User login

Dodging potholes from cancer care to hospice transitions

I’m often in the position of caring for patients after they’ve stopped active cancer treatments, but before they’ve made the decision to enroll in hospice. They remain under my care until they feel emotionally ready, or until their care needs have escalated to the point in which hospice is unavoidable.

Jenny, a mom in her 50s with metastatic pancreatic cancer, stopped coming to the clinic. She lived about 40 minutes away from the clinic and was no longer receiving treatment. The car rides were painful and difficult for her. I held weekly video visits with her for 2 months before she eventually went to hospice and passed away. Before she died, she shared with me her sadness that her oncologist – who had taken care of her for 3 years – had “washed his hands of [me].” She rarely heard from him after their final conversation in the clinic when he informed her that she was no longer a candidate for further therapy. The sense of abandonment Jenny described was visceral and devastating. With her permission, I let her oncology team know how she felt and they reached out to her just 1 week before her death. After she died, her husband told me how meaningful it had been for the whole family to hear from Jenny’s oncologist who told them that she had done everything possible to fight her cancer and that “no stone was left unturned.” Her husband felt this final conversation provided Jenny with the closure she needed to pass away peacefully.

Transitioning from active therapy to symptom management

Switching gears from an all-out pursuit of active therapy to focusing on cancer symptoms is often a scary transition for patients and their families. The transition is often viewed as a movement away from hope and optimism to “giving up the fight.” Whether you agree with the warrior language or not, many patients still describe their journey in these terms and thus, experience enrollment in hospice as a sense of having failed.

The sense of failure can be compounded by feelings of abandonment by oncology providers when they are referred without much guidance or continuity through the hospice enrollment process. Unfortunately, the consequences of suboptimal hospice transitions can be damaging, especially for the mental health and well-being of the patient and their surviving loved ones.

When managed poorly, hospice transitions can easily lead to patient and family harm, which is a claim supported by research. A qualitative study published in 2019 included 92 caregivers of patients with terminal cancer. The authors found three common pathways for end-of-life transitions – a frictionless transition in which the patient and family are well prepared in advance by their oncologist; a more turbulent transition in which patient and family had direct conversations with their oncologist about the incurability of the disease and the lack of efficacy of further treatments, but were given no guidance on prognosis; and a third type of transition marked by abrupt shifts toward end-of-life care occurring in extremis and typically in the hospital.

In the latter two groups, caregivers felt their loved ones died very quickly after stopping treatment, taking them by surprise and leaving them rushing to put end-of-life care plans in place without much support from their oncologists. In the last group, caregivers shared they received their first prognostic information from the hospital or ICU doctor caring for their actively dying loved one, leaving them with a sense of anger and betrayal toward their oncologist for allowing them to be so ill-prepared.

A Japanese survey published in 2018 in The Oncologist of families of cancer patients who had passed away under hospice care over a 2-year period (2012-2014), found that about one-quarter felt abandoned by oncologists. Several factors that were associated with feeling either more or less abandonment. Spouses of patients, patients aged less than 60 years, and patients whose oncologists informed them that there was “nothing more to do” felt more abandoned by oncologists; whereas families for whom the oncologist provided reassurance about the trajectory of care, recommended hospice, and engaged with a palliative care team felt less abandoned by oncologists. Families who felt more abandoned had higher levels of depression and grief when measured with standardized instruments.

‘Don’t just put in the hospice order and walk away’

Fortunately, there are a few low-resource interventions that can improve the quality of care-to-hospice transitions and prevent the sense of abandonment felt by many patients and families.

First, don’t just put in the hospice order and walk away. Designate a staffer in your office to contact hospice directly, ensure all medical records are faxed and received, and update the patient and family on this progress throughout the transition. Taking care of details like these ensures the patient enrolls in hospice in a timely manner and reduces the chance the patient, who is likely to be quite sick at this point, will end up in the hospital despite your best efforts to get hospice involved.

Make sure the patient and family understand that you are still their oncologist and still available to them. If they want to continue care with you, have them name you as the “non–hospice-attending physician” so that you can continue to bill for telemedicine and office visits using the terminal diagnosis (with a billing modifier). This does not mean that you will be expected to manage the patient’s hospice problem list or respond to hospice nurse calls at 2 a.m. – the hospice doctor will still do this. It just ensures that patients do not receive a bill if you continue to see them.

If ongoing office or video visits are too much for the patient and family, consider assigning a member of your team to call the patient and family on a weekly basis to check in and offer support. A small 2018 pilot study aimed at improving communication found that when caregivers of advanced cancer patients transitioning to hospice received weekly supportive phone calls by a member of their oncology team (typically a nurse or nurse practitioner), they felt emotionally supported, had good continuity of care throughout the hospice enrollment, and appreciated the ability to have closure with their oncology team. In other words, a sense of abandonment was prevented and the patient-provider relationship was actually deepened through the transition.

These suggestions are not rocket science – they are simple, obvious ways to try to restore patient-centeredness to a transition that for providers can seem routine, but for patients and families is often the first time they have confronted the reality that death is approaching. That reality is terrifying and overwhelming. Patients and caregivers need our support more during hospice transitions than at any other point during their cancer journey – except perhaps at diagnosis.

As with Jenny, my patient who felt abandoned, all it took was a single call by her oncology team to restore the trust and heal the sense of feeling forsaken by the people who cared for her for years. Sometimes, even just one more phone call can feel like a lot to a chronically overburdened provider – but what a difference a simple call can make.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

I’m often in the position of caring for patients after they’ve stopped active cancer treatments, but before they’ve made the decision to enroll in hospice. They remain under my care until they feel emotionally ready, or until their care needs have escalated to the point in which hospice is unavoidable.

Jenny, a mom in her 50s with metastatic pancreatic cancer, stopped coming to the clinic. She lived about 40 minutes away from the clinic and was no longer receiving treatment. The car rides were painful and difficult for her. I held weekly video visits with her for 2 months before she eventually went to hospice and passed away. Before she died, she shared with me her sadness that her oncologist – who had taken care of her for 3 years – had “washed his hands of [me].” She rarely heard from him after their final conversation in the clinic when he informed her that she was no longer a candidate for further therapy. The sense of abandonment Jenny described was visceral and devastating. With her permission, I let her oncology team know how she felt and they reached out to her just 1 week before her death. After she died, her husband told me how meaningful it had been for the whole family to hear from Jenny’s oncologist who told them that she had done everything possible to fight her cancer and that “no stone was left unturned.” Her husband felt this final conversation provided Jenny with the closure she needed to pass away peacefully.

Transitioning from active therapy to symptom management

Switching gears from an all-out pursuit of active therapy to focusing on cancer symptoms is often a scary transition for patients and their families. The transition is often viewed as a movement away from hope and optimism to “giving up the fight.” Whether you agree with the warrior language or not, many patients still describe their journey in these terms and thus, experience enrollment in hospice as a sense of having failed.

The sense of failure can be compounded by feelings of abandonment by oncology providers when they are referred without much guidance or continuity through the hospice enrollment process. Unfortunately, the consequences of suboptimal hospice transitions can be damaging, especially for the mental health and well-being of the patient and their surviving loved ones.

When managed poorly, hospice transitions can easily lead to patient and family harm, which is a claim supported by research. A qualitative study published in 2019 included 92 caregivers of patients with terminal cancer. The authors found three common pathways for end-of-life transitions – a frictionless transition in which the patient and family are well prepared in advance by their oncologist; a more turbulent transition in which patient and family had direct conversations with their oncologist about the incurability of the disease and the lack of efficacy of further treatments, but were given no guidance on prognosis; and a third type of transition marked by abrupt shifts toward end-of-life care occurring in extremis and typically in the hospital.

In the latter two groups, caregivers felt their loved ones died very quickly after stopping treatment, taking them by surprise and leaving them rushing to put end-of-life care plans in place without much support from their oncologists. In the last group, caregivers shared they received their first prognostic information from the hospital or ICU doctor caring for their actively dying loved one, leaving them with a sense of anger and betrayal toward their oncologist for allowing them to be so ill-prepared.

A Japanese survey published in 2018 in The Oncologist of families of cancer patients who had passed away under hospice care over a 2-year period (2012-2014), found that about one-quarter felt abandoned by oncologists. Several factors that were associated with feeling either more or less abandonment. Spouses of patients, patients aged less than 60 years, and patients whose oncologists informed them that there was “nothing more to do” felt more abandoned by oncologists; whereas families for whom the oncologist provided reassurance about the trajectory of care, recommended hospice, and engaged with a palliative care team felt less abandoned by oncologists. Families who felt more abandoned had higher levels of depression and grief when measured with standardized instruments.

‘Don’t just put in the hospice order and walk away’

Fortunately, there are a few low-resource interventions that can improve the quality of care-to-hospice transitions and prevent the sense of abandonment felt by many patients and families.

First, don’t just put in the hospice order and walk away. Designate a staffer in your office to contact hospice directly, ensure all medical records are faxed and received, and update the patient and family on this progress throughout the transition. Taking care of details like these ensures the patient enrolls in hospice in a timely manner and reduces the chance the patient, who is likely to be quite sick at this point, will end up in the hospital despite your best efforts to get hospice involved.

Make sure the patient and family understand that you are still their oncologist and still available to them. If they want to continue care with you, have them name you as the “non–hospice-attending physician” so that you can continue to bill for telemedicine and office visits using the terminal diagnosis (with a billing modifier). This does not mean that you will be expected to manage the patient’s hospice problem list or respond to hospice nurse calls at 2 a.m. – the hospice doctor will still do this. It just ensures that patients do not receive a bill if you continue to see them.

If ongoing office or video visits are too much for the patient and family, consider assigning a member of your team to call the patient and family on a weekly basis to check in and offer support. A small 2018 pilot study aimed at improving communication found that when caregivers of advanced cancer patients transitioning to hospice received weekly supportive phone calls by a member of their oncology team (typically a nurse or nurse practitioner), they felt emotionally supported, had good continuity of care throughout the hospice enrollment, and appreciated the ability to have closure with their oncology team. In other words, a sense of abandonment was prevented and the patient-provider relationship was actually deepened through the transition.

These suggestions are not rocket science – they are simple, obvious ways to try to restore patient-centeredness to a transition that for providers can seem routine, but for patients and families is often the first time they have confronted the reality that death is approaching. That reality is terrifying and overwhelming. Patients and caregivers need our support more during hospice transitions than at any other point during their cancer journey – except perhaps at diagnosis.

As with Jenny, my patient who felt abandoned, all it took was a single call by her oncology team to restore the trust and heal the sense of feeling forsaken by the people who cared for her for years. Sometimes, even just one more phone call can feel like a lot to a chronically overburdened provider – but what a difference a simple call can make.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

I’m often in the position of caring for patients after they’ve stopped active cancer treatments, but before they’ve made the decision to enroll in hospice. They remain under my care until they feel emotionally ready, or until their care needs have escalated to the point in which hospice is unavoidable.

Jenny, a mom in her 50s with metastatic pancreatic cancer, stopped coming to the clinic. She lived about 40 minutes away from the clinic and was no longer receiving treatment. The car rides were painful and difficult for her. I held weekly video visits with her for 2 months before she eventually went to hospice and passed away. Before she died, she shared with me her sadness that her oncologist – who had taken care of her for 3 years – had “washed his hands of [me].” She rarely heard from him after their final conversation in the clinic when he informed her that she was no longer a candidate for further therapy. The sense of abandonment Jenny described was visceral and devastating. With her permission, I let her oncology team know how she felt and they reached out to her just 1 week before her death. After she died, her husband told me how meaningful it had been for the whole family to hear from Jenny’s oncologist who told them that she had done everything possible to fight her cancer and that “no stone was left unturned.” Her husband felt this final conversation provided Jenny with the closure she needed to pass away peacefully.

Transitioning from active therapy to symptom management

Switching gears from an all-out pursuit of active therapy to focusing on cancer symptoms is often a scary transition for patients and their families. The transition is often viewed as a movement away from hope and optimism to “giving up the fight.” Whether you agree with the warrior language or not, many patients still describe their journey in these terms and thus, experience enrollment in hospice as a sense of having failed.

The sense of failure can be compounded by feelings of abandonment by oncology providers when they are referred without much guidance or continuity through the hospice enrollment process. Unfortunately, the consequences of suboptimal hospice transitions can be damaging, especially for the mental health and well-being of the patient and their surviving loved ones.

When managed poorly, hospice transitions can easily lead to patient and family harm, which is a claim supported by research. A qualitative study published in 2019 included 92 caregivers of patients with terminal cancer. The authors found three common pathways for end-of-life transitions – a frictionless transition in which the patient and family are well prepared in advance by their oncologist; a more turbulent transition in which patient and family had direct conversations with their oncologist about the incurability of the disease and the lack of efficacy of further treatments, but were given no guidance on prognosis; and a third type of transition marked by abrupt shifts toward end-of-life care occurring in extremis and typically in the hospital.

In the latter two groups, caregivers felt their loved ones died very quickly after stopping treatment, taking them by surprise and leaving them rushing to put end-of-life care plans in place without much support from their oncologists. In the last group, caregivers shared they received their first prognostic information from the hospital or ICU doctor caring for their actively dying loved one, leaving them with a sense of anger and betrayal toward their oncologist for allowing them to be so ill-prepared.

A Japanese survey published in 2018 in The Oncologist of families of cancer patients who had passed away under hospice care over a 2-year period (2012-2014), found that about one-quarter felt abandoned by oncologists. Several factors that were associated with feeling either more or less abandonment. Spouses of patients, patients aged less than 60 years, and patients whose oncologists informed them that there was “nothing more to do” felt more abandoned by oncologists; whereas families for whom the oncologist provided reassurance about the trajectory of care, recommended hospice, and engaged with a palliative care team felt less abandoned by oncologists. Families who felt more abandoned had higher levels of depression and grief when measured with standardized instruments.

‘Don’t just put in the hospice order and walk away’

Fortunately, there are a few low-resource interventions that can improve the quality of care-to-hospice transitions and prevent the sense of abandonment felt by many patients and families.

First, don’t just put in the hospice order and walk away. Designate a staffer in your office to contact hospice directly, ensure all medical records are faxed and received, and update the patient and family on this progress throughout the transition. Taking care of details like these ensures the patient enrolls in hospice in a timely manner and reduces the chance the patient, who is likely to be quite sick at this point, will end up in the hospital despite your best efforts to get hospice involved.

Make sure the patient and family understand that you are still their oncologist and still available to them. If they want to continue care with you, have them name you as the “non–hospice-attending physician” so that you can continue to bill for telemedicine and office visits using the terminal diagnosis (with a billing modifier). This does not mean that you will be expected to manage the patient’s hospice problem list or respond to hospice nurse calls at 2 a.m. – the hospice doctor will still do this. It just ensures that patients do not receive a bill if you continue to see them.

If ongoing office or video visits are too much for the patient and family, consider assigning a member of your team to call the patient and family on a weekly basis to check in and offer support. A small 2018 pilot study aimed at improving communication found that when caregivers of advanced cancer patients transitioning to hospice received weekly supportive phone calls by a member of their oncology team (typically a nurse or nurse practitioner), they felt emotionally supported, had good continuity of care throughout the hospice enrollment, and appreciated the ability to have closure with their oncology team. In other words, a sense of abandonment was prevented and the patient-provider relationship was actually deepened through the transition.

These suggestions are not rocket science – they are simple, obvious ways to try to restore patient-centeredness to a transition that for providers can seem routine, but for patients and families is often the first time they have confronted the reality that death is approaching. That reality is terrifying and overwhelming. Patients and caregivers need our support more during hospice transitions than at any other point during their cancer journey – except perhaps at diagnosis.

As with Jenny, my patient who felt abandoned, all it took was a single call by her oncology team to restore the trust and heal the sense of feeling forsaken by the people who cared for her for years. Sometimes, even just one more phone call can feel like a lot to a chronically overburdened provider – but what a difference a simple call can make.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

Clinical chest images power up survival prediction in lung cancer

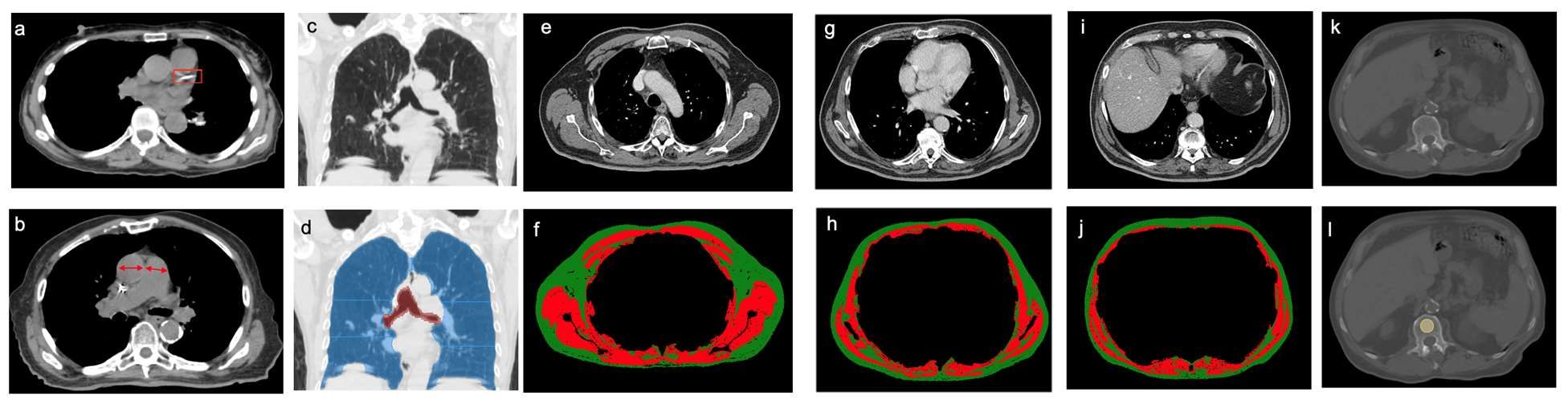

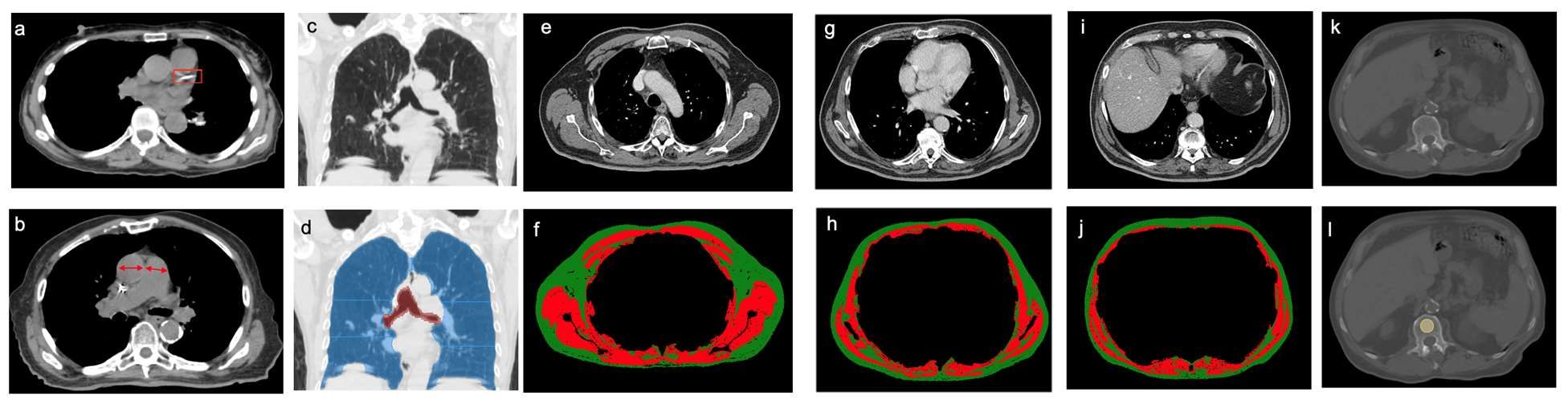

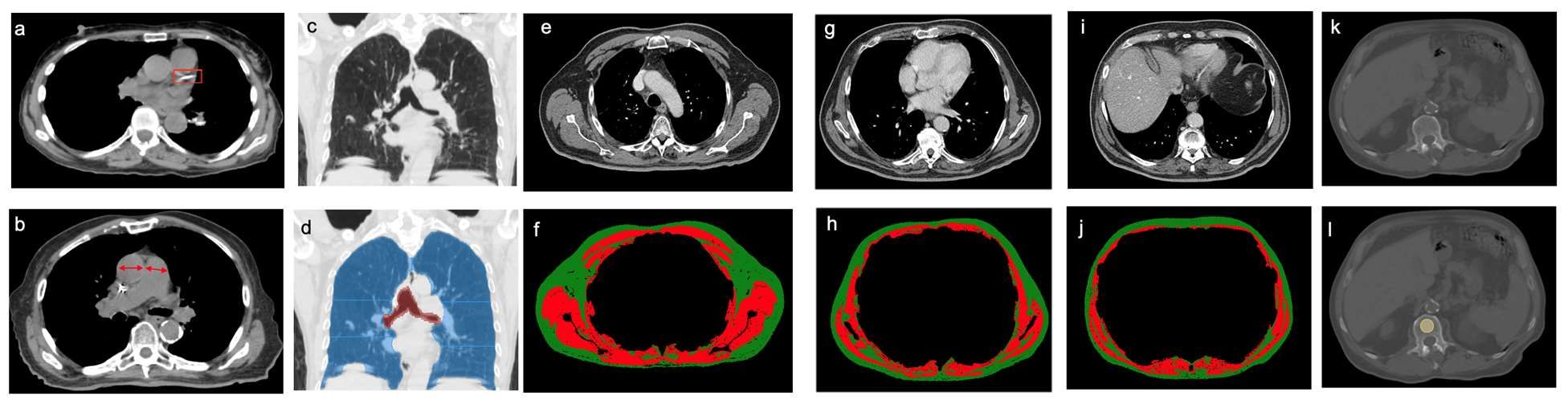

In patients with stage I lung cancer, adding noncancerous features from CT chest imaging predicts overall survival better than clinical characteristics alone, according to a paper published online in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

Modeling that incorporates noncancerous imaging features captured on chest computed tomography (CT) along with clinical features, when calculated before stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is administered, improves survival prediction, compared with modeling that relies only on clinical features, the authors report.

“The focus of the study was to look at the environment in which the cancer lives,” said senior author Florian J. Fintelmann, MD, radiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “This is looking at parameters like the aortic diameter, body composition – that is, the quantification and characterization of adipose tissue and muscle – coronary artery calcifications, and emphysema quantification.”

CT images are used by radiation oncologists to determine where the radiation should be delivered. “There is more information from these images that we can utilize,” he said.

Survival estimates in patients with state I lung cancer now rely on biological age, ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score, and the presence of comorbidities, Dr. Fintelmann said.

This retrospective investigation involved 282 patients with a median age of 75 years. There were 168 women and 114 men. All patients had stage I lung cancer and were treated with SBRT between January 2009 and June 2017.

Investigators analyzed pre-treatment chest images with CT. They assessed coronary artery calcium (CAC) score (see above image), pulmonary artery (PA)-to-aorta ratio, emphysema, and several measures of body composition (skeletal muscle and adipose tissue). They developed a statistical model to link clinical and imaging features with overall survival.

An elevated CAC score (11-399: HR, 1.83 [95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.91]; ≥ 400: HR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.01-2.63]), increased PA-to-aorta ratio (HR, 1.33 [95% CI, 1.16-1.52], per 0.1-unit increase) and decreased thoracic skeletal muscle (HR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.79-0.98], per 10 cm2/m2 increase) were independently associated with shorter overall survival, investigators observed.

In addition, 5-year overall survival was superior for the model that included clinical and imaging features and inferior for the model restricted to only clinical features. Of all features, the one that emerged the most predictive of overall survival was PA-to-aorta ratio.

In this single-center study of stage I lung cancer patients who were undergoing SBRT, increased CAC score, increased PA-to-aorta ratio, and decreased thoracic skeletal muscle index were independently predictive of poorer overall survival.

“Our modeling shows that these imaging features add so much more [to predicting overall survival],” Dr. Fintelmann said. “The strength of this study is that we show the utility [of the model] and how it exceeds the clinical risk prediction that is currently standard of care. We think this will benefit patients in terms of being able to counsel them and better advise them on their medical decisions.”

This proof-of-concept investigation requires external validation, Dr. Fintelmann stressed. “External data for validation is the next step,” he said, noting he and co-investigators welcome data input from other investigators.

Elsie Nguyen, MD, FRCPC, FNASCI, associate professor of radiology, University of Toronto, responded by email that the study shows that imaging features supplement clinical data in predicting overall survival.

“This study demonstrates the value of extracting non–cancer related computed tomography imaging features to build a model that can better predict overall survival as compared to clinical parameters alone (such as age, performance status and co-morbidities) for stage I lung cancer patients treated with SBRT,” Dr. Nguyen wrote.

“Coronary artery calcium score, pulmonary artery-to-aorta ratio, and sarcopenia independently predicted overall survival,” she wrote. “These results are not surprising, as the prognostic value of each of these imaging features has already been established in the literature.”

Dr. Nguyen pointed out the power in the sum of these imaging features to predict overall survival.

“However, the results of this study demonstrate promising results supportive of the notion that combining clinical and imaging data points can help build a more accurate prediction model for overall survival,” she wrote. “This is analogous to the Brock University (in St. Catharines, Ontario) calculator for solitary pulmonary nodules that calculates malignancy risk based on both clinical and imaging data points. However, external validation of these study results at other centers is first required.”

Dr. Fintelmann and Dr. Nguyen have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with stage I lung cancer, adding noncancerous features from CT chest imaging predicts overall survival better than clinical characteristics alone, according to a paper published online in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

Modeling that incorporates noncancerous imaging features captured on chest computed tomography (CT) along with clinical features, when calculated before stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is administered, improves survival prediction, compared with modeling that relies only on clinical features, the authors report.

“The focus of the study was to look at the environment in which the cancer lives,” said senior author Florian J. Fintelmann, MD, radiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “This is looking at parameters like the aortic diameter, body composition – that is, the quantification and characterization of adipose tissue and muscle – coronary artery calcifications, and emphysema quantification.”

CT images are used by radiation oncologists to determine where the radiation should be delivered. “There is more information from these images that we can utilize,” he said.

Survival estimates in patients with state I lung cancer now rely on biological age, ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score, and the presence of comorbidities, Dr. Fintelmann said.

This retrospective investigation involved 282 patients with a median age of 75 years. There were 168 women and 114 men. All patients had stage I lung cancer and were treated with SBRT between January 2009 and June 2017.

Investigators analyzed pre-treatment chest images with CT. They assessed coronary artery calcium (CAC) score (see above image), pulmonary artery (PA)-to-aorta ratio, emphysema, and several measures of body composition (skeletal muscle and adipose tissue). They developed a statistical model to link clinical and imaging features with overall survival.

An elevated CAC score (11-399: HR, 1.83 [95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.91]; ≥ 400: HR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.01-2.63]), increased PA-to-aorta ratio (HR, 1.33 [95% CI, 1.16-1.52], per 0.1-unit increase) and decreased thoracic skeletal muscle (HR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.79-0.98], per 10 cm2/m2 increase) were independently associated with shorter overall survival, investigators observed.

In addition, 5-year overall survival was superior for the model that included clinical and imaging features and inferior for the model restricted to only clinical features. Of all features, the one that emerged the most predictive of overall survival was PA-to-aorta ratio.

In this single-center study of stage I lung cancer patients who were undergoing SBRT, increased CAC score, increased PA-to-aorta ratio, and decreased thoracic skeletal muscle index were independently predictive of poorer overall survival.

“Our modeling shows that these imaging features add so much more [to predicting overall survival],” Dr. Fintelmann said. “The strength of this study is that we show the utility [of the model] and how it exceeds the clinical risk prediction that is currently standard of care. We think this will benefit patients in terms of being able to counsel them and better advise them on their medical decisions.”

This proof-of-concept investigation requires external validation, Dr. Fintelmann stressed. “External data for validation is the next step,” he said, noting he and co-investigators welcome data input from other investigators.

Elsie Nguyen, MD, FRCPC, FNASCI, associate professor of radiology, University of Toronto, responded by email that the study shows that imaging features supplement clinical data in predicting overall survival.

“This study demonstrates the value of extracting non–cancer related computed tomography imaging features to build a model that can better predict overall survival as compared to clinical parameters alone (such as age, performance status and co-morbidities) for stage I lung cancer patients treated with SBRT,” Dr. Nguyen wrote.

“Coronary artery calcium score, pulmonary artery-to-aorta ratio, and sarcopenia independently predicted overall survival,” she wrote. “These results are not surprising, as the prognostic value of each of these imaging features has already been established in the literature.”

Dr. Nguyen pointed out the power in the sum of these imaging features to predict overall survival.

“However, the results of this study demonstrate promising results supportive of the notion that combining clinical and imaging data points can help build a more accurate prediction model for overall survival,” she wrote. “This is analogous to the Brock University (in St. Catharines, Ontario) calculator for solitary pulmonary nodules that calculates malignancy risk based on both clinical and imaging data points. However, external validation of these study results at other centers is first required.”

Dr. Fintelmann and Dr. Nguyen have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with stage I lung cancer, adding noncancerous features from CT chest imaging predicts overall survival better than clinical characteristics alone, according to a paper published online in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

Modeling that incorporates noncancerous imaging features captured on chest computed tomography (CT) along with clinical features, when calculated before stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is administered, improves survival prediction, compared with modeling that relies only on clinical features, the authors report.

“The focus of the study was to look at the environment in which the cancer lives,” said senior author Florian J. Fintelmann, MD, radiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “This is looking at parameters like the aortic diameter, body composition – that is, the quantification and characterization of adipose tissue and muscle – coronary artery calcifications, and emphysema quantification.”

CT images are used by radiation oncologists to determine where the radiation should be delivered. “There is more information from these images that we can utilize,” he said.

Survival estimates in patients with state I lung cancer now rely on biological age, ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score, and the presence of comorbidities, Dr. Fintelmann said.

This retrospective investigation involved 282 patients with a median age of 75 years. There were 168 women and 114 men. All patients had stage I lung cancer and were treated with SBRT between January 2009 and June 2017.

Investigators analyzed pre-treatment chest images with CT. They assessed coronary artery calcium (CAC) score (see above image), pulmonary artery (PA)-to-aorta ratio, emphysema, and several measures of body composition (skeletal muscle and adipose tissue). They developed a statistical model to link clinical and imaging features with overall survival.

An elevated CAC score (11-399: HR, 1.83 [95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.91]; ≥ 400: HR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.01-2.63]), increased PA-to-aorta ratio (HR, 1.33 [95% CI, 1.16-1.52], per 0.1-unit increase) and decreased thoracic skeletal muscle (HR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.79-0.98], per 10 cm2/m2 increase) were independently associated with shorter overall survival, investigators observed.

In addition, 5-year overall survival was superior for the model that included clinical and imaging features and inferior for the model restricted to only clinical features. Of all features, the one that emerged the most predictive of overall survival was PA-to-aorta ratio.

In this single-center study of stage I lung cancer patients who were undergoing SBRT, increased CAC score, increased PA-to-aorta ratio, and decreased thoracic skeletal muscle index were independently predictive of poorer overall survival.

“Our modeling shows that these imaging features add so much more [to predicting overall survival],” Dr. Fintelmann said. “The strength of this study is that we show the utility [of the model] and how it exceeds the clinical risk prediction that is currently standard of care. We think this will benefit patients in terms of being able to counsel them and better advise them on their medical decisions.”

This proof-of-concept investigation requires external validation, Dr. Fintelmann stressed. “External data for validation is the next step,” he said, noting he and co-investigators welcome data input from other investigators.

Elsie Nguyen, MD, FRCPC, FNASCI, associate professor of radiology, University of Toronto, responded by email that the study shows that imaging features supplement clinical data in predicting overall survival.

“This study demonstrates the value of extracting non–cancer related computed tomography imaging features to build a model that can better predict overall survival as compared to clinical parameters alone (such as age, performance status and co-morbidities) for stage I lung cancer patients treated with SBRT,” Dr. Nguyen wrote.

“Coronary artery calcium score, pulmonary artery-to-aorta ratio, and sarcopenia independently predicted overall survival,” she wrote. “These results are not surprising, as the prognostic value of each of these imaging features has already been established in the literature.”

Dr. Nguyen pointed out the power in the sum of these imaging features to predict overall survival.

“However, the results of this study demonstrate promising results supportive of the notion that combining clinical and imaging data points can help build a more accurate prediction model for overall survival,” she wrote. “This is analogous to the Brock University (in St. Catharines, Ontario) calculator for solitary pulmonary nodules that calculates malignancy risk based on both clinical and imaging data points. However, external validation of these study results at other centers is first required.”

Dr. Fintelmann and Dr. Nguyen have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Recent Lung Cancer Trial Results, May 2022

In a European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Plenary session, Dr Paz-Ares and colleagues presented interim analysis of the PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 study of adjuvant pembrolizumab. In this triple-blind phase 3 trial, 1177 patients with stage IB (tumor ≥ 4 cm) to IIIA non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (per American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC], version 7) were randomly assigned to receive pembrolizumab vs placebo. The dual primary endpoints were disease-free survival (DFS) in the overall population and in the population with high programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (tumor proportion score [TPS] ≥ 50%). The study met its primary endpoint where improved DFS was observed in the overall population that included lung cancers, whether they were PD-L1–negative (TPS = 0%) or –positive (TPS ≥ 1%) (53.6 months in the pembrolizumab group vs 42.0 months in the placebo group [hazard ratio (HR) 0.76; P = .0014]). Overall survival data are not yet clear. Of note, in the interim analysis presented, the subset of patients with high PD-L1 NSCLC (TPS ≥ 50%) did not show a DFS benefit whereas in other adjuvant and neoadjuvant studies, such as IMpower010 and CheckMate 816, the subset of high PD-L1 patients appeared to derive the most benefit. The results from the high PD-L1 subset and other subsets may change with future updated analyses as more events occur. The major co-primary endpoint was clearly met with the overall population clearly showing a positive DFS benefit. The results of the PEARLS trial adds to the current landscape of systemic treatment of early-stage NSCLC where neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for stage IB (≥ 4 cm) to IIIA resected NSCLC regardless of level of PD-L1 expression, as is adjuvant atezolizumab after consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients that are PD-L1–positive (≥ 1%) on the basis of a DFS benefit observed in this population.1,2 For the future, it is important to see if the DFS benefit observed in these studies translates into a meaningful overall survival benefit.

Plasma cfDNA Levels as a Prognostic Marker in ALK+ NSCLC in the ALEX Trial

The ALEX trial is a pivotal global phase 3 randomized control trial that demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) with the next-generation ALK inhibitor alectinib compared with the first-generation ALK inhibitor crizotinib as first-line treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC (HR 0.43; 95% CI 0.32-0.58; median PFS 34.8 vs 10.9 months crizotinib).3 In a study recently published in Clinical Cancer Research, Dr Dziadziuszko and colleagues retrospectively assessed the prognostic value of baseline cell-free DNA (cfDNA) levels in patients treated in the ALEX trial. Baseline plasma for cfDNA was quantified by the Foundation ACT next-generation sequencing assay. Clinical outcomes were assessed by quantitative cfDNA level stratified by the median value. In both the alectinib and crizotinib treatment arms, patients with cfDNA levels above the median were more likely to experience disease progression (alectinib adjusted HR 2.04; 95% CI 1.07-3.89; P = .03 and crizotinib adjusted HR 1.83; 95% CI 1.11-3.00, P = .016). Though survival data are incomplete, the study also suggested survival probability was lower when baseline cfDNA was above the median in both the alectinib and crizotinib treatment arms. Regardless of cfDNA levels, PFS was improved with alectinib compared with crizotinib. Previous studies have shown the value of cfDNA analysis at the time of progression to guide further treatment and target resistance mechanisms to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), such as G1202R, or bypass tract pathways, such as MET amplification.4,5 Assessment of the EML4-ALK variant type (V1 vs V3) has been shown to associate with certain types of resistance mechanisms (ie, on target ALK mutations, such as G1202R in V3) and clinical activity of specific ALK TKI (V3 > V1 for PFS with lorlatinib).6 This study examining baseline cfDNA levels and clinical outcomes on the ALEX trial shows the potential utility of baseline cfDNA levels as a prognostic factor for ALK TKI.

Lorlatinib in ROS1-Rearranged NSCLC After Progression on Prior ROS1 TKI

ROS1 rearrangements represent about 1.5% of lung adenocarcinoma. In advanced disease, both crizotinib and entrectinib are FDA-approved as agents targeting ROS1 with robust PFS. The third-generation TKI lorlatinib is approved and has substantial activity in ALK-rearranged NSCLC. In a recently published retrospective real-world cohort study by Girard and colleagues (LORLATU), 80 patients with ROS1-rearranged NSCLC were treated with lorlatinib as second-line treatment or beyond and after failure on at least one prior ROS1 TKI. Median PFS was 7.1 months (95% CI 5.0-9.9) and median overall survival was 19.6 months (95% CI 12.3-27.5). The overall response rate was 45% and the disease control rate was 82%. The central nervous system response rate was 72%. There were no new safety signals. This retrospective cohort study demonstrates that lorlatinib is a major targeted therapy treatment option in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC.

Checkmate 816: Neoadjuvant Nivolumab Plus Chemotherapy in Resectable NSCLC

In this open-label, phase 3 trial, 358 patients with stage IB (T ³ 4cm) to IIIA (per AJCC v7) resectable NSCLC were randomized 1:1 to receive nivolumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy or platinum-based chemotherapy alone for three cycles, followed by surgical resection. The primary endpoints were event-free survival (EFS) and pathological complete response (pCR) (0% viable tumor in resected lung and lymph nodes), both evaluated by blinded independent review. The median EFS was significantly increased in the nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm compared to chemotherapy alone: 31.6 months (95% CI 30.2 to not reached) vs 20.8 months (95% CI 14.0 to 26.7) (HR 0.63; 97.38% CI 0.43 to 0.91; P = .005). pCR rate was also increased in the nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm (24.0% vs 2.2%, respectively; odds ratio 13.94; 99% CI 3.49 to 55.75; P < .001). At the first prespecified interim analysis, the hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (99.67% CI 0.30 to 1.07), which currently does not meet the criterion for statistical significance. Of the randomized patients, 83.2% of those in the nivolumab-plus chemotherapy group and 75.4% of those in the chemotherapy-alone group were able to undergo surgery. Grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 33.5% of the patients in the nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy group and in 36.9% of those in the chemotherapy-alone group. In an exploratory analysis, EFS was longer in patients with pCR than patients without a pCR. In a subset analysis, patients with high PD-L1 expression (³50%) stood out in terms of particular benefit (HR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10–0.61). The Checkmate 816 trial is a landmark study. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy represents a new standard of care in the systemic treatment of resectable NSCLC that is at a stage that warrants systemic treatment. It is FDA approved regardless of PD-L1 expression level including PD-L1 negative (0%) patients.2 Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy is also an FDA-approved treatment option for patients that are PD-L1 positive (³1%) based upon the IMpower 010 study.1 It will be important to assess the overall survival benefit as the trial data matures, which seems to be trending in the right direction. Additional neoadjuvant clinical trials with chemoimmunotherapy have completed accrual and some of these trials also continued PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in the adjuvant setting after surgery. An important question for the future is if combination of PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint blockade with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting along with continuation of immunotherapy in the adjuvant setting post-surgery will further improve clinical outcomes.

References

- Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-57. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02098-5 Source

- Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. April 11, 2022. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2202170 Source

- Mok T, Camige DR, Gadgeel SM, et al. Updated overall survival and final progression-free survival data for patients with treatment-naive advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer in the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1056-1064. Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.478 Source

- Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Chiari R, et al. Lorlatinib in advanced ROS1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1691-1701. Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30655-2 Source

- Lawrence MN, Tamen RM, Martinez P, et al. SPACEWALK: A remote participation study of ALK resistance leveraging plasma cell-free DNA genotyping. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;2:100151. Doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100151 Source

- Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Yoda S, et al. Impact of EML4-ALK variant on resistance mechanisms and clinical outcomes in ALK-positive lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1199-1206. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2294 Source

In a European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Plenary session, Dr Paz-Ares and colleagues presented interim analysis of the PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 study of adjuvant pembrolizumab. In this triple-blind phase 3 trial, 1177 patients with stage IB (tumor ≥ 4 cm) to IIIA non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (per American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC], version 7) were randomly assigned to receive pembrolizumab vs placebo. The dual primary endpoints were disease-free survival (DFS) in the overall population and in the population with high programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (tumor proportion score [TPS] ≥ 50%). The study met its primary endpoint where improved DFS was observed in the overall population that included lung cancers, whether they were PD-L1–negative (TPS = 0%) or –positive (TPS ≥ 1%) (53.6 months in the pembrolizumab group vs 42.0 months in the placebo group [hazard ratio (HR) 0.76; P = .0014]). Overall survival data are not yet clear. Of note, in the interim analysis presented, the subset of patients with high PD-L1 NSCLC (TPS ≥ 50%) did not show a DFS benefit whereas in other adjuvant and neoadjuvant studies, such as IMpower010 and CheckMate 816, the subset of high PD-L1 patients appeared to derive the most benefit. The results from the high PD-L1 subset and other subsets may change with future updated analyses as more events occur. The major co-primary endpoint was clearly met with the overall population clearly showing a positive DFS benefit. The results of the PEARLS trial adds to the current landscape of systemic treatment of early-stage NSCLC where neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for stage IB (≥ 4 cm) to IIIA resected NSCLC regardless of level of PD-L1 expression, as is adjuvant atezolizumab after consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients that are PD-L1–positive (≥ 1%) on the basis of a DFS benefit observed in this population.1,2 For the future, it is important to see if the DFS benefit observed in these studies translates into a meaningful overall survival benefit.

Plasma cfDNA Levels as a Prognostic Marker in ALK+ NSCLC in the ALEX Trial

The ALEX trial is a pivotal global phase 3 randomized control trial that demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) with the next-generation ALK inhibitor alectinib compared with the first-generation ALK inhibitor crizotinib as first-line treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC (HR 0.43; 95% CI 0.32-0.58; median PFS 34.8 vs 10.9 months crizotinib).3 In a study recently published in Clinical Cancer Research, Dr Dziadziuszko and colleagues retrospectively assessed the prognostic value of baseline cell-free DNA (cfDNA) levels in patients treated in the ALEX trial. Baseline plasma for cfDNA was quantified by the Foundation ACT next-generation sequencing assay. Clinical outcomes were assessed by quantitative cfDNA level stratified by the median value. In both the alectinib and crizotinib treatment arms, patients with cfDNA levels above the median were more likely to experience disease progression (alectinib adjusted HR 2.04; 95% CI 1.07-3.89; P = .03 and crizotinib adjusted HR 1.83; 95% CI 1.11-3.00, P = .016). Though survival data are incomplete, the study also suggested survival probability was lower when baseline cfDNA was above the median in both the alectinib and crizotinib treatment arms. Regardless of cfDNA levels, PFS was improved with alectinib compared with crizotinib. Previous studies have shown the value of cfDNA analysis at the time of progression to guide further treatment and target resistance mechanisms to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), such as G1202R, or bypass tract pathways, such as MET amplification.4,5 Assessment of the EML4-ALK variant type (V1 vs V3) has been shown to associate with certain types of resistance mechanisms (ie, on target ALK mutations, such as G1202R in V3) and clinical activity of specific ALK TKI (V3 > V1 for PFS with lorlatinib).6 This study examining baseline cfDNA levels and clinical outcomes on the ALEX trial shows the potential utility of baseline cfDNA levels as a prognostic factor for ALK TKI.

Lorlatinib in ROS1-Rearranged NSCLC After Progression on Prior ROS1 TKI

ROS1 rearrangements represent about 1.5% of lung adenocarcinoma. In advanced disease, both crizotinib and entrectinib are FDA-approved as agents targeting ROS1 with robust PFS. The third-generation TKI lorlatinib is approved and has substantial activity in ALK-rearranged NSCLC. In a recently published retrospective real-world cohort study by Girard and colleagues (LORLATU), 80 patients with ROS1-rearranged NSCLC were treated with lorlatinib as second-line treatment or beyond and after failure on at least one prior ROS1 TKI. Median PFS was 7.1 months (95% CI 5.0-9.9) and median overall survival was 19.6 months (95% CI 12.3-27.5). The overall response rate was 45% and the disease control rate was 82%. The central nervous system response rate was 72%. There were no new safety signals. This retrospective cohort study demonstrates that lorlatinib is a major targeted therapy treatment option in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC.

Checkmate 816: Neoadjuvant Nivolumab Plus Chemotherapy in Resectable NSCLC

In this open-label, phase 3 trial, 358 patients with stage IB (T ³ 4cm) to IIIA (per AJCC v7) resectable NSCLC were randomized 1:1 to receive nivolumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy or platinum-based chemotherapy alone for three cycles, followed by surgical resection. The primary endpoints were event-free survival (EFS) and pathological complete response (pCR) (0% viable tumor in resected lung and lymph nodes), both evaluated by blinded independent review. The median EFS was significantly increased in the nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm compared to chemotherapy alone: 31.6 months (95% CI 30.2 to not reached) vs 20.8 months (95% CI 14.0 to 26.7) (HR 0.63; 97.38% CI 0.43 to 0.91; P = .005). pCR rate was also increased in the nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm (24.0% vs 2.2%, respectively; odds ratio 13.94; 99% CI 3.49 to 55.75; P < .001). At the first prespecified interim analysis, the hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (99.67% CI 0.30 to 1.07), which currently does not meet the criterion for statistical significance. Of the randomized patients, 83.2% of those in the nivolumab-plus chemotherapy group and 75.4% of those in the chemotherapy-alone group were able to undergo surgery. Grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 33.5% of the patients in the nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy group and in 36.9% of those in the chemotherapy-alone group. In an exploratory analysis, EFS was longer in patients with pCR than patients without a pCR. In a subset analysis, patients with high PD-L1 expression (³50%) stood out in terms of particular benefit (HR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10–0.61). The Checkmate 816 trial is a landmark study. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy represents a new standard of care in the systemic treatment of resectable NSCLC that is at a stage that warrants systemic treatment. It is FDA approved regardless of PD-L1 expression level including PD-L1 negative (0%) patients.2 Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy is also an FDA-approved treatment option for patients that are PD-L1 positive (³1%) based upon the IMpower 010 study.1 It will be important to assess the overall survival benefit as the trial data matures, which seems to be trending in the right direction. Additional neoadjuvant clinical trials with chemoimmunotherapy have completed accrual and some of these trials also continued PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in the adjuvant setting after surgery. An important question for the future is if combination of PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint blockade with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting along with continuation of immunotherapy in the adjuvant setting post-surgery will further improve clinical outcomes.

References

- Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-57. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02098-5 Source

- Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. April 11, 2022. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2202170 Source

- Mok T, Camige DR, Gadgeel SM, et al. Updated overall survival and final progression-free survival data for patients with treatment-naive advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer in the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1056-1064. Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.478 Source

- Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Chiari R, et al. Lorlatinib in advanced ROS1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1691-1701. Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30655-2 Source

- Lawrence MN, Tamen RM, Martinez P, et al. SPACEWALK: A remote participation study of ALK resistance leveraging plasma cell-free DNA genotyping. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;2:100151. Doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100151 Source

- Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Yoda S, et al. Impact of EML4-ALK variant on resistance mechanisms and clinical outcomes in ALK-positive lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1199-1206. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2294 Source

In a European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Plenary session, Dr Paz-Ares and colleagues presented interim analysis of the PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 study of adjuvant pembrolizumab. In this triple-blind phase 3 trial, 1177 patients with stage IB (tumor ≥ 4 cm) to IIIA non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (per American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC], version 7) were randomly assigned to receive pembrolizumab vs placebo. The dual primary endpoints were disease-free survival (DFS) in the overall population and in the population with high programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (tumor proportion score [TPS] ≥ 50%). The study met its primary endpoint where improved DFS was observed in the overall population that included lung cancers, whether they were PD-L1–negative (TPS = 0%) or –positive (TPS ≥ 1%) (53.6 months in the pembrolizumab group vs 42.0 months in the placebo group [hazard ratio (HR) 0.76; P = .0014]). Overall survival data are not yet clear. Of note, in the interim analysis presented, the subset of patients with high PD-L1 NSCLC (TPS ≥ 50%) did not show a DFS benefit whereas in other adjuvant and neoadjuvant studies, such as IMpower010 and CheckMate 816, the subset of high PD-L1 patients appeared to derive the most benefit. The results from the high PD-L1 subset and other subsets may change with future updated analyses as more events occur. The major co-primary endpoint was clearly met with the overall population clearly showing a positive DFS benefit. The results of the PEARLS trial adds to the current landscape of systemic treatment of early-stage NSCLC where neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for stage IB (≥ 4 cm) to IIIA resected NSCLC regardless of level of PD-L1 expression, as is adjuvant atezolizumab after consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients that are PD-L1–positive (≥ 1%) on the basis of a DFS benefit observed in this population.1,2 For the future, it is important to see if the DFS benefit observed in these studies translates into a meaningful overall survival benefit.

Plasma cfDNA Levels as a Prognostic Marker in ALK+ NSCLC in the ALEX Trial

The ALEX trial is a pivotal global phase 3 randomized control trial that demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) with the next-generation ALK inhibitor alectinib compared with the first-generation ALK inhibitor crizotinib as first-line treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC (HR 0.43; 95% CI 0.32-0.58; median PFS 34.8 vs 10.9 months crizotinib).3 In a study recently published in Clinical Cancer Research, Dr Dziadziuszko and colleagues retrospectively assessed the prognostic value of baseline cell-free DNA (cfDNA) levels in patients treated in the ALEX trial. Baseline plasma for cfDNA was quantified by the Foundation ACT next-generation sequencing assay. Clinical outcomes were assessed by quantitative cfDNA level stratified by the median value. In both the alectinib and crizotinib treatment arms, patients with cfDNA levels above the median were more likely to experience disease progression (alectinib adjusted HR 2.04; 95% CI 1.07-3.89; P = .03 and crizotinib adjusted HR 1.83; 95% CI 1.11-3.00, P = .016). Though survival data are incomplete, the study also suggested survival probability was lower when baseline cfDNA was above the median in both the alectinib and crizotinib treatment arms. Regardless of cfDNA levels, PFS was improved with alectinib compared with crizotinib. Previous studies have shown the value of cfDNA analysis at the time of progression to guide further treatment and target resistance mechanisms to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), such as G1202R, or bypass tract pathways, such as MET amplification.4,5 Assessment of the EML4-ALK variant type (V1 vs V3) has been shown to associate with certain types of resistance mechanisms (ie, on target ALK mutations, such as G1202R in V3) and clinical activity of specific ALK TKI (V3 > V1 for PFS with lorlatinib).6 This study examining baseline cfDNA levels and clinical outcomes on the ALEX trial shows the potential utility of baseline cfDNA levels as a prognostic factor for ALK TKI.

Lorlatinib in ROS1-Rearranged NSCLC After Progression on Prior ROS1 TKI

ROS1 rearrangements represent about 1.5% of lung adenocarcinoma. In advanced disease, both crizotinib and entrectinib are FDA-approved as agents targeting ROS1 with robust PFS. The third-generation TKI lorlatinib is approved and has substantial activity in ALK-rearranged NSCLC. In a recently published retrospective real-world cohort study by Girard and colleagues (LORLATU), 80 patients with ROS1-rearranged NSCLC were treated with lorlatinib as second-line treatment or beyond and after failure on at least one prior ROS1 TKI. Median PFS was 7.1 months (95% CI 5.0-9.9) and median overall survival was 19.6 months (95% CI 12.3-27.5). The overall response rate was 45% and the disease control rate was 82%. The central nervous system response rate was 72%. There were no new safety signals. This retrospective cohort study demonstrates that lorlatinib is a major targeted therapy treatment option in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC.

Checkmate 816: Neoadjuvant Nivolumab Plus Chemotherapy in Resectable NSCLC

In this open-label, phase 3 trial, 358 patients with stage IB (T ³ 4cm) to IIIA (per AJCC v7) resectable NSCLC were randomized 1:1 to receive nivolumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy or platinum-based chemotherapy alone for three cycles, followed by surgical resection. The primary endpoints were event-free survival (EFS) and pathological complete response (pCR) (0% viable tumor in resected lung and lymph nodes), both evaluated by blinded independent review. The median EFS was significantly increased in the nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm compared to chemotherapy alone: 31.6 months (95% CI 30.2 to not reached) vs 20.8 months (95% CI 14.0 to 26.7) (HR 0.63; 97.38% CI 0.43 to 0.91; P = .005). pCR rate was also increased in the nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm (24.0% vs 2.2%, respectively; odds ratio 13.94; 99% CI 3.49 to 55.75; P < .001). At the first prespecified interim analysis, the hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (99.67% CI 0.30 to 1.07), which currently does not meet the criterion for statistical significance. Of the randomized patients, 83.2% of those in the nivolumab-plus chemotherapy group and 75.4% of those in the chemotherapy-alone group were able to undergo surgery. Grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 33.5% of the patients in the nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy group and in 36.9% of those in the chemotherapy-alone group. In an exploratory analysis, EFS was longer in patients with pCR than patients without a pCR. In a subset analysis, patients with high PD-L1 expression (³50%) stood out in terms of particular benefit (HR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10–0.61). The Checkmate 816 trial is a landmark study. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy represents a new standard of care in the systemic treatment of resectable NSCLC that is at a stage that warrants systemic treatment. It is FDA approved regardless of PD-L1 expression level including PD-L1 negative (0%) patients.2 Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy is also an FDA-approved treatment option for patients that are PD-L1 positive (³1%) based upon the IMpower 010 study.1 It will be important to assess the overall survival benefit as the trial data matures, which seems to be trending in the right direction. Additional neoadjuvant clinical trials with chemoimmunotherapy have completed accrual and some of these trials also continued PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in the adjuvant setting after surgery. An important question for the future is if combination of PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint blockade with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting along with continuation of immunotherapy in the adjuvant setting post-surgery will further improve clinical outcomes.

References

- Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-57. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02098-5 Source

- Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. April 11, 2022. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2202170 Source

- Mok T, Camige DR, Gadgeel SM, et al. Updated overall survival and final progression-free survival data for patients with treatment-naive advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer in the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1056-1064. Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.478 Source

- Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Chiari R, et al. Lorlatinib in advanced ROS1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1691-1701. Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30655-2 Source

- Lawrence MN, Tamen RM, Martinez P, et al. SPACEWALK: A remote participation study of ALK resistance leveraging plasma cell-free DNA genotyping. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;2:100151. Doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100151 Source

- Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Yoda S, et al. Impact of EML4-ALK variant on resistance mechanisms and clinical outcomes in ALK-positive lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1199-1206. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2294 Source

Fifth COVID shot recommended for patients with cancer

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has recommended a fifth COVID-19 mRNA shot for people who are immunocompromised, including many with cancer or a history of cancer.

A fifth shot of an mRNA vaccine represents a second booster, the group explained, because the primary mRNA immunization series for immunocompromised individuals involves three doses of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine.

The update, issued today, comes from the NCCN’s Advisory Committee on COVID-19 Vaccination and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, which released its first vaccine guidelines for patients with cancer in January 2021. The NCCN has issued numerous updates since then as information about the virus and vaccines has evolved.

“We know a lot more about COVID-19 and the vaccines now, and we can use that knowledge to minimize the confusion and enhance the protection we can offer to our immunocompromised patients,” said advisory committee co-leader Lindsey Baden, MD, an infectious diseases specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

The latest iteration of the NCCN’s COVID guidelines includes an update for patients who initially received Johnson & Johnson’s single-shot vaccine, including a recommendation that patients receive an mRNA vaccine for both the first and second booster.

The group also updated dosing recommendations for pre-exposure prevention with tixagevimab plus cilgavimab (Evusheld, AstraZeneca), suggesting 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody instead of 150 mg, based on in vitro activity against Omicron variants.

The group noted that the Moderna and Pfizer shots can be used interchangeably for boosters.

“The NCCN Committee considers both homologous and heterologous boosters to be appropriate options,” the experts wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has recommended a fifth COVID-19 mRNA shot for people who are immunocompromised, including many with cancer or a history of cancer.

A fifth shot of an mRNA vaccine represents a second booster, the group explained, because the primary mRNA immunization series for immunocompromised individuals involves three doses of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine.

The update, issued today, comes from the NCCN’s Advisory Committee on COVID-19 Vaccination and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, which released its first vaccine guidelines for patients with cancer in January 2021. The NCCN has issued numerous updates since then as information about the virus and vaccines has evolved.

“We know a lot more about COVID-19 and the vaccines now, and we can use that knowledge to minimize the confusion and enhance the protection we can offer to our immunocompromised patients,” said advisory committee co-leader Lindsey Baden, MD, an infectious diseases specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

The latest iteration of the NCCN’s COVID guidelines includes an update for patients who initially received Johnson & Johnson’s single-shot vaccine, including a recommendation that patients receive an mRNA vaccine for both the first and second booster.

The group also updated dosing recommendations for pre-exposure prevention with tixagevimab plus cilgavimab (Evusheld, AstraZeneca), suggesting 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody instead of 150 mg, based on in vitro activity against Omicron variants.

The group noted that the Moderna and Pfizer shots can be used interchangeably for boosters.

“The NCCN Committee considers both homologous and heterologous boosters to be appropriate options,” the experts wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has recommended a fifth COVID-19 mRNA shot for people who are immunocompromised, including many with cancer or a history of cancer.

A fifth shot of an mRNA vaccine represents a second booster, the group explained, because the primary mRNA immunization series for immunocompromised individuals involves three doses of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine.

The update, issued today, comes from the NCCN’s Advisory Committee on COVID-19 Vaccination and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, which released its first vaccine guidelines for patients with cancer in January 2021. The NCCN has issued numerous updates since then as information about the virus and vaccines has evolved.

“We know a lot more about COVID-19 and the vaccines now, and we can use that knowledge to minimize the confusion and enhance the protection we can offer to our immunocompromised patients,” said advisory committee co-leader Lindsey Baden, MD, an infectious diseases specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

The latest iteration of the NCCN’s COVID guidelines includes an update for patients who initially received Johnson & Johnson’s single-shot vaccine, including a recommendation that patients receive an mRNA vaccine for both the first and second booster.

The group also updated dosing recommendations for pre-exposure prevention with tixagevimab plus cilgavimab (Evusheld, AstraZeneca), suggesting 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody instead of 150 mg, based on in vitro activity against Omicron variants.

The group noted that the Moderna and Pfizer shots can be used interchangeably for boosters.

“The NCCN Committee considers both homologous and heterologous boosters to be appropriate options,” the experts wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

EU approves new blood and lung cancer drugs

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) issued a positive opinion for the two products at its April meeting.

New drug for certain lung cancer patients

Capmatinib is a selective, reversible inhibitor of MET tyrosine kinase and is indicated for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC harboring alterations leading to mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor gene exon 14 (METex14) skipping. Patients must have already been treated with immunotherapy and/or platinum-based chemotherapy.

The product is approved in the United States, and the Food and Drug Administration noted that it is the first approved treatment for NSCLC with MET exon 14-skipping mutations.

The FDA granted the drug an accelerated approval based on overall response rate and response duration in the GEOMETRY mono-1 trial, which included a cohort of previously treated and treatment-naive patients. The overall response rate was 68% in the treatment-naive patients and 41% in the previously treated patients. The median duration of response was 12.6 months and 9.7 months.

The most common side effects were peripheral edema, nausea, fatigue, vomiting, dyspnea, and decreased appetite.

Conditional approval for lymphoma

Mosunetuzumab is an investigational bispecific antibody targeting CD20 and CD3, and redirects T cells to engage and eliminate malignant B cells.

The CHMP recommended a conditional approval for this drug for use as monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

Mosunetuzumab was reviewed under EMA’s accelerated access program, which usually takes 150 evaluation days as opposed to 210, and it was designated as an orphan medicine during its development.

The EMA stated that the benefits of this product are the high proportion of patients with a complete response and the durability of the treatment response.

As previously reported by this news organization, results from a phase 2 expansion study showed that when used as monotherapy, it induced high response rates and long-duration responses in patients with heavily pretreated, relapsed, or refractory follicular lymphoma.

At a median follow-up of 18.3 months, 54 of 90 patients (60%) had a complete response, and 18 (20%) had a partial response after treatment with mosunetuzumab.

The most common reported side effects were cytokine release syndrome, neutropenia, pyrexia (fever), hypophosphatemia, and headache.

Mosunetuzumab is awaiting FDA approval in the United States.

A conditional marketing authorization from CHMP is granted to products that meet an unmet medical need, and when the benefit to public health of immediate availability outweighs the risk inherent in the fact that additional data are still required. The marketing authorization holder is expected to provide comprehensive clinical data at a later stage.

Detailed recommendations for the use of both products will be described in the summary of product characteristics (SmPC), which will be published in the European public assessment report (EPAR) and made available in all official European Union languages after the marketing authorization has been granted by the European Commission.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) issued a positive opinion for the two products at its April meeting.

New drug for certain lung cancer patients

Capmatinib is a selective, reversible inhibitor of MET tyrosine kinase and is indicated for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC harboring alterations leading to mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor gene exon 14 (METex14) skipping. Patients must have already been treated with immunotherapy and/or platinum-based chemotherapy.

The product is approved in the United States, and the Food and Drug Administration noted that it is the first approved treatment for NSCLC with MET exon 14-skipping mutations.

The FDA granted the drug an accelerated approval based on overall response rate and response duration in the GEOMETRY mono-1 trial, which included a cohort of previously treated and treatment-naive patients. The overall response rate was 68% in the treatment-naive patients and 41% in the previously treated patients. The median duration of response was 12.6 months and 9.7 months.

The most common side effects were peripheral edema, nausea, fatigue, vomiting, dyspnea, and decreased appetite.

Conditional approval for lymphoma

Mosunetuzumab is an investigational bispecific antibody targeting CD20 and CD3, and redirects T cells to engage and eliminate malignant B cells.

The CHMP recommended a conditional approval for this drug for use as monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

Mosunetuzumab was reviewed under EMA’s accelerated access program, which usually takes 150 evaluation days as opposed to 210, and it was designated as an orphan medicine during its development.

The EMA stated that the benefits of this product are the high proportion of patients with a complete response and the durability of the treatment response.

As previously reported by this news organization, results from a phase 2 expansion study showed that when used as monotherapy, it induced high response rates and long-duration responses in patients with heavily pretreated, relapsed, or refractory follicular lymphoma.

At a median follow-up of 18.3 months, 54 of 90 patients (60%) had a complete response, and 18 (20%) had a partial response after treatment with mosunetuzumab.

The most common reported side effects were cytokine release syndrome, neutropenia, pyrexia (fever), hypophosphatemia, and headache.

Mosunetuzumab is awaiting FDA approval in the United States.

A conditional marketing authorization from CHMP is granted to products that meet an unmet medical need, and when the benefit to public health of immediate availability outweighs the risk inherent in the fact that additional data are still required. The marketing authorization holder is expected to provide comprehensive clinical data at a later stage.

Detailed recommendations for the use of both products will be described in the summary of product characteristics (SmPC), which will be published in the European public assessment report (EPAR) and made available in all official European Union languages after the marketing authorization has been granted by the European Commission.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) issued a positive opinion for the two products at its April meeting.

New drug for certain lung cancer patients

Capmatinib is a selective, reversible inhibitor of MET tyrosine kinase and is indicated for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC harboring alterations leading to mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor gene exon 14 (METex14) skipping. Patients must have already been treated with immunotherapy and/or platinum-based chemotherapy.

The product is approved in the United States, and the Food and Drug Administration noted that it is the first approved treatment for NSCLC with MET exon 14-skipping mutations.

The FDA granted the drug an accelerated approval based on overall response rate and response duration in the GEOMETRY mono-1 trial, which included a cohort of previously treated and treatment-naive patients. The overall response rate was 68% in the treatment-naive patients and 41% in the previously treated patients. The median duration of response was 12.6 months and 9.7 months.