User login

Inactivated flu vaccine more effective than live version

The inactivated influenza vaccine is more effective than the quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine, according to a study conducted by the Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

After poor live vaccine performance in young children during the 2013-2014 flu season, the A(H1N1)pdm09 strain was changed. In response to earlier reports that the A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine strain had poor thermostability, it was updated to A/Bolivia/559/2013 (an A/California/7/2009-like virus) for the 2015-2016 influenza season. Unfortunately, the changes did not increase the vaccine’s immunogenicity. At study sites in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin, 6,879 patients aged 6 months or older who presented for acute respiratory illness with a cough of 7 or fewer days were tested for influenza. Of those, 1,309 (19%) tested positive. Vaccination histories were taken from parent interviews and electronic health records.

“Although the quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine remains licensed in the United States, the [Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] did not recommend this vaccine for the 2016-2017 influenza season,” the investigators wrote.

Partial funding for the research came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jackson reported receiving a grant from Medimmune.

Read more in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;377:534-43).

The inactivated influenza vaccine is more effective than the quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine, according to a study conducted by the Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

After poor live vaccine performance in young children during the 2013-2014 flu season, the A(H1N1)pdm09 strain was changed. In response to earlier reports that the A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine strain had poor thermostability, it was updated to A/Bolivia/559/2013 (an A/California/7/2009-like virus) for the 2015-2016 influenza season. Unfortunately, the changes did not increase the vaccine’s immunogenicity. At study sites in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin, 6,879 patients aged 6 months or older who presented for acute respiratory illness with a cough of 7 or fewer days were tested for influenza. Of those, 1,309 (19%) tested positive. Vaccination histories were taken from parent interviews and electronic health records.

“Although the quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine remains licensed in the United States, the [Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] did not recommend this vaccine for the 2016-2017 influenza season,” the investigators wrote.

Partial funding for the research came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jackson reported receiving a grant from Medimmune.

Read more in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;377:534-43).

The inactivated influenza vaccine is more effective than the quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine, according to a study conducted by the Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

After poor live vaccine performance in young children during the 2013-2014 flu season, the A(H1N1)pdm09 strain was changed. In response to earlier reports that the A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine strain had poor thermostability, it was updated to A/Bolivia/559/2013 (an A/California/7/2009-like virus) for the 2015-2016 influenza season. Unfortunately, the changes did not increase the vaccine’s immunogenicity. At study sites in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin, 6,879 patients aged 6 months or older who presented for acute respiratory illness with a cough of 7 or fewer days were tested for influenza. Of those, 1,309 (19%) tested positive. Vaccination histories were taken from parent interviews and electronic health records.

“Although the quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine remains licensed in the United States, the [Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] did not recommend this vaccine for the 2016-2017 influenza season,” the investigators wrote.

Partial funding for the research came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jackson reported receiving a grant from Medimmune.

Read more in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;377:534-43).

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

HPV vaccination rose after ACA implementation

Human papillomavirus vaccination in girls and women has increased significantly since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), according an analysis of federal survey data.

Overall, girls and women were 3.3 times more likely to receive the vaccine (95% confidence interval, 2.0, 5.5; P less than .0001) in the post–ACA implementation period, compared with the pre-ACA period. They were 5.8 times more likely to receive all three doses of the vaccine (95% CI, 2.5-13.6; P = .0001) post ACA, compared with one dose during that period, according to Rosemary Corriero of the University of Georgia, Athens, who is also a fellow at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her coauthors (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017 Jul 26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.07.002).

The cross-sectional analysis included four waves of data from 2007-2008, 2009-2010, 2011-2012, and 2013-2014 – two waves before the ACA and two waves after. The data comes from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) questionnaire. In the pre-ACA surveys, 2,452 teenage girls and women were included, compared with 2,147 in the post-ACA years. The majority of participants were white, and analysis was limited to those aged 9-33 years.

The increase in vaccination could be due to the ACA’s provision requiring coverage of preventive health services without patient cost sharing in most health plans, but the investigators couldn’t say for sure.

Vaccination uptake was significantly higher for those with insurance coverage in both pre- and post-ACA groups (P = .0007 and P = .01, respectively).

Despite these increases, vaccination rates are still low. There has been progress, but “physicians and public health professionals could assist in the acceleration of HPV vaccination uptake by increasing communication of HPV vaccination importance and by utilizing campaigns and materials that are readily available,” the investigators wrote.

The study was limited by a lack of data for teenage boys and men before implementation of the ACA and by the overlap in pre- and post-ACA data in the 2009-2010 wave because of the timing of the provision. Additionally, the data was self-reported.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Human papillomavirus vaccination in girls and women has increased significantly since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), according an analysis of federal survey data.

Overall, girls and women were 3.3 times more likely to receive the vaccine (95% confidence interval, 2.0, 5.5; P less than .0001) in the post–ACA implementation period, compared with the pre-ACA period. They were 5.8 times more likely to receive all three doses of the vaccine (95% CI, 2.5-13.6; P = .0001) post ACA, compared with one dose during that period, according to Rosemary Corriero of the University of Georgia, Athens, who is also a fellow at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her coauthors (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017 Jul 26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.07.002).

The cross-sectional analysis included four waves of data from 2007-2008, 2009-2010, 2011-2012, and 2013-2014 – two waves before the ACA and two waves after. The data comes from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) questionnaire. In the pre-ACA surveys, 2,452 teenage girls and women were included, compared with 2,147 in the post-ACA years. The majority of participants were white, and analysis was limited to those aged 9-33 years.

The increase in vaccination could be due to the ACA’s provision requiring coverage of preventive health services without patient cost sharing in most health plans, but the investigators couldn’t say for sure.

Vaccination uptake was significantly higher for those with insurance coverage in both pre- and post-ACA groups (P = .0007 and P = .01, respectively).

Despite these increases, vaccination rates are still low. There has been progress, but “physicians and public health professionals could assist in the acceleration of HPV vaccination uptake by increasing communication of HPV vaccination importance and by utilizing campaigns and materials that are readily available,” the investigators wrote.

The study was limited by a lack of data for teenage boys and men before implementation of the ACA and by the overlap in pre- and post-ACA data in the 2009-2010 wave because of the timing of the provision. Additionally, the data was self-reported.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Human papillomavirus vaccination in girls and women has increased significantly since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), according an analysis of federal survey data.

Overall, girls and women were 3.3 times more likely to receive the vaccine (95% confidence interval, 2.0, 5.5; P less than .0001) in the post–ACA implementation period, compared with the pre-ACA period. They were 5.8 times more likely to receive all three doses of the vaccine (95% CI, 2.5-13.6; P = .0001) post ACA, compared with one dose during that period, according to Rosemary Corriero of the University of Georgia, Athens, who is also a fellow at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her coauthors (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017 Jul 26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.07.002).

The cross-sectional analysis included four waves of data from 2007-2008, 2009-2010, 2011-2012, and 2013-2014 – two waves before the ACA and two waves after. The data comes from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) questionnaire. In the pre-ACA surveys, 2,452 teenage girls and women were included, compared with 2,147 in the post-ACA years. The majority of participants were white, and analysis was limited to those aged 9-33 years.

The increase in vaccination could be due to the ACA’s provision requiring coverage of preventive health services without patient cost sharing in most health plans, but the investigators couldn’t say for sure.

Vaccination uptake was significantly higher for those with insurance coverage in both pre- and post-ACA groups (P = .0007 and P = .01, respectively).

Despite these increases, vaccination rates are still low. There has been progress, but “physicians and public health professionals could assist in the acceleration of HPV vaccination uptake by increasing communication of HPV vaccination importance and by utilizing campaigns and materials that are readily available,” the investigators wrote.

The study was limited by a lack of data for teenage boys and men before implementation of the ACA and by the overlap in pre- and post-ACA data in the 2009-2010 wave because of the timing of the provision. Additionally, the data was self-reported.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC & ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Girls and women were 3.3 times more likely to receive the HPV vaccine in the period after the ACA was implemented (95% confidence interval, 2.0-5.5; P less than .0001).

Data source: A cross-sectional analysis of the NHANES questionnaire that included responses from more than 4,500 girls and women aged 9-33 years.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Optimizing HPV vaccination

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection. Exposure is widespread and most individuals clear the infection without symptoms or development of disease. However, a subset of individuals experience persistent infection, a state which can lead to carcinogenesis of lower genital tract malignancies, particularly cervical cancer.1

Vaccine coverage

Persistent infection with high-risk (oncogenic) HPV is well known to be the cause of cervical cancer. There are two HPV vaccines manufactured for the purposes of cervical cancer, anal cancer, and genital wart prevention (Cervarix and Gardasil). The Cervarix vaccine covers high-risk HPV subtypes 16 and 18 and the Gardasil vaccine prevents both low-risk HPV subtypes 6 and 11, which can cause genital warts, and high-risk HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58, which cause cervical dysplasia and cancer.

High-risk HPV is also associated with head and neck, vulvar, vaginal, and penile cancers, though the vaccines are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for prevention of these diseases.2

Vaccination indications

Since vaccination prevents multiple subtypes of HPV, an individual who has already been exposed will still benefit from protection from other subtypes of HPV through vaccination. HPV vaccination is not approved during pregnancy but can be initiated in the postpartum period when women are engaged in their health care and receiving other vaccinations, such as varicella or the MMR vaccine.

Recommended schedule

Until October 2016, the vaccination schedule was based on a three-dose series (0, 2, and 6 months). Currently, the CDC recommends that children aged under 15 years at the time of first dose may opt for a two-dose series (0 and 6-12 months). For those aged 15-26 years, the three-dose schedule remains the recommended course.

The benefits of two-dose schedule are convenience, cost, and increased likelihood of completion. Data presented at the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer showed that rates of cervical dysplasia were equivalent for women who completed a two-dose schedule versus a three-dose schedule.4

Efficacy

A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials of the HPV vaccines describe efficacy of 95%-97% in prevention of CIN 1-3.5 While its greatest efficacy is in its ability to prevent primary HPV infection, there still is some benefit for individuals who already were exposed to HPV prior to vaccination. As stated previously, women with a history of prior HPV vaccination have lower rates of recurrence of cervical dysplasia after treatment. Additionally, recent research has shown that women who received HPV vaccinations after a LEEP procedure for CIN 2 or 3 experience significantly lower recurrence rates, compared with women who did not receive vaccinations after LEEP (2.5% vs. 8.5%).6 This raises the possibility of a therapeutic role for HPV vaccination in women infected with HPV. Prospective studies are currently evaluating this question.

Myths

The most common side effects of the HPV vaccine are pain, redness, or swelling at the injection site. Other known side effects include fever, headache or malaise, nausea, syncope, or muscle/joint pain – similar to other vaccinations. Anaphylaxis is a rare complication.

Some parents and pediatricians report concerns that vaccination could lead to earlier sexual activity. Multiple studies have shown that girls who receive HPV vaccination are no more likely to become pregnant or get a sexually transmitted infection (proxies for intercourse) than are girls who were not vaccinated.7,8

Maximizing vaccination rates

HPV vaccination rates in the United States lag significantly behind rates in countries with national vaccine programs, such as Australia and Denmark.9 Early data from Australia already have shown a decrease in genital warts and CIN 2+ incidence within the 10 years of starting its school-based vaccine program, with approximately 73% of 12- to 15-year-olds having completed the vaccine series.2 In contrast, just 40% and 22% of 13- to 17-year-old girls and boys in the United States, respectively, had completed the vaccine series in 2014, according to the CDC.10

Vaccination gaps between girls and boys are narrowing, and more teens will be able to complete the series with the new two-dose recommendation for those younger than 15 years. However, our current rates of vaccination are significantly lower for HPV than for other routinely recommended adolescent vaccines (such as Tdap and meningococcal) and more must be done to encourage vaccination.

Studies have shown that parents are more likely to vaccinate their children if providers recommend the vaccine.11 As women’s health care providers, we do not always see children during the time period that is ideal for vaccination. However, we take care of many women who are presenting for routine gynecologic care, pregnancy, or with abnormal Pap smear screenings. These are ideal opportunities to educate and offer HPV vaccination to women in the approved age groups, as well as to encourage parents to vaccinate their children.

As with other vaccines, the recommendation should be clear and focused on the cancer prevention benefit. Using methods in which the recommendation is “announced” in a brief statement assuming parents/patients are ready to vaccinate versus open-ended conversations, has been studied as a potentially successful method to increase uptake of HPV vaccination.12 Additionally, documentation of HPV vaccination status should be built into electronic medical record templates to prompt clinicians to ask and offer HPV vaccination at visits, including postpartum visits.

Dr. Rahangdale is an associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and is director of the North Carolina Women’s Hospital Cervical Dysplasia Clinic. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Jul 15;168(2):123-37.

2. Int J Cancer. 2012 Nov 1;131(9):1969-82.

3. BMJ. 2012 Mar 27;344:e1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1401.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Jun. doi. org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.031.

5. Int J Prev Med. 2017 Jun 1;8:44. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_413_16.

6. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Aug;130(2):264-8.

7. Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130(5):798-805.

8. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):617-23.

9. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016 Sep;55(10):904-14.

10. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Jul 31;64(29):784-92.

11. Vaccine. 2016 Feb 24;34(9):1187-92.

12. Pediatrics. 2017 Jan;139(1). pii:e20161764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1764.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection. Exposure is widespread and most individuals clear the infection without symptoms or development of disease. However, a subset of individuals experience persistent infection, a state which can lead to carcinogenesis of lower genital tract malignancies, particularly cervical cancer.1

Vaccine coverage

Persistent infection with high-risk (oncogenic) HPV is well known to be the cause of cervical cancer. There are two HPV vaccines manufactured for the purposes of cervical cancer, anal cancer, and genital wart prevention (Cervarix and Gardasil). The Cervarix vaccine covers high-risk HPV subtypes 16 and 18 and the Gardasil vaccine prevents both low-risk HPV subtypes 6 and 11, which can cause genital warts, and high-risk HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58, which cause cervical dysplasia and cancer.

High-risk HPV is also associated with head and neck, vulvar, vaginal, and penile cancers, though the vaccines are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for prevention of these diseases.2

Vaccination indications

Since vaccination prevents multiple subtypes of HPV, an individual who has already been exposed will still benefit from protection from other subtypes of HPV through vaccination. HPV vaccination is not approved during pregnancy but can be initiated in the postpartum period when women are engaged in their health care and receiving other vaccinations, such as varicella or the MMR vaccine.

Recommended schedule

Until October 2016, the vaccination schedule was based on a three-dose series (0, 2, and 6 months). Currently, the CDC recommends that children aged under 15 years at the time of first dose may opt for a two-dose series (0 and 6-12 months). For those aged 15-26 years, the three-dose schedule remains the recommended course.

The benefits of two-dose schedule are convenience, cost, and increased likelihood of completion. Data presented at the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer showed that rates of cervical dysplasia were equivalent for women who completed a two-dose schedule versus a three-dose schedule.4

Efficacy

A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials of the HPV vaccines describe efficacy of 95%-97% in prevention of CIN 1-3.5 While its greatest efficacy is in its ability to prevent primary HPV infection, there still is some benefit for individuals who already were exposed to HPV prior to vaccination. As stated previously, women with a history of prior HPV vaccination have lower rates of recurrence of cervical dysplasia after treatment. Additionally, recent research has shown that women who received HPV vaccinations after a LEEP procedure for CIN 2 or 3 experience significantly lower recurrence rates, compared with women who did not receive vaccinations after LEEP (2.5% vs. 8.5%).6 This raises the possibility of a therapeutic role for HPV vaccination in women infected with HPV. Prospective studies are currently evaluating this question.

Myths

The most common side effects of the HPV vaccine are pain, redness, or swelling at the injection site. Other known side effects include fever, headache or malaise, nausea, syncope, or muscle/joint pain – similar to other vaccinations. Anaphylaxis is a rare complication.

Some parents and pediatricians report concerns that vaccination could lead to earlier sexual activity. Multiple studies have shown that girls who receive HPV vaccination are no more likely to become pregnant or get a sexually transmitted infection (proxies for intercourse) than are girls who were not vaccinated.7,8

Maximizing vaccination rates

HPV vaccination rates in the United States lag significantly behind rates in countries with national vaccine programs, such as Australia and Denmark.9 Early data from Australia already have shown a decrease in genital warts and CIN 2+ incidence within the 10 years of starting its school-based vaccine program, with approximately 73% of 12- to 15-year-olds having completed the vaccine series.2 In contrast, just 40% and 22% of 13- to 17-year-old girls and boys in the United States, respectively, had completed the vaccine series in 2014, according to the CDC.10

Vaccination gaps between girls and boys are narrowing, and more teens will be able to complete the series with the new two-dose recommendation for those younger than 15 years. However, our current rates of vaccination are significantly lower for HPV than for other routinely recommended adolescent vaccines (such as Tdap and meningococcal) and more must be done to encourage vaccination.

Studies have shown that parents are more likely to vaccinate their children if providers recommend the vaccine.11 As women’s health care providers, we do not always see children during the time period that is ideal for vaccination. However, we take care of many women who are presenting for routine gynecologic care, pregnancy, or with abnormal Pap smear screenings. These are ideal opportunities to educate and offer HPV vaccination to women in the approved age groups, as well as to encourage parents to vaccinate their children.

As with other vaccines, the recommendation should be clear and focused on the cancer prevention benefit. Using methods in which the recommendation is “announced” in a brief statement assuming parents/patients are ready to vaccinate versus open-ended conversations, has been studied as a potentially successful method to increase uptake of HPV vaccination.12 Additionally, documentation of HPV vaccination status should be built into electronic medical record templates to prompt clinicians to ask and offer HPV vaccination at visits, including postpartum visits.

Dr. Rahangdale is an associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and is director of the North Carolina Women’s Hospital Cervical Dysplasia Clinic. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Jul 15;168(2):123-37.

2. Int J Cancer. 2012 Nov 1;131(9):1969-82.

3. BMJ. 2012 Mar 27;344:e1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1401.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Jun. doi. org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.031.

5. Int J Prev Med. 2017 Jun 1;8:44. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_413_16.

6. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Aug;130(2):264-8.

7. Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130(5):798-805.

8. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):617-23.

9. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016 Sep;55(10):904-14.

10. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Jul 31;64(29):784-92.

11. Vaccine. 2016 Feb 24;34(9):1187-92.

12. Pediatrics. 2017 Jan;139(1). pii:e20161764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1764.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection. Exposure is widespread and most individuals clear the infection without symptoms or development of disease. However, a subset of individuals experience persistent infection, a state which can lead to carcinogenesis of lower genital tract malignancies, particularly cervical cancer.1

Vaccine coverage

Persistent infection with high-risk (oncogenic) HPV is well known to be the cause of cervical cancer. There are two HPV vaccines manufactured for the purposes of cervical cancer, anal cancer, and genital wart prevention (Cervarix and Gardasil). The Cervarix vaccine covers high-risk HPV subtypes 16 and 18 and the Gardasil vaccine prevents both low-risk HPV subtypes 6 and 11, which can cause genital warts, and high-risk HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58, which cause cervical dysplasia and cancer.

High-risk HPV is also associated with head and neck, vulvar, vaginal, and penile cancers, though the vaccines are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for prevention of these diseases.2

Vaccination indications

Since vaccination prevents multiple subtypes of HPV, an individual who has already been exposed will still benefit from protection from other subtypes of HPV through vaccination. HPV vaccination is not approved during pregnancy but can be initiated in the postpartum period when women are engaged in their health care and receiving other vaccinations, such as varicella or the MMR vaccine.

Recommended schedule

Until October 2016, the vaccination schedule was based on a three-dose series (0, 2, and 6 months). Currently, the CDC recommends that children aged under 15 years at the time of first dose may opt for a two-dose series (0 and 6-12 months). For those aged 15-26 years, the three-dose schedule remains the recommended course.

The benefits of two-dose schedule are convenience, cost, and increased likelihood of completion. Data presented at the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer showed that rates of cervical dysplasia were equivalent for women who completed a two-dose schedule versus a three-dose schedule.4

Efficacy

A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials of the HPV vaccines describe efficacy of 95%-97% in prevention of CIN 1-3.5 While its greatest efficacy is in its ability to prevent primary HPV infection, there still is some benefit for individuals who already were exposed to HPV prior to vaccination. As stated previously, women with a history of prior HPV vaccination have lower rates of recurrence of cervical dysplasia after treatment. Additionally, recent research has shown that women who received HPV vaccinations after a LEEP procedure for CIN 2 or 3 experience significantly lower recurrence rates, compared with women who did not receive vaccinations after LEEP (2.5% vs. 8.5%).6 This raises the possibility of a therapeutic role for HPV vaccination in women infected with HPV. Prospective studies are currently evaluating this question.

Myths

The most common side effects of the HPV vaccine are pain, redness, or swelling at the injection site. Other known side effects include fever, headache or malaise, nausea, syncope, or muscle/joint pain – similar to other vaccinations. Anaphylaxis is a rare complication.

Some parents and pediatricians report concerns that vaccination could lead to earlier sexual activity. Multiple studies have shown that girls who receive HPV vaccination are no more likely to become pregnant or get a sexually transmitted infection (proxies for intercourse) than are girls who were not vaccinated.7,8

Maximizing vaccination rates

HPV vaccination rates in the United States lag significantly behind rates in countries with national vaccine programs, such as Australia and Denmark.9 Early data from Australia already have shown a decrease in genital warts and CIN 2+ incidence within the 10 years of starting its school-based vaccine program, with approximately 73% of 12- to 15-year-olds having completed the vaccine series.2 In contrast, just 40% and 22% of 13- to 17-year-old girls and boys in the United States, respectively, had completed the vaccine series in 2014, according to the CDC.10

Vaccination gaps between girls and boys are narrowing, and more teens will be able to complete the series with the new two-dose recommendation for those younger than 15 years. However, our current rates of vaccination are significantly lower for HPV than for other routinely recommended adolescent vaccines (such as Tdap and meningococcal) and more must be done to encourage vaccination.

Studies have shown that parents are more likely to vaccinate their children if providers recommend the vaccine.11 As women’s health care providers, we do not always see children during the time period that is ideal for vaccination. However, we take care of many women who are presenting for routine gynecologic care, pregnancy, or with abnormal Pap smear screenings. These are ideal opportunities to educate and offer HPV vaccination to women in the approved age groups, as well as to encourage parents to vaccinate their children.

As with other vaccines, the recommendation should be clear and focused on the cancer prevention benefit. Using methods in which the recommendation is “announced” in a brief statement assuming parents/patients are ready to vaccinate versus open-ended conversations, has been studied as a potentially successful method to increase uptake of HPV vaccination.12 Additionally, documentation of HPV vaccination status should be built into electronic medical record templates to prompt clinicians to ask and offer HPV vaccination at visits, including postpartum visits.

Dr. Rahangdale is an associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and is director of the North Carolina Women’s Hospital Cervical Dysplasia Clinic. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Jul 15;168(2):123-37.

2. Int J Cancer. 2012 Nov 1;131(9):1969-82.

3. BMJ. 2012 Mar 27;344:e1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1401.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Jun. doi. org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.031.

5. Int J Prev Med. 2017 Jun 1;8:44. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_413_16.

6. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Aug;130(2):264-8.

7. Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130(5):798-805.

8. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):617-23.

9. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016 Sep;55(10):904-14.

10. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Jul 31;64(29):784-92.

11. Vaccine. 2016 Feb 24;34(9):1187-92.

12. Pediatrics. 2017 Jan;139(1). pii:e20161764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1764.

FDA advisory panel backs safety of new hepatitis B vaccine for adults

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee approved licensure for Heplisav-B, a new two-dose recombinant hepatitis B vaccination, after voting that presented data proved the vaccine to be safe for adults 18 and over.

At an advisory meeting, after hearing testimony from government researchers and representatives of Dynavax Technologies Corporation, the manufacturer of Heplisav-B, 11 members voted to approve the drug, 1 member voted no, and 3 abstained.

There are more than 20,000 new infections each year, with a reported increase of 21% between 2014 and 2015, according to research presented by William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventative medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

There are two approved immunizations for hepatitis B: Engerix-B, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline, and Recombivax HB, by Merck. Both are three-dose, recombinant vaccines produced from yeast cells.

Like the current vaccines, Heplisav-B is a recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen that is derived from yeast; however, this vaccine would be administered in two doses over 1 month, as opposed to three doses over 6 months as is the schedule for currently approved vaccines. Both manufacturing representatives and approving members of the committee stressed this as an important factor due to vaccination dropout rates.

“We have a problem with hepatitis B infections in this country as well as problems with the current vaccines,“ said John Ward, MD, director of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “and they happen in these populations where, in terms of data, both of those audiences have problems about going for the second and third dose.”

Patients that drop out before the third dose are at high risk of infection, as only 20%-50% of adults have the appropriate seroprotection after two doses. However, only 54% of patients in a vaccine safety Datalink study reported completing the vaccination series, with 81% reporting having received two doses, according to Dr. Schaffner.

While the committee did approve the safety research as sufficient to approve use of Heplisav-B in adults 18 years and older, members of the committee had an issue with the drug’s correlation with myocardial infarction.

In one of the studies presented, Heplisav-B’s acute myocardial infarction (AMI) events (14 patients) greatly outnumbered those of Engerix-B (1 patient), presenting an AMI relative risk of 6.97.

Dynavax representatives, in response to this concern, presented intention to conduct a postmarketing analysis of the risk of MI in patients who have been administered Heplisav-B, which committee members considered to be a crucial contingency for approval.

“I would like to say I am for the approval of this vaccine, I just think as a statistician that the safety was inconclusive,” said Mei-Ling Ting Lee, PhD, director of the Biostatistics and Risk Assessment Center at the University of Maryland. “But I think for the pharmacological vigilance plan, I think that it will be good to have specific analysis for the myocardial infarction and other risks.”

Dynavax intends to introduce the vaccine commercially in the United States by the middle of 2018, according to a press release.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee approved licensure for Heplisav-B, a new two-dose recombinant hepatitis B vaccination, after voting that presented data proved the vaccine to be safe for adults 18 and over.

At an advisory meeting, after hearing testimony from government researchers and representatives of Dynavax Technologies Corporation, the manufacturer of Heplisav-B, 11 members voted to approve the drug, 1 member voted no, and 3 abstained.

There are more than 20,000 new infections each year, with a reported increase of 21% between 2014 and 2015, according to research presented by William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventative medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

There are two approved immunizations for hepatitis B: Engerix-B, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline, and Recombivax HB, by Merck. Both are three-dose, recombinant vaccines produced from yeast cells.

Like the current vaccines, Heplisav-B is a recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen that is derived from yeast; however, this vaccine would be administered in two doses over 1 month, as opposed to three doses over 6 months as is the schedule for currently approved vaccines. Both manufacturing representatives and approving members of the committee stressed this as an important factor due to vaccination dropout rates.

“We have a problem with hepatitis B infections in this country as well as problems with the current vaccines,“ said John Ward, MD, director of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “and they happen in these populations where, in terms of data, both of those audiences have problems about going for the second and third dose.”

Patients that drop out before the third dose are at high risk of infection, as only 20%-50% of adults have the appropriate seroprotection after two doses. However, only 54% of patients in a vaccine safety Datalink study reported completing the vaccination series, with 81% reporting having received two doses, according to Dr. Schaffner.

While the committee did approve the safety research as sufficient to approve use of Heplisav-B in adults 18 years and older, members of the committee had an issue with the drug’s correlation with myocardial infarction.

In one of the studies presented, Heplisav-B’s acute myocardial infarction (AMI) events (14 patients) greatly outnumbered those of Engerix-B (1 patient), presenting an AMI relative risk of 6.97.

Dynavax representatives, in response to this concern, presented intention to conduct a postmarketing analysis of the risk of MI in patients who have been administered Heplisav-B, which committee members considered to be a crucial contingency for approval.

“I would like to say I am for the approval of this vaccine, I just think as a statistician that the safety was inconclusive,” said Mei-Ling Ting Lee, PhD, director of the Biostatistics and Risk Assessment Center at the University of Maryland. “But I think for the pharmacological vigilance plan, I think that it will be good to have specific analysis for the myocardial infarction and other risks.”

Dynavax intends to introduce the vaccine commercially in the United States by the middle of 2018, according to a press release.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee approved licensure for Heplisav-B, a new two-dose recombinant hepatitis B vaccination, after voting that presented data proved the vaccine to be safe for adults 18 and over.

At an advisory meeting, after hearing testimony from government researchers and representatives of Dynavax Technologies Corporation, the manufacturer of Heplisav-B, 11 members voted to approve the drug, 1 member voted no, and 3 abstained.

There are more than 20,000 new infections each year, with a reported increase of 21% between 2014 and 2015, according to research presented by William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventative medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

There are two approved immunizations for hepatitis B: Engerix-B, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline, and Recombivax HB, by Merck. Both are three-dose, recombinant vaccines produced from yeast cells.

Like the current vaccines, Heplisav-B is a recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen that is derived from yeast; however, this vaccine would be administered in two doses over 1 month, as opposed to three doses over 6 months as is the schedule for currently approved vaccines. Both manufacturing representatives and approving members of the committee stressed this as an important factor due to vaccination dropout rates.

“We have a problem with hepatitis B infections in this country as well as problems with the current vaccines,“ said John Ward, MD, director of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “and they happen in these populations where, in terms of data, both of those audiences have problems about going for the second and third dose.”

Patients that drop out before the third dose are at high risk of infection, as only 20%-50% of adults have the appropriate seroprotection after two doses. However, only 54% of patients in a vaccine safety Datalink study reported completing the vaccination series, with 81% reporting having received two doses, according to Dr. Schaffner.

While the committee did approve the safety research as sufficient to approve use of Heplisav-B in adults 18 years and older, members of the committee had an issue with the drug’s correlation with myocardial infarction.

In one of the studies presented, Heplisav-B’s acute myocardial infarction (AMI) events (14 patients) greatly outnumbered those of Engerix-B (1 patient), presenting an AMI relative risk of 6.97.

Dynavax representatives, in response to this concern, presented intention to conduct a postmarketing analysis of the risk of MI in patients who have been administered Heplisav-B, which committee members considered to be a crucial contingency for approval.

“I would like to say I am for the approval of this vaccine, I just think as a statistician that the safety was inconclusive,” said Mei-Ling Ting Lee, PhD, director of the Biostatistics and Risk Assessment Center at the University of Maryland. “But I think for the pharmacological vigilance plan, I think that it will be good to have specific analysis for the myocardial infarction and other risks.”

Dynavax intends to introduce the vaccine commercially in the United States by the middle of 2018, according to a press release.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

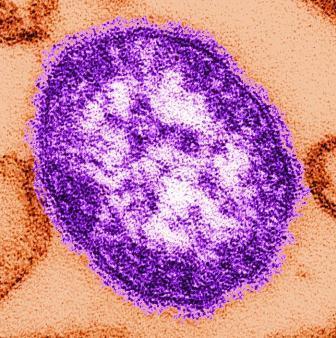

Minor measles vaccination decline could triple childhood cases

, based on data from a mathematical model published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increased reluctance among parents to vaccinate children has led to calls for a government commission on vaccine safety, wrote Nathan C. Lo of Stanford (Calif.) University, and Peter J. Hotez, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Jul 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1695).

The researchers sought to estimate the potential impact of reduced vaccination on public health and the economy, using the MMR vaccine as an example. They collected vaccination data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, created a mathematical model, and estimated $20,000 per case of measles from a public health perspective. They simulated a measles outbreak following the importation of measles into a county in the United States, and estimated the size of an outbreak based on local vaccine coverage.

In the model population, the average baseline coverage for MMR vaccination was 93% prevalence (varying by state from 87% to 97%). The average prevalence of nonmedical exemptions was 2%; state prevalence ranged from 0.4% to 6.2%. The annual number of measles cases was 48.

Using the model, a drop in MMR vaccination as little as 5% “would result in a threefold increase in national measles cases in this age group, for a total of 150 cases and an additional $2.1 million in economic costs to the public sector,” the researchers said. By contrast, increasing national MMR coverage to 95% would reduce the number of cases by 20%, they predicted.

“These estimates would be substantially higher if unvaccinated infants, adolescents, and adult populations are also considered,” Mr. Lo and Dr. Hotez said.

The study findings were limited by the use of a model and simulation of vaccine coverage, and by restricting the study to children aged 2-11 years.

However, the results “directly confront the notion that measles is no longer a threat in the United States,” and suggest “substantial public health and economic consequences with even minor reductions in MMR coverage due to vaccine hesitancy,” they emphasized. “Removal of the nonmedical personal belief exemptions for childhood vaccination may mitigate these consequences.”

Mr. Lo disclosed funding from Stanford’s Medical Scientist Training Program; no financial conflicts were disclosed.

, based on data from a mathematical model published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increased reluctance among parents to vaccinate children has led to calls for a government commission on vaccine safety, wrote Nathan C. Lo of Stanford (Calif.) University, and Peter J. Hotez, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Jul 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1695).

The researchers sought to estimate the potential impact of reduced vaccination on public health and the economy, using the MMR vaccine as an example. They collected vaccination data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, created a mathematical model, and estimated $20,000 per case of measles from a public health perspective. They simulated a measles outbreak following the importation of measles into a county in the United States, and estimated the size of an outbreak based on local vaccine coverage.

In the model population, the average baseline coverage for MMR vaccination was 93% prevalence (varying by state from 87% to 97%). The average prevalence of nonmedical exemptions was 2%; state prevalence ranged from 0.4% to 6.2%. The annual number of measles cases was 48.

Using the model, a drop in MMR vaccination as little as 5% “would result in a threefold increase in national measles cases in this age group, for a total of 150 cases and an additional $2.1 million in economic costs to the public sector,” the researchers said. By contrast, increasing national MMR coverage to 95% would reduce the number of cases by 20%, they predicted.

“These estimates would be substantially higher if unvaccinated infants, adolescents, and adult populations are also considered,” Mr. Lo and Dr. Hotez said.

The study findings were limited by the use of a model and simulation of vaccine coverage, and by restricting the study to children aged 2-11 years.

However, the results “directly confront the notion that measles is no longer a threat in the United States,” and suggest “substantial public health and economic consequences with even minor reductions in MMR coverage due to vaccine hesitancy,” they emphasized. “Removal of the nonmedical personal belief exemptions for childhood vaccination may mitigate these consequences.”

Mr. Lo disclosed funding from Stanford’s Medical Scientist Training Program; no financial conflicts were disclosed.

, based on data from a mathematical model published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increased reluctance among parents to vaccinate children has led to calls for a government commission on vaccine safety, wrote Nathan C. Lo of Stanford (Calif.) University, and Peter J. Hotez, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Jul 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1695).

The researchers sought to estimate the potential impact of reduced vaccination on public health and the economy, using the MMR vaccine as an example. They collected vaccination data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, created a mathematical model, and estimated $20,000 per case of measles from a public health perspective. They simulated a measles outbreak following the importation of measles into a county in the United States, and estimated the size of an outbreak based on local vaccine coverage.

In the model population, the average baseline coverage for MMR vaccination was 93% prevalence (varying by state from 87% to 97%). The average prevalence of nonmedical exemptions was 2%; state prevalence ranged from 0.4% to 6.2%. The annual number of measles cases was 48.

Using the model, a drop in MMR vaccination as little as 5% “would result in a threefold increase in national measles cases in this age group, for a total of 150 cases and an additional $2.1 million in economic costs to the public sector,” the researchers said. By contrast, increasing national MMR coverage to 95% would reduce the number of cases by 20%, they predicted.

“These estimates would be substantially higher if unvaccinated infants, adolescents, and adult populations are also considered,” Mr. Lo and Dr. Hotez said.

The study findings were limited by the use of a model and simulation of vaccine coverage, and by restricting the study to children aged 2-11 years.

However, the results “directly confront the notion that measles is no longer a threat in the United States,” and suggest “substantial public health and economic consequences with even minor reductions in MMR coverage due to vaccine hesitancy,” they emphasized. “Removal of the nonmedical personal belief exemptions for childhood vaccination may mitigate these consequences.”

Mr. Lo disclosed funding from Stanford’s Medical Scientist Training Program; no financial conflicts were disclosed.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Even a small reduction in vaccination rates has significant public health and economic implications.

Major finding: A 5% decline in MMR vaccine coverage among children aged 2-11 years in the United States would yield an additional 150 measles cases at an economic cost of $2.1 million.

Data source: The data come from an analysis of children aged 2-11 years based on a mathematical model of MMR vaccination.

Disclosures: Mr. Lo disclosed funding from Stanford’s Medical Scientist Training Program; no financial conflicts were disclosed.

Maternal protection against measles steadily declines prior to vaccination

, and for coxsackievirus (CoxA16), for which there currently is no vaccine.

EV71 and CoxA16 are enteroviruses that are common agents of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Some patients infected with EV71 or CoxA16 develop neurological and systemic complications that can kill them. An EV71 vaccine, which is initially administered at 6 months, has been licensed in China since December 2015.

In a longitudinally designed study conducted by Chuanxi Fu and Jichuan Shen of Guangzhou (China) Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and their associates, sera was collected from 717 infants ages 0, 3, and 6 months, and examined for levels of measles IgG antibodies, and neutralizing antibodies for EV71 and CoxA16. Measles IgG antibody concentration from 717, 233, and 75 sera were assessed in infants of 0 month, 3 months, and 6 months, and 225, 217, and 72 sera were assessed for EV71 and CoxA16 at these time periods.

This study provides evidence of the rapid declining of measles antibodies in infants prior to vaccination under the Expanded Program on Immunization schedule in China, and confirms the rapid decrease of measles antibody levels suggested by prior cross-sectional studies in China. “Further modifications of vaccination strategies for measles, earlier vaccination for EV71 infection, and development and provision of a CoxA16 vaccine should be investigated and considered in the future,” concluded the researchers.

, and for coxsackievirus (CoxA16), for which there currently is no vaccine.

EV71 and CoxA16 are enteroviruses that are common agents of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Some patients infected with EV71 or CoxA16 develop neurological and systemic complications that can kill them. An EV71 vaccine, which is initially administered at 6 months, has been licensed in China since December 2015.

In a longitudinally designed study conducted by Chuanxi Fu and Jichuan Shen of Guangzhou (China) Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and their associates, sera was collected from 717 infants ages 0, 3, and 6 months, and examined for levels of measles IgG antibodies, and neutralizing antibodies for EV71 and CoxA16. Measles IgG antibody concentration from 717, 233, and 75 sera were assessed in infants of 0 month, 3 months, and 6 months, and 225, 217, and 72 sera were assessed for EV71 and CoxA16 at these time periods.

This study provides evidence of the rapid declining of measles antibodies in infants prior to vaccination under the Expanded Program on Immunization schedule in China, and confirms the rapid decrease of measles antibody levels suggested by prior cross-sectional studies in China. “Further modifications of vaccination strategies for measles, earlier vaccination for EV71 infection, and development and provision of a CoxA16 vaccine should be investigated and considered in the future,” concluded the researchers.

, and for coxsackievirus (CoxA16), for which there currently is no vaccine.

EV71 and CoxA16 are enteroviruses that are common agents of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Some patients infected with EV71 or CoxA16 develop neurological and systemic complications that can kill them. An EV71 vaccine, which is initially administered at 6 months, has been licensed in China since December 2015.

In a longitudinally designed study conducted by Chuanxi Fu and Jichuan Shen of Guangzhou (China) Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and their associates, sera was collected from 717 infants ages 0, 3, and 6 months, and examined for levels of measles IgG antibodies, and neutralizing antibodies for EV71 and CoxA16. Measles IgG antibody concentration from 717, 233, and 75 sera were assessed in infants of 0 month, 3 months, and 6 months, and 225, 217, and 72 sera were assessed for EV71 and CoxA16 at these time periods.

This study provides evidence of the rapid declining of measles antibodies in infants prior to vaccination under the Expanded Program on Immunization schedule in China, and confirms the rapid decrease of measles antibody levels suggested by prior cross-sectional studies in China. “Further modifications of vaccination strategies for measles, earlier vaccination for EV71 infection, and development and provision of a CoxA16 vaccine should be investigated and considered in the future,” concluded the researchers.

FROM VACCINE

Vaccine reduced risk for flu visits by 42%

Last year’s influenza vaccination reduced the overall risk for flu-related medical visits by 42%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In an article summarizing influenza activity in the United States during October 2016–May 2017, investigators said that most of the viral strains antigenically characterized at the CDC “were similar to the reference viruses representing the recommended components for the 2016-2017 vaccine.”

The 2017-2018 influenza vaccine has been updated to include an additional influenza A (H1N1) component. This change was recommended by the Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, based on data from global influenza virologic and epidemiologic surveillance, genetic and antigenic characterization, human serology studies, antiviral susceptibility, and the availability of candidate influenza viruses (MMWR. 2017;66[25]:668-76).

Preliminary data show that, during the 2016-2017 flu season, there were 18,184 laboratory-confirmed, flu-related hospitalizations, for an overall incidence of 65 per 100,000 population, more than double that for the 2015-2017 season (31/100,000). Broken down by age groups, the rates per 100,000 population in this past season were 44 at ages 0-4 years, 17 at ages 5-17 years, 20 at ages 18-49 years, and 65 at ages 50-64 years, compared with 291 at ages 65 years and older. Finalized estimates of the number of influenza illnesses, medical visits, and hospitalizations averted by vaccination during the 2016-2017 season will be published in December, the investigators said.

Last year’s influenza vaccination reduced the overall risk for flu-related medical visits by 42%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In an article summarizing influenza activity in the United States during October 2016–May 2017, investigators said that most of the viral strains antigenically characterized at the CDC “were similar to the reference viruses representing the recommended components for the 2016-2017 vaccine.”

The 2017-2018 influenza vaccine has been updated to include an additional influenza A (H1N1) component. This change was recommended by the Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, based on data from global influenza virologic and epidemiologic surveillance, genetic and antigenic characterization, human serology studies, antiviral susceptibility, and the availability of candidate influenza viruses (MMWR. 2017;66[25]:668-76).

Preliminary data show that, during the 2016-2017 flu season, there were 18,184 laboratory-confirmed, flu-related hospitalizations, for an overall incidence of 65 per 100,000 population, more than double that for the 2015-2017 season (31/100,000). Broken down by age groups, the rates per 100,000 population in this past season were 44 at ages 0-4 years, 17 at ages 5-17 years, 20 at ages 18-49 years, and 65 at ages 50-64 years, compared with 291 at ages 65 years and older. Finalized estimates of the number of influenza illnesses, medical visits, and hospitalizations averted by vaccination during the 2016-2017 season will be published in December, the investigators said.

Last year’s influenza vaccination reduced the overall risk for flu-related medical visits by 42%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In an article summarizing influenza activity in the United States during October 2016–May 2017, investigators said that most of the viral strains antigenically characterized at the CDC “were similar to the reference viruses representing the recommended components for the 2016-2017 vaccine.”

The 2017-2018 influenza vaccine has been updated to include an additional influenza A (H1N1) component. This change was recommended by the Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, based on data from global influenza virologic and epidemiologic surveillance, genetic and antigenic characterization, human serology studies, antiviral susceptibility, and the availability of candidate influenza viruses (MMWR. 2017;66[25]:668-76).

Preliminary data show that, during the 2016-2017 flu season, there were 18,184 laboratory-confirmed, flu-related hospitalizations, for an overall incidence of 65 per 100,000 population, more than double that for the 2015-2017 season (31/100,000). Broken down by age groups, the rates per 100,000 population in this past season were 44 at ages 0-4 years, 17 at ages 5-17 years, 20 at ages 18-49 years, and 65 at ages 50-64 years, compared with 291 at ages 65 years and older. Finalized estimates of the number of influenza illnesses, medical visits, and hospitalizations averted by vaccination during the 2016-2017 season will be published in December, the investigators said.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Key clinical point: Last year’s influenza vaccination reduced the overall risk for flu-related medical visits by 42%.

Major finding: During the 2016-2017 flu season, there were 18,184 laboratory-confirmed, flu-related hospitalizations, for an overall incidence of 65 per 100,000 population.

Data source: A review of data submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention regarding the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the CDC. Dr. Blanton and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Children with HIV benefit from double dose of PCV13 vaccine

, while children with kidney or lung disease may need only one dose, reported Sabelle Jallow, PhD, of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, and associates.

An open-label study was conducted at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH) in Soweto, South Africa, to determine the immunogenicity of one and two doses of PCV13 in vaccine-naive children with HIV infection, kidney disease, or lung disease. Of the 112 children in the study, there were 50 HIV-infected children, 8 children with kidney disease, 9 with lung disease, and 45 HIV-uninfected control children with no chronic illness. The average age at enrollment was 62 months, 53% of participants were female, and 96% were of black African descent. At-risk children were given two doses of PCV13, 2 months apart, while control children received only one PCV13 dose (Vaccine. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.081).

“In future studies, a larger spectrum of comorbidities should be included to determine the most cost-effective vaccination regimens particularly in low income countries,” the researchers noted.

, while children with kidney or lung disease may need only one dose, reported Sabelle Jallow, PhD, of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, and associates.

An open-label study was conducted at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH) in Soweto, South Africa, to determine the immunogenicity of one and two doses of PCV13 in vaccine-naive children with HIV infection, kidney disease, or lung disease. Of the 112 children in the study, there were 50 HIV-infected children, 8 children with kidney disease, 9 with lung disease, and 45 HIV-uninfected control children with no chronic illness. The average age at enrollment was 62 months, 53% of participants were female, and 96% were of black African descent. At-risk children were given two doses of PCV13, 2 months apart, while control children received only one PCV13 dose (Vaccine. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.081).

“In future studies, a larger spectrum of comorbidities should be included to determine the most cost-effective vaccination regimens particularly in low income countries,” the researchers noted.

, while children with kidney or lung disease may need only one dose, reported Sabelle Jallow, PhD, of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, and associates.

An open-label study was conducted at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH) in Soweto, South Africa, to determine the immunogenicity of one and two doses of PCV13 in vaccine-naive children with HIV infection, kidney disease, or lung disease. Of the 112 children in the study, there were 50 HIV-infected children, 8 children with kidney disease, 9 with lung disease, and 45 HIV-uninfected control children with no chronic illness. The average age at enrollment was 62 months, 53% of participants were female, and 96% were of black African descent. At-risk children were given two doses of PCV13, 2 months apart, while control children received only one PCV13 dose (Vaccine. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.081).

“In future studies, a larger spectrum of comorbidities should be included to determine the most cost-effective vaccination regimens particularly in low income countries,” the researchers noted.

FROM VACCINE

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines modestly reduce complex acute otitis media

Incidence rate ratios of children hospitalized with acute otitis media (hAOM) or more advanced stages, such as mastoidismus and acute mastoiditis (M+AM) declined by 10% and 20%, respectively, after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in the central region of Denmark, reported Bjarke B. Laursen of Aarhus University in Denmark, and associates.

The use of antibiotics for AOM prior to hospitalization increased markedly during the study period, and that may have impacted the modest reduction in hAOM and M+AM, the researchers said.

Incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae cases decreased from 38% in the prevaccine era to 31% in the PCV-7 era and decreased even more to 16% in the PCV-13 era. The incidence of the second most frequently isolated bacteria, group A streptococcus (GAS), fell from 17% in the prevaccine era to 16% in the PCV-13 era, becoming equal to S. pneumoniae. The “no growth” results rose from 12% in the prevaccine era to 38% and 44% in the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, respectively (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.002) .

In the M+AM group, S. pneumoniae–positive cases fell to 10% in the PCV-13 era, compared with 44% in the prevaccine era and 41% in the PCV-7 era. A rise in GAS-positive cultures was seen in the M+AM group, from 15% in the prevaccine era to 30% in the PCV-13 era. The “no growth” group rose in incidence from 13% of cases in the prevaccine era to 26% in the PCV-7 era and 33% in the PCV-13 era.

“This microbiological shift is worrisome, because GAS may cause very serious infections due to its invasive nature,” Dr. Laursen and associates wrote. “An increase in GAS as described in this study has not been demonstrated elsewhere so far. In contrast to our findings, the most common species to ‘take over’ in the United States was Haemophilus influenzae.

“As [S. pneumoniae] and GAS are potentially invasive pathogens causing more severe clinical signs and symptoms, such cases are more likely to be admitted compared to cases caused by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae that gives rise to more subtle middle ear infections and clinical pictures,” the researchers noted.

Considering how many patients received antibiotics prior to admission in the hAOM group, there was a slight increase from 45% in the prevaccine era to 54% in the PCV-13 era, but a “more pronounced increase was found in the M+AM group, from 27% in the prevaccine era to 46% in the PCV-13 era,” they said.

The investigators called for continued surveillance of the microbiology associated with complex AOM.

No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.

Incidence rate ratios of children hospitalized with acute otitis media (hAOM) or more advanced stages, such as mastoidismus and acute mastoiditis (M+AM) declined by 10% and 20%, respectively, after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in the central region of Denmark, reported Bjarke B. Laursen of Aarhus University in Denmark, and associates.

The use of antibiotics for AOM prior to hospitalization increased markedly during the study period, and that may have impacted the modest reduction in hAOM and M+AM, the researchers said.

Incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae cases decreased from 38% in the prevaccine era to 31% in the PCV-7 era and decreased even more to 16% in the PCV-13 era. The incidence of the second most frequently isolated bacteria, group A streptococcus (GAS), fell from 17% in the prevaccine era to 16% in the PCV-13 era, becoming equal to S. pneumoniae. The “no growth” results rose from 12% in the prevaccine era to 38% and 44% in the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, respectively (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.002) .

In the M+AM group, S. pneumoniae–positive cases fell to 10% in the PCV-13 era, compared with 44% in the prevaccine era and 41% in the PCV-7 era. A rise in GAS-positive cultures was seen in the M+AM group, from 15% in the prevaccine era to 30% in the PCV-13 era. The “no growth” group rose in incidence from 13% of cases in the prevaccine era to 26% in the PCV-7 era and 33% in the PCV-13 era.

“This microbiological shift is worrisome, because GAS may cause very serious infections due to its invasive nature,” Dr. Laursen and associates wrote. “An increase in GAS as described in this study has not been demonstrated elsewhere so far. In contrast to our findings, the most common species to ‘take over’ in the United States was Haemophilus influenzae.

“As [S. pneumoniae] and GAS are potentially invasive pathogens causing more severe clinical signs and symptoms, such cases are more likely to be admitted compared to cases caused by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae that gives rise to more subtle middle ear infections and clinical pictures,” the researchers noted.

Considering how many patients received antibiotics prior to admission in the hAOM group, there was a slight increase from 45% in the prevaccine era to 54% in the PCV-13 era, but a “more pronounced increase was found in the M+AM group, from 27% in the prevaccine era to 46% in the PCV-13 era,” they said.

The investigators called for continued surveillance of the microbiology associated with complex AOM.

No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.

Incidence rate ratios of children hospitalized with acute otitis media (hAOM) or more advanced stages, such as mastoidismus and acute mastoiditis (M+AM) declined by 10% and 20%, respectively, after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in the central region of Denmark, reported Bjarke B. Laursen of Aarhus University in Denmark, and associates.

The use of antibiotics for AOM prior to hospitalization increased markedly during the study period, and that may have impacted the modest reduction in hAOM and M+AM, the researchers said.

Incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae cases decreased from 38% in the prevaccine era to 31% in the PCV-7 era and decreased even more to 16% in the PCV-13 era. The incidence of the second most frequently isolated bacteria, group A streptococcus (GAS), fell from 17% in the prevaccine era to 16% in the PCV-13 era, becoming equal to S. pneumoniae. The “no growth” results rose from 12% in the prevaccine era to 38% and 44% in the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, respectively (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.002) .

In the M+AM group, S. pneumoniae–positive cases fell to 10% in the PCV-13 era, compared with 44% in the prevaccine era and 41% in the PCV-7 era. A rise in GAS-positive cultures was seen in the M+AM group, from 15% in the prevaccine era to 30% in the PCV-13 era. The “no growth” group rose in incidence from 13% of cases in the prevaccine era to 26% in the PCV-7 era and 33% in the PCV-13 era.

“This microbiological shift is worrisome, because GAS may cause very serious infections due to its invasive nature,” Dr. Laursen and associates wrote. “An increase in GAS as described in this study has not been demonstrated elsewhere so far. In contrast to our findings, the most common species to ‘take over’ in the United States was Haemophilus influenzae.

“As [S. pneumoniae] and GAS are potentially invasive pathogens causing more severe clinical signs and symptoms, such cases are more likely to be admitted compared to cases caused by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae that gives rise to more subtle middle ear infections and clinical pictures,” the researchers noted.

Considering how many patients received antibiotics prior to admission in the hAOM group, there was a slight increase from 45% in the prevaccine era to 54% in the PCV-13 era, but a “more pronounced increase was found in the M+AM group, from 27% in the prevaccine era to 46% in the PCV-13 era,” they said.

The investigators called for continued surveillance of the microbiology associated with complex AOM.

No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall incidence in hAOM decreased numerically from 6.45/100,000 annually in the prevaccine era to 2.43/100,000 in the PCV-7 era, and to 5.88/100,000 annually in the PCV-13 era.

Data source: A retrospective study of 246 cases of children hospitalized with acute otitis media.

Disclosures: No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.

Hexavalent hepatitis B vaccination mostly immunogenic 10 years later

results of an Italian study show.

The phase 3 open-label, controlled study included 732 healthy Italian children aged 11-13 years who as infants had received a two-dose primary and booster course with either Hexavac (5 mcg hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg]) or Infanrix hexa (10 mcg HBsAg) at 3, 5, and 11 months of age; the last dose was received at least 10 years prior to the challenge dose of a monovalent HB vaccine (HBVaxPro, 5 mcg HBsAg).

Although some of the children had HB surface antigen antibody concentrations below the seroprotection threshold, most of them had an anamnestic response when challenged with the dose of HB vaccine, “indicating the presence of specific immune memory,” the investigators said. There was no evidence of active HB disease in any of the children.

Just what the meaning of the lack of immune memory is, defined as the failure to develop an anamnestic response following an HB vaccine challenge, remains to be determined.

results of an Italian study show.

The phase 3 open-label, controlled study included 732 healthy Italian children aged 11-13 years who as infants had received a two-dose primary and booster course with either Hexavac (5 mcg hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg]) or Infanrix hexa (10 mcg HBsAg) at 3, 5, and 11 months of age; the last dose was received at least 10 years prior to the challenge dose of a monovalent HB vaccine (HBVaxPro, 5 mcg HBsAg).

Although some of the children had HB surface antigen antibody concentrations below the seroprotection threshold, most of them had an anamnestic response when challenged with the dose of HB vaccine, “indicating the presence of specific immune memory,” the investigators said. There was no evidence of active HB disease in any of the children.

Just what the meaning of the lack of immune memory is, defined as the failure to develop an anamnestic response following an HB vaccine challenge, remains to be determined.

results of an Italian study show.

The phase 3 open-label, controlled study included 732 healthy Italian children aged 11-13 years who as infants had received a two-dose primary and booster course with either Hexavac (5 mcg hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg]) or Infanrix hexa (10 mcg HBsAg) at 3, 5, and 11 months of age; the last dose was received at least 10 years prior to the challenge dose of a monovalent HB vaccine (HBVaxPro, 5 mcg HBsAg).

Although some of the children had HB surface antigen antibody concentrations below the seroprotection threshold, most of them had an anamnestic response when challenged with the dose of HB vaccine, “indicating the presence of specific immune memory,” the investigators said. There was no evidence of active HB disease in any of the children.

Just what the meaning of the lack of immune memory is, defined as the failure to develop an anamnestic response following an HB vaccine challenge, remains to be determined.

FROM VACCINE