User login

New Pill Successfully Lowers Lp(a) Levels

Concentrations of Lp(a) cholesterol are genetically determined and remain steady throughout life. Levels of 125 nmol/L or higher promote clotting and inflammation, significantly increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke, aortic stenosis, and peripheral artery disease. This affects about 20% of the population, particularly people of Black African and South Asian descent.

There are currently no approved therapies that lower Lp(a), said study author Stephen Nicholls, MBBS, PhD, director of the Victorian Heart Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Several injectable therapies are currently in clinical trials, but muvalaplin is the only oral option. The new drug lowers Lp(a) levels by disrupting the bond between the two parts of the Lp(a) particle.

The KRAKEN Trial

In the KRAKEN trial, 233 adults from around the world with very high Lp(a) levels (> 175 nmol/L) were randomized either to one of three daily doses of muvalaplin — 10, 60, or 240 mg — or to placebo for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured Lp(a) levels with a standard blood test and with a novel test designed to specifically measure levels of intact Lp(a) particles in the blood. In addition to Lp(a), the standard test detects one of its components, apolipoprotein A particles, that are bound to the drug, which can lead to an underestimation of Lp(a) reductions.

Lp(a) levels were up to 70.0% lower in the muvalaplin group than in the placebo group when measured with the traditional blood test and by up to 85.5% lower when measured with the new test. Approximately 82% of participants achieved an Lp(a) level lower than 125 nmol/L when measured with the traditional blood test, and 97% achieved that level when the new test was used. Patients who received either 60 or 240 mg of muvalaplin had similar reductions in Lp(a) levels, which were greater than the reductions seen in the 10 mg group. The drug was safe and generally well tolerated.

“This is a very reassuring phase 2 result,” Nicholls said when he presented the KRAKEN findings at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2024 in Chicago, which were simultaneously published online in JAMA. “It encourages the ongoing development of this agent.”

Lp(a) levels are not affected by changes in lifestyle or diet or by traditional lipid-lowering treatments like statins, said Erin Michos, MD, a cardiologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, who was not involved in the study.

And high Lp(a) levels confer significant cardiovascular risk even when other risks are reduced. So muvalaplin is “a highly promising approach to treat a previously untreatable disorder,” she explained.

Larger and longer studies, with more diverse patient populations, are needed to confirm the results and to determine whether reducing Lp(a) also improves cardiovascular outcomes, Michos pointed out.

“While muvalaplin appears to be an effective approach to lowering Lp(a) levels, we still need to study whether Lp(a) lowering will result in fewer heart attacks and strokes,” Nicholls added.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Concentrations of Lp(a) cholesterol are genetically determined and remain steady throughout life. Levels of 125 nmol/L or higher promote clotting and inflammation, significantly increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke, aortic stenosis, and peripheral artery disease. This affects about 20% of the population, particularly people of Black African and South Asian descent.

There are currently no approved therapies that lower Lp(a), said study author Stephen Nicholls, MBBS, PhD, director of the Victorian Heart Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Several injectable therapies are currently in clinical trials, but muvalaplin is the only oral option. The new drug lowers Lp(a) levels by disrupting the bond between the two parts of the Lp(a) particle.

The KRAKEN Trial

In the KRAKEN trial, 233 adults from around the world with very high Lp(a) levels (> 175 nmol/L) were randomized either to one of three daily doses of muvalaplin — 10, 60, or 240 mg — or to placebo for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured Lp(a) levels with a standard blood test and with a novel test designed to specifically measure levels of intact Lp(a) particles in the blood. In addition to Lp(a), the standard test detects one of its components, apolipoprotein A particles, that are bound to the drug, which can lead to an underestimation of Lp(a) reductions.

Lp(a) levels were up to 70.0% lower in the muvalaplin group than in the placebo group when measured with the traditional blood test and by up to 85.5% lower when measured with the new test. Approximately 82% of participants achieved an Lp(a) level lower than 125 nmol/L when measured with the traditional blood test, and 97% achieved that level when the new test was used. Patients who received either 60 or 240 mg of muvalaplin had similar reductions in Lp(a) levels, which were greater than the reductions seen in the 10 mg group. The drug was safe and generally well tolerated.

“This is a very reassuring phase 2 result,” Nicholls said when he presented the KRAKEN findings at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2024 in Chicago, which were simultaneously published online in JAMA. “It encourages the ongoing development of this agent.”

Lp(a) levels are not affected by changes in lifestyle or diet or by traditional lipid-lowering treatments like statins, said Erin Michos, MD, a cardiologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, who was not involved in the study.

And high Lp(a) levels confer significant cardiovascular risk even when other risks are reduced. So muvalaplin is “a highly promising approach to treat a previously untreatable disorder,” she explained.

Larger and longer studies, with more diverse patient populations, are needed to confirm the results and to determine whether reducing Lp(a) also improves cardiovascular outcomes, Michos pointed out.

“While muvalaplin appears to be an effective approach to lowering Lp(a) levels, we still need to study whether Lp(a) lowering will result in fewer heart attacks and strokes,” Nicholls added.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Concentrations of Lp(a) cholesterol are genetically determined and remain steady throughout life. Levels of 125 nmol/L or higher promote clotting and inflammation, significantly increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke, aortic stenosis, and peripheral artery disease. This affects about 20% of the population, particularly people of Black African and South Asian descent.

There are currently no approved therapies that lower Lp(a), said study author Stephen Nicholls, MBBS, PhD, director of the Victorian Heart Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Several injectable therapies are currently in clinical trials, but muvalaplin is the only oral option. The new drug lowers Lp(a) levels by disrupting the bond between the two parts of the Lp(a) particle.

The KRAKEN Trial

In the KRAKEN trial, 233 adults from around the world with very high Lp(a) levels (> 175 nmol/L) were randomized either to one of three daily doses of muvalaplin — 10, 60, or 240 mg — or to placebo for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured Lp(a) levels with a standard blood test and with a novel test designed to specifically measure levels of intact Lp(a) particles in the blood. In addition to Lp(a), the standard test detects one of its components, apolipoprotein A particles, that are bound to the drug, which can lead to an underestimation of Lp(a) reductions.

Lp(a) levels were up to 70.0% lower in the muvalaplin group than in the placebo group when measured with the traditional blood test and by up to 85.5% lower when measured with the new test. Approximately 82% of participants achieved an Lp(a) level lower than 125 nmol/L when measured with the traditional blood test, and 97% achieved that level when the new test was used. Patients who received either 60 or 240 mg of muvalaplin had similar reductions in Lp(a) levels, which were greater than the reductions seen in the 10 mg group. The drug was safe and generally well tolerated.

“This is a very reassuring phase 2 result,” Nicholls said when he presented the KRAKEN findings at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2024 in Chicago, which were simultaneously published online in JAMA. “It encourages the ongoing development of this agent.”

Lp(a) levels are not affected by changes in lifestyle or diet or by traditional lipid-lowering treatments like statins, said Erin Michos, MD, a cardiologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, who was not involved in the study.

And high Lp(a) levels confer significant cardiovascular risk even when other risks are reduced. So muvalaplin is “a highly promising approach to treat a previously untreatable disorder,” she explained.

Larger and longer studies, with more diverse patient populations, are needed to confirm the results and to determine whether reducing Lp(a) also improves cardiovascular outcomes, Michos pointed out.

“While muvalaplin appears to be an effective approach to lowering Lp(a) levels, we still need to study whether Lp(a) lowering will result in fewer heart attacks and strokes,” Nicholls added.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

An Epidemiologist’s Guide to Debunking Nutritional Research

You’re invited to a dinner party but you struggle to make small talk. Do not worry; that will invariably crop up over cocktails. Because all journalism has been reduced to listicles, here are four ways to seem clever at dinner parties.

1. The Predinner Cocktails: A Lesson in Reverse Causation

Wine connoisseurs sniff, swirl, and gently swish the wine in their mouths before spitting out and cleansing their palates to better appreciate the subtlety of each vintage. If you’re not an oenophile, no matter. Whenever somebody claims that moderate amounts of alcohol are good for your heart, this is your moment to pounce. Interject yourself in the conversation and tell everybody about reverse causation.

Reverse causation, also known as protopathic bias, involves misinterpreting the directionality of an association. You assume that X leads to Y, when in fact Y leads to X. Temporal paradoxes are useful plot devices in science fiction movies, but they have no place in medical research. In our bland world, cause must precede effect. As such, smoking leads to lung cancer; lung cancer doesn’t make you smoke more.

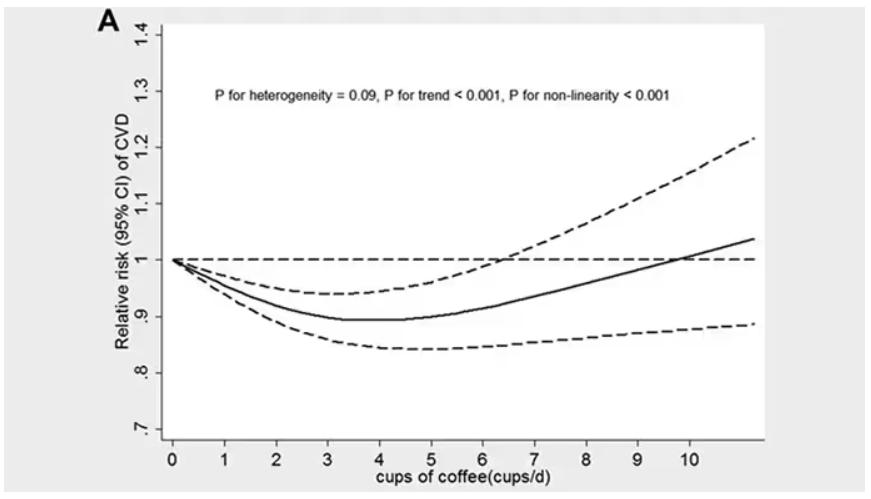

But with alcohol, directionality is less obvious. Many studies of alcohol and cardiovascular disease have demonstrated a U-shaped association, with risk being lowest among those who drink moderate amounts of alcohol (usually one to two drinks per day) and higher in those who drink more and also those who drink very little.

But one must ask why some people drink little or no alcohol. There is an important difference between former drinkers and never drinkers. Former drinkers cut back for a reason. More likely than not, the reason for this newfound sobriety was medical. A new cancer diagnosis, the emergence of atrial fibrillation, the development of diabetes, or rising blood pressure are all good reasons to reduce or eliminate alcohol. A cross-sectional study will fail to capture that alcohol consumption changes over time — people who now don’t drink may have imbibed alcohol in years past. It was not abstinence that led to an increased risk for heart disease; it was the increased risk for heart disease that led to abstinence.

You see the same phenomenon with the so-called obesity paradox. The idea that being a little overweight is good for you may appeal when you no longer fit into last year’s pants. But people who are underweight are so for a reason. Malnutrition, cachexia from cancer, or some other cause is almost certainly driving up the risk at the left-hand side of the U-shaped curve that makes the middle part seem better than it actually is.

Food consumption changes over time. A cross-sectional survey at one point in time cannot accurately capture past habits and distant exposures, especially for diseases such as heart disease and cancer that develop slowly over time. Studies on alcohol that try to overcome these shortcomings by eliminating former drinkers, or by using Mendelian randomization to better account for past exposure, do not show a cardiovascular benefit for moderate red wine drinking.

2. The Hors D’oeuvres — The Importance of RCTs

Now that you have made yourself the center of attention, it is time to cement your newfound reputation as a font of scientific knowledge. Most self-respecting hosts will serve smoked salmon as an amuse-bouche before the main meal. When someone mentions the health benefits of fish oils, you should take the opportunity to teach them about confounding.

Fish, especially cold-water fish from northern climates, have relatively high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids. Despite the plethora of observational studies suggesting a cardiovascular benefit, it’s now relatively clear that fish oil or omega-3 supplements have no medical benefit.

This will probably come as a shock to the worried well, but many studies, including VITAL and ASCEND, have demonstrated no cardiovascular or cancer benefit to supplementation with omega-3s. The reason is straightforward and explains why hormone replacement therapy, vitamin D, and myriad purported game-changers never panned out. Confounding is hard to overcome in observational research.

Prior to the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Study, hormone replacement therapy was routinely prescribed to postmenopausal women because numerous observational studies suggested a cardiovascular benefit. But with the publication of the WHI study, it became clear that much of that “benefit” was due to confounding. The women choosing to take hormones were more health conscious at baseline and healthier overall.

A similar phenomenon occurred during COVID. Patients with low serum vitamin D levels had worse outcomes, prompting many to suggest vitamin D supplementation as a possible treatment. Trials did not support the intervention because we’d overlooked the obvious. People with vitamin D deficiency have underlying health problems that contribute to the vitamin D deficiency. They are probably older, frailer, possibly with a poorer diet. No amount of statistical adjustment can account for all those differences, and some degree of residual confounding will always persist.

The only way to overcome confounding is with randomization. When patients are randomly assigned to one group or another, their baseline differences largely balance out if the randomization was performed properly and the groups were large enough. There is a role for observational research, such as in situations where ethics, cost, and practicality do not allow for a randomized controlled trial. But randomized controlled trials have largely put to rest the purported health benefits of over-the-counter fish oils, omega-3s, and vitamin D.

3. The Main Course — Absolute vs Relative Risk

When you get to the main course, all eyes will now be on you. You will almost certainly be called upon to pronounce on the harms or benefits of red meat consumption. Begin by regaling your guests with a little trivia. Ask them if they know the definition of red meat and white meat. When someone says pork is white meat, you can reveal that “pork, the other white meat,” was a marketing slogan with no scientific underpinning. Now that everyone is lulled into a stupefied silence, tell them that red meat comes from mammals and white meat comes from birds. As they process this revelation, you can now launch into the deeply mathematical concept of absolute vs relative risk.

Many etiquette books will caution against bringing up math at a dinner party. These books are wrong. Everyone finds math interesting if they are primed properly. For example, you can point to a study claiming that berries reduce cardiovascular risk in women. Even if true — and there is reason to be cautious, given the observational nature of the research — we need to understand what the authors meant by a 32% risk reduction. (Side note: It was a reduction in hazard, with a hazard ratio of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.49-0.96), but we won’t dwell on the difference between hazard ratios and risk ratios right now.)

This relative risk reduction has to be interpreted carefully. The authors divided the population into quintiles based on their consumption of anthocyanins (the antioxidant in blueberries and strawberries) and compared the bottom fifth (average consumption, 2.5 mg/d) with the top fifth (average consumption, 25 mg/d). The bottom quintile had 126 myocardial infarctions (MIs) over 324,793 patient-years compared with 59 MIs over 332,143 patient-years. Some quick math shows an approximate reduction from 39 to 18 MIs per 100,000 patient-years. Or to put it another way, you must get 4762 women to increase their berry consumption 10-fold for 1 year to prevent one heart attack. Feel free to show people how you calculated this number. They will be impressed by your head for numbers. It is nothing more than 39 minus 18, divided by 100,000, to get the absolute risk reduction. Take the reciprocal of this (ie, 1 divided by this number) to get the number needed to treat.

Describing risks in absolute terms or using number needed to treat (or harm) can help conceptualize statistics that are sometimes hard to wrap your head around.

4. Dessert — Funding

By the time the coffee is served, everyone will be hanging on to your every word. This is as it should be, and you should not be afraid of your newfound power and influence.

Dessert will probably involve some form of chocolate, possibly in cake format. (Anyone who serves fruit as dessert is not someone you should associate with.) Take the opportunity to tell your follow diners that chocolate is not actually good for you and will not boost brain performance.

The health benefits of chocolate are often repeated but rarely scrutinized. In fact, much of the scientific research purporting to show that chocolate is good for you did not actually study chocolate. It usually involved a cocoa bean extract because the chocolate manufacturing process destroys the supposedly health-promoting antioxidants in the cocoa bean. It is true that dark chocolate has more antioxidants than milk chocolate, and that the addition of milk to chocolate further inactivates the potentially healthy antioxidants. But the amount of sugar and fat that has to be added to chocolate to make it palatable precludes any serious consideration about health benefits. Dark chocolate may have less fat and sugar than milk chocolate, but it still has a lot.

But even the cocoa bean extract doesn’t seem to do much for your heart or your brain. The long-awaited COSMOS study was published with surprisingly little fanfare. The largest randomized controlled trial of chocolate (or rather cocoa bean extract) was supposed to settle the issue definitively.

COSMOS showed no cardiovascular or neurocognitive benefit to the cocoa bean extract. But the health halo of chocolate continues to be bolstered by many studies funded by chocolate manufacturers.

We are appropriately critical of the pharmaceutical industry’s involvement in drug research. However, we should not forget that any private entity is prone to the same self-interest regardless of its product’s tastiness. How many of you knew that there was an avocado lobby funding research? No matter how many industry-funded observational studies using surrogate endpoints are out there telling you that chocolate is healthy, a randomized trial with hard clinical endpoints such as COSMOS should generally win the day.

The Final Goodbyes — Summarizing Your Case

As the party slowly winds down and everyone is saddened that you will soon take your leave, synthesize everything you have taught them over the evening. Like movies, not all studies are good. Some are just bad. They can be prone to reverse causation or confounding, and they may report relative risks when absolute risks would be more telling. Reading research studies critically is essential for separating the wheat from the chaff. With the knowledge you have now imparted to your friends, they will be much better consumers of medical news, especially when it comes to food.

And they will no doubt thank you for it by never inviting you to another dinner party!

Labos, a cardiologist at Hôpital, Notre-Dame, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. He has a degree in epidemiology.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

You’re invited to a dinner party but you struggle to make small talk. Do not worry; that will invariably crop up over cocktails. Because all journalism has been reduced to listicles, here are four ways to seem clever at dinner parties.

1. The Predinner Cocktails: A Lesson in Reverse Causation

Wine connoisseurs sniff, swirl, and gently swish the wine in their mouths before spitting out and cleansing their palates to better appreciate the subtlety of each vintage. If you’re not an oenophile, no matter. Whenever somebody claims that moderate amounts of alcohol are good for your heart, this is your moment to pounce. Interject yourself in the conversation and tell everybody about reverse causation.

Reverse causation, also known as protopathic bias, involves misinterpreting the directionality of an association. You assume that X leads to Y, when in fact Y leads to X. Temporal paradoxes are useful plot devices in science fiction movies, but they have no place in medical research. In our bland world, cause must precede effect. As such, smoking leads to lung cancer; lung cancer doesn’t make you smoke more.

But with alcohol, directionality is less obvious. Many studies of alcohol and cardiovascular disease have demonstrated a U-shaped association, with risk being lowest among those who drink moderate amounts of alcohol (usually one to two drinks per day) and higher in those who drink more and also those who drink very little.

But one must ask why some people drink little or no alcohol. There is an important difference between former drinkers and never drinkers. Former drinkers cut back for a reason. More likely than not, the reason for this newfound sobriety was medical. A new cancer diagnosis, the emergence of atrial fibrillation, the development of diabetes, or rising blood pressure are all good reasons to reduce or eliminate alcohol. A cross-sectional study will fail to capture that alcohol consumption changes over time — people who now don’t drink may have imbibed alcohol in years past. It was not abstinence that led to an increased risk for heart disease; it was the increased risk for heart disease that led to abstinence.

You see the same phenomenon with the so-called obesity paradox. The idea that being a little overweight is good for you may appeal when you no longer fit into last year’s pants. But people who are underweight are so for a reason. Malnutrition, cachexia from cancer, or some other cause is almost certainly driving up the risk at the left-hand side of the U-shaped curve that makes the middle part seem better than it actually is.

Food consumption changes over time. A cross-sectional survey at one point in time cannot accurately capture past habits and distant exposures, especially for diseases such as heart disease and cancer that develop slowly over time. Studies on alcohol that try to overcome these shortcomings by eliminating former drinkers, or by using Mendelian randomization to better account for past exposure, do not show a cardiovascular benefit for moderate red wine drinking.

2. The Hors D’oeuvres — The Importance of RCTs

Now that you have made yourself the center of attention, it is time to cement your newfound reputation as a font of scientific knowledge. Most self-respecting hosts will serve smoked salmon as an amuse-bouche before the main meal. When someone mentions the health benefits of fish oils, you should take the opportunity to teach them about confounding.

Fish, especially cold-water fish from northern climates, have relatively high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids. Despite the plethora of observational studies suggesting a cardiovascular benefit, it’s now relatively clear that fish oil or omega-3 supplements have no medical benefit.

This will probably come as a shock to the worried well, but many studies, including VITAL and ASCEND, have demonstrated no cardiovascular or cancer benefit to supplementation with omega-3s. The reason is straightforward and explains why hormone replacement therapy, vitamin D, and myriad purported game-changers never panned out. Confounding is hard to overcome in observational research.

Prior to the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Study, hormone replacement therapy was routinely prescribed to postmenopausal women because numerous observational studies suggested a cardiovascular benefit. But with the publication of the WHI study, it became clear that much of that “benefit” was due to confounding. The women choosing to take hormones were more health conscious at baseline and healthier overall.

A similar phenomenon occurred during COVID. Patients with low serum vitamin D levels had worse outcomes, prompting many to suggest vitamin D supplementation as a possible treatment. Trials did not support the intervention because we’d overlooked the obvious. People with vitamin D deficiency have underlying health problems that contribute to the vitamin D deficiency. They are probably older, frailer, possibly with a poorer diet. No amount of statistical adjustment can account for all those differences, and some degree of residual confounding will always persist.

The only way to overcome confounding is with randomization. When patients are randomly assigned to one group or another, their baseline differences largely balance out if the randomization was performed properly and the groups were large enough. There is a role for observational research, such as in situations where ethics, cost, and practicality do not allow for a randomized controlled trial. But randomized controlled trials have largely put to rest the purported health benefits of over-the-counter fish oils, omega-3s, and vitamin D.

3. The Main Course — Absolute vs Relative Risk

When you get to the main course, all eyes will now be on you. You will almost certainly be called upon to pronounce on the harms or benefits of red meat consumption. Begin by regaling your guests with a little trivia. Ask them if they know the definition of red meat and white meat. When someone says pork is white meat, you can reveal that “pork, the other white meat,” was a marketing slogan with no scientific underpinning. Now that everyone is lulled into a stupefied silence, tell them that red meat comes from mammals and white meat comes from birds. As they process this revelation, you can now launch into the deeply mathematical concept of absolute vs relative risk.

Many etiquette books will caution against bringing up math at a dinner party. These books are wrong. Everyone finds math interesting if they are primed properly. For example, you can point to a study claiming that berries reduce cardiovascular risk in women. Even if true — and there is reason to be cautious, given the observational nature of the research — we need to understand what the authors meant by a 32% risk reduction. (Side note: It was a reduction in hazard, with a hazard ratio of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.49-0.96), but we won’t dwell on the difference between hazard ratios and risk ratios right now.)

This relative risk reduction has to be interpreted carefully. The authors divided the population into quintiles based on their consumption of anthocyanins (the antioxidant in blueberries and strawberries) and compared the bottom fifth (average consumption, 2.5 mg/d) with the top fifth (average consumption, 25 mg/d). The bottom quintile had 126 myocardial infarctions (MIs) over 324,793 patient-years compared with 59 MIs over 332,143 patient-years. Some quick math shows an approximate reduction from 39 to 18 MIs per 100,000 patient-years. Or to put it another way, you must get 4762 women to increase their berry consumption 10-fold for 1 year to prevent one heart attack. Feel free to show people how you calculated this number. They will be impressed by your head for numbers. It is nothing more than 39 minus 18, divided by 100,000, to get the absolute risk reduction. Take the reciprocal of this (ie, 1 divided by this number) to get the number needed to treat.

Describing risks in absolute terms or using number needed to treat (or harm) can help conceptualize statistics that are sometimes hard to wrap your head around.

4. Dessert — Funding

By the time the coffee is served, everyone will be hanging on to your every word. This is as it should be, and you should not be afraid of your newfound power and influence.

Dessert will probably involve some form of chocolate, possibly in cake format. (Anyone who serves fruit as dessert is not someone you should associate with.) Take the opportunity to tell your follow diners that chocolate is not actually good for you and will not boost brain performance.

The health benefits of chocolate are often repeated but rarely scrutinized. In fact, much of the scientific research purporting to show that chocolate is good for you did not actually study chocolate. It usually involved a cocoa bean extract because the chocolate manufacturing process destroys the supposedly health-promoting antioxidants in the cocoa bean. It is true that dark chocolate has more antioxidants than milk chocolate, and that the addition of milk to chocolate further inactivates the potentially healthy antioxidants. But the amount of sugar and fat that has to be added to chocolate to make it palatable precludes any serious consideration about health benefits. Dark chocolate may have less fat and sugar than milk chocolate, but it still has a lot.

But even the cocoa bean extract doesn’t seem to do much for your heart or your brain. The long-awaited COSMOS study was published with surprisingly little fanfare. The largest randomized controlled trial of chocolate (or rather cocoa bean extract) was supposed to settle the issue definitively.

COSMOS showed no cardiovascular or neurocognitive benefit to the cocoa bean extract. But the health halo of chocolate continues to be bolstered by many studies funded by chocolate manufacturers.

We are appropriately critical of the pharmaceutical industry’s involvement in drug research. However, we should not forget that any private entity is prone to the same self-interest regardless of its product’s tastiness. How many of you knew that there was an avocado lobby funding research? No matter how many industry-funded observational studies using surrogate endpoints are out there telling you that chocolate is healthy, a randomized trial with hard clinical endpoints such as COSMOS should generally win the day.

The Final Goodbyes — Summarizing Your Case

As the party slowly winds down and everyone is saddened that you will soon take your leave, synthesize everything you have taught them over the evening. Like movies, not all studies are good. Some are just bad. They can be prone to reverse causation or confounding, and they may report relative risks when absolute risks would be more telling. Reading research studies critically is essential for separating the wheat from the chaff. With the knowledge you have now imparted to your friends, they will be much better consumers of medical news, especially when it comes to food.

And they will no doubt thank you for it by never inviting you to another dinner party!

Labos, a cardiologist at Hôpital, Notre-Dame, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. He has a degree in epidemiology.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

You’re invited to a dinner party but you struggle to make small talk. Do not worry; that will invariably crop up over cocktails. Because all journalism has been reduced to listicles, here are four ways to seem clever at dinner parties.

1. The Predinner Cocktails: A Lesson in Reverse Causation

Wine connoisseurs sniff, swirl, and gently swish the wine in their mouths before spitting out and cleansing their palates to better appreciate the subtlety of each vintage. If you’re not an oenophile, no matter. Whenever somebody claims that moderate amounts of alcohol are good for your heart, this is your moment to pounce. Interject yourself in the conversation and tell everybody about reverse causation.

Reverse causation, also known as protopathic bias, involves misinterpreting the directionality of an association. You assume that X leads to Y, when in fact Y leads to X. Temporal paradoxes are useful plot devices in science fiction movies, but they have no place in medical research. In our bland world, cause must precede effect. As such, smoking leads to lung cancer; lung cancer doesn’t make you smoke more.

But with alcohol, directionality is less obvious. Many studies of alcohol and cardiovascular disease have demonstrated a U-shaped association, with risk being lowest among those who drink moderate amounts of alcohol (usually one to two drinks per day) and higher in those who drink more and also those who drink very little.

But one must ask why some people drink little or no alcohol. There is an important difference between former drinkers and never drinkers. Former drinkers cut back for a reason. More likely than not, the reason for this newfound sobriety was medical. A new cancer diagnosis, the emergence of atrial fibrillation, the development of diabetes, or rising blood pressure are all good reasons to reduce or eliminate alcohol. A cross-sectional study will fail to capture that alcohol consumption changes over time — people who now don’t drink may have imbibed alcohol in years past. It was not abstinence that led to an increased risk for heart disease; it was the increased risk for heart disease that led to abstinence.

You see the same phenomenon with the so-called obesity paradox. The idea that being a little overweight is good for you may appeal when you no longer fit into last year’s pants. But people who are underweight are so for a reason. Malnutrition, cachexia from cancer, or some other cause is almost certainly driving up the risk at the left-hand side of the U-shaped curve that makes the middle part seem better than it actually is.

Food consumption changes over time. A cross-sectional survey at one point in time cannot accurately capture past habits and distant exposures, especially for diseases such as heart disease and cancer that develop slowly over time. Studies on alcohol that try to overcome these shortcomings by eliminating former drinkers, or by using Mendelian randomization to better account for past exposure, do not show a cardiovascular benefit for moderate red wine drinking.

2. The Hors D’oeuvres — The Importance of RCTs

Now that you have made yourself the center of attention, it is time to cement your newfound reputation as a font of scientific knowledge. Most self-respecting hosts will serve smoked salmon as an amuse-bouche before the main meal. When someone mentions the health benefits of fish oils, you should take the opportunity to teach them about confounding.

Fish, especially cold-water fish from northern climates, have relatively high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids. Despite the plethora of observational studies suggesting a cardiovascular benefit, it’s now relatively clear that fish oil or omega-3 supplements have no medical benefit.

This will probably come as a shock to the worried well, but many studies, including VITAL and ASCEND, have demonstrated no cardiovascular or cancer benefit to supplementation with omega-3s. The reason is straightforward and explains why hormone replacement therapy, vitamin D, and myriad purported game-changers never panned out. Confounding is hard to overcome in observational research.

Prior to the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Study, hormone replacement therapy was routinely prescribed to postmenopausal women because numerous observational studies suggested a cardiovascular benefit. But with the publication of the WHI study, it became clear that much of that “benefit” was due to confounding. The women choosing to take hormones were more health conscious at baseline and healthier overall.

A similar phenomenon occurred during COVID. Patients with low serum vitamin D levels had worse outcomes, prompting many to suggest vitamin D supplementation as a possible treatment. Trials did not support the intervention because we’d overlooked the obvious. People with vitamin D deficiency have underlying health problems that contribute to the vitamin D deficiency. They are probably older, frailer, possibly with a poorer diet. No amount of statistical adjustment can account for all those differences, and some degree of residual confounding will always persist.

The only way to overcome confounding is with randomization. When patients are randomly assigned to one group or another, their baseline differences largely balance out if the randomization was performed properly and the groups were large enough. There is a role for observational research, such as in situations where ethics, cost, and practicality do not allow for a randomized controlled trial. But randomized controlled trials have largely put to rest the purported health benefits of over-the-counter fish oils, omega-3s, and vitamin D.

3. The Main Course — Absolute vs Relative Risk

When you get to the main course, all eyes will now be on you. You will almost certainly be called upon to pronounce on the harms or benefits of red meat consumption. Begin by regaling your guests with a little trivia. Ask them if they know the definition of red meat and white meat. When someone says pork is white meat, you can reveal that “pork, the other white meat,” was a marketing slogan with no scientific underpinning. Now that everyone is lulled into a stupefied silence, tell them that red meat comes from mammals and white meat comes from birds. As they process this revelation, you can now launch into the deeply mathematical concept of absolute vs relative risk.

Many etiquette books will caution against bringing up math at a dinner party. These books are wrong. Everyone finds math interesting if they are primed properly. For example, you can point to a study claiming that berries reduce cardiovascular risk in women. Even if true — and there is reason to be cautious, given the observational nature of the research — we need to understand what the authors meant by a 32% risk reduction. (Side note: It was a reduction in hazard, with a hazard ratio of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.49-0.96), but we won’t dwell on the difference between hazard ratios and risk ratios right now.)

This relative risk reduction has to be interpreted carefully. The authors divided the population into quintiles based on their consumption of anthocyanins (the antioxidant in blueberries and strawberries) and compared the bottom fifth (average consumption, 2.5 mg/d) with the top fifth (average consumption, 25 mg/d). The bottom quintile had 126 myocardial infarctions (MIs) over 324,793 patient-years compared with 59 MIs over 332,143 patient-years. Some quick math shows an approximate reduction from 39 to 18 MIs per 100,000 patient-years. Or to put it another way, you must get 4762 women to increase their berry consumption 10-fold for 1 year to prevent one heart attack. Feel free to show people how you calculated this number. They will be impressed by your head for numbers. It is nothing more than 39 minus 18, divided by 100,000, to get the absolute risk reduction. Take the reciprocal of this (ie, 1 divided by this number) to get the number needed to treat.

Describing risks in absolute terms or using number needed to treat (or harm) can help conceptualize statistics that are sometimes hard to wrap your head around.

4. Dessert — Funding

By the time the coffee is served, everyone will be hanging on to your every word. This is as it should be, and you should not be afraid of your newfound power and influence.

Dessert will probably involve some form of chocolate, possibly in cake format. (Anyone who serves fruit as dessert is not someone you should associate with.) Take the opportunity to tell your follow diners that chocolate is not actually good for you and will not boost brain performance.

The health benefits of chocolate are often repeated but rarely scrutinized. In fact, much of the scientific research purporting to show that chocolate is good for you did not actually study chocolate. It usually involved a cocoa bean extract because the chocolate manufacturing process destroys the supposedly health-promoting antioxidants in the cocoa bean. It is true that dark chocolate has more antioxidants than milk chocolate, and that the addition of milk to chocolate further inactivates the potentially healthy antioxidants. But the amount of sugar and fat that has to be added to chocolate to make it palatable precludes any serious consideration about health benefits. Dark chocolate may have less fat and sugar than milk chocolate, but it still has a lot.

But even the cocoa bean extract doesn’t seem to do much for your heart or your brain. The long-awaited COSMOS study was published with surprisingly little fanfare. The largest randomized controlled trial of chocolate (or rather cocoa bean extract) was supposed to settle the issue definitively.

COSMOS showed no cardiovascular or neurocognitive benefit to the cocoa bean extract. But the health halo of chocolate continues to be bolstered by many studies funded by chocolate manufacturers.

We are appropriately critical of the pharmaceutical industry’s involvement in drug research. However, we should not forget that any private entity is prone to the same self-interest regardless of its product’s tastiness. How many of you knew that there was an avocado lobby funding research? No matter how many industry-funded observational studies using surrogate endpoints are out there telling you that chocolate is healthy, a randomized trial with hard clinical endpoints such as COSMOS should generally win the day.

The Final Goodbyes — Summarizing Your Case

As the party slowly winds down and everyone is saddened that you will soon take your leave, synthesize everything you have taught them over the evening. Like movies, not all studies are good. Some are just bad. They can be prone to reverse causation or confounding, and they may report relative risks when absolute risks would be more telling. Reading research studies critically is essential for separating the wheat from the chaff. With the knowledge you have now imparted to your friends, they will be much better consumers of medical news, especially when it comes to food.

And they will no doubt thank you for it by never inviting you to another dinner party!

Labos, a cardiologist at Hôpital, Notre-Dame, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. He has a degree in epidemiology.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Can We Repurpose Obesity Drugs to Reverse Liver Disease?

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has become the most common liver disease worldwide, with a global prevalence of 32.4%. Its growth over the past three decades has occurred in tandem with increasing rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes — two cornerstones of MASLD.

Higher rates of MASLD and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH) with fibrosis are present in adults with obesity and diabetes, noted Arun Sanyal, MD, professor and director of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia.

The success surrounding the medications for obesity and type 2 diabetes, including glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), has sparked studies investigating whether they could also be an effective treatment for liver disease.

In particular, GLP-1 RAs help patients lose weight and/or control diabetes by mimicking the function of the gut hormone GLP-1, released in response to nutrient intake, and are able to increase insulin secretion and reduce glucagon secretion, delay gastric emptying, and reduce appetite and caloric intake.

The studies for MASLD are testing whether these functions will also work against liver disease, either directly or indirectly, through obesity and diabetes control. The early results are promising.

More Than One Risk Factor in Play

MASLD is defined by the presence of hepatic steatosis and at least one of five cardiometabolic risk factors: Overweight/obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia with either low-plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or high triglycerides, or treatment for these conditions.

It is a grim trajectory if the disease progresses to MASH, as the patient may accumulate hepatic fibrosis and go on to develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Typically, more than one risk factor is at play in MASLD, noted Adnan Said, MD, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

“It most commonly occurs in the setting of weight gain and obesity, which are epidemics in the United States and worldwide, as well as the associated condition — metabolic syndrome — which goes along with obesity and includes type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and sleep apnea,” Said, a hepatology and gastroenterology professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, told this news organization.

The research surrounding MASLD is investigating GLP-1 RAs as single agents and in combination with other drugs.

Finding treatment is critical, as there is only one drug — resmetirom — approved for the treatment of MASH with moderate to advanced fibrosis. But because it’s not approved for earlier stages, a treatment gap exists. The drug also doesn’t produce weight loss, which is key to treating MASLD. And while GLP-1 RAs help patients with the weight loss that is critical to MASLD, they are only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Single Agents

The GLP-1 RAs liraglutide and semaglutide, both approved for diabetes and weight loss, are being studied as single agents against liver disease, Said said.

“Their action in the setting of MASLD and MASH is primarily indirect, through systemic pathways, improving these conditions via weight loss, as well as by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing lipotoxicity,” he added.

One of the first trials of these agents for liver disease was in 2016. In that double-blind, randomized, 48-week clinical trial of liraglutide in patients with MASH and overweight, 39% of patients who received liraglutide had a resolution of MASH compared with only 9% of those who received placebo. Moreover, only 9% vs 36% of patients in the treatment vs placebo group had progression of fibrosis.

Since then, a 72-week phase 2 trial in patients with MASH, liver fibrosis (stages F1-F3), and overweight or obesity found that once-daily subcutaneous semaglutide (0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 mg) outperformed placebo on MASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis (36%-59% vs 17%) and on weight loss (5%-13% vs 1%), with the greatest benefits at the largest dose. However, neoplasms were reported in 15% of patients receiving semaglutide vs 8% of those receiving placebo.

A phase 1 trial involving patients with liver stiffness, steatosis, and overweight or obesity found significantly greater reductions in liver fat at 48 weeks with semaglutide vs placebo, as well as decreases in liver enzymes, body weight, and A1c. There was no significant difference in liver stiffness.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis of eight studies found that treatment with 24 weeks of semaglutide significantly improved liver enzymes, reduced liver stiffness, and improved metabolic parameters in patients with MASLD/MASH. The authors cautioned that gastrointestinal adverse effects “could be a major concern.”

Several studies have found other GLP-1 RAs, including exenatide and dulaglutide, have a beneficial impact on liver injury indices and liver steatosis.

A new retrospective observational study offers evidence that GLP-1 RAs may have a direct impact on MASLD, independent of weight loss. Among the 28% of patients with type 2 diabetes and MASLD who received a GLP-1 RA, there was a significant reduction not only in body mass index but also in A1c, liver enzymes, and controlled attenuation parameter scores. A beneficial impact on liver parameters was observed even in patients who didn’t lose weight. While there was no difference in liver stiffness measurement, the median 60-month follow-up time may not have been long enough to capture such changes.

Another study indicated that the apparent benefits of GLP-1 RAs, in this case semaglutide, may not extend to patients whose disease has progressed to cirrhosis.

Dual and Triple Mechanisms of Action

Newer agents with double or triple mechanisms of action appear to have a more direct effect on the liver.

“Dual agents may have an added effect by improving MASLD directly through adipose regulation and thermogenesis, thereby improving fibrosis,” Said said.

An example is tirzepatide, a GLP-1 RA and an agonist of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). Like GLP-1, GIP is an incretin. When used together as co-agonists, GLP-1 and GIP have been shown to increase insulin and glucagonostatic response and may work synergistically.

A new phase 2 trial that randomly assigned patients with biopsy-confirmed MASH and moderate or severe fibrosis to receive either once-weekly subcutaneous tirzepatide at one of three doses (5, 10, or 15 mg) or placebo found that tirzepatide at each dosage outperformed placebo in resolution of MASH without worsening of fibrosis.

“These findings were encouraging,” Said said. “We’ll see if the results continue into phase 3 trials.”

The combination of GLP-1 RAs with glucagon (GCG) receptor agonists also has garnered interest.

In a phase 2 trial, adults with biopsy-confirmed MASH and fibrosis stages F1-F3 were randomly assigned to receive either one of three doses of the GLP-1/GCG RA survodutide (2.4, 4.8, or 6 mg) or placebo. Survodutide at each dose was found to be superior to placebo in improving MASH without the worsening of fibrosis, reducing liver fat content by at least 30%, and decreasing liver fibrosis by at least one stage, with the 4.8-mg dose showing the best performance for each measure. However, adverse events, including nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting, were more frequent with survodutide than with placebo.

Trials of triple-action agents (GLP-1/GIP/GCG RAs) are underway too.

The hope is the triple agonists could deliver greater reduction in hepatic fat in patients with MASLD, Sanyal said.

Sanyal further noted that a reduction in liver fat is important, citing a meta-analysis that showed ≥ 30% relative decline in liver fat is associated with higher odds of histologic response and MASH resolution.

Sanyal pointed to efocipegtrutide (HM15211), a GLP-1/GIP/GCG RA, which demonstrated significant liver fat reduction after 12 weeks in patients with MASLD in a phase 1b/2a randomized, placebo-controlled trial and is now in phase 2 development.

Another example is retatrutide (LY3437943), a once-weekly injectable, that was associated with up to a 24.2% reduction in body weight at 48 weeks, compared with 2.1% with placebo, in a phase 2 trial involving patients with obesity.

A sub-study assessed the mean relative change from baseline in liver fat at 24 weeks. These participants, who also had MASLD and ≥ 10% of liver fat content, were randomly assigned to receive either retatrutide in one of four doses (1, 4, 8, or 12 mg) or placebo for 48 weeks. All doses of retatrutide showed significantly greater reduction in liver fat content compared with placebo in weeks 24-48, with a mean relative liver fat reduction > 80% at the two higher doses. Moreover, ≥ 80% of participants on the higher retatrutide doses experienced ≥ 70% reduction in liver fat at 48 weeks, compared with 0% reduction in those on placebo, and hepatic steatosis resolved in > 85% of these participants.

This space “continues to evolve at a rapid rate,” Sanyal said. For example, oral dual-action agents are under development.

Obstacles and Warnings

Sanyal warned that GLP-1 RAs can cause nausea, so they have to be introduced at a low dose and slowly titrated upward. They should be used with caution in people with a history of multiple endocrine neoplasia. There is also a small but increased risk for gallstone formation and gallstone-induced pancreatitis with rapid weight loss.

GLP-1 RAs may increase the risk for suicidal ideation, with the authors of a recent study calling for “urgent clarification” regarding this possibility.

Following reports of suicidality submitted through its Adverse Events Reporting System, the FDA concluded that it could find no causal relationship between these agents and increased risk for suicidal ideation but also that it could not “definitively rule out that a small risk may exist” and would continue to investigate.

Access to GLP-1 RAs is an obstacle as well. Semaglutide continues to be on the FDA’s shortage list.

“This is improving, but there are still issues around getting approval from insurance companies,” Sanyal said.

Many patients discontinue use because of tolerability or access issues, which is problematic because most regain the weight they had lost while on the medication.

“Right now, we see GLP-1 RAs as a long-term therapeutic commitment, but there is a lot of research interest in figuring out if there’s a more modest benefit — almost an induction-remission maintenance approach to weight loss,” Sanyal said. These are “evolving trends,” and it’s unclear how they will unfold.

“As of now, you have to decide that if you’re putting your patient on these medications, they will have to take them on a long-term basis and include that consideration in your risk-benefit analysis, together with any concerns about adverse effects,” he said.

Sanyal reported consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Said received research support from Exact Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Mallinckrodt.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has become the most common liver disease worldwide, with a global prevalence of 32.4%. Its growth over the past three decades has occurred in tandem with increasing rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes — two cornerstones of MASLD.

Higher rates of MASLD and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH) with fibrosis are present in adults with obesity and diabetes, noted Arun Sanyal, MD, professor and director of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia.

The success surrounding the medications for obesity and type 2 diabetes, including glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), has sparked studies investigating whether they could also be an effective treatment for liver disease.

In particular, GLP-1 RAs help patients lose weight and/or control diabetes by mimicking the function of the gut hormone GLP-1, released in response to nutrient intake, and are able to increase insulin secretion and reduce glucagon secretion, delay gastric emptying, and reduce appetite and caloric intake.

The studies for MASLD are testing whether these functions will also work against liver disease, either directly or indirectly, through obesity and diabetes control. The early results are promising.

More Than One Risk Factor in Play

MASLD is defined by the presence of hepatic steatosis and at least one of five cardiometabolic risk factors: Overweight/obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia with either low-plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or high triglycerides, or treatment for these conditions.

It is a grim trajectory if the disease progresses to MASH, as the patient may accumulate hepatic fibrosis and go on to develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Typically, more than one risk factor is at play in MASLD, noted Adnan Said, MD, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

“It most commonly occurs in the setting of weight gain and obesity, which are epidemics in the United States and worldwide, as well as the associated condition — metabolic syndrome — which goes along with obesity and includes type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and sleep apnea,” Said, a hepatology and gastroenterology professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, told this news organization.

The research surrounding MASLD is investigating GLP-1 RAs as single agents and in combination with other drugs.

Finding treatment is critical, as there is only one drug — resmetirom — approved for the treatment of MASH with moderate to advanced fibrosis. But because it’s not approved for earlier stages, a treatment gap exists. The drug also doesn’t produce weight loss, which is key to treating MASLD. And while GLP-1 RAs help patients with the weight loss that is critical to MASLD, they are only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Single Agents

The GLP-1 RAs liraglutide and semaglutide, both approved for diabetes and weight loss, are being studied as single agents against liver disease, Said said.

“Their action in the setting of MASLD and MASH is primarily indirect, through systemic pathways, improving these conditions via weight loss, as well as by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing lipotoxicity,” he added.

One of the first trials of these agents for liver disease was in 2016. In that double-blind, randomized, 48-week clinical trial of liraglutide in patients with MASH and overweight, 39% of patients who received liraglutide had a resolution of MASH compared with only 9% of those who received placebo. Moreover, only 9% vs 36% of patients in the treatment vs placebo group had progression of fibrosis.

Since then, a 72-week phase 2 trial in patients with MASH, liver fibrosis (stages F1-F3), and overweight or obesity found that once-daily subcutaneous semaglutide (0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 mg) outperformed placebo on MASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis (36%-59% vs 17%) and on weight loss (5%-13% vs 1%), with the greatest benefits at the largest dose. However, neoplasms were reported in 15% of patients receiving semaglutide vs 8% of those receiving placebo.

A phase 1 trial involving patients with liver stiffness, steatosis, and overweight or obesity found significantly greater reductions in liver fat at 48 weeks with semaglutide vs placebo, as well as decreases in liver enzymes, body weight, and A1c. There was no significant difference in liver stiffness.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis of eight studies found that treatment with 24 weeks of semaglutide significantly improved liver enzymes, reduced liver stiffness, and improved metabolic parameters in patients with MASLD/MASH. The authors cautioned that gastrointestinal adverse effects “could be a major concern.”

Several studies have found other GLP-1 RAs, including exenatide and dulaglutide, have a beneficial impact on liver injury indices and liver steatosis.

A new retrospective observational study offers evidence that GLP-1 RAs may have a direct impact on MASLD, independent of weight loss. Among the 28% of patients with type 2 diabetes and MASLD who received a GLP-1 RA, there was a significant reduction not only in body mass index but also in A1c, liver enzymes, and controlled attenuation parameter scores. A beneficial impact on liver parameters was observed even in patients who didn’t lose weight. While there was no difference in liver stiffness measurement, the median 60-month follow-up time may not have been long enough to capture such changes.

Another study indicated that the apparent benefits of GLP-1 RAs, in this case semaglutide, may not extend to patients whose disease has progressed to cirrhosis.

Dual and Triple Mechanisms of Action

Newer agents with double or triple mechanisms of action appear to have a more direct effect on the liver.

“Dual agents may have an added effect by improving MASLD directly through adipose regulation and thermogenesis, thereby improving fibrosis,” Said said.

An example is tirzepatide, a GLP-1 RA and an agonist of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). Like GLP-1, GIP is an incretin. When used together as co-agonists, GLP-1 and GIP have been shown to increase insulin and glucagonostatic response and may work synergistically.

A new phase 2 trial that randomly assigned patients with biopsy-confirmed MASH and moderate or severe fibrosis to receive either once-weekly subcutaneous tirzepatide at one of three doses (5, 10, or 15 mg) or placebo found that tirzepatide at each dosage outperformed placebo in resolution of MASH without worsening of fibrosis.

“These findings were encouraging,” Said said. “We’ll see if the results continue into phase 3 trials.”

The combination of GLP-1 RAs with glucagon (GCG) receptor agonists also has garnered interest.

In a phase 2 trial, adults with biopsy-confirmed MASH and fibrosis stages F1-F3 were randomly assigned to receive either one of three doses of the GLP-1/GCG RA survodutide (2.4, 4.8, or 6 mg) or placebo. Survodutide at each dose was found to be superior to placebo in improving MASH without the worsening of fibrosis, reducing liver fat content by at least 30%, and decreasing liver fibrosis by at least one stage, with the 4.8-mg dose showing the best performance for each measure. However, adverse events, including nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting, were more frequent with survodutide than with placebo.

Trials of triple-action agents (GLP-1/GIP/GCG RAs) are underway too.

The hope is the triple agonists could deliver greater reduction in hepatic fat in patients with MASLD, Sanyal said.

Sanyal further noted that a reduction in liver fat is important, citing a meta-analysis that showed ≥ 30% relative decline in liver fat is associated with higher odds of histologic response and MASH resolution.

Sanyal pointed to efocipegtrutide (HM15211), a GLP-1/GIP/GCG RA, which demonstrated significant liver fat reduction after 12 weeks in patients with MASLD in a phase 1b/2a randomized, placebo-controlled trial and is now in phase 2 development.

Another example is retatrutide (LY3437943), a once-weekly injectable, that was associated with up to a 24.2% reduction in body weight at 48 weeks, compared with 2.1% with placebo, in a phase 2 trial involving patients with obesity.

A sub-study assessed the mean relative change from baseline in liver fat at 24 weeks. These participants, who also had MASLD and ≥ 10% of liver fat content, were randomly assigned to receive either retatrutide in one of four doses (1, 4, 8, or 12 mg) or placebo for 48 weeks. All doses of retatrutide showed significantly greater reduction in liver fat content compared with placebo in weeks 24-48, with a mean relative liver fat reduction > 80% at the two higher doses. Moreover, ≥ 80% of participants on the higher retatrutide doses experienced ≥ 70% reduction in liver fat at 48 weeks, compared with 0% reduction in those on placebo, and hepatic steatosis resolved in > 85% of these participants.

This space “continues to evolve at a rapid rate,” Sanyal said. For example, oral dual-action agents are under development.

Obstacles and Warnings

Sanyal warned that GLP-1 RAs can cause nausea, so they have to be introduced at a low dose and slowly titrated upward. They should be used with caution in people with a history of multiple endocrine neoplasia. There is also a small but increased risk for gallstone formation and gallstone-induced pancreatitis with rapid weight loss.

GLP-1 RAs may increase the risk for suicidal ideation, with the authors of a recent study calling for “urgent clarification” regarding this possibility.

Following reports of suicidality submitted through its Adverse Events Reporting System, the FDA concluded that it could find no causal relationship between these agents and increased risk for suicidal ideation but also that it could not “definitively rule out that a small risk may exist” and would continue to investigate.

Access to GLP-1 RAs is an obstacle as well. Semaglutide continues to be on the FDA’s shortage list.

“This is improving, but there are still issues around getting approval from insurance companies,” Sanyal said.

Many patients discontinue use because of tolerability or access issues, which is problematic because most regain the weight they had lost while on the medication.

“Right now, we see GLP-1 RAs as a long-term therapeutic commitment, but there is a lot of research interest in figuring out if there’s a more modest benefit — almost an induction-remission maintenance approach to weight loss,” Sanyal said. These are “evolving trends,” and it’s unclear how they will unfold.

“As of now, you have to decide that if you’re putting your patient on these medications, they will have to take them on a long-term basis and include that consideration in your risk-benefit analysis, together with any concerns about adverse effects,” he said.

Sanyal reported consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Said received research support from Exact Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Mallinckrodt.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has become the most common liver disease worldwide, with a global prevalence of 32.4%. Its growth over the past three decades has occurred in tandem with increasing rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes — two cornerstones of MASLD.

Higher rates of MASLD and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH) with fibrosis are present in adults with obesity and diabetes, noted Arun Sanyal, MD, professor and director of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia.

The success surrounding the medications for obesity and type 2 diabetes, including glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), has sparked studies investigating whether they could also be an effective treatment for liver disease.

In particular, GLP-1 RAs help patients lose weight and/or control diabetes by mimicking the function of the gut hormone GLP-1, released in response to nutrient intake, and are able to increase insulin secretion and reduce glucagon secretion, delay gastric emptying, and reduce appetite and caloric intake.

The studies for MASLD are testing whether these functions will also work against liver disease, either directly or indirectly, through obesity and diabetes control. The early results are promising.

More Than One Risk Factor in Play

MASLD is defined by the presence of hepatic steatosis and at least one of five cardiometabolic risk factors: Overweight/obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia with either low-plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or high triglycerides, or treatment for these conditions.

It is a grim trajectory if the disease progresses to MASH, as the patient may accumulate hepatic fibrosis and go on to develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Typically, more than one risk factor is at play in MASLD, noted Adnan Said, MD, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

“It most commonly occurs in the setting of weight gain and obesity, which are epidemics in the United States and worldwide, as well as the associated condition — metabolic syndrome — which goes along with obesity and includes type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and sleep apnea,” Said, a hepatology and gastroenterology professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, told this news organization.

The research surrounding MASLD is investigating GLP-1 RAs as single agents and in combination with other drugs.

Finding treatment is critical, as there is only one drug — resmetirom — approved for the treatment of MASH with moderate to advanced fibrosis. But because it’s not approved for earlier stages, a treatment gap exists. The drug also doesn’t produce weight loss, which is key to treating MASLD. And while GLP-1 RAs help patients with the weight loss that is critical to MASLD, they are only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Single Agents

The GLP-1 RAs liraglutide and semaglutide, both approved for diabetes and weight loss, are being studied as single agents against liver disease, Said said.

“Their action in the setting of MASLD and MASH is primarily indirect, through systemic pathways, improving these conditions via weight loss, as well as by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing lipotoxicity,” he added.

One of the first trials of these agents for liver disease was in 2016. In that double-blind, randomized, 48-week clinical trial of liraglutide in patients with MASH and overweight, 39% of patients who received liraglutide had a resolution of MASH compared with only 9% of those who received placebo. Moreover, only 9% vs 36% of patients in the treatment vs placebo group had progression of fibrosis.

Since then, a 72-week phase 2 trial in patients with MASH, liver fibrosis (stages F1-F3), and overweight or obesity found that once-daily subcutaneous semaglutide (0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 mg) outperformed placebo on MASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis (36%-59% vs 17%) and on weight loss (5%-13% vs 1%), with the greatest benefits at the largest dose. However, neoplasms were reported in 15% of patients receiving semaglutide vs 8% of those receiving placebo.

A phase 1 trial involving patients with liver stiffness, steatosis, and overweight or obesity found significantly greater reductions in liver fat at 48 weeks with semaglutide vs placebo, as well as decreases in liver enzymes, body weight, and A1c. There was no significant difference in liver stiffness.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis of eight studies found that treatment with 24 weeks of semaglutide significantly improved liver enzymes, reduced liver stiffness, and improved metabolic parameters in patients with MASLD/MASH. The authors cautioned that gastrointestinal adverse effects “could be a major concern.”

Several studies have found other GLP-1 RAs, including exenatide and dulaglutide, have a beneficial impact on liver injury indices and liver steatosis.

A new retrospective observational study offers evidence that GLP-1 RAs may have a direct impact on MASLD, independent of weight loss. Among the 28% of patients with type 2 diabetes and MASLD who received a GLP-1 RA, there was a significant reduction not only in body mass index but also in A1c, liver enzymes, and controlled attenuation parameter scores. A beneficial impact on liver parameters was observed even in patients who didn’t lose weight. While there was no difference in liver stiffness measurement, the median 60-month follow-up time may not have been long enough to capture such changes.

Another study indicated that the apparent benefits of GLP-1 RAs, in this case semaglutide, may not extend to patients whose disease has progressed to cirrhosis.

Dual and Triple Mechanisms of Action

Newer agents with double or triple mechanisms of action appear to have a more direct effect on the liver.

“Dual agents may have an added effect by improving MASLD directly through adipose regulation and thermogenesis, thereby improving fibrosis,” Said said.

An example is tirzepatide, a GLP-1 RA and an agonist of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). Like GLP-1, GIP is an incretin. When used together as co-agonists, GLP-1 and GIP have been shown to increase insulin and glucagonostatic response and may work synergistically.

A new phase 2 trial that randomly assigned patients with biopsy-confirmed MASH and moderate or severe fibrosis to receive either once-weekly subcutaneous tirzepatide at one of three doses (5, 10, or 15 mg) or placebo found that tirzepatide at each dosage outperformed placebo in resolution of MASH without worsening of fibrosis.

“These findings were encouraging,” Said said. “We’ll see if the results continue into phase 3 trials.”

The combination of GLP-1 RAs with glucagon (GCG) receptor agonists also has garnered interest.

In a phase 2 trial, adults with biopsy-confirmed MASH and fibrosis stages F1-F3 were randomly assigned to receive either one of three doses of the GLP-1/GCG RA survodutide (2.4, 4.8, or 6 mg) or placebo. Survodutide at each dose was found to be superior to placebo in improving MASH without the worsening of fibrosis, reducing liver fat content by at least 30%, and decreasing liver fibrosis by at least one stage, with the 4.8-mg dose showing the best performance for each measure. However, adverse events, including nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting, were more frequent with survodutide than with placebo.

Trials of triple-action agents (GLP-1/GIP/GCG RAs) are underway too.

The hope is the triple agonists could deliver greater reduction in hepatic fat in patients with MASLD, Sanyal said.

Sanyal further noted that a reduction in liver fat is important, citing a meta-analysis that showed ≥ 30% relative decline in liver fat is associated with higher odds of histologic response and MASH resolution.

Sanyal pointed to efocipegtrutide (HM15211), a GLP-1/GIP/GCG RA, which demonstrated significant liver fat reduction after 12 weeks in patients with MASLD in a phase 1b/2a randomized, placebo-controlled trial and is now in phase 2 development.

Another example is retatrutide (LY3437943), a once-weekly injectable, that was associated with up to a 24.2% reduction in body weight at 48 weeks, compared with 2.1% with placebo, in a phase 2 trial involving patients with obesity.

A sub-study assessed the mean relative change from baseline in liver fat at 24 weeks. These participants, who also had MASLD and ≥ 10% of liver fat content, were randomly assigned to receive either retatrutide in one of four doses (1, 4, 8, or 12 mg) or placebo for 48 weeks. All doses of retatrutide showed significantly greater reduction in liver fat content compared with placebo in weeks 24-48, with a mean relative liver fat reduction > 80% at the two higher doses. Moreover, ≥ 80% of participants on the higher retatrutide doses experienced ≥ 70% reduction in liver fat at 48 weeks, compared with 0% reduction in those on placebo, and hepatic steatosis resolved in > 85% of these participants.

This space “continues to evolve at a rapid rate,” Sanyal said. For example, oral dual-action agents are under development.

Obstacles and Warnings

Sanyal warned that GLP-1 RAs can cause nausea, so they have to be introduced at a low dose and slowly titrated upward. They should be used with caution in people with a history of multiple endocrine neoplasia. There is also a small but increased risk for gallstone formation and gallstone-induced pancreatitis with rapid weight loss.

GLP-1 RAs may increase the risk for suicidal ideation, with the authors of a recent study calling for “urgent clarification” regarding this possibility.

Following reports of suicidality submitted through its Adverse Events Reporting System, the FDA concluded that it could find no causal relationship between these agents and increased risk for suicidal ideation but also that it could not “definitively rule out that a small risk may exist” and would continue to investigate.

Access to GLP-1 RAs is an obstacle as well. Semaglutide continues to be on the FDA’s shortage list.

“This is improving, but there are still issues around getting approval from insurance companies,” Sanyal said.

Many patients discontinue use because of tolerability or access issues, which is problematic because most regain the weight they had lost while on the medication.

“Right now, we see GLP-1 RAs as a long-term therapeutic commitment, but there is a lot of research interest in figuring out if there’s a more modest benefit — almost an induction-remission maintenance approach to weight loss,” Sanyal said. These are “evolving trends,” and it’s unclear how they will unfold.

“As of now, you have to decide that if you’re putting your patient on these medications, they will have to take them on a long-term basis and include that consideration in your risk-benefit analysis, together with any concerns about adverse effects,” he said.

Sanyal reported consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Said received research support from Exact Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Mallinckrodt.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

State of Confusion: Should All Children Get Lipid Labs for High Cholesterol?

Clinicians receive conflicting advice on whether to order blood tests to screen for lipids in children. A new study could add to the confusion. Researchers found that a combination of physical proxy measures such as hypertension and body mass index (BMI) predicted the risk for future cardiovascular events as well as the physical model plus lipid labs, questioning the value of those blood tests.

Some medical organizations advise screening only for high-risk children because more research is needed to define the harms and benefits of universal screening. Diet and behavioral changes are sufficient for most children, and universal screening could lead to false positives and unnecessary further testing, they said.

Groups that favor lipid tests for all children say these measurements detect familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) that would not otherwise be diagnosed, leading to treatment with drugs like statins and a greater chance of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adulthood.