User login

Liver cancer death rates down for Asians and Pacific Islanders

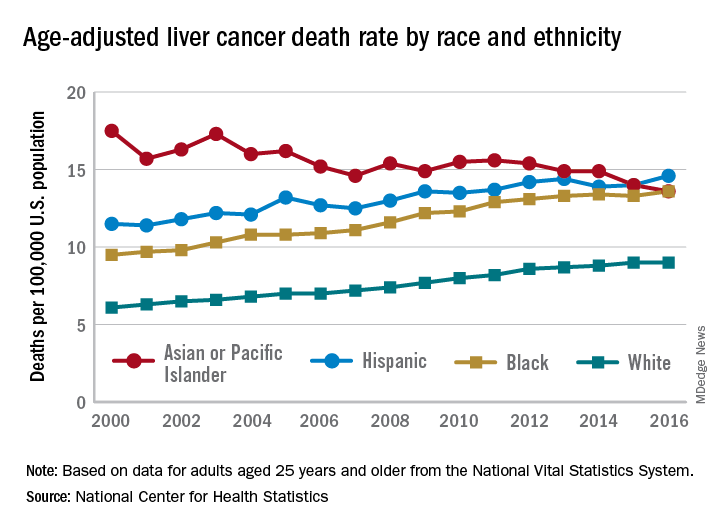

Liver cancer death rates are dropping for Asians/Pacific Islanders, but that is the exception to a larger trend, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The age-adjusted death rate for liver cancer is down 22% among Asian or Pacific Islander adults aged 25 years and older since the turn of the century, falling from 17.5 per 100,000 population in 2000 – when it was the highest of the four racial/ethnic groups included in the report – to 13.6 per 100,000 in 2016, by which time it was just middle of the pack, the NCHS reported.

That shift resulted as much from increases for the other groups as from the decreased rate for Asians/Pacific Islanders. White adults were dying of liver cancer at a 48% higher rate in 2016 (9.0 per 100,000) than they were in 2000 (6.1), blacks saw their death rate go from 9.5 to 13.6 – a 43% increase – and the rate for Hispanics rose by 27% from 2000 (11.5) to 2016 (14.6), said Jiaquan Xu, MD, of the NCHS mortality statistics branch.

The adjusted death rate from liver cancer for all adults went from 7.2 per 100,000 in 2000 to 10.3 in 2016 for an increase of 43%. Over that period, the rate for men was always at least twice as high as it was for women: It rose from 10.5 per 100,000 for men and 4.9 for women in 2000 to 15.0 for men and 6.3 for women in 2016, Dr. Xu said based on data from the mortality files of the National Vital Statistics System.

Geographically, the District of Columbia had the highest rate at 16.8 per 100,000 in 2016, followed by Louisiana (13.8), Hawaii (12.7), and Mississippi and New Mexico (12.4 each). Vermont’s rate of 6.0 was the lowest in the country, with Maine second at 7.4, Montana third at 7.7, and Utah and Nebraska tied for fourth at 7.8, according to Dr. Xu.

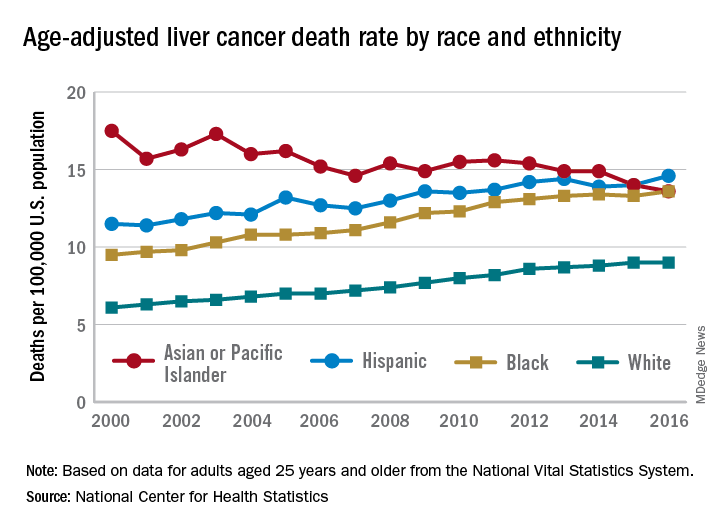

Liver cancer death rates are dropping for Asians/Pacific Islanders, but that is the exception to a larger trend, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The age-adjusted death rate for liver cancer is down 22% among Asian or Pacific Islander adults aged 25 years and older since the turn of the century, falling from 17.5 per 100,000 population in 2000 – when it was the highest of the four racial/ethnic groups included in the report – to 13.6 per 100,000 in 2016, by which time it was just middle of the pack, the NCHS reported.

That shift resulted as much from increases for the other groups as from the decreased rate for Asians/Pacific Islanders. White adults were dying of liver cancer at a 48% higher rate in 2016 (9.0 per 100,000) than they were in 2000 (6.1), blacks saw their death rate go from 9.5 to 13.6 – a 43% increase – and the rate for Hispanics rose by 27% from 2000 (11.5) to 2016 (14.6), said Jiaquan Xu, MD, of the NCHS mortality statistics branch.

The adjusted death rate from liver cancer for all adults went from 7.2 per 100,000 in 2000 to 10.3 in 2016 for an increase of 43%. Over that period, the rate for men was always at least twice as high as it was for women: It rose from 10.5 per 100,000 for men and 4.9 for women in 2000 to 15.0 for men and 6.3 for women in 2016, Dr. Xu said based on data from the mortality files of the National Vital Statistics System.

Geographically, the District of Columbia had the highest rate at 16.8 per 100,000 in 2016, followed by Louisiana (13.8), Hawaii (12.7), and Mississippi and New Mexico (12.4 each). Vermont’s rate of 6.0 was the lowest in the country, with Maine second at 7.4, Montana third at 7.7, and Utah and Nebraska tied for fourth at 7.8, according to Dr. Xu.

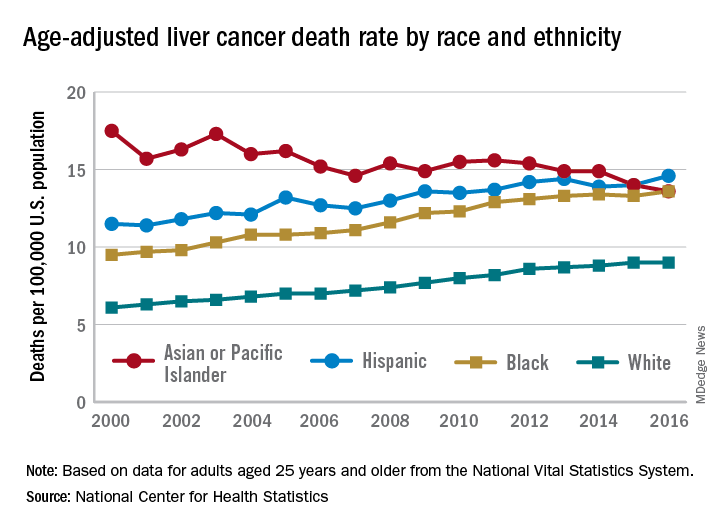

Liver cancer death rates are dropping for Asians/Pacific Islanders, but that is the exception to a larger trend, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The age-adjusted death rate for liver cancer is down 22% among Asian or Pacific Islander adults aged 25 years and older since the turn of the century, falling from 17.5 per 100,000 population in 2000 – when it was the highest of the four racial/ethnic groups included in the report – to 13.6 per 100,000 in 2016, by which time it was just middle of the pack, the NCHS reported.

That shift resulted as much from increases for the other groups as from the decreased rate for Asians/Pacific Islanders. White adults were dying of liver cancer at a 48% higher rate in 2016 (9.0 per 100,000) than they were in 2000 (6.1), blacks saw their death rate go from 9.5 to 13.6 – a 43% increase – and the rate for Hispanics rose by 27% from 2000 (11.5) to 2016 (14.6), said Jiaquan Xu, MD, of the NCHS mortality statistics branch.

The adjusted death rate from liver cancer for all adults went from 7.2 per 100,000 in 2000 to 10.3 in 2016 for an increase of 43%. Over that period, the rate for men was always at least twice as high as it was for women: It rose from 10.5 per 100,000 for men and 4.9 for women in 2000 to 15.0 for men and 6.3 for women in 2016, Dr. Xu said based on data from the mortality files of the National Vital Statistics System.

Geographically, the District of Columbia had the highest rate at 16.8 per 100,000 in 2016, followed by Louisiana (13.8), Hawaii (12.7), and Mississippi and New Mexico (12.4 each). Vermont’s rate of 6.0 was the lowest in the country, with Maine second at 7.4, Montana third at 7.7, and Utah and Nebraska tied for fourth at 7.8, according to Dr. Xu.

Real-time microarrays can simultaneously detect HCV and HIV-1, -2 infections

The use of TaqMan Array Card (TAC) microarrays has been extended to permit simultaneous detection of HIV-1, HIV-2, and five hepatitis viruses from a small amount of extracted nucleic acid, according to a study by Timothy C. Granade, MD, and his colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta.

This is particularly important for dealing with HIV-infected individuals, because HIV-1 and HIV-2 require different treatment interventions, and approximately one-third of HIV-infected patients have been found to be coinfected with hepatitis C or hepatitis B, according to the study report, published in the Journal of Virological Methods (J Virol Methods. 2018 Sep;259:60-5).

HIV-1-positive plasma samples from a variety of subtypes as well as whole blood specimens were confirmed for HIV-1-infection serologically or by nucleic amplification methods. HIV-2 whole blood and plasma specimens were also obtained.

TAC cards contained one positive control, one negative control, three HIV-1 replicates, and two HIV-2 replicates. In addition, the five common hepatitis viruses (A-E) were each replicated three times on each card. The cards were used to test the RNA isolates obtained from the various samples.

Ninety-five of the 104 known HIV-1-positive specimens were assayed positive using TAC; 23 of 26 HIV-2-seeded specimens were detectable using TAC and no cross-reactivity was seen between HIV-1-positive and HIV-2-positive specimens.

Eighteen of the HIV-1-positive specimens were also reactive in triplicate for HCV; three of the HIV-1-positive specimens were reactive to HBV and one specimen was reactive to HIV-1, HBV, and HCV.

“The TAC assay could be invaluable in large-scale screening environments or in surveying local outbreaks such as the recent HIV cluster found in Indiana. Many of these individuals were later determined to be infected with hepatitis C. The use of TAC could shorten the time to identifying and confirming such cases and permit the detection of multiple blood-borne infections in a single test. Application of TAC technology to general population surveillance could identify problem areas for both HIV prevention and intervention efforts in a variety of global environs,” the researchers concluded.

The authors were employed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, which funded the study.

The use of TaqMan Array Card (TAC) microarrays has been extended to permit simultaneous detection of HIV-1, HIV-2, and five hepatitis viruses from a small amount of extracted nucleic acid, according to a study by Timothy C. Granade, MD, and his colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta.

This is particularly important for dealing with HIV-infected individuals, because HIV-1 and HIV-2 require different treatment interventions, and approximately one-third of HIV-infected patients have been found to be coinfected with hepatitis C or hepatitis B, according to the study report, published in the Journal of Virological Methods (J Virol Methods. 2018 Sep;259:60-5).

HIV-1-positive plasma samples from a variety of subtypes as well as whole blood specimens were confirmed for HIV-1-infection serologically or by nucleic amplification methods. HIV-2 whole blood and plasma specimens were also obtained.

TAC cards contained one positive control, one negative control, three HIV-1 replicates, and two HIV-2 replicates. In addition, the five common hepatitis viruses (A-E) were each replicated three times on each card. The cards were used to test the RNA isolates obtained from the various samples.

Ninety-five of the 104 known HIV-1-positive specimens were assayed positive using TAC; 23 of 26 HIV-2-seeded specimens were detectable using TAC and no cross-reactivity was seen between HIV-1-positive and HIV-2-positive specimens.

Eighteen of the HIV-1-positive specimens were also reactive in triplicate for HCV; three of the HIV-1-positive specimens were reactive to HBV and one specimen was reactive to HIV-1, HBV, and HCV.

“The TAC assay could be invaluable in large-scale screening environments or in surveying local outbreaks such as the recent HIV cluster found in Indiana. Many of these individuals were later determined to be infected with hepatitis C. The use of TAC could shorten the time to identifying and confirming such cases and permit the detection of multiple blood-borne infections in a single test. Application of TAC technology to general population surveillance could identify problem areas for both HIV prevention and intervention efforts in a variety of global environs,” the researchers concluded.

The authors were employed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, which funded the study.

The use of TaqMan Array Card (TAC) microarrays has been extended to permit simultaneous detection of HIV-1, HIV-2, and five hepatitis viruses from a small amount of extracted nucleic acid, according to a study by Timothy C. Granade, MD, and his colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta.

This is particularly important for dealing with HIV-infected individuals, because HIV-1 and HIV-2 require different treatment interventions, and approximately one-third of HIV-infected patients have been found to be coinfected with hepatitis C or hepatitis B, according to the study report, published in the Journal of Virological Methods (J Virol Methods. 2018 Sep;259:60-5).

HIV-1-positive plasma samples from a variety of subtypes as well as whole blood specimens were confirmed for HIV-1-infection serologically or by nucleic amplification methods. HIV-2 whole blood and plasma specimens were also obtained.

TAC cards contained one positive control, one negative control, three HIV-1 replicates, and two HIV-2 replicates. In addition, the five common hepatitis viruses (A-E) were each replicated three times on each card. The cards were used to test the RNA isolates obtained from the various samples.

Ninety-five of the 104 known HIV-1-positive specimens were assayed positive using TAC; 23 of 26 HIV-2-seeded specimens were detectable using TAC and no cross-reactivity was seen between HIV-1-positive and HIV-2-positive specimens.

Eighteen of the HIV-1-positive specimens were also reactive in triplicate for HCV; three of the HIV-1-positive specimens were reactive to HBV and one specimen was reactive to HIV-1, HBV, and HCV.

“The TAC assay could be invaluable in large-scale screening environments or in surveying local outbreaks such as the recent HIV cluster found in Indiana. Many of these individuals were later determined to be infected with hepatitis C. The use of TAC could shorten the time to identifying and confirming such cases and permit the detection of multiple blood-borne infections in a single test. Application of TAC technology to general population surveillance could identify problem areas for both HIV prevention and intervention efforts in a variety of global environs,” the researchers concluded.

The authors were employed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, which funded the study.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF VIROLOGICAL METHODS

Deaths from liver disease surged in U.S. since 1999

Cirrhosis mortality showed a sharp rise beginning in 2009, with a 3.6% annual increase driven entirely by a surge in alcoholic cirrhosis among young people aged 25-34 years, Elliot B. Tapper, MD, and Neehar D. Parikh, MD, reported in the BMJ. The uptick in hepatocellular carcinoma, however, was gradual and consistent, with a 2% annual increase felt mostly in older people, wrote Dr. Tapper and Dr. Parikh, both at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“The increasing mortality due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma speaks to the expanding socioeconomic impact of liver disease,” the colleagues wrote. “Adverse trends in liver-related mortality are particularly unfortunate given that in most cases the liver disease is preventable. Understanding the factors associated with mortality due to these conditions will inform how best to allocate resources.”

The study extracted its data from the Vital Statistic Cooperative and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators not only examined raw mortality numbers, but analyzed them for demographic and geographic trends, in analyses that controlled for age.

Cirrhosis

During the study period, 460,760 patients died from cirrhosis (20,661 in 1999 and 34,174 in 2016, an increase of 65.4%).

Men were twice as likely to die from cirrhosis. Young people aged 25-34 years had the highest rate of increase (3.7% over the entire period and 10.5% from 2009 to 2016). This was directly driven by parallel increases in both alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related liver diseases, which increased by about 16% and 10%, respectively, in this group.

Native Americans had the highest mortality rate (25.8 per 100,000) followed by whites (12.7 per 100,000). “Notably, by 2016, cirrhosis accounted for 6.3% [up from 4.3% in 2009] and 7% [up from 5.8% in 2009] of deaths for Native Americans aged 25-34 and 35 or more, respectively,” and 2.3% of all deaths among adults aged 25-34 years, the authors wrote.

The increases were largely felt in the southern and western states (about 13 per 100,000 in each region). The greatest increases occurred in Kentucky (6.8%), New Mexico (6%), Arkansas (5.7%), Indiana (5%), and Alabama (5%). There was a statistically significant 1.2% decrease in deaths from cirrhosis in Maryland.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma accounted for 136,442 deaths during the study period (5,112 in 1999 and 11,073 in 2016 – an increase of 116.6%). This represented an average annual increase of 2%.

Men were four times more likely to die from hepatocellular carcinoma. The increase manifested mostly in older people, decreasing in those younger than 55 years. Mortality was highest among Asians and Pacific Islanders (6 per 100,000), followed by blacks (4.94 per 100,000).

The increases were largely felt in western states, with an overall increase of 4.2 per 100,000.

“Many of the same states with worsening cirrhosis-related mortality also experienced worsening mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma, including Oregon and Iowa,” the authors wrote. But mortality from the disease also increased significantly in Arizona (5.1%), Kansas (4.3%), Kentucky (4%), and Washington (3.9%).

“Potential explanations supported by these data include increasing early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma, application of curative or locoregional therapies, and, because hepatitis B is the principal cause of hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide and among Asian Americans, effectiveness of vaccination programs and the efficacy of antiviral therapy for hepatitis B in preventing the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.”

However, they noted, “it is unclear how these trends are, or will be, affected by direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus ... eradication of hepatitis C virus will prevent the development of cirrhosis and its complications, potentially changing these trends in the next 5-10 years. However, therapy for hepatitis C viral infection cannot modify the statistically significant trends observed related to alcohol or the expected increase in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.”

Neither author had any financial disclosure relevant to the work.

SOURCE: Tapper EB et al. BMJ 2018;362:k2817.

Cirrhosis mortality showed a sharp rise beginning in 2009, with a 3.6% annual increase driven entirely by a surge in alcoholic cirrhosis among young people aged 25-34 years, Elliot B. Tapper, MD, and Neehar D. Parikh, MD, reported in the BMJ. The uptick in hepatocellular carcinoma, however, was gradual and consistent, with a 2% annual increase felt mostly in older people, wrote Dr. Tapper and Dr. Parikh, both at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“The increasing mortality due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma speaks to the expanding socioeconomic impact of liver disease,” the colleagues wrote. “Adverse trends in liver-related mortality are particularly unfortunate given that in most cases the liver disease is preventable. Understanding the factors associated with mortality due to these conditions will inform how best to allocate resources.”

The study extracted its data from the Vital Statistic Cooperative and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators not only examined raw mortality numbers, but analyzed them for demographic and geographic trends, in analyses that controlled for age.

Cirrhosis

During the study period, 460,760 patients died from cirrhosis (20,661 in 1999 and 34,174 in 2016, an increase of 65.4%).

Men were twice as likely to die from cirrhosis. Young people aged 25-34 years had the highest rate of increase (3.7% over the entire period and 10.5% from 2009 to 2016). This was directly driven by parallel increases in both alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related liver diseases, which increased by about 16% and 10%, respectively, in this group.

Native Americans had the highest mortality rate (25.8 per 100,000) followed by whites (12.7 per 100,000). “Notably, by 2016, cirrhosis accounted for 6.3% [up from 4.3% in 2009] and 7% [up from 5.8% in 2009] of deaths for Native Americans aged 25-34 and 35 or more, respectively,” and 2.3% of all deaths among adults aged 25-34 years, the authors wrote.

The increases were largely felt in the southern and western states (about 13 per 100,000 in each region). The greatest increases occurred in Kentucky (6.8%), New Mexico (6%), Arkansas (5.7%), Indiana (5%), and Alabama (5%). There was a statistically significant 1.2% decrease in deaths from cirrhosis in Maryland.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma accounted for 136,442 deaths during the study period (5,112 in 1999 and 11,073 in 2016 – an increase of 116.6%). This represented an average annual increase of 2%.

Men were four times more likely to die from hepatocellular carcinoma. The increase manifested mostly in older people, decreasing in those younger than 55 years. Mortality was highest among Asians and Pacific Islanders (6 per 100,000), followed by blacks (4.94 per 100,000).

The increases were largely felt in western states, with an overall increase of 4.2 per 100,000.

“Many of the same states with worsening cirrhosis-related mortality also experienced worsening mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma, including Oregon and Iowa,” the authors wrote. But mortality from the disease also increased significantly in Arizona (5.1%), Kansas (4.3%), Kentucky (4%), and Washington (3.9%).

“Potential explanations supported by these data include increasing early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma, application of curative or locoregional therapies, and, because hepatitis B is the principal cause of hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide and among Asian Americans, effectiveness of vaccination programs and the efficacy of antiviral therapy for hepatitis B in preventing the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.”

However, they noted, “it is unclear how these trends are, or will be, affected by direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus ... eradication of hepatitis C virus will prevent the development of cirrhosis and its complications, potentially changing these trends in the next 5-10 years. However, therapy for hepatitis C viral infection cannot modify the statistically significant trends observed related to alcohol or the expected increase in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.”

Neither author had any financial disclosure relevant to the work.

SOURCE: Tapper EB et al. BMJ 2018;362:k2817.

Cirrhosis mortality showed a sharp rise beginning in 2009, with a 3.6% annual increase driven entirely by a surge in alcoholic cirrhosis among young people aged 25-34 years, Elliot B. Tapper, MD, and Neehar D. Parikh, MD, reported in the BMJ. The uptick in hepatocellular carcinoma, however, was gradual and consistent, with a 2% annual increase felt mostly in older people, wrote Dr. Tapper and Dr. Parikh, both at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“The increasing mortality due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma speaks to the expanding socioeconomic impact of liver disease,” the colleagues wrote. “Adverse trends in liver-related mortality are particularly unfortunate given that in most cases the liver disease is preventable. Understanding the factors associated with mortality due to these conditions will inform how best to allocate resources.”

The study extracted its data from the Vital Statistic Cooperative and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators not only examined raw mortality numbers, but analyzed them for demographic and geographic trends, in analyses that controlled for age.

Cirrhosis

During the study period, 460,760 patients died from cirrhosis (20,661 in 1999 and 34,174 in 2016, an increase of 65.4%).

Men were twice as likely to die from cirrhosis. Young people aged 25-34 years had the highest rate of increase (3.7% over the entire period and 10.5% from 2009 to 2016). This was directly driven by parallel increases in both alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related liver diseases, which increased by about 16% and 10%, respectively, in this group.

Native Americans had the highest mortality rate (25.8 per 100,000) followed by whites (12.7 per 100,000). “Notably, by 2016, cirrhosis accounted for 6.3% [up from 4.3% in 2009] and 7% [up from 5.8% in 2009] of deaths for Native Americans aged 25-34 and 35 or more, respectively,” and 2.3% of all deaths among adults aged 25-34 years, the authors wrote.

The increases were largely felt in the southern and western states (about 13 per 100,000 in each region). The greatest increases occurred in Kentucky (6.8%), New Mexico (6%), Arkansas (5.7%), Indiana (5%), and Alabama (5%). There was a statistically significant 1.2% decrease in deaths from cirrhosis in Maryland.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma accounted for 136,442 deaths during the study period (5,112 in 1999 and 11,073 in 2016 – an increase of 116.6%). This represented an average annual increase of 2%.

Men were four times more likely to die from hepatocellular carcinoma. The increase manifested mostly in older people, decreasing in those younger than 55 years. Mortality was highest among Asians and Pacific Islanders (6 per 100,000), followed by blacks (4.94 per 100,000).

The increases were largely felt in western states, with an overall increase of 4.2 per 100,000.

“Many of the same states with worsening cirrhosis-related mortality also experienced worsening mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma, including Oregon and Iowa,” the authors wrote. But mortality from the disease also increased significantly in Arizona (5.1%), Kansas (4.3%), Kentucky (4%), and Washington (3.9%).

“Potential explanations supported by these data include increasing early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma, application of curative or locoregional therapies, and, because hepatitis B is the principal cause of hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide and among Asian Americans, effectiveness of vaccination programs and the efficacy of antiviral therapy for hepatitis B in preventing the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.”

However, they noted, “it is unclear how these trends are, or will be, affected by direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus ... eradication of hepatitis C virus will prevent the development of cirrhosis and its complications, potentially changing these trends in the next 5-10 years. However, therapy for hepatitis C viral infection cannot modify the statistically significant trends observed related to alcohol or the expected increase in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.”

Neither author had any financial disclosure relevant to the work.

SOURCE: Tapper EB et al. BMJ 2018;362:k2817.

FROM BMJ

Key clinical point: Deaths from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma have surged in the United States since 1999.

Major finding: Liver cirrhosis mortality increased by 65% and hepatocellular carcinoma mortality by about 117%.

Study details: The study extracted data from the National Vital Statistics database and the CDC.

Disclosures: Neither author had relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Tapper EB et al. BMJ 2018;362:k2817.

NAFLD less common, more severe in black children

ORLANDO – according to a review of 503 adolescents at the Yale University pediatric obesity clinic in New Haven, Conn.

As childhood obesity rates have climbed – the prevalence is now estimated to be around 20% – there’s been a corresponding increase in pediatric NAFLD, but it’s not very well characterized in children, and “there are many gaps in our knowledge,” said Nicola Santoro, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology at Yale, and senior author of the review.

The goal of the work was to begin to plug the gaps. The children had baseline abdominal MRIs to quantify their hepatic fat content, along with oral glucose tolerance tests and genotyping for three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) strongly associated with the condition (PNPLA3 rs738409, GCKR rs1260326, and TM6SF2 rs58542926). MRI and metabolic testing were repeated at a mean of 2.27 years in 133 children.

The subjects were 13 years old on average, with a mean body mass index z-score of 2.52; 191 were white, 134 black, and 178 Hispanic. NAFLD was defined as a hepatic fat content of at least 5.5%.

The prevalence of fatty liver was 41.6% but ranged widely by ethnicity, with NAFLD diagnosed in 60% of Hispanic, 43% of white, but only 16% of black children. Among all three groups, prevalence was higher among boys.

Although NAFLD was least common among black children, when it was present, it was worse. Black children with NAFLD, compared with others, had the highest fasting glucose and 2-hour glucose levels; the highest insulin and C-peptide levels, and the highest hemoglobin A1c, despite similar age and gender distribution across the groups.

The findings translated to a higher prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus (66.6%), compared with white (24.4%) and Hispanic children (31.1%) with NAFLD.

Among 76 children who didn’t have NAFLD at baseline, 17 were diagnosed with the condition at follow-up. Progressors, compared with nonprogressors, showed higher baseline C-peptide levels (about 1,250 pmol/L versus 1,000 pmol/L) and greater weight gain (increase, versus a loss of, about 0.1 point on body mass index z-scores). Black children were the least likely to progress to NAFLD.

Increasing BMI z-score, higher baseline fasting C-peptide levels, and nonblack race strongly predicted progression (area under the curve = 0.887). The risk of progression was even higher when a NAFLD SNP was on board (AUC equal to or greater than 0.96).

Of 57 children with NAFLD at baseline, 13 didn’t meet the definition at follow-up, but regression turned out to be harder to predict. Regressors showed lower intrahepatic fat fractions at baseline (about 10% versus 20%), and a lowering of BMI z-scores at follow-up. Adding SNPs didn’t improve the model (AUC = 0.756).

As in adults, weight loss is the single most important factor to reverse NAFLD. “Even if you lose only a few kilos, fatty liver can go away. The liver cleans up pretty easily, but if you keep your weight, or you gain even a little bit, the disease keeps progressing,” Dr. Santoro said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

*This story was updated on 7/20/2018.

SOURCE: Trico D et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 313-OR.

ORLANDO – according to a review of 503 adolescents at the Yale University pediatric obesity clinic in New Haven, Conn.

As childhood obesity rates have climbed – the prevalence is now estimated to be around 20% – there’s been a corresponding increase in pediatric NAFLD, but it’s not very well characterized in children, and “there are many gaps in our knowledge,” said Nicola Santoro, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology at Yale, and senior author of the review.

The goal of the work was to begin to plug the gaps. The children had baseline abdominal MRIs to quantify their hepatic fat content, along with oral glucose tolerance tests and genotyping for three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) strongly associated with the condition (PNPLA3 rs738409, GCKR rs1260326, and TM6SF2 rs58542926). MRI and metabolic testing were repeated at a mean of 2.27 years in 133 children.

The subjects were 13 years old on average, with a mean body mass index z-score of 2.52; 191 were white, 134 black, and 178 Hispanic. NAFLD was defined as a hepatic fat content of at least 5.5%.

The prevalence of fatty liver was 41.6% but ranged widely by ethnicity, with NAFLD diagnosed in 60% of Hispanic, 43% of white, but only 16% of black children. Among all three groups, prevalence was higher among boys.

Although NAFLD was least common among black children, when it was present, it was worse. Black children with NAFLD, compared with others, had the highest fasting glucose and 2-hour glucose levels; the highest insulin and C-peptide levels, and the highest hemoglobin A1c, despite similar age and gender distribution across the groups.

The findings translated to a higher prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus (66.6%), compared with white (24.4%) and Hispanic children (31.1%) with NAFLD.

Among 76 children who didn’t have NAFLD at baseline, 17 were diagnosed with the condition at follow-up. Progressors, compared with nonprogressors, showed higher baseline C-peptide levels (about 1,250 pmol/L versus 1,000 pmol/L) and greater weight gain (increase, versus a loss of, about 0.1 point on body mass index z-scores). Black children were the least likely to progress to NAFLD.

Increasing BMI z-score, higher baseline fasting C-peptide levels, and nonblack race strongly predicted progression (area under the curve = 0.887). The risk of progression was even higher when a NAFLD SNP was on board (AUC equal to or greater than 0.96).

Of 57 children with NAFLD at baseline, 13 didn’t meet the definition at follow-up, but regression turned out to be harder to predict. Regressors showed lower intrahepatic fat fractions at baseline (about 10% versus 20%), and a lowering of BMI z-scores at follow-up. Adding SNPs didn’t improve the model (AUC = 0.756).

As in adults, weight loss is the single most important factor to reverse NAFLD. “Even if you lose only a few kilos, fatty liver can go away. The liver cleans up pretty easily, but if you keep your weight, or you gain even a little bit, the disease keeps progressing,” Dr. Santoro said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

*This story was updated on 7/20/2018.

SOURCE: Trico D et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 313-OR.

ORLANDO – according to a review of 503 adolescents at the Yale University pediatric obesity clinic in New Haven, Conn.

As childhood obesity rates have climbed – the prevalence is now estimated to be around 20% – there’s been a corresponding increase in pediatric NAFLD, but it’s not very well characterized in children, and “there are many gaps in our knowledge,” said Nicola Santoro, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology at Yale, and senior author of the review.

The goal of the work was to begin to plug the gaps. The children had baseline abdominal MRIs to quantify their hepatic fat content, along with oral glucose tolerance tests and genotyping for three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) strongly associated with the condition (PNPLA3 rs738409, GCKR rs1260326, and TM6SF2 rs58542926). MRI and metabolic testing were repeated at a mean of 2.27 years in 133 children.

The subjects were 13 years old on average, with a mean body mass index z-score of 2.52; 191 were white, 134 black, and 178 Hispanic. NAFLD was defined as a hepatic fat content of at least 5.5%.

The prevalence of fatty liver was 41.6% but ranged widely by ethnicity, with NAFLD diagnosed in 60% of Hispanic, 43% of white, but only 16% of black children. Among all three groups, prevalence was higher among boys.

Although NAFLD was least common among black children, when it was present, it was worse. Black children with NAFLD, compared with others, had the highest fasting glucose and 2-hour glucose levels; the highest insulin and C-peptide levels, and the highest hemoglobin A1c, despite similar age and gender distribution across the groups.

The findings translated to a higher prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus (66.6%), compared with white (24.4%) and Hispanic children (31.1%) with NAFLD.

Among 76 children who didn’t have NAFLD at baseline, 17 were diagnosed with the condition at follow-up. Progressors, compared with nonprogressors, showed higher baseline C-peptide levels (about 1,250 pmol/L versus 1,000 pmol/L) and greater weight gain (increase, versus a loss of, about 0.1 point on body mass index z-scores). Black children were the least likely to progress to NAFLD.

Increasing BMI z-score, higher baseline fasting C-peptide levels, and nonblack race strongly predicted progression (area under the curve = 0.887). The risk of progression was even higher when a NAFLD SNP was on board (AUC equal to or greater than 0.96).

Of 57 children with NAFLD at baseline, 13 didn’t meet the definition at follow-up, but regression turned out to be harder to predict. Regressors showed lower intrahepatic fat fractions at baseline (about 10% versus 20%), and a lowering of BMI z-scores at follow-up. Adding SNPs didn’t improve the model (AUC = 0.756).

As in adults, weight loss is the single most important factor to reverse NAFLD. “Even if you lose only a few kilos, fatty liver can go away. The liver cleans up pretty easily, but if you keep your weight, or you gain even a little bit, the disease keeps progressing,” Dr. Santoro said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

*This story was updated on 7/20/2018.

SOURCE: Trico D et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 313-OR.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Obese black children are less likely than others to develop non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, but more likely to suffer its consequences if they do.

Major finding: Black children with NAFLD had a higher prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes (66.6%), compared with white (24.4%) and Hispanic children (31.1%).

Study details: Review of 503 obese adolescents

Disclosures: The investigators didn’t have any disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Trico D et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 313-OR.

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Statins are safe, effective, and important for most patients with liver disease and dyslipidemia

The medications are only contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and statin-induced liver injury, Elizabeth Speliotes, MD, PhD, MPH, and her colleagues wrote in an expert review published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. In these patients, statin treatment can compound liver damage and should be avoided, wrote Dr. Speliotes and her coauthors.

Because the liver plays a central role in cholesterol production, many clinicians shy away from treating hyperlipidemia in patients with liver disease. But studies consistently show that lipid-lowering drugs improve dyslipidemia in these patients, which significantly improves both high- and low-density lipoproteins and thereby reduces the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors wrote.

“Furthermore, the liver plays a role in the metabolism of many drugs, including those that are used to treat dyslipidemia,” wrote Dr. Speliotes of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “It is not surprising, therefore, that many practitioners are hesitant to prescribe medicines to treat dyslipidemia in the setting of liver disease.”

Cholesterol targets described in the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines can safely be applied to patients with liver disease. “The guidelines recommend that adults with cardiovascular disease or LDL of 190 mg/dL or higher be treated with high-intensity statins with the goal of reducing LDL levels by 50%,” they said. Patients whose LDL is 189 mg/dL or lower will benefit from moderate-intensity statins, with a target of a 30%-50% decrease in LDL.

The authors described best practice advice for dyslipidemia treatment in six liver diseases: drug-induced liver injury (DILI), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), viral hepatitis B and C (HBV and HCV), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), cirrhosis, and posttransplant dyslipidemia.

DILI

DILI is characterized by elevations of threefold or more in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase and at least a doubling of total serum bilirubin with no other identifiable cause of these aberrations except the suspect drug. Statins rarely cause a DILI (1 in 100,000 patients), but can cause transient, benign ALT elevations. Statins should be discontinued if ALT or aspartate aminotransferase levels exceed a tripling of the upper limit of normal with concomitant bilirubin elevations. They should not be prescribed to patients with acute liver failure or decompensated liver disease, but otherwise they are safe for most patients with liver disease.

NAFLD

Many patients with NAFLD also have dyslipidemia. All NAFLD patients have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, although NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are not traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Nevertheless, statins and the accompanying improvement in dyslipidemia have been shown to decrease cardiovascular mortality in these patients. The IDEAL study, for example, showed that moderate statin treatment with 80 mg atorvastatin was associated with a 44% decreased risk in secondary cardiovascular events. Other studies show similar results.

NAFLD patients with elevated LDL may benefit from ezetimibe as primary or add-on therapy. However, none of the drugs used to treat dyslipidemia will improve NAFLD or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis histology.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis C virus

Patients with HCV infection often experience decreased serum LDL and total cholesterol. However, these are virally mediated and don’t confer cardiovascular protection. In fact, HCV infections are associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction. If the patient spontaneously clears the virus, lipids may rebound, so levels should be regularly monitored even if the patient does not need statin therapy.

Hepatitis B virus

HBV also interacts with lipid metabolism and can lead to hyperlipidemia. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment and statin therapy apply to these patients. Statins are safe in patients with either HCV or HBV, who tolerate them well.

PBC

PBC is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory cholestatic disease that is associated with dyslipidemia. These patients exhibit increased serum triglyceride and HDL levels that vary according to PBC stage. About 10% have a significant risk of cardiovascular disease. PBC patients with compensated liver disease can safely tolerate statin treatment, but the drugs should not be given to PBC patients with decompensated liver disease.

Obeticholic acid (OCA) is sometimes used as second-line therapy for PBC; it affects genes that regulate bile acid synthesis, transport, and action. However, the POISE study showed that, while OCA improved PBC symptoms, it was associated with an increase in LDL and total cholesterol and a decrease in HDL. No follow-up studies have determined cardiovascular implications of that change, but OCA should be avoided in patients with active cardiovascular disease or with cardiovascular risk factors.

Cirrhosis

Recent work suggests that patients with cirrhosis may face a higher risk of coronary artery disease than was previously thought, although that risk varies widely according to the etiology of the cirrhosis.

Statins are safe and effective in patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis; there are few data on their safety in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Some guidance for these patients exists in the 2014 recommendations of the Liver Expert Panel, which advised against statin use in patients with Child-Pugh class B or C cirrhosis.

There’s some evidence that statins reduce portal pressure and may reduce the risk of decompensation in patients whose cirrhosis is caused by HCV or HBV infections, but they should not be used for this purpose.

Posttransplant dyslipidemia

After liver transplant, more than 60% of patients will develop dyslipidemia; these patients often have obesity or diabetes.

Statins are safe for patients with liver transplant. Concomitant use of calcineurin inhibitors and statins that are metabolized by cytochrome P450 may increase the risk of statin-associated myopathy. Pravastatin and fluvastatin are preferable, because they are metabolized by cytochrome P450 34A.

Neither Dr. Speliotes nor her coauthors had any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Speliotes EK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr 21. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.023.

The medications are only contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and statin-induced liver injury, Elizabeth Speliotes, MD, PhD, MPH, and her colleagues wrote in an expert review published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. In these patients, statin treatment can compound liver damage and should be avoided, wrote Dr. Speliotes and her coauthors.

Because the liver plays a central role in cholesterol production, many clinicians shy away from treating hyperlipidemia in patients with liver disease. But studies consistently show that lipid-lowering drugs improve dyslipidemia in these patients, which significantly improves both high- and low-density lipoproteins and thereby reduces the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors wrote.

“Furthermore, the liver plays a role in the metabolism of many drugs, including those that are used to treat dyslipidemia,” wrote Dr. Speliotes of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “It is not surprising, therefore, that many practitioners are hesitant to prescribe medicines to treat dyslipidemia in the setting of liver disease.”

Cholesterol targets described in the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines can safely be applied to patients with liver disease. “The guidelines recommend that adults with cardiovascular disease or LDL of 190 mg/dL or higher be treated with high-intensity statins with the goal of reducing LDL levels by 50%,” they said. Patients whose LDL is 189 mg/dL or lower will benefit from moderate-intensity statins, with a target of a 30%-50% decrease in LDL.

The authors described best practice advice for dyslipidemia treatment in six liver diseases: drug-induced liver injury (DILI), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), viral hepatitis B and C (HBV and HCV), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), cirrhosis, and posttransplant dyslipidemia.

DILI

DILI is characterized by elevations of threefold or more in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase and at least a doubling of total serum bilirubin with no other identifiable cause of these aberrations except the suspect drug. Statins rarely cause a DILI (1 in 100,000 patients), but can cause transient, benign ALT elevations. Statins should be discontinued if ALT or aspartate aminotransferase levels exceed a tripling of the upper limit of normal with concomitant bilirubin elevations. They should not be prescribed to patients with acute liver failure or decompensated liver disease, but otherwise they are safe for most patients with liver disease.

NAFLD

Many patients with NAFLD also have dyslipidemia. All NAFLD patients have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, although NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are not traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Nevertheless, statins and the accompanying improvement in dyslipidemia have been shown to decrease cardiovascular mortality in these patients. The IDEAL study, for example, showed that moderate statin treatment with 80 mg atorvastatin was associated with a 44% decreased risk in secondary cardiovascular events. Other studies show similar results.

NAFLD patients with elevated LDL may benefit from ezetimibe as primary or add-on therapy. However, none of the drugs used to treat dyslipidemia will improve NAFLD or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis histology.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis C virus

Patients with HCV infection often experience decreased serum LDL and total cholesterol. However, these are virally mediated and don’t confer cardiovascular protection. In fact, HCV infections are associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction. If the patient spontaneously clears the virus, lipids may rebound, so levels should be regularly monitored even if the patient does not need statin therapy.

Hepatitis B virus

HBV also interacts with lipid metabolism and can lead to hyperlipidemia. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment and statin therapy apply to these patients. Statins are safe in patients with either HCV or HBV, who tolerate them well.

PBC

PBC is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory cholestatic disease that is associated with dyslipidemia. These patients exhibit increased serum triglyceride and HDL levels that vary according to PBC stage. About 10% have a significant risk of cardiovascular disease. PBC patients with compensated liver disease can safely tolerate statin treatment, but the drugs should not be given to PBC patients with decompensated liver disease.

Obeticholic acid (OCA) is sometimes used as second-line therapy for PBC; it affects genes that regulate bile acid synthesis, transport, and action. However, the POISE study showed that, while OCA improved PBC symptoms, it was associated with an increase in LDL and total cholesterol and a decrease in HDL. No follow-up studies have determined cardiovascular implications of that change, but OCA should be avoided in patients with active cardiovascular disease or with cardiovascular risk factors.

Cirrhosis

Recent work suggests that patients with cirrhosis may face a higher risk of coronary artery disease than was previously thought, although that risk varies widely according to the etiology of the cirrhosis.

Statins are safe and effective in patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis; there are few data on their safety in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Some guidance for these patients exists in the 2014 recommendations of the Liver Expert Panel, which advised against statin use in patients with Child-Pugh class B or C cirrhosis.

There’s some evidence that statins reduce portal pressure and may reduce the risk of decompensation in patients whose cirrhosis is caused by HCV or HBV infections, but they should not be used for this purpose.

Posttransplant dyslipidemia

After liver transplant, more than 60% of patients will develop dyslipidemia; these patients often have obesity or diabetes.

Statins are safe for patients with liver transplant. Concomitant use of calcineurin inhibitors and statins that are metabolized by cytochrome P450 may increase the risk of statin-associated myopathy. Pravastatin and fluvastatin are preferable, because they are metabolized by cytochrome P450 34A.

Neither Dr. Speliotes nor her coauthors had any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Speliotes EK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr 21. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.023.

The medications are only contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and statin-induced liver injury, Elizabeth Speliotes, MD, PhD, MPH, and her colleagues wrote in an expert review published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. In these patients, statin treatment can compound liver damage and should be avoided, wrote Dr. Speliotes and her coauthors.

Because the liver plays a central role in cholesterol production, many clinicians shy away from treating hyperlipidemia in patients with liver disease. But studies consistently show that lipid-lowering drugs improve dyslipidemia in these patients, which significantly improves both high- and low-density lipoproteins and thereby reduces the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors wrote.

“Furthermore, the liver plays a role in the metabolism of many drugs, including those that are used to treat dyslipidemia,” wrote Dr. Speliotes of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “It is not surprising, therefore, that many practitioners are hesitant to prescribe medicines to treat dyslipidemia in the setting of liver disease.”

Cholesterol targets described in the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines can safely be applied to patients with liver disease. “The guidelines recommend that adults with cardiovascular disease or LDL of 190 mg/dL or higher be treated with high-intensity statins with the goal of reducing LDL levels by 50%,” they said. Patients whose LDL is 189 mg/dL or lower will benefit from moderate-intensity statins, with a target of a 30%-50% decrease in LDL.

The authors described best practice advice for dyslipidemia treatment in six liver diseases: drug-induced liver injury (DILI), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), viral hepatitis B and C (HBV and HCV), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), cirrhosis, and posttransplant dyslipidemia.

DILI

DILI is characterized by elevations of threefold or more in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase and at least a doubling of total serum bilirubin with no other identifiable cause of these aberrations except the suspect drug. Statins rarely cause a DILI (1 in 100,000 patients), but can cause transient, benign ALT elevations. Statins should be discontinued if ALT or aspartate aminotransferase levels exceed a tripling of the upper limit of normal with concomitant bilirubin elevations. They should not be prescribed to patients with acute liver failure or decompensated liver disease, but otherwise they are safe for most patients with liver disease.

NAFLD

Many patients with NAFLD also have dyslipidemia. All NAFLD patients have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, although NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are not traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Nevertheless, statins and the accompanying improvement in dyslipidemia have been shown to decrease cardiovascular mortality in these patients. The IDEAL study, for example, showed that moderate statin treatment with 80 mg atorvastatin was associated with a 44% decreased risk in secondary cardiovascular events. Other studies show similar results.

NAFLD patients with elevated LDL may benefit from ezetimibe as primary or add-on therapy. However, none of the drugs used to treat dyslipidemia will improve NAFLD or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis histology.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis C virus

Patients with HCV infection often experience decreased serum LDL and total cholesterol. However, these are virally mediated and don’t confer cardiovascular protection. In fact, HCV infections are associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction. If the patient spontaneously clears the virus, lipids may rebound, so levels should be regularly monitored even if the patient does not need statin therapy.

Hepatitis B virus

HBV also interacts with lipid metabolism and can lead to hyperlipidemia. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment and statin therapy apply to these patients. Statins are safe in patients with either HCV or HBV, who tolerate them well.

PBC

PBC is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory cholestatic disease that is associated with dyslipidemia. These patients exhibit increased serum triglyceride and HDL levels that vary according to PBC stage. About 10% have a significant risk of cardiovascular disease. PBC patients with compensated liver disease can safely tolerate statin treatment, but the drugs should not be given to PBC patients with decompensated liver disease.

Obeticholic acid (OCA) is sometimes used as second-line therapy for PBC; it affects genes that regulate bile acid synthesis, transport, and action. However, the POISE study showed that, while OCA improved PBC symptoms, it was associated with an increase in LDL and total cholesterol and a decrease in HDL. No follow-up studies have determined cardiovascular implications of that change, but OCA should be avoided in patients with active cardiovascular disease or with cardiovascular risk factors.

Cirrhosis

Recent work suggests that patients with cirrhosis may face a higher risk of coronary artery disease than was previously thought, although that risk varies widely according to the etiology of the cirrhosis.

Statins are safe and effective in patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis; there are few data on their safety in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Some guidance for these patients exists in the 2014 recommendations of the Liver Expert Panel, which advised against statin use in patients with Child-Pugh class B or C cirrhosis.

There’s some evidence that statins reduce portal pressure and may reduce the risk of decompensation in patients whose cirrhosis is caused by HCV or HBV infections, but they should not be used for this purpose.

Posttransplant dyslipidemia

After liver transplant, more than 60% of patients will develop dyslipidemia; these patients often have obesity or diabetes.

Statins are safe for patients with liver transplant. Concomitant use of calcineurin inhibitors and statins that are metabolized by cytochrome P450 may increase the risk of statin-associated myopathy. Pravastatin and fluvastatin are preferable, because they are metabolized by cytochrome P450 34A.

Neither Dr. Speliotes nor her coauthors had any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Speliotes EK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr 21. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.023.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Primary cirrhotic prophylaxis of bacterial peritonitis falls short

WASHINGTON –

The mortality rate during follow-up of cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on primary prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was 19%, compared with a 9% death rate among cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on secondary prophylaxis, Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Although the findings raised questions about the value of primary prophylaxis with an antibiotic in cirrhotic patients for preventing a first episode of SBP, secondary prophylaxis remains an important precaution.

“There is clear benefit from secondary prophylaxis; please use it. The data supporting it are robust,” said Dr. Bajaj, a hepatologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. In contrast, the evidence supporting benefits from primary prophylaxis is weaker, he said. The findings were also counterintuitive, because patients who experience repeat episodes of SBP might be expected to fare worse than those hit by SBP just once.

Dr. Bajaj also acknowledged the substantial confounding that distinguishes patients with cirrhosis receiving primary or secondary prophylaxis, and the difficulty of fully adjusting for all this confounding by statistical analyses. “There is selective bias for secondary prevention, and there is no way to correct for this,” he explained. Patients who need secondary prophylaxis have “weathered the storm” of a first episode of SBP, which might have exerted selection pressure, and might have triggered important immunologic changes, Dr. Bajaj suggested.

The findings also raised concerns about the appropriateness of existing antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP. The patients included in the study all received similar regimens regardless of whether they were on primary or secondary prophylaxis. Three-quarters of primary prophylaxis patients received a fluoroquinolone, as did 81% on secondary prophylaxis. All other patients received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. These regimens are aimed at preventing gram-negative infections; however, an increasing number of SBP episodes are caused by either gram-positive pathogens or strains of gram-negative bacteria or fungi resistant to standard antibiotics.

Clinicians “absolutely” need to rethink their approach to both primary and secondary prophylaxis, Dr. Bajaj said. “As fast as treatment evolves, bacteria evolve 20 times faster. We need to find ways to prevent infections without antibiotic prophylaxis, whatever that might be.”

The study used data collected prospectively from patients with cirrhosis at any of 12 U.S. and 2 Canadian centers that belonged to the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease. Among 2,731 cirrhotic patients admitted nonelectively, 492 (18%) were on antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of their admission, 305 for primary prophylaxis and 187 for secondary prophylaxis. Dr. Bajaj and his associates used both the baseline model for end-stage liver disease score and serum albumin level of each patient to focus on a group of 154 primary prophylaxis and 154 secondary prophylaxis patients who were similar by these two criteria. Despite this matching, the two subgroups showed statistically significant differences at the time of their index hospitalization for several important clinical measures.

The secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized within the previous 6 months, significantly more likely to be on treatment for hepatic encephalopathy at the time of their index admission, and significantly less likely to have systemic inflammatory response syndrome on admission.

Also, at the time of admission, secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have an infection of any type at a rate of 40%, compared with 24% among those on primary prophylaxis, as well as a significantly higher rate of SBP at 16%, compared with a 9% rate among the primary prophylaxis patients. During hospitalization, nosocomial SBP occurred significantly more often among the secondary prophylaxis patients at a rate of 6%, compared with a 0.5% rate among those on primary prophylaxis.

Despite these between-group differences, the average duration of hospitalization, and the average incidence of acute-on-chronic liver failure during follow-up out to 30 days post discharge was similar in the two subgroups. And the patients on secondary prophylaxis showed better outcomes by two important parameters: mortality during hospitalization and 30 days post discharge; and the incidence of ICU admission during hospitalization, which was significantly greater for primary prophylaxis patients at 31%, compared with 21% among the secondary prophylaxis patients, Dr. Bajaj reported.

Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

WASHINGTON –

The mortality rate during follow-up of cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on primary prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was 19%, compared with a 9% death rate among cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on secondary prophylaxis, Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Although the findings raised questions about the value of primary prophylaxis with an antibiotic in cirrhotic patients for preventing a first episode of SBP, secondary prophylaxis remains an important precaution.

“There is clear benefit from secondary prophylaxis; please use it. The data supporting it are robust,” said Dr. Bajaj, a hepatologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. In contrast, the evidence supporting benefits from primary prophylaxis is weaker, he said. The findings were also counterintuitive, because patients who experience repeat episodes of SBP might be expected to fare worse than those hit by SBP just once.

Dr. Bajaj also acknowledged the substantial confounding that distinguishes patients with cirrhosis receiving primary or secondary prophylaxis, and the difficulty of fully adjusting for all this confounding by statistical analyses. “There is selective bias for secondary prevention, and there is no way to correct for this,” he explained. Patients who need secondary prophylaxis have “weathered the storm” of a first episode of SBP, which might have exerted selection pressure, and might have triggered important immunologic changes, Dr. Bajaj suggested.

The findings also raised concerns about the appropriateness of existing antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP. The patients included in the study all received similar regimens regardless of whether they were on primary or secondary prophylaxis. Three-quarters of primary prophylaxis patients received a fluoroquinolone, as did 81% on secondary prophylaxis. All other patients received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. These regimens are aimed at preventing gram-negative infections; however, an increasing number of SBP episodes are caused by either gram-positive pathogens or strains of gram-negative bacteria or fungi resistant to standard antibiotics.

Clinicians “absolutely” need to rethink their approach to both primary and secondary prophylaxis, Dr. Bajaj said. “As fast as treatment evolves, bacteria evolve 20 times faster. We need to find ways to prevent infections without antibiotic prophylaxis, whatever that might be.”

The study used data collected prospectively from patients with cirrhosis at any of 12 U.S. and 2 Canadian centers that belonged to the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease. Among 2,731 cirrhotic patients admitted nonelectively, 492 (18%) were on antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of their admission, 305 for primary prophylaxis and 187 for secondary prophylaxis. Dr. Bajaj and his associates used both the baseline model for end-stage liver disease score and serum albumin level of each patient to focus on a group of 154 primary prophylaxis and 154 secondary prophylaxis patients who were similar by these two criteria. Despite this matching, the two subgroups showed statistically significant differences at the time of their index hospitalization for several important clinical measures.

The secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized within the previous 6 months, significantly more likely to be on treatment for hepatic encephalopathy at the time of their index admission, and significantly less likely to have systemic inflammatory response syndrome on admission.

Also, at the time of admission, secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have an infection of any type at a rate of 40%, compared with 24% among those on primary prophylaxis, as well as a significantly higher rate of SBP at 16%, compared with a 9% rate among the primary prophylaxis patients. During hospitalization, nosocomial SBP occurred significantly more often among the secondary prophylaxis patients at a rate of 6%, compared with a 0.5% rate among those on primary prophylaxis.

Despite these between-group differences, the average duration of hospitalization, and the average incidence of acute-on-chronic liver failure during follow-up out to 30 days post discharge was similar in the two subgroups. And the patients on secondary prophylaxis showed better outcomes by two important parameters: mortality during hospitalization and 30 days post discharge; and the incidence of ICU admission during hospitalization, which was significantly greater for primary prophylaxis patients at 31%, compared with 21% among the secondary prophylaxis patients, Dr. Bajaj reported.

Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

WASHINGTON –

The mortality rate during follow-up of cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on primary prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was 19%, compared with a 9% death rate among cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on secondary prophylaxis, Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Although the findings raised questions about the value of primary prophylaxis with an antibiotic in cirrhotic patients for preventing a first episode of SBP, secondary prophylaxis remains an important precaution.

“There is clear benefit from secondary prophylaxis; please use it. The data supporting it are robust,” said Dr. Bajaj, a hepatologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. In contrast, the evidence supporting benefits from primary prophylaxis is weaker, he said. The findings were also counterintuitive, because patients who experience repeat episodes of SBP might be expected to fare worse than those hit by SBP just once.

Dr. Bajaj also acknowledged the substantial confounding that distinguishes patients with cirrhosis receiving primary or secondary prophylaxis, and the difficulty of fully adjusting for all this confounding by statistical analyses. “There is selective bias for secondary prevention, and there is no way to correct for this,” he explained. Patients who need secondary prophylaxis have “weathered the storm” of a first episode of SBP, which might have exerted selection pressure, and might have triggered important immunologic changes, Dr. Bajaj suggested.

The findings also raised concerns about the appropriateness of existing antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP. The patients included in the study all received similar regimens regardless of whether they were on primary or secondary prophylaxis. Three-quarters of primary prophylaxis patients received a fluoroquinolone, as did 81% on secondary prophylaxis. All other patients received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. These regimens are aimed at preventing gram-negative infections; however, an increasing number of SBP episodes are caused by either gram-positive pathogens or strains of gram-negative bacteria or fungi resistant to standard antibiotics.

Clinicians “absolutely” need to rethink their approach to both primary and secondary prophylaxis, Dr. Bajaj said. “As fast as treatment evolves, bacteria evolve 20 times faster. We need to find ways to prevent infections without antibiotic prophylaxis, whatever that might be.”

The study used data collected prospectively from patients with cirrhosis at any of 12 U.S. and 2 Canadian centers that belonged to the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease. Among 2,731 cirrhotic patients admitted nonelectively, 492 (18%) were on antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of their admission, 305 for primary prophylaxis and 187 for secondary prophylaxis. Dr. Bajaj and his associates used both the baseline model for end-stage liver disease score and serum albumin level of each patient to focus on a group of 154 primary prophylaxis and 154 secondary prophylaxis patients who were similar by these two criteria. Despite this matching, the two subgroups showed statistically significant differences at the time of their index hospitalization for several important clinical measures.

The secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized within the previous 6 months, significantly more likely to be on treatment for hepatic encephalopathy at the time of their index admission, and significantly less likely to have systemic inflammatory response syndrome on admission.

Also, at the time of admission, secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have an infection of any type at a rate of 40%, compared with 24% among those on primary prophylaxis, as well as a significantly higher rate of SBP at 16%, compared with a 9% rate among the primary prophylaxis patients. During hospitalization, nosocomial SBP occurred significantly more often among the secondary prophylaxis patients at a rate of 6%, compared with a 0.5% rate among those on primary prophylaxis.

Despite these between-group differences, the average duration of hospitalization, and the average incidence of acute-on-chronic liver failure during follow-up out to 30 days post discharge was similar in the two subgroups. And the patients on secondary prophylaxis showed better outcomes by two important parameters: mortality during hospitalization and 30 days post discharge; and the incidence of ICU admission during hospitalization, which was significantly greater for primary prophylaxis patients at 31%, compared with 21% among the secondary prophylaxis patients, Dr. Bajaj reported.

Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial peritonitis showed limitations, especially for primary prophylaxis.

Major finding: Mortality was 19% among primary prophylaxis patients and 9% among secondary prophylaxis patients during hospitalization and 30 days following.

Study details: An analysis of data from 308 cirrhotic patients on antibiotic prophylaxis at 14 North American centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

Neuropilin-1 surpasses AFP as HCC diagnostic marker

A transmembrane glycoprotein labeled neuropilin-1 may be a diagnostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma.

In a series of experiments using HCC tissues and cell lines, as well as serum samples from patients with other malignancies or hepatitis, Jiafei Lin, MD, from Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues found that neuropilin-1 (NRP1) was up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and promotes tumor growth.

“Notably, the concentrations of serum NRP1 in the HCC patients were much higher than those of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cirrhosis, breast cancer, colon cancer, gastric cancer, and lung cancer patients,” they wrote in the journal Clinica Chimica Acta.

They also found that NRP1 has a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for HCC, and suggested that NRP1 could replace alpha fetoprotein (AFP) for early clinical diagnosis of HCC.

They first showed that NRP1 was directly regulated by TEAD, a family of transcription factors essential for developmental processes. The experiments in HCC cell lines showed that messenger RNA levels of NRP1 were increased when TEAD was overexpressed, and decreased when TEAD was knocked down. The experiments also suggested that TEAD binds directly to the promoter of NRP1 to stimulate its transcription in HCC cells.

The investigators then sought to demonstrate that NRP1 promotes tumor development and growth in HCC by testing expression of the protein in both normal liver and HCC tissue samples.

“NRP1 was found highly up-regulated in HCC tissues compared to normal tissues. Moreover, NRP1 was recruited to the membrane in HCC tissues, whereas this protein was not detected in normal tissues,” they wrote.

Furthermore, when they zeroed in on NRP1 using two different short hairpin RNAs to silence its expression, they found that knocking down NRP1 suppressed the viability of tumor cells and inhibited colony formation while also ramping up programmed cell death. Taken together, the data indicate that NRP1 is highly expressed in HCC and promotes tumorigenesis.

They then showed that NRP1 serum concentrations were significantly higher in samples from patients with HCC than in those from healthy individuals or patients with hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cirrhosis, breast cancer, colon cancer, gastric cancer, or lung cancer. In addition, higher NRP1 concentrations were significantly associated with higher HCC tumor stages.

The investigators then looked at the relationship between serum NRP1 and standard liver function markers in HCC, and found that NRP1 serum levels significantly correlated with gamma-glutamyltransferase, albumin, bile acid, ALT, AST, AFP, and prealbumin levels, but not total bilirubin or total protein levels.

Finally, they demonstrated that serum NRP1 is a better diagnostic marker than AFP, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.971, compared with 0.862 for AFP. At an NRP1 cutoff of 68 pg/mL, NRP1 had a sensitivity of 93.7%, and a specificity of 98.7%. Combining NRP1 with AFP only slightly improved the diagnostic accuracy.

“These results indicate that the single use of NRP1 is a promising choice for the diagnosis of HCC,” the investigators wrote.

They noted that the most of the study subjects were of Han Chinese origin, and that the results need to be validated in people of other ethnicities.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Potential conflicts of interest were not reported.

SOURCE: Lin J et al. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;485:158-65.

A transmembrane glycoprotein labeled neuropilin-1 may be a diagnostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma.

In a series of experiments using HCC tissues and cell lines, as well as serum samples from patients with other malignancies or hepatitis, Jiafei Lin, MD, from Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues found that neuropilin-1 (NRP1) was up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and promotes tumor growth.

“Notably, the concentrations of serum NRP1 in the HCC patients were much higher than those of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cirrhosis, breast cancer, colon cancer, gastric cancer, and lung cancer patients,” they wrote in the journal Clinica Chimica Acta.

They also found that NRP1 has a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for HCC, and suggested that NRP1 could replace alpha fetoprotein (AFP) for early clinical diagnosis of HCC.

They first showed that NRP1 was directly regulated by TEAD, a family of transcription factors essential for developmental processes. The experiments in HCC cell lines showed that messenger RNA levels of NRP1 were increased when TEAD was overexpressed, and decreased when TEAD was knocked down. The experiments also suggested that TEAD binds directly to the promoter of NRP1 to stimulate its transcription in HCC cells.

The investigators then sought to demonstrate that NRP1 promotes tumor development and growth in HCC by testing expression of the protein in both normal liver and HCC tissue samples.

“NRP1 was found highly up-regulated in HCC tissues compared to normal tissues. Moreover, NRP1 was recruited to the membrane in HCC tissues, whereas this protein was not detected in normal tissues,” they wrote.

Furthermore, when they zeroed in on NRP1 using two different short hairpin RNAs to silence its expression, they found that knocking down NRP1 suppressed the viability of tumor cells and inhibited colony formation while also ramping up programmed cell death. Taken together, the data indicate that NRP1 is highly expressed in HCC and promotes tumorigenesis.

They then showed that NRP1 serum concentrations were significantly higher in samples from patients with HCC than in those from healthy individuals or patients with hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cirrhosis, breast cancer, colon cancer, gastric cancer, or lung cancer. In addition, higher NRP1 concentrations were significantly associated with higher HCC tumor stages.

The investigators then looked at the relationship between serum NRP1 and standard liver function markers in HCC, and found that NRP1 serum levels significantly correlated with gamma-glutamyltransferase, albumin, bile acid, ALT, AST, AFP, and prealbumin levels, but not total bilirubin or total protein levels.

Finally, they demonstrated that serum NRP1 is a better diagnostic marker than AFP, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.971, compared with 0.862 for AFP. At an NRP1 cutoff of 68 pg/mL, NRP1 had a sensitivity of 93.7%, and a specificity of 98.7%. Combining NRP1 with AFP only slightly improved the diagnostic accuracy.

“These results indicate that the single use of NRP1 is a promising choice for the diagnosis of HCC,” the investigators wrote.

They noted that the most of the study subjects were of Han Chinese origin, and that the results need to be validated in people of other ethnicities.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Potential conflicts of interest were not reported.

SOURCE: Lin J et al. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;485:158-65.

A transmembrane glycoprotein labeled neuropilin-1 may be a diagnostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma.