User login

Molar pregnancy: The next steps after diagnosis

Molar pregnancy is an uncommon but serious condition that affects young women of reproductive age. The diagnosis and management of molar pregnancy is familiar to most gynecologists. However, in the days and weeks following evacuation of molar pregnancy, clinicians face a critical time period in which they must be vigilant for the development of postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). If recognized early and treated appropriately, it almost always can be cured; however, errors or delays in the management of this condition can have catastrophic consequences for patients, including decreasing the likelihood of cure. Here we will review some of the steps and actions that can be taken immediately following the diagnosis of a molar pregnancy to expeditiously identify postmolar GTN and ensure patients are appropriately prepared for further consultation and intervention.

Postmolar GTN includes the diagnoses of invasive mole and choriocarcinoma that contain highly atypical trophoblasts with the capacity for local invasion and metastasis. Typically, the diagnosis is made clinically and not distinguished with histology. While molar pregnancies are a benign condition, invasive moles and choriocarcinoma are malignant conditions in which the molar tissue infiltrates the uterine myometrium, vasculature, and frequently is associated with hematogenous spread with distant metastases. It is a highly chemosensitive disease, and cure with chemotherapy typically is achieved with the ability to preserve fertility if desired even in advanced stage disease.1

After evacuation of a molar pregnancy, gynecologists should be on alert for the development of postmolar GTN if the following known risk factors are present: a history of a prior GTN diagnosis, complete mole on pathology (as opposed to partial mole), serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels greater than 100,000 mIU/mL, age greater than 40 years, an enlarged uterus or large ovarian theca lutein cysts, and slow to normalize (more than 2 months) hCG. Symptoms for the development of postmolar GTN include persistent vaginal bleeding after evacuation, a persistently enlarged or enlarging uterine size, and adnexal masses. Ultimately, the diagnosis is made through plateaued or rising serum hCG assessments.2 (See graphic.)

Following the evacuation of a molar pregnancy, hCG levels should be drawn at the same laboratory every 1-2 weeks until normalization and then three consecutive normal values. Once this has been achieved, hCG levels should be tested once at 3 months and again at 6 months. During this 6 month period, patients should use reliable contraception, ideally, and through oral contraceptive pills that suppress the secretion of pituitary hCG if not contraindicated. Should a woman become pregnant during this 6-month surveillance, it becomes impossible to rule out occult postmolar GTN.

Typically after evacuation of a molar pregnancy, there is rapid fall in hCG levels, but this does not occur when the molar pregnancy has become invasive or is associated with choriocarcinoma. In these cases, after an initial drop in hCG levels, there is an observed rise or plateau in levels (as defined in the accompanying table), and this establishes the diagnosis of postmolar GTN. It is common for hCG to fall in fits and starts, rather than have a smooth, consistent diminution, and this can be worrying for gynecologists; however, provided there is a consistent reduction in values in accordance with the stated definitions, observation can continue.

Another source of confusion and concern is an HCG level that fails to completely normalize during observation, yet reaches a very low level. If this is observed, clinicians should consider the diagnosis of quiescent hCG, pituitary hCG, or phantom hCG.3 These can be difficult to distinguish from postmolar GTN, and consultation with a gynecologic oncologist with experience in the diagnosis and management of these rare tumors is helpful to determine if the persistent low levels in hCG require intervention.

Once a clinician has observed a plateau or rise in hCG levels, a gynecologic examination should be performed because the lower genital tract is a common site for metastatic postmolar GTN. If during this evaluation, a suspicious lesion is identified (typically a blue-black, slightly raised, hemorrhagic-appearing lesion), it should not be biopsied, but rather assumed to be a metastatic site. The vasculature of metastatic sites is extremely fragile, and biopsy or disruption can result in catastrophic hemorrhage, even from very small lesions.

In addition to physical examination, several diagnostic studies should be performed which may expedite the triage and management of the case. A pelvic ultrasound should evaluate the endometrial cavity for a new viable pregnancy, and residual molar tissue; sometimes, myometrial invasion consistent with an invasive mole can be appreciated. Chest x-ray or CT scan should be ordered to evaluate for pulmonary metastatic lesions. Additionally, CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis should be ordered, and if lung metastases are present, brain imaging with either MRI or CT scan also should be obtained. These imaging studies will provide the necessary information to stage the GTN (as metastatic or not).

Treatment for postmolar GTN is determined based on further prognostic categorization (“high risk” or “low risk”) in accordance with the WHO classification, which is derived using several prognostic clinical variables including age, antecedent pregnancy, interval from index pregnancy, pretreatment hCG, largest tumor size, sites and number of metastases, and response to previous chemotherapy.4 These assignments are necessary to determine whether single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy should be prescribed.

Laboratory studies are helpful to obtain at this time and include metabolic panels (which can ensure that renal and hepatic function are within normal limits in anticipation of future chemotherapy), and complete blood count ,which can establish viable bone marrow function prior to chemotherapy.

Once postmolar GTN has been diagnosed, it is most appropriate to refer the patient to a gynecologic oncologist with experience in the treatment of these relatively rare malignancies. At that point, the patient will be formally staged, and offered treatment based on these staging results.

Among women with low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN who desire future fertility it is appropriate to offer a repeat dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure rather than immediately proceeding with chemotherapy. Approximately two-thirds of women with low risk disease can avoid chemotherapy with repeat curettage.5 Risk factors for needing chemotherapy after repeat D&C include the presence of trophoblastic disease in the pathology specimen and urinary hCG levels greater than 1,500 mIU/mL at the time of curettage. In my experience, many women appreciate this option to potentially avoid toxic chemotherapy.

For women with low-risk, nonmetastatic postmolar GTN who do not desire future fertility, and hope to avoid chemotherapy, hysterectomy also is a reasonable first option. This can be performed via either minimally invasive, laparotomy, or vaginal route. If performing a minimally invasive procedure in the setting of GTN, there should be caution or avoidance of use of a uterine manipulator because the uterine wall typically is soft and prone to perforation, and bleeding can be significant secondary to disruption of the tumor.

If repeat D&C or hysterectomy are adopted instead of chemotherapy, it is important that patients are very closely monitored post operatively to ensure normalization of their hCG levels (as described above). If it fails to normalize, restaging scans and examinations should be performed, and referral for the appropriate chemotherapy regimen should be initiated without delay.

Postmolar GTN is a serious condition that usually can be cured with chemotherapy or, if appropriate, surgery. and refer to a gynecologic oncologist when criteria are met to ensure that overtreatment is avoided and essential therapy is ensured.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Lancet Oncol. 2007 Aug;8(8):715-24.

2. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019 Nov 1;17(11):1374-91.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Mar;112(3):663-72.

4. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1983;692:7-81.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):535-42.

Molar pregnancy is an uncommon but serious condition that affects young women of reproductive age. The diagnosis and management of molar pregnancy is familiar to most gynecologists. However, in the days and weeks following evacuation of molar pregnancy, clinicians face a critical time period in which they must be vigilant for the development of postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). If recognized early and treated appropriately, it almost always can be cured; however, errors or delays in the management of this condition can have catastrophic consequences for patients, including decreasing the likelihood of cure. Here we will review some of the steps and actions that can be taken immediately following the diagnosis of a molar pregnancy to expeditiously identify postmolar GTN and ensure patients are appropriately prepared for further consultation and intervention.

Postmolar GTN includes the diagnoses of invasive mole and choriocarcinoma that contain highly atypical trophoblasts with the capacity for local invasion and metastasis. Typically, the diagnosis is made clinically and not distinguished with histology. While molar pregnancies are a benign condition, invasive moles and choriocarcinoma are malignant conditions in which the molar tissue infiltrates the uterine myometrium, vasculature, and frequently is associated with hematogenous spread with distant metastases. It is a highly chemosensitive disease, and cure with chemotherapy typically is achieved with the ability to preserve fertility if desired even in advanced stage disease.1

After evacuation of a molar pregnancy, gynecologists should be on alert for the development of postmolar GTN if the following known risk factors are present: a history of a prior GTN diagnosis, complete mole on pathology (as opposed to partial mole), serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels greater than 100,000 mIU/mL, age greater than 40 years, an enlarged uterus or large ovarian theca lutein cysts, and slow to normalize (more than 2 months) hCG. Symptoms for the development of postmolar GTN include persistent vaginal bleeding after evacuation, a persistently enlarged or enlarging uterine size, and adnexal masses. Ultimately, the diagnosis is made through plateaued or rising serum hCG assessments.2 (See graphic.)

Following the evacuation of a molar pregnancy, hCG levels should be drawn at the same laboratory every 1-2 weeks until normalization and then three consecutive normal values. Once this has been achieved, hCG levels should be tested once at 3 months and again at 6 months. During this 6 month period, patients should use reliable contraception, ideally, and through oral contraceptive pills that suppress the secretion of pituitary hCG if not contraindicated. Should a woman become pregnant during this 6-month surveillance, it becomes impossible to rule out occult postmolar GTN.

Typically after evacuation of a molar pregnancy, there is rapid fall in hCG levels, but this does not occur when the molar pregnancy has become invasive or is associated with choriocarcinoma. In these cases, after an initial drop in hCG levels, there is an observed rise or plateau in levels (as defined in the accompanying table), and this establishes the diagnosis of postmolar GTN. It is common for hCG to fall in fits and starts, rather than have a smooth, consistent diminution, and this can be worrying for gynecologists; however, provided there is a consistent reduction in values in accordance with the stated definitions, observation can continue.

Another source of confusion and concern is an HCG level that fails to completely normalize during observation, yet reaches a very low level. If this is observed, clinicians should consider the diagnosis of quiescent hCG, pituitary hCG, or phantom hCG.3 These can be difficult to distinguish from postmolar GTN, and consultation with a gynecologic oncologist with experience in the diagnosis and management of these rare tumors is helpful to determine if the persistent low levels in hCG require intervention.

Once a clinician has observed a plateau or rise in hCG levels, a gynecologic examination should be performed because the lower genital tract is a common site for metastatic postmolar GTN. If during this evaluation, a suspicious lesion is identified (typically a blue-black, slightly raised, hemorrhagic-appearing lesion), it should not be biopsied, but rather assumed to be a metastatic site. The vasculature of metastatic sites is extremely fragile, and biopsy or disruption can result in catastrophic hemorrhage, even from very small lesions.

In addition to physical examination, several diagnostic studies should be performed which may expedite the triage and management of the case. A pelvic ultrasound should evaluate the endometrial cavity for a new viable pregnancy, and residual molar tissue; sometimes, myometrial invasion consistent with an invasive mole can be appreciated. Chest x-ray or CT scan should be ordered to evaluate for pulmonary metastatic lesions. Additionally, CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis should be ordered, and if lung metastases are present, brain imaging with either MRI or CT scan also should be obtained. These imaging studies will provide the necessary information to stage the GTN (as metastatic or not).

Treatment for postmolar GTN is determined based on further prognostic categorization (“high risk” or “low risk”) in accordance with the WHO classification, which is derived using several prognostic clinical variables including age, antecedent pregnancy, interval from index pregnancy, pretreatment hCG, largest tumor size, sites and number of metastases, and response to previous chemotherapy.4 These assignments are necessary to determine whether single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy should be prescribed.

Laboratory studies are helpful to obtain at this time and include metabolic panels (which can ensure that renal and hepatic function are within normal limits in anticipation of future chemotherapy), and complete blood count ,which can establish viable bone marrow function prior to chemotherapy.

Once postmolar GTN has been diagnosed, it is most appropriate to refer the patient to a gynecologic oncologist with experience in the treatment of these relatively rare malignancies. At that point, the patient will be formally staged, and offered treatment based on these staging results.

Among women with low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN who desire future fertility it is appropriate to offer a repeat dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure rather than immediately proceeding with chemotherapy. Approximately two-thirds of women with low risk disease can avoid chemotherapy with repeat curettage.5 Risk factors for needing chemotherapy after repeat D&C include the presence of trophoblastic disease in the pathology specimen and urinary hCG levels greater than 1,500 mIU/mL at the time of curettage. In my experience, many women appreciate this option to potentially avoid toxic chemotherapy.

For women with low-risk, nonmetastatic postmolar GTN who do not desire future fertility, and hope to avoid chemotherapy, hysterectomy also is a reasonable first option. This can be performed via either minimally invasive, laparotomy, or vaginal route. If performing a minimally invasive procedure in the setting of GTN, there should be caution or avoidance of use of a uterine manipulator because the uterine wall typically is soft and prone to perforation, and bleeding can be significant secondary to disruption of the tumor.

If repeat D&C or hysterectomy are adopted instead of chemotherapy, it is important that patients are very closely monitored post operatively to ensure normalization of their hCG levels (as described above). If it fails to normalize, restaging scans and examinations should be performed, and referral for the appropriate chemotherapy regimen should be initiated without delay.

Postmolar GTN is a serious condition that usually can be cured with chemotherapy or, if appropriate, surgery. and refer to a gynecologic oncologist when criteria are met to ensure that overtreatment is avoided and essential therapy is ensured.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Lancet Oncol. 2007 Aug;8(8):715-24.

2. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019 Nov 1;17(11):1374-91.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Mar;112(3):663-72.

4. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1983;692:7-81.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):535-42.

Molar pregnancy is an uncommon but serious condition that affects young women of reproductive age. The diagnosis and management of molar pregnancy is familiar to most gynecologists. However, in the days and weeks following evacuation of molar pregnancy, clinicians face a critical time period in which they must be vigilant for the development of postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). If recognized early and treated appropriately, it almost always can be cured; however, errors or delays in the management of this condition can have catastrophic consequences for patients, including decreasing the likelihood of cure. Here we will review some of the steps and actions that can be taken immediately following the diagnosis of a molar pregnancy to expeditiously identify postmolar GTN and ensure patients are appropriately prepared for further consultation and intervention.

Postmolar GTN includes the diagnoses of invasive mole and choriocarcinoma that contain highly atypical trophoblasts with the capacity for local invasion and metastasis. Typically, the diagnosis is made clinically and not distinguished with histology. While molar pregnancies are a benign condition, invasive moles and choriocarcinoma are malignant conditions in which the molar tissue infiltrates the uterine myometrium, vasculature, and frequently is associated with hematogenous spread with distant metastases. It is a highly chemosensitive disease, and cure with chemotherapy typically is achieved with the ability to preserve fertility if desired even in advanced stage disease.1

After evacuation of a molar pregnancy, gynecologists should be on alert for the development of postmolar GTN if the following known risk factors are present: a history of a prior GTN diagnosis, complete mole on pathology (as opposed to partial mole), serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels greater than 100,000 mIU/mL, age greater than 40 years, an enlarged uterus or large ovarian theca lutein cysts, and slow to normalize (more than 2 months) hCG. Symptoms for the development of postmolar GTN include persistent vaginal bleeding after evacuation, a persistently enlarged or enlarging uterine size, and adnexal masses. Ultimately, the diagnosis is made through plateaued or rising serum hCG assessments.2 (See graphic.)

Following the evacuation of a molar pregnancy, hCG levels should be drawn at the same laboratory every 1-2 weeks until normalization and then three consecutive normal values. Once this has been achieved, hCG levels should be tested once at 3 months and again at 6 months. During this 6 month period, patients should use reliable contraception, ideally, and through oral contraceptive pills that suppress the secretion of pituitary hCG if not contraindicated. Should a woman become pregnant during this 6-month surveillance, it becomes impossible to rule out occult postmolar GTN.

Typically after evacuation of a molar pregnancy, there is rapid fall in hCG levels, but this does not occur when the molar pregnancy has become invasive or is associated with choriocarcinoma. In these cases, after an initial drop in hCG levels, there is an observed rise or plateau in levels (as defined in the accompanying table), and this establishes the diagnosis of postmolar GTN. It is common for hCG to fall in fits and starts, rather than have a smooth, consistent diminution, and this can be worrying for gynecologists; however, provided there is a consistent reduction in values in accordance with the stated definitions, observation can continue.

Another source of confusion and concern is an HCG level that fails to completely normalize during observation, yet reaches a very low level. If this is observed, clinicians should consider the diagnosis of quiescent hCG, pituitary hCG, or phantom hCG.3 These can be difficult to distinguish from postmolar GTN, and consultation with a gynecologic oncologist with experience in the diagnosis and management of these rare tumors is helpful to determine if the persistent low levels in hCG require intervention.

Once a clinician has observed a plateau or rise in hCG levels, a gynecologic examination should be performed because the lower genital tract is a common site for metastatic postmolar GTN. If during this evaluation, a suspicious lesion is identified (typically a blue-black, slightly raised, hemorrhagic-appearing lesion), it should not be biopsied, but rather assumed to be a metastatic site. The vasculature of metastatic sites is extremely fragile, and biopsy or disruption can result in catastrophic hemorrhage, even from very small lesions.

In addition to physical examination, several diagnostic studies should be performed which may expedite the triage and management of the case. A pelvic ultrasound should evaluate the endometrial cavity for a new viable pregnancy, and residual molar tissue; sometimes, myometrial invasion consistent with an invasive mole can be appreciated. Chest x-ray or CT scan should be ordered to evaluate for pulmonary metastatic lesions. Additionally, CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis should be ordered, and if lung metastases are present, brain imaging with either MRI or CT scan also should be obtained. These imaging studies will provide the necessary information to stage the GTN (as metastatic or not).

Treatment for postmolar GTN is determined based on further prognostic categorization (“high risk” or “low risk”) in accordance with the WHO classification, which is derived using several prognostic clinical variables including age, antecedent pregnancy, interval from index pregnancy, pretreatment hCG, largest tumor size, sites and number of metastases, and response to previous chemotherapy.4 These assignments are necessary to determine whether single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy should be prescribed.

Laboratory studies are helpful to obtain at this time and include metabolic panels (which can ensure that renal and hepatic function are within normal limits in anticipation of future chemotherapy), and complete blood count ,which can establish viable bone marrow function prior to chemotherapy.

Once postmolar GTN has been diagnosed, it is most appropriate to refer the patient to a gynecologic oncologist with experience in the treatment of these relatively rare malignancies. At that point, the patient will be formally staged, and offered treatment based on these staging results.

Among women with low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN who desire future fertility it is appropriate to offer a repeat dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure rather than immediately proceeding with chemotherapy. Approximately two-thirds of women with low risk disease can avoid chemotherapy with repeat curettage.5 Risk factors for needing chemotherapy after repeat D&C include the presence of trophoblastic disease in the pathology specimen and urinary hCG levels greater than 1,500 mIU/mL at the time of curettage. In my experience, many women appreciate this option to potentially avoid toxic chemotherapy.

For women with low-risk, nonmetastatic postmolar GTN who do not desire future fertility, and hope to avoid chemotherapy, hysterectomy also is a reasonable first option. This can be performed via either minimally invasive, laparotomy, or vaginal route. If performing a minimally invasive procedure in the setting of GTN, there should be caution or avoidance of use of a uterine manipulator because the uterine wall typically is soft and prone to perforation, and bleeding can be significant secondary to disruption of the tumor.

If repeat D&C or hysterectomy are adopted instead of chemotherapy, it is important that patients are very closely monitored post operatively to ensure normalization of their hCG levels (as described above). If it fails to normalize, restaging scans and examinations should be performed, and referral for the appropriate chemotherapy regimen should be initiated without delay.

Postmolar GTN is a serious condition that usually can be cured with chemotherapy or, if appropriate, surgery. and refer to a gynecologic oncologist when criteria are met to ensure that overtreatment is avoided and essential therapy is ensured.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Lancet Oncol. 2007 Aug;8(8):715-24.

2. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019 Nov 1;17(11):1374-91.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Mar;112(3):663-72.

4. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1983;692:7-81.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):535-42.

Modafinil use in pregnancy tied to congenital malformations

Modafinil exposure during pregnancy was associated with an approximately tripled risk of congenital malformations in a large Danish registry-based study.

Modafinil (Provigil) is commonly prescribed to address daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy and multiple sclerosis. An interim postmarketing safety analysis showed increased rates of major malformation in modafinil-exposed pregnancies, so the manufacturer issued an alert advising health care professionals of this safety signal in June 2019, wrote Per Damkier, MD, PhD, corresponding author of a JAMA research letter reporting the Danish study results. The postmarketing study had shown a major malformation rate of about 15% in modafinil-exposed pregnancies, much higher than the 3% background rate.

Dr. Damkier and Anne Broe, MD, PhD, both of the department of clinical biochemistry and pharmacology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, compared outcomes for pregnant women who were prescribed modafinil at any point during the first trimester of pregnancy with those who were prescribed an active comparator, methylphenidate, as well as with those who had neither exposure. Methylphenidate is not associated with congenital malformations and is used for indications similar to modafinil.

Looking at all pregnancies for whom complete records existed in Danish health registries between 2004 and 2017, the investigators found 49 modafinil-exposed pregnancies, 963 methylphenidate-exposed pregnancies, and 828,644 pregnancies with neither exposure.

Six major congenital malformations occurred in the modafinil-exposed group for an absolute risk of 12%. Major malformations occurred in 43 (4.5%) of the methylphenidate-exposed group and 32,466 (3.9%) of the unexposed group.

Using the extensive data available in public registries, the authors were able to perform logistic regression to adjust for concomitant use of other psychotropic medication; comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension; and demographic and anthropometric measures such as maternal age, smoking status, and body mass index.

After this statistical adjustment, the researchers found that modafinil exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with an odds ratio of 3.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-9.7) for major congenital malformation, compared with first-trimester methylphenidate exposure. Compared with the unexposed cohort, modafinil-exposed pregnancies had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.7 (95% CI, 1.1-6.9) for major congenital malformation.

A total of 13 (27%) women who took modafinil had multiple sclerosis, but the authors excluded women who’d received a prescription for the multiple sclerosis drug teriflunomide (Aubagio), a known teratogen. Sleep disorders were reported for 39% of modafinil users, compared with 4.5% of methylphenidate users. Rates of psychoactive drug use were 41% for the modafinil group and 30% for the methylphenidate group.

The authors acknowledged the possibility of residual confounders affecting their results, and of the statistical problems with the very small sample size of modafinil-exposed pregnancies. Also, actual medication use – rather than prescription redemption – wasn’t captured in the study.

The study was partially funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Damkier P, Broe A. JAMA. 2020;323(4):374-6.

Modafinil exposure during pregnancy was associated with an approximately tripled risk of congenital malformations in a large Danish registry-based study.

Modafinil (Provigil) is commonly prescribed to address daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy and multiple sclerosis. An interim postmarketing safety analysis showed increased rates of major malformation in modafinil-exposed pregnancies, so the manufacturer issued an alert advising health care professionals of this safety signal in June 2019, wrote Per Damkier, MD, PhD, corresponding author of a JAMA research letter reporting the Danish study results. The postmarketing study had shown a major malformation rate of about 15% in modafinil-exposed pregnancies, much higher than the 3% background rate.

Dr. Damkier and Anne Broe, MD, PhD, both of the department of clinical biochemistry and pharmacology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, compared outcomes for pregnant women who were prescribed modafinil at any point during the first trimester of pregnancy with those who were prescribed an active comparator, methylphenidate, as well as with those who had neither exposure. Methylphenidate is not associated with congenital malformations and is used for indications similar to modafinil.

Looking at all pregnancies for whom complete records existed in Danish health registries between 2004 and 2017, the investigators found 49 modafinil-exposed pregnancies, 963 methylphenidate-exposed pregnancies, and 828,644 pregnancies with neither exposure.

Six major congenital malformations occurred in the modafinil-exposed group for an absolute risk of 12%. Major malformations occurred in 43 (4.5%) of the methylphenidate-exposed group and 32,466 (3.9%) of the unexposed group.

Using the extensive data available in public registries, the authors were able to perform logistic regression to adjust for concomitant use of other psychotropic medication; comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension; and demographic and anthropometric measures such as maternal age, smoking status, and body mass index.

After this statistical adjustment, the researchers found that modafinil exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with an odds ratio of 3.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-9.7) for major congenital malformation, compared with first-trimester methylphenidate exposure. Compared with the unexposed cohort, modafinil-exposed pregnancies had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.7 (95% CI, 1.1-6.9) for major congenital malformation.

A total of 13 (27%) women who took modafinil had multiple sclerosis, but the authors excluded women who’d received a prescription for the multiple sclerosis drug teriflunomide (Aubagio), a known teratogen. Sleep disorders were reported for 39% of modafinil users, compared with 4.5% of methylphenidate users. Rates of psychoactive drug use were 41% for the modafinil group and 30% for the methylphenidate group.

The authors acknowledged the possibility of residual confounders affecting their results, and of the statistical problems with the very small sample size of modafinil-exposed pregnancies. Also, actual medication use – rather than prescription redemption – wasn’t captured in the study.

The study was partially funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Damkier P, Broe A. JAMA. 2020;323(4):374-6.

Modafinil exposure during pregnancy was associated with an approximately tripled risk of congenital malformations in a large Danish registry-based study.

Modafinil (Provigil) is commonly prescribed to address daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy and multiple sclerosis. An interim postmarketing safety analysis showed increased rates of major malformation in modafinil-exposed pregnancies, so the manufacturer issued an alert advising health care professionals of this safety signal in June 2019, wrote Per Damkier, MD, PhD, corresponding author of a JAMA research letter reporting the Danish study results. The postmarketing study had shown a major malformation rate of about 15% in modafinil-exposed pregnancies, much higher than the 3% background rate.

Dr. Damkier and Anne Broe, MD, PhD, both of the department of clinical biochemistry and pharmacology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, compared outcomes for pregnant women who were prescribed modafinil at any point during the first trimester of pregnancy with those who were prescribed an active comparator, methylphenidate, as well as with those who had neither exposure. Methylphenidate is not associated with congenital malformations and is used for indications similar to modafinil.

Looking at all pregnancies for whom complete records existed in Danish health registries between 2004 and 2017, the investigators found 49 modafinil-exposed pregnancies, 963 methylphenidate-exposed pregnancies, and 828,644 pregnancies with neither exposure.

Six major congenital malformations occurred in the modafinil-exposed group for an absolute risk of 12%. Major malformations occurred in 43 (4.5%) of the methylphenidate-exposed group and 32,466 (3.9%) of the unexposed group.

Using the extensive data available in public registries, the authors were able to perform logistic regression to adjust for concomitant use of other psychotropic medication; comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension; and demographic and anthropometric measures such as maternal age, smoking status, and body mass index.

After this statistical adjustment, the researchers found that modafinil exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with an odds ratio of 3.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-9.7) for major congenital malformation, compared with first-trimester methylphenidate exposure. Compared with the unexposed cohort, modafinil-exposed pregnancies had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.7 (95% CI, 1.1-6.9) for major congenital malformation.

A total of 13 (27%) women who took modafinil had multiple sclerosis, but the authors excluded women who’d received a prescription for the multiple sclerosis drug teriflunomide (Aubagio), a known teratogen. Sleep disorders were reported for 39% of modafinil users, compared with 4.5% of methylphenidate users. Rates of psychoactive drug use were 41% for the modafinil group and 30% for the methylphenidate group.

The authors acknowledged the possibility of residual confounders affecting their results, and of the statistical problems with the very small sample size of modafinil-exposed pregnancies. Also, actual medication use – rather than prescription redemption – wasn’t captured in the study.

The study was partially funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Damkier P, Broe A. JAMA. 2020;323(4):374-6.

FROM JAMA

Evidence-based tools for premenstrual disorders

CASE

A 30-year-old G2P2 woman presents for a well-woman visit and reports 6 months of premenstrual symptoms including irritability, depression, breast pain, and headaches. She is not taking any medications or hormonal contraceptives. She is sexually active and currently not interested in becoming pregnant. She asks what you can do for her symptoms, as they are affecting her life at home and at work.

Symptoms and definitions vary

Although more than 150 premenstrual symptoms have been reported, the most common psychological and behavioral ones are mood swings, depression, anxiety, irritability, crying, social withdrawal, forgetfulness, and problems concentrating.1-3 The most common physical symptoms are fatigue, abdominal bloating, weight gain, breast tenderness, acne, change in appetite or food cravings, edema, headache, and gastrointestinal upset. The etiology of these symptoms is usually multifactorial, with some combination of hormonal, neurotransmitter, lifestyle, environmental, and psychosocial factors playing a role.

Premenstrual disorder. In reviewing diagnostic criteria for the various premenstrual syndromes and disorders from different organizations (eg, the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders; the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition), there is agreement on the following criteria for premenstrual syndrome (PMS)4-6:

- The woman must be ovulating. (Women who no longer menstruate [eg, because of hysterectomy or endometrial ablation] can have premenstrual disorders as long as ovarian function remains intact.)

- The woman experiences a constellation of disabling physical and/or psychological symptoms that appears in the luteal phase of her menstrual cycle.

- The symptoms improve soon after the onset of menses.

- There is a symptom-free interval before ovulation.

- There is prospective documentation of symptoms for at least 2 consecutive cycles.

- The symptoms are sufficient in severity to affect activities of daily living and/or important relationships.

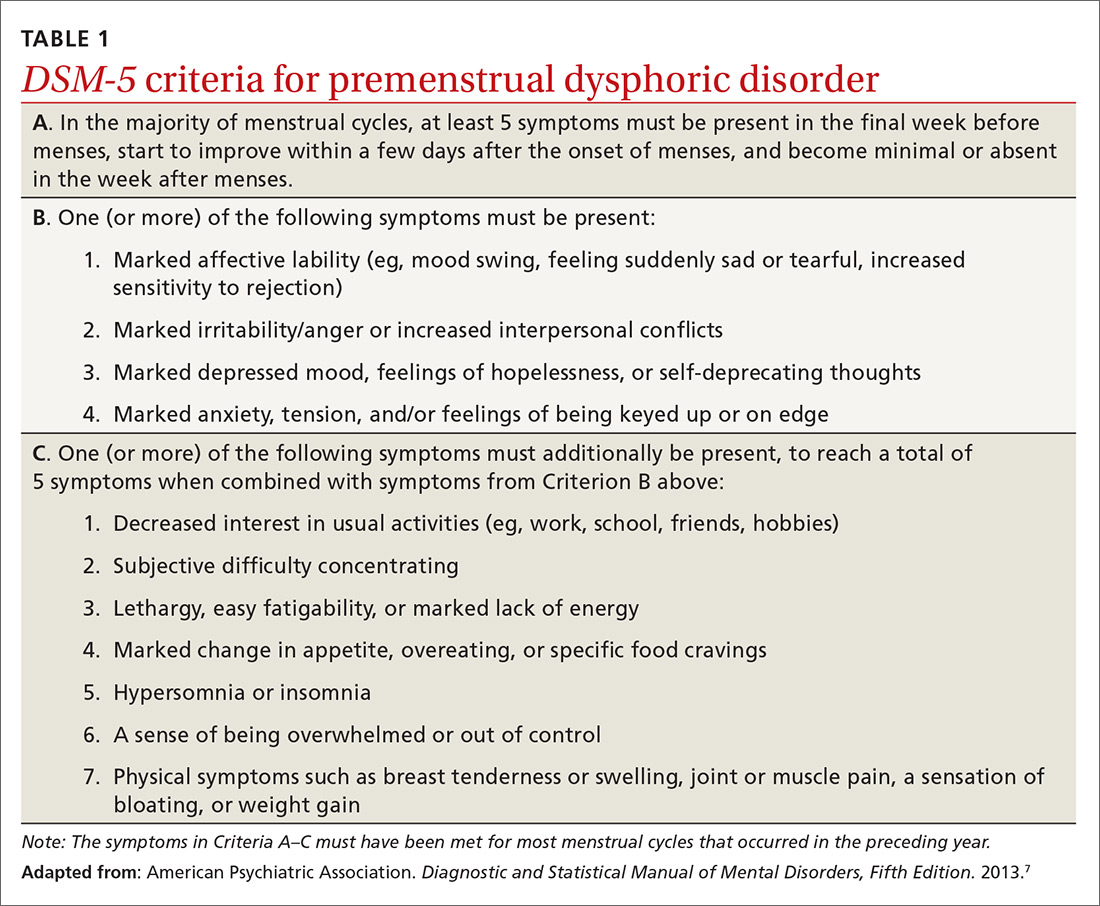

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. PMDD is another common premenstrual disorder. It is distinguished by significant premenstrual psychological symptoms and requires the presence of marked affective lability, marked irritability or anger, markedly depressed mood, and/or marked anxiety (TABLE 1).7

Exacerbation of other ailments. Another premenstrual disorder is the premenstrual exacerbation of underlying chronic medical or psychological problems such as migraines, seizures, asthma, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, anxiety, or depression.

Differences in interpretation lead to variations in prevalence

Differences in the interpretation of significant premenstrual symptoms have led to variations in estimated prevalence. For example, 80% to 95% of women report premenstrual symptoms, but only 30% to 40% meet criteria for PMS and only 3% to 8% meet criteria for PMDD.8 Many women who report premenstrual symptoms in a retrospective questionnaire do not meet criteria for PMS or PMDD based on prospective symptom charting. The Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP), a prospective tracking tool for premenstrual symptoms, is sensitive and specific for diagnosing PMS and PMDD if administered on the first day of menstruation.9

Ask about symptoms and use a tracking tool

When you see a woman for a well-woman visit or a gynecologic problem, inquire about physical/emotional symptoms and their severity during the week that precedes menstruation. If a patient reports few symptoms of a mild nature, then no further work-up is needed.

Continue to: If patients report significant...

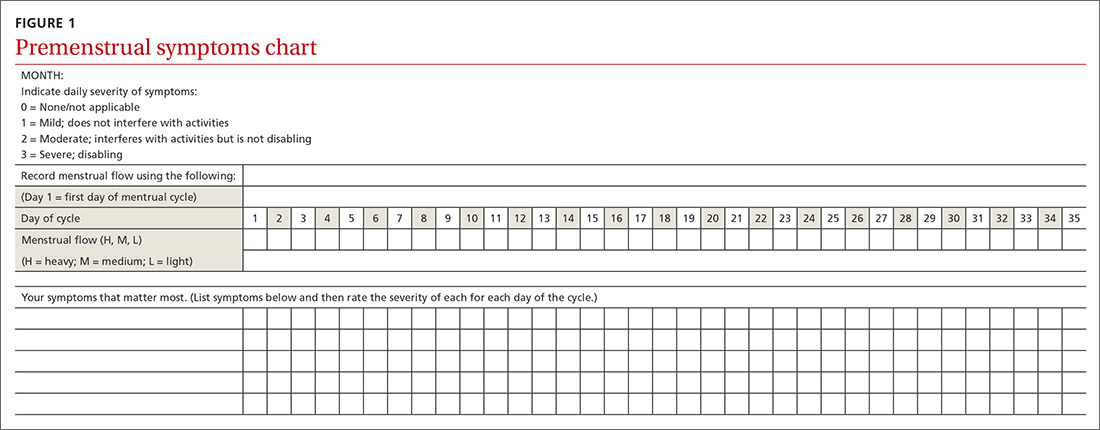

If patients report significant premenstrual symptoms, recommend the use of a tool to track the symptoms. Older tools such as the DRSP and the Premenstrual Symptoms Screening Tool (PSST), newer symptom diaries that can be used for both PMS and PMDD,and questionnaires that have been used in research situations can be time consuming and difficult for patients to complete.10-12 Instead, physicians can easily construct their own charting tool, as we did for patients to use when tracking their most bothersome symptoms (FIGURE 1). Tracking helps to confirm the diagnosis and helps you and the patient focus on treatment goals.

Keep in mind other diagnoses (eg, anemia, thyroid disorders, perimenopause, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance abuse) that can cause or exacerbate the psychological/physical symptoms the patient is reporting. If you suspect any of these other diagnoses, laboratory evaluation (eg, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone level or other hormonal testing, urine drug screen, etc) may be warranted to rule out other etiologies for the reported symptoms.

Develop a Tx plan that considers symptoms, family-planning needs

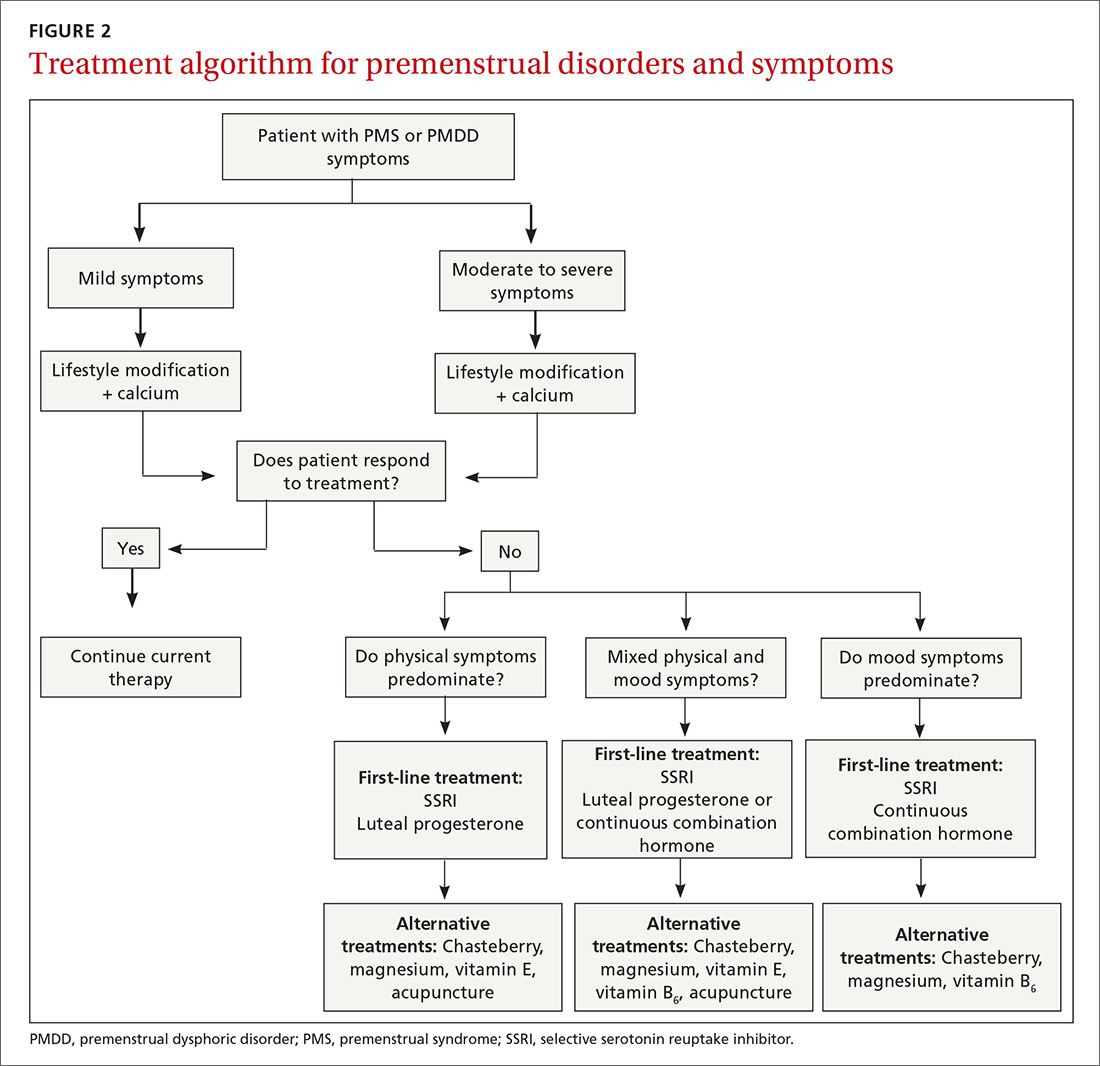

Focus treatment on the patient’s predominant symptoms whether they are physical, psychological, or mixed (FIGURE 2). The patient’s preferences regarding family planning are another important consideration. Women who are using a fertility awareness

Although the definitions for PMS and PMDD require at least 2 cycles of prospective documentation of symptoms, dietary and lifestyle changes can begin immediately. Regular follow-up to document improvement of symptoms is important; using the patient’s symptoms charting tool can help with this.

Focus on diet and lifestyle right away

Experts in the field of PMS/PMDD suggest that simple dietary changes may be a reasonable first step to help improve symptoms. Researchers have found that diets high in fiber, vegetables, and whole grains are inversely related to PMS.13 Older studies have suggested an increased prevalence and severity of PMS with increased caffeine intake; however, a newer study found no such association.14

Continue to: A case-control study nested...

A case-control study nested within the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort showed that a high intake of both dietary calcium and vitamin D prevented the development of PMS in women ages 27 to 44.15 B vitamins, such as thiamine and riboflavin, from food sources have been associated with a lower risk of PMS.16 A variety of older clinical studies showed benefit from aerobic exercise on PMS symptoms,17-19 but a newer cross-sectional study of young adult women found no association between physical activity and the prevalence of PMS.20 Acupuncture has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of the physical symptoms of PMS and PMDD, but more rigorous studies are needed.21,22 Cognitive behavioral therapy has been studied as a treatment, but data to support this approach are limited so it cannot be recommended at this time.23

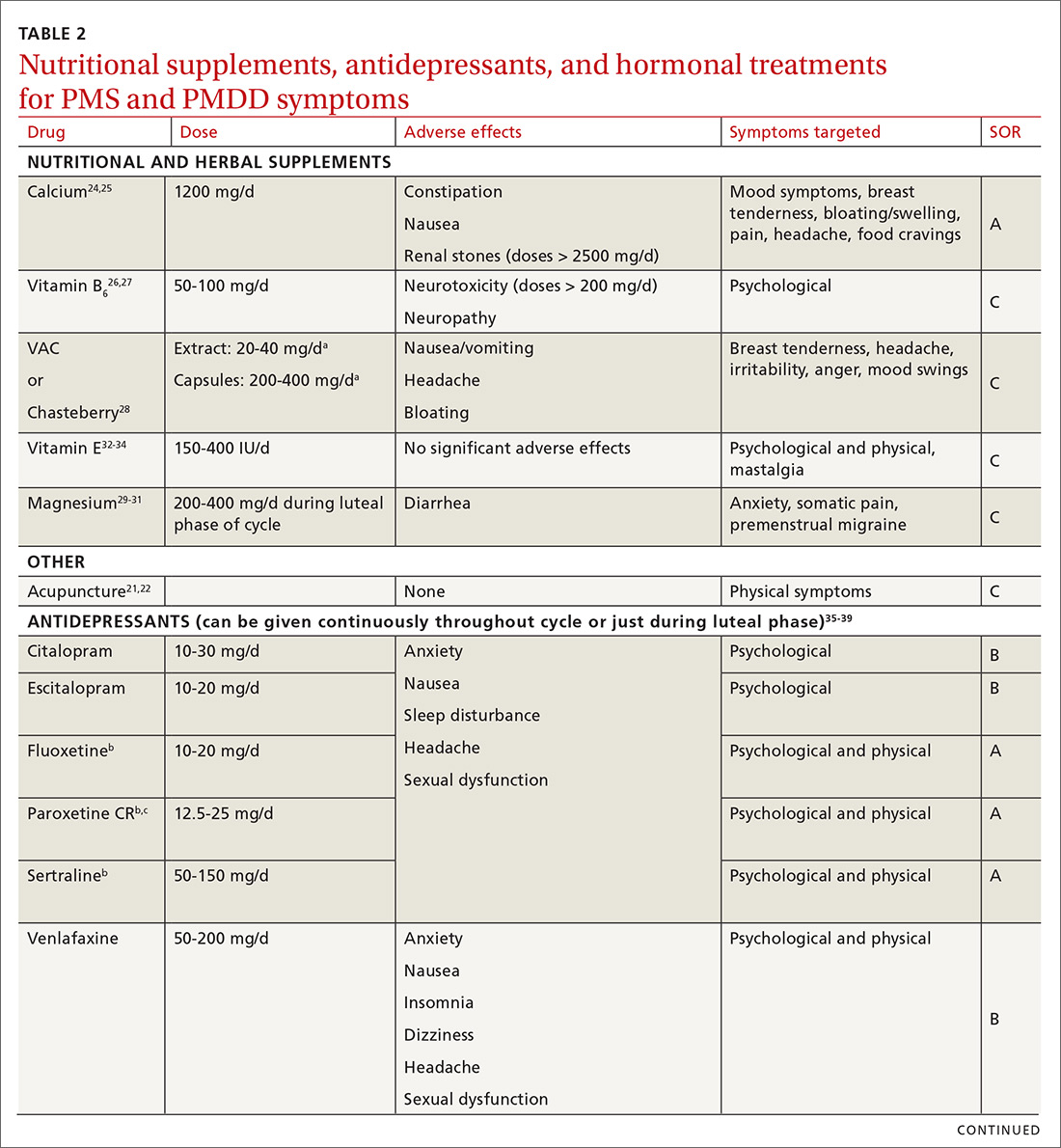

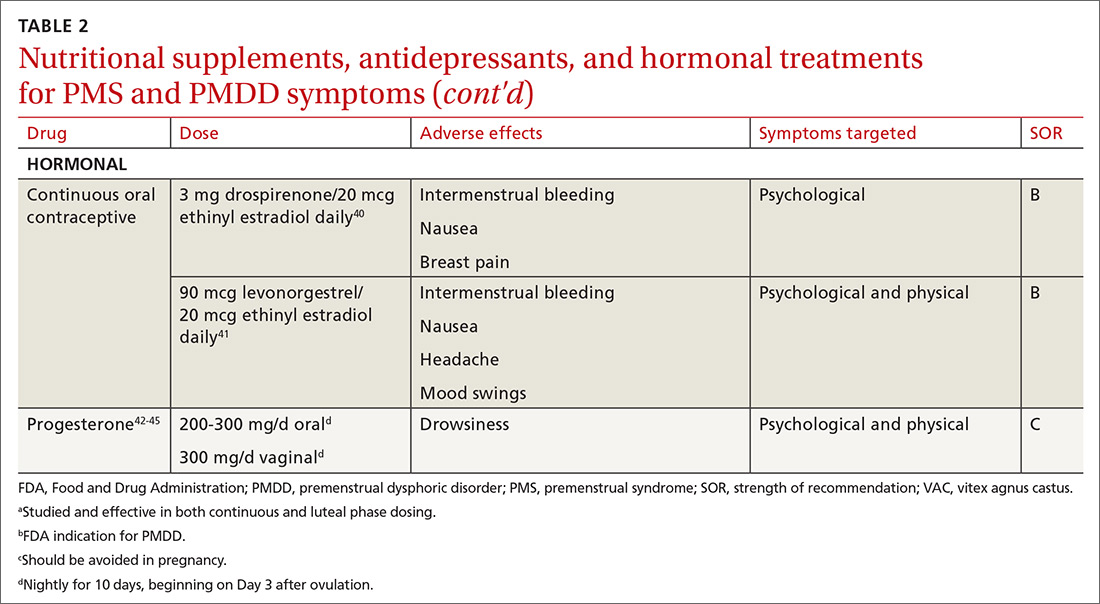

Make the most of supplements—especially calcium

Calcium is the nutritional supplement with the most evidence to support its use to relieve symptoms of PMS and PMDD (TABLE 221,22,24-45). Research indicates that disturbances in calcium regulation and calcium deficiency may be responsible for various premenstrual symptoms. One study showed that, compared with placebo, women who took 1200 mg/d calcium carbonate for 3 menstrual cycles had a 48% decrease in both somatic and affective symptoms.24 Another trial demonstrated improvement in PMS symptoms of early tiredness, appetite changes, and depression with calcium therapy.25

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) has potential benefit in treating PMS due to its ability to increase levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, and taurine.26 An older systematic review showed benefit for symptoms associated with PMS, but the authors concluded that larger randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were needed before definitive recommendations could be made.27

Chasteberry. A number of studies have evaluated the effect of vitex agnus castus (VAC), commonly referred to as chasteberry, on PMS and PMDD symptoms. The exact mechanism of VAC is unknown, but in vitro studies show binding of VAC extracts to dopamine-2 receptors and opioid receptors, and an affinity for estrogen receptors.28

A recent meta-analysis concluded that VAC extracts are not superior to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or oral contraceptives (OCs) for PMS/PMDD.28 The authors suggested a possible benefit of VAC compared with placebo or other nutritional supplements; however, the studies supporting its use are limited by small sample size and potential bias.

Continue to: Magnesium

Magnesium. Many small studies have evaluated the role of other herbal and nutritional supplements for the treatment of PMS/PMDD. A systematic review of studies on the effect of magnesium supplementation on anxiety and stress showed that magnesium may have a potential role in the treatment of the premenstrual symptom of anxiety.29 Other studies have demonstrated a potential role in the treatment of premenstrual migraine.30,31

Vitamin E has demonstrated benefit in the treatment of cyclic mastalgia; however, evidence for using vitamin E for mood and depressive symptoms associated with PMS and PMDD is inconsistent.32-34 Other studies involving vitamin D, St. John’s wort, black cohosh, evening primrose oil, saffron, and ginkgo biloba either showed these agents to be nonefficacious in relieving PMS/PMDD symptoms or to require more data before they can be recommended for use.34,46

Patient doesn’t respond? Start an SSRI

Pharmacotherapy with antidepressants is typically reserved for those who do not respond to nonpharmacologic therapies and are experiencing more moderate to severe symptoms of PMS or PMDD. Reduced levels of serotonin and serotonergic activity in the brain may be linked to symptoms of PMS and PMDD.47 Studies have shown SSRIs to be effective in reducing many psychological symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, lethargy, irritability) and some physical symptoms (eg, headache, breast tenderness, muscle or joint pain) associated with PMS and PMDD.

A Cochrane review of 31 RCTs compared various SSRIs to placebo. When taken either continuously or intermittently (administration during luteal phase), SSRIs were similarly effective in relieving symptoms when compared with placebo.35 Psychological symptoms are more likely to improve with both low and moderate doses of SSRIs, while physical symptoms may only improve with moderate or higher doses. A direct comparison of the various SSRIs for the treatment of PMS or PMDD is lacking; therefore, the selection of SSRI may be based on patient characteristics and preference.

The benefits of SSRIs are noted much earlier in the treatment of PMS/PMDD than they are observed in their use for depression or anxiety.36 This suggests that the mechanism by which SSRIs relieve PMS/PMDD symptoms is different than that for depression or anxiety. Intermittent dosing capitalizes upon the rapid effect seen with these medications and the cyclical nature of these disorders. In most studies, the benefit of intermittent dosing is similar to continuous dosing; however, one meta-analysis did note that continuous dosing had a larger effect.37

Continue to: The doses of SSRIs...

The doses of SSRIs used in most PMS/PMDD trials were lower than those typically used for the treatment of depression and anxiety. The withdrawal effect that can be seen with abrupt cessation of SSRIs has not been reported in the intermittent-dosing studies for PMS/PMDD.38 While this might imply a more tolerable safety profile, the most common adverse effects reported in trials were still as expected: sleep disturbances, headache, nausea, and sexual dysfunction. It is important to note that SSRIs should be used with caution during pregnancy, and paroxetine should be avoided in women considering pregnancy in the near future.

Other antidepressant classes have been studied to a lesser extent than SSRIs. Continuously dosed venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in PMS/PMDD treatment when compared with placebo within the first cycle of therapy.39 The response seen was comparable to that associated with SSRI treatments in other trials.

Buspirone, an anxiolytic with serotonin receptor activity that is different from that of the SSRIs, demonstrated efficacy in reducing the symptom of irritability.48 Buspirone may have a role to play in those presenting with irritability as a primary symptom or in those who are unable to tolerate the adverse effects of SSRIs. Tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion, and alprazolam have either limited data regarding efficacy or are associated with adverse effects that limit their use.38

Hormonal treatments may be worth considering

One commonly prescribed hormonal therapy for PMS and PMDD is continuous OCs. A 2012 Cochrane review of OCs containing drospirenone evaluated 5 trials and a total of 1920 women.40 Two placebo-controlled trials of women with severe premenstrual symptoms (PMDD) showed improvement after 3 months of taking daily drospirenone 3 mg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg, compared with placebo.

While experiencing greater benefit, these groups also experienced significantly more adverse effects including nausea, intermenstrual bleeding, and breast pain. The respective odds ratios for the 3 adverse effects were 3.15 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.90-5.22), 4.92 (95% CI, 3.03-7.96), and 2.67 (95% CI, 1.50-4.78). The review concluded that drospirenone 3 mg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg may help in the treatment of severe premenstrual symptoms (PMDD) but that it is unknown whether this treatment is appropriate for patients with less severe premenstrual symptoms.

Continue to: Another multicenter RCT

Another multicenter RCT evaluated women with PMDD who received levonorgestrel 90 mcg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg or placebo daily for 112 days.41 Symptoms were recorded utilizing the DRSP. Significantly more women taking the daily combination hormone (52%) than placebo (40%) had a positive response (≥ 50% improvement in the DRSP 7-day late luteal phase score and Clinical Global Impression of Severity score of ≥ 1 improvement, evaluated at the last “on-therapy” cycle [P = .025]). Twenty-three of 186 patients in the treatment arm dropped out because of adverse effects.

Noncontraceptive estrogen-containing preparations. Hormone therapy preparations containing lower doses of estrogen than seen in OC preparations have also been studied for PMS management. A 2017 Cochrane review of noncontraceptive estrogen-containing preparations found very low-quality evidence to support the effectiveness of continuous estrogen (transdermal patches or subcutaneous implants) plus progestogen.49

Progesterone. The cyclic use of progesterone in the luteal phase has been reviewed as a hormonal treatment for PMS. A 2012 Cochrane review of the efficacy of progesterone for PMS was inconclusive; however, route of administration, dose, and duration differed across studies.42

Another systematic review of 10 trials involving 531 women concluded that progesterone was no better than placebo in the treatment of PMS.43 However, it should be noted that each trial evaluated a different dose of progesterone, and all but 1 of the trials administered progesterone by using the calendar method to predict the beginning of the luteal phase. The only trial to use an objective confirmation of ovulation prior to beginning progesterone therapy did demonstrate significant improvement in premenstrual symptoms.

This 1985 study by Dennerstein et al44 prescribed progesterone for 10 days of each menstrual cycle starting 3 days after ovulation. In each cycle, ovulation was confirmed by determinations of urinary 24-hour pregnanediol and total estrogen concentrations. Progesterone was then prescribed during the objectively identified luteal phase, resulting in significant improvement in symptoms.

Continue to: Another study evaluated...

Another study evaluated the post-ovulatory progesterone profiles of 77 women with symptoms of PMS and found lower levels of progesterone and a sharper rate of decline in the women with PMS vs the control group.45 Subsequent progesterone treatment during the objectively identified luteal phase significantly improved PMS symptoms. These studies would seem to suggest that progesterone replacement when administered during an objectively identified luteal phase may offer some benefit in the treatment of PMS, but larger RCTs are needed to confirm this.

CASE

You provide the patient with diet and lifestyle education as well as a recommendation for calcium supplementation. The patient agrees to prospectively chart her most significant premenstrual symptoms. You review additional treatment options including SSRI medications and hormonal approaches. She is using a fertility awareness–based method of family planning that allows her to confidently identify her luteal phase. She agrees to take sertraline 50 mg/d during the luteal phase of her cycle. At her follow-up office visit 3 months later, she reports improvement in her premenstrual symptoms. Her charting of symptoms confirms this.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter Danis, MD, Mercy Family Medicine St. Louis, 12680 Olive Boulevard, St. Louis, MO 63141; Peter.Danis@mercy.net.

1. Woods NF, Most A, Dery GK. Prevalence of perimenstrual symptoms. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:1257-1264.

2. Johnson SR, McChesney C, Bean JA. Epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms in a nonclinical sample. 1. Prevalence, natural history and help-seeking behavior. J Repro Med. 1988;33:340-346.

3. Campbell EM, Peterkin D, O’Grady K, et al. Premenstrual symptoms in general practice patients. Prevalence and treatment. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:637-646.

4. O’Brien PM, Bäckström T, Brown C, et al. Towards a consensus on diagnostic criteria, measurement, and trial design of the premenstrual disorders: the ISPMD Montreal consensus. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:13-21.

5. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:465-475.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Women’s Health Care: A Resource Manual. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2014:607-613.

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

8. Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Heinemann K. Epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms and disorders. Menopause Int. 2012;18:48-51.

9. Borenstein JE, Dean BB, Yonkers KA, et al. Using the daily record of severity of problems as a screening instrument for premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1068-1075.

10. Steiner M, Macdougall M, Brown E. The premenstrual symptoms screening tool (PSST) for clinicians. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6:203-209.

11. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:41-49.

12. Janda C, Kues JN, Andersson G, et al. A symptom diary to assess severe premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Women Health. 2017;57:837-854.

13. Farasati N, Siassi F, Koohdani F, et al. Western dietary pattern is related to premenstrual syndrome: a case-control study. Brit J Nutr. 2015;114:2016-2021.

14. Purdue-Smithe AC, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. A prospective study of caffeine and coffee intake and premenstrual syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:499-507.

15. Bertone-Johnson ER, Hankinson SE, Bendich A, et al. Calcium and vitamin D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1246-1252.

16. Chocano-Bedoya PO, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. Dietary B vitamin intake and incident premenstrual syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1080-1086.

17. Prior JC, Vigna Y. Conditioning exercise and premenstrual symptoms. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:423-428.

18. Aganoff JA, Boyle GJ. Aerobic exercise, mood states, and menstrual cycle symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:183-192.

19. El-Lithy A, El-Mazny A, Sabbour A, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on premenstrual symptoms, haematological and hormonal parameters in young women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35:389-392.

20. Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Ronnenberg AG, Zagarins SE, et al. Recreational physical activity and premenstrual syndrome in young adult women: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:1-13.

21. Jang SH, Kim DI, Choi MS. Effects and treatment methods of acupuncture and herbal medicine for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:11.

22. Kim SY, Park HJ, Lee H, et al. Acupuncture for premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJOG. 2011;118:899-915.

23. Lustyk MK, Gerrish WG, Shaver S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:85-96.

24. Thys-Jacob S, Starkey P, Bernstein D, et al. Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: effects on premenstrual and menstrual syndromes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:444-452.

25. Ghanbari Z, Haghollahi F, Shariat M, et al. Effects of calcium supplement therapy in women with premenstrual syndrome. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48:124-129.

26. Girman A, Lee R, Kligler B. An integrative medicine approach to premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5 suppl):s56-s65.

27. Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Jones PW, et al. Efficacy of vitamin B-6 in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ. 1999;318:1375-1381.

28. Verkaik S, Kamperman AM, van Westrhenen R, et al. The treatment of premenstrual syndrome with preparations of vitex agnus castus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:150-166.

29. Boyle NB, Lawton C, Dye L. The effects of magnesium supplementation on subjective anxiety and stress—a systematic review. Nutrients. 2017;9:429-450.

30. Mauskop A, Altura BT, Altura BM. Serum ionized magnesium levels and serum ionized calcium/ionized magnesium ratios in women with menstrual migraine. Headache. 2002;42:242-248.

31. Facchinetti F, Sances C, Borella P, et al. Magnesium prophylaxis of menstrual migraine: effects on intracellular magnesium. Headache. 1991;31:298-301.

32. Parsay S, Olfati F, Nahidi S. Therapeutic effects of vitamin E on cyclic mastalgia. Breast J. 2009;15:510-514.

33. London RS, Murphy L, Kitlowski KE, et al. Efficacy of alpha-tocopherol in the treatment of the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:400-404.

34. Whelan AM, Jurgens TM, Naylor H. Herbs, vitamins, and minerals in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;16:e407-e429.

, , , . Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6): CD001396.

36. Dimmock P, Wyatt K, Jones P, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:1131-1136.

37. Shah NR, Jones JB, Aperi J, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1175-1182.

38. Freeman EW. Luteal phase administration of agents for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:453-468.

39. Freeman EW, Rickels K, Yonkers KA, et al. Venlafaxine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:737-744.

40. Lopez LM, Kaptein AA, Helmerhorst FM. Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD006586.

41. Halbreich U, Freeman EW, Rapkin AJ, et al. Continuous oral levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol for treating premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Contraception. 2012;85:19-27.

, , , . Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD003415.

43. Wyatt K, Dimmock P, Jones P, et al. Efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in management of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323: 776-780.

44. Dennerstein L, Spencer-Gardner C, Gotts G, et al. Progesterone and the premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind crossover trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290:1617-1621.

45. NaProTECHNOLOGY. The Medical and Surgical Practice of NaProTECHNOLOGY. Premenstrual Syndrome: Evaluation and Treatment. Omaha, NE: Pope Paul VI Institute Press. 2004;29:345-368. https://www.naprotechnology.com/naprotext.htm. Accessed January 23, 2020.

46. Dante G, Facchinetti F. Herbal treatments for alleviating premenstrual symptoms: a systematic review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;32:42-51.

47. Jarvis CI, Lynch AM, Morin AK. Management strategies for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:967-978.

48. Landen M, Eriksson O, Sundblad C, et al. Compounds with affinity for serotonergic receptors in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria: a comparison of buspirone, nefazodone and placebo. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;155:292-298.

, , , . Non-contraceptive oestrogen-containing preparations for controlling symptoms of premenstrual syndrome . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017 ;( 3) :CD010503.

CASE

A 30-year-old G2P2 woman presents for a well-woman visit and reports 6 months of premenstrual symptoms including irritability, depression, breast pain, and headaches. She is not taking any medications or hormonal contraceptives. She is sexually active and currently not interested in becoming pregnant. She asks what you can do for her symptoms, as they are affecting her life at home and at work.

Symptoms and definitions vary

Although more than 150 premenstrual symptoms have been reported, the most common psychological and behavioral ones are mood swings, depression, anxiety, irritability, crying, social withdrawal, forgetfulness, and problems concentrating.1-3 The most common physical symptoms are fatigue, abdominal bloating, weight gain, breast tenderness, acne, change in appetite or food cravings, edema, headache, and gastrointestinal upset. The etiology of these symptoms is usually multifactorial, with some combination of hormonal, neurotransmitter, lifestyle, environmental, and psychosocial factors playing a role.

Premenstrual disorder. In reviewing diagnostic criteria for the various premenstrual syndromes and disorders from different organizations (eg, the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders; the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition), there is agreement on the following criteria for premenstrual syndrome (PMS)4-6:

- The woman must be ovulating. (Women who no longer menstruate [eg, because of hysterectomy or endometrial ablation] can have premenstrual disorders as long as ovarian function remains intact.)

- The woman experiences a constellation of disabling physical and/or psychological symptoms that appears in the luteal phase of her menstrual cycle.

- The symptoms improve soon after the onset of menses.

- There is a symptom-free interval before ovulation.

- There is prospective documentation of symptoms for at least 2 consecutive cycles.

- The symptoms are sufficient in severity to affect activities of daily living and/or important relationships.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. PMDD is another common premenstrual disorder. It is distinguished by significant premenstrual psychological symptoms and requires the presence of marked affective lability, marked irritability or anger, markedly depressed mood, and/or marked anxiety (TABLE 1).7

Exacerbation of other ailments. Another premenstrual disorder is the premenstrual exacerbation of underlying chronic medical or psychological problems such as migraines, seizures, asthma, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, anxiety, or depression.

Differences in interpretation lead to variations in prevalence

Differences in the interpretation of significant premenstrual symptoms have led to variations in estimated prevalence. For example, 80% to 95% of women report premenstrual symptoms, but only 30% to 40% meet criteria for PMS and only 3% to 8% meet criteria for PMDD.8 Many women who report premenstrual symptoms in a retrospective questionnaire do not meet criteria for PMS or PMDD based on prospective symptom charting. The Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP), a prospective tracking tool for premenstrual symptoms, is sensitive and specific for diagnosing PMS and PMDD if administered on the first day of menstruation.9

Ask about symptoms and use a tracking tool

When you see a woman for a well-woman visit or a gynecologic problem, inquire about physical/emotional symptoms and their severity during the week that precedes menstruation. If a patient reports few symptoms of a mild nature, then no further work-up is needed.

Continue to: If patients report significant...

If patients report significant premenstrual symptoms, recommend the use of a tool to track the symptoms. Older tools such as the DRSP and the Premenstrual Symptoms Screening Tool (PSST), newer symptom diaries that can be used for both PMS and PMDD,and questionnaires that have been used in research situations can be time consuming and difficult for patients to complete.10-12 Instead, physicians can easily construct their own charting tool, as we did for patients to use when tracking their most bothersome symptoms (FIGURE 1). Tracking helps to confirm the diagnosis and helps you and the patient focus on treatment goals.

Keep in mind other diagnoses (eg, anemia, thyroid disorders, perimenopause, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance abuse) that can cause or exacerbate the psychological/physical symptoms the patient is reporting. If you suspect any of these other diagnoses, laboratory evaluation (eg, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone level or other hormonal testing, urine drug screen, etc) may be warranted to rule out other etiologies for the reported symptoms.

Develop a Tx plan that considers symptoms, family-planning needs

Focus treatment on the patient’s predominant symptoms whether they are physical, psychological, or mixed (FIGURE 2). The patient’s preferences regarding family planning are another important consideration. Women who are using a fertility awareness

Although the definitions for PMS and PMDD require at least 2 cycles of prospective documentation of symptoms, dietary and lifestyle changes can begin immediately. Regular follow-up to document improvement of symptoms is important; using the patient’s symptoms charting tool can help with this.

Focus on diet and lifestyle right away

Experts in the field of PMS/PMDD suggest that simple dietary changes may be a reasonable first step to help improve symptoms. Researchers have found that diets high in fiber, vegetables, and whole grains are inversely related to PMS.13 Older studies have suggested an increased prevalence and severity of PMS with increased caffeine intake; however, a newer study found no such association.14

Continue to: A case-control study nested...

A case-control study nested within the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort showed that a high intake of both dietary calcium and vitamin D prevented the development of PMS in women ages 27 to 44.15 B vitamins, such as thiamine and riboflavin, from food sources have been associated with a lower risk of PMS.16 A variety of older clinical studies showed benefit from aerobic exercise on PMS symptoms,17-19 but a newer cross-sectional study of young adult women found no association between physical activity and the prevalence of PMS.20 Acupuncture has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of the physical symptoms of PMS and PMDD, but more rigorous studies are needed.21,22 Cognitive behavioral therapy has been studied as a treatment, but data to support this approach are limited so it cannot be recommended at this time.23

Make the most of supplements—especially calcium

Calcium is the nutritional supplement with the most evidence to support its use to relieve symptoms of PMS and PMDD (TABLE 221,22,24-45). Research indicates that disturbances in calcium regulation and calcium deficiency may be responsible for various premenstrual symptoms. One study showed that, compared with placebo, women who took 1200 mg/d calcium carbonate for 3 menstrual cycles had a 48% decrease in both somatic and affective symptoms.24 Another trial demonstrated improvement in PMS symptoms of early tiredness, appetite changes, and depression with calcium therapy.25

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) has potential benefit in treating PMS due to its ability to increase levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, and taurine.26 An older systematic review showed benefit for symptoms associated with PMS, but the authors concluded that larger randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were needed before definitive recommendations could be made.27

Chasteberry. A number of studies have evaluated the effect of vitex agnus castus (VAC), commonly referred to as chasteberry, on PMS and PMDD symptoms. The exact mechanism of VAC is unknown, but in vitro studies show binding of VAC extracts to dopamine-2 receptors and opioid receptors, and an affinity for estrogen receptors.28

A recent meta-analysis concluded that VAC extracts are not superior to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or oral contraceptives (OCs) for PMS/PMDD.28 The authors suggested a possible benefit of VAC compared with placebo or other nutritional supplements; however, the studies supporting its use are limited by small sample size and potential bias.

Continue to: Magnesium

Magnesium. Many small studies have evaluated the role of other herbal and nutritional supplements for the treatment of PMS/PMDD. A systematic review of studies on the effect of magnesium supplementation on anxiety and stress showed that magnesium may have a potential role in the treatment of the premenstrual symptom of anxiety.29 Other studies have demonstrated a potential role in the treatment of premenstrual migraine.30,31

Vitamin E has demonstrated benefit in the treatment of cyclic mastalgia; however, evidence for using vitamin E for mood and depressive symptoms associated with PMS and PMDD is inconsistent.32-34 Other studies involving vitamin D, St. John’s wort, black cohosh, evening primrose oil, saffron, and ginkgo biloba either showed these agents to be nonefficacious in relieving PMS/PMDD symptoms or to require more data before they can be recommended for use.34,46

Patient doesn’t respond? Start an SSRI

Pharmacotherapy with antidepressants is typically reserved for those who do not respond to nonpharmacologic therapies and are experiencing more moderate to severe symptoms of PMS or PMDD. Reduced levels of serotonin and serotonergic activity in the brain may be linked to symptoms of PMS and PMDD.47 Studies have shown SSRIs to be effective in reducing many psychological symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, lethargy, irritability) and some physical symptoms (eg, headache, breast tenderness, muscle or joint pain) associated with PMS and PMDD.

A Cochrane review of 31 RCTs compared various SSRIs to placebo. When taken either continuously or intermittently (administration during luteal phase), SSRIs were similarly effective in relieving symptoms when compared with placebo.35 Psychological symptoms are more likely to improve with both low and moderate doses of SSRIs, while physical symptoms may only improve with moderate or higher doses. A direct comparison of the various SSRIs for the treatment of PMS or PMDD is lacking; therefore, the selection of SSRI may be based on patient characteristics and preference.

The benefits of SSRIs are noted much earlier in the treatment of PMS/PMDD than they are observed in their use for depression or anxiety.36 This suggests that the mechanism by which SSRIs relieve PMS/PMDD symptoms is different than that for depression or anxiety. Intermittent dosing capitalizes upon the rapid effect seen with these medications and the cyclical nature of these disorders. In most studies, the benefit of intermittent dosing is similar to continuous dosing; however, one meta-analysis did note that continuous dosing had a larger effect.37

Continue to: The doses of SSRIs...

The doses of SSRIs used in most PMS/PMDD trials were lower than those typically used for the treatment of depression and anxiety. The withdrawal effect that can be seen with abrupt cessation of SSRIs has not been reported in the intermittent-dosing studies for PMS/PMDD.38 While this might imply a more tolerable safety profile, the most common adverse effects reported in trials were still as expected: sleep disturbances, headache, nausea, and sexual dysfunction. It is important to note that SSRIs should be used with caution during pregnancy, and paroxetine should be avoided in women considering pregnancy in the near future.

Other antidepressant classes have been studied to a lesser extent than SSRIs. Continuously dosed venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in PMS/PMDD treatment when compared with placebo within the first cycle of therapy.39 The response seen was comparable to that associated with SSRI treatments in other trials.

Buspirone, an anxiolytic with serotonin receptor activity that is different from that of the SSRIs, demonstrated efficacy in reducing the symptom of irritability.48 Buspirone may have a role to play in those presenting with irritability as a primary symptom or in those who are unable to tolerate the adverse effects of SSRIs. Tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion, and alprazolam have either limited data regarding efficacy or are associated with adverse effects that limit their use.38

Hormonal treatments may be worth considering

One commonly prescribed hormonal therapy for PMS and PMDD is continuous OCs. A 2012 Cochrane review of OCs containing drospirenone evaluated 5 trials and a total of 1920 women.40 Two placebo-controlled trials of women with severe premenstrual symptoms (PMDD) showed improvement after 3 months of taking daily drospirenone 3 mg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg, compared with placebo.

While experiencing greater benefit, these groups also experienced significantly more adverse effects including nausea, intermenstrual bleeding, and breast pain. The respective odds ratios for the 3 adverse effects were 3.15 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.90-5.22), 4.92 (95% CI, 3.03-7.96), and 2.67 (95% CI, 1.50-4.78). The review concluded that drospirenone 3 mg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg may help in the treatment of severe premenstrual symptoms (PMDD) but that it is unknown whether this treatment is appropriate for patients with less severe premenstrual symptoms.

Continue to: Another multicenter RCT

Another multicenter RCT evaluated women with PMDD who received levonorgestrel 90 mcg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg or placebo daily for 112 days.41 Symptoms were recorded utilizing the DRSP. Significantly more women taking the daily combination hormone (52%) than placebo (40%) had a positive response (≥ 50% improvement in the DRSP 7-day late luteal phase score and Clinical Global Impression of Severity score of ≥ 1 improvement, evaluated at the last “on-therapy” cycle [P = .025]). Twenty-three of 186 patients in the treatment arm dropped out because of adverse effects.

Noncontraceptive estrogen-containing preparations. Hormone therapy preparations containing lower doses of estrogen than seen in OC preparations have also been studied for PMS management. A 2017 Cochrane review of noncontraceptive estrogen-containing preparations found very low-quality evidence to support the effectiveness of continuous estrogen (transdermal patches or subcutaneous implants) plus progestogen.49

Progesterone. The cyclic use of progesterone in the luteal phase has been reviewed as a hormonal treatment for PMS. A 2012 Cochrane review of the efficacy of progesterone for PMS was inconclusive; however, route of administration, dose, and duration differed across studies.42

Another systematic review of 10 trials involving 531 women concluded that progesterone was no better than placebo in the treatment of PMS.43 However, it should be noted that each trial evaluated a different dose of progesterone, and all but 1 of the trials administered progesterone by using the calendar method to predict the beginning of the luteal phase. The only trial to use an objective confirmation of ovulation prior to beginning progesterone therapy did demonstrate significant improvement in premenstrual symptoms.

This 1985 study by Dennerstein et al44 prescribed progesterone for 10 days of each menstrual cycle starting 3 days after ovulation. In each cycle, ovulation was confirmed by determinations of urinary 24-hour pregnanediol and total estrogen concentrations. Progesterone was then prescribed during the objectively identified luteal phase, resulting in significant improvement in symptoms.

Continue to: Another study evaluated...

Another study evaluated the post-ovulatory progesterone profiles of 77 women with symptoms of PMS and found lower levels of progesterone and a sharper rate of decline in the women with PMS vs the control group.45 Subsequent progesterone treatment during the objectively identified luteal phase significantly improved PMS symptoms. These studies would seem to suggest that progesterone replacement when administered during an objectively identified luteal phase may offer some benefit in the treatment of PMS, but larger RCTs are needed to confirm this.

CASE

You provide the patient with diet and lifestyle education as well as a recommendation for calcium supplementation. The patient agrees to prospectively chart her most significant premenstrual symptoms. You review additional treatment options including SSRI medications and hormonal approaches. She is using a fertility awareness–based method of family planning that allows her to confidently identify her luteal phase. She agrees to take sertraline 50 mg/d during the luteal phase of her cycle. At her follow-up office visit 3 months later, she reports improvement in her premenstrual symptoms. Her charting of symptoms confirms this.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter Danis, MD, Mercy Family Medicine St. Louis, 12680 Olive Boulevard, St. Louis, MO 63141; Peter.Danis@mercy.net.

CASE