User login

Cold viruses thrived in kids as other viruses faded in 2020

The common-cold viruses rhinovirus (RV) and enterovirus (EV) continued to circulate among children during the COVID-19 pandemic while there were sharp declines in influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and other respiratory viruses, new data indicate.

Researchers used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network. The cases involved 37,676 children in seven geographically diverse U.S. medical centers between December 2016 and January 2021. Patients presented to emergency departments or were hospitalized with RV, EV, and other acute respiratory viruses.

The investigators found that the percentage of children in whom RV/EV was detected from March 2020 to January 2021 was similar to the percentage during the same months in 2017-2018 and 2019-2020. However, the proportion of children infected with influenza, RSV, and other respiratory viruses combined dropped significantly in comparison to the three prior seasons.

Danielle Rankin, MPH, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate in pediatric infectious disease at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., presented the study on Sept. 30 during a press conference at IDWeek 2021, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Reasoning for rhinovirus and enterovirus circulation is unknown but may be attributed to a number of factors, such as different transmission routes or the prolonged survival of the virus on surfaces,” Ms. Rankin said. “Improved understanding of these persistent factors of RV/EV and the role of nonpharmaceutical interventions on transmission dynamics can further guide future prevention recommendations and guidelines.”

Coauthor Claire Midgley, PhD, an epidemiologist in the Division of Viral Diseases at the CDC, told reporters that further studies will assess why RV and EV remained during the pandemic and which virus types within the RV/EV group persisted.

“We do know that the virus can spread through secretions on people’s hands,” she said. “Washing kids’ hands regularly and trying not to touch your face where possible is a really effective way to prevent transmission,” Dr. Midgley said.

“The more we understand about all of these factors, the better we can inform prevention measures.”

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, chief, division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that rhinoviruses can persist in the nose for a very long time, especially in younger children, which increases the opportunities for transmission.

“Very young children who are unable to wear masks or are unlikely to wear them well may be acting as the reservoir, allowing transmission in households,” he said. “There is also an enormous pool of diverse rhinoviruses, so past colds provide limited immunity, as everyone has found out from experience.”

Martha Perry, MD, associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and chief of adolescent medicine, told this news organization that some of the differences in the prevalence of viruses may be because of their seasonality.

“Times when there were more mask mandates were times when RSV and influenza are more prevalent,” said Dr. Perry, who was not involved with the study. “We were masking more intently during those times, and there was loosening of restrictions when we see more enterovirus, particularly because that tends to be more of a summer/fall virus.”

She agreed that the differences may result from the way the viruses are transmitted.

“Perhaps masks were helping with RSV and influenza, but perhaps there was not as much hand washing or cleansing as needed to prevent the spread of rhinovirus and enterovirus, because those are viruses that require a bit more hand washing,” Dr. Perry said. “They are less aerosolized and better spread with hand-to-hand contact.”

Dr. Perry added that on the flip side, “it’s really exciting that there are ways we can prevent RSV and influenza, which tend to cause more severe infection.”

Ms. Rankin said limitations of the study include the fact that from March 2020 to January 2021, health care–seeking behaviors may have changed because of the pandemic and that the study does not include the frequency of respiratory viruses in the outpatient setting.

The sharp 2020-2021 decline in RSV reported in the study may have reversed after many of the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted this summer.

This news organization reported in June of this year that the CDC has issued a health advisory to notify clinicians and caregivers about an increase in cases of interseasonal RSV in parts of the southern United States.

The CDC has urged broader testing for RSV among patients presenting with acute respiratory illness who test negative for SARS-CoV-2.

The study’s authors, Ms. Pavia, and Dr. Perry have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The common-cold viruses rhinovirus (RV) and enterovirus (EV) continued to circulate among children during the COVID-19 pandemic while there were sharp declines in influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and other respiratory viruses, new data indicate.

Researchers used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network. The cases involved 37,676 children in seven geographically diverse U.S. medical centers between December 2016 and January 2021. Patients presented to emergency departments or were hospitalized with RV, EV, and other acute respiratory viruses.

The investigators found that the percentage of children in whom RV/EV was detected from March 2020 to January 2021 was similar to the percentage during the same months in 2017-2018 and 2019-2020. However, the proportion of children infected with influenza, RSV, and other respiratory viruses combined dropped significantly in comparison to the three prior seasons.

Danielle Rankin, MPH, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate in pediatric infectious disease at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., presented the study on Sept. 30 during a press conference at IDWeek 2021, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Reasoning for rhinovirus and enterovirus circulation is unknown but may be attributed to a number of factors, such as different transmission routes or the prolonged survival of the virus on surfaces,” Ms. Rankin said. “Improved understanding of these persistent factors of RV/EV and the role of nonpharmaceutical interventions on transmission dynamics can further guide future prevention recommendations and guidelines.”

Coauthor Claire Midgley, PhD, an epidemiologist in the Division of Viral Diseases at the CDC, told reporters that further studies will assess why RV and EV remained during the pandemic and which virus types within the RV/EV group persisted.

“We do know that the virus can spread through secretions on people’s hands,” she said. “Washing kids’ hands regularly and trying not to touch your face where possible is a really effective way to prevent transmission,” Dr. Midgley said.

“The more we understand about all of these factors, the better we can inform prevention measures.”

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, chief, division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that rhinoviruses can persist in the nose for a very long time, especially in younger children, which increases the opportunities for transmission.

“Very young children who are unable to wear masks or are unlikely to wear them well may be acting as the reservoir, allowing transmission in households,” he said. “There is also an enormous pool of diverse rhinoviruses, so past colds provide limited immunity, as everyone has found out from experience.”

Martha Perry, MD, associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and chief of adolescent medicine, told this news organization that some of the differences in the prevalence of viruses may be because of their seasonality.

“Times when there were more mask mandates were times when RSV and influenza are more prevalent,” said Dr. Perry, who was not involved with the study. “We were masking more intently during those times, and there was loosening of restrictions when we see more enterovirus, particularly because that tends to be more of a summer/fall virus.”

She agreed that the differences may result from the way the viruses are transmitted.

“Perhaps masks were helping with RSV and influenza, but perhaps there was not as much hand washing or cleansing as needed to prevent the spread of rhinovirus and enterovirus, because those are viruses that require a bit more hand washing,” Dr. Perry said. “They are less aerosolized and better spread with hand-to-hand contact.”

Dr. Perry added that on the flip side, “it’s really exciting that there are ways we can prevent RSV and influenza, which tend to cause more severe infection.”

Ms. Rankin said limitations of the study include the fact that from March 2020 to January 2021, health care–seeking behaviors may have changed because of the pandemic and that the study does not include the frequency of respiratory viruses in the outpatient setting.

The sharp 2020-2021 decline in RSV reported in the study may have reversed after many of the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted this summer.

This news organization reported in June of this year that the CDC has issued a health advisory to notify clinicians and caregivers about an increase in cases of interseasonal RSV in parts of the southern United States.

The CDC has urged broader testing for RSV among patients presenting with acute respiratory illness who test negative for SARS-CoV-2.

The study’s authors, Ms. Pavia, and Dr. Perry have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The common-cold viruses rhinovirus (RV) and enterovirus (EV) continued to circulate among children during the COVID-19 pandemic while there were sharp declines in influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and other respiratory viruses, new data indicate.

Researchers used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network. The cases involved 37,676 children in seven geographically diverse U.S. medical centers between December 2016 and January 2021. Patients presented to emergency departments or were hospitalized with RV, EV, and other acute respiratory viruses.

The investigators found that the percentage of children in whom RV/EV was detected from March 2020 to January 2021 was similar to the percentage during the same months in 2017-2018 and 2019-2020. However, the proportion of children infected with influenza, RSV, and other respiratory viruses combined dropped significantly in comparison to the three prior seasons.

Danielle Rankin, MPH, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate in pediatric infectious disease at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., presented the study on Sept. 30 during a press conference at IDWeek 2021, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Reasoning for rhinovirus and enterovirus circulation is unknown but may be attributed to a number of factors, such as different transmission routes or the prolonged survival of the virus on surfaces,” Ms. Rankin said. “Improved understanding of these persistent factors of RV/EV and the role of nonpharmaceutical interventions on transmission dynamics can further guide future prevention recommendations and guidelines.”

Coauthor Claire Midgley, PhD, an epidemiologist in the Division of Viral Diseases at the CDC, told reporters that further studies will assess why RV and EV remained during the pandemic and which virus types within the RV/EV group persisted.

“We do know that the virus can spread through secretions on people’s hands,” she said. “Washing kids’ hands regularly and trying not to touch your face where possible is a really effective way to prevent transmission,” Dr. Midgley said.

“The more we understand about all of these factors, the better we can inform prevention measures.”

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, chief, division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that rhinoviruses can persist in the nose for a very long time, especially in younger children, which increases the opportunities for transmission.

“Very young children who are unable to wear masks or are unlikely to wear them well may be acting as the reservoir, allowing transmission in households,” he said. “There is also an enormous pool of diverse rhinoviruses, so past colds provide limited immunity, as everyone has found out from experience.”

Martha Perry, MD, associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and chief of adolescent medicine, told this news organization that some of the differences in the prevalence of viruses may be because of their seasonality.

“Times when there were more mask mandates were times when RSV and influenza are more prevalent,” said Dr. Perry, who was not involved with the study. “We were masking more intently during those times, and there was loosening of restrictions when we see more enterovirus, particularly because that tends to be more of a summer/fall virus.”

She agreed that the differences may result from the way the viruses are transmitted.

“Perhaps masks were helping with RSV and influenza, but perhaps there was not as much hand washing or cleansing as needed to prevent the spread of rhinovirus and enterovirus, because those are viruses that require a bit more hand washing,” Dr. Perry said. “They are less aerosolized and better spread with hand-to-hand contact.”

Dr. Perry added that on the flip side, “it’s really exciting that there are ways we can prevent RSV and influenza, which tend to cause more severe infection.”

Ms. Rankin said limitations of the study include the fact that from March 2020 to January 2021, health care–seeking behaviors may have changed because of the pandemic and that the study does not include the frequency of respiratory viruses in the outpatient setting.

The sharp 2020-2021 decline in RSV reported in the study may have reversed after many of the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted this summer.

This news organization reported in June of this year that the CDC has issued a health advisory to notify clinicians and caregivers about an increase in cases of interseasonal RSV in parts of the southern United States.

The CDC has urged broader testing for RSV among patients presenting with acute respiratory illness who test negative for SARS-CoV-2.

The study’s authors, Ms. Pavia, and Dr. Perry have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Role of Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

Dermatology is an often-underutilized resource in the hospital setting. As the health care landscape has evolved, so has the role of the inpatient dermatologist.1-3 Structural changes in the health system and advances in therapies have shifted dermatology from an admitting service to an almost exclusively outpatient practice. Improved treatment modalities led to decreases in the number of patients requiring admission for chronic dermatoses, and outpatient clinics began offering therapies once limited to hospitals.1,4 Inpatient dermatology consultations emerged and continue to have profound effects on hospitalized patients regardless of their reason for admission.1-11

Inpatient dermatologists supply knowledge in areas primary medical teams lack, and there is evidence that dermatology consultations improve the quality of care while decreasing cost.2,5-7 Establishing correct diagnoses, preventing exposure to unnecessary medications, and reducing hospitalization duration and readmission rates are a few ways dermatology consultations positively impact hospitalized patients.2,5-7,9,10 This study highlights the role of the dermatologist in the care of hospitalized patients at a large academic medical center in an urban setting and reveals how consultation supports the efficiency and efficacy of other services.

Materials and Methods

Study Design—This single-institution, cross-sectional retrospective study included all hospitalized patients at the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), who received an inpatient dermatology consultation completed by physicians of Jefferson Dermatology Associates between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2019. The institutional review board at Thomas Jefferson University approved this study.

Data Collection—A list of all inpatient dermatology consultations in 2019 was provided by Jefferson Dermatology Associates. Through a retrospective chart review, data regarding the consultations were collected from the electronic medical record (Epic Systems) and recorded into the Research Electronic Data Capture system. Data on patient demographics, the primary medical team, the dermatology evaluation, and the hospital course of the patient were collected.

Results

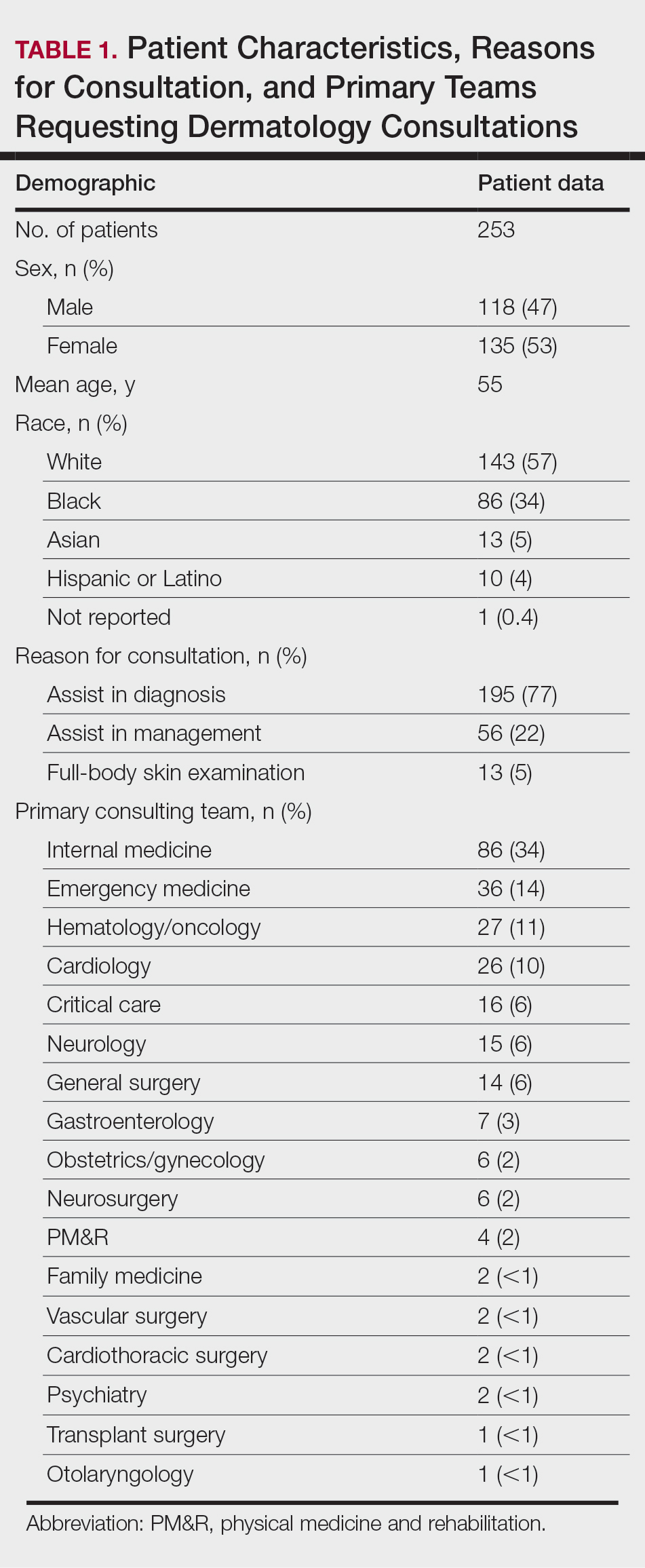

Patient Characteristics—Dermatology received 253 inpatient consultation requests during this time period; 53% of patients were female and 47% were male, with a mean age of 55 years. Most patients were White (57%), while 34% were Black. Five percent and 4% of patients were Asian and Hispanic or Latino, respectively (Table 1). The mean duration of hospitalization for all patients was 15 days, and the average number of days to discharge following the first encounter with dermatology was 10 days.

Requesting Team and Reason for Consultation—Internal medicine consulted dermatology most frequently (34% of all consultations), followed by emergency medicine (14%) and a variety of other services (Table 1). Most dermatology consultations were placed to assist in achieving a diagnosis of a cutaneous condition (77%), while a minority were to assist in the management of a previously diagnosed disease (22%). A small fraction of consultations (5%) were to complete full-body skin examinations (FBSEs) to rule out infection or malignancy in candidates for organ transplantation, left ventricular assist devices, or certain chemotherapies. One FBSE was conducted to search for a primary tumor in a patient diagnosed with metastatic melanoma.

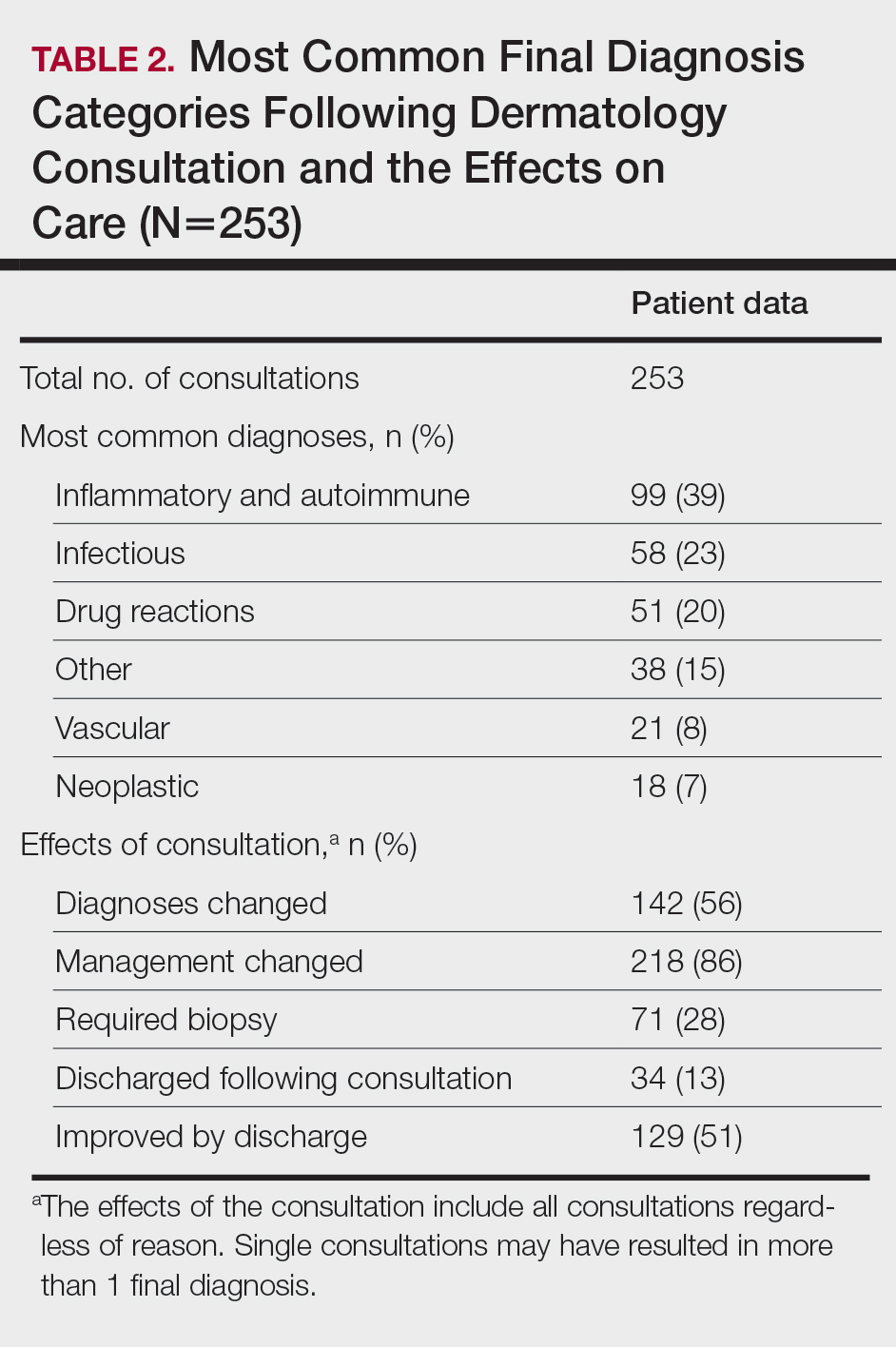

Most Common Final Diagnoses and Consultation Impact—Table 2 lists the most common final diagnosis categories, as well as the effects of the consultation on diagnosis, management, biopsies, hospitalization, and clinical improvement as documented by the primary medical provider. The most common final diagnoses were inflammatory and autoimmune (39%), such as contact dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis; infectious (23%), such as varicella (primary or zoster) and bacterial furunculosis; drug reactions (20%), such as morbilliform drug eruptions; vascular (8%), such as vasculitis and calciphylaxis; neoplastic (7%), such as keratinocyte carcinomas and leukemia cutis; and other (15%), such as xerosis, keratosis pilaris, and miliaria rubra.

Impact on Diagnosis—Fifty-six percent of all consultations resulted in a change in diagnosis. When dermatology was consulted specifically to assist in the diagnosis of a patient (195 consultations), the working diagnosis of the primary team was changed 69% of the time. Thirty-five of these consultation requests had no preliminary diagnosis, and the primary team listed the working diagnosis as either rash or a morphologic description of the lesion(s). Sixty-three percent of suspected drug eruptions ended with a diagnosis of a form of drug eruption, while 20% of consultations for suspected cellulitis or bacterial infections were confirmed to be cellulitis or soft tissue infections.

Impact on Management—Regardless of the reason for the consultation, most consultations (86%) resulted in a change in management. The remaining 14% consisted of FBSEs with benign findings; cases of cutaneous metastases and leukemia cutis managed by oncology; as well as select cases of purpura fulminans, postfebrile desquamation, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Changes in management included alterations in medications, requests for additional laboratory work or imaging, additional consultation requests, biopsies, or specific wound care instructions. Seventy-five percent of all consultations were given specific medication recommendations by dermatology. Most (61%) were recommended to be given a topical steroid, antibiotic, or both. However, 45% of all consultations were recommended to initiate a systemic medication, most commonly antihistamines, antibiotics, steroids, antivirals, or immunomodulators. Dermatology recommended discontinuing specific medications in 16% of all consultations, with antibiotics being the most frequent culprit (17 antibiotics discontinued), owing to drug eruptions or misdiagnosed infections. Vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were the most frequently discontinued antibiotics.

Dermatology was consulted for assistance in management of previously diagnosed cutaneous conditions 56 times (22% of all consultations), often regarding complicated cases of hidradenitis suppurativa (9 cases), pyoderma gangrenosum (5 cases), bullous pemphigoid (4 cases), or erythroderma (4 cases). Most of these cases required a single dermatology encounter to provide recommendations (71%), and 21% required 1 additional follow-up. Sixty-three percent of patients consulted for management assistance were noted to have improvement in their cutaneous condition by time of discharge, as documented by the primary provider in the medical record.

Twenty-eight percent of all consultations required at least 1 biopsy. Seventy-two percent of all biopsies were consistent with the dermatologist’s working diagnosis or highest-ranked differential diagnosis, and 16% of biopsy results were consistent with the second- or third-ranked diagnosis. The primary teams requested a biopsy 38 times to assist in diagnosis, as documented in the progress note or consultation request. Only 21 of these consultations (55% of requests) received at least 1 biopsy, as the remaining consultations did not require a biopsy to establish a diagnosis. The most common final diagnoses of consultations receiving biopsies included drug eruptions (5), leukemia cutis (4), vasculopathies (4), vasculitis (4), and calciphylaxis (3).

Impact on Hospitalization and Efficacy—Dermatology performed 217 consultations regarding patients already admitted to the hospital, and 92% remained hospitalized either due to comorbidities or complicated cutaneous conditions following the consultation. The remaining 8% were cleared for discharge. Dermatology received 36 consultation requests from emergency medicine physicians. Fifty-three percent of these patients were admitted, while the remaining 47% were discharged from the emergency department or its observation unit following evaluation.

Fifty-one percent of all consultations were noted to have improvement in their cutaneous condition by the time of discharge, as noted in the physical examination, progress note, or discharge summary of the primary team. Thirty percent of cases remained stable, where improvement was not noted in in the medical record. Most of these cases involved keratinocyte carcinomas scheduled for outpatient excision, benign melanocytic nevi found on FBSE, and benign etiologies that led to immediate discharge following consultation. Three percent of all consultations were noted to have worsened following consultation, including cases of calciphylaxis, vasculopathies, and purpura fulminans, as well as patients who elected for palliative care and hospice. The cutaneous condition by the time of discharge could not be determined from the medical record in 16% of all consultations.

Eighty-five percent of all consultations required a single encounter with dermatology. An additional 10% required a single follow-up with dermatology, while only 5% of patients required 3 or more encounters. Notably, these cases included patients with 1 or more severe cutaneous diseases, such as Sweet syndrome, calciphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and hidradenitis suppurativa.

Comment

Although dermatology often is viewed as an outpatient specialty, this study provides a glimpse into the ways inpatient dermatology consultations optimize the care of hospitalized patients. Most consultations involved assistance in diagnosing an unknown condition, but several regarded pre-existing skin disorders requiring management aid. As a variety of medical specialties requested consultations, dermatology was able to provide care to a diverse group of patients with conditions varying in complexity and severity. Several specialties benefited from niche dermatologic expertise: hematology and oncology frequently requested dermatology to assist in diagnosis and management of the toxic effects of chemotherapy, cutaneous metastasis, or suspected cutaneous infections in immunocompromised patients. Cardiology patients were frequently evaluated for potential malignancy or infection prior to heart transplantation and initiation of antirejection immunosuppressants. Dermatology was consulted to differentiate cutaneous manifestations of critical illness from underlying systemic disease in the intensive care unit, and patients presenting to the emergency department often were examined to determine if hospital admission was necessary, with 47% of these consultations resulting in a discharge following evaluation by a dermatologist.

Our results were consistent with prior studies1,5,6 that have reported frequent changes in final diagnosis following dermatology consultation, with 69% of working diagnoses changed in this study when consultation was requested for diagnostic assistance. When dermatology was consulted for diagnostic assistance, several of these cases lacked a preliminary differential diagnosis. Although the absence of a documented differential diagnosis may not necessarily reflect a lack of suspicion for a particular etiology, 86% of all consultations included a ranked differential or working diagnosis either in the consultation request or progress note prior to consultation. The final diagnoses of consultations without a preliminary diagnosis varied from the mild and localized to systemic and severe, further suggesting these cases reflected knowledge gaps of the primary medical team.

Integration of dermatology into the care of hospitalized patients could provide an opportunity for education of primary medical teams. With frequent consultation, primary medical teams may become more comfortable diagnosing and managing common cutaneous conditions specific to their specialty or extended hospitalizations.

Several consultations were requested to aid in management of cases of hidradenitis suppurativa, pyoderma gangrenosum, or bullous pemphigoid that either failed outpatient therapy or were complicated by superinfections. Despite the ranges in complexity, the majority of all consultations required a single encounter and led to improvement by the time of discharge, demonstrating the efficacy and efficiency of inpatient dermatologists.

Dermatology consultations often led to changes in management involving medications and additional workup. Changes in management also extended to specific wound care instructions provided by dermatology, as expected for cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, Sweet syndrome, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pyoderma gangrenosum. However, patients with the sequelae of extended hospitalizations, such as chronic wounds, pressure ulcers, and edema bullae, also benefited from this expertise.

When patients required a biopsy, the final diagnoses were consistent with the dermatologist’s number one differential diagnosis or top 3 differential diagnoses 72% and 88% of the time, respectively. Only 55% of cases where the primary team requested a biopsy ultimately required a biopsy, as many involved clinical diagnoses such as urticaria. Not only was dermatology accurate in their preliminary diagnoses, but they decreased cost and morbidity by avoiding unnecessary procedures.

This study provided additional evidence to support the integration of dermatology into the hospital setting for the benefit of patients, primary medical teams, and hospital systems. Dermatology offers high-value care through the efficient diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients, which contributes to decreased cost and improved outcomes.2,5-7,9,10 This study highlighted lesser-known areas of impact, such as the various specialty-specific services dermatology provides as well as the high rates of reported improvement following consultation. Future studies should continue to explore the field’s unique impact on hospitalized medicine as well as other avenues of care delivery, such as telemedicine, that may encourage dermatologists to participate in consultations and increase the volume of patients who may benefit from their care.

- Madigan LM, Fox LP. Where are we now with inpatient consultative dermatology?: assessing the value and evolution of this subspecialty over the past decade. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1804-1808. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.031

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M. Inpatient dermatologists—crucial for the management of skin diseases in hospitalized patients [editorial]. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:524-525. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6195

- Strowd LC. Inpatient dermatology: a paradigm shift in the management of skin disease in the hospital. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:966-967. doi:10.1111/bjd.17778

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. The changing status of inpatient dermatology at American academic dermatology programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:755-757. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70158-1

- Kroshinsky D, Cotliar J, Hughey LC, et al. Association of dermatology consultation with accuracy of cutaneous disorder diagnoses in hospitalized patients: a multicenter analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:477-480. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5098

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-533. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6130

- Imadojemu S, Rosenbach M. Dermatologists must take an active role in the diagnosis of cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:134-135. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4230

- Hughey LC. The impact dermatologists can have on misdiagnosis of cellulitis and overuse of antibiotics: closing the gap. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1061-1062. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1164

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558. doi:10.1111/ijd.13939

Dermatology is an often-underutilized resource in the hospital setting. As the health care landscape has evolved, so has the role of the inpatient dermatologist.1-3 Structural changes in the health system and advances in therapies have shifted dermatology from an admitting service to an almost exclusively outpatient practice. Improved treatment modalities led to decreases in the number of patients requiring admission for chronic dermatoses, and outpatient clinics began offering therapies once limited to hospitals.1,4 Inpatient dermatology consultations emerged and continue to have profound effects on hospitalized patients regardless of their reason for admission.1-11

Inpatient dermatologists supply knowledge in areas primary medical teams lack, and there is evidence that dermatology consultations improve the quality of care while decreasing cost.2,5-7 Establishing correct diagnoses, preventing exposure to unnecessary medications, and reducing hospitalization duration and readmission rates are a few ways dermatology consultations positively impact hospitalized patients.2,5-7,9,10 This study highlights the role of the dermatologist in the care of hospitalized patients at a large academic medical center in an urban setting and reveals how consultation supports the efficiency and efficacy of other services.

Materials and Methods

Study Design—This single-institution, cross-sectional retrospective study included all hospitalized patients at the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), who received an inpatient dermatology consultation completed by physicians of Jefferson Dermatology Associates between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2019. The institutional review board at Thomas Jefferson University approved this study.

Data Collection—A list of all inpatient dermatology consultations in 2019 was provided by Jefferson Dermatology Associates. Through a retrospective chart review, data regarding the consultations were collected from the electronic medical record (Epic Systems) and recorded into the Research Electronic Data Capture system. Data on patient demographics, the primary medical team, the dermatology evaluation, and the hospital course of the patient were collected.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Dermatology received 253 inpatient consultation requests during this time period; 53% of patients were female and 47% were male, with a mean age of 55 years. Most patients were White (57%), while 34% were Black. Five percent and 4% of patients were Asian and Hispanic or Latino, respectively (Table 1). The mean duration of hospitalization for all patients was 15 days, and the average number of days to discharge following the first encounter with dermatology was 10 days.

Requesting Team and Reason for Consultation—Internal medicine consulted dermatology most frequently (34% of all consultations), followed by emergency medicine (14%) and a variety of other services (Table 1). Most dermatology consultations were placed to assist in achieving a diagnosis of a cutaneous condition (77%), while a minority were to assist in the management of a previously diagnosed disease (22%). A small fraction of consultations (5%) were to complete full-body skin examinations (FBSEs) to rule out infection or malignancy in candidates for organ transplantation, left ventricular assist devices, or certain chemotherapies. One FBSE was conducted to search for a primary tumor in a patient diagnosed with metastatic melanoma.

Most Common Final Diagnoses and Consultation Impact—Table 2 lists the most common final diagnosis categories, as well as the effects of the consultation on diagnosis, management, biopsies, hospitalization, and clinical improvement as documented by the primary medical provider. The most common final diagnoses were inflammatory and autoimmune (39%), such as contact dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis; infectious (23%), such as varicella (primary or zoster) and bacterial furunculosis; drug reactions (20%), such as morbilliform drug eruptions; vascular (8%), such as vasculitis and calciphylaxis; neoplastic (7%), such as keratinocyte carcinomas and leukemia cutis; and other (15%), such as xerosis, keratosis pilaris, and miliaria rubra.

Impact on Diagnosis—Fifty-six percent of all consultations resulted in a change in diagnosis. When dermatology was consulted specifically to assist in the diagnosis of a patient (195 consultations), the working diagnosis of the primary team was changed 69% of the time. Thirty-five of these consultation requests had no preliminary diagnosis, and the primary team listed the working diagnosis as either rash or a morphologic description of the lesion(s). Sixty-three percent of suspected drug eruptions ended with a diagnosis of a form of drug eruption, while 20% of consultations for suspected cellulitis or bacterial infections were confirmed to be cellulitis or soft tissue infections.

Impact on Management—Regardless of the reason for the consultation, most consultations (86%) resulted in a change in management. The remaining 14% consisted of FBSEs with benign findings; cases of cutaneous metastases and leukemia cutis managed by oncology; as well as select cases of purpura fulminans, postfebrile desquamation, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Changes in management included alterations in medications, requests for additional laboratory work or imaging, additional consultation requests, biopsies, or specific wound care instructions. Seventy-five percent of all consultations were given specific medication recommendations by dermatology. Most (61%) were recommended to be given a topical steroid, antibiotic, or both. However, 45% of all consultations were recommended to initiate a systemic medication, most commonly antihistamines, antibiotics, steroids, antivirals, or immunomodulators. Dermatology recommended discontinuing specific medications in 16% of all consultations, with antibiotics being the most frequent culprit (17 antibiotics discontinued), owing to drug eruptions or misdiagnosed infections. Vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were the most frequently discontinued antibiotics.

Dermatology was consulted for assistance in management of previously diagnosed cutaneous conditions 56 times (22% of all consultations), often regarding complicated cases of hidradenitis suppurativa (9 cases), pyoderma gangrenosum (5 cases), bullous pemphigoid (4 cases), or erythroderma (4 cases). Most of these cases required a single dermatology encounter to provide recommendations (71%), and 21% required 1 additional follow-up. Sixty-three percent of patients consulted for management assistance were noted to have improvement in their cutaneous condition by time of discharge, as documented by the primary provider in the medical record.

Twenty-eight percent of all consultations required at least 1 biopsy. Seventy-two percent of all biopsies were consistent with the dermatologist’s working diagnosis or highest-ranked differential diagnosis, and 16% of biopsy results were consistent with the second- or third-ranked diagnosis. The primary teams requested a biopsy 38 times to assist in diagnosis, as documented in the progress note or consultation request. Only 21 of these consultations (55% of requests) received at least 1 biopsy, as the remaining consultations did not require a biopsy to establish a diagnosis. The most common final diagnoses of consultations receiving biopsies included drug eruptions (5), leukemia cutis (4), vasculopathies (4), vasculitis (4), and calciphylaxis (3).

Impact on Hospitalization and Efficacy—Dermatology performed 217 consultations regarding patients already admitted to the hospital, and 92% remained hospitalized either due to comorbidities or complicated cutaneous conditions following the consultation. The remaining 8% were cleared for discharge. Dermatology received 36 consultation requests from emergency medicine physicians. Fifty-three percent of these patients were admitted, while the remaining 47% were discharged from the emergency department or its observation unit following evaluation.

Fifty-one percent of all consultations were noted to have improvement in their cutaneous condition by the time of discharge, as noted in the physical examination, progress note, or discharge summary of the primary team. Thirty percent of cases remained stable, where improvement was not noted in in the medical record. Most of these cases involved keratinocyte carcinomas scheduled for outpatient excision, benign melanocytic nevi found on FBSE, and benign etiologies that led to immediate discharge following consultation. Three percent of all consultations were noted to have worsened following consultation, including cases of calciphylaxis, vasculopathies, and purpura fulminans, as well as patients who elected for palliative care and hospice. The cutaneous condition by the time of discharge could not be determined from the medical record in 16% of all consultations.

Eighty-five percent of all consultations required a single encounter with dermatology. An additional 10% required a single follow-up with dermatology, while only 5% of patients required 3 or more encounters. Notably, these cases included patients with 1 or more severe cutaneous diseases, such as Sweet syndrome, calciphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and hidradenitis suppurativa.

Comment

Although dermatology often is viewed as an outpatient specialty, this study provides a glimpse into the ways inpatient dermatology consultations optimize the care of hospitalized patients. Most consultations involved assistance in diagnosing an unknown condition, but several regarded pre-existing skin disorders requiring management aid. As a variety of medical specialties requested consultations, dermatology was able to provide care to a diverse group of patients with conditions varying in complexity and severity. Several specialties benefited from niche dermatologic expertise: hematology and oncology frequently requested dermatology to assist in diagnosis and management of the toxic effects of chemotherapy, cutaneous metastasis, or suspected cutaneous infections in immunocompromised patients. Cardiology patients were frequently evaluated for potential malignancy or infection prior to heart transplantation and initiation of antirejection immunosuppressants. Dermatology was consulted to differentiate cutaneous manifestations of critical illness from underlying systemic disease in the intensive care unit, and patients presenting to the emergency department often were examined to determine if hospital admission was necessary, with 47% of these consultations resulting in a discharge following evaluation by a dermatologist.

Our results were consistent with prior studies1,5,6 that have reported frequent changes in final diagnosis following dermatology consultation, with 69% of working diagnoses changed in this study when consultation was requested for diagnostic assistance. When dermatology was consulted for diagnostic assistance, several of these cases lacked a preliminary differential diagnosis. Although the absence of a documented differential diagnosis may not necessarily reflect a lack of suspicion for a particular etiology, 86% of all consultations included a ranked differential or working diagnosis either in the consultation request or progress note prior to consultation. The final diagnoses of consultations without a preliminary diagnosis varied from the mild and localized to systemic and severe, further suggesting these cases reflected knowledge gaps of the primary medical team.

Integration of dermatology into the care of hospitalized patients could provide an opportunity for education of primary medical teams. With frequent consultation, primary medical teams may become more comfortable diagnosing and managing common cutaneous conditions specific to their specialty or extended hospitalizations.

Several consultations were requested to aid in management of cases of hidradenitis suppurativa, pyoderma gangrenosum, or bullous pemphigoid that either failed outpatient therapy or were complicated by superinfections. Despite the ranges in complexity, the majority of all consultations required a single encounter and led to improvement by the time of discharge, demonstrating the efficacy and efficiency of inpatient dermatologists.

Dermatology consultations often led to changes in management involving medications and additional workup. Changes in management also extended to specific wound care instructions provided by dermatology, as expected for cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, Sweet syndrome, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pyoderma gangrenosum. However, patients with the sequelae of extended hospitalizations, such as chronic wounds, pressure ulcers, and edema bullae, also benefited from this expertise.

When patients required a biopsy, the final diagnoses were consistent with the dermatologist’s number one differential diagnosis or top 3 differential diagnoses 72% and 88% of the time, respectively. Only 55% of cases where the primary team requested a biopsy ultimately required a biopsy, as many involved clinical diagnoses such as urticaria. Not only was dermatology accurate in their preliminary diagnoses, but they decreased cost and morbidity by avoiding unnecessary procedures.

This study provided additional evidence to support the integration of dermatology into the hospital setting for the benefit of patients, primary medical teams, and hospital systems. Dermatology offers high-value care through the efficient diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients, which contributes to decreased cost and improved outcomes.2,5-7,9,10 This study highlighted lesser-known areas of impact, such as the various specialty-specific services dermatology provides as well as the high rates of reported improvement following consultation. Future studies should continue to explore the field’s unique impact on hospitalized medicine as well as other avenues of care delivery, such as telemedicine, that may encourage dermatologists to participate in consultations and increase the volume of patients who may benefit from their care.

Dermatology is an often-underutilized resource in the hospital setting. As the health care landscape has evolved, so has the role of the inpatient dermatologist.1-3 Structural changes in the health system and advances in therapies have shifted dermatology from an admitting service to an almost exclusively outpatient practice. Improved treatment modalities led to decreases in the number of patients requiring admission for chronic dermatoses, and outpatient clinics began offering therapies once limited to hospitals.1,4 Inpatient dermatology consultations emerged and continue to have profound effects on hospitalized patients regardless of their reason for admission.1-11

Inpatient dermatologists supply knowledge in areas primary medical teams lack, and there is evidence that dermatology consultations improve the quality of care while decreasing cost.2,5-7 Establishing correct diagnoses, preventing exposure to unnecessary medications, and reducing hospitalization duration and readmission rates are a few ways dermatology consultations positively impact hospitalized patients.2,5-7,9,10 This study highlights the role of the dermatologist in the care of hospitalized patients at a large academic medical center in an urban setting and reveals how consultation supports the efficiency and efficacy of other services.

Materials and Methods

Study Design—This single-institution, cross-sectional retrospective study included all hospitalized patients at the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), who received an inpatient dermatology consultation completed by physicians of Jefferson Dermatology Associates between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2019. The institutional review board at Thomas Jefferson University approved this study.

Data Collection—A list of all inpatient dermatology consultations in 2019 was provided by Jefferson Dermatology Associates. Through a retrospective chart review, data regarding the consultations were collected from the electronic medical record (Epic Systems) and recorded into the Research Electronic Data Capture system. Data on patient demographics, the primary medical team, the dermatology evaluation, and the hospital course of the patient were collected.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Dermatology received 253 inpatient consultation requests during this time period; 53% of patients were female and 47% were male, with a mean age of 55 years. Most patients were White (57%), while 34% were Black. Five percent and 4% of patients were Asian and Hispanic or Latino, respectively (Table 1). The mean duration of hospitalization for all patients was 15 days, and the average number of days to discharge following the first encounter with dermatology was 10 days.

Requesting Team and Reason for Consultation—Internal medicine consulted dermatology most frequently (34% of all consultations), followed by emergency medicine (14%) and a variety of other services (Table 1). Most dermatology consultations were placed to assist in achieving a diagnosis of a cutaneous condition (77%), while a minority were to assist in the management of a previously diagnosed disease (22%). A small fraction of consultations (5%) were to complete full-body skin examinations (FBSEs) to rule out infection or malignancy in candidates for organ transplantation, left ventricular assist devices, or certain chemotherapies. One FBSE was conducted to search for a primary tumor in a patient diagnosed with metastatic melanoma.

Most Common Final Diagnoses and Consultation Impact—Table 2 lists the most common final diagnosis categories, as well as the effects of the consultation on diagnosis, management, biopsies, hospitalization, and clinical improvement as documented by the primary medical provider. The most common final diagnoses were inflammatory and autoimmune (39%), such as contact dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis; infectious (23%), such as varicella (primary or zoster) and bacterial furunculosis; drug reactions (20%), such as morbilliform drug eruptions; vascular (8%), such as vasculitis and calciphylaxis; neoplastic (7%), such as keratinocyte carcinomas and leukemia cutis; and other (15%), such as xerosis, keratosis pilaris, and miliaria rubra.

Impact on Diagnosis—Fifty-six percent of all consultations resulted in a change in diagnosis. When dermatology was consulted specifically to assist in the diagnosis of a patient (195 consultations), the working diagnosis of the primary team was changed 69% of the time. Thirty-five of these consultation requests had no preliminary diagnosis, and the primary team listed the working diagnosis as either rash or a morphologic description of the lesion(s). Sixty-three percent of suspected drug eruptions ended with a diagnosis of a form of drug eruption, while 20% of consultations for suspected cellulitis or bacterial infections were confirmed to be cellulitis or soft tissue infections.

Impact on Management—Regardless of the reason for the consultation, most consultations (86%) resulted in a change in management. The remaining 14% consisted of FBSEs with benign findings; cases of cutaneous metastases and leukemia cutis managed by oncology; as well as select cases of purpura fulminans, postfebrile desquamation, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Changes in management included alterations in medications, requests for additional laboratory work or imaging, additional consultation requests, biopsies, or specific wound care instructions. Seventy-five percent of all consultations were given specific medication recommendations by dermatology. Most (61%) were recommended to be given a topical steroid, antibiotic, or both. However, 45% of all consultations were recommended to initiate a systemic medication, most commonly antihistamines, antibiotics, steroids, antivirals, or immunomodulators. Dermatology recommended discontinuing specific medications in 16% of all consultations, with antibiotics being the most frequent culprit (17 antibiotics discontinued), owing to drug eruptions or misdiagnosed infections. Vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were the most frequently discontinued antibiotics.

Dermatology was consulted for assistance in management of previously diagnosed cutaneous conditions 56 times (22% of all consultations), often regarding complicated cases of hidradenitis suppurativa (9 cases), pyoderma gangrenosum (5 cases), bullous pemphigoid (4 cases), or erythroderma (4 cases). Most of these cases required a single dermatology encounter to provide recommendations (71%), and 21% required 1 additional follow-up. Sixty-three percent of patients consulted for management assistance were noted to have improvement in their cutaneous condition by time of discharge, as documented by the primary provider in the medical record.

Twenty-eight percent of all consultations required at least 1 biopsy. Seventy-two percent of all biopsies were consistent with the dermatologist’s working diagnosis or highest-ranked differential diagnosis, and 16% of biopsy results were consistent with the second- or third-ranked diagnosis. The primary teams requested a biopsy 38 times to assist in diagnosis, as documented in the progress note or consultation request. Only 21 of these consultations (55% of requests) received at least 1 biopsy, as the remaining consultations did not require a biopsy to establish a diagnosis. The most common final diagnoses of consultations receiving biopsies included drug eruptions (5), leukemia cutis (4), vasculopathies (4), vasculitis (4), and calciphylaxis (3).

Impact on Hospitalization and Efficacy—Dermatology performed 217 consultations regarding patients already admitted to the hospital, and 92% remained hospitalized either due to comorbidities or complicated cutaneous conditions following the consultation. The remaining 8% were cleared for discharge. Dermatology received 36 consultation requests from emergency medicine physicians. Fifty-three percent of these patients were admitted, while the remaining 47% were discharged from the emergency department or its observation unit following evaluation.

Fifty-one percent of all consultations were noted to have improvement in their cutaneous condition by the time of discharge, as noted in the physical examination, progress note, or discharge summary of the primary team. Thirty percent of cases remained stable, where improvement was not noted in in the medical record. Most of these cases involved keratinocyte carcinomas scheduled for outpatient excision, benign melanocytic nevi found on FBSE, and benign etiologies that led to immediate discharge following consultation. Three percent of all consultations were noted to have worsened following consultation, including cases of calciphylaxis, vasculopathies, and purpura fulminans, as well as patients who elected for palliative care and hospice. The cutaneous condition by the time of discharge could not be determined from the medical record in 16% of all consultations.

Eighty-five percent of all consultations required a single encounter with dermatology. An additional 10% required a single follow-up with dermatology, while only 5% of patients required 3 or more encounters. Notably, these cases included patients with 1 or more severe cutaneous diseases, such as Sweet syndrome, calciphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and hidradenitis suppurativa.

Comment

Although dermatology often is viewed as an outpatient specialty, this study provides a glimpse into the ways inpatient dermatology consultations optimize the care of hospitalized patients. Most consultations involved assistance in diagnosing an unknown condition, but several regarded pre-existing skin disorders requiring management aid. As a variety of medical specialties requested consultations, dermatology was able to provide care to a diverse group of patients with conditions varying in complexity and severity. Several specialties benefited from niche dermatologic expertise: hematology and oncology frequently requested dermatology to assist in diagnosis and management of the toxic effects of chemotherapy, cutaneous metastasis, or suspected cutaneous infections in immunocompromised patients. Cardiology patients were frequently evaluated for potential malignancy or infection prior to heart transplantation and initiation of antirejection immunosuppressants. Dermatology was consulted to differentiate cutaneous manifestations of critical illness from underlying systemic disease in the intensive care unit, and patients presenting to the emergency department often were examined to determine if hospital admission was necessary, with 47% of these consultations resulting in a discharge following evaluation by a dermatologist.

Our results were consistent with prior studies1,5,6 that have reported frequent changes in final diagnosis following dermatology consultation, with 69% of working diagnoses changed in this study when consultation was requested for diagnostic assistance. When dermatology was consulted for diagnostic assistance, several of these cases lacked a preliminary differential diagnosis. Although the absence of a documented differential diagnosis may not necessarily reflect a lack of suspicion for a particular etiology, 86% of all consultations included a ranked differential or working diagnosis either in the consultation request or progress note prior to consultation. The final diagnoses of consultations without a preliminary diagnosis varied from the mild and localized to systemic and severe, further suggesting these cases reflected knowledge gaps of the primary medical team.

Integration of dermatology into the care of hospitalized patients could provide an opportunity for education of primary medical teams. With frequent consultation, primary medical teams may become more comfortable diagnosing and managing common cutaneous conditions specific to their specialty or extended hospitalizations.

Several consultations were requested to aid in management of cases of hidradenitis suppurativa, pyoderma gangrenosum, or bullous pemphigoid that either failed outpatient therapy or were complicated by superinfections. Despite the ranges in complexity, the majority of all consultations required a single encounter and led to improvement by the time of discharge, demonstrating the efficacy and efficiency of inpatient dermatologists.

Dermatology consultations often led to changes in management involving medications and additional workup. Changes in management also extended to specific wound care instructions provided by dermatology, as expected for cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, Sweet syndrome, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pyoderma gangrenosum. However, patients with the sequelae of extended hospitalizations, such as chronic wounds, pressure ulcers, and edema bullae, also benefited from this expertise.

When patients required a biopsy, the final diagnoses were consistent with the dermatologist’s number one differential diagnosis or top 3 differential diagnoses 72% and 88% of the time, respectively. Only 55% of cases where the primary team requested a biopsy ultimately required a biopsy, as many involved clinical diagnoses such as urticaria. Not only was dermatology accurate in their preliminary diagnoses, but they decreased cost and morbidity by avoiding unnecessary procedures.

This study provided additional evidence to support the integration of dermatology into the hospital setting for the benefit of patients, primary medical teams, and hospital systems. Dermatology offers high-value care through the efficient diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients, which contributes to decreased cost and improved outcomes.2,5-7,9,10 This study highlighted lesser-known areas of impact, such as the various specialty-specific services dermatology provides as well as the high rates of reported improvement following consultation. Future studies should continue to explore the field’s unique impact on hospitalized medicine as well as other avenues of care delivery, such as telemedicine, that may encourage dermatologists to participate in consultations and increase the volume of patients who may benefit from their care.

- Madigan LM, Fox LP. Where are we now with inpatient consultative dermatology?: assessing the value and evolution of this subspecialty over the past decade. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1804-1808. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.031

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M. Inpatient dermatologists—crucial for the management of skin diseases in hospitalized patients [editorial]. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:524-525. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6195

- Strowd LC. Inpatient dermatology: a paradigm shift in the management of skin disease in the hospital. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:966-967. doi:10.1111/bjd.17778

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. The changing status of inpatient dermatology at American academic dermatology programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:755-757. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70158-1

- Kroshinsky D, Cotliar J, Hughey LC, et al. Association of dermatology consultation with accuracy of cutaneous disorder diagnoses in hospitalized patients: a multicenter analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:477-480. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5098

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-533. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6130

- Imadojemu S, Rosenbach M. Dermatologists must take an active role in the diagnosis of cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:134-135. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4230

- Hughey LC. The impact dermatologists can have on misdiagnosis of cellulitis and overuse of antibiotics: closing the gap. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1061-1062. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1164

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558. doi:10.1111/ijd.13939

- Madigan LM, Fox LP. Where are we now with inpatient consultative dermatology?: assessing the value and evolution of this subspecialty over the past decade. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1804-1808. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.031

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M. Inpatient dermatologists—crucial for the management of skin diseases in hospitalized patients [editorial]. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:524-525. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6195

- Strowd LC. Inpatient dermatology: a paradigm shift in the management of skin disease in the hospital. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:966-967. doi:10.1111/bjd.17778

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. The changing status of inpatient dermatology at American academic dermatology programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:755-757. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70158-1

- Kroshinsky D, Cotliar J, Hughey LC, et al. Association of dermatology consultation with accuracy of cutaneous disorder diagnoses in hospitalized patients: a multicenter analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:477-480. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5098

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-533. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6130

- Imadojemu S, Rosenbach M. Dermatologists must take an active role in the diagnosis of cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:134-135. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4230

- Hughey LC. The impact dermatologists can have on misdiagnosis of cellulitis and overuse of antibiotics: closing the gap. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1061-1062. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1164

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558. doi:10.1111/ijd.13939

Practice Points

- Inpatient dermatologists fill knowledge gaps that often alter the diagnosis, management, and hospital course of hospitalized patients.

- Several medical specialties benefit from niche expertise of inpatient dermatologists specific to their patient population.

- Integration of inpatient dermatology consultations can prevent unnecessary hospital admissions and medication administration.

Children and COVID: Decline of summer surge continues

The continuing decline in COVID-19 incidence suggests the latest surge has peaked as new cases in children dropped for the 4th consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, show an uptick in new cases in late September, largely among younger children, that may indicate otherwise. Those data have a potential 2-week reporting delay, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker, so the most recent points on the graph (see above) could still go up.

. Those new cases made up almost 27% of all cases for the week, and the nearly 5.9 million child cases that have been reported since the start of the pandemic represent 16.2% of cases among Americans of all ages, the two groups said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The CDC data on new cases by age group suggest that younger children have borne a heavier burden in the summer surge of COVID than they did last winter. The rate of new cases was not as high for 16- and 17-year-olds in the summer, but the other age groups all reached higher peaks than in the winter, including the 12- to 15-year-olds, who have been getting vaccinated since May, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

With vaccination approval getting closer for children under age 12 years, initiation in those already eligible continues to slide. Those aged 12-15 made up just 6.9% of new vaccinations during the 2 weeks from Sept. 21 to Oct. 4, and that figure has been dropping since July 13-26, when it was 14.1%. Vaccine initiation among 16- and 17-year-olds over that time has dropped by almost half, from 5.4% to 2.9%, the CDC data show.

All the vaccinations so far add up to this: Almost 55% of those aged 12-15 have gotten at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have over 62% of those aged 16-17, and 52% of the older group is fully vaccinated, as is 44% of the younger group. Altogether, 10.8 million children were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 4, including those under 12 who may be participating in clinical trials or had a birth date entered incorrectly, the CDC said.

The continuing decline in COVID-19 incidence suggests the latest surge has peaked as new cases in children dropped for the 4th consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, show an uptick in new cases in late September, largely among younger children, that may indicate otherwise. Those data have a potential 2-week reporting delay, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker, so the most recent points on the graph (see above) could still go up.

. Those new cases made up almost 27% of all cases for the week, and the nearly 5.9 million child cases that have been reported since the start of the pandemic represent 16.2% of cases among Americans of all ages, the two groups said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The CDC data on new cases by age group suggest that younger children have borne a heavier burden in the summer surge of COVID than they did last winter. The rate of new cases was not as high for 16- and 17-year-olds in the summer, but the other age groups all reached higher peaks than in the winter, including the 12- to 15-year-olds, who have been getting vaccinated since May, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

With vaccination approval getting closer for children under age 12 years, initiation in those already eligible continues to slide. Those aged 12-15 made up just 6.9% of new vaccinations during the 2 weeks from Sept. 21 to Oct. 4, and that figure has been dropping since July 13-26, when it was 14.1%. Vaccine initiation among 16- and 17-year-olds over that time has dropped by almost half, from 5.4% to 2.9%, the CDC data show.

All the vaccinations so far add up to this: Almost 55% of those aged 12-15 have gotten at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have over 62% of those aged 16-17, and 52% of the older group is fully vaccinated, as is 44% of the younger group. Altogether, 10.8 million children were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 4, including those under 12 who may be participating in clinical trials or had a birth date entered incorrectly, the CDC said.

The continuing decline in COVID-19 incidence suggests the latest surge has peaked as new cases in children dropped for the 4th consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, show an uptick in new cases in late September, largely among younger children, that may indicate otherwise. Those data have a potential 2-week reporting delay, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker, so the most recent points on the graph (see above) could still go up.

. Those new cases made up almost 27% of all cases for the week, and the nearly 5.9 million child cases that have been reported since the start of the pandemic represent 16.2% of cases among Americans of all ages, the two groups said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The CDC data on new cases by age group suggest that younger children have borne a heavier burden in the summer surge of COVID than they did last winter. The rate of new cases was not as high for 16- and 17-year-olds in the summer, but the other age groups all reached higher peaks than in the winter, including the 12- to 15-year-olds, who have been getting vaccinated since May, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

With vaccination approval getting closer for children under age 12 years, initiation in those already eligible continues to slide. Those aged 12-15 made up just 6.9% of new vaccinations during the 2 weeks from Sept. 21 to Oct. 4, and that figure has been dropping since July 13-26, when it was 14.1%. Vaccine initiation among 16- and 17-year-olds over that time has dropped by almost half, from 5.4% to 2.9%, the CDC data show.

All the vaccinations so far add up to this: Almost 55% of those aged 12-15 have gotten at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have over 62% of those aged 16-17, and 52% of the older group is fully vaccinated, as is 44% of the younger group. Altogether, 10.8 million children were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 4, including those under 12 who may be participating in clinical trials or had a birth date entered incorrectly, the CDC said.

COVID-19: Two more cases of mucosal skin ulcers reported in male teens

Irish A similar case in an adolescent, also with ulcers affecting the mouth and penis, was reported earlier in 2021 in the United States.

“Our cases show that a swab for COVID-19 can be added to the list of investigations for mucosal and cutaneous rashes in children and probably adults,” said dermatologist Stephanie Bowe, MD, of South Infirmary-Victoria University Hospital in Cork, Ireland, in an interview. “Our patients seemed to improve with IV steroids, but there is not enough data to recommend them to all patients or for use in the different cutaneous presentations associated with COVID-19.”

The new case reports were presented at the 2021 meeting of the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology and published in Pediatric Dermatology.

Researchers have noted that skin disorders linked to COVID-19 infection are different than those in adults. In children, the conditions include morbilliform rash, pernio-like acral lesions, urticaria, macular erythema, vesicular eruption, papulosquamous eruption, and retiform purpura. “The pathogenesis of each is not fully understood but likely related to the inflammatory response to COVID-19 and the various pathways within the body, which become activated,” Dr. Bowe said.

The first patient, a 17-year-old boy, presented at clinic 6 days after he’d been confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 and 8 days after developing fever and cough. “He had a 2-day history of conjunctivitis and ulceration of his oral mucosa, erythematous circumferential erosions of the glans penis with no other cutaneous findings,” the authors write in the report.

The boy “was distressed and embarrassed about his genital ulceration and also found eating very painful due to his oral ulceration,” Dr. Bowe said.

The second patient, a 14-year-old boy, was hospitalized 7 days after a positive COVID-19 test and 9 days after developing cough and fever. “He had a 5-day history of ulceration of the oral mucosa with mild conjunctivitis,” the authors wrote. “Ulceration of the glans penis developed on day 2 of admission.”

The 14-year-old was sicker than the 17-year-old boy, Dr. Bowe said. “He was unable to tolerate an oral diet for several days and had exquisite pain and vomiting with his coughing fits.”

This patient had a history of recurrent herpes labialis, but it’s unclear whether herpes simplex virus (HSV) played a role in the COVID-19–related case. “There is a possibility that the patient was more susceptible to viral cutaneous reactions during COVID-19 infection, but we didn’t have any definite history of HSV infection at the time of mucositis,” Dr. Bowe said. “We also didn’t have any swabs positive for HSV even though several were done at the time.”

Both patients received IV steroids – hydrocortisone at 100 mg 3 times daily for 3 days. This treatment was used “because of deterioration in symptoms and COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Bowe said. “IV steroids were used for respiratory symptoms of COVID-19, so we felt these cutaneous symptoms may have also been caused by an inflammatory response and might benefit from steroids. There was very little literature about this specific situation, though.”

She added that intravenous steroids wouldn’t be appropriate for most pediatric patients, and noted that “their use is controversial in the literature for erythema multiforme and RIME.”

In addition, the patients received betamethasone valerate 0.1% ointment once daily, hydrocortisone 2.5 mg buccal tablets 4 times daily, analgesia with acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and intravenous hydration. The first patient also received prednisolone 1% eye drops, while the second patient was given lidocaine hydrochloride mouthwash and total parenteral nutrition for 5 days.

The patients were discharged after 4 and 14 days, respectively.

Dermatologists in Massachusetts reported a similar case earlier in 2021 in a 17-year-old boy who was positive for COVID-19 and presented with “shallow erosions of the vermilion lips and hard palate, circumferential erythematous erosions of the periurethral glans penis, and five small vesicles on the trunk and upper extremities.”

The patient received betamethasone valerate 0.1% ointment for the lips and penis, intraoral dexamethasone solution, viscous lidocaine, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen. He also received oral prednisone at approximately 1 mg/kg daily for 4 consecutive days after worsening oral pain. A recurrence of oral pain 3 months later was resolved with a higher and longer treatment with oral prednisone.

Dermatologists have also reported cases of erythema multiforme lesions of the mucosa in adults with COVID-19. One case was reported in Iran, and the other in France.

The authors report no study funding and disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Irish A similar case in an adolescent, also with ulcers affecting the mouth and penis, was reported earlier in 2021 in the United States.

“Our cases show that a swab for COVID-19 can be added to the list of investigations for mucosal and cutaneous rashes in children and probably adults,” said dermatologist Stephanie Bowe, MD, of South Infirmary-Victoria University Hospital in Cork, Ireland, in an interview. “Our patients seemed to improve with IV steroids, but there is not enough data to recommend them to all patients or for use in the different cutaneous presentations associated with COVID-19.”

The new case reports were presented at the 2021 meeting of the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology and published in Pediatric Dermatology.

Researchers have noted that skin disorders linked to COVID-19 infection are different than those in adults. In children, the conditions include morbilliform rash, pernio-like acral lesions, urticaria, macular erythema, vesicular eruption, papulosquamous eruption, and retiform purpura. “The pathogenesis of each is not fully understood but likely related to the inflammatory response to COVID-19 and the various pathways within the body, which become activated,” Dr. Bowe said.

The first patient, a 17-year-old boy, presented at clinic 6 days after he’d been confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 and 8 days after developing fever and cough. “He had a 2-day history of conjunctivitis and ulceration of his oral mucosa, erythematous circumferential erosions of the glans penis with no other cutaneous findings,” the authors write in the report.

The boy “was distressed and embarrassed about his genital ulceration and also found eating very painful due to his oral ulceration,” Dr. Bowe said.

The second patient, a 14-year-old boy, was hospitalized 7 days after a positive COVID-19 test and 9 days after developing cough and fever. “He had a 5-day history of ulceration of the oral mucosa with mild conjunctivitis,” the authors wrote. “Ulceration of the glans penis developed on day 2 of admission.”

The 14-year-old was sicker than the 17-year-old boy, Dr. Bowe said. “He was unable to tolerate an oral diet for several days and had exquisite pain and vomiting with his coughing fits.”