User login

For MD-IQ use only

Junior faculty guide to preparing a research grant

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“You have a pending query”

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

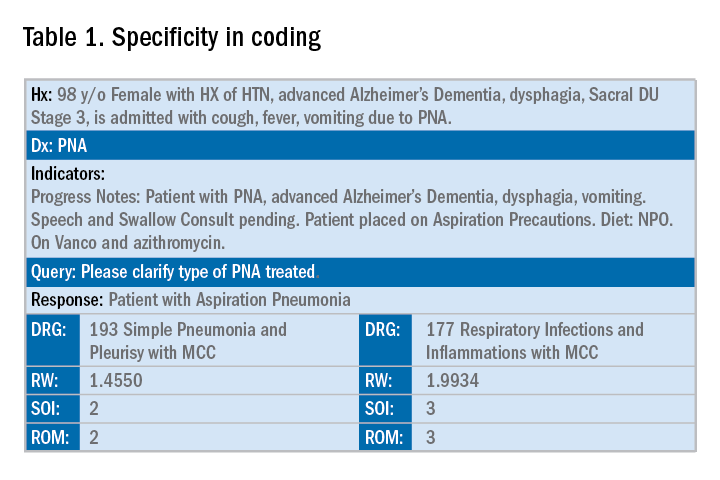

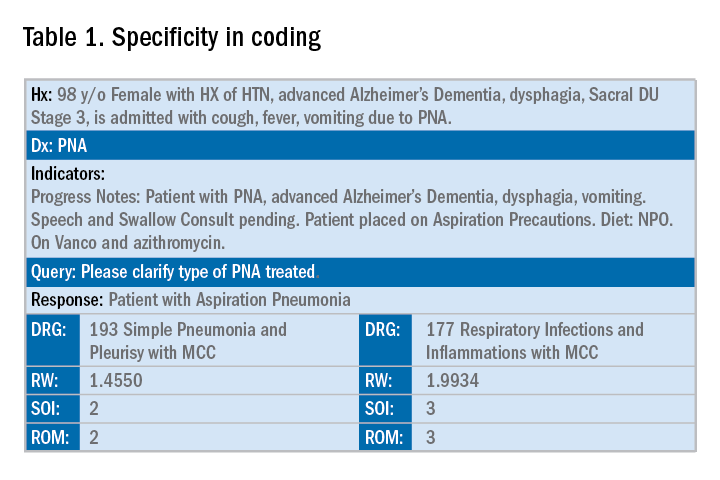

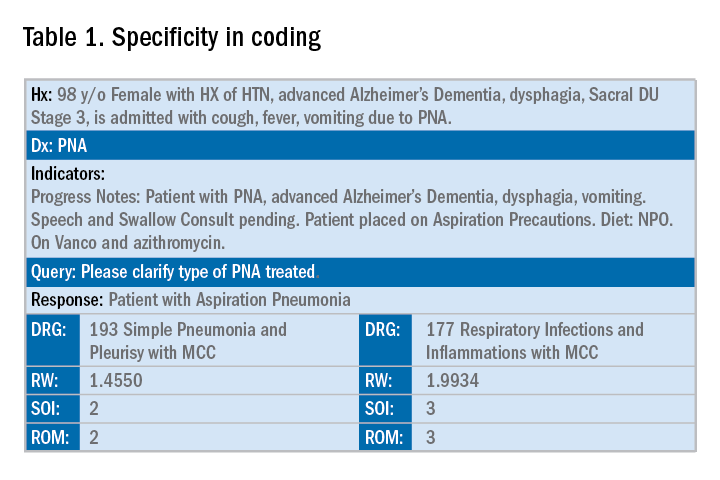

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

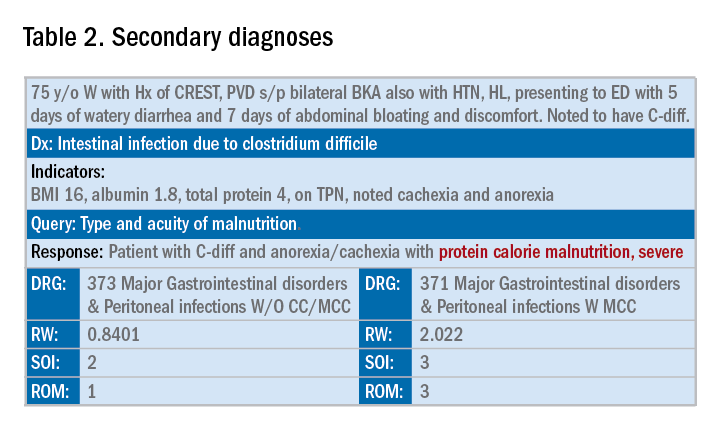

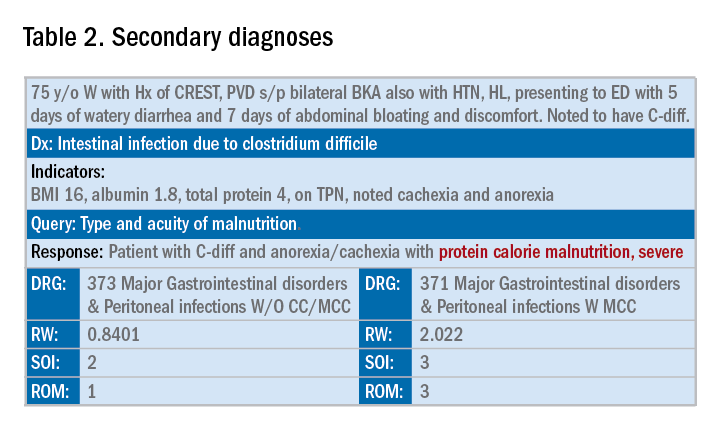

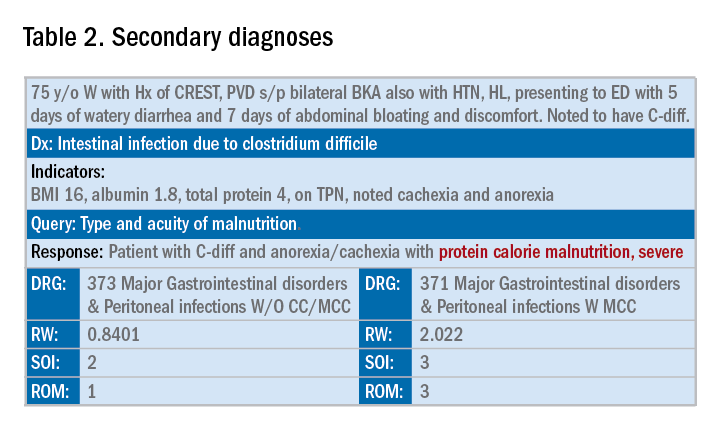

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

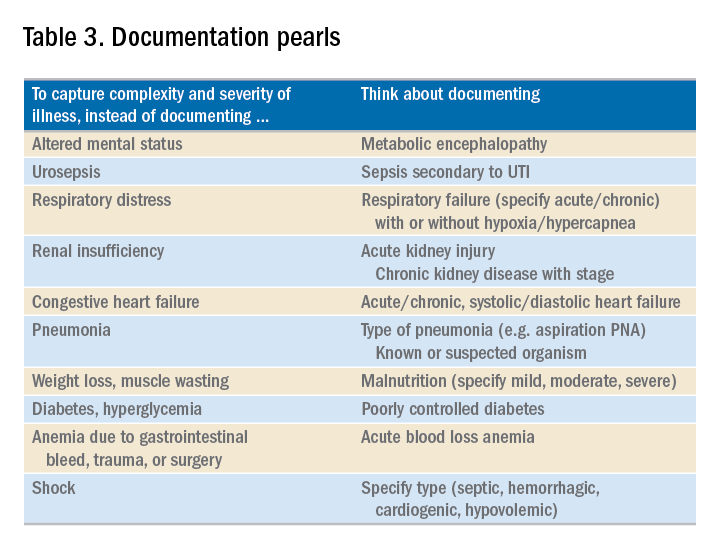

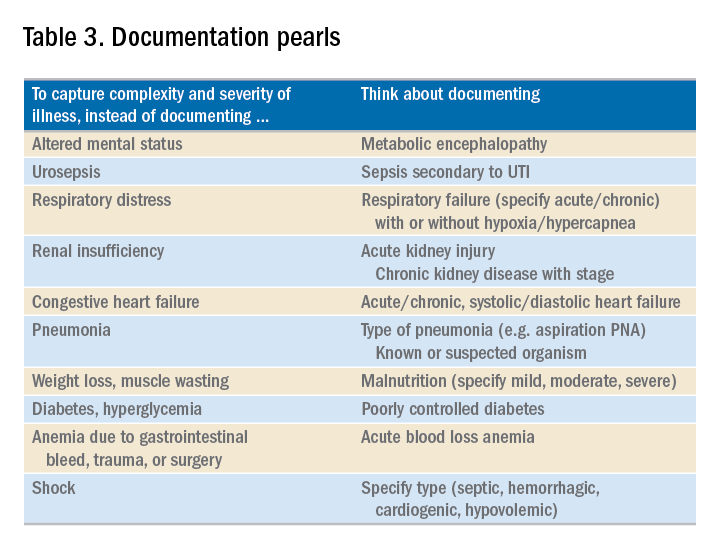

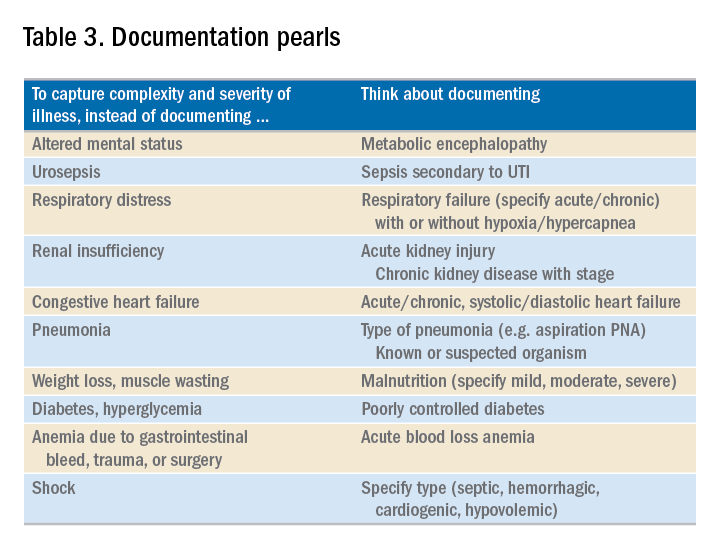

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Genes more important than food in hyperuricemia

Also today, time reveals a benefit of CABG over PCI for left main artery disease, lower-limb atherosclerosis predicts long-term mortality in patients with PAD, and TV ads could be required to display drug prices.

Subscribe here:

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, time reveals a benefit of CABG over PCI for left main artery disease, lower-limb atherosclerosis predicts long-term mortality in patients with PAD, and TV ads could be required to display drug prices.

Subscribe here:

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, time reveals a benefit of CABG over PCI for left main artery disease, lower-limb atherosclerosis predicts long-term mortality in patients with PAD, and TV ads could be required to display drug prices.

Subscribe here:

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Carl C. Bell: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder Part II

Glycemic effects of lorcaserin

Also today, increased risk for suicide among adults who harm themselves, banning corporal punishment may reduce violence in youth, and a formula that scores the quality of a diet is validated.

Also today, increased risk for suicide among adults who harm themselves, banning corporal punishment may reduce violence in youth, and a formula that scores the quality of a diet is validated.

Also today, increased risk for suicide among adults who harm themselves, banning corporal punishment may reduce violence in youth, and a formula that scores the quality of a diet is validated.

Fat attenuation index boosts coronary CT prognostication

MUNICH – The perivascular fat attenuation index, a new measure of coronary plaque inflammation using data collected by a conventional coronary CT scan, identified an elevated risk for future cardiovascular death that was independent of standard risk factors in both derivation and validation studies with prospective data from more than 3,900 patients.

Patients with a high fat attenuation index (FAI) in the perivascular fat surrounding their right coronary artery had a five- to ninefold higher risk of cardiac mortality during 4-6 years of follow-up than did those with lower scores, after adjustment for conventional risk factors and standard findings from the coronary CT, Charalambos Antoniades, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The FAI is a “powerful, novel technology for cardiovascular disease risk stratification. It has striking prognostic value for cardiac death and nonfatal MI over and above other risk scores and state-of-the-art interpretation of coronary CT angiography,” said Dr. Antoniades, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford (England). He also highlighted that the data he reported suggested a protective effect in patients with a high FAI who received treatment with aspirin or a statin, and he suggested that FAI might be a way to better target an anti-inflammatory agent such as canakinumab (Ilaris), which showed cardiovascular protective effects in the CANTOS trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31).

Another key feature of the FAI analysis is that it uses data collected by “any standard” coronary CT angiogram, Dr. Antoniades said. He is a founder of, shareholder in, and chief scientific officer of Caristo Diagnostics, the company developing the software that uses coronary CT data to calculate the FAI.

Dr. Antoniades and his associates derived the FAI using data collected from 1,872 patients who underwent planned coronary CT angiography at a clinic in Erlangen, Germany, during 2005-2009. The researchers correlated FAI scores with cardiovascular disease outcomes during a median follow-up of 72 months. They then validated the FAI using data collected from 2,040 patients who underwent a planned coronary CT exam at the Cleveland Clinic during 2008-2016 and then had a median follow-up of 54 months. The researchers called this overall post-hoc analysis of prospectively collected CT and outcomes data the Cardiovascular Risk Prediction using Computed Tomography (CRISP-CT) study.

Using the derivation data, FAI measurements taken from fat around the proximal right coronary artery that met or exceeded the specified cutoff value of –70.1 Hounsfield units were tied to a 9.04-fold greater rate of cardiac death during follow-up, compared with patients with a lower FAI, and after adjustment for several demographic, clinical, and CT-angiography variables. When the researchers ran this analysis using data from the validation patients and the same cutoff value they found that an elevated FAI linked with a 5.6-fold higher rate of cardiac death. Concurrently with Dr. Antoniades’ talk the results appeared in an online article that was later published (Lancet. 2018 Sep 15;392[10151]:929-39).

Calculating a patient’s FAI offers the prospect for “better use of CT information,” Dr. Antoniades said during the discussion of his report. After a coronary CT scan and conventional data processing, about half the patients have no finding that warrants intervention, but about 10% of these patients actually have an inflamed coronary plaque that is at high risk for rupture that could trigger a cardiac event. The FAI provides a way to use coronary CT angiography to identify these at-risk patients, he explained.

MUNICH – The perivascular fat attenuation index, a new measure of coronary plaque inflammation using data collected by a conventional coronary CT scan, identified an elevated risk for future cardiovascular death that was independent of standard risk factors in both derivation and validation studies with prospective data from more than 3,900 patients.

Patients with a high fat attenuation index (FAI) in the perivascular fat surrounding their right coronary artery had a five- to ninefold higher risk of cardiac mortality during 4-6 years of follow-up than did those with lower scores, after adjustment for conventional risk factors and standard findings from the coronary CT, Charalambos Antoniades, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The FAI is a “powerful, novel technology for cardiovascular disease risk stratification. It has striking prognostic value for cardiac death and nonfatal MI over and above other risk scores and state-of-the-art interpretation of coronary CT angiography,” said Dr. Antoniades, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford (England). He also highlighted that the data he reported suggested a protective effect in patients with a high FAI who received treatment with aspirin or a statin, and he suggested that FAI might be a way to better target an anti-inflammatory agent such as canakinumab (Ilaris), which showed cardiovascular protective effects in the CANTOS trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31).

Another key feature of the FAI analysis is that it uses data collected by “any standard” coronary CT angiogram, Dr. Antoniades said. He is a founder of, shareholder in, and chief scientific officer of Caristo Diagnostics, the company developing the software that uses coronary CT data to calculate the FAI.

Dr. Antoniades and his associates derived the FAI using data collected from 1,872 patients who underwent planned coronary CT angiography at a clinic in Erlangen, Germany, during 2005-2009. The researchers correlated FAI scores with cardiovascular disease outcomes during a median follow-up of 72 months. They then validated the FAI using data collected from 2,040 patients who underwent a planned coronary CT exam at the Cleveland Clinic during 2008-2016 and then had a median follow-up of 54 months. The researchers called this overall post-hoc analysis of prospectively collected CT and outcomes data the Cardiovascular Risk Prediction using Computed Tomography (CRISP-CT) study.

Using the derivation data, FAI measurements taken from fat around the proximal right coronary artery that met or exceeded the specified cutoff value of –70.1 Hounsfield units were tied to a 9.04-fold greater rate of cardiac death during follow-up, compared with patients with a lower FAI, and after adjustment for several demographic, clinical, and CT-angiography variables. When the researchers ran this analysis using data from the validation patients and the same cutoff value they found that an elevated FAI linked with a 5.6-fold higher rate of cardiac death. Concurrently with Dr. Antoniades’ talk the results appeared in an online article that was later published (Lancet. 2018 Sep 15;392[10151]:929-39).

Calculating a patient’s FAI offers the prospect for “better use of CT information,” Dr. Antoniades said during the discussion of his report. After a coronary CT scan and conventional data processing, about half the patients have no finding that warrants intervention, but about 10% of these patients actually have an inflamed coronary plaque that is at high risk for rupture that could trigger a cardiac event. The FAI provides a way to use coronary CT angiography to identify these at-risk patients, he explained.

MUNICH – The perivascular fat attenuation index, a new measure of coronary plaque inflammation using data collected by a conventional coronary CT scan, identified an elevated risk for future cardiovascular death that was independent of standard risk factors in both derivation and validation studies with prospective data from more than 3,900 patients.

Patients with a high fat attenuation index (FAI) in the perivascular fat surrounding their right coronary artery had a five- to ninefold higher risk of cardiac mortality during 4-6 years of follow-up than did those with lower scores, after adjustment for conventional risk factors and standard findings from the coronary CT, Charalambos Antoniades, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The FAI is a “powerful, novel technology for cardiovascular disease risk stratification. It has striking prognostic value for cardiac death and nonfatal MI over and above other risk scores and state-of-the-art interpretation of coronary CT angiography,” said Dr. Antoniades, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford (England). He also highlighted that the data he reported suggested a protective effect in patients with a high FAI who received treatment with aspirin or a statin, and he suggested that FAI might be a way to better target an anti-inflammatory agent such as canakinumab (Ilaris), which showed cardiovascular protective effects in the CANTOS trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31).

Another key feature of the FAI analysis is that it uses data collected by “any standard” coronary CT angiogram, Dr. Antoniades said. He is a founder of, shareholder in, and chief scientific officer of Caristo Diagnostics, the company developing the software that uses coronary CT data to calculate the FAI.

Dr. Antoniades and his associates derived the FAI using data collected from 1,872 patients who underwent planned coronary CT angiography at a clinic in Erlangen, Germany, during 2005-2009. The researchers correlated FAI scores with cardiovascular disease outcomes during a median follow-up of 72 months. They then validated the FAI using data collected from 2,040 patients who underwent a planned coronary CT exam at the Cleveland Clinic during 2008-2016 and then had a median follow-up of 54 months. The researchers called this overall post-hoc analysis of prospectively collected CT and outcomes data the Cardiovascular Risk Prediction using Computed Tomography (CRISP-CT) study.

Using the derivation data, FAI measurements taken from fat around the proximal right coronary artery that met or exceeded the specified cutoff value of –70.1 Hounsfield units were tied to a 9.04-fold greater rate of cardiac death during follow-up, compared with patients with a lower FAI, and after adjustment for several demographic, clinical, and CT-angiography variables. When the researchers ran this analysis using data from the validation patients and the same cutoff value they found that an elevated FAI linked with a 5.6-fold higher rate of cardiac death. Concurrently with Dr. Antoniades’ talk the results appeared in an online article that was later published (Lancet. 2018 Sep 15;392[10151]:929-39).

Calculating a patient’s FAI offers the prospect for “better use of CT information,” Dr. Antoniades said during the discussion of his report. After a coronary CT scan and conventional data processing, about half the patients have no finding that warrants intervention, but about 10% of these patients actually have an inflamed coronary plaque that is at high risk for rupture that could trigger a cardiac event. The FAI provides a way to use coronary CT angiography to identify these at-risk patients, he explained.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with a fat attenuation index at or above the selected cutoff had a five- to ninefold increased rate of cardiac death.

Study details: The CRISP-CT study, which ran a post-hoc analysis of CT angiography data from 3,912 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Antoniades is a founder of, shareholder in, and chief scientific officer of Caristo Diagnostics, the company developing fat attenuation index software.

A change in ‘incident to’ billing

Also today, stepping down to oral ciprofloxacin looks safe in gram-negative bloodstream infections, a nasal cannula device may be an option for severe COPD, and brexanolone injection quickly improves postpartum depression.

Also today, stepping down to oral ciprofloxacin looks safe in gram-negative bloodstream infections, a nasal cannula device may be an option for severe COPD, and brexanolone injection quickly improves postpartum depression.

Also today, stepping down to oral ciprofloxacin looks safe in gram-negative bloodstream infections, a nasal cannula device may be an option for severe COPD, and brexanolone injection quickly improves postpartum depression.

Benzodiazepines double risk of suicide among COPD patients

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are taking benzodiazepines have more than double the risk of suicide compared with patients who are not on those medications. Also today, the feds say that the ACA’s silver plan premiums will drop in 2019, bias in the clinical setting can impact patient care, and managing asthma in children mean that pets do not always have to go.

The Postcall Podcast is available here: https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are taking benzodiazepines have more than double the risk of suicide compared with patients who are not on those medications. Also today, the feds say that the ACA’s silver plan premiums will drop in 2019, bias in the clinical setting can impact patient care, and managing asthma in children mean that pets do not always have to go.

The Postcall Podcast is available here: https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are taking benzodiazepines have more than double the risk of suicide compared with patients who are not on those medications. Also today, the feds say that the ACA’s silver plan premiums will drop in 2019, bias in the clinical setting can impact patient care, and managing asthma in children mean that pets do not always have to go.

The Postcall Podcast is available here: https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts

Introducing the Postcall Podcast

At MDedge, we know that medicine can be a bit of an awakening at every step of your career. So, we launched the Postcall Podcast as a way to share your stories: what you love about medicine and what you love outside of your career. This podcast is meant to be a place for you to find your truth.

In the first episode, Nick Andrews welcomes the Editor-In-Chief of MDedge Psychiatry and the host of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

At MDedge, we know that medicine can be a bit of an awakening at every step of your career. So, we launched the Postcall Podcast as a way to share your stories: what you love about medicine and what you love outside of your career. This podcast is meant to be a place for you to find your truth.

In the first episode, Nick Andrews welcomes the Editor-In-Chief of MDedge Psychiatry and the host of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

At MDedge, we know that medicine can be a bit of an awakening at every step of your career. So, we launched the Postcall Podcast as a way to share your stories: what you love about medicine and what you love outside of your career. This podcast is meant to be a place for you to find your truth.

In the first episode, Nick Andrews welcomes the Editor-In-Chief of MDedge Psychiatry and the host of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

DOACs cut mortality

Results from the GARFIELD-AF study show that patients who are newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct action anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked previously seen in randomized trials. Also today, the obesity paradox extends to PE patients, adjuvant flu vaccine reduces hospitalization in the oldest patients, and Tdap vaccination early in the third trimester of pregnancy raises antibodies in newborns.

Check out the MDedge Postcall podcast here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Results from the GARFIELD-AF study show that patients who are newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct action anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked previously seen in randomized trials. Also today, the obesity paradox extends to PE patients, adjuvant flu vaccine reduces hospitalization in the oldest patients, and Tdap vaccination early in the third trimester of pregnancy raises antibodies in newborns.

Check out the MDedge Postcall podcast here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Results from the GARFIELD-AF study show that patients who are newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct action anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked previously seen in randomized trials. Also today, the obesity paradox extends to PE patients, adjuvant flu vaccine reduces hospitalization in the oldest patients, and Tdap vaccination early in the third trimester of pregnancy raises antibodies in newborns.

Check out the MDedge Postcall podcast here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts