User login

The Most Misinterpreted Study in Medicine: Don’t be TRICCed

Ah, blood. That sweet nectar of life that quiets angina, abolishes dyspnea, prevents orthostatic syncope, and quells sinus tachycardia. As a cardiologist, I am an unabashed hemophile.

But we liberal transfusionists are challenged on every request for consideration of transfusion. Whereas the polite may resort to whispered skepticism, vehement critics respond with scorn as if we’d asked them to burn aromatic herbs or fetch a bucket of leeches. And to what do we owe this pathological angst? The broad and persistent misinterpretation of the pesky TRICC trial (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417). You know; the one that should have been published with a boxed warning stating: “Misinterpretation of this trial could result in significant harm.”

Point 1: Our Actively Bleeding Patient is Not a TRICC Patient.

They were randomly assigned to either a conservative trigger for transfusion of < 7 g/dL or a liberal threshold of < 10 g/dL. Mortality at 30 days was lower with the conservative approach — 18.7% vs 23.3% — but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .11). The findings were similar for the secondary endpoints of inpatient mortality (22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05) and ICU mortality (13.9% vs 16.2%; P = .29).

One must admit that these P values are not impressive, and the authors’ conclusion should have warranted caution: “A restrictive strategy ... is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina.”

Point 2: Our Critically Ill Cardiac Patient is Unlikely to be a “TRICC” Patient.

Another criticism of TRICC is that only 13% of those assessed and 26% of those eligible were enrolled, mostly owing to physician refusal. Only 26% of enrolled patients had cardiac disease. This makes the TRICC population highly selected and not representative of typical ICU patients.

To prove my point that the edict against higher transfusion thresholds can be dangerous, I’ll describe my most recent interface with TRICC trial misinterpretation

A Case in Point

The patient, Mrs. Kemp,* is 79 years old and has been on aspirin for years following coronary stent placement. One evening, she began spurting bright red blood from her rectum, interrupted only briefly by large clots the consistency of jellied cranberries. When she arrived at the hospital, she was hemodynamically stable, with a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, down from her usual 12 g/dL. That level bolstered the confidence of her provider, who insisted that she be managed conservatively.

Mrs. Kemp was transferred to the ward, where she continued to bleed briskly. Over the next 2 hours, her hemoglobin level dropped to 9 g/dL, then 8 g/dL. Her daughter, a healthcare worker, requested a transfusion. The answer was, wait for it — the well-scripted, somewhat patronizing oft-quoted line, “The medical literature states that we need to wait for a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL before we transfuse.”

Later that evening, Mrs. Kemp’s systolic blood pressure dropped to the upper 80s, despite her usual hypertension. The provider was again comforted by the fact that she was not tachycardic (she had a pacemaker and was on bisoprolol). The next morning, Mrs. Kemp felt the need to defecate and was placed on the bedside commode and left to her privacy. Predictably, she became dizzy and experienced frank syncope. Thankfully, she avoided a hip fracture or worse. A stat hemoglobin returned at 6 g/dL.

Her daughter said she literally heard the hallelujah chorus because her mother’s hemoglobin was finally below that much revered and often misleading threshold of 7 g/dL. Finally, there was an order for platelets and packed red cells. Five units later, Mr. Kemp achieved a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and survived. Two more units and she was soaring at 9 g/dL!

Lessons for Transfusion Conservatives

There are many lessons here.

The TRICC study found that hemodynamically stable, asymptomatic patients who are not actively bleeding may well tolerate a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL. But a patient with bright red blood actively pouring from an orifice and a rapidly declining hemoglobin level isn’t one of those people. Additionally, a patient who faints from hypovolemia is not one of those people.

Patients with a history of bleeding presenting with new resting sinus tachycardia (in those who have chronotropic competence) should be presumed to be actively bleeding, and the findings of TRICC do not apply to them. Patients who have bled buckets on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies and have dropped their hemoglobin will probably continue to ooze and should be subject to a low threshold for transfusion.

Additionally, anemic people who are hemodynamically stable but can’t walk without new significant shortness of air or new rest angina need blood, and sometimes at hemoglobin levels higher than generally accepted by conservative strategists. Finally, failing to treat or at least monitor patients who are spontaneously bleeding as aggressively as some trauma patients is a failure to provide proper medical care.

The vast majority of my healthcare clinician colleagues are competent, compassionate individuals who can reasonably discuss the nuances of any medical scenario. One important distinction of a good medical team is the willingness to change course based on a change in patient status or the presentation of what may be new information for the provider.

But those proud transfusion conservatives who will not budge until their threshold is met need to make certain their patient is truly subject to their supposed edicts. Our blood banks should not be more difficult to access than Fort Knox, and transfusion should be used appropriately and liberally in the hemodynamically unstable, the symptomatic, and active brisk bleeders.

I beg staunch transfusion conservatives to consider how they might feel if someone stuck a magic spigot in their brachial artery and acutely drained their hemoglobin to that magic threshold of 7 g/dL. When syncope, shortness of air, fatigue, and angina find them, they may generate empathy for those who need transfusion. Might that do the TRICC?

*Some details have been changed to conceal the identity of the patient, but the essence of the case has been preserved.

Dr. Walton-Shirley, a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology and now does locums work in Montana, is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ah, blood. That sweet nectar of life that quiets angina, abolishes dyspnea, prevents orthostatic syncope, and quells sinus tachycardia. As a cardiologist, I am an unabashed hemophile.

But we liberal transfusionists are challenged on every request for consideration of transfusion. Whereas the polite may resort to whispered skepticism, vehement critics respond with scorn as if we’d asked them to burn aromatic herbs or fetch a bucket of leeches. And to what do we owe this pathological angst? The broad and persistent misinterpretation of the pesky TRICC trial (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417). You know; the one that should have been published with a boxed warning stating: “Misinterpretation of this trial could result in significant harm.”

Point 1: Our Actively Bleeding Patient is Not a TRICC Patient.

They were randomly assigned to either a conservative trigger for transfusion of < 7 g/dL or a liberal threshold of < 10 g/dL. Mortality at 30 days was lower with the conservative approach — 18.7% vs 23.3% — but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .11). The findings were similar for the secondary endpoints of inpatient mortality (22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05) and ICU mortality (13.9% vs 16.2%; P = .29).

One must admit that these P values are not impressive, and the authors’ conclusion should have warranted caution: “A restrictive strategy ... is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina.”

Point 2: Our Critically Ill Cardiac Patient is Unlikely to be a “TRICC” Patient.

Another criticism of TRICC is that only 13% of those assessed and 26% of those eligible were enrolled, mostly owing to physician refusal. Only 26% of enrolled patients had cardiac disease. This makes the TRICC population highly selected and not representative of typical ICU patients.

To prove my point that the edict against higher transfusion thresholds can be dangerous, I’ll describe my most recent interface with TRICC trial misinterpretation

A Case in Point

The patient, Mrs. Kemp,* is 79 years old and has been on aspirin for years following coronary stent placement. One evening, she began spurting bright red blood from her rectum, interrupted only briefly by large clots the consistency of jellied cranberries. When she arrived at the hospital, she was hemodynamically stable, with a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, down from her usual 12 g/dL. That level bolstered the confidence of her provider, who insisted that she be managed conservatively.

Mrs. Kemp was transferred to the ward, where she continued to bleed briskly. Over the next 2 hours, her hemoglobin level dropped to 9 g/dL, then 8 g/dL. Her daughter, a healthcare worker, requested a transfusion. The answer was, wait for it — the well-scripted, somewhat patronizing oft-quoted line, “The medical literature states that we need to wait for a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL before we transfuse.”

Later that evening, Mrs. Kemp’s systolic blood pressure dropped to the upper 80s, despite her usual hypertension. The provider was again comforted by the fact that she was not tachycardic (she had a pacemaker and was on bisoprolol). The next morning, Mrs. Kemp felt the need to defecate and was placed on the bedside commode and left to her privacy. Predictably, she became dizzy and experienced frank syncope. Thankfully, she avoided a hip fracture or worse. A stat hemoglobin returned at 6 g/dL.

Her daughter said she literally heard the hallelujah chorus because her mother’s hemoglobin was finally below that much revered and often misleading threshold of 7 g/dL. Finally, there was an order for platelets and packed red cells. Five units later, Mr. Kemp achieved a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and survived. Two more units and she was soaring at 9 g/dL!

Lessons for Transfusion Conservatives

There are many lessons here.

The TRICC study found that hemodynamically stable, asymptomatic patients who are not actively bleeding may well tolerate a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL. But a patient with bright red blood actively pouring from an orifice and a rapidly declining hemoglobin level isn’t one of those people. Additionally, a patient who faints from hypovolemia is not one of those people.

Patients with a history of bleeding presenting with new resting sinus tachycardia (in those who have chronotropic competence) should be presumed to be actively bleeding, and the findings of TRICC do not apply to them. Patients who have bled buckets on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies and have dropped their hemoglobin will probably continue to ooze and should be subject to a low threshold for transfusion.

Additionally, anemic people who are hemodynamically stable but can’t walk without new significant shortness of air or new rest angina need blood, and sometimes at hemoglobin levels higher than generally accepted by conservative strategists. Finally, failing to treat or at least monitor patients who are spontaneously bleeding as aggressively as some trauma patients is a failure to provide proper medical care.

The vast majority of my healthcare clinician colleagues are competent, compassionate individuals who can reasonably discuss the nuances of any medical scenario. One important distinction of a good medical team is the willingness to change course based on a change in patient status or the presentation of what may be new information for the provider.

But those proud transfusion conservatives who will not budge until their threshold is met need to make certain their patient is truly subject to their supposed edicts. Our blood banks should not be more difficult to access than Fort Knox, and transfusion should be used appropriately and liberally in the hemodynamically unstable, the symptomatic, and active brisk bleeders.

I beg staunch transfusion conservatives to consider how they might feel if someone stuck a magic spigot in their brachial artery and acutely drained their hemoglobin to that magic threshold of 7 g/dL. When syncope, shortness of air, fatigue, and angina find them, they may generate empathy for those who need transfusion. Might that do the TRICC?

*Some details have been changed to conceal the identity of the patient, but the essence of the case has been preserved.

Dr. Walton-Shirley, a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology and now does locums work in Montana, is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ah, blood. That sweet nectar of life that quiets angina, abolishes dyspnea, prevents orthostatic syncope, and quells sinus tachycardia. As a cardiologist, I am an unabashed hemophile.

But we liberal transfusionists are challenged on every request for consideration of transfusion. Whereas the polite may resort to whispered skepticism, vehement critics respond with scorn as if we’d asked them to burn aromatic herbs or fetch a bucket of leeches. And to what do we owe this pathological angst? The broad and persistent misinterpretation of the pesky TRICC trial (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417). You know; the one that should have been published with a boxed warning stating: “Misinterpretation of this trial could result in significant harm.”

Point 1: Our Actively Bleeding Patient is Not a TRICC Patient.

They were randomly assigned to either a conservative trigger for transfusion of < 7 g/dL or a liberal threshold of < 10 g/dL. Mortality at 30 days was lower with the conservative approach — 18.7% vs 23.3% — but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .11). The findings were similar for the secondary endpoints of inpatient mortality (22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05) and ICU mortality (13.9% vs 16.2%; P = .29).

One must admit that these P values are not impressive, and the authors’ conclusion should have warranted caution: “A restrictive strategy ... is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina.”

Point 2: Our Critically Ill Cardiac Patient is Unlikely to be a “TRICC” Patient.

Another criticism of TRICC is that only 13% of those assessed and 26% of those eligible were enrolled, mostly owing to physician refusal. Only 26% of enrolled patients had cardiac disease. This makes the TRICC population highly selected and not representative of typical ICU patients.

To prove my point that the edict against higher transfusion thresholds can be dangerous, I’ll describe my most recent interface with TRICC trial misinterpretation

A Case in Point

The patient, Mrs. Kemp,* is 79 years old and has been on aspirin for years following coronary stent placement. One evening, she began spurting bright red blood from her rectum, interrupted only briefly by large clots the consistency of jellied cranberries. When she arrived at the hospital, she was hemodynamically stable, with a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, down from her usual 12 g/dL. That level bolstered the confidence of her provider, who insisted that she be managed conservatively.

Mrs. Kemp was transferred to the ward, where she continued to bleed briskly. Over the next 2 hours, her hemoglobin level dropped to 9 g/dL, then 8 g/dL. Her daughter, a healthcare worker, requested a transfusion. The answer was, wait for it — the well-scripted, somewhat patronizing oft-quoted line, “The medical literature states that we need to wait for a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL before we transfuse.”

Later that evening, Mrs. Kemp’s systolic blood pressure dropped to the upper 80s, despite her usual hypertension. The provider was again comforted by the fact that she was not tachycardic (she had a pacemaker and was on bisoprolol). The next morning, Mrs. Kemp felt the need to defecate and was placed on the bedside commode and left to her privacy. Predictably, she became dizzy and experienced frank syncope. Thankfully, she avoided a hip fracture or worse. A stat hemoglobin returned at 6 g/dL.

Her daughter said she literally heard the hallelujah chorus because her mother’s hemoglobin was finally below that much revered and often misleading threshold of 7 g/dL. Finally, there was an order for platelets and packed red cells. Five units later, Mr. Kemp achieved a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and survived. Two more units and she was soaring at 9 g/dL!

Lessons for Transfusion Conservatives

There are many lessons here.

The TRICC study found that hemodynamically stable, asymptomatic patients who are not actively bleeding may well tolerate a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL. But a patient with bright red blood actively pouring from an orifice and a rapidly declining hemoglobin level isn’t one of those people. Additionally, a patient who faints from hypovolemia is not one of those people.

Patients with a history of bleeding presenting with new resting sinus tachycardia (in those who have chronotropic competence) should be presumed to be actively bleeding, and the findings of TRICC do not apply to them. Patients who have bled buckets on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies and have dropped their hemoglobin will probably continue to ooze and should be subject to a low threshold for transfusion.

Additionally, anemic people who are hemodynamically stable but can’t walk without new significant shortness of air or new rest angina need blood, and sometimes at hemoglobin levels higher than generally accepted by conservative strategists. Finally, failing to treat or at least monitor patients who are spontaneously bleeding as aggressively as some trauma patients is a failure to provide proper medical care.

The vast majority of my healthcare clinician colleagues are competent, compassionate individuals who can reasonably discuss the nuances of any medical scenario. One important distinction of a good medical team is the willingness to change course based on a change in patient status or the presentation of what may be new information for the provider.

But those proud transfusion conservatives who will not budge until their threshold is met need to make certain their patient is truly subject to their supposed edicts. Our blood banks should not be more difficult to access than Fort Knox, and transfusion should be used appropriately and liberally in the hemodynamically unstable, the symptomatic, and active brisk bleeders.

I beg staunch transfusion conservatives to consider how they might feel if someone stuck a magic spigot in their brachial artery and acutely drained their hemoglobin to that magic threshold of 7 g/dL. When syncope, shortness of air, fatigue, and angina find them, they may generate empathy for those who need transfusion. Might that do the TRICC?

*Some details have been changed to conceal the identity of the patient, but the essence of the case has been preserved.

Dr. Walton-Shirley, a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology and now does locums work in Montana, is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New Tourniquet: The AED for Bleeding?

This discussion was recorded on July 12, 2024. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Hi and welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. I recently met an innovative young woman named Hannah Herbst while attending the annual Eagles EMS Conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Hannah Herbst is a graduate of Florida Atlantic University, selected for Forbes 30 Under 30, and founder of a company called Golden Hour Medical. She has a background in IT and developed an automated pneumatic tourniquet known as AutoTQ, which we’re going to discuss at length here.

Also joining us is Dr. Peter Antevy, a pediatric emergency physician and medical director for Davie Fire Rescue as well as Coral Springs Parkland Fire Rescue. Peter is a member of EMS Eagles Global Alliance and is highly involved in high-quality research in prehospital emergency care and is quite well known in Florida and nationally.

Welcome to both of you.

Hannah Herbst: Thank you very much. Very grateful to be here.

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, I’ll let you start by explaining what AutoTQ is and then compare that to a standard Combat Application Tourniquet (CAT).

Ms. Herbst: Thank you. Unfortunately, blood loss is a leading cause of preventable death and trauma. When there’s blood loss occurring from an arm or a leg, the easiest way to stop it is by applying a tourniquet, which is this compression type of device that you place above the site of bleeding, and it then applies a high amount of pressure to stop blood flow through the limb.

Currently, tourniquets on the market have failure rates as high as 84%. This became very real to me back in 2018, when I became aware of mass casualty incidents when I was a student. I became interested in how we can reimagine the conventional tourniquet and try to make it something that’s very user-friendly, much like an automated external defibrillator (AED).

My team and I developed AutoTQ, which is an automated tourniquet. which is a leading cause of tourniquet failure and being able to effectively administer treatment to a patient that may bleed out.

Tourniquet Failure Rates

Dr. Glatter: In terms of tourniquet failure, how often do standard tourniquets fail, like the CAT combat-type tourniquet?

Ms. Herbst: Unfortunately, they fail very frequently. There are several studies that have been conducted to evaluate this. Many of them occur immediately after training. They found failure rates between 80% and 90% for the current conventional CAT tourniquet immediately after training, which is very concerning.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of failure, was it the windlass aspect of the tourniquet that failed? Or was it something related to the actual strap? Was that in any way detailed?

Ms. Herbst: There are usually a few different failure points that have been found in the literature. One is placement. Many times, when you’re panicked, you don’t remember exactly how to place it. It should be placed high and tight above the bleed and not over a joint.

The second problem is inadequate tightness. For a CAT tourniquet to be effective, you have to get it extremely tight on that first pull before the windlass is activated, and many times people don’t remember that in the stress of the moment.

Dr. Glatter: Peter, in terms of tourniquet application by your medics in the field, certainly the CAT-type device has been in existence for quite a while. Hannah’s proposing a new iteration of how to do this, which is automated and simple. What is your take on such a device? And how did you learn about Hannah’s device?

Peter M. Antevy, MD: We’ve been training on tourniquets ever since the military data showed that there was an extreme benefit in using them. We’ve been doing training for many years, including our police officers. What we’ve noticed is that every time we gather everyone together to show them how to place a tourniquet — and we have to do one-on-one sessions with them — it’s not a device that they can easily put on. These are police officers who had the training last year.

Like Hannah said, most of the time they have a problem unraveling it and understanding how to actually place it. It’s easier on the arm than it is on the leg. You can imagine it would be harder to place it on your own leg, especially if you had an injury. Then, they don’t tighten it well enough, as Hannah just mentioned. In order for a tourniquet to really be placed properly, it’s going to hurt that person. Many people have that tendency not to want to tighten it as much as they can.

Having said that, how I got into all of this is because I’m the medical director for Coral Springs and Parkland, and unfortunately, we had the 2018 Valentine’s Day murders that happened where we lost 17 adults and kids. However, 17 people were saved that day, and the credit goes to our police officers who had tourniquets or chest seals on before those patients were brought out to EMS. Many lives were saved by the tourniquet.

If you look at the Boston Marathon massacre and many other events that have happened, I believe — and I’ve always believed — that tourniquets should be in the glove box of every citizen. It should be in every school room. They should be in buildings along with the AED.

In my town of Davie, we were the first in the country to add an ordinance that required a Stop the Bleed kit in the AED cabinet, and those were required by buildings of certain sizes. In order to get this lifesaving device everywhere, I think it has to be put into local ordinance and supported by states and by the national folks, which they are doing.

Trials Are Underway

Dr. Glatter: In terms of adoption of such a device, it certainly has to go through rigorous testing and maybe some trials. Hannah, where are you at with vetting this in terms of any type of trial? Has it been compared head to head with standard tourniquets?

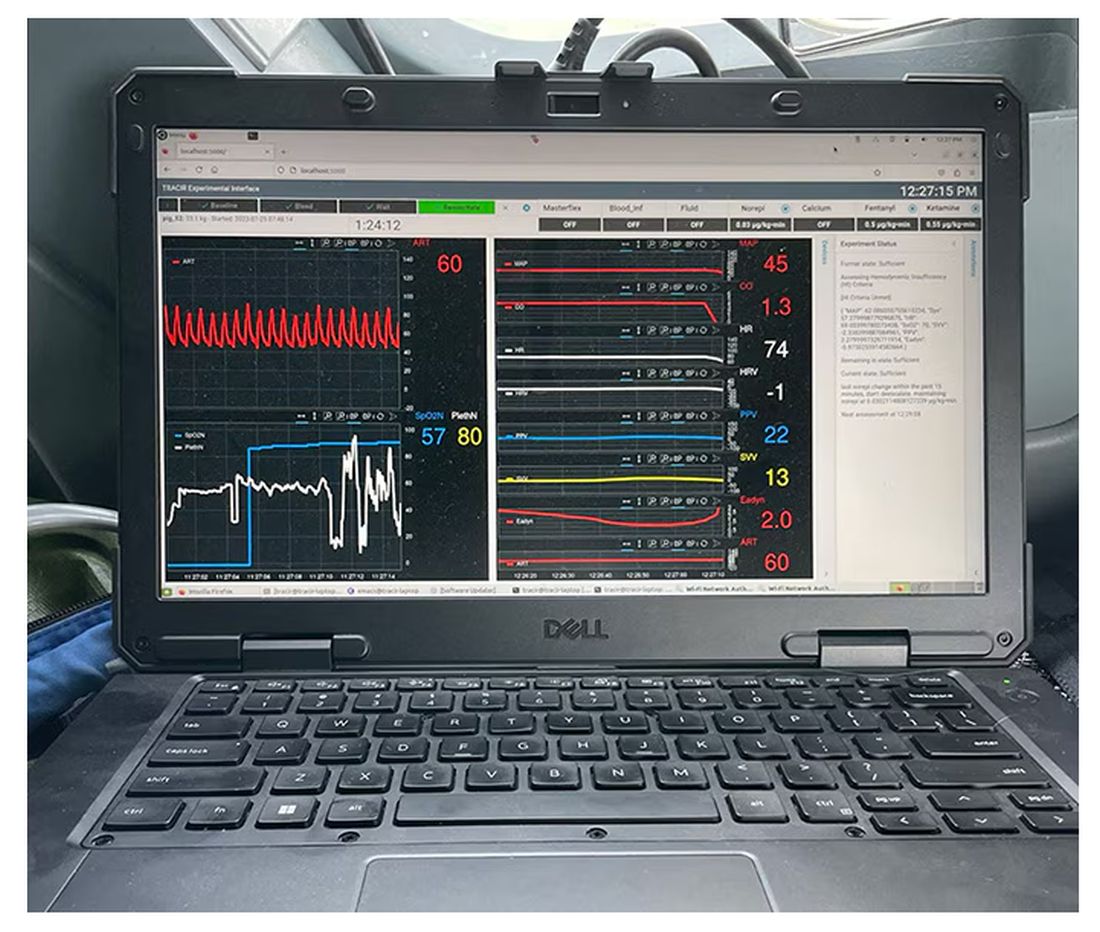

Ms. Herbst: Yes, we’re currently doing large amounts of field testing. We’re doing testing on emergency vehicles and in the surgical setting with different customers. In addition, we’re running pilot studies at different universities and with different organizations, including the military, to make sure that this device is effective. We’re evaluating cognitive offloading of people. We’re hoping to start that study later this year. We’re excited to be doing this in a variety of settings.

We’re also testing the quality of it in different environmental conditions and under different atmospheric pressure. We’re doing everything we can to ensure the device is safe and effective. We’re excited to scale and fill our preorders and be able to develop this and deliver it to many people.

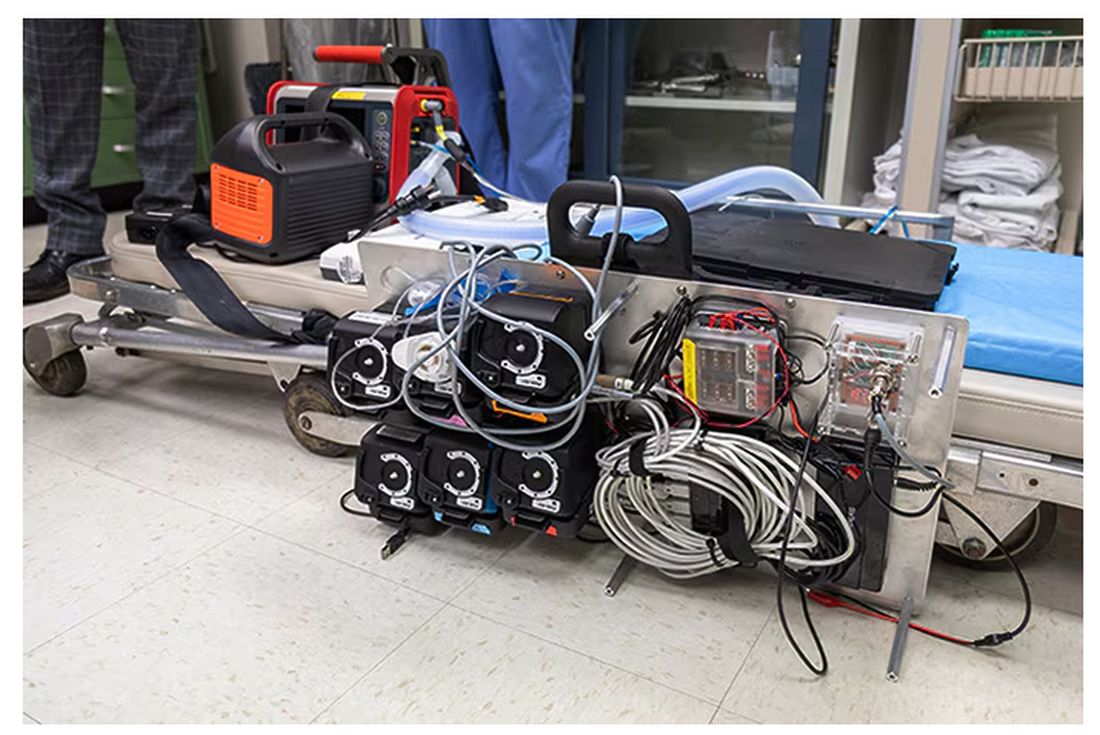

Dr. Glatter: I was wondering if you could describe the actual device. There’s a brain part of it and then, obviously, the strap aspect of it. I was curious about contamination and reusability issues.

Ms. Herbst: That’s a great question. One of the limitations of conventional tourniquets on the market is that they are single use, and often, it requires two tourniquets to stop a bleed, both of which have to be disposed of.

With AutoTQ, we have a reusable component and a disposable component. I actually have one here that I can show you. We have a cover on it that says: Stop bleed, slide up and power on. You just pull this cover off and then you have a few simple commands. You have powering the device on. I’ll just click this button: Tighten strap above bleeding, then press inflate. It delivers audible instructions telling you exactly how to use the device. Then, you tighten it above your bleed on the limb, and you press the inflate button. Then it administers air into the cuff and stops the patient’s bleed.

Tourniquet Conversion and Limb Salvage

Dr. Glatter: In terms of ischemia time, how can a device like this make it easier for us to know when to let the tourniquet down and allow some blood flow? Certainly, limb salvage is important, and we don’t want to have necrosis and so forth.

Dr. Antevy: That’s a great question. The limb salvage rate when tourniquets have been used is 85%. When used correctly, you can really improve the outcomes for many patients.

On the flip side of that, there’s something called tourniquet conversion. That’s exactly what you mentioned. It’s making sure that the tourniquet doesn’t stay on for too long of a time. If you can imagine a patient going to an outlying hospital where there’s no trauma center, and then that patient then has to be moved a couple hours to the trauma center, could you potentially have a tourniquet on for too long that then ends up causing the patient a bad outcome? The answer is yes.

I just had someone on my webinar recently describing the appropriate conversion techniques of tourniquets. You don’t find too much of that in the literature, but you really have to ensure that as you’re taking the tourniquet down, the bleeding is actually stopped. It’s not really recommended to take a tourniquet down if the patient was just acutely bleeding.

However, imagine a situation where a tourniquet was put on incorrectly. Let’s say a patient got nervous and they just put it on a patient who didn’t really need it. You really have to understand how to evaluate that wound to be sure that, as you’re taking the tourniquet down slowly, the patient doesn’t rebleed again.

There are two sides of the question, Rob. One is making sure it’s not on inappropriately. The second one is making sure it’s not on for too long, which ends up causing ischemia to that limb.

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, does your device collect data on the number of hours or minutes that the tourniquet has been up and then automatically deflate it in some sense to allow for that improvement in limb salvage?

Ms. Herbst: That’s a great question, and I really appreciate your answer as well, Dr Antevy. Ischemia time is a very important and critical component of tourniquet use. This is something, when we were designing AutoTQ, that we took into high consideration.

We found, when we evaluated AutoTQ vs a CAT tourniquet in a mannequin model, that AutoTQ can achieve cessation of hemorrhage at around 400 mm Hg of mercury, whereas CAT requires 700-800 mm Hg. Already our ischemia time is slightly extended just based on existing literature with pneumatic tourniquets because it can stop the bleed at a lower pressure, which causes less complications with the patient’s limb.

There are different features that we build out for different customers, so depending on what people want, it is possible to deflate the tourniquet. However, typically, you’re at the hospital within 30 minutes. It’s quick to get them there, and then the physician can treat and take that tourniquet down in a supervised and controlled setting.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of patients with obesity, do you have adjustable straps that will accommodate for that aspect?

Ms. Herbst: Yes, we have different cuff sizes to accommodate different limbs.

Will AutoTQ Be Available to the Public?

Dr. Glatter: Peter, in terms of usability in the prehospital setting, where do you think this is going in the next 3-5 years?

Dr. Antevy: I’ll start with the public safety sector of the United States, which is the one that is actually first on scene. Whether you’re talking about police officers or EMS, it would behoove us to have tourniquets everywhere. On all of my ambulances, across all of my agencies that I manage, we have quite a number of tourniquets.

Obviously, cost is a factor, and I know that Hannah has done a great job of making that brain reusable. All we have to do is purchase the straps, which are effectively the same cost, I understand, as a typical tourniquet you would purchase.

Moving forward though, however, I think that this has wide scalability to the public market, whether it be schools, office buildings, the glove box, and so on. It’s really impossible to teach somebody how to do this the right way, if you have to teach them how to put the strap on, tighten it correctly, and so on. If there was an easy way, like Hannah developed, of just putting it on and pushing a button, then I think that the outcomes and the scalability are much further beyond what we can do in EMS. I think there’s great value in both markets.

The ‘AED of Bleeding’: Rechargeable and Reusable

Dr. Glatter: This is the AED of bleeding. You have a device here that has wide-scale interest, certainly from the public and private sector.

Hannah, in terms of battery decay, how would that work out if it was in someone’s garage? Let’s just say someone purchased it and they hadn’t used it in 3 or 4 months. What type of decay are we looking at and can they rely on it?

Ms. Herbst: AutoTQ is rechargeable by a USB-C port, and our battery lasts for a year. Once a year, you’ll get an email reminder that says: “Hey, please charge your AutoTQ and make sure it’s up to the battery level.” We do everything in our power to make sure that our consumers are checking their batteries and that they’re ready to go.

Dr. Glatter: Is it heat and fire resistant? What, in terms of durability, does your device have?

Ms. Herbst: Just like any other medical device, we come with manufacturer recommendations for the upper and lower bounds of temperature and different storage recommendations. All of that is in our instructions for use.

Dr. Glatter: Peter, getting back to logistics. In terms of adoption, do you feel that, in the long term, this device will be something that we’re going to be seeing widely adopted just going forward?

Dr. Antevy: I do, and I’ll tell you why. When you look at AED use in this country, the odds of someone actually getting an AED and using it correctly are still very low. Part of that is because it’s complicated for many people to do. Getting tourniquets everywhere is step No. 1, and I think the federal government and the Stop the Bleed program is really making that happen.

We talked about ordinances, but ease of use, I think, is really the key. You have people who oftentimes have their child in cardiac arrest in front of them, and they won’t put two hands on their chest because they just are afraid of doing it.

When you have a device that’s a tourniquet, that’s a single-button turn on and single-button inflate, I think that would make it much more likely that a person will use that device when they’re passing the scene of an accident, as an example.

We’ve had many non–mass casualty incident events that have had tourniquets. We’ve had some media stories on them, where they’re just happening because someone got into a motor vehicle accident. It doesn’t have to be a school shooting. I think the tourniquets should be everywhere and should be easily used by everybody.

Managing Pain

Dr. Glatter: Regarding sedation, is there a need because of the pain involved with the application? How would you sedate a patient, pediatric or adult, who needs a tourniquet?

Dr. Antevy: We always evaluate people’s pain. If the patient is an extremist, we’re just going to be managing and trying to get them back to life. Once somebody is stabilized and is exhibiting pain of any sort, even, for example, after we intubate somebody, we have to sedate them and provide them pain control because they have a piece of plastic in their trachea.

It’s the same thing here for a tourniquet. These are painful, and we do have the appropriate medications on our vehicles to address that pain. Again, just simply the trauma itself is very painful. Yes, we do address that in EMS, and I would say most public agencies across this country would address pain appropriately.

Training on Tourniquet Use

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, can you talk a little bit about public training types of approaches? How would you train a consumer who purchases this type of device?

Ms. Herbst: A huge part of our mission is making blood loss prevention and control training accessible to a wide variety of people. One way that we’re able to do that is through our online training platform. When you purchase an AutoTQ kit, you plug it into your computer, and it walks you through the process of using it. It lets you practice on your own limb and on your buddy’s limb, just to be able to effectively apply it. We think this will have huge impacts in making sure that people are prepared and ready to stop the bleed with AutoTQ.

Dr. Glatter: Do you recommend people training once a month, in general, just to keep their skills up to use this? In the throes of a trauma and very chaotic situation, people sometimes lose their ability to think clearly and straightly.

Ms. Herbst: One of the studies we’re conducting is a learning curve study to try to figure out how quickly these skills degrade over time. We know that with the windlass tourniquet, it degrades within moments of training. With AutoTQ, we think the learning curve will last much longer. That’s something we’re evaluating, but we recommend people train as often as they can.

Dr. Antevy: Rob, if I can mention that there is a concept of just-in-time training. I think that with having the expectation that people are going to be training frequently, unfortunately, as many of us know, even with the AED as a perfect example, people don’t do that.

Yes. I would agree that you have to train at least once a year, is what I would say. At my office, we have a 2-hour training that goes over all these different items once a year.

The device itself should have the ability to allow you to figure out how to use it just in time, whether via video, or like Hannah’s device, by audio. I think that having both those things would make it more likely that the device be used when needed.

People panic, and if they have a device that can talk to them or walk them through it, they will be much more likely to use it at that time.

Final Takeaways

Dr. Glatter: Any other final thoughts or a few pearls for listeners to take away? Hannah, I’ll start with you.

Ms. Herbst: I’m very grateful for your time, and I’m very excited about the potential for AutoTQ. To me, it’s so exciting to see people preordering the device now. We’ve had people from school bus companies and small sports teams. I think, just like Dr Antevy said, tourniquets aren’t limited to mass casualty situations. Blood loss can happen anywhere and to anyone.

Being able to equip people and serve them to better prepare them for this happening to themselves, their friends, or their family is just the honor of a lifetime. Thank you very much for covering the device and for having me today.

Dr. Glatter: Of course, my pleasure. Peter?

Dr. Antevy: The citizens of this country, and everyone who lives across the world, has started to understand that there are things that we expect from our people, from the community. We expect them to do CPR for cardiac arrest. We expect them to know how to use an EpiPen. We expect them to know how to use an AED, and we also expect them to know how to stop bleeding with a tourniquet.

The American public has gotten to understand that these devices are very important. Having a device that’s easily used, that I can teach you in 10 seconds, that speaks to you — these are all things that make this product have great potential. I do look forward to the studies, not just the cadaver studies, but the real human studies.

I know Hannah is really a phenom and has been doing all these things so that this product can be on the shelves of Walmart and CVS one day. I commend you, Hannah, for everything you’re doing and wishing you the best of luck. We’re here for you.

Dr. Glatter: Same here. Congratulations on your innovative capability and what you’ve done to change the outcomes of bleeding related to penetrating trauma. Thank you so much.

Robert D. Glatter, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is a medical advisor for Medscape and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series. Hannah D. Herbst, BS, is a graduate of Florida Atlantic University, was selected for Forbes 30 Under 30, and is the founder/CEO of Golden Hour Medical. Peter M. Antevy, MD, is a pediatric emergency medicine physician and medical director for Davie Fire Rescue and Coral Springs–Parkland Fire Department in Florida. He is also a member of the EMS Eagles Global Alliance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on July 12, 2024. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Hi and welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. I recently met an innovative young woman named Hannah Herbst while attending the annual Eagles EMS Conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Hannah Herbst is a graduate of Florida Atlantic University, selected for Forbes 30 Under 30, and founder of a company called Golden Hour Medical. She has a background in IT and developed an automated pneumatic tourniquet known as AutoTQ, which we’re going to discuss at length here.

Also joining us is Dr. Peter Antevy, a pediatric emergency physician and medical director for Davie Fire Rescue as well as Coral Springs Parkland Fire Rescue. Peter is a member of EMS Eagles Global Alliance and is highly involved in high-quality research in prehospital emergency care and is quite well known in Florida and nationally.

Welcome to both of you.

Hannah Herbst: Thank you very much. Very grateful to be here.

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, I’ll let you start by explaining what AutoTQ is and then compare that to a standard Combat Application Tourniquet (CAT).

Ms. Herbst: Thank you. Unfortunately, blood loss is a leading cause of preventable death and trauma. When there’s blood loss occurring from an arm or a leg, the easiest way to stop it is by applying a tourniquet, which is this compression type of device that you place above the site of bleeding, and it then applies a high amount of pressure to stop blood flow through the limb.

Currently, tourniquets on the market have failure rates as high as 84%. This became very real to me back in 2018, when I became aware of mass casualty incidents when I was a student. I became interested in how we can reimagine the conventional tourniquet and try to make it something that’s very user-friendly, much like an automated external defibrillator (AED).

My team and I developed AutoTQ, which is an automated tourniquet. which is a leading cause of tourniquet failure and being able to effectively administer treatment to a patient that may bleed out.

Tourniquet Failure Rates

Dr. Glatter: In terms of tourniquet failure, how often do standard tourniquets fail, like the CAT combat-type tourniquet?

Ms. Herbst: Unfortunately, they fail very frequently. There are several studies that have been conducted to evaluate this. Many of them occur immediately after training. They found failure rates between 80% and 90% for the current conventional CAT tourniquet immediately after training, which is very concerning.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of failure, was it the windlass aspect of the tourniquet that failed? Or was it something related to the actual strap? Was that in any way detailed?

Ms. Herbst: There are usually a few different failure points that have been found in the literature. One is placement. Many times, when you’re panicked, you don’t remember exactly how to place it. It should be placed high and tight above the bleed and not over a joint.

The second problem is inadequate tightness. For a CAT tourniquet to be effective, you have to get it extremely tight on that first pull before the windlass is activated, and many times people don’t remember that in the stress of the moment.

Dr. Glatter: Peter, in terms of tourniquet application by your medics in the field, certainly the CAT-type device has been in existence for quite a while. Hannah’s proposing a new iteration of how to do this, which is automated and simple. What is your take on such a device? And how did you learn about Hannah’s device?

Peter M. Antevy, MD: We’ve been training on tourniquets ever since the military data showed that there was an extreme benefit in using them. We’ve been doing training for many years, including our police officers. What we’ve noticed is that every time we gather everyone together to show them how to place a tourniquet — and we have to do one-on-one sessions with them — it’s not a device that they can easily put on. These are police officers who had the training last year.

Like Hannah said, most of the time they have a problem unraveling it and understanding how to actually place it. It’s easier on the arm than it is on the leg. You can imagine it would be harder to place it on your own leg, especially if you had an injury. Then, they don’t tighten it well enough, as Hannah just mentioned. In order for a tourniquet to really be placed properly, it’s going to hurt that person. Many people have that tendency not to want to tighten it as much as they can.

Having said that, how I got into all of this is because I’m the medical director for Coral Springs and Parkland, and unfortunately, we had the 2018 Valentine’s Day murders that happened where we lost 17 adults and kids. However, 17 people were saved that day, and the credit goes to our police officers who had tourniquets or chest seals on before those patients were brought out to EMS. Many lives were saved by the tourniquet.

If you look at the Boston Marathon massacre and many other events that have happened, I believe — and I’ve always believed — that tourniquets should be in the glove box of every citizen. It should be in every school room. They should be in buildings along with the AED.

In my town of Davie, we were the first in the country to add an ordinance that required a Stop the Bleed kit in the AED cabinet, and those were required by buildings of certain sizes. In order to get this lifesaving device everywhere, I think it has to be put into local ordinance and supported by states and by the national folks, which they are doing.

Trials Are Underway

Dr. Glatter: In terms of adoption of such a device, it certainly has to go through rigorous testing and maybe some trials. Hannah, where are you at with vetting this in terms of any type of trial? Has it been compared head to head with standard tourniquets?

Ms. Herbst: Yes, we’re currently doing large amounts of field testing. We’re doing testing on emergency vehicles and in the surgical setting with different customers. In addition, we’re running pilot studies at different universities and with different organizations, including the military, to make sure that this device is effective. We’re evaluating cognitive offloading of people. We’re hoping to start that study later this year. We’re excited to be doing this in a variety of settings.

We’re also testing the quality of it in different environmental conditions and under different atmospheric pressure. We’re doing everything we can to ensure the device is safe and effective. We’re excited to scale and fill our preorders and be able to develop this and deliver it to many people.

Dr. Glatter: I was wondering if you could describe the actual device. There’s a brain part of it and then, obviously, the strap aspect of it. I was curious about contamination and reusability issues.

Ms. Herbst: That’s a great question. One of the limitations of conventional tourniquets on the market is that they are single use, and often, it requires two tourniquets to stop a bleed, both of which have to be disposed of.

With AutoTQ, we have a reusable component and a disposable component. I actually have one here that I can show you. We have a cover on it that says: Stop bleed, slide up and power on. You just pull this cover off and then you have a few simple commands. You have powering the device on. I’ll just click this button: Tighten strap above bleeding, then press inflate. It delivers audible instructions telling you exactly how to use the device. Then, you tighten it above your bleed on the limb, and you press the inflate button. Then it administers air into the cuff and stops the patient’s bleed.

Tourniquet Conversion and Limb Salvage

Dr. Glatter: In terms of ischemia time, how can a device like this make it easier for us to know when to let the tourniquet down and allow some blood flow? Certainly, limb salvage is important, and we don’t want to have necrosis and so forth.

Dr. Antevy: That’s a great question. The limb salvage rate when tourniquets have been used is 85%. When used correctly, you can really improve the outcomes for many patients.

On the flip side of that, there’s something called tourniquet conversion. That’s exactly what you mentioned. It’s making sure that the tourniquet doesn’t stay on for too long of a time. If you can imagine a patient going to an outlying hospital where there’s no trauma center, and then that patient then has to be moved a couple hours to the trauma center, could you potentially have a tourniquet on for too long that then ends up causing the patient a bad outcome? The answer is yes.

I just had someone on my webinar recently describing the appropriate conversion techniques of tourniquets. You don’t find too much of that in the literature, but you really have to ensure that as you’re taking the tourniquet down, the bleeding is actually stopped. It’s not really recommended to take a tourniquet down if the patient was just acutely bleeding.

However, imagine a situation where a tourniquet was put on incorrectly. Let’s say a patient got nervous and they just put it on a patient who didn’t really need it. You really have to understand how to evaluate that wound to be sure that, as you’re taking the tourniquet down slowly, the patient doesn’t rebleed again.

There are two sides of the question, Rob. One is making sure it’s not on inappropriately. The second one is making sure it’s not on for too long, which ends up causing ischemia to that limb.

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, does your device collect data on the number of hours or minutes that the tourniquet has been up and then automatically deflate it in some sense to allow for that improvement in limb salvage?

Ms. Herbst: That’s a great question, and I really appreciate your answer as well, Dr Antevy. Ischemia time is a very important and critical component of tourniquet use. This is something, when we were designing AutoTQ, that we took into high consideration.

We found, when we evaluated AutoTQ vs a CAT tourniquet in a mannequin model, that AutoTQ can achieve cessation of hemorrhage at around 400 mm Hg of mercury, whereas CAT requires 700-800 mm Hg. Already our ischemia time is slightly extended just based on existing literature with pneumatic tourniquets because it can stop the bleed at a lower pressure, which causes less complications with the patient’s limb.

There are different features that we build out for different customers, so depending on what people want, it is possible to deflate the tourniquet. However, typically, you’re at the hospital within 30 minutes. It’s quick to get them there, and then the physician can treat and take that tourniquet down in a supervised and controlled setting.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of patients with obesity, do you have adjustable straps that will accommodate for that aspect?

Ms. Herbst: Yes, we have different cuff sizes to accommodate different limbs.

Will AutoTQ Be Available to the Public?

Dr. Glatter: Peter, in terms of usability in the prehospital setting, where do you think this is going in the next 3-5 years?

Dr. Antevy: I’ll start with the public safety sector of the United States, which is the one that is actually first on scene. Whether you’re talking about police officers or EMS, it would behoove us to have tourniquets everywhere. On all of my ambulances, across all of my agencies that I manage, we have quite a number of tourniquets.

Obviously, cost is a factor, and I know that Hannah has done a great job of making that brain reusable. All we have to do is purchase the straps, which are effectively the same cost, I understand, as a typical tourniquet you would purchase.

Moving forward though, however, I think that this has wide scalability to the public market, whether it be schools, office buildings, the glove box, and so on. It’s really impossible to teach somebody how to do this the right way, if you have to teach them how to put the strap on, tighten it correctly, and so on. If there was an easy way, like Hannah developed, of just putting it on and pushing a button, then I think that the outcomes and the scalability are much further beyond what we can do in EMS. I think there’s great value in both markets.

The ‘AED of Bleeding’: Rechargeable and Reusable

Dr. Glatter: This is the AED of bleeding. You have a device here that has wide-scale interest, certainly from the public and private sector.

Hannah, in terms of battery decay, how would that work out if it was in someone’s garage? Let’s just say someone purchased it and they hadn’t used it in 3 or 4 months. What type of decay are we looking at and can they rely on it?

Ms. Herbst: AutoTQ is rechargeable by a USB-C port, and our battery lasts for a year. Once a year, you’ll get an email reminder that says: “Hey, please charge your AutoTQ and make sure it’s up to the battery level.” We do everything in our power to make sure that our consumers are checking their batteries and that they’re ready to go.

Dr. Glatter: Is it heat and fire resistant? What, in terms of durability, does your device have?

Ms. Herbst: Just like any other medical device, we come with manufacturer recommendations for the upper and lower bounds of temperature and different storage recommendations. All of that is in our instructions for use.

Dr. Glatter: Peter, getting back to logistics. In terms of adoption, do you feel that, in the long term, this device will be something that we’re going to be seeing widely adopted just going forward?

Dr. Antevy: I do, and I’ll tell you why. When you look at AED use in this country, the odds of someone actually getting an AED and using it correctly are still very low. Part of that is because it’s complicated for many people to do. Getting tourniquets everywhere is step No. 1, and I think the federal government and the Stop the Bleed program is really making that happen.

We talked about ordinances, but ease of use, I think, is really the key. You have people who oftentimes have their child in cardiac arrest in front of them, and they won’t put two hands on their chest because they just are afraid of doing it.

When you have a device that’s a tourniquet, that’s a single-button turn on and single-button inflate, I think that would make it much more likely that a person will use that device when they’re passing the scene of an accident, as an example.

We’ve had many non–mass casualty incident events that have had tourniquets. We’ve had some media stories on them, where they’re just happening because someone got into a motor vehicle accident. It doesn’t have to be a school shooting. I think the tourniquets should be everywhere and should be easily used by everybody.

Managing Pain

Dr. Glatter: Regarding sedation, is there a need because of the pain involved with the application? How would you sedate a patient, pediatric or adult, who needs a tourniquet?

Dr. Antevy: We always evaluate people’s pain. If the patient is an extremist, we’re just going to be managing and trying to get them back to life. Once somebody is stabilized and is exhibiting pain of any sort, even, for example, after we intubate somebody, we have to sedate them and provide them pain control because they have a piece of plastic in their trachea.

It’s the same thing here for a tourniquet. These are painful, and we do have the appropriate medications on our vehicles to address that pain. Again, just simply the trauma itself is very painful. Yes, we do address that in EMS, and I would say most public agencies across this country would address pain appropriately.

Training on Tourniquet Use

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, can you talk a little bit about public training types of approaches? How would you train a consumer who purchases this type of device?

Ms. Herbst: A huge part of our mission is making blood loss prevention and control training accessible to a wide variety of people. One way that we’re able to do that is through our online training platform. When you purchase an AutoTQ kit, you plug it into your computer, and it walks you through the process of using it. It lets you practice on your own limb and on your buddy’s limb, just to be able to effectively apply it. We think this will have huge impacts in making sure that people are prepared and ready to stop the bleed with AutoTQ.

Dr. Glatter: Do you recommend people training once a month, in general, just to keep their skills up to use this? In the throes of a trauma and very chaotic situation, people sometimes lose their ability to think clearly and straightly.

Ms. Herbst: One of the studies we’re conducting is a learning curve study to try to figure out how quickly these skills degrade over time. We know that with the windlass tourniquet, it degrades within moments of training. With AutoTQ, we think the learning curve will last much longer. That’s something we’re evaluating, but we recommend people train as often as they can.

Dr. Antevy: Rob, if I can mention that there is a concept of just-in-time training. I think that with having the expectation that people are going to be training frequently, unfortunately, as many of us know, even with the AED as a perfect example, people don’t do that.

Yes. I would agree that you have to train at least once a year, is what I would say. At my office, we have a 2-hour training that goes over all these different items once a year.

The device itself should have the ability to allow you to figure out how to use it just in time, whether via video, or like Hannah’s device, by audio. I think that having both those things would make it more likely that the device be used when needed.

People panic, and if they have a device that can talk to them or walk them through it, they will be much more likely to use it at that time.

Final Takeaways

Dr. Glatter: Any other final thoughts or a few pearls for listeners to take away? Hannah, I’ll start with you.

Ms. Herbst: I’m very grateful for your time, and I’m very excited about the potential for AutoTQ. To me, it’s so exciting to see people preordering the device now. We’ve had people from school bus companies and small sports teams. I think, just like Dr Antevy said, tourniquets aren’t limited to mass casualty situations. Blood loss can happen anywhere and to anyone.

Being able to equip people and serve them to better prepare them for this happening to themselves, their friends, or their family is just the honor of a lifetime. Thank you very much for covering the device and for having me today.

Dr. Glatter: Of course, my pleasure. Peter?

Dr. Antevy: The citizens of this country, and everyone who lives across the world, has started to understand that there are things that we expect from our people, from the community. We expect them to do CPR for cardiac arrest. We expect them to know how to use an EpiPen. We expect them to know how to use an AED, and we also expect them to know how to stop bleeding with a tourniquet.

The American public has gotten to understand that these devices are very important. Having a device that’s easily used, that I can teach you in 10 seconds, that speaks to you — these are all things that make this product have great potential. I do look forward to the studies, not just the cadaver studies, but the real human studies.

I know Hannah is really a phenom and has been doing all these things so that this product can be on the shelves of Walmart and CVS one day. I commend you, Hannah, for everything you’re doing and wishing you the best of luck. We’re here for you.

Dr. Glatter: Same here. Congratulations on your innovative capability and what you’ve done to change the outcomes of bleeding related to penetrating trauma. Thank you so much.

Robert D. Glatter, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is a medical advisor for Medscape and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series. Hannah D. Herbst, BS, is a graduate of Florida Atlantic University, was selected for Forbes 30 Under 30, and is the founder/CEO of Golden Hour Medical. Peter M. Antevy, MD, is a pediatric emergency medicine physician and medical director for Davie Fire Rescue and Coral Springs–Parkland Fire Department in Florida. He is also a member of the EMS Eagles Global Alliance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on July 12, 2024. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Hi and welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. I recently met an innovative young woman named Hannah Herbst while attending the annual Eagles EMS Conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Hannah Herbst is a graduate of Florida Atlantic University, selected for Forbes 30 Under 30, and founder of a company called Golden Hour Medical. She has a background in IT and developed an automated pneumatic tourniquet known as AutoTQ, which we’re going to discuss at length here.

Also joining us is Dr. Peter Antevy, a pediatric emergency physician and medical director for Davie Fire Rescue as well as Coral Springs Parkland Fire Rescue. Peter is a member of EMS Eagles Global Alliance and is highly involved in high-quality research in prehospital emergency care and is quite well known in Florida and nationally.

Welcome to both of you.

Hannah Herbst: Thank you very much. Very grateful to be here.

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, I’ll let you start by explaining what AutoTQ is and then compare that to a standard Combat Application Tourniquet (CAT).

Ms. Herbst: Thank you. Unfortunately, blood loss is a leading cause of preventable death and trauma. When there’s blood loss occurring from an arm or a leg, the easiest way to stop it is by applying a tourniquet, which is this compression type of device that you place above the site of bleeding, and it then applies a high amount of pressure to stop blood flow through the limb.

Currently, tourniquets on the market have failure rates as high as 84%. This became very real to me back in 2018, when I became aware of mass casualty incidents when I was a student. I became interested in how we can reimagine the conventional tourniquet and try to make it something that’s very user-friendly, much like an automated external defibrillator (AED).

My team and I developed AutoTQ, which is an automated tourniquet. which is a leading cause of tourniquet failure and being able to effectively administer treatment to a patient that may bleed out.

Tourniquet Failure Rates

Dr. Glatter: In terms of tourniquet failure, how often do standard tourniquets fail, like the CAT combat-type tourniquet?

Ms. Herbst: Unfortunately, they fail very frequently. There are several studies that have been conducted to evaluate this. Many of them occur immediately after training. They found failure rates between 80% and 90% for the current conventional CAT tourniquet immediately after training, which is very concerning.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of failure, was it the windlass aspect of the tourniquet that failed? Or was it something related to the actual strap? Was that in any way detailed?

Ms. Herbst: There are usually a few different failure points that have been found in the literature. One is placement. Many times, when you’re panicked, you don’t remember exactly how to place it. It should be placed high and tight above the bleed and not over a joint.

The second problem is inadequate tightness. For a CAT tourniquet to be effective, you have to get it extremely tight on that first pull before the windlass is activated, and many times people don’t remember that in the stress of the moment.

Dr. Glatter: Peter, in terms of tourniquet application by your medics in the field, certainly the CAT-type device has been in existence for quite a while. Hannah’s proposing a new iteration of how to do this, which is automated and simple. What is your take on such a device? And how did you learn about Hannah’s device?

Peter M. Antevy, MD: We’ve been training on tourniquets ever since the military data showed that there was an extreme benefit in using them. We’ve been doing training for many years, including our police officers. What we’ve noticed is that every time we gather everyone together to show them how to place a tourniquet — and we have to do one-on-one sessions with them — it’s not a device that they can easily put on. These are police officers who had the training last year.

Like Hannah said, most of the time they have a problem unraveling it and understanding how to actually place it. It’s easier on the arm than it is on the leg. You can imagine it would be harder to place it on your own leg, especially if you had an injury. Then, they don’t tighten it well enough, as Hannah just mentioned. In order for a tourniquet to really be placed properly, it’s going to hurt that person. Many people have that tendency not to want to tighten it as much as they can.

Having said that, how I got into all of this is because I’m the medical director for Coral Springs and Parkland, and unfortunately, we had the 2018 Valentine’s Day murders that happened where we lost 17 adults and kids. However, 17 people were saved that day, and the credit goes to our police officers who had tourniquets or chest seals on before those patients were brought out to EMS. Many lives were saved by the tourniquet.

If you look at the Boston Marathon massacre and many other events that have happened, I believe — and I’ve always believed — that tourniquets should be in the glove box of every citizen. It should be in every school room. They should be in buildings along with the AED.

In my town of Davie, we were the first in the country to add an ordinance that required a Stop the Bleed kit in the AED cabinet, and those were required by buildings of certain sizes. In order to get this lifesaving device everywhere, I think it has to be put into local ordinance and supported by states and by the national folks, which they are doing.

Trials Are Underway

Dr. Glatter: In terms of adoption of such a device, it certainly has to go through rigorous testing and maybe some trials. Hannah, where are you at with vetting this in terms of any type of trial? Has it been compared head to head with standard tourniquets?

Ms. Herbst: Yes, we’re currently doing large amounts of field testing. We’re doing testing on emergency vehicles and in the surgical setting with different customers. In addition, we’re running pilot studies at different universities and with different organizations, including the military, to make sure that this device is effective. We’re evaluating cognitive offloading of people. We’re hoping to start that study later this year. We’re excited to be doing this in a variety of settings.

We’re also testing the quality of it in different environmental conditions and under different atmospheric pressure. We’re doing everything we can to ensure the device is safe and effective. We’re excited to scale and fill our preorders and be able to develop this and deliver it to many people.

Dr. Glatter: I was wondering if you could describe the actual device. There’s a brain part of it and then, obviously, the strap aspect of it. I was curious about contamination and reusability issues.

Ms. Herbst: That’s a great question. One of the limitations of conventional tourniquets on the market is that they are single use, and often, it requires two tourniquets to stop a bleed, both of which have to be disposed of.

With AutoTQ, we have a reusable component and a disposable component. I actually have one here that I can show you. We have a cover on it that says: Stop bleed, slide up and power on. You just pull this cover off and then you have a few simple commands. You have powering the device on. I’ll just click this button: Tighten strap above bleeding, then press inflate. It delivers audible instructions telling you exactly how to use the device. Then, you tighten it above your bleed on the limb, and you press the inflate button. Then it administers air into the cuff and stops the patient’s bleed.

Tourniquet Conversion and Limb Salvage

Dr. Glatter: In terms of ischemia time, how can a device like this make it easier for us to know when to let the tourniquet down and allow some blood flow? Certainly, limb salvage is important, and we don’t want to have necrosis and so forth.

Dr. Antevy: That’s a great question. The limb salvage rate when tourniquets have been used is 85%. When used correctly, you can really improve the outcomes for many patients.

On the flip side of that, there’s something called tourniquet conversion. That’s exactly what you mentioned. It’s making sure that the tourniquet doesn’t stay on for too long of a time. If you can imagine a patient going to an outlying hospital where there’s no trauma center, and then that patient then has to be moved a couple hours to the trauma center, could you potentially have a tourniquet on for too long that then ends up causing the patient a bad outcome? The answer is yes.

I just had someone on my webinar recently describing the appropriate conversion techniques of tourniquets. You don’t find too much of that in the literature, but you really have to ensure that as you’re taking the tourniquet down, the bleeding is actually stopped. It’s not really recommended to take a tourniquet down if the patient was just acutely bleeding.

However, imagine a situation where a tourniquet was put on incorrectly. Let’s say a patient got nervous and they just put it on a patient who didn’t really need it. You really have to understand how to evaluate that wound to be sure that, as you’re taking the tourniquet down slowly, the patient doesn’t rebleed again.

There are two sides of the question, Rob. One is making sure it’s not on inappropriately. The second one is making sure it’s not on for too long, which ends up causing ischemia to that limb.

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, does your device collect data on the number of hours or minutes that the tourniquet has been up and then automatically deflate it in some sense to allow for that improvement in limb salvage?

Ms. Herbst: That’s a great question, and I really appreciate your answer as well, Dr Antevy. Ischemia time is a very important and critical component of tourniquet use. This is something, when we were designing AutoTQ, that we took into high consideration.

We found, when we evaluated AutoTQ vs a CAT tourniquet in a mannequin model, that AutoTQ can achieve cessation of hemorrhage at around 400 mm Hg of mercury, whereas CAT requires 700-800 mm Hg. Already our ischemia time is slightly extended just based on existing literature with pneumatic tourniquets because it can stop the bleed at a lower pressure, which causes less complications with the patient’s limb.

There are different features that we build out for different customers, so depending on what people want, it is possible to deflate the tourniquet. However, typically, you’re at the hospital within 30 minutes. It’s quick to get them there, and then the physician can treat and take that tourniquet down in a supervised and controlled setting.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of patients with obesity, do you have adjustable straps that will accommodate for that aspect?

Ms. Herbst: Yes, we have different cuff sizes to accommodate different limbs.

Will AutoTQ Be Available to the Public?

Dr. Glatter: Peter, in terms of usability in the prehospital setting, where do you think this is going in the next 3-5 years?

Dr. Antevy: I’ll start with the public safety sector of the United States, which is the one that is actually first on scene. Whether you’re talking about police officers or EMS, it would behoove us to have tourniquets everywhere. On all of my ambulances, across all of my agencies that I manage, we have quite a number of tourniquets.

Obviously, cost is a factor, and I know that Hannah has done a great job of making that brain reusable. All we have to do is purchase the straps, which are effectively the same cost, I understand, as a typical tourniquet you would purchase.

Moving forward though, however, I think that this has wide scalability to the public market, whether it be schools, office buildings, the glove box, and so on. It’s really impossible to teach somebody how to do this the right way, if you have to teach them how to put the strap on, tighten it correctly, and so on. If there was an easy way, like Hannah developed, of just putting it on and pushing a button, then I think that the outcomes and the scalability are much further beyond what we can do in EMS. I think there’s great value in both markets.

The ‘AED of Bleeding’: Rechargeable and Reusable

Dr. Glatter: This is the AED of bleeding. You have a device here that has wide-scale interest, certainly from the public and private sector.

Hannah, in terms of battery decay, how would that work out if it was in someone’s garage? Let’s just say someone purchased it and they hadn’t used it in 3 or 4 months. What type of decay are we looking at and can they rely on it?

Ms. Herbst: AutoTQ is rechargeable by a USB-C port, and our battery lasts for a year. Once a year, you’ll get an email reminder that says: “Hey, please charge your AutoTQ and make sure it’s up to the battery level.” We do everything in our power to make sure that our consumers are checking their batteries and that they’re ready to go.

Dr. Glatter: Is it heat and fire resistant? What, in terms of durability, does your device have?

Ms. Herbst: Just like any other medical device, we come with manufacturer recommendations for the upper and lower bounds of temperature and different storage recommendations. All of that is in our instructions for use.

Dr. Glatter: Peter, getting back to logistics. In terms of adoption, do you feel that, in the long term, this device will be something that we’re going to be seeing widely adopted just going forward?

Dr. Antevy: I do, and I’ll tell you why. When you look at AED use in this country, the odds of someone actually getting an AED and using it correctly are still very low. Part of that is because it’s complicated for many people to do. Getting tourniquets everywhere is step No. 1, and I think the federal government and the Stop the Bleed program is really making that happen.

We talked about ordinances, but ease of use, I think, is really the key. You have people who oftentimes have their child in cardiac arrest in front of them, and they won’t put two hands on their chest because they just are afraid of doing it.

When you have a device that’s a tourniquet, that’s a single-button turn on and single-button inflate, I think that would make it much more likely that a person will use that device when they’re passing the scene of an accident, as an example.

We’ve had many non–mass casualty incident events that have had tourniquets. We’ve had some media stories on them, where they’re just happening because someone got into a motor vehicle accident. It doesn’t have to be a school shooting. I think the tourniquets should be everywhere and should be easily used by everybody.

Managing Pain

Dr. Glatter: Regarding sedation, is there a need because of the pain involved with the application? How would you sedate a patient, pediatric or adult, who needs a tourniquet?

Dr. Antevy: We always evaluate people’s pain. If the patient is an extremist, we’re just going to be managing and trying to get them back to life. Once somebody is stabilized and is exhibiting pain of any sort, even, for example, after we intubate somebody, we have to sedate them and provide them pain control because they have a piece of plastic in their trachea.

It’s the same thing here for a tourniquet. These are painful, and we do have the appropriate medications on our vehicles to address that pain. Again, just simply the trauma itself is very painful. Yes, we do address that in EMS, and I would say most public agencies across this country would address pain appropriately.

Training on Tourniquet Use

Dr. Glatter: Hannah, can you talk a little bit about public training types of approaches? How would you train a consumer who purchases this type of device?

Ms. Herbst: A huge part of our mission is making blood loss prevention and control training accessible to a wide variety of people. One way that we’re able to do that is through our online training platform. When you purchase an AutoTQ kit, you plug it into your computer, and it walks you through the process of using it. It lets you practice on your own limb and on your buddy’s limb, just to be able to effectively apply it. We think this will have huge impacts in making sure that people are prepared and ready to stop the bleed with AutoTQ.

Dr. Glatter: Do you recommend people training once a month, in general, just to keep their skills up to use this? In the throes of a trauma and very chaotic situation, people sometimes lose their ability to think clearly and straightly.

Ms. Herbst: One of the studies we’re conducting is a learning curve study to try to figure out how quickly these skills degrade over time. We know that with the windlass tourniquet, it degrades within moments of training. With AutoTQ, we think the learning curve will last much longer. That’s something we’re evaluating, but we recommend people train as often as they can.

Dr. Antevy: Rob, if I can mention that there is a concept of just-in-time training. I think that with having the expectation that people are going to be training frequently, unfortunately, as many of us know, even with the AED as a perfect example, people don’t do that.

Yes. I would agree that you have to train at least once a year, is what I would say. At my office, we have a 2-hour training that goes over all these different items once a year.

The device itself should have the ability to allow you to figure out how to use it just in time, whether via video, or like Hannah’s device, by audio. I think that having both those things would make it more likely that the device be used when needed.