User login

Diabetic dyslipidemia with eruptive xanthoma

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

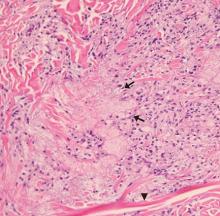

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

Weight loss surgery linked to lower CV event risk in diabetes

, compared with nonsurgical management, according to data presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The retrospective cohort study, simultaneously published in JAMA, looked at outcomes in 13,722 individuals with type 2 diabetes and obesity, 2,287 of whom underwent metabolic surgery and the rest of the matched cohort receiving usual care.

At 8 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint – a composite of first occurrence of all-cause mortality, coronary artery events, cerebrovascular events, heart failure, nephropathy, and atrial fibrillation – was 30.8% in the weight loss–surgery group and 47.7% in the nonsurgical-control group, representing a 39% lower risk with weight loss surgery (P less than .001).

The analysis failed to find any interaction with sex, age, body mass index (BMI), HbA1c level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, or use of insulin, sulfonylureas, or lipid-lowering medications.

Metabolic surgery was also associated with a significantly lower cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke and mortality than usual care (17% vs. 27.6%).

In particular, researchers saw a significant 41% reduction in the risk of death at eight years in the surgical group compared to usual care (10% vs. 17.8%), a 62% reduction in the risk of heart failure, a 31% reduction in the risk of coronary artery disease, and a 60% reduction in nephropathy risk. Metabolic surgery was also associated with a 33% reduction in cerebrovascular disease risk, and a 22% lower risk of atrial fibrillation.

In the group that underwent metabolic surgery, mean bodyweight at 8 years was reduced by 29.1 kg, compared with 8.7 kg in the control group. At baseline, 75% of the metabolic surgery group had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or above, 20% had a BMI between 35-39.9, and 5% had a BMI between 30-34.9.

The surgery was also associated with significantly greater reductions in HbA1c, and in the use of noninsulin diabetes medications, insulin, antihypertensive medications, lipid-lowering therapies, and aspirin.

The most common surgical weight loss procedure was Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (63%), followed by sleeve gastrectomy (32%), and adjustable gastric banding (5%). Five patients underwent duodenal switch.

In the 90 days after surgery, 3% of patients experienced bleeding that required transfusion, 2.5% experienced pulmonary adverse events, 1% experienced venous thromboembolism, 0.7% experienced cardiac events, and 0.2% experienced renal failure that required dialysis. There were also 15 deaths (0.7%) in the surgical group, and 4.8% of patients required abdominal surgical intervention.

“We speculate that the lower rate of [major adverse cardiovascular events] after metabolic surgery observed in this study may be related to substantial and sustained weight loss with subsequent improvement in metabolic, structural, hemodynamic, and neurohormonal abnormalities,” wrote Ali Aminian, MD, of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthors.

“Although large and sustained surgically induced weight loss has profound physiologic effects, a growing body of evidence indicates that some of the beneficial metabolic and neurohormonal changes that occur after metabolic surgical procedures are related to anatomical changes in the gastrointestinal tract that are partially independent of weight loss,” they wrote.

The authors, however, were also keen to point out that their study was observational, and should therefore be considered “hypothesis generating.” While the two study groups were matched on 37 baseline covariates, those in the surgical group did have a higher body weight, higher BMI, higher rates of dyslipidemia, and higher rates of hypertension.

“The findings from this observational study must be confirmed in randomized clinical trials,” they noted.

The study was partly funded by Medtronic, and one author was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Five authors declared funding and support from private industry, including from Medtronic, and one author declared institutional grants.

SOURCE: Aminian A et al. JAMA 2019, Sept 2. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.14231.

Despite a focus on reducing macrovascular events in individuals with type 2 diabetes, none of the major randomized controlled trials of glucose-lowering interventions that support current treatment guidelines have achieved this outcome. This study of bariatric surgery in obese patients with diabetes, however, does show reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events, although these outcomes should be interpreted with caution because of their observational nature and imprecise matching of the study groups.

Despite this, the many known benefits associated with bariatric surgery–induced weight loss suggest that for carefully selected, motivated patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes – who have been unable to lose weight by other means – this could be the preferred treatment option.

Dr. Edward H. Livingston is the deputy editor of JAMA and with the department of surgery at the University of California, Los Angeles. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2019, Sept 2. DOI:10.1001/jama.2019.14577). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Despite a focus on reducing macrovascular events in individuals with type 2 diabetes, none of the major randomized controlled trials of glucose-lowering interventions that support current treatment guidelines have achieved this outcome. This study of bariatric surgery in obese patients with diabetes, however, does show reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events, although these outcomes should be interpreted with caution because of their observational nature and imprecise matching of the study groups.

Despite this, the many known benefits associated with bariatric surgery–induced weight loss suggest that for carefully selected, motivated patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes – who have been unable to lose weight by other means – this could be the preferred treatment option.

Dr. Edward H. Livingston is the deputy editor of JAMA and with the department of surgery at the University of California, Los Angeles. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2019, Sept 2. DOI:10.1001/jama.2019.14577). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Despite a focus on reducing macrovascular events in individuals with type 2 diabetes, none of the major randomized controlled trials of glucose-lowering interventions that support current treatment guidelines have achieved this outcome. This study of bariatric surgery in obese patients with diabetes, however, does show reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events, although these outcomes should be interpreted with caution because of their observational nature and imprecise matching of the study groups.

Despite this, the many known benefits associated with bariatric surgery–induced weight loss suggest that for carefully selected, motivated patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes – who have been unable to lose weight by other means – this could be the preferred treatment option.

Dr. Edward H. Livingston is the deputy editor of JAMA and with the department of surgery at the University of California, Los Angeles. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2019, Sept 2. DOI:10.1001/jama.2019.14577). No conflicts of interest were declared.

, compared with nonsurgical management, according to data presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The retrospective cohort study, simultaneously published in JAMA, looked at outcomes in 13,722 individuals with type 2 diabetes and obesity, 2,287 of whom underwent metabolic surgery and the rest of the matched cohort receiving usual care.

At 8 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint – a composite of first occurrence of all-cause mortality, coronary artery events, cerebrovascular events, heart failure, nephropathy, and atrial fibrillation – was 30.8% in the weight loss–surgery group and 47.7% in the nonsurgical-control group, representing a 39% lower risk with weight loss surgery (P less than .001).

The analysis failed to find any interaction with sex, age, body mass index (BMI), HbA1c level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, or use of insulin, sulfonylureas, or lipid-lowering medications.

Metabolic surgery was also associated with a significantly lower cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke and mortality than usual care (17% vs. 27.6%).

In particular, researchers saw a significant 41% reduction in the risk of death at eight years in the surgical group compared to usual care (10% vs. 17.8%), a 62% reduction in the risk of heart failure, a 31% reduction in the risk of coronary artery disease, and a 60% reduction in nephropathy risk. Metabolic surgery was also associated with a 33% reduction in cerebrovascular disease risk, and a 22% lower risk of atrial fibrillation.

In the group that underwent metabolic surgery, mean bodyweight at 8 years was reduced by 29.1 kg, compared with 8.7 kg in the control group. At baseline, 75% of the metabolic surgery group had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or above, 20% had a BMI between 35-39.9, and 5% had a BMI between 30-34.9.

The surgery was also associated with significantly greater reductions in HbA1c, and in the use of noninsulin diabetes medications, insulin, antihypertensive medications, lipid-lowering therapies, and aspirin.

The most common surgical weight loss procedure was Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (63%), followed by sleeve gastrectomy (32%), and adjustable gastric banding (5%). Five patients underwent duodenal switch.

In the 90 days after surgery, 3% of patients experienced bleeding that required transfusion, 2.5% experienced pulmonary adverse events, 1% experienced venous thromboembolism, 0.7% experienced cardiac events, and 0.2% experienced renal failure that required dialysis. There were also 15 deaths (0.7%) in the surgical group, and 4.8% of patients required abdominal surgical intervention.

“We speculate that the lower rate of [major adverse cardiovascular events] after metabolic surgery observed in this study may be related to substantial and sustained weight loss with subsequent improvement in metabolic, structural, hemodynamic, and neurohormonal abnormalities,” wrote Ali Aminian, MD, of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthors.

“Although large and sustained surgically induced weight loss has profound physiologic effects, a growing body of evidence indicates that some of the beneficial metabolic and neurohormonal changes that occur after metabolic surgical procedures are related to anatomical changes in the gastrointestinal tract that are partially independent of weight loss,” they wrote.

The authors, however, were also keen to point out that their study was observational, and should therefore be considered “hypothesis generating.” While the two study groups were matched on 37 baseline covariates, those in the surgical group did have a higher body weight, higher BMI, higher rates of dyslipidemia, and higher rates of hypertension.

“The findings from this observational study must be confirmed in randomized clinical trials,” they noted.

The study was partly funded by Medtronic, and one author was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Five authors declared funding and support from private industry, including from Medtronic, and one author declared institutional grants.

SOURCE: Aminian A et al. JAMA 2019, Sept 2. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.14231.

, compared with nonsurgical management, according to data presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The retrospective cohort study, simultaneously published in JAMA, looked at outcomes in 13,722 individuals with type 2 diabetes and obesity, 2,287 of whom underwent metabolic surgery and the rest of the matched cohort receiving usual care.

At 8 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint – a composite of first occurrence of all-cause mortality, coronary artery events, cerebrovascular events, heart failure, nephropathy, and atrial fibrillation – was 30.8% in the weight loss–surgery group and 47.7% in the nonsurgical-control group, representing a 39% lower risk with weight loss surgery (P less than .001).

The analysis failed to find any interaction with sex, age, body mass index (BMI), HbA1c level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, or use of insulin, sulfonylureas, or lipid-lowering medications.

Metabolic surgery was also associated with a significantly lower cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke and mortality than usual care (17% vs. 27.6%).

In particular, researchers saw a significant 41% reduction in the risk of death at eight years in the surgical group compared to usual care (10% vs. 17.8%), a 62% reduction in the risk of heart failure, a 31% reduction in the risk of coronary artery disease, and a 60% reduction in nephropathy risk. Metabolic surgery was also associated with a 33% reduction in cerebrovascular disease risk, and a 22% lower risk of atrial fibrillation.

In the group that underwent metabolic surgery, mean bodyweight at 8 years was reduced by 29.1 kg, compared with 8.7 kg in the control group. At baseline, 75% of the metabolic surgery group had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or above, 20% had a BMI between 35-39.9, and 5% had a BMI between 30-34.9.

The surgery was also associated with significantly greater reductions in HbA1c, and in the use of noninsulin diabetes medications, insulin, antihypertensive medications, lipid-lowering therapies, and aspirin.

The most common surgical weight loss procedure was Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (63%), followed by sleeve gastrectomy (32%), and adjustable gastric banding (5%). Five patients underwent duodenal switch.

In the 90 days after surgery, 3% of patients experienced bleeding that required transfusion, 2.5% experienced pulmonary adverse events, 1% experienced venous thromboembolism, 0.7% experienced cardiac events, and 0.2% experienced renal failure that required dialysis. There were also 15 deaths (0.7%) in the surgical group, and 4.8% of patients required abdominal surgical intervention.

“We speculate that the lower rate of [major adverse cardiovascular events] after metabolic surgery observed in this study may be related to substantial and sustained weight loss with subsequent improvement in metabolic, structural, hemodynamic, and neurohormonal abnormalities,” wrote Ali Aminian, MD, of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthors.

“Although large and sustained surgically induced weight loss has profound physiologic effects, a growing body of evidence indicates that some of the beneficial metabolic and neurohormonal changes that occur after metabolic surgical procedures are related to anatomical changes in the gastrointestinal tract that are partially independent of weight loss,” they wrote.

The authors, however, were also keen to point out that their study was observational, and should therefore be considered “hypothesis generating.” While the two study groups were matched on 37 baseline covariates, those in the surgical group did have a higher body weight, higher BMI, higher rates of dyslipidemia, and higher rates of hypertension.

“The findings from this observational study must be confirmed in randomized clinical trials,” they noted.

The study was partly funded by Medtronic, and one author was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Five authors declared funding and support from private industry, including from Medtronic, and one author declared institutional grants.

SOURCE: Aminian A et al. JAMA 2019, Sept 2. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.14231.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Key clinical point: Bariatric surgery may reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: Bariatric surgery is associated with a 39% reduction in risk of major cardiovascular events.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study in 13,722 individuals with type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Disclosures: The study was partly funded by Medtronic, and one author was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Five authors declared funding and support from private industry, including from Medtronic, and one author declared institutional grants.

Source: Aminian A et al. JAMA 2019, September 2. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.14231.

Mediterranean diet tied to improved cognition in type 2 diabetes

People with type 2 diabetes whose diet followed a “Mediterranean” pattern – high in vegetables, legumes, fish, and unsaturated fats – saw global cognitive improvements over a 2-year period, compared with individuals with different eating patterns, even if the latter incorporated healthy dietary features. In addition, effective glycemic control seemed to have a role in sustaining the benefits associated with the Mediterranean-type diet.

Adults without type 2 diabetes, meanwhile, did not see the cognitive improvements associated with a Mediterranean diet, suggesting that the pathways linking diet to cognition may be different for individuals with and without diabetes, according to Josiemer Mattei, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The investigators used data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort of about 1,499 adults aged 45-75 years who lived in Boston and identified as Puerto Rican, for their research, which was published in Diabetes Care.

At baseline, participants were administered a questionnaire to capture their eating patterns. Four diet-quality scores – Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) were analyzed. The participants were also screened for diabetes, and nearly 40% of them were found to have type 2 diabetes at baseline (74% uncontrolled). They underwent a battery of cognitive tests, including the Mini-Mental State Exam and tests for verbal fluency, executive function, word recognition, and figure copying. The study endpoints included 2-year change in global cognitive function as well as executive and memory function. At 2 years, data was available for 913 participants.

Among participants with type 2 diabetes, greater adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet was significantly associated with a higher positive change at the 2-year follow-up in global cognitive function score (0.027 [SD, 0.011]; P = .016), the Mini-Mental State Exam, and other individual tests. The association was significant for those who were under glycemic control at baseline and who remained stable or improved over 2 years, but not for those with poor or worsening glycemic control.

“The Mediterranean diet explained as much or more of the variability in predicting changes in cognitive function in our study as did age, especially for participants with type 2 diabetes under glycemic control. ... This dietary pattern may provide more cognitive benefits [in this patient group] than other modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote in their analysis. They stressed that a Mediterranean dietary pattern can be realized through foods and dishes that are already standard in many Puerto Rican households.

In participants who did not have diabetes, improvement in memory function measures was seen in association with a Mediterranean diet, but also with adherence to other eating patterns that are deemed healthy. That suggests that for this subgroup, any evidence-based healthy diet – not just the Mediterranean diet – may have some benefits for memory function.

“Dietary recommendations for cognitive health may need to be tailored for individuals with versus without type 2 diabetes,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mattei and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its observational design.

The study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Aging; and Harvard University. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mattei et al. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1372-9.

People with type 2 diabetes whose diet followed a “Mediterranean” pattern – high in vegetables, legumes, fish, and unsaturated fats – saw global cognitive improvements over a 2-year period, compared with individuals with different eating patterns, even if the latter incorporated healthy dietary features. In addition, effective glycemic control seemed to have a role in sustaining the benefits associated with the Mediterranean-type diet.

Adults without type 2 diabetes, meanwhile, did not see the cognitive improvements associated with a Mediterranean diet, suggesting that the pathways linking diet to cognition may be different for individuals with and without diabetes, according to Josiemer Mattei, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The investigators used data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort of about 1,499 adults aged 45-75 years who lived in Boston and identified as Puerto Rican, for their research, which was published in Diabetes Care.

At baseline, participants were administered a questionnaire to capture their eating patterns. Four diet-quality scores – Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) were analyzed. The participants were also screened for diabetes, and nearly 40% of them were found to have type 2 diabetes at baseline (74% uncontrolled). They underwent a battery of cognitive tests, including the Mini-Mental State Exam and tests for verbal fluency, executive function, word recognition, and figure copying. The study endpoints included 2-year change in global cognitive function as well as executive and memory function. At 2 years, data was available for 913 participants.

Among participants with type 2 diabetes, greater adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet was significantly associated with a higher positive change at the 2-year follow-up in global cognitive function score (0.027 [SD, 0.011]; P = .016), the Mini-Mental State Exam, and other individual tests. The association was significant for those who were under glycemic control at baseline and who remained stable or improved over 2 years, but not for those with poor or worsening glycemic control.

“The Mediterranean diet explained as much or more of the variability in predicting changes in cognitive function in our study as did age, especially for participants with type 2 diabetes under glycemic control. ... This dietary pattern may provide more cognitive benefits [in this patient group] than other modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote in their analysis. They stressed that a Mediterranean dietary pattern can be realized through foods and dishes that are already standard in many Puerto Rican households.

In participants who did not have diabetes, improvement in memory function measures was seen in association with a Mediterranean diet, but also with adherence to other eating patterns that are deemed healthy. That suggests that for this subgroup, any evidence-based healthy diet – not just the Mediterranean diet – may have some benefits for memory function.

“Dietary recommendations for cognitive health may need to be tailored for individuals with versus without type 2 diabetes,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mattei and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its observational design.

The study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Aging; and Harvard University. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mattei et al. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1372-9.

People with type 2 diabetes whose diet followed a “Mediterranean” pattern – high in vegetables, legumes, fish, and unsaturated fats – saw global cognitive improvements over a 2-year period, compared with individuals with different eating patterns, even if the latter incorporated healthy dietary features. In addition, effective glycemic control seemed to have a role in sustaining the benefits associated with the Mediterranean-type diet.

Adults without type 2 diabetes, meanwhile, did not see the cognitive improvements associated with a Mediterranean diet, suggesting that the pathways linking diet to cognition may be different for individuals with and without diabetes, according to Josiemer Mattei, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The investigators used data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort of about 1,499 adults aged 45-75 years who lived in Boston and identified as Puerto Rican, for their research, which was published in Diabetes Care.

At baseline, participants were administered a questionnaire to capture their eating patterns. Four diet-quality scores – Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) were analyzed. The participants were also screened for diabetes, and nearly 40% of them were found to have type 2 diabetes at baseline (74% uncontrolled). They underwent a battery of cognitive tests, including the Mini-Mental State Exam and tests for verbal fluency, executive function, word recognition, and figure copying. The study endpoints included 2-year change in global cognitive function as well as executive and memory function. At 2 years, data was available for 913 participants.

Among participants with type 2 diabetes, greater adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet was significantly associated with a higher positive change at the 2-year follow-up in global cognitive function score (0.027 [SD, 0.011]; P = .016), the Mini-Mental State Exam, and other individual tests. The association was significant for those who were under glycemic control at baseline and who remained stable or improved over 2 years, but not for those with poor or worsening glycemic control.

“The Mediterranean diet explained as much or more of the variability in predicting changes in cognitive function in our study as did age, especially for participants with type 2 diabetes under glycemic control. ... This dietary pattern may provide more cognitive benefits [in this patient group] than other modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote in their analysis. They stressed that a Mediterranean dietary pattern can be realized through foods and dishes that are already standard in many Puerto Rican households.

In participants who did not have diabetes, improvement in memory function measures was seen in association with a Mediterranean diet, but also with adherence to other eating patterns that are deemed healthy. That suggests that for this subgroup, any evidence-based healthy diet – not just the Mediterranean diet – may have some benefits for memory function.

“Dietary recommendations for cognitive health may need to be tailored for individuals with versus without type 2 diabetes,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mattei and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its observational design.

The study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Aging; and Harvard University. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mattei et al. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1372-9.

FROM DIABETES CARE

NAFLD unchecked is a ‘harbinger of deadly dysmetabolism’

SAN DIEGO – When it comes to metabolic and endocrine health, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the furthest thing from a nonissue – it’s “a harbinger of deadly dysmetabolism,” said Christine Kessler, MN, ANP-BC, CNS, BC-ADM, FAANP, a nurse practitioner and founder of Metabolic Medicine Associates, King George, Va.

“I chase it, I follow it, I worry about it. Never look at it again as a benign thing,” Ms. Kessler said in a presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education. “It’s the most common chronic liver disease in the United States – move over, hep C ... and it’ll be the number one cause of liver transplant within 20 years.”

But the news isn’t all grim: NAFLD can be reversible, because the liver is one organ that can “take a licking and keep on ticking,” she said.

An estimated 30%-40% of adults in the United States have NAFLD, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The most severe form of the disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), causes liver cell damage and affects an estimated 3%-12% of adults.

Why worry about NAFLD? Because it can boost cardiovascular risk (especially in conjunction with metabolic syndrome) and the risk for liver cancer, said Ms. Kessler.

Among the risk factors for NAFLD are obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome, and many others, including medications such as methotrexate, corticosteroids, and tetracyclines. Men, and Latino and Asian individuals are especially vulnerable, whereas black individuals may have protection against it.

Researchers are exploring the possibility that NAFLD is a “multihit” condition that is linked to multiple causes, possibly including overgrowth of bacteria in the gut, Ms. Kessler noted. It is not clear, however, whether regulation of gut microbiota would be helpful in preventing the condition.

Ms. Kessler urged her colleagues to consider workups in the following situations: when an incidental finding is noticed during imaging, when liver enzymes are abnormal (although they can misleadingly appear normal), and when there are overt symptoms of liver diseases. Causes such as alcohol use, medications, and hepatitis must first be ruled out, she said, and patients should be referred to a gastroenterologist if NAFLD is confirmed.

In regard to treatment, weight and diet control are crucial because they can have a significant impact in a patient with NAFLD. “You don’t come down with NAFLD, and then NASH, and then cirrhosis,” she explained. “It goes back and forth. You can go from normal liver to fatty liver, and back to normal. We’ve all seen it.”

Reduce weight, blood pressure, and blood sugar, she said, “and you’ll see NASH go to fatty liver, and fatty liver go over to normal. If you can have someone lose between 9% and 10% of their weight, you can turn around NASH. This is huge.”

As for medications, she said, “there is no one drug for fatty liver disease.” No medication has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of NAFLD or NASH, but there are several treatments that seem to be helpful, she said.

They include statins, though not for patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and some of the diabetes drugs – pioglitazone (Actos; to treat steatohepatitis in patients with or without type 2 diabetes who have biopsy-proven NASH); metformin (only in patients with diabetes); and the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

Also included among the therapies are vitamin E 800 IU/day and omega-3 fatty acids for patients who have a high levels of triglycerides, as well as lower-dose vitamin E (600 IU/day) and vitamin C (500 mg/day), which are best when used with lifestyle changes; increased choline intake – which supports liver health in menopausal women – from foods such as eggs; and milk thistle, which helps decrease liver inflammation.

Patients without chronic liver disease may find another helpful preventive tool on the shelves of their local liquor store: red wine, but with moderation, Ms. Kessler cautioned.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Kessler disclosed relationships as an adviser and speaker with Novo Nordisk, and with Clarion Brands.

SAN DIEGO – When it comes to metabolic and endocrine health, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the furthest thing from a nonissue – it’s “a harbinger of deadly dysmetabolism,” said Christine Kessler, MN, ANP-BC, CNS, BC-ADM, FAANP, a nurse practitioner and founder of Metabolic Medicine Associates, King George, Va.

“I chase it, I follow it, I worry about it. Never look at it again as a benign thing,” Ms. Kessler said in a presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education. “It’s the most common chronic liver disease in the United States – move over, hep C ... and it’ll be the number one cause of liver transplant within 20 years.”

But the news isn’t all grim: NAFLD can be reversible, because the liver is one organ that can “take a licking and keep on ticking,” she said.

An estimated 30%-40% of adults in the United States have NAFLD, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The most severe form of the disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), causes liver cell damage and affects an estimated 3%-12% of adults.

Why worry about NAFLD? Because it can boost cardiovascular risk (especially in conjunction with metabolic syndrome) and the risk for liver cancer, said Ms. Kessler.

Among the risk factors for NAFLD are obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome, and many others, including medications such as methotrexate, corticosteroids, and tetracyclines. Men, and Latino and Asian individuals are especially vulnerable, whereas black individuals may have protection against it.

Researchers are exploring the possibility that NAFLD is a “multihit” condition that is linked to multiple causes, possibly including overgrowth of bacteria in the gut, Ms. Kessler noted. It is not clear, however, whether regulation of gut microbiota would be helpful in preventing the condition.

Ms. Kessler urged her colleagues to consider workups in the following situations: when an incidental finding is noticed during imaging, when liver enzymes are abnormal (although they can misleadingly appear normal), and when there are overt symptoms of liver diseases. Causes such as alcohol use, medications, and hepatitis must first be ruled out, she said, and patients should be referred to a gastroenterologist if NAFLD is confirmed.

In regard to treatment, weight and diet control are crucial because they can have a significant impact in a patient with NAFLD. “You don’t come down with NAFLD, and then NASH, and then cirrhosis,” she explained. “It goes back and forth. You can go from normal liver to fatty liver, and back to normal. We’ve all seen it.”

Reduce weight, blood pressure, and blood sugar, she said, “and you’ll see NASH go to fatty liver, and fatty liver go over to normal. If you can have someone lose between 9% and 10% of their weight, you can turn around NASH. This is huge.”

As for medications, she said, “there is no one drug for fatty liver disease.” No medication has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of NAFLD or NASH, but there are several treatments that seem to be helpful, she said.

They include statins, though not for patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and some of the diabetes drugs – pioglitazone (Actos; to treat steatohepatitis in patients with or without type 2 diabetes who have biopsy-proven NASH); metformin (only in patients with diabetes); and the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

Also included among the therapies are vitamin E 800 IU/day and omega-3 fatty acids for patients who have a high levels of triglycerides, as well as lower-dose vitamin E (600 IU/day) and vitamin C (500 mg/day), which are best when used with lifestyle changes; increased choline intake – which supports liver health in menopausal women – from foods such as eggs; and milk thistle, which helps decrease liver inflammation.

Patients without chronic liver disease may find another helpful preventive tool on the shelves of their local liquor store: red wine, but with moderation, Ms. Kessler cautioned.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Kessler disclosed relationships as an adviser and speaker with Novo Nordisk, and with Clarion Brands.

SAN DIEGO – When it comes to metabolic and endocrine health, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the furthest thing from a nonissue – it’s “a harbinger of deadly dysmetabolism,” said Christine Kessler, MN, ANP-BC, CNS, BC-ADM, FAANP, a nurse practitioner and founder of Metabolic Medicine Associates, King George, Va.

“I chase it, I follow it, I worry about it. Never look at it again as a benign thing,” Ms. Kessler said in a presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education. “It’s the most common chronic liver disease in the United States – move over, hep C ... and it’ll be the number one cause of liver transplant within 20 years.”

But the news isn’t all grim: NAFLD can be reversible, because the liver is one organ that can “take a licking and keep on ticking,” she said.

An estimated 30%-40% of adults in the United States have NAFLD, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The most severe form of the disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), causes liver cell damage and affects an estimated 3%-12% of adults.

Why worry about NAFLD? Because it can boost cardiovascular risk (especially in conjunction with metabolic syndrome) and the risk for liver cancer, said Ms. Kessler.

Among the risk factors for NAFLD are obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome, and many others, including medications such as methotrexate, corticosteroids, and tetracyclines. Men, and Latino and Asian individuals are especially vulnerable, whereas black individuals may have protection against it.

Researchers are exploring the possibility that NAFLD is a “multihit” condition that is linked to multiple causes, possibly including overgrowth of bacteria in the gut, Ms. Kessler noted. It is not clear, however, whether regulation of gut microbiota would be helpful in preventing the condition.

Ms. Kessler urged her colleagues to consider workups in the following situations: when an incidental finding is noticed during imaging, when liver enzymes are abnormal (although they can misleadingly appear normal), and when there are overt symptoms of liver diseases. Causes such as alcohol use, medications, and hepatitis must first be ruled out, she said, and patients should be referred to a gastroenterologist if NAFLD is confirmed.

In regard to treatment, weight and diet control are crucial because they can have a significant impact in a patient with NAFLD. “You don’t come down with NAFLD, and then NASH, and then cirrhosis,” she explained. “It goes back and forth. You can go from normal liver to fatty liver, and back to normal. We’ve all seen it.”

Reduce weight, blood pressure, and blood sugar, she said, “and you’ll see NASH go to fatty liver, and fatty liver go over to normal. If you can have someone lose between 9% and 10% of their weight, you can turn around NASH. This is huge.”

As for medications, she said, “there is no one drug for fatty liver disease.” No medication has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of NAFLD or NASH, but there are several treatments that seem to be helpful, she said.

They include statins, though not for patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and some of the diabetes drugs – pioglitazone (Actos; to treat steatohepatitis in patients with or without type 2 diabetes who have biopsy-proven NASH); metformin (only in patients with diabetes); and the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

Also included among the therapies are vitamin E 800 IU/day and omega-3 fatty acids for patients who have a high levels of triglycerides, as well as lower-dose vitamin E (600 IU/day) and vitamin C (500 mg/day), which are best when used with lifestyle changes; increased choline intake – which supports liver health in menopausal women – from foods such as eggs; and milk thistle, which helps decrease liver inflammation.

Patients without chronic liver disease may find another helpful preventive tool on the shelves of their local liquor store: red wine, but with moderation, Ms. Kessler cautioned.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Kessler disclosed relationships as an adviser and speaker with Novo Nordisk, and with Clarion Brands.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MEDS 2019

Beyond C. difficile: The future of fecal microbial transplantation

SAN DIEGO – Two leading figures in microbiome research took time during the annual Digestive Disease Week to share their perspective with members of the press. Identifying key research presented at the meeting and painting a broader picture of trends and challenges in research on the interplay with the microbiota with gut health, Colleen Kelly, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., cochair and principal investigator, AGA FMT Registry Steering Committee, led off the round table with a discussion of human research on fecal microbial transplantation (FMT) and obesity.

Purna Kashyap, MBBS, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., member, AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education Scientific Advisory Board, delved into the potential for donor microbiota transplant to address small bowel disorders, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and provided commentary regarding the potential – and limitations – of using FMT in functional bowel disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Obesity

Dr. Kelly noted that two abstracts at the conference presented data about FMT in obesity. The first study was presented by Jessica Allegretti, MD, a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; the second study was presented by Elaine Yu, MD, an endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The two studies shared some similarities, but had some differences, said Dr. Kelly. “They both used lean donor encapsulated FMT ... and they both were placebo controlled, using placebo capsules.” The first study looked at metabolically healthy obese patients, while the second study included patients with mild to moderate insulin resistance.

Dr. Allegretti’s work looked at the effect that FMT from lean donors had on levels of a satiety peptide, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), while also looking at changes in weight and microbiota, as well as safety. Patients received an initial 30-capsule dose as well as two later doses of 12 capsules each. The 22-patient study, in which individuals were randomized 1:1 to FMT or placebo capsules, didn’t show statistically significant changes in GLP-1 levels or body mass index with FMT over the 12-week study period. “But they were able to show engraftment, which I think is an important thing that you do wonder about – over this period of time, the bacteria that came from the lean donor actually engrafted into the recipient and affected the diversity. The recipient became more similar to the donor,” said Dr. Kelly.

There were some clues among the findings that engraftment was effecting metabolic change in the recipient, she said, including differences in bile acid conversion among gut bacteria; also, lower levels of the primary bile acid taurocholic acid in recipients after FMT. “So it was a negative study in what she was looking for, but an example of these smaller studies kind of pushing the field along.”

In discussing the study presented by Dr. Yu that examined lean donor FMT in individuals with insulin resistance, Dr. Kelly said, “It was actually pretty sophisticated.” By using hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamping, the investigators were able to measure insulin sensitivity based on glucose load. In this study of 24 individuals randomized 1:1 to receive FMT or placebo capsules, recipients received weekly doses over a period of 6 weeks. Here again, though Dr. Yu and colleagues again found engraftment, “they did not find the big changes in metabolic parameters that they hoped that they would,” said Dr. Kelly.

These two studies furthered previous work completed in the Netherlands examining lean donor FMT for individuals with metabolic syndrome. “Those [studies] did show both engraftment and some changes in insulin resistance,” but they were also small studies, noted Dr. Kelly. Dr. Kashyap pointed out that the earlier studies had shown in a subgroup analysis that response to FMT was limited to those patients who lacked microbial diversity pretransplant.

This makes some mechanistic sense when thinking about FMT’s greatest success to date: Treating Clostridioides difficile infection, a condition whose very hallmark is dysbiosis characterized by monospecies gut domination, noted Dr. Kashyap.

Added Dr. Kelly, “I think everyone’s hoping there’s going to be this pill that’s going to make us skinny, but I don’t think we’re going to find that with FMT and obesity. I do think these studies are important, because there’s so much animal data already, and we’re kind of like, ‘How much more can you do in mice?’ ” By translating this preclinical work into humans, the mechanisms of obesity and the role of the microbiome can be better understood.

IBS

Turning to functional bowel disorders, Dr. Kelly pointed out a new study examining FMT for IBS. “So far, the research has been pretty disappointing,” she noted. The study, presented by Prashant Singh, MBBS, a gastroenterology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, examined FMT for patients with moderate to severe diarrhea-predominant IBS. The study had four arms, randomizing the 44 participants to FMT alone; pretreatment with metronidazole and ciprofloxacin or rifaximin, each followed by FMT; or placebo. “It really didn’t show any differences in their severity of IBS in any group; so no effect: a negative study,” said Dr. Kelly.

“It’s challenging. FMT is an appealing strategy because we don’t have to put a lot of thought process into it,” said Dr. Kashyap, but it’s no panacea. “We aren’t going to be able to treat everybody with FMT.

“The challenge with IBS is that if we look at all the compositional studies, the majority of them show that at least a big subset of patients with IBS already have a normal-appearing microbiome,” said Dr. Kashyap. In those patients, “It’s very hard to know what FMT is doing.” He noted that IBS subclassifications are made by pathophysiology, without regard to the intestinal microbiome, so these classifications may not be useful for determining who may benefit from FMT.

“Again, there’s always an opportunity to learn from these studies,” whether they’re positive or negative, as long as they’re well done, said Dr. Kashyap. “There’s always an opportunity to go back and see, was there a specific subgroup of patients who responded, where there might be one or more causes which might be more amenable” to FMT.

Small intestine

And most intestinal microbial research to date, noted Dr. Kelly, has focused on the colon. “Most of our knowledge is of fecal microbiota.” New techniques including double-balloon enteroscopy of the small bowel have promise to “provide completely new information about patterns of bacteria throughout the small bowel,” and of the role of small bowel bacteria in overall gut health, she said.

“The role of the small bowel has been ignored because of accessibility,” agreed Dr. Kashyap. There’s a current focus on research into enteroscopy and other techniques to sample small intestine microbiota, he said.

In a podium presentation, Eugene Chang, MD, Martin Boyer Professor in the University of Chicago’s department of medicine, gave a broad overview of how the small intestine microbiome modulates lipid regulation. This choice of topic for the Charles M. Mansbach Memorial Lecture shows that gastroenterologists are recognizing the importance of microbiome along the entire span of the gut, said Dr. Kashyap. Dr. Chang’s approach, he added, represents a departure in that “it’s not simply just looking at what’s present and what’s not, but seeing what’s functionally relevant to metabolism.”

“We always have known that the small intestine is the workhorse; that’s where everything happens” in terms of motility, absorption, and digestion, said Dr. Kashyap. “But because of our inability to reach it easily we’ve always chosen to ignore it; we always go after the low-hanging fruit.” Despite challenges, more microbiome research should be small-bowel focused. “Eventually, it’s no pain, no gain.”

Dr. Kashyap is on the advisory board of uBiome, and is an ad hoc advisory board member for Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kelly reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was updated on July 30, 2019.

SAN DIEGO – Two leading figures in microbiome research took time during the annual Digestive Disease Week to share their perspective with members of the press. Identifying key research presented at the meeting and painting a broader picture of trends and challenges in research on the interplay with the microbiota with gut health, Colleen Kelly, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., cochair and principal investigator, AGA FMT Registry Steering Committee, led off the round table with a discussion of human research on fecal microbial transplantation (FMT) and obesity.

Purna Kashyap, MBBS, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., member, AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education Scientific Advisory Board, delved into the potential for donor microbiota transplant to address small bowel disorders, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and provided commentary regarding the potential – and limitations – of using FMT in functional bowel disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Obesity

Dr. Kelly noted that two abstracts at the conference presented data about FMT in obesity. The first study was presented by Jessica Allegretti, MD, a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; the second study was presented by Elaine Yu, MD, an endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The two studies shared some similarities, but had some differences, said Dr. Kelly. “They both used lean donor encapsulated FMT ... and they both were placebo controlled, using placebo capsules.” The first study looked at metabolically healthy obese patients, while the second study included patients with mild to moderate insulin resistance.

Dr. Allegretti’s work looked at the effect that FMT from lean donors had on levels of a satiety peptide, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), while also looking at changes in weight and microbiota, as well as safety. Patients received an initial 30-capsule dose as well as two later doses of 12 capsules each. The 22-patient study, in which individuals were randomized 1:1 to FMT or placebo capsules, didn’t show statistically significant changes in GLP-1 levels or body mass index with FMT over the 12-week study period. “But they were able to show engraftment, which I think is an important thing that you do wonder about – over this period of time, the bacteria that came from the lean donor actually engrafted into the recipient and affected the diversity. The recipient became more similar to the donor,” said Dr. Kelly.

There were some clues among the findings that engraftment was effecting metabolic change in the recipient, she said, including differences in bile acid conversion among gut bacteria; also, lower levels of the primary bile acid taurocholic acid in recipients after FMT. “So it was a negative study in what she was looking for, but an example of these smaller studies kind of pushing the field along.”

In discussing the study presented by Dr. Yu that examined lean donor FMT in individuals with insulin resistance, Dr. Kelly said, “It was actually pretty sophisticated.” By using hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamping, the investigators were able to measure insulin sensitivity based on glucose load. In this study of 24 individuals randomized 1:1 to receive FMT or placebo capsules, recipients received weekly doses over a period of 6 weeks. Here again, though Dr. Yu and colleagues again found engraftment, “they did not find the big changes in metabolic parameters that they hoped that they would,” said Dr. Kelly.

These two studies furthered previous work completed in the Netherlands examining lean donor FMT for individuals with metabolic syndrome. “Those [studies] did show both engraftment and some changes in insulin resistance,” but they were also small studies, noted Dr. Kelly. Dr. Kashyap pointed out that the earlier studies had shown in a subgroup analysis that response to FMT was limited to those patients who lacked microbial diversity pretransplant.

This makes some mechanistic sense when thinking about FMT’s greatest success to date: Treating Clostridioides difficile infection, a condition whose very hallmark is dysbiosis characterized by monospecies gut domination, noted Dr. Kashyap.

Added Dr. Kelly, “I think everyone’s hoping there’s going to be this pill that’s going to make us skinny, but I don’t think we’re going to find that with FMT and obesity. I do think these studies are important, because there’s so much animal data already, and we’re kind of like, ‘How much more can you do in mice?’ ” By translating this preclinical work into humans, the mechanisms of obesity and the role of the microbiome can be better understood.

IBS

Turning to functional bowel disorders, Dr. Kelly pointed out a new study examining FMT for IBS. “So far, the research has been pretty disappointing,” she noted. The study, presented by Prashant Singh, MBBS, a gastroenterology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, examined FMT for patients with moderate to severe diarrhea-predominant IBS. The study had four arms, randomizing the 44 participants to FMT alone; pretreatment with metronidazole and ciprofloxacin or rifaximin, each followed by FMT; or placebo. “It really didn’t show any differences in their severity of IBS in any group; so no effect: a negative study,” said Dr. Kelly.

“It’s challenging. FMT is an appealing strategy because we don’t have to put a lot of thought process into it,” said Dr. Kashyap, but it’s no panacea. “We aren’t going to be able to treat everybody with FMT.

“The challenge with IBS is that if we look at all the compositional studies, the majority of them show that at least a big subset of patients with IBS already have a normal-appearing microbiome,” said Dr. Kashyap. In those patients, “It’s very hard to know what FMT is doing.” He noted that IBS subclassifications are made by pathophysiology, without regard to the intestinal microbiome, so these classifications may not be useful for determining who may benefit from FMT.

“Again, there’s always an opportunity to learn from these studies,” whether they’re positive or negative, as long as they’re well done, said Dr. Kashyap. “There’s always an opportunity to go back and see, was there a specific subgroup of patients who responded, where there might be one or more causes which might be more amenable” to FMT.

Small intestine

And most intestinal microbial research to date, noted Dr. Kelly, has focused on the colon. “Most of our knowledge is of fecal microbiota.” New techniques including double-balloon enteroscopy of the small bowel have promise to “provide completely new information about patterns of bacteria throughout the small bowel,” and of the role of small bowel bacteria in overall gut health, she said.

“The role of the small bowel has been ignored because of accessibility,” agreed Dr. Kashyap. There’s a current focus on research into enteroscopy and other techniques to sample small intestine microbiota, he said.

In a podium presentation, Eugene Chang, MD, Martin Boyer Professor in the University of Chicago’s department of medicine, gave a broad overview of how the small intestine microbiome modulates lipid regulation. This choice of topic for the Charles M. Mansbach Memorial Lecture shows that gastroenterologists are recognizing the importance of microbiome along the entire span of the gut, said Dr. Kashyap. Dr. Chang’s approach, he added, represents a departure in that “it’s not simply just looking at what’s present and what’s not, but seeing what’s functionally relevant to metabolism.”

“We always have known that the small intestine is the workhorse; that’s where everything happens” in terms of motility, absorption, and digestion, said Dr. Kashyap. “But because of our inability to reach it easily we’ve always chosen to ignore it; we always go after the low-hanging fruit.” Despite challenges, more microbiome research should be small-bowel focused. “Eventually, it’s no pain, no gain.”

Dr. Kashyap is on the advisory board of uBiome, and is an ad hoc advisory board member for Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kelly reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was updated on July 30, 2019.

SAN DIEGO – Two leading figures in microbiome research took time during the annual Digestive Disease Week to share their perspective with members of the press. Identifying key research presented at the meeting and painting a broader picture of trends and challenges in research on the interplay with the microbiota with gut health, Colleen Kelly, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., cochair and principal investigator, AGA FMT Registry Steering Committee, led off the round table with a discussion of human research on fecal microbial transplantation (FMT) and obesity.

Purna Kashyap, MBBS, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., member, AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education Scientific Advisory Board, delved into the potential for donor microbiota transplant to address small bowel disorders, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and provided commentary regarding the potential – and limitations – of using FMT in functional bowel disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Obesity

Dr. Kelly noted that two abstracts at the conference presented data about FMT in obesity. The first study was presented by Jessica Allegretti, MD, a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; the second study was presented by Elaine Yu, MD, an endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The two studies shared some similarities, but had some differences, said Dr. Kelly. “They both used lean donor encapsulated FMT ... and they both were placebo controlled, using placebo capsules.” The first study looked at metabolically healthy obese patients, while the second study included patients with mild to moderate insulin resistance.

Dr. Allegretti’s work looked at the effect that FMT from lean donors had on levels of a satiety peptide, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), while also looking at changes in weight and microbiota, as well as safety. Patients received an initial 30-capsule dose as well as two later doses of 12 capsules each. The 22-patient study, in which individuals were randomized 1:1 to FMT or placebo capsules, didn’t show statistically significant changes in GLP-1 levels or body mass index with FMT over the 12-week study period. “But they were able to show engraftment, which I think is an important thing that you do wonder about – over this period of time, the bacteria that came from the lean donor actually engrafted into the recipient and affected the diversity. The recipient became more similar to the donor,” said Dr. Kelly.

There were some clues among the findings that engraftment was effecting metabolic change in the recipient, she said, including differences in bile acid conversion among gut bacteria; also, lower levels of the primary bile acid taurocholic acid in recipients after FMT. “So it was a negative study in what she was looking for, but an example of these smaller studies kind of pushing the field along.”

In discussing the study presented by Dr. Yu that examined lean donor FMT in individuals with insulin resistance, Dr. Kelly said, “It was actually pretty sophisticated.” By using hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamping, the investigators were able to measure insulin sensitivity based on glucose load. In this study of 24 individuals randomized 1:1 to receive FMT or placebo capsules, recipients received weekly doses over a period of 6 weeks. Here again, though Dr. Yu and colleagues again found engraftment, “they did not find the big changes in metabolic parameters that they hoped that they would,” said Dr. Kelly.

These two studies furthered previous work completed in the Netherlands examining lean donor FMT for individuals with metabolic syndrome. “Those [studies] did show both engraftment and some changes in insulin resistance,” but they were also small studies, noted Dr. Kelly. Dr. Kashyap pointed out that the earlier studies had shown in a subgroup analysis that response to FMT was limited to those patients who lacked microbial diversity pretransplant.

This makes some mechanistic sense when thinking about FMT’s greatest success to date: Treating Clostridioides difficile infection, a condition whose very hallmark is dysbiosis characterized by monospecies gut domination, noted Dr. Kashyap.

Added Dr. Kelly, “I think everyone’s hoping there’s going to be this pill that’s going to make us skinny, but I don’t think we’re going to find that with FMT and obesity. I do think these studies are important, because there’s so much animal data already, and we’re kind of like, ‘How much more can you do in mice?’ ” By translating this preclinical work into humans, the mechanisms of obesity and the role of the microbiome can be better understood.

IBS

Turning to functional bowel disorders, Dr. Kelly pointed out a new study examining FMT for IBS. “So far, the research has been pretty disappointing,” she noted. The study, presented by Prashant Singh, MBBS, a gastroenterology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, examined FMT for patients with moderate to severe diarrhea-predominant IBS. The study had four arms, randomizing the 44 participants to FMT alone; pretreatment with metronidazole and ciprofloxacin or rifaximin, each followed by FMT; or placebo. “It really didn’t show any differences in their severity of IBS in any group; so no effect: a negative study,” said Dr. Kelly.

“It’s challenging. FMT is an appealing strategy because we don’t have to put a lot of thought process into it,” said Dr. Kashyap, but it’s no panacea. “We aren’t going to be able to treat everybody with FMT.

“The challenge with IBS is that if we look at all the compositional studies, the majority of them show that at least a big subset of patients with IBS already have a normal-appearing microbiome,” said Dr. Kashyap. In those patients, “It’s very hard to know what FMT is doing.” He noted that IBS subclassifications are made by pathophysiology, without regard to the intestinal microbiome, so these classifications may not be useful for determining who may benefit from FMT.

“Again, there’s always an opportunity to learn from these studies,” whether they’re positive or negative, as long as they’re well done, said Dr. Kashyap. “There’s always an opportunity to go back and see, was there a specific subgroup of patients who responded, where there might be one or more causes which might be more amenable” to FMT.

Small intestine

And most intestinal microbial research to date, noted Dr. Kelly, has focused on the colon. “Most of our knowledge is of fecal microbiota.” New techniques including double-balloon enteroscopy of the small bowel have promise to “provide completely new information about patterns of bacteria throughout the small bowel,” and of the role of small bowel bacteria in overall gut health, she said.

“The role of the small bowel has been ignored because of accessibility,” agreed Dr. Kashyap. There’s a current focus on research into enteroscopy and other techniques to sample small intestine microbiota, he said.

In a podium presentation, Eugene Chang, MD, Martin Boyer Professor in the University of Chicago’s department of medicine, gave a broad overview of how the small intestine microbiome modulates lipid regulation. This choice of topic for the Charles M. Mansbach Memorial Lecture shows that gastroenterologists are recognizing the importance of microbiome along the entire span of the gut, said Dr. Kashyap. Dr. Chang’s approach, he added, represents a departure in that “it’s not simply just looking at what’s present and what’s not, but seeing what’s functionally relevant to metabolism.”

“We always have known that the small intestine is the workhorse; that’s where everything happens” in terms of motility, absorption, and digestion, said Dr. Kashyap. “But because of our inability to reach it easily we’ve always chosen to ignore it; we always go after the low-hanging fruit.” Despite challenges, more microbiome research should be small-bowel focused. “Eventually, it’s no pain, no gain.”