User login

Evaluation of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria for the Nonarthroplasty Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis in Veterans

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) affects almost 9.3 million adults in the US and accounts for $27 billion in annual health care expenses.1,2 Due to the increasing cost of health care and an aging population, there has been renewed interest in establishing criteria for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA.

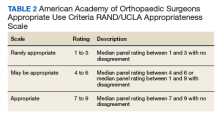

In 2013, using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness method, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an appropriate use criteria (AUC) for nonarthroplasty management of primary OA of the knee, based on orthopaedic literature and expert opinion.3 Interventions such as activity modification, weight loss, prescribed physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tramadol, prescribed oral or transcutaneous opioids, acetaminophen, intra-articular corticosteroids, hinged or unloading knee braces, arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal, and realignment osteotomy were assessed. An algorithm was developed for 576 patients scenarios that incorporated patient-specific, prognostic/predictor variables to assign designations of “appropriate,” “may be appropriate,” or “rarely appropriate,” to treatment interventions.4,5 An online version of the algorithm (orthoguidelines.org) is available for physicians and surgeons to judge appropriateness of nonarthroplasty treatments; however, it is not intended to mandate candidacy for treatment or intervention.

Clinical evaluation of the AAOS AUC is necessary to determine how treatment recommendations correlate with current practice. A recent examination of the AAOS Appropriateness System for Surgical Management of Knee OA found that prognostic/predictor variables, such as patient age, OA severity, and pattern of knee OA involvement were more heavily weighted when determining arthroplasty appropriateness than was pain severity or functional loss.6 Furthermore, non-AAOS AUC prognostic/predictor variables, such as race and gender, have been linked to disparities in utilization of knee OA interventions.7-9 Such disparities can be costly not just from a patient perceptive, but also employer and societal perspectives.10

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system represents a model of equal-access-to care system in the US that is ideal for examination of issues about health care utilization and any disparities within the AAOS AUC model and has previously been used to assess utilization of total knee arthroplasty.9 The aim of this study was to characterize utilization of the AAOS AUC for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA in a VA patient population. We asked the following questions: (1) What variables are predictive of receiving a greater number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments? (2) What variables are predictive of receiving “rarely appropriate” AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatment? (3) What factors are predictive of duration of nonarthroplasty care until total knee arthroplasty (TKA)?

Methods

The institutional review board at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio approved a retrospective chart review of nonarthroplasty treatments utilized by patients presenting to its orthopaedic section who subsequently underwent knee arthroplasty between 2013 and 2016. Eligibility criteria included patients aged ≥ 30 years with a diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral primary knee OA. Patients with posttraumatic OA, inflammatory arthritis, and a history of infectious arthritis or Charcot arthropathy of the knee were excluded. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 or a hemoglobin A1c > 8.0 at presentation were excluded as nonarthroplasty care was the recommended course of treatment above these thresholds.

Data collected included race, gender, duration of nonarthroplasty treatment, BMI, and Kellgren-Lawrence classification of knee OA at time of presentation for symptomatic knee OA.11 All AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized prior to arthroplasty intervention also were recorded (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed with GraphPad Software Prism 7.0a (La Jolla, CA) and Mathworks MatLab R2016b software (Natick, MA). Univariate analysis with Student t tests with Welch corrections in the setting of unequal variance, Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests, and Fisher exact test were generated in the appropriate setting. Multivariable analyses also were conducted. For continuous outcomes, stepwise multiple linear regression was used to generate predictive models; for binary outcomes, binomial logistic regression was used.

Factors analyzed in regression modeling for the total number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized and the likelihood of receiving a rarely appropriate treatment included gender, race, function-limiting pain, range of motion (ROM), ligamentous instability, arthritis pattern, limb alignment, mechanical symptoms, BMI, age, and Kellgren-Lawrence grade. Factors analyzed in timing of TKA included the above variables plus the total number of AUC interventions, whether the patient received an inappropriate intervention, and average appropriateness of the interventions received. Residual analysis with Cook’s distance was used to identify outliers in regression. Observations with Cook’s distance > 3 times the mean Cook’s distance were identified as potential outliers, and models were adjusted accordingly. All statistical analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set to P ≤ .05 for all outputs.

Results

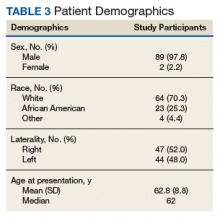

In the study, 97.8% of participants identified as male, and the mean age was 62.8 years (Table 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria Interventions

Patients received a mean of 5.2 AAOS AUC evaluated interventions before undergoing arthroplasty management at a mean of 32.3 months (range 2-181 months) from initial presentation. The majority of these interventions were classified as either appropriate or may be appropriate, according to the AUC definitions (95.1%). Self-management and physical therapy programs were widely utilized (100% and 90.1%, respectively), with all use of these interventions classified as appropriate.

Hinged or unloader knee braces were utilized in about half the study patients; this intervention was classified as rarely appropriate in 4.4% of these patients. Medical therapy was also widely used, with all use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and tramadol classified as appropriate or may be appropriate. Oral or transcutaneous opioid medications were prescribed in 14.3% of patients, with 92.3% of this use classified as rarely appropriate. Although the opioid medication prescribing provider was not specifically evaluated, there were no instances in which the orthopaedic service provided an oral or transcutaneous opioid prescriptions. Procedural interventions, with the exception of corticosteroid injections, were uncommon; no patient received realignment osteotomy, and only 12.1% of patients underwent arthroscopy. The use of arthroscopy was deemed rarely appropriate in 72.7% of these cases.

Factors Associated With AAOS AUC Intervention Use

There was no difference in the number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received based on BMI (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 5.2 [1.0] vs BMI ≥ 35, 5.3 [1.1], P = .49), age (mean [SD] aged < 60 years, 5.4 [1.0] vs aged ≥ 60 years, 5.1 [1.2], P = .23), or Kellgren-Lawrence arthritic grade (mean [SD] grade ≤ 2, 5.5 [1.0] vs grade > 2, 5.1 [1.1], P = .06). These variables also were not associated with receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 0.27 [0.5] vs BMI > 35, 0.2 [0.4], P = .81; aged > 60 years, 0.3 [0.5] vs aged < 60 years, 0.2 [0.4], P = .26; Kellgren-Lawrence grade < 2, 0.4 [0.6] vs grade > 2, 0.2 [0.4], P = .1).

Regression modeling to predict total number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received produced a significant model (R2 = 0.111, P = .006). The presence of ligamentous instability (β coefficient, -1.61) and the absence of mechanical symptoms (β coefficient, -0.67) were negative predictors of number of AUC interventions received. Variance inflation factors were 1.014 and 1.012, respectively. Likewise, regression modeling to identify factors predictive of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention also produced a significant model (pseudo R2= 0.06, P = .025), with lower Kellgren-Lawrence grade the only significant predictor of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (odds ratio [OR] 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42 -0.72, per unit increase).

Timing from presentation to arthroplasty intervention was also evaluated. Age was a negative predictor (β coefficient -1.61), while positive predictors were reduced ROM (β coefficient 15.72) and having more AUC interventions (β coefficient 7.31) (model R2= 0.29, P = < .001). Age was the most significant predictor. Variance inflations factors were 1.02, 1.01, and 1.03, respectively. Receiving a rarely appropriate intervention was not associated with TKA timing.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study examined the utilization of AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty interventions for symptomatic knee OA prior to TKA. The aims of this study were to validate the AAOS AUC in a clinical setting and identify predictors of AAOS AUC utilization. In particular, this study focused on the number of interventions utilized prior to knee arthroplasty, whether interventions receiving a designation of rarely appropriate were used, and the duration of nonarthroplasty treatment.

Patients with knee instability used fewer total AAOS AUC evaluated interventions prior to TKA. Subjective instability has been reported as high as 27% in patients with OA and has been associated with fear of falling, poor balance confidence, activity limitations, and lower Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function scores.12 However, it has not been found to correlate with knee laxity.13 Nevertheless, significant functional impairment with the risk of falling may reduce the number of nonarthroplasty interventions attempted. On the other hand, the presence of mechanical symptoms resulted in greater utilization of nonarthroplasty interventions. This is likely due to the greater utilization of arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal in this group of patients. Despite its inclusion as an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, arthroscopy remains a contentious treatment for symptomatic knee pain in the setting of OA.14,15

For every unit decrease in Kellgren-Lawrence OA grade, patients were 54% more likely to receive a rarely appropriate intervention prior to knee arthroplasty. This is supported by the recent literature examining the AAOS AUC for surgical management of knee OA. Riddle and colleagues developed a classification tree to determine the contributions of various prognostic variables in final classifications of the 864 clinical vignettes used to develop the appropriateness algorithm and found that OA severity was strongly favored, with only 4 of the 432 vignettes with severe knee OA judged as rarely appropriate for surgical intervention.6

Our findings, too, may be explained by an AAOS AUC system that too heavily weighs radiographic severity of knee OA, resulting in more frequent rarely appropriate interventions in patients with less severe arthritis, including nonarthroplasty treatments. It is likely that rarely appropriate interventions were attempted in this subset of our study cohort based on patient’s subjective symptoms and functional status, both of which have been shown to be discordant with radiographic severity of knee OA.16

Oral or transcutaneous prescribed opioid medications were the most frequent intervention that received a rarely appropriate designation. Patients with preoperative opioid use undergoing TKA have been shown to have a greater risk for postoperative complications and longer hospital stay, particularly those patients aged < 75 years. Younger age, use of more interventions, and decreased knee ROM at presentation were predictive of longer duration of nonarthroplasty treatment. The use of more AAOS AUC evaluated interventions in these patients suggests that the AAOS AUC model may effectively be used to manage symptomatic OA, increasing the time from presentation to knee arthroplasty.

Interestingly, the use of rarely appropriate interventions did not affect TKA timing, as would be expected in a clinically effective nonarthroplasty treatment model. The reasons for rarely appropriate nonsurgical interventions are complex and require further investigation. One possible explanation is that decreased ROM was a marker for mechanical symptoms that necessitated additional intervention in the form of knee arthroscopy, delaying time to TKA.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, the small sample size (N = 90) requires acknowledgment; however, this limitation reflects the difficulty in following patients for years prior to an operative intervention. Second, the study population consists of veterans using the VA system and may not be reflective of the general population, differing with respect to gender, racial, and socioeconomic factors. Nevertheless, studies examining TKA utilization found, aside from racial and ethnic variability, patient gender and age do not affect arthroplasty utilization rate in the VA system.17

Additional limitations stem from the retrospective nature of this study. While the Computerized Patient Record System and centralized care of the VA system allows for review of all physical therapy consultations, orthotic consultations, and medications within the VA system, any treatments and intervention delivered by non-VA providers were not captured. Furthermore, the ability to assess for confounding variables limiting the prescription of certain medications, such as chronic kidney disease with NSAIDs or liver disease with acetaminophen, was limited by our study design.

Although our study suffers from selection bias with respect to examination of nonarthroplasty treatment in patients who have ultimately undergone TKA, we feel that this subset of patients with symptomatic knee OA represents the majority of patients evaluated for knee OA by orthopaedic surgeons in the clinic setting. It should be noted that although realignment osteotomies were sometimes indicated as appropriate by AAOS AUC model in our study population, this intervention was never performed due to patient and surgeon preference. Additionally, although it is not an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, viscosupplementation was sporadically used during the study period; however, it is now off formulary at the investigation institution.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that patients without knee instability use more nonarthroplasty treatments over a longer period before TKA, and those patients with less severe knee OA are at risk of receiving an intervention judged to be rarely appropriate by the AAOS AUC. Such interventions do not affect timing of TKA. Nonarthroplasty care should be individualized to patients’ needs, and the decision to proceed with arthroplasty should be considered only after exhausting appropriate conservative measures. We recommend that providers use the AAOS AUC, especially when treating younger patients with less severe knee OA, particularly if considering opiate therapy or knee arthroscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Getty, MD, for his surgical care of some of the study patients. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio.

1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323-1330.

2. Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1113-1121; discussion 1121-1122.

3. Members of the Writing, Review, and Voting Panels of the AUC on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee, Sanders JO, Heggeness MH, Murray J, Pezold R, Donnelly P. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):1220-1221.

4. Sanders JO, Murray J, Gross L. Non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):256-260.

5. Yates AJ Jr, McGrory BJ, Starz TW, Vincent KR, McCardel B, Golightly YM. AAOS appropriate use criteria: optimizing the non-arthroplasty management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):261-267.

6. Riddle DL, Perera RA. Appropriateness and total knee arthroplasty: an examination of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons appropriateness rating system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(12):1994-1998.

7. Morgan RC Jr, Slover J. Breakout session: ethnic and racial disparities in joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1886-1890.

8. O’Connor MI, Hooten EG. Breakout session: gender disparities in knee osteoarthritis and TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1883-1885.

9. Ibrahim SA. Racial and ethnic disparities in hip and knee joint replacement: a review of research in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):S87-S94.

10. Karmarkar TD, Maurer A, Parks ML, et al. A fresh perspective on a familiar problem: examining disparities in knee osteoarthritis using a Markov model. Med Care. 2017;55(12):993-1000.

11. Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(8):1886-1893.

12. Nguyen U, Felson DT, Niu J, et al. The impact of knee instability with and without buckling on balance confidence, fear of falling and physical function: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(4):527-534.

13. Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1506-1516.

14. Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005118.

15. Lamplot JD, Brophy RH. The role for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in knees with degenerative changes: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(7):934-938.

16. Whittle R, Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G. Average symptom trajectories following incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000281.

17. Jones A, Kwoh CK, Kelley ME, Ibrahim SA. Racial disparity in knee arthroplasty utilization in the Veterans Health Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):979-981.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) affects almost 9.3 million adults in the US and accounts for $27 billion in annual health care expenses.1,2 Due to the increasing cost of health care and an aging population, there has been renewed interest in establishing criteria for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA.

In 2013, using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness method, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an appropriate use criteria (AUC) for nonarthroplasty management of primary OA of the knee, based on orthopaedic literature and expert opinion.3 Interventions such as activity modification, weight loss, prescribed physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tramadol, prescribed oral or transcutaneous opioids, acetaminophen, intra-articular corticosteroids, hinged or unloading knee braces, arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal, and realignment osteotomy were assessed. An algorithm was developed for 576 patients scenarios that incorporated patient-specific, prognostic/predictor variables to assign designations of “appropriate,” “may be appropriate,” or “rarely appropriate,” to treatment interventions.4,5 An online version of the algorithm (orthoguidelines.org) is available for physicians and surgeons to judge appropriateness of nonarthroplasty treatments; however, it is not intended to mandate candidacy for treatment or intervention.

Clinical evaluation of the AAOS AUC is necessary to determine how treatment recommendations correlate with current practice. A recent examination of the AAOS Appropriateness System for Surgical Management of Knee OA found that prognostic/predictor variables, such as patient age, OA severity, and pattern of knee OA involvement were more heavily weighted when determining arthroplasty appropriateness than was pain severity or functional loss.6 Furthermore, non-AAOS AUC prognostic/predictor variables, such as race and gender, have been linked to disparities in utilization of knee OA interventions.7-9 Such disparities can be costly not just from a patient perceptive, but also employer and societal perspectives.10

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system represents a model of equal-access-to care system in the US that is ideal for examination of issues about health care utilization and any disparities within the AAOS AUC model and has previously been used to assess utilization of total knee arthroplasty.9 The aim of this study was to characterize utilization of the AAOS AUC for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA in a VA patient population. We asked the following questions: (1) What variables are predictive of receiving a greater number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments? (2) What variables are predictive of receiving “rarely appropriate” AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatment? (3) What factors are predictive of duration of nonarthroplasty care until total knee arthroplasty (TKA)?

Methods

The institutional review board at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio approved a retrospective chart review of nonarthroplasty treatments utilized by patients presenting to its orthopaedic section who subsequently underwent knee arthroplasty between 2013 and 2016. Eligibility criteria included patients aged ≥ 30 years with a diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral primary knee OA. Patients with posttraumatic OA, inflammatory arthritis, and a history of infectious arthritis or Charcot arthropathy of the knee were excluded. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 or a hemoglobin A1c > 8.0 at presentation were excluded as nonarthroplasty care was the recommended course of treatment above these thresholds.

Data collected included race, gender, duration of nonarthroplasty treatment, BMI, and Kellgren-Lawrence classification of knee OA at time of presentation for symptomatic knee OA.11 All AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized prior to arthroplasty intervention also were recorded (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed with GraphPad Software Prism 7.0a (La Jolla, CA) and Mathworks MatLab R2016b software (Natick, MA). Univariate analysis with Student t tests with Welch corrections in the setting of unequal variance, Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests, and Fisher exact test were generated in the appropriate setting. Multivariable analyses also were conducted. For continuous outcomes, stepwise multiple linear regression was used to generate predictive models; for binary outcomes, binomial logistic regression was used.

Factors analyzed in regression modeling for the total number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized and the likelihood of receiving a rarely appropriate treatment included gender, race, function-limiting pain, range of motion (ROM), ligamentous instability, arthritis pattern, limb alignment, mechanical symptoms, BMI, age, and Kellgren-Lawrence grade. Factors analyzed in timing of TKA included the above variables plus the total number of AUC interventions, whether the patient received an inappropriate intervention, and average appropriateness of the interventions received. Residual analysis with Cook’s distance was used to identify outliers in regression. Observations with Cook’s distance > 3 times the mean Cook’s distance were identified as potential outliers, and models were adjusted accordingly. All statistical analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set to P ≤ .05 for all outputs.

Results

In the study, 97.8% of participants identified as male, and the mean age was 62.8 years (Table 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria Interventions

Patients received a mean of 5.2 AAOS AUC evaluated interventions before undergoing arthroplasty management at a mean of 32.3 months (range 2-181 months) from initial presentation. The majority of these interventions were classified as either appropriate or may be appropriate, according to the AUC definitions (95.1%). Self-management and physical therapy programs were widely utilized (100% and 90.1%, respectively), with all use of these interventions classified as appropriate.

Hinged or unloader knee braces were utilized in about half the study patients; this intervention was classified as rarely appropriate in 4.4% of these patients. Medical therapy was also widely used, with all use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and tramadol classified as appropriate or may be appropriate. Oral or transcutaneous opioid medications were prescribed in 14.3% of patients, with 92.3% of this use classified as rarely appropriate. Although the opioid medication prescribing provider was not specifically evaluated, there were no instances in which the orthopaedic service provided an oral or transcutaneous opioid prescriptions. Procedural interventions, with the exception of corticosteroid injections, were uncommon; no patient received realignment osteotomy, and only 12.1% of patients underwent arthroscopy. The use of arthroscopy was deemed rarely appropriate in 72.7% of these cases.

Factors Associated With AAOS AUC Intervention Use

There was no difference in the number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received based on BMI (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 5.2 [1.0] vs BMI ≥ 35, 5.3 [1.1], P = .49), age (mean [SD] aged < 60 years, 5.4 [1.0] vs aged ≥ 60 years, 5.1 [1.2], P = .23), or Kellgren-Lawrence arthritic grade (mean [SD] grade ≤ 2, 5.5 [1.0] vs grade > 2, 5.1 [1.1], P = .06). These variables also were not associated with receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 0.27 [0.5] vs BMI > 35, 0.2 [0.4], P = .81; aged > 60 years, 0.3 [0.5] vs aged < 60 years, 0.2 [0.4], P = .26; Kellgren-Lawrence grade < 2, 0.4 [0.6] vs grade > 2, 0.2 [0.4], P = .1).

Regression modeling to predict total number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received produced a significant model (R2 = 0.111, P = .006). The presence of ligamentous instability (β coefficient, -1.61) and the absence of mechanical symptoms (β coefficient, -0.67) were negative predictors of number of AUC interventions received. Variance inflation factors were 1.014 and 1.012, respectively. Likewise, regression modeling to identify factors predictive of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention also produced a significant model (pseudo R2= 0.06, P = .025), with lower Kellgren-Lawrence grade the only significant predictor of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (odds ratio [OR] 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42 -0.72, per unit increase).

Timing from presentation to arthroplasty intervention was also evaluated. Age was a negative predictor (β coefficient -1.61), while positive predictors were reduced ROM (β coefficient 15.72) and having more AUC interventions (β coefficient 7.31) (model R2= 0.29, P = < .001). Age was the most significant predictor. Variance inflations factors were 1.02, 1.01, and 1.03, respectively. Receiving a rarely appropriate intervention was not associated with TKA timing.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study examined the utilization of AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty interventions for symptomatic knee OA prior to TKA. The aims of this study were to validate the AAOS AUC in a clinical setting and identify predictors of AAOS AUC utilization. In particular, this study focused on the number of interventions utilized prior to knee arthroplasty, whether interventions receiving a designation of rarely appropriate were used, and the duration of nonarthroplasty treatment.

Patients with knee instability used fewer total AAOS AUC evaluated interventions prior to TKA. Subjective instability has been reported as high as 27% in patients with OA and has been associated with fear of falling, poor balance confidence, activity limitations, and lower Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function scores.12 However, it has not been found to correlate with knee laxity.13 Nevertheless, significant functional impairment with the risk of falling may reduce the number of nonarthroplasty interventions attempted. On the other hand, the presence of mechanical symptoms resulted in greater utilization of nonarthroplasty interventions. This is likely due to the greater utilization of arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal in this group of patients. Despite its inclusion as an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, arthroscopy remains a contentious treatment for symptomatic knee pain in the setting of OA.14,15

For every unit decrease in Kellgren-Lawrence OA grade, patients were 54% more likely to receive a rarely appropriate intervention prior to knee arthroplasty. This is supported by the recent literature examining the AAOS AUC for surgical management of knee OA. Riddle and colleagues developed a classification tree to determine the contributions of various prognostic variables in final classifications of the 864 clinical vignettes used to develop the appropriateness algorithm and found that OA severity was strongly favored, with only 4 of the 432 vignettes with severe knee OA judged as rarely appropriate for surgical intervention.6

Our findings, too, may be explained by an AAOS AUC system that too heavily weighs radiographic severity of knee OA, resulting in more frequent rarely appropriate interventions in patients with less severe arthritis, including nonarthroplasty treatments. It is likely that rarely appropriate interventions were attempted in this subset of our study cohort based on patient’s subjective symptoms and functional status, both of which have been shown to be discordant with radiographic severity of knee OA.16

Oral or transcutaneous prescribed opioid medications were the most frequent intervention that received a rarely appropriate designation. Patients with preoperative opioid use undergoing TKA have been shown to have a greater risk for postoperative complications and longer hospital stay, particularly those patients aged < 75 years. Younger age, use of more interventions, and decreased knee ROM at presentation were predictive of longer duration of nonarthroplasty treatment. The use of more AAOS AUC evaluated interventions in these patients suggests that the AAOS AUC model may effectively be used to manage symptomatic OA, increasing the time from presentation to knee arthroplasty.

Interestingly, the use of rarely appropriate interventions did not affect TKA timing, as would be expected in a clinically effective nonarthroplasty treatment model. The reasons for rarely appropriate nonsurgical interventions are complex and require further investigation. One possible explanation is that decreased ROM was a marker for mechanical symptoms that necessitated additional intervention in the form of knee arthroscopy, delaying time to TKA.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, the small sample size (N = 90) requires acknowledgment; however, this limitation reflects the difficulty in following patients for years prior to an operative intervention. Second, the study population consists of veterans using the VA system and may not be reflective of the general population, differing with respect to gender, racial, and socioeconomic factors. Nevertheless, studies examining TKA utilization found, aside from racial and ethnic variability, patient gender and age do not affect arthroplasty utilization rate in the VA system.17

Additional limitations stem from the retrospective nature of this study. While the Computerized Patient Record System and centralized care of the VA system allows for review of all physical therapy consultations, orthotic consultations, and medications within the VA system, any treatments and intervention delivered by non-VA providers were not captured. Furthermore, the ability to assess for confounding variables limiting the prescription of certain medications, such as chronic kidney disease with NSAIDs or liver disease with acetaminophen, was limited by our study design.

Although our study suffers from selection bias with respect to examination of nonarthroplasty treatment in patients who have ultimately undergone TKA, we feel that this subset of patients with symptomatic knee OA represents the majority of patients evaluated for knee OA by orthopaedic surgeons in the clinic setting. It should be noted that although realignment osteotomies were sometimes indicated as appropriate by AAOS AUC model in our study population, this intervention was never performed due to patient and surgeon preference. Additionally, although it is not an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, viscosupplementation was sporadically used during the study period; however, it is now off formulary at the investigation institution.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that patients without knee instability use more nonarthroplasty treatments over a longer period before TKA, and those patients with less severe knee OA are at risk of receiving an intervention judged to be rarely appropriate by the AAOS AUC. Such interventions do not affect timing of TKA. Nonarthroplasty care should be individualized to patients’ needs, and the decision to proceed with arthroplasty should be considered only after exhausting appropriate conservative measures. We recommend that providers use the AAOS AUC, especially when treating younger patients with less severe knee OA, particularly if considering opiate therapy or knee arthroscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Getty, MD, for his surgical care of some of the study patients. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) affects almost 9.3 million adults in the US and accounts for $27 billion in annual health care expenses.1,2 Due to the increasing cost of health care and an aging population, there has been renewed interest in establishing criteria for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA.

In 2013, using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness method, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an appropriate use criteria (AUC) for nonarthroplasty management of primary OA of the knee, based on orthopaedic literature and expert opinion.3 Interventions such as activity modification, weight loss, prescribed physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tramadol, prescribed oral or transcutaneous opioids, acetaminophen, intra-articular corticosteroids, hinged or unloading knee braces, arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal, and realignment osteotomy were assessed. An algorithm was developed for 576 patients scenarios that incorporated patient-specific, prognostic/predictor variables to assign designations of “appropriate,” “may be appropriate,” or “rarely appropriate,” to treatment interventions.4,5 An online version of the algorithm (orthoguidelines.org) is available for physicians and surgeons to judge appropriateness of nonarthroplasty treatments; however, it is not intended to mandate candidacy for treatment or intervention.

Clinical evaluation of the AAOS AUC is necessary to determine how treatment recommendations correlate with current practice. A recent examination of the AAOS Appropriateness System for Surgical Management of Knee OA found that prognostic/predictor variables, such as patient age, OA severity, and pattern of knee OA involvement were more heavily weighted when determining arthroplasty appropriateness than was pain severity or functional loss.6 Furthermore, non-AAOS AUC prognostic/predictor variables, such as race and gender, have been linked to disparities in utilization of knee OA interventions.7-9 Such disparities can be costly not just from a patient perceptive, but also employer and societal perspectives.10

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system represents a model of equal-access-to care system in the US that is ideal for examination of issues about health care utilization and any disparities within the AAOS AUC model and has previously been used to assess utilization of total knee arthroplasty.9 The aim of this study was to characterize utilization of the AAOS AUC for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA in a VA patient population. We asked the following questions: (1) What variables are predictive of receiving a greater number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments? (2) What variables are predictive of receiving “rarely appropriate” AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatment? (3) What factors are predictive of duration of nonarthroplasty care until total knee arthroplasty (TKA)?

Methods

The institutional review board at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio approved a retrospective chart review of nonarthroplasty treatments utilized by patients presenting to its orthopaedic section who subsequently underwent knee arthroplasty between 2013 and 2016. Eligibility criteria included patients aged ≥ 30 years with a diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral primary knee OA. Patients with posttraumatic OA, inflammatory arthritis, and a history of infectious arthritis or Charcot arthropathy of the knee were excluded. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 or a hemoglobin A1c > 8.0 at presentation were excluded as nonarthroplasty care was the recommended course of treatment above these thresholds.

Data collected included race, gender, duration of nonarthroplasty treatment, BMI, and Kellgren-Lawrence classification of knee OA at time of presentation for symptomatic knee OA.11 All AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized prior to arthroplasty intervention also were recorded (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed with GraphPad Software Prism 7.0a (La Jolla, CA) and Mathworks MatLab R2016b software (Natick, MA). Univariate analysis with Student t tests with Welch corrections in the setting of unequal variance, Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests, and Fisher exact test were generated in the appropriate setting. Multivariable analyses also were conducted. For continuous outcomes, stepwise multiple linear regression was used to generate predictive models; for binary outcomes, binomial logistic regression was used.

Factors analyzed in regression modeling for the total number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized and the likelihood of receiving a rarely appropriate treatment included gender, race, function-limiting pain, range of motion (ROM), ligamentous instability, arthritis pattern, limb alignment, mechanical symptoms, BMI, age, and Kellgren-Lawrence grade. Factors analyzed in timing of TKA included the above variables plus the total number of AUC interventions, whether the patient received an inappropriate intervention, and average appropriateness of the interventions received. Residual analysis with Cook’s distance was used to identify outliers in regression. Observations with Cook’s distance > 3 times the mean Cook’s distance were identified as potential outliers, and models were adjusted accordingly. All statistical analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set to P ≤ .05 for all outputs.

Results

In the study, 97.8% of participants identified as male, and the mean age was 62.8 years (Table 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria Interventions

Patients received a mean of 5.2 AAOS AUC evaluated interventions before undergoing arthroplasty management at a mean of 32.3 months (range 2-181 months) from initial presentation. The majority of these interventions were classified as either appropriate or may be appropriate, according to the AUC definitions (95.1%). Self-management and physical therapy programs were widely utilized (100% and 90.1%, respectively), with all use of these interventions classified as appropriate.

Hinged or unloader knee braces were utilized in about half the study patients; this intervention was classified as rarely appropriate in 4.4% of these patients. Medical therapy was also widely used, with all use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and tramadol classified as appropriate or may be appropriate. Oral or transcutaneous opioid medications were prescribed in 14.3% of patients, with 92.3% of this use classified as rarely appropriate. Although the opioid medication prescribing provider was not specifically evaluated, there were no instances in which the orthopaedic service provided an oral or transcutaneous opioid prescriptions. Procedural interventions, with the exception of corticosteroid injections, were uncommon; no patient received realignment osteotomy, and only 12.1% of patients underwent arthroscopy. The use of arthroscopy was deemed rarely appropriate in 72.7% of these cases.

Factors Associated With AAOS AUC Intervention Use

There was no difference in the number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received based on BMI (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 5.2 [1.0] vs BMI ≥ 35, 5.3 [1.1], P = .49), age (mean [SD] aged < 60 years, 5.4 [1.0] vs aged ≥ 60 years, 5.1 [1.2], P = .23), or Kellgren-Lawrence arthritic grade (mean [SD] grade ≤ 2, 5.5 [1.0] vs grade > 2, 5.1 [1.1], P = .06). These variables also were not associated with receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 0.27 [0.5] vs BMI > 35, 0.2 [0.4], P = .81; aged > 60 years, 0.3 [0.5] vs aged < 60 years, 0.2 [0.4], P = .26; Kellgren-Lawrence grade < 2, 0.4 [0.6] vs grade > 2, 0.2 [0.4], P = .1).

Regression modeling to predict total number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received produced a significant model (R2 = 0.111, P = .006). The presence of ligamentous instability (β coefficient, -1.61) and the absence of mechanical symptoms (β coefficient, -0.67) were negative predictors of number of AUC interventions received. Variance inflation factors were 1.014 and 1.012, respectively. Likewise, regression modeling to identify factors predictive of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention also produced a significant model (pseudo R2= 0.06, P = .025), with lower Kellgren-Lawrence grade the only significant predictor of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (odds ratio [OR] 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42 -0.72, per unit increase).

Timing from presentation to arthroplasty intervention was also evaluated. Age was a negative predictor (β coefficient -1.61), while positive predictors were reduced ROM (β coefficient 15.72) and having more AUC interventions (β coefficient 7.31) (model R2= 0.29, P = < .001). Age was the most significant predictor. Variance inflations factors were 1.02, 1.01, and 1.03, respectively. Receiving a rarely appropriate intervention was not associated with TKA timing.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study examined the utilization of AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty interventions for symptomatic knee OA prior to TKA. The aims of this study were to validate the AAOS AUC in a clinical setting and identify predictors of AAOS AUC utilization. In particular, this study focused on the number of interventions utilized prior to knee arthroplasty, whether interventions receiving a designation of rarely appropriate were used, and the duration of nonarthroplasty treatment.

Patients with knee instability used fewer total AAOS AUC evaluated interventions prior to TKA. Subjective instability has been reported as high as 27% in patients with OA and has been associated with fear of falling, poor balance confidence, activity limitations, and lower Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function scores.12 However, it has not been found to correlate with knee laxity.13 Nevertheless, significant functional impairment with the risk of falling may reduce the number of nonarthroplasty interventions attempted. On the other hand, the presence of mechanical symptoms resulted in greater utilization of nonarthroplasty interventions. This is likely due to the greater utilization of arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal in this group of patients. Despite its inclusion as an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, arthroscopy remains a contentious treatment for symptomatic knee pain in the setting of OA.14,15

For every unit decrease in Kellgren-Lawrence OA grade, patients were 54% more likely to receive a rarely appropriate intervention prior to knee arthroplasty. This is supported by the recent literature examining the AAOS AUC for surgical management of knee OA. Riddle and colleagues developed a classification tree to determine the contributions of various prognostic variables in final classifications of the 864 clinical vignettes used to develop the appropriateness algorithm and found that OA severity was strongly favored, with only 4 of the 432 vignettes with severe knee OA judged as rarely appropriate for surgical intervention.6

Our findings, too, may be explained by an AAOS AUC system that too heavily weighs radiographic severity of knee OA, resulting in more frequent rarely appropriate interventions in patients with less severe arthritis, including nonarthroplasty treatments. It is likely that rarely appropriate interventions were attempted in this subset of our study cohort based on patient’s subjective symptoms and functional status, both of which have been shown to be discordant with radiographic severity of knee OA.16

Oral or transcutaneous prescribed opioid medications were the most frequent intervention that received a rarely appropriate designation. Patients with preoperative opioid use undergoing TKA have been shown to have a greater risk for postoperative complications and longer hospital stay, particularly those patients aged < 75 years. Younger age, use of more interventions, and decreased knee ROM at presentation were predictive of longer duration of nonarthroplasty treatment. The use of more AAOS AUC evaluated interventions in these patients suggests that the AAOS AUC model may effectively be used to manage symptomatic OA, increasing the time from presentation to knee arthroplasty.

Interestingly, the use of rarely appropriate interventions did not affect TKA timing, as would be expected in a clinically effective nonarthroplasty treatment model. The reasons for rarely appropriate nonsurgical interventions are complex and require further investigation. One possible explanation is that decreased ROM was a marker for mechanical symptoms that necessitated additional intervention in the form of knee arthroscopy, delaying time to TKA.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, the small sample size (N = 90) requires acknowledgment; however, this limitation reflects the difficulty in following patients for years prior to an operative intervention. Second, the study population consists of veterans using the VA system and may not be reflective of the general population, differing with respect to gender, racial, and socioeconomic factors. Nevertheless, studies examining TKA utilization found, aside from racial and ethnic variability, patient gender and age do not affect arthroplasty utilization rate in the VA system.17

Additional limitations stem from the retrospective nature of this study. While the Computerized Patient Record System and centralized care of the VA system allows for review of all physical therapy consultations, orthotic consultations, and medications within the VA system, any treatments and intervention delivered by non-VA providers were not captured. Furthermore, the ability to assess for confounding variables limiting the prescription of certain medications, such as chronic kidney disease with NSAIDs or liver disease with acetaminophen, was limited by our study design.

Although our study suffers from selection bias with respect to examination of nonarthroplasty treatment in patients who have ultimately undergone TKA, we feel that this subset of patients with symptomatic knee OA represents the majority of patients evaluated for knee OA by orthopaedic surgeons in the clinic setting. It should be noted that although realignment osteotomies were sometimes indicated as appropriate by AAOS AUC model in our study population, this intervention was never performed due to patient and surgeon preference. Additionally, although it is not an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, viscosupplementation was sporadically used during the study period; however, it is now off formulary at the investigation institution.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that patients without knee instability use more nonarthroplasty treatments over a longer period before TKA, and those patients with less severe knee OA are at risk of receiving an intervention judged to be rarely appropriate by the AAOS AUC. Such interventions do not affect timing of TKA. Nonarthroplasty care should be individualized to patients’ needs, and the decision to proceed with arthroplasty should be considered only after exhausting appropriate conservative measures. We recommend that providers use the AAOS AUC, especially when treating younger patients with less severe knee OA, particularly if considering opiate therapy or knee arthroscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Getty, MD, for his surgical care of some of the study patients. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio.

1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323-1330.

2. Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1113-1121; discussion 1121-1122.

3. Members of the Writing, Review, and Voting Panels of the AUC on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee, Sanders JO, Heggeness MH, Murray J, Pezold R, Donnelly P. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):1220-1221.

4. Sanders JO, Murray J, Gross L. Non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):256-260.

5. Yates AJ Jr, McGrory BJ, Starz TW, Vincent KR, McCardel B, Golightly YM. AAOS appropriate use criteria: optimizing the non-arthroplasty management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):261-267.

6. Riddle DL, Perera RA. Appropriateness and total knee arthroplasty: an examination of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons appropriateness rating system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(12):1994-1998.

7. Morgan RC Jr, Slover J. Breakout session: ethnic and racial disparities in joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1886-1890.

8. O’Connor MI, Hooten EG. Breakout session: gender disparities in knee osteoarthritis and TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1883-1885.

9. Ibrahim SA. Racial and ethnic disparities in hip and knee joint replacement: a review of research in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):S87-S94.

10. Karmarkar TD, Maurer A, Parks ML, et al. A fresh perspective on a familiar problem: examining disparities in knee osteoarthritis using a Markov model. Med Care. 2017;55(12):993-1000.

11. Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(8):1886-1893.

12. Nguyen U, Felson DT, Niu J, et al. The impact of knee instability with and without buckling on balance confidence, fear of falling and physical function: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(4):527-534.

13. Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1506-1516.

14. Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005118.

15. Lamplot JD, Brophy RH. The role for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in knees with degenerative changes: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(7):934-938.

16. Whittle R, Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G. Average symptom trajectories following incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000281.

17. Jones A, Kwoh CK, Kelley ME, Ibrahim SA. Racial disparity in knee arthroplasty utilization in the Veterans Health Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):979-981.

1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323-1330.

2. Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1113-1121; discussion 1121-1122.

3. Members of the Writing, Review, and Voting Panels of the AUC on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee, Sanders JO, Heggeness MH, Murray J, Pezold R, Donnelly P. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):1220-1221.

4. Sanders JO, Murray J, Gross L. Non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):256-260.

5. Yates AJ Jr, McGrory BJ, Starz TW, Vincent KR, McCardel B, Golightly YM. AAOS appropriate use criteria: optimizing the non-arthroplasty management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):261-267.

6. Riddle DL, Perera RA. Appropriateness and total knee arthroplasty: an examination of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons appropriateness rating system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(12):1994-1998.

7. Morgan RC Jr, Slover J. Breakout session: ethnic and racial disparities in joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1886-1890.

8. O’Connor MI, Hooten EG. Breakout session: gender disparities in knee osteoarthritis and TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1883-1885.

9. Ibrahim SA. Racial and ethnic disparities in hip and knee joint replacement: a review of research in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):S87-S94.

10. Karmarkar TD, Maurer A, Parks ML, et al. A fresh perspective on a familiar problem: examining disparities in knee osteoarthritis using a Markov model. Med Care. 2017;55(12):993-1000.

11. Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(8):1886-1893.

12. Nguyen U, Felson DT, Niu J, et al. The impact of knee instability with and without buckling on balance confidence, fear of falling and physical function: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(4):527-534.

13. Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1506-1516.

14. Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005118.

15. Lamplot JD, Brophy RH. The role for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in knees with degenerative changes: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(7):934-938.

16. Whittle R, Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G. Average symptom trajectories following incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000281.

17. Jones A, Kwoh CK, Kelley ME, Ibrahim SA. Racial disparity in knee arthroplasty utilization in the Veterans Health Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):979-981.

Is intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injection an effective treatment for knee OA?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

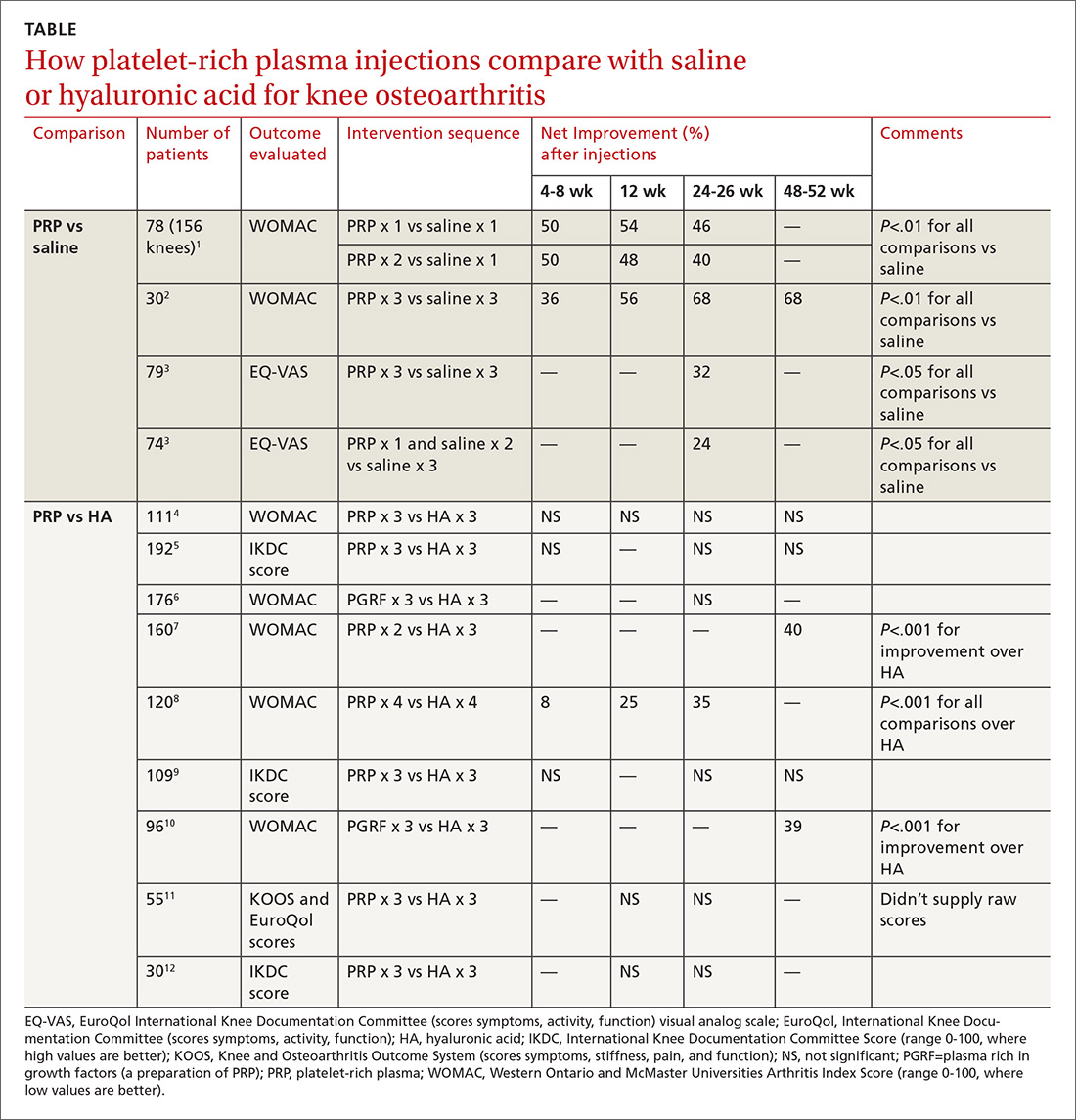

PRP vs placebo. Three RCTs compared PRP with saline placebo injections and 2 found that PRP improved the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC, a standardized scale assessing knee pain, function, and stiffness) by 40% to 70%; the third found 24% to 32% improvements in the EuroQol visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) scores at 6 months1-3 (TABLE1-12).

The first 2 studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity (baseline WOMAC scores about 50).1,2 Investigators in the first RCT injected PRP once in one subgroup and twice in another subgroup, compared with a single injection of saline in a third subgroup.1 They gave 3 weekly injections of PRP or saline in the second RCT.2

The third study enrolled mainly patients with early osteoarthritis (mean age early 50s, slightly more women). Investigators injected PRP 3 times in one subgroup and once (plus 2 saline injections) in another, compared with 3 saline injections, and evaluated patients at baseline and 6 months.3

PRP vs HA. Nine RCTs compared PRP with HA injections. Six studies (673 patients) found no significant difference; 3 studies (376 patients) found that PRP improved standardized knee assessment scores by 35% to 40% at 24-48 weeks.7,8,10 All studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity. In 7 RCTs, 4-6,9-12 investigators injected PRP or HA weekly for 3 weeks, in one RCT8 they gave 4 weekly injections, and in one7they gave 2 PRP injections separated by 4 weeks.

Three RCTs used the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, considered the most reliable standardized scoring system, which quantifies subjective symptoms (pain, stiffness, swelling, giving way), activity (climbing stairs, rising from a chair, squatting, jumping), and function pre- and postintervention.5,9,12 All 3 studies using the IKDC found no difference between PRP and HA injections. Most RCTs used the WOMAC standardized scale, scoring 5 items for pain, 2 for stiffness, and 17 for function.1,2,4,6-8.10

Risk for bias

A systematic review13 that evaluated methodologic quality of the 3 studies comparing PRP with placebo rated 21,3 at high risk of bias and one2 at moderate risk. Another meta-analysis14 performed a quality assessment including 4 of the 9 RCTs,8-10,12 comparing PRP with HA and concluded that 3 had a high risk of bias; the fourth RCT had a moderate risk. No independent quality assessments of the other RCTs were available.4-7,11

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons doesn’t recommend for or against PRP injections because of insufficient evidence and strongly recommends against HA injections based on multiple RCTs of moderate quality that found no difference between HA and placebo.15

1. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, et al. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:356-364.

2. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee arthritis: an FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:884-891.

3. Gorelli G, Gormelli CA, Ataoglu B, et al. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;25:958-965.

4. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;45:339-346.

5. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.

6. Sanchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2012;28:1070-1078.

7. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus hyaluronic acid (a one-year randomized clinical trial). Clin Med Insights: Arth Musc Dis. 2015;8:1-8.

8. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2822-2827.

9. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid to treat knee degenerative pathology: study design and preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:229-236.

10. Vaquerizo V, Plasencia MA, Arribas I, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2013;29:1635-1643.

11. Montanez-Heredia E, Irizar S, Huertas PJ, et al. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain: a randomized clinical trial in the context of the Spanish national health care system. Intl J Molec Sci. 2016;17:1064-1077.

12. Li M, Zhang C, Ai Z, et al. Therapeutic effectiveness of intra-knee articular injections of platelet-rich plasma on knee articular cartilage degeneration. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011 25:1192-11966. (Article published in Chinese with abstract in English.)

13. Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Ortho Surg Res. 2017;12:16.

14. Laudy ABM, Bakker EWP, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

15. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, 2nd ed. www.aaos.org/cc_files/aaosorg/research/guidelines/treatmentofosteoarthritisofthekneeguideline.pdf. Published May 2013. Accessed February 22, 2019.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

PRP vs placebo. Three RCTs compared PRP with saline placebo injections and 2 found that PRP improved the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC, a standardized scale assessing knee pain, function, and stiffness) by 40% to 70%; the third found 24% to 32% improvements in the EuroQol visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) scores at 6 months1-3 (TABLE1-12).

The first 2 studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity (baseline WOMAC scores about 50).1,2 Investigators in the first RCT injected PRP once in one subgroup and twice in another subgroup, compared with a single injection of saline in a third subgroup.1 They gave 3 weekly injections of PRP or saline in the second RCT.2

The third study enrolled mainly patients with early osteoarthritis (mean age early 50s, slightly more women). Investigators injected PRP 3 times in one subgroup and once (plus 2 saline injections) in another, compared with 3 saline injections, and evaluated patients at baseline and 6 months.3

PRP vs HA. Nine RCTs compared PRP with HA injections. Six studies (673 patients) found no significant difference; 3 studies (376 patients) found that PRP improved standardized knee assessment scores by 35% to 40% at 24-48 weeks.7,8,10 All studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity. In 7 RCTs, 4-6,9-12 investigators injected PRP or HA weekly for 3 weeks, in one RCT8 they gave 4 weekly injections, and in one7they gave 2 PRP injections separated by 4 weeks.

Three RCTs used the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, considered the most reliable standardized scoring system, which quantifies subjective symptoms (pain, stiffness, swelling, giving way), activity (climbing stairs, rising from a chair, squatting, jumping), and function pre- and postintervention.5,9,12 All 3 studies using the IKDC found no difference between PRP and HA injections. Most RCTs used the WOMAC standardized scale, scoring 5 items for pain, 2 for stiffness, and 17 for function.1,2,4,6-8.10

Risk for bias

A systematic review13 that evaluated methodologic quality of the 3 studies comparing PRP with placebo rated 21,3 at high risk of bias and one2 at moderate risk. Another meta-analysis14 performed a quality assessment including 4 of the 9 RCTs,8-10,12 comparing PRP with HA and concluded that 3 had a high risk of bias; the fourth RCT had a moderate risk. No independent quality assessments of the other RCTs were available.4-7,11

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons doesn’t recommend for or against PRP injections because of insufficient evidence and strongly recommends against HA injections based on multiple RCTs of moderate quality that found no difference between HA and placebo.15

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

PRP vs placebo. Three RCTs compared PRP with saline placebo injections and 2 found that PRP improved the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC, a standardized scale assessing knee pain, function, and stiffness) by 40% to 70%; the third found 24% to 32% improvements in the EuroQol visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) scores at 6 months1-3 (TABLE1-12).

The first 2 studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity (baseline WOMAC scores about 50).1,2 Investigators in the first RCT injected PRP once in one subgroup and twice in another subgroup, compared with a single injection of saline in a third subgroup.1 They gave 3 weekly injections of PRP or saline in the second RCT.2

The third study enrolled mainly patients with early osteoarthritis (mean age early 50s, slightly more women). Investigators injected PRP 3 times in one subgroup and once (plus 2 saline injections) in another, compared with 3 saline injections, and evaluated patients at baseline and 6 months.3

PRP vs HA. Nine RCTs compared PRP with HA injections. Six studies (673 patients) found no significant difference; 3 studies (376 patients) found that PRP improved standardized knee assessment scores by 35% to 40% at 24-48 weeks.7,8,10 All studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity. In 7 RCTs, 4-6,9-12 investigators injected PRP or HA weekly for 3 weeks, in one RCT8 they gave 4 weekly injections, and in one7they gave 2 PRP injections separated by 4 weeks.

Three RCTs used the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, considered the most reliable standardized scoring system, which quantifies subjective symptoms (pain, stiffness, swelling, giving way), activity (climbing stairs, rising from a chair, squatting, jumping), and function pre- and postintervention.5,9,12 All 3 studies using the IKDC found no difference between PRP and HA injections. Most RCTs used the WOMAC standardized scale, scoring 5 items for pain, 2 for stiffness, and 17 for function.1,2,4,6-8.10

Risk for bias

A systematic review13 that evaluated methodologic quality of the 3 studies comparing PRP with placebo rated 21,3 at high risk of bias and one2 at moderate risk. Another meta-analysis14 performed a quality assessment including 4 of the 9 RCTs,8-10,12 comparing PRP with HA and concluded that 3 had a high risk of bias; the fourth RCT had a moderate risk. No independent quality assessments of the other RCTs were available.4-7,11

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons doesn’t recommend for or against PRP injections because of insufficient evidence and strongly recommends against HA injections based on multiple RCTs of moderate quality that found no difference between HA and placebo.15

1. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, et al. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:356-364.

2. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee arthritis: an FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:884-891.

3. Gorelli G, Gormelli CA, Ataoglu B, et al. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;25:958-965.

4. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;45:339-346.

5. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.

6. Sanchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2012;28:1070-1078.

7. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus hyaluronic acid (a one-year randomized clinical trial). Clin Med Insights: Arth Musc Dis. 2015;8:1-8.

8. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2822-2827.

9. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid to treat knee degenerative pathology: study design and preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:229-236.

10. Vaquerizo V, Plasencia MA, Arribas I, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2013;29:1635-1643.

11. Montanez-Heredia E, Irizar S, Huertas PJ, et al. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain: a randomized clinical trial in the context of the Spanish national health care system. Intl J Molec Sci. 2016;17:1064-1077.

12. Li M, Zhang C, Ai Z, et al. Therapeutic effectiveness of intra-knee articular injections of platelet-rich plasma on knee articular cartilage degeneration. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011 25:1192-11966. (Article published in Chinese with abstract in English.)

13. Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Ortho Surg Res. 2017;12:16.

14. Laudy ABM, Bakker EWP, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

15. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, 2nd ed. www.aaos.org/cc_files/aaosorg/research/guidelines/treatmentofosteoarthritisofthekneeguideline.pdf. Published May 2013. Accessed February 22, 2019.

1. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, et al. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:356-364.

2. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee arthritis: an FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:884-891.

3. Gorelli G, Gormelli CA, Ataoglu B, et al. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;25:958-965.

4. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;45:339-346.

5. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.

6. Sanchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2012;28:1070-1078.

7. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus hyaluronic acid (a one-year randomized clinical trial). Clin Med Insights: Arth Musc Dis. 2015;8:1-8.

8. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2822-2827.

9. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid to treat knee degenerative pathology: study design and preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:229-236.

10. Vaquerizo V, Plasencia MA, Arribas I, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2013;29:1635-1643.

11. Montanez-Heredia E, Irizar S, Huertas PJ, et al. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain: a randomized clinical trial in the context of the Spanish national health care system. Intl J Molec Sci. 2016;17:1064-1077.

12. Li M, Zhang C, Ai Z, et al. Therapeutic effectiveness of intra-knee articular injections of platelet-rich plasma on knee articular cartilage degeneration. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011 25:1192-11966. (Article published in Chinese with abstract in English.)

13. Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Ortho Surg Res. 2017;12:16.

14. Laudy ABM, Bakker EWP, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

15. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, 2nd ed. www.aaos.org/cc_files/aaosorg/research/guidelines/treatmentofosteoarthritisofthekneeguideline.pdf. Published May 2013. Accessed February 22, 2019.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Probably not, based on the balance of evidence. While low-quality evidence may suggest potential benefit, the balance of evidence suggests it is no better than placebo.

Compared with saline placebo, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections may improve standardized scores for knee osteoarthritis (OA) pain, function, and stiffness by 24% to 70% for periods of 6 to 52 weeks in patients with early to moderate OA (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with methodologic flaws).

Compared with hyaluronic acid (HA), PRP probably improves scores by a similar amount for periods of 8 to 52 weeks (SOR: B, multiple RCTs with conflicting results favoring no difference). However, since HA alone likely doesn’t improve scores more than placebo (SOR: B, RCTs of moderate quality), if both HA and PRP are about the same, then both are not better than placebo.

BTK inhibitor calms pemphigus vulgaris with low-dose steroids

WASHINGTON – An investigational molecule that blocks the downstream proinflammatory effects of B cells controlled disease activity and induced clinical remission in patients with pemphigus by 12 weeks.

At the end of a 24-week, open-label trial, a key driver of the sometimes-fatal blistering disease, Deedee Murrell, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The clinical efficacy plus a favorable safety profile supports the further development of the molecule, designed and manufactured by Principia Biopharma in San Francisco. The company is currently recruiting for a pivotal phase 3 trial of PRN1008 in 120 patients with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris.