User login

Infection Risk With Biologic Therapy for Psoriasis: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CIMPASI-1 and -2 show certolizumab pegol benefits patients with severe plaque psoriasis

ORLANDO – Results from two phase III trials indicated the tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor certolizumab pegol led to significant improvements in moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, compared with placebo, according to an oral presentation at this year’s annual Academy of Dermatology Meeting.

Across the CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2 trials, at 16 weeks, both certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) 400 mg and 200 mg, administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks in groups of patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, demonstrated statistically significant, clinically meaningful improvements in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores, and on the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) scores, when compared with placebo. The data were presented by Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at New York Medical College, Valhalla. Certolizumab pegol currently is approved in the United States for use in psoriatic arthritis, but not for psoriasis.

In CIMPASI-1, 234 mostly white male patients in their mid-40s who had moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis were randomly assigned to one of three groups. There were 88 participants in the arm given 400 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4; 95 given 200 mg at weeks 0, 2, and 4; and 51 given placebo. At week 16, the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 75 was 75.8% in the first group, 66.5% in the second, and 6.5% for placebo. A PGA scale improvement of at least two points over baseline toward a final score of clear or almost clear skin at week 16 was 57.9% for group 1, 47.0% for the second group, and 4.2% for placebo.

Also at week 16, the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 90 was 43.6% in the 400 mg dose group, 35.8% in the 200 mg dose group, and 0.4% in the placebo group.

In CIMPASI-2, 227 mostly white patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, most of whom were in their mid-40s, evenly distributed across the sexes, were randomly assigned to one of three groups. There were 87 participants in the 400 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4 group; 91 in the 200 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4 arm, and 49 in the placebo group. At week 16, 82.6% of patients in the first group and 81.4% in the second group had a PASI 75, compared with 11.6% of the placebo group. Also at 16 weeks, a PGA scale improvement of at least two points over baseline toward a final score of clear or almost clear skin at week 16 was 71.6% for group 1, 66.8% for the second group, and 2.0% for placebo. At week 16, 55.4% of patients receiving the 400 mg dose had a PASI 90, as did 52.6% of patients receiving the 200 mg dose every 2 weeks, compared with only 4.5% of the placebo group.

Additionally, Dr. Gottlieb said that at week 16, patients in the 400-mg and 200-mg groups showed significant improvements over baseline Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) average scores, compared with placebo: a 10.2 decrease in the 400-mg group and a 9.3 decrease in the 200-mg group, compared with a 3.3 decrease in the placebo arm (P less than .001) in the CIMPASI-1 study. In the CIMPASI-2 study at week 16, there was a drop of 10.0 DLQI in average scores in the 400-mg group, 10.4 in the 200-mg group, and an average drop of only 3.8 in controls (P less than .001).

Dr. Gottlieb, who disclosed that her mother suffers from severe plaque psoriasis, told the audience that the patient improvements were on par with those seen with infliximab, which she said was “the best anti–TNF alpha in the pack to date, and that’s an intravenous drug. These are impressive drops in the DLQI.”

Adverse events were, said Dr. Gottlieb, “a whole lot of nothing. There’s nothing that stands out.” She said there were no cases of tuberculosis, one case of vulvovaginal candidiasis, and equal distribution of herpes zoster across the study.

wmcknight@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Results from two phase III trials indicated the tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor certolizumab pegol led to significant improvements in moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, compared with placebo, according to an oral presentation at this year’s annual Academy of Dermatology Meeting.

Across the CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2 trials, at 16 weeks, both certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) 400 mg and 200 mg, administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks in groups of patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, demonstrated statistically significant, clinically meaningful improvements in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores, and on the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) scores, when compared with placebo. The data were presented by Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at New York Medical College, Valhalla. Certolizumab pegol currently is approved in the United States for use in psoriatic arthritis, but not for psoriasis.

In CIMPASI-1, 234 mostly white male patients in their mid-40s who had moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis were randomly assigned to one of three groups. There were 88 participants in the arm given 400 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4; 95 given 200 mg at weeks 0, 2, and 4; and 51 given placebo. At week 16, the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 75 was 75.8% in the first group, 66.5% in the second, and 6.5% for placebo. A PGA scale improvement of at least two points over baseline toward a final score of clear or almost clear skin at week 16 was 57.9% for group 1, 47.0% for the second group, and 4.2% for placebo.

Also at week 16, the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 90 was 43.6% in the 400 mg dose group, 35.8% in the 200 mg dose group, and 0.4% in the placebo group.

In CIMPASI-2, 227 mostly white patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, most of whom were in their mid-40s, evenly distributed across the sexes, were randomly assigned to one of three groups. There were 87 participants in the 400 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4 group; 91 in the 200 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4 arm, and 49 in the placebo group. At week 16, 82.6% of patients in the first group and 81.4% in the second group had a PASI 75, compared with 11.6% of the placebo group. Also at 16 weeks, a PGA scale improvement of at least two points over baseline toward a final score of clear or almost clear skin at week 16 was 71.6% for group 1, 66.8% for the second group, and 2.0% for placebo. At week 16, 55.4% of patients receiving the 400 mg dose had a PASI 90, as did 52.6% of patients receiving the 200 mg dose every 2 weeks, compared with only 4.5% of the placebo group.

Additionally, Dr. Gottlieb said that at week 16, patients in the 400-mg and 200-mg groups showed significant improvements over baseline Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) average scores, compared with placebo: a 10.2 decrease in the 400-mg group and a 9.3 decrease in the 200-mg group, compared with a 3.3 decrease in the placebo arm (P less than .001) in the CIMPASI-1 study. In the CIMPASI-2 study at week 16, there was a drop of 10.0 DLQI in average scores in the 400-mg group, 10.4 in the 200-mg group, and an average drop of only 3.8 in controls (P less than .001).

Dr. Gottlieb, who disclosed that her mother suffers from severe plaque psoriasis, told the audience that the patient improvements were on par with those seen with infliximab, which she said was “the best anti–TNF alpha in the pack to date, and that’s an intravenous drug. These are impressive drops in the DLQI.”

Adverse events were, said Dr. Gottlieb, “a whole lot of nothing. There’s nothing that stands out.” She said there were no cases of tuberculosis, one case of vulvovaginal candidiasis, and equal distribution of herpes zoster across the study.

wmcknight@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Results from two phase III trials indicated the tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor certolizumab pegol led to significant improvements in moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, compared with placebo, according to an oral presentation at this year’s annual Academy of Dermatology Meeting.

Across the CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2 trials, at 16 weeks, both certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) 400 mg and 200 mg, administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks in groups of patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, demonstrated statistically significant, clinically meaningful improvements in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores, and on the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) scores, when compared with placebo. The data were presented by Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at New York Medical College, Valhalla. Certolizumab pegol currently is approved in the United States for use in psoriatic arthritis, but not for psoriasis.

In CIMPASI-1, 234 mostly white male patients in their mid-40s who had moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis were randomly assigned to one of three groups. There were 88 participants in the arm given 400 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4; 95 given 200 mg at weeks 0, 2, and 4; and 51 given placebo. At week 16, the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 75 was 75.8% in the first group, 66.5% in the second, and 6.5% for placebo. A PGA scale improvement of at least two points over baseline toward a final score of clear or almost clear skin at week 16 was 57.9% for group 1, 47.0% for the second group, and 4.2% for placebo.

Also at week 16, the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 90 was 43.6% in the 400 mg dose group, 35.8% in the 200 mg dose group, and 0.4% in the placebo group.

In CIMPASI-2, 227 mostly white patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, most of whom were in their mid-40s, evenly distributed across the sexes, were randomly assigned to one of three groups. There were 87 participants in the 400 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4 group; 91 in the 200 mg every 2 weeks at weeks 0, 2, and 4 arm, and 49 in the placebo group. At week 16, 82.6% of patients in the first group and 81.4% in the second group had a PASI 75, compared with 11.6% of the placebo group. Also at 16 weeks, a PGA scale improvement of at least two points over baseline toward a final score of clear or almost clear skin at week 16 was 71.6% for group 1, 66.8% for the second group, and 2.0% for placebo. At week 16, 55.4% of patients receiving the 400 mg dose had a PASI 90, as did 52.6% of patients receiving the 200 mg dose every 2 weeks, compared with only 4.5% of the placebo group.

Additionally, Dr. Gottlieb said that at week 16, patients in the 400-mg and 200-mg groups showed significant improvements over baseline Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) average scores, compared with placebo: a 10.2 decrease in the 400-mg group and a 9.3 decrease in the 200-mg group, compared with a 3.3 decrease in the placebo arm (P less than .001) in the CIMPASI-1 study. In the CIMPASI-2 study at week 16, there was a drop of 10.0 DLQI in average scores in the 400-mg group, 10.4 in the 200-mg group, and an average drop of only 3.8 in controls (P less than .001).

Dr. Gottlieb, who disclosed that her mother suffers from severe plaque psoriasis, told the audience that the patient improvements were on par with those seen with infliximab, which she said was “the best anti–TNF alpha in the pack to date, and that’s an intravenous drug. These are impressive drops in the DLQI.”

Adverse events were, said Dr. Gottlieb, “a whole lot of nothing. There’s nothing that stands out.” She said there were no cases of tuberculosis, one case of vulvovaginal candidiasis, and equal distribution of herpes zoster across the study.

wmcknight@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT AAD 17

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In CIMPASI-1, at week 16, the response rate for patients who achieved a PASI 75 was 75.8% in the 400-mg group, 66.5% in the 200-mg group, and 6.5% in the placebo group.

Data source: 461 adults with moderate to severe plaque arthritis randomly assigned to either 400 mg certolizumab pegol, 200 mg of the treatment, or placebo every other week at weeks 0, 2, and 4.

Disclosures: Dr. Gottlieb had relevant disclosures, including with Dermira and UCB, the sponsors of this trial.

Psoriasis and depression may pack a PsA punch

Patients with both psoriasis and major depressive disorder face an adjusted 37% greater risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA) over a median follow-up of 5.1 years, a new study finds.

The findings don’t definitively prove that depression plays a role in PsA. Still, “,” study coauthor Cheryl Barnabe, MD, MSc, said in an interview.

For the new study published by the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, researchers tracked 73,447 people in the United Kingdom with psoriasis through a primary care medical records database for up to 25 years. The study statistics come from the years 1987-2012, reported Ryan T. Lewinson of the Cumming School of Medicine, in Calgary, Alta., and his associates (J Invest Dermatol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.032).

The median age at psoriasis diagnosis was 49.5 years (range, 20-90 years) and the median follow-up time was 5.1 years; 2% of the patients developed PsA and 7% developed major depression.

Via an unadjusted model, those with signs of depression were 1.56 times more likely to develop PsA (hazard ratio; 95% CI, 1.28-1.90; P less than .0001). In a model adjusted for factors such as age, gender, and obesity status, the extra risk of PsA was 1.37 (HR; 95% CI, 1.05-1.80; P = .021).

“The study draws into question the biological mechanisms by which depression increases the risk for developing psoriatic arthritis,” said Dr. Barnabe, an associate professor with the departments of medicine and community health sciences at the University of Calgary and a rheumatologist with Alberta Health Services.

The study notes that depression is linked to poor diet and lack of exercise, factors that could contribute to PsA. The authors also point out that researchers have linked depression to inflammation, a crucial component of both psoriasis and PsA, although they note that the study doesn’t examine systemic inflammation.

What’s next? “Mental health in chronic inflammatory diseases is not well addressed at the present time, in our system anyway, and should be a prime area of focus,” Dr. Barnabe noted. “Depression occurs at elevated rates in both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and there is certainly a role for treatment to assist with disease management.”

The study authors reported no specific study funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

Patients with both psoriasis and major depressive disorder face an adjusted 37% greater risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA) over a median follow-up of 5.1 years, a new study finds.

The findings don’t definitively prove that depression plays a role in PsA. Still, “,” study coauthor Cheryl Barnabe, MD, MSc, said in an interview.

For the new study published by the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, researchers tracked 73,447 people in the United Kingdom with psoriasis through a primary care medical records database for up to 25 years. The study statistics come from the years 1987-2012, reported Ryan T. Lewinson of the Cumming School of Medicine, in Calgary, Alta., and his associates (J Invest Dermatol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.032).

The median age at psoriasis diagnosis was 49.5 years (range, 20-90 years) and the median follow-up time was 5.1 years; 2% of the patients developed PsA and 7% developed major depression.

Via an unadjusted model, those with signs of depression were 1.56 times more likely to develop PsA (hazard ratio; 95% CI, 1.28-1.90; P less than .0001). In a model adjusted for factors such as age, gender, and obesity status, the extra risk of PsA was 1.37 (HR; 95% CI, 1.05-1.80; P = .021).

“The study draws into question the biological mechanisms by which depression increases the risk for developing psoriatic arthritis,” said Dr. Barnabe, an associate professor with the departments of medicine and community health sciences at the University of Calgary and a rheumatologist with Alberta Health Services.

The study notes that depression is linked to poor diet and lack of exercise, factors that could contribute to PsA. The authors also point out that researchers have linked depression to inflammation, a crucial component of both psoriasis and PsA, although they note that the study doesn’t examine systemic inflammation.

What’s next? “Mental health in chronic inflammatory diseases is not well addressed at the present time, in our system anyway, and should be a prime area of focus,” Dr. Barnabe noted. “Depression occurs at elevated rates in both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and there is certainly a role for treatment to assist with disease management.”

The study authors reported no specific study funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

Patients with both psoriasis and major depressive disorder face an adjusted 37% greater risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA) over a median follow-up of 5.1 years, a new study finds.

The findings don’t definitively prove that depression plays a role in PsA. Still, “,” study coauthor Cheryl Barnabe, MD, MSc, said in an interview.

For the new study published by the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, researchers tracked 73,447 people in the United Kingdom with psoriasis through a primary care medical records database for up to 25 years. The study statistics come from the years 1987-2012, reported Ryan T. Lewinson of the Cumming School of Medicine, in Calgary, Alta., and his associates (J Invest Dermatol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.032).

The median age at psoriasis diagnosis was 49.5 years (range, 20-90 years) and the median follow-up time was 5.1 years; 2% of the patients developed PsA and 7% developed major depression.

Via an unadjusted model, those with signs of depression were 1.56 times more likely to develop PsA (hazard ratio; 95% CI, 1.28-1.90; P less than .0001). In a model adjusted for factors such as age, gender, and obesity status, the extra risk of PsA was 1.37 (HR; 95% CI, 1.05-1.80; P = .021).

“The study draws into question the biological mechanisms by which depression increases the risk for developing psoriatic arthritis,” said Dr. Barnabe, an associate professor with the departments of medicine and community health sciences at the University of Calgary and a rheumatologist with Alberta Health Services.

The study notes that depression is linked to poor diet and lack of exercise, factors that could contribute to PsA. The authors also point out that researchers have linked depression to inflammation, a crucial component of both psoriasis and PsA, although they note that the study doesn’t examine systemic inflammation.

What’s next? “Mental health in chronic inflammatory diseases is not well addressed at the present time, in our system anyway, and should be a prime area of focus,” Dr. Barnabe noted. “Depression occurs at elevated rates in both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and there is certainly a role for treatment to assist with disease management.”

The study authors reported no specific study funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Depression is especially common in patients with psoriasis, and those with both conditions appear to face a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.

Major finding: In an adjusted model, patients with psoriasis and signs of major depression were 37% more likely to develop PsA.

Data source: Retrospective study of 73,447 patients with psoriasis from the U.K. tracked for up to 25 years (median follow-up, 5.1 years).

Disclosures: The authors reported no specific study funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

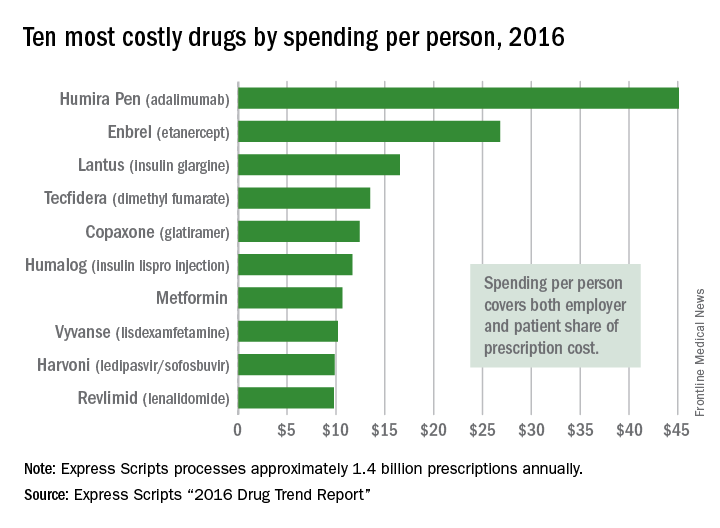

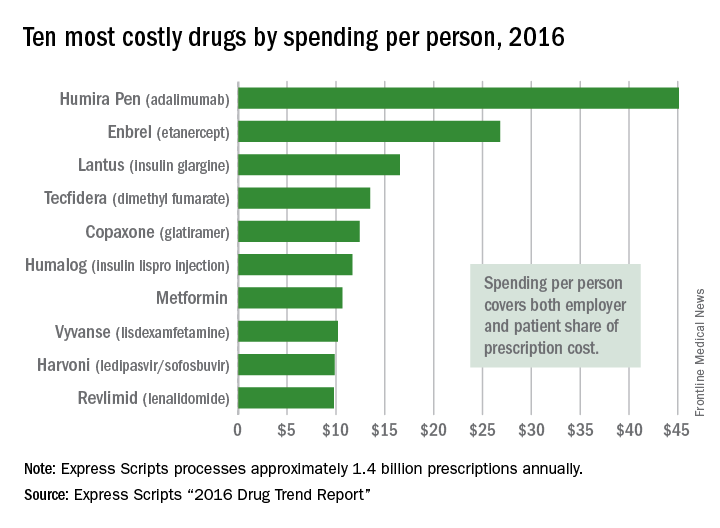

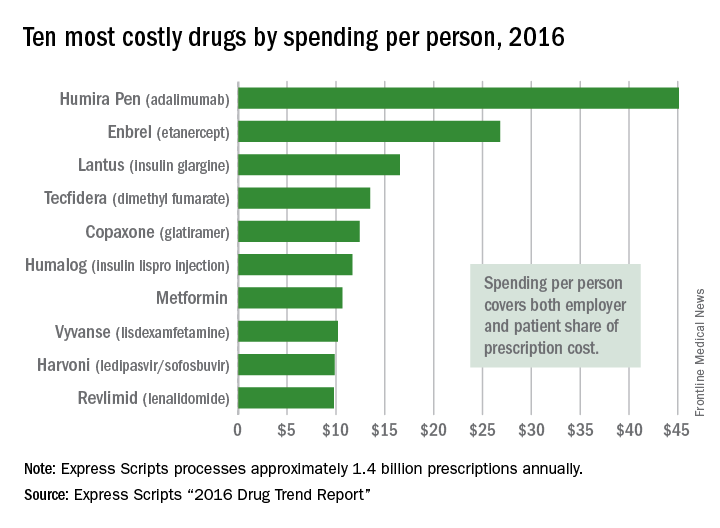

Humira Pen topped per-person drug spending in 2016

Humira Pen (adalimumab) was the most expensive drug in 2016 when ranked by spending per person, according to pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts.

Total spending per person with employer-sponsored insurance was $45.11 last year for Humira Pen, which is indicated for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. Next in spending per person was Enbrel (etanercept) – another drug for arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriasis – at $26.82, followed by the diabetes drug Lantus (insulin glargine) and two multiple sclerosis drugs: Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate) and Copaxone (glatiramer), Express Scripts said in its “2016 Drug Trend Report.”

Humira Pen had the next-largest increase from 2015 – a mere 28% – while the hepatitis C drug Harvoni (ledipasvir/sofisbuvir) had the largest decrease in per-person spending among the top 10, dropping 54%, the report noted.

Express Scripts processes approximately 1.4 billion prescriptions annually for 85 million insured members from 3,000 client companies.

Humira Pen (adalimumab) was the most expensive drug in 2016 when ranked by spending per person, according to pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts.

Total spending per person with employer-sponsored insurance was $45.11 last year for Humira Pen, which is indicated for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. Next in spending per person was Enbrel (etanercept) – another drug for arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriasis – at $26.82, followed by the diabetes drug Lantus (insulin glargine) and two multiple sclerosis drugs: Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate) and Copaxone (glatiramer), Express Scripts said in its “2016 Drug Trend Report.”

Humira Pen had the next-largest increase from 2015 – a mere 28% – while the hepatitis C drug Harvoni (ledipasvir/sofisbuvir) had the largest decrease in per-person spending among the top 10, dropping 54%, the report noted.

Express Scripts processes approximately 1.4 billion prescriptions annually for 85 million insured members from 3,000 client companies.

Humira Pen (adalimumab) was the most expensive drug in 2016 when ranked by spending per person, according to pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts.

Total spending per person with employer-sponsored insurance was $45.11 last year for Humira Pen, which is indicated for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. Next in spending per person was Enbrel (etanercept) – another drug for arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriasis – at $26.82, followed by the diabetes drug Lantus (insulin glargine) and two multiple sclerosis drugs: Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate) and Copaxone (glatiramer), Express Scripts said in its “2016 Drug Trend Report.”

Humira Pen had the next-largest increase from 2015 – a mere 28% – while the hepatitis C drug Harvoni (ledipasvir/sofisbuvir) had the largest decrease in per-person spending among the top 10, dropping 54%, the report noted.

Express Scripts processes approximately 1.4 billion prescriptions annually for 85 million insured members from 3,000 client companies.

Brodalumab approved for psoriasis with REMS required

The Food and Drug Administration has approved brodalumab, an interleukin-17 receptor A-antagonist, for treating adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) that addresses the “observed risk of suicidal ideation and behavior” in clinical trials, the agency announced on Feb. 16.

In the three pivotal phase III studies of 4,373 adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy, 83%-86% of those treated with brodalumab achieved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) scores at 12 weeks of treatment, compared with 3%-8% of those on placebo. In addition, 37%-44% of those on brodalumab achieved PASI 100 scores, compared with 1% or fewer of those on placebo. In the psoriasis clinical trials, suicidal ideation and behavior, which included four completed suicides, occurred in patients treated with brodalumab, according to the prescribing information

In the statement, the FDA points out that “a causal association between treatment with Siliq and increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior has not been established,” but that “suicidal ideation and behavior, including completed suicides, have occurred in patients treated with Siliq during clinical trials. Siliq users with a history of suicidality or depression had an increased incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior, compared to users without this history.”

At a meeting in July 2016, the FDA’s Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 18-0 in favor of approving brodalumab, with the majority (14) recommending risk management options beyond labeling to address these concerns.

Elements of the REMS include requirements for prescribers, pharmacy certification, and a medication guide for patients with information about the risks of suicidal ideation and behavior. Prescribers are required to counsel patients about this risk, and patients are required to sign a “Patient-Prescriber Agreement Form and be made aware of the need to seek medical attention should they experience new or worsening suicidal thoughts or behavior, feelings of depression, anxiety or other mood changes,” the FDA said. The prescribing information also includes a boxed warning about suicidal ideation and behavior.

The most common adverse events associated with brodalumab, the FDA statement noted, include arthralgia, headache, fatigue, diarrhea, oropharyngeal pain, nausea, myalgia, injection site reactions, neutropenia, and fungal infections. The recommended dose of brodalumab is 210 mg, administered subcutaneously, at weeks 0, 1, and 2, followed by 210 mg every 2 weeks.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved brodalumab, an interleukin-17 receptor A-antagonist, for treating adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) that addresses the “observed risk of suicidal ideation and behavior” in clinical trials, the agency announced on Feb. 16.

In the three pivotal phase III studies of 4,373 adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy, 83%-86% of those treated with brodalumab achieved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) scores at 12 weeks of treatment, compared with 3%-8% of those on placebo. In addition, 37%-44% of those on brodalumab achieved PASI 100 scores, compared with 1% or fewer of those on placebo. In the psoriasis clinical trials, suicidal ideation and behavior, which included four completed suicides, occurred in patients treated with brodalumab, according to the prescribing information

In the statement, the FDA points out that “a causal association between treatment with Siliq and increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior has not been established,” but that “suicidal ideation and behavior, including completed suicides, have occurred in patients treated with Siliq during clinical trials. Siliq users with a history of suicidality or depression had an increased incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior, compared to users without this history.”

At a meeting in July 2016, the FDA’s Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 18-0 in favor of approving brodalumab, with the majority (14) recommending risk management options beyond labeling to address these concerns.

Elements of the REMS include requirements for prescribers, pharmacy certification, and a medication guide for patients with information about the risks of suicidal ideation and behavior. Prescribers are required to counsel patients about this risk, and patients are required to sign a “Patient-Prescriber Agreement Form and be made aware of the need to seek medical attention should they experience new or worsening suicidal thoughts or behavior, feelings of depression, anxiety or other mood changes,” the FDA said. The prescribing information also includes a boxed warning about suicidal ideation and behavior.

The most common adverse events associated with brodalumab, the FDA statement noted, include arthralgia, headache, fatigue, diarrhea, oropharyngeal pain, nausea, myalgia, injection site reactions, neutropenia, and fungal infections. The recommended dose of brodalumab is 210 mg, administered subcutaneously, at weeks 0, 1, and 2, followed by 210 mg every 2 weeks.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved brodalumab, an interleukin-17 receptor A-antagonist, for treating adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) that addresses the “observed risk of suicidal ideation and behavior” in clinical trials, the agency announced on Feb. 16.

In the three pivotal phase III studies of 4,373 adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy, 83%-86% of those treated with brodalumab achieved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) scores at 12 weeks of treatment, compared with 3%-8% of those on placebo. In addition, 37%-44% of those on brodalumab achieved PASI 100 scores, compared with 1% or fewer of those on placebo. In the psoriasis clinical trials, suicidal ideation and behavior, which included four completed suicides, occurred in patients treated with brodalumab, according to the prescribing information

In the statement, the FDA points out that “a causal association between treatment with Siliq and increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior has not been established,” but that “suicidal ideation and behavior, including completed suicides, have occurred in patients treated with Siliq during clinical trials. Siliq users with a history of suicidality or depression had an increased incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior, compared to users without this history.”

At a meeting in July 2016, the FDA’s Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 18-0 in favor of approving brodalumab, with the majority (14) recommending risk management options beyond labeling to address these concerns.

Elements of the REMS include requirements for prescribers, pharmacy certification, and a medication guide for patients with information about the risks of suicidal ideation and behavior. Prescribers are required to counsel patients about this risk, and patients are required to sign a “Patient-Prescriber Agreement Form and be made aware of the need to seek medical attention should they experience new or worsening suicidal thoughts or behavior, feelings of depression, anxiety or other mood changes,” the FDA said. The prescribing information also includes a boxed warning about suicidal ideation and behavior.

The most common adverse events associated with brodalumab, the FDA statement noted, include arthralgia, headache, fatigue, diarrhea, oropharyngeal pain, nausea, myalgia, injection site reactions, neutropenia, and fungal infections. The recommended dose of brodalumab is 210 mg, administered subcutaneously, at weeks 0, 1, and 2, followed by 210 mg every 2 weeks.

Subcutaneous high-dose methotrexate controls psoriasis

Subcutaneous high-dose methotrexate can be safely initiated in people with moderate to severe psoriasis, and produces a rapid and sustained response, researchers found.

Although methotrexate is a first-line agent in moderate to severe psoriasis, and is considerably cheaper than biological agents, much remains unknown about its ideal dosage and route of administration.

Authors of a 2016 systematic review noted that, despite the fact that methotrexate has been used for more than 50 years in psoriasis, high-quality trial evidence remains wanting (PLoS One 2016 May 11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153740). Recent, well-designed trials have compared methotrexate to biological drugs used in psoriasis rather than placebo. These studies also have used oral formulations of methotrexate, in a range of starting doses as low as 5 mg, rather than subcutaneous formulations.

In their 52-week, multicenter trial conducted across 13 study sites in Europe, Dr. Warren and his colleagues randomized 120 patients to subcutaneous methotrexate at a dose of 17.5 mg/week (n = 91) or sham injections (n = 29) for 16 weeks. Patients in the intervention arm who did not achieve at least 50% improvement on the baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score at 8 weeks were increased to 22.5 mg methotrexate per week; 31% received this dose increase.

The study’s primary endpoint was reduction of the PASI score by 75% or more at 16 weeks, which 41% of the intervention arm achieved, compared with 10% of patients in the placebo arm (relative risk 3.93, P = .0026). After 16 weeks, all patients in the cohort were converted to open-label methotrexate for the remainder of the trial, following the same dosing schedule of between 17.5 and 22.5 mg, depending on response at 8 weeks after initiation.

At week 52, PASI 75 response rates were 45% in the methotrexate-methotrexate group and 34% in the placebo-methotrexate group. This compared favorably, the researchers wrote, with a previous study in which the PASI 75 response rate at week 52 was 24% with oral methotrexate at doses of up to 25 mg per week.

No serious adverse events were associated with methotrexate, although gastrointestinal problems (mostly nausea) and elevated liver enzymes were more common in patients receiving the treatment.

“Our findings encourage the use of subcutaneous methotrexate for treatment of psoriasis, and suggest long-term clinical outcomes better than previously reported for oral administration, although final confirmation will be needed in a direct head-to-head trial of subcutaneous versus oral dosing. Our findings might also help to guide future recommendations for the optimum dosing of methotrexate,” the investigators wrote.

Medac Pharma funded the study. Dr. Warren and six of his coauthors disclosed financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical firms, including the study sponsor, while three coauthors declared no financial conflicts of interest.

The results from this study compare favorably with those of a previous 52-week study of oral methotrexate in this population, suggesting that subcutaneous administration is superior to oral administration in the management of psoriasis. However, response rates for methotrexate are still lower than those reported with biological therapy, especially with infliximab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and, more recently, the anti-interleukin-17 drugs secukinumab and ixekizumab.

The question that remains is whether methotrexate should remain the first-line systemic therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis. Because we now know that psoriasis is not just skin deep, and that many of the comorbidities – including psoriatic arthritis, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular events, in addition to premature death – are related to the extent of skin involvement, perhaps drugs that effectively control inflammation should be used initially. This approach could be addressed only via long-term observations of prospective studies of patients treated with methotrexate, compared with those treated with biological therapy, with collection of information not only about clinical improvement of skin disease, but also about comorbidities.

Dafna D. Gladman, MD, is director of the psoriatic arthritis program at the Centre for Prognosis Studies in The Rheumatic Diseases at Toronto Western Hospital. This comment was excerpted and modified from an editorial (Lancet. 2017;389[10068]:482-3). that accompanied the study by Warren et al. Dr. Gladman disclosed financial relationships, mostly grants and fees related to clinical trials, with several pharmaceutical manufacturers.

The results from this study compare favorably with those of a previous 52-week study of oral methotrexate in this population, suggesting that subcutaneous administration is superior to oral administration in the management of psoriasis. However, response rates for methotrexate are still lower than those reported with biological therapy, especially with infliximab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and, more recently, the anti-interleukin-17 drugs secukinumab and ixekizumab.

The question that remains is whether methotrexate should remain the first-line systemic therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis. Because we now know that psoriasis is not just skin deep, and that many of the comorbidities – including psoriatic arthritis, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular events, in addition to premature death – are related to the extent of skin involvement, perhaps drugs that effectively control inflammation should be used initially. This approach could be addressed only via long-term observations of prospective studies of patients treated with methotrexate, compared with those treated with biological therapy, with collection of information not only about clinical improvement of skin disease, but also about comorbidities.

Dafna D. Gladman, MD, is director of the psoriatic arthritis program at the Centre for Prognosis Studies in The Rheumatic Diseases at Toronto Western Hospital. This comment was excerpted and modified from an editorial (Lancet. 2017;389[10068]:482-3). that accompanied the study by Warren et al. Dr. Gladman disclosed financial relationships, mostly grants and fees related to clinical trials, with several pharmaceutical manufacturers.

The results from this study compare favorably with those of a previous 52-week study of oral methotrexate in this population, suggesting that subcutaneous administration is superior to oral administration in the management of psoriasis. However, response rates for methotrexate are still lower than those reported with biological therapy, especially with infliximab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and, more recently, the anti-interleukin-17 drugs secukinumab and ixekizumab.

The question that remains is whether methotrexate should remain the first-line systemic therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis. Because we now know that psoriasis is not just skin deep, and that many of the comorbidities – including psoriatic arthritis, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular events, in addition to premature death – are related to the extent of skin involvement, perhaps drugs that effectively control inflammation should be used initially. This approach could be addressed only via long-term observations of prospective studies of patients treated with methotrexate, compared with those treated with biological therapy, with collection of information not only about clinical improvement of skin disease, but also about comorbidities.

Dafna D. Gladman, MD, is director of the psoriatic arthritis program at the Centre for Prognosis Studies in The Rheumatic Diseases at Toronto Western Hospital. This comment was excerpted and modified from an editorial (Lancet. 2017;389[10068]:482-3). that accompanied the study by Warren et al. Dr. Gladman disclosed financial relationships, mostly grants and fees related to clinical trials, with several pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Subcutaneous high-dose methotrexate can be safely initiated in people with moderate to severe psoriasis, and produces a rapid and sustained response, researchers found.

Although methotrexate is a first-line agent in moderate to severe psoriasis, and is considerably cheaper than biological agents, much remains unknown about its ideal dosage and route of administration.

Authors of a 2016 systematic review noted that, despite the fact that methotrexate has been used for more than 50 years in psoriasis, high-quality trial evidence remains wanting (PLoS One 2016 May 11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153740). Recent, well-designed trials have compared methotrexate to biological drugs used in psoriasis rather than placebo. These studies also have used oral formulations of methotrexate, in a range of starting doses as low as 5 mg, rather than subcutaneous formulations.

In their 52-week, multicenter trial conducted across 13 study sites in Europe, Dr. Warren and his colleagues randomized 120 patients to subcutaneous methotrexate at a dose of 17.5 mg/week (n = 91) or sham injections (n = 29) for 16 weeks. Patients in the intervention arm who did not achieve at least 50% improvement on the baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score at 8 weeks were increased to 22.5 mg methotrexate per week; 31% received this dose increase.

The study’s primary endpoint was reduction of the PASI score by 75% or more at 16 weeks, which 41% of the intervention arm achieved, compared with 10% of patients in the placebo arm (relative risk 3.93, P = .0026). After 16 weeks, all patients in the cohort were converted to open-label methotrexate for the remainder of the trial, following the same dosing schedule of between 17.5 and 22.5 mg, depending on response at 8 weeks after initiation.

At week 52, PASI 75 response rates were 45% in the methotrexate-methotrexate group and 34% in the placebo-methotrexate group. This compared favorably, the researchers wrote, with a previous study in which the PASI 75 response rate at week 52 was 24% with oral methotrexate at doses of up to 25 mg per week.

No serious adverse events were associated with methotrexate, although gastrointestinal problems (mostly nausea) and elevated liver enzymes were more common in patients receiving the treatment.

“Our findings encourage the use of subcutaneous methotrexate for treatment of psoriasis, and suggest long-term clinical outcomes better than previously reported for oral administration, although final confirmation will be needed in a direct head-to-head trial of subcutaneous versus oral dosing. Our findings might also help to guide future recommendations for the optimum dosing of methotrexate,” the investigators wrote.

Medac Pharma funded the study. Dr. Warren and six of his coauthors disclosed financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical firms, including the study sponsor, while three coauthors declared no financial conflicts of interest.

Subcutaneous high-dose methotrexate can be safely initiated in people with moderate to severe psoriasis, and produces a rapid and sustained response, researchers found.

Although methotrexate is a first-line agent in moderate to severe psoriasis, and is considerably cheaper than biological agents, much remains unknown about its ideal dosage and route of administration.

Authors of a 2016 systematic review noted that, despite the fact that methotrexate has been used for more than 50 years in psoriasis, high-quality trial evidence remains wanting (PLoS One 2016 May 11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153740). Recent, well-designed trials have compared methotrexate to biological drugs used in psoriasis rather than placebo. These studies also have used oral formulations of methotrexate, in a range of starting doses as low as 5 mg, rather than subcutaneous formulations.

In their 52-week, multicenter trial conducted across 13 study sites in Europe, Dr. Warren and his colleagues randomized 120 patients to subcutaneous methotrexate at a dose of 17.5 mg/week (n = 91) or sham injections (n = 29) for 16 weeks. Patients in the intervention arm who did not achieve at least 50% improvement on the baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score at 8 weeks were increased to 22.5 mg methotrexate per week; 31% received this dose increase.

The study’s primary endpoint was reduction of the PASI score by 75% or more at 16 weeks, which 41% of the intervention arm achieved, compared with 10% of patients in the placebo arm (relative risk 3.93, P = .0026). After 16 weeks, all patients in the cohort were converted to open-label methotrexate for the remainder of the trial, following the same dosing schedule of between 17.5 and 22.5 mg, depending on response at 8 weeks after initiation.

At week 52, PASI 75 response rates were 45% in the methotrexate-methotrexate group and 34% in the placebo-methotrexate group. This compared favorably, the researchers wrote, with a previous study in which the PASI 75 response rate at week 52 was 24% with oral methotrexate at doses of up to 25 mg per week.

No serious adverse events were associated with methotrexate, although gastrointestinal problems (mostly nausea) and elevated liver enzymes were more common in patients receiving the treatment.

“Our findings encourage the use of subcutaneous methotrexate for treatment of psoriasis, and suggest long-term clinical outcomes better than previously reported for oral administration, although final confirmation will be needed in a direct head-to-head trial of subcutaneous versus oral dosing. Our findings might also help to guide future recommendations for the optimum dosing of methotrexate,” the investigators wrote.

Medac Pharma funded the study. Dr. Warren and six of his coauthors disclosed financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical firms, including the study sponsor, while three coauthors declared no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 16 weeks, 41% of patients started on methotrexate achieved a 75% reduction in psoriasis severity scores, compared with 10% of patients in the placebo arm. At 1 year of treatment, 45% of patients saw this level of response.

Data source: A multisite, placebo-controlled trial randomizing 120 patients to subcutaneous methotrexate or placebo for 16 weeks, then converting all patients to open-label subcutaneous methotrexate through week 52.

Disclosures: Medac Pharma funded the study. Dr. Warren and six of his coauthors disclosed financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical firms, including the study sponsor, while three coauthors declared no financial conflicts of interest.

Perioperative infliximab does not increase serious infection risk

Administration of infliximab within 4 weeks of elective knee or hip arthroplasty did not have any significant effect on patients’ risk of serious infection after surgery, whereas the use of glucocorticoids increased that risk, in an analysis of a Medicare claims database.

“This increased risk with glucocorticoids has been suggested by previous studies [and] although this risk may be related in part to increased disease severity among glucocorticoid treated patients, a direct medication effect is likely. [These data suggest] that prolonged interruptions in infliximab therapy prior to surgery may be counterproductive if higher dose glucocorticoid therapy is used in substitution,” wrote the authors of the new study, led by Michael D. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. George and his colleagues examined data from the U.S. Medicare claims system on 4,288 elective knee or hip arthroplasties in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis who received infliximab within 6 months prior to the operation during 2007-2013 (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jan 27. doi: 10.1002/acr.23209).

The patients had to have received infliximab at least three times within a year of their procedure to establish that they were receiving stable therapy over a long-term period. The investigators also looked at oral prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone prescriptions and used data on average dosing to determine how much was administered to each subject.

“Although previous studies have treated TNF stopping vs. not stopping as a dichotomous exposure based on an arbitrary (and variable) stopping definition, in this study the primary analysis evaluated stop timing as a more general categorical exposure using 4-week intervals (half the standard rheumatoid arthritis dosing interval) to allow better assessment of the optimal stop timing,” the authors explained.

Stopping infliximab within 4 weeks of the operation did not significantly influence the rate of serious infection within 30 days (adjusted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.60-1.34) and neither did stopping within 4-8 weeks (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.62-1.36) when compared against stopping 8-12 weeks before surgery. Of the 4,288 arthroplasties, 270 serious infections (6.3%) occurred within 30 days of the operation.

There also was no significant difference between stopping within 4 weeks and 8-12 weeks in the rate of prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the operation (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.52-1.87). Overall, prosthetic joint infection occurred 2.9 times per 100 person-years.

However, glucocorticoid doses of more than 10 mg per day were risky. The odds for a serious infection within 30 days after surgery more than doubled with that level of use (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.30-3.40), while the risk for a prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the surgery also rose significantly (HR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.30-5.60).

“This is a very well done paper that adds important observational data to our understanding of perioperative medication risk,” Dr. Goodman said.

But the study results will not, at least initially, bring about any changes to the proposed guidelines for perioperative management of patients taking antirheumatic drugs that were described at the 2016 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, she said.

“We were aware of the abstract, which was also presented at the ACR last fall at the time the current perioperative medication management guidelines were presented, and it won’t change guidelines at this point,” said Dr. Goodman, who is one of the lead authors of the proposed guidelines. “[But] I think [the study] could provide important background information to use in a randomized clinical trial to compare infection on [and] not on TNF inhibitors.”

The proposed guidelines conditionally recommend that all biologics should be withheld prior to surgery in patients with inflammatory arthritis, that surgery should be planned for the end of the dosing cycle, and that current daily doses of glucocorticoids, rather than supraphysiologic doses, should be continued in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or inflammatory arthritis.

The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

Administration of infliximab within 4 weeks of elective knee or hip arthroplasty did not have any significant effect on patients’ risk of serious infection after surgery, whereas the use of glucocorticoids increased that risk, in an analysis of a Medicare claims database.

“This increased risk with glucocorticoids has been suggested by previous studies [and] although this risk may be related in part to increased disease severity among glucocorticoid treated patients, a direct medication effect is likely. [These data suggest] that prolonged interruptions in infliximab therapy prior to surgery may be counterproductive if higher dose glucocorticoid therapy is used in substitution,” wrote the authors of the new study, led by Michael D. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. George and his colleagues examined data from the U.S. Medicare claims system on 4,288 elective knee or hip arthroplasties in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis who received infliximab within 6 months prior to the operation during 2007-2013 (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jan 27. doi: 10.1002/acr.23209).

The patients had to have received infliximab at least three times within a year of their procedure to establish that they were receiving stable therapy over a long-term period. The investigators also looked at oral prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone prescriptions and used data on average dosing to determine how much was administered to each subject.

“Although previous studies have treated TNF stopping vs. not stopping as a dichotomous exposure based on an arbitrary (and variable) stopping definition, in this study the primary analysis evaluated stop timing as a more general categorical exposure using 4-week intervals (half the standard rheumatoid arthritis dosing interval) to allow better assessment of the optimal stop timing,” the authors explained.

Stopping infliximab within 4 weeks of the operation did not significantly influence the rate of serious infection within 30 days (adjusted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.60-1.34) and neither did stopping within 4-8 weeks (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.62-1.36) when compared against stopping 8-12 weeks before surgery. Of the 4,288 arthroplasties, 270 serious infections (6.3%) occurred within 30 days of the operation.

There also was no significant difference between stopping within 4 weeks and 8-12 weeks in the rate of prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the operation (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.52-1.87). Overall, prosthetic joint infection occurred 2.9 times per 100 person-years.

However, glucocorticoid doses of more than 10 mg per day were risky. The odds for a serious infection within 30 days after surgery more than doubled with that level of use (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.30-3.40), while the risk for a prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the surgery also rose significantly (HR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.30-5.60).

“This is a very well done paper that adds important observational data to our understanding of perioperative medication risk,” Dr. Goodman said.

But the study results will not, at least initially, bring about any changes to the proposed guidelines for perioperative management of patients taking antirheumatic drugs that were described at the 2016 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, she said.

“We were aware of the abstract, which was also presented at the ACR last fall at the time the current perioperative medication management guidelines were presented, and it won’t change guidelines at this point,” said Dr. Goodman, who is one of the lead authors of the proposed guidelines. “[But] I think [the study] could provide important background information to use in a randomized clinical trial to compare infection on [and] not on TNF inhibitors.”

The proposed guidelines conditionally recommend that all biologics should be withheld prior to surgery in patients with inflammatory arthritis, that surgery should be planned for the end of the dosing cycle, and that current daily doses of glucocorticoids, rather than supraphysiologic doses, should be continued in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or inflammatory arthritis.

The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

Administration of infliximab within 4 weeks of elective knee or hip arthroplasty did not have any significant effect on patients’ risk of serious infection after surgery, whereas the use of glucocorticoids increased that risk, in an analysis of a Medicare claims database.

“This increased risk with glucocorticoids has been suggested by previous studies [and] although this risk may be related in part to increased disease severity among glucocorticoid treated patients, a direct medication effect is likely. [These data suggest] that prolonged interruptions in infliximab therapy prior to surgery may be counterproductive if higher dose glucocorticoid therapy is used in substitution,” wrote the authors of the new study, led by Michael D. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. George and his colleagues examined data from the U.S. Medicare claims system on 4,288 elective knee or hip arthroplasties in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis who received infliximab within 6 months prior to the operation during 2007-2013 (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jan 27. doi: 10.1002/acr.23209).

The patients had to have received infliximab at least three times within a year of their procedure to establish that they were receiving stable therapy over a long-term period. The investigators also looked at oral prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone prescriptions and used data on average dosing to determine how much was administered to each subject.

“Although previous studies have treated TNF stopping vs. not stopping as a dichotomous exposure based on an arbitrary (and variable) stopping definition, in this study the primary analysis evaluated stop timing as a more general categorical exposure using 4-week intervals (half the standard rheumatoid arthritis dosing interval) to allow better assessment of the optimal stop timing,” the authors explained.

Stopping infliximab within 4 weeks of the operation did not significantly influence the rate of serious infection within 30 days (adjusted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.60-1.34) and neither did stopping within 4-8 weeks (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.62-1.36) when compared against stopping 8-12 weeks before surgery. Of the 4,288 arthroplasties, 270 serious infections (6.3%) occurred within 30 days of the operation.

There also was no significant difference between stopping within 4 weeks and 8-12 weeks in the rate of prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the operation (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.52-1.87). Overall, prosthetic joint infection occurred 2.9 times per 100 person-years.

However, glucocorticoid doses of more than 10 mg per day were risky. The odds for a serious infection within 30 days after surgery more than doubled with that level of use (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.30-3.40), while the risk for a prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the surgery also rose significantly (HR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.30-5.60).

“This is a very well done paper that adds important observational data to our understanding of perioperative medication risk,” Dr. Goodman said.

But the study results will not, at least initially, bring about any changes to the proposed guidelines for perioperative management of patients taking antirheumatic drugs that were described at the 2016 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, she said.

“We were aware of the abstract, which was also presented at the ACR last fall at the time the current perioperative medication management guidelines were presented, and it won’t change guidelines at this point,” said Dr. Goodman, who is one of the lead authors of the proposed guidelines. “[But] I think [the study] could provide important background information to use in a randomized clinical trial to compare infection on [and] not on TNF inhibitors.”

The proposed guidelines conditionally recommend that all biologics should be withheld prior to surgery in patients with inflammatory arthritis, that surgery should be planned for the end of the dosing cycle, and that current daily doses of glucocorticoids, rather than supraphysiologic doses, should be continued in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or inflammatory arthritis.

The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Subjects on glucocorticoids had an OR of 2.11 (95% CI 1.30-3.40) for serious infection within 30 days and an HR of 2.70 (95% CI 1.30-5.60) for prosthetic joint infection within 1 year.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 4,288 elective knee and hip arthroplasties in Medicare patients with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis during 2007-2013.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

Psoriatic Arthritis Treatment: The Dermatologist’s Role

Resolution of Psoriatic Lesions on the Gingiva and Hard Palate Following Administration of Adalimumab for Cutaneous Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

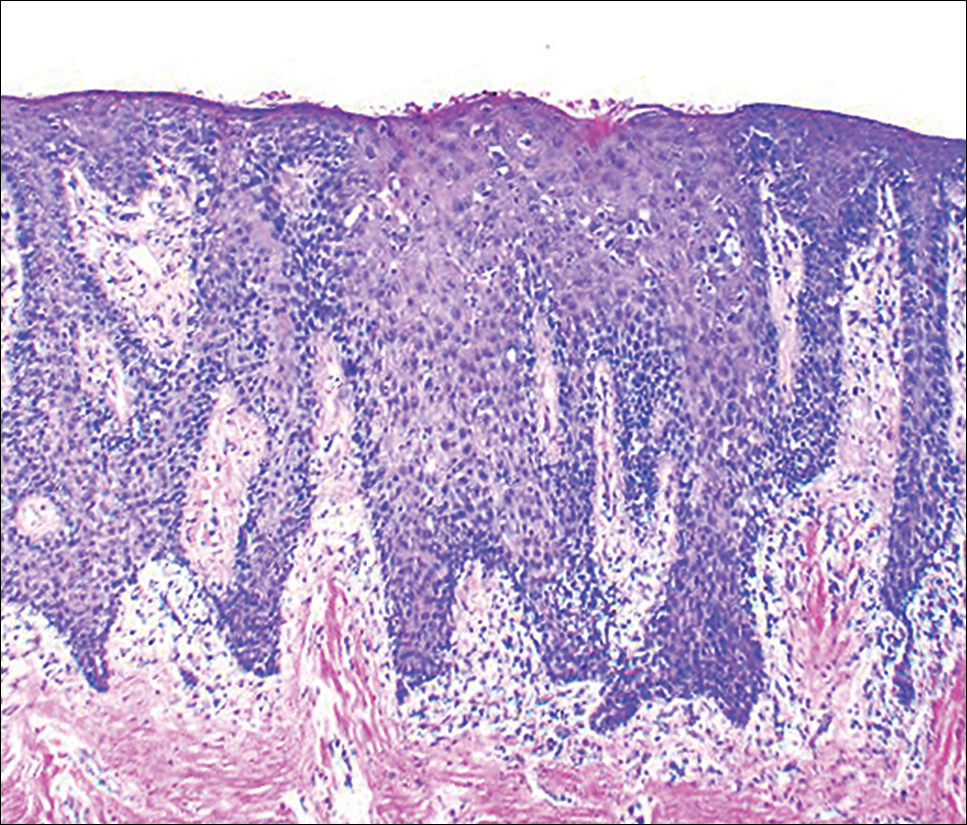

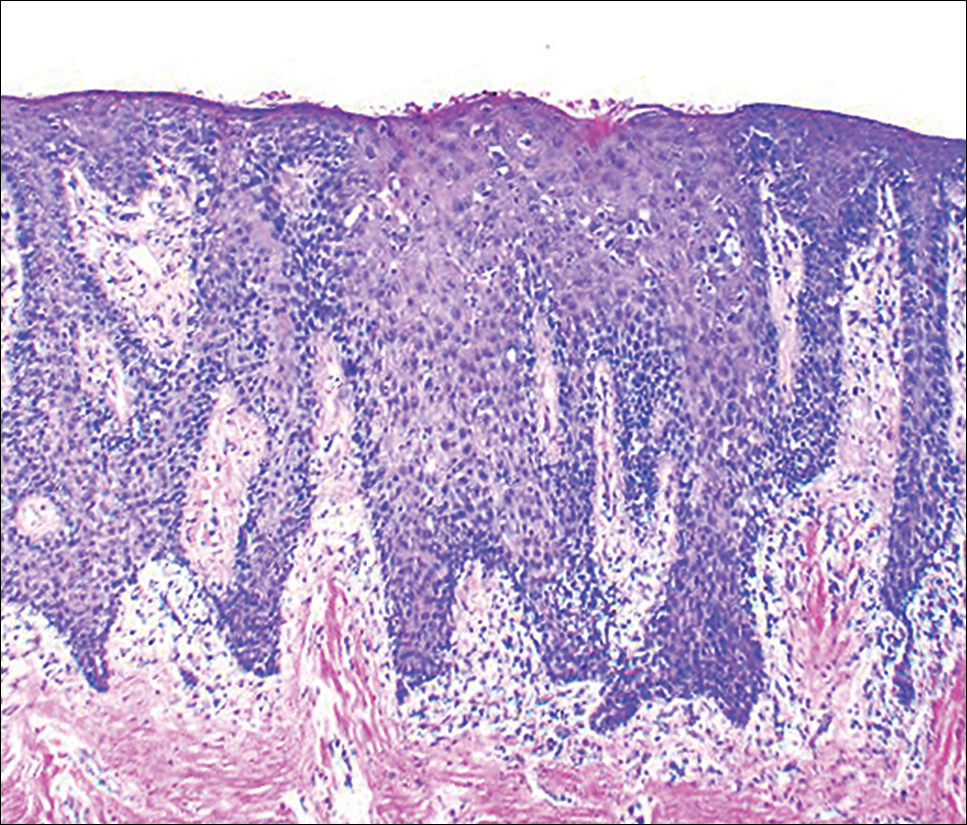

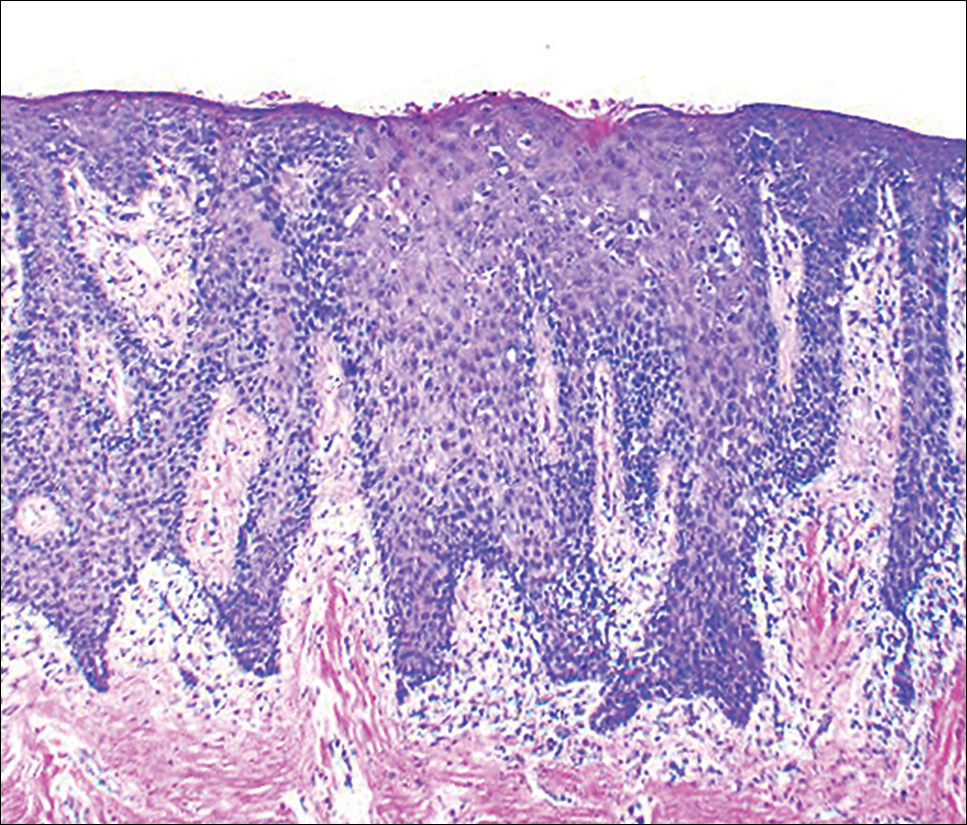

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment

Psoriasis of the oral cavity is rare and typically occurs on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, lip, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.2,7 The lesions are almost always concordant with cutaneous psoriasis, and only sporadic examples exclusive to the oral mucosa have been recognized.7,10 Gingival psoriasis usually is described as intensely erythematous and occasionally laced with white scaly streaks involving the marginal gingiva that extend toward the mucogingival junction. In general, the erythematous presentation of gingival psoriasis may not be commensurate with the degree of inflammation induced by dental plaque-based periodontal disease. Doben11 documented gingival psoriasis as appearing “deeply stippled and grainy” and commented that the tissue was “friable” and incapable of maintaining a “clean incision line” during periodontal surgery. In our patient, the gingiva also had exhibited a granular surface. Patients with oral psoriasis often report soreness or a burning sensation of the gingiva, which may easily bleed on manipulation or brushing the teeth, whereas other patients are asymptomatic,12 as in our case. Psoriasis of the hard palate usually presents as multiple painless red macules. Unlike cutaneous psoriasis, oral lesions rarely evoke pruritus.10 Histopathologically, oral psoriasis bears a striking resemblance to its cutaneous counterpart. The epithelium has a pronounced parakeratinized surface with elongated rete ridges and aggregations of Munro microabscesses. The connective tissue often is composed of dilated capillaries that closely approximate the epithelium as well as infiltrations of lymphocytes. Specimens suspected for oral psoriasis should routinely be stained with periodic acid–Schiff to rule out candidiasis coinfection. The microscopic findings of our patient were congruent with prior reports of oral psoriasis.7,10-12 Some clinicians have questioned if psoriasis can actually occur in the oral cavity, but most authorities in the field have recognized its true existence, as evidenced by various shared HLA antigens, specifically HLA-Cw.13

Another group of oral lesions collectively referred to as psoriasiform mucositis, notably geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans) and its extraglossal variant geographic stomatitis,14,15 have histopathologic features and HLAs similar to those seen in cutaneous psoriasis.13 Interestingly, geographic tongue has been found in 3.8% to 9.1% of cohorts with cutaneous psoriasis,8,9 but in the extant population, the vast majority of patients with oral psoriasiform mucositis do not have cutaneous psoriasis. Other differential diagnoses for gingival psoriasis are lichen planus, human immunodeficiency virus–associated periodontitis, desquamative gingivitis, plasma cell gingivitis, erythematous candidiasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, orofacial granulomatosis, localized juvenile spongiotic gingivitis hyperplasia, and primary gingivostomatitis.

Management of gingival psoriasis focuses on strategies to reduce inflammation and discomfort and measures to achieve meticulous oral plaque control. Judicious efforts should be exercised to avoid oral soft-tissue injury when performing periodontal scaling, although it has not been established whether gingival psoriasis is associated with the Köbner phenomenon, as seen with cutaneous lesions. Adjunctive measures employed for symptomatic patients have involved the use of corticosteroids (eg, lesional injection, oral rinse, systemic) and oral rinses with retinoic acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, and warm saline.7,10,16 Prolonged utilization of corticosteroids, however, may necessitate supplemental administration of antifungal agents.

This case report represents a rare documentation of a successful outcome of gingival and palatal psoriasis subsequent to the reinstitution of adalimumab solely for treatment of recurrent cutaneous disease. There likely is a pharmacologic basis for the amelioration of oral psoriasis in our patient. Adalimumab is a bivalent IgG monoclonal antibody that binds to activated dermal dendritic cell receptors of tumor necrosis factor α, thereby attenuating a cytokine-derived inflammatory response and apoptosis.17 In fact, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed notable reductions in both gingival inflammation and bleeding following a 3-month regimen of adalimumab.18

Conclusion

Practitioners should be aware of the phenotypic overlap of cutaneous and oral psoriasis, particularly involving the gingiva and palate. It is recommended that psoriasis patients routinely receive a dental prophylaxis and engage in oral hygiene efforts to reduce the presence of oral microbiota. Furthermore, it is emphasized that psoriatic patients who maintain an atypical erythematous presentation on the oral mucosa undergo a biopsy for identification of the lesions and correlation with disease dissemination. Prospective studies are needed to characterize the clinical courses of oral psoriasis, ascertain their correlative behavior with cutaneous flares, and determine if lesional improvement can be achieved with the use of biologic agents or other therapeutic modalities.

- Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61-78.

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61-67.

- Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1345-1350.

- Lazaridou E, Tsikrikoni A, Fotiadou C, et al. Association of chronic plaque psoriasis and severe periodontitis: a hospital based case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:967-972.

- Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Slevolden EM, Hansen BF, et al. Association between moderate to severe psoriasis and periodontitis in a Scandinavian population. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:139.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE. Erythema migrans—a psoriasiform lesion of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:1067-1070.

- Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, et al. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113-115.

- Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, et al. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of oral mucosa diseases Italian group (GIPMO). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:78-79.

- Brayshaw HA, Orban B. Psoriasis gingivae. J Periodontol. 1953;24:156-160.

- Doben DI. Psoriasis of the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1976;47:38-40.

- Mattsson U, Warfvinge G, Jontell M. Oral psoriasis—a diagnostic dilemma: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:e183-e189.

- Dermatologic diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:792-794.

- Brooks JK, Balciunas BA. Geographic stomatitis: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:421-424.

- Brooks JK, Nikitakis NG. Multiple mucosal lesions. erythema migrans. Gen Dent. 2007;55:160, 163.

- Ulmansky M, Michelle R, Azaz B. Oral psoriasis: report of six new cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:42-45.

- Lis K, Kuzawinska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—state of knowledge. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175-1185.

- Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1480-1488.

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment