User login

RBC transfusions with surgery may increase VTE risk

In patients undergoing surgery, RBC transfusions may be associated with the development of new or progressive venous thromboembolism within 30 days of the procedure, results of a recent registry study suggest.

Patients who received perioperative RBC transfusions had significantly higher odds of developing postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) overall, as well as higher odds specifically for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), according to results published in JAMA Surgery.

“In a subset of patients receiving perioperative RBC transfusions, a synergistic and incremental dose-related risk for VTE development may exist,” Dr. Goel and her coauthors wrote.

The analysis was based on prospectively collected North American registry data including 750,937 patients who underwent a surgical procedure in 2014, of which 47,410 (6.3%) received one or more perioperative RBC transfusions. VTE occurred in 6,309 patients (0.8%), of which 4,336 cases were DVT (0.6%) and 2,514 were PE (0.3%).

The patients who received perioperative RBC transfusions had significantly increased odds of developing VTE in the 30-day postoperative period (adjusted odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.3) versus those who had no transfusions, according to results of a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, sex, length of hospital stay, use of mechanical ventilation, and other potentially confounding factors.

Similarly, researchers found transfused patients had higher odds of both DVT (aOR, 2.2; 95% CI, 2.1-2.4), and PE (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7-2.1).

Odds of VTE increased significantly along with increasing number of perioperative RBC transfusions from an aOR of 2.1 for those with just one transfusion to 4.5 for those who had three or more transfusion events (P less than .001 for trend), results of a dose-response analysis showed.

The association between RBC transfusions perioperatively and VTE postoperatively remained robust after propensity score matching and was statistically significant in all surgical subspecialties, the researchers reported.

However, they also noted that these results will require validation in prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials. “If proven, they underscore the continued need for more stringent and optimal perioperative blood management practices in addition to rigorous VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing surgery.”

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Cornell University. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goel R et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1565.

In patients undergoing surgery, RBC transfusions may be associated with the development of new or progressive venous thromboembolism within 30 days of the procedure, results of a recent registry study suggest.

Patients who received perioperative RBC transfusions had significantly higher odds of developing postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) overall, as well as higher odds specifically for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), according to results published in JAMA Surgery.

“In a subset of patients receiving perioperative RBC transfusions, a synergistic and incremental dose-related risk for VTE development may exist,” Dr. Goel and her coauthors wrote.

The analysis was based on prospectively collected North American registry data including 750,937 patients who underwent a surgical procedure in 2014, of which 47,410 (6.3%) received one or more perioperative RBC transfusions. VTE occurred in 6,309 patients (0.8%), of which 4,336 cases were DVT (0.6%) and 2,514 were PE (0.3%).

The patients who received perioperative RBC transfusions had significantly increased odds of developing VTE in the 30-day postoperative period (adjusted odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.3) versus those who had no transfusions, according to results of a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, sex, length of hospital stay, use of mechanical ventilation, and other potentially confounding factors.

Similarly, researchers found transfused patients had higher odds of both DVT (aOR, 2.2; 95% CI, 2.1-2.4), and PE (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7-2.1).

Odds of VTE increased significantly along with increasing number of perioperative RBC transfusions from an aOR of 2.1 for those with just one transfusion to 4.5 for those who had three or more transfusion events (P less than .001 for trend), results of a dose-response analysis showed.

The association between RBC transfusions perioperatively and VTE postoperatively remained robust after propensity score matching and was statistically significant in all surgical subspecialties, the researchers reported.

However, they also noted that these results will require validation in prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials. “If proven, they underscore the continued need for more stringent and optimal perioperative blood management practices in addition to rigorous VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing surgery.”

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Cornell University. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goel R et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1565.

In patients undergoing surgery, RBC transfusions may be associated with the development of new or progressive venous thromboembolism within 30 days of the procedure, results of a recent registry study suggest.

Patients who received perioperative RBC transfusions had significantly higher odds of developing postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) overall, as well as higher odds specifically for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), according to results published in JAMA Surgery.

“In a subset of patients receiving perioperative RBC transfusions, a synergistic and incremental dose-related risk for VTE development may exist,” Dr. Goel and her coauthors wrote.

The analysis was based on prospectively collected North American registry data including 750,937 patients who underwent a surgical procedure in 2014, of which 47,410 (6.3%) received one or more perioperative RBC transfusions. VTE occurred in 6,309 patients (0.8%), of which 4,336 cases were DVT (0.6%) and 2,514 were PE (0.3%).

The patients who received perioperative RBC transfusions had significantly increased odds of developing VTE in the 30-day postoperative period (adjusted odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.3) versus those who had no transfusions, according to results of a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, sex, length of hospital stay, use of mechanical ventilation, and other potentially confounding factors.

Similarly, researchers found transfused patients had higher odds of both DVT (aOR, 2.2; 95% CI, 2.1-2.4), and PE (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7-2.1).

Odds of VTE increased significantly along with increasing number of perioperative RBC transfusions from an aOR of 2.1 for those with just one transfusion to 4.5 for those who had three or more transfusion events (P less than .001 for trend), results of a dose-response analysis showed.

The association between RBC transfusions perioperatively and VTE postoperatively remained robust after propensity score matching and was statistically significant in all surgical subspecialties, the researchers reported.

However, they also noted that these results will require validation in prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials. “If proven, they underscore the continued need for more stringent and optimal perioperative blood management practices in addition to rigorous VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing surgery.”

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Cornell University. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goel R et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1565.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who received perioperative RBC transfusions had significantly increased odds of developing VTE in the 30-day postoperative period (adjusted odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.3), compared with patients who did not receive transfusions.

Study details: An analysis of prospectively collected North American registry data including 750,937 patients who underwent a surgical procedure in 2014.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Cornell University, New York. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Goel R et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1565.

Malnourished U.S. inpatients often go untreated

WASHINGTON – Hospital staffs often fail to treat .

A retrospective review of more than 150,000 patients admitted during a single year at any center within a large, multicenter U.S. hospital system found that even when patients receive oral nutritional supplementation, there is often a substantial delay to its onset.

The data also suggested potential benefits from treating malnutrition with oral nutritional supplementation (ONS). Patients who received ONS had a 10% relative reduction in their rate of 30-day readmission, compared with malnourished patients who did not receive supplements after adjusting for several baseline demographic and clinical variables, Gerard Mullin, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. His analysis also showed that every doubling of the time from hospital admission to an order for ONS significantly linked with a 6% rise in hospital length of stay.

The findings “highlight the importance of malnutrition screening on admission, starting a nutrition intervention as soon as malnutrition is confirmed, and treating with appropriate ONS,” said Dr. Mullin, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and director of the Celiac Disease Clinic. A standard formulation of Ensure was the ONS routinely used at the Johns Hopkins hospitals

“We’re missing malnutrition,” Dr. Mullin said in an interview. The hospital accreditation standards of the Joint Commission call for assessment of the nutritional status of hospitalized patients within 24 hours of admission (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015 Oct;41[10]:469-73). Screening is “not uniformly done,” and when malnutrition is identified, the finding must usually pass through several layers of a hospital’s medico-bureaucratic process before treatment actually starts, he noted. Plus, there’s often dismissal of the importance of intervention. “It’s important to treat patients with ONS sooner than later,” he said.

Dr. Mullin and his associates studied hospital records for 153,161 people admitted to any of the Baltimore-area hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system during October 2016 through the end of September 2017. The hospital staff routinely assessed nutritional status of patients after admission with a two-question screen based on the Malnutrition Screening Tool (Nutrition. 1999 June;15[6]:458-64): Have you had unplanned weight loss of 10 pounds or more during the past 6 months? Have you had decreased oral intake over the past 5 days? This identified 30,284 (20%) who qualified as possibly malnourished by either criterion. The researchers also retrospectively applied a more detailed screen to the patient records using the criteria set by an international consensus guideline committee in 2010 (J Parenter Enteraal Nutr. 2010 Mar-Apr;34[2]:156-9). This identified 8,713 of the hospitalized patients (6%) as malnourished soon after admission. Despite these numbers a scant 274 patients among these 8,713 (3%) actually received ONS, Dr. Mullin reported. In addition, it took an average of 85 hours from the time of each malnourished patient’s admission to when the ONS order appeared in their record.

Dr. Mullin conceded that both the association his group found between treatment with ONS and a reduced rate of 30-day readmission to any of the hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system, and the association between a delay in the time to the start of ONS and length of stay may have been confounded by factors not accounted for in the adjustments they applied. But he maintained that the links are consistent with results from prior studies, and warrant running prospective, randomized studies to better document the impact of ONS on newly admitted patients identified as malnourished.

“We need more of these types of studies and interventional trials to show that ONS makes a difference,” Dr. Mullin said.

The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Source: Mullin G et al. DDW 2018 presentation 883.

WASHINGTON – Hospital staffs often fail to treat .

A retrospective review of more than 150,000 patients admitted during a single year at any center within a large, multicenter U.S. hospital system found that even when patients receive oral nutritional supplementation, there is often a substantial delay to its onset.

The data also suggested potential benefits from treating malnutrition with oral nutritional supplementation (ONS). Patients who received ONS had a 10% relative reduction in their rate of 30-day readmission, compared with malnourished patients who did not receive supplements after adjusting for several baseline demographic and clinical variables, Gerard Mullin, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. His analysis also showed that every doubling of the time from hospital admission to an order for ONS significantly linked with a 6% rise in hospital length of stay.

The findings “highlight the importance of malnutrition screening on admission, starting a nutrition intervention as soon as malnutrition is confirmed, and treating with appropriate ONS,” said Dr. Mullin, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and director of the Celiac Disease Clinic. A standard formulation of Ensure was the ONS routinely used at the Johns Hopkins hospitals

“We’re missing malnutrition,” Dr. Mullin said in an interview. The hospital accreditation standards of the Joint Commission call for assessment of the nutritional status of hospitalized patients within 24 hours of admission (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015 Oct;41[10]:469-73). Screening is “not uniformly done,” and when malnutrition is identified, the finding must usually pass through several layers of a hospital’s medico-bureaucratic process before treatment actually starts, he noted. Plus, there’s often dismissal of the importance of intervention. “It’s important to treat patients with ONS sooner than later,” he said.

Dr. Mullin and his associates studied hospital records for 153,161 people admitted to any of the Baltimore-area hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system during October 2016 through the end of September 2017. The hospital staff routinely assessed nutritional status of patients after admission with a two-question screen based on the Malnutrition Screening Tool (Nutrition. 1999 June;15[6]:458-64): Have you had unplanned weight loss of 10 pounds or more during the past 6 months? Have you had decreased oral intake over the past 5 days? This identified 30,284 (20%) who qualified as possibly malnourished by either criterion. The researchers also retrospectively applied a more detailed screen to the patient records using the criteria set by an international consensus guideline committee in 2010 (J Parenter Enteraal Nutr. 2010 Mar-Apr;34[2]:156-9). This identified 8,713 of the hospitalized patients (6%) as malnourished soon after admission. Despite these numbers a scant 274 patients among these 8,713 (3%) actually received ONS, Dr. Mullin reported. In addition, it took an average of 85 hours from the time of each malnourished patient’s admission to when the ONS order appeared in their record.

Dr. Mullin conceded that both the association his group found between treatment with ONS and a reduced rate of 30-day readmission to any of the hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system, and the association between a delay in the time to the start of ONS and length of stay may have been confounded by factors not accounted for in the adjustments they applied. But he maintained that the links are consistent with results from prior studies, and warrant running prospective, randomized studies to better document the impact of ONS on newly admitted patients identified as malnourished.

“We need more of these types of studies and interventional trials to show that ONS makes a difference,” Dr. Mullin said.

The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Source: Mullin G et al. DDW 2018 presentation 883.

WASHINGTON – Hospital staffs often fail to treat .

A retrospective review of more than 150,000 patients admitted during a single year at any center within a large, multicenter U.S. hospital system found that even when patients receive oral nutritional supplementation, there is often a substantial delay to its onset.

The data also suggested potential benefits from treating malnutrition with oral nutritional supplementation (ONS). Patients who received ONS had a 10% relative reduction in their rate of 30-day readmission, compared with malnourished patients who did not receive supplements after adjusting for several baseline demographic and clinical variables, Gerard Mullin, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. His analysis also showed that every doubling of the time from hospital admission to an order for ONS significantly linked with a 6% rise in hospital length of stay.

The findings “highlight the importance of malnutrition screening on admission, starting a nutrition intervention as soon as malnutrition is confirmed, and treating with appropriate ONS,” said Dr. Mullin, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and director of the Celiac Disease Clinic. A standard formulation of Ensure was the ONS routinely used at the Johns Hopkins hospitals

“We’re missing malnutrition,” Dr. Mullin said in an interview. The hospital accreditation standards of the Joint Commission call for assessment of the nutritional status of hospitalized patients within 24 hours of admission (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015 Oct;41[10]:469-73). Screening is “not uniformly done,” and when malnutrition is identified, the finding must usually pass through several layers of a hospital’s medico-bureaucratic process before treatment actually starts, he noted. Plus, there’s often dismissal of the importance of intervention. “It’s important to treat patients with ONS sooner than later,” he said.

Dr. Mullin and his associates studied hospital records for 153,161 people admitted to any of the Baltimore-area hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system during October 2016 through the end of September 2017. The hospital staff routinely assessed nutritional status of patients after admission with a two-question screen based on the Malnutrition Screening Tool (Nutrition. 1999 June;15[6]:458-64): Have you had unplanned weight loss of 10 pounds or more during the past 6 months? Have you had decreased oral intake over the past 5 days? This identified 30,284 (20%) who qualified as possibly malnourished by either criterion. The researchers also retrospectively applied a more detailed screen to the patient records using the criteria set by an international consensus guideline committee in 2010 (J Parenter Enteraal Nutr. 2010 Mar-Apr;34[2]:156-9). This identified 8,713 of the hospitalized patients (6%) as malnourished soon after admission. Despite these numbers a scant 274 patients among these 8,713 (3%) actually received ONS, Dr. Mullin reported. In addition, it took an average of 85 hours from the time of each malnourished patient’s admission to when the ONS order appeared in their record.

Dr. Mullin conceded that both the association his group found between treatment with ONS and a reduced rate of 30-day readmission to any of the hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system, and the association between a delay in the time to the start of ONS and length of stay may have been confounded by factors not accounted for in the adjustments they applied. But he maintained that the links are consistent with results from prior studies, and warrant running prospective, randomized studies to better document the impact of ONS on newly admitted patients identified as malnourished.

“We need more of these types of studies and interventional trials to show that ONS makes a difference,” Dr. Mullin said.

The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Source: Mullin G et al. DDW 2018 presentation 883.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Malnourished U.S. hospital inpatients often go untreated.

Major finding: Three percent of patients retrospectively identified as malnourished soon after hospital admission received oral nutritional supplementation.

Study details: Retrospective review of 153,161 patients admitted to a large U.S. hospital network during 2016-2017.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

Source: Mullin G et al. Digestive Disease Week presentation 883.

FDA issues recommendations to avoid surgical fires

The Food and Drug Administration on May 29 issued a set of recommendations to medical professionals and health care facility staff to reduce the occurrence of surgical fires on or near a patient.

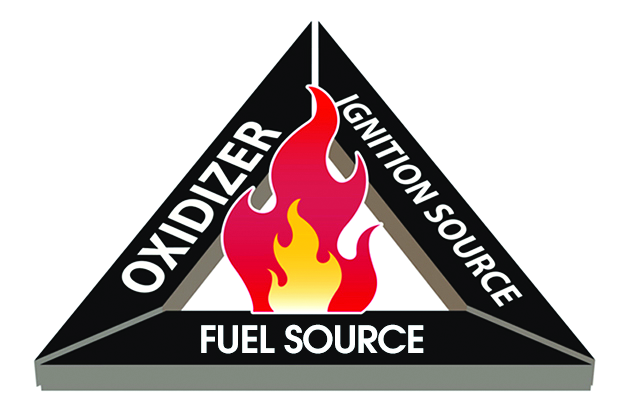

Surgical fires most often occur when there is an oxygen-enriched environment (a concentration of greater than 30%). In addition to an oxygen source, the other two necessary elements of the “fire triangle” are an ignition source and a fuel source.

The recommendations discuss the safe use of devices or items that may serve as a source of any one of those three elements.

Oxygen: Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed. If it is, titrate to the minimum concentration needed for adequate saturation. Closed oxygen delivery systems (such as a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube) are safer than open oxygen delivery systems (such as a nasal cannula or mask). If you must use an open system, take additional precautions to exclude oxygen and flammable/combustible gases from the operative field, such as draping techniques that avoid accumulation of oxygen.

Ignition sources: Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen are being delivered. Check for insulation failure before use, and keep devices clean of char and tissue. When not in use, place the devices safely away from the patient and drapes. Devices are safer to use if you can allow time for the oxygen concentration in the room to decrease.

Fuel sources: Ensure dry conditions prior to draping, avoiding pooling of alcohol-based antiseptics during skin preparation. Use the appropriate-sized applicator for the surgical site. Be aware of products that may serve as a fuel source, such as oxygen-trapping gauze, plastic laryngeal masks, and aware of potential patient sources such as hair or gastrointestinal gases.

Training should include how to manage fires that do occur – stop the ignition source, then extinguish the fire – and evacuation procedures.

Read the full recommendations here.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 29 issued a set of recommendations to medical professionals and health care facility staff to reduce the occurrence of surgical fires on or near a patient.

Surgical fires most often occur when there is an oxygen-enriched environment (a concentration of greater than 30%). In addition to an oxygen source, the other two necessary elements of the “fire triangle” are an ignition source and a fuel source.

The recommendations discuss the safe use of devices or items that may serve as a source of any one of those three elements.

Oxygen: Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed. If it is, titrate to the minimum concentration needed for adequate saturation. Closed oxygen delivery systems (such as a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube) are safer than open oxygen delivery systems (such as a nasal cannula or mask). If you must use an open system, take additional precautions to exclude oxygen and flammable/combustible gases from the operative field, such as draping techniques that avoid accumulation of oxygen.

Ignition sources: Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen are being delivered. Check for insulation failure before use, and keep devices clean of char and tissue. When not in use, place the devices safely away from the patient and drapes. Devices are safer to use if you can allow time for the oxygen concentration in the room to decrease.

Fuel sources: Ensure dry conditions prior to draping, avoiding pooling of alcohol-based antiseptics during skin preparation. Use the appropriate-sized applicator for the surgical site. Be aware of products that may serve as a fuel source, such as oxygen-trapping gauze, plastic laryngeal masks, and aware of potential patient sources such as hair or gastrointestinal gases.

Training should include how to manage fires that do occur – stop the ignition source, then extinguish the fire – and evacuation procedures.

Read the full recommendations here.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 29 issued a set of recommendations to medical professionals and health care facility staff to reduce the occurrence of surgical fires on or near a patient.

Surgical fires most often occur when there is an oxygen-enriched environment (a concentration of greater than 30%). In addition to an oxygen source, the other two necessary elements of the “fire triangle” are an ignition source and a fuel source.

The recommendations discuss the safe use of devices or items that may serve as a source of any one of those three elements.

Oxygen: Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed. If it is, titrate to the minimum concentration needed for adequate saturation. Closed oxygen delivery systems (such as a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube) are safer than open oxygen delivery systems (such as a nasal cannula or mask). If you must use an open system, take additional precautions to exclude oxygen and flammable/combustible gases from the operative field, such as draping techniques that avoid accumulation of oxygen.

Ignition sources: Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen are being delivered. Check for insulation failure before use, and keep devices clean of char and tissue. When not in use, place the devices safely away from the patient and drapes. Devices are safer to use if you can allow time for the oxygen concentration in the room to decrease.

Fuel sources: Ensure dry conditions prior to draping, avoiding pooling of alcohol-based antiseptics during skin preparation. Use the appropriate-sized applicator for the surgical site. Be aware of products that may serve as a fuel source, such as oxygen-trapping gauze, plastic laryngeal masks, and aware of potential patient sources such as hair or gastrointestinal gases.

Training should include how to manage fires that do occur – stop the ignition source, then extinguish the fire – and evacuation procedures.

Read the full recommendations here.

Management of Short Bowel Syndrome, High-Output Enterostomy, and High-Output Entero-Cutaneous Fistulas in the Inpatient Setting

From the University of Texas Southwestern, Department of Internal Medicine, Dallas, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: To define intestinal failure and associated diseases that often lead to diarrhea and high-output states, and to provide a literature review on the current evidence and practice guidelines for the management of these conditions in the context of a clinical case.

- Methods: Database search on dietary and medical interventions as well as major societal guidelines for the management of intestinal failure and associated conditions.

- Results: Although major societal guidelines exist, the guidelines vary greatly amongst various specialties and are not supported by strong evidence from large randomized controlled trials. The majority of the guidelines recommend consideration of several drug classes, but do not specify medications within the drug class, optimal dose, frequency, mode of administration, and how long to trial a regimen before considering it a failure and adding additional medical therapies.

- Conclusions: Intestinal failure and high-output states affect a very heterogenous population with high morbidity and mortality. This subset of patients should be managed using a multidisciplinary approach involving surgery, gastroenterology, dietetics, internal medicine and ancillary services that include but are not limited to ostomy nurses and home health care. Implementation of a standardized protocol in the electronic medical record including both medical and nutritional therapies may be useful to help optimize efficacy of medications, aid in nutrient absorption, decrease cost, reduce hospital length of stay, and decrease hospital readmissions.

Key words: short bowel syndrome; high-output ostomy; entero-cutaneous fistula; diarrhea; malnutrition.

Intestinal failure includes but is not limited to short bowel syndrome (SBS), high-output enterostomy, and high-output related to entero-cutaneous fistulas (ECF). These conditions are unfortunate complications after major abdominal surgery requiring extensive intestinal resection leading to structural SBS. Absorption of macronutrients and micronutrients is most dependent on the length and specific segment of remaining intact small intestine [1]. The normal small intestine length varies greatly but ranges from 300 to 800 cm, while in those with structural SBS the typical length is 200 cm or less [2,3]. Certain malabsorptive enteropathies and severe intestinal dysmotility conditions may manifest as functional SBS as well. Factors that influence whether an individual will develop functional SBS despite having sufficient small intestinal absorptive area include the degree of jejunal absorptive efficacy and the ability to overcompensate with enough oral caloric intake despite high fecal energy losses, also known as hyperphagia [4].

Pathophysiology

Maintenance of normal bodily functions and homeostasis is dependent on sufficient intestinal absorption of essential macronutrients, micronutrients, and fluids. The hallmark of intestinal failure is based on the presence of decreased small bowel absorptive surface area and subsequent increased losses of key solutes and fluids [1]. Intestinal failure is a broad term that is comprised of 3 distinct phenotypes. The 3 functional classifications of intestinal failure include the following:

- Type 1. Acute intestinal failure is generally self-limiting, occurs after abdominal surgery, and typically lasts less than 28 days.

- Type 2. Subacute intestinal failure frequently occurs in septic, stressed, or metabolically unstable patients and may last up to several months.

- Type 3. Chronic intestinal failure occurs due to a chronic condition that generally requires indefinite parenteral nutrition (PN) [1,3,4].

SBS and enterostomy formation are often associated with excessive diarrhea, such that it is the most common etiology for postoperative readmissions. The definition of “high-output” varies amongst studies, but output is generally considered to be abnormally high if it is greater than 500 mL per 24 hours in ECFs and greater than 1500 mL per 24 hours for enterostomies. There is significant variability from patient to patient, as output largely depends on length of remaining bowel [2,4].

Epidemiology

SBS, high-output enterostomy, and high-output from ECFs comprise a wide spectrum of underlying disease states, including but not limited to inflammatory bowel disease, post-surgical fistula formation, intestinal ischemia, intestinal atresia, radiation enteritis, abdominal trauma, and intussusception [5]. Due to the absence of a United States registry of patients with intestinal failure, the prevalence of these conditions is difficult to ascertain. Most estimations are made using registries for patients on total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The Crohns and Colitis Foundation of America estimates 10,000 to 20,000 people suffer from SBS in the United States. This heterogenous patient population has significant morbidity and mortality for dehydration related to these high-output states. While these conditions are considered rare, they are relatively costly to the health care system. These patients are commonly managed by numerous medical and surgical services, including internal medicine, gastroenterology, surgery, dietitians, wound care nurses, and home health agencies. Management strategies differ amongst these specialties and between professional societies, which makes treatment strategies highly variable and perplexing to providers taking care of this patient population. Furthermore, most of the published guidelines are based on expert opinion and lack high-quality clinical evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Effectively treating SBS and reducing excess enterostomy output leads to reduced rates of dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, initiation of PN, weight loss and ultimately a reduction in malnutrition. Developing hospital-wide management protocols in the electronic medical record for this heterogenous condition may lead to less complications, fewer hospitalizations, and an improved quality of life for these patients.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 72-year-old man with history of rectal adenocarcinoma stage T4bN2 status post low anterior resection (LAR) with diverting loop ileostomy and neoadjuvant chemoradiation presented to the hospital with a 3-day history of nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and productive cough.

Additional History

On further questioning, the patient also reported odynophagia and dysphagia related to thrush. Because of his decreased oral intake, he stopped taking his usual insulin regimen prior to admission. His cancer treatment course was notable for a LAR with diverting loop ileostomy which was performed 5 months prior. He had also completed 3 out of 8 cycles of capecitabine and oxaliplatin-based therapy 2 weeks prior to this presentation.

Physical Examination

Significant physical examination findings included dry mucous membranes, oropharyngeal candidiasis, tachycardia, clear lungs, hypoactive bowel sounds, nontender, non-distended abdomen, and a right lower abdominal ileostomy bag with semi-formed stool.

Laboratory test results were pertinent for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with an anion gap of 33, lactic acidosis, acute kidney injury (creatinine 2.7 mg/dL from a baseline of 1.0) and blood glucose of 1059 mg/dL. Remainder of complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were unremarkable.

Hospital Course

The patient was treated for oropharyngeal candidiasis with fluconazole, started on an insulin drip and given intravenous fluids (IVFs) with subsequent resolution of DKA. Once the DKA resolved, his diet was advanced to a mechanical soft, moderate calorie, consistent carbohydrate diet (2000 calories allowed daily with all foods chopped, pureed or cooked, and all meals containing nearly equal amounts of carbohydrates). He was also given Boost supplementation 3 times per day, and daily weights were recorded while assessing for fluid losses. However, during his hospital course the patient developed increasing ileostomy output ranging from 2.7 to 6.5 L per day that only improved when he stopped eating by mouth (NPO).

What conditions should be evaluated prior to starting therapy for high-output enterostomy/diarrhea from either functional or structural SBS?

Prior to starting anti-diarrheal and anti-secretory therapy, infectious and metabolic etiologies for high-enterostomy output should be ruled out. Depending on the patient’s risk factors (eg, recent sick contacts, travel) and whether they are immunocompetent versus immunosuppressed, infectious studies should be obtained. In this patient, Clostridium difficile, stool culture, Giardia antigen, stool ova and parasites were all negative. Additional metabolic labs including thyroid-stimulating hormone, fecal elastase, and fecal fat were obtained and were all within normal limits. In this particular scenario, fecal fat was obtained while he was NPO. Testing for fat malabsorption and pancreatic insufficiency in a patient that is consuming less than 100 grams of fat per day can result in a false-negative outcome, however, and was not an appropriate test in this patient.

Hospital Course Continued

Once infectious etiologies were ruled out, the patient was started on anti-diarrheal medication consisting of loperamide 2 mg every 6 hours and oral pantoprazole 40 mg once per day. The primary internal medicine team speculated that the Boost supplementation may be contributing to the diarrhea because of its hyperosmolar concentration and wanted to discontinue it, but because the patient had protein-calorie malnutrition the dietician recommended continuing Boost supplementation. The primary internal medicine team also encouraged the patient to drink Gatorade with each meal with the approval from the dietician.

What are key dietary recommendations to help reduce high-output enterostomy/diarrhea?

Dietary recommendations are often quite variable depending on the intestinal anatomy (specifically, whether the colon is intact or absent), comorbidities such as renal disease, and severity of fluid and nutrient loses. This patient has the majority of his colon remaining; however, fluid and nutrients are being diverted away from his colon because he has a loop ileostomy. To reduce enterostomy output, it is generally recommended that liquids be consumed separately from solids, and that oral rehydration solutions (ORS) should replace most hyperosmolar and hypoosmolar liquids. Although these recommendations are commonly used, there is sparse data to suggest separating liquids from solids in a medically stable patient with SBS is indeed necessary [6]. In our patient, however, because he has not yet reached medical stability, it would be reasonable to separate the consumption of liquids from solids. The solid component of a SBS diet should consist mainly of protein and carbohydrates, with limited intake of simple sugars and sugar alcohols. If the colon remains intact, it is particularly important to limit fats to less than 30% of the daily caloric intake, to consume a low-oxalate diet, supplement with oral calcium to reduce the risk of calcium-oxalate nephrolithiasis, and increase dietary fiber intake as tolerated. Soluble fiber is fermented by colonic bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and serve as an additional energy source [7,8]. Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are good sources of fat because the body is able to absorb them into the bloodstream without the use of intestinal lymphatics, which may be damaged or absent in those with intestinal failure. For this particular patient, he would have benefitted from initiation of ORS and counseled to sip on it throughout the day while limiting liquid consumption during meals. He should have also been advised to limit plain Gatorade and Boost as they are both hyperosmolar liquid formulations and can worsen diarrhea. If the patient was unable to tolerate the taste of standard ORS formulations, or the hospital did not have any ORS on formulary, sugar, salt and water at specific amounts may be added to create a homemade ORS. In summary, this patient would have likely tolerated protein in solid form better than liquid protein supplementation.

Hospital Course Continued

The patient continued to have greater than 5 L of output from the ileostomy per day, so the following day the primary team increased the loperamide from 2 mg every 6 hours to 4 mg every 6 hours, added 2 tabs of diphenoxylate-atropine every 8 hours, and made the patient NPO. He continued to require IVFs and frequent electrolyte repletion because of the significant ongoing gastrointestinal losses.

What is the recommended first-line medical therapy for high-output enterostomy/diarrhea?

Anti-diarrheal medications are commonly used in high-output states because they work by reducing the rate of bowel translocation thereby allowing for longer time for nutrient and fluid absorption in the small and large intestine. Loperamide in particular also improves fecal incontinence because it effects the recto-anal inhibitory reflex and increases internal anal sphincter tone [9]. Four RCTs showed that loperamide lead to a significant reduction in enterostomy output compared to placebo with enterostomy output reductions ranging from 22% to 45%; varying dosages of loperamide were used, and ranged from 6 mg per day to 16 total mg per day [10–12]. King et al compared loperamide and codeine to placebo and found that both medications led to reductions in enterostomy output with a greater reduction and better side effect profile in those that received loperamide or combination therapy with loperamide and codeine [13,14]. The majority of studies used a maximum dose of 16 mg per day of loperamide, and this is the maxium daily dose approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Interestingly however, loperamide circulates through the enterohepatic circulation which is severely disrupted in SBS, so titrating up to a maximum dose of 32 mg per day while closely monitoring for side effects is also practiced by experts in intestinal failure [15]. It is also important to note that anti-diarrheal medications are most effective when administered 20 to 30 minutes prior to meals and not scheduled every 4 to 6 hours if the patient is eating by mouth. If intestinal transit is so rapid such that undigested anti-diarrheal tablets or capsules are visualized in the stool or stoma, medications can be crushed or opened and mixed with liquids or solids to enhance digestion and absorption.

Hospital Course Continued

The patient continued to have greater than 3 L of ileostomy output per day despite being on scheduled loperamide, diphenoxylate-atropine, and a proton pump inhibitory (PPI), although improved from greater than 5 L per day. He was subsequently started on opium tincture 6 mg every 6 hours, psyllium 3 times per day, the dose of diphenoxylate-atropine was increased from 2 tablets every 8 hours to 2 tablets every 6 hours, and he was encouraged to drink water in between meals. As mentioned previously, the introduction of dietary fiber should be carefully monitored, as this patient population is commonly intolerant of high dietary fiber intake, and hypoosmolar liquids like water should actually be minimized. Within a 48-hour time period, the surgical team recommended increasing the loperamide from 4 mg every 6 hours (16 mg total daily dose) to 12 mg every 6 hours (48 mg total daily dose), increased opium tincture from 6 mg every 6 hours (24 mg total daily dose) to 10 mg every 6 hours (40 mg total daily dose), and increased oral pantoprazole from 40 mg once per day to twice per day.

What are important considerations with regard to dose changes?

Evidence is lacking to suggest an adequate time period to monitor for response to therapy in regards to improvement in diarrheal output. In this scenario, it may have been prudent to wait 24 to 48 hours after each medication change instead of making drastic dose changes in several medications simultaneously. PPIs irreversibly inhibit gastrointestinal acid secretion as do histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) but to a lesser degree, and thus reduce high-output enterostomy [16]. Reduction in pH related to elevated gastrin levels after intestinal resection is associated with pancreatic enzyme denaturation and downstream bile salt dysfunction, which can further lead to malabsorption [17]. Gastrin hypersecretion is most prominent within the first 6 months after intestinal resection such that the use of high- dose PPIs for reduction in gastric acid secretion are most efficacious within that time period [18,19]. Jeppesen et al demonstrated that both omeprazole 40 mg oral twice per day and ranitidine 150 mg IV once per day were effective in reducing enterostomy output, although greater reductions were seen with omeprazole [20]. Three studies using cimetidine (both oral and IV formulations) with dosages varying from 200 mg to 800 mg per day showed significant reductions in enterostomy output as well [21–23].

Hospital Course Continued

Despite the previously mentioned interventions, the patient’s ileostomy output remained greater than 3 L per day. Loperamide was increased from 12 mg every 6 hours to 16 mg every 6 hours (64 mg total daily dose) hours and opium tincture was increased from 10 mg to 16 mg every 6 hours (64 mg total daily dose). Despite these changes, no significant reduction in output was noted, so the following day, 4 grams of cholestyramine light was added twice per day.

If the patient continues to have high-output enterostomy/diarrhea, what are additional treatment options?

Bile acid binding resins like cholestyramine, colestipol, and colesevelam are occasionally used if there is a high suspicion for bile acid diarrhea. Bile salt diarrhea typically occurs because of alterations in the enterohepatic circulation of bile salts, which leads to an increased level of bile salts in the colon and stimulation of electrolyte and water secretion and watery diarrhea [24]. Optimal candidates for bile acid binding therapy are those with an intact colon and less than 100 cm of resected ileum. Patients with little to no remaining or functional ileum have a depleted bile salt pool, therefore the addition of bile acid resin binders may actually lead to worsening diarrhea secondary to bile acid deficiency and fat malabsorption. Bile-acid resin binders can also decrease oxalate absorption and precipitate oxalate stone formation in the kidneys. Caution should also be taken to ensure that these medications are administered separately from the remainder of the patient’s medications to limit medication binding.

If the patient exhibits hemodynamic stability, alpha-2 receptor agonists are occasionally used as adjunctive therapy in reducing enterostomy output, although strong evidence to support its use is lacking. The mechanism of action involves stimulation of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors on enteric neurons, which theoretically causes a reduction in gastric and colonic motility and decreases fluid secretion. Buchman et al showed that the effects of a clonidine patch versus placebo did not in fact lead to a significant reduction in enterostomy output; however, a single case report suggested that the combination of 1200 mcg of clonidine per day and somatostatin resulted in decreased enterostomy output via alpha 2-receptor inhibition of adenylate cyclase [25,26].

Hospital Course Continued

The patient’s ileostomy output remained greater than 3 L per day, so loperamide was increased from 14 mg every 6 hours to 20 mg every 6 hours (80 mg total daily dose), cholestyramine was discontinued because of metabolic derangements, and the patient was initiated on 100 mcg of subcutaneous octreotide 3 times per day. Colorectal surgery was consulted for ileostomy takedown given persistently high-output, but surgery was deferred. After a 16-day hospitalization, the patient was eventually discharged home. At the time of discharge, he was having 2–3 L of ileostomy output per day and plans for future chemotherapy were discontinued because of this.

Does hormonal therapy have a role in the management of high-output enterostomy or entero-cutaneous fistulas?

Somatostatin analogues are growth-hormone inhibiting factors that have been used in the treatment of SBS and gastrointestinal fistulas. These medications reduce intestinal and pancreatic fluid secretion, slow intestinal motility, and inhibit the secretion of several hormones including gastrin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, cholecystokinin, and other key intestinal hormones. There is conflicting evidence for the role of these medications in reducing enterostomy output when first-line treatments have failed. Several previous studies using octreotide or somatostatin showed significant reductions in enterostomy output using variable dosages [27–30]. One study using the long-acting release depot octreotide preparation in 8 TPN-dependent patients with SBS showed a significant increase in small bowel transit time, however there was no significant improvement in the following parameters: body weight, stool weight, fecal fat excretion, stool electrolyte excretion, or gastric emptying [31]. Other studies evaluating enterostomy output from gastrointestinal and pancreatic fistulas comparing combined therapy with octreotide and TPN to placebo and TPN failed to show a significant difference in output and spontaneous fistula closure within 20 days of treatment initiation [32]. Because these studies use highly variable somatostatin analogue dosages and routes of administration, the most optimal dosing and route of administration (SQ versus IV) are unknown. In patients with difficult to control blood sugars, initiation of somatostatin analogues should be cautioned since these medications can lead to blood sugar alterations [33]. Additional unintended effects include impairment in intestinal adaptation and an increased risk in gallstone formation [8].

The most recent medical advances in SBS management include gut hormones. Glucagon-like peptide 2 (GLP-2) analogues improve structural and functional intestinal adaptation following intestinal resection by decreasing gastric emptying, decreasing gastric acid secretion, increasing intestinal blood flow, and enhancing nutrient and fluid absorption. Teduglutide, a GLP-2 analog, was successful in reducing fecal energy losses and increasing intestinal wet weight absorption, and reducing the need for PN support in SBS patients [1].

Whose problem is it anyway?

Not only is there variation in management strategies among subspecialties, but recommendations amongst societies within the same subspecialty differ, and thus make management perplexing.

Gastroenterology Guidelines

Several major gastroenterology societies have published guidelines on the management of diarrhea in patients with intestinal failure. The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) published guidelines on the management of SBS in 2006 and recommended the following first-line therapy for diarrhea-related complications: start loperamide at 2–8 mg thirty minutes prior to meals, taken up to 4 times per day, and the addition of codeine phosphate 30–60 mg thirty minutes before meals if output remains above goal on loperamide monotherapy. Cholestyramine may be added for those with 100 cm or less of resected terminal ileum to assist with bile-salt-induced diarrhea, though no specific dosage recommendations were reported. In regards to anti-secretory medications, the BSG recommends cimetidine (400 mg oral or IV 4 times per day), ranitidine (300 mg oral twice per day), or omeprazole (40 mg oral once per day or IV twice per day) to reduce jejunostomy output particularly in patients with greater than 2 L of output per day [15,34]. If diarrhea or enterostomy output continues to remain above goal, the guidelines suggest initiating octreotide and/or growth factors (although dosing and duration of therapy is not discussed in detail), and considering evaluation for intestinal transplant once the patient develops complications related to long-term TPN.

The American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) published guidelines and a position statement in 2003 for the management of high-gastric output and fluid losses. For postoperative patients, the AGA recommends the use of PPIs and H2RAs for the first 6 months following bowel resection when hyper-gastrinemia most commonly occurs. The guidelines do not specify which PPI or H2RA is preferred or recommended dosages. For long-term management of diarrhea or excess fluid losses, the guidelines suggest using loperamide or diphenoxylate (4-16 mg per day) first, followed by codeine sulfate 15–60 mg two to three times per day or opium tincture (dosages not specified). The use of octreotide (100 mcg SQ 3 times per day, 30 minutes prior to meals) is recommended only as a last resort if IVF requirements are greater than 3 L per day [8].

Surgical Guidelines

The Cleveland Clinic published institutional guidelines for the management of intestinal failure in 2010 with updated recommendations in 2016. Dietary recommendations include the liberal use of salt, sipping on 1–2 L of ORS between meals, and a slow reintroduction of soluble fiber from foods and/or supplements as tolerated. The guidelines also suggest considering placement of a nasogastric feeding tube or percutaneous gastrostomy tube (PEG) for continuous enteral feeding in addition to oral intake to enhance nutrient absorption [35]. If dietary manipulation is inadequate and medical therapy is required, the following medications are recommended in no particular order: loperamide 4 times per day (maximum dosage of 16 mg), diphenoxylate-atropine 4 times per day (maximum dosage of 20 mg per day), codeine 4 times per day (maximum dosage 240 mg per day), paregoric 5 mL (containing 2 mg of anhydrous morphine) 4 times per day, and opium tincture 0.5 mL (10 mg/mL) 4 times per day. H2RAs and PPIs are recommended for postoperative high-output states, although no dosage recommendations or routes of administration were discussed.

Nutrition Guidelines

Villafranca et al published a protocol for the management of high-output stomas in 2015 that was shown to be effective in reducing high-enterostomy output. The protocol recommended initial treatment with loperamide 2 mg orally up to 4 times per day. If enterostomy output did not improve, the protocol recommended increasing loperamide to 4 mg four times per day, adding omeprazole 20 mg orally or cholestyramine 4 g twice per day before lunch and dinner if fat malabsorption or steatorrhea is suspected, and lastly the addition of codeine 15–60 mg up to 4 times per day and octreotide 200 mcg per day only if symptoms had not improved after 2 weeks [37].

The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) does not have published guidelines for the management of SBS. In 2016 however, the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) published guidelines on the management of chronic intestinal failure in adults. In patients with an intact colon, ESPEN strongly recommends a diet rich in complex carbohydrates and low in fat and using H2RAs or PPIs to treat hyper-gastrinemia within the first 6 months after intestinal resection particularly in those with greater than 2 L per day of fecal output. The ESPEN guidelines do not include whether to start a PPI or H2RA first, which particular drug in each class to try, or dosage recommendations but state that IV soluble formulations should be considered in those that do not seem to respond to tablets. ESPEN does not recommend the addition of soluble fiber to enhance intestinal absorption or probiotics and glutamine to aid in intestinal rehabilitation. For diarrhea and excessive fecal fluid, the guidelines recommend 4 mg of oral loperamide 30–60 minutes prior to meals, 3 to 4 times per day, as first-line treatment in comparison to codeine phosphate or opium tincture given the risks of dependence and sedation with the latter agents. They report, however, that dosages up to 12–24 mg at one time of loperamide are used in patients with terminal ileum resection and persistently high-output enterostomy [38].

Case Conclusion

The services that were closely involved in this patient’s care were general internal medicine, general surgery, colorectal surgery, and ancillary services, including dietary and wound care. Interestingly, despite persistent high ileostomy output during the patient’s 16-day hospital admission, the gastroenterology service was never consulted. This case illustrates the importance of having a multidisciplinary approach to the care of these complicated patients to ensure that the appropriate medications are ordered based on the individual’s anatomy and that medications are ordered at appropriate dosages and timing intervals to maximize drug efficacy. It is also critical to ensure that nursing staff accurately documents all intake and output so that necessary changes can be made after adequate time is given to assess for a true response. There should be close communication between the primary medical or surgical service with the dietician to ensure the patient is counseled on appropriate dietary intake to help minimize diarrhea and fluid losses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, intestinal failure is a heterogenous group of disease states that often occurs after major intestinal resection and is commonly associated with malabsorption and high output states. High-output enterostomy and diarrhea are the most common etiologies leading to hospital re-admission following enterostomy creation or intestinal resection. These patients have high morbidity and mortality rates, and their conditions are costly to the health care system. Lack of high-quality evidence from RCTs and numerous societal guidelines without clear medication and dietary algorithms and low prevalence of these conditions makes management of these patients by general medical and surgical teams challenging. The proper management of intestinal failure and related complications requires a multidisciplinary approach with involvement from medical, surgical, and ancillary services. We propose a multidisciplinary approach with involvement from medical, surgical, and ancillary services in designed and implementing a protocol using electronic medical record based order sets to simplify and improve the management of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Corresponding author: Jake Hutto, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX 75390-9030, jake.hutto@phhs.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Jeppesen PB. Gut hormones in the treatment of short-bowel syndrome and intestinal failure. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2015;22:14–20.

2. Berry SM, Fischer JE. Classification and pathophysiology of enterocutaneous fistulas. Surg Clin North Am 1996;76:1009–18.

3. Buchman AL, Scolapio J, Fryer J. AGA technical review on short bowel syndrome and intestinal transplantation. Gastroenterology 2003;124:1111–34.

4. de Vries FEE, Reeskamp LF, van Ruler O et al. Systematic review: pharmacotherapy for high-output enterostomies or enteral fistulas. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:266–73.

5. Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001.

6. Woolf GM, Miller C, Kurian R, Jeejeebhoy KN. Nutritional absorption in short bowel syndrome. Evaluation of fluid, calorie, and divalent cation requirements. Dig Dis Sci 1987;32:8–15.

7. Parrish CR, DiBaise JK. Managing the adult patient with short bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2017;13:600–8.

8. American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: short bowel syndrome and intestinal transplantation. Gastroenterology 2003;124:1105–10.

9. Musial F, Enck P, Kalveram KT, Erckenbrecht JF. The effect of loperamide on anorectal function in normal healthy men. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:321–4.

10. Tijtgat GN, Meuwissen SG, Huibregtse K. Loperamide in the symptomatic control of chronic diarrhoea. Double-blind placebo-controlled study. Ann Clin Res 1975;7:325–30.

11. Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K, Dagevos J, van den Ende A. Effect of loperamide on fecal output and composition in well-established ileostomy and ileorectal anastomosis. Am J Dig Dis 1977;22:669–76.

12. Stevens PJ, Dunbar F, Briscoe P. Potential of loperamide oxide in the reduction of ileostomy and colostomy output. Clin Drug Investig 1995;10:158–64.

13. King RF, Norton T, Hill GL. A double-blind crossover study of the effect of loperamide hydrochloride and codeine phosphate on ileostomy output. Aust N Z J Surg 1982;52:121–4.

14. Nightingale JM, Lennard-Jones JE, Walker ER. A patient with jejunostomy liberated from home intravenous therapy after 14 years; contribution of balance studies. Clin Nutr 1992;11:101–5.

15. Nightingale J, Woodward JM. Guidelines for management of patients with a short bowel. Gut 2006;55:iv1–12.

16. Nightingale JM, Lennard-Jones JE, Walker ER, Farthing MJ. Jejunal efflux in short bowel syndrome. Lancet 1990;336:765–8.

17. Go VL, Poley JR, Hofmann AF, Summerskill WH. Disturbances in fat digestion induced by acidic jejunal pH due to gastric hypersecretion in man. Gastroenterology 1970;58:638–46.

18. Windsor CW, Fejfar J, Woodward DA. Gastric secretion after massive small bowel resection. Gut 1969;10:779–86.

19. Williams NS, Evans P, King RF. Gastric acid secretion and gastrin production in the short bowel syndrome. Gut 1985;26:914–9.

20. Jeppesen PB, Staun M, Tjellesen L, Mortensen PB. Effect of intravenous ranitidine and omeprazole on intestinal absorption of water, sodium, and macronutrients in patients with intestinal resection. Gut 1998;43:763–9.

21. Aly A, Bárány F, Kollberg B, et al. Effect of an H2-receptor blocking agent on diarrhoeas after extensive small bowel resection in Crohn’s disease. Acta Med Scand 1980;207:119–22.

22. Kato J, Sakamoto J, Teramukai S, et al. A prospective within-patient comparison clinical trial on the effect of parenteral cimetidine for improvement of fluid secretion and electrolyte balance in patients with short bowel syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1742–6.

23. Jacobsen O, Ladefoged K, Stage JG, Jarnum S. Effects of cimetidine on jejunostomy effluents in patients with severe short-bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 1986;21:824–8.

24. Hofmann AF. The syndrome of ileal disease and the broken enterohepatic circulation: cholerheic enteropathy. Gastroenterology 1967;52:752–7.

25. Buchman AL, Fryer J, Wallin A et al. Clonidine reduces diarrhea and sodium loss in patients with proximal jejunostomy: a controlled study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:487–91.

26. Scholz J, Bause H, Reymann A, Dürig M. Treatment with clonidine in a case of the short bowel syndrome with therapy-refractory diarrhea [ in German]. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 1991;26:265–9.

27. Torres AJ, Landa JI, Moreno-Azcoita M, et al. Somatostatin in the management of gastrointestinal fistulas. A multicenter trial. Arch Surg 1992;127:97–9; discussion 100.

28. Nubiola-Calonge P, Badia JM, Sancho J, et al. Blind evaluation of the effect of octreotide (SMS 201-995), a somatostatin analogue, on small-bowel fistula output. Lancet 1987;2:672–4.

29. Kusuhara K, Kusunoki M, Okamoto T, et al. Reduction of the effluent volume in high-output ileostomy patients by a somatostatin analogue, SMS 201-995. Int J Colorectal Dis 1992;7:202–5.

30. O’Keefe SJ, Peterson ME, Fleming CR. Octreotide as an adjunct to home parenteral nutrition in the management of permanent end-jejunostomy syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1994;18:26–34.

31. Nehra V, Camilleri M, Burton D, et al. An open trial of octreotide long-acting release in the management of short bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1494–8.

32. Sancho JJ, di Costanzo J, Nubiola P, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of early octreotide in patients with postoperative enterocutaneous fistula. Br J Surg 1995;82:638–41.

33. Alberti KG, Christensen NJ, Christensen SE, et al. Inhibition of insulin secretion by somatostatin. Lancet 1973;2:1299–301.

34. Hofmann AF, Poley JR. Role of bile acid malabsorption in pathogenesis of diarrhea and steatorrhea in patients with ileal resection. I. Response to cholestyramine or replacement of dietary long chain triglyceride by medium chain triglyceride. Gastroenterology 1972;62:918–34.

35. Joly F, Dray X, Corcos O, et al. Tube feeding improves intestinal absorption in short bowel syndrome patients. Gastroenterology 2009;136:824–31.

36. Bharadwaj S, Tandon P, Rivas JM, et al. Update on the management of intestinal failure. Cleveland Cleve Clin J Med 2016;83:841–8.

37. Arenas Villafranca JJ, López-Rodríguez C, Abilés J, et al. Protocol for the detection and nutritional management of high-output stomas. Nutr J 2015;14:45.

38. Pironi L, Arends J, Bozzetti F, et al. ESPEN guidelines on chronic intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr 2016;35:247–307.

From the University of Texas Southwestern, Department of Internal Medicine, Dallas, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: To define intestinal failure and associated diseases that often lead to diarrhea and high-output states, and to provide a literature review on the current evidence and practice guidelines for the management of these conditions in the context of a clinical case.

- Methods: Database search on dietary and medical interventions as well as major societal guidelines for the management of intestinal failure and associated conditions.

- Results: Although major societal guidelines exist, the guidelines vary greatly amongst various specialties and are not supported by strong evidence from large randomized controlled trials. The majority of the guidelines recommend consideration of several drug classes, but do not specify medications within the drug class, optimal dose, frequency, mode of administration, and how long to trial a regimen before considering it a failure and adding additional medical therapies.

- Conclusions: Intestinal failure and high-output states affect a very heterogenous population with high morbidity and mortality. This subset of patients should be managed using a multidisciplinary approach involving surgery, gastroenterology, dietetics, internal medicine and ancillary services that include but are not limited to ostomy nurses and home health care. Implementation of a standardized protocol in the electronic medical record including both medical and nutritional therapies may be useful to help optimize efficacy of medications, aid in nutrient absorption, decrease cost, reduce hospital length of stay, and decrease hospital readmissions.

Key words: short bowel syndrome; high-output ostomy; entero-cutaneous fistula; diarrhea; malnutrition.

Intestinal failure includes but is not limited to short bowel syndrome (SBS), high-output enterostomy, and high-output related to entero-cutaneous fistulas (ECF). These conditions are unfortunate complications after major abdominal surgery requiring extensive intestinal resection leading to structural SBS. Absorption of macronutrients and micronutrients is most dependent on the length and specific segment of remaining intact small intestine [1]. The normal small intestine length varies greatly but ranges from 300 to 800 cm, while in those with structural SBS the typical length is 200 cm or less [2,3]. Certain malabsorptive enteropathies and severe intestinal dysmotility conditions may manifest as functional SBS as well. Factors that influence whether an individual will develop functional SBS despite having sufficient small intestinal absorptive area include the degree of jejunal absorptive efficacy and the ability to overcompensate with enough oral caloric intake despite high fecal energy losses, also known as hyperphagia [4].

Pathophysiology

Maintenance of normal bodily functions and homeostasis is dependent on sufficient intestinal absorption of essential macronutrients, micronutrients, and fluids. The hallmark of intestinal failure is based on the presence of decreased small bowel absorptive surface area and subsequent increased losses of key solutes and fluids [1]. Intestinal failure is a broad term that is comprised of 3 distinct phenotypes. The 3 functional classifications of intestinal failure include the following:

- Type 1. Acute intestinal failure is generally self-limiting, occurs after abdominal surgery, and typically lasts less than 28 days.

- Type 2. Subacute intestinal failure frequently occurs in septic, stressed, or metabolically unstable patients and may last up to several months.

- Type 3. Chronic intestinal failure occurs due to a chronic condition that generally requires indefinite parenteral nutrition (PN) [1,3,4].

SBS and enterostomy formation are often associated with excessive diarrhea, such that it is the most common etiology for postoperative readmissions. The definition of “high-output” varies amongst studies, but output is generally considered to be abnormally high if it is greater than 500 mL per 24 hours in ECFs and greater than 1500 mL per 24 hours for enterostomies. There is significant variability from patient to patient, as output largely depends on length of remaining bowel [2,4].

Epidemiology

SBS, high-output enterostomy, and high-output from ECFs comprise a wide spectrum of underlying disease states, including but not limited to inflammatory bowel disease, post-surgical fistula formation, intestinal ischemia, intestinal atresia, radiation enteritis, abdominal trauma, and intussusception [5]. Due to the absence of a United States registry of patients with intestinal failure, the prevalence of these conditions is difficult to ascertain. Most estimations are made using registries for patients on total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The Crohns and Colitis Foundation of America estimates 10,000 to 20,000 people suffer from SBS in the United States. This heterogenous patient population has significant morbidity and mortality for dehydration related to these high-output states. While these conditions are considered rare, they are relatively costly to the health care system. These patients are commonly managed by numerous medical and surgical services, including internal medicine, gastroenterology, surgery, dietitians, wound care nurses, and home health agencies. Management strategies differ amongst these specialties and between professional societies, which makes treatment strategies highly variable and perplexing to providers taking care of this patient population. Furthermore, most of the published guidelines are based on expert opinion and lack high-quality clinical evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Effectively treating SBS and reducing excess enterostomy output leads to reduced rates of dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, initiation of PN, weight loss and ultimately a reduction in malnutrition. Developing hospital-wide management protocols in the electronic medical record for this heterogenous condition may lead to less complications, fewer hospitalizations, and an improved quality of life for these patients.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 72-year-old man with history of rectal adenocarcinoma stage T4bN2 status post low anterior resection (LAR) with diverting loop ileostomy and neoadjuvant chemoradiation presented to the hospital with a 3-day history of nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and productive cough.

Additional History

On further questioning, the patient also reported odynophagia and dysphagia related to thrush. Because of his decreased oral intake, he stopped taking his usual insulin regimen prior to admission. His cancer treatment course was notable for a LAR with diverting loop ileostomy which was performed 5 months prior. He had also completed 3 out of 8 cycles of capecitabine and oxaliplatin-based therapy 2 weeks prior to this presentation.

Physical Examination

Significant physical examination findings included dry mucous membranes, oropharyngeal candidiasis, tachycardia, clear lungs, hypoactive bowel sounds, nontender, non-distended abdomen, and a right lower abdominal ileostomy bag with semi-formed stool.

Laboratory test results were pertinent for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with an anion gap of 33, lactic acidosis, acute kidney injury (creatinine 2.7 mg/dL from a baseline of 1.0) and blood glucose of 1059 mg/dL. Remainder of complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were unremarkable.

Hospital Course

The patient was treated for oropharyngeal candidiasis with fluconazole, started on an insulin drip and given intravenous fluids (IVFs) with subsequent resolution of DKA. Once the DKA resolved, his diet was advanced to a mechanical soft, moderate calorie, consistent carbohydrate diet (2000 calories allowed daily with all foods chopped, pureed or cooked, and all meals containing nearly equal amounts of carbohydrates). He was also given Boost supplementation 3 times per day, and daily weights were recorded while assessing for fluid losses. However, during his hospital course the patient developed increasing ileostomy output ranging from 2.7 to 6.5 L per day that only improved when he stopped eating by mouth (NPO).

What conditions should be evaluated prior to starting therapy for high-output enterostomy/diarrhea from either functional or structural SBS?

Prior to starting anti-diarrheal and anti-secretory therapy, infectious and metabolic etiologies for high-enterostomy output should be ruled out. Depending on the patient’s risk factors (eg, recent sick contacts, travel) and whether they are immunocompetent versus immunosuppressed, infectious studies should be obtained. In this patient, Clostridium difficile, stool culture, Giardia antigen, stool ova and parasites were all negative. Additional metabolic labs including thyroid-stimulating hormone, fecal elastase, and fecal fat were obtained and were all within normal limits. In this particular scenario, fecal fat was obtained while he was NPO. Testing for fat malabsorption and pancreatic insufficiency in a patient that is consuming less than 100 grams of fat per day can result in a false-negative outcome, however, and was not an appropriate test in this patient.

Hospital Course Continued

Once infectious etiologies were ruled out, the patient was started on anti-diarrheal medication consisting of loperamide 2 mg every 6 hours and oral pantoprazole 40 mg once per day. The primary internal medicine team speculated that the Boost supplementation may be contributing to the diarrhea because of its hyperosmolar concentration and wanted to discontinue it, but because the patient had protein-calorie malnutrition the dietician recommended continuing Boost supplementation. The primary internal medicine team also encouraged the patient to drink Gatorade with each meal with the approval from the dietician.

What are key dietary recommendations to help reduce high-output enterostomy/diarrhea?

Dietary recommendations are often quite variable depending on the intestinal anatomy (specifically, whether the colon is intact or absent), comorbidities such as renal disease, and severity of fluid and nutrient loses. This patient has the majority of his colon remaining; however, fluid and nutrients are being diverted away from his colon because he has a loop ileostomy. To reduce enterostomy output, it is generally recommended that liquids be consumed separately from solids, and that oral rehydration solutions (ORS) should replace most hyperosmolar and hypoosmolar liquids. Although these recommendations are commonly used, there is sparse data to suggest separating liquids from solids in a medically stable patient with SBS is indeed necessary [6]. In our patient, however, because he has not yet reached medical stability, it would be reasonable to separate the consumption of liquids from solids. The solid component of a SBS diet should consist mainly of protein and carbohydrates, with limited intake of simple sugars and sugar alcohols. If the colon remains intact, it is particularly important to limit fats to less than 30% of the daily caloric intake, to consume a low-oxalate diet, supplement with oral calcium to reduce the risk of calcium-oxalate nephrolithiasis, and increase dietary fiber intake as tolerated. Soluble fiber is fermented by colonic bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and serve as an additional energy source [7,8]. Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are good sources of fat because the body is able to absorb them into the bloodstream without the use of intestinal lymphatics, which may be damaged or absent in those with intestinal failure. For this particular patient, he would have benefitted from initiation of ORS and counseled to sip on it throughout the day while limiting liquid consumption during meals. He should have also been advised to limit plain Gatorade and Boost as they are both hyperosmolar liquid formulations and can worsen diarrhea. If the patient was unable to tolerate the taste of standard ORS formulations, or the hospital did not have any ORS on formulary, sugar, salt and water at specific amounts may be added to create a homemade ORS. In summary, this patient would have likely tolerated protein in solid form better than liquid protein supplementation.

Hospital Course Continued

The patient continued to have greater than 5 L of output from the ileostomy per day, so the following day the primary team increased the loperamide from 2 mg every 6 hours to 4 mg every 6 hours, added 2 tabs of diphenoxylate-atropine every 8 hours, and made the patient NPO. He continued to require IVFs and frequent electrolyte repletion because of the significant ongoing gastrointestinal losses.

What is the recommended first-line medical therapy for high-output enterostomy/diarrhea?