User login

Expert discusses which diets are best, based on the evidence

according to a speaker at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“Evidence from studies can help clinicians and their patients develop a successful dietary management plan and achieve optimal health,” said internist Michelle Hauser, MD, clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. She also discussed evidence-based techniques to support patients in maintaining dietary modifications.

Predominantly plant‐based diets

Popular predominantly plant‐based diets include a Mediterranean diet, healthy vegetarian diet, predominantly whole-food plant‐based (WFPB) diet, and a dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH).

The DASH diet was originally designed to help patients manage their blood pressure, but evidence suggests that it also can help adults with obesity lose weight. In contrast to the DASH diet, the Mediterranean diet is not low-fat and not very restrictive. Yet the evidence suggests that the Mediterranean diet is not only helpful for losing weight but also can reduce the risk of various chronic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and cancer, Dr. Hauser said. In addition, data suggest that the Mediterranean diet may reduce the risk of all-cause mortality and lower the levels of cholesterol.

“I like to highlight all these protective effects to my patients, because even if their goal is to lose weight, knowing that hard work pays off in additional ways can keep them motivated,” Dr. Hauser stated.

A healthy vegetarian diet and a WFPB diet are similar, and both are helpful in weight loss and management of total cholesterol and LDL‐C levels. Furthermore, healthy vegetarian and WFPB diets may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes, CVD, and some cancers. Cohort study data suggest that progressively more vegetarian diets are associated with lower BMIs.

“My interpretation of these data is that predominantly plant-based diets rich in whole foods are healthful and can be done in a way that is sustainable for most,” said Dr. Hauser. However, this generally requires a lot of support at the outset to address gaps in knowledge, skills, and other potential barriers.

For example, she referred one obese patient at risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease to a registered dietitian to develop a dietary plan. The patient also attended a behavioral medicine weight management program to learn strategies such as using smaller plates, and his family attended a healthy cooking class together to improve meal planning and cooking skills.

Time‐restricted feeding

There are numerous variations of time-restricted feeding, commonly referred to as intermittent fasting, but the principles are similar – limiting food intake to a specific window of time each day or week.

Although some studies have shown that time-restricted feeding may help patients reduce adiposity and improve lipid markers, most studies comparing time-restricted feeding to a calorie-restricted diet have shown little to no difference in weight-related outcomes, Dr. Hauser said.

These data suggest that time-restricted feeding may help patients with weight loss only if time restriction helps them reduce calorie intake. She also warned that time-restrictive feeding might cause late-night cravings and might not be helpful in individuals prone to food cravings.

Low‐carbohydrate and ketogenic diets

Losing muscle mass can prevent some people from dieting, but evidence suggests that a high-fat, very low-carbohydrate diet – also called a ketogenic diet – may help patients reduce weight and fat mass while preserving fat‐free mass, Dr. Hauser said.

The evidence regarding the usefulness of a low-carbohydrate (non-keto) diet is less clear because most studies compared it to a low-fat diet, and these two diets might lead to a similar extent of weight loss.

Rating the level of scientific evidence behind different diet options

Nutrition studies do no provide the same level of evidence as drug studies, said Dr. Hauser, because it is easier to conduct a randomized controlled trial of a drug versus placebo. Diets have many more variables, and it also takes much longer to observe most outcomes of a dietary change.

In addition, clinical trials of dietary interventions are typically short and focus on disease markers such as serum lipids and hemoglobin A1c levels. To obtain reliable information on the usefulness of a diet, researchers need to collect detailed health and lifestyle information from hundreds of thousands of people over several decades, which is not always feasible. “This is why meta-analyses of pooled dietary study data are more likely to yield dependable findings,” she noted.

Getting to know patients is essential to help them maintain diet modifications

When developing a diet plan for a patient, it is important to consider the sustainability of a dietary pattern. “The benefits of any healthy dietary change will only last as long as they can be maintained,” said Dr. Hauser. “Counseling someone on choosing an appropriate long-term dietary pattern requires getting to know them – taste preferences, food traditions, barriers, facilitators, food access, and time and cost restrictions.”

In an interview after the session, David Bittleman, MD, an internist at Veterans Affairs San Diego Health Care System, agreed that getting to know patients is essential for successfully advising them on diet.

“I always start developing a diet plan by trying to find out what [a patient’s] diet is like and what their goals are. I need to know what they are already doing in order to make suggestions about what they can do to make their diet healthier,” he said.

When asked about her approach to supporting patients in the long term, Dr. Hauser said that she recommends sequential, gradual changes. Dr. Hauser added that she suggests her patients prioritize implementing dietary changes that they are confident they can maintain.

Dr. Hauser and Dr. Bittleman report no relevant financial relationships.

according to a speaker at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“Evidence from studies can help clinicians and their patients develop a successful dietary management plan and achieve optimal health,” said internist Michelle Hauser, MD, clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. She also discussed evidence-based techniques to support patients in maintaining dietary modifications.

Predominantly plant‐based diets

Popular predominantly plant‐based diets include a Mediterranean diet, healthy vegetarian diet, predominantly whole-food plant‐based (WFPB) diet, and a dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH).

The DASH diet was originally designed to help patients manage their blood pressure, but evidence suggests that it also can help adults with obesity lose weight. In contrast to the DASH diet, the Mediterranean diet is not low-fat and not very restrictive. Yet the evidence suggests that the Mediterranean diet is not only helpful for losing weight but also can reduce the risk of various chronic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and cancer, Dr. Hauser said. In addition, data suggest that the Mediterranean diet may reduce the risk of all-cause mortality and lower the levels of cholesterol.

“I like to highlight all these protective effects to my patients, because even if their goal is to lose weight, knowing that hard work pays off in additional ways can keep them motivated,” Dr. Hauser stated.

A healthy vegetarian diet and a WFPB diet are similar, and both are helpful in weight loss and management of total cholesterol and LDL‐C levels. Furthermore, healthy vegetarian and WFPB diets may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes, CVD, and some cancers. Cohort study data suggest that progressively more vegetarian diets are associated with lower BMIs.

“My interpretation of these data is that predominantly plant-based diets rich in whole foods are healthful and can be done in a way that is sustainable for most,” said Dr. Hauser. However, this generally requires a lot of support at the outset to address gaps in knowledge, skills, and other potential barriers.

For example, she referred one obese patient at risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease to a registered dietitian to develop a dietary plan. The patient also attended a behavioral medicine weight management program to learn strategies such as using smaller plates, and his family attended a healthy cooking class together to improve meal planning and cooking skills.

Time‐restricted feeding

There are numerous variations of time-restricted feeding, commonly referred to as intermittent fasting, but the principles are similar – limiting food intake to a specific window of time each day or week.

Although some studies have shown that time-restricted feeding may help patients reduce adiposity and improve lipid markers, most studies comparing time-restricted feeding to a calorie-restricted diet have shown little to no difference in weight-related outcomes, Dr. Hauser said.

These data suggest that time-restricted feeding may help patients with weight loss only if time restriction helps them reduce calorie intake. She also warned that time-restrictive feeding might cause late-night cravings and might not be helpful in individuals prone to food cravings.

Low‐carbohydrate and ketogenic diets

Losing muscle mass can prevent some people from dieting, but evidence suggests that a high-fat, very low-carbohydrate diet – also called a ketogenic diet – may help patients reduce weight and fat mass while preserving fat‐free mass, Dr. Hauser said.

The evidence regarding the usefulness of a low-carbohydrate (non-keto) diet is less clear because most studies compared it to a low-fat diet, and these two diets might lead to a similar extent of weight loss.

Rating the level of scientific evidence behind different diet options

Nutrition studies do no provide the same level of evidence as drug studies, said Dr. Hauser, because it is easier to conduct a randomized controlled trial of a drug versus placebo. Diets have many more variables, and it also takes much longer to observe most outcomes of a dietary change.

In addition, clinical trials of dietary interventions are typically short and focus on disease markers such as serum lipids and hemoglobin A1c levels. To obtain reliable information on the usefulness of a diet, researchers need to collect detailed health and lifestyle information from hundreds of thousands of people over several decades, which is not always feasible. “This is why meta-analyses of pooled dietary study data are more likely to yield dependable findings,” she noted.

Getting to know patients is essential to help them maintain diet modifications

When developing a diet plan for a patient, it is important to consider the sustainability of a dietary pattern. “The benefits of any healthy dietary change will only last as long as they can be maintained,” said Dr. Hauser. “Counseling someone on choosing an appropriate long-term dietary pattern requires getting to know them – taste preferences, food traditions, barriers, facilitators, food access, and time and cost restrictions.”

In an interview after the session, David Bittleman, MD, an internist at Veterans Affairs San Diego Health Care System, agreed that getting to know patients is essential for successfully advising them on diet.

“I always start developing a diet plan by trying to find out what [a patient’s] diet is like and what their goals are. I need to know what they are already doing in order to make suggestions about what they can do to make their diet healthier,” he said.

When asked about her approach to supporting patients in the long term, Dr. Hauser said that she recommends sequential, gradual changes. Dr. Hauser added that she suggests her patients prioritize implementing dietary changes that they are confident they can maintain.

Dr. Hauser and Dr. Bittleman report no relevant financial relationships.

according to a speaker at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“Evidence from studies can help clinicians and their patients develop a successful dietary management plan and achieve optimal health,” said internist Michelle Hauser, MD, clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. She also discussed evidence-based techniques to support patients in maintaining dietary modifications.

Predominantly plant‐based diets

Popular predominantly plant‐based diets include a Mediterranean diet, healthy vegetarian diet, predominantly whole-food plant‐based (WFPB) diet, and a dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH).

The DASH diet was originally designed to help patients manage their blood pressure, but evidence suggests that it also can help adults with obesity lose weight. In contrast to the DASH diet, the Mediterranean diet is not low-fat and not very restrictive. Yet the evidence suggests that the Mediterranean diet is not only helpful for losing weight but also can reduce the risk of various chronic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and cancer, Dr. Hauser said. In addition, data suggest that the Mediterranean diet may reduce the risk of all-cause mortality and lower the levels of cholesterol.

“I like to highlight all these protective effects to my patients, because even if their goal is to lose weight, knowing that hard work pays off in additional ways can keep them motivated,” Dr. Hauser stated.

A healthy vegetarian diet and a WFPB diet are similar, and both are helpful in weight loss and management of total cholesterol and LDL‐C levels. Furthermore, healthy vegetarian and WFPB diets may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes, CVD, and some cancers. Cohort study data suggest that progressively more vegetarian diets are associated with lower BMIs.

“My interpretation of these data is that predominantly plant-based diets rich in whole foods are healthful and can be done in a way that is sustainable for most,” said Dr. Hauser. However, this generally requires a lot of support at the outset to address gaps in knowledge, skills, and other potential barriers.

For example, she referred one obese patient at risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease to a registered dietitian to develop a dietary plan. The patient also attended a behavioral medicine weight management program to learn strategies such as using smaller plates, and his family attended a healthy cooking class together to improve meal planning and cooking skills.

Time‐restricted feeding

There are numerous variations of time-restricted feeding, commonly referred to as intermittent fasting, but the principles are similar – limiting food intake to a specific window of time each day or week.

Although some studies have shown that time-restricted feeding may help patients reduce adiposity and improve lipid markers, most studies comparing time-restricted feeding to a calorie-restricted diet have shown little to no difference in weight-related outcomes, Dr. Hauser said.

These data suggest that time-restricted feeding may help patients with weight loss only if time restriction helps them reduce calorie intake. She also warned that time-restrictive feeding might cause late-night cravings and might not be helpful in individuals prone to food cravings.

Low‐carbohydrate and ketogenic diets

Losing muscle mass can prevent some people from dieting, but evidence suggests that a high-fat, very low-carbohydrate diet – also called a ketogenic diet – may help patients reduce weight and fat mass while preserving fat‐free mass, Dr. Hauser said.

The evidence regarding the usefulness of a low-carbohydrate (non-keto) diet is less clear because most studies compared it to a low-fat diet, and these two diets might lead to a similar extent of weight loss.

Rating the level of scientific evidence behind different diet options

Nutrition studies do no provide the same level of evidence as drug studies, said Dr. Hauser, because it is easier to conduct a randomized controlled trial of a drug versus placebo. Diets have many more variables, and it also takes much longer to observe most outcomes of a dietary change.

In addition, clinical trials of dietary interventions are typically short and focus on disease markers such as serum lipids and hemoglobin A1c levels. To obtain reliable information on the usefulness of a diet, researchers need to collect detailed health and lifestyle information from hundreds of thousands of people over several decades, which is not always feasible. “This is why meta-analyses of pooled dietary study data are more likely to yield dependable findings,” she noted.

Getting to know patients is essential to help them maintain diet modifications

When developing a diet plan for a patient, it is important to consider the sustainability of a dietary pattern. “The benefits of any healthy dietary change will only last as long as they can be maintained,” said Dr. Hauser. “Counseling someone on choosing an appropriate long-term dietary pattern requires getting to know them – taste preferences, food traditions, barriers, facilitators, food access, and time and cost restrictions.”

In an interview after the session, David Bittleman, MD, an internist at Veterans Affairs San Diego Health Care System, agreed that getting to know patients is essential for successfully advising them on diet.

“I always start developing a diet plan by trying to find out what [a patient’s] diet is like and what their goals are. I need to know what they are already doing in order to make suggestions about what they can do to make their diet healthier,” he said.

When asked about her approach to supporting patients in the long term, Dr. Hauser said that she recommends sequential, gradual changes. Dr. Hauser added that she suggests her patients prioritize implementing dietary changes that they are confident they can maintain.

Dr. Hauser and Dr. Bittleman report no relevant financial relationships.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2023

10 popular diets for heart health ranked

An evidence-based analysis of 10 popular dietary patterns shows that some promote heart health better than others.

A new American Heart Association scientific statement concludes that the Mediterranean, Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH), pescatarian, and vegetarian eating patterns most strongly align with heart-healthy eating guidelines issued by the AHA in 2021, whereas the popular paleolithic (paleo) and ketogenic (keto) diets fall short.

“The good news for the public and their clinicians is that there are several dietary patterns that allow for substantial flexibility for following a heart healthy diet – DASH, Mediterranean, vegetarian,” writing-group chair Christopher Gardner, PhD, with Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“However, some of the popular diets – particularly paleo and keto – are so strictly restrictive of specific food groups that when these diets are followed as intended by their proponents, they are not aligned with the scientific evidence for a heart-healthy diet,” Dr. Gardner said.

The statement was published online in Circulation.

A tool for clinicians

“The number of different, popular dietary patterns has proliferated in recent years, and the amount of misinformation about them on social media has reached critical levels,” Dr. Gardner said in a news release.

“The public – and even many health care professionals – may rightfully be confused about heart-healthy eating, and they may feel that they don’t have the time or the training to evaluate the different diets. We hope this statement serves as a tool for clinicians and the public to understand which diets promote good cardiometabolic health,” he noted.

The writing group rated on a scale of 1-100 how well 10 popular diets or eating patterns align with AHA dietary advice for heart-healthy eating.

That advice includes consuming a wide variety of fruits and vegetables; choosing mostly whole grains instead of refined grains; using liquid plant oils rather than tropical oils; eating healthy sources of protein, such as from plants, seafood, or lean meats; minimizing added sugars and salt; limiting alcohol; choosing minimally processed foods instead of ultraprocessed foods; and following this guidance wherever food is prepared or consumed.

The 10 diets/dietary patterns were DASH, Mediterranean-style, pescatarian, ovo-lacto vegetarian, vegan, low-fat, very low–fat, low-carbohydrate, paleo, and very low–carbohydrate/keto patterns.

The diets were divided into four tiers on the basis of their scores, which ranged from a low of 31 to a high of 100.

Only the DASH eating plan got a perfect score of 100. This eating pattern is low in salt, added sugar, tropical oil, alcohol, and processed foods and high in nonstarchy vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes. Proteins are mostly plant-based, such as legumes, beans, or nuts, along with fish or seafood, lean poultry and meats, and low-fat or fat-free dairy products.

The Mediterranean eating pattern achieved a slightly lower score of 89 because unlike DASH, it allows for moderate alcohol consumption and does not address added salt.

The other two top tier eating patterns were pescatarian, with a score of 92, and vegetarian, with a score of 86.

“If implemented as intended, the top-tier dietary patterns align best with the American Heart Association’s guidance and may be adapted to respect cultural practices, food preferences and budgets to enable people to always eat this way, for the long term,” Dr. Gardner said in the release.

Vegan and low-fat diets (each with a score of 78) fell into the second tier.

Though these diets emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts while limiting alcohol and added sugars, the vegan diet is so restrictive that it could be challenging to follow long-term or when eating out and may increase the risk for vitamin B12 deficiency, which can lead to anemia, the writing group notes.

There also are concerns that low-fat diets treat all fats equally, whereas the AHA guidance calls for replacing saturated fats with healthier fats, they point out.

The third tier includes the very low–fat diet (score 72) and low-carb diet (score 64), whereas the paleo and very low–carb/keto diets fall into the fourth tier, with the lowest scores of 53 and 31, respectively.

Dr. Gardner said that it’s important to note that all 10 diet patterns “share four positive characteristics: more veggies, more whole foods, less added sugars, less refined grains.”

“These are all areas for which Americans have substantial room for improvement, and these are all things that we could work on together. Progress across these aspects would make a large difference in the heart-healthiness of the U.S. diet,” he told this news organization.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, the Council on Hypertension, and the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An evidence-based analysis of 10 popular dietary patterns shows that some promote heart health better than others.

A new American Heart Association scientific statement concludes that the Mediterranean, Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH), pescatarian, and vegetarian eating patterns most strongly align with heart-healthy eating guidelines issued by the AHA in 2021, whereas the popular paleolithic (paleo) and ketogenic (keto) diets fall short.

“The good news for the public and their clinicians is that there are several dietary patterns that allow for substantial flexibility for following a heart healthy diet – DASH, Mediterranean, vegetarian,” writing-group chair Christopher Gardner, PhD, with Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“However, some of the popular diets – particularly paleo and keto – are so strictly restrictive of specific food groups that when these diets are followed as intended by their proponents, they are not aligned with the scientific evidence for a heart-healthy diet,” Dr. Gardner said.

The statement was published online in Circulation.

A tool for clinicians

“The number of different, popular dietary patterns has proliferated in recent years, and the amount of misinformation about them on social media has reached critical levels,” Dr. Gardner said in a news release.

“The public – and even many health care professionals – may rightfully be confused about heart-healthy eating, and they may feel that they don’t have the time or the training to evaluate the different diets. We hope this statement serves as a tool for clinicians and the public to understand which diets promote good cardiometabolic health,” he noted.

The writing group rated on a scale of 1-100 how well 10 popular diets or eating patterns align with AHA dietary advice for heart-healthy eating.

That advice includes consuming a wide variety of fruits and vegetables; choosing mostly whole grains instead of refined grains; using liquid plant oils rather than tropical oils; eating healthy sources of protein, such as from plants, seafood, or lean meats; minimizing added sugars and salt; limiting alcohol; choosing minimally processed foods instead of ultraprocessed foods; and following this guidance wherever food is prepared or consumed.

The 10 diets/dietary patterns were DASH, Mediterranean-style, pescatarian, ovo-lacto vegetarian, vegan, low-fat, very low–fat, low-carbohydrate, paleo, and very low–carbohydrate/keto patterns.

The diets were divided into four tiers on the basis of their scores, which ranged from a low of 31 to a high of 100.

Only the DASH eating plan got a perfect score of 100. This eating pattern is low in salt, added sugar, tropical oil, alcohol, and processed foods and high in nonstarchy vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes. Proteins are mostly plant-based, such as legumes, beans, or nuts, along with fish or seafood, lean poultry and meats, and low-fat or fat-free dairy products.

The Mediterranean eating pattern achieved a slightly lower score of 89 because unlike DASH, it allows for moderate alcohol consumption and does not address added salt.

The other two top tier eating patterns were pescatarian, with a score of 92, and vegetarian, with a score of 86.

“If implemented as intended, the top-tier dietary patterns align best with the American Heart Association’s guidance and may be adapted to respect cultural practices, food preferences and budgets to enable people to always eat this way, for the long term,” Dr. Gardner said in the release.

Vegan and low-fat diets (each with a score of 78) fell into the second tier.

Though these diets emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts while limiting alcohol and added sugars, the vegan diet is so restrictive that it could be challenging to follow long-term or when eating out and may increase the risk for vitamin B12 deficiency, which can lead to anemia, the writing group notes.

There also are concerns that low-fat diets treat all fats equally, whereas the AHA guidance calls for replacing saturated fats with healthier fats, they point out.

The third tier includes the very low–fat diet (score 72) and low-carb diet (score 64), whereas the paleo and very low–carb/keto diets fall into the fourth tier, with the lowest scores of 53 and 31, respectively.

Dr. Gardner said that it’s important to note that all 10 diet patterns “share four positive characteristics: more veggies, more whole foods, less added sugars, less refined grains.”

“These are all areas for which Americans have substantial room for improvement, and these are all things that we could work on together. Progress across these aspects would make a large difference in the heart-healthiness of the U.S. diet,” he told this news organization.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, the Council on Hypertension, and the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An evidence-based analysis of 10 popular dietary patterns shows that some promote heart health better than others.

A new American Heart Association scientific statement concludes that the Mediterranean, Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH), pescatarian, and vegetarian eating patterns most strongly align with heart-healthy eating guidelines issued by the AHA in 2021, whereas the popular paleolithic (paleo) and ketogenic (keto) diets fall short.

“The good news for the public and their clinicians is that there are several dietary patterns that allow for substantial flexibility for following a heart healthy diet – DASH, Mediterranean, vegetarian,” writing-group chair Christopher Gardner, PhD, with Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“However, some of the popular diets – particularly paleo and keto – are so strictly restrictive of specific food groups that when these diets are followed as intended by their proponents, they are not aligned with the scientific evidence for a heart-healthy diet,” Dr. Gardner said.

The statement was published online in Circulation.

A tool for clinicians

“The number of different, popular dietary patterns has proliferated in recent years, and the amount of misinformation about them on social media has reached critical levels,” Dr. Gardner said in a news release.

“The public – and even many health care professionals – may rightfully be confused about heart-healthy eating, and they may feel that they don’t have the time or the training to evaluate the different diets. We hope this statement serves as a tool for clinicians and the public to understand which diets promote good cardiometabolic health,” he noted.

The writing group rated on a scale of 1-100 how well 10 popular diets or eating patterns align with AHA dietary advice for heart-healthy eating.

That advice includes consuming a wide variety of fruits and vegetables; choosing mostly whole grains instead of refined grains; using liquid plant oils rather than tropical oils; eating healthy sources of protein, such as from plants, seafood, or lean meats; minimizing added sugars and salt; limiting alcohol; choosing minimally processed foods instead of ultraprocessed foods; and following this guidance wherever food is prepared or consumed.

The 10 diets/dietary patterns were DASH, Mediterranean-style, pescatarian, ovo-lacto vegetarian, vegan, low-fat, very low–fat, low-carbohydrate, paleo, and very low–carbohydrate/keto patterns.

The diets were divided into four tiers on the basis of their scores, which ranged from a low of 31 to a high of 100.

Only the DASH eating plan got a perfect score of 100. This eating pattern is low in salt, added sugar, tropical oil, alcohol, and processed foods and high in nonstarchy vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes. Proteins are mostly plant-based, such as legumes, beans, or nuts, along with fish or seafood, lean poultry and meats, and low-fat or fat-free dairy products.

The Mediterranean eating pattern achieved a slightly lower score of 89 because unlike DASH, it allows for moderate alcohol consumption and does not address added salt.

The other two top tier eating patterns were pescatarian, with a score of 92, and vegetarian, with a score of 86.

“If implemented as intended, the top-tier dietary patterns align best with the American Heart Association’s guidance and may be adapted to respect cultural practices, food preferences and budgets to enable people to always eat this way, for the long term,” Dr. Gardner said in the release.

Vegan and low-fat diets (each with a score of 78) fell into the second tier.

Though these diets emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts while limiting alcohol and added sugars, the vegan diet is so restrictive that it could be challenging to follow long-term or when eating out and may increase the risk for vitamin B12 deficiency, which can lead to anemia, the writing group notes.

There also are concerns that low-fat diets treat all fats equally, whereas the AHA guidance calls for replacing saturated fats with healthier fats, they point out.

The third tier includes the very low–fat diet (score 72) and low-carb diet (score 64), whereas the paleo and very low–carb/keto diets fall into the fourth tier, with the lowest scores of 53 and 31, respectively.

Dr. Gardner said that it’s important to note that all 10 diet patterns “share four positive characteristics: more veggies, more whole foods, less added sugars, less refined grains.”

“These are all areas for which Americans have substantial room for improvement, and these are all things that we could work on together. Progress across these aspects would make a large difference in the heart-healthiness of the U.S. diet,” he told this news organization.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, the Council on Hypertension, and the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medications provide best risk-to-benefit ratio for weight loss, says expert

Lifestyle changes result in the least weight loss and may be safest, while surgery provides the most weight loss and has the greatest risk. Antiobesity medications, especially the newer ones used in combination with lifestyle changes, can provide significant and sustained weight loss with manageable side effects, said Daniel Bessesen, MD, a professor in the endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

New and more effective antiobesity medications have given internists more potential options to discuss with their patients, Dr. Bessesen said. He reviewed the pros and cons of the different options.

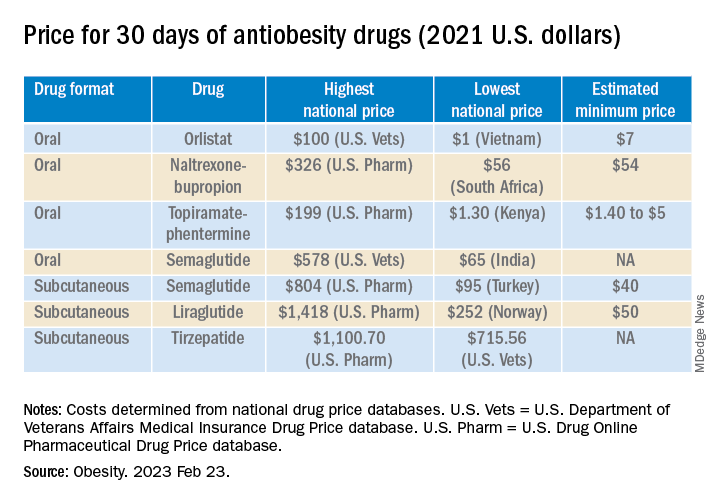

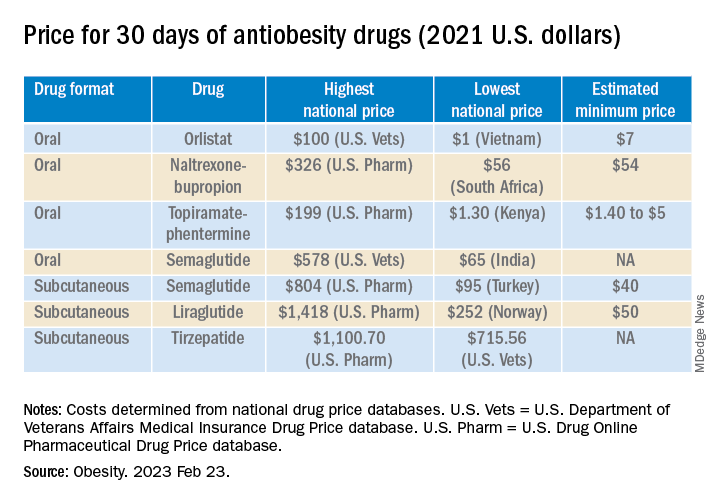

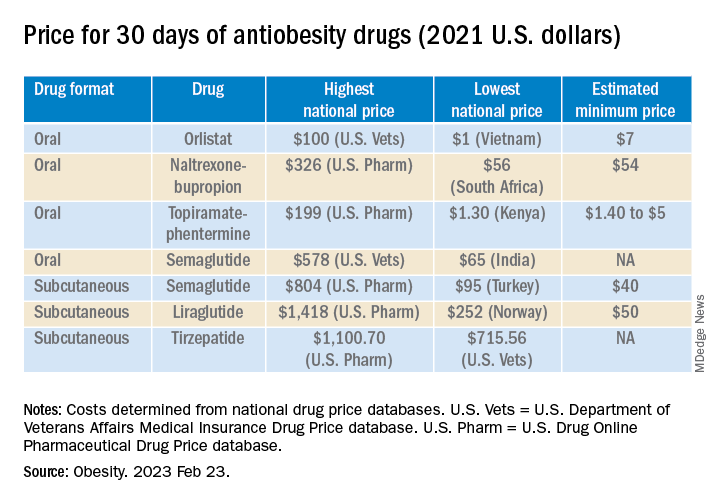

Medications are indicated for patients with a body mass index greater than 30, including those with a weight-related comorbidity, Dr. Bessesen said. The average weight loss is 5%-15% over 3-6 months but may vary greatly. Insurance often does not cover the medication costs.

Older FDA-approved antiobesity medications

Phentermine is the most widely prescribed antiobesity medication, partly because it is the only option most people can afford out of pocket. Dr. Bessesen presented recent data showing that long-term use of phentermine was associated with greater weight loss and that patients continuously taking phentermine for 24 months lost 7.5% of their weight.

Phentermine suppresses appetite by increasing norepinephrine production. Dr. Bessesen warned that internists should be careful when prescribing it to patients with mental conditions, because it acts as a stimulant. Early studies raised concerns about the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients taking phentermine. However, analysis of data from over 13,000 individuals showed no evidence of a relationship between phentermine exposure and CVD events.

“These data provide some reassurance that it could be used in patients with CVD risk,” he noted. Phentermine can also be combined with topiramate extended release, a combination that provides greater efficacy (up to 10% weight loss) with fewer side effects. However, this combination is less effective in patients with diabetes than in those without.

Additional treatment options included orlistat and naltrexone sustained release/bupropion SR. Orlistat is a good treatment alternative for patients with constipation and is the safest option among older anti-obesity medications, whereas naltrexone SR/bupropion SR may be useful in patients with food cravings. However, there is more variability in the individual-level benefit from these agents compared to phentermine and phentermine/topiramate ER, Dr. Bessesen said.

Newer anti‐obesity medications

Liraglutide, an agent used for the management of type 2 diabetes, has recently been approved for weight loss. Liraglutide causes moderate weight loss, and it may reduce the risk of CVD. However, there are tolerability issues, such as nausea and other risks, and Dr. Bessesen advises internists to “start at low doses and increase slowly.”

Semaglutide is the newest and most effective antiobesity drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration, providing sustained weight loss of 8% for up to 48 weeks after starting treatment. Although its efficacy is lower in patients with diabetes, Dr. Bessesen noted that “this is common for antiobesity agents, and clinicians should not refrain from prescribing it in this population.”

Setmelanotide is another new medication approved for chronic weight management in patients with monogenic obesity. This medication can be considered for patients with early-onset severe obesity with abnormal feeding behavior.

Commenting on barriers to access to new antiobesity medications, Dr. Bessesen said that “the high cost of these medications is a substantial problem, but as more companies become involved and products are on the market for a longer period of time, I am hopeful that prices will come down.”

Emerging antiobesity medications

Dr. Bessesen presented recent phase 3 data showing that treatment with tirzepatide provided sustained chronic loss and improved cardiometabolic measures with no diet. Tirzepatide, which targets receptors for glucagonlike peptide–1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, is used for the management of type 2 diabetes and is expected to be reviewed soon by the FDA for its use in weight management.

A semaglutide/cagrilintide combination may also provide a new treatment option for patients with obesity. In a phase 1b trial, semaglutide/cagrilintide treatment resulted in up to 17% weight loss in patients with obesity who were otherwise healthy; however, phase 2 and 3 data are needed to confirm its efficacy.

A ‘holistic approach’

When deciding whether to prescribe antiobesity medications, Dr. Bessesen noted that medications are better than exercise alone. Factors to consider when deciding whether to prescribe drugs, as well as which ones, include costs, local regulatory guidelines, requirement for long-term use, and patient comorbidities.

He also stated that lifestyle changes, such as adopting healthy nutrition and exercising regularly, are also important and can enhance weight loss when combined with medications.

Richele Corrado, DO, MPH, agreed that lifestyle management in combination with medications may provide greater weight loss than each of these interventions alone.

“If you look at the data, exercise doesn’t help you lose much weight,” said Dr. Corrado, a staff internist and obesity medicine specialist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., who spoke at the same session. She added that she has many patients who struggle to lose weight despite having a healthy lifestyle. “It’s important to discuss with these patients about medications and surgery.”

Dr. Bessesen noted that management of mental health and emotional well-being should also be an integral part of obesity management. “Treatment for obesity may be more successful when underlying psychological conditions such as depression, childhood sexual trauma, or anxiety are addressed and treated,” he said.

Dr. Bessesen was involved in the study of the efficacy of semaglutide/cagrilintide. He does not have any financial conflicts with the companies that make other mentioned medications. He has received research grants or contracts from Novo Nordisk, honoraria from Novo Nordisk, and consultantship from Eli Lilly. Dr. Corrado reported no relevant financial conflicts.

Lifestyle changes result in the least weight loss and may be safest, while surgery provides the most weight loss and has the greatest risk. Antiobesity medications, especially the newer ones used in combination with lifestyle changes, can provide significant and sustained weight loss with manageable side effects, said Daniel Bessesen, MD, a professor in the endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

New and more effective antiobesity medications have given internists more potential options to discuss with their patients, Dr. Bessesen said. He reviewed the pros and cons of the different options.

Medications are indicated for patients with a body mass index greater than 30, including those with a weight-related comorbidity, Dr. Bessesen said. The average weight loss is 5%-15% over 3-6 months but may vary greatly. Insurance often does not cover the medication costs.

Older FDA-approved antiobesity medications

Phentermine is the most widely prescribed antiobesity medication, partly because it is the only option most people can afford out of pocket. Dr. Bessesen presented recent data showing that long-term use of phentermine was associated with greater weight loss and that patients continuously taking phentermine for 24 months lost 7.5% of their weight.

Phentermine suppresses appetite by increasing norepinephrine production. Dr. Bessesen warned that internists should be careful when prescribing it to patients with mental conditions, because it acts as a stimulant. Early studies raised concerns about the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients taking phentermine. However, analysis of data from over 13,000 individuals showed no evidence of a relationship between phentermine exposure and CVD events.

“These data provide some reassurance that it could be used in patients with CVD risk,” he noted. Phentermine can also be combined with topiramate extended release, a combination that provides greater efficacy (up to 10% weight loss) with fewer side effects. However, this combination is less effective in patients with diabetes than in those without.

Additional treatment options included orlistat and naltrexone sustained release/bupropion SR. Orlistat is a good treatment alternative for patients with constipation and is the safest option among older anti-obesity medications, whereas naltrexone SR/bupropion SR may be useful in patients with food cravings. However, there is more variability in the individual-level benefit from these agents compared to phentermine and phentermine/topiramate ER, Dr. Bessesen said.

Newer anti‐obesity medications

Liraglutide, an agent used for the management of type 2 diabetes, has recently been approved for weight loss. Liraglutide causes moderate weight loss, and it may reduce the risk of CVD. However, there are tolerability issues, such as nausea and other risks, and Dr. Bessesen advises internists to “start at low doses and increase slowly.”

Semaglutide is the newest and most effective antiobesity drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration, providing sustained weight loss of 8% for up to 48 weeks after starting treatment. Although its efficacy is lower in patients with diabetes, Dr. Bessesen noted that “this is common for antiobesity agents, and clinicians should not refrain from prescribing it in this population.”

Setmelanotide is another new medication approved for chronic weight management in patients with monogenic obesity. This medication can be considered for patients with early-onset severe obesity with abnormal feeding behavior.

Commenting on barriers to access to new antiobesity medications, Dr. Bessesen said that “the high cost of these medications is a substantial problem, but as more companies become involved and products are on the market for a longer period of time, I am hopeful that prices will come down.”

Emerging antiobesity medications

Dr. Bessesen presented recent phase 3 data showing that treatment with tirzepatide provided sustained chronic loss and improved cardiometabolic measures with no diet. Tirzepatide, which targets receptors for glucagonlike peptide–1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, is used for the management of type 2 diabetes and is expected to be reviewed soon by the FDA for its use in weight management.

A semaglutide/cagrilintide combination may also provide a new treatment option for patients with obesity. In a phase 1b trial, semaglutide/cagrilintide treatment resulted in up to 17% weight loss in patients with obesity who were otherwise healthy; however, phase 2 and 3 data are needed to confirm its efficacy.

A ‘holistic approach’

When deciding whether to prescribe antiobesity medications, Dr. Bessesen noted that medications are better than exercise alone. Factors to consider when deciding whether to prescribe drugs, as well as which ones, include costs, local regulatory guidelines, requirement for long-term use, and patient comorbidities.

He also stated that lifestyle changes, such as adopting healthy nutrition and exercising regularly, are also important and can enhance weight loss when combined with medications.

Richele Corrado, DO, MPH, agreed that lifestyle management in combination with medications may provide greater weight loss than each of these interventions alone.

“If you look at the data, exercise doesn’t help you lose much weight,” said Dr. Corrado, a staff internist and obesity medicine specialist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., who spoke at the same session. She added that she has many patients who struggle to lose weight despite having a healthy lifestyle. “It’s important to discuss with these patients about medications and surgery.”

Dr. Bessesen noted that management of mental health and emotional well-being should also be an integral part of obesity management. “Treatment for obesity may be more successful when underlying psychological conditions such as depression, childhood sexual trauma, or anxiety are addressed and treated,” he said.

Dr. Bessesen was involved in the study of the efficacy of semaglutide/cagrilintide. He does not have any financial conflicts with the companies that make other mentioned medications. He has received research grants or contracts from Novo Nordisk, honoraria from Novo Nordisk, and consultantship from Eli Lilly. Dr. Corrado reported no relevant financial conflicts.

Lifestyle changes result in the least weight loss and may be safest, while surgery provides the most weight loss and has the greatest risk. Antiobesity medications, especially the newer ones used in combination with lifestyle changes, can provide significant and sustained weight loss with manageable side effects, said Daniel Bessesen, MD, a professor in the endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

New and more effective antiobesity medications have given internists more potential options to discuss with their patients, Dr. Bessesen said. He reviewed the pros and cons of the different options.

Medications are indicated for patients with a body mass index greater than 30, including those with a weight-related comorbidity, Dr. Bessesen said. The average weight loss is 5%-15% over 3-6 months but may vary greatly. Insurance often does not cover the medication costs.

Older FDA-approved antiobesity medications

Phentermine is the most widely prescribed antiobesity medication, partly because it is the only option most people can afford out of pocket. Dr. Bessesen presented recent data showing that long-term use of phentermine was associated with greater weight loss and that patients continuously taking phentermine for 24 months lost 7.5% of their weight.

Phentermine suppresses appetite by increasing norepinephrine production. Dr. Bessesen warned that internists should be careful when prescribing it to patients with mental conditions, because it acts as a stimulant. Early studies raised concerns about the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients taking phentermine. However, analysis of data from over 13,000 individuals showed no evidence of a relationship between phentermine exposure and CVD events.

“These data provide some reassurance that it could be used in patients with CVD risk,” he noted. Phentermine can also be combined with topiramate extended release, a combination that provides greater efficacy (up to 10% weight loss) with fewer side effects. However, this combination is less effective in patients with diabetes than in those without.

Additional treatment options included orlistat and naltrexone sustained release/bupropion SR. Orlistat is a good treatment alternative for patients with constipation and is the safest option among older anti-obesity medications, whereas naltrexone SR/bupropion SR may be useful in patients with food cravings. However, there is more variability in the individual-level benefit from these agents compared to phentermine and phentermine/topiramate ER, Dr. Bessesen said.

Newer anti‐obesity medications

Liraglutide, an agent used for the management of type 2 diabetes, has recently been approved for weight loss. Liraglutide causes moderate weight loss, and it may reduce the risk of CVD. However, there are tolerability issues, such as nausea and other risks, and Dr. Bessesen advises internists to “start at low doses and increase slowly.”

Semaglutide is the newest and most effective antiobesity drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration, providing sustained weight loss of 8% for up to 48 weeks after starting treatment. Although its efficacy is lower in patients with diabetes, Dr. Bessesen noted that “this is common for antiobesity agents, and clinicians should not refrain from prescribing it in this population.”

Setmelanotide is another new medication approved for chronic weight management in patients with monogenic obesity. This medication can be considered for patients with early-onset severe obesity with abnormal feeding behavior.

Commenting on barriers to access to new antiobesity medications, Dr. Bessesen said that “the high cost of these medications is a substantial problem, but as more companies become involved and products are on the market for a longer period of time, I am hopeful that prices will come down.”

Emerging antiobesity medications

Dr. Bessesen presented recent phase 3 data showing that treatment with tirzepatide provided sustained chronic loss and improved cardiometabolic measures with no diet. Tirzepatide, which targets receptors for glucagonlike peptide–1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, is used for the management of type 2 diabetes and is expected to be reviewed soon by the FDA for its use in weight management.

A semaglutide/cagrilintide combination may also provide a new treatment option for patients with obesity. In a phase 1b trial, semaglutide/cagrilintide treatment resulted in up to 17% weight loss in patients with obesity who were otherwise healthy; however, phase 2 and 3 data are needed to confirm its efficacy.

A ‘holistic approach’

When deciding whether to prescribe antiobesity medications, Dr. Bessesen noted that medications are better than exercise alone. Factors to consider when deciding whether to prescribe drugs, as well as which ones, include costs, local regulatory guidelines, requirement for long-term use, and patient comorbidities.

He also stated that lifestyle changes, such as adopting healthy nutrition and exercising regularly, are also important and can enhance weight loss when combined with medications.

Richele Corrado, DO, MPH, agreed that lifestyle management in combination with medications may provide greater weight loss than each of these interventions alone.

“If you look at the data, exercise doesn’t help you lose much weight,” said Dr. Corrado, a staff internist and obesity medicine specialist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., who spoke at the same session. She added that she has many patients who struggle to lose weight despite having a healthy lifestyle. “It’s important to discuss with these patients about medications and surgery.”

Dr. Bessesen noted that management of mental health and emotional well-being should also be an integral part of obesity management. “Treatment for obesity may be more successful when underlying psychological conditions such as depression, childhood sexual trauma, or anxiety are addressed and treated,” he said.

Dr. Bessesen was involved in the study of the efficacy of semaglutide/cagrilintide. He does not have any financial conflicts with the companies that make other mentioned medications. He has received research grants or contracts from Novo Nordisk, honoraria from Novo Nordisk, and consultantship from Eli Lilly. Dr. Corrado reported no relevant financial conflicts.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2023

Lose weight, gain huge debt: N.Y. provider has sued more than 300 patients who had bariatric surgery

Seven months after Lahavah Wallace’s weight-loss operation, a New York bariatric surgery practice sued her, accusing her of “intentionally” failing to pay nearly $18,000 of her bill.

Long Island Minimally Invasive Surgery, which does business as the New York Bariatric Group, went on to accuse Ms. Wallace of “embezzlement,” alleging she kept insurance payments that should have been turned over to the practice.

Ms. Wallace denies the allegations, which the bariatric practice has leveled against patients in hundreds of debt-collection lawsuits filed over the past 4 years, court records in New York state show.

In about 60 cases, the lawsuits demanded $100,000 or more from patients. Some patients were found liable for tens of thousands of dollars in interest charges or wound up shackled with debt that could take a decade or more to shake. Others are facing the likely prospect of six-figure financial penalties, court records show.

Backed by a major private equity firm, the bariatric practice spends millions each year on advertisements featuring patients who have dropped 100 pounds or more after bariatric procedures, sometimes having had a portion of their stomachs removed. The ads have run on TV, online, and on New York City subway posters.

The online ads, often showcasing the slogan “Stop obesity for life,” appealed to Ms. Wallace, who lives in Brooklyn and works as a legal assistant for the state of New York. She said she turned over checks from her insurer to the bariatric group and was stunned when the medical practice hauled her into court citing an “out-of-network payment agreement” she had signed before her surgery.

“I really didn’t know what I was signing,” Ms. Wallace told KFF Health News. “I didn’t pay enough attention.”

Shawn Garber, MD, a bariatric surgeon who founded the practice in 2000 on Long Island and serves as its CEO, said that “prior to rendering services” his office staff advises patients of the costs and their responsibility to pay the bill.

The bariatric group has cited these out-of-network payment agreements in at least 300 lawsuits filed against patients from January 2019 to 2022 demanding nearly $19 million to cover medical bills, interest charges, and attorney’s fees, a KFF Health News review of New York state court records found.

Danny De Voe, a partner at Sahn Ward Braff Koblenz law firm in Uniondale, N.Y., who filed many of those suits, declined to comment, citing attorney-client privilege.

In most cases, the medical practice had agreed to accept an insurance company’s out-of-network rate as full payment for its services – with caveats, according to court filings.

In the agreements they signed, patients promised to pay any coinsurance, meeting any deductible, and pass on to the medical practice any reimbursement checks they received from their health plans within 7 days.

KFF Health News found – while legal fees and other costs can layer on thousands more.

Elisabeth Benjamin, a lawyer with the Community Service Society of New York, said conflicts can arise when insurers send checks to pay for out-of-network medical services to patients rather than reimbursing a medical provider directly.

“We would prefer to see regulators step in and stop that practice,” she said, adding it “causes tension between providers and patients.”

That’s certainly true for Ms. Wallace. The surgery practice sued her in August 2022demanding $17,981 in fees it said remained unpaid after her January 2022 laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, an operation in which much of the stomach is removed to assist weight loss.

The lawsuit also tacked on a demand for $5,993 in attorney’s fees, court records show.

The suit alleges Ms. Wallace signed the contract even though she “had no intention” of paying her bills. The complaint goes on to accuse her of “committing embezzlement” by “willfully, intentionally, deliberately and maliciously” depositing checks from her health plan into her personal account.

The suit doesn’t include details to substantiate these claims, and Ms. Wallace said in her court response they are not true. Ms. Wallace said she turned over checks for the charges.

“They billed the insurance for everything they possibly could,” Ms. Wallace said.

In September, Ms. Wallace filed for bankruptcy, hoping to discharge the bariatric care debt along with about $4,700 in unrelated credit card charges.

The medical practice fired back in November by filing an “adversary complaint” in her Brooklyn bankruptcy court proceeding that argues her medical debt should not be forgiven because Ms. Wallace committed fraud.

The adversary complaint, which is pending in the bankruptcy case, accuses Ms. Wallace of “fraudulently” inducing the surgery center to perform “elective medical procedures” without requiring payment up front.

Both the harsh wording and claims of wrongdoing have infuriated Ms. Wallace and her attorney, Jacob Silver, of Brooklyn.

Mr. Silver wants the medical practice to turn over records of the payments received from Ms. Wallace. “There is no fraud here,” he said. “This is frivolous. We are taking a no-settlement position.”

Gaining debt

Few patients sued by the bariatric practice mount a defense in court and those who do fight often lose, court records show.

The medical practice won default judgments totaling nearly $6 million in about 90 of the 300 cases in the sample reviewed by KFF Health News. Default judgments are entered when the defendant fails to respond.

Many cases either are pending, or it is not clear from court filings how they were resolved.

Some patients tried to argue that the fees were too high or that they didn’t understand going in how much they could owe. One woman, trying to push back against a demand for more than $100,000, said in a legal filing that she “was given numerous papers to sign without anyone of the staff members explaining to me what it actually meant.” Another patient, who was sued for more than $40,000, wrote: “I don’t have the means to pay this bill.”

Among the cases described in court records:

- A Westchester County, N.Y., woman was sued for $102,556 and settled for $72,000 in May 2021. She agreed to pay $7,500 upon signing the settlement and $500 a month from September 2021 to May 2032.

- A Peekskill, N.Y., woman in a December 2019 judgment was held liable for $384,092, which included $94,047 in interest.

- A Newburgh, N.Y., man was sued in 2021 for $252,309 in medical bills, 12% interest, and $84,103 in attorneys’ fees. The case is pending.

Robert Cohen, a longtime attorney for the bariatric practice, testified in a November 2021 hearing that the lawyers take “a contingency fee of one-third of our recovery” in these cases. In that case, Mr. Cohen had requested $13,578 based on his contingency fee arrangement. He testified that he spent 7.3 hours on the case and that his customary billing rate was $475 per hour, which came to $3,467.50. The judge awarded the lower amount, according to a transcript of the hearing.

Teresa LaMasters, MD, president of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, said suing patients for large sums “is not a common practice” among bariatric surgeons.

“This is not what the vast majority in the field would espouse,” she said.

But Dr. Garber, the NYBG’s chief executive, suggested patients deserve blame.

“These lawsuits stem from these patients stealing the insurance money rather than forwarding it onto NYBG as they are morally and contractually obligated to do,” Dr. Garber wrote in an email to KFF Health News.

Dr. Garber added: “The issue is not with what we bill, but rather with the fact that the insurance companies refuse to send payment directly to us.”

‘A kooky system’

Defense attorneys argue that many patients don’t fully comprehend the perils of failing to pay on time – for whatever reason.

In a few cases, patients admitted pocketing checks they were obligated to turn over to the medical practice. But for the most part, court records don’t specify how many such checks were issued and for what amounts – or whether the patient improperly cashed them.

“It’s a kooky system,” said Paul Brite, an attorney who has faced off against the bariatric practice in court.

“You sign these documents that could cost you tons of money. It shouldn’t be that way,” he said. “This can ruin their financial life.”

New York lawmakers have acted to limit the damage from medical debt, including “surprise bills.”

In November, Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul signed legislation that prohibits health care providers from slapping liens on a primary residence or garnishing wages.

But contracts with onerous repayment terms represent an “evolving area of law” and an alarming “new twist” on concerns over medical debt, said Ms. Benjamin, the community service society lawyer.

She said contract “accelerator clauses” that trigger severe penalties if patients miss payments should not be permitted for medical debt.

“If you default, the full amount is due,” she said. “This is really a bummer.”

‘Fair market value’

The debt collection lawsuits argue that weight-loss patients had agreed to pay “fair market value” for services – and the doctors are only trying to secure money they are due.

But some prices far exceed typical insurance payments for obesity treatments across the country, according to a medical billing data registry. Surgeons performed about 200,000 bariatric operations in 2020, according to the bariatric surgery society.

Ms. Wallace, the Brooklyn legal assistant, was billed $60,500 for her lap sleeve gastrectomy, though how much her insurance actually paid remains to be hashed out in court.

Michael Arrigo, a California medical billing expert at No World Borders, called the prices “outrageous” and “unreasonable and, in fact, likely unconscionable.”

“I disagree that these are fair market charges,” he said.

Dr. LaMasters called the gastrectomy price billed to Ms. Wallace “really expensive” and “a severe outlier.” While charges vary by region, she quoted a typical price of around $22,000.

Dr. Garber said NYBG “bills at usual and customary rates” determined by Fair Health, a New York City-based repository of insurance claims data. Fair Health “sets these rates based upon the acceptable price for our geographic location,” he said.

But Rachel Kent, Fair Health’s senior director of marketing, told KFF Health News that the group “does not set rates, nor determine or take any position on what constitutes ‘usual and customary rates.’ ” Instead, it reports the prices providers are charging in a given area.

Overall, Fair Health data shows huge price variations even in adjacent ZIP codes in the metro area. In Long Island’s Roslyn Heights neighborhood, where NYBG is based, Fair Health lists the out-of-network price charged by providers in the area as $60,500, the figure Ms. Wallace was billed.

But in several other New York City–area ZIP codes the price charged for the gastrectomy procedure hovers around $20,000, according to the data bank. The price in Manhattan is $17,500, for instance, according to Fair Health.

Nationwide, the average cost in 2021 for bariatric surgery done in a hospital was $32,868, according to a KFF analysis of health insurance claims.

Private equity arrives

Dr. Garber said in a court affidavit in May 2022 that he founded the bariatric practice “with a singular focus: providing safe, effective care to patients suffering from obesity and its resulting complications.”

Under his leadership, the practice has “developed into New York’s elite institution for obesity treatment,” Dr. Garber said. He said the group’s surgeons are “highly sought after to train other bariatric surgeons throughout the country and are active in the development of new, cutting-edge bariatric surgery techniques.”

In 2017, Dr. Garber and partners agreed on a business plan to help spur growth and “attract private equity investment,” according to the affidavit.

They formed a separate company to handle the bariatric practice’s business side. Known as management services organizations, such companies provide a way for private equity investors to circumvent laws in some states that prohibit nonphysicians from owning a stake in a medical practice.

In August 2019, the private equity firm Sentinel Capital Partners bought 65% of the MSO for $156.5 million, according to Dr. Garber’s affidavit. The management company is now known as New You Bariatric Group. The private equity firm did not respond to requests for comment.

Dr. Garber, in a September 2021 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery webinar viewable online, said the weight-loss practice spends $6 million a year on media and marketing directly to patients – and is on a roll. Nationally, bariatric surgery is growing 6% annually, he said. NYBG boasts two dozen offices in the tri-state area of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut and is poised to expand into more states.

“Since private equity, we’ve been growing at 30%-40% year over year,” Dr. Garber said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Seven months after Lahavah Wallace’s weight-loss operation, a New York bariatric surgery practice sued her, accusing her of “intentionally” failing to pay nearly $18,000 of her bill.

Long Island Minimally Invasive Surgery, which does business as the New York Bariatric Group, went on to accuse Ms. Wallace of “embezzlement,” alleging she kept insurance payments that should have been turned over to the practice.

Ms. Wallace denies the allegations, which the bariatric practice has leveled against patients in hundreds of debt-collection lawsuits filed over the past 4 years, court records in New York state show.

In about 60 cases, the lawsuits demanded $100,000 or more from patients. Some patients were found liable for tens of thousands of dollars in interest charges or wound up shackled with debt that could take a decade or more to shake. Others are facing the likely prospect of six-figure financial penalties, court records show.

Backed by a major private equity firm, the bariatric practice spends millions each year on advertisements featuring patients who have dropped 100 pounds or more after bariatric procedures, sometimes having had a portion of their stomachs removed. The ads have run on TV, online, and on New York City subway posters.

The online ads, often showcasing the slogan “Stop obesity for life,” appealed to Ms. Wallace, who lives in Brooklyn and works as a legal assistant for the state of New York. She said she turned over checks from her insurer to the bariatric group and was stunned when the medical practice hauled her into court citing an “out-of-network payment agreement” she had signed before her surgery.

“I really didn’t know what I was signing,” Ms. Wallace told KFF Health News. “I didn’t pay enough attention.”

Shawn Garber, MD, a bariatric surgeon who founded the practice in 2000 on Long Island and serves as its CEO, said that “prior to rendering services” his office staff advises patients of the costs and their responsibility to pay the bill.

The bariatric group has cited these out-of-network payment agreements in at least 300 lawsuits filed against patients from January 2019 to 2022 demanding nearly $19 million to cover medical bills, interest charges, and attorney’s fees, a KFF Health News review of New York state court records found.

Danny De Voe, a partner at Sahn Ward Braff Koblenz law firm in Uniondale, N.Y., who filed many of those suits, declined to comment, citing attorney-client privilege.

In most cases, the medical practice had agreed to accept an insurance company’s out-of-network rate as full payment for its services – with caveats, according to court filings.

In the agreements they signed, patients promised to pay any coinsurance, meeting any deductible, and pass on to the medical practice any reimbursement checks they received from their health plans within 7 days.

KFF Health News found – while legal fees and other costs can layer on thousands more.

Elisabeth Benjamin, a lawyer with the Community Service Society of New York, said conflicts can arise when insurers send checks to pay for out-of-network medical services to patients rather than reimbursing a medical provider directly.

“We would prefer to see regulators step in and stop that practice,” she said, adding it “causes tension between providers and patients.”

That’s certainly true for Ms. Wallace. The surgery practice sued her in August 2022demanding $17,981 in fees it said remained unpaid after her January 2022 laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, an operation in which much of the stomach is removed to assist weight loss.

The lawsuit also tacked on a demand for $5,993 in attorney’s fees, court records show.

The suit alleges Ms. Wallace signed the contract even though she “had no intention” of paying her bills. The complaint goes on to accuse her of “committing embezzlement” by “willfully, intentionally, deliberately and maliciously” depositing checks from her health plan into her personal account.

The suit doesn’t include details to substantiate these claims, and Ms. Wallace said in her court response they are not true. Ms. Wallace said she turned over checks for the charges.

“They billed the insurance for everything they possibly could,” Ms. Wallace said.

In September, Ms. Wallace filed for bankruptcy, hoping to discharge the bariatric care debt along with about $4,700 in unrelated credit card charges.

The medical practice fired back in November by filing an “adversary complaint” in her Brooklyn bankruptcy court proceeding that argues her medical debt should not be forgiven because Ms. Wallace committed fraud.

The adversary complaint, which is pending in the bankruptcy case, accuses Ms. Wallace of “fraudulently” inducing the surgery center to perform “elective medical procedures” without requiring payment up front.

Both the harsh wording and claims of wrongdoing have infuriated Ms. Wallace and her attorney, Jacob Silver, of Brooklyn.

Mr. Silver wants the medical practice to turn over records of the payments received from Ms. Wallace. “There is no fraud here,” he said. “This is frivolous. We are taking a no-settlement position.”

Gaining debt

Few patients sued by the bariatric practice mount a defense in court and those who do fight often lose, court records show.

The medical practice won default judgments totaling nearly $6 million in about 90 of the 300 cases in the sample reviewed by KFF Health News. Default judgments are entered when the defendant fails to respond.

Many cases either are pending, or it is not clear from court filings how they were resolved.

Some patients tried to argue that the fees were too high or that they didn’t understand going in how much they could owe. One woman, trying to push back against a demand for more than $100,000, said in a legal filing that she “was given numerous papers to sign without anyone of the staff members explaining to me what it actually meant.” Another patient, who was sued for more than $40,000, wrote: “I don’t have the means to pay this bill.”

Among the cases described in court records:

- A Westchester County, N.Y., woman was sued for $102,556 and settled for $72,000 in May 2021. She agreed to pay $7,500 upon signing the settlement and $500 a month from September 2021 to May 2032.

- A Peekskill, N.Y., woman in a December 2019 judgment was held liable for $384,092, which included $94,047 in interest.

- A Newburgh, N.Y., man was sued in 2021 for $252,309 in medical bills, 12% interest, and $84,103 in attorneys’ fees. The case is pending.

Robert Cohen, a longtime attorney for the bariatric practice, testified in a November 2021 hearing that the lawyers take “a contingency fee of one-third of our recovery” in these cases. In that case, Mr. Cohen had requested $13,578 based on his contingency fee arrangement. He testified that he spent 7.3 hours on the case and that his customary billing rate was $475 per hour, which came to $3,467.50. The judge awarded the lower amount, according to a transcript of the hearing.

Teresa LaMasters, MD, president of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, said suing patients for large sums “is not a common practice” among bariatric surgeons.

“This is not what the vast majority in the field would espouse,” she said.

But Dr. Garber, the NYBG’s chief executive, suggested patients deserve blame.

“These lawsuits stem from these patients stealing the insurance money rather than forwarding it onto NYBG as they are morally and contractually obligated to do,” Dr. Garber wrote in an email to KFF Health News.

Dr. Garber added: “The issue is not with what we bill, but rather with the fact that the insurance companies refuse to send payment directly to us.”

‘A kooky system’

Defense attorneys argue that many patients don’t fully comprehend the perils of failing to pay on time – for whatever reason.

In a few cases, patients admitted pocketing checks they were obligated to turn over to the medical practice. But for the most part, court records don’t specify how many such checks were issued and for what amounts – or whether the patient improperly cashed them.

“It’s a kooky system,” said Paul Brite, an attorney who has faced off against the bariatric practice in court.

“You sign these documents that could cost you tons of money. It shouldn’t be that way,” he said. “This can ruin their financial life.”

New York lawmakers have acted to limit the damage from medical debt, including “surprise bills.”

In November, Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul signed legislation that prohibits health care providers from slapping liens on a primary residence or garnishing wages.

But contracts with onerous repayment terms represent an “evolving area of law” and an alarming “new twist” on concerns over medical debt, said Ms. Benjamin, the community service society lawyer.

She said contract “accelerator clauses” that trigger severe penalties if patients miss payments should not be permitted for medical debt.

“If you default, the full amount is due,” she said. “This is really a bummer.”

‘Fair market value’

The debt collection lawsuits argue that weight-loss patients had agreed to pay “fair market value” for services – and the doctors are only trying to secure money they are due.

But some prices far exceed typical insurance payments for obesity treatments across the country, according to a medical billing data registry. Surgeons performed about 200,000 bariatric operations in 2020, according to the bariatric surgery society.

Ms. Wallace, the Brooklyn legal assistant, was billed $60,500 for her lap sleeve gastrectomy, though how much her insurance actually paid remains to be hashed out in court.

Michael Arrigo, a California medical billing expert at No World Borders, called the prices “outrageous” and “unreasonable and, in fact, likely unconscionable.”

“I disagree that these are fair market charges,” he said.

Dr. LaMasters called the gastrectomy price billed to Ms. Wallace “really expensive” and “a severe outlier.” While charges vary by region, she quoted a typical price of around $22,000.

Dr. Garber said NYBG “bills at usual and customary rates” determined by Fair Health, a New York City-based repository of insurance claims data. Fair Health “sets these rates based upon the acceptable price for our geographic location,” he said.

But Rachel Kent, Fair Health’s senior director of marketing, told KFF Health News that the group “does not set rates, nor determine or take any position on what constitutes ‘usual and customary rates.’ ” Instead, it reports the prices providers are charging in a given area.

Overall, Fair Health data shows huge price variations even in adjacent ZIP codes in the metro area. In Long Island’s Roslyn Heights neighborhood, where NYBG is based, Fair Health lists the out-of-network price charged by providers in the area as $60,500, the figure Ms. Wallace was billed.

But in several other New York City–area ZIP codes the price charged for the gastrectomy procedure hovers around $20,000, according to the data bank. The price in Manhattan is $17,500, for instance, according to Fair Health.

Nationwide, the average cost in 2021 for bariatric surgery done in a hospital was $32,868, according to a KFF analysis of health insurance claims.

Private equity arrives

Dr. Garber said in a court affidavit in May 2022 that he founded the bariatric practice “with a singular focus: providing safe, effective care to patients suffering from obesity and its resulting complications.”

Under his leadership, the practice has “developed into New York’s elite institution for obesity treatment,” Dr. Garber said. He said the group’s surgeons are “highly sought after to train other bariatric surgeons throughout the country and are active in the development of new, cutting-edge bariatric surgery techniques.”

In 2017, Dr. Garber and partners agreed on a business plan to help spur growth and “attract private equity investment,” according to the affidavit.