User login

PTSD, depression combo tied to high risk for early death in women

Middle-aged women with PTSD and comorbid depression have a nearly fourfold increased risk for early death from a variety of causes in comparison with their peers who do not have those conditions, new research shows.

“Women with more severe symptoms of depression and PTSD were more at risk, compared with those with fewer symptoms or women with symptoms of only PTSD or only depression,” lead investigator Andrea Roberts, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

Health care providers “should be aware that mental health is a critical component of overall health and is tightly entwined with physical health. Identifying and treating mental health issues should be a foundational part of general health practice,” said Dr. Roberts.

The study was published online Dec. 4 in JAMA Network Open.

Mental health fundamental to survival

The researchers studied more than 51,000 mostly White women from the Nurses Health Study II who were followed for 9 years (2008-2017). At baseline in 2008, the women were aged between 43 and 64 years (mean age, 53.3 years).

Women with high levels of PTSD (six or seven symptoms) and probable depression were nearly four times more likely to die during follow-up than their peers who did not have these conditions (hazard ratio, 3.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.65-5.45; P < .001).

With adjustment for health factors such as smoking and body mass index, women with a high level of PTSD and depression remained at increased risk for early death (HR, 3.11; 95% CI, 2.16-4.47; P < .001).

The risk for early death was also elevated among women with moderate PTSD (four or five symptoms) and depression (HR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.35-3.03; P < .001) and women with subclinical PTSD and depression (HR, 2.85; 95% CI, 1.99-4.07; P < .001) compared with those who did not have PTSD or depression.

Among women with PTSD symptoms and depression, the incidence of death from nearly all major causes was increased, including death from cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, type 2 diabetes, unintentional injury, suicide, and other causes.

“These findings provide further evidence that mental health is fundamental to physical health – and to our very survival. We ignore our emotional well-being at our peril,” senior author Karestan Koenen, PhD, said in a news release.

New knowledge

Commenting on the findings, Jennifer Sumner, PhD, said that it’s “critical to appreciate the physical health consequences of psychopathology in individuals who have experienced trauma. This study adds to a growing literature demonstrating that the impact extends far beyond emotional health.

“Furthermore, these results highlight the potential value of promoting healthy lifestyle changes in order to reduce the elevated mortality risk in trauma-exposed individuals with co-occurring PTSD and depression,” said Dr. Sumner, who is with the department of psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.

She noted that this study builds on other work that links PTSD to mortality in men.

“Most work on posttraumatic psychopathology and physical health has actually been conducted in predominantly male samples of veterans, so said Dr. Sumner.

“It’s also important to note that PTSD and depression are more prevalent in women than in men, so demonstrating these associations in women is particularly relevant,” she added.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Heath. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sumner has collaborated with the study investigators on prior studies.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Middle-aged women with PTSD and comorbid depression have a nearly fourfold increased risk for early death from a variety of causes in comparison with their peers who do not have those conditions, new research shows.

“Women with more severe symptoms of depression and PTSD were more at risk, compared with those with fewer symptoms or women with symptoms of only PTSD or only depression,” lead investigator Andrea Roberts, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

Health care providers “should be aware that mental health is a critical component of overall health and is tightly entwined with physical health. Identifying and treating mental health issues should be a foundational part of general health practice,” said Dr. Roberts.

The study was published online Dec. 4 in JAMA Network Open.

Mental health fundamental to survival

The researchers studied more than 51,000 mostly White women from the Nurses Health Study II who were followed for 9 years (2008-2017). At baseline in 2008, the women were aged between 43 and 64 years (mean age, 53.3 years).

Women with high levels of PTSD (six or seven symptoms) and probable depression were nearly four times more likely to die during follow-up than their peers who did not have these conditions (hazard ratio, 3.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.65-5.45; P < .001).

With adjustment for health factors such as smoking and body mass index, women with a high level of PTSD and depression remained at increased risk for early death (HR, 3.11; 95% CI, 2.16-4.47; P < .001).

The risk for early death was also elevated among women with moderate PTSD (four or five symptoms) and depression (HR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.35-3.03; P < .001) and women with subclinical PTSD and depression (HR, 2.85; 95% CI, 1.99-4.07; P < .001) compared with those who did not have PTSD or depression.

Among women with PTSD symptoms and depression, the incidence of death from nearly all major causes was increased, including death from cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, type 2 diabetes, unintentional injury, suicide, and other causes.

“These findings provide further evidence that mental health is fundamental to physical health – and to our very survival. We ignore our emotional well-being at our peril,” senior author Karestan Koenen, PhD, said in a news release.

New knowledge

Commenting on the findings, Jennifer Sumner, PhD, said that it’s “critical to appreciate the physical health consequences of psychopathology in individuals who have experienced trauma. This study adds to a growing literature demonstrating that the impact extends far beyond emotional health.

“Furthermore, these results highlight the potential value of promoting healthy lifestyle changes in order to reduce the elevated mortality risk in trauma-exposed individuals with co-occurring PTSD and depression,” said Dr. Sumner, who is with the department of psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.

She noted that this study builds on other work that links PTSD to mortality in men.

“Most work on posttraumatic psychopathology and physical health has actually been conducted in predominantly male samples of veterans, so said Dr. Sumner.

“It’s also important to note that PTSD and depression are more prevalent in women than in men, so demonstrating these associations in women is particularly relevant,” she added.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Heath. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sumner has collaborated with the study investigators on prior studies.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Middle-aged women with PTSD and comorbid depression have a nearly fourfold increased risk for early death from a variety of causes in comparison with their peers who do not have those conditions, new research shows.

“Women with more severe symptoms of depression and PTSD were more at risk, compared with those with fewer symptoms or women with symptoms of only PTSD or only depression,” lead investigator Andrea Roberts, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

Health care providers “should be aware that mental health is a critical component of overall health and is tightly entwined with physical health. Identifying and treating mental health issues should be a foundational part of general health practice,” said Dr. Roberts.

The study was published online Dec. 4 in JAMA Network Open.

Mental health fundamental to survival

The researchers studied more than 51,000 mostly White women from the Nurses Health Study II who were followed for 9 years (2008-2017). At baseline in 2008, the women were aged between 43 and 64 years (mean age, 53.3 years).

Women with high levels of PTSD (six or seven symptoms) and probable depression were nearly four times more likely to die during follow-up than their peers who did not have these conditions (hazard ratio, 3.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.65-5.45; P < .001).

With adjustment for health factors such as smoking and body mass index, women with a high level of PTSD and depression remained at increased risk for early death (HR, 3.11; 95% CI, 2.16-4.47; P < .001).

The risk for early death was also elevated among women with moderate PTSD (four or five symptoms) and depression (HR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.35-3.03; P < .001) and women with subclinical PTSD and depression (HR, 2.85; 95% CI, 1.99-4.07; P < .001) compared with those who did not have PTSD or depression.

Among women with PTSD symptoms and depression, the incidence of death from nearly all major causes was increased, including death from cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, type 2 diabetes, unintentional injury, suicide, and other causes.

“These findings provide further evidence that mental health is fundamental to physical health – and to our very survival. We ignore our emotional well-being at our peril,” senior author Karestan Koenen, PhD, said in a news release.

New knowledge

Commenting on the findings, Jennifer Sumner, PhD, said that it’s “critical to appreciate the physical health consequences of psychopathology in individuals who have experienced trauma. This study adds to a growing literature demonstrating that the impact extends far beyond emotional health.

“Furthermore, these results highlight the potential value of promoting healthy lifestyle changes in order to reduce the elevated mortality risk in trauma-exposed individuals with co-occurring PTSD and depression,” said Dr. Sumner, who is with the department of psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.

She noted that this study builds on other work that links PTSD to mortality in men.

“Most work on posttraumatic psychopathology and physical health has actually been conducted in predominantly male samples of veterans, so said Dr. Sumner.

“It’s also important to note that PTSD and depression are more prevalent in women than in men, so demonstrating these associations in women is particularly relevant,” she added.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Heath. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sumner has collaborated with the study investigators on prior studies.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

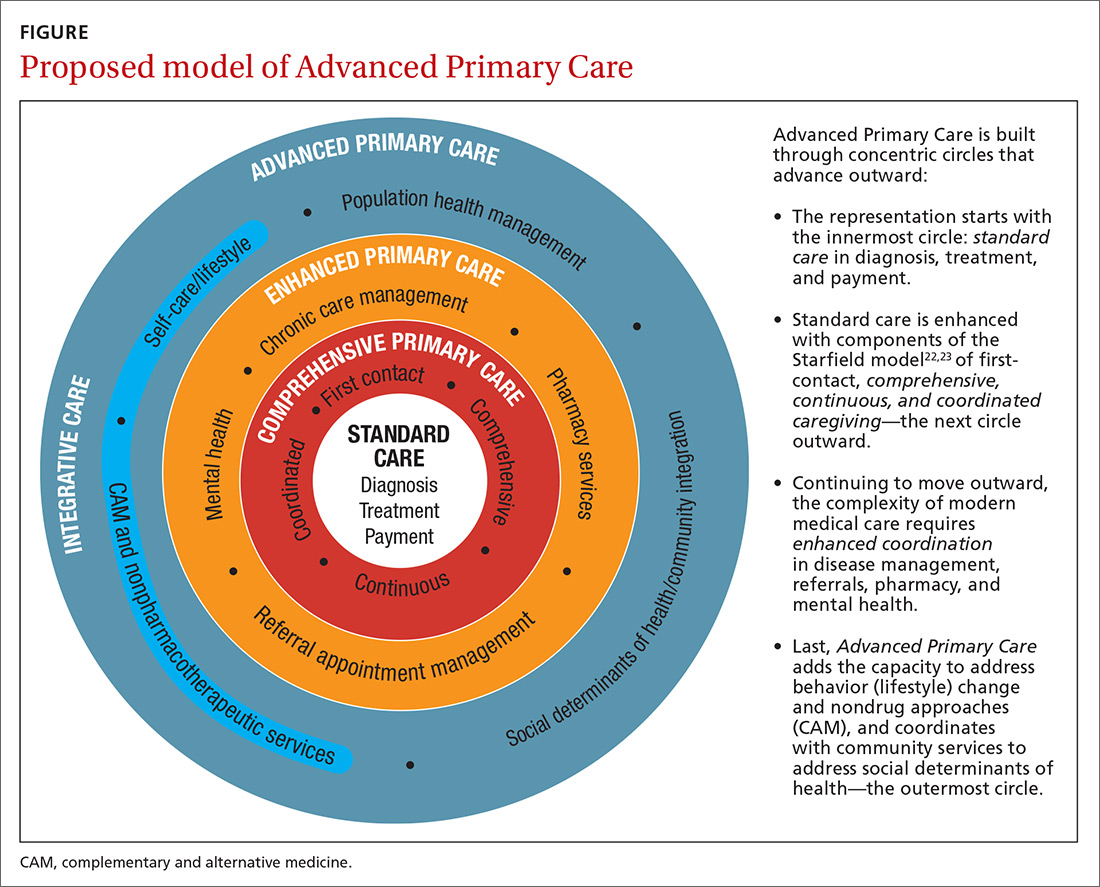

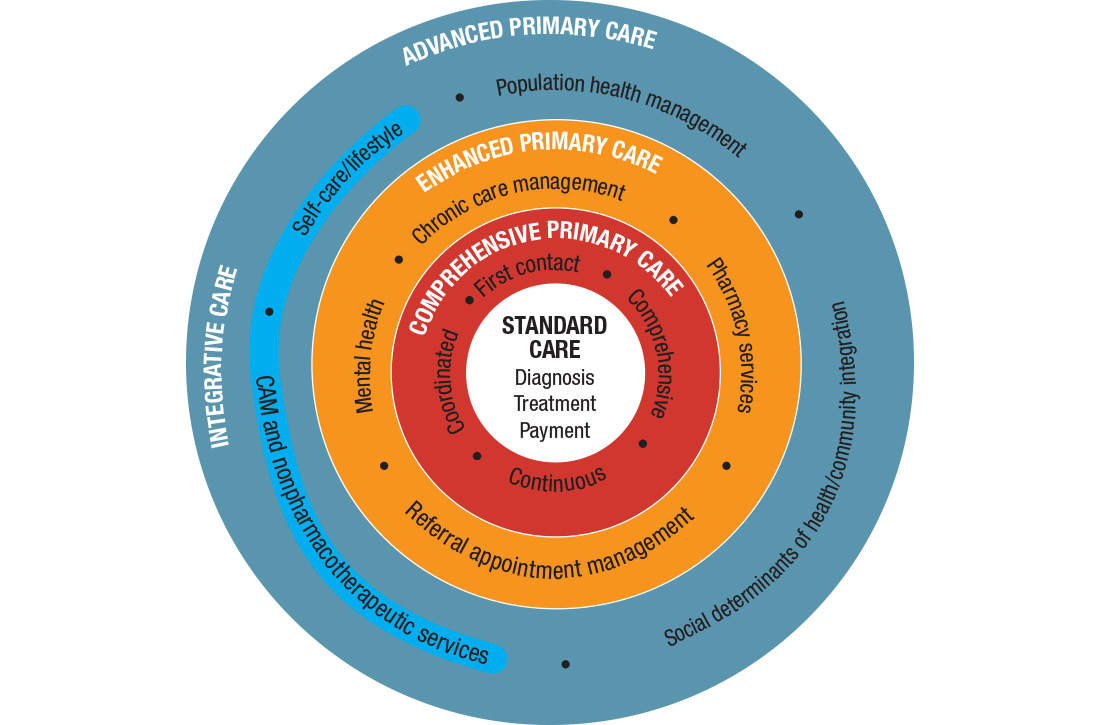

At-home exercises for 4 common musculoskeletal complaints

The mainstay of treatment for many musculoskeletal (MSK) complaints is physical or occupational therapy. But often an individual’s underlying biomechanical issue is one that can be easily addressed with a home exercise plan, and, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients may wish to avoid in-person physical therapy. This article describes the rationale for, and methods of providing, home exercises for several MSK conditions commonly seen in the primary care setting.

General rehabilitation principles: First things first

With basic MSK complaints, focus on controlling pain and swelling before undertaking restoration of function. Tailor pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options to the patient’s needs, using first-line modalities such as ice and compression to reduce inflammation, and prescribing scheduled doses of an anti-inflammatory medication to help with both pain and inflammation.

Once pain is sufficiently controlled, have patients begin basic rehabilitation with simple range-of-motion exercises that move the injured region through normal patterns, as tolerated. Later, the patient can progress through more specific exercises to return the injured region to full functional capacity.

Explain to patients that it takes about 7 to 10 days of consistent care to decrease inflammation, but that they should begin prescribed exercises once they are able to tolerate them. Plan a follow-up visit in 2 to 3 weeks to check on the patient’s response to prescribed care.

Which is better, ice or heat?

Ice and heat are both commonly used to treat MSK injuries and pain, although scrutiny of the use of either intervention has increased. Despite the widespread use of these modalities, there is little evidence to support their effect on patient outcomes. The historical consensus has been that ice decreases pain, inflammation, and edema,while heat can facilitate movement in rehabilitation by improving blood flow and decreasing stiffness.1-3 In our practice, we encourage use of both topical modalities as a way to start exercise therapy when pain from the acute injury limits participation. Patients often ask which modality they should use. Ice is generally applied in the acute injury phase (48-72 hours after injury), while heat has been thought to be more beneficial in the chronic stages.

Ccontinue to: When and how to apply ice

When and how to apply ice. Applying an ice pack or a bag of frozen vegetables directly to the affected area will help control pain and swelling. Ice should be applied for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, once an hour. If a patient has sensitivity to cold or if the ice pack is a gel-type, have the patient place a layer (eg, towel) between the ice and skin to avoid injury to the skin. Additional caution should be exercised in patients with peripheral vascular disease, cryoglobulinemia, Raynaud disease, or a history of frostbite at the site.4

An alternative method we sometimes recommend is ice-cup massage. The patient can fill a small paper cup with water and freeze it. The cup is then used to massage the injured area, providing a more active method of icing whereby the cold can penetrate more quickly. Ice-cup massage should be done for 5 to 10 minutes, 3 to 4 times a day.

When and how to apply heat. Heat will help relax and loosen muscles and is a preferred treatment for older injuries, chronic pain, muscle tension, and spasms.5 Because heat can increase blood flow and, likely, inflammation, it should not be used in the acute injury phase. A heating pad or a warm, wet towel can be applied for up to 20 minutes at a time to help relieve pain and tension. Heat is also beneficial before participating in rehab activities as a method of “warming up” a recently injured area.6 However, ice should still be used following activity to prevent any new inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory medications

For an acute injury, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) not only can decrease inflammation and aid in healing but can alleviate pain. We typically start with over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs taken on a schedule. A good suggestion is to have the patient take the scheduled NSAID with food for 7 to 10 days or until symptoms subside.

Topical analgesics

Because oral medications can occasionally cause adverse effects or be contraindicated in some patients, topical analgesics can be a good substitute due to their minimal adverse effects. Acceptable topical medications include NSAIDs, lidocaine, menthol, and arnica. Other than prescribed topical NSAIDs, these products can be applied directly to the painful area on an as-needed basis. Often, a topical patch is a nice option to recommend for use during work or school, and a topical cream or ointment can be used at bedtime.

Continue to: Graduated rehabilitation

Graduated rehabilitation

The following 4 common MSK injuries are ones that can benefit from a graduated approach to rehabilitation at home.

Lateral ankle sprain

Lateral ankle sprain, usually resulting from an inversion mechanism, is the most common type of acute ankle sprain seen in primary care and sports medicine settings.7-9 The injury causes lateral ankle pain and swelling, decreased range of motion and strength, and pain with weight-bearing activities.

Treatment and rehabilitation after this type of injury are critical to restoring normal function and increasing the likelihood of returning to pre-injury levels of activity.9,10 Goals for an acute ankle sprain include controlling swelling, regaining full range of motion, increasing muscle strength and power, and improving balance.

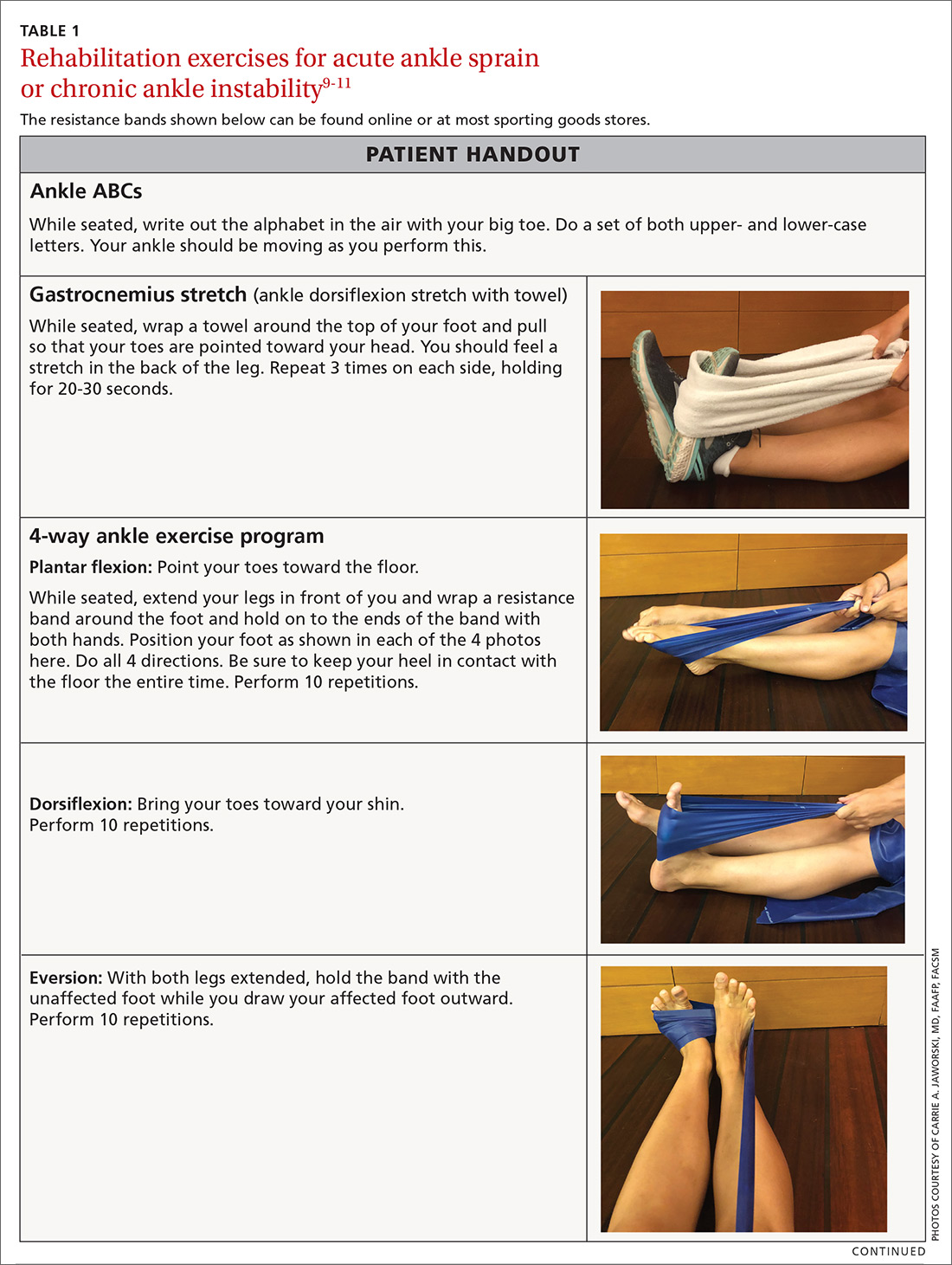

Phase 1: Immediately following injury, have the patient protect the injured area with rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). This will help to decrease swelling and pain. Exercises to regain range of motion, such as stretching and doing ankle “ABCs,” should begin within 48 to 72 hours of the initial injury (TABLE 1).9-11

Continue to: Phase 2

Phase 2: Once the patient has achieved full range of motion and pain is controlled, begin the process of regaining strength. The 4-way ankle exercise program (with elastic tubing) is an easy at-home exercise that has been shown to improve strength in plantar flexion, dorsiflexion, eversion, and inversion (TABLE 1).9-11

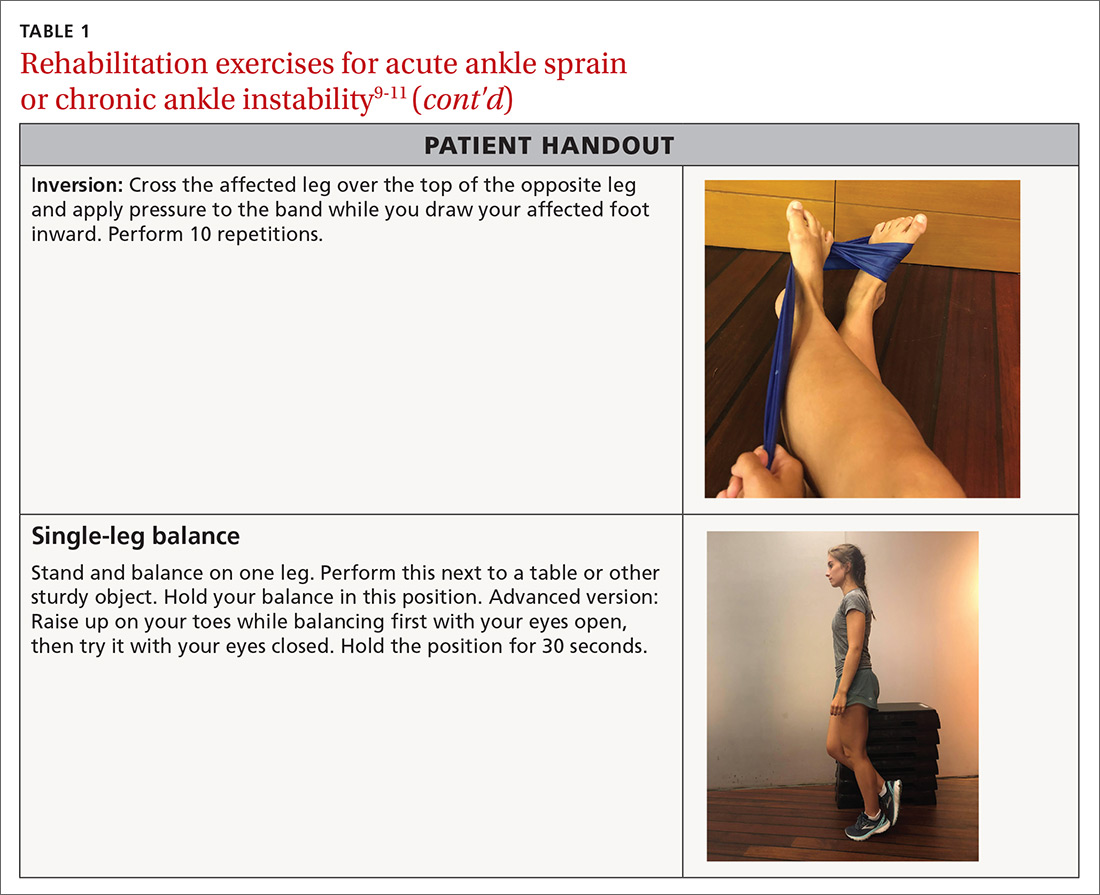

Phase 3: Once your patient is able to bear full weight with little to no pain, begin a balance program (TABLE 19-11). This is the most frequently neglected component of rehabilitation and the most common reason patients return with chronic ankle pain or repeat ankle injuries. Deficits in postural stability and balance have been reported in unstable ankles following acute ankle sprains,10,12-15 and studies have shown that individuals with poor stability are at a greater risk of injury.13-16

For most lateral ankle sprains, patients can expect time to recovery to range from 2 to 8 weeks. Longer recoveries are associated with more severe injuries or those that involve the syndesmosis.

Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis (PF) of the foot can be frustrating for a patient due to its chronic nature. Most patients will present with pain in the heel that is aggravated by weight-bearing activities. A conservative management program that focuses on reducing pain and inflammation, reducing tissue stress, and restoring strength and flexibility has been shown to be effective for this type of injury.17,18

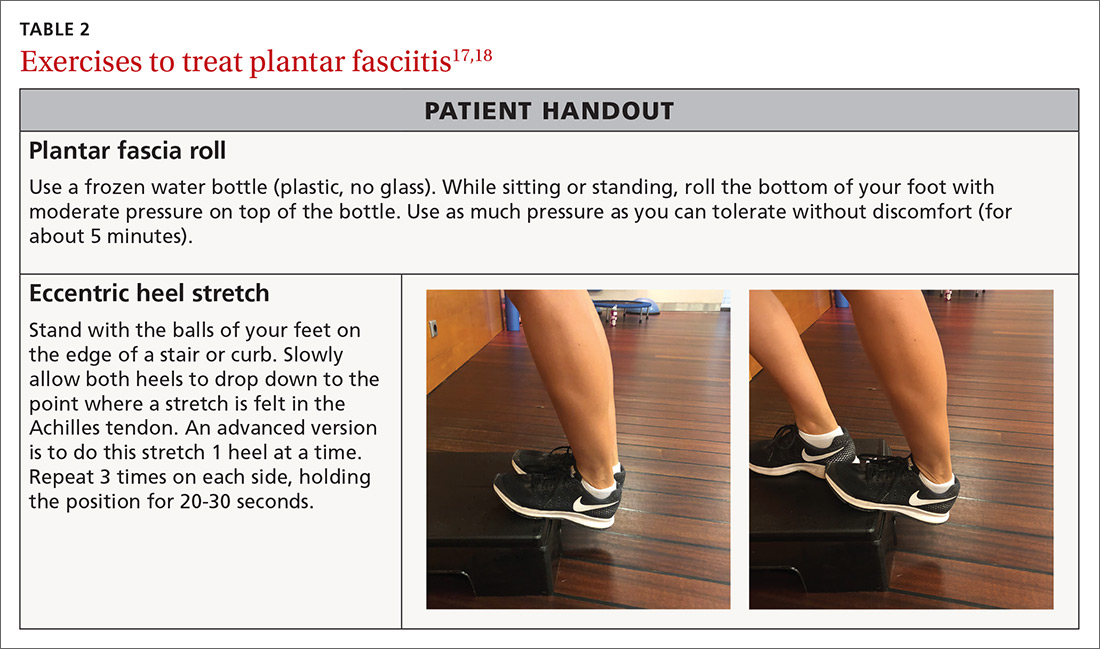

Step 1: Reduce pain and inflammation. Deep-tissue massage and cryotherapy are easy ways to help with pain and inflammation. Deep-tissue massage can be accomplished by rolling the bottom of the foot on a golf or lacrosse ball. A favorite recommendation of ours to reduce inflammation is to use the ice-cup massage, mentioned earlier, for 5 minutes. Or rolling the bottom of the foot on a frozen water bottle will accomplish both tasks at once (TABLE 217,18).

Step 2: Reduce tissue stress. Management tools commonly used to reduce tissue stress are OTC orthotics and night splints. The night splint has been shown to improve symptoms,but patients often stop using it due to discomfort.19 Many kinds of night splints are available, but we have found that the sock variety with a strap to keep the foot in dorsiflexion is best tolerated, and it should be covered by most care plans.

Continue to: Step 3

Step 3: Restore muscle strength and flexibility. Restoring flexibility of the gastrocnemius and soleus is most frequently recommended for treating PF. Strengthening exercises that involve intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the foot and ankle are also essential.17,18 Helpful exercises include those listed in TABLE 1.9-11 Additionally, an eccentric heel stretch can help to alleviate PF symptoms (TABLE 217,18).

A reasonable timeline for follow-up on newly diagnosed PF is 4 to 6 weeks. While many patients will not have recovered in that time, the goal is to document progress in recovery. If no progress is made, consider other treatment modalities.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is one of the most common orthopedic complaints, estimated to comprise 7.3% of all orthopedic visits.20 Commonly called “runner’s knee,” PFPS is the leading cause of anterior knee pain in active individuals. Studies suggest a gender bias, with PFPS being diagnosed more frequently in females than in males, particularly between the ages of 10 and 19.20 Often, there is vague anterior knee pain, or pain that worsens with activities such as climbing hills or stairs, or with long sitting or when fatigued.

In general, unbalanced patellar tracking within the trochlear groove likely leads to this pain. Multiple contributory factors have been described; however, evidence increasingly has shown that deficiencies in hip strength may contribute significantly to maltracking of the patella with resultant pain. Specifically, weakness in hip external rotators and abductors is associated with abnormal lower extremity mechanics.21 One randomized controlled trial by Ferber et al found that therapy protocols directed at hip and core strength showed earlier resolution of pain and greater strength when compared with knee protocols alone.22

We routinely talk to patients about how the knee is the “victim” caught between weak hips and/or flat feet. It is prudent to look for both in the office visit. This can be done with one simple maneuver: Ask your patient to do a squat followed by 3 or 4 single-leg squats on each side. This will often reveal dysfunction at the foot/ankle or weakness in the hips/core as demonstrated by pronated feet (along with valgus tracking of the knees inward) or loss of balance upon squatting.

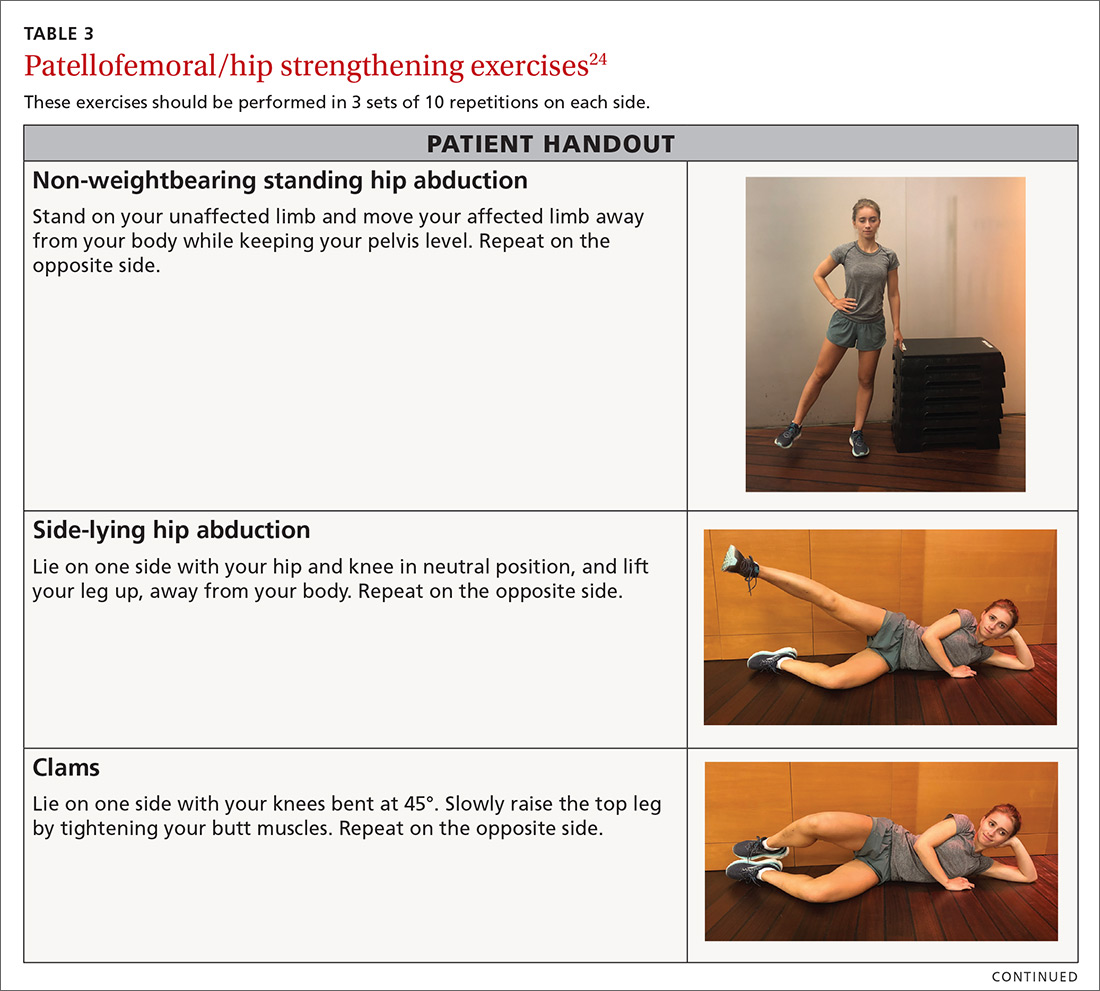

There is general consensus that a nonsurgical approach is the mainstay of treatment for PFPS.23 Pelvic stabilization and hip strengthening are standard components along with treatment protocols of exercises tailored to one’s individual weaknesses.

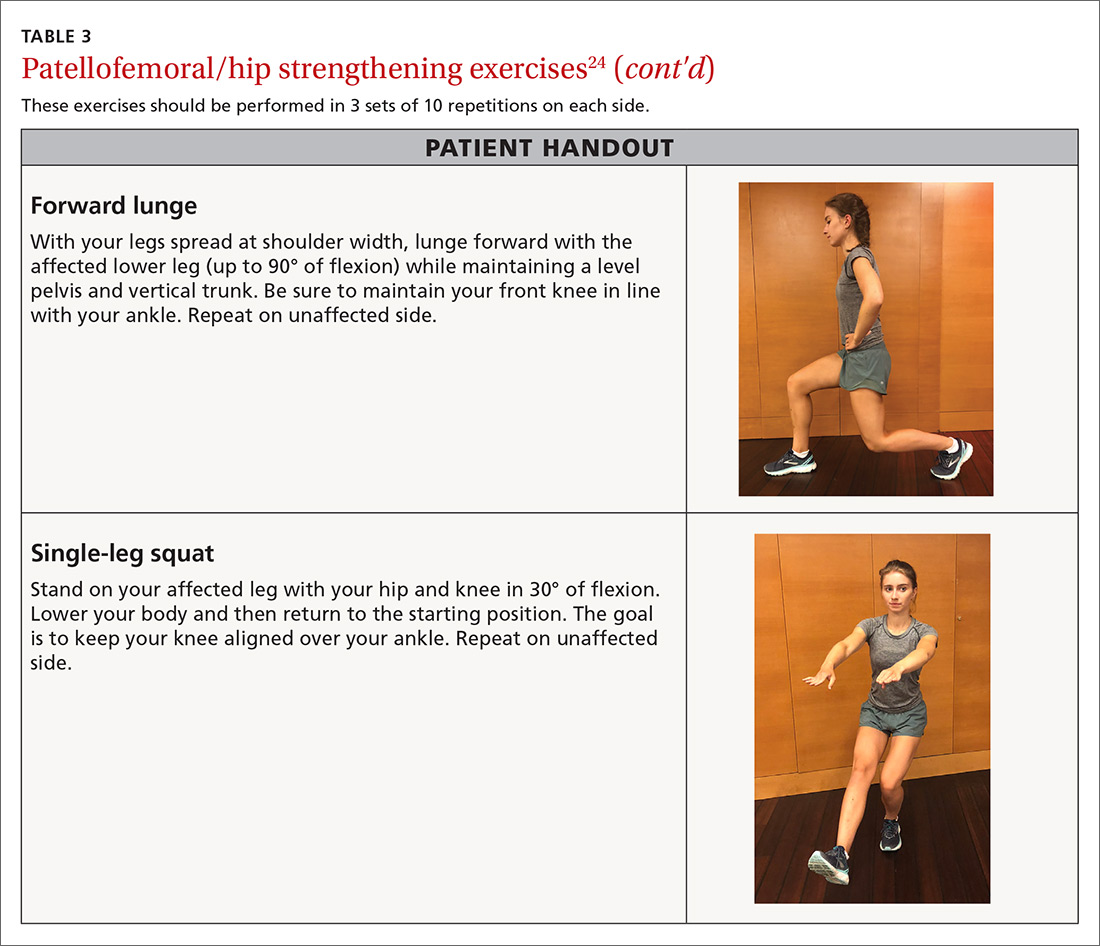

Numerous types of exercises do not require specialized equipment and can be taught in the office (TABLE 324). Explain to patients that the recovery process may take several months. Monthly follow-up to document progress is essential and helps to ensure compliance with one’s home program.

Continue to : Neck pain

Neck pain

The annual prevalence of nonspecific neck pain ranges from 27% to 48%, with 70% of individuals being afflicted at some time in their lives.25 First rule out any neurologic factors that might suggest cervical disc disease or spinal stenosis. If a patient describes weakness or sensory changes along one or both upper extremities, obtain imaging and consider more formalized therapy with a physical therapist.

In patients without any red flags, investigate possible biomechanical causes. It is essential to review the patient’s work and home habits, particularly in light of COVID-19, to determine if adjustments may be needed. Factors to consider are desk and computer setups at work or home, reading or laptop use in bed, sleep habits, and frequency of cellular phone calls/texting.26 A formal ergonomic assessment of the patient’s workplace may be helpful.

A mainstay in treating mechanical neck pain is alleviating trapezial tightness or spasm. Manipulative therapies such as osteopathic manipulation, massage, and chiropractic care can provide pain relief in the acute setting as well as help with control of chronic symptoms.27 A simple self-care tool is using a tennis ball to massage the trapezial muscles. This can be accomplished by having the patient position the tennis ball along the upper trapezial muscles, holding it in place by leaning against a wall, and initiating self-massage. Another method of self-massage is to put 2 tennis balls in an athletic tube sock and tie off the end, place the sock on the floor, and lie on it in the supine position.

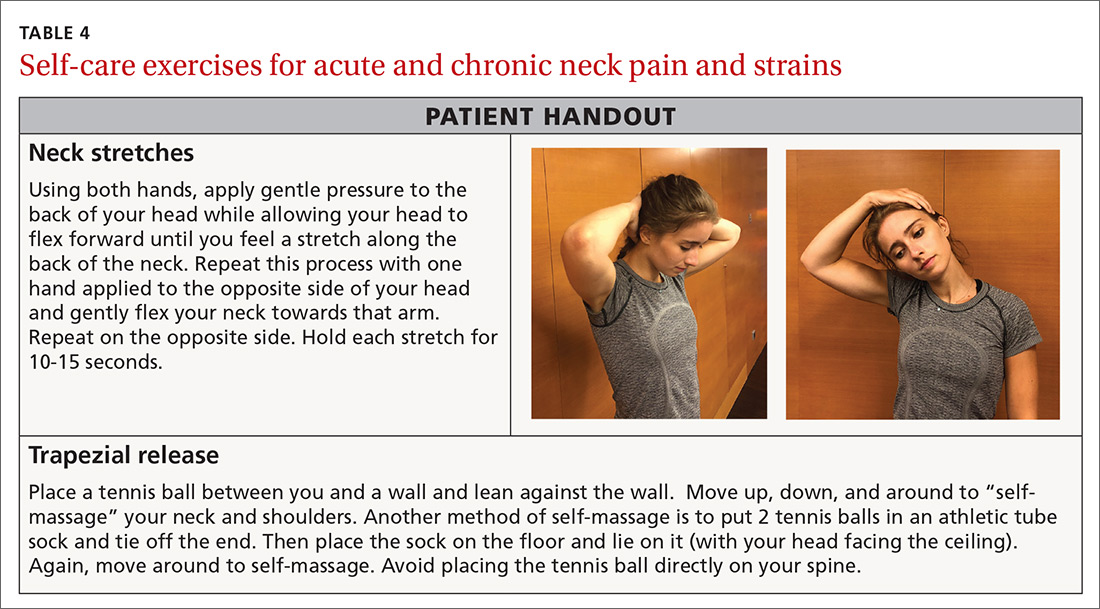

There is also evidence that exercise of any kind can help control neck pain.28,29 The easiest exercises one can offer a patient with neck stiffness, or even mild cervical strains, is self-directed stretching through gentle pressure applied in all 4 directions on the neck. This technique can be repeated hourly both at work and at home (TABLE 4).

Reminders that can help ensure success

You can use the approaches described here for numerous other MSK conditions in helping patients on the road to recovery.

After the acute phase, advise patients to

• apply heat to the affected area before exercising. This can help bring blood flow to the region and promote ease of movement.

• continue icing the area following rehabilitation exercises in order to control exercise-induced inflammation.

• report any changing symptoms such as worsening pain, numbness, or weakness.

These techniques are one step in the recovery process. A home program can benefit the patient either alone or in combination with more advanced techniques that are best accomplished under the watchful eye of a physical or occupational therapist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carrie A. Jaworski, MD, FAAFP, FACSM, 2180 Pfingsten Road, Suite 3100, Glenview, IL 60026; cjaworski@northshore.org

1. Hubbard TJ, Aronson SL, Denegar CR. Does cryotherapy hasten return to participation? A systematic review. J Athl Train. 2004;39:88-94.

2. Ho SS, Coel MN, Kagawa R, et al. The effects of ice on blood flow and bone metabolism in knees. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:537-540.

3. Malanga GA, Yan N, Stark J. Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injury. Postgrad Med. 2015;127:57-65.

4. Bleakley CM, O’Connor S, Tully MA, et al. The PRICE study (Protection Rest Ice Compression Elevation): design of a randomised controlled trial comparing standard versus cryokinetic ice applications in the management of acute ankle sprain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:125.

5. Mayer JM, Ralph L, Look M, et al. Treating acute low back pain with continuous low-level heat wrap therapy and/or exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2005;5:395-403.

6. Cetin N, Aytar A, Atalay A, et al. Comparing hot pack, short-wave diathermy, ultrasound, and TENS on isokinetic strength, pain, and functional status of women with osteoarthritic knees: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:443-451.

7. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, et al. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2279-2284.

8. Fong DT, Hong Y, Chan LK, et al. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Med. 2007;37:73-94.

9. Kerkhoffs GM, Rowe BH, Assendelft WJ, et al. Immobilisation and functional treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(3):CD003762.

10. Mattacola CG, Dwyer MK. Rehabilitation of the ankle after acute sprain or chronic instability. J Ath Train. 2002;37:413-429.

11. Hü bscher M, Zech A, Pfeifer K, et al. Neuromuscular training for sports injury prevention: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:413-421.

12. Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. The effectiveness of a neuromuscular prevention strategy to reduce injuries in youth soccer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:555-562.

13. Tiemstra JD. Update on acute ankle sprains. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1170-1176.

14. Beynnon BD, Murphy DF, Alosa DM. Predictive factors for lateral ankle sprains: a literature review. J Ath Train. 2002;37:376-380.

15. Schiftan GS, Ross LA, Hahne AJ. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18:238–244.

16. Hupperets MD, Verhagen EA, van Mechelen W. Effect of unsupervised home based proprioceptive training on recurrences of ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b2684

17. Thompson JV, Saini SS, Reb CW, et al. Diagnosis and management of plantar fasciitis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014;114:900-906.

18. DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, et al. Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1775-1781.

19. Lee SY, McKeon P, Hertel J. Does the use of orthoses improve self-reported pain and function measures in patients with plantar fasciitis? A meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10:12-18.

20. Glaviano NR, Key M, Hart JM, et al. Demographic and epidemiological trends in patellofemoral pain. J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10: 281-290.

21. Louden JK. Biomechanics and pathomechanics of the patellofemoral joint. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11: 820-830.

22. Ferber R, Bolgla L, Earl-Boehm JE, et al. Strengthening of hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Ath Train. 2015;50: 366-377.

23. Collins NJ, Bisset LM, Crossley KM, et al. Efficacy of nonsurgical interventions for anterior knee pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2013;41:31-49.

24. Bolgla LA. Hip strength and kinematics in patellofemoral syndrome. In: Brotzman SB, Manske RC eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:273-274.

25. Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33(suppl 4):S39-S51.

26. Larsson B, Søgaard K, Rosendal L. Work related neck-shoulder pain: a review on magnitude, risk factors, biochemical characteristics, clinical picture and preventive interventions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007; 21:447-463.

27. Giles LG, Muller R. Chronic spinal pain: a randomized clinical trial comparing medication, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation. Spine. 2003;28:1490-1502.

28. Bronfort G, Evans R, Anderson A, et al. Spinal manipulation, medication, or home exercise with advice for acute and subacute neck pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:1-10.

29. Evans R, Bronfort G, Bittell S, et al. A pilot study for a randomized clinical trial assessing chiropractic care, medical care, and self-care education for acute and subacute neck pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:403-411.

The mainstay of treatment for many musculoskeletal (MSK) complaints is physical or occupational therapy. But often an individual’s underlying biomechanical issue is one that can be easily addressed with a home exercise plan, and, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients may wish to avoid in-person physical therapy. This article describes the rationale for, and methods of providing, home exercises for several MSK conditions commonly seen in the primary care setting.

General rehabilitation principles: First things first

With basic MSK complaints, focus on controlling pain and swelling before undertaking restoration of function. Tailor pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options to the patient’s needs, using first-line modalities such as ice and compression to reduce inflammation, and prescribing scheduled doses of an anti-inflammatory medication to help with both pain and inflammation.

Once pain is sufficiently controlled, have patients begin basic rehabilitation with simple range-of-motion exercises that move the injured region through normal patterns, as tolerated. Later, the patient can progress through more specific exercises to return the injured region to full functional capacity.

Explain to patients that it takes about 7 to 10 days of consistent care to decrease inflammation, but that they should begin prescribed exercises once they are able to tolerate them. Plan a follow-up visit in 2 to 3 weeks to check on the patient’s response to prescribed care.

Which is better, ice or heat?

Ice and heat are both commonly used to treat MSK injuries and pain, although scrutiny of the use of either intervention has increased. Despite the widespread use of these modalities, there is little evidence to support their effect on patient outcomes. The historical consensus has been that ice decreases pain, inflammation, and edema,while heat can facilitate movement in rehabilitation by improving blood flow and decreasing stiffness.1-3 In our practice, we encourage use of both topical modalities as a way to start exercise therapy when pain from the acute injury limits participation. Patients often ask which modality they should use. Ice is generally applied in the acute injury phase (48-72 hours after injury), while heat has been thought to be more beneficial in the chronic stages.

Ccontinue to: When and how to apply ice

When and how to apply ice. Applying an ice pack or a bag of frozen vegetables directly to the affected area will help control pain and swelling. Ice should be applied for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, once an hour. If a patient has sensitivity to cold or if the ice pack is a gel-type, have the patient place a layer (eg, towel) between the ice and skin to avoid injury to the skin. Additional caution should be exercised in patients with peripheral vascular disease, cryoglobulinemia, Raynaud disease, or a history of frostbite at the site.4

An alternative method we sometimes recommend is ice-cup massage. The patient can fill a small paper cup with water and freeze it. The cup is then used to massage the injured area, providing a more active method of icing whereby the cold can penetrate more quickly. Ice-cup massage should be done for 5 to 10 minutes, 3 to 4 times a day.

When and how to apply heat. Heat will help relax and loosen muscles and is a preferred treatment for older injuries, chronic pain, muscle tension, and spasms.5 Because heat can increase blood flow and, likely, inflammation, it should not be used in the acute injury phase. A heating pad or a warm, wet towel can be applied for up to 20 minutes at a time to help relieve pain and tension. Heat is also beneficial before participating in rehab activities as a method of “warming up” a recently injured area.6 However, ice should still be used following activity to prevent any new inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory medications

For an acute injury, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) not only can decrease inflammation and aid in healing but can alleviate pain. We typically start with over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs taken on a schedule. A good suggestion is to have the patient take the scheduled NSAID with food for 7 to 10 days or until symptoms subside.

Topical analgesics

Because oral medications can occasionally cause adverse effects or be contraindicated in some patients, topical analgesics can be a good substitute due to their minimal adverse effects. Acceptable topical medications include NSAIDs, lidocaine, menthol, and arnica. Other than prescribed topical NSAIDs, these products can be applied directly to the painful area on an as-needed basis. Often, a topical patch is a nice option to recommend for use during work or school, and a topical cream or ointment can be used at bedtime.

Continue to: Graduated rehabilitation

Graduated rehabilitation

The following 4 common MSK injuries are ones that can benefit from a graduated approach to rehabilitation at home.

Lateral ankle sprain

Lateral ankle sprain, usually resulting from an inversion mechanism, is the most common type of acute ankle sprain seen in primary care and sports medicine settings.7-9 The injury causes lateral ankle pain and swelling, decreased range of motion and strength, and pain with weight-bearing activities.

Treatment and rehabilitation after this type of injury are critical to restoring normal function and increasing the likelihood of returning to pre-injury levels of activity.9,10 Goals for an acute ankle sprain include controlling swelling, regaining full range of motion, increasing muscle strength and power, and improving balance.

Phase 1: Immediately following injury, have the patient protect the injured area with rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). This will help to decrease swelling and pain. Exercises to regain range of motion, such as stretching and doing ankle “ABCs,” should begin within 48 to 72 hours of the initial injury (TABLE 1).9-11

Continue to: Phase 2

Phase 2: Once the patient has achieved full range of motion and pain is controlled, begin the process of regaining strength. The 4-way ankle exercise program (with elastic tubing) is an easy at-home exercise that has been shown to improve strength in plantar flexion, dorsiflexion, eversion, and inversion (TABLE 1).9-11

Phase 3: Once your patient is able to bear full weight with little to no pain, begin a balance program (TABLE 19-11). This is the most frequently neglected component of rehabilitation and the most common reason patients return with chronic ankle pain or repeat ankle injuries. Deficits in postural stability and balance have been reported in unstable ankles following acute ankle sprains,10,12-15 and studies have shown that individuals with poor stability are at a greater risk of injury.13-16

For most lateral ankle sprains, patients can expect time to recovery to range from 2 to 8 weeks. Longer recoveries are associated with more severe injuries or those that involve the syndesmosis.

Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis (PF) of the foot can be frustrating for a patient due to its chronic nature. Most patients will present with pain in the heel that is aggravated by weight-bearing activities. A conservative management program that focuses on reducing pain and inflammation, reducing tissue stress, and restoring strength and flexibility has been shown to be effective for this type of injury.17,18

Step 1: Reduce pain and inflammation. Deep-tissue massage and cryotherapy are easy ways to help with pain and inflammation. Deep-tissue massage can be accomplished by rolling the bottom of the foot on a golf or lacrosse ball. A favorite recommendation of ours to reduce inflammation is to use the ice-cup massage, mentioned earlier, for 5 minutes. Or rolling the bottom of the foot on a frozen water bottle will accomplish both tasks at once (TABLE 217,18).

Step 2: Reduce tissue stress. Management tools commonly used to reduce tissue stress are OTC orthotics and night splints. The night splint has been shown to improve symptoms,but patients often stop using it due to discomfort.19 Many kinds of night splints are available, but we have found that the sock variety with a strap to keep the foot in dorsiflexion is best tolerated, and it should be covered by most care plans.

Continue to: Step 3

Step 3: Restore muscle strength and flexibility. Restoring flexibility of the gastrocnemius and soleus is most frequently recommended for treating PF. Strengthening exercises that involve intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the foot and ankle are also essential.17,18 Helpful exercises include those listed in TABLE 1.9-11 Additionally, an eccentric heel stretch can help to alleviate PF symptoms (TABLE 217,18).

A reasonable timeline for follow-up on newly diagnosed PF is 4 to 6 weeks. While many patients will not have recovered in that time, the goal is to document progress in recovery. If no progress is made, consider other treatment modalities.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is one of the most common orthopedic complaints, estimated to comprise 7.3% of all orthopedic visits.20 Commonly called “runner’s knee,” PFPS is the leading cause of anterior knee pain in active individuals. Studies suggest a gender bias, with PFPS being diagnosed more frequently in females than in males, particularly between the ages of 10 and 19.20 Often, there is vague anterior knee pain, or pain that worsens with activities such as climbing hills or stairs, or with long sitting or when fatigued.

In general, unbalanced patellar tracking within the trochlear groove likely leads to this pain. Multiple contributory factors have been described; however, evidence increasingly has shown that deficiencies in hip strength may contribute significantly to maltracking of the patella with resultant pain. Specifically, weakness in hip external rotators and abductors is associated with abnormal lower extremity mechanics.21 One randomized controlled trial by Ferber et al found that therapy protocols directed at hip and core strength showed earlier resolution of pain and greater strength when compared with knee protocols alone.22

We routinely talk to patients about how the knee is the “victim” caught between weak hips and/or flat feet. It is prudent to look for both in the office visit. This can be done with one simple maneuver: Ask your patient to do a squat followed by 3 or 4 single-leg squats on each side. This will often reveal dysfunction at the foot/ankle or weakness in the hips/core as demonstrated by pronated feet (along with valgus tracking of the knees inward) or loss of balance upon squatting.

There is general consensus that a nonsurgical approach is the mainstay of treatment for PFPS.23 Pelvic stabilization and hip strengthening are standard components along with treatment protocols of exercises tailored to one’s individual weaknesses.

Numerous types of exercises do not require specialized equipment and can be taught in the office (TABLE 324). Explain to patients that the recovery process may take several months. Monthly follow-up to document progress is essential and helps to ensure compliance with one’s home program.

Continue to : Neck pain

Neck pain

The annual prevalence of nonspecific neck pain ranges from 27% to 48%, with 70% of individuals being afflicted at some time in their lives.25 First rule out any neurologic factors that might suggest cervical disc disease or spinal stenosis. If a patient describes weakness or sensory changes along one or both upper extremities, obtain imaging and consider more formalized therapy with a physical therapist.

In patients without any red flags, investigate possible biomechanical causes. It is essential to review the patient’s work and home habits, particularly in light of COVID-19, to determine if adjustments may be needed. Factors to consider are desk and computer setups at work or home, reading or laptop use in bed, sleep habits, and frequency of cellular phone calls/texting.26 A formal ergonomic assessment of the patient’s workplace may be helpful.

A mainstay in treating mechanical neck pain is alleviating trapezial tightness or spasm. Manipulative therapies such as osteopathic manipulation, massage, and chiropractic care can provide pain relief in the acute setting as well as help with control of chronic symptoms.27 A simple self-care tool is using a tennis ball to massage the trapezial muscles. This can be accomplished by having the patient position the tennis ball along the upper trapezial muscles, holding it in place by leaning against a wall, and initiating self-massage. Another method of self-massage is to put 2 tennis balls in an athletic tube sock and tie off the end, place the sock on the floor, and lie on it in the supine position.

There is also evidence that exercise of any kind can help control neck pain.28,29 The easiest exercises one can offer a patient with neck stiffness, or even mild cervical strains, is self-directed stretching through gentle pressure applied in all 4 directions on the neck. This technique can be repeated hourly both at work and at home (TABLE 4).

Reminders that can help ensure success

You can use the approaches described here for numerous other MSK conditions in helping patients on the road to recovery.

After the acute phase, advise patients to

• apply heat to the affected area before exercising. This can help bring blood flow to the region and promote ease of movement.

• continue icing the area following rehabilitation exercises in order to control exercise-induced inflammation.

• report any changing symptoms such as worsening pain, numbness, or weakness.

These techniques are one step in the recovery process. A home program can benefit the patient either alone or in combination with more advanced techniques that are best accomplished under the watchful eye of a physical or occupational therapist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carrie A. Jaworski, MD, FAAFP, FACSM, 2180 Pfingsten Road, Suite 3100, Glenview, IL 60026; cjaworski@northshore.org

The mainstay of treatment for many musculoskeletal (MSK) complaints is physical or occupational therapy. But often an individual’s underlying biomechanical issue is one that can be easily addressed with a home exercise plan, and, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients may wish to avoid in-person physical therapy. This article describes the rationale for, and methods of providing, home exercises for several MSK conditions commonly seen in the primary care setting.

General rehabilitation principles: First things first

With basic MSK complaints, focus on controlling pain and swelling before undertaking restoration of function. Tailor pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options to the patient’s needs, using first-line modalities such as ice and compression to reduce inflammation, and prescribing scheduled doses of an anti-inflammatory medication to help with both pain and inflammation.

Once pain is sufficiently controlled, have patients begin basic rehabilitation with simple range-of-motion exercises that move the injured region through normal patterns, as tolerated. Later, the patient can progress through more specific exercises to return the injured region to full functional capacity.

Explain to patients that it takes about 7 to 10 days of consistent care to decrease inflammation, but that they should begin prescribed exercises once they are able to tolerate them. Plan a follow-up visit in 2 to 3 weeks to check on the patient’s response to prescribed care.

Which is better, ice or heat?

Ice and heat are both commonly used to treat MSK injuries and pain, although scrutiny of the use of either intervention has increased. Despite the widespread use of these modalities, there is little evidence to support their effect on patient outcomes. The historical consensus has been that ice decreases pain, inflammation, and edema,while heat can facilitate movement in rehabilitation by improving blood flow and decreasing stiffness.1-3 In our practice, we encourage use of both topical modalities as a way to start exercise therapy when pain from the acute injury limits participation. Patients often ask which modality they should use. Ice is generally applied in the acute injury phase (48-72 hours after injury), while heat has been thought to be more beneficial in the chronic stages.

Ccontinue to: When and how to apply ice

When and how to apply ice. Applying an ice pack or a bag of frozen vegetables directly to the affected area will help control pain and swelling. Ice should be applied for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, once an hour. If a patient has sensitivity to cold or if the ice pack is a gel-type, have the patient place a layer (eg, towel) between the ice and skin to avoid injury to the skin. Additional caution should be exercised in patients with peripheral vascular disease, cryoglobulinemia, Raynaud disease, or a history of frostbite at the site.4

An alternative method we sometimes recommend is ice-cup massage. The patient can fill a small paper cup with water and freeze it. The cup is then used to massage the injured area, providing a more active method of icing whereby the cold can penetrate more quickly. Ice-cup massage should be done for 5 to 10 minutes, 3 to 4 times a day.

When and how to apply heat. Heat will help relax and loosen muscles and is a preferred treatment for older injuries, chronic pain, muscle tension, and spasms.5 Because heat can increase blood flow and, likely, inflammation, it should not be used in the acute injury phase. A heating pad or a warm, wet towel can be applied for up to 20 minutes at a time to help relieve pain and tension. Heat is also beneficial before participating in rehab activities as a method of “warming up” a recently injured area.6 However, ice should still be used following activity to prevent any new inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory medications

For an acute injury, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) not only can decrease inflammation and aid in healing but can alleviate pain. We typically start with over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs taken on a schedule. A good suggestion is to have the patient take the scheduled NSAID with food for 7 to 10 days or until symptoms subside.

Topical analgesics

Because oral medications can occasionally cause adverse effects or be contraindicated in some patients, topical analgesics can be a good substitute due to their minimal adverse effects. Acceptable topical medications include NSAIDs, lidocaine, menthol, and arnica. Other than prescribed topical NSAIDs, these products can be applied directly to the painful area on an as-needed basis. Often, a topical patch is a nice option to recommend for use during work or school, and a topical cream or ointment can be used at bedtime.

Continue to: Graduated rehabilitation

Graduated rehabilitation

The following 4 common MSK injuries are ones that can benefit from a graduated approach to rehabilitation at home.

Lateral ankle sprain

Lateral ankle sprain, usually resulting from an inversion mechanism, is the most common type of acute ankle sprain seen in primary care and sports medicine settings.7-9 The injury causes lateral ankle pain and swelling, decreased range of motion and strength, and pain with weight-bearing activities.

Treatment and rehabilitation after this type of injury are critical to restoring normal function and increasing the likelihood of returning to pre-injury levels of activity.9,10 Goals for an acute ankle sprain include controlling swelling, regaining full range of motion, increasing muscle strength and power, and improving balance.

Phase 1: Immediately following injury, have the patient protect the injured area with rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). This will help to decrease swelling and pain. Exercises to regain range of motion, such as stretching and doing ankle “ABCs,” should begin within 48 to 72 hours of the initial injury (TABLE 1).9-11

Continue to: Phase 2

Phase 2: Once the patient has achieved full range of motion and pain is controlled, begin the process of regaining strength. The 4-way ankle exercise program (with elastic tubing) is an easy at-home exercise that has been shown to improve strength in plantar flexion, dorsiflexion, eversion, and inversion (TABLE 1).9-11

Phase 3: Once your patient is able to bear full weight with little to no pain, begin a balance program (TABLE 19-11). This is the most frequently neglected component of rehabilitation and the most common reason patients return with chronic ankle pain or repeat ankle injuries. Deficits in postural stability and balance have been reported in unstable ankles following acute ankle sprains,10,12-15 and studies have shown that individuals with poor stability are at a greater risk of injury.13-16

For most lateral ankle sprains, patients can expect time to recovery to range from 2 to 8 weeks. Longer recoveries are associated with more severe injuries or those that involve the syndesmosis.

Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis (PF) of the foot can be frustrating for a patient due to its chronic nature. Most patients will present with pain in the heel that is aggravated by weight-bearing activities. A conservative management program that focuses on reducing pain and inflammation, reducing tissue stress, and restoring strength and flexibility has been shown to be effective for this type of injury.17,18

Step 1: Reduce pain and inflammation. Deep-tissue massage and cryotherapy are easy ways to help with pain and inflammation. Deep-tissue massage can be accomplished by rolling the bottom of the foot on a golf or lacrosse ball. A favorite recommendation of ours to reduce inflammation is to use the ice-cup massage, mentioned earlier, for 5 minutes. Or rolling the bottom of the foot on a frozen water bottle will accomplish both tasks at once (TABLE 217,18).

Step 2: Reduce tissue stress. Management tools commonly used to reduce tissue stress are OTC orthotics and night splints. The night splint has been shown to improve symptoms,but patients often stop using it due to discomfort.19 Many kinds of night splints are available, but we have found that the sock variety with a strap to keep the foot in dorsiflexion is best tolerated, and it should be covered by most care plans.

Continue to: Step 3

Step 3: Restore muscle strength and flexibility. Restoring flexibility of the gastrocnemius and soleus is most frequently recommended for treating PF. Strengthening exercises that involve intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the foot and ankle are also essential.17,18 Helpful exercises include those listed in TABLE 1.9-11 Additionally, an eccentric heel stretch can help to alleviate PF symptoms (TABLE 217,18).

A reasonable timeline for follow-up on newly diagnosed PF is 4 to 6 weeks. While many patients will not have recovered in that time, the goal is to document progress in recovery. If no progress is made, consider other treatment modalities.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is one of the most common orthopedic complaints, estimated to comprise 7.3% of all orthopedic visits.20 Commonly called “runner’s knee,” PFPS is the leading cause of anterior knee pain in active individuals. Studies suggest a gender bias, with PFPS being diagnosed more frequently in females than in males, particularly between the ages of 10 and 19.20 Often, there is vague anterior knee pain, or pain that worsens with activities such as climbing hills or stairs, or with long sitting or when fatigued.

In general, unbalanced patellar tracking within the trochlear groove likely leads to this pain. Multiple contributory factors have been described; however, evidence increasingly has shown that deficiencies in hip strength may contribute significantly to maltracking of the patella with resultant pain. Specifically, weakness in hip external rotators and abductors is associated with abnormal lower extremity mechanics.21 One randomized controlled trial by Ferber et al found that therapy protocols directed at hip and core strength showed earlier resolution of pain and greater strength when compared with knee protocols alone.22

We routinely talk to patients about how the knee is the “victim” caught between weak hips and/or flat feet. It is prudent to look for both in the office visit. This can be done with one simple maneuver: Ask your patient to do a squat followed by 3 or 4 single-leg squats on each side. This will often reveal dysfunction at the foot/ankle or weakness in the hips/core as demonstrated by pronated feet (along with valgus tracking of the knees inward) or loss of balance upon squatting.

There is general consensus that a nonsurgical approach is the mainstay of treatment for PFPS.23 Pelvic stabilization and hip strengthening are standard components along with treatment protocols of exercises tailored to one’s individual weaknesses.

Numerous types of exercises do not require specialized equipment and can be taught in the office (TABLE 324). Explain to patients that the recovery process may take several months. Monthly follow-up to document progress is essential and helps to ensure compliance with one’s home program.

Continue to : Neck pain

Neck pain

The annual prevalence of nonspecific neck pain ranges from 27% to 48%, with 70% of individuals being afflicted at some time in their lives.25 First rule out any neurologic factors that might suggest cervical disc disease or spinal stenosis. If a patient describes weakness or sensory changes along one or both upper extremities, obtain imaging and consider more formalized therapy with a physical therapist.

In patients without any red flags, investigate possible biomechanical causes. It is essential to review the patient’s work and home habits, particularly in light of COVID-19, to determine if adjustments may be needed. Factors to consider are desk and computer setups at work or home, reading or laptop use in bed, sleep habits, and frequency of cellular phone calls/texting.26 A formal ergonomic assessment of the patient’s workplace may be helpful.

A mainstay in treating mechanical neck pain is alleviating trapezial tightness or spasm. Manipulative therapies such as osteopathic manipulation, massage, and chiropractic care can provide pain relief in the acute setting as well as help with control of chronic symptoms.27 A simple self-care tool is using a tennis ball to massage the trapezial muscles. This can be accomplished by having the patient position the tennis ball along the upper trapezial muscles, holding it in place by leaning against a wall, and initiating self-massage. Another method of self-massage is to put 2 tennis balls in an athletic tube sock and tie off the end, place the sock on the floor, and lie on it in the supine position.

There is also evidence that exercise of any kind can help control neck pain.28,29 The easiest exercises one can offer a patient with neck stiffness, or even mild cervical strains, is self-directed stretching through gentle pressure applied in all 4 directions on the neck. This technique can be repeated hourly both at work and at home (TABLE 4).

Reminders that can help ensure success

You can use the approaches described here for numerous other MSK conditions in helping patients on the road to recovery.

After the acute phase, advise patients to

• apply heat to the affected area before exercising. This can help bring blood flow to the region and promote ease of movement.

• continue icing the area following rehabilitation exercises in order to control exercise-induced inflammation.

• report any changing symptoms such as worsening pain, numbness, or weakness.

These techniques are one step in the recovery process. A home program can benefit the patient either alone or in combination with more advanced techniques that are best accomplished under the watchful eye of a physical or occupational therapist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carrie A. Jaworski, MD, FAAFP, FACSM, 2180 Pfingsten Road, Suite 3100, Glenview, IL 60026; cjaworski@northshore.org

1. Hubbard TJ, Aronson SL, Denegar CR. Does cryotherapy hasten return to participation? A systematic review. J Athl Train. 2004;39:88-94.

2. Ho SS, Coel MN, Kagawa R, et al. The effects of ice on blood flow and bone metabolism in knees. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:537-540.

3. Malanga GA, Yan N, Stark J. Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injury. Postgrad Med. 2015;127:57-65.

4. Bleakley CM, O’Connor S, Tully MA, et al. The PRICE study (Protection Rest Ice Compression Elevation): design of a randomised controlled trial comparing standard versus cryokinetic ice applications in the management of acute ankle sprain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:125.

5. Mayer JM, Ralph L, Look M, et al. Treating acute low back pain with continuous low-level heat wrap therapy and/or exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2005;5:395-403.

6. Cetin N, Aytar A, Atalay A, et al. Comparing hot pack, short-wave diathermy, ultrasound, and TENS on isokinetic strength, pain, and functional status of women with osteoarthritic knees: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:443-451.

7. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, et al. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2279-2284.

8. Fong DT, Hong Y, Chan LK, et al. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Med. 2007;37:73-94.

9. Kerkhoffs GM, Rowe BH, Assendelft WJ, et al. Immobilisation and functional treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(3):CD003762.

10. Mattacola CG, Dwyer MK. Rehabilitation of the ankle after acute sprain or chronic instability. J Ath Train. 2002;37:413-429.

11. Hü bscher M, Zech A, Pfeifer K, et al. Neuromuscular training for sports injury prevention: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:413-421.

12. Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. The effectiveness of a neuromuscular prevention strategy to reduce injuries in youth soccer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:555-562.

13. Tiemstra JD. Update on acute ankle sprains. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1170-1176.

14. Beynnon BD, Murphy DF, Alosa DM. Predictive factors for lateral ankle sprains: a literature review. J Ath Train. 2002;37:376-380.

15. Schiftan GS, Ross LA, Hahne AJ. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18:238–244.

16. Hupperets MD, Verhagen EA, van Mechelen W. Effect of unsupervised home based proprioceptive training on recurrences of ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b2684

17. Thompson JV, Saini SS, Reb CW, et al. Diagnosis and management of plantar fasciitis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014;114:900-906.

18. DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, et al. Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1775-1781.

19. Lee SY, McKeon P, Hertel J. Does the use of orthoses improve self-reported pain and function measures in patients with plantar fasciitis? A meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10:12-18.

20. Glaviano NR, Key M, Hart JM, et al. Demographic and epidemiological trends in patellofemoral pain. J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10: 281-290.

21. Louden JK. Biomechanics and pathomechanics of the patellofemoral joint. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11: 820-830.

22. Ferber R, Bolgla L, Earl-Boehm JE, et al. Strengthening of hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Ath Train. 2015;50: 366-377.

23. Collins NJ, Bisset LM, Crossley KM, et al. Efficacy of nonsurgical interventions for anterior knee pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2013;41:31-49.

24. Bolgla LA. Hip strength and kinematics in patellofemoral syndrome. In: Brotzman SB, Manske RC eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:273-274.

25. Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33(suppl 4):S39-S51.

26. Larsson B, Søgaard K, Rosendal L. Work related neck-shoulder pain: a review on magnitude, risk factors, biochemical characteristics, clinical picture and preventive interventions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007; 21:447-463.

27. Giles LG, Muller R. Chronic spinal pain: a randomized clinical trial comparing medication, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation. Spine. 2003;28:1490-1502.

28. Bronfort G, Evans R, Anderson A, et al. Spinal manipulation, medication, or home exercise with advice for acute and subacute neck pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:1-10.

29. Evans R, Bronfort G, Bittell S, et al. A pilot study for a randomized clinical trial assessing chiropractic care, medical care, and self-care education for acute and subacute neck pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:403-411.

1. Hubbard TJ, Aronson SL, Denegar CR. Does cryotherapy hasten return to participation? A systematic review. J Athl Train. 2004;39:88-94.

2. Ho SS, Coel MN, Kagawa R, et al. The effects of ice on blood flow and bone metabolism in knees. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:537-540.

3. Malanga GA, Yan N, Stark J. Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injury. Postgrad Med. 2015;127:57-65.

4. Bleakley CM, O’Connor S, Tully MA, et al. The PRICE study (Protection Rest Ice Compression Elevation): design of a randomised controlled trial comparing standard versus cryokinetic ice applications in the management of acute ankle sprain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:125.

5. Mayer JM, Ralph L, Look M, et al. Treating acute low back pain with continuous low-level heat wrap therapy and/or exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2005;5:395-403.

6. Cetin N, Aytar A, Atalay A, et al. Comparing hot pack, short-wave diathermy, ultrasound, and TENS on isokinetic strength, pain, and functional status of women with osteoarthritic knees: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:443-451.

7. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, et al. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2279-2284.

8. Fong DT, Hong Y, Chan LK, et al. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Med. 2007;37:73-94.

9. Kerkhoffs GM, Rowe BH, Assendelft WJ, et al. Immobilisation and functional treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(3):CD003762.

10. Mattacola CG, Dwyer MK. Rehabilitation of the ankle after acute sprain or chronic instability. J Ath Train. 2002;37:413-429.

11. Hü bscher M, Zech A, Pfeifer K, et al. Neuromuscular training for sports injury prevention: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:413-421.

12. Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. The effectiveness of a neuromuscular prevention strategy to reduce injuries in youth soccer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:555-562.

13. Tiemstra JD. Update on acute ankle sprains. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1170-1176.

14. Beynnon BD, Murphy DF, Alosa DM. Predictive factors for lateral ankle sprains: a literature review. J Ath Train. 2002;37:376-380.

15. Schiftan GS, Ross LA, Hahne AJ. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18:238–244.

16. Hupperets MD, Verhagen EA, van Mechelen W. Effect of unsupervised home based proprioceptive training on recurrences of ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b2684

17. Thompson JV, Saini SS, Reb CW, et al. Diagnosis and management of plantar fasciitis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014;114:900-906.

18. DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, et al. Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1775-1781.

19. Lee SY, McKeon P, Hertel J. Does the use of orthoses improve self-reported pain and function measures in patients with plantar fasciitis? A meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10:12-18.

20. Glaviano NR, Key M, Hart JM, et al. Demographic and epidemiological trends in patellofemoral pain. J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10: 281-290.

21. Louden JK. Biomechanics and pathomechanics of the patellofemoral joint. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11: 820-830.

22. Ferber R, Bolgla L, Earl-Boehm JE, et al. Strengthening of hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Ath Train. 2015;50: 366-377.

23. Collins NJ, Bisset LM, Crossley KM, et al. Efficacy of nonsurgical interventions for anterior knee pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2013;41:31-49.

24. Bolgla LA. Hip strength and kinematics in patellofemoral syndrome. In: Brotzman SB, Manske RC eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:273-274.

25. Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33(suppl 4):S39-S51.

26. Larsson B, Søgaard K, Rosendal L. Work related neck-shoulder pain: a review on magnitude, risk factors, biochemical characteristics, clinical picture and preventive interventions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007; 21:447-463.

27. Giles LG, Muller R. Chronic spinal pain: a randomized clinical trial comparing medication, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation. Spine. 2003;28:1490-1502.

28. Bronfort G, Evans R, Anderson A, et al. Spinal manipulation, medication, or home exercise with advice for acute and subacute neck pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:1-10.

29. Evans R, Bronfort G, Bittell S, et al. A pilot study for a randomized clinical trial assessing chiropractic care, medical care, and self-care education for acute and subacute neck pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:403-411.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

❯ Have patients apply ice to an acute injury for 15 to 20 minutes at a time to help control inflammation, and prescribe an anti-inflammatory medication, if indicated. A

❯ Reserve heat application for use following the acute phase of injury to decrease stiffness. A

❯ Instruct patients who have an acute lateral ankle sprain to begin “ankle ABCs” and other range-of-motion exercises once acute pain subsides. C

❯ Consider recommending an eccentric heel stretch to help alleviate plantar fasciitis symptoms. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections

In August 2020, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an update of its recommendation on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with behavioral counseling interventions.1

Whom to counsel. The USPSTF continues to recommend behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. Adults at increased risk include those who have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, those with multiple sex partners or a sex partner at high risk for an STI, those not using condoms consistently, and those belonging to populations with high prevalence rates of STIs. These populations with high prevalence rates include1

- individuals seeking care at STI clinics,

- sexual and gender minorities, and

- those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), use injection drugs, exchange sex for drugs or money, or have recently been in a correctional facility.

Features of effective counseling. The Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians provide behavioral counseling or refer to counseling services or suggest media-based interventions. The most effective counseling interventions are those that span more than 120 minutes over several sessions. But the Task Force also states that counseling lasting about 30 minutes in a single session can also be effective. Counseling should include information about common STIs and their modes of transmission; encouragement in the use of safer sex practices; and training in proper condom use, how to communicate with partners about safer sex practices, and problem-solving. Various approaches to this counseling can be found at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

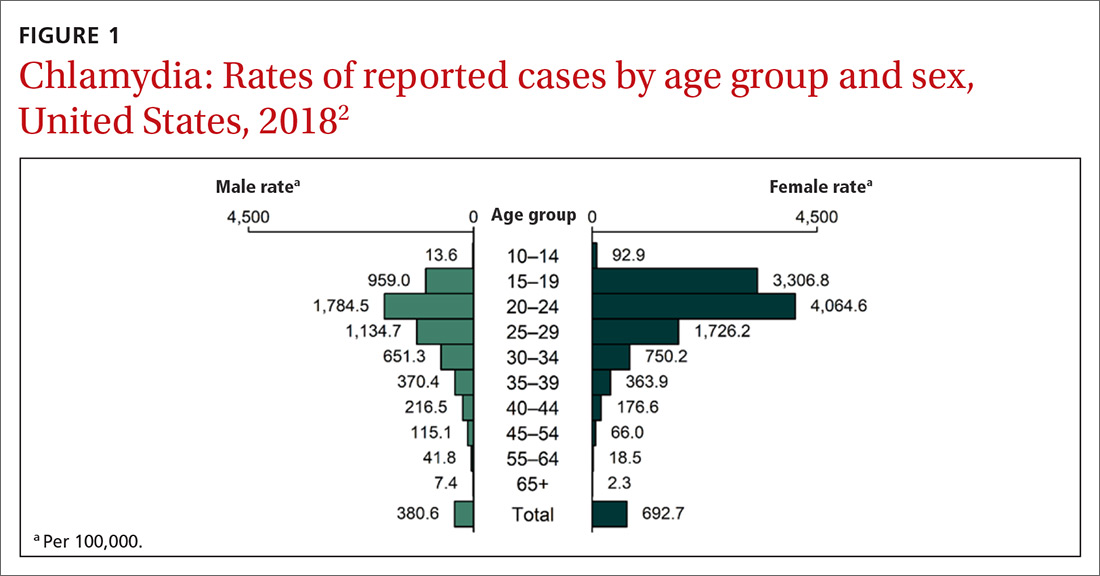

This updated recommendation is timely because most STIs in the United States have been increasing in incidence for the past decade or longer.2 Per 100,000 population, the total number of chlamydia cases since 2000 has risen from 251.4 to 539.9 (115%);gonorrhea cases since 2009 have risen from 98.1 to 179.1 (83%).3 And since 2000, the total number of reported syphilis cases per 100,000 has risen from 2.1 to 10.8 (414%).3

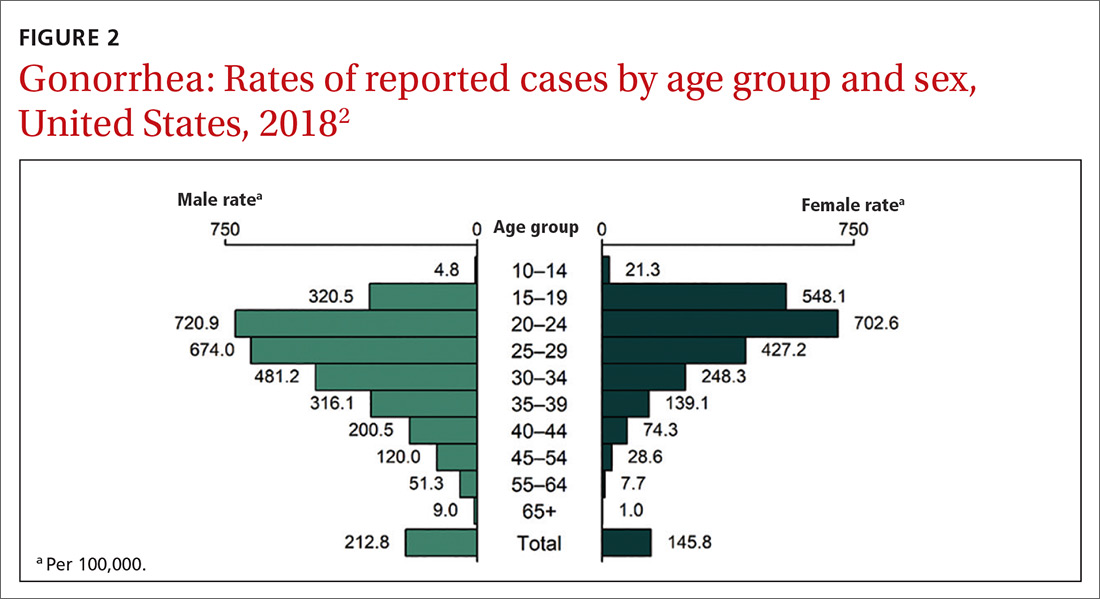

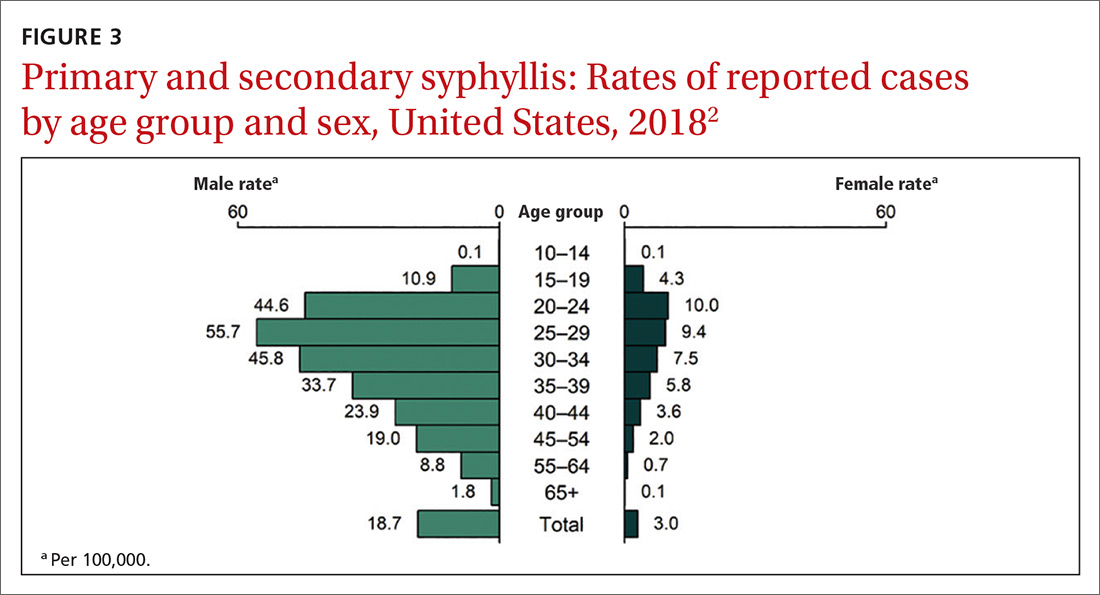

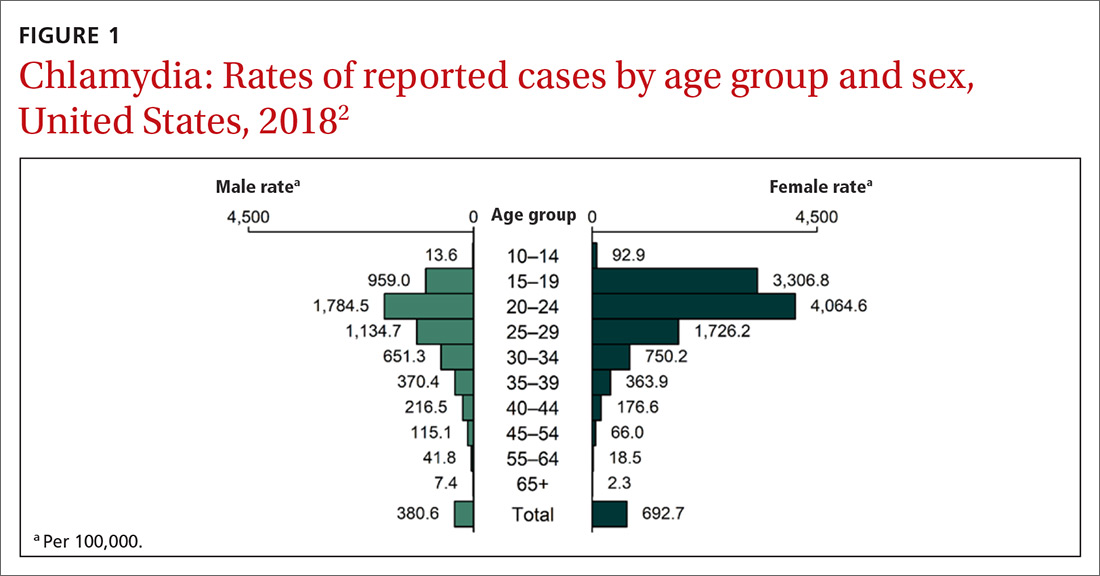

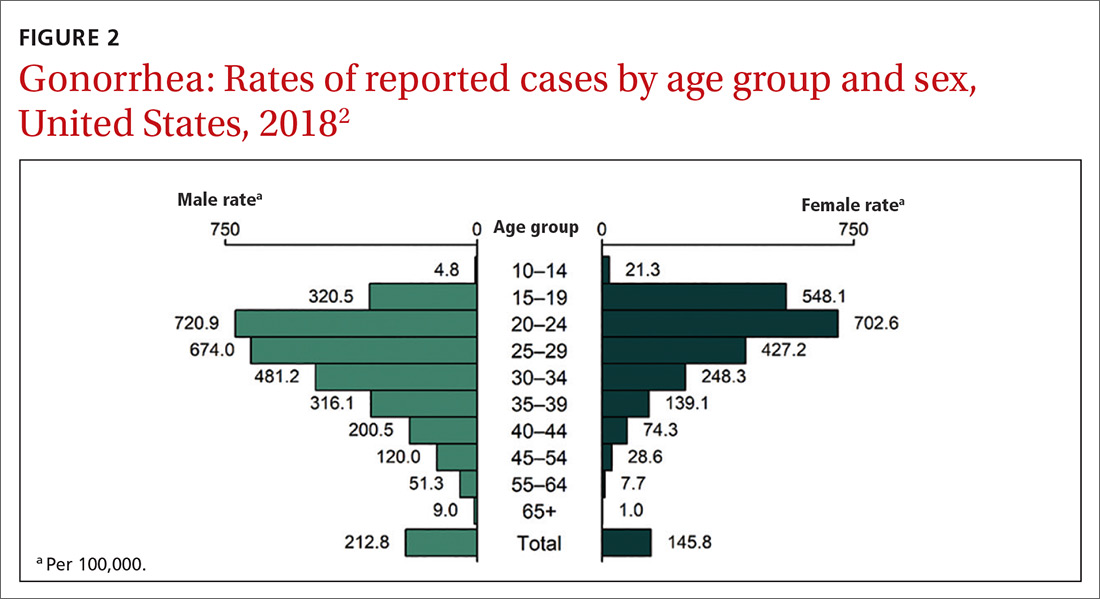

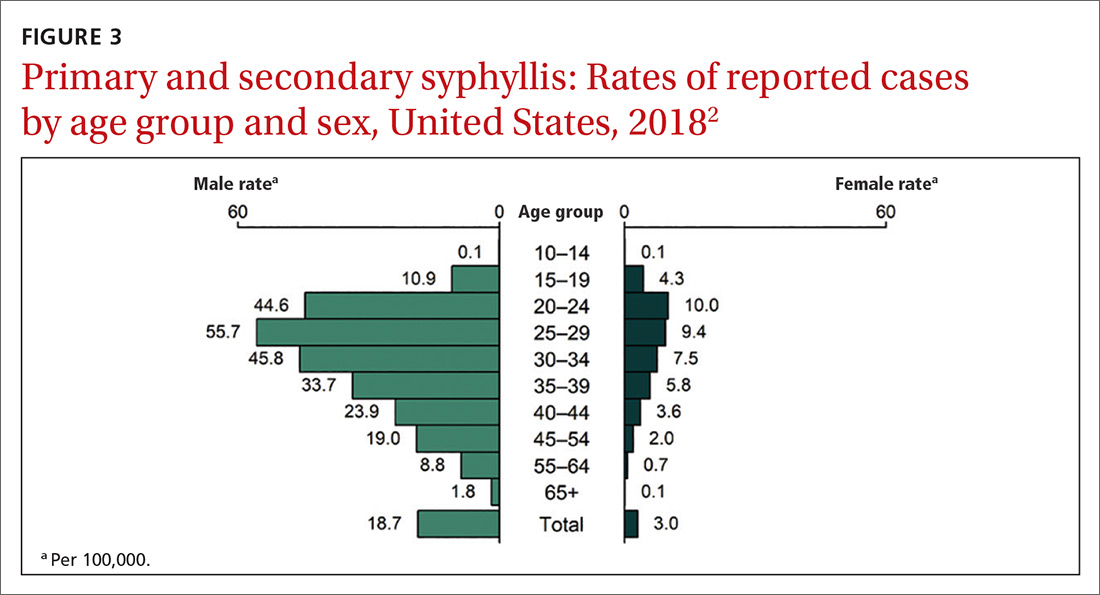

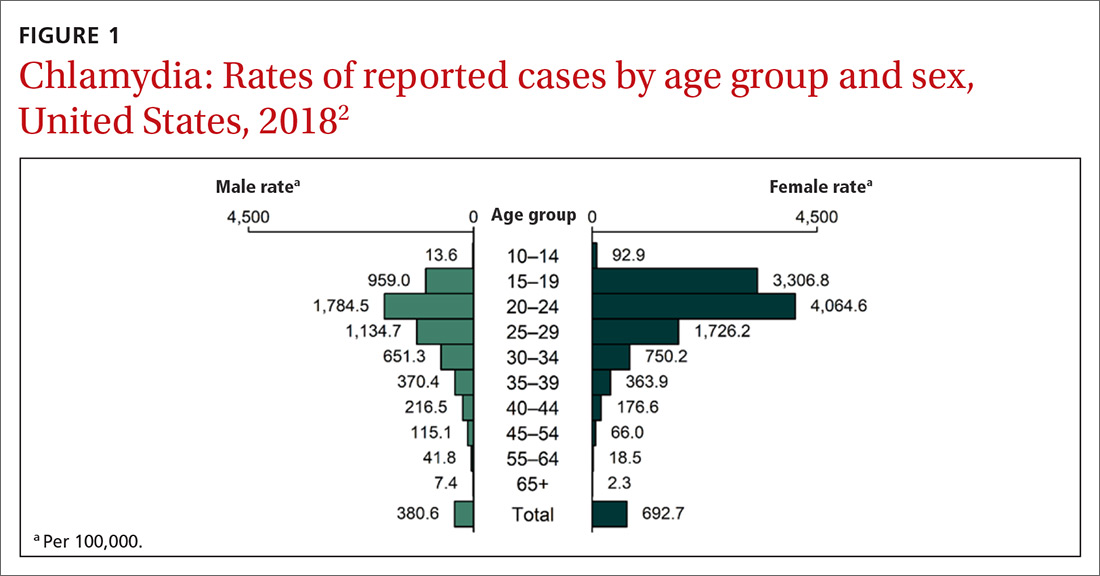

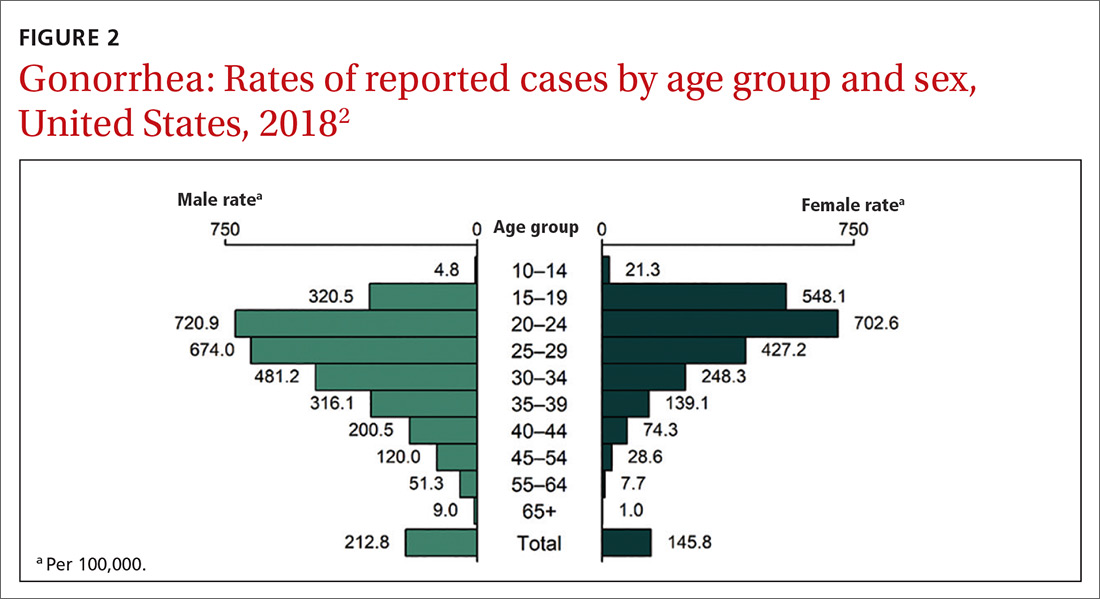

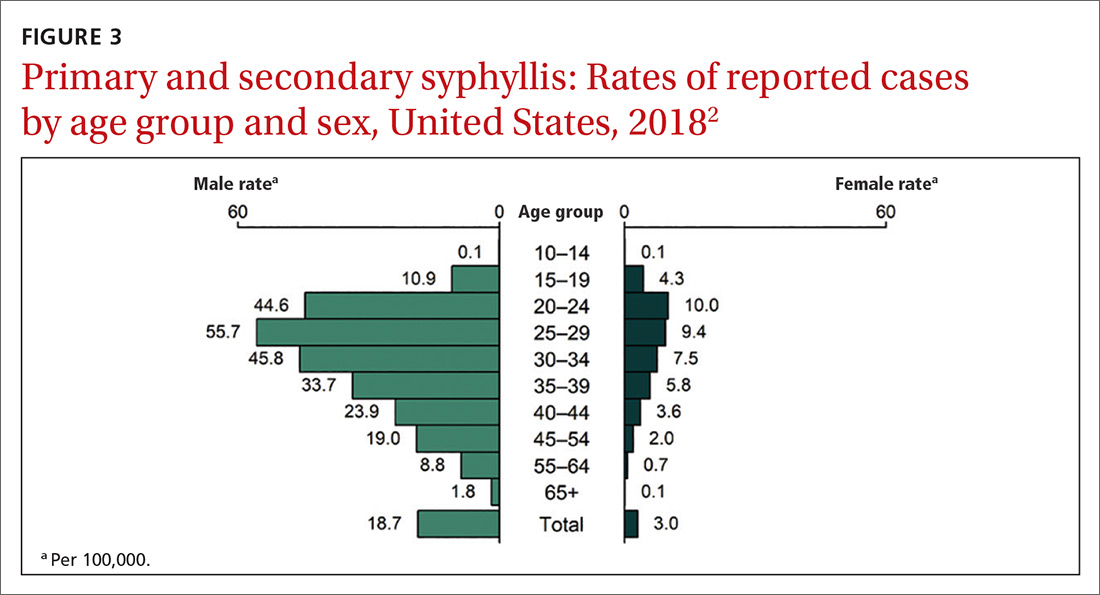

Chlamydia affects primarily those ages 15 to 24 years, with highest rates occurring in females (FIGURE 1).2 Gonorrhea affects women and men fairly evenly with slightly higher rates in men; the highest rates are seen in those ages 20 to 29 (FIGURE 2).2 Syphilis predominantly affects men who have sex with men, and the highest rates are in those ages 20 to 34 (FIGURE 3).2 In contrast to these upward trends, the number of HIV cases diagnosed has been relatively steady, with a slight downward trend over the past decade.4Other STIs that can be prevented through behavioral counseling include herpes simplex, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and trichomonas vaginalis.

Continue to: How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

A key resource for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of STIs, to correctly diagnose them, and to treat them according to CDC guidelines can be found at www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm.5 Equally important is to integrate the prevention of STIs into the clinical routine by using a 4-step approach: risk assessment, risk reduction (counseling and chemoprevention), screening, and vaccination.

Risk assessment. The first step in prevention is taking a sexual history to accurately assess a patient’s risk for STIs. The CDC provides a tool (www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm) that can assist in gathering information in a nonjudgmental fashion about 5 Ps: partners, practices, protection from STIs, past history of STIs, and prevention of pregnancy.

Risk reduction. Following STI risk assessment, recommend risk-reduction interventions, as appropriate. Notable in the new Task Force recommendation are behavioral counseling methods that work. Additionally, when needed, pre-exposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral agents can be offered to those at high risk of HIV.6

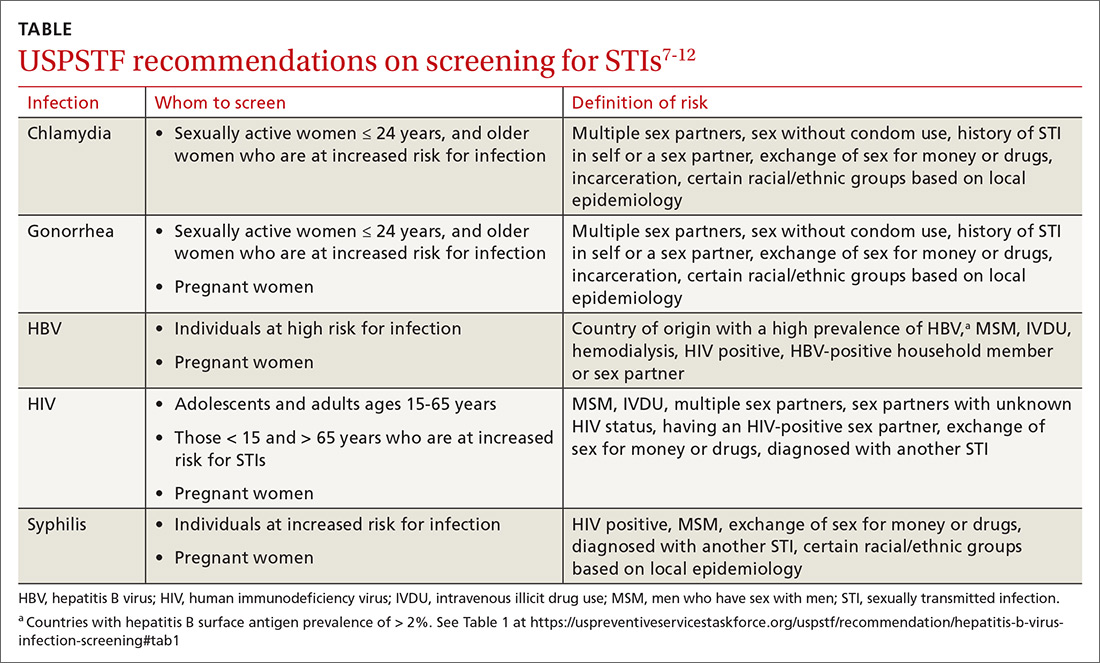

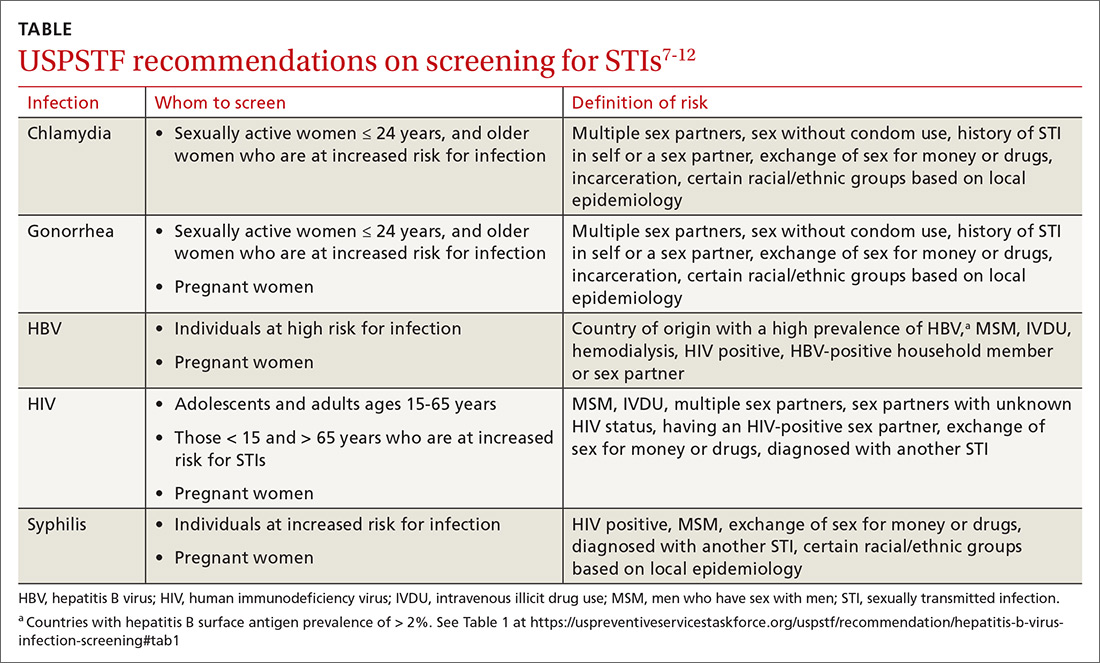

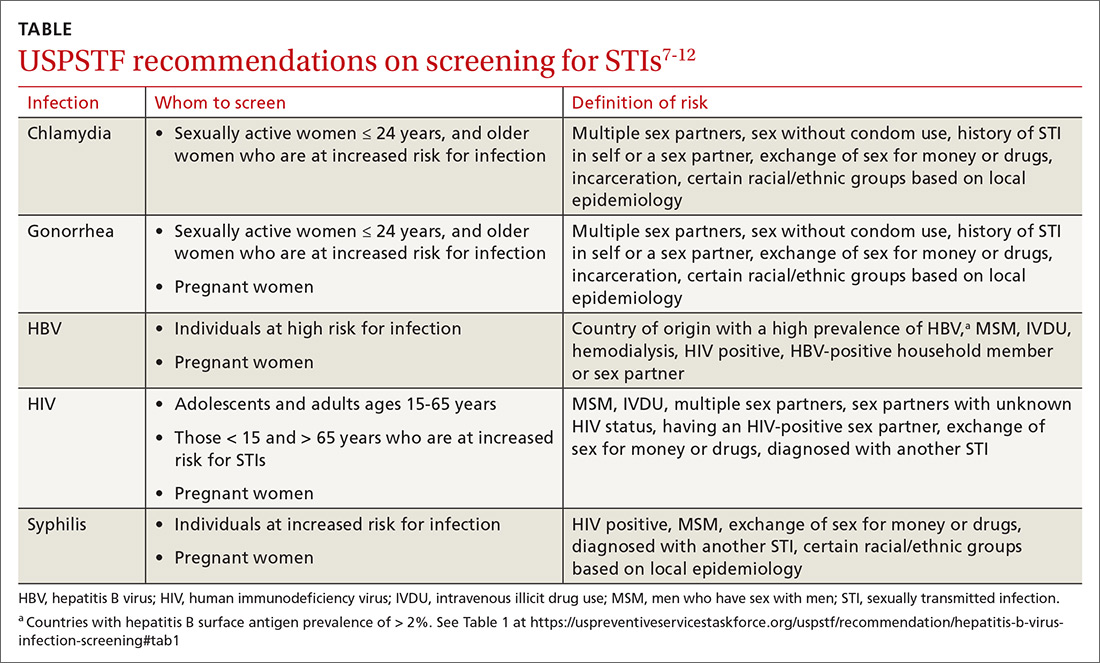

Screening. Task Force recommendations for STI screening are described in the TABLE.7-12 Screening for HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HBV are also recommended for pregnant women. And, although pregnant women are not specifically mentioned in the recommendation on chlamydia screening, it is reasonable to include it in prenatal care testing for STIs.

The Task Force has made an “I” statement regarding screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in males. This does not mean that screening should be avoided, but only that there is insufficient evidence to support a firm statement regarding the harms and benefits in males. Keep in mind that this applies to asymptomatic males, and that testing and preventive treatment are warranted after documented exposure to either infection.

The Task Force recommends against screening for genital herpes, including in pregnant women, because of a lack of evidence of benefit from such screening, the high rate of false-positive tests, and the potential to cause anxiety and harm to personal relationships.

Continue to: Although hepatitis C virus...

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted mainly through intravenous drug use, it can also be transmitted sexually. The Task Force recommends screening for HCV in all adults ages 18 to 79 years.13

Vaccination. Two STIs can be prevented by immunizations: HPV and HBV. The current recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are to vaccinate all infants with HBV vaccine and all unvaccinated children and adolescents through age 18.14 Unvaccinated adults who are at risk for HBV infection, including those at risk through sexual practices, should also be vaccinated.14

ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, but it can be started as early as 9 years.15 Catch-up vaccination is recommended for males and females through age 26 years.15 The vaccine is approved for use in individuals ages 27 through 45 years, but ACIP has not recommended it for routine use in this age group, and has instead recommended shared clinical decision-making to evaluate whether there is potential individual benefit from the vaccine.15

Public health implications

All STIs are reportable to local or state health departments. This is important for tracking community infection trends and, if resources are available, for contact notification and testing. In most jurisdictions, local health department resources are limited and contact tracing may be restricted to syphilis and HIV infections. When this is the case, it is especially important to instruct patients in whom STIs have been detected to notify their recent sex partners and advise them to be tested or preventively treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT)—providing treatment for exposed sexual contacts without a clinical encounter—is allowed in some states and is a tool that can prevent re-infection in the treated patient and suppress spread in the community. This is most useful for partners of those with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas. The CDC has published guidance on how to implement EPT in a clinical setting if state law allows it.16

1. Henderson JT, Senger CA, Henninger M, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2020;324:682-699.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/slides.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

3. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/tables/1.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States (2010-2018). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

5. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Prevention of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection: pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed November 25, 2020.

7. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:902-910. 8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed November 25, 2020.