User login

CMS offering educational webinars on MACRA

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

Enhanced recovery pathways in gynecology

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Frailty stratifies pediatric liver disease severity

MONTREAL – A newly devised measurement of frailty in children effectively determined the severity of liver disease in pediatric patients and might serve as a useful, independent predictor of outcomes following liver transplantations in children and adolescents.

The adapted pediatric frailty assessment formula is a “very valid, feasible, and valuable tool” for assessing children with chronic liver disease, Eberhard Lurz, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. “Frailty captures an additional marker of ill health that is independent of the MELD-Na [Model for End-Stage Liver Disease–Na] and PELD,” [Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease] said Dr. Lurz, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

The idea of frailty assessment of children with liver disease sprang from a 2014 report that showed a five-item frailty index could predict mortality in adults with liver disease who were listed for liver transplantation and that this predictive power was independent of the patients’ MELD scores (Am J Transplant. 2014 Aug;14[8]:1870-9). That study used a five-item frailty index developed for adults (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56[3]:M146-57).

Dr. Lurz came up with a pediatric version of this frailty score using pediatric-oriented measures for each of the five items. To measure exhaustion he used the PedsQL (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory) Multidimensional Fatigue Scale; for slowness he used a 6-minute walk test; for weakness he measured grip strength; for shrinkage he measured triceps skinfold thickness; and for diminished activity he used an age-appropriate physical activity questionnaire. He prespecified that a patient’s scores for each of these five measures are calculated by comparing their test results against age-specific norms. A patient with a value that fell more than one standard deviation below the normal range scores one point for the item and those with values more than two standard deviations below the normal range score two points. Hence the maximum score for all five items is 10.

Researchers at the collaborating centers completed full assessments for 71 of 85 pediatric patients with chronic liver disease in their clinics, and each full assessment took a median of 60 minutes. The patients ranged from 8-16 years old, with an average age of 13. The cohort included 36 patients with compensated chronic liver disease (CCLD) and 35 with end-stage liver disease (ESLD) who were listed for liver transplantation.

The median frailty score of the CCLD patients was 3 and the median score for those with ESLD was 5, a statistically significant difference that was largely driven by between-group differences in fatigue scores and physical activity scores. A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis by area under the curve showed that the frailty score accounted for 83% of the difference between patients with CCLD and ESLD, comparable to the distinguishing power of the MELD-Na score. Using a cutoff on the score of 6 or greater identified patients with ESLD with 47% sensitivity and 98% specificity, and this diagnostic capability was independent of a patient’s MELD-Na or PELD score.

The five elements that contribute to this pediatric frailty score could be the focus for targeted interventions to improve the outcomes of patients scheduled to undergo liver transplantation, Dr. Lurz said.

Dr. Lurz had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – A newly devised measurement of frailty in children effectively determined the severity of liver disease in pediatric patients and might serve as a useful, independent predictor of outcomes following liver transplantations in children and adolescents.

The adapted pediatric frailty assessment formula is a “very valid, feasible, and valuable tool” for assessing children with chronic liver disease, Eberhard Lurz, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. “Frailty captures an additional marker of ill health that is independent of the MELD-Na [Model for End-Stage Liver Disease–Na] and PELD,” [Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease] said Dr. Lurz, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

The idea of frailty assessment of children with liver disease sprang from a 2014 report that showed a five-item frailty index could predict mortality in adults with liver disease who were listed for liver transplantation and that this predictive power was independent of the patients’ MELD scores (Am J Transplant. 2014 Aug;14[8]:1870-9). That study used a five-item frailty index developed for adults (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56[3]:M146-57).

Dr. Lurz came up with a pediatric version of this frailty score using pediatric-oriented measures for each of the five items. To measure exhaustion he used the PedsQL (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory) Multidimensional Fatigue Scale; for slowness he used a 6-minute walk test; for weakness he measured grip strength; for shrinkage he measured triceps skinfold thickness; and for diminished activity he used an age-appropriate physical activity questionnaire. He prespecified that a patient’s scores for each of these five measures are calculated by comparing their test results against age-specific norms. A patient with a value that fell more than one standard deviation below the normal range scores one point for the item and those with values more than two standard deviations below the normal range score two points. Hence the maximum score for all five items is 10.

Researchers at the collaborating centers completed full assessments for 71 of 85 pediatric patients with chronic liver disease in their clinics, and each full assessment took a median of 60 minutes. The patients ranged from 8-16 years old, with an average age of 13. The cohort included 36 patients with compensated chronic liver disease (CCLD) and 35 with end-stage liver disease (ESLD) who were listed for liver transplantation.

The median frailty score of the CCLD patients was 3 and the median score for those with ESLD was 5, a statistically significant difference that was largely driven by between-group differences in fatigue scores and physical activity scores. A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis by area under the curve showed that the frailty score accounted for 83% of the difference between patients with CCLD and ESLD, comparable to the distinguishing power of the MELD-Na score. Using a cutoff on the score of 6 or greater identified patients with ESLD with 47% sensitivity and 98% specificity, and this diagnostic capability was independent of a patient’s MELD-Na or PELD score.

The five elements that contribute to this pediatric frailty score could be the focus for targeted interventions to improve the outcomes of patients scheduled to undergo liver transplantation, Dr. Lurz said.

Dr. Lurz had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – A newly devised measurement of frailty in children effectively determined the severity of liver disease in pediatric patients and might serve as a useful, independent predictor of outcomes following liver transplantations in children and adolescents.

The adapted pediatric frailty assessment formula is a “very valid, feasible, and valuable tool” for assessing children with chronic liver disease, Eberhard Lurz, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. “Frailty captures an additional marker of ill health that is independent of the MELD-Na [Model for End-Stage Liver Disease–Na] and PELD,” [Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease] said Dr. Lurz, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

The idea of frailty assessment of children with liver disease sprang from a 2014 report that showed a five-item frailty index could predict mortality in adults with liver disease who were listed for liver transplantation and that this predictive power was independent of the patients’ MELD scores (Am J Transplant. 2014 Aug;14[8]:1870-9). That study used a five-item frailty index developed for adults (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56[3]:M146-57).

Dr. Lurz came up with a pediatric version of this frailty score using pediatric-oriented measures for each of the five items. To measure exhaustion he used the PedsQL (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory) Multidimensional Fatigue Scale; for slowness he used a 6-minute walk test; for weakness he measured grip strength; for shrinkage he measured triceps skinfold thickness; and for diminished activity he used an age-appropriate physical activity questionnaire. He prespecified that a patient’s scores for each of these five measures are calculated by comparing their test results against age-specific norms. A patient with a value that fell more than one standard deviation below the normal range scores one point for the item and those with values more than two standard deviations below the normal range score two points. Hence the maximum score for all five items is 10.

Researchers at the collaborating centers completed full assessments for 71 of 85 pediatric patients with chronic liver disease in their clinics, and each full assessment took a median of 60 minutes. The patients ranged from 8-16 years old, with an average age of 13. The cohort included 36 patients with compensated chronic liver disease (CCLD) and 35 with end-stage liver disease (ESLD) who were listed for liver transplantation.

The median frailty score of the CCLD patients was 3 and the median score for those with ESLD was 5, a statistically significant difference that was largely driven by between-group differences in fatigue scores and physical activity scores. A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis by area under the curve showed that the frailty score accounted for 83% of the difference between patients with CCLD and ESLD, comparable to the distinguishing power of the MELD-Na score. Using a cutoff on the score of 6 or greater identified patients with ESLD with 47% sensitivity and 98% specificity, and this diagnostic capability was independent of a patient’s MELD-Na or PELD score.

The five elements that contribute to this pediatric frailty score could be the focus for targeted interventions to improve the outcomes of patients scheduled to undergo liver transplantation, Dr. Lurz said.

Dr. Lurz had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT WCPGHAN 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The pediatric frailty score identified patients with end-stage liver disease with sensitivity of 47% and specificity of 98%.

Data source: A series of 71 pediatric patients with liver disease compiled from 17 U.S. and Canadian centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Lurz had no relevant financial disclosures.

Laparoscopy comparable to open staging for uterine papillary serous cancer

BOSTON – Laparoscopic staging of patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma is a safe alternative to open staging and may offer some advantages, according to findings presented at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

“Traditionally, serous papillary cancer has been treated different than the other endometrial cancers, the reason being is that it tends to behave more like ovarian cancer,” Jeanette Voice, MD, of Richmond University Medical Center in Staten Island, N.Y., said at the meeting, which was held by the Society for Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. “Patients with serous papillary cancer tend to be older [so] these patients may benefit from a less invasive surgical approach.”

Dr. Voice and her coinvestigators conducted an 8-year retrospective study of laparoscopic and open-staged cases treated from March 2007 through May 2015. Initially, 59 patients with pathology-confirmed uterine papillary serous carcinoma were identified over that time period, and were divided into two cohorts: one receiving open surgery (37 patients) and one receiving laparoscopic surgery (22 patients).

Median age, body mass index, and prior abdominal surgery rate were not significantly different between the two cohorts.

In terms of intraoperative factors, median operative times for the open and laparoscopic cohorts were similar: 196 minutes versus 216 minutes, respectively (P = .561). Similarly, the number of pelvic lymph node dissections and rate of omentectomy were also not significantly different: 18 nodes (open) versus 16 nodes (laparoscopic) (P = .96), and 100% (open) versus 91% (laparoscopic) (P = .08).

However, laparoscopic patients had more favorable median estimated blood loss (310 mL versus 175 mL, P = .048) and shorter hospital stays (4 days versus 1 day, P less than .042).

Laparoscopic patients also achieved more robust debulking to zero centimeter residual disease, with 90.5% of patients achieving it versus 65.7% of those in the open surgery cohort, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .1).

In terms of postoperative adjuvant therapy – brachytherapy, external beam radiation, and chemotherapy – there were no significant differences in outcomes between the two cohorts. Recurrence rates were also similar, with nine recurrences in the open cohort and eight recurrences in the laparoscopic cohort. The estimated 36-month progression-free survival rates were “almost identical,” with 55.3% in the open cohort versus 53.3% in the laparoscopic (P = .727), according to Dr. Voice.

Postoperative complications were more common in the open surgery cohort (29.7%), compared with 13.6% in the laparoscopic cohort, but no statistically significant difference was found between them (P = .16).

Dr. Voice did not report information on financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Laparoscopic staging of patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma is a safe alternative to open staging and may offer some advantages, according to findings presented at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

“Traditionally, serous papillary cancer has been treated different than the other endometrial cancers, the reason being is that it tends to behave more like ovarian cancer,” Jeanette Voice, MD, of Richmond University Medical Center in Staten Island, N.Y., said at the meeting, which was held by the Society for Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. “Patients with serous papillary cancer tend to be older [so] these patients may benefit from a less invasive surgical approach.”

Dr. Voice and her coinvestigators conducted an 8-year retrospective study of laparoscopic and open-staged cases treated from March 2007 through May 2015. Initially, 59 patients with pathology-confirmed uterine papillary serous carcinoma were identified over that time period, and were divided into two cohorts: one receiving open surgery (37 patients) and one receiving laparoscopic surgery (22 patients).

Median age, body mass index, and prior abdominal surgery rate were not significantly different between the two cohorts.

In terms of intraoperative factors, median operative times for the open and laparoscopic cohorts were similar: 196 minutes versus 216 minutes, respectively (P = .561). Similarly, the number of pelvic lymph node dissections and rate of omentectomy were also not significantly different: 18 nodes (open) versus 16 nodes (laparoscopic) (P = .96), and 100% (open) versus 91% (laparoscopic) (P = .08).

However, laparoscopic patients had more favorable median estimated blood loss (310 mL versus 175 mL, P = .048) and shorter hospital stays (4 days versus 1 day, P less than .042).

Laparoscopic patients also achieved more robust debulking to zero centimeter residual disease, with 90.5% of patients achieving it versus 65.7% of those in the open surgery cohort, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .1).

In terms of postoperative adjuvant therapy – brachytherapy, external beam radiation, and chemotherapy – there were no significant differences in outcomes between the two cohorts. Recurrence rates were also similar, with nine recurrences in the open cohort and eight recurrences in the laparoscopic cohort. The estimated 36-month progression-free survival rates were “almost identical,” with 55.3% in the open cohort versus 53.3% in the laparoscopic (P = .727), according to Dr. Voice.

Postoperative complications were more common in the open surgery cohort (29.7%), compared with 13.6% in the laparoscopic cohort, but no statistically significant difference was found between them (P = .16).

Dr. Voice did not report information on financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Laparoscopic staging of patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma is a safe alternative to open staging and may offer some advantages, according to findings presented at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

“Traditionally, serous papillary cancer has been treated different than the other endometrial cancers, the reason being is that it tends to behave more like ovarian cancer,” Jeanette Voice, MD, of Richmond University Medical Center in Staten Island, N.Y., said at the meeting, which was held by the Society for Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. “Patients with serous papillary cancer tend to be older [so] these patients may benefit from a less invasive surgical approach.”

Dr. Voice and her coinvestigators conducted an 8-year retrospective study of laparoscopic and open-staged cases treated from March 2007 through May 2015. Initially, 59 patients with pathology-confirmed uterine papillary serous carcinoma were identified over that time period, and were divided into two cohorts: one receiving open surgery (37 patients) and one receiving laparoscopic surgery (22 patients).

Median age, body mass index, and prior abdominal surgery rate were not significantly different between the two cohorts.

In terms of intraoperative factors, median operative times for the open and laparoscopic cohorts were similar: 196 minutes versus 216 minutes, respectively (P = .561). Similarly, the number of pelvic lymph node dissections and rate of omentectomy were also not significantly different: 18 nodes (open) versus 16 nodes (laparoscopic) (P = .96), and 100% (open) versus 91% (laparoscopic) (P = .08).

However, laparoscopic patients had more favorable median estimated blood loss (310 mL versus 175 mL, P = .048) and shorter hospital stays (4 days versus 1 day, P less than .042).

Laparoscopic patients also achieved more robust debulking to zero centimeter residual disease, with 90.5% of patients achieving it versus 65.7% of those in the open surgery cohort, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .1).

In terms of postoperative adjuvant therapy – brachytherapy, external beam radiation, and chemotherapy – there were no significant differences in outcomes between the two cohorts. Recurrence rates were also similar, with nine recurrences in the open cohort and eight recurrences in the laparoscopic cohort. The estimated 36-month progression-free survival rates were “almost identical,” with 55.3% in the open cohort versus 53.3% in the laparoscopic (P = .727), according to Dr. Voice.

Postoperative complications were more common in the open surgery cohort (29.7%), compared with 13.6% in the laparoscopic cohort, but no statistically significant difference was found between them (P = .16).

Dr. Voice did not report information on financial disclosures.

AT MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY WEEK

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Laparoscopic patients had lower median estimated blood loss (310 mL v. 175 mL, P = .048) and shorter hospital stays (4 days v. 1 day, P less than .042).

Data source: Retrospective review of data on 59 open and laparoscopic patients over 8 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Voice did not report information on financial disclosures.

Registry helps track pelvic organ prolapse outcomes in the U.S.

DENVER – Catherine Bradley, MD, said during a presentation at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

“This is a unique collaborative registry created in response to U.S. industry requirements. There are many benefits to using this approach, but also many challenges. It’s a work in progress,” said Dr. Bradley, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City. She chairs the American Urogynecologic Society Research Council, which helps oversee the registry.

The purpose of the PFDR is to fulfill requirements from the Food and Drug Administration for postmarketing studies of the vaginal mesh procedure, to give surgeons a pelvic organ prolapse treatment database to track individual and aggregate outcomes for research and quality improvement purposes, and to create a framework for future clinical studies, according to Dr. Bradley.

As such, the PFDR comprises two interrelated registries, Dr. Bradley noted. The PFDR-I includes industry-sponsored studies, while the PFDR-R is the independent research registry of the American Urogynecologic Society. The PFDR previously included a third quality improvement registry, which in January 2016 was moved to a separate platform called AQUIRE.

The PFDR-I is tracking 1,620 patients who underwent 1,386 procedures for pelvic organ prolapse as part of four studies sponsored by three manufacturers, according to Dr. Bradley. The PFDR-R, for its part, has eight active sites and has enrolled 179 patients with pelvic organ prolapse, 154 of whom underwent mesh surgery and 25 of whom received vaginal pessaries, she said.

The PFDR-R is voluntary and has faced some barriers in the 10 months since its launch, Dr. Bradley said. Participation increases workload for physicians as well as data entry personnel, and patients must provide informed consent to be entered into the registry. But the benefits of participating are also substantial, she emphasized. The PFDR-R will enable surgeons to track their own outcomes in terms of caseload, anatomic outcomes, symptoms and quality of life, and adverse events. They can download their own data, compare their outcomes to others as part of highly granular benchmarking initiatives, and propose and conduct studies of the entire registry.

The PFDR is supported by ACell, ASTORA Women’s Health, Boston Scientific, and Coloplast. Dr. Bradley reported having no conflicts of interest.

DENVER – Catherine Bradley, MD, said during a presentation at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

“This is a unique collaborative registry created in response to U.S. industry requirements. There are many benefits to using this approach, but also many challenges. It’s a work in progress,” said Dr. Bradley, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City. She chairs the American Urogynecologic Society Research Council, which helps oversee the registry.

The purpose of the PFDR is to fulfill requirements from the Food and Drug Administration for postmarketing studies of the vaginal mesh procedure, to give surgeons a pelvic organ prolapse treatment database to track individual and aggregate outcomes for research and quality improvement purposes, and to create a framework for future clinical studies, according to Dr. Bradley.

As such, the PFDR comprises two interrelated registries, Dr. Bradley noted. The PFDR-I includes industry-sponsored studies, while the PFDR-R is the independent research registry of the American Urogynecologic Society. The PFDR previously included a third quality improvement registry, which in January 2016 was moved to a separate platform called AQUIRE.

The PFDR-I is tracking 1,620 patients who underwent 1,386 procedures for pelvic organ prolapse as part of four studies sponsored by three manufacturers, according to Dr. Bradley. The PFDR-R, for its part, has eight active sites and has enrolled 179 patients with pelvic organ prolapse, 154 of whom underwent mesh surgery and 25 of whom received vaginal pessaries, she said.

The PFDR-R is voluntary and has faced some barriers in the 10 months since its launch, Dr. Bradley said. Participation increases workload for physicians as well as data entry personnel, and patients must provide informed consent to be entered into the registry. But the benefits of participating are also substantial, she emphasized. The PFDR-R will enable surgeons to track their own outcomes in terms of caseload, anatomic outcomes, symptoms and quality of life, and adverse events. They can download their own data, compare their outcomes to others as part of highly granular benchmarking initiatives, and propose and conduct studies of the entire registry.

The PFDR is supported by ACell, ASTORA Women’s Health, Boston Scientific, and Coloplast. Dr. Bradley reported having no conflicts of interest.

DENVER – Catherine Bradley, MD, said during a presentation at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

“This is a unique collaborative registry created in response to U.S. industry requirements. There are many benefits to using this approach, but also many challenges. It’s a work in progress,” said Dr. Bradley, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City. She chairs the American Urogynecologic Society Research Council, which helps oversee the registry.

The purpose of the PFDR is to fulfill requirements from the Food and Drug Administration for postmarketing studies of the vaginal mesh procedure, to give surgeons a pelvic organ prolapse treatment database to track individual and aggregate outcomes for research and quality improvement purposes, and to create a framework for future clinical studies, according to Dr. Bradley.

As such, the PFDR comprises two interrelated registries, Dr. Bradley noted. The PFDR-I includes industry-sponsored studies, while the PFDR-R is the independent research registry of the American Urogynecologic Society. The PFDR previously included a third quality improvement registry, which in January 2016 was moved to a separate platform called AQUIRE.

The PFDR-I is tracking 1,620 patients who underwent 1,386 procedures for pelvic organ prolapse as part of four studies sponsored by three manufacturers, according to Dr. Bradley. The PFDR-R, for its part, has eight active sites and has enrolled 179 patients with pelvic organ prolapse, 154 of whom underwent mesh surgery and 25 of whom received vaginal pessaries, she said.

The PFDR-R is voluntary and has faced some barriers in the 10 months since its launch, Dr. Bradley said. Participation increases workload for physicians as well as data entry personnel, and patients must provide informed consent to be entered into the registry. But the benefits of participating are also substantial, she emphasized. The PFDR-R will enable surgeons to track their own outcomes in terms of caseload, anatomic outcomes, symptoms and quality of life, and adverse events. They can download their own data, compare their outcomes to others as part of highly granular benchmarking initiatives, and propose and conduct studies of the entire registry.

The PFDR is supported by ACell, ASTORA Women’s Health, Boston Scientific, and Coloplast. Dr. Bradley reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT PFD WEEK 2016

No rise in complications with concomitant gynecologic cancer, PFD surgery

DENVER – Concomitantly treating pelvic floor disorders during surgery for gynecologic cancer does not increase the risk of postoperative complications, according to an analysis of 4 years of data from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Among 23,501 surgical gynecologic cancer patients, 556 (2.4%) underwent concomitant surgery for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence, Katarzyna Bochenska, MD, reported in a poster at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society. This subgroup had similar 30-day rates of reoperation, venous thromboembolism, and infectious, pulmonary, and cardiac complications as patients who had surgery only for gynecologic cancer, reported Dr. Bochenska and her associates at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Urinary incontinence and symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse often accompany gynecologic cancer, the researchers noted. In one study, more than half of women with gynecologic cancer reported urinary incontinence, while 11% described feeling a bulge of tissue from their vaginas (Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Nov;122[5]:976-80). But few studies have examined outcomes after concomitant surgery for pelvic floor disorders and gynecologic cancer, according to the researchers.

In the current study, the Northwestern University researchers used postoperative ICD-9 codes to identify patients in the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) who underwent surgery for uterine, cervical, ovarian, or vulvar or vaginal cancer between 2010 and 2014. Most patients had uterine or ovarian cancer, while the most common pelvic floor disorder procedures included anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy, laparoscopic colpopexy, and midurethral slings.

None of the complications studied differed significantly between the groups. Rates of 30-day reoperation were 1.1% among concomitant surgery patients and 2.3% among patients who underwent only cancer surgery (P = .09). Rates of procedure-related infections such as sepsis, deep wound infections, and abscesses also were similar between groups (3.1% and 3.9%, respectively), as were rates of postoperative urinary tract infections (1.8% and 3.2%), pulmonary complications (0.7% and 1.3%), and cardiac complications (0.2% and 0.4%), with all P-values exceeding .05.

Patients who underwent concomitant surgery for pelvic floor disorders were an average of about 3.5 years older than other patients, but otherwise resembled them in term of body mass index and prevalence of comorbidities, such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension.

“Our data suggest that serious postoperative complication rates are not increased in this population,” the researchers concluded. “Therefore, gynecologic surgeons should consider offering concomitant treatment for pelvic floor symptoms at the time of gynecologic cancer surgery.”

Dr. Bochenska and her associates did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

DENVER – Concomitantly treating pelvic floor disorders during surgery for gynecologic cancer does not increase the risk of postoperative complications, according to an analysis of 4 years of data from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Among 23,501 surgical gynecologic cancer patients, 556 (2.4%) underwent concomitant surgery for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence, Katarzyna Bochenska, MD, reported in a poster at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society. This subgroup had similar 30-day rates of reoperation, venous thromboembolism, and infectious, pulmonary, and cardiac complications as patients who had surgery only for gynecologic cancer, reported Dr. Bochenska and her associates at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Urinary incontinence and symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse often accompany gynecologic cancer, the researchers noted. In one study, more than half of women with gynecologic cancer reported urinary incontinence, while 11% described feeling a bulge of tissue from their vaginas (Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Nov;122[5]:976-80). But few studies have examined outcomes after concomitant surgery for pelvic floor disorders and gynecologic cancer, according to the researchers.

In the current study, the Northwestern University researchers used postoperative ICD-9 codes to identify patients in the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) who underwent surgery for uterine, cervical, ovarian, or vulvar or vaginal cancer between 2010 and 2014. Most patients had uterine or ovarian cancer, while the most common pelvic floor disorder procedures included anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy, laparoscopic colpopexy, and midurethral slings.

None of the complications studied differed significantly between the groups. Rates of 30-day reoperation were 1.1% among concomitant surgery patients and 2.3% among patients who underwent only cancer surgery (P = .09). Rates of procedure-related infections such as sepsis, deep wound infections, and abscesses also were similar between groups (3.1% and 3.9%, respectively), as were rates of postoperative urinary tract infections (1.8% and 3.2%), pulmonary complications (0.7% and 1.3%), and cardiac complications (0.2% and 0.4%), with all P-values exceeding .05.

Patients who underwent concomitant surgery for pelvic floor disorders were an average of about 3.5 years older than other patients, but otherwise resembled them in term of body mass index and prevalence of comorbidities, such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension.

“Our data suggest that serious postoperative complication rates are not increased in this population,” the researchers concluded. “Therefore, gynecologic surgeons should consider offering concomitant treatment for pelvic floor symptoms at the time of gynecologic cancer surgery.”

Dr. Bochenska and her associates did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

DENVER – Concomitantly treating pelvic floor disorders during surgery for gynecologic cancer does not increase the risk of postoperative complications, according to an analysis of 4 years of data from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Among 23,501 surgical gynecologic cancer patients, 556 (2.4%) underwent concomitant surgery for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence, Katarzyna Bochenska, MD, reported in a poster at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society. This subgroup had similar 30-day rates of reoperation, venous thromboembolism, and infectious, pulmonary, and cardiac complications as patients who had surgery only for gynecologic cancer, reported Dr. Bochenska and her associates at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Urinary incontinence and symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse often accompany gynecologic cancer, the researchers noted. In one study, more than half of women with gynecologic cancer reported urinary incontinence, while 11% described feeling a bulge of tissue from their vaginas (Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Nov;122[5]:976-80). But few studies have examined outcomes after concomitant surgery for pelvic floor disorders and gynecologic cancer, according to the researchers.

In the current study, the Northwestern University researchers used postoperative ICD-9 codes to identify patients in the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) who underwent surgery for uterine, cervical, ovarian, or vulvar or vaginal cancer between 2010 and 2014. Most patients had uterine or ovarian cancer, while the most common pelvic floor disorder procedures included anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy, laparoscopic colpopexy, and midurethral slings.

None of the complications studied differed significantly between the groups. Rates of 30-day reoperation were 1.1% among concomitant surgery patients and 2.3% among patients who underwent only cancer surgery (P = .09). Rates of procedure-related infections such as sepsis, deep wound infections, and abscesses also were similar between groups (3.1% and 3.9%, respectively), as were rates of postoperative urinary tract infections (1.8% and 3.2%), pulmonary complications (0.7% and 1.3%), and cardiac complications (0.2% and 0.4%), with all P-values exceeding .05.

Patients who underwent concomitant surgery for pelvic floor disorders were an average of about 3.5 years older than other patients, but otherwise resembled them in term of body mass index and prevalence of comorbidities, such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension.

“Our data suggest that serious postoperative complication rates are not increased in this population,” the researchers concluded. “Therefore, gynecologic surgeons should consider offering concomitant treatment for pelvic floor symptoms at the time of gynecologic cancer surgery.”

Dr. Bochenska and her associates did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

AT PFD WEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Women who underwent concomitant surgeries had similar rates of infectious, pulmonary, and cardiac complications as those who underwent surgery only for gynecologic cancer, with all P-values exceeding .05.

Data source: A study of 23,501 gynecologic cancer patients in the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program dataset.

Disclosures: Dr. Bochenska and her associates did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

POP severity not linked to risk of de novo stress urinary incontinence

DENVER – Surgical correction of severe pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no more likely to lead to stress urinary incontinence than is correction of less severe POP, suggest findings from a retrospective study of 206 patients at a tertiary care center.

But a baseline complaint of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) prior to surgery, despite a negative SUI evaluation, was associated with an increased risk, Alexandriah Alas, MD, and her colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston wrote in a poster presented at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

“We recommend counseling patients with a negative evaluation that there is up to a 10.6% risk of developing de novo SUI,” the researchers wrote.

Past studies have linked surgical correction of POP with a 16%-51% increase in risk of de novo SUI, but have not examined whether severe prolapse adds to that risk. The researchers reviewed records from patients who underwent surgical POP correction at their center between 2003 and 2013, excluding those with objective evidence of SUI at baseline or a history of incontinence surgery. They included patients with a baseline subjective complaint of SUI, as long as it was not the primary presenting complaint.

A total of 48 (23%) patients had massive POP – that is, a POP-Q score of at least 3 at points Ba, Bp, or C – and 158 patients had less massive POP, the researchers wrote. In all, 22 patients (10.6%) developed de novo SUI. Postsurgical rates of de novo SUI were 12.5% among women with massive POP and 10.6% among women with less severe POP (P = .6).

Women with massive POP tended to be older and had a higher incidence of hypertension than those with less severe POP. After controlling for these differences, a baseline complaint of SUI was the strongest predictor of de novo SUI, increasing the odds of this outcome more than fivefold (adjusted odds ratio, 5.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-23.9). Two other factors trended toward statistical significance in this multivariable model – a baseline complaint of mixed urinary incontinence and a longer POP-Q point D value (-9.5 instead of -7.5).

Among women with no baseline complaint of SUI, the incidence of de novo SUI was 6.3%. Significant predictors of de novo SUI in this subgroup included longer total vaginal length (10.5 cm vs. 9.5 cm, P = .003) and urinary leaks, even if they occurred about every other day as compared to not at all (P = .02).

The researchers did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

DENVER – Surgical correction of severe pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no more likely to lead to stress urinary incontinence than is correction of less severe POP, suggest findings from a retrospective study of 206 patients at a tertiary care center.

But a baseline complaint of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) prior to surgery, despite a negative SUI evaluation, was associated with an increased risk, Alexandriah Alas, MD, and her colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston wrote in a poster presented at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

“We recommend counseling patients with a negative evaluation that there is up to a 10.6% risk of developing de novo SUI,” the researchers wrote.

Past studies have linked surgical correction of POP with a 16%-51% increase in risk of de novo SUI, but have not examined whether severe prolapse adds to that risk. The researchers reviewed records from patients who underwent surgical POP correction at their center between 2003 and 2013, excluding those with objective evidence of SUI at baseline or a history of incontinence surgery. They included patients with a baseline subjective complaint of SUI, as long as it was not the primary presenting complaint.

A total of 48 (23%) patients had massive POP – that is, a POP-Q score of at least 3 at points Ba, Bp, or C – and 158 patients had less massive POP, the researchers wrote. In all, 22 patients (10.6%) developed de novo SUI. Postsurgical rates of de novo SUI were 12.5% among women with massive POP and 10.6% among women with less severe POP (P = .6).

Women with massive POP tended to be older and had a higher incidence of hypertension than those with less severe POP. After controlling for these differences, a baseline complaint of SUI was the strongest predictor of de novo SUI, increasing the odds of this outcome more than fivefold (adjusted odds ratio, 5.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-23.9). Two other factors trended toward statistical significance in this multivariable model – a baseline complaint of mixed urinary incontinence and a longer POP-Q point D value (-9.5 instead of -7.5).

Among women with no baseline complaint of SUI, the incidence of de novo SUI was 6.3%. Significant predictors of de novo SUI in this subgroup included longer total vaginal length (10.5 cm vs. 9.5 cm, P = .003) and urinary leaks, even if they occurred about every other day as compared to not at all (P = .02).

The researchers did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

DENVER – Surgical correction of severe pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no more likely to lead to stress urinary incontinence than is correction of less severe POP, suggest findings from a retrospective study of 206 patients at a tertiary care center.

But a baseline complaint of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) prior to surgery, despite a negative SUI evaluation, was associated with an increased risk, Alexandriah Alas, MD, and her colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston wrote in a poster presented at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

“We recommend counseling patients with a negative evaluation that there is up to a 10.6% risk of developing de novo SUI,” the researchers wrote.

Past studies have linked surgical correction of POP with a 16%-51% increase in risk of de novo SUI, but have not examined whether severe prolapse adds to that risk. The researchers reviewed records from patients who underwent surgical POP correction at their center between 2003 and 2013, excluding those with objective evidence of SUI at baseline or a history of incontinence surgery. They included patients with a baseline subjective complaint of SUI, as long as it was not the primary presenting complaint.

A total of 48 (23%) patients had massive POP – that is, a POP-Q score of at least 3 at points Ba, Bp, or C – and 158 patients had less massive POP, the researchers wrote. In all, 22 patients (10.6%) developed de novo SUI. Postsurgical rates of de novo SUI were 12.5% among women with massive POP and 10.6% among women with less severe POP (P = .6).

Women with massive POP tended to be older and had a higher incidence of hypertension than those with less severe POP. After controlling for these differences, a baseline complaint of SUI was the strongest predictor of de novo SUI, increasing the odds of this outcome more than fivefold (adjusted odds ratio, 5.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-23.9). Two other factors trended toward statistical significance in this multivariable model – a baseline complaint of mixed urinary incontinence and a longer POP-Q point D value (-9.5 instead of -7.5).

Among women with no baseline complaint of SUI, the incidence of de novo SUI was 6.3%. Significant predictors of de novo SUI in this subgroup included longer total vaginal length (10.5 cm vs. 9.5 cm, P = .003) and urinary leaks, even if they occurred about every other day as compared to not at all (P = .02).

The researchers did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

AT PFD WEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Postsurgical rates of de novo SUI were 12.5% among women with massive POP and 10.6% among women with less severe POP (P = .6).

Data source: A single-center retrospective study of 206 patients who underwent surgical correction of POP and had no objective evidence of SUI at baseline.

Disclosures: The researchers did not report information on funding sources or financial disclosures.

An Enhanced Recovery Program for Elective Spinal Surgery Patients

From Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, England.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a redesign of the clinical pathway for patients undergoing elective spinal surgery in order to improve quality of care and reduce length of stay.

- Methods: A multidisciplinary team undertook a process-mapping exercise and shadowed patients to analyse problems with the existing clinical pathway. Further ideas were taken from best evidence and other published enhanced recovery programs. Change ideas were tested using Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles. Measures included length of hospital stay, compliance with the pathway, and patient satisfaction.

- Results: The new pathway, the SpinaL Enhanced Recovery Program, is now used by 99% of elective spinal surgery patients with 100% of patients rating their care as good or excellent. Length of stay was reduced by 52%, improving from 5.7 days at the start of the intervention to 2.7 days. The pathway improved reliability of care, with preoperative carbohydrate drinks used in 83% of patients.

- Conclusion: The pathway improved reliability of care in our institution with excellent patient satisfaction and a significant reduction in length of hospital stay.

Enhanced recovery programs (ERPs) have been developed in many surgical specialties to improve patient outcomes and recovery after elective surgery. They involve multiple interventions throughout the patient journey, from preoperative patient education to postoperative mobilization and analgesia schedules. A meta-analysis of 38 trials involving 5099 participants showed ERPs could reduce length of stay and overall complication rates across surgical specialties [1].

There have been few studies of ERP for spinal surgery populations [2]. Most of them have studied selected patients or selected interventions such as analgesia schedules and did not use quality improvement methodology. For example, a small retrospective study compared patients undergoing multilevel spinal fusion surgery before and after introduction of a multimodal analgesia regimen [3]. A review of innovative perioperative and intraoperative treatment algorithms showed that they can influence postoperative recovery and patient outcomes from lumbar spinal surgery [4]. A study from the same group found that patient education and a “fast-track” pathway reduced length of hospital stay and improved patient satisfaction for patients undergoing 1- or 2- level lumbar spinal fusion [5].

At our hospital, a meeting of the clinicians and staff involved in elective spinal surgery was held to discuss the service. Leadership came from a consultant anesthesiologist and a consultant spinal surgeon, who recognized that care was not as efficient as it could be. A multidisciplinary team was formed consisting of 30 members, including surgeons, clinical nurse practitioners, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and secretarial staff. The team undertook a process-mapping exercise that revealed that patients followed an ill-defined care pathway with variability in administrative processes and clinical care. Patient feedback and reports from both secretarial and community staff revealed that communications from the spinal team could be inconsistent, and patients had unclear expectations of their care and recovery. Lengths of stay for the same procedure could vary by 3 days.

With support from the hospital’s chief executive and medical director, the team embarked on a process to redesign the clinical pathway for patients undergoing elective spinal surgery at our hospital. We developed the SpinaL Enhanced Recovery Program; our primary aims were to to have 95% of patients managed according to the new pathway, to reduce length of stay by 30% without a rise in readmission rates, and to improve patient satisfaction.

Methods

Ethical Issues

This work met criteria for operational improvement activities and as such was exempt from ethics review. The team engaged patients who had undergone spinal surgery to serve as representatives to ensure that the improvements studied were important to them.

Setting and Patients

Our institution is a District General Hospital that serves a population of over 340,000 and has 3 consultant spinal surgeons. They work with 5 anesthesiologists on a regular basis and the patients are cared for by 3 clinical nurse practitioners. The patients are cared for on an elective orthopedic ward with nursing staff, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists who work regularly with spinal surgery patients. The mean age of our spinal surgery patients is 55 years and 55% are female. By age-group, 6.6% are aged 1–16 years, 50.8% aged 17–65 years, and 42.6% over 65 years. We define elective spinal surgery as non-emergency surgery, including discectomy, decompression, fusion and realignment operations to the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine.

Developing the Pathway

To develop the new pathway, input from the expert team of anesthesiologists and surgeons, other clinicians and staff, as well as patients were sought. Four patients were approached prior to surgery and asked for their thoughts on the existing clinical pathway. They were then shadowed during their journey by clinical staff to see where improvements to their clinical care could be made.

In addition to gathering input from staff and patients, we reviewed the literature for the best available evidence. We found a Cochrane review of 27 trials involving 1976 surgical patients that concluded that preoperative carbohydrate drinks reduced length of stay [6]. Similarly, although laxatives have not been shown to improve length of stay [7], it is known that constipation is exacerbated by opioid analgesia and causes distress [8].

Finally, we examined the ERPs for patients undergoing hip and knee replacement that already existed in our institution. We found they used standardized anesthetic regimens as well as “patient passports,” leaflets given to give patients telling them what to expect during and following joint replacement surgery. They were also implementing methods to help patients set daily aims on the ward.

PDSA Cycles

We began PDSA testing in November 2013. Below we describe selected pathway changes that we expected to be challenging because they involved many staff from different groups. Interventions that involved fewer people or a smaller group (eg, a change in anesthetic regimen or surgical technique) were easier to implement.

Standardizing Nomenclature

The spinal consultants agreed to 12 descriptions of elective spinal surgery to improve communication between team members (Table 2). They were able to reduce the number of procedure descriptions from 135 to just 12. Theatre staff could determine from the procedure descriptions which equipment was required for the operation and ensure it was available at the time needed. Anesthetic staff felt better able to prepare for their operating lists with a prescription for preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative analgesia.

They also defined an earliest expected day of discharge (EEDD) (Table 2), which was distributed to all members of the team. This information helped ward nurses and therapists were better able to plan to mobilize patients appropriately postoperatively and ensure consistency in communication of expected length of stay to patients.

Perioperative Laxatives

Laxatives were prescribed initially for one patient and we checked to see if the patient and nursing staff were happy with the change. In the next test cycle all patients on one consultant’s list were prescribed laxatives. To track laxative use, a data collection sheet was attached to the patient's medical records on admission. With improved data collection, laxatives were then prescribed on admission for all elective spinal patients. The process has now become routine, occurring even when key change agents are absent.

Preoperative Carbohydrate Drinks

Preoperative high-calorie drinks were initially prescribed for one surgeon’s patients who were predicted to be staying 2 or more nights in the hospital. The preoperative assessment clinic (POAC) staff were asked to give these patients preoperative carbohydrate drinks at their pre-assessment clinic, and patients would self-administer their carbohydrate drinks preoperatively. However, POAC staff found it too difficult to give drinks to some patients and not to others, so it was decided that all patients should receive a drink. The clinical nurse practitioners note that the drink is given on the data collection sheet. However, it was observed that when team champions did not remind staff to administer the preoperative carbohydrate drinks, they were not given. We then asked the surgical admissions lounge staff if they would give preoperative carbohydrate drinks to patients and they agreed. This worked better than using POAC staff.

Patient Daily Aims

Members of the team felt that setting daily aims with patients would help optimize and prepare them for discharge. A laminated sheet with handwritten aims was trialed with 1 patient. He found it very useful, particularly the aims on diet and mobilization. When tested on all patients for a week, not only did they find it useful but nursing staff felt it improved communication between shifts. With greater staff buy-in and a move into a new purpose-built ward, we used white boards that were affixed to the door to the ensuite bathroom in each single patient room. Aims were discussed on ward rounds with patients by consultants or clinical nurse practitioners, and the goals agreed upon with patients before being written on the white boards. They included goals such as removal of urinary catheters, mobilization independently or with staff, and requirements such as radiographs to check position of instrumentation. Spot-checks on the ward showed good compliance with setting daily aims and high rates of satisfaction from patients.

Hospital at Home

The Hospital at Home team consists of experienced community-based nurses who provide wound care and analgesia advice for selected patients postdischarge to prevent readmission. This team supported early discharge for patients undergoing hip and knee replacements, and when approached they felt they could offer wound care and analgesia advice in the community for spinal surgery patients. This was tested with one patient with a wound who had daily care at home for 8 days following discharge from hospital. A further 2 patients were later cared for by the Hospital at Home team, with a total of 7 bed days saved. It has now become routine for the team to accept spinal patients when they have the capacity.

Outcomes

Working with the IT department and data collection tools attached to the medical records, we collected data on key measures every 2 weeks. Statistical process control charts (Process Improvement Products, Austin, TX) [9,10] were used to analyze the data.

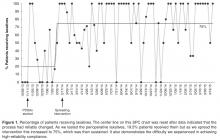

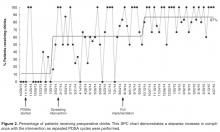

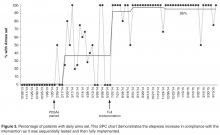

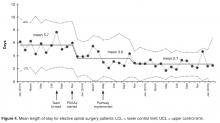

Length of stay was reduced by 52% (Figure 4), improving from an average of 6 days during the baseline period to 2.9 days by April 2015. Readmissions for elective spinal surgery patients did not increase and in fact were reduced from 7% to 3%.

By October 2014, 99% of eligible patients were managed on the new pathway and most patients were receiving key

Discussion

The new pathway, the SpinaL Enhanced Recovery Program, improved reliability of care in our institution, with excellent patient satisfaction. It also exceeded its target in reducing length of stay for elective spinal surgery patients

One of the main strengths of this work was the use of small scale testing for each change idea using PDSA cycles, ramping up the idea prior to full implementation. The team could see the impact of changes on a small scale, then make adaptations in the next cycle to increase the likelihood of success.

The development and implementation of the pathway has led to a positive culture change. The spinal team has taken ownership of the pathway and continues to monitor its impact. Seeing the impact of their work on improving the quality of patient care has enhanced the team’s self-efficacy.

The methods used to plan and study our interventions, as well as some of the change ideas themselves, may be helpful for other elective spinal surgical teams. The simple application of the interventions without the improvement process may not have delivered the same outcome. Meeting regularly as a team to discuss ideas and implement new interventions with the guidance of a quality improvement advisor (M.W.) was felt to be the most important factor for success. The team also felt that it was important to collect data by any means possible to monitor interventions and motivate staff before better automated systems were implemented.

The SpinaL Enhanced Recovery Program pathway has now become “business as usual,” and the team plans to incorporate the process and outcome measures onto a monthly performance dashboard to continue to monitor the interventions. Further interventions are planned, including improving preoperative education with a patient pathway video. The team has started to try to stagger admissions for all-day theatre lists, to avoid patients having to wait all day for an afternoon operation. Further improvements in the reliability of care will also potentially allow the team to run controlled studies of single interventions to see how these can impact quality of patient care in a stable process.

Acknowledgments: The authors acknowledge Deborah Ray, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Sandra Murray, Associates in Healthcare Improvement; Matthew Beebee, Clinical Nurse Practitioner Spinal Surgery; Debbie Vile and Lorraine Sandford, Clinical Nurse Practitioners Spinal Surgery; Sophie Hudson and Sallie Durman, Secretaries; Eleanor Palfreman, Occupational Therapist; Sarah Woodhill, Physiotherapist; Lee Scott, Improvement Nurse; Gervaise Khan-Davis, Directorate Manager; and “SG,” previous patient.

Corresponding author: Dr Julia Blackburn, Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, England, TA1 5DA, jlrkblackburn@doctors.org.uk.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nicholson A, Lowe MC, Parker J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery programmes in surgical patients. Br J Surg 2014;101:172–88.

2. Venkata H, Van Dellen J. A perspective on the use of an Enhanced Recovery Programme in open, non-instrumented, ‘day-surgery’ for degenerative lumbar and cervical spinal conditions. J Neurosurg Sci 2016.

3. Mathiesen O, Dahl B, Thomsen B, et al. A comprehensive multimodal pain treatment reduces opioid consumption after multilevel spine surgery. Eur Spine J 2013;22:2089–96.

4. Fleege C, Almajali A, Rauschmann M, et al. Improve of surgical outcome in spinal fusion surgery. Evidence based peri- and intra-operative aspects to reduce complications and earlier recovery. Der Orthopade 2014;43:1070–8.

5. Fleege C, Arabmotlagh M, Almajali A, et al. Pre- and postoperative fast-track treatment concepts in spinal surgery. Patient information and patient cooperation. Der Orthopade 2014;43:1062.