User login

Addressing Maternal Mortality Through Education: The Mommies Methadone Program

From the UT Health Long School of Medicine San Antonio, Texas.

Abstract

Objective: To educate pregnant patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) about the effects of opioids in order to improve understanding and help achieve sustained abstinence.

Methods: The Center for Health Care Services and University Hospital System (UHS) in San Antonio, TX, jointly o

Results: Of 68 women enrolled in the program, 33 completed both the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Nearly half (48%) were very motivated to quit before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. All participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety. Prior to the educational intervention, 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed on methadone, which improved to 97% in the post-survey, and 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health care providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so.

Conclusion: Pregnancy and education about opioids increased patients’ motivation to quit. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge and learned about patient-provider confidentiality. Our greatest challenge was participant follow-up; however, this improved with the help of a full-time Mommies Program nurse. Our future aim is to increase project awareness and extend the educational research.

Keywords: pregnancy; addiction; opioids; OUD; counseling.

In 2012 more than 259 million prescriptions for opioids were written in the United States, which was a 200% increase since 1998.1 Since the early 2000s, admissions to opioid substance abuse programs and the death rate from opioids have quadrupled.2-4 Specifically, the rate of heroin use increased more than 300% from 2010 to 2014.5 Opioid use in pregnancy has also escalated in recent years, with a 3- to 4-fold increase from 2000 to 2009 and with 4 in 1000 deliveries being complicated by opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2011.6-8

Between 2000 and 2014, the maternal mortality rate in the United States increased 24%, making it the only industrialized nation with a maternal mortality rate that is rising rather than falling.9 The Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force found that between 2012 and 2015 drug overdose was the leading cause of maternal death in the period from delivery to 365 days postpartum, and it has increased dramatically since 2010.10,11

In addition, maternal mortality reviews in several states have identified substance use as a major risk factor for pregnancy-associated deaths.12,13 In Texas between 2012 and 2015, opioids were found in 58% of maternal drug overdoses.10 In 2007, 22.8% of women who were enrolled in Medicaid programs in 46 states filled an opioid prescription during pregnancy.14 Additionally, the rising prevalence of opioid use in pregnancy has led to a sharp increase in neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), rising from 1.5 cases per 1000 hospital births in 1999 to 6.0 per 1000 hospital births in 2013.15 Unsurprisingly, states with the highest rates of opioid prescribing also have the highest rates of NAS.16

Methadone combined with counseling and behavioral therapy has been the standard of care for the treatment of OUD in pregnancy since the 1970s. Methadone treatment prevents opioid withdrawal symptoms and increases adherence to prenatal care.17 One of the largest methadone treatment clinics in the San Antonio, TX, area is the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS). University Health System in San Antonio (UHS) has established a clinic called The Mommies Program, where mothers addicted to opioids can receive prenatal care by a dedicated physician, registered nurse, and a certified nurse midwife, who work in collaboration with the CHCS methadone clinic. Pregnant patients with OUD in pregnancy are concurrently enrolled in the Mommies Program and receive prenatal care through UHS and methadone treatment and counseling through CHCS. The continuity effort aims to increase prenatal care rates and adherence to methadone treatment.

Once mothers are off illicit opioids and on methadone, it is essential to discuss breastfeeding with them, as many mothers addicted to illicit opioids may have been told that they should not be breastfeeding. However, breastfeeding should be encouraged in women who are stable on methadone if they are not using illicit drugs and do not have other contraindications, regardless of maternal methadone dose, since the transfer of methadone into breast milk is minimal.18-20 Breastfeeding is beneficial in women taking methadone and has been associated with decreased severity of NAS symptoms, decreased need for pharmacotherapy, and a shorter hospital stay for the baby.21 In addition, breastfeeding contributes to the development of an attachment between mother and infant, while also providing the infant with natural immunity. Women should be counseled about the need to stop breastfeeding in the event of a relapse.22

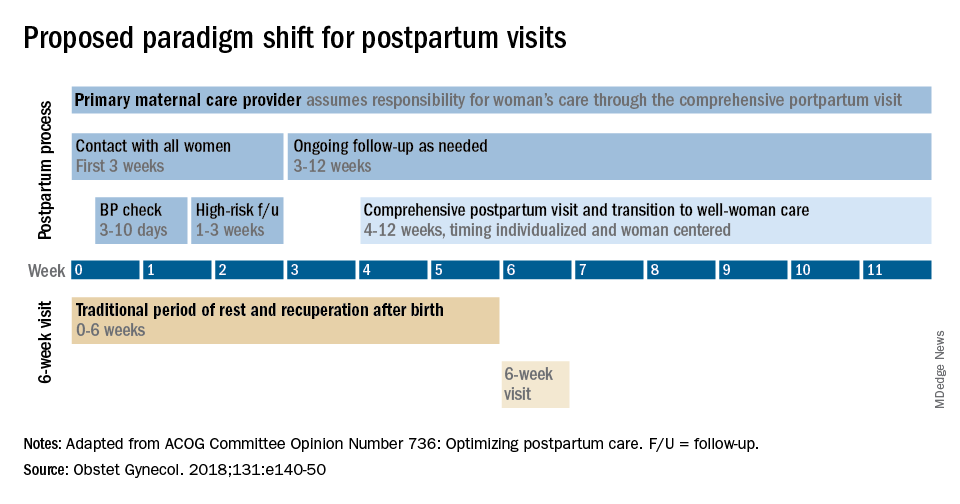

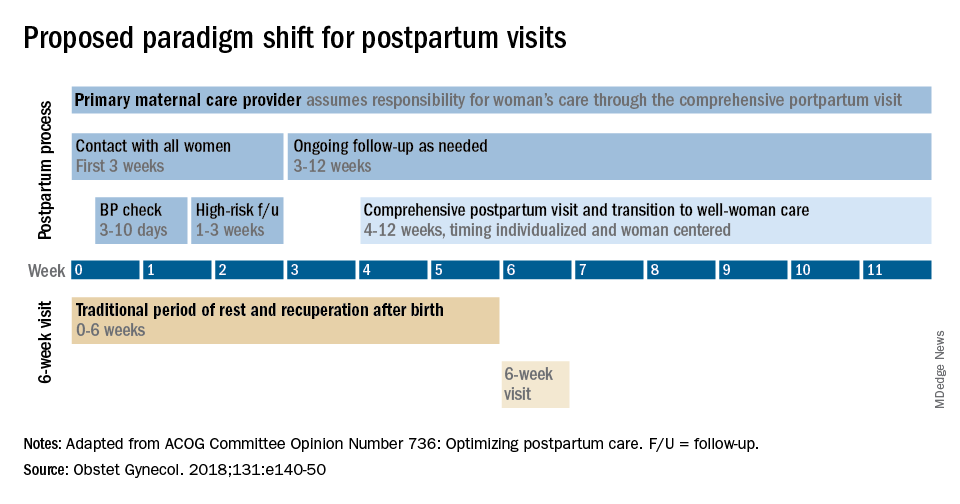

Finally, the postpartum period represents a time of increased stressors, such as loss of sleep, child protective services involvement, and frustration with constant demands from new baby. For mothers with addiction, this is an especially sensitive time, as the stressors may be exacerbated by their new sobriety and a sudden end to the motivation they experienced from pregnancy.23 Therefore, early and frequent postpartum care with methadone dose evaluation is essential in order to decrease drug relapse and screen for postpartum depression in detail, since patients with a history of drug use are at increased risk of postpartum depression.

In 2017 medical students at UT Health Long School of Medicine in San Antonio created a project to educate women about OUD in pregnancy and provide motivational incentives for sustained abstinence; this project has continued each year since. Students provide education about methadone treatment and the dangers of using illicit opioids during and after pregnancy. Students especially focus on educating patients on the key problem areas in the literature, such as overdose, NAS, breastfeeding, postpartum substance use, and postpartum depression.

Methods

From October 2018 to February 2020, a total of 15 medical students volunteered between 1 and 20 times at the Mommies Program clinic, which was held once or twice per week from 8

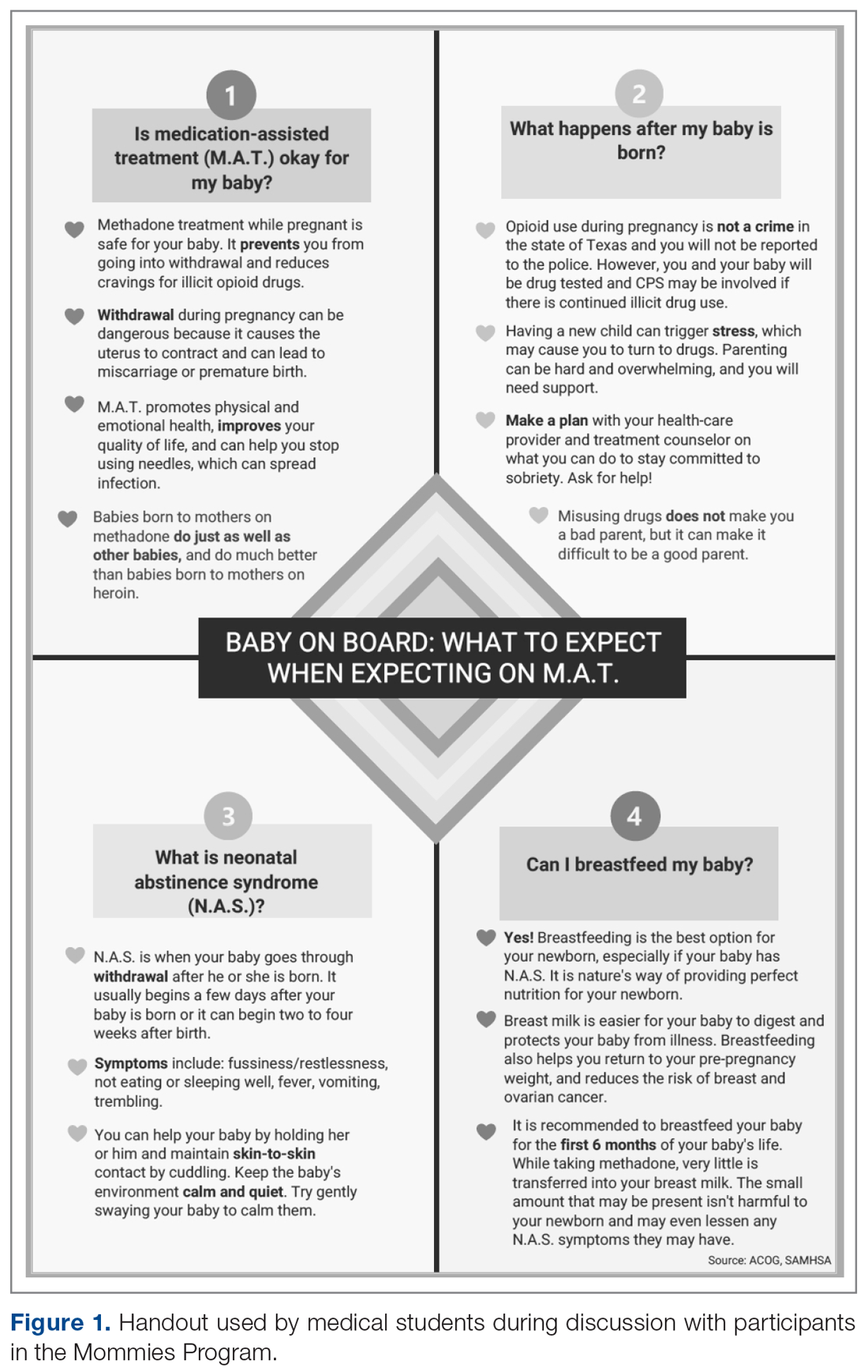

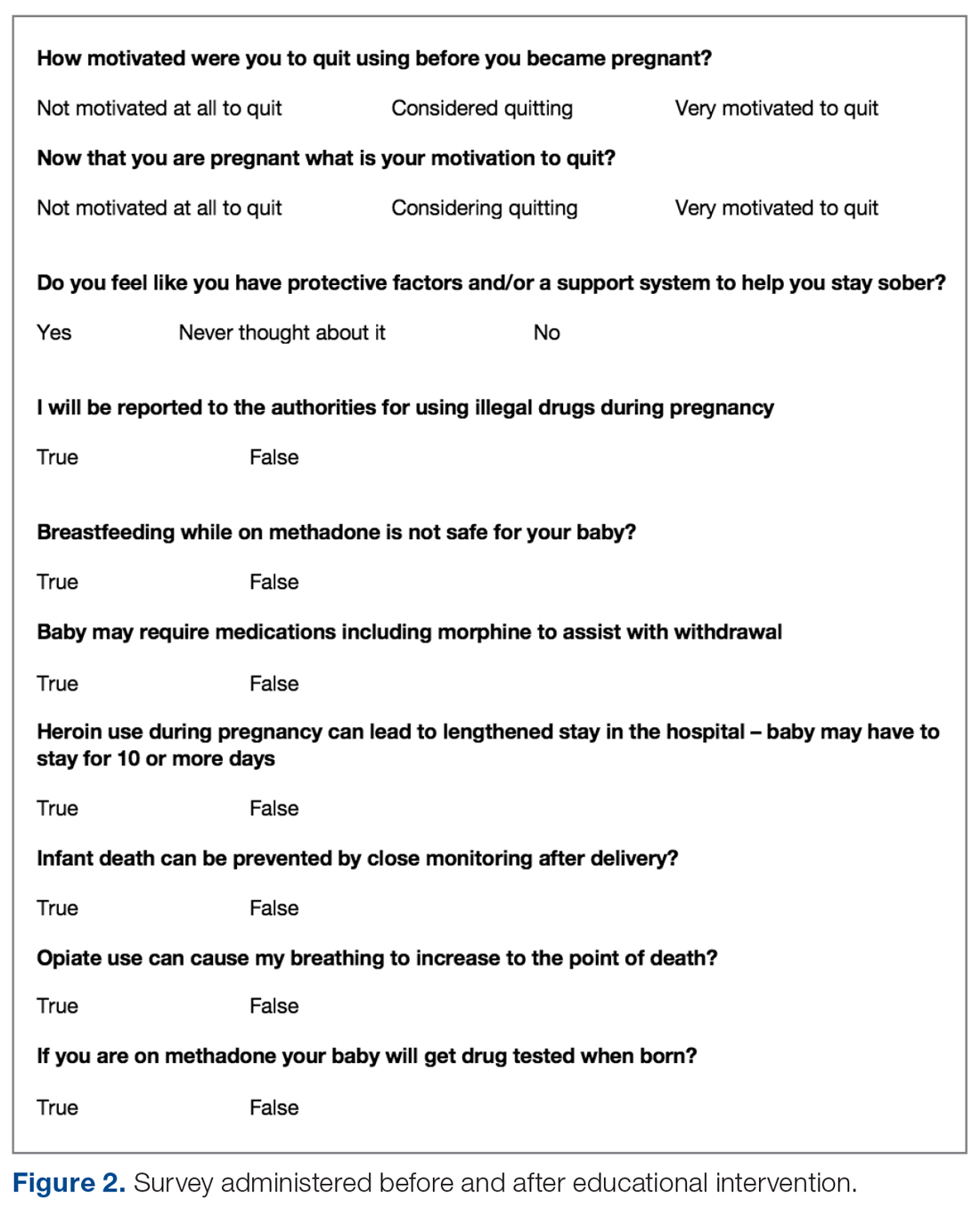

The only inclusion criteria for participating in the educational intervention and survey was participants had to be 18 years of age or older and enrolled in the Mommies Program. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate completed a pre-survey administered by the students during the patient’s initial prenatal visit (Figure 2). This survey collected baseline information about the patient’s history with opioid use and their current knowledge of methadone treatment, NAS, legal aspects of drug use disclosure, and drug testing prior to the education portion of the encounter. After the pre-survey was administered, students spent 30 minutes reviewing the correct answers of the survey with the patients by utilizing the standardized handout to help patients understand details of methadone and opioid use in pregnancy (Figure 1). The post-survey was administered by a student once patients entered the third trimester to assess whether the education session increased patients’ knowledge of these topics.

At the time patients completed the post-survey, they received a Baby Bag as well as education regarding each item in the bag. The aim of distributing Baby Bags was to relieve some possible postnatal stressors and educate the patients about infant care. Items included in the bag were diapers, wipes, bottles, clothes, and swaddles. Prenatal vitamins were added in January 2020, as many patients struggle to afford vitamins if they are not currently covered by Medicaid or have other barriers. The Baby Bag items were purchased through a Community Service Learning grant through UT Health San Antonio.

Results

Of 68 women enrolled in the Mommies Program during the intervention period, 33 completed the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Even though all patients enrolled in the program met the inclusion criteria, patients were not included in the educational program for multiple reasons, including refusal to participate, poor clinic follow-up, or lack of students to collect surveys. However, all patients who completed the pre-survey did complete the post-survey. In the pre-survey, only 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone. In the post-survey, 97% knew it safe to breastfeed. Nearly half (48%) reported being very motivated to quit opioids before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. In the pre-survey, 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so. Also, all participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety.

Discussion

Questions assessed during the educational surveys revolved around patients’ knowledge of the intricacies, legally and physiologically, of methadone treatment for OUD, as well as beneficial aspects for patients and future child health, such as breastfeeding and motivation to quit and stay sober.

It was clear that there was a lack of knowledge and education about breastfeeding, as only 39% of the participants thought that it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone in the pre-survey; in the post survey, this improved to 97%. Students spent a large portion of the educational time going over the safety of breastfeeding for patients on methadone and the many benefits to mother and baby. Students also reviewed breastfeeding with patients every time patients came in for a visit and debunked any falsehoods about the negatives of breastfeeding while on methadone. This is another testament to the benefits of reinforcement around patient education.

The area of trust between provider and patient is essential in all provider-patient relationships. However, in the area of addiction, a trusting bond is especially important, as patients must feel confident and comfortable to disclose every aspect of their lives so the provider can give the best care. It was clear from our initial data that many patients did not feel this trust or understand the legal aspects regarding the provider-patient relationship in the terms of drug use, as the pre-survey shows 76% of patients originally thought they would be reported to authorities if they told their provider they used illegal drugs during pregnancy. This was an enormous issue in the clinic and something that needed to be addressed because, based on these data, we feared many patients would not be honest about using illegal drugs to supplement their methadone if they believed they would be reported to the authorities or even jailed. The medical student education team continually assured patients that their honesty about illegal drug use during pregnancy would not be revealed to the authorities, and also made it clear to patients that it was essential they were honest about illegal drug use so the optimal care could be provided by the team. These discussions were successful, as the post-survey showed that 100% of patients knew they would not be reported to the authorities if they used illegal drugs during the pregnancy. This showed an increase in knowledge, but also suggested an increase in confidence in the provider-patient relationship by patients, which we speculate allowed for a better patient experience, better patient outcomes, and less emotional stress for the patient and provider.

Last, we wanted to study and address the motivation to quit using drugs and stay sober through learning about the effects of opiates and how this motivation was related to pregnancy. A study by Mitchell et al makes clear that pregnancy is a motivation to seek treatment for drug use and to quit,24 and our survey data support these findings, with 48% of patients motivated to quit before they were pregnant and 85% motivated to quit once they knew they were pregnant. In addition, all patients attested on the pre- and post-survey that learning more about opioids would increase their motivation for sobriety. Therefore, we believe education about the use of opioids and other drugs is a strong motivation towards sobriety and should be further studied in methadone treatment and other drugs as well.

We will continue to focus on sobriety postpartum by using the education in pregnancy as a springboard to further postpartum education, as education seems to be very beneficial to future sobriety. In the future, we believe extending the educational program past pregnancy and discussing opioid use and addiction with patients at multiple follow-up visits will be beneficial to patients’ sobriety.

We faced 2 main challenges in implementing this intervention and survey: patients would often miss multiple appointments during their third trimester or would not attend their postpartum visit if they only had 1 prenatal visit; and many clinic sessions had low student attendance because students often had many other responsibilities in medical school and there were only 15 volunteers over the study time. These challenges decreased our post-survey completion rate. However, there has been improvement in follow-up as the project has continued. The Mommies Program now has a full-time registered nurse, and a larger number of medical student teachers have volunteered to attend the clinic. In the future, we aim to increase awareness of our project and the benefits of participation, expand advertising at our medical school to increase student participation, and increase follow-up education in the postpartum period.

Another future direction is to include local, free doula services, which are offered through Catholic Charities in San Antonio. Doulas provide antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum services, which we believe will help our patients through advocacy and support for sobriety during this emotional and stressful time.

Conclusion

Counseled participants were receptive to learning about the effects of OUD and methadone on themselves and their newborn. Participants unanimously stated that learning more about OUD increased their motivation for sobriety. It was also clear that the increased motivation to be sober during pregnancy, as compared to before pregnancy, is an opportunity to help these women take steps to get sober. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge, as we helped debunk falsehoods surrounding breastfeeding while on methadone, and we anticipate this will lead to greater breastfeeding rates for our patients on methadone, although this was not specifically studied. Finally, patients learned about patient-provider confidentiality, which allowed for more open and clear communication with patients so they could be cared for to the greatest degree and trust could remain paramount.

Drug use is a common problem in the health care system, and exposure to patients with addiction is important for medical students in training. We believe that attending the Mommies Program allowed medical students to gain exposure and skills to better help patients with OUD.

Corresponding author: Nicholas Stansbury, MD, Nmstansbury85@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid painkiller prescribing: where you live makes a difference. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2013. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154-63.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug-poisoning deaths. NCHS Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet-drug-poisoning-H.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. Bethesda (MD): NIDA; 2014. www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 28, 2020.

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2011 Contract No.: HHS Publication no. (SMA) 11–4658.

7. Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, et al. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:1158-1165.

8. Whiteman VE, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, et al. Maternal opioid drug use during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal morbidity, mortality, and the costs of medical care in the United States. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:1-8

9. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#trends. Accessed February 4, 2020.

10. Macdorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

11. Texas Health and Human Services. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report, September 2018. www.dshs.texas.gov/legislative/2018-Reports/MMMTFJointReport2018.pdf

12. Virginia Department of Health. Pregnancy-associated deaths from drug overdose in Virginia, 1999-2007: a report from the Virginia Maternal Mortality Review Team. Richmond, VA: VDH; 2015. www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Final-Pregnancy-Associated-Deaths-Due-to-Drug-Overdose.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

13. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Maryland maternal mortality review 2016 annual report. Baltimore: DHMH; 2016. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/Documents/Maryland-Maternal-Mortality-Review-2016-Report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

14. Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:997-1002.

15. Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, et al. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2017;72:703-705.

16. Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35:650-655.

17. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction during pregnancy. In: Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 43. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005:211-224.

18. Wojnar-Horton RE, Kristensen JH, Yapp P, et al. Methadone distribution and excretion into breast milk of clients in a methadone maintenance programme. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:543-547.

19. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:135-141.

20. Sachs HC. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796-809.

21. Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:19.

22. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:488-489.

23. Gopman S. Prenatal and postpartum care of women with substance use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:213-228.

24. Mitchell M, Severtson S, Latimer W. Pregnancy and race/ethnicity as predictors of motivation for drug treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:397-404.

From the UT Health Long School of Medicine San Antonio, Texas.

Abstract

Objective: To educate pregnant patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) about the effects of opioids in order to improve understanding and help achieve sustained abstinence.

Methods: The Center for Health Care Services and University Hospital System (UHS) in San Antonio, TX, jointly o

Results: Of 68 women enrolled in the program, 33 completed both the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Nearly half (48%) were very motivated to quit before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. All participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety. Prior to the educational intervention, 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed on methadone, which improved to 97% in the post-survey, and 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health care providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so.

Conclusion: Pregnancy and education about opioids increased patients’ motivation to quit. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge and learned about patient-provider confidentiality. Our greatest challenge was participant follow-up; however, this improved with the help of a full-time Mommies Program nurse. Our future aim is to increase project awareness and extend the educational research.

Keywords: pregnancy; addiction; opioids; OUD; counseling.

In 2012 more than 259 million prescriptions for opioids were written in the United States, which was a 200% increase since 1998.1 Since the early 2000s, admissions to opioid substance abuse programs and the death rate from opioids have quadrupled.2-4 Specifically, the rate of heroin use increased more than 300% from 2010 to 2014.5 Opioid use in pregnancy has also escalated in recent years, with a 3- to 4-fold increase from 2000 to 2009 and with 4 in 1000 deliveries being complicated by opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2011.6-8

Between 2000 and 2014, the maternal mortality rate in the United States increased 24%, making it the only industrialized nation with a maternal mortality rate that is rising rather than falling.9 The Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force found that between 2012 and 2015 drug overdose was the leading cause of maternal death in the period from delivery to 365 days postpartum, and it has increased dramatically since 2010.10,11

In addition, maternal mortality reviews in several states have identified substance use as a major risk factor for pregnancy-associated deaths.12,13 In Texas between 2012 and 2015, opioids were found in 58% of maternal drug overdoses.10 In 2007, 22.8% of women who were enrolled in Medicaid programs in 46 states filled an opioid prescription during pregnancy.14 Additionally, the rising prevalence of opioid use in pregnancy has led to a sharp increase in neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), rising from 1.5 cases per 1000 hospital births in 1999 to 6.0 per 1000 hospital births in 2013.15 Unsurprisingly, states with the highest rates of opioid prescribing also have the highest rates of NAS.16

Methadone combined with counseling and behavioral therapy has been the standard of care for the treatment of OUD in pregnancy since the 1970s. Methadone treatment prevents opioid withdrawal symptoms and increases adherence to prenatal care.17 One of the largest methadone treatment clinics in the San Antonio, TX, area is the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS). University Health System in San Antonio (UHS) has established a clinic called The Mommies Program, where mothers addicted to opioids can receive prenatal care by a dedicated physician, registered nurse, and a certified nurse midwife, who work in collaboration with the CHCS methadone clinic. Pregnant patients with OUD in pregnancy are concurrently enrolled in the Mommies Program and receive prenatal care through UHS and methadone treatment and counseling through CHCS. The continuity effort aims to increase prenatal care rates and adherence to methadone treatment.

Once mothers are off illicit opioids and on methadone, it is essential to discuss breastfeeding with them, as many mothers addicted to illicit opioids may have been told that they should not be breastfeeding. However, breastfeeding should be encouraged in women who are stable on methadone if they are not using illicit drugs and do not have other contraindications, regardless of maternal methadone dose, since the transfer of methadone into breast milk is minimal.18-20 Breastfeeding is beneficial in women taking methadone and has been associated with decreased severity of NAS symptoms, decreased need for pharmacotherapy, and a shorter hospital stay for the baby.21 In addition, breastfeeding contributes to the development of an attachment between mother and infant, while also providing the infant with natural immunity. Women should be counseled about the need to stop breastfeeding in the event of a relapse.22

Finally, the postpartum period represents a time of increased stressors, such as loss of sleep, child protective services involvement, and frustration with constant demands from new baby. For mothers with addiction, this is an especially sensitive time, as the stressors may be exacerbated by their new sobriety and a sudden end to the motivation they experienced from pregnancy.23 Therefore, early and frequent postpartum care with methadone dose evaluation is essential in order to decrease drug relapse and screen for postpartum depression in detail, since patients with a history of drug use are at increased risk of postpartum depression.

In 2017 medical students at UT Health Long School of Medicine in San Antonio created a project to educate women about OUD in pregnancy and provide motivational incentives for sustained abstinence; this project has continued each year since. Students provide education about methadone treatment and the dangers of using illicit opioids during and after pregnancy. Students especially focus on educating patients on the key problem areas in the literature, such as overdose, NAS, breastfeeding, postpartum substance use, and postpartum depression.

Methods

From October 2018 to February 2020, a total of 15 medical students volunteered between 1 and 20 times at the Mommies Program clinic, which was held once or twice per week from 8

The only inclusion criteria for participating in the educational intervention and survey was participants had to be 18 years of age or older and enrolled in the Mommies Program. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate completed a pre-survey administered by the students during the patient’s initial prenatal visit (Figure 2). This survey collected baseline information about the patient’s history with opioid use and their current knowledge of methadone treatment, NAS, legal aspects of drug use disclosure, and drug testing prior to the education portion of the encounter. After the pre-survey was administered, students spent 30 minutes reviewing the correct answers of the survey with the patients by utilizing the standardized handout to help patients understand details of methadone and opioid use in pregnancy (Figure 1). The post-survey was administered by a student once patients entered the third trimester to assess whether the education session increased patients’ knowledge of these topics.

At the time patients completed the post-survey, they received a Baby Bag as well as education regarding each item in the bag. The aim of distributing Baby Bags was to relieve some possible postnatal stressors and educate the patients about infant care. Items included in the bag were diapers, wipes, bottles, clothes, and swaddles. Prenatal vitamins were added in January 2020, as many patients struggle to afford vitamins if they are not currently covered by Medicaid or have other barriers. The Baby Bag items were purchased through a Community Service Learning grant through UT Health San Antonio.

Results

Of 68 women enrolled in the Mommies Program during the intervention period, 33 completed the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Even though all patients enrolled in the program met the inclusion criteria, patients were not included in the educational program for multiple reasons, including refusal to participate, poor clinic follow-up, or lack of students to collect surveys. However, all patients who completed the pre-survey did complete the post-survey. In the pre-survey, only 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone. In the post-survey, 97% knew it safe to breastfeed. Nearly half (48%) reported being very motivated to quit opioids before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. In the pre-survey, 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so. Also, all participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety.

Discussion

Questions assessed during the educational surveys revolved around patients’ knowledge of the intricacies, legally and physiologically, of methadone treatment for OUD, as well as beneficial aspects for patients and future child health, such as breastfeeding and motivation to quit and stay sober.

It was clear that there was a lack of knowledge and education about breastfeeding, as only 39% of the participants thought that it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone in the pre-survey; in the post survey, this improved to 97%. Students spent a large portion of the educational time going over the safety of breastfeeding for patients on methadone and the many benefits to mother and baby. Students also reviewed breastfeeding with patients every time patients came in for a visit and debunked any falsehoods about the negatives of breastfeeding while on methadone. This is another testament to the benefits of reinforcement around patient education.

The area of trust between provider and patient is essential in all provider-patient relationships. However, in the area of addiction, a trusting bond is especially important, as patients must feel confident and comfortable to disclose every aspect of their lives so the provider can give the best care. It was clear from our initial data that many patients did not feel this trust or understand the legal aspects regarding the provider-patient relationship in the terms of drug use, as the pre-survey shows 76% of patients originally thought they would be reported to authorities if they told their provider they used illegal drugs during pregnancy. This was an enormous issue in the clinic and something that needed to be addressed because, based on these data, we feared many patients would not be honest about using illegal drugs to supplement their methadone if they believed they would be reported to the authorities or even jailed. The medical student education team continually assured patients that their honesty about illegal drug use during pregnancy would not be revealed to the authorities, and also made it clear to patients that it was essential they were honest about illegal drug use so the optimal care could be provided by the team. These discussions were successful, as the post-survey showed that 100% of patients knew they would not be reported to the authorities if they used illegal drugs during the pregnancy. This showed an increase in knowledge, but also suggested an increase in confidence in the provider-patient relationship by patients, which we speculate allowed for a better patient experience, better patient outcomes, and less emotional stress for the patient and provider.

Last, we wanted to study and address the motivation to quit using drugs and stay sober through learning about the effects of opiates and how this motivation was related to pregnancy. A study by Mitchell et al makes clear that pregnancy is a motivation to seek treatment for drug use and to quit,24 and our survey data support these findings, with 48% of patients motivated to quit before they were pregnant and 85% motivated to quit once they knew they were pregnant. In addition, all patients attested on the pre- and post-survey that learning more about opioids would increase their motivation for sobriety. Therefore, we believe education about the use of opioids and other drugs is a strong motivation towards sobriety and should be further studied in methadone treatment and other drugs as well.

We will continue to focus on sobriety postpartum by using the education in pregnancy as a springboard to further postpartum education, as education seems to be very beneficial to future sobriety. In the future, we believe extending the educational program past pregnancy and discussing opioid use and addiction with patients at multiple follow-up visits will be beneficial to patients’ sobriety.

We faced 2 main challenges in implementing this intervention and survey: patients would often miss multiple appointments during their third trimester or would not attend their postpartum visit if they only had 1 prenatal visit; and many clinic sessions had low student attendance because students often had many other responsibilities in medical school and there were only 15 volunteers over the study time. These challenges decreased our post-survey completion rate. However, there has been improvement in follow-up as the project has continued. The Mommies Program now has a full-time registered nurse, and a larger number of medical student teachers have volunteered to attend the clinic. In the future, we aim to increase awareness of our project and the benefits of participation, expand advertising at our medical school to increase student participation, and increase follow-up education in the postpartum period.

Another future direction is to include local, free doula services, which are offered through Catholic Charities in San Antonio. Doulas provide antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum services, which we believe will help our patients through advocacy and support for sobriety during this emotional and stressful time.

Conclusion

Counseled participants were receptive to learning about the effects of OUD and methadone on themselves and their newborn. Participants unanimously stated that learning more about OUD increased their motivation for sobriety. It was also clear that the increased motivation to be sober during pregnancy, as compared to before pregnancy, is an opportunity to help these women take steps to get sober. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge, as we helped debunk falsehoods surrounding breastfeeding while on methadone, and we anticipate this will lead to greater breastfeeding rates for our patients on methadone, although this was not specifically studied. Finally, patients learned about patient-provider confidentiality, which allowed for more open and clear communication with patients so they could be cared for to the greatest degree and trust could remain paramount.

Drug use is a common problem in the health care system, and exposure to patients with addiction is important for medical students in training. We believe that attending the Mommies Program allowed medical students to gain exposure and skills to better help patients with OUD.

Corresponding author: Nicholas Stansbury, MD, Nmstansbury85@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the UT Health Long School of Medicine San Antonio, Texas.

Abstract

Objective: To educate pregnant patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) about the effects of opioids in order to improve understanding and help achieve sustained abstinence.

Methods: The Center for Health Care Services and University Hospital System (UHS) in San Antonio, TX, jointly o

Results: Of 68 women enrolled in the program, 33 completed both the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Nearly half (48%) were very motivated to quit before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. All participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety. Prior to the educational intervention, 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed on methadone, which improved to 97% in the post-survey, and 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health care providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so.

Conclusion: Pregnancy and education about opioids increased patients’ motivation to quit. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge and learned about patient-provider confidentiality. Our greatest challenge was participant follow-up; however, this improved with the help of a full-time Mommies Program nurse. Our future aim is to increase project awareness and extend the educational research.

Keywords: pregnancy; addiction; opioids; OUD; counseling.

In 2012 more than 259 million prescriptions for opioids were written in the United States, which was a 200% increase since 1998.1 Since the early 2000s, admissions to opioid substance abuse programs and the death rate from opioids have quadrupled.2-4 Specifically, the rate of heroin use increased more than 300% from 2010 to 2014.5 Opioid use in pregnancy has also escalated in recent years, with a 3- to 4-fold increase from 2000 to 2009 and with 4 in 1000 deliveries being complicated by opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2011.6-8

Between 2000 and 2014, the maternal mortality rate in the United States increased 24%, making it the only industrialized nation with a maternal mortality rate that is rising rather than falling.9 The Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force found that between 2012 and 2015 drug overdose was the leading cause of maternal death in the period from delivery to 365 days postpartum, and it has increased dramatically since 2010.10,11

In addition, maternal mortality reviews in several states have identified substance use as a major risk factor for pregnancy-associated deaths.12,13 In Texas between 2012 and 2015, opioids were found in 58% of maternal drug overdoses.10 In 2007, 22.8% of women who were enrolled in Medicaid programs in 46 states filled an opioid prescription during pregnancy.14 Additionally, the rising prevalence of opioid use in pregnancy has led to a sharp increase in neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), rising from 1.5 cases per 1000 hospital births in 1999 to 6.0 per 1000 hospital births in 2013.15 Unsurprisingly, states with the highest rates of opioid prescribing also have the highest rates of NAS.16

Methadone combined with counseling and behavioral therapy has been the standard of care for the treatment of OUD in pregnancy since the 1970s. Methadone treatment prevents opioid withdrawal symptoms and increases adherence to prenatal care.17 One of the largest methadone treatment clinics in the San Antonio, TX, area is the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS). University Health System in San Antonio (UHS) has established a clinic called The Mommies Program, where mothers addicted to opioids can receive prenatal care by a dedicated physician, registered nurse, and a certified nurse midwife, who work in collaboration with the CHCS methadone clinic. Pregnant patients with OUD in pregnancy are concurrently enrolled in the Mommies Program and receive prenatal care through UHS and methadone treatment and counseling through CHCS. The continuity effort aims to increase prenatal care rates and adherence to methadone treatment.

Once mothers are off illicit opioids and on methadone, it is essential to discuss breastfeeding with them, as many mothers addicted to illicit opioids may have been told that they should not be breastfeeding. However, breastfeeding should be encouraged in women who are stable on methadone if they are not using illicit drugs and do not have other contraindications, regardless of maternal methadone dose, since the transfer of methadone into breast milk is minimal.18-20 Breastfeeding is beneficial in women taking methadone and has been associated with decreased severity of NAS symptoms, decreased need for pharmacotherapy, and a shorter hospital stay for the baby.21 In addition, breastfeeding contributes to the development of an attachment between mother and infant, while also providing the infant with natural immunity. Women should be counseled about the need to stop breastfeeding in the event of a relapse.22

Finally, the postpartum period represents a time of increased stressors, such as loss of sleep, child protective services involvement, and frustration with constant demands from new baby. For mothers with addiction, this is an especially sensitive time, as the stressors may be exacerbated by their new sobriety and a sudden end to the motivation they experienced from pregnancy.23 Therefore, early and frequent postpartum care with methadone dose evaluation is essential in order to decrease drug relapse and screen for postpartum depression in detail, since patients with a history of drug use are at increased risk of postpartum depression.

In 2017 medical students at UT Health Long School of Medicine in San Antonio created a project to educate women about OUD in pregnancy and provide motivational incentives for sustained abstinence; this project has continued each year since. Students provide education about methadone treatment and the dangers of using illicit opioids during and after pregnancy. Students especially focus on educating patients on the key problem areas in the literature, such as overdose, NAS, breastfeeding, postpartum substance use, and postpartum depression.

Methods

From October 2018 to February 2020, a total of 15 medical students volunteered between 1 and 20 times at the Mommies Program clinic, which was held once or twice per week from 8

The only inclusion criteria for participating in the educational intervention and survey was participants had to be 18 years of age or older and enrolled in the Mommies Program. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate completed a pre-survey administered by the students during the patient’s initial prenatal visit (Figure 2). This survey collected baseline information about the patient’s history with opioid use and their current knowledge of methadone treatment, NAS, legal aspects of drug use disclosure, and drug testing prior to the education portion of the encounter. After the pre-survey was administered, students spent 30 minutes reviewing the correct answers of the survey with the patients by utilizing the standardized handout to help patients understand details of methadone and opioid use in pregnancy (Figure 1). The post-survey was administered by a student once patients entered the third trimester to assess whether the education session increased patients’ knowledge of these topics.

At the time patients completed the post-survey, they received a Baby Bag as well as education regarding each item in the bag. The aim of distributing Baby Bags was to relieve some possible postnatal stressors and educate the patients about infant care. Items included in the bag were diapers, wipes, bottles, clothes, and swaddles. Prenatal vitamins were added in January 2020, as many patients struggle to afford vitamins if they are not currently covered by Medicaid or have other barriers. The Baby Bag items were purchased through a Community Service Learning grant through UT Health San Antonio.

Results

Of 68 women enrolled in the Mommies Program during the intervention period, 33 completed the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Even though all patients enrolled in the program met the inclusion criteria, patients were not included in the educational program for multiple reasons, including refusal to participate, poor clinic follow-up, or lack of students to collect surveys. However, all patients who completed the pre-survey did complete the post-survey. In the pre-survey, only 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone. In the post-survey, 97% knew it safe to breastfeed. Nearly half (48%) reported being very motivated to quit opioids before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. In the pre-survey, 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so. Also, all participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety.

Discussion

Questions assessed during the educational surveys revolved around patients’ knowledge of the intricacies, legally and physiologically, of methadone treatment for OUD, as well as beneficial aspects for patients and future child health, such as breastfeeding and motivation to quit and stay sober.

It was clear that there was a lack of knowledge and education about breastfeeding, as only 39% of the participants thought that it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone in the pre-survey; in the post survey, this improved to 97%. Students spent a large portion of the educational time going over the safety of breastfeeding for patients on methadone and the many benefits to mother and baby. Students also reviewed breastfeeding with patients every time patients came in for a visit and debunked any falsehoods about the negatives of breastfeeding while on methadone. This is another testament to the benefits of reinforcement around patient education.

The area of trust between provider and patient is essential in all provider-patient relationships. However, in the area of addiction, a trusting bond is especially important, as patients must feel confident and comfortable to disclose every aspect of their lives so the provider can give the best care. It was clear from our initial data that many patients did not feel this trust or understand the legal aspects regarding the provider-patient relationship in the terms of drug use, as the pre-survey shows 76% of patients originally thought they would be reported to authorities if they told their provider they used illegal drugs during pregnancy. This was an enormous issue in the clinic and something that needed to be addressed because, based on these data, we feared many patients would not be honest about using illegal drugs to supplement their methadone if they believed they would be reported to the authorities or even jailed. The medical student education team continually assured patients that their honesty about illegal drug use during pregnancy would not be revealed to the authorities, and also made it clear to patients that it was essential they were honest about illegal drug use so the optimal care could be provided by the team. These discussions were successful, as the post-survey showed that 100% of patients knew they would not be reported to the authorities if they used illegal drugs during the pregnancy. This showed an increase in knowledge, but also suggested an increase in confidence in the provider-patient relationship by patients, which we speculate allowed for a better patient experience, better patient outcomes, and less emotional stress for the patient and provider.

Last, we wanted to study and address the motivation to quit using drugs and stay sober through learning about the effects of opiates and how this motivation was related to pregnancy. A study by Mitchell et al makes clear that pregnancy is a motivation to seek treatment for drug use and to quit,24 and our survey data support these findings, with 48% of patients motivated to quit before they were pregnant and 85% motivated to quit once they knew they were pregnant. In addition, all patients attested on the pre- and post-survey that learning more about opioids would increase their motivation for sobriety. Therefore, we believe education about the use of opioids and other drugs is a strong motivation towards sobriety and should be further studied in methadone treatment and other drugs as well.

We will continue to focus on sobriety postpartum by using the education in pregnancy as a springboard to further postpartum education, as education seems to be very beneficial to future sobriety. In the future, we believe extending the educational program past pregnancy and discussing opioid use and addiction with patients at multiple follow-up visits will be beneficial to patients’ sobriety.

We faced 2 main challenges in implementing this intervention and survey: patients would often miss multiple appointments during their third trimester or would not attend their postpartum visit if they only had 1 prenatal visit; and many clinic sessions had low student attendance because students often had many other responsibilities in medical school and there were only 15 volunteers over the study time. These challenges decreased our post-survey completion rate. However, there has been improvement in follow-up as the project has continued. The Mommies Program now has a full-time registered nurse, and a larger number of medical student teachers have volunteered to attend the clinic. In the future, we aim to increase awareness of our project and the benefits of participation, expand advertising at our medical school to increase student participation, and increase follow-up education in the postpartum period.

Another future direction is to include local, free doula services, which are offered through Catholic Charities in San Antonio. Doulas provide antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum services, which we believe will help our patients through advocacy and support for sobriety during this emotional and stressful time.

Conclusion

Counseled participants were receptive to learning about the effects of OUD and methadone on themselves and their newborn. Participants unanimously stated that learning more about OUD increased their motivation for sobriety. It was also clear that the increased motivation to be sober during pregnancy, as compared to before pregnancy, is an opportunity to help these women take steps to get sober. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge, as we helped debunk falsehoods surrounding breastfeeding while on methadone, and we anticipate this will lead to greater breastfeeding rates for our patients on methadone, although this was not specifically studied. Finally, patients learned about patient-provider confidentiality, which allowed for more open and clear communication with patients so they could be cared for to the greatest degree and trust could remain paramount.

Drug use is a common problem in the health care system, and exposure to patients with addiction is important for medical students in training. We believe that attending the Mommies Program allowed medical students to gain exposure and skills to better help patients with OUD.

Corresponding author: Nicholas Stansbury, MD, Nmstansbury85@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid painkiller prescribing: where you live makes a difference. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2013. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154-63.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug-poisoning deaths. NCHS Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet-drug-poisoning-H.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. Bethesda (MD): NIDA; 2014. www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 28, 2020.

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2011 Contract No.: HHS Publication no. (SMA) 11–4658.

7. Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, et al. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:1158-1165.

8. Whiteman VE, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, et al. Maternal opioid drug use during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal morbidity, mortality, and the costs of medical care in the United States. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:1-8

9. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#trends. Accessed February 4, 2020.

10. Macdorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

11. Texas Health and Human Services. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report, September 2018. www.dshs.texas.gov/legislative/2018-Reports/MMMTFJointReport2018.pdf

12. Virginia Department of Health. Pregnancy-associated deaths from drug overdose in Virginia, 1999-2007: a report from the Virginia Maternal Mortality Review Team. Richmond, VA: VDH; 2015. www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Final-Pregnancy-Associated-Deaths-Due-to-Drug-Overdose.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

13. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Maryland maternal mortality review 2016 annual report. Baltimore: DHMH; 2016. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/Documents/Maryland-Maternal-Mortality-Review-2016-Report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

14. Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:997-1002.

15. Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, et al. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2017;72:703-705.

16. Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35:650-655.

17. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction during pregnancy. In: Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 43. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005:211-224.

18. Wojnar-Horton RE, Kristensen JH, Yapp P, et al. Methadone distribution and excretion into breast milk of clients in a methadone maintenance programme. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:543-547.

19. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:135-141.

20. Sachs HC. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796-809.

21. Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:19.

22. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:488-489.

23. Gopman S. Prenatal and postpartum care of women with substance use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:213-228.

24. Mitchell M, Severtson S, Latimer W. Pregnancy and race/ethnicity as predictors of motivation for drug treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:397-404.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid painkiller prescribing: where you live makes a difference. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2013. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154-63.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug-poisoning deaths. NCHS Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet-drug-poisoning-H.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. Bethesda (MD): NIDA; 2014. www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 28, 2020.

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2011 Contract No.: HHS Publication no. (SMA) 11–4658.

7. Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, et al. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:1158-1165.

8. Whiteman VE, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, et al. Maternal opioid drug use during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal morbidity, mortality, and the costs of medical care in the United States. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:1-8

9. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#trends. Accessed February 4, 2020.

10. Macdorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

11. Texas Health and Human Services. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report, September 2018. www.dshs.texas.gov/legislative/2018-Reports/MMMTFJointReport2018.pdf

12. Virginia Department of Health. Pregnancy-associated deaths from drug overdose in Virginia, 1999-2007: a report from the Virginia Maternal Mortality Review Team. Richmond, VA: VDH; 2015. www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Final-Pregnancy-Associated-Deaths-Due-to-Drug-Overdose.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

13. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Maryland maternal mortality review 2016 annual report. Baltimore: DHMH; 2016. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/Documents/Maryland-Maternal-Mortality-Review-2016-Report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

14. Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:997-1002.

15. Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, et al. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2017;72:703-705.

16. Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35:650-655.

17. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction during pregnancy. In: Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 43. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005:211-224.

18. Wojnar-Horton RE, Kristensen JH, Yapp P, et al. Methadone distribution and excretion into breast milk of clients in a methadone maintenance programme. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:543-547.

19. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:135-141.

20. Sachs HC. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796-809.

21. Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:19.

22. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:488-489.

23. Gopman S. Prenatal and postpartum care of women with substance use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:213-228.

24. Mitchell M, Severtson S, Latimer W. Pregnancy and race/ethnicity as predictors of motivation for drug treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:397-404.

SABCS 2020: What’s hot, including a major chemotherapy trial

That’s the word from Virginia Kaklamani, MD, from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio. Dr. Kaklamani, a professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology, is codirector of the meeting that runs online Dec. 8-11.

If the new trial sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a lot like the TAILORx trial, the results of which were first presented in 2018 and have changed practice in women with early-stage disease and no lymph node involvement.

“This is the lymph-node positive TAILORx. It’s extremely important,” Dr. Kaklamani said in an interview, adding that both trials involved women with hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative disease.

If the RxPONDER trial shows similar outcomes between women randomized to adjuvant endocrine therapy alone versus endocrine therapy plus chemotherapy, then clinicians “can potentially avoid giving chemotherapy to a large number of women who are currently receiving it,” she explained.

Because women with nodal involvement (one to three positive axillary nodes) are at a higher risk of recurrence, RxPONDER may provide needed insight on the management of these types of breast cancers, Dr. Kaklamani suggested.

Both trials have used the 21-tumor gene expression assay (Oncotype Dx) to determine recurrence-risk status.

Dr. Kaklamani also spotlighted the phase 3 CONTESSA trial (abstract GS4-01) in 600+ patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer that is HR positive and HER2 negative and has been previously treated with a taxane.

The trial features an experimental oral taxane, tesetaxel. The primary objective is to compare the efficacy of tesetaxel plus a reduced dose of capecitabine (Xeloda) versus the approved dose of capecitabine alone. Presented data will include progression-free survival results, indicating about a 3-month PFS advantage with tesetaxel, which is taken once every 3 weeks.

“Oral drugs are convenient for patients and, despite limitations, they are, all in all, a revolution in cancer treatment,” noted Dr. Kaklamani, adding that they beneficially eliminate the need for time-consuming infusions and related clinic visits as well as drug ports.

It will be interesting to see what Steven Vogl, MD, a private practitioner in New Yorky, has to say about CONTESSA and the rest of the SABCS.

He is usually a commentator from the meeting floor, whose self-introduction, “Vogl, New York,” is well known to perennial meeting attendees, according to a profile piece published some years ago.

This year the medical oncologist will also serve as the chair of the “View from the Trenches” session, which is devoted to summarizing the meeting’s most important findings for everyday practitioners.

A number of years ago, Dr. Vogl proposed the idea of this where-the-rubber-meets-the-road session to SABCS meeting planners, which they then adopted. This year, Dr. Kaklamani invited Dr. Vogl to run the session and he accepted.

Dr. Vogl is a “really smart guy who is always right on” with his comments and questions, and he will be the first-ever independent, community-based oncologist to chair a meeting session, said Dr. Kaklamani.

Other hot topics

Another hot topic featured at the meeting will be the use of CDK4/6 inhibitors in the adjuvant treatment of HR-positive and HER2-negative disease that has a high risk of recurrence, Dr. Kaklamani said. New data from two trials, monarchE and PENELOPE-B, will be presented.

First, there will be an update from the monarchE trial (abstract GS1-01). The first results from this trial were reported in September at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020. They showed that adding abemaciclib (Verzenio) to endocrine therapy reduced the risk of early recurrence. The positive outcome represented the first treatment improvement in this high-risk setting in more than 20 years, according to experts.

A similar trial, PENELOPE-B (abstract GS1-02), looks at palbociclib (Ibrance) in a somewhat different population – those patients with high relapse risk after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. “These are even higher risk ER+ patients [than those in monarchE], which is why they received chemotherapy before surgery,” commented Dr. Kaklamani.

In triple-negative disease, there will be overall survival (OS) results from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-355 study (abstract GS3-01) of pembrolizumab (Keytruda) versus placebo (plus chemotherapy for all patients) as first-line therapy for locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. “It’s potentially a huge deal,” said Dr. Kaklamani about the OS data, if they are statistically significant.

A meta-analysis (abstract GS4-08) of data on circulating tumor cells (CTCs), which are shed from the primary tumor into the bloodstream, may point to their value as a tool to determine whether or not a breast cancer treatment is effective. “CTCs allow you to assess how a treatment is doing before you do scans, which typically occur 3 months or so later,” explained Dr. Kaklamani.

CTC results can be assessed in 3-4 weeks and allow clinicians to change treatments if CTC volume increases. However, a previous study of CTCs did not show a clinical benefit with the tool among patients treated mainly with chemotherapies. What’s different about the new study, which is from an international group of investigators, is in the treatments patients with metastatic breast cancer received. “This study is from a different era – with targeted therapies,” said Dr. Kaklamani.

In the new study, changes in CTC levels (with a reduction being a good result) between baseline (pretreatment) and follow-up were analyzed to determine whether they were associated with overall survival.

COVID sessions

On the meeting’s first day, SABCS will feature a special session on COVID-19 and breast cancer. The meeting organizers sought to separate the wheat from the chaff in this subject, as much has already been written, published, or presented.

“We received a lot of abstracts on COVID that were studies that were poorly done. We tried to tease through them and select the well-researched ones,” acknowledged Dr. Kaklamani.

The organizers included two patient advocates who have had COVID-19, including during treatment for breast cancer, as participants in the meeting session. The session will also feature global perspectives, with presenters from Brazil, Italy, and the Netherlands.

Plenary lectures

The meeting’s two plenary lectures will focus, respectively, on the increasingly used clinical approach of neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer, and research in the time of a pandemic.

Elizabeth Mittendorf, MD, PhD, a surgical oncologist and director of the Breast lmmuno-Oncology program and co-director of the Breast Cancer Clinical Research Program at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston, will present “Local regional management following neoadjuvant therapy: Minding the knowledge gaps.”

Ned Sharpless, MD, director of the National Cancer Institute, will present “Advancing cancer research during challenging times.”

Dr. Kaklamani disclosed recieving consulting fees with Amgen, Eisai, Puma, Celldex, AstraZeneca, and Athenex; receiving fees for non-CME services received directly from commercial interest or their agents from Pfizer, Celgene, Genentech, Genomic Health, Puma, Eisai, and Novartis; and contracted research with Eisai.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

That’s the word from Virginia Kaklamani, MD, from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio. Dr. Kaklamani, a professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology, is codirector of the meeting that runs online Dec. 8-11.

If the new trial sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a lot like the TAILORx trial, the results of which were first presented in 2018 and have changed practice in women with early-stage disease and no lymph node involvement.

“This is the lymph-node positive TAILORx. It’s extremely important,” Dr. Kaklamani said in an interview, adding that both trials involved women with hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative disease.

If the RxPONDER trial shows similar outcomes between women randomized to adjuvant endocrine therapy alone versus endocrine therapy plus chemotherapy, then clinicians “can potentially avoid giving chemotherapy to a large number of women who are currently receiving it,” she explained.

Because women with nodal involvement (one to three positive axillary nodes) are at a higher risk of recurrence, RxPONDER may provide needed insight on the management of these types of breast cancers, Dr. Kaklamani suggested.

Both trials have used the 21-tumor gene expression assay (Oncotype Dx) to determine recurrence-risk status.

Dr. Kaklamani also spotlighted the phase 3 CONTESSA trial (abstract GS4-01) in 600+ patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer that is HR positive and HER2 negative and has been previously treated with a taxane.

The trial features an experimental oral taxane, tesetaxel. The primary objective is to compare the efficacy of tesetaxel plus a reduced dose of capecitabine (Xeloda) versus the approved dose of capecitabine alone. Presented data will include progression-free survival results, indicating about a 3-month PFS advantage with tesetaxel, which is taken once every 3 weeks.

“Oral drugs are convenient for patients and, despite limitations, they are, all in all, a revolution in cancer treatment,” noted Dr. Kaklamani, adding that they beneficially eliminate the need for time-consuming infusions and related clinic visits as well as drug ports.

It will be interesting to see what Steven Vogl, MD, a private practitioner in New Yorky, has to say about CONTESSA and the rest of the SABCS.

He is usually a commentator from the meeting floor, whose self-introduction, “Vogl, New York,” is well known to perennial meeting attendees, according to a profile piece published some years ago.

This year the medical oncologist will also serve as the chair of the “View from the Trenches” session, which is devoted to summarizing the meeting’s most important findings for everyday practitioners.

A number of years ago, Dr. Vogl proposed the idea of this where-the-rubber-meets-the-road session to SABCS meeting planners, which they then adopted. This year, Dr. Kaklamani invited Dr. Vogl to run the session and he accepted.

Dr. Vogl is a “really smart guy who is always right on” with his comments and questions, and he will be the first-ever independent, community-based oncologist to chair a meeting session, said Dr. Kaklamani.

Other hot topics

Another hot topic featured at the meeting will be the use of CDK4/6 inhibitors in the adjuvant treatment of HR-positive and HER2-negative disease that has a high risk of recurrence, Dr. Kaklamani said. New data from two trials, monarchE and PENELOPE-B, will be presented.

First, there will be an update from the monarchE trial (abstract GS1-01). The first results from this trial were reported in September at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020. They showed that adding abemaciclib (Verzenio) to endocrine therapy reduced the risk of early recurrence. The positive outcome represented the first treatment improvement in this high-risk setting in more than 20 years, according to experts.

A similar trial, PENELOPE-B (abstract GS1-02), looks at palbociclib (Ibrance) in a somewhat different population – those patients with high relapse risk after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. “These are even higher risk ER+ patients [than those in monarchE], which is why they received chemotherapy before surgery,” commented Dr. Kaklamani.

In triple-negative disease, there will be overall survival (OS) results from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-355 study (abstract GS3-01) of pembrolizumab (Keytruda) versus placebo (plus chemotherapy for all patients) as first-line therapy for locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. “It’s potentially a huge deal,” said Dr. Kaklamani about the OS data, if they are statistically significant.

A meta-analysis (abstract GS4-08) of data on circulating tumor cells (CTCs), which are shed from the primary tumor into the bloodstream, may point to their value as a tool to determine whether or not a breast cancer treatment is effective. “CTCs allow you to assess how a treatment is doing before you do scans, which typically occur 3 months or so later,” explained Dr. Kaklamani.

CTC results can be assessed in 3-4 weeks and allow clinicians to change treatments if CTC volume increases. However, a previous study of CTCs did not show a clinical benefit with the tool among patients treated mainly with chemotherapies. What’s different about the new study, which is from an international group of investigators, is in the treatments patients with metastatic breast cancer received. “This study is from a different era – with targeted therapies,” said Dr. Kaklamani.

In the new study, changes in CTC levels (with a reduction being a good result) between baseline (pretreatment) and follow-up were analyzed to determine whether they were associated with overall survival.

COVID sessions

On the meeting’s first day, SABCS will feature a special session on COVID-19 and breast cancer. The meeting organizers sought to separate the wheat from the chaff in this subject, as much has already been written, published, or presented.

“We received a lot of abstracts on COVID that were studies that were poorly done. We tried to tease through them and select the well-researched ones,” acknowledged Dr. Kaklamani.

The organizers included two patient advocates who have had COVID-19, including during treatment for breast cancer, as participants in the meeting session. The session will also feature global perspectives, with presenters from Brazil, Italy, and the Netherlands.

Plenary lectures

The meeting’s two plenary lectures will focus, respectively, on the increasingly used clinical approach of neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer, and research in the time of a pandemic.

Elizabeth Mittendorf, MD, PhD, a surgical oncologist and director of the Breast lmmuno-Oncology program and co-director of the Breast Cancer Clinical Research Program at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston, will present “Local regional management following neoadjuvant therapy: Minding the knowledge gaps.”

Ned Sharpless, MD, director of the National Cancer Institute, will present “Advancing cancer research during challenging times.”

Dr. Kaklamani disclosed recieving consulting fees with Amgen, Eisai, Puma, Celldex, AstraZeneca, and Athenex; receiving fees for non-CME services received directly from commercial interest or their agents from Pfizer, Celgene, Genentech, Genomic Health, Puma, Eisai, and Novartis; and contracted research with Eisai.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

That’s the word from Virginia Kaklamani, MD, from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio. Dr. Kaklamani, a professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology, is codirector of the meeting that runs online Dec. 8-11.

If the new trial sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a lot like the TAILORx trial, the results of which were first presented in 2018 and have changed practice in women with early-stage disease and no lymph node involvement.

“This is the lymph-node positive TAILORx. It’s extremely important,” Dr. Kaklamani said in an interview, adding that both trials involved women with hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative disease.

If the RxPONDER trial shows similar outcomes between women randomized to adjuvant endocrine therapy alone versus endocrine therapy plus chemotherapy, then clinicians “can potentially avoid giving chemotherapy to a large number of women who are currently receiving it,” she explained.

Because women with nodal involvement (one to three positive axillary nodes) are at a higher risk of recurrence, RxPONDER may provide needed insight on the management of these types of breast cancers, Dr. Kaklamani suggested.

Both trials have used the 21-tumor gene expression assay (Oncotype Dx) to determine recurrence-risk status.

Dr. Kaklamani also spotlighted the phase 3 CONTESSA trial (abstract GS4-01) in 600+ patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer that is HR positive and HER2 negative and has been previously treated with a taxane.

The trial features an experimental oral taxane, tesetaxel. The primary objective is to compare the efficacy of tesetaxel plus a reduced dose of capecitabine (Xeloda) versus the approved dose of capecitabine alone. Presented data will include progression-free survival results, indicating about a 3-month PFS advantage with tesetaxel, which is taken once every 3 weeks.

“Oral drugs are convenient for patients and, despite limitations, they are, all in all, a revolution in cancer treatment,” noted Dr. Kaklamani, adding that they beneficially eliminate the need for time-consuming infusions and related clinic visits as well as drug ports.

It will be interesting to see what Steven Vogl, MD, a private practitioner in New Yorky, has to say about CONTESSA and the rest of the SABCS.