User login

Subungual Nodule in a Pediatric Patient

The Diagnosis: Subungual Exostosis

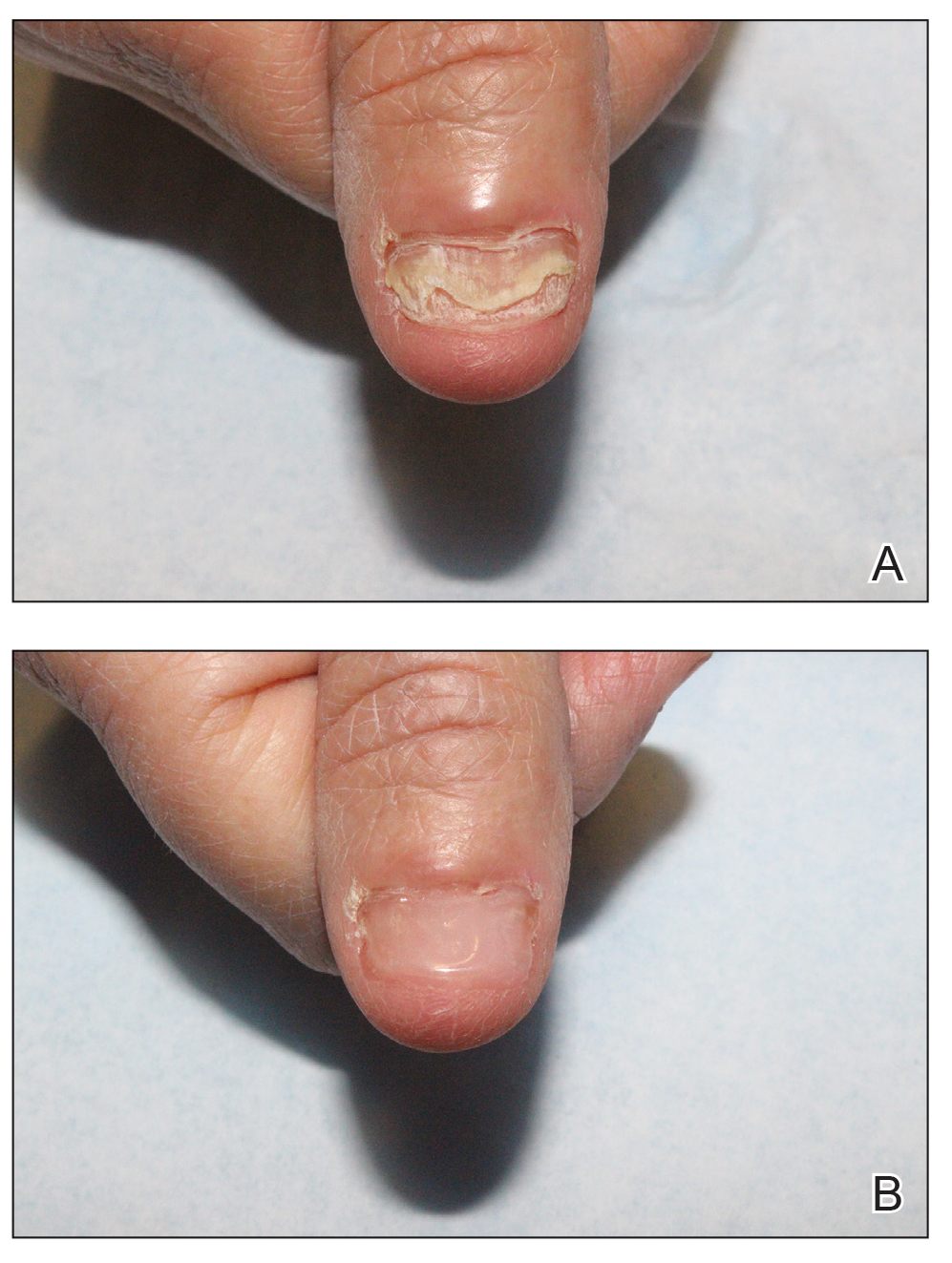

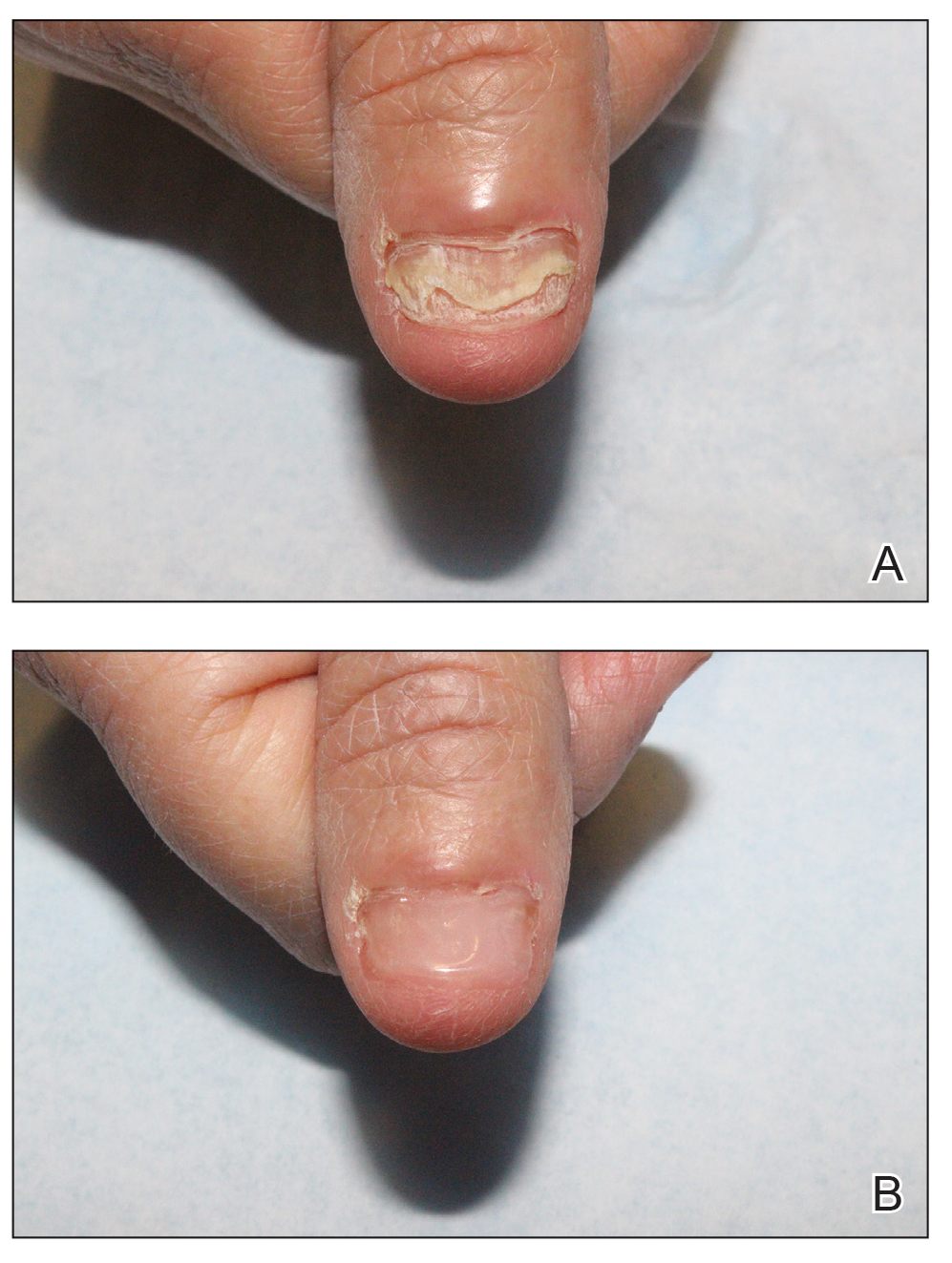

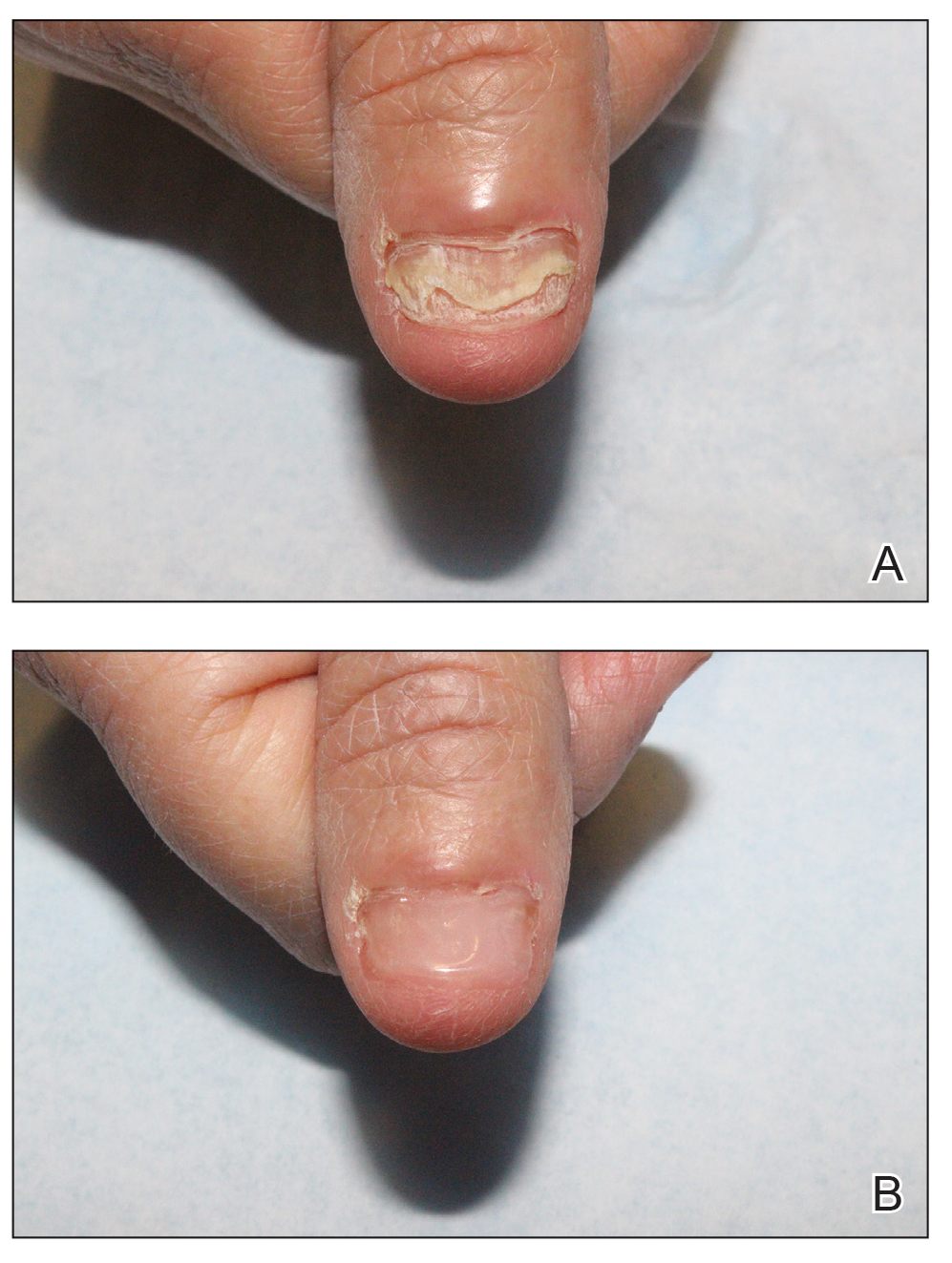

Subungual exostosis should be considered as a possible cause of an exophytic subungual nodule in a young active female. In our patient, the involvement of the great toe was a clue, as the hallux is the most common location of subungual exostosis. The patient’s age and sex also were supportive, as subungual exostosis is most common in female children and adolescents— particularly those who are active, as trauma is thought to play a possible role in development of this benign tumor.1-3 Radiography is the preferred modality for diagnosis; in our case, it showed a trabecular bony overgrowth (Figure 1), which confirmed the diagnosis. Subungual exostosis is a rare, benign, osteocartilaginous tumor of trabecular bone. The etiology is unknown but is hypothesized to be related to trauma, infection, or activation of a cartilaginous cyst.1,3 The subungual nodule may be asymptomatic or painful. Disruption and elevation of the nail plate is common.4 The differential diagnosis includes amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, fibrokeratoma, osteochondroma, pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, glomus tumor, and verruca vulgaris, among others.5

Physical examination demonstrates a firm, fixed, subungual nodule, often with an accompanying nail deformity. Further workup is required to confirm the benign nature of the lesion and exclude nail tumors such as melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Radiography is the gold standard for diagnosis, demonstrating a trabecular bony overgrowth.6 Performing a radiograph as the initial diagnostic test spares the patient from unnecessary procedures such as biopsy or expensive imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging. Early lesions may not demonstrate sufficient bone formation shown on radiography. In these situations, a combination of dermoscopy and histopathologic examination may aid in diagnosis (Figure 2).4 Vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration are the most common findings on dermoscopy (in ascending order).7 Histopathology typically demonstrates a base or stalk of normal-appearing trabecular bone with a fibrocartilage cap.8 However, initial clinical workup via radiography allows for the least-invasive and highest-yield intervention. Clinical suspicion for this condition is important, as it can be diagnosed with noninvasive inexpensive imaging rather than biopsy or more specialized imaging modalities. Appropriate recognition can save young patients from unnecessary and expensive procedures. Treatment typically involves surgical excision; to prevent regrowth, removal of the lesion at the base of the bone is recommended.2

Although amelanotic melanoma also can manifest as a subungual nail tumor, it would be unusual in a young child and would not be expected to show characteristic changes on radiography. A glomus tumor would be painful, is more common on the fingers than on the toes, and typically has a bluish hue.9 Verruca vulgaris can occur subungually but is more common around the nailfold and often has the characteristic dermoscopic finding of thrombosed capillaries. It also would not be expected to show characteristic radiographic findings. Osteochondroma can occur in young patients and can appear clinically similar to subungual exostosis; however, it typically is painful.10

- Pascoal D, Balaco I, Alves C, et al. Subungual exostosis—treatment results with preservation of the nail bed. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020;29:382-386.

- Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257.

- Chiheb S, Slimani Y, Karam R, et al. Subungual exostosis: a case series of 48 patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:475-479.

- Zhang W, Gu L, Fan H, et al. Subungual exostosis with an unusual dermoscopic feature. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:725-726.

- Demirdag HG, Tugrul Ayanoglu B, Akay BN. Dermoscopic features of subungual exostosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E138-E141.

- Tritto M, Mirkin G, Hao X. Subungual exostosis on the right hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2021;111.

- Piccolo V, Argenziano G, Alessandrini AM, et al. Dermoscopy of subungual exostosis: a retrospective study of 10 patients. Dermatology. 2017;233:80-85.

- Lee SK, Jung MS, Lee YH, et al. Two distinctive subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:595-601. doi:10.3113/FAI.2007.0595

- Samaniego E, Crespo A, Sanz A. Key diagnostic features and treatment of subungual glomus tumor. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:875-882.

- Glick S. Subungual osteochondroma of the third toe. Consult.360. 2013;12.

The Diagnosis: Subungual Exostosis

Subungual exostosis should be considered as a possible cause of an exophytic subungual nodule in a young active female. In our patient, the involvement of the great toe was a clue, as the hallux is the most common location of subungual exostosis. The patient’s age and sex also were supportive, as subungual exostosis is most common in female children and adolescents— particularly those who are active, as trauma is thought to play a possible role in development of this benign tumor.1-3 Radiography is the preferred modality for diagnosis; in our case, it showed a trabecular bony overgrowth (Figure 1), which confirmed the diagnosis. Subungual exostosis is a rare, benign, osteocartilaginous tumor of trabecular bone. The etiology is unknown but is hypothesized to be related to trauma, infection, or activation of a cartilaginous cyst.1,3 The subungual nodule may be asymptomatic or painful. Disruption and elevation of the nail plate is common.4 The differential diagnosis includes amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, fibrokeratoma, osteochondroma, pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, glomus tumor, and verruca vulgaris, among others.5

Physical examination demonstrates a firm, fixed, subungual nodule, often with an accompanying nail deformity. Further workup is required to confirm the benign nature of the lesion and exclude nail tumors such as melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Radiography is the gold standard for diagnosis, demonstrating a trabecular bony overgrowth.6 Performing a radiograph as the initial diagnostic test spares the patient from unnecessary procedures such as biopsy or expensive imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging. Early lesions may not demonstrate sufficient bone formation shown on radiography. In these situations, a combination of dermoscopy and histopathologic examination may aid in diagnosis (Figure 2).4 Vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration are the most common findings on dermoscopy (in ascending order).7 Histopathology typically demonstrates a base or stalk of normal-appearing trabecular bone with a fibrocartilage cap.8 However, initial clinical workup via radiography allows for the least-invasive and highest-yield intervention. Clinical suspicion for this condition is important, as it can be diagnosed with noninvasive inexpensive imaging rather than biopsy or more specialized imaging modalities. Appropriate recognition can save young patients from unnecessary and expensive procedures. Treatment typically involves surgical excision; to prevent regrowth, removal of the lesion at the base of the bone is recommended.2

Although amelanotic melanoma also can manifest as a subungual nail tumor, it would be unusual in a young child and would not be expected to show characteristic changes on radiography. A glomus tumor would be painful, is more common on the fingers than on the toes, and typically has a bluish hue.9 Verruca vulgaris can occur subungually but is more common around the nailfold and often has the characteristic dermoscopic finding of thrombosed capillaries. It also would not be expected to show characteristic radiographic findings. Osteochondroma can occur in young patients and can appear clinically similar to subungual exostosis; however, it typically is painful.10

The Diagnosis: Subungual Exostosis

Subungual exostosis should be considered as a possible cause of an exophytic subungual nodule in a young active female. In our patient, the involvement of the great toe was a clue, as the hallux is the most common location of subungual exostosis. The patient’s age and sex also were supportive, as subungual exostosis is most common in female children and adolescents— particularly those who are active, as trauma is thought to play a possible role in development of this benign tumor.1-3 Radiography is the preferred modality for diagnosis; in our case, it showed a trabecular bony overgrowth (Figure 1), which confirmed the diagnosis. Subungual exostosis is a rare, benign, osteocartilaginous tumor of trabecular bone. The etiology is unknown but is hypothesized to be related to trauma, infection, or activation of a cartilaginous cyst.1,3 The subungual nodule may be asymptomatic or painful. Disruption and elevation of the nail plate is common.4 The differential diagnosis includes amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, fibrokeratoma, osteochondroma, pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, glomus tumor, and verruca vulgaris, among others.5

Physical examination demonstrates a firm, fixed, subungual nodule, often with an accompanying nail deformity. Further workup is required to confirm the benign nature of the lesion and exclude nail tumors such as melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Radiography is the gold standard for diagnosis, demonstrating a trabecular bony overgrowth.6 Performing a radiograph as the initial diagnostic test spares the patient from unnecessary procedures such as biopsy or expensive imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging. Early lesions may not demonstrate sufficient bone formation shown on radiography. In these situations, a combination of dermoscopy and histopathologic examination may aid in diagnosis (Figure 2).4 Vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration are the most common findings on dermoscopy (in ascending order).7 Histopathology typically demonstrates a base or stalk of normal-appearing trabecular bone with a fibrocartilage cap.8 However, initial clinical workup via radiography allows for the least-invasive and highest-yield intervention. Clinical suspicion for this condition is important, as it can be diagnosed with noninvasive inexpensive imaging rather than biopsy or more specialized imaging modalities. Appropriate recognition can save young patients from unnecessary and expensive procedures. Treatment typically involves surgical excision; to prevent regrowth, removal of the lesion at the base of the bone is recommended.2

Although amelanotic melanoma also can manifest as a subungual nail tumor, it would be unusual in a young child and would not be expected to show characteristic changes on radiography. A glomus tumor would be painful, is more common on the fingers than on the toes, and typically has a bluish hue.9 Verruca vulgaris can occur subungually but is more common around the nailfold and often has the characteristic dermoscopic finding of thrombosed capillaries. It also would not be expected to show characteristic radiographic findings. Osteochondroma can occur in young patients and can appear clinically similar to subungual exostosis; however, it typically is painful.10

- Pascoal D, Balaco I, Alves C, et al. Subungual exostosis—treatment results with preservation of the nail bed. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020;29:382-386.

- Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257.

- Chiheb S, Slimani Y, Karam R, et al. Subungual exostosis: a case series of 48 patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:475-479.

- Zhang W, Gu L, Fan H, et al. Subungual exostosis with an unusual dermoscopic feature. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:725-726.

- Demirdag HG, Tugrul Ayanoglu B, Akay BN. Dermoscopic features of subungual exostosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E138-E141.

- Tritto M, Mirkin G, Hao X. Subungual exostosis on the right hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2021;111.

- Piccolo V, Argenziano G, Alessandrini AM, et al. Dermoscopy of subungual exostosis: a retrospective study of 10 patients. Dermatology. 2017;233:80-85.

- Lee SK, Jung MS, Lee YH, et al. Two distinctive subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:595-601. doi:10.3113/FAI.2007.0595

- Samaniego E, Crespo A, Sanz A. Key diagnostic features and treatment of subungual glomus tumor. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:875-882.

- Glick S. Subungual osteochondroma of the third toe. Consult.360. 2013;12.

- Pascoal D, Balaco I, Alves C, et al. Subungual exostosis—treatment results with preservation of the nail bed. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020;29:382-386.

- Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257.

- Chiheb S, Slimani Y, Karam R, et al. Subungual exostosis: a case series of 48 patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:475-479.

- Zhang W, Gu L, Fan H, et al. Subungual exostosis with an unusual dermoscopic feature. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:725-726.

- Demirdag HG, Tugrul Ayanoglu B, Akay BN. Dermoscopic features of subungual exostosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E138-E141.

- Tritto M, Mirkin G, Hao X. Subungual exostosis on the right hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2021;111.

- Piccolo V, Argenziano G, Alessandrini AM, et al. Dermoscopy of subungual exostosis: a retrospective study of 10 patients. Dermatology. 2017;233:80-85.

- Lee SK, Jung MS, Lee YH, et al. Two distinctive subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:595-601. doi:10.3113/FAI.2007.0595

- Samaniego E, Crespo A, Sanz A. Key diagnostic features and treatment of subungual glomus tumor. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:875-882.

- Glick S. Subungual osteochondroma of the third toe. Consult.360. 2013;12.

A 13-year-old girl presented to her pediatrician with a small pink bump under the left great toenail of 8 months’ duration that was slowly growing. Months later, she developed an ingrown nail on the same toe, which was treated with partial nail avulsion by the pediatrician. Given continued nail dystrophy and a visible bump under the nail, the patient was referred to dermatology. Physical examination revealed a subungual, flesh-colored, sessile nodule causing distortion of the nail plate on the left great toe with associated intermittent redness and swelling. She denied wearing new shoes or experiencing any pain, pruritus, or purulent drainage or bleeding from the lesion. She reported being physically active and playing tennis.

Dupilumab Evaluated as Treatment for Pediatric Alopecia Areata

showed.

“We might be opening a new avenue for a safe, long-term treatment for our children with AA,” the study’s lead investigator, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor and chair of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, said in an interview during the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID), where the results were presented during a poster session. “I think AA is likely joining the atopic march, which may allow us to adapt some treatments from the atopy world to AA.”

When the original phase 2 and phase 3 trials of dupilumab for patients with moderate to severe AD were being conducted, Dr. Guttman-Yassky, one of the investigators, recalled observing that some patients who also had patch alopecia experienced hair regrowth. “I was scratching my head because, at the time, AA was considered to be only a Th1-driven disease,” she said. “I asked myself, ‘How can this happen?’ I looked in the literature and found many publications linking atopy in general to alopecia areata. The largest of the dermatologic publications showed that eczema and atopy in general are the highest comorbidities in alopecia areata.”

“This and other findings such as IL [interleukin]-13 genetic linkage with AA and high IgE in patients with AA link AA with Th2 immune skewing, particularly in the setting of atopy,” she continued. In addition, she said, in a large biomarker study involving the scalp and blood of patients with AA, “we found increases in Th2 biomarkers that were associated with alopecia severity.”

Case Series of 20 Pediatric Patients

As part of a case series of children with both AD and AA, Dr. Guttman-Yassky and colleagues evaluated hair regrowth using the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) in 20 pediatric patients (mean age, 10.8 years) who were being treated at Mount Sinai. They collected patient demographics, atopic history, immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, and SALT scores at follow-up visits every 12-16 weeks for more than 72 weeks and performed Spearman correlations between clinical scores, demographics, and IgE levels.

At baseline, the mean SALT score was 54.4, the mean IgE level was 1567.7 IU/mL, and 75% of patients also had a family history of atopy. The mean follow-up was 67.6 weeks. The researchers observed a significant reduction in SALT scores at week 48 compared with baseline (a mean score of 20.4; P < .01) and continued improvement up to at least 72 weeks (P < .01 vs baseline). They also noted that patients who achieved a treatment response at week 24 had baseline IgE levels > 200 IU/mL.

In other findings, baseline IgE positively correlated with improvement in SALT scores at week 36 (P < .05), while baseline SALT scores positively correlated with disease duration (P < .01) and negatively correlated with improvement in SALT scores at weeks 24, 36, and 48 (P < .005). “The robustness of the response surprised me,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said in the interview. “Dupilumab for AA takes time to work, but once it kicks in, it kicks in. It takes anywhere from 6 to 12 months to see hair regrowth.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its small sample size and the fact that it was not a standardized trial. “But, based on our data and the adult data, we are very encouraged about the potential of using dupilumab for children with AA,” she said.

Mount Sinai recently announced that the National Institutes of Health awarded a $6.6 million, 5-year grant to Dr. Guttman-Yassky to further investigate dupilumab as a treatment for children with AA. She will lead a multicenter controlled trial of 76 children with alopecia affecting at least 30% of the scalp, who will be randomized 2:1 (dupilumab:placebo) for 48 weeks, followed by 48 weeks of open-label dupilumab for all participants, with 16 weeks of follow-up, for a total of 112 weeks. Participating sites include Mount Sinai, Yale University, Northwestern University, and the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky disclosed that she is a consultant to many pharmaceutical companies, including dupilumab manufacturers Sanofi and Regeneron.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

showed.

“We might be opening a new avenue for a safe, long-term treatment for our children with AA,” the study’s lead investigator, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor and chair of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, said in an interview during the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID), where the results were presented during a poster session. “I think AA is likely joining the atopic march, which may allow us to adapt some treatments from the atopy world to AA.”

When the original phase 2 and phase 3 trials of dupilumab for patients with moderate to severe AD were being conducted, Dr. Guttman-Yassky, one of the investigators, recalled observing that some patients who also had patch alopecia experienced hair regrowth. “I was scratching my head because, at the time, AA was considered to be only a Th1-driven disease,” she said. “I asked myself, ‘How can this happen?’ I looked in the literature and found many publications linking atopy in general to alopecia areata. The largest of the dermatologic publications showed that eczema and atopy in general are the highest comorbidities in alopecia areata.”

“This and other findings such as IL [interleukin]-13 genetic linkage with AA and high IgE in patients with AA link AA with Th2 immune skewing, particularly in the setting of atopy,” she continued. In addition, she said, in a large biomarker study involving the scalp and blood of patients with AA, “we found increases in Th2 biomarkers that were associated with alopecia severity.”

Case Series of 20 Pediatric Patients

As part of a case series of children with both AD and AA, Dr. Guttman-Yassky and colleagues evaluated hair regrowth using the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) in 20 pediatric patients (mean age, 10.8 years) who were being treated at Mount Sinai. They collected patient demographics, atopic history, immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, and SALT scores at follow-up visits every 12-16 weeks for more than 72 weeks and performed Spearman correlations between clinical scores, demographics, and IgE levels.

At baseline, the mean SALT score was 54.4, the mean IgE level was 1567.7 IU/mL, and 75% of patients also had a family history of atopy. The mean follow-up was 67.6 weeks. The researchers observed a significant reduction in SALT scores at week 48 compared with baseline (a mean score of 20.4; P < .01) and continued improvement up to at least 72 weeks (P < .01 vs baseline). They also noted that patients who achieved a treatment response at week 24 had baseline IgE levels > 200 IU/mL.

In other findings, baseline IgE positively correlated with improvement in SALT scores at week 36 (P < .05), while baseline SALT scores positively correlated with disease duration (P < .01) and negatively correlated with improvement in SALT scores at weeks 24, 36, and 48 (P < .005). “The robustness of the response surprised me,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said in the interview. “Dupilumab for AA takes time to work, but once it kicks in, it kicks in. It takes anywhere from 6 to 12 months to see hair regrowth.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its small sample size and the fact that it was not a standardized trial. “But, based on our data and the adult data, we are very encouraged about the potential of using dupilumab for children with AA,” she said.

Mount Sinai recently announced that the National Institutes of Health awarded a $6.6 million, 5-year grant to Dr. Guttman-Yassky to further investigate dupilumab as a treatment for children with AA. She will lead a multicenter controlled trial of 76 children with alopecia affecting at least 30% of the scalp, who will be randomized 2:1 (dupilumab:placebo) for 48 weeks, followed by 48 weeks of open-label dupilumab for all participants, with 16 weeks of follow-up, for a total of 112 weeks. Participating sites include Mount Sinai, Yale University, Northwestern University, and the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky disclosed that she is a consultant to many pharmaceutical companies, including dupilumab manufacturers Sanofi and Regeneron.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

showed.

“We might be opening a new avenue for a safe, long-term treatment for our children with AA,” the study’s lead investigator, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor and chair of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, said in an interview during the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID), where the results were presented during a poster session. “I think AA is likely joining the atopic march, which may allow us to adapt some treatments from the atopy world to AA.”

When the original phase 2 and phase 3 trials of dupilumab for patients with moderate to severe AD were being conducted, Dr. Guttman-Yassky, one of the investigators, recalled observing that some patients who also had patch alopecia experienced hair regrowth. “I was scratching my head because, at the time, AA was considered to be only a Th1-driven disease,” she said. “I asked myself, ‘How can this happen?’ I looked in the literature and found many publications linking atopy in general to alopecia areata. The largest of the dermatologic publications showed that eczema and atopy in general are the highest comorbidities in alopecia areata.”

“This and other findings such as IL [interleukin]-13 genetic linkage with AA and high IgE in patients with AA link AA with Th2 immune skewing, particularly in the setting of atopy,” she continued. In addition, she said, in a large biomarker study involving the scalp and blood of patients with AA, “we found increases in Th2 biomarkers that were associated with alopecia severity.”

Case Series of 20 Pediatric Patients

As part of a case series of children with both AD and AA, Dr. Guttman-Yassky and colleagues evaluated hair regrowth using the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) in 20 pediatric patients (mean age, 10.8 years) who were being treated at Mount Sinai. They collected patient demographics, atopic history, immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, and SALT scores at follow-up visits every 12-16 weeks for more than 72 weeks and performed Spearman correlations between clinical scores, demographics, and IgE levels.

At baseline, the mean SALT score was 54.4, the mean IgE level was 1567.7 IU/mL, and 75% of patients also had a family history of atopy. The mean follow-up was 67.6 weeks. The researchers observed a significant reduction in SALT scores at week 48 compared with baseline (a mean score of 20.4; P < .01) and continued improvement up to at least 72 weeks (P < .01 vs baseline). They also noted that patients who achieved a treatment response at week 24 had baseline IgE levels > 200 IU/mL.

In other findings, baseline IgE positively correlated with improvement in SALT scores at week 36 (P < .05), while baseline SALT scores positively correlated with disease duration (P < .01) and negatively correlated with improvement in SALT scores at weeks 24, 36, and 48 (P < .005). “The robustness of the response surprised me,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said in the interview. “Dupilumab for AA takes time to work, but once it kicks in, it kicks in. It takes anywhere from 6 to 12 months to see hair regrowth.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its small sample size and the fact that it was not a standardized trial. “But, based on our data and the adult data, we are very encouraged about the potential of using dupilumab for children with AA,” she said.

Mount Sinai recently announced that the National Institutes of Health awarded a $6.6 million, 5-year grant to Dr. Guttman-Yassky to further investigate dupilumab as a treatment for children with AA. She will lead a multicenter controlled trial of 76 children with alopecia affecting at least 30% of the scalp, who will be randomized 2:1 (dupilumab:placebo) for 48 weeks, followed by 48 weeks of open-label dupilumab for all participants, with 16 weeks of follow-up, for a total of 112 weeks. Participating sites include Mount Sinai, Yale University, Northwestern University, and the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky disclosed that she is a consultant to many pharmaceutical companies, including dupilumab manufacturers Sanofi and Regeneron.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SID 2024

Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: Study Finds Oral Contraceptive Use Modulates Risk In Women with Genetic Variant

TOPLINE:

Investigators found that .

METHODOLOGY:

- OC use has been considered a possible factor behind the increased incidence of FFA because it was first documented in 1994, and a recent genome-wide association study of FFA identified a signal for an association with a variant in CYP1B1.

- The same researchers conducted a gene-environment interaction study with a case-control design involving 489 White female patients (mean age, 65.8 years) with FFA and 34,254 controls, matched for age and genetic ancestry.

- Data were collected from July 2015 to September 2017 and analyzed from October 2022 to December 2023.

- The study aimed to investigate the modulatory effect of OC use on the CYP1B1 variant’s impact on FFA risk, using logistic regression models for analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The use of OCs was associated with a 1.9 times greater risk for FFA in individuals with the specific CYP1B1 genetic variant, but there was no association among those with no history of OC use.

- The study suggests a significant gene-environment interaction, indicating that OC use may influence FFA risk in genetically predisposed individuals.

IN PRACTICE:

“This gene-environment interaction analysis suggests that the protective effect of the CYPIB1 missense variant on FFA risk might be mediated by exposure” to OCs, the authors wrote. The study, they added, “underscores the importance of considering genetic predispositions and environmental factors, such as oral contraceptive use, in understanding and managing frontal fibrosing alopecia.”

SOURCE:

Tuntas Rayinda, MD, MSc, PhD, of St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, King’s College London, led the study, which was published online May 29, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s reliance on self-reported OC use may have introduced recall and differences in ascertainment of OC use between patient and control groups and could have affected the study’s findings. The study also did not collect information on the type of OC used, which could have influenced the observed interaction.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the British Skin Foundation Young Investigator Award. One investigator reported being a subinvestigator on an alopecia areata study funded by Pfizer. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Investigators found that .

METHODOLOGY:

- OC use has been considered a possible factor behind the increased incidence of FFA because it was first documented in 1994, and a recent genome-wide association study of FFA identified a signal for an association with a variant in CYP1B1.

- The same researchers conducted a gene-environment interaction study with a case-control design involving 489 White female patients (mean age, 65.8 years) with FFA and 34,254 controls, matched for age and genetic ancestry.

- Data were collected from July 2015 to September 2017 and analyzed from October 2022 to December 2023.

- The study aimed to investigate the modulatory effect of OC use on the CYP1B1 variant’s impact on FFA risk, using logistic regression models for analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The use of OCs was associated with a 1.9 times greater risk for FFA in individuals with the specific CYP1B1 genetic variant, but there was no association among those with no history of OC use.

- The study suggests a significant gene-environment interaction, indicating that OC use may influence FFA risk in genetically predisposed individuals.

IN PRACTICE:

“This gene-environment interaction analysis suggests that the protective effect of the CYPIB1 missense variant on FFA risk might be mediated by exposure” to OCs, the authors wrote. The study, they added, “underscores the importance of considering genetic predispositions and environmental factors, such as oral contraceptive use, in understanding and managing frontal fibrosing alopecia.”

SOURCE:

Tuntas Rayinda, MD, MSc, PhD, of St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, King’s College London, led the study, which was published online May 29, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s reliance on self-reported OC use may have introduced recall and differences in ascertainment of OC use between patient and control groups and could have affected the study’s findings. The study also did not collect information on the type of OC used, which could have influenced the observed interaction.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the British Skin Foundation Young Investigator Award. One investigator reported being a subinvestigator on an alopecia areata study funded by Pfizer. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Investigators found that .

METHODOLOGY:

- OC use has been considered a possible factor behind the increased incidence of FFA because it was first documented in 1994, and a recent genome-wide association study of FFA identified a signal for an association with a variant in CYP1B1.

- The same researchers conducted a gene-environment interaction study with a case-control design involving 489 White female patients (mean age, 65.8 years) with FFA and 34,254 controls, matched for age and genetic ancestry.

- Data were collected from July 2015 to September 2017 and analyzed from October 2022 to December 2023.

- The study aimed to investigate the modulatory effect of OC use on the CYP1B1 variant’s impact on FFA risk, using logistic regression models for analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The use of OCs was associated with a 1.9 times greater risk for FFA in individuals with the specific CYP1B1 genetic variant, but there was no association among those with no history of OC use.

- The study suggests a significant gene-environment interaction, indicating that OC use may influence FFA risk in genetically predisposed individuals.

IN PRACTICE:

“This gene-environment interaction analysis suggests that the protective effect of the CYPIB1 missense variant on FFA risk might be mediated by exposure” to OCs, the authors wrote. The study, they added, “underscores the importance of considering genetic predispositions and environmental factors, such as oral contraceptive use, in understanding and managing frontal fibrosing alopecia.”

SOURCE:

Tuntas Rayinda, MD, MSc, PhD, of St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, King’s College London, led the study, which was published online May 29, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s reliance on self-reported OC use may have introduced recall and differences in ascertainment of OC use between patient and control groups and could have affected the study’s findings. The study also did not collect information on the type of OC used, which could have influenced the observed interaction.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the British Skin Foundation Young Investigator Award. One investigator reported being a subinvestigator on an alopecia areata study funded by Pfizer. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

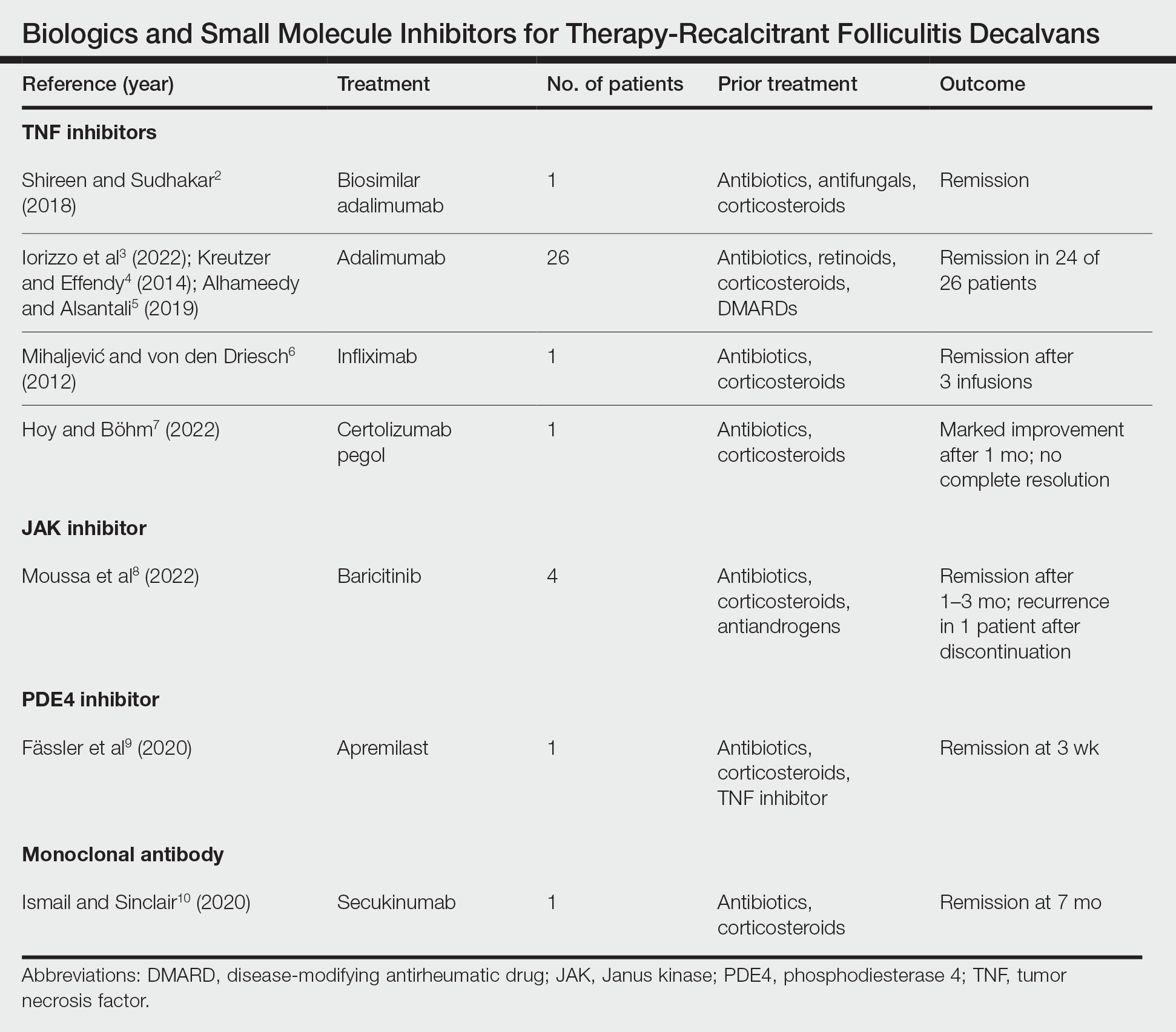

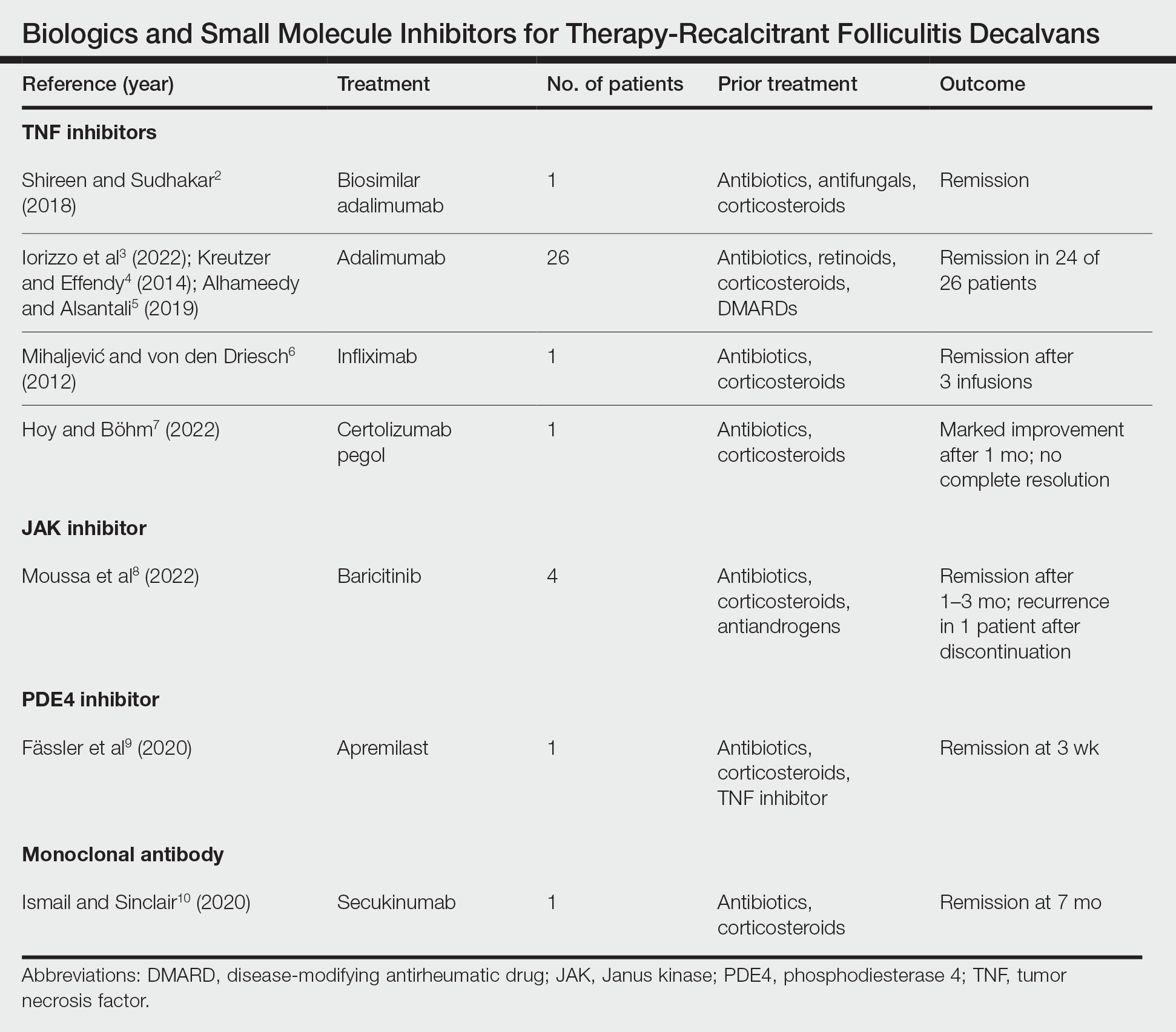

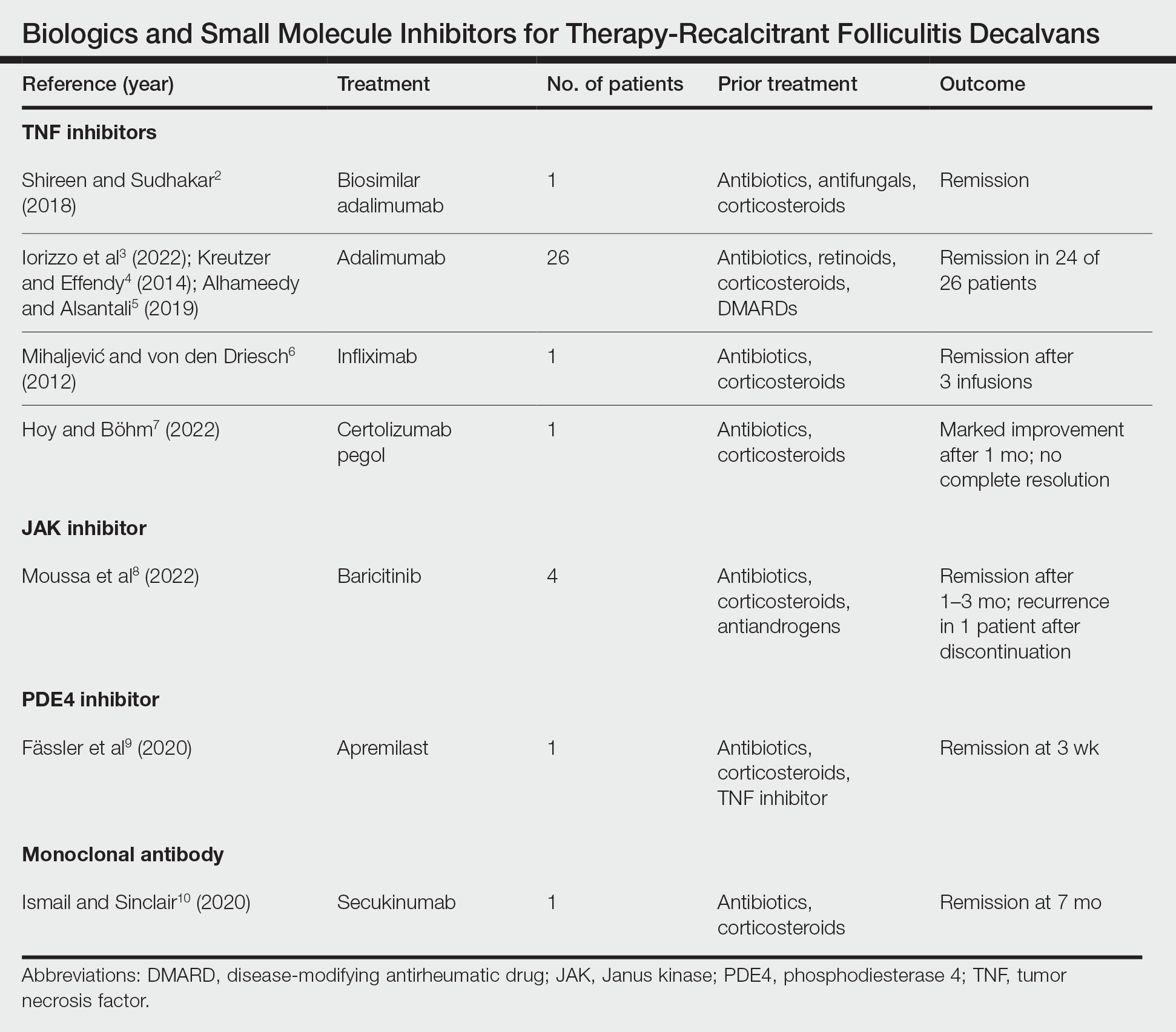

Recalcitrant Folliculitis Decalvans Treatment Outcomes With Biologics and Small Molecule Inhibitors

Folliculitis decalvans (FD) is classified as a rare primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia occurring predominantly in middle-aged adults. Although the true etiology is still unknown, the pathogenesis behind the inflammatory follicular lesions stems from possible Staphylococcus aureus infection and an impaired host immune system in response to released superantigens. 1 The clinical severity of this inflammatory scalp disorder can range from mild to severe and debilitating. Multiple treatment regimens have been developed with the goal of maintaining full remission. We provide a summary of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies being utilized for patients with therapy-recalcitrant FD.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar search for the terms refractory FD, recalcitrant FD, or therapy-resistant FD to identify articles published in English from 1998 to 2022. Articles that reported recalcitrant cases and subsequent therapy with TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies were included. Articles were excluded if recalcitrant cases were not clearly defined. Remission was defined as no recurrence in lesions or pustules or as a reduction in the inflammatory process with stabilization upon continuation or discontinuation of the therapy regimen. Two reviewers (T.F. and K.U.) independently searched for and screened each report.

Results

Treatment of recalcitrant FD with biologics or small molecule inhibitors was discussed in 9 studies with a combined total of 35 patients.2-10 The treatment regimens included TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies (Table).

The TNF inhibitors were utilized in 6 reports with a combined total of 29 patients. Treatments included adalimumab or biosimilar adalimumab (27/29 patients), infliximab (1/29 patients), and certolizumab pegol (1/29 patients). Remission was reported in 26 of 29 cases. There were 2 nonresponders to adalimumab and marked improvement with certolizumab pegol without complete resolution. The use of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib in 4 patients resulted in remission. In all 4 patients, baricitinib was used with concurrent treatments, and remission was achieved in an average of 2.25 months. The use of a PDE4 inhibitor, apremilast, was reported in 1 case; remission was achieved in 3 weeks. Secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-17, was utilized in 1 patient. Marked improvement was seen after 2 months, with complete remission in 7 months.

Comment

Traditional treatment regimens for FD most often include a combination of topical and oral antibiotics; isotretinoin; and oral, topical, or intralesional corticosteroids. In the past, interventions typically were suppressive as opposed to curative; however, recent treatment advancements have shown promise in achieving lasting remission.

Most reports targeting treatment-resistant FD involved the use of TNF inhibitors, including adalimumab, biosimilar adalimumab, infliximab, and certolizumab pegol. Adalimumab was the most frequently used TNF inhibitor, with 24 of 26 treated patients achieving remission. Adalimumab may have been used the most in the treatment of FD because TNF is pronounced in other neutrophilic dermatoses that have been successfully treated with TNF inhibitors. It has been reported that adalimumab needs to be continued, as stoppage or interruption led to relapse.3

Although there are few reports of the use of JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies for FD, these treatment modalities show promise, as their use led to marked improvement or lasting remission with ongoing treatment. The use of the PDE4 inhibitor apremilast displayed the most rapid improvement of any of the reviewed treatments, with remission achieved in just 3 weeks.9 The rapid success of apremilast may be attributed to the inhibitory effect on neutrophils.

Miguel-Gómez et al11 provided a therapeutic protocol for FD based on the severity of disease (N=60). The protocol included rifampicin plus clindamycin for the treatment of severe disease, as 90.5% (19/21) of resistant cases showed clinical response, with remission of 5 months’ duration. Although this may be acceptable for some patients, others may require an alternative approach. Tietze et al12 showed that rifampicin and clindamycin had the lowest success rate for long-term remission, with 8 of 10 patients relapsing within 2 to 4 months. In addition, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance remains a major concern in the treatment of FD. Upon the review of the most recent reports of successful treatment of therapy-resistant FD, biologics and small molecule inhibitors have shown remission extending through a 12-month follow-up period. We suggest considering the addition of biologics and small molecule inhibitors to the treatment protocol for severe or resistant disease.

Limitations—In the articles reviewed, the definition of remission was inconsistent among authors—some characterized it as no recurrence in lesions or pustules and some as a reduction in the inflammatory process. True duration of remission was difficult to assess from case reports, as follow-up periods varied prior to publication. The studies included in this review consisted mainly of small sample sizes owing to the rarity of FD, and consequently, strength of evidence is lacking. Inherent to the nature of systematic reviews, publication bias may have occurred. Lastly, several studies were impacted by difficulty in obtaining optimal treatment due to financial hardship, and regimens were adjusted accordingly.

Conclusion

The relapsing nature of FD leads to frustration and poor quality of life for patients. There is a paucity of data to guide treatment when FD remains recalcitrant to traditional therapy. Therapies such as TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies have shown success in the treatment of this often difficult-to-treat disease. Small sample sizes in reports discussing treatment for resistant cases as well as conflicting results make it challenging to draw conclusions about treatment efficacy. Larger studies are needed to understand the long-term outcomes of treatment options. Regardless, disease severity, patient history, patient preferences, and treatment goals can guide the selection of therapeutic options.

- Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00204.x

- Shireen F, Sudhakar A. A case of isotretinoin therapy-refractory folliculitis decalvans treated successfully with biosimilar adalimumab (Exemptia). Int J Trichology. 2018;10:240-241.

- Iorizzo M, Starace M, Vano-Galvan S, et al. Refractory folliculitis decalvans treated with adalimumab: a case series of 23 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:666-669. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.044

- Kreutzer K, Effendy I. Therapy-resistant folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris successfully treated with adalimumab. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:74-76. doi:10.1111/ddg.12224

- Alhameedy MM, Alsantali AM. Therapy-recalcitrant folliculitis decalvans controlled successfully with adalimumab. Int J Trichology. 2019;11:241-243. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_92_19

- Mihaljevic´ N, von den Driesch P. Successful use of infliximab in a patient with recalcitrant folliculitis decalvans. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:589-590. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.07972.x

- Hoy M, Böhm M. Therapy-refractory folliculitis decalvans treated with certolizumab pegol. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:e26-e28. doi:10.1111/ijd.15914

- Moussa A, Asfour L, Eisman S, et al. Successful treatment of folliculitis decalvans with baricitinib: a case series. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:279-281. doi:10.1111/ajd.13786

- Fässler M, Radonjic-Hoesli S, Feldmeyer L, et al. Successful treatment of refractory folliculitis decalvans with apremilast. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:1079-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.019

- Ismail FF, Sinclair R. Successful treatment of refractory folliculitis decalvans with secukinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:165-166. doi:10.1111/ajd.13190

- Miguel-Gómez L, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Molina-Ruiz A, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: effectiveness of therapies and prognostic factors in a multicenter series of 60 patients with long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:878-883. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1240

- Tietze JK, Heppt MV, von Preußen A, et al. Oral isotretinoin as the most effective treatment in folliculitis decalvans: a retrospective comparison of different treatment regimens in 28 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1816-1821. doi:10.1111/jdv.13052

Folliculitis decalvans (FD) is classified as a rare primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia occurring predominantly in middle-aged adults. Although the true etiology is still unknown, the pathogenesis behind the inflammatory follicular lesions stems from possible Staphylococcus aureus infection and an impaired host immune system in response to released superantigens. 1 The clinical severity of this inflammatory scalp disorder can range from mild to severe and debilitating. Multiple treatment regimens have been developed with the goal of maintaining full remission. We provide a summary of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies being utilized for patients with therapy-recalcitrant FD.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar search for the terms refractory FD, recalcitrant FD, or therapy-resistant FD to identify articles published in English from 1998 to 2022. Articles that reported recalcitrant cases and subsequent therapy with TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies were included. Articles were excluded if recalcitrant cases were not clearly defined. Remission was defined as no recurrence in lesions or pustules or as a reduction in the inflammatory process with stabilization upon continuation or discontinuation of the therapy regimen. Two reviewers (T.F. and K.U.) independently searched for and screened each report.

Results

Treatment of recalcitrant FD with biologics or small molecule inhibitors was discussed in 9 studies with a combined total of 35 patients.2-10 The treatment regimens included TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies (Table).

The TNF inhibitors were utilized in 6 reports with a combined total of 29 patients. Treatments included adalimumab or biosimilar adalimumab (27/29 patients), infliximab (1/29 patients), and certolizumab pegol (1/29 patients). Remission was reported in 26 of 29 cases. There were 2 nonresponders to adalimumab and marked improvement with certolizumab pegol without complete resolution. The use of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib in 4 patients resulted in remission. In all 4 patients, baricitinib was used with concurrent treatments, and remission was achieved in an average of 2.25 months. The use of a PDE4 inhibitor, apremilast, was reported in 1 case; remission was achieved in 3 weeks. Secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-17, was utilized in 1 patient. Marked improvement was seen after 2 months, with complete remission in 7 months.

Comment

Traditional treatment regimens for FD most often include a combination of topical and oral antibiotics; isotretinoin; and oral, topical, or intralesional corticosteroids. In the past, interventions typically were suppressive as opposed to curative; however, recent treatment advancements have shown promise in achieving lasting remission.

Most reports targeting treatment-resistant FD involved the use of TNF inhibitors, including adalimumab, biosimilar adalimumab, infliximab, and certolizumab pegol. Adalimumab was the most frequently used TNF inhibitor, with 24 of 26 treated patients achieving remission. Adalimumab may have been used the most in the treatment of FD because TNF is pronounced in other neutrophilic dermatoses that have been successfully treated with TNF inhibitors. It has been reported that adalimumab needs to be continued, as stoppage or interruption led to relapse.3

Although there are few reports of the use of JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies for FD, these treatment modalities show promise, as their use led to marked improvement or lasting remission with ongoing treatment. The use of the PDE4 inhibitor apremilast displayed the most rapid improvement of any of the reviewed treatments, with remission achieved in just 3 weeks.9 The rapid success of apremilast may be attributed to the inhibitory effect on neutrophils.

Miguel-Gómez et al11 provided a therapeutic protocol for FD based on the severity of disease (N=60). The protocol included rifampicin plus clindamycin for the treatment of severe disease, as 90.5% (19/21) of resistant cases showed clinical response, with remission of 5 months’ duration. Although this may be acceptable for some patients, others may require an alternative approach. Tietze et al12 showed that rifampicin and clindamycin had the lowest success rate for long-term remission, with 8 of 10 patients relapsing within 2 to 4 months. In addition, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance remains a major concern in the treatment of FD. Upon the review of the most recent reports of successful treatment of therapy-resistant FD, biologics and small molecule inhibitors have shown remission extending through a 12-month follow-up period. We suggest considering the addition of biologics and small molecule inhibitors to the treatment protocol for severe or resistant disease.

Limitations—In the articles reviewed, the definition of remission was inconsistent among authors—some characterized it as no recurrence in lesions or pustules and some as a reduction in the inflammatory process. True duration of remission was difficult to assess from case reports, as follow-up periods varied prior to publication. The studies included in this review consisted mainly of small sample sizes owing to the rarity of FD, and consequently, strength of evidence is lacking. Inherent to the nature of systematic reviews, publication bias may have occurred. Lastly, several studies were impacted by difficulty in obtaining optimal treatment due to financial hardship, and regimens were adjusted accordingly.

Conclusion

The relapsing nature of FD leads to frustration and poor quality of life for patients. There is a paucity of data to guide treatment when FD remains recalcitrant to traditional therapy. Therapies such as TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies have shown success in the treatment of this often difficult-to-treat disease. Small sample sizes in reports discussing treatment for resistant cases as well as conflicting results make it challenging to draw conclusions about treatment efficacy. Larger studies are needed to understand the long-term outcomes of treatment options. Regardless, disease severity, patient history, patient preferences, and treatment goals can guide the selection of therapeutic options.

Folliculitis decalvans (FD) is classified as a rare primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia occurring predominantly in middle-aged adults. Although the true etiology is still unknown, the pathogenesis behind the inflammatory follicular lesions stems from possible Staphylococcus aureus infection and an impaired host immune system in response to released superantigens. 1 The clinical severity of this inflammatory scalp disorder can range from mild to severe and debilitating. Multiple treatment regimens have been developed with the goal of maintaining full remission. We provide a summary of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies being utilized for patients with therapy-recalcitrant FD.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar search for the terms refractory FD, recalcitrant FD, or therapy-resistant FD to identify articles published in English from 1998 to 2022. Articles that reported recalcitrant cases and subsequent therapy with TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies were included. Articles were excluded if recalcitrant cases were not clearly defined. Remission was defined as no recurrence in lesions or pustules or as a reduction in the inflammatory process with stabilization upon continuation or discontinuation of the therapy regimen. Two reviewers (T.F. and K.U.) independently searched for and screened each report.

Results

Treatment of recalcitrant FD with biologics or small molecule inhibitors was discussed in 9 studies with a combined total of 35 patients.2-10 The treatment regimens included TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies (Table).

The TNF inhibitors were utilized in 6 reports with a combined total of 29 patients. Treatments included adalimumab or biosimilar adalimumab (27/29 patients), infliximab (1/29 patients), and certolizumab pegol (1/29 patients). Remission was reported in 26 of 29 cases. There were 2 nonresponders to adalimumab and marked improvement with certolizumab pegol without complete resolution. The use of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib in 4 patients resulted in remission. In all 4 patients, baricitinib was used with concurrent treatments, and remission was achieved in an average of 2.25 months. The use of a PDE4 inhibitor, apremilast, was reported in 1 case; remission was achieved in 3 weeks. Secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-17, was utilized in 1 patient. Marked improvement was seen after 2 months, with complete remission in 7 months.

Comment

Traditional treatment regimens for FD most often include a combination of topical and oral antibiotics; isotretinoin; and oral, topical, or intralesional corticosteroids. In the past, interventions typically were suppressive as opposed to curative; however, recent treatment advancements have shown promise in achieving lasting remission.

Most reports targeting treatment-resistant FD involved the use of TNF inhibitors, including adalimumab, biosimilar adalimumab, infliximab, and certolizumab pegol. Adalimumab was the most frequently used TNF inhibitor, with 24 of 26 treated patients achieving remission. Adalimumab may have been used the most in the treatment of FD because TNF is pronounced in other neutrophilic dermatoses that have been successfully treated with TNF inhibitors. It has been reported that adalimumab needs to be continued, as stoppage or interruption led to relapse.3

Although there are few reports of the use of JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies for FD, these treatment modalities show promise, as their use led to marked improvement or lasting remission with ongoing treatment. The use of the PDE4 inhibitor apremilast displayed the most rapid improvement of any of the reviewed treatments, with remission achieved in just 3 weeks.9 The rapid success of apremilast may be attributed to the inhibitory effect on neutrophils.

Miguel-Gómez et al11 provided a therapeutic protocol for FD based on the severity of disease (N=60). The protocol included rifampicin plus clindamycin for the treatment of severe disease, as 90.5% (19/21) of resistant cases showed clinical response, with remission of 5 months’ duration. Although this may be acceptable for some patients, others may require an alternative approach. Tietze et al12 showed that rifampicin and clindamycin had the lowest success rate for long-term remission, with 8 of 10 patients relapsing within 2 to 4 months. In addition, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance remains a major concern in the treatment of FD. Upon the review of the most recent reports of successful treatment of therapy-resistant FD, biologics and small molecule inhibitors have shown remission extending through a 12-month follow-up period. We suggest considering the addition of biologics and small molecule inhibitors to the treatment protocol for severe or resistant disease.

Limitations—In the articles reviewed, the definition of remission was inconsistent among authors—some characterized it as no recurrence in lesions or pustules and some as a reduction in the inflammatory process. True duration of remission was difficult to assess from case reports, as follow-up periods varied prior to publication. The studies included in this review consisted mainly of small sample sizes owing to the rarity of FD, and consequently, strength of evidence is lacking. Inherent to the nature of systematic reviews, publication bias may have occurred. Lastly, several studies were impacted by difficulty in obtaining optimal treatment due to financial hardship, and regimens were adjusted accordingly.

Conclusion

The relapsing nature of FD leads to frustration and poor quality of life for patients. There is a paucity of data to guide treatment when FD remains recalcitrant to traditional therapy. Therapies such as TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies have shown success in the treatment of this often difficult-to-treat disease. Small sample sizes in reports discussing treatment for resistant cases as well as conflicting results make it challenging to draw conclusions about treatment efficacy. Larger studies are needed to understand the long-term outcomes of treatment options. Regardless, disease severity, patient history, patient preferences, and treatment goals can guide the selection of therapeutic options.

- Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00204.x

- Shireen F, Sudhakar A. A case of isotretinoin therapy-refractory folliculitis decalvans treated successfully with biosimilar adalimumab (Exemptia). Int J Trichology. 2018;10:240-241.

- Iorizzo M, Starace M, Vano-Galvan S, et al. Refractory folliculitis decalvans treated with adalimumab: a case series of 23 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:666-669. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.044

- Kreutzer K, Effendy I. Therapy-resistant folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris successfully treated with adalimumab. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:74-76. doi:10.1111/ddg.12224

- Alhameedy MM, Alsantali AM. Therapy-recalcitrant folliculitis decalvans controlled successfully with adalimumab. Int J Trichology. 2019;11:241-243. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_92_19

- Mihaljevic´ N, von den Driesch P. Successful use of infliximab in a patient with recalcitrant folliculitis decalvans. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:589-590. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.07972.x

- Hoy M, Böhm M. Therapy-refractory folliculitis decalvans treated with certolizumab pegol. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:e26-e28. doi:10.1111/ijd.15914

- Moussa A, Asfour L, Eisman S, et al. Successful treatment of folliculitis decalvans with baricitinib: a case series. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:279-281. doi:10.1111/ajd.13786

- Fässler M, Radonjic-Hoesli S, Feldmeyer L, et al. Successful treatment of refractory folliculitis decalvans with apremilast. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:1079-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.019

- Ismail FF, Sinclair R. Successful treatment of refractory folliculitis decalvans with secukinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:165-166. doi:10.1111/ajd.13190

- Miguel-Gómez L, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Molina-Ruiz A, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: effectiveness of therapies and prognostic factors in a multicenter series of 60 patients with long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:878-883. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1240

- Tietze JK, Heppt MV, von Preußen A, et al. Oral isotretinoin as the most effective treatment in folliculitis decalvans: a retrospective comparison of different treatment regimens in 28 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1816-1821. doi:10.1111/jdv.13052

- Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00204.x

- Shireen F, Sudhakar A. A case of isotretinoin therapy-refractory folliculitis decalvans treated successfully with biosimilar adalimumab (Exemptia). Int J Trichology. 2018;10:240-241.

- Iorizzo M, Starace M, Vano-Galvan S, et al. Refractory folliculitis decalvans treated with adalimumab: a case series of 23 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:666-669. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.044

- Kreutzer K, Effendy I. Therapy-resistant folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris successfully treated with adalimumab. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:74-76. doi:10.1111/ddg.12224

- Alhameedy MM, Alsantali AM. Therapy-recalcitrant folliculitis decalvans controlled successfully with adalimumab. Int J Trichology. 2019;11:241-243. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_92_19

- Mihaljevic´ N, von den Driesch P. Successful use of infliximab in a patient with recalcitrant folliculitis decalvans. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:589-590. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.07972.x

- Hoy M, Böhm M. Therapy-refractory folliculitis decalvans treated with certolizumab pegol. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:e26-e28. doi:10.1111/ijd.15914

- Moussa A, Asfour L, Eisman S, et al. Successful treatment of folliculitis decalvans with baricitinib: a case series. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:279-281. doi:10.1111/ajd.13786

- Fässler M, Radonjic-Hoesli S, Feldmeyer L, et al. Successful treatment of refractory folliculitis decalvans with apremilast. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:1079-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.019

- Ismail FF, Sinclair R. Successful treatment of refractory folliculitis decalvans with secukinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:165-166. doi:10.1111/ajd.13190

- Miguel-Gómez L, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Molina-Ruiz A, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: effectiveness of therapies and prognostic factors in a multicenter series of 60 patients with long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:878-883. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1240

- Tietze JK, Heppt MV, von Preußen A, et al. Oral isotretinoin as the most effective treatment in folliculitis decalvans: a retrospective comparison of different treatment regimens in 28 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1816-1821. doi:10.1111/jdv.13052

Practice Points

- Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, Janus kinase inhibitors, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies have shown success in the treatment of folliculitis decalvans resistant to traditional therapies.

- The true etiology of folliculitis decalvans is still unknown, but possible factors include Staphylococcus aureus infection and an impaired host immune system, which may benefit from treatment with biologics and small molecule inhibitors.

PCOS: Laser, Light Therapy Helpful for Hirsutism

BY DEEPA VARMA

TOPLINE:

, according to the results of a systematic review.

METHODOLOGY:

- Hirsutism, which affects 70%-80% of women with PCOS, is frequently marginalized as a cosmetic issue by healthcare providers, despite its significant psychological repercussions, including diminished self-esteem, reduced quality of life, and heightened depression.

- The 2023 international evidence-based PCOS guideline considers managing hirsutism a priority in women with PCOS.

- Researchers reviewed six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two cohort studies), which included 423 patients with PCOS who underwent laser or light-based hair reduction therapies, published through 2022.

- The studies evaluated the alexandrite laser, diode laser, and intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy, with and without pharmacological treatments. The main outcomes were hirsutism severity, psychological outcome, and adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alexandrite laser (wavelength, 755 nm) showed effective hair reduction and improved patient satisfaction (one study); high-fluence treatment yielded better outcomes than low-fluence treatment (one study). Alexandrite laser 755 nm also showed longer hair-free intervals and greater hair reduction than IPL therapy at 650-1000 nm (one study).

- Combined IPL (600 nm) and metformin therapy improved hirsutism and hair count reduction compared with IPL alone, but with more side effects (one study).

- Diode laser treatments (810 nm) with combined oral contraceptives improved hirsutism and related quality of life measures compared with diode laser alone or with metformin (one study).

- Comparing two diode lasers (wavelengths, 810 nm), low-fluence, high repetition laser showed superior hair width reduction and lower pain scores than high fluence, low-repetition laser (one study).

IN PRACTICE:

Laser and light treatments alone or combined with other treatments have demonstrated “encouraging results in reducing hirsutism severity, enhancing psychological well-being, and improving overall quality of life for affected individuals,” the authors wrote, noting that additional high-quality trials evaluating these treatments, which include more patients with different skin tones, are needed.

SOURCE:

The first author of the review is Katrina Tan, MD, Monash Health, Department of Dermatology, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and it was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include low certainty of evidence because of the observational nature of some of the studies, the small number of studies, and underrepresentation of darker skin types, limiting generalizability.

DISCLOSURES:

The review is part of an update to the PCOS guideline, which was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council through various organizations. Several authors reported receiving grants and personal fees outside this work. Dr. Tan was a member of the 2023 PCOS guideline evidence team. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BY DEEPA VARMA

TOPLINE:

, according to the results of a systematic review.

METHODOLOGY:

- Hirsutism, which affects 70%-80% of women with PCOS, is frequently marginalized as a cosmetic issue by healthcare providers, despite its significant psychological repercussions, including diminished self-esteem, reduced quality of life, and heightened depression.

- The 2023 international evidence-based PCOS guideline considers managing hirsutism a priority in women with PCOS.

- Researchers reviewed six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two cohort studies), which included 423 patients with PCOS who underwent laser or light-based hair reduction therapies, published through 2022.

- The studies evaluated the alexandrite laser, diode laser, and intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy, with and without pharmacological treatments. The main outcomes were hirsutism severity, psychological outcome, and adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alexandrite laser (wavelength, 755 nm) showed effective hair reduction and improved patient satisfaction (one study); high-fluence treatment yielded better outcomes than low-fluence treatment (one study). Alexandrite laser 755 nm also showed longer hair-free intervals and greater hair reduction than IPL therapy at 650-1000 nm (one study).

- Combined IPL (600 nm) and metformin therapy improved hirsutism and hair count reduction compared with IPL alone, but with more side effects (one study).

- Diode laser treatments (810 nm) with combined oral contraceptives improved hirsutism and related quality of life measures compared with diode laser alone or with metformin (one study).

- Comparing two diode lasers (wavelengths, 810 nm), low-fluence, high repetition laser showed superior hair width reduction and lower pain scores than high fluence, low-repetition laser (one study).

IN PRACTICE:

Laser and light treatments alone or combined with other treatments have demonstrated “encouraging results in reducing hirsutism severity, enhancing psychological well-being, and improving overall quality of life for affected individuals,” the authors wrote, noting that additional high-quality trials evaluating these treatments, which include more patients with different skin tones, are needed.

SOURCE:

The first author of the review is Katrina Tan, MD, Monash Health, Department of Dermatology, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and it was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include low certainty of evidence because of the observational nature of some of the studies, the small number of studies, and underrepresentation of darker skin types, limiting generalizability.

DISCLOSURES:

The review is part of an update to the PCOS guideline, which was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council through various organizations. Several authors reported receiving grants and personal fees outside this work. Dr. Tan was a member of the 2023 PCOS guideline evidence team. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BY DEEPA VARMA

TOPLINE:

, according to the results of a systematic review.

METHODOLOGY:

- Hirsutism, which affects 70%-80% of women with PCOS, is frequently marginalized as a cosmetic issue by healthcare providers, despite its significant psychological repercussions, including diminished self-esteem, reduced quality of life, and heightened depression.

- The 2023 international evidence-based PCOS guideline considers managing hirsutism a priority in women with PCOS.

- Researchers reviewed six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two cohort studies), which included 423 patients with PCOS who underwent laser or light-based hair reduction therapies, published through 2022.

- The studies evaluated the alexandrite laser, diode laser, and intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy, with and without pharmacological treatments. The main outcomes were hirsutism severity, psychological outcome, and adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alexandrite laser (wavelength, 755 nm) showed effective hair reduction and improved patient satisfaction (one study); high-fluence treatment yielded better outcomes than low-fluence treatment (one study). Alexandrite laser 755 nm also showed longer hair-free intervals and greater hair reduction than IPL therapy at 650-1000 nm (one study).

- Combined IPL (600 nm) and metformin therapy improved hirsutism and hair count reduction compared with IPL alone, but with more side effects (one study).

- Diode laser treatments (810 nm) with combined oral contraceptives improved hirsutism and related quality of life measures compared with diode laser alone or with metformin (one study).

- Comparing two diode lasers (wavelengths, 810 nm), low-fluence, high repetition laser showed superior hair width reduction and lower pain scores than high fluence, low-repetition laser (one study).

IN PRACTICE:

Laser and light treatments alone or combined with other treatments have demonstrated “encouraging results in reducing hirsutism severity, enhancing psychological well-being, and improving overall quality of life for affected individuals,” the authors wrote, noting that additional high-quality trials evaluating these treatments, which include more patients with different skin tones, are needed.

SOURCE:

The first author of the review is Katrina Tan, MD, Monash Health, Department of Dermatology, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and it was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include low certainty of evidence because of the observational nature of some of the studies, the small number of studies, and underrepresentation of darker skin types, limiting generalizability.

DISCLOSURES:

The review is part of an update to the PCOS guideline, which was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council through various organizations. Several authors reported receiving grants and personal fees outside this work. Dr. Tan was a member of the 2023 PCOS guideline evidence team. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Consensus Statement Aims to Guide Use of Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil for Hair Loss

SAN DIEGO — .

Those are among the key recommendations that resulted from a modified eDelphi consensus of experts who convened to develop guidelines for LDOM prescribing and monitoring.

“Topical minoxidil is safe, effective, over-the-counter, and FDA-approved to treat the most common form of hair loss, androgenetic alopecia,” one of the study authors, Jennifer Fu, MD, a dermatologist who directs the Hair Disorders Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The results of the expert consensus were presented during a poster session at the meeting. “It is often used off label for other types of hair loss, yet clinicians who treat hair loss know that patient compliance with topical minoxidil can be poor for a variety of reasons,” she said. “Patients report that it can be difficult to apply and complicate hair styling. For many patients, topical minoxidil can be drying or cause irritant or allergic contact reactions.”

LDOM has become a popular alternative for patients for whom topical minoxidil is logistically challenging, irritating, or ineffective, she continued. Although oral minoxidil is no longer a first-line antihypertensive agent given the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects at higher antihypertensive dosing (10-40 mg daily), a growing number of small studies have documented the use of LDOM at doses ranging from 0.25 mg to 5 mg daily as a safe, effective option for various types of hair loss.

“Given the current absence of larger trials on this topic, our research group identified a need for expert-based guidelines for prescribing and monitoring LDOM use in hair loss patients,” Dr. Fu said. “Our goal was to provide clinicians who treat hair loss patients a road map for using LDOM effectively, maximizing hair growth, and minimizing potential cardiovascular adverse effects.”

Arriving at a Consensus

The process involved 43 hair loss specialists from 12 countries with an average of 6.29 years of experience with LDOM for hair loss, who participated in a multi-round modified Delphi process. They considered questions that addressed LDOM safety, efficacy, dosing, and monitoring for hair loss, and consensus was reached if at least 70% of participants indicated “agree” or “strongly agree” on a five-point Likert scale. Round 1 consisted of 180 open-ended, multiple-choice, or Likert-scale questions, while round 2 involved 121 Likert-scale questions, round 3 consisted of 16 Likert-scale questions, and round 4 included 11 Likert-scale questions. In all, 94 items achieved Likert-scale consensus.

Specifically, experts on the panel found a direct benefit of LDOM for androgenetic alopecia, age-related patterned thinning, alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, traction alopecia, persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, and endocrine therapy-induced alopecia. They found a supportive benefit of LDOM for lichen planopilaris, frontal fibrosing alopecia, central centrifugal alopecia, and fibrosing alopecia in a patterned distribution.

“LDOM can be considered when topical minoxidil is more expensive, logistically challenging, has plateaued in efficacy, results in undesirable product residue/skin irritation,” or exacerbates inflammatory processes (ie eczema, psoriasis), they added.

Contraindications to LDOM listed in the consensus recommendations include hypersensitivity to minoxidil, significant drug-drug interactions with LDOM, a history of pericardial effusion/tamponade, pericarditis, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension associated with mitral stenosis, pheochromocytoma, and pregnancy/breastfeeding. Cited precautions of LDOM use include a history of tachycardia or arrhythmia, hypotension, renal impairment, and being on dialysis.

Dr. Fu and colleagues noted that the earliest time point at which LDOM should be expected to demonstrate efficacy is 3-6 months. “Baseline testing is not routine but may be considered in case of identified precautions,” they wrote. They also noted that LDOM can possibly be co-administered with beta-blockers with a specialty consultation, and with spironolactone in biologic female or transgender female patients with hirsutism, acne, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and with lower extremity and facial edema.

According to the consensus statement, the most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adult females aged 18 years and older includes a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range between 0.625 mg and 5 mg daily. For adult males, the most frequently prescribed dosing regimen is a starting dose of 2.5 daily, with a dosing range between 1.25 mg and 5 mg daily. The most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adolescent females aged 12-17 years is a starting dose of 0.625 mg daily, with a dosing range of 0.625 to 2.5 mg daily. For adolescent males, the recommended regimen is a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range of 1.25 mg to 5 mg daily.

“We hope that this consensus statement will guide our colleagues who would like to use LDOM to treat hair loss in their adult and adolescent patients,” Dr. Fu told this news organization. “These recommendations may be used to inform clinical practice until additional evidence-based data becomes available.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the effort, including the fact that the expert panel was underrepresented in treating hair loss in pediatric patients, “and therefore failed to reach consensus on LDOM pediatric use and dosing,” she said. “We encourage our pediatric dermatology colleagues to further research LDOM in pediatric patients.”

In an interview, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical dermatology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was asked to comment, but was not involved with the work, characterized the consensus as a “helpful, concise reference guide for dermatologists.”

The advantages of the study are the standardized methods used, “and the experience of the panel,” she said. “Study limitations include the response rate, which was less than 60%, and the risk of potential side effects are not stratified by age, sex, or comorbidities,” she added.

Dr. Fu disclosed that she is a consultant to Pfizer. Dr. Lipner reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO — .

Those are among the key recommendations that resulted from a modified eDelphi consensus of experts who convened to develop guidelines for LDOM prescribing and monitoring.

“Topical minoxidil is safe, effective, over-the-counter, and FDA-approved to treat the most common form of hair loss, androgenetic alopecia,” one of the study authors, Jennifer Fu, MD, a dermatologist who directs the Hair Disorders Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The results of the expert consensus were presented during a poster session at the meeting. “It is often used off label for other types of hair loss, yet clinicians who treat hair loss know that patient compliance with topical minoxidil can be poor for a variety of reasons,” she said. “Patients report that it can be difficult to apply and complicate hair styling. For many patients, topical minoxidil can be drying or cause irritant or allergic contact reactions.”