User login

Chronic kidney disease tied to worse LAAO outcomes

The presence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is associated with worse in-hospital and short-term outcomes after left atrial appendage (LAA) closure, a nationwide study shows.

Patients with ESRD were particularly vulnerable, having about 6.5-fold higher odds of in-hospital mortality than those without CKD and about 11.5-fold higher odds than those with CKD, even after adjustment for potential confounders.

Patients with CKD had higher rates of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) and more short-term readmissions for bleeding, Keerat Rai Ahuja, MD, Reading Hospital-Tower Health, West Reading, Pennsylvania, and colleagues reported August 16 in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

CKD and ESRD are known to be associated with an increased risk for stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), yet data are limited on the safety and efficacy of LAA closure for stroke prevention in AFib patients with CKD or ESRD, they note.

“It’s important to know about CKD and understand that there may be an association with worse levels of CKD and worse outcomes, but the data that strikes me is really that for end-stage renal disease,” Matthew Sherwood, MD, MHS, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

He noted that data have not been published for patients with CKD and ESRD enrolled in the pivotal PROTECT-AF and PREVAIL trials of Boston Scientific’s Watchman device or from large clinical registries such as EWOLUTION and the company’s continued access protocol registries.

Further, it’s not well understood what the best strategy is to prevent stroke in AFib patients with ESRD and whether they benefit from anticoagulation with warfarin or any of the newer agents. “Thus, it’s hard to then say: ‘Well they have worse outcomes with Watchman,’ which is true as shown in this study, but they may not have any other options based upon the lack of data for oral anticoagulants in end-stage kidney disease patients,” said Dr. Sherwood, from the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Virginia.

The lack of clarity is concerning, given rising atrial fibrillation cases and the prevalence of abnormal renal function in everyday practice. In the present study – involving 21,274 patients undergoing LAA closure between 2016 and 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database – 18.6% of patients had CKD stages I to V and 2.7% had ESRD based on ICD-10 codes.

In-hospital mortality was increased only in patients with ESRD. In all, 3.3% of patients with ESRD and 0.4% of those with no CKD died in hospital (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 6.48), as did 0.5% of patients with CKD (aOR, 11.43; both P <.001).

“These patients represent a sicker population at baseline and have an inherent greater risk for mortality in cardiac interventions, as noted in other studies of structural heart interventions,” Dr. Ahuja and colleagues write.

Patients with CKD had a higher risk for in-hospital stroke or TIA than patients with no CKD (1.8% vs. 1.3%; aOR, 1.35; P = .038) and this risk continued up to 90 days after discharge (1.7% vs. 1.0%; aOR, 1.67; P = .007).

The in-hospital stroke rate was numerically higher in patients with ESRD compared with no CKD (aOR, 1.18; P = .62).

The authors point out that previous LAA closure and CKD studies have reported no differences in in-hospital or subsequent stroke/TIA rates in patients with and without CKD. Possible explanations are that patients with CKD in the present study had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores than those without CKD (4.18 vs. 3.62) and, second, patients with CKD and AFib are known to have higher risk for thromboembolic events than those with AFib without CKD.

CKD patients were also more likely than those without CKD to experience in-hospital acute kidney injury or hemodialysis (aOR, 5.02; P <.001).

CKD has been shown to be independently associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) after LAA closure. AKI may have long-term thromboembolic consequences, the authors suggest, with one study reporting higher stroke risk at midterm follow-up in patients with AKI.

“As with other cardiac interventions in patients with CKD, efforts should be made to optimize preoperative renal function, minimize contrast volume, and avoid abrupt hemodynamic changes such as hypotension during the procedure to prevent AKI,” Dr. Ahuja and colleagues write.

Patients with CKD and ESRD had longer index length of stay than those without CKD but had similar rates of other in-hospital complications, such as systemic embolization, bleeding/transfusion, vascular complications, and pericardial tamponade requiring intervention.

Among the short-term outcomes, 30- and 90-day all-cause readmissions were increased in patients with CKD and ESRD compared with those without CKD, and 30-day bleeding readmissions were increased within the CKD cohort.

“With Watchman and left atrial appendage closure, what we see is that they have higher rates of readmission and other problems,” Dr. Sherwood said. “I think we understand that that’s probably related not to the procedure itself, not because the Watchman doesn’t work for end-stage kidney disease, but because the patients themselves are likely higher risk.”

Commonly used risk scores for atrial fibrillation, however, don’t take into account advanced kidney disease, he added.

Besides the inherent limitations of observational studies, Dr. Sherwood and the authors point to the lack of laboratory variables and procedural variables in the database, the fact that CKD was defined using ICD-10 codes, that outcomes were not clinically adjudicated, that unmeasured confounders likely still exist, and that long-term follow-up is lacking.

Dr. Sherwood, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study, said that the release of outcomes data from CKD and ESRD patients in the major clinical trials would be helpful going forward, as would possible involvement with the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes organization.

“One of the main points of this study is that we just need a lot more research diving into this patient population,” he said.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sherwood reports honoraria from Janssen and Medtronic. Editorial coauthor Sean Pokorney reports research grant support from Gilead, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and the Food and Drug Administration; and advisory board, consulting, and honoraria supports from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Philips, and Zoll.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The presence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is associated with worse in-hospital and short-term outcomes after left atrial appendage (LAA) closure, a nationwide study shows.

Patients with ESRD were particularly vulnerable, having about 6.5-fold higher odds of in-hospital mortality than those without CKD and about 11.5-fold higher odds than those with CKD, even after adjustment for potential confounders.

Patients with CKD had higher rates of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) and more short-term readmissions for bleeding, Keerat Rai Ahuja, MD, Reading Hospital-Tower Health, West Reading, Pennsylvania, and colleagues reported August 16 in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

CKD and ESRD are known to be associated with an increased risk for stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), yet data are limited on the safety and efficacy of LAA closure for stroke prevention in AFib patients with CKD or ESRD, they note.

“It’s important to know about CKD and understand that there may be an association with worse levels of CKD and worse outcomes, but the data that strikes me is really that for end-stage renal disease,” Matthew Sherwood, MD, MHS, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

He noted that data have not been published for patients with CKD and ESRD enrolled in the pivotal PROTECT-AF and PREVAIL trials of Boston Scientific’s Watchman device or from large clinical registries such as EWOLUTION and the company’s continued access protocol registries.

Further, it’s not well understood what the best strategy is to prevent stroke in AFib patients with ESRD and whether they benefit from anticoagulation with warfarin or any of the newer agents. “Thus, it’s hard to then say: ‘Well they have worse outcomes with Watchman,’ which is true as shown in this study, but they may not have any other options based upon the lack of data for oral anticoagulants in end-stage kidney disease patients,” said Dr. Sherwood, from the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Virginia.

The lack of clarity is concerning, given rising atrial fibrillation cases and the prevalence of abnormal renal function in everyday practice. In the present study – involving 21,274 patients undergoing LAA closure between 2016 and 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database – 18.6% of patients had CKD stages I to V and 2.7% had ESRD based on ICD-10 codes.

In-hospital mortality was increased only in patients with ESRD. In all, 3.3% of patients with ESRD and 0.4% of those with no CKD died in hospital (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 6.48), as did 0.5% of patients with CKD (aOR, 11.43; both P <.001).

“These patients represent a sicker population at baseline and have an inherent greater risk for mortality in cardiac interventions, as noted in other studies of structural heart interventions,” Dr. Ahuja and colleagues write.

Patients with CKD had a higher risk for in-hospital stroke or TIA than patients with no CKD (1.8% vs. 1.3%; aOR, 1.35; P = .038) and this risk continued up to 90 days after discharge (1.7% vs. 1.0%; aOR, 1.67; P = .007).

The in-hospital stroke rate was numerically higher in patients with ESRD compared with no CKD (aOR, 1.18; P = .62).

The authors point out that previous LAA closure and CKD studies have reported no differences in in-hospital or subsequent stroke/TIA rates in patients with and without CKD. Possible explanations are that patients with CKD in the present study had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores than those without CKD (4.18 vs. 3.62) and, second, patients with CKD and AFib are known to have higher risk for thromboembolic events than those with AFib without CKD.

CKD patients were also more likely than those without CKD to experience in-hospital acute kidney injury or hemodialysis (aOR, 5.02; P <.001).

CKD has been shown to be independently associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) after LAA closure. AKI may have long-term thromboembolic consequences, the authors suggest, with one study reporting higher stroke risk at midterm follow-up in patients with AKI.

“As with other cardiac interventions in patients with CKD, efforts should be made to optimize preoperative renal function, minimize contrast volume, and avoid abrupt hemodynamic changes such as hypotension during the procedure to prevent AKI,” Dr. Ahuja and colleagues write.

Patients with CKD and ESRD had longer index length of stay than those without CKD but had similar rates of other in-hospital complications, such as systemic embolization, bleeding/transfusion, vascular complications, and pericardial tamponade requiring intervention.

Among the short-term outcomes, 30- and 90-day all-cause readmissions were increased in patients with CKD and ESRD compared with those without CKD, and 30-day bleeding readmissions were increased within the CKD cohort.

“With Watchman and left atrial appendage closure, what we see is that they have higher rates of readmission and other problems,” Dr. Sherwood said. “I think we understand that that’s probably related not to the procedure itself, not because the Watchman doesn’t work for end-stage kidney disease, but because the patients themselves are likely higher risk.”

Commonly used risk scores for atrial fibrillation, however, don’t take into account advanced kidney disease, he added.

Besides the inherent limitations of observational studies, Dr. Sherwood and the authors point to the lack of laboratory variables and procedural variables in the database, the fact that CKD was defined using ICD-10 codes, that outcomes were not clinically adjudicated, that unmeasured confounders likely still exist, and that long-term follow-up is lacking.

Dr. Sherwood, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study, said that the release of outcomes data from CKD and ESRD patients in the major clinical trials would be helpful going forward, as would possible involvement with the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes organization.

“One of the main points of this study is that we just need a lot more research diving into this patient population,” he said.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sherwood reports honoraria from Janssen and Medtronic. Editorial coauthor Sean Pokorney reports research grant support from Gilead, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and the Food and Drug Administration; and advisory board, consulting, and honoraria supports from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Philips, and Zoll.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The presence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is associated with worse in-hospital and short-term outcomes after left atrial appendage (LAA) closure, a nationwide study shows.

Patients with ESRD were particularly vulnerable, having about 6.5-fold higher odds of in-hospital mortality than those without CKD and about 11.5-fold higher odds than those with CKD, even after adjustment for potential confounders.

Patients with CKD had higher rates of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) and more short-term readmissions for bleeding, Keerat Rai Ahuja, MD, Reading Hospital-Tower Health, West Reading, Pennsylvania, and colleagues reported August 16 in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

CKD and ESRD are known to be associated with an increased risk for stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), yet data are limited on the safety and efficacy of LAA closure for stroke prevention in AFib patients with CKD or ESRD, they note.

“It’s important to know about CKD and understand that there may be an association with worse levels of CKD and worse outcomes, but the data that strikes me is really that for end-stage renal disease,” Matthew Sherwood, MD, MHS, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

He noted that data have not been published for patients with CKD and ESRD enrolled in the pivotal PROTECT-AF and PREVAIL trials of Boston Scientific’s Watchman device or from large clinical registries such as EWOLUTION and the company’s continued access protocol registries.

Further, it’s not well understood what the best strategy is to prevent stroke in AFib patients with ESRD and whether they benefit from anticoagulation with warfarin or any of the newer agents. “Thus, it’s hard to then say: ‘Well they have worse outcomes with Watchman,’ which is true as shown in this study, but they may not have any other options based upon the lack of data for oral anticoagulants in end-stage kidney disease patients,” said Dr. Sherwood, from the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Virginia.

The lack of clarity is concerning, given rising atrial fibrillation cases and the prevalence of abnormal renal function in everyday practice. In the present study – involving 21,274 patients undergoing LAA closure between 2016 and 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database – 18.6% of patients had CKD stages I to V and 2.7% had ESRD based on ICD-10 codes.

In-hospital mortality was increased only in patients with ESRD. In all, 3.3% of patients with ESRD and 0.4% of those with no CKD died in hospital (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 6.48), as did 0.5% of patients with CKD (aOR, 11.43; both P <.001).

“These patients represent a sicker population at baseline and have an inherent greater risk for mortality in cardiac interventions, as noted in other studies of structural heart interventions,” Dr. Ahuja and colleagues write.

Patients with CKD had a higher risk for in-hospital stroke or TIA than patients with no CKD (1.8% vs. 1.3%; aOR, 1.35; P = .038) and this risk continued up to 90 days after discharge (1.7% vs. 1.0%; aOR, 1.67; P = .007).

The in-hospital stroke rate was numerically higher in patients with ESRD compared with no CKD (aOR, 1.18; P = .62).

The authors point out that previous LAA closure and CKD studies have reported no differences in in-hospital or subsequent stroke/TIA rates in patients with and without CKD. Possible explanations are that patients with CKD in the present study had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores than those without CKD (4.18 vs. 3.62) and, second, patients with CKD and AFib are known to have higher risk for thromboembolic events than those with AFib without CKD.

CKD patients were also more likely than those without CKD to experience in-hospital acute kidney injury or hemodialysis (aOR, 5.02; P <.001).

CKD has been shown to be independently associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) after LAA closure. AKI may have long-term thromboembolic consequences, the authors suggest, with one study reporting higher stroke risk at midterm follow-up in patients with AKI.

“As with other cardiac interventions in patients with CKD, efforts should be made to optimize preoperative renal function, minimize contrast volume, and avoid abrupt hemodynamic changes such as hypotension during the procedure to prevent AKI,” Dr. Ahuja and colleagues write.

Patients with CKD and ESRD had longer index length of stay than those without CKD but had similar rates of other in-hospital complications, such as systemic embolization, bleeding/transfusion, vascular complications, and pericardial tamponade requiring intervention.

Among the short-term outcomes, 30- and 90-day all-cause readmissions were increased in patients with CKD and ESRD compared with those without CKD, and 30-day bleeding readmissions were increased within the CKD cohort.

“With Watchman and left atrial appendage closure, what we see is that they have higher rates of readmission and other problems,” Dr. Sherwood said. “I think we understand that that’s probably related not to the procedure itself, not because the Watchman doesn’t work for end-stage kidney disease, but because the patients themselves are likely higher risk.”

Commonly used risk scores for atrial fibrillation, however, don’t take into account advanced kidney disease, he added.

Besides the inherent limitations of observational studies, Dr. Sherwood and the authors point to the lack of laboratory variables and procedural variables in the database, the fact that CKD was defined using ICD-10 codes, that outcomes were not clinically adjudicated, that unmeasured confounders likely still exist, and that long-term follow-up is lacking.

Dr. Sherwood, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study, said that the release of outcomes data from CKD and ESRD patients in the major clinical trials would be helpful going forward, as would possible involvement with the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes organization.

“One of the main points of this study is that we just need a lot more research diving into this patient population,” he said.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sherwood reports honoraria from Janssen and Medtronic. Editorial coauthor Sean Pokorney reports research grant support from Gilead, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and the Food and Drug Administration; and advisory board, consulting, and honoraria supports from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Philips, and Zoll.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts debate merits of dual therapy for lupus nephritis

With the approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the calcineurin inhibitor voclosporin (Lupkynis) in January and belimumab (Benlysta) a month before that, clinicians now have new options for treating lupus nephritis in combination with a background immunosuppressive agent, such as mycophenolate mofetil.

But which combination should clinicians choose?

Brad Rovin, MD, a nephrologist with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, who worked on the phase 3 voclosprin trial, pointed to that drug’s fast reduction in proteinuria in a session of the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) 2021 Annual Meeting. That effect on proteinuria is likely due to its effect on podocytes, special epithelial cells that cover the outside of capillaries in the kidney, he said.

These crucial cells have an elaborate cytoskeleton that is stabilized by the protein synaptopodin, which can be subject to harm from calcineurin. But because voclosporin blocks calcineurin, synaptopodin is protected, which consequently protects podocytes and the kidney, Dr. Rovin said.

“There’s a lot of data in the nephrology literature that suggests as you lose podocytes, you actually can develop glomerular sclerosis and loss of renal function,” he said. “In fact, if you lose a critical number of podocytes, then no matter what you do, the kidney is likely to progress to end-stage kidney disease.

“The way I think about it now is, what else do these drugs add? And this idea of preserving the histology of the kidney is really important, and this can be done with voclosporin,” Dr. Rovin said.

Belimumab is also hailed as an effective tool, particularly for the prevention of flares. In the trial leading to its approval), just under 16% of patients experienced a renal-related event or death over 2 years, compared with 28% of the group that received placebo. Those receiving belimumab had a 50% greater chance of reaching the primary efficacy renal response, which was defined as a ratio of urinary protein to creatinine of 0.7 or less, an estimated glomerular filtration rate that was no worse than 20% below the pre-flare value or at least 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and no use of rescue therapy for treatment failure.

The endpoints in the belimumab lupus nephritis trial were “quite rigorous,” Richard A. Furie, MD, said in the same session at the meeting. Patients with class V lupus nephritis were included in the trial, although disease of this severity is known to be particularly difficult to treat, he noted.

“There’s little question that our patients with lupus nephritis will benefit from such a therapeutic approach” with belimumab and mycophenolate, said Dr. Furie, professor of medicine at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, in Hempstead, N.Y. “But regardless of which combination clinicians use, we are making advances, and that means better outcomes for our patients with lupus and lupus nephritis.”

Graciela Alarcon, MD, MPH, professor emeritus of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who moderated the discussion, said there is no sure answer regarding the best choice for clinicians.

“As long as there’s no head-to-head comparison between the two new compounds, I don’t think that the question can be answered,” she said.

Indeed, the answer for many clinicians might be that for certain patients, dual therapy isn’t necessary, Dr. Furie said.

“The fundamental question, before we choose the second drug, is whether a second drug should be chosen,” he said. “There’s a lot of people in the community who are just sticking to the old-fashioned algorithm and that is just choosing one drug, like mycophenolate. ... Others might pick a second drug, but not until they see that mycophenolate is not doing an effective job.”

All agreed that the response rates are still not optimal for patients with lupus nephritis, even with these new combinations – they are still only in the 30%-40% range.

“We haven’t really boosted the response rate to where we want it to be, at least as measured by our current measurements and composite renal response,” Dr. Rovin said.

With voclosporin’s protective effects and belimumab’s flare prevention, the two could potentially be used together at some point, he suggested.

“I think these two drugs show us the possibility that we might use them together and get rid of the older drugs, and really minimize the older drugs and then use them on a longer-term basis to preserve kidney function, as well as keep the lupus in check,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the calcineurin inhibitor voclosporin (Lupkynis) in January and belimumab (Benlysta) a month before that, clinicians now have new options for treating lupus nephritis in combination with a background immunosuppressive agent, such as mycophenolate mofetil.

But which combination should clinicians choose?

Brad Rovin, MD, a nephrologist with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, who worked on the phase 3 voclosprin trial, pointed to that drug’s fast reduction in proteinuria in a session of the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) 2021 Annual Meeting. That effect on proteinuria is likely due to its effect on podocytes, special epithelial cells that cover the outside of capillaries in the kidney, he said.

These crucial cells have an elaborate cytoskeleton that is stabilized by the protein synaptopodin, which can be subject to harm from calcineurin. But because voclosporin blocks calcineurin, synaptopodin is protected, which consequently protects podocytes and the kidney, Dr. Rovin said.

“There’s a lot of data in the nephrology literature that suggests as you lose podocytes, you actually can develop glomerular sclerosis and loss of renal function,” he said. “In fact, if you lose a critical number of podocytes, then no matter what you do, the kidney is likely to progress to end-stage kidney disease.

“The way I think about it now is, what else do these drugs add? And this idea of preserving the histology of the kidney is really important, and this can be done with voclosporin,” Dr. Rovin said.

Belimumab is also hailed as an effective tool, particularly for the prevention of flares. In the trial leading to its approval), just under 16% of patients experienced a renal-related event or death over 2 years, compared with 28% of the group that received placebo. Those receiving belimumab had a 50% greater chance of reaching the primary efficacy renal response, which was defined as a ratio of urinary protein to creatinine of 0.7 or less, an estimated glomerular filtration rate that was no worse than 20% below the pre-flare value or at least 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and no use of rescue therapy for treatment failure.

The endpoints in the belimumab lupus nephritis trial were “quite rigorous,” Richard A. Furie, MD, said in the same session at the meeting. Patients with class V lupus nephritis were included in the trial, although disease of this severity is known to be particularly difficult to treat, he noted.

“There’s little question that our patients with lupus nephritis will benefit from such a therapeutic approach” with belimumab and mycophenolate, said Dr. Furie, professor of medicine at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, in Hempstead, N.Y. “But regardless of which combination clinicians use, we are making advances, and that means better outcomes for our patients with lupus and lupus nephritis.”

Graciela Alarcon, MD, MPH, professor emeritus of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who moderated the discussion, said there is no sure answer regarding the best choice for clinicians.

“As long as there’s no head-to-head comparison between the two new compounds, I don’t think that the question can be answered,” she said.

Indeed, the answer for many clinicians might be that for certain patients, dual therapy isn’t necessary, Dr. Furie said.

“The fundamental question, before we choose the second drug, is whether a second drug should be chosen,” he said. “There’s a lot of people in the community who are just sticking to the old-fashioned algorithm and that is just choosing one drug, like mycophenolate. ... Others might pick a second drug, but not until they see that mycophenolate is not doing an effective job.”

All agreed that the response rates are still not optimal for patients with lupus nephritis, even with these new combinations – they are still only in the 30%-40% range.

“We haven’t really boosted the response rate to where we want it to be, at least as measured by our current measurements and composite renal response,” Dr. Rovin said.

With voclosporin’s protective effects and belimumab’s flare prevention, the two could potentially be used together at some point, he suggested.

“I think these two drugs show us the possibility that we might use them together and get rid of the older drugs, and really minimize the older drugs and then use them on a longer-term basis to preserve kidney function, as well as keep the lupus in check,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the calcineurin inhibitor voclosporin (Lupkynis) in January and belimumab (Benlysta) a month before that, clinicians now have new options for treating lupus nephritis in combination with a background immunosuppressive agent, such as mycophenolate mofetil.

But which combination should clinicians choose?

Brad Rovin, MD, a nephrologist with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, who worked on the phase 3 voclosprin trial, pointed to that drug’s fast reduction in proteinuria in a session of the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) 2021 Annual Meeting. That effect on proteinuria is likely due to its effect on podocytes, special epithelial cells that cover the outside of capillaries in the kidney, he said.

These crucial cells have an elaborate cytoskeleton that is stabilized by the protein synaptopodin, which can be subject to harm from calcineurin. But because voclosporin blocks calcineurin, synaptopodin is protected, which consequently protects podocytes and the kidney, Dr. Rovin said.

“There’s a lot of data in the nephrology literature that suggests as you lose podocytes, you actually can develop glomerular sclerosis and loss of renal function,” he said. “In fact, if you lose a critical number of podocytes, then no matter what you do, the kidney is likely to progress to end-stage kidney disease.

“The way I think about it now is, what else do these drugs add? And this idea of preserving the histology of the kidney is really important, and this can be done with voclosporin,” Dr. Rovin said.

Belimumab is also hailed as an effective tool, particularly for the prevention of flares. In the trial leading to its approval), just under 16% of patients experienced a renal-related event or death over 2 years, compared with 28% of the group that received placebo. Those receiving belimumab had a 50% greater chance of reaching the primary efficacy renal response, which was defined as a ratio of urinary protein to creatinine of 0.7 or less, an estimated glomerular filtration rate that was no worse than 20% below the pre-flare value or at least 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and no use of rescue therapy for treatment failure.

The endpoints in the belimumab lupus nephritis trial were “quite rigorous,” Richard A. Furie, MD, said in the same session at the meeting. Patients with class V lupus nephritis were included in the trial, although disease of this severity is known to be particularly difficult to treat, he noted.

“There’s little question that our patients with lupus nephritis will benefit from such a therapeutic approach” with belimumab and mycophenolate, said Dr. Furie, professor of medicine at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, in Hempstead, N.Y. “But regardless of which combination clinicians use, we are making advances, and that means better outcomes for our patients with lupus and lupus nephritis.”

Graciela Alarcon, MD, MPH, professor emeritus of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who moderated the discussion, said there is no sure answer regarding the best choice for clinicians.

“As long as there’s no head-to-head comparison between the two new compounds, I don’t think that the question can be answered,” she said.

Indeed, the answer for many clinicians might be that for certain patients, dual therapy isn’t necessary, Dr. Furie said.

“The fundamental question, before we choose the second drug, is whether a second drug should be chosen,” he said. “There’s a lot of people in the community who are just sticking to the old-fashioned algorithm and that is just choosing one drug, like mycophenolate. ... Others might pick a second drug, but not until they see that mycophenolate is not doing an effective job.”

All agreed that the response rates are still not optimal for patients with lupus nephritis, even with these new combinations – they are still only in the 30%-40% range.

“We haven’t really boosted the response rate to where we want it to be, at least as measured by our current measurements and composite renal response,” Dr. Rovin said.

With voclosporin’s protective effects and belimumab’s flare prevention, the two could potentially be used together at some point, he suggested.

“I think these two drugs show us the possibility that we might use them together and get rid of the older drugs, and really minimize the older drugs and then use them on a longer-term basis to preserve kidney function, as well as keep the lupus in check,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D pills do not alter kidney function in prediabetes

However, most of these adults with prediabetes plus obesity or overweight also had sufficient serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and a low risk for adverse kidney outcomes at study entry.

“The benefits of vitamin D might be greater in people with low blood vitamin D levels and/or reduced kidney function,” lead author Sun H. Kim, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, speculated in a statement from the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was published online August 6 in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

“The D2d study is unique because we recruited individuals with high-risk prediabetes, having two out of three abnormal glucose values, and we recruited more than 2,000 participants, representing the largest vitamin D diabetes prevention trial to date,” Dr. Kim pointed out.

Although the study did not show a benefit of vitamin D supplements on kidney function outcomes, 43% of participants were already taking up to 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily when they entered the study, she noted.

A subgroup analysis of individuals who were not taking vitamin D at study entry found that vitamin D supplements were associated with lowered proteinuria, “which means that it could have a beneficial effect on kidney health,” said Dr. Kim, cautioning that “additional studies are needed to look into this further.”

Effect of vitamin D on three kidney function outcomes

Although low levels of serum 25(OH)D are associated with kidney disease, few trials have evaluated how vitamin D supplements might affect kidney function, Dr. Kim and colleagues write.

The D2d trial, they note, found that vitamin D supplements did not lower the risk of incident diabetes in people with prediabetes recruited from medical centers across the United States, as previously reported in 2019.

However, since then, meta-analyses that included the D2d trial have reported a significant 11%-12% reduction in diabetes risk in people with prediabetes who took vitamin D supplements.

The current secondary analysis of D2d aimed to investigate whether vitamin D supplements affect kidney function in people with prediabetes.

A total of 2,166 participants in D2d with complete kidney function data were included in the analysis.

The three study outcomes were change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline, change in urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline, and worsening Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) risk score (which takes eGFR and UACR into account).

At baseline, patients were a mean age of 60, had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 32 kg/m2, and 44% were women.

Most (79%) had hypertension, 52% were receiving antihypertensives, and 33% were receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Participants had a mean serum 25(OH) level of 28 ng/mL.

They had a mean eGFR of 87 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a mean UACR of 11 mg/g. Only 10% had a moderate, high, or very high KDIGO risk score.

Participants were randomized to receive a daily gel pill containing 4,000 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or placebo.

Medication adherence was high (83%) in both groups during a median follow-up of 2.9 years.

There was no significant between-group difference in the following kidney function outcomes:

- 28 patients in the vitamin D group and 30 patients in the placebo group had a worsening KDIGO risk score.

- The mean difference in eGFR from baseline was -1.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the vitamin D group and -0.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the placebo group.

- The mean difference in UACR from baseline was 2.7 mg/g in the vitamin D group and 2.0 mg/g in the placebo group.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, most of these adults with prediabetes plus obesity or overweight also had sufficient serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and a low risk for adverse kidney outcomes at study entry.

“The benefits of vitamin D might be greater in people with low blood vitamin D levels and/or reduced kidney function,” lead author Sun H. Kim, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, speculated in a statement from the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was published online August 6 in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

“The D2d study is unique because we recruited individuals with high-risk prediabetes, having two out of three abnormal glucose values, and we recruited more than 2,000 participants, representing the largest vitamin D diabetes prevention trial to date,” Dr. Kim pointed out.

Although the study did not show a benefit of vitamin D supplements on kidney function outcomes, 43% of participants were already taking up to 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily when they entered the study, she noted.

A subgroup analysis of individuals who were not taking vitamin D at study entry found that vitamin D supplements were associated with lowered proteinuria, “which means that it could have a beneficial effect on kidney health,” said Dr. Kim, cautioning that “additional studies are needed to look into this further.”

Effect of vitamin D on three kidney function outcomes

Although low levels of serum 25(OH)D are associated with kidney disease, few trials have evaluated how vitamin D supplements might affect kidney function, Dr. Kim and colleagues write.

The D2d trial, they note, found that vitamin D supplements did not lower the risk of incident diabetes in people with prediabetes recruited from medical centers across the United States, as previously reported in 2019.

However, since then, meta-analyses that included the D2d trial have reported a significant 11%-12% reduction in diabetes risk in people with prediabetes who took vitamin D supplements.

The current secondary analysis of D2d aimed to investigate whether vitamin D supplements affect kidney function in people with prediabetes.

A total of 2,166 participants in D2d with complete kidney function data were included in the analysis.

The three study outcomes were change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline, change in urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline, and worsening Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) risk score (which takes eGFR and UACR into account).

At baseline, patients were a mean age of 60, had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 32 kg/m2, and 44% were women.

Most (79%) had hypertension, 52% were receiving antihypertensives, and 33% were receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Participants had a mean serum 25(OH) level of 28 ng/mL.

They had a mean eGFR of 87 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a mean UACR of 11 mg/g. Only 10% had a moderate, high, or very high KDIGO risk score.

Participants were randomized to receive a daily gel pill containing 4,000 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or placebo.

Medication adherence was high (83%) in both groups during a median follow-up of 2.9 years.

There was no significant between-group difference in the following kidney function outcomes:

- 28 patients in the vitamin D group and 30 patients in the placebo group had a worsening KDIGO risk score.

- The mean difference in eGFR from baseline was -1.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the vitamin D group and -0.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the placebo group.

- The mean difference in UACR from baseline was 2.7 mg/g in the vitamin D group and 2.0 mg/g in the placebo group.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, most of these adults with prediabetes plus obesity or overweight also had sufficient serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and a low risk for adverse kidney outcomes at study entry.

“The benefits of vitamin D might be greater in people with low blood vitamin D levels and/or reduced kidney function,” lead author Sun H. Kim, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, speculated in a statement from the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was published online August 6 in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

“The D2d study is unique because we recruited individuals with high-risk prediabetes, having two out of three abnormal glucose values, and we recruited more than 2,000 participants, representing the largest vitamin D diabetes prevention trial to date,” Dr. Kim pointed out.

Although the study did not show a benefit of vitamin D supplements on kidney function outcomes, 43% of participants were already taking up to 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily when they entered the study, she noted.

A subgroup analysis of individuals who were not taking vitamin D at study entry found that vitamin D supplements were associated with lowered proteinuria, “which means that it could have a beneficial effect on kidney health,” said Dr. Kim, cautioning that “additional studies are needed to look into this further.”

Effect of vitamin D on three kidney function outcomes

Although low levels of serum 25(OH)D are associated with kidney disease, few trials have evaluated how vitamin D supplements might affect kidney function, Dr. Kim and colleagues write.

The D2d trial, they note, found that vitamin D supplements did not lower the risk of incident diabetes in people with prediabetes recruited from medical centers across the United States, as previously reported in 2019.

However, since then, meta-analyses that included the D2d trial have reported a significant 11%-12% reduction in diabetes risk in people with prediabetes who took vitamin D supplements.

The current secondary analysis of D2d aimed to investigate whether vitamin D supplements affect kidney function in people with prediabetes.

A total of 2,166 participants in D2d with complete kidney function data were included in the analysis.

The three study outcomes were change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline, change in urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline, and worsening Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) risk score (which takes eGFR and UACR into account).

At baseline, patients were a mean age of 60, had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 32 kg/m2, and 44% were women.

Most (79%) had hypertension, 52% were receiving antihypertensives, and 33% were receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Participants had a mean serum 25(OH) level of 28 ng/mL.

They had a mean eGFR of 87 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a mean UACR of 11 mg/g. Only 10% had a moderate, high, or very high KDIGO risk score.

Participants were randomized to receive a daily gel pill containing 4,000 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or placebo.

Medication adherence was high (83%) in both groups during a median follow-up of 2.9 years.

There was no significant between-group difference in the following kidney function outcomes:

- 28 patients in the vitamin D group and 30 patients in the placebo group had a worsening KDIGO risk score.

- The mean difference in eGFR from baseline was -1.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the vitamin D group and -0.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the placebo group.

- The mean difference in UACR from baseline was 2.7 mg/g in the vitamin D group and 2.0 mg/g in the placebo group.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

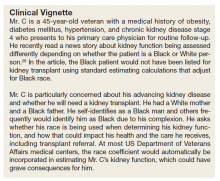

A Step Toward Health Equity for Veterans: Evidence Supports Removing Race From Kidney Function Calculations

The American Medical Association publicly acknowledged in November 2020 that race is a social construct without biological basis, with many other leading medical organizations following suit.1 Historically, biased science based on observed human physical differences has incorrectly asserted a racial biological hierarchy.2,3 Today, leading health care organizations recognize that the effects of racist policies in housing, education, employment, and the criminal justice system contribute to health disparities and have a disproportionately negative impact on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.3,4

Racial classification systems are fraught with bias. Trying to classify a complex and nuanced identity such as race into discrete categories does not capture the extensive heterogeneity at the individual level or within the increasingly diverse, multiracial population.5 Racial and ethnic categories used in collecting census data and research, as defined by the US Office of Management and Budget, have evolved over time.6 These changes in classification are a reflection of changes in the political environment, not changes in scientific knowledge of race and ethnicity.6

The Use of Race in Research and Practice

In the United States, racial minorities bear a disproportionate burden of morbidity and mortality across all major disease categories.3 These disparities cannot be explained by genetics.4 The Human Genome Project in 2003 confirmed that racial categories have no biologic or genetic basis and that there is more intraracial than interracial genetic variation.3 Nevertheless, significant misapplication of race in medical research and clinical practice remains. Instead of attributing observed differences in health outcomes between racial groups to innate physiological differences between the groups, clinicians and researchers must carefully consider the impact of racism.7 This includes considering the complex interactions between socioeconomic, political, and environmental factors, and how they affect health.3

While race is not biologic, the effects of racism can have biologic effects, and advocates appropriately cite the need to collect race as an important category in epidemiological analysis. When race and ethnicity are used as a study variable, bioethicists Kaplan and Bennett recommend that researchers: (1) account for limitations due to imprecision of racial categories; (2) avoid attributing causality when there is an association between race/ethnicity and a health outcome; and (3) refrain from exacerbating racial disparities.6

At the bedside, race has become embedded in clinical, seemingly objective, decision-making tools used across medical specialties.8 These algorithms often use observational outcomes data and draw conclusions by explicitly or implicitly assuming biological differences among races. By crudely adjusting for race without identifying the root cause for observed racial differences, these tools can further magnify health inequities.8 With the increased recognition that race cannot be used as a proxy for genetic ancestry, and that racial and ethnic categories are complex sociopolitical constructs that have changed over time, the practice of race-based medicine is increasingly being criticized.8

This article presents a case for the removal of the race coefficient from estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculations that exacerbate disparities in kidney health by overestimating kidney function in Black patients.8 The main justification for using the race coefficient stems from the disproven assumption that Black people have more muscle mass compared with non-Black people.9 The questioning of this racist assertion has led to a national movement to reevaluate the use of race in eGFR calculations.

Racial Disparities in Kidney Disease

According to epidemiological data published by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and American Society of Nephrology (ASN), 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease (CKD).10 Black Americans make up 13% of the US population yet they account for more than 30% of patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and 35% of those on dialysis.10,11 There is a 3 times greater risk for progression from early-stage CKD to ESKD in Black Americans when compared to the risk for White Americans.11 Black patients are younger at the time of CKD diagnosis and, once diagnosed, experience a faster progression to ESKD.12 These disparities are partially attributable to delays in diagnosis, preventative measures, and referrals to nephrology care.12

In a VA medical center study, although Black patients were referred to nephrology care at higher rates than White patients, Black patients had faster progression to CKD stage 5.13 An earlier study showed that, at any given eGFR, Black patients have higher levels of albuminuria compared to White patients.14 While the reasons behind this observation are likely complex and multifactorial, one hypothesis is that Black patients were already at a more advanced stage of kidney disease at the time of referral as a result of the overestimation of eGFR calculations related to the use of a race coefficient.

Additionally, numerous analyses have revealed that Black patients are less likely to be identified as transplant candidates, less likely to be referred for transplant evaluation and, once on the waiting list, wait longer than do White patients.11,15

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

It is imperative that clinicians have the most accurate measure of GFR to ensure timely diagnosis and appropriate management in patients with CKD. The gold standard for determining renal function requires measuring GFR using an ideal, exogenous, filtration marker such as iothalamate. However, this process is complex and time-consuming, rendering it infeasible in routine care. As a result, we usually estimate GFR using endogenous serum markers such as creatinine and cystatin C. Due to availability and cost, serum creatinine (SCr) is the most widely used marker for estimating kidney function. However, many pitfalls are inherent in its use, including the effects of tubular secretion, extrarenal clearance, and day-to-day variability in creatinine generation related to muscle mass, diet, and activity.16 The 2 most widely used estimation equations are the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation and Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation; both equations incorporate correction factors for age, sex, and race.

The VA uses MDRD, which was derived and validated in a cohort of 1628 patients that included only 197 Black patients (12%), resulting in an eGFR for Black patients that is 21% higher than is the eGFR for non-Black patients with the same SCr value.9 In the VA electronic health record, the race coefficient is incorporated directly into eGFR laboratory calculations based on the race that the veteran self-identified during intake. Because the laboratory reports only a race-adjusted eGFR, there is a lack of transparency as many health care providers and patients are unaware that a race coefficient is used in eGFR calculations at the VA.

Case for Removing Race Coefficient

When applied to cohorts outside the original study, both the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations have proved to be highly biased, imprecise, and inaccurate when compared to measured GFR (mGFR).15,17 For any given eGFR, the possible mGFR may span 3 stages of CKD, underscoring the limitations of using such a crude estimate in clinical decision making.17

Current Kidney Estimation Pitfalls

A recent cohort study by Zelnick and colleagues that included 1658 self-identified Black adults showed less bias between mGFR and eGFR without the use of a race coefficient, and a shorter median time to transplant eligibility by 1.9 years.15 This study provides further evidence that these equations were derived from a biased observational data set that overestimates eGFR in Black patients living with CKD. This overestimation is particularly egregious for frail or malnourished patients with CKD and multiple comorbidities, with many potential harmful clinical consequences.

In addition, multiple international studies in African countries have demonstrated worse performance of eGFR calculations when using the race coefficient than without it. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, eGFR was calculated for adults using MDRD with and without the race coefficient, as well as CKD-EPI with and without the race coefficient, and then compared to mGFR. Both the MDRD and the CKD-EPI equations overestimated GFR when using the race coefficient, and notably the equations without the race coefficient had better correlation to mGFR.18 Similar data were also found in studies from South Africa, the Ivory Coast, Brazil, and Europe.19-22

Clinical Consequences of Race Coefficient Use

The use of a race coefficient in these estimation equations causes adverse clinical outcomes. In early stages of CKD, overestimation of eGFR using the race coefficient can cause an under-recognition of CKD, and can lead to delays in diagnosis and failure to implement measures to slow its progression, such as minimizing drug-related nephrotoxic injury and iatrogenic acute kidney injury. Consequently, a patient with an overestimated eGFR may suffer an accelerated progression to ESKD and premature mortality from cardiovascular disease.23

In advanced CKD stages, eGFR overestimation may result in delayed referral to a nephrologist (recommended at eGFR < 30mL/min/1.73 m2), nutrition counseling, renal replacement therapy education, timely referral for renal replacement therapy access placement, and transplant evaluation (can be listed when eGFR < 20 mL/min/1.73 m2).16,24,25

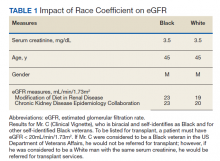

In the Clinical Vignette, it is clear from the information presented that Mr. C’s concerns are well-founded. Table 1 presents the impact on eGFR caused by the race coefficient using the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations. In many VA systems, this overestimation would prevent him from being referred for a kidney transplant at this visit, thereby perpetuating racial health disparities in kidney transplantation.

Concerns About Removal of Race From eGFR Calculations

Opponents of removing the race coefficient assert that a lower eGFR will preclude some patients from qualifying for medications such as metformin and certain anticoagulants, or that it may result in subtherapeutic dosing of drugs such as antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents.26 These recommendations are in place for patient safety, so conversely maintaining the race coefficient and overestimating eGFR will expose some patients to medication toxicity. Another fear is that lower eGFRs will have the unintended consequence of limiting the kidney donor pool. However, this can be prevented by following current guidelines to use mGFR in settings where accurate GFR is imperative.16 Additionally, some nephrologists have expressed concern that diagnosing more patients with advanced stages of CKD will result in inappropriately early initiation of dialysis. Again, this risk can be mitigated by ensuring that nephrologists consider multiple clinical factors and data points, not simply eGFR when deciding to initiate dialysis. Also, an increase in referrals to nephrology may occur when the race coefficient is removed and increased wait times at some VA medical centers could be a concern. An increase in appropriate referrals would show that removing the race coefficient was having its intended effect—more veterans with advanced CKD being seen by nephrologists.

When considering the lack of biological plausibility, inaccuracy, and the clinical harms associated with the use of the race coefficient in eGFR calculations, the benefits of removing the race coefficient from eGFR calculations within the VA far outweigh any potential risks.

A Call for Equity

The National Conversation on Race and eGFR

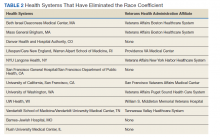

To advance health equity, members of the medical community have advocated for the removal of the race coefficient from eGFR calculations for years. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center was the first establishment to institute this change in 2017. Since then, many health systems across the country that are affiliated with Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers have removed the race coefficient from eGFR equations (Table 2). Many other hospital systems are contemplating this change.

In July 2020, the NKF and the ASN established a joint task force dedicated to reassessing the inclusion of race in eGFR calculations. This task force acknowledges that race is a social, not biological, construct.12 The NKF/ASN task force is now in the second of its 3-phase process. In March 2021, prior to publication of their phase 1 findings, they announced “(1) race modifiers should not be included in equations to estimate kidney function; and (2) current race-based equations should be replaced by a suitable approach that is accurate, inclusive, and standardized in every laboratory in the United States. Any such approach must not differentially introduce bias, inaccuracy, or inequalities.”27

Health Equity in the VHA

In January 2021, President Biden issued an executive order to advance racial equity and support underserved communities through the federal government and its agencies. The VHA is the largest integrated health care system in the United States serving 9 million veterans and is one of the largest federal agencies. As VA clinicians, it is our responsibility to examine the evidence, consider national guidance, and ensure health equity for veterans by practicing unbiased medicine. The evidence and the interim guidance from the NKF-ASN task force clearly indicate that the race coefficient should no longer be used.27 It is imperative that we make these changes immediately knowing that the use of race in kidney function calculators is harming Black veterans. Similar to finding evidence of harm in a treatment group in a clinical trial, it is unethical to wait. Removal of the race coefficient in eGFR calculations will allow VHA clinicians to provide timely and high-quality care to our patients as well as establish the VHA as a national leader in health equity.

VISN 12 Leads the Way

On May 11, 2021, the VA Great Lakes Health Care System, Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 12, leaders responded to this author group’s call to advance health equity and voted to remove the race coefficient from eGFR calculations. Other VISNs should follow, and the VHA should continue to work with national leaders and experts to establish and implement superior tools to ensure the highest quality of kidney health care for all veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the medical students across the nation who have been leading the charge on this important issue. The authors are also thankful for the collaboration and support of all members of the Jesse Brown for Black Lives (JB4BL) Task Force.

1. American Medical Association. New AMA policies recognize race as a social, not biological, construct. Published November 16, 2020. Accessed July 16, 2021. www.ama|-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/new-ama-policies-recognize-race-social-not-biological-construct

2. Bennett L. The Shaping of Black America. Johnson Publishing Co; 1975.

3. David R, Collins J Jr. Disparities in infant mortality: what’s genetics got to do with it? Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1191-1197. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.068387

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Media statement from CDC director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, on racism and health. Published April 8, 2021. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0408-racism-health.html

5. Bonham VL, Green ED, Pérez-Stable EJ. Examining how race, ethnicity, and ancestry data are used in biomedical research. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1533-1534. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.13609

6. Kaplan JB, Bennett T. Use of race and ethnicity in biomedical publication. JAMA. 2003;289(20):2709-2716. doi:10.1001/jama.289.20.2709

7. Braun L, Wentz A, Baker R, Richardson E, Tsai J. Racialized algorithms for kidney function: Erasing social experience. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268:113548. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113548

8. Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight - reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874-882. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2004740

9. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461-470. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002

10. National Kidney Foundation and American Society of Nephrology. Establishing a task force to reassess the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney diseases. Published July 2, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.kidney.org/news/establishing-task-force-to-reassess-inclusion-race-diagnosing-kidney-diseases

11. Norton JM, Moxey-Mims MM, Eggers PW, et al. Social determinants of racial disparities in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(9):2576-2595. doi:10.1681/ASN.201601002712. Delgado C, Baweja M, Burrows NR, et al. Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Diseases: An Interim Report from the NKF-ASN Task Force. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(6):1305-1317. doi:10.1681/ASN.2021010039

13. Suarez J, Cohen JB, Potluri V, et al. Racial disparities in nephrology consultation and disease progression among veterans with CKD: an observational cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(10):2563-2573. doi:10.1681/ASN.2018040344

14. McClellan WM, Warnock DG, Judd S, et al. Albuminuria and racial disparities in the risk for ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(9):1721-1728. doi:10.1681/ASN.2010101085

15. Zelnick LR, Leca N, Young B, Bansal N. Association of the estimated glomerular filtration rate with vs without a coefficient for race with time to eligibility for kidney transplant. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034004. Published 2021 Jan 4. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34004

16. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Published January 2013. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf

17. Sehgal AR. Race and the false precision of glomerular filtration rate estimates. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):1008-1009. doi:10.7326/M20-4951

18. Bukabau JB, Sumaili EK, Cavalier E, et al. Performance of glomerular filtration rate estimation equations in Congolese healthy adults: the inopportunity of the ethnic correction. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193384. Published 2018 Mar 2. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193384

19. van Deventer HE, George JA, Paiker JE, Becker PJ, Katz IJ. Estimating glomerular filtration rate in black South Africans by use of the modification of diet in renal disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations. Clin Chem. 2008;54(7):1197-1202. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.099085

20. Sagou Yayo É, Aye M, Konan JL, et al. Inadéquation du facteur ethnique pour l’estimation du débit de filtration glomérulaire en population générale noire-africaine : résultats en Côte d’Ivoire [Inadequacy of the African-American ethnic factor to estimate glomerular filtration rate in an African general population: results from Côte d›Ivoire]. Nephrol Ther. 2016;12(6):454-459. doi:10.1016/j.nephro.2016.03.006

21. Zanocco JA, Nishida SK, Passos MT, et al. Race adjustment for estimating glomerular filtration rate is not always necessary. Nephron Extra. 2012;2(1):293-302. doi:10.1159/000343899

22. Flamant M, Vidal-Petiot E, Metzger M, et al. Performance of GFR estimating equations in African Europeans: basis for a lower race-ethnicity factor than in African Americans. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(1):182-184. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.015

23. Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, et al. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2021;99(1):34-47. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.012

24. Eneanya ND, Yang W, Reese PP. Reconsidering the consequences of using race to estimate kidney function. JAMA. 2019;322(2):113-114. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.5774

25. Diao JA, Wu GJ, Taylor HA, et al. Clinical implications of removing race from estimates of kidney function. JAMA. 2021;325(2):184-186. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.22124

26. Diao JA, Inker LA, Levey AS, Tighiouart H, Powe NR, Manrai AK. In search of a better equation - performance and equity in estimates of kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):396-399. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2028243

27. National Kidney Foundation and American Society of Nephrology. [Letter]. Published March 05, 2021. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://www.asn-online.org/g/blast/files/NKF-ASN-eGFR-March2021.pdf

28. Waddell K. Medical algorithms have a race problem. Consumer Reports. September 18, 2020. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://www.consumerreports.org/medical-tests/medical-algorithms-have-a-race-problem

The American Medical Association publicly acknowledged in November 2020 that race is a social construct without biological basis, with many other leading medical organizations following suit.1 Historically, biased science based on observed human physical differences has incorrectly asserted a racial biological hierarchy.2,3 Today, leading health care organizations recognize that the effects of racist policies in housing, education, employment, and the criminal justice system contribute to health disparities and have a disproportionately negative impact on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.3,4

Racial classification systems are fraught with bias. Trying to classify a complex and nuanced identity such as race into discrete categories does not capture the extensive heterogeneity at the individual level or within the increasingly diverse, multiracial population.5 Racial and ethnic categories used in collecting census data and research, as defined by the US Office of Management and Budget, have evolved over time.6 These changes in classification are a reflection of changes in the political environment, not changes in scientific knowledge of race and ethnicity.6

The Use of Race in Research and Practice

In the United States, racial minorities bear a disproportionate burden of morbidity and mortality across all major disease categories.3 These disparities cannot be explained by genetics.4 The Human Genome Project in 2003 confirmed that racial categories have no biologic or genetic basis and that there is more intraracial than interracial genetic variation.3 Nevertheless, significant misapplication of race in medical research and clinical practice remains. Instead of attributing observed differences in health outcomes between racial groups to innate physiological differences between the groups, clinicians and researchers must carefully consider the impact of racism.7 This includes considering the complex interactions between socioeconomic, political, and environmental factors, and how they affect health.3

While race is not biologic, the effects of racism can have biologic effects, and advocates appropriately cite the need to collect race as an important category in epidemiological analysis. When race and ethnicity are used as a study variable, bioethicists Kaplan and Bennett recommend that researchers: (1) account for limitations due to imprecision of racial categories; (2) avoid attributing causality when there is an association between race/ethnicity and a health outcome; and (3) refrain from exacerbating racial disparities.6

At the bedside, race has become embedded in clinical, seemingly objective, decision-making tools used across medical specialties.8 These algorithms often use observational outcomes data and draw conclusions by explicitly or implicitly assuming biological differences among races. By crudely adjusting for race without identifying the root cause for observed racial differences, these tools can further magnify health inequities.8 With the increased recognition that race cannot be used as a proxy for genetic ancestry, and that racial and ethnic categories are complex sociopolitical constructs that have changed over time, the practice of race-based medicine is increasingly being criticized.8

This article presents a case for the removal of the race coefficient from estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculations that exacerbate disparities in kidney health by overestimating kidney function in Black patients.8 The main justification for using the race coefficient stems from the disproven assumption that Black people have more muscle mass compared with non-Black people.9 The questioning of this racist assertion has led to a national movement to reevaluate the use of race in eGFR calculations.

Racial Disparities in Kidney Disease

According to epidemiological data published by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and American Society of Nephrology (ASN), 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease (CKD).10 Black Americans make up 13% of the US population yet they account for more than 30% of patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and 35% of those on dialysis.10,11 There is a 3 times greater risk for progression from early-stage CKD to ESKD in Black Americans when compared to the risk for White Americans.11 Black patients are younger at the time of CKD diagnosis and, once diagnosed, experience a faster progression to ESKD.12 These disparities are partially attributable to delays in diagnosis, preventative measures, and referrals to nephrology care.12

In a VA medical center study, although Black patients were referred to nephrology care at higher rates than White patients, Black patients had faster progression to CKD stage 5.13 An earlier study showed that, at any given eGFR, Black patients have higher levels of albuminuria compared to White patients.14 While the reasons behind this observation are likely complex and multifactorial, one hypothesis is that Black patients were already at a more advanced stage of kidney disease at the time of referral as a result of the overestimation of eGFR calculations related to the use of a race coefficient.

Additionally, numerous analyses have revealed that Black patients are less likely to be identified as transplant candidates, less likely to be referred for transplant evaluation and, once on the waiting list, wait longer than do White patients.11,15

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

It is imperative that clinicians have the most accurate measure of GFR to ensure timely diagnosis and appropriate management in patients with CKD. The gold standard for determining renal function requires measuring GFR using an ideal, exogenous, filtration marker such as iothalamate. However, this process is complex and time-consuming, rendering it infeasible in routine care. As a result, we usually estimate GFR using endogenous serum markers such as creatinine and cystatin C. Due to availability and cost, serum creatinine (SCr) is the most widely used marker for estimating kidney function. However, many pitfalls are inherent in its use, including the effects of tubular secretion, extrarenal clearance, and day-to-day variability in creatinine generation related to muscle mass, diet, and activity.16 The 2 most widely used estimation equations are the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation and Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation; both equations incorporate correction factors for age, sex, and race.

The VA uses MDRD, which was derived and validated in a cohort of 1628 patients that included only 197 Black patients (12%), resulting in an eGFR for Black patients that is 21% higher than is the eGFR for non-Black patients with the same SCr value.9 In the VA electronic health record, the race coefficient is incorporated directly into eGFR laboratory calculations based on the race that the veteran self-identified during intake. Because the laboratory reports only a race-adjusted eGFR, there is a lack of transparency as many health care providers and patients are unaware that a race coefficient is used in eGFR calculations at the VA.

Case for Removing Race Coefficient

When applied to cohorts outside the original study, both the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations have proved to be highly biased, imprecise, and inaccurate when compared to measured GFR (mGFR).15,17 For any given eGFR, the possible mGFR may span 3 stages of CKD, underscoring the limitations of using such a crude estimate in clinical decision making.17

Current Kidney Estimation Pitfalls

A recent cohort study by Zelnick and colleagues that included 1658 self-identified Black adults showed less bias between mGFR and eGFR without the use of a race coefficient, and a shorter median time to transplant eligibility by 1.9 years.15 This study provides further evidence that these equations were derived from a biased observational data set that overestimates eGFR in Black patients living with CKD. This overestimation is particularly egregious for frail or malnourished patients with CKD and multiple comorbidities, with many potential harmful clinical consequences.

In addition, multiple international studies in African countries have demonstrated worse performance of eGFR calculations when using the race coefficient than without it. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, eGFR was calculated for adults using MDRD with and without the race coefficient, as well as CKD-EPI with and without the race coefficient, and then compared to mGFR. Both the MDRD and the CKD-EPI equations overestimated GFR when using the race coefficient, and notably the equations without the race coefficient had better correlation to mGFR.18 Similar data were also found in studies from South Africa, the Ivory Coast, Brazil, and Europe.19-22

Clinical Consequences of Race Coefficient Use

The use of a race coefficient in these estimation equations causes adverse clinical outcomes. In early stages of CKD, overestimation of eGFR using the race coefficient can cause an under-recognition of CKD, and can lead to delays in diagnosis and failure to implement measures to slow its progression, such as minimizing drug-related nephrotoxic injury and iatrogenic acute kidney injury. Consequently, a patient with an overestimated eGFR may suffer an accelerated progression to ESKD and premature mortality from cardiovascular disease.23

In advanced CKD stages, eGFR overestimation may result in delayed referral to a nephrologist (recommended at eGFR < 30mL/min/1.73 m2), nutrition counseling, renal replacement therapy education, timely referral for renal replacement therapy access placement, and transplant evaluation (can be listed when eGFR < 20 mL/min/1.73 m2).16,24,25

In the Clinical Vignette, it is clear from the information presented that Mr. C’s concerns are well-founded. Table 1 presents the impact on eGFR caused by the race coefficient using the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations. In many VA systems, this overestimation would prevent him from being referred for a kidney transplant at this visit, thereby perpetuating racial health disparities in kidney transplantation.

Concerns About Removal of Race From eGFR Calculations

Opponents of removing the race coefficient assert that a lower eGFR will preclude some patients from qualifying for medications such as metformin and certain anticoagulants, or that it may result in subtherapeutic dosing of drugs such as antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents.26 These recommendations are in place for patient safety, so conversely maintaining the race coefficient and overestimating eGFR will expose some patients to medication toxicity. Another fear is that lower eGFRs will have the unintended consequence of limiting the kidney donor pool. However, this can be prevented by following current guidelines to use mGFR in settings where accurate GFR is imperative.16 Additionally, some nephrologists have expressed concern that diagnosing more patients with advanced stages of CKD will result in inappropriately early initiation of dialysis. Again, this risk can be mitigated by ensuring that nephrologists consider multiple clinical factors and data points, not simply eGFR when deciding to initiate dialysis. Also, an increase in referrals to nephrology may occur when the race coefficient is removed and increased wait times at some VA medical centers could be a concern. An increase in appropriate referrals would show that removing the race coefficient was having its intended effect—more veterans with advanced CKD being seen by nephrologists.

When considering the lack of biological plausibility, inaccuracy, and the clinical harms associated with the use of the race coefficient in eGFR calculations, the benefits of removing the race coefficient from eGFR calculations within the VA far outweigh any potential risks.

A Call for Equity

The National Conversation on Race and eGFR