User login

Alternative regimen reduces narcotic use after pelvic reconstructive surgery

TUCSON, ARIZ. – compared with a standard regimen, with no difference in patient satisfaction scores.

The new study extends findings from other surgical procedures to pelvic reconstructive surgery.

“This can limit both inpatient and outpatient narcotic use. It uses oral Toradol on an outpatient basis. It’s totally underutilized. People are afraid of it, people think it causes more bleeding, and maybe there’s a cost issue,” Andrey Petrikovets, MD, a urogynecologist in Los Angeles, said in an interview.

The regimen, which he calls ICE-T, relies in part on 16 tablets of Toradol sent home with the patient – 4 days’ worth. “It’s just 16 tablets, so it’s cheap, and patients do great with it. If you really use Toradol appropriately, especially on an outpatient basis, you can pretty much eliminate outpatient narcotic use,” said Dr. Petrikovets, who presented the work at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

He believes that ICE-T is a good option for vaginal surgery. It’s a possibility for benign laparoscopic and perhaps robotic surgery, although those applications need to be studied. ICE-T should be avoided in patients with chronic pain, as well as patients with contraindications to any of the regimen’s medications, Dr. Petrikovets said.

According to the protocol, until hospital discharge, patients receive 20 minutes of ice to the perineum every 2 hours, 30 mg IV Toradol every 6 hours, 1,000 mg oral Tylenol every 6 hours, and 0.2 mg IV Dilaudid every 3 hours as needed for breakthrough pain. The constant pain management is important, said Dr. Petrikovets. “Patients don’t have an opportunity for the pain to get really high,” he said. At-home management includes 1,000 mg oral Tylenol every 6 hours, as needed (pain level 1-5, 60 tablets), and 10 mg Toradol every 6 hours as needed (pain level 6-10, 16 tablets).

The trial was conducted at two centers, where 63 patients were randomized to ICE-T or a standard regimen, which at the hospital included 600 mg ibuprofen every 6 hours as needed for pain levels 1-3, one tablet of Percocet (5/325 mg) every 4-6 hours as needed for pain levels 4-6, two tablets of Percocet for pain levels 7-10, and 0.2 mg IV Dilaudid every 3 hours as needed for breakthrough pain. At-home management consisted of 600 mg ibuprofen every 6 hours for pain levels 1-5 (60 tablets), and Percocet 5/325 mg every 6 hours for pain levels 6-10 (16 tablets).

Using the visual analog scale, researchers found that the 30 patients in the ICE-T arm of the study had less morning pain (VAS score, 20 mm vs. 40 mm; P = .03), and lower numerical pain score at 96 hours (2 vs. 3; P = .04). During the mornings and at 96 hours, the two groups had similar quality of recovery and satisfaction scores.

Narcotic use, measured as oral morphine equivalents, was significantly lower in the ICE-T arm between exit from the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and hospital discharge (3 vs. 20; P less than .001) and through PACU all the way to discharge (17 vs. 38; P less than .001); 70% of patients in the ICE-T arm required no narcotics after PACU discharge, compared with 12% in the standard care arm (P less than .001).

At 96 hours, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the number of emergency department visits, percentage who had a bowel movement since surgery, or the number of Percocet/Toradol tablets taken. The ICE-T group took more Tylenol tablets than did the standard group took ibuprofen (11 vs. 6; P = .012).

SOURCE: Petrikovets A et al. SGS 2019, Abstract 07.

TUCSON, ARIZ. – compared with a standard regimen, with no difference in patient satisfaction scores.

The new study extends findings from other surgical procedures to pelvic reconstructive surgery.

“This can limit both inpatient and outpatient narcotic use. It uses oral Toradol on an outpatient basis. It’s totally underutilized. People are afraid of it, people think it causes more bleeding, and maybe there’s a cost issue,” Andrey Petrikovets, MD, a urogynecologist in Los Angeles, said in an interview.

The regimen, which he calls ICE-T, relies in part on 16 tablets of Toradol sent home with the patient – 4 days’ worth. “It’s just 16 tablets, so it’s cheap, and patients do great with it. If you really use Toradol appropriately, especially on an outpatient basis, you can pretty much eliminate outpatient narcotic use,” said Dr. Petrikovets, who presented the work at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

He believes that ICE-T is a good option for vaginal surgery. It’s a possibility for benign laparoscopic and perhaps robotic surgery, although those applications need to be studied. ICE-T should be avoided in patients with chronic pain, as well as patients with contraindications to any of the regimen’s medications, Dr. Petrikovets said.

According to the protocol, until hospital discharge, patients receive 20 minutes of ice to the perineum every 2 hours, 30 mg IV Toradol every 6 hours, 1,000 mg oral Tylenol every 6 hours, and 0.2 mg IV Dilaudid every 3 hours as needed for breakthrough pain. The constant pain management is important, said Dr. Petrikovets. “Patients don’t have an opportunity for the pain to get really high,” he said. At-home management includes 1,000 mg oral Tylenol every 6 hours, as needed (pain level 1-5, 60 tablets), and 10 mg Toradol every 6 hours as needed (pain level 6-10, 16 tablets).

The trial was conducted at two centers, where 63 patients were randomized to ICE-T or a standard regimen, which at the hospital included 600 mg ibuprofen every 6 hours as needed for pain levels 1-3, one tablet of Percocet (5/325 mg) every 4-6 hours as needed for pain levels 4-6, two tablets of Percocet for pain levels 7-10, and 0.2 mg IV Dilaudid every 3 hours as needed for breakthrough pain. At-home management consisted of 600 mg ibuprofen every 6 hours for pain levels 1-5 (60 tablets), and Percocet 5/325 mg every 6 hours for pain levels 6-10 (16 tablets).

Using the visual analog scale, researchers found that the 30 patients in the ICE-T arm of the study had less morning pain (VAS score, 20 mm vs. 40 mm; P = .03), and lower numerical pain score at 96 hours (2 vs. 3; P = .04). During the mornings and at 96 hours, the two groups had similar quality of recovery and satisfaction scores.

Narcotic use, measured as oral morphine equivalents, was significantly lower in the ICE-T arm between exit from the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and hospital discharge (3 vs. 20; P less than .001) and through PACU all the way to discharge (17 vs. 38; P less than .001); 70% of patients in the ICE-T arm required no narcotics after PACU discharge, compared with 12% in the standard care arm (P less than .001).

At 96 hours, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the number of emergency department visits, percentage who had a bowel movement since surgery, or the number of Percocet/Toradol tablets taken. The ICE-T group took more Tylenol tablets than did the standard group took ibuprofen (11 vs. 6; P = .012).

SOURCE: Petrikovets A et al. SGS 2019, Abstract 07.

TUCSON, ARIZ. – compared with a standard regimen, with no difference in patient satisfaction scores.

The new study extends findings from other surgical procedures to pelvic reconstructive surgery.

“This can limit both inpatient and outpatient narcotic use. It uses oral Toradol on an outpatient basis. It’s totally underutilized. People are afraid of it, people think it causes more bleeding, and maybe there’s a cost issue,” Andrey Petrikovets, MD, a urogynecologist in Los Angeles, said in an interview.

The regimen, which he calls ICE-T, relies in part on 16 tablets of Toradol sent home with the patient – 4 days’ worth. “It’s just 16 tablets, so it’s cheap, and patients do great with it. If you really use Toradol appropriately, especially on an outpatient basis, you can pretty much eliminate outpatient narcotic use,” said Dr. Petrikovets, who presented the work at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

He believes that ICE-T is a good option for vaginal surgery. It’s a possibility for benign laparoscopic and perhaps robotic surgery, although those applications need to be studied. ICE-T should be avoided in patients with chronic pain, as well as patients with contraindications to any of the regimen’s medications, Dr. Petrikovets said.

According to the protocol, until hospital discharge, patients receive 20 minutes of ice to the perineum every 2 hours, 30 mg IV Toradol every 6 hours, 1,000 mg oral Tylenol every 6 hours, and 0.2 mg IV Dilaudid every 3 hours as needed for breakthrough pain. The constant pain management is important, said Dr. Petrikovets. “Patients don’t have an opportunity for the pain to get really high,” he said. At-home management includes 1,000 mg oral Tylenol every 6 hours, as needed (pain level 1-5, 60 tablets), and 10 mg Toradol every 6 hours as needed (pain level 6-10, 16 tablets).

The trial was conducted at two centers, where 63 patients were randomized to ICE-T or a standard regimen, which at the hospital included 600 mg ibuprofen every 6 hours as needed for pain levels 1-3, one tablet of Percocet (5/325 mg) every 4-6 hours as needed for pain levels 4-6, two tablets of Percocet for pain levels 7-10, and 0.2 mg IV Dilaudid every 3 hours as needed for breakthrough pain. At-home management consisted of 600 mg ibuprofen every 6 hours for pain levels 1-5 (60 tablets), and Percocet 5/325 mg every 6 hours for pain levels 6-10 (16 tablets).

Using the visual analog scale, researchers found that the 30 patients in the ICE-T arm of the study had less morning pain (VAS score, 20 mm vs. 40 mm; P = .03), and lower numerical pain score at 96 hours (2 vs. 3; P = .04). During the mornings and at 96 hours, the two groups had similar quality of recovery and satisfaction scores.

Narcotic use, measured as oral morphine equivalents, was significantly lower in the ICE-T arm between exit from the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and hospital discharge (3 vs. 20; P less than .001) and through PACU all the way to discharge (17 vs. 38; P less than .001); 70% of patients in the ICE-T arm required no narcotics after PACU discharge, compared with 12% in the standard care arm (P less than .001).

At 96 hours, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the number of emergency department visits, percentage who had a bowel movement since surgery, or the number of Percocet/Toradol tablets taken. The ICE-T group took more Tylenol tablets than did the standard group took ibuprofen (11 vs. 6; P = .012).

SOURCE: Petrikovets A et al. SGS 2019, Abstract 07.

REPORTING FROM SGS 2019

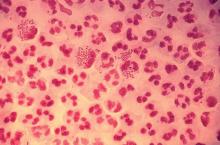

STIs pose complex challenge to HIV efforts

SEATTLE – Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are on the rise among HIV-infected individuals, and emerging antimicrobial resistance in these organisms is presenting serious challenges to physicians. The issue may be traceable to the introduction of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2011, which previous studies have shown to be associated with less condom use.

In the United States, a 2017 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed rising incidences of chlamydia (+5% from 2015 to 2017), gonorrhea (+19%), and syphilis (+18%). “We have an incidence among men who have sex with men [MSM] that is above the pre-AIDS era estimates, and we have evidence of spread into heterosexual networks, and a very scary collision with the methamphetamine and heroine using networks,” said Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But the numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. “It’s not just the burden of these infections. What’s characterizing these trends is that we have continuing evolution of microbial resistance, which is really a crisis,” Dr. Marrazzo added during a plenary she delivered at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

These infections also remain intricately linked with HIV. An analysis of syphilis cases found that 88% occurred in men. Of those, 80% were MSM. Of the cases in MSM, 46% were coinfected with HIV. “Those are incredible rates,” said Dr. Marrazzo. Among women, the trends are even more alarming. There has been a greater than 150% increase in primary/secondary and congenital syphilis between 2013 and 2017.

Resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin remains on the rise in gonorrhea, with 24% of countries reporting at least a 5% incidence of strains that are less susceptible or resistant to ceftriaxone, and 81% of countries reporting similar trends with azithromycin.

In the absence of new drugs to overcome that resistance, or vaccines that can prevent gonorrhea and other infections, what are clinicians to do?

One option may be postexposure doxycycline. One trial in MSM showed that a 200-mg dose taken 24-72 hours after sex was associated with about a 70% increase in both time to first chlamydia and time to first syphilis infection, though no effect was seen on gonorrhea infections. “We shouldn’t be surprised. We know that gonorrhea is classically resistant to tetracyclines, and the MSM population has the highest prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in gonorrhea,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

There are pros and cons to this strategy, of course. On the one hand, doxycycline works for chlamydia and syphilis, it’s safe, and it’s easy to administer. “We’re up a tree when it comes to syphilis, so why not?” opined Dr. Marrazzo. In fact, some MSM have read the literature and are already using it prophylactically. But there are downsides, including adverse effects such as esophagitis/ulceration and photosensitivity, and it is contraindicated in pregnant women. And then there’s the potential for evolving greater resistance. “The horse is out of the barn with respect to gonorrhea, but I think it’s worth thinking about resistance to other pathogens, where we still rely on doxycycline [to treat] in rare cases,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Finally, Dr. Marrazzo discussed the role of STI treatment in the effort to eradicate HIV. Should the Getting to 0 strategies include aggressive prevention and treatment of STIs? Despite the potentiating role of some STIs in the spread HIV, some urban areas are approaching zero new infections even as other STIs remain a problem. It could be that undetectable = untransmittable, regardless of the presence an STI. Some view targeting STIs as a regressive practice in a setting where the U=U mantra has opened up an era of sexual freedom living with or at risk of HIV.

On the other hand, there are also good arguments to target STIs while trying to eliminate HIV. Results from high-resource locales such as San Francisco and New York City are unlikely to be replicated in places like Sub-Saharan Africa. The public health burden of STIs is extensive, and antibiotic resistance and antibiotic shortages can make treatment difficult. The situation is also different for women, who may experience impacts on fertility or pregnancies, and do not have the same freedom as men in many countries. “Stigma is highly operative and I would wager that sexual pleasure and freedom remain a very elusive goal for women across the globe,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Dr. Marrazzo has a research grant/grant pending from Cepheid, and is on the advisory panels of BioFire and Gilead.

SEATTLE – Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are on the rise among HIV-infected individuals, and emerging antimicrobial resistance in these organisms is presenting serious challenges to physicians. The issue may be traceable to the introduction of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2011, which previous studies have shown to be associated with less condom use.

In the United States, a 2017 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed rising incidences of chlamydia (+5% from 2015 to 2017), gonorrhea (+19%), and syphilis (+18%). “We have an incidence among men who have sex with men [MSM] that is above the pre-AIDS era estimates, and we have evidence of spread into heterosexual networks, and a very scary collision with the methamphetamine and heroine using networks,” said Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But the numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. “It’s not just the burden of these infections. What’s characterizing these trends is that we have continuing evolution of microbial resistance, which is really a crisis,” Dr. Marrazzo added during a plenary she delivered at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

These infections also remain intricately linked with HIV. An analysis of syphilis cases found that 88% occurred in men. Of those, 80% were MSM. Of the cases in MSM, 46% were coinfected with HIV. “Those are incredible rates,” said Dr. Marrazzo. Among women, the trends are even more alarming. There has been a greater than 150% increase in primary/secondary and congenital syphilis between 2013 and 2017.

Resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin remains on the rise in gonorrhea, with 24% of countries reporting at least a 5% incidence of strains that are less susceptible or resistant to ceftriaxone, and 81% of countries reporting similar trends with azithromycin.

In the absence of new drugs to overcome that resistance, or vaccines that can prevent gonorrhea and other infections, what are clinicians to do?

One option may be postexposure doxycycline. One trial in MSM showed that a 200-mg dose taken 24-72 hours after sex was associated with about a 70% increase in both time to first chlamydia and time to first syphilis infection, though no effect was seen on gonorrhea infections. “We shouldn’t be surprised. We know that gonorrhea is classically resistant to tetracyclines, and the MSM population has the highest prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in gonorrhea,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

There are pros and cons to this strategy, of course. On the one hand, doxycycline works for chlamydia and syphilis, it’s safe, and it’s easy to administer. “We’re up a tree when it comes to syphilis, so why not?” opined Dr. Marrazzo. In fact, some MSM have read the literature and are already using it prophylactically. But there are downsides, including adverse effects such as esophagitis/ulceration and photosensitivity, and it is contraindicated in pregnant women. And then there’s the potential for evolving greater resistance. “The horse is out of the barn with respect to gonorrhea, but I think it’s worth thinking about resistance to other pathogens, where we still rely on doxycycline [to treat] in rare cases,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Finally, Dr. Marrazzo discussed the role of STI treatment in the effort to eradicate HIV. Should the Getting to 0 strategies include aggressive prevention and treatment of STIs? Despite the potentiating role of some STIs in the spread HIV, some urban areas are approaching zero new infections even as other STIs remain a problem. It could be that undetectable = untransmittable, regardless of the presence an STI. Some view targeting STIs as a regressive practice in a setting where the U=U mantra has opened up an era of sexual freedom living with or at risk of HIV.

On the other hand, there are also good arguments to target STIs while trying to eliminate HIV. Results from high-resource locales such as San Francisco and New York City are unlikely to be replicated in places like Sub-Saharan Africa. The public health burden of STIs is extensive, and antibiotic resistance and antibiotic shortages can make treatment difficult. The situation is also different for women, who may experience impacts on fertility or pregnancies, and do not have the same freedom as men in many countries. “Stigma is highly operative and I would wager that sexual pleasure and freedom remain a very elusive goal for women across the globe,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Dr. Marrazzo has a research grant/grant pending from Cepheid, and is on the advisory panels of BioFire and Gilead.

SEATTLE – Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are on the rise among HIV-infected individuals, and emerging antimicrobial resistance in these organisms is presenting serious challenges to physicians. The issue may be traceable to the introduction of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2011, which previous studies have shown to be associated with less condom use.

In the United States, a 2017 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed rising incidences of chlamydia (+5% from 2015 to 2017), gonorrhea (+19%), and syphilis (+18%). “We have an incidence among men who have sex with men [MSM] that is above the pre-AIDS era estimates, and we have evidence of spread into heterosexual networks, and a very scary collision with the methamphetamine and heroine using networks,” said Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But the numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. “It’s not just the burden of these infections. What’s characterizing these trends is that we have continuing evolution of microbial resistance, which is really a crisis,” Dr. Marrazzo added during a plenary she delivered at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

These infections also remain intricately linked with HIV. An analysis of syphilis cases found that 88% occurred in men. Of those, 80% were MSM. Of the cases in MSM, 46% were coinfected with HIV. “Those are incredible rates,” said Dr. Marrazzo. Among women, the trends are even more alarming. There has been a greater than 150% increase in primary/secondary and congenital syphilis between 2013 and 2017.

Resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin remains on the rise in gonorrhea, with 24% of countries reporting at least a 5% incidence of strains that are less susceptible or resistant to ceftriaxone, and 81% of countries reporting similar trends with azithromycin.

In the absence of new drugs to overcome that resistance, or vaccines that can prevent gonorrhea and other infections, what are clinicians to do?

One option may be postexposure doxycycline. One trial in MSM showed that a 200-mg dose taken 24-72 hours after sex was associated with about a 70% increase in both time to first chlamydia and time to first syphilis infection, though no effect was seen on gonorrhea infections. “We shouldn’t be surprised. We know that gonorrhea is classically resistant to tetracyclines, and the MSM population has the highest prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in gonorrhea,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

There are pros and cons to this strategy, of course. On the one hand, doxycycline works for chlamydia and syphilis, it’s safe, and it’s easy to administer. “We’re up a tree when it comes to syphilis, so why not?” opined Dr. Marrazzo. In fact, some MSM have read the literature and are already using it prophylactically. But there are downsides, including adverse effects such as esophagitis/ulceration and photosensitivity, and it is contraindicated in pregnant women. And then there’s the potential for evolving greater resistance. “The horse is out of the barn with respect to gonorrhea, but I think it’s worth thinking about resistance to other pathogens, where we still rely on doxycycline [to treat] in rare cases,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Finally, Dr. Marrazzo discussed the role of STI treatment in the effort to eradicate HIV. Should the Getting to 0 strategies include aggressive prevention and treatment of STIs? Despite the potentiating role of some STIs in the spread HIV, some urban areas are approaching zero new infections even as other STIs remain a problem. It could be that undetectable = untransmittable, regardless of the presence an STI. Some view targeting STIs as a regressive practice in a setting where the U=U mantra has opened up an era of sexual freedom living with or at risk of HIV.

On the other hand, there are also good arguments to target STIs while trying to eliminate HIV. Results from high-resource locales such as San Francisco and New York City are unlikely to be replicated in places like Sub-Saharan Africa. The public health burden of STIs is extensive, and antibiotic resistance and antibiotic shortages can make treatment difficult. The situation is also different for women, who may experience impacts on fertility or pregnancies, and do not have the same freedom as men in many countries. “Stigma is highly operative and I would wager that sexual pleasure and freedom remain a very elusive goal for women across the globe,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Dr. Marrazzo has a research grant/grant pending from Cepheid, and is on the advisory panels of BioFire and Gilead.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CROI 2019

Anterior, apical, posterior: Vaginal anatomy for the gynecologic surgeon

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

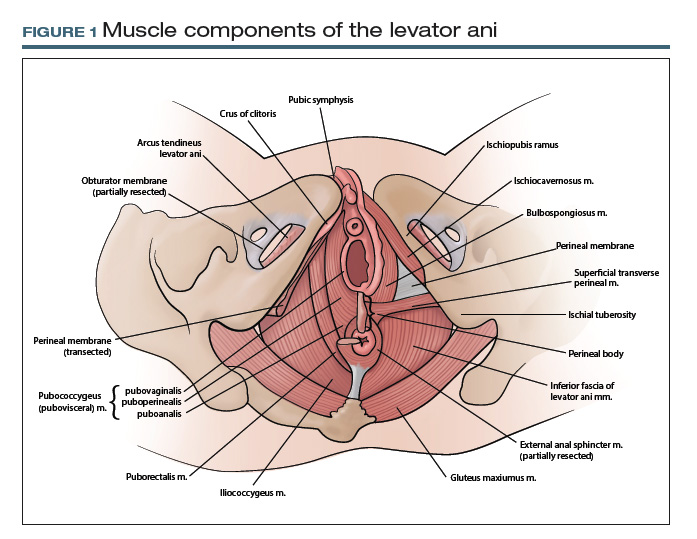

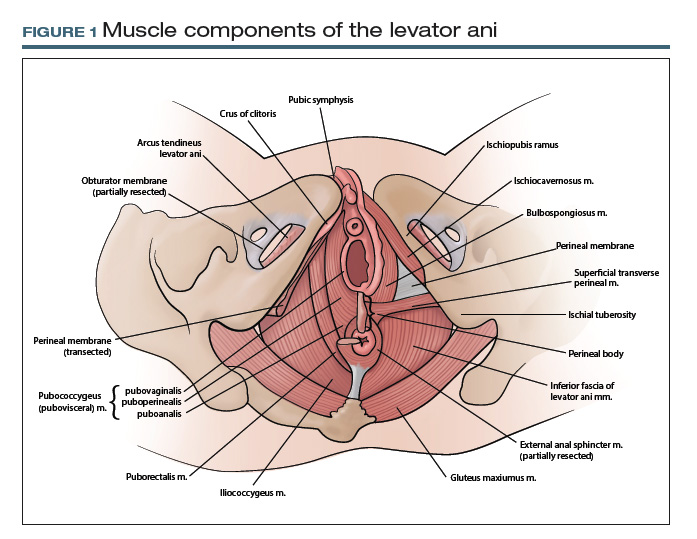

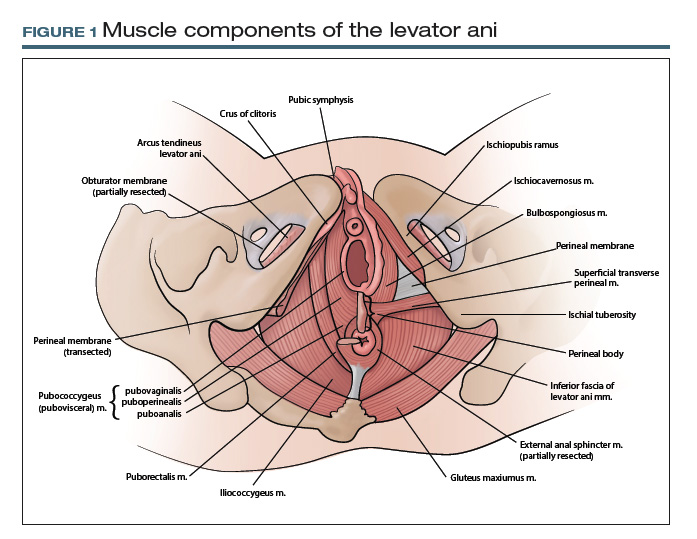

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.

In 1990, an international committee was formed with representatives from many anatomical organizations, again with the intention of providing standardized anatomic terminology. Those efforts resulted in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology, commonly referred to as TA, in 1998. TA continues to be the referent standard for human anatomic terminology; it was most recently updated in 2011.4

CASE 2 Conveying details of mesh erosion

A 52-year-old woman presents to the general gynecology clinic with a 10-year history of pelvic pain and dyspareunia after undergoing vaginal mesh surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence. On examination, there is a visible ridge of mesh extending from the left side of the midurethra along the anterior and lateral vagina for a length of 1.5 cm. There also is a palpable tight band on the right vaginal wall near the ischial spine that reproduces her pain and causes spasm of the levator ani. You believe the patient needs a urogynecology referral for complications of vaginal mesh. How do you best describe your findings to your urogynecology colleague?

Continue to: Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective...

Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) recognized the importance of standardizing terminology specific to the pelvis. The SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group thus was organized in 2016. The Pelvic Anatomy Group’s purpose is to help educate physicians about pelvic anatomy, with the overarching goal of compiling instructional materials, primarily from dissections (surgical or cadaveric), and radiologic imaging for all pelvic structures. Throughout the discussions on this initiative, it became clear that standardized terms needed to be established and used for pelvic structures.

While TA is an excellent reference work, it does not include all of the clinically relevant structures for gynecologic surgeons. As physicians, surgeons, and women’s health care providers, we read about and discuss pelvic anatomy structures in medical textbooks, medical literature, and clinical settings that are not necessarily included in TA. In addition, advances in information technology have facilitated the creation of clinically oriented computer-based anatomy programs and expanded the number and availability of electronic publications on surgical and clinical anatomy.5 As a result, there is a need not only to standardize nomenclature but also to continually revise and update terminology and integrate new terms, both from an anatomic and a clinical perspective.

The Pelvic Anatomy Group developed a novel approach to anatomic terminology. We decided to review the medical literature, identify the terms used, adjudicate the terms with current TA terms, and provide consensus for the terms and structures in the pelvis. Because of the volume of literature available and the existing number of terms, we divided the pelvis into 4 regions—anterior, apical, posterior, and vulvar—to improve the feasibility of reviewing the medical literature for the entire female pelvis.

Our process for tackling terminology

Our literature review started with the anterior compartment. (For complete details, see our prior publication.3) Modeled on a systematic review, we searched the MEDLINE database for terms related to the anterior pelvis, screened all associated abstracts, and then extracted terms from appropriate papers. We also identified several book chapters from various disciplines (anatomy, gynecology, urology, and radiology) to ensure wide representation of disciplines. We then extracted all terms pertinent to the anterior pelvis.

We organized the terms, with terms that referred to the same anatomic structure grouped together. Whenever possible, we used TA terms as the preferred terms. In this process, however, we identified several clinically relevant terms that were not included in TA: pelvic sidewall, pelvic bones, anterior compartment, pubourethral ligament, vaginal sulcus, and levator hiatus, among others. The new terms were then proposed and agreed on by members of the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group and accepted by SGS members. We currently are completing a similar process for the apical pelvis, posterior pelvis, and vulvar regions.

TA code numbers pinpoint the nomenclature

As we move forward, we suggest that physicians use TA or other approved terms for patient and research communication. Such use will help standardize anatomic terms and also will improve communication between providers and education for learners.

Continue to: TA includes approved options...

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

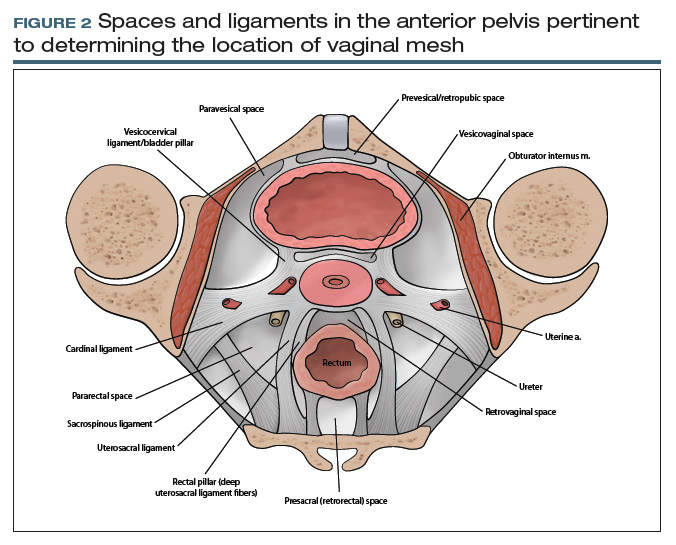

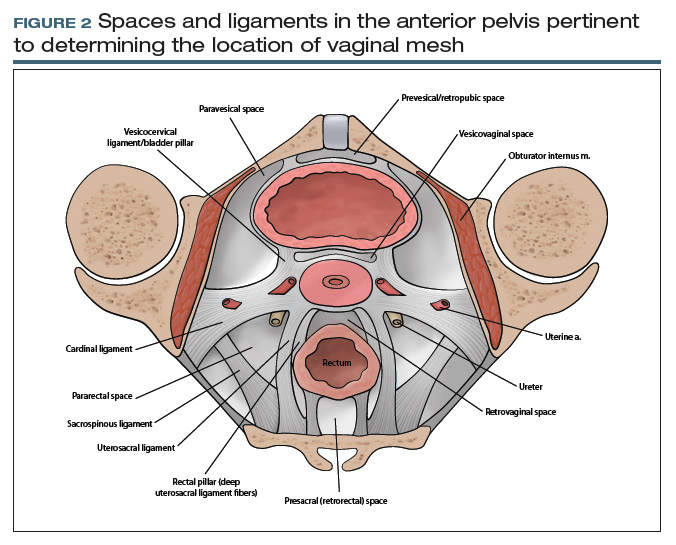

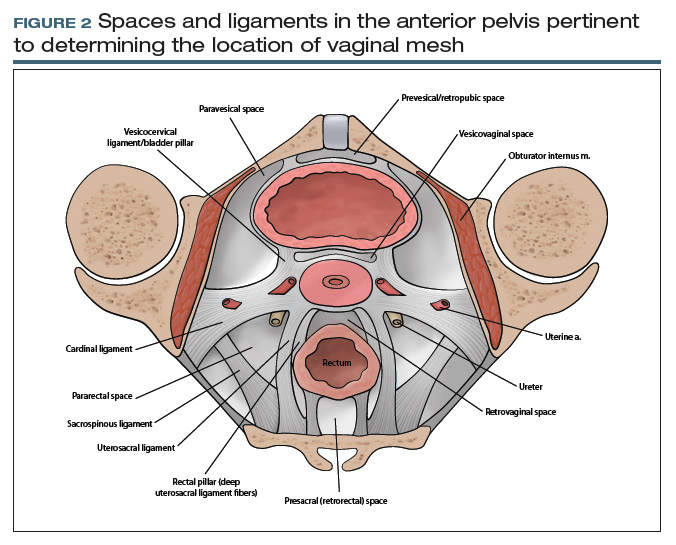

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43-54.

- Venes D, ed. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- Jeppson PC, Balgobin S, Washington BB, et al; for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Pelvic Anatomy Group. Recommended standardized terminology of the anterior female pelvis based on a structured medical literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:26-39.

- Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminologies (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2011.

- Rosse C. Terminologia Anatomica: considered from the perspective of next-generation knowledge sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14:120-133.

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.

In 1990, an international committee was formed with representatives from many anatomical organizations, again with the intention of providing standardized anatomic terminology. Those efforts resulted in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology, commonly referred to as TA, in 1998. TA continues to be the referent standard for human anatomic terminology; it was most recently updated in 2011.4

CASE 2 Conveying details of mesh erosion

A 52-year-old woman presents to the general gynecology clinic with a 10-year history of pelvic pain and dyspareunia after undergoing vaginal mesh surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence. On examination, there is a visible ridge of mesh extending from the left side of the midurethra along the anterior and lateral vagina for a length of 1.5 cm. There also is a palpable tight band on the right vaginal wall near the ischial spine that reproduces her pain and causes spasm of the levator ani. You believe the patient needs a urogynecology referral for complications of vaginal mesh. How do you best describe your findings to your urogynecology colleague?

Continue to: Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective...

Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) recognized the importance of standardizing terminology specific to the pelvis. The SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group thus was organized in 2016. The Pelvic Anatomy Group’s purpose is to help educate physicians about pelvic anatomy, with the overarching goal of compiling instructional materials, primarily from dissections (surgical or cadaveric), and radiologic imaging for all pelvic structures. Throughout the discussions on this initiative, it became clear that standardized terms needed to be established and used for pelvic structures.

While TA is an excellent reference work, it does not include all of the clinically relevant structures for gynecologic surgeons. As physicians, surgeons, and women’s health care providers, we read about and discuss pelvic anatomy structures in medical textbooks, medical literature, and clinical settings that are not necessarily included in TA. In addition, advances in information technology have facilitated the creation of clinically oriented computer-based anatomy programs and expanded the number and availability of electronic publications on surgical and clinical anatomy.5 As a result, there is a need not only to standardize nomenclature but also to continually revise and update terminology and integrate new terms, both from an anatomic and a clinical perspective.

The Pelvic Anatomy Group developed a novel approach to anatomic terminology. We decided to review the medical literature, identify the terms used, adjudicate the terms with current TA terms, and provide consensus for the terms and structures in the pelvis. Because of the volume of literature available and the existing number of terms, we divided the pelvis into 4 regions—anterior, apical, posterior, and vulvar—to improve the feasibility of reviewing the medical literature for the entire female pelvis.

Our process for tackling terminology

Our literature review started with the anterior compartment. (For complete details, see our prior publication.3) Modeled on a systematic review, we searched the MEDLINE database for terms related to the anterior pelvis, screened all associated abstracts, and then extracted terms from appropriate papers. We also identified several book chapters from various disciplines (anatomy, gynecology, urology, and radiology) to ensure wide representation of disciplines. We then extracted all terms pertinent to the anterior pelvis.

We organized the terms, with terms that referred to the same anatomic structure grouped together. Whenever possible, we used TA terms as the preferred terms. In this process, however, we identified several clinically relevant terms that were not included in TA: pelvic sidewall, pelvic bones, anterior compartment, pubourethral ligament, vaginal sulcus, and levator hiatus, among others. The new terms were then proposed and agreed on by members of the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group and accepted by SGS members. We currently are completing a similar process for the apical pelvis, posterior pelvis, and vulvar regions.

TA code numbers pinpoint the nomenclature

As we move forward, we suggest that physicians use TA or other approved terms for patient and research communication. Such use will help standardize anatomic terms and also will improve communication between providers and education for learners.

Continue to: TA includes approved options...

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.

In 1990, an international committee was formed with representatives from many anatomical organizations, again with the intention of providing standardized anatomic terminology. Those efforts resulted in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology, commonly referred to as TA, in 1998. TA continues to be the referent standard for human anatomic terminology; it was most recently updated in 2011.4

CASE 2 Conveying details of mesh erosion

A 52-year-old woman presents to the general gynecology clinic with a 10-year history of pelvic pain and dyspareunia after undergoing vaginal mesh surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence. On examination, there is a visible ridge of mesh extending from the left side of the midurethra along the anterior and lateral vagina for a length of 1.5 cm. There also is a palpable tight band on the right vaginal wall near the ischial spine that reproduces her pain and causes spasm of the levator ani. You believe the patient needs a urogynecology referral for complications of vaginal mesh. How do you best describe your findings to your urogynecology colleague?

Continue to: Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective...

Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) recognized the importance of standardizing terminology specific to the pelvis. The SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group thus was organized in 2016. The Pelvic Anatomy Group’s purpose is to help educate physicians about pelvic anatomy, with the overarching goal of compiling instructional materials, primarily from dissections (surgical or cadaveric), and radiologic imaging for all pelvic structures. Throughout the discussions on this initiative, it became clear that standardized terms needed to be established and used for pelvic structures.

While TA is an excellent reference work, it does not include all of the clinically relevant structures for gynecologic surgeons. As physicians, surgeons, and women’s health care providers, we read about and discuss pelvic anatomy structures in medical textbooks, medical literature, and clinical settings that are not necessarily included in TA. In addition, advances in information technology have facilitated the creation of clinically oriented computer-based anatomy programs and expanded the number and availability of electronic publications on surgical and clinical anatomy.5 As a result, there is a need not only to standardize nomenclature but also to continually revise and update terminology and integrate new terms, both from an anatomic and a clinical perspective.

The Pelvic Anatomy Group developed a novel approach to anatomic terminology. We decided to review the medical literature, identify the terms used, adjudicate the terms with current TA terms, and provide consensus for the terms and structures in the pelvis. Because of the volume of literature available and the existing number of terms, we divided the pelvis into 4 regions—anterior, apical, posterior, and vulvar—to improve the feasibility of reviewing the medical literature for the entire female pelvis.

Our process for tackling terminology

Our literature review started with the anterior compartment. (For complete details, see our prior publication.3) Modeled on a systematic review, we searched the MEDLINE database for terms related to the anterior pelvis, screened all associated abstracts, and then extracted terms from appropriate papers. We also identified several book chapters from various disciplines (anatomy, gynecology, urology, and radiology) to ensure wide representation of disciplines. We then extracted all terms pertinent to the anterior pelvis.

We organized the terms, with terms that referred to the same anatomic structure grouped together. Whenever possible, we used TA terms as the preferred terms. In this process, however, we identified several clinically relevant terms that were not included in TA: pelvic sidewall, pelvic bones, anterior compartment, pubourethral ligament, vaginal sulcus, and levator hiatus, among others. The new terms were then proposed and agreed on by members of the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group and accepted by SGS members. We currently are completing a similar process for the apical pelvis, posterior pelvis, and vulvar regions.

TA code numbers pinpoint the nomenclature

As we move forward, we suggest that physicians use TA or other approved terms for patient and research communication. Such use will help standardize anatomic terms and also will improve communication between providers and education for learners.

Continue to: TA includes approved options...

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43-54.

- Venes D, ed. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- Jeppson PC, Balgobin S, Washington BB, et al; for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Pelvic Anatomy Group. Recommended standardized terminology of the anterior female pelvis based on a structured medical literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:26-39.

- Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminologies (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2011.

- Rosse C. Terminologia Anatomica: considered from the perspective of next-generation knowledge sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14:120-133.

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43-54.

- Venes D, ed. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- Jeppson PC, Balgobin S, Washington BB, et al; for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Pelvic Anatomy Group. Recommended standardized terminology of the anterior female pelvis based on a structured medical literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:26-39.

- Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminologies (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2011.

- Rosse C. Terminologia Anatomica: considered from the perspective of next-generation knowledge sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14:120-133.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: Ready for prime time

The first cases of HIV infection in the United States were reported in 1981. Since that time, more than 700,000 individuals in our country have died of AIDS. Slightly more than 1 million persons in the United States are currently living with HIV infection; approximately 15% of them are unaware of their infection. Men who have sex with men (MSM) and African American and Hispanic/Latino men and women are disproportionately affected by HIV infection.1 Among men, MSM is the most common method of infection transmission, accounting for 83% of infections. Heterosexual contact accounts for 9.4% of new infections and injection drug use for 4.0%. Among women in the United States, heterosexual contact is the most common mechanism of transmission, accounting for about 87% of cases; injection drug use accounts for about 12%.1 Perinatal transmission rates are extremely low—less than 1%—when women receive effective treatment during pregnancy and their infants are treated in the neonatal period.1,2

The prognosis for HIV-infected patients has improved dramatically in recent years with the availability of many new and exceptionally effective highly-active antiretroviral treatment regimens. Nevertheless, the disease is not yet completely curable. Therefore, preventive measures are of great importance in reducing the enormous toll imposed by this condition.2

Evaluating effectiveness of PrEP

At the request of the US Preventive Services Task Force, Chou and colleagues recently conducted a systematic review to determine the effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in preventing the horizontal transmission of HIV infection.1 The authors’ secondary objectives included assessing the relationship between degree of adherence to the prophylactic regimen and degree of effectiveness and evaluating the accuracy of various screening systems for identifying patients at high risk for acquiring HIV infection.

The authors reviewed prospective, randomized controlled trials (treatment versus no treatment or treatment versus placebo) published through 2018. Pregnant women were excluded from the studies, as were women who became pregnant after enrollment.

Two different prophylactic regimens were used in the reviewed studies: 1) the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg or 245 mg plus emtricitabine 200 mg and 2) tenofovir 300 mg alone. Most trials used the combination regimen. With the exception of one trial, the medications were given daily to uninfected patients at high risk of acquiring HIV infection. In one investigation, the administration of prophylaxis was event driven (administered after a specific high-risk exposure).

Key study findings

PrEP decreased HIV transmission in high-risk patients. Chou and colleagues found that high-risk patients included primarily MSM who did not use condoms consistently or who had a high number of sex partners, individuals in an HIV-serodiscordant relationship, and intravenous drug users who shared injection equipment.

In these high-risk patients, PrEP was associated with a significantly decreased risk of HIV transmission. Observations from 11 trials demonstrated a relative risk (RR) of 0.46 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.33–0.66). The absolute risk reduction was -2.0% (95% CI, -2.8% to -1.2%). The duration of follow up ranged from 4 months to 4 years.

Continue to: Better medication adherence = greater prophylaxis effectiveness...

Better medication adherence = greater prophylaxis effectiveness. When adherence was ≥70%, the RR was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.19–0.39). When adherence was 40% to 70%, the RR was 0.51 (95% CI, 0.38–0.70). When adherence was ≤40%, the relative risk was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.72–1.20). Adherence was better with daily administration, as opposed to event-driven administration.

Although the combination prophylactic regimen (tenofovir plus emtricitabine) was most frequently used in the clinical trials, tenofovir alone was comparable in effectiveness.

PrEP resulted in more mild adverse effects. Patients who received PrEP were more likely to develop gastrointestinal adverse effects and renal function abnormalities when compared with patients in the control arms of the studies. These adverse effects were virtually always mild and did not necessitate discontinuation of treatment.

No increase in promiscuous sexual behavior with PrEP. Specifically, investigators did not document an increased incidence of new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in treated patients.

PrEP did not increase adverse pregnancy outcomes. In women who became pregnant while on PrEP, and who then discontinued treatment, there was no increase in the frequency of spontaneous abortion, congenital anomalies, or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In addition, PrEP posed a low risk for causing drug resistance in patients who became infected despite prophylaxis. Finally, the authors found that screening instruments for identifying patients at highest risk for acquiring HIV infection had low to modest sensitivity.

My recommendations for practice

Based on the study by Chou and colleagues, and on a recent commentary by Marcus et al, I believe that the following actions are justified1–3:

- For prophylaxis to be effective, we must identify all infected patients. Therefore, screening of asymptomatic individuals during routine health encounters is essential.

- All patients should have access to easy-to-understand information related to risk factors for HIV infection.

- Every effort should be made to promote safe sex practices, such as use of latex condoms, avoidance of sex during menses and in the presence of ulcerative genital lesions, and avoidance of use of contaminated drug-injection needles.

- All high-risk patients, as defined above, should be offered PrEP.

- To the greatest extent possible, financial barriers to PrEP should be eliminated.

- Patients receiving PrEP should be monitored for evidence of renal dysfunction. Should they become infected despite prophylaxis, they should be evaluated carefully to detect drug-resistant viral strains.

- Although PrEP is definitely effective in reducing the risk of transmission of HIV infection, it does not prevent the transmission of other STIs, such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

In my practice, I administer prophyaxis on a daily basis rather than just before, or after, a high-risk exposure. This approach enhances patient adherence and, hopefully, will lead to maximum effectiveness over time. I also use the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine rather than tenofovir alone because there is more published information regarding the effectiveness of the combination regimen.

- Chou R, Evans C, Hoverman A, et al. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Publication No. 18-05247-EF-1; November 2018.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, Green MF, Copel JA, Silver RM (eds). Creasy & Resnik's Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Principles and Practice (8th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

- Marcus JL, Katz KA, Krakower DS, et al. Risk compensation and clinical decision making--the case of HIV preexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:510-512.

The first cases of HIV infection in the United States were reported in 1981. Since that time, more than 700,000 individuals in our country have died of AIDS. Slightly more than 1 million persons in the United States are currently living with HIV infection; approximately 15% of them are unaware of their infection. Men who have sex with men (MSM) and African American and Hispanic/Latino men and women are disproportionately affected by HIV infection.1 Among men, MSM is the most common method of infection transmission, accounting for 83% of infections. Heterosexual contact accounts for 9.4% of new infections and injection drug use for 4.0%. Among women in the United States, heterosexual contact is the most common mechanism of transmission, accounting for about 87% of cases; injection drug use accounts for about 12%.1 Perinatal transmission rates are extremely low—less than 1%—when women receive effective treatment during pregnancy and their infants are treated in the neonatal period.1,2

The prognosis for HIV-infected patients has improved dramatically in recent years with the availability of many new and exceptionally effective highly-active antiretroviral treatment regimens. Nevertheless, the disease is not yet completely curable. Therefore, preventive measures are of great importance in reducing the enormous toll imposed by this condition.2

Evaluating effectiveness of PrEP

At the request of the US Preventive Services Task Force, Chou and colleagues recently conducted a systematic review to determine the effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in preventing the horizontal transmission of HIV infection.1 The authors’ secondary objectives included assessing the relationship between degree of adherence to the prophylactic regimen and degree of effectiveness and evaluating the accuracy of various screening systems for identifying patients at high risk for acquiring HIV infection.

The authors reviewed prospective, randomized controlled trials (treatment versus no treatment or treatment versus placebo) published through 2018. Pregnant women were excluded from the studies, as were women who became pregnant after enrollment.

Two different prophylactic regimens were used in the reviewed studies: 1) the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg or 245 mg plus emtricitabine 200 mg and 2) tenofovir 300 mg alone. Most trials used the combination regimen. With the exception of one trial, the medications were given daily to uninfected patients at high risk of acquiring HIV infection. In one investigation, the administration of prophylaxis was event driven (administered after a specific high-risk exposure).

Key study findings

PrEP decreased HIV transmission in high-risk patients. Chou and colleagues found that high-risk patients included primarily MSM who did not use condoms consistently or who had a high number of sex partners, individuals in an HIV-serodiscordant relationship, and intravenous drug users who shared injection equipment.

In these high-risk patients, PrEP was associated with a significantly decreased risk of HIV transmission. Observations from 11 trials demonstrated a relative risk (RR) of 0.46 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.33–0.66). The absolute risk reduction was -2.0% (95% CI, -2.8% to -1.2%). The duration of follow up ranged from 4 months to 4 years.

Continue to: Better medication adherence = greater prophylaxis effectiveness...

Better medication adherence = greater prophylaxis effectiveness. When adherence was ≥70%, the RR was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.19–0.39). When adherence was 40% to 70%, the RR was 0.51 (95% CI, 0.38–0.70). When adherence was ≤40%, the relative risk was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.72–1.20). Adherence was better with daily administration, as opposed to event-driven administration.

Although the combination prophylactic regimen (tenofovir plus emtricitabine) was most frequently used in the clinical trials, tenofovir alone was comparable in effectiveness.

PrEP resulted in more mild adverse effects. Patients who received PrEP were more likely to develop gastrointestinal adverse effects and renal function abnormalities when compared with patients in the control arms of the studies. These adverse effects were virtually always mild and did not necessitate discontinuation of treatment.

No increase in promiscuous sexual behavior with PrEP. Specifically, investigators did not document an increased incidence of new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in treated patients.

PrEP did not increase adverse pregnancy outcomes. In women who became pregnant while on PrEP, and who then discontinued treatment, there was no increase in the frequency of spontaneous abortion, congenital anomalies, or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In addition, PrEP posed a low risk for causing drug resistance in patients who became infected despite prophylaxis. Finally, the authors found that screening instruments for identifying patients at highest risk for acquiring HIV infection had low to modest sensitivity.

My recommendations for practice

Based on the study by Chou and colleagues, and on a recent commentary by Marcus et al, I believe that the following actions are justified1–3:

- For prophylaxis to be effective, we must identify all infected patients. Therefore, screening of asymptomatic individuals during routine health encounters is essential.

- All patients should have access to easy-to-understand information related to risk factors for HIV infection.

- Every effort should be made to promote safe sex practices, such as use of latex condoms, avoidance of sex during menses and in the presence of ulcerative genital lesions, and avoidance of use of contaminated drug-injection needles.

- All high-risk patients, as defined above, should be offered PrEP.

- To the greatest extent possible, financial barriers to PrEP should be eliminated.

- Patients receiving PrEP should be monitored for evidence of renal dysfunction. Should they become infected despite prophylaxis, they should be evaluated carefully to detect drug-resistant viral strains.

- Although PrEP is definitely effective in reducing the risk of transmission of HIV infection, it does not prevent the transmission of other STIs, such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

In my practice, I administer prophyaxis on a daily basis rather than just before, or after, a high-risk exposure. This approach enhances patient adherence and, hopefully, will lead to maximum effectiveness over time. I also use the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine rather than tenofovir alone because there is more published information regarding the effectiveness of the combination regimen.

The first cases of HIV infection in the United States were reported in 1981. Since that time, more than 700,000 individuals in our country have died of AIDS. Slightly more than 1 million persons in the United States are currently living with HIV infection; approximately 15% of them are unaware of their infection. Men who have sex with men (MSM) and African American and Hispanic/Latino men and women are disproportionately affected by HIV infection.1 Among men, MSM is the most common method of infection transmission, accounting for 83% of infections. Heterosexual contact accounts for 9.4% of new infections and injection drug use for 4.0%. Among women in the United States, heterosexual contact is the most common mechanism of transmission, accounting for about 87% of cases; injection drug use accounts for about 12%.1 Perinatal transmission rates are extremely low—less than 1%—when women receive effective treatment during pregnancy and their infants are treated in the neonatal period.1,2

The prognosis for HIV-infected patients has improved dramatically in recent years with the availability of many new and exceptionally effective highly-active antiretroviral treatment regimens. Nevertheless, the disease is not yet completely curable. Therefore, preventive measures are of great importance in reducing the enormous toll imposed by this condition.2

Evaluating effectiveness of PrEP

At the request of the US Preventive Services Task Force, Chou and colleagues recently conducted a systematic review to determine the effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in preventing the horizontal transmission of HIV infection.1 The authors’ secondary objectives included assessing the relationship between degree of adherence to the prophylactic regimen and degree of effectiveness and evaluating the accuracy of various screening systems for identifying patients at high risk for acquiring HIV infection.

The authors reviewed prospective, randomized controlled trials (treatment versus no treatment or treatment versus placebo) published through 2018. Pregnant women were excluded from the studies, as were women who became pregnant after enrollment.

Two different prophylactic regimens were used in the reviewed studies: 1) the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg or 245 mg plus emtricitabine 200 mg and 2) tenofovir 300 mg alone. Most trials used the combination regimen. With the exception of one trial, the medications were given daily to uninfected patients at high risk of acquiring HIV infection. In one investigation, the administration of prophylaxis was event driven (administered after a specific high-risk exposure).

Key study findings

PrEP decreased HIV transmission in high-risk patients. Chou and colleagues found that high-risk patients included primarily MSM who did not use condoms consistently or who had a high number of sex partners, individuals in an HIV-serodiscordant relationship, and intravenous drug users who shared injection equipment.

In these high-risk patients, PrEP was associated with a significantly decreased risk of HIV transmission. Observations from 11 trials demonstrated a relative risk (RR) of 0.46 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.33–0.66). The absolute risk reduction was -2.0% (95% CI, -2.8% to -1.2%). The duration of follow up ranged from 4 months to 4 years.

Continue to: Better medication adherence = greater prophylaxis effectiveness...

Better medication adherence = greater prophylaxis effectiveness. When adherence was ≥70%, the RR was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.19–0.39). When adherence was 40% to 70%, the RR was 0.51 (95% CI, 0.38–0.70). When adherence was ≤40%, the relative risk was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.72–1.20). Adherence was better with daily administration, as opposed to event-driven administration.

Although the combination prophylactic regimen (tenofovir plus emtricitabine) was most frequently used in the clinical trials, tenofovir alone was comparable in effectiveness.

PrEP resulted in more mild adverse effects. Patients who received PrEP were more likely to develop gastrointestinal adverse effects and renal function abnormalities when compared with patients in the control arms of the studies. These adverse effects were virtually always mild and did not necessitate discontinuation of treatment.

No increase in promiscuous sexual behavior with PrEP. Specifically, investigators did not document an increased incidence of new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in treated patients.

PrEP did not increase adverse pregnancy outcomes. In women who became pregnant while on PrEP, and who then discontinued treatment, there was no increase in the frequency of spontaneous abortion, congenital anomalies, or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.