any possible treatment that may result in infertility or reduced reproductive capacity should specifically be included in the consent process.

In the hypothetical case, the gynecologist failed to obtain a follow-up serum hCG level. In addition, the record did not reflect ectopic pregnancy in the differential diagnosis. As noted above, the patient had predisposing factors for an ectopic pregnancy. The physician should have acknowledged the history of sexually transmitted disease predisposing her to an ectopic pregnancy. Monitoring of serum hCG levels until they are negative is appropriate with ectopic, or presumed ectopic, pregnancy management. Appropriate monitoring did not occur in this case. Each of these errors (following up on serum hCG levels and the inadequacy of notations about the possibility of ectopic pregnancy) seem inconsistent with the usual standard of care. Furthermore, as a result of the outcome, the only future option for the patient to pursue pregnancy was IVF.

Other legal issues

There are a number of other legal issues that are associated with the topic of ectopic pregnancy. There is evidence, for example, that Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals treat ectopic pregnancies differently,23 which may reflect different views on taking a life or the use of methotrexate and its association with abortion.24 In addition, the possibility of an increase in future ectopic pregnancies is one of the “risks” of abortion that pro-life organizations have pushed to see included in abortion informed consent.25 This has led some commentators to conclude that some Catholic hospitals violate federal law in managing ectopic pregnancy. There is also evidence of “overwhelming rates of medical misinformation on pregnancy center websites, including a link between abortion and ectopic pregnancy.”26

The fact that cesarean deliveries are related to an increased risk for ectopic pregnancy (because of the risk of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy) also has been cited as information that should play a role in the consent process for cesarean delivery.27 In terms of liability, failed tubal ligation leads to a 33% risk of ectopic pregnancy.28 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is also commonly included in surrogacy contracts.29

Why the outcome was for the defense

The opening hypothetical case illustrates some of the uncertainties of medical malpractice cases. As noted, there appeared a deviation from the usual standard of care, particularly the failure to follow up on the serum hCG level. The weakness in the medical record, failing to note the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, also was probably an error but, apparently, the court felt that this did not result in any harm to the patient.

The question arises of how there would be a defense verdict in light of the failure to track consecutive serum hCG levels. A speculative explanation is that there are many uncertainties in most lawsuits. Procedural problems may result in a case being limited, expert witnesses are essential to both the plaintiff and defense, with the quality of their review and testimony possibly uneven. Judges and juries may rely on one expert witness rather than another, juries vary, and the quality of advocacy differs. Any of these situations can contribute to the unpredictability of the outcome of a case. In the case above, the liability was somewhat uncertain, and the various other factors tipped in favor of a defense verdict. ●

CASE Unidentified ectopic pregnancy leads to rupture*

A 33-year-old woman (G1 P0010) with 2 positive home pregnancy tests presents to the emergency department (ED) reporting intermittent vaginal bleeding for 3 days. Her last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago, but she reports that her menses are always irregular. She has a history of asymptomatic chlamydia, as well as spontaneous abortion 2 years prior. At present, she denies abdominal pain or vaginal discharge.

Upon examination her vital signs are: temperature, 98.3 °F; pulse, 112 bpm, with a resting rate of 16 bpm; blood pressure (BP), 142/91 mm Hg; pulse O2, 99%; height, 4’ 3”; weight, 115 lb. Her labs are: hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 38%; serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 236 mIU/mL. Upon pelvic examination, no active bleeding is noted. She agrees to be followed up by her gynecologist and is given a prescription for serum hCG in 2 days. She is instructed to return to the ED should she have pain or increased vaginal bleeding.

Three days later, the patient follows up with her gynecologist reporting mild cramping. She notes having had an episode of heavy vaginal bleeding and a “weakly positive” home pregnancy test. Transvaginal ultrasonography notes endometrial thickness 0.59 mm and unremarkable adnexa. A urine pregnancy test performed in the office is positive; urinalysis is positive for nitrites. With the bleeding slowed, the gynecologist’s overall impression is that the patient has undergone complete spontaneous abortion. She prescribes Macrobid for the urinary tract infection. She does not obtain the ED-prescribed serum HCG levels, as she feels, since complete spontaneous abortion has occurred there is no need to obtain a follow-up serum HCG.

Five days later, the patient returns to the ED reporting abdominal pain after eating. Fever and productive cough of 2 days are noted. The patient states that she had a recent miscarriage. The overall impression of the patient’s condition is bronchitis, and it is noted on the patient’s record, “unlikely ectopic pregnancy and pregnancy test may be false positive,” hence a pregnancy test is not ordered. Examination reveals mild suprapubic tenderness with no rebound; no pelvic exam is performed. The patient is instructed to follow up with a health care clinic within a week, and to return to the ED with severe abdominal pain, higher fever, or any new concerning symptoms. A Zithromax Z-pak is prescribed.

Four days later, the patient is brought by ambulance to the ED of the local major medical center with severe abdominal pain involving the right lower quadrant. She states that she had a miscarriage 3 weeks prior and was recently treated for bronchitis. She has dizziness when standing. Her vital signs are: temperature, 97.8 °F; heart rate, 95 bpm; BP, 72/48 mm Hg; pulse O2, 100%. She reports her abdominal pain to be 6/10.

The patient is given a Lactated Ringer’s bolus of 1,000 mL for a hypotensive episode. Computed tomography is obtained and notes, “low attenuation in the left adnexa with a dilated fallopian tube.” A large heterogeneous collection of fluid in the pelvis is noted with active extravasation, consistent with an “acute bleed.”

The patient is brought to the operating room with a diagnosis of probable ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Intraoperatively she is noted to have a right ruptured ectopic and left tubo-ovarian abscess. The surgeon proceeds with right salpingectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy. Three liters of hemoperitoneum is found.

She is followed postoperatively with serum hCG until levels are negative. Her postoperative course is uneventful. Her only future option for pregnancy is through assisted reproductive technology (ART) with in vitro fertilization (IVF). The patient sues the gynecologist and second ED physician for presumed inappropriate assessment for ectopic pregnancy.

*The “facts” of this case are a composite, drawn from several cases to illustrate medical and legal issues. The statement of facts should be considered hypothetical.

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?...

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

A defense verdict is returned.

Medical considerations

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 2% of all pregnancies, with a higher incidence (about 4%) among infertility patients.1 Up to 10% of ectopic pregnancies have no symptoms.2

Clinical presentations. Classic signs of ectopic pregnancy include:

- abdominal pain

- vaginal bleeding

- late menses (often noted).

A recent case of ectopic pregnancy presenting with chest pain was reported.3 Clinicians must never lose site of the fact that ectopic pregnancy is the most common cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester, with an incidence of 1% to 10% of all first-trimester deaths.4

Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, as demonstrated in the opening case. “The silent epidemic of chlamydia” comes to mind, and tobacco smoking can adversely affect tubal cilia, as can pelvic adhesions and/or prior tubal surgery. All of these factors can predispose a patient to ectopic pregnancy; in addition, intrauterine devices, endometriosis, tubal ligation (or ligation reversal), all can set the stage for an ectopic pregnancy.5 Appropriate serum hCG monitoring during early pregnancy can assist in sorting out pregnancies of unknown location (PUL; FIGURE). First trimester ultrasonography, at 5 weeks gestation, usually identifies early intrauterine gestation.

Imaging. With regard to pelvic sonography, the earliest sign of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is a sac eccentrically located in the decidua.6 As the IUP progresses, it becomes equated with a “double decidual sign,” with double rings of tissue around the sac.6 If the pregnancy is located in an adnexal mass, it is frequently inhomogeneous or noncystic in appearance (ie, “the blob” sign); the positive predictive value (PPV) is 96%.2 The PPV of transvaginal ultrasound is 80%, as paratubal, paraovarian, ovarian cyst, and hydrosalpinx can affect the interpretation.7

Heterotopic pregnancy includes an intrauterine gestation and an ectopic pregnancy. This presentation includes the presence of a “pseudosac” in the endometrial cavity plus an extrauterine gestation. Heterotopic pregnancies have become somewhat more common as ART/IVF has unfolded, especially prior to the predominance of single embryo transfer.

Managing ectopic pregnancy

For cases of early pregnancy complicated by intermittent bleeding and/or pain, monitoring with serum hCG levels at 48-hour intervals to distinguish a viable IUP from an abnormal IUP or an ectopic is appropriate. The “discriminatory zone” collates serum hCG levels with findings on ultrasonography. Specific lower limits of serum hCG levels are not clear cut, with recommendations of 3,500 mIU/mL to provide sonographic evidence of an intrauterine gestation “to avoid misdiagnosis and possible interruption of intrauterine pregnancy,” as conveyed in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018 practice bulletin.8 Serum progesterone levels also have been suggested to complement hCG levels; a progesterone level of <20 nmol/L is consistent with an abnormal pregnancy, whereas levels >25 nmol/L are suggestive of a viable pregnancy.2 Inhibin A levels also have been suggested to be helpful, but they are not an ideal monitoring tool.

While most ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube, other locations also can be abdominal or ovarian. In addition, cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can occur and often is associated with delay in diagnosis and greater morbidity due to such delay.9 With regard to ovarian ectopic, Spiegelberg criteria are established for diagnosis (TABLE 1).10

Appropriate management of an ectopic pregnancy is dependent upon the gestational age, serum hCG levels, and imaging findings, as well as the patient’s symptoms and exam findings. Treatment is established in large part on a case-by-case basis and includes, for early pregnancy, expectant management and use of methotrexate (TABLE 2).11 Dilation and curettage may be used to identify the pregnancy’s location when the serum hCG level is below 2,000 mIU/mL and there is no evidence of an IUP on ultrasound. Surgical treatment can include minimally invasive salpingostomy or salpingectomy and, depending on circumstance, laparotomy may be indicated.

Fertility following ectopic pregnancy varies and is affected by location, treatment, predisposing factors, total number of ectopic pregnancies, and other factors. Ectopic pregnancy, although rare, also can occur with use of IVF. Humans are not unique with regard to ectopic pregnancies, as they also occur in sheep.12

Continue to: Legal perspective...

Legal perspective

Lawsuits related to ectopic pregnancy are not a new phenomenon. In fact, in 1897, a physician in Ohio who misdiagnosed an “extrauterine pregnancy” as appendicitis was the center of a malpractice lawsuit.13 Unrecognized or mishandled ectopic pregnancy can result in serious injuries—in the range of 1% to 10% (see above) of maternal deaths are related to ectopic pregnancy.14 Ectopic pregnancy cases, therefore, have been the subject of substantial litigation over the years. An informal, noncomprehensive review of malpractice lawsuits brought from 2000 to 2019, found more than 300 ectopic pregnancy cases. Given the large number of malpractice claims against ObGyns,15 ectopic pregnancy cases are only a small portion of all ObGyn malpractice cases.16

A common claim: negligent diagnosis or treatment

The most common basis for lawsuits in cases of ectopic pregnancy is the clinician’s negligent failure to properly diagnose the ectopic nature of the pregnancy. There are also a number of cases claiming negligent treatment of an identified ectopic pregnancy. Not every missed diagnosis, or unsuccessful treatment, leads to liability, of course. It is only when a diagnosis or treatment fails to meet the standard of care within the profession that there should be liability. That standard of care is generally defined by what a reasonably prudent physician would do under the circumstances. Expert witnesses, who are familiar with the standard of practice within the specialty, are usually necessary to establish what that practice is. Both the plaintiff and the defense obtain experts, the former to prove what the standard of care is and that the standard was not met in the case at hand. The defense experts are usually arguing that the standard of care was met.17 Inadequate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy or other condition may arise from a failure to take a sufficient history, conduct an appropriately thorough physical examination, recognize any of the symptoms that would suggest it is present, use and conduct ultrasound correctly, or follow-up appropriately with additional testing.18

A malpractice claim of negligent treatment can involve any the following circumstances19:

- failure to establish an appropriate treatment plan

- prescribing inappropriate medications for the patient (eg, methotrexate, when it is contraindicated)

- delivering the wrong medication or the wrong amount of the right medication

- performing a procedure badly

- undertaking a new treatment without adequate instruction and preparation.

Given the nature and risks of ectopic pregnancy, ongoing, frequent contact with the patient is essential from the point at which the condition is suspected. The greater the risk of harm (probability or consequence), the more careful any professional ought to be. Because ectopic pregnancy is not an uncommon occurrence, and because it can have devastating effects, including death, a reasonably prudent practitioner would be especially aware of the clinical presentations discussed above.20 In the opening case, the treatment plan was not well documented.

Negligence must lead to patient harm. In addition to negligence (proving that the physician did not act in accordance with the standard of care), to prevail in a malpractice case, the plaintiff-patient must prove that the negligence caused the injury, or worsened it. If the failure to make a diagnosis would not have made any difference in a harm the patient suffered, there are no damages and no liability. Suppose, for example, that a physician negligently failed to diagnose ectopic pregnancy, but performed surgery expecting to find the misdiagnosed condition. In the course of the surgery, however, the surgeon discovered and appropriately treated the ectopic pregnancy. (A version of this happened in the old 19th century case mentioned above.) The negligence of the physician did not cause harm, so there are no damages and no liability.

Continue to: Informed consent is vital...

Informed consent is vital

A part of malpractice is informed consent (or the absence of it)—issues that can arise in any medical care.21 It is wise to pay particular attention in cases where the nature of the illness is unknown, and where there are significant uncertainties and the nature of testing and treatment may change substantially over a period of a few days or few weeks. As always, informed consent should include a discussion of what process or procedure is proposed, its risks and benefits, alternative approaches that might be available, and the risk of doing nothing. Frequently, the uncertainty of ectopic pregnancy complicates the informed consent process.22

Because communication with the patient is an essential function of informed consent, the consent process should productively be used in PUL and similar cases to inform the patient about the uncertainty, and the testing and (nonsurgical) treatment that will occur. This is an opportunity to reinforce the message that the patient must maintain ongoing communication with the physician’s office about changes in her condition, and appear for each appointment scheduled. If more invasive procedures—notably surgery—become required, a separate consent process should be completed, because the risks and considerations are now meaningfully different than when treatment began. As a general matter, any possible treatment that may result in infertility or reduced reproductive capacity should specifically be included in the consent process.