User login

Type 2 diabetes is particularly devastating in adolescents

SAN FRANCISCO – and by the time those with youth-onset diabetes reach their early 20s, they are beset with disease-related complications usually seen in older populations, findings from the RISE and TODAY2 studies have demonstrated.

“Additional research is urgently needed to better understand the reasons for this more serious trajectory,” Philip Zeitler, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. The hope is to identify at-risk children and prevent the disease, but at this point “we don’t know the answer.”

In the meantime, “we are getting more aggressive with bariatric surgery at our center, because nothing else is working as well. It would be nice to move away from that, but these kids are going to die,” he added.

Steven Kahn, MD, of the diabetes Research Center at the University of Washington, Seattle, presented the findings from a comparison of outcomes from the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) studies in adolescents aged 10-19 years and in adults. The RISE Pediatric Medication Study (Diabetes Care. 2018; 41[8]:1717-25) and RISE Adult Medication Study were parallel investigations treatments to preserve or improve beta-cell function.

“This is the first-ever true comparison of outcomes in youth versus adults,” he said. Both arms had the same design and lab measurements, but the differences in outcomes were “very scary,” he added. “The disease is much more aggressive in youth than in adults.”

Among other things, the RISE youth-versus-adult study compared the outcomes after 3 months of insulin glargine followed by 9 months of metformin, or 12 months of metformin in 132 obese adults and 91 obese adolescents with impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. The treatments were stopped after 12 months, and the participants were reevaluated at 15 months. Hyperglycemic clamps were conducted at baseline, 12 months, and 3 months after treatment cessation (Diabetes. 2019 Jun 9. doi: 10.2337/db19-0299).

In adults, treatment improved insulin sensitivity and beta-cell response, but after treatment cessation, they reverted to baseline by the 15-month evaluation. However, there was no improvement in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell response in adolescents, either during treatment or after cessation, and in fact, they were worse off at 15 months than they had been at baseline, with lower insulin secretion and higher hemoglobin A1c.

Those stark differences in outcomes between the adolescents and adults were indicative of a more aggressive disease trajectory for younger patients.

Compliance was not the issue, with more than 80% of both adults and children taking more than 80% of their medications, Dr. Kahn said.

He suggested that adolescents might have a different underlying pathology that makes it worse to develop diabetes during puberty, which is already an insulin-resistant state. But, whatever the case, there is an “urgent need” to better understand the differences between adolescents and adults and to find better treatments for younger patients with diabetes, he said.

In regard to using weight loss as a means of treatment or prevention, Dr. Zeitler emphasized that type 2 diabetes in younger patients “occurs in a context of very low socioeconomic status, family dysfunction, and a great deal of stress and [family] illness. It’s often a complex situation and it’s difficult to accomplish effective lifestyle change when families are struggling to have afford quality food, facing challenges of family and neighborhood violence, and working multiple jobs.”

The RISE findings of a more aggressive deterioration in beta-cell function for younger patients were reflected in outcomes in the TODAY2 study, which found that adolescents who are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes face severe renal, cardiovascular, eye, and nerve complications by the time they reach their early 20s.

TODAY2 was an 8-year follow-up to the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) trial published in 2012 (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2247-56). Data from the original study of patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes showed that after a roughly 4-year follow-up, almost half of all participants had experienced loss of glycemic control on their original treatment assignment, a rate much higher than that reported in adults. Metformin plus rosiglitazone was superior to metformin alone in maintaining durable glycemic control and metformin plus an intensive lifestyle intervention was intermediate to the other groups, but not significantly different from them. In addition, metformin alone was found to be least effective in non-Hispanic black patients, metformin and rosiglitazone was most effective in girls.

Overall, 517 participants of the original study’s 669 participants are still being followed as part of the TODAY2 trial. They are managed in community practices now and are in their early 20s, on average.

But, less than 10 years down the road from TODAY, the young adults “have problems you’d expect in your grandparents. Target-organ damage is already evident, and serious cardiovascular events are occurring,” Dr. Zeitler said.

Cardiovascular complications

The cardiovascular event rate in TODAY 2 was about the same as is seen in older adults with type 1 diabetes. Overall, there were 38 cardiovascular events in 19 patients for an event rate of 6.4/1,000 patients per year. Those events included heart failure, arrhythmia, coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, deep venous thrombosis, stroke or transient ischemic attack, and vascular insufficiency.

Over that time, the cumulative incidence of elevated LDL cholesterol increased from 3% in the TODAY report to 26% for TODAY2, and for triglycerides, it went from 18% to 35%. The cumulative incidence of hypertension increased from 19% to 55%.

Decline renal function

In regard to renal complications, the cumulative incident curve for microalbuminuria went from 8% at baseline to 40% at 12 years, while macroalbuminuria prevalence increased from 1.5% to 11% during the same time. The cumulative incidence of hyperfiltration increased from 12% to 48%. Risk factors for hyperfiltration included female sex, Hispanic ethnicity, loss of glycemic control, and hypertension, although body mass index was actually associated with lower risk.

So far, there have been four renal events in two patients, who both had chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure, for an event rate of 0.7/1,000 patients per year.

Pregnancy outcomes

Women in the cohort – about two-thirds of the study population – have had high rates of maternal complications, and their offspring also face complications after birth.

There were 306 pregnancies reported, of which there are known outcomes for 53 (TODAY) and 236 (TODAY2). In all, 5% of the total cohort had voluntary elective termination; 9% and 12% of patients, respectively, suffered a miscarriage before 20 weeks; and 4% of pregnancies in the total cohort ended in stillbirth.

Preterm live births more than doubled from 11% to 24%, and full-term deliveries decreased from 62% to 46% in the TODAY2 patients.

In regard to offspring characteristics, average birth weight in the total cohort was just over 4.5 pounds (national average, 7.3 pounds), and the prevalence of very low birth weight more than doubled from 8% to 16% at the 12-year mark. The prevalence of macrosomia was 19% for the cohort, more than double the national average of 8%. In all, 5% and 7% of offspring were small for gestational age, whereas 22% and 26% of offspring were large for gestational age.

Among other complications, respiratory distress occurred in 8% and 14% of offspring, and cardiac anomalies occurred in 10% and 9%, which, although they held steady across the cohorts, were significantly higher than the national average of 1%. Similarly, neonatal hypoglycemia occurred in 17% and 29% of offspring, again, notably higher than the national average of 2%. Offspring outcomes were worse in mothers with loss of glycemic control.

In regard to maternal pregnancy complications, the rate of hospitalization before delivery increased from 25% to 36%; hypertension increased in prevalence from 19% to 36%; and while macroalbuminuria held steady at 9.4%, microalbuminuria increased from 6% to 8%. Thirty-three percent of the TODAY2 cohort had a hemoglobin A1c level of more than 8%.

Retinopathy

Serious eye problems were common, with notable progression seen in diabetic retinopathy in patients who had fundus photos taken in 2011 (TODAY) and 2018 (TODAY2). Among the patients, 86% and 51%, respectively, of 371 patients had no definitive diabetic retinopathy; 14% and 22% of patients had very mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR); and 0% and 16% of patients had mild NPDR. None of the TODAY patients had early or high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy, compared with 3% and 1%, respectively, in TODAY2. Risk factors included loss of glycemic control (hazard ratio, 19.23; 95% confidence interval, 4.62-80.07).

None of the TODAY patients had macular edema, whereas it occurred in 4% of TODAY2 patients. In all, there were 142 adjudicated eye-related events reported for 92 patients, for an event rate of 15.5/1,000 patients per year. The events included NPDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, macular edema, cataracts, glaucoma, and vitreous hemorrhage).

Neuropathy

The prevalence of diabetic neuropathy also increased over the duration of follow-up, rising to 28%-33% based on Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument scores. There were 14 adjudicated events reported for 12 patients (2.4 events/1,000 patients per year), including peripheral diabetic neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, and diabetic mononeuropathy.

“We’ve had a number of amputations; quite a number of toes are now missing in this group of kids,” Dr. Zeitler said.

There have been five deaths so far: one heart attack, one renal failure, one overwhelming sepsis, one postop cardiac arrest, and a drug overdose.

Dr. Zeitler was the senior author on 2018 updated ADA guidelines for managing youth-onset type 2 diabetes. The recommendations where extensively shaped by the TODAY findings and were more aggressive than those previously put forward, suggesting, among other things, hemoglobin A1c targets of 6.5%-7%; earlier treatment with insulin; and stricter management of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and proteinuria (Diabetes Care. 2018;41[12]:2648-68).

The National Institute of Diabetes & Kidney disease funded the studies. The presenters reported no relevant disclosures or conflicts of interest.

This article was updated 7/22/19.

SAN FRANCISCO – and by the time those with youth-onset diabetes reach their early 20s, they are beset with disease-related complications usually seen in older populations, findings from the RISE and TODAY2 studies have demonstrated.

“Additional research is urgently needed to better understand the reasons for this more serious trajectory,” Philip Zeitler, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. The hope is to identify at-risk children and prevent the disease, but at this point “we don’t know the answer.”

In the meantime, “we are getting more aggressive with bariatric surgery at our center, because nothing else is working as well. It would be nice to move away from that, but these kids are going to die,” he added.

Steven Kahn, MD, of the diabetes Research Center at the University of Washington, Seattle, presented the findings from a comparison of outcomes from the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) studies in adolescents aged 10-19 years and in adults. The RISE Pediatric Medication Study (Diabetes Care. 2018; 41[8]:1717-25) and RISE Adult Medication Study were parallel investigations treatments to preserve or improve beta-cell function.

“This is the first-ever true comparison of outcomes in youth versus adults,” he said. Both arms had the same design and lab measurements, but the differences in outcomes were “very scary,” he added. “The disease is much more aggressive in youth than in adults.”

Among other things, the RISE youth-versus-adult study compared the outcomes after 3 months of insulin glargine followed by 9 months of metformin, or 12 months of metformin in 132 obese adults and 91 obese adolescents with impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. The treatments were stopped after 12 months, and the participants were reevaluated at 15 months. Hyperglycemic clamps were conducted at baseline, 12 months, and 3 months after treatment cessation (Diabetes. 2019 Jun 9. doi: 10.2337/db19-0299).

In adults, treatment improved insulin sensitivity and beta-cell response, but after treatment cessation, they reverted to baseline by the 15-month evaluation. However, there was no improvement in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell response in adolescents, either during treatment or after cessation, and in fact, they were worse off at 15 months than they had been at baseline, with lower insulin secretion and higher hemoglobin A1c.

Those stark differences in outcomes between the adolescents and adults were indicative of a more aggressive disease trajectory for younger patients.

Compliance was not the issue, with more than 80% of both adults and children taking more than 80% of their medications, Dr. Kahn said.

He suggested that adolescents might have a different underlying pathology that makes it worse to develop diabetes during puberty, which is already an insulin-resistant state. But, whatever the case, there is an “urgent need” to better understand the differences between adolescents and adults and to find better treatments for younger patients with diabetes, he said.

In regard to using weight loss as a means of treatment or prevention, Dr. Zeitler emphasized that type 2 diabetes in younger patients “occurs in a context of very low socioeconomic status, family dysfunction, and a great deal of stress and [family] illness. It’s often a complex situation and it’s difficult to accomplish effective lifestyle change when families are struggling to have afford quality food, facing challenges of family and neighborhood violence, and working multiple jobs.”

The RISE findings of a more aggressive deterioration in beta-cell function for younger patients were reflected in outcomes in the TODAY2 study, which found that adolescents who are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes face severe renal, cardiovascular, eye, and nerve complications by the time they reach their early 20s.

TODAY2 was an 8-year follow-up to the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) trial published in 2012 (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2247-56). Data from the original study of patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes showed that after a roughly 4-year follow-up, almost half of all participants had experienced loss of glycemic control on their original treatment assignment, a rate much higher than that reported in adults. Metformin plus rosiglitazone was superior to metformin alone in maintaining durable glycemic control and metformin plus an intensive lifestyle intervention was intermediate to the other groups, but not significantly different from them. In addition, metformin alone was found to be least effective in non-Hispanic black patients, metformin and rosiglitazone was most effective in girls.

Overall, 517 participants of the original study’s 669 participants are still being followed as part of the TODAY2 trial. They are managed in community practices now and are in their early 20s, on average.

But, less than 10 years down the road from TODAY, the young adults “have problems you’d expect in your grandparents. Target-organ damage is already evident, and serious cardiovascular events are occurring,” Dr. Zeitler said.

Cardiovascular complications

The cardiovascular event rate in TODAY 2 was about the same as is seen in older adults with type 1 diabetes. Overall, there were 38 cardiovascular events in 19 patients for an event rate of 6.4/1,000 patients per year. Those events included heart failure, arrhythmia, coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, deep venous thrombosis, stroke or transient ischemic attack, and vascular insufficiency.

Over that time, the cumulative incidence of elevated LDL cholesterol increased from 3% in the TODAY report to 26% for TODAY2, and for triglycerides, it went from 18% to 35%. The cumulative incidence of hypertension increased from 19% to 55%.

Decline renal function

In regard to renal complications, the cumulative incident curve for microalbuminuria went from 8% at baseline to 40% at 12 years, while macroalbuminuria prevalence increased from 1.5% to 11% during the same time. The cumulative incidence of hyperfiltration increased from 12% to 48%. Risk factors for hyperfiltration included female sex, Hispanic ethnicity, loss of glycemic control, and hypertension, although body mass index was actually associated with lower risk.

So far, there have been four renal events in two patients, who both had chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure, for an event rate of 0.7/1,000 patients per year.

Pregnancy outcomes

Women in the cohort – about two-thirds of the study population – have had high rates of maternal complications, and their offspring also face complications after birth.

There were 306 pregnancies reported, of which there are known outcomes for 53 (TODAY) and 236 (TODAY2). In all, 5% of the total cohort had voluntary elective termination; 9% and 12% of patients, respectively, suffered a miscarriage before 20 weeks; and 4% of pregnancies in the total cohort ended in stillbirth.

Preterm live births more than doubled from 11% to 24%, and full-term deliveries decreased from 62% to 46% in the TODAY2 patients.

In regard to offspring characteristics, average birth weight in the total cohort was just over 4.5 pounds (national average, 7.3 pounds), and the prevalence of very low birth weight more than doubled from 8% to 16% at the 12-year mark. The prevalence of macrosomia was 19% for the cohort, more than double the national average of 8%. In all, 5% and 7% of offspring were small for gestational age, whereas 22% and 26% of offspring were large for gestational age.

Among other complications, respiratory distress occurred in 8% and 14% of offspring, and cardiac anomalies occurred in 10% and 9%, which, although they held steady across the cohorts, were significantly higher than the national average of 1%. Similarly, neonatal hypoglycemia occurred in 17% and 29% of offspring, again, notably higher than the national average of 2%. Offspring outcomes were worse in mothers with loss of glycemic control.

In regard to maternal pregnancy complications, the rate of hospitalization before delivery increased from 25% to 36%; hypertension increased in prevalence from 19% to 36%; and while macroalbuminuria held steady at 9.4%, microalbuminuria increased from 6% to 8%. Thirty-three percent of the TODAY2 cohort had a hemoglobin A1c level of more than 8%.

Retinopathy

Serious eye problems were common, with notable progression seen in diabetic retinopathy in patients who had fundus photos taken in 2011 (TODAY) and 2018 (TODAY2). Among the patients, 86% and 51%, respectively, of 371 patients had no definitive diabetic retinopathy; 14% and 22% of patients had very mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR); and 0% and 16% of patients had mild NPDR. None of the TODAY patients had early or high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy, compared with 3% and 1%, respectively, in TODAY2. Risk factors included loss of glycemic control (hazard ratio, 19.23; 95% confidence interval, 4.62-80.07).

None of the TODAY patients had macular edema, whereas it occurred in 4% of TODAY2 patients. In all, there were 142 adjudicated eye-related events reported for 92 patients, for an event rate of 15.5/1,000 patients per year. The events included NPDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, macular edema, cataracts, glaucoma, and vitreous hemorrhage).

Neuropathy

The prevalence of diabetic neuropathy also increased over the duration of follow-up, rising to 28%-33% based on Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument scores. There were 14 adjudicated events reported for 12 patients (2.4 events/1,000 patients per year), including peripheral diabetic neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, and diabetic mononeuropathy.

“We’ve had a number of amputations; quite a number of toes are now missing in this group of kids,” Dr. Zeitler said.

There have been five deaths so far: one heart attack, one renal failure, one overwhelming sepsis, one postop cardiac arrest, and a drug overdose.

Dr. Zeitler was the senior author on 2018 updated ADA guidelines for managing youth-onset type 2 diabetes. The recommendations where extensively shaped by the TODAY findings and were more aggressive than those previously put forward, suggesting, among other things, hemoglobin A1c targets of 6.5%-7%; earlier treatment with insulin; and stricter management of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and proteinuria (Diabetes Care. 2018;41[12]:2648-68).

The National Institute of Diabetes & Kidney disease funded the studies. The presenters reported no relevant disclosures or conflicts of interest.

This article was updated 7/22/19.

SAN FRANCISCO – and by the time those with youth-onset diabetes reach their early 20s, they are beset with disease-related complications usually seen in older populations, findings from the RISE and TODAY2 studies have demonstrated.

“Additional research is urgently needed to better understand the reasons for this more serious trajectory,” Philip Zeitler, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. The hope is to identify at-risk children and prevent the disease, but at this point “we don’t know the answer.”

In the meantime, “we are getting more aggressive with bariatric surgery at our center, because nothing else is working as well. It would be nice to move away from that, but these kids are going to die,” he added.

Steven Kahn, MD, of the diabetes Research Center at the University of Washington, Seattle, presented the findings from a comparison of outcomes from the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) studies in adolescents aged 10-19 years and in adults. The RISE Pediatric Medication Study (Diabetes Care. 2018; 41[8]:1717-25) and RISE Adult Medication Study were parallel investigations treatments to preserve or improve beta-cell function.

“This is the first-ever true comparison of outcomes in youth versus adults,” he said. Both arms had the same design and lab measurements, but the differences in outcomes were “very scary,” he added. “The disease is much more aggressive in youth than in adults.”

Among other things, the RISE youth-versus-adult study compared the outcomes after 3 months of insulin glargine followed by 9 months of metformin, or 12 months of metformin in 132 obese adults and 91 obese adolescents with impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. The treatments were stopped after 12 months, and the participants were reevaluated at 15 months. Hyperglycemic clamps were conducted at baseline, 12 months, and 3 months after treatment cessation (Diabetes. 2019 Jun 9. doi: 10.2337/db19-0299).

In adults, treatment improved insulin sensitivity and beta-cell response, but after treatment cessation, they reverted to baseline by the 15-month evaluation. However, there was no improvement in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell response in adolescents, either during treatment or after cessation, and in fact, they were worse off at 15 months than they had been at baseline, with lower insulin secretion and higher hemoglobin A1c.

Those stark differences in outcomes between the adolescents and adults were indicative of a more aggressive disease trajectory for younger patients.

Compliance was not the issue, with more than 80% of both adults and children taking more than 80% of their medications, Dr. Kahn said.

He suggested that adolescents might have a different underlying pathology that makes it worse to develop diabetes during puberty, which is already an insulin-resistant state. But, whatever the case, there is an “urgent need” to better understand the differences between adolescents and adults and to find better treatments for younger patients with diabetes, he said.

In regard to using weight loss as a means of treatment or prevention, Dr. Zeitler emphasized that type 2 diabetes in younger patients “occurs in a context of very low socioeconomic status, family dysfunction, and a great deal of stress and [family] illness. It’s often a complex situation and it’s difficult to accomplish effective lifestyle change when families are struggling to have afford quality food, facing challenges of family and neighborhood violence, and working multiple jobs.”

The RISE findings of a more aggressive deterioration in beta-cell function for younger patients were reflected in outcomes in the TODAY2 study, which found that adolescents who are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes face severe renal, cardiovascular, eye, and nerve complications by the time they reach their early 20s.

TODAY2 was an 8-year follow-up to the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) trial published in 2012 (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2247-56). Data from the original study of patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes showed that after a roughly 4-year follow-up, almost half of all participants had experienced loss of glycemic control on their original treatment assignment, a rate much higher than that reported in adults. Metformin plus rosiglitazone was superior to metformin alone in maintaining durable glycemic control and metformin plus an intensive lifestyle intervention was intermediate to the other groups, but not significantly different from them. In addition, metformin alone was found to be least effective in non-Hispanic black patients, metformin and rosiglitazone was most effective in girls.

Overall, 517 participants of the original study’s 669 participants are still being followed as part of the TODAY2 trial. They are managed in community practices now and are in their early 20s, on average.

But, less than 10 years down the road from TODAY, the young adults “have problems you’d expect in your grandparents. Target-organ damage is already evident, and serious cardiovascular events are occurring,” Dr. Zeitler said.

Cardiovascular complications

The cardiovascular event rate in TODAY 2 was about the same as is seen in older adults with type 1 diabetes. Overall, there were 38 cardiovascular events in 19 patients for an event rate of 6.4/1,000 patients per year. Those events included heart failure, arrhythmia, coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, deep venous thrombosis, stroke or transient ischemic attack, and vascular insufficiency.

Over that time, the cumulative incidence of elevated LDL cholesterol increased from 3% in the TODAY report to 26% for TODAY2, and for triglycerides, it went from 18% to 35%. The cumulative incidence of hypertension increased from 19% to 55%.

Decline renal function

In regard to renal complications, the cumulative incident curve for microalbuminuria went from 8% at baseline to 40% at 12 years, while macroalbuminuria prevalence increased from 1.5% to 11% during the same time. The cumulative incidence of hyperfiltration increased from 12% to 48%. Risk factors for hyperfiltration included female sex, Hispanic ethnicity, loss of glycemic control, and hypertension, although body mass index was actually associated with lower risk.

So far, there have been four renal events in two patients, who both had chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure, for an event rate of 0.7/1,000 patients per year.

Pregnancy outcomes

Women in the cohort – about two-thirds of the study population – have had high rates of maternal complications, and their offspring also face complications after birth.

There were 306 pregnancies reported, of which there are known outcomes for 53 (TODAY) and 236 (TODAY2). In all, 5% of the total cohort had voluntary elective termination; 9% and 12% of patients, respectively, suffered a miscarriage before 20 weeks; and 4% of pregnancies in the total cohort ended in stillbirth.

Preterm live births more than doubled from 11% to 24%, and full-term deliveries decreased from 62% to 46% in the TODAY2 patients.

In regard to offspring characteristics, average birth weight in the total cohort was just over 4.5 pounds (national average, 7.3 pounds), and the prevalence of very low birth weight more than doubled from 8% to 16% at the 12-year mark. The prevalence of macrosomia was 19% for the cohort, more than double the national average of 8%. In all, 5% and 7% of offspring were small for gestational age, whereas 22% and 26% of offspring were large for gestational age.

Among other complications, respiratory distress occurred in 8% and 14% of offspring, and cardiac anomalies occurred in 10% and 9%, which, although they held steady across the cohorts, were significantly higher than the national average of 1%. Similarly, neonatal hypoglycemia occurred in 17% and 29% of offspring, again, notably higher than the national average of 2%. Offspring outcomes were worse in mothers with loss of glycemic control.

In regard to maternal pregnancy complications, the rate of hospitalization before delivery increased from 25% to 36%; hypertension increased in prevalence from 19% to 36%; and while macroalbuminuria held steady at 9.4%, microalbuminuria increased from 6% to 8%. Thirty-three percent of the TODAY2 cohort had a hemoglobin A1c level of more than 8%.

Retinopathy

Serious eye problems were common, with notable progression seen in diabetic retinopathy in patients who had fundus photos taken in 2011 (TODAY) and 2018 (TODAY2). Among the patients, 86% and 51%, respectively, of 371 patients had no definitive diabetic retinopathy; 14% and 22% of patients had very mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR); and 0% and 16% of patients had mild NPDR. None of the TODAY patients had early or high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy, compared with 3% and 1%, respectively, in TODAY2. Risk factors included loss of glycemic control (hazard ratio, 19.23; 95% confidence interval, 4.62-80.07).

None of the TODAY patients had macular edema, whereas it occurred in 4% of TODAY2 patients. In all, there were 142 adjudicated eye-related events reported for 92 patients, for an event rate of 15.5/1,000 patients per year. The events included NPDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, macular edema, cataracts, glaucoma, and vitreous hemorrhage).

Neuropathy

The prevalence of diabetic neuropathy also increased over the duration of follow-up, rising to 28%-33% based on Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument scores. There were 14 adjudicated events reported for 12 patients (2.4 events/1,000 patients per year), including peripheral diabetic neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, and diabetic mononeuropathy.

“We’ve had a number of amputations; quite a number of toes are now missing in this group of kids,” Dr. Zeitler said.

There have been five deaths so far: one heart attack, one renal failure, one overwhelming sepsis, one postop cardiac arrest, and a drug overdose.

Dr. Zeitler was the senior author on 2018 updated ADA guidelines for managing youth-onset type 2 diabetes. The recommendations where extensively shaped by the TODAY findings and were more aggressive than those previously put forward, suggesting, among other things, hemoglobin A1c targets of 6.5%-7%; earlier treatment with insulin; and stricter management of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and proteinuria (Diabetes Care. 2018;41[12]:2648-68).

The National Institute of Diabetes & Kidney disease funded the studies. The presenters reported no relevant disclosures or conflicts of interest.

This article was updated 7/22/19.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ADA 2019

The FDA has revised its guidance on fish consumption

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

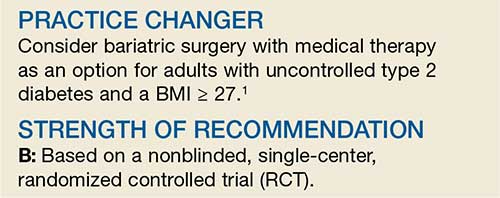

Bariatric Surgery + Medical Therapy: Effective Tx for T2DM?

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

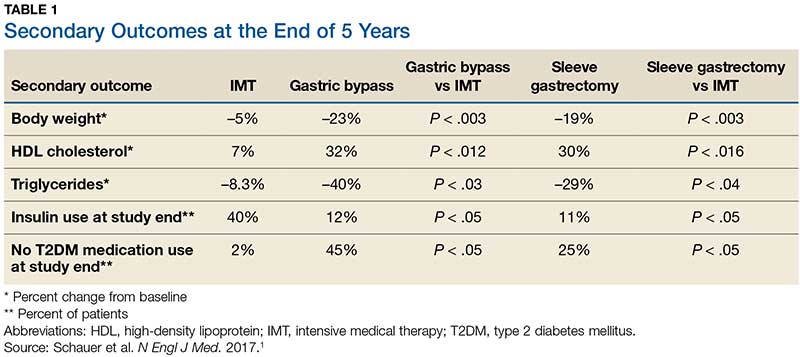

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

Intervention tied to fewer depressive symptoms, more weight loss

Adults with obesity and depression who participated in a program that addressed weight and mood saw improvement in weight loss and depressive symptoms at 12 months, results of a randomized, controlled trial of almost 350 patients show.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first and largest RTC of integrated collaborative care for coexisting obesity and depression,” wrote Jun Ma, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and colleagues.

Dr. Ma and colleagues enrolled 409 patients in the RAINBOW (Research Aimed at Improving Both Mood and Weight) trial between September 2014 and January 2017 from family and internal medicine departments at four medical centers in California. The RAINBOW intervention combined usual care with a weight loss treatment program used in diabetes prevention, problem-solving therapy, and prescriptions for antidepressants if indicated. About 71% of the trial participants were non-Hispanic white adults, 70% were women, and 69% had a college education.

Half the patients were randomized to receive usual care consisting of seeing personal physicians, receiving information on obesity and depression services at the clinic, and wireless activity-tracking devices. Patients were enrolled in the trial if they scored at least 10 points in the nine-item Patient Health Questionaire (PHQ-9) and had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher, or a BMI of 27 or higher in Asian adults. The mean age in the cohort was 51.0 years, the mean BMI was 37.7, and the mean PHQ-9 score was 13.8.

Of the 344 patients (84.1%) who completed follow-up at 12 months, there was a decrease in mean BMI from 36.7 to 35.9 for patients who received the collaborative care intervention, compared with no change in BMI for patients who received usual care alone (between-group mean difference, −0.7; 95% confidence interval, −1.1 to −0.2; P = .01). Depressive symptoms also improved in the intervention group, with mean 20-item Depression Symptom Checklist scores decreasing from 1.5 at baseline to 1.1 at 12 months, compared with a decrease from 1.5 at baseline to 1.4 at 12 months in the usual-care group (between-group mean difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0; P = .01). Overall, there were 47 adverse events or serious adverse events, with 27 events in the collaborative-care intervention group and 20 events in the usual-care group involving musculoskeletal injuries such as fracture and meniscus tear.

In addition, they cited the relative demographic homogeneity of the study sample as one of several limitations.

The study was funded in part by Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One author, Philip W. Lavori, PhD, reported receiving personal fees from Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ma J et al. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama2019.0557.

Adults with obesity and depression who participated in a program that addressed weight and mood saw improvement in weight loss and depressive symptoms at 12 months, results of a randomized, controlled trial of almost 350 patients show.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first and largest RTC of integrated collaborative care for coexisting obesity and depression,” wrote Jun Ma, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and colleagues.

Dr. Ma and colleagues enrolled 409 patients in the RAINBOW (Research Aimed at Improving Both Mood and Weight) trial between September 2014 and January 2017 from family and internal medicine departments at four medical centers in California. The RAINBOW intervention combined usual care with a weight loss treatment program used in diabetes prevention, problem-solving therapy, and prescriptions for antidepressants if indicated. About 71% of the trial participants were non-Hispanic white adults, 70% were women, and 69% had a college education.

Half the patients were randomized to receive usual care consisting of seeing personal physicians, receiving information on obesity and depression services at the clinic, and wireless activity-tracking devices. Patients were enrolled in the trial if they scored at least 10 points in the nine-item Patient Health Questionaire (PHQ-9) and had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher, or a BMI of 27 or higher in Asian adults. The mean age in the cohort was 51.0 years, the mean BMI was 37.7, and the mean PHQ-9 score was 13.8.

Of the 344 patients (84.1%) who completed follow-up at 12 months, there was a decrease in mean BMI from 36.7 to 35.9 for patients who received the collaborative care intervention, compared with no change in BMI for patients who received usual care alone (between-group mean difference, −0.7; 95% confidence interval, −1.1 to −0.2; P = .01). Depressive symptoms also improved in the intervention group, with mean 20-item Depression Symptom Checklist scores decreasing from 1.5 at baseline to 1.1 at 12 months, compared with a decrease from 1.5 at baseline to 1.4 at 12 months in the usual-care group (between-group mean difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0; P = .01). Overall, there were 47 adverse events or serious adverse events, with 27 events in the collaborative-care intervention group and 20 events in the usual-care group involving musculoskeletal injuries such as fracture and meniscus tear.

In addition, they cited the relative demographic homogeneity of the study sample as one of several limitations.

The study was funded in part by Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One author, Philip W. Lavori, PhD, reported receiving personal fees from Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ma J et al. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama2019.0557.

Adults with obesity and depression who participated in a program that addressed weight and mood saw improvement in weight loss and depressive symptoms at 12 months, results of a randomized, controlled trial of almost 350 patients show.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first and largest RTC of integrated collaborative care for coexisting obesity and depression,” wrote Jun Ma, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and colleagues.

Dr. Ma and colleagues enrolled 409 patients in the RAINBOW (Research Aimed at Improving Both Mood and Weight) trial between September 2014 and January 2017 from family and internal medicine departments at four medical centers in California. The RAINBOW intervention combined usual care with a weight loss treatment program used in diabetes prevention, problem-solving therapy, and prescriptions for antidepressants if indicated. About 71% of the trial participants were non-Hispanic white adults, 70% were women, and 69% had a college education.

Half the patients were randomized to receive usual care consisting of seeing personal physicians, receiving information on obesity and depression services at the clinic, and wireless activity-tracking devices. Patients were enrolled in the trial if they scored at least 10 points in the nine-item Patient Health Questionaire (PHQ-9) and had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher, or a BMI of 27 or higher in Asian adults. The mean age in the cohort was 51.0 years, the mean BMI was 37.7, and the mean PHQ-9 score was 13.8.

Of the 344 patients (84.1%) who completed follow-up at 12 months, there was a decrease in mean BMI from 36.7 to 35.9 for patients who received the collaborative care intervention, compared with no change in BMI for patients who received usual care alone (between-group mean difference, −0.7; 95% confidence interval, −1.1 to −0.2; P = .01). Depressive symptoms also improved in the intervention group, with mean 20-item Depression Symptom Checklist scores decreasing from 1.5 at baseline to 1.1 at 12 months, compared with a decrease from 1.5 at baseline to 1.4 at 12 months in the usual-care group (between-group mean difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0; P = .01). Overall, there were 47 adverse events or serious adverse events, with 27 events in the collaborative-care intervention group and 20 events in the usual-care group involving musculoskeletal injuries such as fracture and meniscus tear.

In addition, they cited the relative demographic homogeneity of the study sample as one of several limitations.

The study was funded in part by Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One author, Philip W. Lavori, PhD, reported receiving personal fees from Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ma J et al. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama2019.0557.

FROM JAMA

New findings cast more doubt on ‘fat-but-fit’ theory

SAN FRANCISCO – Can you be “fat but fit” if you’re obese but don’t suffer from metabolic syndrome? Some advocates have claimed you can, but new findings presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association provide more evidence that those extra pounds translate to extra cardiac risk.

Fat-but-fit is a misnomer, Yvonne Commodore-Mensah, PhD, RN, assistant professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Baltimore, said in an interview. “The metabolically healthy obese are not so healthy. [We found] they had a higher risk of heart disease than people who were metabolically healthy and nonobese.”

Studies began supporting the fat-but-fit “paradox” in the late 1990s. They showed “that all-cause and CVD [cardiovascular] mortality risk in obese individuals, as defined by body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage, or waist circumference, who are fit (i.e., cardiorespiratory fitness level above the age-specific and sex-specific 20th percentile) is not significantly different from their normal-weight and fit counterparts” (Br J Sports Med. 2018;52[3]:151-3).