User login

Frozen noninferior to fresh fecal microbiota transplantation

Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to that using fresh material for treating recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA.

Using frozen rather than fresh fecal material offers many advantages, such as allowing much more widespread and immediate accessibility of the treatment; reducing the number and frequency of donor screenings, which in turn would reduce costs; and ameliorating concern about potential transmission of pathogens from the donor to the recipient, since samples could be stored in quarantine until screening results are known, said Dr. Christine H. Lee of the department of pathology and molecular medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton (Ont.), and her associates.

They performed a 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial at six academic medical centers in Canada to compare frozen with fresh donor material in 232 adults with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection. These study participants had “an extensive burden of comorbidity”: most had inflammatory bowel diseases and approximately 85% were immunocompromised, having undergone chronic hemodialysis or kidney transplantation, or having had metastatic solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. Half of the study subjects were inpatients, and approximately 75% were aged 65 years and older.

The patients were assigned to receive 50 mL of frozen-then-thawed FMT (114 participants) or fresh FMT (118 participants) by retention enema, delivered using 60-mL syringes. Those who didn’t improve by day 4 were given an additional FMT from the same donor. “Administration by enema is significantly less invasive than colonoscopy or nasojejunal/gastric administration and can be performed outside an acute care facility,” Dr. Lee and her associates noted.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical resolution, defined as no recurrence of C. difficile–related diarrhea at 13 weeks and no need for antibiotics. In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved this endpoint. In the intention-to-treat population, 75.0% of the frozen FMT group and 70.3% of the fresh FMT group achieved it. Both results demonstrate the noninferiority of frozen FMT, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:142-9. doi:10.1001/jama.201518098).

The proportion of adverse events and severe adverse events was deemed low and did not differ between the two study groups. The most common adverse events that may possibly have been related to treatment occurred in similar numbers of each group and included transient diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea during the first 24 hours after transplantation and constipation and excess flatulence during the 13-week follow-up.

Even though this follow-up was longer than that in most clinical trials of FMT for C. difficile infection, which only tracked patients for 40 days, it is still insufficient to assess the long-term safety of the treatment. Ten-year follow-up of the participants in this trial is currently under way to examine any beneficial effects the treatment might exert on the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or autoimmune disease, as well as any negative effects such as the development of autoimmune disorders or cancer.

The findings of Dr. Lee and her associates offer the best evidence to date supporting the use of frozen stool material in FMT, which would eliminate many of the logistical burdens associated with the treatment. For example, stool collection and processing would no longer have to be tied to the date and time of each individual transplantation.

These results also support the use of centralized stool banks, which would offer clinicians access to safe, screened stool material that could be shipped and stored frozen, then thawed for use as needed.

Dr. Preeti N. Malani and Dr. Krishna Rao are with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. Dr. Malani is also an associate editor at JAMA and Dr. Rao is also with the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Dr. Rao’s work is supported in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. Dr. Malani and Dr. Rao reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:137-8) accompanying Dr. Lee’s report.

The findings of Dr. Lee and her associates offer the best evidence to date supporting the use of frozen stool material in FMT, which would eliminate many of the logistical burdens associated with the treatment. For example, stool collection and processing would no longer have to be tied to the date and time of each individual transplantation.

These results also support the use of centralized stool banks, which would offer clinicians access to safe, screened stool material that could be shipped and stored frozen, then thawed for use as needed.

Dr. Preeti N. Malani and Dr. Krishna Rao are with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. Dr. Malani is also an associate editor at JAMA and Dr. Rao is also with the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Dr. Rao’s work is supported in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. Dr. Malani and Dr. Rao reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:137-8) accompanying Dr. Lee’s report.

The findings of Dr. Lee and her associates offer the best evidence to date supporting the use of frozen stool material in FMT, which would eliminate many of the logistical burdens associated with the treatment. For example, stool collection and processing would no longer have to be tied to the date and time of each individual transplantation.

These results also support the use of centralized stool banks, which would offer clinicians access to safe, screened stool material that could be shipped and stored frozen, then thawed for use as needed.

Dr. Preeti N. Malani and Dr. Krishna Rao are with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. Dr. Malani is also an associate editor at JAMA and Dr. Rao is also with the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Dr. Rao’s work is supported in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. Dr. Malani and Dr. Rao reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:137-8) accompanying Dr. Lee’s report.

Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to that using fresh material for treating recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA.

Using frozen rather than fresh fecal material offers many advantages, such as allowing much more widespread and immediate accessibility of the treatment; reducing the number and frequency of donor screenings, which in turn would reduce costs; and ameliorating concern about potential transmission of pathogens from the donor to the recipient, since samples could be stored in quarantine until screening results are known, said Dr. Christine H. Lee of the department of pathology and molecular medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton (Ont.), and her associates.

They performed a 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial at six academic medical centers in Canada to compare frozen with fresh donor material in 232 adults with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection. These study participants had “an extensive burden of comorbidity”: most had inflammatory bowel diseases and approximately 85% were immunocompromised, having undergone chronic hemodialysis or kidney transplantation, or having had metastatic solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. Half of the study subjects were inpatients, and approximately 75% were aged 65 years and older.

The patients were assigned to receive 50 mL of frozen-then-thawed FMT (114 participants) or fresh FMT (118 participants) by retention enema, delivered using 60-mL syringes. Those who didn’t improve by day 4 were given an additional FMT from the same donor. “Administration by enema is significantly less invasive than colonoscopy or nasojejunal/gastric administration and can be performed outside an acute care facility,” Dr. Lee and her associates noted.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical resolution, defined as no recurrence of C. difficile–related diarrhea at 13 weeks and no need for antibiotics. In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved this endpoint. In the intention-to-treat population, 75.0% of the frozen FMT group and 70.3% of the fresh FMT group achieved it. Both results demonstrate the noninferiority of frozen FMT, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:142-9. doi:10.1001/jama.201518098).

The proportion of adverse events and severe adverse events was deemed low and did not differ between the two study groups. The most common adverse events that may possibly have been related to treatment occurred in similar numbers of each group and included transient diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea during the first 24 hours after transplantation and constipation and excess flatulence during the 13-week follow-up.

Even though this follow-up was longer than that in most clinical trials of FMT for C. difficile infection, which only tracked patients for 40 days, it is still insufficient to assess the long-term safety of the treatment. Ten-year follow-up of the participants in this trial is currently under way to examine any beneficial effects the treatment might exert on the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or autoimmune disease, as well as any negative effects such as the development of autoimmune disorders or cancer.

Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to that using fresh material for treating recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA.

Using frozen rather than fresh fecal material offers many advantages, such as allowing much more widespread and immediate accessibility of the treatment; reducing the number and frequency of donor screenings, which in turn would reduce costs; and ameliorating concern about potential transmission of pathogens from the donor to the recipient, since samples could be stored in quarantine until screening results are known, said Dr. Christine H. Lee of the department of pathology and molecular medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton (Ont.), and her associates.

They performed a 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial at six academic medical centers in Canada to compare frozen with fresh donor material in 232 adults with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection. These study participants had “an extensive burden of comorbidity”: most had inflammatory bowel diseases and approximately 85% were immunocompromised, having undergone chronic hemodialysis or kidney transplantation, or having had metastatic solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. Half of the study subjects were inpatients, and approximately 75% were aged 65 years and older.

The patients were assigned to receive 50 mL of frozen-then-thawed FMT (114 participants) or fresh FMT (118 participants) by retention enema, delivered using 60-mL syringes. Those who didn’t improve by day 4 were given an additional FMT from the same donor. “Administration by enema is significantly less invasive than colonoscopy or nasojejunal/gastric administration and can be performed outside an acute care facility,” Dr. Lee and her associates noted.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical resolution, defined as no recurrence of C. difficile–related diarrhea at 13 weeks and no need for antibiotics. In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved this endpoint. In the intention-to-treat population, 75.0% of the frozen FMT group and 70.3% of the fresh FMT group achieved it. Both results demonstrate the noninferiority of frozen FMT, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:142-9. doi:10.1001/jama.201518098).

The proportion of adverse events and severe adverse events was deemed low and did not differ between the two study groups. The most common adverse events that may possibly have been related to treatment occurred in similar numbers of each group and included transient diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea during the first 24 hours after transplantation and constipation and excess flatulence during the 13-week follow-up.

Even though this follow-up was longer than that in most clinical trials of FMT for C. difficile infection, which only tracked patients for 40 days, it is still insufficient to assess the long-term safety of the treatment. Ten-year follow-up of the participants in this trial is currently under way to examine any beneficial effects the treatment might exert on the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or autoimmune disease, as well as any negative effects such as the development of autoimmune disorders or cancer.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to using fresh material for recurrent/refractory Clostridium difficile infection.

Major finding: In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved clinical resolution.

Data source: A 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial involving 232 patients treated at six academic medical centers in Canada and followed for 13 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Physicians Services Inc., the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council, the National Science Foundation, and the gastrointestinal diseases research unit at Kingston (Ont.) General Hospital. Dr. Lee reported participating in clinical trials for ViroPharma, Actelion, Cubist, and Merck, and serving on the advisory boards of Rebiotix and Merck. Her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Future IBD treatments out of sync with patient needs, expert says

ORLANDO – A range of novel therapies are set to come online for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but they will miss the mark when it comes to meeting the need for better, longer-lasting outcomes, according to one expert.

“We’re positioning our therapies all wrong,” Dr. Stephen Hanauer said at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

“In psoriasis, patients are immediately given effective treatment with ustekinumab, but in IBD, we have to wait for patients to fail multiple therapies before they are given an effective one,” said Dr. Hanauer, who is the Clifford Joseph Barborka Professor of Medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. The result, he said, is that after first-line therapies in IBD have been used to diminishing effect, patients typically have waited up to between 6 and 10 years before they are given the treatment that works best for them. By then, when a patient likely has experienced penetrating disease and fistulas, even the most effective therapy has less than a 50% chance of working well.

This upside down state of affairs in the field is due to a combination of factors. Since the 1998 introduction to the U.S. market of infliximab for treating Crohn’s disease, much has been learned about the characteristics of IBD, including that it is a chronic, progressive condition with a higher burden of inflammation than is necessarily indicated by clinical symptoms.

But at the time infliximab was introduced, it was viewed not as a first-line treatment that could prevent further disease, but as a last ditch effort to halt an already rampant disease state that typically had its roots of destruction well planted long before the patient presented clinically, according to Dr. Hanauer.

In the last 2 decades, however, numerous studies have shown that earlier intervention with biologics results in higher treatment response rates and less structural trauma. []

In addition, data indicate that administering the correct choice of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent in biologic-naive patients will yield as much as a 20% greater response rate, which could lead to lower costs. “Long-term pharmacoeconomic data are needed to include not only direct costs of care, but also indirect costs that capture lost income, productivity, [and] disability,” Dr. Hanauer said in an interview.

As it stands now, even vedolizumab, indicated in 2014 for use in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is kept for an even later stage of disease in the standard algorithm, coming behind not only “severe stage of disease” but placed after a patient has failed other anti-TNF treatment.

Biologics are far safer than the corticosteroids, which precede them in the typical treatment algorithm, but because cost is king, according Dr. Hanauer, “it’s the cost that drives our later-stage intervention … if anti-TNFs cost a dollar, we’d use them in everything.”

“We would see more impact if we move these therapies earlier into treatment,” he said. “Now we give the patients least likely to respond to these treatments, the [costliest] therapies,” Dr. Hanauer said during his presentation.

Meanwhile, the several novel IBD therapies in development are primarily being tested for late-stage disease. Changing the criteria for inclusion in such clinical trials could mean future treatment is more cost effective. “Study sponsors could go after ‘earlier’ indications in the mild to moderate range,” he said in the interview.

To improve the treatment algorithms already in use, Dr. Hanauer said clinicians should learn more about the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of their armamentarium, something he said most clinical trials tend to ignore. “Most [IBD] drugs were developed for rheumatoid arthritis where these kinds of considerations are not as important since they have many more ‘tools’ [to choose from] in rheumatology. In IBD, we have had to make the best of our limited tools. Industry would prefer to keep things simple, but it isn’t.”

Also availing themselves of therapeutic drug monitoring would help clinicians ensure that patients have high enough blood levels of their treatment at the time they complete induction therapy, making the management phase easier, Dr. Hanauer said.

Redefining disease severity will mean that new treatments will have more efficacy, and can lead to more opportunities for novel treatments to work. Until then, leaving biologics to be the agent of last resort means, according to Dr. Hanauer, there are more patients “who have none of the benefit and all of the risk.”

Dr. Hanauer reported several relevant financial disclosures, including AbbVie, Actavis, Hospira, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer.

Potential new inflammatory bowel disease treatments

Adhesion molecule–based therapies

• PF-00547659 (Pfizer), an anti-MAdCam S1P1 agonist; an oral agent; for ulcerative colitis

• Ozanimod (Celgene); for ulcerative colitis; now in phase III

• Etrolizumab (Hoffmann-La Roche); for Crohn’s disease; now in phase III

Biologics for IL-12/23 pathways

MEDI2070 (MedImmune/Amgen), an anti-p19 antibody; targets IL-23 for Crohn’s disease

Agents for the JAK-STAT pathway

• Mongersen (Celgene), an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide; for Crohn’s disease; in phase III

• Tofacitinib (Pfizer)

Sources: Dr. Brian Feagan, University of Western Ontario; Dr. Bruce Sands, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Dr. Bill Sandborn, University of California, San Diego

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – A range of novel therapies are set to come online for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but they will miss the mark when it comes to meeting the need for better, longer-lasting outcomes, according to one expert.

“We’re positioning our therapies all wrong,” Dr. Stephen Hanauer said at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

“In psoriasis, patients are immediately given effective treatment with ustekinumab, but in IBD, we have to wait for patients to fail multiple therapies before they are given an effective one,” said Dr. Hanauer, who is the Clifford Joseph Barborka Professor of Medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. The result, he said, is that after first-line therapies in IBD have been used to diminishing effect, patients typically have waited up to between 6 and 10 years before they are given the treatment that works best for them. By then, when a patient likely has experienced penetrating disease and fistulas, even the most effective therapy has less than a 50% chance of working well.

This upside down state of affairs in the field is due to a combination of factors. Since the 1998 introduction to the U.S. market of infliximab for treating Crohn’s disease, much has been learned about the characteristics of IBD, including that it is a chronic, progressive condition with a higher burden of inflammation than is necessarily indicated by clinical symptoms.

But at the time infliximab was introduced, it was viewed not as a first-line treatment that could prevent further disease, but as a last ditch effort to halt an already rampant disease state that typically had its roots of destruction well planted long before the patient presented clinically, according to Dr. Hanauer.

In the last 2 decades, however, numerous studies have shown that earlier intervention with biologics results in higher treatment response rates and less structural trauma. []

In addition, data indicate that administering the correct choice of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent in biologic-naive patients will yield as much as a 20% greater response rate, which could lead to lower costs. “Long-term pharmacoeconomic data are needed to include not only direct costs of care, but also indirect costs that capture lost income, productivity, [and] disability,” Dr. Hanauer said in an interview.

As it stands now, even vedolizumab, indicated in 2014 for use in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is kept for an even later stage of disease in the standard algorithm, coming behind not only “severe stage of disease” but placed after a patient has failed other anti-TNF treatment.

Biologics are far safer than the corticosteroids, which precede them in the typical treatment algorithm, but because cost is king, according Dr. Hanauer, “it’s the cost that drives our later-stage intervention … if anti-TNFs cost a dollar, we’d use them in everything.”

“We would see more impact if we move these therapies earlier into treatment,” he said. “Now we give the patients least likely to respond to these treatments, the [costliest] therapies,” Dr. Hanauer said during his presentation.

Meanwhile, the several novel IBD therapies in development are primarily being tested for late-stage disease. Changing the criteria for inclusion in such clinical trials could mean future treatment is more cost effective. “Study sponsors could go after ‘earlier’ indications in the mild to moderate range,” he said in the interview.

To improve the treatment algorithms already in use, Dr. Hanauer said clinicians should learn more about the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of their armamentarium, something he said most clinical trials tend to ignore. “Most [IBD] drugs were developed for rheumatoid arthritis where these kinds of considerations are not as important since they have many more ‘tools’ [to choose from] in rheumatology. In IBD, we have had to make the best of our limited tools. Industry would prefer to keep things simple, but it isn’t.”

Also availing themselves of therapeutic drug monitoring would help clinicians ensure that patients have high enough blood levels of their treatment at the time they complete induction therapy, making the management phase easier, Dr. Hanauer said.

Redefining disease severity will mean that new treatments will have more efficacy, and can lead to more opportunities for novel treatments to work. Until then, leaving biologics to be the agent of last resort means, according to Dr. Hanauer, there are more patients “who have none of the benefit and all of the risk.”

Dr. Hanauer reported several relevant financial disclosures, including AbbVie, Actavis, Hospira, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer.

Potential new inflammatory bowel disease treatments

Adhesion molecule–based therapies

• PF-00547659 (Pfizer), an anti-MAdCam S1P1 agonist; an oral agent; for ulcerative colitis

• Ozanimod (Celgene); for ulcerative colitis; now in phase III

• Etrolizumab (Hoffmann-La Roche); for Crohn’s disease; now in phase III

Biologics for IL-12/23 pathways

MEDI2070 (MedImmune/Amgen), an anti-p19 antibody; targets IL-23 for Crohn’s disease

Agents for the JAK-STAT pathway

• Mongersen (Celgene), an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide; for Crohn’s disease; in phase III

• Tofacitinib (Pfizer)

Sources: Dr. Brian Feagan, University of Western Ontario; Dr. Bruce Sands, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Dr. Bill Sandborn, University of California, San Diego

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – A range of novel therapies are set to come online for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but they will miss the mark when it comes to meeting the need for better, longer-lasting outcomes, according to one expert.

“We’re positioning our therapies all wrong,” Dr. Stephen Hanauer said at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

“In psoriasis, patients are immediately given effective treatment with ustekinumab, but in IBD, we have to wait for patients to fail multiple therapies before they are given an effective one,” said Dr. Hanauer, who is the Clifford Joseph Barborka Professor of Medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. The result, he said, is that after first-line therapies in IBD have been used to diminishing effect, patients typically have waited up to between 6 and 10 years before they are given the treatment that works best for them. By then, when a patient likely has experienced penetrating disease and fistulas, even the most effective therapy has less than a 50% chance of working well.

This upside down state of affairs in the field is due to a combination of factors. Since the 1998 introduction to the U.S. market of infliximab for treating Crohn’s disease, much has been learned about the characteristics of IBD, including that it is a chronic, progressive condition with a higher burden of inflammation than is necessarily indicated by clinical symptoms.

But at the time infliximab was introduced, it was viewed not as a first-line treatment that could prevent further disease, but as a last ditch effort to halt an already rampant disease state that typically had its roots of destruction well planted long before the patient presented clinically, according to Dr. Hanauer.

In the last 2 decades, however, numerous studies have shown that earlier intervention with biologics results in higher treatment response rates and less structural trauma. []

In addition, data indicate that administering the correct choice of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent in biologic-naive patients will yield as much as a 20% greater response rate, which could lead to lower costs. “Long-term pharmacoeconomic data are needed to include not only direct costs of care, but also indirect costs that capture lost income, productivity, [and] disability,” Dr. Hanauer said in an interview.

As it stands now, even vedolizumab, indicated in 2014 for use in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is kept for an even later stage of disease in the standard algorithm, coming behind not only “severe stage of disease” but placed after a patient has failed other anti-TNF treatment.

Biologics are far safer than the corticosteroids, which precede them in the typical treatment algorithm, but because cost is king, according Dr. Hanauer, “it’s the cost that drives our later-stage intervention … if anti-TNFs cost a dollar, we’d use them in everything.”

“We would see more impact if we move these therapies earlier into treatment,” he said. “Now we give the patients least likely to respond to these treatments, the [costliest] therapies,” Dr. Hanauer said during his presentation.

Meanwhile, the several novel IBD therapies in development are primarily being tested for late-stage disease. Changing the criteria for inclusion in such clinical trials could mean future treatment is more cost effective. “Study sponsors could go after ‘earlier’ indications in the mild to moderate range,” he said in the interview.

To improve the treatment algorithms already in use, Dr. Hanauer said clinicians should learn more about the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of their armamentarium, something he said most clinical trials tend to ignore. “Most [IBD] drugs were developed for rheumatoid arthritis where these kinds of considerations are not as important since they have many more ‘tools’ [to choose from] in rheumatology. In IBD, we have had to make the best of our limited tools. Industry would prefer to keep things simple, but it isn’t.”

Also availing themselves of therapeutic drug monitoring would help clinicians ensure that patients have high enough blood levels of their treatment at the time they complete induction therapy, making the management phase easier, Dr. Hanauer said.

Redefining disease severity will mean that new treatments will have more efficacy, and can lead to more opportunities for novel treatments to work. Until then, leaving biologics to be the agent of last resort means, according to Dr. Hanauer, there are more patients “who have none of the benefit and all of the risk.”

Dr. Hanauer reported several relevant financial disclosures, including AbbVie, Actavis, Hospira, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer.

Potential new inflammatory bowel disease treatments

Adhesion molecule–based therapies

• PF-00547659 (Pfizer), an anti-MAdCam S1P1 agonist; an oral agent; for ulcerative colitis

• Ozanimod (Celgene); for ulcerative colitis; now in phase III

• Etrolizumab (Hoffmann-La Roche); for Crohn’s disease; now in phase III

Biologics for IL-12/23 pathways

MEDI2070 (MedImmune/Amgen), an anti-p19 antibody; targets IL-23 for Crohn’s disease

Agents for the JAK-STAT pathway

• Mongersen (Celgene), an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide; for Crohn’s disease; in phase III

• Tofacitinib (Pfizer)

Sources: Dr. Brian Feagan, University of Western Ontario; Dr. Bruce Sands, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Dr. Bill Sandborn, University of California, San Diego

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2015 ADVANCES IN IBD

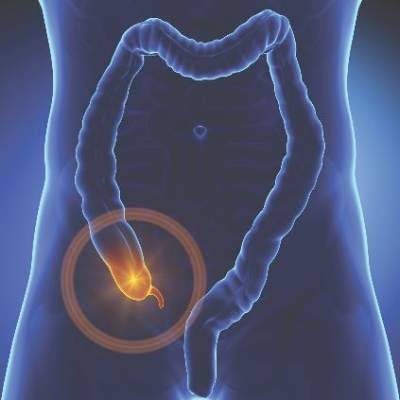

Jury still out on appendectomy vs. antibiotics-first approach

Despite a growing movement toward the antibiotics-first approach instead of surgical intervention for uncomplicated appendicitis, a new review of existing literature shows that the jury is still out on how to advise patients about their choices, according to Dr. Anne P. Ehlers and her colleagues who undertook the study.

The findings show that surgical intervention should continue to be considered a viable option and that appendectomy is not necessarily any better or worse in terms of long-term complication rates and length of hospital stay (J Am Coll Surg. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.11.009).

“What we found is that treatment of acute, uncomplicated appendicitis with antibiotics first is probably a safe approach, but that there are many questions that need to be answered before we can fully inform our patients about the long-term outcomes of this treatment strategy,” Dr. Ehlers of the department of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Dr. Ehlers and her coinvestigators combed the PubMed and EMBASE databases for all English-language randomized controlled trials involving comparisons of antibiotic and appendectomy-based treatments for acute appendicitis. Studies were excluded if they lacked adult population investigation.

“Our study is a critical review of the literature [available] on this topic to understand the current state of evidence,” explained Dr. Ehlers, adding that the study’s main goal was to answer the most common questions she and her coauthors encountered when talking to physicians and patients about the benefits and risks of antibiotics-first over appendectomy; namely, “Is my appendicitis going to come back?” “Am I going to have a lot of extra trips to the hospital?” and “What’s my quality of life going to be?”

Ultimately, six trials, comprising 1,720 patients, were selected for inclusion. These studies were led by Dr. S. Eriksson (40 subjects), Dr. J. Styrud (252 subjects), Dr. A.N. Turhan (290 subjects), Dr. J. Hansson (369 subjects), Dr. C. Vons (239 subjects), and Dr. P. Salminen (530 subjects). The Styrud study did not enroll any women, and no study enrolled subjects older than 75 years of age, but the average age of each study’s patients ranged from 26 to 38 years.

Length-of-stay comparisons between appendectomy and antibiotics-first cohorts varied among the studies, but most showed the same or longer LOS for antibiotics-first subjects. Mean LOS was 3.3 for surgical patients vs. 3.1 for antibiotics (Eriksson), 2.6 surgical vs. 3.0 antibiotics (Styrud), 2.4 surgical vs. 3.14 antibiotics (Turhan), 3.0 for both (Hansson), 3.04 surgical vs. 3.96 antibiotics (Vons), and 3.0 for both (Salminen).

Rates of appendectomy among patients treated with an antibiotics-first approach varied as well, with a 35% rate in the Eriksson study (7 out of the 20 subjects treated with antibiotics-first) and a 24% rate in the Styrud and Turhan studies. The Hansson trial reported an unusually high crossover between cohorts of 60%, the investigators noted.

Two studies – those led by Turhan and Vons – noted higher rates of complications in antibiotics-first patients versus those who received surgical intervention: 4.7% vs. 4.4%, and 2.5% vs. less than 1%, respectively. All other studies had high rates of complications in the surgical cohorts, with the Eriksson study reporting no complications whatsoever among antibiotics-first subjects.

These findings, Dr. Ehlers stressed, are just a first step. This review’s relatively low sample size and limiting factors require that further studies be done to more firmly ascertain which option for appendicitis treatment is the most beneficial. To that end, Dr. Ehlers said that she and her coinvestigators are working on that next step.

“Our group is currently working on a study called the CODA [Comparing Outcomes of Drugs in Appendectomy] Study,” she said, with the goal of answering “questions about long-term patient-centered outcomes related to the antibiotics-first approach.” These questions include patients’ quality of life, whether patients have decisional regret about choosing one treatment strategy over another, if they develop long-term anxiety any time they experience even a small abdominal pain, how much time they miss from school or work by choosing one treatment option over another, and so on.

The goal of this study is that physicians “will be able to give [patients] a more informed view of what each treatment entails,” she said. Funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the study has no firm date of publication.

Dr. Ehlers disclosed receiving support via a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Despite a growing movement toward the antibiotics-first approach instead of surgical intervention for uncomplicated appendicitis, a new review of existing literature shows that the jury is still out on how to advise patients about their choices, according to Dr. Anne P. Ehlers and her colleagues who undertook the study.

The findings show that surgical intervention should continue to be considered a viable option and that appendectomy is not necessarily any better or worse in terms of long-term complication rates and length of hospital stay (J Am Coll Surg. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.11.009).

“What we found is that treatment of acute, uncomplicated appendicitis with antibiotics first is probably a safe approach, but that there are many questions that need to be answered before we can fully inform our patients about the long-term outcomes of this treatment strategy,” Dr. Ehlers of the department of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Dr. Ehlers and her coinvestigators combed the PubMed and EMBASE databases for all English-language randomized controlled trials involving comparisons of antibiotic and appendectomy-based treatments for acute appendicitis. Studies were excluded if they lacked adult population investigation.

“Our study is a critical review of the literature [available] on this topic to understand the current state of evidence,” explained Dr. Ehlers, adding that the study’s main goal was to answer the most common questions she and her coauthors encountered when talking to physicians and patients about the benefits and risks of antibiotics-first over appendectomy; namely, “Is my appendicitis going to come back?” “Am I going to have a lot of extra trips to the hospital?” and “What’s my quality of life going to be?”

Ultimately, six trials, comprising 1,720 patients, were selected for inclusion. These studies were led by Dr. S. Eriksson (40 subjects), Dr. J. Styrud (252 subjects), Dr. A.N. Turhan (290 subjects), Dr. J. Hansson (369 subjects), Dr. C. Vons (239 subjects), and Dr. P. Salminen (530 subjects). The Styrud study did not enroll any women, and no study enrolled subjects older than 75 years of age, but the average age of each study’s patients ranged from 26 to 38 years.

Length-of-stay comparisons between appendectomy and antibiotics-first cohorts varied among the studies, but most showed the same or longer LOS for antibiotics-first subjects. Mean LOS was 3.3 for surgical patients vs. 3.1 for antibiotics (Eriksson), 2.6 surgical vs. 3.0 antibiotics (Styrud), 2.4 surgical vs. 3.14 antibiotics (Turhan), 3.0 for both (Hansson), 3.04 surgical vs. 3.96 antibiotics (Vons), and 3.0 for both (Salminen).

Rates of appendectomy among patients treated with an antibiotics-first approach varied as well, with a 35% rate in the Eriksson study (7 out of the 20 subjects treated with antibiotics-first) and a 24% rate in the Styrud and Turhan studies. The Hansson trial reported an unusually high crossover between cohorts of 60%, the investigators noted.

Two studies – those led by Turhan and Vons – noted higher rates of complications in antibiotics-first patients versus those who received surgical intervention: 4.7% vs. 4.4%, and 2.5% vs. less than 1%, respectively. All other studies had high rates of complications in the surgical cohorts, with the Eriksson study reporting no complications whatsoever among antibiotics-first subjects.

These findings, Dr. Ehlers stressed, are just a first step. This review’s relatively low sample size and limiting factors require that further studies be done to more firmly ascertain which option for appendicitis treatment is the most beneficial. To that end, Dr. Ehlers said that she and her coinvestigators are working on that next step.

“Our group is currently working on a study called the CODA [Comparing Outcomes of Drugs in Appendectomy] Study,” she said, with the goal of answering “questions about long-term patient-centered outcomes related to the antibiotics-first approach.” These questions include patients’ quality of life, whether patients have decisional regret about choosing one treatment strategy over another, if they develop long-term anxiety any time they experience even a small abdominal pain, how much time they miss from school or work by choosing one treatment option over another, and so on.

The goal of this study is that physicians “will be able to give [patients] a more informed view of what each treatment entails,” she said. Funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the study has no firm date of publication.

Dr. Ehlers disclosed receiving support via a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Despite a growing movement toward the antibiotics-first approach instead of surgical intervention for uncomplicated appendicitis, a new review of existing literature shows that the jury is still out on how to advise patients about their choices, according to Dr. Anne P. Ehlers and her colleagues who undertook the study.

The findings show that surgical intervention should continue to be considered a viable option and that appendectomy is not necessarily any better or worse in terms of long-term complication rates and length of hospital stay (J Am Coll Surg. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.11.009).

“What we found is that treatment of acute, uncomplicated appendicitis with antibiotics first is probably a safe approach, but that there are many questions that need to be answered before we can fully inform our patients about the long-term outcomes of this treatment strategy,” Dr. Ehlers of the department of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Dr. Ehlers and her coinvestigators combed the PubMed and EMBASE databases for all English-language randomized controlled trials involving comparisons of antibiotic and appendectomy-based treatments for acute appendicitis. Studies were excluded if they lacked adult population investigation.

“Our study is a critical review of the literature [available] on this topic to understand the current state of evidence,” explained Dr. Ehlers, adding that the study’s main goal was to answer the most common questions she and her coauthors encountered when talking to physicians and patients about the benefits and risks of antibiotics-first over appendectomy; namely, “Is my appendicitis going to come back?” “Am I going to have a lot of extra trips to the hospital?” and “What’s my quality of life going to be?”

Ultimately, six trials, comprising 1,720 patients, were selected for inclusion. These studies were led by Dr. S. Eriksson (40 subjects), Dr. J. Styrud (252 subjects), Dr. A.N. Turhan (290 subjects), Dr. J. Hansson (369 subjects), Dr. C. Vons (239 subjects), and Dr. P. Salminen (530 subjects). The Styrud study did not enroll any women, and no study enrolled subjects older than 75 years of age, but the average age of each study’s patients ranged from 26 to 38 years.

Length-of-stay comparisons between appendectomy and antibiotics-first cohorts varied among the studies, but most showed the same or longer LOS for antibiotics-first subjects. Mean LOS was 3.3 for surgical patients vs. 3.1 for antibiotics (Eriksson), 2.6 surgical vs. 3.0 antibiotics (Styrud), 2.4 surgical vs. 3.14 antibiotics (Turhan), 3.0 for both (Hansson), 3.04 surgical vs. 3.96 antibiotics (Vons), and 3.0 for both (Salminen).

Rates of appendectomy among patients treated with an antibiotics-first approach varied as well, with a 35% rate in the Eriksson study (7 out of the 20 subjects treated with antibiotics-first) and a 24% rate in the Styrud and Turhan studies. The Hansson trial reported an unusually high crossover between cohorts of 60%, the investigators noted.

Two studies – those led by Turhan and Vons – noted higher rates of complications in antibiotics-first patients versus those who received surgical intervention: 4.7% vs. 4.4%, and 2.5% vs. less than 1%, respectively. All other studies had high rates of complications in the surgical cohorts, with the Eriksson study reporting no complications whatsoever among antibiotics-first subjects.

These findings, Dr. Ehlers stressed, are just a first step. This review’s relatively low sample size and limiting factors require that further studies be done to more firmly ascertain which option for appendicitis treatment is the most beneficial. To that end, Dr. Ehlers said that she and her coinvestigators are working on that next step.

“Our group is currently working on a study called the CODA [Comparing Outcomes of Drugs in Appendectomy] Study,” she said, with the goal of answering “questions about long-term patient-centered outcomes related to the antibiotics-first approach.” These questions include patients’ quality of life, whether patients have decisional regret about choosing one treatment strategy over another, if they develop long-term anxiety any time they experience even a small abdominal pain, how much time they miss from school or work by choosing one treatment option over another, and so on.

The goal of this study is that physicians “will be able to give [patients] a more informed view of what each treatment entails,” she said. Funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the study has no firm date of publication.

Dr. Ehlers disclosed receiving support via a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: While the antibiotics-first approach to uncomplicated appendicitis has become increasingly popular in recent years, existing evidence shows that appendectomy is not inferior in terms of hospital stay and rates of complications.

Major finding: Length-of-stay and complication rates vary among all six included studies between antibiotics-first and surgical cohorts, indicating that neither one is definitively better or worse than the other.

Data source: Literature review of 1,720 appendicitis patients across six studies selected from PubMed and EMBASE databases.

Disclosures: The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the study. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Biosimilars primer: What you need to know now

ORLANDO – Regardless of what you think about using biosimilars, chances are you won’t be able to avoid using them if you already use biologics.

That’s according to Dr. David T. Rubin, codirector of the Digestive Diseases Center at the University of Chicago. “They’re coming and they will influence our practice, ” he told a clinical track audience at a conference on inflammatory bowel disease.

Before exploring how these medications may change how you treat patients, here’s a look at what they are and how they’re brought to market.

First, a little basic science review of small-molecule medications vs. biologic ones. Small-molecule agents are simple structures, which are stable enough to be replicated, do not tend to cause immunogenicity, and require very little in the way of testing for quality assurance.

By contrast, biologic medicines, including monoclonal antibodies, are complex structures – in some cases, highly complex – that are replicable, but often with a high degree of difficulty. Unlike small-molecule medicines, biologic drugs cannot be mass produced and require almost 250 sophisticated tests to ensure quality. They are less stable and can trigger an immunogenic response. The manufacturing process for biologics is so precise that the slightest disturbance in development can affect whether the medication is functional.

As a result, the typical development timeline for these medications is between 7 and 8 years, with costs running as high as $250 million each. Currently, there are more than 650 recombinant therapeutics in development worldwide, more than half of which are in the preclinical stage. The top original products being copied are adalimumab at 13, and infliximab with 9. Meanwhile, at least five as-of-yet unpublished studies are looking at how these potential adalimumab and infliximab biosimilars perform in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Dr. Rubin said. Biosimilars are used worldwide, primarily in Europe and Asia.

But when these biosimilars reach our shores, don’t call them generics. “I encourage you to not use that term, even when discussing them with patients,” Dr. Rubin said. Still, because the Food and Drug Administration says that a biosimilar should have no greater risk for adverse events or diminished efficacy compared with the original biologic just as with generics, pharmacists are within their rights to substitute biosimilars for original biologics without prescriber intervention.

That’s why, “There must be pharmacovigilance with biosimilars, just like with generics, after the drug is brought to market,” Dr. Rubin said.

Biosimilars are also not “biobetters,” medications that have modifications added to the original biologic product in order to improve their clinical performance. While biobetters can be patented, they do not have legal or regulatory status, however, because they are considered new drugs.

The FDA defines biosimilars as a biological product that is highly similar to the reference product, with no clinically meaningful safety, purity, or potency differences from the reference product.

Early in 2015, the biosimilar filgrastim-sndz (Zarxio TM, Sandoz-Novartis), which has been available in Europe since 2009, entered the U.S. market. With its biosimilarity to Filgrastim (Sandoz-Novartis), the medication’s primary indications are for various cancers and chronic neutropenia.

To help expedite bringing the medications to market, FDA guidance data requirements for biosimilars is abbreviated when compared with that for biologics. Rather than ask developers to conduct clinical trials, developers must provide at least one comparative study between the biosimilar and its original, according to the original drug’s indication. There also is what Dr. Rubin called a “weighted reliance” on analytical similarity to the original. In addition, no phase II dose-ranging studies are required. Indication extrapolation is also possible, meaning that safety and efficacy data leading to a biosimilar being approved for say, rheumatoid arthritis, could also be applied to Crohn’s disease.

So, what does all this mean for your patients? It depends upon in which state you practice: Even when a recombinant product meets the FDA criteria, whether or not a patient can be placed on a biosimilar comes down to state regulation. At present, 19 states have passed laws as to how and when biosimilars can be swapped out, most of them stipulating that a patient be notified when it occurs. Physicians maintain their rights to ask pharmacists to “dispense as written,” but since biosimilars are cheaper than their originals, you won’t necessarily get around mounting pressure from third-party payers to contain costs.

Dr. Rubin said this potential friction between insurers and physicians could result in delays with adverse effect on the patient. “If the insurance company says they prefer another agent over the one a patient is receiving, we all know about the unexpected delays that can occur when switching.”

Dr. Rubin predicted that the logistics of prescribing will be complicated by pharmaceutical marketing efforts. He noted the similar names of Remsima (Hospira) vs. Remicade (Janssen), Inflectra (Hospira) vs. infliximab generic. “It could be confusing for all of us.”

The question of how the drug will fare once inside the patient is still a matter of debate.

“The major issue is immunogenicity ... it’s impossible to predict in vitro,” said Dr. Brian Feagan, a copanelist with Dr. Rubin, and a professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada. “Immunogenicity is determined by product-related factors, and a lot of clinical ones such as immunosuppression, coadministration, route of administration, disease-specific factors.”

The only way to truly determine the impact on immunogenicity of interchangeability, whether because of third-party payer stipulations or physician’s choice, is to do multiple switching trials, said Dr. Feagan.

But Dr. Stephen B. Hanauer, the Clifford Joseph Barborka Professor of Medicine in Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern University (Chicago), said that’s not likely to happen. “There’s no time for that as the FDA regulatory evaluation proceeds,” he said in an interview.

“The trial would take 2 years to accomplish, would need large numbers of patients in order to identify potential small differences, and would be too expensive.” All of which would defeat the purpose of the expedited approval process, Dr. Hanauer said, because the decision by Congress to give biosimilars the green light was to reduce cost.

On the other hand, said Dr. Feagan, the experiment on switching probably has already been done. That’s because despite what he referred to as efforts by pharmaceutical manufacturers to reassure physicians there is no drift from the original product, heterogeneity is inevitable.

These iterative qualities, according to Dr. Hanauer, essentially make the original products into biosimilars of themselves. Add to that, he said that depending upon the company used to perform the assays to determine immunogenicity, the range of results can vary widely, and you end up having to learn to live with a certain amount of uncertainty. “I’m not afraid of biosimilars,” Dr. Hanauer said while discussing biosimilars during an audience question time at the meeting.

“We are a little bit timid about biosimilars, but my sense is we will find our comfort level in the next few years, and we will start using them frequently,” Dr. Miguel Regueiro, medical director of the IBD Center at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview. “I think immunogenicity to biosimilars will be the same immunogenicity to the innovative biologics, but I don’t think we’re going to be comfortable with interchanging a biosimilar with a[n] original biologic because of the potential immunogenicity that can occur by switching between agents.”

Whether biosimilars can be used in place of their originals, said both Dr. Feagan and Dr. Hanauer, will come down to how extrapolated data is interpreted.

“I think the biggest debate the FDA is going to have [when indicating biosimilars for IBD] is overextrapolation,” Dr. Hanauer said in the interview. Since the FDA does not require clinical trials for biosimilars, but relies upon analytics instead, and because there are far less clinical data for biologics in IBD than there are for diseases such as rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis, manufacturers will turn to those studies to demonstrate efficacy between originals and recombinants. “If 99.9% of the analytic assays and the clinical data in rheumatoid arthritis are virtually the same, I would assume that the data in inflammatory bowel disease is going to be virtually the same.”

However, at least in Canada, that was not the opinion of regulators who decided against approving the extrapolation of infliximab clinical data for indicating its biosimilar in IBD, but did allow extrapolation of the data for rheumatoid arthritis. “Health Canada decided that the antibody-dependent, cell-mediated cytotoxicity was different for IBD,” said Dr. Feagan.

Predicting the primacy of cost over keeping patients in remission, but at least for now, Dr. Rubin said the question of cost is “huge. Based on the European and Asian experience, the day one of these new products becomes available, the price of the existing therapies drops anywhere from 15% to 30%.”

Recent data places the cost of remission in the United States using infliximab at about $15,000.

Dr. Regueiro said these market forces are a good thing. “I don’t look at biosimilars in a negative context whatsoever. I think they are a necessary part of health care reform. Cost is definitely a driver, and that’s not bad.”

The meeting was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Rubin has financial and consulting relationships with AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Feagan has numerous relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Abbott, Janssen, Teva, and others. Dr. Hanauer has served on the board of AbbVie and has financial relationships with numerous other pharmaceutical manufacturers. Dr. Regueiro did not have any disclosures relevant to this story.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

This article was updated 1/6/16.

ORLANDO – Regardless of what you think about using biosimilars, chances are you won’t be able to avoid using them if you already use biologics.

That’s according to Dr. David T. Rubin, codirector of the Digestive Diseases Center at the University of Chicago. “They’re coming and they will influence our practice, ” he told a clinical track audience at a conference on inflammatory bowel disease.

Before exploring how these medications may change how you treat patients, here’s a look at what they are and how they’re brought to market.

First, a little basic science review of small-molecule medications vs. biologic ones. Small-molecule agents are simple structures, which are stable enough to be replicated, do not tend to cause immunogenicity, and require very little in the way of testing for quality assurance.

By contrast, biologic medicines, including monoclonal antibodies, are complex structures – in some cases, highly complex – that are replicable, but often with a high degree of difficulty. Unlike small-molecule medicines, biologic drugs cannot be mass produced and require almost 250 sophisticated tests to ensure quality. They are less stable and can trigger an immunogenic response. The manufacturing process for biologics is so precise that the slightest disturbance in development can affect whether the medication is functional.

As a result, the typical development timeline for these medications is between 7 and 8 years, with costs running as high as $250 million each. Currently, there are more than 650 recombinant therapeutics in development worldwide, more than half of which are in the preclinical stage. The top original products being copied are adalimumab at 13, and infliximab with 9. Meanwhile, at least five as-of-yet unpublished studies are looking at how these potential adalimumab and infliximab biosimilars perform in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Dr. Rubin said. Biosimilars are used worldwide, primarily in Europe and Asia.

But when these biosimilars reach our shores, don’t call them generics. “I encourage you to not use that term, even when discussing them with patients,” Dr. Rubin said. Still, because the Food and Drug Administration says that a biosimilar should have no greater risk for adverse events or diminished efficacy compared with the original biologic just as with generics, pharmacists are within their rights to substitute biosimilars for original biologics without prescriber intervention.

That’s why, “There must be pharmacovigilance with biosimilars, just like with generics, after the drug is brought to market,” Dr. Rubin said.

Biosimilars are also not “biobetters,” medications that have modifications added to the original biologic product in order to improve their clinical performance. While biobetters can be patented, they do not have legal or regulatory status, however, because they are considered new drugs.

The FDA defines biosimilars as a biological product that is highly similar to the reference product, with no clinically meaningful safety, purity, or potency differences from the reference product.

Early in 2015, the biosimilar filgrastim-sndz (Zarxio TM, Sandoz-Novartis), which has been available in Europe since 2009, entered the U.S. market. With its biosimilarity to Filgrastim (Sandoz-Novartis), the medication’s primary indications are for various cancers and chronic neutropenia.

To help expedite bringing the medications to market, FDA guidance data requirements for biosimilars is abbreviated when compared with that for biologics. Rather than ask developers to conduct clinical trials, developers must provide at least one comparative study between the biosimilar and its original, according to the original drug’s indication. There also is what Dr. Rubin called a “weighted reliance” on analytical similarity to the original. In addition, no phase II dose-ranging studies are required. Indication extrapolation is also possible, meaning that safety and efficacy data leading to a biosimilar being approved for say, rheumatoid arthritis, could also be applied to Crohn’s disease.

So, what does all this mean for your patients? It depends upon in which state you practice: Even when a recombinant product meets the FDA criteria, whether or not a patient can be placed on a biosimilar comes down to state regulation. At present, 19 states have passed laws as to how and when biosimilars can be swapped out, most of them stipulating that a patient be notified when it occurs. Physicians maintain their rights to ask pharmacists to “dispense as written,” but since biosimilars are cheaper than their originals, you won’t necessarily get around mounting pressure from third-party payers to contain costs.

Dr. Rubin said this potential friction between insurers and physicians could result in delays with adverse effect on the patient. “If the insurance company says they prefer another agent over the one a patient is receiving, we all know about the unexpected delays that can occur when switching.”

Dr. Rubin predicted that the logistics of prescribing will be complicated by pharmaceutical marketing efforts. He noted the similar names of Remsima (Hospira) vs. Remicade (Janssen), Inflectra (Hospira) vs. infliximab generic. “It could be confusing for all of us.”

The question of how the drug will fare once inside the patient is still a matter of debate.

“The major issue is immunogenicity ... it’s impossible to predict in vitro,” said Dr. Brian Feagan, a copanelist with Dr. Rubin, and a professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada. “Immunogenicity is determined by product-related factors, and a lot of clinical ones such as immunosuppression, coadministration, route of administration, disease-specific factors.”

The only way to truly determine the impact on immunogenicity of interchangeability, whether because of third-party payer stipulations or physician’s choice, is to do multiple switching trials, said Dr. Feagan.

But Dr. Stephen B. Hanauer, the Clifford Joseph Barborka Professor of Medicine in Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern University (Chicago), said that’s not likely to happen. “There’s no time for that as the FDA regulatory evaluation proceeds,” he said in an interview.

“The trial would take 2 years to accomplish, would need large numbers of patients in order to identify potential small differences, and would be too expensive.” All of which would defeat the purpose of the expedited approval process, Dr. Hanauer said, because the decision by Congress to give biosimilars the green light was to reduce cost.

On the other hand, said Dr. Feagan, the experiment on switching probably has already been done. That’s because despite what he referred to as efforts by pharmaceutical manufacturers to reassure physicians there is no drift from the original product, heterogeneity is inevitable.

These iterative qualities, according to Dr. Hanauer, essentially make the original products into biosimilars of themselves. Add to that, he said that depending upon the company used to perform the assays to determine immunogenicity, the range of results can vary widely, and you end up having to learn to live with a certain amount of uncertainty. “I’m not afraid of biosimilars,” Dr. Hanauer said while discussing biosimilars during an audience question time at the meeting.

“We are a little bit timid about biosimilars, but my sense is we will find our comfort level in the next few years, and we will start using them frequently,” Dr. Miguel Regueiro, medical director of the IBD Center at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview. “I think immunogenicity to biosimilars will be the same immunogenicity to the innovative biologics, but I don’t think we’re going to be comfortable with interchanging a biosimilar with a[n] original biologic because of the potential immunogenicity that can occur by switching between agents.”

Whether biosimilars can be used in place of their originals, said both Dr. Feagan and Dr. Hanauer, will come down to how extrapolated data is interpreted.

“I think the biggest debate the FDA is going to have [when indicating biosimilars for IBD] is overextrapolation,” Dr. Hanauer said in the interview. Since the FDA does not require clinical trials for biosimilars, but relies upon analytics instead, and because there are far less clinical data for biologics in IBD than there are for diseases such as rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis, manufacturers will turn to those studies to demonstrate efficacy between originals and recombinants. “If 99.9% of the analytic assays and the clinical data in rheumatoid arthritis are virtually the same, I would assume that the data in inflammatory bowel disease is going to be virtually the same.”

However, at least in Canada, that was not the opinion of regulators who decided against approving the extrapolation of infliximab clinical data for indicating its biosimilar in IBD, but did allow extrapolation of the data for rheumatoid arthritis. “Health Canada decided that the antibody-dependent, cell-mediated cytotoxicity was different for IBD,” said Dr. Feagan.

Predicting the primacy of cost over keeping patients in remission, but at least for now, Dr. Rubin said the question of cost is “huge. Based on the European and Asian experience, the day one of these new products becomes available, the price of the existing therapies drops anywhere from 15% to 30%.”

Recent data places the cost of remission in the United States using infliximab at about $15,000.

Dr. Regueiro said these market forces are a good thing. “I don’t look at biosimilars in a negative context whatsoever. I think they are a necessary part of health care reform. Cost is definitely a driver, and that’s not bad.”

The meeting was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Rubin has financial and consulting relationships with AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Feagan has numerous relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Abbott, Janssen, Teva, and others. Dr. Hanauer has served on the board of AbbVie and has financial relationships with numerous other pharmaceutical manufacturers. Dr. Regueiro did not have any disclosures relevant to this story.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

This article was updated 1/6/16.

ORLANDO – Regardless of what you think about using biosimilars, chances are you won’t be able to avoid using them if you already use biologics.

That’s according to Dr. David T. Rubin, codirector of the Digestive Diseases Center at the University of Chicago. “They’re coming and they will influence our practice, ” he told a clinical track audience at a conference on inflammatory bowel disease.

Before exploring how these medications may change how you treat patients, here’s a look at what they are and how they’re brought to market.

First, a little basic science review of small-molecule medications vs. biologic ones. Small-molecule agents are simple structures, which are stable enough to be replicated, do not tend to cause immunogenicity, and require very little in the way of testing for quality assurance.

By contrast, biologic medicines, including monoclonal antibodies, are complex structures – in some cases, highly complex – that are replicable, but often with a high degree of difficulty. Unlike small-molecule medicines, biologic drugs cannot be mass produced and require almost 250 sophisticated tests to ensure quality. They are less stable and can trigger an immunogenic response. The manufacturing process for biologics is so precise that the slightest disturbance in development can affect whether the medication is functional.

As a result, the typical development timeline for these medications is between 7 and 8 years, with costs running as high as $250 million each. Currently, there are more than 650 recombinant therapeutics in development worldwide, more than half of which are in the preclinical stage. The top original products being copied are adalimumab at 13, and infliximab with 9. Meanwhile, at least five as-of-yet unpublished studies are looking at how these potential adalimumab and infliximab biosimilars perform in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Dr. Rubin said. Biosimilars are used worldwide, primarily in Europe and Asia.

But when these biosimilars reach our shores, don’t call them generics. “I encourage you to not use that term, even when discussing them with patients,” Dr. Rubin said. Still, because the Food and Drug Administration says that a biosimilar should have no greater risk for adverse events or diminished efficacy compared with the original biologic just as with generics, pharmacists are within their rights to substitute biosimilars for original biologics without prescriber intervention.

That’s why, “There must be pharmacovigilance with biosimilars, just like with generics, after the drug is brought to market,” Dr. Rubin said.

Biosimilars are also not “biobetters,” medications that have modifications added to the original biologic product in order to improve their clinical performance. While biobetters can be patented, they do not have legal or regulatory status, however, because they are considered new drugs.

The FDA defines biosimilars as a biological product that is highly similar to the reference product, with no clinically meaningful safety, purity, or potency differences from the reference product.

Early in 2015, the biosimilar filgrastim-sndz (Zarxio TM, Sandoz-Novartis), which has been available in Europe since 2009, entered the U.S. market. With its biosimilarity to Filgrastim (Sandoz-Novartis), the medication’s primary indications are for various cancers and chronic neutropenia.

To help expedite bringing the medications to market, FDA guidance data requirements for biosimilars is abbreviated when compared with that for biologics. Rather than ask developers to conduct clinical trials, developers must provide at least one comparative study between the biosimilar and its original, according to the original drug’s indication. There also is what Dr. Rubin called a “weighted reliance” on analytical similarity to the original. In addition, no phase II dose-ranging studies are required. Indication extrapolation is also possible, meaning that safety and efficacy data leading to a biosimilar being approved for say, rheumatoid arthritis, could also be applied to Crohn’s disease.

So, what does all this mean for your patients? It depends upon in which state you practice: Even when a recombinant product meets the FDA criteria, whether or not a patient can be placed on a biosimilar comes down to state regulation. At present, 19 states have passed laws as to how and when biosimilars can be swapped out, most of them stipulating that a patient be notified when it occurs. Physicians maintain their rights to ask pharmacists to “dispense as written,” but since biosimilars are cheaper than their originals, you won’t necessarily get around mounting pressure from third-party payers to contain costs.

Dr. Rubin said this potential friction between insurers and physicians could result in delays with adverse effect on the patient. “If the insurance company says they prefer another agent over the one a patient is receiving, we all know about the unexpected delays that can occur when switching.”

Dr. Rubin predicted that the logistics of prescribing will be complicated by pharmaceutical marketing efforts. He noted the similar names of Remsima (Hospira) vs. Remicade (Janssen), Inflectra (Hospira) vs. infliximab generic. “It could be confusing for all of us.”

The question of how the drug will fare once inside the patient is still a matter of debate.

“The major issue is immunogenicity ... it’s impossible to predict in vitro,” said Dr. Brian Feagan, a copanelist with Dr. Rubin, and a professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada. “Immunogenicity is determined by product-related factors, and a lot of clinical ones such as immunosuppression, coadministration, route of administration, disease-specific factors.”

The only way to truly determine the impact on immunogenicity of interchangeability, whether because of third-party payer stipulations or physician’s choice, is to do multiple switching trials, said Dr. Feagan.

But Dr. Stephen B. Hanauer, the Clifford Joseph Barborka Professor of Medicine in Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern University (Chicago), said that’s not likely to happen. “There’s no time for that as the FDA regulatory evaluation proceeds,” he said in an interview.

“The trial would take 2 years to accomplish, would need large numbers of patients in order to identify potential small differences, and would be too expensive.” All of which would defeat the purpose of the expedited approval process, Dr. Hanauer said, because the decision by Congress to give biosimilars the green light was to reduce cost.

On the other hand, said Dr. Feagan, the experiment on switching probably has already been done. That’s because despite what he referred to as efforts by pharmaceutical manufacturers to reassure physicians there is no drift from the original product, heterogeneity is inevitable.

These iterative qualities, according to Dr. Hanauer, essentially make the original products into biosimilars of themselves. Add to that, he said that depending upon the company used to perform the assays to determine immunogenicity, the range of results can vary widely, and you end up having to learn to live with a certain amount of uncertainty. “I’m not afraid of biosimilars,” Dr. Hanauer said while discussing biosimilars during an audience question time at the meeting.

“We are a little bit timid about biosimilars, but my sense is we will find our comfort level in the next few years, and we will start using them frequently,” Dr. Miguel Regueiro, medical director of the IBD Center at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview. “I think immunogenicity to biosimilars will be the same immunogenicity to the innovative biologics, but I don’t think we’re going to be comfortable with interchanging a biosimilar with a[n] original biologic because of the potential immunogenicity that can occur by switching between agents.”

Whether biosimilars can be used in place of their originals, said both Dr. Feagan and Dr. Hanauer, will come down to how extrapolated data is interpreted.

“I think the biggest debate the FDA is going to have [when indicating biosimilars for IBD] is overextrapolation,” Dr. Hanauer said in the interview. Since the FDA does not require clinical trials for biosimilars, but relies upon analytics instead, and because there are far less clinical data for biologics in IBD than there are for diseases such as rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis, manufacturers will turn to those studies to demonstrate efficacy between originals and recombinants. “If 99.9% of the analytic assays and the clinical data in rheumatoid arthritis are virtually the same, I would assume that the data in inflammatory bowel disease is going to be virtually the same.”

However, at least in Canada, that was not the opinion of regulators who decided against approving the extrapolation of infliximab clinical data for indicating its biosimilar in IBD, but did allow extrapolation of the data for rheumatoid arthritis. “Health Canada decided that the antibody-dependent, cell-mediated cytotoxicity was different for IBD,” said Dr. Feagan.

Predicting the primacy of cost over keeping patients in remission, but at least for now, Dr. Rubin said the question of cost is “huge. Based on the European and Asian experience, the day one of these new products becomes available, the price of the existing therapies drops anywhere from 15% to 30%.”

Recent data places the cost of remission in the United States using infliximab at about $15,000.

Dr. Regueiro said these market forces are a good thing. “I don’t look at biosimilars in a negative context whatsoever. I think they are a necessary part of health care reform. Cost is definitely a driver, and that’s not bad.”

The meeting was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Rubin has financial and consulting relationships with AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Feagan has numerous relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Abbott, Janssen, Teva, and others. Dr. Hanauer has served on the board of AbbVie and has financial relationships with numerous other pharmaceutical manufacturers. Dr. Regueiro did not have any disclosures relevant to this story.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

This article was updated 1/6/16.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2015 ADVANCES IN IBD

Anti-TNF therapy can continue for IBD patients with skin lesions

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients who experience skin lesions during anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy do not usually need to stop treatment, according to Isabelle Cleynen, Ph.D., of the University of Leuven (Belgium) and her associates.

In their retrospective study of 917 IBD patients who started treatment with infliximab at the University Hospitals Leuven between December 1994 and January 2009, 264 developed skin lesions during the follow-up period. The most common type was psoriasiform eczema, in 30.6% of the patients with lesions. Other common types included eczema (in 23.5%), xerosis cutis (10.6%), palmoplantar pustulosis (5.3%), and psoriasis (3.8%). Median cumulative doses and trough levels of infliximab were similar in people who developed skin lesions and those who did not.

Just over half of patients with skin lesions received only topical treatment, 1.9% received only systemic treatment, 28% received both, and 19.3% of patients required no specific treatment. Almost 11% of patients who developed skin lesions were forced to stop therapy. Reasons for stopping treatment included an intolerable location of lesions, concomitant itching or pain, recurring episodes, and concomitant arthralgia.