User login

Vaccine hope now for leading cause of U.S. infant hospitalizations: RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of U.S. infant hospitalizations overall and across population subgroups, new data published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases confirm.

Acute bronchiolitis caused by RSV accounted for 9.6% (95% confidence interval, 9.4%-9.9%) and 9.3% (95% CI, 9.0%-9.6%) of total infant hospitalizations from January 2009 to September 2015 and October 2015 to December 2019, respectively.

Journal issue includes 14 RSV studies

The latest issue of the journal includes a special section with results from 14 studies related to the widespread, easy-to-catch virus, highlighting the urgency of finding a solution for all infants.

In one study, authors led by Mina Suh, MPH, with EpidStrategies, a division of ToxStrategies in Rockville, Md., reported that, in children under the age of 5 years in the United States, RSV caused 58,000 annual hospitalizations and from 100 to 500 annual deaths from 2009 to 2019 (the latest year data were available).

Globally, in 2015, among infants younger than 6 months, an estimated 1.4 million hospital admissions and 27,300 in-hospital deaths were attributed to RSV lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI).

The researchers used the largest publicly available, all-payer database in the United States – the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample – to describe the leading causes of infant hospitalizations.

The authors noted that, because clinicians don’t routinely perform lab tests for RSV, the true health care burden is likely higher and its public health impact greater than these numbers show.

Immunization candidates advance

There are no preventative options currently available to substantially cut RSV infections in all infants, though immunization candidates are advancing, showing safety and efficacy in clinical trials.

Palivizumab is currently the only available option in the United States to prevent RSV and is recommended only for a small group of infants with particular forms of heart or lung disease and those born prematurely at 29 weeks’ gestational age. Further, palivizumab has to be given monthly throughout the RSV season.

Another of the studies in the journal supplement concluded that a universal immunization strategy with one of the candidates, nirsevimab (Sanofi, AstraZeneca), an investigational long-acting monoclonal antibody, could substantially reduce the health burden and economic burden for U.S. infants in their first RSV season.

The researchers, led by Alexia Kieffer, MSc, MPH, with Sanofi, used static decision-analytic modeling for the estimates. Modeled RSV-related outcomes included primary care and ED visits, hospitalizations, including ICU admission and mechanical ventilations, and RSV-related deaths.

“The results of this model suggested that the use of nirsevimab in all infants could reduce health events by 55% and the overall costs to the payer by 49%,” the authors of the study wrote.

According to the study, universal immunization of all infants with nirsevimab is expected to reduce 290,174 RSV-related medically attended LRTI (MALRTI), 24,986 hospitalizations, and cut $612 million in costs to the health care system.

The authors wrote: “While this reduction would be driven by term infants, who account for most of the RSV-MALRTI burden; all infants, including palivizumab-eligible and preterm infants who suffer from significantly higher rates of disease, would benefit from this immunization strategy.”

Excitement for another option

Jörn-Hendrik Weitkamp, MD, professor of pediatrics and director for patient-oriented research at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview there is much excitement in the field for nirsevimab as it has significant advantages over palivizumab.

RSV “is a huge burden to the children, the families, the hospitals, and the medical system,” he said.

Ideally there would be a vaccine to offer the best protection, he noted.

“People have spent their lives, their careers trying to develop a vaccine for RSV,” he said, but that has been elusive for more than 60 years. Therefore, passive immunization is the best of the current options, he says, and nirsevimab “seems to be very effective.”

What’s not clear, Dr. Weitkamp said, is how much nirsevimab will cost as it is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration. However, it has the great advantage of being given only once before the season starts instead of monthly (as required for palivizumab) through the season, “which is painful, inconvenient, and traumatizing. We limit that one to the children at highest risk.”

Rolling out an infant nirsevimab program would likely vary by geographic region, Ms. Kieffer and colleagues said, to help ensure infants are protected during the peak of their region’s RSV season.

The journal’s RSV supplement was supported by Sanofi and AstraZeneca. The studies by Ms. Suh and colleagues and Ms. Kieffer and colleagues were supported by AstraZeneca and Sanofi. Ms. Suh and several coauthors are employees of EpidStrategies. One coauthor is an employee of Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. Ms. Kieffer and several coauthors are employees of Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. Dr. Weitkamp reported no relevant financial relationships.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of U.S. infant hospitalizations overall and across population subgroups, new data published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases confirm.

Acute bronchiolitis caused by RSV accounted for 9.6% (95% confidence interval, 9.4%-9.9%) and 9.3% (95% CI, 9.0%-9.6%) of total infant hospitalizations from January 2009 to September 2015 and October 2015 to December 2019, respectively.

Journal issue includes 14 RSV studies

The latest issue of the journal includes a special section with results from 14 studies related to the widespread, easy-to-catch virus, highlighting the urgency of finding a solution for all infants.

In one study, authors led by Mina Suh, MPH, with EpidStrategies, a division of ToxStrategies in Rockville, Md., reported that, in children under the age of 5 years in the United States, RSV caused 58,000 annual hospitalizations and from 100 to 500 annual deaths from 2009 to 2019 (the latest year data were available).

Globally, in 2015, among infants younger than 6 months, an estimated 1.4 million hospital admissions and 27,300 in-hospital deaths were attributed to RSV lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI).

The researchers used the largest publicly available, all-payer database in the United States – the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample – to describe the leading causes of infant hospitalizations.

The authors noted that, because clinicians don’t routinely perform lab tests for RSV, the true health care burden is likely higher and its public health impact greater than these numbers show.

Immunization candidates advance

There are no preventative options currently available to substantially cut RSV infections in all infants, though immunization candidates are advancing, showing safety and efficacy in clinical trials.

Palivizumab is currently the only available option in the United States to prevent RSV and is recommended only for a small group of infants with particular forms of heart or lung disease and those born prematurely at 29 weeks’ gestational age. Further, palivizumab has to be given monthly throughout the RSV season.

Another of the studies in the journal supplement concluded that a universal immunization strategy with one of the candidates, nirsevimab (Sanofi, AstraZeneca), an investigational long-acting monoclonal antibody, could substantially reduce the health burden and economic burden for U.S. infants in their first RSV season.

The researchers, led by Alexia Kieffer, MSc, MPH, with Sanofi, used static decision-analytic modeling for the estimates. Modeled RSV-related outcomes included primary care and ED visits, hospitalizations, including ICU admission and mechanical ventilations, and RSV-related deaths.

“The results of this model suggested that the use of nirsevimab in all infants could reduce health events by 55% and the overall costs to the payer by 49%,” the authors of the study wrote.

According to the study, universal immunization of all infants with nirsevimab is expected to reduce 290,174 RSV-related medically attended LRTI (MALRTI), 24,986 hospitalizations, and cut $612 million in costs to the health care system.

The authors wrote: “While this reduction would be driven by term infants, who account for most of the RSV-MALRTI burden; all infants, including palivizumab-eligible and preterm infants who suffer from significantly higher rates of disease, would benefit from this immunization strategy.”

Excitement for another option

Jörn-Hendrik Weitkamp, MD, professor of pediatrics and director for patient-oriented research at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview there is much excitement in the field for nirsevimab as it has significant advantages over palivizumab.

RSV “is a huge burden to the children, the families, the hospitals, and the medical system,” he said.

Ideally there would be a vaccine to offer the best protection, he noted.

“People have spent their lives, their careers trying to develop a vaccine for RSV,” he said, but that has been elusive for more than 60 years. Therefore, passive immunization is the best of the current options, he says, and nirsevimab “seems to be very effective.”

What’s not clear, Dr. Weitkamp said, is how much nirsevimab will cost as it is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration. However, it has the great advantage of being given only once before the season starts instead of monthly (as required for palivizumab) through the season, “which is painful, inconvenient, and traumatizing. We limit that one to the children at highest risk.”

Rolling out an infant nirsevimab program would likely vary by geographic region, Ms. Kieffer and colleagues said, to help ensure infants are protected during the peak of their region’s RSV season.

The journal’s RSV supplement was supported by Sanofi and AstraZeneca. The studies by Ms. Suh and colleagues and Ms. Kieffer and colleagues were supported by AstraZeneca and Sanofi. Ms. Suh and several coauthors are employees of EpidStrategies. One coauthor is an employee of Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. Ms. Kieffer and several coauthors are employees of Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. Dr. Weitkamp reported no relevant financial relationships.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of U.S. infant hospitalizations overall and across population subgroups, new data published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases confirm.

Acute bronchiolitis caused by RSV accounted for 9.6% (95% confidence interval, 9.4%-9.9%) and 9.3% (95% CI, 9.0%-9.6%) of total infant hospitalizations from January 2009 to September 2015 and October 2015 to December 2019, respectively.

Journal issue includes 14 RSV studies

The latest issue of the journal includes a special section with results from 14 studies related to the widespread, easy-to-catch virus, highlighting the urgency of finding a solution for all infants.

In one study, authors led by Mina Suh, MPH, with EpidStrategies, a division of ToxStrategies in Rockville, Md., reported that, in children under the age of 5 years in the United States, RSV caused 58,000 annual hospitalizations and from 100 to 500 annual deaths from 2009 to 2019 (the latest year data were available).

Globally, in 2015, among infants younger than 6 months, an estimated 1.4 million hospital admissions and 27,300 in-hospital deaths were attributed to RSV lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI).

The researchers used the largest publicly available, all-payer database in the United States – the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample – to describe the leading causes of infant hospitalizations.

The authors noted that, because clinicians don’t routinely perform lab tests for RSV, the true health care burden is likely higher and its public health impact greater than these numbers show.

Immunization candidates advance

There are no preventative options currently available to substantially cut RSV infections in all infants, though immunization candidates are advancing, showing safety and efficacy in clinical trials.

Palivizumab is currently the only available option in the United States to prevent RSV and is recommended only for a small group of infants with particular forms of heart or lung disease and those born prematurely at 29 weeks’ gestational age. Further, palivizumab has to be given monthly throughout the RSV season.

Another of the studies in the journal supplement concluded that a universal immunization strategy with one of the candidates, nirsevimab (Sanofi, AstraZeneca), an investigational long-acting monoclonal antibody, could substantially reduce the health burden and economic burden for U.S. infants in their first RSV season.

The researchers, led by Alexia Kieffer, MSc, MPH, with Sanofi, used static decision-analytic modeling for the estimates. Modeled RSV-related outcomes included primary care and ED visits, hospitalizations, including ICU admission and mechanical ventilations, and RSV-related deaths.

“The results of this model suggested that the use of nirsevimab in all infants could reduce health events by 55% and the overall costs to the payer by 49%,” the authors of the study wrote.

According to the study, universal immunization of all infants with nirsevimab is expected to reduce 290,174 RSV-related medically attended LRTI (MALRTI), 24,986 hospitalizations, and cut $612 million in costs to the health care system.

The authors wrote: “While this reduction would be driven by term infants, who account for most of the RSV-MALRTI burden; all infants, including palivizumab-eligible and preterm infants who suffer from significantly higher rates of disease, would benefit from this immunization strategy.”

Excitement for another option

Jörn-Hendrik Weitkamp, MD, professor of pediatrics and director for patient-oriented research at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview there is much excitement in the field for nirsevimab as it has significant advantages over palivizumab.

RSV “is a huge burden to the children, the families, the hospitals, and the medical system,” he said.

Ideally there would be a vaccine to offer the best protection, he noted.

“People have spent their lives, their careers trying to develop a vaccine for RSV,” he said, but that has been elusive for more than 60 years. Therefore, passive immunization is the best of the current options, he says, and nirsevimab “seems to be very effective.”

What’s not clear, Dr. Weitkamp said, is how much nirsevimab will cost as it is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration. However, it has the great advantage of being given only once before the season starts instead of monthly (as required for palivizumab) through the season, “which is painful, inconvenient, and traumatizing. We limit that one to the children at highest risk.”

Rolling out an infant nirsevimab program would likely vary by geographic region, Ms. Kieffer and colleagues said, to help ensure infants are protected during the peak of their region’s RSV season.

The journal’s RSV supplement was supported by Sanofi and AstraZeneca. The studies by Ms. Suh and colleagues and Ms. Kieffer and colleagues were supported by AstraZeneca and Sanofi. Ms. Suh and several coauthors are employees of EpidStrategies. One coauthor is an employee of Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. Ms. Kieffer and several coauthors are employees of Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. Dr. Weitkamp reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Langya, a new zoonotic virus, detected in China

Between 2018 and August 2022, These cases were reported in The New England Journal of Medicine. When asked by Nature about this emerging virus that has until now flown under the radar, scientists said that they were not overly concerned because the virus doesn’t seem to spread easily between people nor is it fatal.

Researchers think that the virus is carried by shrews. It might have infected people directly or through an intermediate animal.

First identified in Langya

The authors describe 35 cases of infection with a virus called Langya henipavirus (LayV) since 2018. It is closely related to two other henipaviruses known to infect people – Hendra virus and Nipah virus. The virus was named Langya after the town in Shandong province in China where the first patient identified with the disease was from, explained coauthor Linfa Wang, PhD, a virologist at Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

Langya can cause respiratory symptoms such as fever, cough, and fatigue. Hendra virus and Nipah virus also cause respiratory infections and can be fatal, the article in Nature reports.

Hendra and Nipah

According to the World Health Organization, Nipah virus, which was discovered in 1999, is a new virus responsible for a zoonosis that causes the disease in animals and humans who have had contact with infected animals. Its name comes from the location where it was first identified in Malaysia. Patients may have asymptomatic infection or symptoms such as acute respiratory infection and severe encephalitis. The case fatality rate is between 40% and 75%.

Nipah virus is closely related to another recently discovered (1994) zoonotic virus called Hendra virus, which is named after the Australian city in which it first appeared. On that day in July 2016, 53 cases were identified involving 70 horses. These incidents remained confined to the northeastern coast of Australia.

Nipah virus and Hendra virus belong to the Paramyxoviridae family. “While the members of this group of viruses are only responsible for a few limited outbreaks, the ability of these viruses to infect a wide range of hosts and cause a disease leading to high fatalities in humans has made them a public health concern,” stated the WHO.

Related to measles

The research team identified LayV while monitoring patients at three hospitals in the eastern Chinese provinces of Shandong and Henan between April 2018 and August 2021. Throughout the study period, the researchers found 35 people infected with LayV, mostly farmers, with symptoms ranging from a cough to severe pneumonia. Participants were recruited into the study if they had a fever. The team sequenced the LayV genome from a throat swab taken from the first patient identified with the disease, a 53-year-old woman.

The LayV genome showed that the virus is most closely related to Mojiang henipavirus, which was first isolated in rats in an abandoned mine in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan in 2012. Henipaviruses belong to the Paramyxoviridae family of viruses, which includes measles, mumps, and many respiratory viruses that infect humans. Several other henipaviruses have been discovered in bats, rats, and shrews from Australia to South Korea and China, but only Hendra, Nipah, and now LayV are known to infect people, according to Nature.

Animal origin likely

Because most patients stated in a questionnaire that they had been exposed to an animal during the month preceding the onset of their symptoms, the researchers tested goats, dogs, pigs, and cattle living in the villages of infected patients for antibodies against LayV. They found LayV antibodies in a handful of goats and dogs and identified LayV viral RNA in 27% of the 262 sampled shrews. These findings suggest that the shrew may be a natural reservoir of LayV, passing it between themselves “and somehow infecting people here and there by chance,” Emily Gurley, PhD, MPH, an infectious diseases epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, told Nature.

The researchers did not find strong evidence of LayV spreading between the people included in the study. There were no clusters of cases in the same family, within a short time span, or in close geographical proximity. “Of the 35 cases, not a single one is linked,” said Dr. Wang, which Dr. Gurley considered good news. It should be noted, however ,”that the study did retrospective contact tracing on only 15 family members of nine infected individuals, which makes it difficult to determine how exactly the individuals were exposed,” reported Nature.

Vigilance is needed

Should we be worried about a potential new epidemic? The replies from two experts interviewed by Nature were reassuring. “There is no particular need to worry about this virus, but ongoing surveillance is critical,” said Professor Edward Holmes, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Sydney. Regularly testing people and animals for emerging viruses is important to understand the risk for zoonotic diseases – those that can be transmitted from other animals to humans, he said.

It is still not clear how people were infected in the first place – whether directly from shrews or an intermediate animal, said Dr. Gurley. That’s why a lot of research still needs to be done to work out how the virus is spreading in shrews and how people are getting infected, she added.

Nevertheless, Dr. Gurley finds that large outbreaks of infectious diseases typically take off after a lot of false starts. “If we are actively looking for those sparks, then we are in a much better position to stop or to find something early.” Still, she noted that she didn’t see anything in the data to “cause alarm from a pandemic-threat perspective.”

Though there is not currently any cause for worry of a new pandemic, vigilance is crucial. Professor Holmes says there is an urgent need for a global surveillance system to detect virus spillovers and rapidly communicate those results to avoid more pandemics, such as the one sparked by COVID-19. “These sorts of zoonotic spillover events happen all the time,” he said. “The world needs to wake up.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Between 2018 and August 2022, These cases were reported in The New England Journal of Medicine. When asked by Nature about this emerging virus that has until now flown under the radar, scientists said that they were not overly concerned because the virus doesn’t seem to spread easily between people nor is it fatal.

Researchers think that the virus is carried by shrews. It might have infected people directly or through an intermediate animal.

First identified in Langya

The authors describe 35 cases of infection with a virus called Langya henipavirus (LayV) since 2018. It is closely related to two other henipaviruses known to infect people – Hendra virus and Nipah virus. The virus was named Langya after the town in Shandong province in China where the first patient identified with the disease was from, explained coauthor Linfa Wang, PhD, a virologist at Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

Langya can cause respiratory symptoms such as fever, cough, and fatigue. Hendra virus and Nipah virus also cause respiratory infections and can be fatal, the article in Nature reports.

Hendra and Nipah

According to the World Health Organization, Nipah virus, which was discovered in 1999, is a new virus responsible for a zoonosis that causes the disease in animals and humans who have had contact with infected animals. Its name comes from the location where it was first identified in Malaysia. Patients may have asymptomatic infection or symptoms such as acute respiratory infection and severe encephalitis. The case fatality rate is between 40% and 75%.

Nipah virus is closely related to another recently discovered (1994) zoonotic virus called Hendra virus, which is named after the Australian city in which it first appeared. On that day in July 2016, 53 cases were identified involving 70 horses. These incidents remained confined to the northeastern coast of Australia.

Nipah virus and Hendra virus belong to the Paramyxoviridae family. “While the members of this group of viruses are only responsible for a few limited outbreaks, the ability of these viruses to infect a wide range of hosts and cause a disease leading to high fatalities in humans has made them a public health concern,” stated the WHO.

Related to measles

The research team identified LayV while monitoring patients at three hospitals in the eastern Chinese provinces of Shandong and Henan between April 2018 and August 2021. Throughout the study period, the researchers found 35 people infected with LayV, mostly farmers, with symptoms ranging from a cough to severe pneumonia. Participants were recruited into the study if they had a fever. The team sequenced the LayV genome from a throat swab taken from the first patient identified with the disease, a 53-year-old woman.

The LayV genome showed that the virus is most closely related to Mojiang henipavirus, which was first isolated in rats in an abandoned mine in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan in 2012. Henipaviruses belong to the Paramyxoviridae family of viruses, which includes measles, mumps, and many respiratory viruses that infect humans. Several other henipaviruses have been discovered in bats, rats, and shrews from Australia to South Korea and China, but only Hendra, Nipah, and now LayV are known to infect people, according to Nature.

Animal origin likely

Because most patients stated in a questionnaire that they had been exposed to an animal during the month preceding the onset of their symptoms, the researchers tested goats, dogs, pigs, and cattle living in the villages of infected patients for antibodies against LayV. They found LayV antibodies in a handful of goats and dogs and identified LayV viral RNA in 27% of the 262 sampled shrews. These findings suggest that the shrew may be a natural reservoir of LayV, passing it between themselves “and somehow infecting people here and there by chance,” Emily Gurley, PhD, MPH, an infectious diseases epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, told Nature.

The researchers did not find strong evidence of LayV spreading between the people included in the study. There were no clusters of cases in the same family, within a short time span, or in close geographical proximity. “Of the 35 cases, not a single one is linked,” said Dr. Wang, which Dr. Gurley considered good news. It should be noted, however ,”that the study did retrospective contact tracing on only 15 family members of nine infected individuals, which makes it difficult to determine how exactly the individuals were exposed,” reported Nature.

Vigilance is needed

Should we be worried about a potential new epidemic? The replies from two experts interviewed by Nature were reassuring. “There is no particular need to worry about this virus, but ongoing surveillance is critical,” said Professor Edward Holmes, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Sydney. Regularly testing people and animals for emerging viruses is important to understand the risk for zoonotic diseases – those that can be transmitted from other animals to humans, he said.

It is still not clear how people were infected in the first place – whether directly from shrews or an intermediate animal, said Dr. Gurley. That’s why a lot of research still needs to be done to work out how the virus is spreading in shrews and how people are getting infected, she added.

Nevertheless, Dr. Gurley finds that large outbreaks of infectious diseases typically take off after a lot of false starts. “If we are actively looking for those sparks, then we are in a much better position to stop or to find something early.” Still, she noted that she didn’t see anything in the data to “cause alarm from a pandemic-threat perspective.”

Though there is not currently any cause for worry of a new pandemic, vigilance is crucial. Professor Holmes says there is an urgent need for a global surveillance system to detect virus spillovers and rapidly communicate those results to avoid more pandemics, such as the one sparked by COVID-19. “These sorts of zoonotic spillover events happen all the time,” he said. “The world needs to wake up.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Between 2018 and August 2022, These cases were reported in The New England Journal of Medicine. When asked by Nature about this emerging virus that has until now flown under the radar, scientists said that they were not overly concerned because the virus doesn’t seem to spread easily between people nor is it fatal.

Researchers think that the virus is carried by shrews. It might have infected people directly or through an intermediate animal.

First identified in Langya

The authors describe 35 cases of infection with a virus called Langya henipavirus (LayV) since 2018. It is closely related to two other henipaviruses known to infect people – Hendra virus and Nipah virus. The virus was named Langya after the town in Shandong province in China where the first patient identified with the disease was from, explained coauthor Linfa Wang, PhD, a virologist at Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

Langya can cause respiratory symptoms such as fever, cough, and fatigue. Hendra virus and Nipah virus also cause respiratory infections and can be fatal, the article in Nature reports.

Hendra and Nipah

According to the World Health Organization, Nipah virus, which was discovered in 1999, is a new virus responsible for a zoonosis that causes the disease in animals and humans who have had contact with infected animals. Its name comes from the location where it was first identified in Malaysia. Patients may have asymptomatic infection or symptoms such as acute respiratory infection and severe encephalitis. The case fatality rate is between 40% and 75%.

Nipah virus is closely related to another recently discovered (1994) zoonotic virus called Hendra virus, which is named after the Australian city in which it first appeared. On that day in July 2016, 53 cases were identified involving 70 horses. These incidents remained confined to the northeastern coast of Australia.

Nipah virus and Hendra virus belong to the Paramyxoviridae family. “While the members of this group of viruses are only responsible for a few limited outbreaks, the ability of these viruses to infect a wide range of hosts and cause a disease leading to high fatalities in humans has made them a public health concern,” stated the WHO.

Related to measles

The research team identified LayV while monitoring patients at three hospitals in the eastern Chinese provinces of Shandong and Henan between April 2018 and August 2021. Throughout the study period, the researchers found 35 people infected with LayV, mostly farmers, with symptoms ranging from a cough to severe pneumonia. Participants were recruited into the study if they had a fever. The team sequenced the LayV genome from a throat swab taken from the first patient identified with the disease, a 53-year-old woman.

The LayV genome showed that the virus is most closely related to Mojiang henipavirus, which was first isolated in rats in an abandoned mine in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan in 2012. Henipaviruses belong to the Paramyxoviridae family of viruses, which includes measles, mumps, and many respiratory viruses that infect humans. Several other henipaviruses have been discovered in bats, rats, and shrews from Australia to South Korea and China, but only Hendra, Nipah, and now LayV are known to infect people, according to Nature.

Animal origin likely

Because most patients stated in a questionnaire that they had been exposed to an animal during the month preceding the onset of their symptoms, the researchers tested goats, dogs, pigs, and cattle living in the villages of infected patients for antibodies against LayV. They found LayV antibodies in a handful of goats and dogs and identified LayV viral RNA in 27% of the 262 sampled shrews. These findings suggest that the shrew may be a natural reservoir of LayV, passing it between themselves “and somehow infecting people here and there by chance,” Emily Gurley, PhD, MPH, an infectious diseases epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, told Nature.

The researchers did not find strong evidence of LayV spreading between the people included in the study. There were no clusters of cases in the same family, within a short time span, or in close geographical proximity. “Of the 35 cases, not a single one is linked,” said Dr. Wang, which Dr. Gurley considered good news. It should be noted, however ,”that the study did retrospective contact tracing on only 15 family members of nine infected individuals, which makes it difficult to determine how exactly the individuals were exposed,” reported Nature.

Vigilance is needed

Should we be worried about a potential new epidemic? The replies from two experts interviewed by Nature were reassuring. “There is no particular need to worry about this virus, but ongoing surveillance is critical,” said Professor Edward Holmes, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Sydney. Regularly testing people and animals for emerging viruses is important to understand the risk for zoonotic diseases – those that can be transmitted from other animals to humans, he said.

It is still not clear how people were infected in the first place – whether directly from shrews or an intermediate animal, said Dr. Gurley. That’s why a lot of research still needs to be done to work out how the virus is spreading in shrews and how people are getting infected, she added.

Nevertheless, Dr. Gurley finds that large outbreaks of infectious diseases typically take off after a lot of false starts. “If we are actively looking for those sparks, then we are in a much better position to stop or to find something early.” Still, she noted that she didn’t see anything in the data to “cause alarm from a pandemic-threat perspective.”

Though there is not currently any cause for worry of a new pandemic, vigilance is crucial. Professor Holmes says there is an urgent need for a global surveillance system to detect virus spillovers and rapidly communicate those results to avoid more pandemics, such as the one sparked by COVID-19. “These sorts of zoonotic spillover events happen all the time,” he said. “The world needs to wake up.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Monkeypox in children and women remains rare, CDC data show

Monkeypox cases in the United States continue to be rare in children younger than 15, women, and in individuals older than 60, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Men aged 26-40 make up the highest proportion of cases.

The age distribution of cases is similar to those of sexually transmitted infections, said Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, associate chief of the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. It is most common in younger to middle-aged age groups, and less common in children and older individuals. As of Aug. 21, only 17 children younger than 15 have been diagnosed with monkeypox in the United States, and women make up fewer than 1.5% of cases.

“This data should be very reassuring to parents and to children going to back to school,” Dr. Gandhi said in an interview. After 3 months of monitoring the virus, the data suggest that monkeypox is primarily spreading in networks of men who have sex with men (MSM) through sexual activity, “and that isn’t something we worry about with school-spread illness.”

In addition to the reassuring data about children and monkeypox, the CDC released laboratory testing data, a behavioral survey of MSM, patient data on the antiviral medication tecovirimat (TPOXX), and other case demographics and symptoms.

Though the number of positive monkeypox tests have continued to rise, the test-positivity rates have declined over the past month, data show. Since July 16, the positivity rate has dipped from 54% to 23%. This trend is likely because of an increase in testing availability, said Randolph Hubach, PhD, MPH, the director of the Sexual Health Research Lab at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind.

“We also saw this with COVID early on with testing: it was really limited to folks who were symptomatic,” he said in an interview . “As testing ramped up in accessibility, you had a lot more negative results, but because testing was more widely available, you were able to capture more positive results.”

The data also show that case numbers continue to grow in the United States, whereas in other countries that identified cases before the United States – Spain, the United Kingdom, and France, for example – cases have been leveling off, noted Dr. Gandhi.

The CDC also shared responses from a survey of gay, bisexual, and other MSM conducted from Aug. 5-15, about how they have changed their sexual behaviors in response to the monkeypox outbreak. Half of respondents reported reduced one-time sexual encounters, 49% reported reducing sex with partners met on dating apps or at sex venues, and 48% reported reducing their number of sex partners. These responses are “heartening to see,” Dr. Gandhi said, and shows that individuals are taking proactive steps to reduce their potential exposure risk to monkeypox.

More detailed demographic data showed that Black, Hispanic, or Latinx individuals make up an increasing proportion of cases in the United States. In May, 71% of people with reported monkeypox infection were White and 29% were Black. For the week of August 8-14, about a third (31%) of monkeypox cases were in White people, 32% were in Hispanic or Latinx people, and 33% were in Black people.

The most common symptoms of monkeypox were rash (98.6%), malaise (72.7%), fever (72.1%), and chills (68.9%). Rectal pain was reported in 43.9% of patients, and 25% had rectal bleeding.

The CDC also released information on 288 patients with monkeypox treated with TPOXX under compassionate use. The median age of patients was 37 and 98.9% were male. About 40% of recipients were White, 35% were Hispanic, and about 16% were Black. This information does not include every patient treated with TPOXX, the agency said, as providers can begin treatment before submitting paperwork. As of Aug. 18, the CDC had received 400 patient intake forms for TPOXX, according to its website.

The agency has yet to release data on vaccination rates, which Dr. Hubach is eager to see. Demographic information on who is receiving vaccinations, and where, can illuminate issues with access as vaccine eligibility continues to expand. “Vaccination is probably going to be the largest tool within our toolbox to try to inhibit disease acquisition and spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox cases in the United States continue to be rare in children younger than 15, women, and in individuals older than 60, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Men aged 26-40 make up the highest proportion of cases.

The age distribution of cases is similar to those of sexually transmitted infections, said Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, associate chief of the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. It is most common in younger to middle-aged age groups, and less common in children and older individuals. As of Aug. 21, only 17 children younger than 15 have been diagnosed with monkeypox in the United States, and women make up fewer than 1.5% of cases.

“This data should be very reassuring to parents and to children going to back to school,” Dr. Gandhi said in an interview. After 3 months of monitoring the virus, the data suggest that monkeypox is primarily spreading in networks of men who have sex with men (MSM) through sexual activity, “and that isn’t something we worry about with school-spread illness.”

In addition to the reassuring data about children and monkeypox, the CDC released laboratory testing data, a behavioral survey of MSM, patient data on the antiviral medication tecovirimat (TPOXX), and other case demographics and symptoms.

Though the number of positive monkeypox tests have continued to rise, the test-positivity rates have declined over the past month, data show. Since July 16, the positivity rate has dipped from 54% to 23%. This trend is likely because of an increase in testing availability, said Randolph Hubach, PhD, MPH, the director of the Sexual Health Research Lab at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind.

“We also saw this with COVID early on with testing: it was really limited to folks who were symptomatic,” he said in an interview . “As testing ramped up in accessibility, you had a lot more negative results, but because testing was more widely available, you were able to capture more positive results.”

The data also show that case numbers continue to grow in the United States, whereas in other countries that identified cases before the United States – Spain, the United Kingdom, and France, for example – cases have been leveling off, noted Dr. Gandhi.

The CDC also shared responses from a survey of gay, bisexual, and other MSM conducted from Aug. 5-15, about how they have changed their sexual behaviors in response to the monkeypox outbreak. Half of respondents reported reduced one-time sexual encounters, 49% reported reducing sex with partners met on dating apps or at sex venues, and 48% reported reducing their number of sex partners. These responses are “heartening to see,” Dr. Gandhi said, and shows that individuals are taking proactive steps to reduce their potential exposure risk to monkeypox.

More detailed demographic data showed that Black, Hispanic, or Latinx individuals make up an increasing proportion of cases in the United States. In May, 71% of people with reported monkeypox infection were White and 29% were Black. For the week of August 8-14, about a third (31%) of monkeypox cases were in White people, 32% were in Hispanic or Latinx people, and 33% were in Black people.

The most common symptoms of monkeypox were rash (98.6%), malaise (72.7%), fever (72.1%), and chills (68.9%). Rectal pain was reported in 43.9% of patients, and 25% had rectal bleeding.

The CDC also released information on 288 patients with monkeypox treated with TPOXX under compassionate use. The median age of patients was 37 and 98.9% were male. About 40% of recipients were White, 35% were Hispanic, and about 16% were Black. This information does not include every patient treated with TPOXX, the agency said, as providers can begin treatment before submitting paperwork. As of Aug. 18, the CDC had received 400 patient intake forms for TPOXX, according to its website.

The agency has yet to release data on vaccination rates, which Dr. Hubach is eager to see. Demographic information on who is receiving vaccinations, and where, can illuminate issues with access as vaccine eligibility continues to expand. “Vaccination is probably going to be the largest tool within our toolbox to try to inhibit disease acquisition and spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox cases in the United States continue to be rare in children younger than 15, women, and in individuals older than 60, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Men aged 26-40 make up the highest proportion of cases.

The age distribution of cases is similar to those of sexually transmitted infections, said Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, associate chief of the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. It is most common in younger to middle-aged age groups, and less common in children and older individuals. As of Aug. 21, only 17 children younger than 15 have been diagnosed with monkeypox in the United States, and women make up fewer than 1.5% of cases.

“This data should be very reassuring to parents and to children going to back to school,” Dr. Gandhi said in an interview. After 3 months of monitoring the virus, the data suggest that monkeypox is primarily spreading in networks of men who have sex with men (MSM) through sexual activity, “and that isn’t something we worry about with school-spread illness.”

In addition to the reassuring data about children and monkeypox, the CDC released laboratory testing data, a behavioral survey of MSM, patient data on the antiviral medication tecovirimat (TPOXX), and other case demographics and symptoms.

Though the number of positive monkeypox tests have continued to rise, the test-positivity rates have declined over the past month, data show. Since July 16, the positivity rate has dipped from 54% to 23%. This trend is likely because of an increase in testing availability, said Randolph Hubach, PhD, MPH, the director of the Sexual Health Research Lab at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind.

“We also saw this with COVID early on with testing: it was really limited to folks who were symptomatic,” he said in an interview . “As testing ramped up in accessibility, you had a lot more negative results, but because testing was more widely available, you were able to capture more positive results.”

The data also show that case numbers continue to grow in the United States, whereas in other countries that identified cases before the United States – Spain, the United Kingdom, and France, for example – cases have been leveling off, noted Dr. Gandhi.

The CDC also shared responses from a survey of gay, bisexual, and other MSM conducted from Aug. 5-15, about how they have changed their sexual behaviors in response to the monkeypox outbreak. Half of respondents reported reduced one-time sexual encounters, 49% reported reducing sex with partners met on dating apps or at sex venues, and 48% reported reducing their number of sex partners. These responses are “heartening to see,” Dr. Gandhi said, and shows that individuals are taking proactive steps to reduce their potential exposure risk to monkeypox.

More detailed demographic data showed that Black, Hispanic, or Latinx individuals make up an increasing proportion of cases in the United States. In May, 71% of people with reported monkeypox infection were White and 29% were Black. For the week of August 8-14, about a third (31%) of monkeypox cases were in White people, 32% were in Hispanic or Latinx people, and 33% were in Black people.

The most common symptoms of monkeypox were rash (98.6%), malaise (72.7%), fever (72.1%), and chills (68.9%). Rectal pain was reported in 43.9% of patients, and 25% had rectal bleeding.

The CDC also released information on 288 patients with monkeypox treated with TPOXX under compassionate use. The median age of patients was 37 and 98.9% were male. About 40% of recipients were White, 35% were Hispanic, and about 16% were Black. This information does not include every patient treated with TPOXX, the agency said, as providers can begin treatment before submitting paperwork. As of Aug. 18, the CDC had received 400 patient intake forms for TPOXX, according to its website.

The agency has yet to release data on vaccination rates, which Dr. Hubach is eager to see. Demographic information on who is receiving vaccinations, and where, can illuminate issues with access as vaccine eligibility continues to expand. “Vaccination is probably going to be the largest tool within our toolbox to try to inhibit disease acquisition and spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Preparing for back to school amid monkeypox outbreak and ever-changing COVID landscape

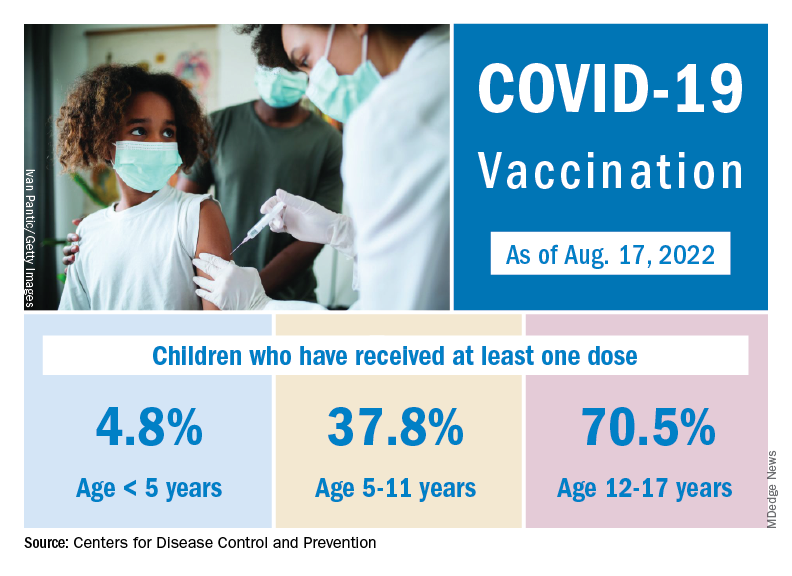

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Pfizer seeks approval for updated COVID booster

Pfizer has sent an application to the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization of its updated COVID-19 booster vaccine for the fall of 2022, the company announced on Aug. 22.

The vaccine, which is adapted for the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron variants, would be meant for ages 12 and older. If authorized by the FDA, the doses could ship as soon as September.

“Having rapidly scaled up production, we are positioned to immediately begin distribution of the bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5 boosters, if authorized, to help protect individuals and families as we prepare for potential fall and winter surges,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the statement.

Earlier this year, the FDA ordered vaccine makers such as Pfizer and Moderna to update their shots to target BA.4 and BA.5, which are better at escaping immunity from earlier vaccines and previous infections.

The United States has a contract to buy 105 million of the Pfizer doses and 66 million of the Moderna doses, according to The Associated Press. Moderna is expected to file its FDA application soon as well.

The new shots target both the original spike protein on the coronavirus and the spike mutations carried by BA.4 and BA.5. For now, BA.5 is causing 89% of new infections in the United States, followed by BA.4.6 with 6.3% and BA.4 with 4.3%, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

There’s no way to tell if BA.5 will still be the dominant strain this winter or if new variant will replace it, the AP reported. But public health officials have supported the updated boosters as a way to target the most recent strains and increase immunity again.

On Aug. 15, Great Britain became the first country to authorize another one of Moderna’s updated vaccines, which adds protection against BA.1, or the original Omicron strain that became dominant in the winter of 2021-2022. European regulators are considering this shot, the AP reported, but the United States opted not to use this version since new Omicron variants have become dominant.

To approve the latest Pfizer shot, the FDA will rely on scientific testing of prior updates to the vaccine, rather than the newest boosters, to decide whether to fast-track the updated shots for fall, the AP reported. This method is like how flu vaccines are updated each year without large studies that take months.

Previously, Pfizer announced results from a study that found the earlier Omicron update significantly boosted antibodies capable of fighting the BA.1 variant and provided some protection against BA.4 and BA.5. The company’s latest FDA application contains that data and animal testing on the newest booster, the AP reported.

Pfizer will start a trial using the BA.4/BA.5 booster in coming weeks to get more data on how well the latest shot works. Moderna has begun a similar study.

The full results from these studies won’t be available before a fall booster campaign, which is why the FDA and public health officials have called for an updated shot to be ready for distribution in September.

“It’s clear that none of these vaccines are going to completely prevent infection,” Rachel Presti, MD, a researcher with the Moderna trial and an infectious diseases specialist at Washington University in St. Louis, told the AP.

But previous studies of variant booster candidates have shown that “you still get a broader immune response giving a variant booster than giving the same booster,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pfizer has sent an application to the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization of its updated COVID-19 booster vaccine for the fall of 2022, the company announced on Aug. 22.

The vaccine, which is adapted for the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron variants, would be meant for ages 12 and older. If authorized by the FDA, the doses could ship as soon as September.

“Having rapidly scaled up production, we are positioned to immediately begin distribution of the bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5 boosters, if authorized, to help protect individuals and families as we prepare for potential fall and winter surges,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the statement.

Earlier this year, the FDA ordered vaccine makers such as Pfizer and Moderna to update their shots to target BA.4 and BA.5, which are better at escaping immunity from earlier vaccines and previous infections.

The United States has a contract to buy 105 million of the Pfizer doses and 66 million of the Moderna doses, according to The Associated Press. Moderna is expected to file its FDA application soon as well.

The new shots target both the original spike protein on the coronavirus and the spike mutations carried by BA.4 and BA.5. For now, BA.5 is causing 89% of new infections in the United States, followed by BA.4.6 with 6.3% and BA.4 with 4.3%, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

There’s no way to tell if BA.5 will still be the dominant strain this winter or if new variant will replace it, the AP reported. But public health officials have supported the updated boosters as a way to target the most recent strains and increase immunity again.

On Aug. 15, Great Britain became the first country to authorize another one of Moderna’s updated vaccines, which adds protection against BA.1, or the original Omicron strain that became dominant in the winter of 2021-2022. European regulators are considering this shot, the AP reported, but the United States opted not to use this version since new Omicron variants have become dominant.

To approve the latest Pfizer shot, the FDA will rely on scientific testing of prior updates to the vaccine, rather than the newest boosters, to decide whether to fast-track the updated shots for fall, the AP reported. This method is like how flu vaccines are updated each year without large studies that take months.

Previously, Pfizer announced results from a study that found the earlier Omicron update significantly boosted antibodies capable of fighting the BA.1 variant and provided some protection against BA.4 and BA.5. The company’s latest FDA application contains that data and animal testing on the newest booster, the AP reported.

Pfizer will start a trial using the BA.4/BA.5 booster in coming weeks to get more data on how well the latest shot works. Moderna has begun a similar study.

The full results from these studies won’t be available before a fall booster campaign, which is why the FDA and public health officials have called for an updated shot to be ready for distribution in September.

“It’s clear that none of these vaccines are going to completely prevent infection,” Rachel Presti, MD, a researcher with the Moderna trial and an infectious diseases specialist at Washington University in St. Louis, told the AP.

But previous studies of variant booster candidates have shown that “you still get a broader immune response giving a variant booster than giving the same booster,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pfizer has sent an application to the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization of its updated COVID-19 booster vaccine for the fall of 2022, the company announced on Aug. 22.

The vaccine, which is adapted for the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron variants, would be meant for ages 12 and older. If authorized by the FDA, the doses could ship as soon as September.

“Having rapidly scaled up production, we are positioned to immediately begin distribution of the bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5 boosters, if authorized, to help protect individuals and families as we prepare for potential fall and winter surges,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the statement.

Earlier this year, the FDA ordered vaccine makers such as Pfizer and Moderna to update their shots to target BA.4 and BA.5, which are better at escaping immunity from earlier vaccines and previous infections.

The United States has a contract to buy 105 million of the Pfizer doses and 66 million of the Moderna doses, according to The Associated Press. Moderna is expected to file its FDA application soon as well.

The new shots target both the original spike protein on the coronavirus and the spike mutations carried by BA.4 and BA.5. For now, BA.5 is causing 89% of new infections in the United States, followed by BA.4.6 with 6.3% and BA.4 with 4.3%, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

There’s no way to tell if BA.5 will still be the dominant strain this winter or if new variant will replace it, the AP reported. But public health officials have supported the updated boosters as a way to target the most recent strains and increase immunity again.

On Aug. 15, Great Britain became the first country to authorize another one of Moderna’s updated vaccines, which adds protection against BA.1, or the original Omicron strain that became dominant in the winter of 2021-2022. European regulators are considering this shot, the AP reported, but the United States opted not to use this version since new Omicron variants have become dominant.

To approve the latest Pfizer shot, the FDA will rely on scientific testing of prior updates to the vaccine, rather than the newest boosters, to decide whether to fast-track the updated shots for fall, the AP reported. This method is like how flu vaccines are updated each year without large studies that take months.

Previously, Pfizer announced results from a study that found the earlier Omicron update significantly boosted antibodies capable of fighting the BA.1 variant and provided some protection against BA.4 and BA.5. The company’s latest FDA application contains that data and animal testing on the newest booster, the AP reported.

Pfizer will start a trial using the BA.4/BA.5 booster in coming weeks to get more data on how well the latest shot works. Moderna has begun a similar study.

The full results from these studies won’t be available before a fall booster campaign, which is why the FDA and public health officials have called for an updated shot to be ready for distribution in September.

“It’s clear that none of these vaccines are going to completely prevent infection,” Rachel Presti, MD, a researcher with the Moderna trial and an infectious diseases specialist at Washington University in St. Louis, told the AP.

But previous studies of variant booster candidates have shown that “you still get a broader immune response giving a variant booster than giving the same booster,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Are we up the creek without a paddle? What COVID, monkeypox, and nature are trying to tell us

Monkeypox. Polio. Covid. A quick glance at the news on any given day seems to indicate that outbreaks, epidemics, and perhaps even pandemics are increasing in frequency.

Granted, these types of events are hardly new; from the plagues of the 5th and 13th centuries to the Spanish flu in the 20th century and SARS-CoV-2 today, they’ve been with us from time immemorial.

What appears to be different, however, is not their frequency, but their intensity, with research reinforcing that we may be facing unique challenges and smaller windows to intervene as we move forward.

Findings from a modeling study, published in 2021 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, underscore that without effective intervention, the probability of extreme events like COVID-19 will likely increase threefold in the coming decades.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“It’s all been based on some unusual cluster of cases that were causing severe disease and overwhelming local authorities. So often, like Indiana Jones, somebody got dispatched to deal with an outbreak,” Dr. Adalja said.

In a perfect post-COVID world, government bodies, scientists, clinicians, and others would cross silos to coordinate pandemic prevention, not just preparedness. The public would trust those who carry the title “public health” in their daily responsibilities, and in turn, public health experts would get back to their core responsibility – infectious disease preparedness – the role they were initially assigned following Europe’s Black Death during the 14th century. Instead, the world finds itself at a crossroads, with emerging and reemerging infectious disease outbreaks that on the surface appear to arise haphazardly but in reality are the result of decades of reaction and containment policies aimed at putting out fires, not addressing their cause.

Dr. Adalja noted that only when the threat of biological weapons became a reality in the mid-2000s was there a realization that economies of scale could be exploited by merging interests and efforts to develop health security medical countermeasures. For example, it encouraged governments to more closely integrate agencies like the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority and infectious disease research organizations and individuals.

Still, while significant strides have been made in certain areas, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has revealed substantial weaknesses remaining in public and private health systems, as well as major gaps in infectious disease preparedness.

The role of spillover events

No matter whom you ask, scientists, public health and conservation experts, and infectious disease clinicians all point to one of the most important threats to human health. As Walt Kelly’s Pogo famously put it, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

“The reason why these outbreaks of novel infectious diseases are increasingly occurring is because of human-driven environmental change, particularly land use, unsafe practices when raising farmed animals, and commercial wildlife markets,” Neil M. Vora, MD, a physician specializing in pandemic prevention at Conservation International and a former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemic intelligence officer, said in an interview.

In fact, more than 60% of emerging infections and diseases are due to these “spillover events” (zoonotic spillover) that occur when pathogens that commonly circulate in wildlife jump over to new, human hosts.

Several examples come to mind.

COVID-19 may have begun as an enzootic virus from two undetermined animals, using the Huanan Seafood Market as a possible intermediate reservoir, according to a July 26 preprint in the journal Science.

Likewise, while the Ebola virus was originally attributed to deforestation efforts to create palm oil (which allowed fruit bat carriers to transfer the virus to humans), recent research suggests that bats dwelling in the walls of human dwellings and hospitals are responsible for the 2018 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

(Incidentally, just this week, a new Ebola case was confirmed in Eastern Congo, and it has been genetically linked to the previous outbreak, despite that outbreak having been declared over in early July.)

“When we clear forests, we create opportunities for humans to live alongside the forest edge and displace wildlife. There’s evidence that shows when [these] biodiverse areas are cleared, specialist species that evolved to live in the forests first start to disappear, whereas generalist species – rodents and bats – continue to survive and are able to carry pathogens that can be passed on to humans,” Dr. Vora explained.

So far, China’s outbreak of the novel Langya henipavirus is believed to have spread (either directly or indirectly) by rodents and shrews, according to reports from public health authorities like the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, which is currently monitoring the situation.

Yet, an overreliance on surveillance and containment only perpetuates what Dr. Vora says are cycles of panic and neglect.

“We saw it with Ebola in 2015, in 2016 to 2017 with Zika, you see it with tuberculosis, with sexually transmitted infections, and with COVID. You have policymakers working on solutions, and once they think that they’ve fixed the problem, they’re going to move on to the next crisis.”

It’s also a question of equity.

Reports detailing the reemergence of monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017 were largely ignored, despite the fact that the United States assisted in diagnosing an early case in an 11-year-old boy. At the time, it was clear that the virus was spreading by human-to-human transmission versus animal-to-human transmission, something that had not been seen previously.

“The current model [is] waiting for pathogens to spill over and then [continuing] to spread signals that rich countries are tolerant of these outbreaks so long as they don’t grow into epidemics or pandemics,” Dr. Vora said.

This model is clearly broken; roughly 5 years after Nigeria reported the resurgence of monkeypox, the United States has more than 14,000 confirmed cases, which represents more than a quarter of the total number of cases reported worldwide.

Public health on the brink

I’s difficult to imagine a future without outbreaks and more pandemics, and if experts are to be believed, we are ill-prepared.

“I think that we are in a situation where this is a major threat, and people have become complacent about it,” said Dr. Adalja, who noted that we should be asking ourselves if the “government is actually in a position to be able to respond in a way that we need them to or is [that response] tied up in bureaucracy and inefficiency?”

COVID-19 should have been seen as a wake-up call, and many of those deaths were preventable. “With monkeypox, they’re faltering; it should have been a layup, not a disaster,” he emphasized.

Ellen Eaton, MD, associate professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, also pointed to the reality that by the time COVID-19 reached North America, the United States had already moved away from the model of the public health department as the epicenter of knowledge, education, awareness, and, ironically, public health.