User login

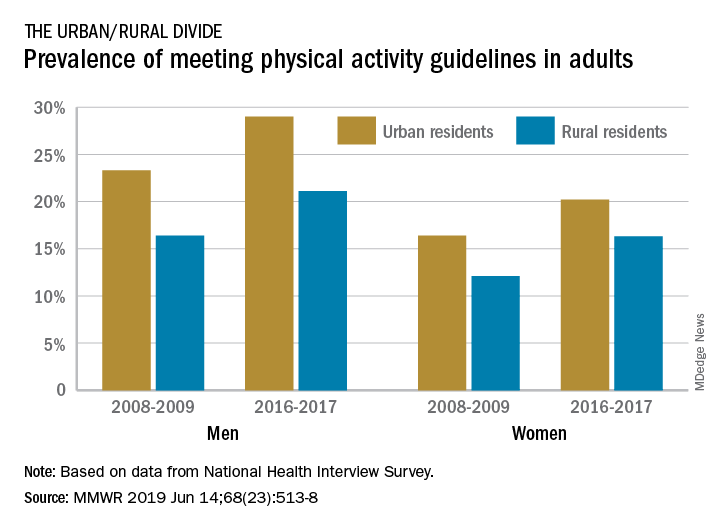

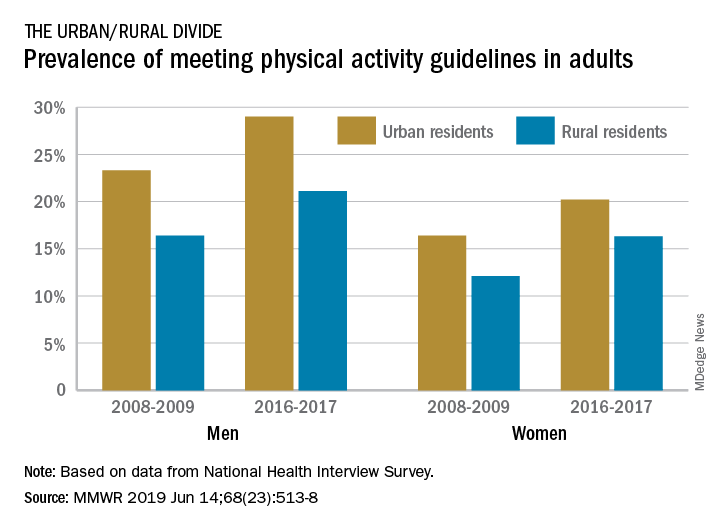

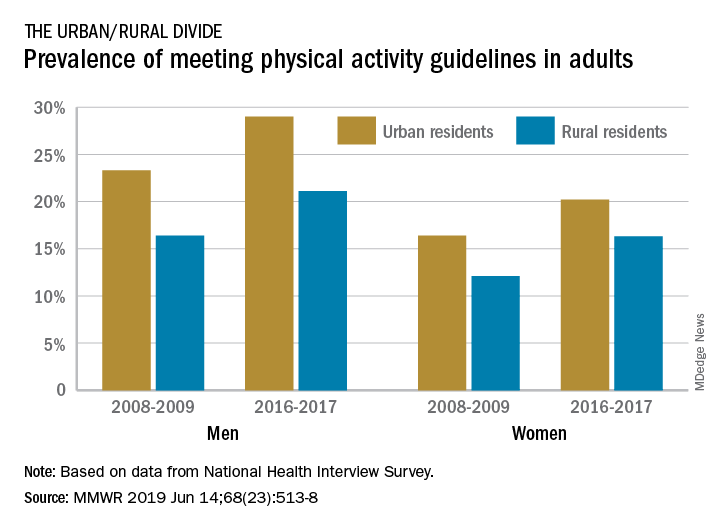

Physical activity prevalence shows urban/rural divide

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The prevalence of meeting the aerobic and muscle-strengthening recommendations in the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans rose from 18.2% of adults in 2008 to 24.3% in 2017, but despite that increase, “insufficient participation in physical activity remains a public health concern,” Geoffrey P. Whitfield, PhD, and his associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

There was progress among both urban and rural residents, but those in rural areas were behind at the start of the study period in 2008 and remained behind in 2017. The prevalence of meeting the activity guideline started at 13.3% for rural residents and 19.4% for urbanites and rose to 19.6% and 25.3%, respectively, in 2017 – that’s an annual percentage point change of 0.5% for each population, the investigators reported. Rates among women were well below those of men in both populations.

Rural communities may lack the infrastructure, such as sidewalks, schoolyards, and parks, to support physical activities, or rural residents may get more exercise through occupational and domestic tasks, rather than through the leisure-time activities that are the focus of the National Health Interview Survey, which was the source of the study data, Dr. Whitfield and his associates suggested.

The 2008 federal guidelines recommend that adults get 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, along with muscle-strengthening activities of at least moderate intensity involving all major muscle groups on 2 or more days each week.

SOURCE: Whitfield GP et al. MMWR. 2019 Jun 14;68(23):514-8.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The prevalence of meeting the aerobic and muscle-strengthening recommendations in the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans rose from 18.2% of adults in 2008 to 24.3% in 2017, but despite that increase, “insufficient participation in physical activity remains a public health concern,” Geoffrey P. Whitfield, PhD, and his associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

There was progress among both urban and rural residents, but those in rural areas were behind at the start of the study period in 2008 and remained behind in 2017. The prevalence of meeting the activity guideline started at 13.3% for rural residents and 19.4% for urbanites and rose to 19.6% and 25.3%, respectively, in 2017 – that’s an annual percentage point change of 0.5% for each population, the investigators reported. Rates among women were well below those of men in both populations.

Rural communities may lack the infrastructure, such as sidewalks, schoolyards, and parks, to support physical activities, or rural residents may get more exercise through occupational and domestic tasks, rather than through the leisure-time activities that are the focus of the National Health Interview Survey, which was the source of the study data, Dr. Whitfield and his associates suggested.

The 2008 federal guidelines recommend that adults get 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, along with muscle-strengthening activities of at least moderate intensity involving all major muscle groups on 2 or more days each week.

SOURCE: Whitfield GP et al. MMWR. 2019 Jun 14;68(23):514-8.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The prevalence of meeting the aerobic and muscle-strengthening recommendations in the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans rose from 18.2% of adults in 2008 to 24.3% in 2017, but despite that increase, “insufficient participation in physical activity remains a public health concern,” Geoffrey P. Whitfield, PhD, and his associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

There was progress among both urban and rural residents, but those in rural areas were behind at the start of the study period in 2008 and remained behind in 2017. The prevalence of meeting the activity guideline started at 13.3% for rural residents and 19.4% for urbanites and rose to 19.6% and 25.3%, respectively, in 2017 – that’s an annual percentage point change of 0.5% for each population, the investigators reported. Rates among women were well below those of men in both populations.

Rural communities may lack the infrastructure, such as sidewalks, schoolyards, and parks, to support physical activities, or rural residents may get more exercise through occupational and domestic tasks, rather than through the leisure-time activities that are the focus of the National Health Interview Survey, which was the source of the study data, Dr. Whitfield and his associates suggested.

The 2008 federal guidelines recommend that adults get 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, along with muscle-strengthening activities of at least moderate intensity involving all major muscle groups on 2 or more days each week.

SOURCE: Whitfield GP et al. MMWR. 2019 Jun 14;68(23):514-8.

FROM MMWR

Weight loss in knee OA patients sustained with liraglutide over 1 year

MADRID – The glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist liraglutide appears to be effective for keeping weight off following an intensive weight-loss program in patients with knee osteoarthritis, according to a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

However, even though the 8-week intensive dietary program led to substantial weight loss and significant improvement in pain, additional weight loss of nearly 2.5 kg over 52 weeks of daily liraglutide treatment did not translate into more pain control.

According to study author Lars Erik Kristensen, MD, PhD, this is the first randomized trial to test the ability of liraglutide to provide a sustained weight loss in OA patients. The Food and Drug Administration indication for liraglutide is as an adjunct to diet and exercise for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The study compared liraglutide against placebo in patients who had completed an intensive weight-control program in which the median loss was 12.46 kg. They were followed for 52 weeks.

At the end of follow-up, patients in the placebo group had gained a mean of 1.17 kg while those randomized to liraglutide lost an additional 2.76 kg. The between-group difference of 3.93 kg was statistically significant (P = .008).

“We believe that liraglutide is a promising agent for sustained weight loss in OA patients,” concluded Dr. Kristensen, a clinical researcher in rheumatology in the Parker Institute at Bispebjerg-Frederiksberg Hospital in Copenhagen.

In the single-center study, 156 patients were enrolled and randomized. In an initial 8-week diet intervention undertaken by both groups, an intensive program for weight loss included average daily calorie intakes of less than 800 kcal along with dietetic counseling. Patients were monitored for daily activities.

The majority of patients achieved a 10% or greater loss of total body weight during the intensive program before initiating 3 mg of once-daily liraglutide or a placebo.

Over the course of 52 weeks, the attrition from the study was relatively low. Among the 80 patients randomized to liraglutide, only 2 were lost because of noncompliance. Another 12 participants left the study before completion, 10 of whom did so for treatment-associated adverse effects. In the placebo arm, four patients were noncompliant, four left for treatment-associated adverse effects, and five left for other reasons.

Following the 8-week intensive dietary program, there was 11.86-point improvement in the pain subscale of the Knee and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, confirming a substantial symptomatic benefit from this degree of weight loss. While this improvement in pain score was sustained at 52 weeks in both groups, the additional weight loss in the liraglutide arm did not lead to additional pain control.

The lack of additional pain control in the liraglutide group was disappointing, and the reason is unclear, but Dr. Kristensen emphasized that the persistent improvement in pain control was a positive result. In patients who are overweight or obese, regardless of whether they have concomitant OA, weight loss is not only difficult to achieve but difficult to sustain even after a successful intervention.

Dr. Kristensen reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies. The trial received funding from Novo Nordisk.

SOURCE: Kristensen LE et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):71-2. Abstract OP0011. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.1375.

MADRID – The glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist liraglutide appears to be effective for keeping weight off following an intensive weight-loss program in patients with knee osteoarthritis, according to a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

However, even though the 8-week intensive dietary program led to substantial weight loss and significant improvement in pain, additional weight loss of nearly 2.5 kg over 52 weeks of daily liraglutide treatment did not translate into more pain control.

According to study author Lars Erik Kristensen, MD, PhD, this is the first randomized trial to test the ability of liraglutide to provide a sustained weight loss in OA patients. The Food and Drug Administration indication for liraglutide is as an adjunct to diet and exercise for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The study compared liraglutide against placebo in patients who had completed an intensive weight-control program in which the median loss was 12.46 kg. They were followed for 52 weeks.

At the end of follow-up, patients in the placebo group had gained a mean of 1.17 kg while those randomized to liraglutide lost an additional 2.76 kg. The between-group difference of 3.93 kg was statistically significant (P = .008).

“We believe that liraglutide is a promising agent for sustained weight loss in OA patients,” concluded Dr. Kristensen, a clinical researcher in rheumatology in the Parker Institute at Bispebjerg-Frederiksberg Hospital in Copenhagen.

In the single-center study, 156 patients were enrolled and randomized. In an initial 8-week diet intervention undertaken by both groups, an intensive program for weight loss included average daily calorie intakes of less than 800 kcal along with dietetic counseling. Patients were monitored for daily activities.

The majority of patients achieved a 10% or greater loss of total body weight during the intensive program before initiating 3 mg of once-daily liraglutide or a placebo.

Over the course of 52 weeks, the attrition from the study was relatively low. Among the 80 patients randomized to liraglutide, only 2 were lost because of noncompliance. Another 12 participants left the study before completion, 10 of whom did so for treatment-associated adverse effects. In the placebo arm, four patients were noncompliant, four left for treatment-associated adverse effects, and five left for other reasons.

Following the 8-week intensive dietary program, there was 11.86-point improvement in the pain subscale of the Knee and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, confirming a substantial symptomatic benefit from this degree of weight loss. While this improvement in pain score was sustained at 52 weeks in both groups, the additional weight loss in the liraglutide arm did not lead to additional pain control.

The lack of additional pain control in the liraglutide group was disappointing, and the reason is unclear, but Dr. Kristensen emphasized that the persistent improvement in pain control was a positive result. In patients who are overweight or obese, regardless of whether they have concomitant OA, weight loss is not only difficult to achieve but difficult to sustain even after a successful intervention.

Dr. Kristensen reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies. The trial received funding from Novo Nordisk.

SOURCE: Kristensen LE et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):71-2. Abstract OP0011. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.1375.

MADRID – The glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist liraglutide appears to be effective for keeping weight off following an intensive weight-loss program in patients with knee osteoarthritis, according to a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

However, even though the 8-week intensive dietary program led to substantial weight loss and significant improvement in pain, additional weight loss of nearly 2.5 kg over 52 weeks of daily liraglutide treatment did not translate into more pain control.

According to study author Lars Erik Kristensen, MD, PhD, this is the first randomized trial to test the ability of liraglutide to provide a sustained weight loss in OA patients. The Food and Drug Administration indication for liraglutide is as an adjunct to diet and exercise for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The study compared liraglutide against placebo in patients who had completed an intensive weight-control program in which the median loss was 12.46 kg. They were followed for 52 weeks.

At the end of follow-up, patients in the placebo group had gained a mean of 1.17 kg while those randomized to liraglutide lost an additional 2.76 kg. The between-group difference of 3.93 kg was statistically significant (P = .008).

“We believe that liraglutide is a promising agent for sustained weight loss in OA patients,” concluded Dr. Kristensen, a clinical researcher in rheumatology in the Parker Institute at Bispebjerg-Frederiksberg Hospital in Copenhagen.

In the single-center study, 156 patients were enrolled and randomized. In an initial 8-week diet intervention undertaken by both groups, an intensive program for weight loss included average daily calorie intakes of less than 800 kcal along with dietetic counseling. Patients were monitored for daily activities.

The majority of patients achieved a 10% or greater loss of total body weight during the intensive program before initiating 3 mg of once-daily liraglutide or a placebo.

Over the course of 52 weeks, the attrition from the study was relatively low. Among the 80 patients randomized to liraglutide, only 2 were lost because of noncompliance. Another 12 participants left the study before completion, 10 of whom did so for treatment-associated adverse effects. In the placebo arm, four patients were noncompliant, four left for treatment-associated adverse effects, and five left for other reasons.

Following the 8-week intensive dietary program, there was 11.86-point improvement in the pain subscale of the Knee and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, confirming a substantial symptomatic benefit from this degree of weight loss. While this improvement in pain score was sustained at 52 weeks in both groups, the additional weight loss in the liraglutide arm did not lead to additional pain control.

The lack of additional pain control in the liraglutide group was disappointing, and the reason is unclear, but Dr. Kristensen emphasized that the persistent improvement in pain control was a positive result. In patients who are overweight or obese, regardless of whether they have concomitant OA, weight loss is not only difficult to achieve but difficult to sustain even after a successful intervention.

Dr. Kristensen reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies. The trial received funding from Novo Nordisk.

SOURCE: Kristensen LE et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):71-2. Abstract OP0011. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.1375.

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

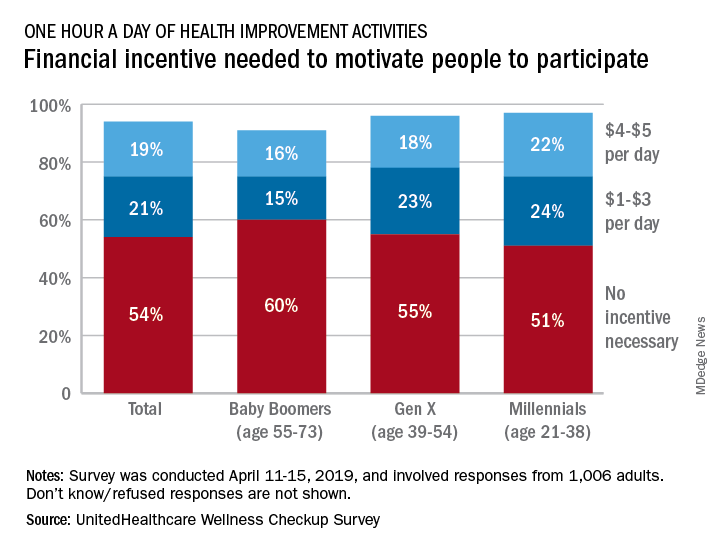

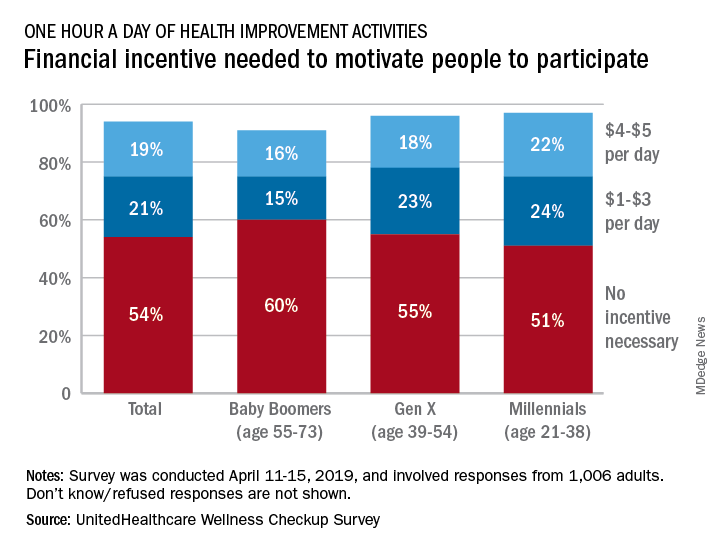

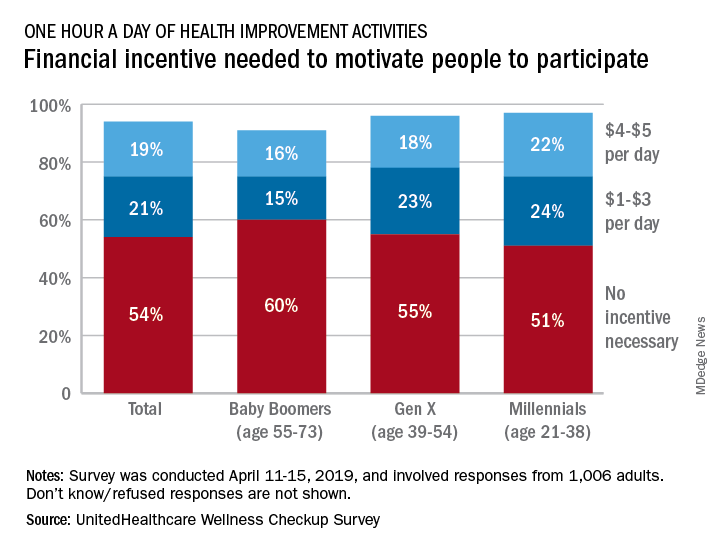

Survey puts a price on health improvement

according to a survey by UnitedHealthcare.

More than half (54%) of the 1,006 respondents said that they didn’t need a financial incentive to get that much exercise, but 21% said that $1-$3 a day would be necessary and 19% said that they would need $4-$5 per day, the company said in its 2019 Wellness Checkup Survey.

Women were more likely than men to say that they needed an incentive (42% vs. 36%). Among age-related subgroups, there was a clear progression from youngest to oldest: The youngest age group (18-34 years, 47%) and youngest generation (Millennials, 46%) in the study were the most likely to require an incentive, while the oldest age group (65 years and older, 30%) and generation (Baby Boomers, 31%) were the least likely, UnitedHealthcare said.

A majority (57%) of respondents said that it was important – either very important (19%) or somewhat important (38%) – for a fitness routine to have a social component, either in-person or virtual. Almost two-thirds of respondents expressed support for wearable fitness-tracking devices: 42% would use one if it was provided by their employer, and 22% said that they already had one, the survey results show.

“This year employers are expected to invest an average of more than $3.6 million on their respective well-being programs, and over 60% of employees are interested in engaging in these initiatives. [This] survey provides insights that we hope can be helpful to enhance the design and implementation of well-being programs, which may help improve employees’ health, reduce absenteeism, and curb care costs,” Rebecca Madsen, UnitedHealthcare’s chief consumer officer, said in the company’s written statement.

The survey was conducted April 11-15, 2019, and the margin of error was plus or minus 3.1%.

according to a survey by UnitedHealthcare.

More than half (54%) of the 1,006 respondents said that they didn’t need a financial incentive to get that much exercise, but 21% said that $1-$3 a day would be necessary and 19% said that they would need $4-$5 per day, the company said in its 2019 Wellness Checkup Survey.

Women were more likely than men to say that they needed an incentive (42% vs. 36%). Among age-related subgroups, there was a clear progression from youngest to oldest: The youngest age group (18-34 years, 47%) and youngest generation (Millennials, 46%) in the study were the most likely to require an incentive, while the oldest age group (65 years and older, 30%) and generation (Baby Boomers, 31%) were the least likely, UnitedHealthcare said.

A majority (57%) of respondents said that it was important – either very important (19%) or somewhat important (38%) – for a fitness routine to have a social component, either in-person or virtual. Almost two-thirds of respondents expressed support for wearable fitness-tracking devices: 42% would use one if it was provided by their employer, and 22% said that they already had one, the survey results show.

“This year employers are expected to invest an average of more than $3.6 million on their respective well-being programs, and over 60% of employees are interested in engaging in these initiatives. [This] survey provides insights that we hope can be helpful to enhance the design and implementation of well-being programs, which may help improve employees’ health, reduce absenteeism, and curb care costs,” Rebecca Madsen, UnitedHealthcare’s chief consumer officer, said in the company’s written statement.

The survey was conducted April 11-15, 2019, and the margin of error was plus or minus 3.1%.

according to a survey by UnitedHealthcare.

More than half (54%) of the 1,006 respondents said that they didn’t need a financial incentive to get that much exercise, but 21% said that $1-$3 a day would be necessary and 19% said that they would need $4-$5 per day, the company said in its 2019 Wellness Checkup Survey.

Women were more likely than men to say that they needed an incentive (42% vs. 36%). Among age-related subgroups, there was a clear progression from youngest to oldest: The youngest age group (18-34 years, 47%) and youngest generation (Millennials, 46%) in the study were the most likely to require an incentive, while the oldest age group (65 years and older, 30%) and generation (Baby Boomers, 31%) were the least likely, UnitedHealthcare said.

A majority (57%) of respondents said that it was important – either very important (19%) or somewhat important (38%) – for a fitness routine to have a social component, either in-person or virtual. Almost two-thirds of respondents expressed support for wearable fitness-tracking devices: 42% would use one if it was provided by their employer, and 22% said that they already had one, the survey results show.

“This year employers are expected to invest an average of more than $3.6 million on their respective well-being programs, and over 60% of employees are interested in engaging in these initiatives. [This] survey provides insights that we hope can be helpful to enhance the design and implementation of well-being programs, which may help improve employees’ health, reduce absenteeism, and curb care costs,” Rebecca Madsen, UnitedHealthcare’s chief consumer officer, said in the company’s written statement.

The survey was conducted April 11-15, 2019, and the margin of error was plus or minus 3.1%.

Drastic weight loss prevents progression to type 2 diabetes, PREVIEW data suggest

SAN FRANCISCO – And to the surprise of researchers, the results were the same regardless of dietary and exercise interventions more than 3 years after the initial weight loss.

There’s a big limitation, though: About half of the participants who initially lost weight dropped out during the 3-year study, and data about them are not yet available. Still, only 4% of those who completed the study converted to diabetes, compared with expected rates of as much as 16%.

This is a “fantastic success,” co-lead investigator and physiologist, Ian Macdonald, PhD, of the University of Nottingham (England), said in a presentation of the PREVIEW study at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The randomized, controlled, multicenter trial recruited 2,223 participants with prediabetes in several European countries and Australia and New Zealand. The participants, of whom about two-thirds were women, were aged 25-70 years (average, 52 years) and had an average body mass index of 35 kg/m2.

They were assigned to a 2-month, rapid weight-loss program in which they were limited to no more than 800 calories per day. “The participants were fully briefed on the risks to health associated with prediabetes and on the problems of diabetes itself, and they were highly motivated to take part in the study,” Dr. Macdonald said in an interview after the presentation.

A total of 1,857 participants achieved the required weight loss of at least 8% and were then assigned to one of four interventions: a high-protein, low-glycemic diet (either with moderate- or high-intensity physical activity) or a moderate-protein, moderate-glycemic diet (either with moderate- or high-intensity physical activity).

A total of 962 participants remained in the study for another 34 months until completion, with roughly the same number (235-244) in each of the four intervention groups.

The researchers expected that 16% of those in the moderate-diet group would convert to type 2 diabetes, as would 11% of those in the high-protein, low-glycemic group, Dr. Macdonald said in the presentation.

The researchers, who offered limited statistical detail about the study, did not disclose how many participants in each group actually developed diabetes by 36 months (January 2019). Dr. Macdonald said in the interview that those numbers would not be available until the study has been accepted for publication. He noted, however, that the numbers in the two groups were nearly identical, and the researchers disclosed that the overall number was just 4% (n = 62).

That number is “substantially less than would be predicted,” Dr. Macdonald noted in the presentation, adding that “there is no difference” between the interventions.

He said protein consumption in the high-protein diet was not sustained, probably because of lack of adherence. In contrast, the physical activity in the groups increased significantly at the beginning of the study, he said, and “it did not fall off too badly.”

According to Dr. Macdonald, the prevention of progression to diabetes “was almost certainly because of this large, initial weight loss, which was at least partially and impressively sustained. A high-protein, low-glycemic diet was not superior to a moderate-protein, moderate-glycemic diet in relation to prevention of type 2 diabetes.”

The study was funded by the European Union and various other sources, including national funds, in the participating countries. Dr. Macdonald reported advisory board service with Nestlé Research, European Juice Manufacturers, and Mars.

SAN FRANCISCO – And to the surprise of researchers, the results were the same regardless of dietary and exercise interventions more than 3 years after the initial weight loss.

There’s a big limitation, though: About half of the participants who initially lost weight dropped out during the 3-year study, and data about them are not yet available. Still, only 4% of those who completed the study converted to diabetes, compared with expected rates of as much as 16%.

This is a “fantastic success,” co-lead investigator and physiologist, Ian Macdonald, PhD, of the University of Nottingham (England), said in a presentation of the PREVIEW study at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The randomized, controlled, multicenter trial recruited 2,223 participants with prediabetes in several European countries and Australia and New Zealand. The participants, of whom about two-thirds were women, were aged 25-70 years (average, 52 years) and had an average body mass index of 35 kg/m2.

They were assigned to a 2-month, rapid weight-loss program in which they were limited to no more than 800 calories per day. “The participants were fully briefed on the risks to health associated with prediabetes and on the problems of diabetes itself, and they were highly motivated to take part in the study,” Dr. Macdonald said in an interview after the presentation.

A total of 1,857 participants achieved the required weight loss of at least 8% and were then assigned to one of four interventions: a high-protein, low-glycemic diet (either with moderate- or high-intensity physical activity) or a moderate-protein, moderate-glycemic diet (either with moderate- or high-intensity physical activity).

A total of 962 participants remained in the study for another 34 months until completion, with roughly the same number (235-244) in each of the four intervention groups.

The researchers expected that 16% of those in the moderate-diet group would convert to type 2 diabetes, as would 11% of those in the high-protein, low-glycemic group, Dr. Macdonald said in the presentation.

The researchers, who offered limited statistical detail about the study, did not disclose how many participants in each group actually developed diabetes by 36 months (January 2019). Dr. Macdonald said in the interview that those numbers would not be available until the study has been accepted for publication. He noted, however, that the numbers in the two groups were nearly identical, and the researchers disclosed that the overall number was just 4% (n = 62).

That number is “substantially less than would be predicted,” Dr. Macdonald noted in the presentation, adding that “there is no difference” between the interventions.

He said protein consumption in the high-protein diet was not sustained, probably because of lack of adherence. In contrast, the physical activity in the groups increased significantly at the beginning of the study, he said, and “it did not fall off too badly.”

According to Dr. Macdonald, the prevention of progression to diabetes “was almost certainly because of this large, initial weight loss, which was at least partially and impressively sustained. A high-protein, low-glycemic diet was not superior to a moderate-protein, moderate-glycemic diet in relation to prevention of type 2 diabetes.”

The study was funded by the European Union and various other sources, including national funds, in the participating countries. Dr. Macdonald reported advisory board service with Nestlé Research, European Juice Manufacturers, and Mars.

SAN FRANCISCO – And to the surprise of researchers, the results were the same regardless of dietary and exercise interventions more than 3 years after the initial weight loss.

There’s a big limitation, though: About half of the participants who initially lost weight dropped out during the 3-year study, and data about them are not yet available. Still, only 4% of those who completed the study converted to diabetes, compared with expected rates of as much as 16%.

This is a “fantastic success,” co-lead investigator and physiologist, Ian Macdonald, PhD, of the University of Nottingham (England), said in a presentation of the PREVIEW study at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The randomized, controlled, multicenter trial recruited 2,223 participants with prediabetes in several European countries and Australia and New Zealand. The participants, of whom about two-thirds were women, were aged 25-70 years (average, 52 years) and had an average body mass index of 35 kg/m2.

They were assigned to a 2-month, rapid weight-loss program in which they were limited to no more than 800 calories per day. “The participants were fully briefed on the risks to health associated with prediabetes and on the problems of diabetes itself, and they were highly motivated to take part in the study,” Dr. Macdonald said in an interview after the presentation.

A total of 1,857 participants achieved the required weight loss of at least 8% and were then assigned to one of four interventions: a high-protein, low-glycemic diet (either with moderate- or high-intensity physical activity) or a moderate-protein, moderate-glycemic diet (either with moderate- or high-intensity physical activity).

A total of 962 participants remained in the study for another 34 months until completion, with roughly the same number (235-244) in each of the four intervention groups.

The researchers expected that 16% of those in the moderate-diet group would convert to type 2 diabetes, as would 11% of those in the high-protein, low-glycemic group, Dr. Macdonald said in the presentation.

The researchers, who offered limited statistical detail about the study, did not disclose how many participants in each group actually developed diabetes by 36 months (January 2019). Dr. Macdonald said in the interview that those numbers would not be available until the study has been accepted for publication. He noted, however, that the numbers in the two groups were nearly identical, and the researchers disclosed that the overall number was just 4% (n = 62).

That number is “substantially less than would be predicted,” Dr. Macdonald noted in the presentation, adding that “there is no difference” between the interventions.

He said protein consumption in the high-protein diet was not sustained, probably because of lack of adherence. In contrast, the physical activity in the groups increased significantly at the beginning of the study, he said, and “it did not fall off too badly.”

According to Dr. Macdonald, the prevention of progression to diabetes “was almost certainly because of this large, initial weight loss, which was at least partially and impressively sustained. A high-protein, low-glycemic diet was not superior to a moderate-protein, moderate-glycemic diet in relation to prevention of type 2 diabetes.”

The study was funded by the European Union and various other sources, including national funds, in the participating countries. Dr. Macdonald reported advisory board service with Nestlé Research, European Juice Manufacturers, and Mars.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2019

Inducible nitric oxide synthase promotes insulin resistance in obesity

Obesity promotes the localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in hepatic lysosomes, leading to a cascade of downstream effects that include excess lysosomal nitric oxide production, reduced hepatic autophagy, and insulin resistance, investigators reported.

“It is well known that in the context of obesity, chronic inflammation and lysosome dysfunction coexist in the liver,” wrote Qingwen Qian, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City and associates in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Our studies suggest that lysosomal iNOS-mediated nitric oxide signaling disrupts hepatic lysosomal function, contributing to obesity-associated defective hepatic autophagy and insulin resistance.” They noted that the findings could hasten the development of new treatments for metabolic diseases.

Lysosomes recycle autophagocytosed intracellular and extracellular material, which is crucial to maintain several types of homeostasis within the liver. Each hepatocyte has about 250 lysosomes, which help regulate nutrient sensing, glycogen metabolism, cholesterol trafficking, and viral defense.

Activation of iNOS is a hallmark of inflammation, and iNOS levels are known to be elevated in the livers of patients with hepatitis C, alcoholic cirrhosis, and alpha 1-anti-trypsin disorder, the researchers wrote. “At the cellular level, iNOS produces pathological nitric oxide [NO], which triggers downstream effects, such as aberrant S-nitrosylation. These downstream effects can disrupt the function of organelles such as the mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum.”

Studies indicate that pathologic NO impairs lysosomal function in neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and kidney disease, Dr. Qian and associates noted. But it was unclear whether NO in hepatocytes was generated by local iNOS or localized to lysosomes.

The researchers therefore studied cell cultures of primary murine hepatocytes by measuring their lysosomal activity, autophagy levels, and NO levels. They also studied a murine model of diet-induced obesity in which 60% of calories were from fat. They performed glucose tolerance tests by means of intraperitoneal glucose injections and studied the effects of insulin infusion. Finally, they performed immunohistology, immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and measurements of nitrosylated proteins and lysosomal arginine in frozen liver sections from the mice. Lysosomal arginine is required to catalyze NO production in the setting of inflammation as observed in obesity. In fact, concomitant stimulation of lysosomal arginine transport and activation of mTOR (an enzyme which tightly regulates transcription factor EB) was sufficient to stimulate lysosomal NO production in hepatocytes even in the absence of an inflammatory stimulus; pointing to a central role for these processes.

The researchers found that a NO scavenger diminished lysosomal NO production, while overexpression of both mTOR and a lysomal arginine transporter upregulated lysosomal NO production and suppressed autophagy. In mice with diet-induced obesity, deleting iNOS also improved nitrosative stress in hepatic lysosomes, promoted lysosomal biogenesis by activating transcription factor EB, enhanced lysosomal function and autophagy, and improved hepatic insulin sensitivity. Improved insulin sensitivity diminished, however, when the researchers suppressed transcription factor EB or autophagy-related 7 (Atg7).

Usually, iNOS is primarily expressed in hepatic Kupffer cells, but obesity increases the expression of iNOS in hepatocytes, which promotes hepatic insulin resistance and inflammation, the researchers commented. Unpublished data indicate that deleting iNOS initially protects against obesity-linked fatty liver steatosis and insulin resistance, but that these benefits weaken over time. “Nevertheless, our data showed that liver-specific iNOS suppression has a protective role,” they wrote. “Specifically, we showed that iNOS inactivates transcription factor EB, and that suppression of transcription factor EB and Atg7 diminishes the improved hepatic insulin sensitivity by iNOS deletion.” Transcription factor EB both regulates autophagy and is a “key player in lipid metabolism,” they added. It remains unclear whether the metabolic effects of iNOS solely relate to autophagy, they noted.

Funders included the American Heart Association, American Diabetes Association, and National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qingwen Qian, et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8(1):95-110.

Understanding the mechanisms for how obesity affects cellular pathways is critical for identifying therapeutic targets to prevent its adverse consequences. The current study by Qian et al. identifies acquired lysosome dysfunction as a core cellular event that predisposes to insulin resistance in obesity. Lysosomes are degradative organelles that orchestrate cellular metabolism to facilitate homeostasis and confer stress resistance. Through a well-designed series of experiments conducted in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity, the authors demonstrate localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) to lysosomes in the livers of obese animals. This triggers excess local nitric oxide (NO) generation which leads to excessive nitrosylation of lysosomal proteins. A direct consequence of the resultant lysosome dysfunction is impaired autophagy, which is a critical cellular pathway for clearing away damaged organelles and proteins and generating energy under nutrient stress. Their studies also implicate lysosomal NO generation in suppressing the activity of transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of autophagy and lysosome biogenesis. Remarkably, genetic ablation of iNOS prevents the lysosome dysfunction and autophagy impairment, to attenuate obesity-induced insulin resistance.

Future studies will be required to assess the mechanisms for iNOS localization to the lysosomes and its interplay with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in the face of sustained nutrient excess.

Abhinav Diwan, MD, is an associate professor of medicine, cell biology, and physiology at Washington University and associate division chief of cardiology at the John Cochran VA Medical Center, both in St. Louis. He has no conflicts.

Understanding the mechanisms for how obesity affects cellular pathways is critical for identifying therapeutic targets to prevent its adverse consequences. The current study by Qian et al. identifies acquired lysosome dysfunction as a core cellular event that predisposes to insulin resistance in obesity. Lysosomes are degradative organelles that orchestrate cellular metabolism to facilitate homeostasis and confer stress resistance. Through a well-designed series of experiments conducted in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity, the authors demonstrate localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) to lysosomes in the livers of obese animals. This triggers excess local nitric oxide (NO) generation which leads to excessive nitrosylation of lysosomal proteins. A direct consequence of the resultant lysosome dysfunction is impaired autophagy, which is a critical cellular pathway for clearing away damaged organelles and proteins and generating energy under nutrient stress. Their studies also implicate lysosomal NO generation in suppressing the activity of transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of autophagy and lysosome biogenesis. Remarkably, genetic ablation of iNOS prevents the lysosome dysfunction and autophagy impairment, to attenuate obesity-induced insulin resistance.

Future studies will be required to assess the mechanisms for iNOS localization to the lysosomes and its interplay with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in the face of sustained nutrient excess.

Abhinav Diwan, MD, is an associate professor of medicine, cell biology, and physiology at Washington University and associate division chief of cardiology at the John Cochran VA Medical Center, both in St. Louis. He has no conflicts.

Understanding the mechanisms for how obesity affects cellular pathways is critical for identifying therapeutic targets to prevent its adverse consequences. The current study by Qian et al. identifies acquired lysosome dysfunction as a core cellular event that predisposes to insulin resistance in obesity. Lysosomes are degradative organelles that orchestrate cellular metabolism to facilitate homeostasis and confer stress resistance. Through a well-designed series of experiments conducted in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity, the authors demonstrate localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) to lysosomes in the livers of obese animals. This triggers excess local nitric oxide (NO) generation which leads to excessive nitrosylation of lysosomal proteins. A direct consequence of the resultant lysosome dysfunction is impaired autophagy, which is a critical cellular pathway for clearing away damaged organelles and proteins and generating energy under nutrient stress. Their studies also implicate lysosomal NO generation in suppressing the activity of transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of autophagy and lysosome biogenesis. Remarkably, genetic ablation of iNOS prevents the lysosome dysfunction and autophagy impairment, to attenuate obesity-induced insulin resistance.

Future studies will be required to assess the mechanisms for iNOS localization to the lysosomes and its interplay with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in the face of sustained nutrient excess.

Abhinav Diwan, MD, is an associate professor of medicine, cell biology, and physiology at Washington University and associate division chief of cardiology at the John Cochran VA Medical Center, both in St. Louis. He has no conflicts.

Obesity promotes the localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in hepatic lysosomes, leading to a cascade of downstream effects that include excess lysosomal nitric oxide production, reduced hepatic autophagy, and insulin resistance, investigators reported.

“It is well known that in the context of obesity, chronic inflammation and lysosome dysfunction coexist in the liver,” wrote Qingwen Qian, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City and associates in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Our studies suggest that lysosomal iNOS-mediated nitric oxide signaling disrupts hepatic lysosomal function, contributing to obesity-associated defective hepatic autophagy and insulin resistance.” They noted that the findings could hasten the development of new treatments for metabolic diseases.

Lysosomes recycle autophagocytosed intracellular and extracellular material, which is crucial to maintain several types of homeostasis within the liver. Each hepatocyte has about 250 lysosomes, which help regulate nutrient sensing, glycogen metabolism, cholesterol trafficking, and viral defense.

Activation of iNOS is a hallmark of inflammation, and iNOS levels are known to be elevated in the livers of patients with hepatitis C, alcoholic cirrhosis, and alpha 1-anti-trypsin disorder, the researchers wrote. “At the cellular level, iNOS produces pathological nitric oxide [NO], which triggers downstream effects, such as aberrant S-nitrosylation. These downstream effects can disrupt the function of organelles such as the mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum.”

Studies indicate that pathologic NO impairs lysosomal function in neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and kidney disease, Dr. Qian and associates noted. But it was unclear whether NO in hepatocytes was generated by local iNOS or localized to lysosomes.

The researchers therefore studied cell cultures of primary murine hepatocytes by measuring their lysosomal activity, autophagy levels, and NO levels. They also studied a murine model of diet-induced obesity in which 60% of calories were from fat. They performed glucose tolerance tests by means of intraperitoneal glucose injections and studied the effects of insulin infusion. Finally, they performed immunohistology, immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and measurements of nitrosylated proteins and lysosomal arginine in frozen liver sections from the mice. Lysosomal arginine is required to catalyze NO production in the setting of inflammation as observed in obesity. In fact, concomitant stimulation of lysosomal arginine transport and activation of mTOR (an enzyme which tightly regulates transcription factor EB) was sufficient to stimulate lysosomal NO production in hepatocytes even in the absence of an inflammatory stimulus; pointing to a central role for these processes.

The researchers found that a NO scavenger diminished lysosomal NO production, while overexpression of both mTOR and a lysomal arginine transporter upregulated lysosomal NO production and suppressed autophagy. In mice with diet-induced obesity, deleting iNOS also improved nitrosative stress in hepatic lysosomes, promoted lysosomal biogenesis by activating transcription factor EB, enhanced lysosomal function and autophagy, and improved hepatic insulin sensitivity. Improved insulin sensitivity diminished, however, when the researchers suppressed transcription factor EB or autophagy-related 7 (Atg7).

Usually, iNOS is primarily expressed in hepatic Kupffer cells, but obesity increases the expression of iNOS in hepatocytes, which promotes hepatic insulin resistance and inflammation, the researchers commented. Unpublished data indicate that deleting iNOS initially protects against obesity-linked fatty liver steatosis and insulin resistance, but that these benefits weaken over time. “Nevertheless, our data showed that liver-specific iNOS suppression has a protective role,” they wrote. “Specifically, we showed that iNOS inactivates transcription factor EB, and that suppression of transcription factor EB and Atg7 diminishes the improved hepatic insulin sensitivity by iNOS deletion.” Transcription factor EB both regulates autophagy and is a “key player in lipid metabolism,” they added. It remains unclear whether the metabolic effects of iNOS solely relate to autophagy, they noted.

Funders included the American Heart Association, American Diabetes Association, and National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qingwen Qian, et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8(1):95-110.

Obesity promotes the localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in hepatic lysosomes, leading to a cascade of downstream effects that include excess lysosomal nitric oxide production, reduced hepatic autophagy, and insulin resistance, investigators reported.

“It is well known that in the context of obesity, chronic inflammation and lysosome dysfunction coexist in the liver,” wrote Qingwen Qian, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City and associates in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Our studies suggest that lysosomal iNOS-mediated nitric oxide signaling disrupts hepatic lysosomal function, contributing to obesity-associated defective hepatic autophagy and insulin resistance.” They noted that the findings could hasten the development of new treatments for metabolic diseases.

Lysosomes recycle autophagocytosed intracellular and extracellular material, which is crucial to maintain several types of homeostasis within the liver. Each hepatocyte has about 250 lysosomes, which help regulate nutrient sensing, glycogen metabolism, cholesterol trafficking, and viral defense.

Activation of iNOS is a hallmark of inflammation, and iNOS levels are known to be elevated in the livers of patients with hepatitis C, alcoholic cirrhosis, and alpha 1-anti-trypsin disorder, the researchers wrote. “At the cellular level, iNOS produces pathological nitric oxide [NO], which triggers downstream effects, such as aberrant S-nitrosylation. These downstream effects can disrupt the function of organelles such as the mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum.”

Studies indicate that pathologic NO impairs lysosomal function in neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and kidney disease, Dr. Qian and associates noted. But it was unclear whether NO in hepatocytes was generated by local iNOS or localized to lysosomes.

The researchers therefore studied cell cultures of primary murine hepatocytes by measuring their lysosomal activity, autophagy levels, and NO levels. They also studied a murine model of diet-induced obesity in which 60% of calories were from fat. They performed glucose tolerance tests by means of intraperitoneal glucose injections and studied the effects of insulin infusion. Finally, they performed immunohistology, immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and measurements of nitrosylated proteins and lysosomal arginine in frozen liver sections from the mice. Lysosomal arginine is required to catalyze NO production in the setting of inflammation as observed in obesity. In fact, concomitant stimulation of lysosomal arginine transport and activation of mTOR (an enzyme which tightly regulates transcription factor EB) was sufficient to stimulate lysosomal NO production in hepatocytes even in the absence of an inflammatory stimulus; pointing to a central role for these processes.

The researchers found that a NO scavenger diminished lysosomal NO production, while overexpression of both mTOR and a lysomal arginine transporter upregulated lysosomal NO production and suppressed autophagy. In mice with diet-induced obesity, deleting iNOS also improved nitrosative stress in hepatic lysosomes, promoted lysosomal biogenesis by activating transcription factor EB, enhanced lysosomal function and autophagy, and improved hepatic insulin sensitivity. Improved insulin sensitivity diminished, however, when the researchers suppressed transcription factor EB or autophagy-related 7 (Atg7).

Usually, iNOS is primarily expressed in hepatic Kupffer cells, but obesity increases the expression of iNOS in hepatocytes, which promotes hepatic insulin resistance and inflammation, the researchers commented. Unpublished data indicate that deleting iNOS initially protects against obesity-linked fatty liver steatosis and insulin resistance, but that these benefits weaken over time. “Nevertheless, our data showed that liver-specific iNOS suppression has a protective role,” they wrote. “Specifically, we showed that iNOS inactivates transcription factor EB, and that suppression of transcription factor EB and Atg7 diminishes the improved hepatic insulin sensitivity by iNOS deletion.” Transcription factor EB both regulates autophagy and is a “key player in lipid metabolism,” they added. It remains unclear whether the metabolic effects of iNOS solely relate to autophagy, they noted.

Funders included the American Heart Association, American Diabetes Association, and National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qingwen Qian, et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8(1):95-110.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Obesity promotes the localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in hepatic lysosomes, leading to excess lysosomal nitric oxide production, reduced hepatic autophagy, and insulin resistance.

Major finding: In mice with diet-induced obesity, deleting iNOS improved nitrosative stress in hepatic lysosomes, promoted lysosomal biogenesis by activating transcription factor EB, enhanced lysosomal function and autophagy, and improved hepatic insulin sensitivity.

Study details: Studies of live primary murine hepatocytes, mice with diet-induced obesity, and liver sections from the mice.

Disclosures: Funders included the American Heart Association, American Diabetes Association, and National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Qingwen Qian et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8(1):95-110.

The urge to move

When you have a few spare minutes on your lunch break, walk by the grade school playground in your neighborhood. Even at a quick glance you will notice that almost all the children are in motion – running, chasing, or being chased. Don’t linger too long or make repeat visits because unfortunately your presence may raise suspicions about your motives. But, even on your brief visit, you will also notice that there are a few children who are sitting down either chatting with a classmate or playing by themselves. If despite my caution you returned several days in a row, you would have noticed that the sedentary outliers tend to be the same children.

Some of the children playing alone simply may be shy loners or socially inept. But I’ve always suspected that there are some people who come in the world genetically predisposed to being sedentary. You can try to make the environment more enticing and stimulating, but the children predestined to be inactive will choose to sit and watch. Not surprisingly, most of those less active children are predestined to be overweight and obese.

At least as young children we seem to be driven to be active, and it is the few outliers who are sedentary. A recent investigation from the department of health and kinesiology at Texas A&M University at College Station is beginning to shed some light on when in our evolutionary history the urge to be active was incorporated into our genome (PLOS ONE. 2019 Apr 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216155). The researchers found that snippets of DNA already known to be associated with levels of activity emerged in our ancestors before we were Homo sapiens about 500,000 years ago. This finding surprised the investigators who had suspected that this incorporation of a gene sequence driving activity was more likely to have occurred ten thousand years ago when subsistence farming and its physical demands first appeared.

The authors now postulate that the drive to be active coincided as pre–Homo sapiens grew larger and moved from a treed landscape into the open savanna (“To Move Is to Thrive. It’s in Our Genes” by Gretchen Reynolds. The New York Times, May 15, 2019). As J. Timothy Lightfoot, the senior investigator, observed, “If you were lazy then, you did not survive.”

Our observation of a playground in contact motion is probably evidence that those snippets of DNA still are buried in our genome. However, it is abundantly clear that in North America one doesn’t need to be active to survive, at least in the sense of being reproductively fit. It only takes a few us who must be physically active to grow and build things that we in the sedentary majority can buy or trade for.

There are some of us who have inherited some DNA snippets that drive us to be active post early childhood. My father walked two or three times a day until a few months before his death at 92, and not because someone told him it do it for his health. Like him, I just feel better if I have spent a couple of hours being active every day.

The challenge for us as pediatricians is to help families create environments that foster continued activity by discouraging sedentary entertainments and modeling active lifestyles. For example, simple things like choosing a spot at the periphery of the parking lot instead of close to the store. Choosing stairs instead of the elevator. Of course, anything you will be doing is artificial because the truth is we don’t need to be active to survive even though the urge to move is deeply rooted in our genes.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

When you have a few spare minutes on your lunch break, walk by the grade school playground in your neighborhood. Even at a quick glance you will notice that almost all the children are in motion – running, chasing, or being chased. Don’t linger too long or make repeat visits because unfortunately your presence may raise suspicions about your motives. But, even on your brief visit, you will also notice that there are a few children who are sitting down either chatting with a classmate or playing by themselves. If despite my caution you returned several days in a row, you would have noticed that the sedentary outliers tend to be the same children.

Some of the children playing alone simply may be shy loners or socially inept. But I’ve always suspected that there are some people who come in the world genetically predisposed to being sedentary. You can try to make the environment more enticing and stimulating, but the children predestined to be inactive will choose to sit and watch. Not surprisingly, most of those less active children are predestined to be overweight and obese.

At least as young children we seem to be driven to be active, and it is the few outliers who are sedentary. A recent investigation from the department of health and kinesiology at Texas A&M University at College Station is beginning to shed some light on when in our evolutionary history the urge to be active was incorporated into our genome (PLOS ONE. 2019 Apr 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216155). The researchers found that snippets of DNA already known to be associated with levels of activity emerged in our ancestors before we were Homo sapiens about 500,000 years ago. This finding surprised the investigators who had suspected that this incorporation of a gene sequence driving activity was more likely to have occurred ten thousand years ago when subsistence farming and its physical demands first appeared.

The authors now postulate that the drive to be active coincided as pre–Homo sapiens grew larger and moved from a treed landscape into the open savanna (“To Move Is to Thrive. It’s in Our Genes” by Gretchen Reynolds. The New York Times, May 15, 2019). As J. Timothy Lightfoot, the senior investigator, observed, “If you were lazy then, you did not survive.”

Our observation of a playground in contact motion is probably evidence that those snippets of DNA still are buried in our genome. However, it is abundantly clear that in North America one doesn’t need to be active to survive, at least in the sense of being reproductively fit. It only takes a few us who must be physically active to grow and build things that we in the sedentary majority can buy or trade for.

There are some of us who have inherited some DNA snippets that drive us to be active post early childhood. My father walked two or three times a day until a few months before his death at 92, and not because someone told him it do it for his health. Like him, I just feel better if I have spent a couple of hours being active every day.

The challenge for us as pediatricians is to help families create environments that foster continued activity by discouraging sedentary entertainments and modeling active lifestyles. For example, simple things like choosing a spot at the periphery of the parking lot instead of close to the store. Choosing stairs instead of the elevator. Of course, anything you will be doing is artificial because the truth is we don’t need to be active to survive even though the urge to move is deeply rooted in our genes.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

When you have a few spare minutes on your lunch break, walk by the grade school playground in your neighborhood. Even at a quick glance you will notice that almost all the children are in motion – running, chasing, or being chased. Don’t linger too long or make repeat visits because unfortunately your presence may raise suspicions about your motives. But, even on your brief visit, you will also notice that there are a few children who are sitting down either chatting with a classmate or playing by themselves. If despite my caution you returned several days in a row, you would have noticed that the sedentary outliers tend to be the same children.

Some of the children playing alone simply may be shy loners or socially inept. But I’ve always suspected that there are some people who come in the world genetically predisposed to being sedentary. You can try to make the environment more enticing and stimulating, but the children predestined to be inactive will choose to sit and watch. Not surprisingly, most of those less active children are predestined to be overweight and obese.

At least as young children we seem to be driven to be active, and it is the few outliers who are sedentary. A recent investigation from the department of health and kinesiology at Texas A&M University at College Station is beginning to shed some light on when in our evolutionary history the urge to be active was incorporated into our genome (PLOS ONE. 2019 Apr 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216155). The researchers found that snippets of DNA already known to be associated with levels of activity emerged in our ancestors before we were Homo sapiens about 500,000 years ago. This finding surprised the investigators who had suspected that this incorporation of a gene sequence driving activity was more likely to have occurred ten thousand years ago when subsistence farming and its physical demands first appeared.

The authors now postulate that the drive to be active coincided as pre–Homo sapiens grew larger and moved from a treed landscape into the open savanna (“To Move Is to Thrive. It’s in Our Genes” by Gretchen Reynolds. The New York Times, May 15, 2019). As J. Timothy Lightfoot, the senior investigator, observed, “If you were lazy then, you did not survive.”

Our observation of a playground in contact motion is probably evidence that those snippets of DNA still are buried in our genome. However, it is abundantly clear that in North America one doesn’t need to be active to survive, at least in the sense of being reproductively fit. It only takes a few us who must be physically active to grow and build things that we in the sedentary majority can buy or trade for.

There are some of us who have inherited some DNA snippets that drive us to be active post early childhood. My father walked two or three times a day until a few months before his death at 92, and not because someone told him it do it for his health. Like him, I just feel better if I have spent a couple of hours being active every day.

The challenge for us as pediatricians is to help families create environments that foster continued activity by discouraging sedentary entertainments and modeling active lifestyles. For example, simple things like choosing a spot at the periphery of the parking lot instead of close to the store. Choosing stairs instead of the elevator. Of course, anything you will be doing is artificial because the truth is we don’t need to be active to survive even though the urge to move is deeply rooted in our genes.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Weight-based teasing may mean further weight gain in children

according to Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and her associates.

The investigators conducted a longitudinal, observational study of 110 children who were either in the 85th body mass index (BMI) percentile or greater or had two parents with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2. Children were recruited between July 12, 1996, and July 6, 2009, administered the Perception of Teasing Scale at baseline and during follow-up, and followed for up to 15 years. Children were aged a mean of 12 years at baseline, and attended an average of nine visits.

At baseline, 53% of children were overweight, with overweight being more common in girls and in non-Hispanic whites. A total of 62% of children who were overweight at baseline reported at least one incidence of weight-based teasing (WBT), compared with 21% of children at risk. WBT at baseline was associated with BMI throughout the study (P less than .001). In addition, children who reported more WBT showed a steeper gain in BMI (P = .007). Overall, children who reported high levels of WBT had 33% greater gains in BMI per year than those with no WBT.

Fat mass was associated with WBT in a similar manner, but to an increased extent, as children who reported high levels of WBT gained 91% more fat per year than those with no WBT.

“As adolescence marks a critical period for the study of weight gain, it will be important to further explore the effects of WBT and weight‐related pressures on indices of weight and health throughout development and to identify both risk and protective factors. The present findings ... may provide a foundation upon which to initiate clinical pediatric interventions to determine whether reducing WBT affects weight and fat gain trajectory,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schvey NA et al. Pediatr Obes. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12538.

according to Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and her associates.

The investigators conducted a longitudinal, observational study of 110 children who were either in the 85th body mass index (BMI) percentile or greater or had two parents with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2. Children were recruited between July 12, 1996, and July 6, 2009, administered the Perception of Teasing Scale at baseline and during follow-up, and followed for up to 15 years. Children were aged a mean of 12 years at baseline, and attended an average of nine visits.

At baseline, 53% of children were overweight, with overweight being more common in girls and in non-Hispanic whites. A total of 62% of children who were overweight at baseline reported at least one incidence of weight-based teasing (WBT), compared with 21% of children at risk. WBT at baseline was associated with BMI throughout the study (P less than .001). In addition, children who reported more WBT showed a steeper gain in BMI (P = .007). Overall, children who reported high levels of WBT had 33% greater gains in BMI per year than those with no WBT.

Fat mass was associated with WBT in a similar manner, but to an increased extent, as children who reported high levels of WBT gained 91% more fat per year than those with no WBT.

“As adolescence marks a critical period for the study of weight gain, it will be important to further explore the effects of WBT and weight‐related pressures on indices of weight and health throughout development and to identify both risk and protective factors. The present findings ... may provide a foundation upon which to initiate clinical pediatric interventions to determine whether reducing WBT affects weight and fat gain trajectory,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schvey NA et al. Pediatr Obes. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12538.

according to Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and her associates.

The investigators conducted a longitudinal, observational study of 110 children who were either in the 85th body mass index (BMI) percentile or greater or had two parents with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2. Children were recruited between July 12, 1996, and July 6, 2009, administered the Perception of Teasing Scale at baseline and during follow-up, and followed for up to 15 years. Children were aged a mean of 12 years at baseline, and attended an average of nine visits.

At baseline, 53% of children were overweight, with overweight being more common in girls and in non-Hispanic whites. A total of 62% of children who were overweight at baseline reported at least one incidence of weight-based teasing (WBT), compared with 21% of children at risk. WBT at baseline was associated with BMI throughout the study (P less than .001). In addition, children who reported more WBT showed a steeper gain in BMI (P = .007). Overall, children who reported high levels of WBT had 33% greater gains in BMI per year than those with no WBT.

Fat mass was associated with WBT in a similar manner, but to an increased extent, as children who reported high levels of WBT gained 91% more fat per year than those with no WBT.

“As adolescence marks a critical period for the study of weight gain, it will be important to further explore the effects of WBT and weight‐related pressures on indices of weight and health throughout development and to identify both risk and protective factors. The present findings ... may provide a foundation upon which to initiate clinical pediatric interventions to determine whether reducing WBT affects weight and fat gain trajectory,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schvey NA et al. Pediatr Obes. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12538.

FROM PEDIATRIC OBESITY

Adding drugs to gastric balloons increases weight loss

SAN DIEGO – In a multicenter study involving four academic medical centers, the addition of weight loss drugs to intragastric balloons resulted in better weight loss 12 months after balloon placement.

In a video interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, study investigator Reem Sharaiha, MD, explained that one of the drawbacks of intragastric balloons is that, although they produce weight loss for the 6 or 12 months that they are in place, patients tend to regain that weight after they are removed. The study, involving 111 patients, was designed to determine whether the addition of weight loss drugs could mitigate this effect and improve weight loss, said Dr. Sharaiha of Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York.

Adding drugs such as metformin or weight loss drugs tailored to patients’ particular weight issues (cravings, anxiety, or fast gastric emptying) at the 3- or 6-month mark while the intragastric balloon was in place helped patients continue losing weight after balloon removal. At 12 months, the percentage of total body weight lost was significantly greater in the intragastric balloon group with concurrent pharmacotherapy (21.4% vs. 13.1%).

SOURCE: Shah SL et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 1105.

SAN DIEGO – In a multicenter study involving four academic medical centers, the addition of weight loss drugs to intragastric balloons resulted in better weight loss 12 months after balloon placement.

In a video interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, study investigator Reem Sharaiha, MD, explained that one of the drawbacks of intragastric balloons is that, although they produce weight loss for the 6 or 12 months that they are in place, patients tend to regain that weight after they are removed. The study, involving 111 patients, was designed to determine whether the addition of weight loss drugs could mitigate this effect and improve weight loss, said Dr. Sharaiha of Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York.

Adding drugs such as metformin or weight loss drugs tailored to patients’ particular weight issues (cravings, anxiety, or fast gastric emptying) at the 3- or 6-month mark while the intragastric balloon was in place helped patients continue losing weight after balloon removal. At 12 months, the percentage of total body weight lost was significantly greater in the intragastric balloon group with concurrent pharmacotherapy (21.4% vs. 13.1%).

SOURCE: Shah SL et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 1105.

SAN DIEGO – In a multicenter study involving four academic medical centers, the addition of weight loss drugs to intragastric balloons resulted in better weight loss 12 months after balloon placement.

In a video interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, study investigator Reem Sharaiha, MD, explained that one of the drawbacks of intragastric balloons is that, although they produce weight loss for the 6 or 12 months that they are in place, patients tend to regain that weight after they are removed. The study, involving 111 patients, was designed to determine whether the addition of weight loss drugs could mitigate this effect and improve weight loss, said Dr. Sharaiha of Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York.

Adding drugs such as metformin or weight loss drugs tailored to patients’ particular weight issues (cravings, anxiety, or fast gastric emptying) at the 3- or 6-month mark while the intragastric balloon was in place helped patients continue losing weight after balloon removal. At 12 months, the percentage of total body weight lost was significantly greater in the intragastric balloon group with concurrent pharmacotherapy (21.4% vs. 13.1%).

SOURCE: Shah SL et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 1105.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2019

Ethnicity seems to affect predisposition to components of metabolic syndrome

SAN DIEGO – .

“It appears that not all components of metabolic syndrome directly correlate with visceral fat,” lead study author Patrick Chen, DO, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

According to Dr. Chen, a gastroenterology fellow at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio, the prevalence of obesity in the United States increased from 30.5% in 2000 to 39.6% in 2015, a condition that costs the U.S. medical system $150 billion each year and is associated with 19% of all deaths. “We also know that abdominal visceral fat is more associated with mortality and cardiac events than overall adiposity, while visceral fat contributes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome,” he said.

For Asian populations, the World Health Organization has set body mass indexes of 23 kg/m2 for overweight and 27.5 kg/m2 for obesity. “This has led to an ongoing debate as to whether we should be adopting regional anthropometric criteria based on race-unique risk factors,” Dr. Chen said. “Despite all of these association studies, the mechanisms are still undergoing research and still unknown to this day.”

For the current analysis, he and his colleagues assessed the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia and the impact of increasing BMI among racial groups in the United States. They drew from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2011 to 2015 to collect and compare data on patient race, BMI, and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and used SPSS software for chi-square analysis. They excluded patients under the age of 18, those with type 1 diabetes, those with no listed race, and Native American populations, “since there were too few patients for meaningful analysis,” he said.

The 69,949 patients in the analysis included 57,448 whites, 9,281 African Americans, and 2,142 Asians. The majority (64,091) were listed as non-Hispanic, while 5,858 were listed as Hispanic. The mean age of the study population ranged from 49 to 55 years. African Americans had the highest mean BMI (31 kg/m2), followed by whites (29 kg/m2) and Asians (25 kg/m2). Meanwhile, both Hispanics and non-Hispanics had a mean BMI of 29 kg/m2.

Dr. Chen reported that African Americans (19.3%) and Asians (18.5%) had a higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes compared with whites (13.4%; P less than .001), while Hispanics had a higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes compared with non-Hispanics (18.9% vs. 13.9%; P less than .001). At the same time, African Americans had a higher prevalence of hypertension (49.6%) compared with whites (38.2%) and Asians (37.9%; P less than .001 for both associations), while non-Hispanics had a higher prevalence of hypertension compared with Hispanics (40.4% vs. 33.1%; P less than .001). Asians had a higher prevalence of hyperlipidemia (28.4%) compared with whites (25.6%; P = .004); both groups had a higher prevalence compared with African Americans (21.9%, P less than .001). Hispanics had a lower prevalence of hyperlipidemia compared with non-Hispanics (23.6% vs. 25.1%; P = .005).

“Diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia likely have different mechanisms that lead to different race’s predisposition to these diseases,” Dr. Chen concluded. “This study supports that regional anthropometric criteria should be done based on ethnicity-specific risk factors. Some food for thought is whether we need to change our screening guidelines for conditions like diabetes for Asian patients and hypertension in African American patients. We should also consider ethnicity when we look for NAFLD. Overall, continued research is needed to explain these correlations.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chen P et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 447.

SAN DIEGO – .

“It appears that not all components of metabolic syndrome directly correlate with visceral fat,” lead study author Patrick Chen, DO, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

According to Dr. Chen, a gastroenterology fellow at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio, the prevalence of obesity in the United States increased from 30.5% in 2000 to 39.6% in 2015, a condition that costs the U.S. medical system $150 billion each year and is associated with 19% of all deaths. “We also know that abdominal visceral fat is more associated with mortality and cardiac events than overall adiposity, while visceral fat contributes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome,” he said.

For Asian populations, the World Health Organization has set body mass indexes of 23 kg/m2 for overweight and 27.5 kg/m2 for obesity. “This has led to an ongoing debate as to whether we should be adopting regional anthropometric criteria based on race-unique risk factors,” Dr. Chen said. “Despite all of these association studies, the mechanisms are still undergoing research and still unknown to this day.”