User login

Is exercise effective for constipation?

I recently presented a clinical scenario about a patient of mine named Brenda. This 35-year-old woman came to me with symptoms that had been going on for a year already. I asked for readers’ comments about my management of Brenda.

I appreciate the comments I received regarding this case. The most common suggestion was to encourage Brenda to exercise, and a systematic review of randomized clinical trials published in 2019 supports this recommendation. This review included nine studies with a total of 680 participants, and the overall effect of exercise was a twofold improvement in symptoms associated with constipation. Walking was the most common exercise intervention, and along with qigong (which combines body position, breathing, and meditation), these two modes of exercise were effective in improving constipation. However, the one study evaluating resistance training failed to demonstrate a significant effect. Importantly, the reviewers considered the collective research to be at a high risk of bias.

Exercise will probably help Brenda, although some brainstorming might be necessary to help her fit exercise into her busy schedule. Another suggestion focused on her risk for colorectal cancer, and Dr. Cooke and Dr. Boboc both astutely noted that colorectal cancer is increasingly common among adults at early middle age. This stands in contrast to a steady decline in the prevalence of colorectal cancer among U.S. adults at age 65 years or older. Whereas colorectal cancer declined by 3.3% annually among U.S. older adults from 2011 to 2016, there was a reversal of this favorable trend among individuals between 50 and 64 years of age, with rates increasing by 1% annually.

The increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer among adults 50-64 years of age has been outpaced by the increase among adults younger than 50 years, who have experienced a 2.2% increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer annually between 2012 and 2016. Previously, the increase in colorectal cancer among early middle-aged adults was driven by higher rates of rectal cancer, but more recently this trend has included higher rates of proximal and distal colon tumors. In 2020, 12% of new cases of colorectal cancer were expected to be among individuals younger than 50 years.

So how do we act on this context in the case of Brenda? Her history suggests no overt warning signs for cancer. The history did not address a family history of gastrointestinal symptoms or colorectal cancer, which is an important omission.

Although the number of cases of cancer among persons younger than 50 years may be rising, the overall prevalence of colorectal cancer among younger adults is well under 1%. At 35 years of age, it is not necessary to evaluate Brenda for colorectal cancer. However, persistent or worsening symptoms could prompt a referral for colonoscopy at a later time.

Finally, let’s address how to practically manage Brenda’s case, because many options are available. I would begin with recommendations regarding her lifestyle, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, and whatever she can achieve in the FODMAP diet. I would also recommend psyllium as a soluble fiber and expect that these changes would help her constipation. But they might be less effective for abdominal cramping, so I would also recommend peppermint oil at this time.

If Brenda commits to these recommendations, she will very likely improve. If she does not, I will be more concerned regarding anxiety and depression complicating her illness. Treating those disorders can make a big difference.

In addition, if there is an inadequate response to initial therapy, I will initiate linaclotide or lubiprostone. Plecanatide is another reasonable option. At this point, I will also consider referral to a gastroenterologist for a recalcitrant case and will certainly refer if one of these specific treatments fails in Brenda. Conditions such as pelvic floor dysfunction can mimic irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and merit consideration.

However, I really believe that Brenda will feel better. Thanks for all of the insightful and interesting comments. It is easy to see how we are all invested in improving patients’ lives.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported disclosures with McNeil Pharmaceuticals. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I recently presented a clinical scenario about a patient of mine named Brenda. This 35-year-old woman came to me with symptoms that had been going on for a year already. I asked for readers’ comments about my management of Brenda.

I appreciate the comments I received regarding this case. The most common suggestion was to encourage Brenda to exercise, and a systematic review of randomized clinical trials published in 2019 supports this recommendation. This review included nine studies with a total of 680 participants, and the overall effect of exercise was a twofold improvement in symptoms associated with constipation. Walking was the most common exercise intervention, and along with qigong (which combines body position, breathing, and meditation), these two modes of exercise were effective in improving constipation. However, the one study evaluating resistance training failed to demonstrate a significant effect. Importantly, the reviewers considered the collective research to be at a high risk of bias.

Exercise will probably help Brenda, although some brainstorming might be necessary to help her fit exercise into her busy schedule. Another suggestion focused on her risk for colorectal cancer, and Dr. Cooke and Dr. Boboc both astutely noted that colorectal cancer is increasingly common among adults at early middle age. This stands in contrast to a steady decline in the prevalence of colorectal cancer among U.S. adults at age 65 years or older. Whereas colorectal cancer declined by 3.3% annually among U.S. older adults from 2011 to 2016, there was a reversal of this favorable trend among individuals between 50 and 64 years of age, with rates increasing by 1% annually.

The increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer among adults 50-64 years of age has been outpaced by the increase among adults younger than 50 years, who have experienced a 2.2% increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer annually between 2012 and 2016. Previously, the increase in colorectal cancer among early middle-aged adults was driven by higher rates of rectal cancer, but more recently this trend has included higher rates of proximal and distal colon tumors. In 2020, 12% of new cases of colorectal cancer were expected to be among individuals younger than 50 years.

So how do we act on this context in the case of Brenda? Her history suggests no overt warning signs for cancer. The history did not address a family history of gastrointestinal symptoms or colorectal cancer, which is an important omission.

Although the number of cases of cancer among persons younger than 50 years may be rising, the overall prevalence of colorectal cancer among younger adults is well under 1%. At 35 years of age, it is not necessary to evaluate Brenda for colorectal cancer. However, persistent or worsening symptoms could prompt a referral for colonoscopy at a later time.

Finally, let’s address how to practically manage Brenda’s case, because many options are available. I would begin with recommendations regarding her lifestyle, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, and whatever she can achieve in the FODMAP diet. I would also recommend psyllium as a soluble fiber and expect that these changes would help her constipation. But they might be less effective for abdominal cramping, so I would also recommend peppermint oil at this time.

If Brenda commits to these recommendations, she will very likely improve. If she does not, I will be more concerned regarding anxiety and depression complicating her illness. Treating those disorders can make a big difference.

In addition, if there is an inadequate response to initial therapy, I will initiate linaclotide or lubiprostone. Plecanatide is another reasonable option. At this point, I will also consider referral to a gastroenterologist for a recalcitrant case and will certainly refer if one of these specific treatments fails in Brenda. Conditions such as pelvic floor dysfunction can mimic irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and merit consideration.

However, I really believe that Brenda will feel better. Thanks for all of the insightful and interesting comments. It is easy to see how we are all invested in improving patients’ lives.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported disclosures with McNeil Pharmaceuticals. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I recently presented a clinical scenario about a patient of mine named Brenda. This 35-year-old woman came to me with symptoms that had been going on for a year already. I asked for readers’ comments about my management of Brenda.

I appreciate the comments I received regarding this case. The most common suggestion was to encourage Brenda to exercise, and a systematic review of randomized clinical trials published in 2019 supports this recommendation. This review included nine studies with a total of 680 participants, and the overall effect of exercise was a twofold improvement in symptoms associated with constipation. Walking was the most common exercise intervention, and along with qigong (which combines body position, breathing, and meditation), these two modes of exercise were effective in improving constipation. However, the one study evaluating resistance training failed to demonstrate a significant effect. Importantly, the reviewers considered the collective research to be at a high risk of bias.

Exercise will probably help Brenda, although some brainstorming might be necessary to help her fit exercise into her busy schedule. Another suggestion focused on her risk for colorectal cancer, and Dr. Cooke and Dr. Boboc both astutely noted that colorectal cancer is increasingly common among adults at early middle age. This stands in contrast to a steady decline in the prevalence of colorectal cancer among U.S. adults at age 65 years or older. Whereas colorectal cancer declined by 3.3% annually among U.S. older adults from 2011 to 2016, there was a reversal of this favorable trend among individuals between 50 and 64 years of age, with rates increasing by 1% annually.

The increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer among adults 50-64 years of age has been outpaced by the increase among adults younger than 50 years, who have experienced a 2.2% increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer annually between 2012 and 2016. Previously, the increase in colorectal cancer among early middle-aged adults was driven by higher rates of rectal cancer, but more recently this trend has included higher rates of proximal and distal colon tumors. In 2020, 12% of new cases of colorectal cancer were expected to be among individuals younger than 50 years.

So how do we act on this context in the case of Brenda? Her history suggests no overt warning signs for cancer. The history did not address a family history of gastrointestinal symptoms or colorectal cancer, which is an important omission.

Although the number of cases of cancer among persons younger than 50 years may be rising, the overall prevalence of colorectal cancer among younger adults is well under 1%. At 35 years of age, it is not necessary to evaluate Brenda for colorectal cancer. However, persistent or worsening symptoms could prompt a referral for colonoscopy at a later time.

Finally, let’s address how to practically manage Brenda’s case, because many options are available. I would begin with recommendations regarding her lifestyle, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, and whatever she can achieve in the FODMAP diet. I would also recommend psyllium as a soluble fiber and expect that these changes would help her constipation. But they might be less effective for abdominal cramping, so I would also recommend peppermint oil at this time.

If Brenda commits to these recommendations, she will very likely improve. If she does not, I will be more concerned regarding anxiety and depression complicating her illness. Treating those disorders can make a big difference.

In addition, if there is an inadequate response to initial therapy, I will initiate linaclotide or lubiprostone. Plecanatide is another reasonable option. At this point, I will also consider referral to a gastroenterologist for a recalcitrant case and will certainly refer if one of these specific treatments fails in Brenda. Conditions such as pelvic floor dysfunction can mimic irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and merit consideration.

However, I really believe that Brenda will feel better. Thanks for all of the insightful and interesting comments. It is easy to see how we are all invested in improving patients’ lives.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported disclosures with McNeil Pharmaceuticals. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The role of repeat uterine curettage in postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

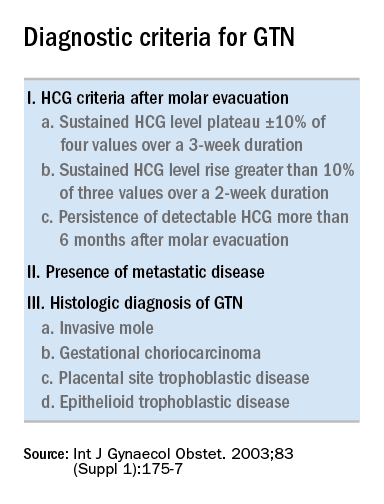

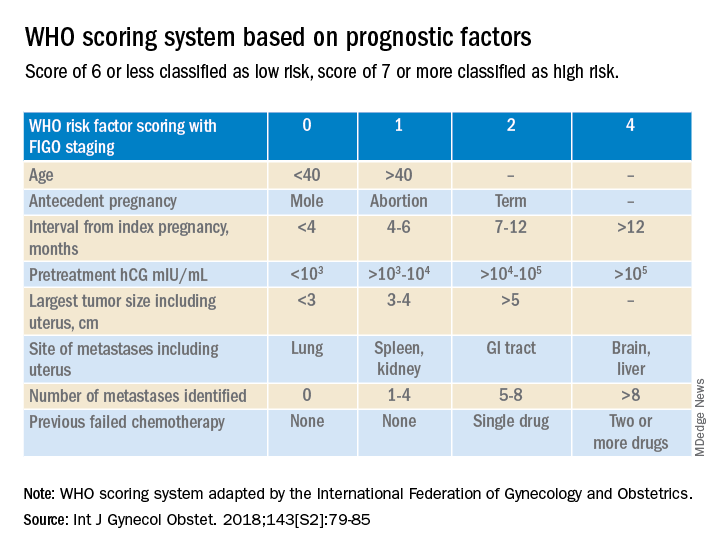

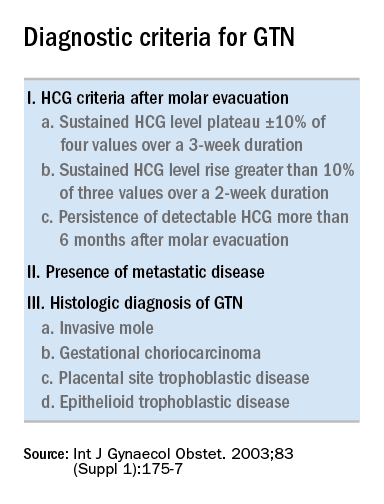

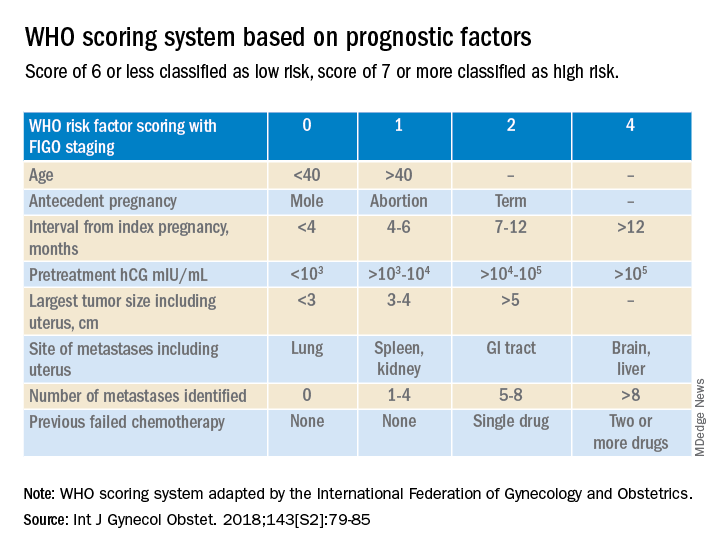

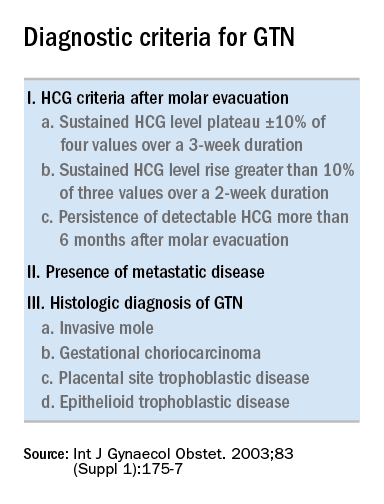

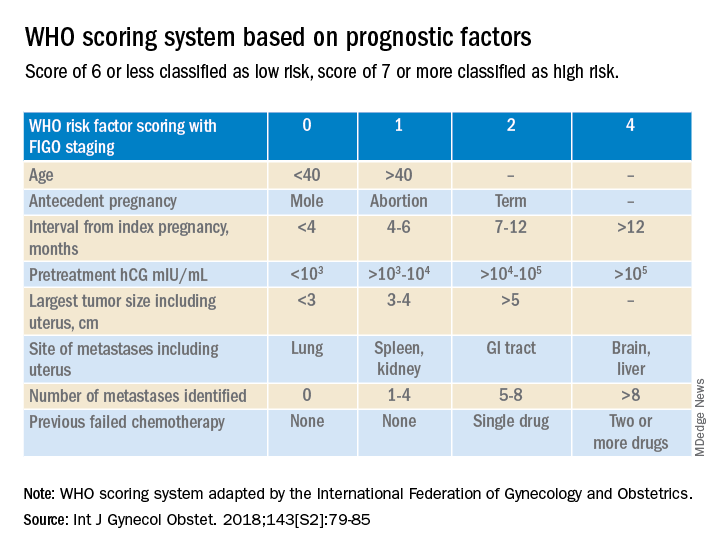

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Yes, we should talk politics and religion with patients

From our first days as medical students, we are told that politics and religion are topics to be avoided with patients, but I disagree. Knowing more about our patients allows us to deliver better care.

Politics and religion: New risk factors

The importance of politics and religion in the health of patients was clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lives were needlessly lost because of stands taken based on religious beliefs or a political ideology. Families, friends, and the community at large were impacted.

Over my years of practice, I have found that while these are difficult topics to address, they should not be avoided. Studies have shown that open acknowledgement of religious beliefs can affect both clinical outcomes and well-being. Religion and spirituality are as much a part of our patient’s lives as the physical parameters that we measure. To neglect these significant aspects is to miss the very essence of the individual.

I made it a practice to ask patients about their religious beliefs, the extent to which religion shaped their life, and whether they were part of a church community. Knowing this allowed me to separate deep personal belief from stances based on personal freedom, misinformation, conspiracies, and politics.

I found that information about political leanings flowed naturally in discussions with patients as we trusted and respected each other over time. If I approached politics objectively and nonjudgmentally, it generally led to meaningful conversation. This helped me to understand the patient as an individual and informed my diagnosis and treatment plan.

Politics as stress

For example, on more than one occasion, a patient with atrial fibrillation presented with persistent elevated blood pressure and pulse rate despite adherence to the medical regimen that I had prescribed. After a few minutes of discussion, it was clear that excessive attention to political commentary on TV and social media raised their anxiety and anger level, putting them at greater risk for adverse outcomes. I advised that they refocus their leisure activities rather than change or increase medication.

It is disappointing to see how one of the great scientific advances of our lifetime, vaccination science, has been tarnished because of political or religious ideology and to see the extent to which these beliefs influenced COVID-19 vaccination compliance. As health care providers, we must promote information based on the scientific method. If patients challenge us and point out that recommendations based on science seem to change over time, we must explain that science evolves on the basis of new information objectively gathered. We need to find out what information the patient has gotten from the Internet, TV, or conspiracy theories and counter this with scientific facts. If we do not discuss religion and politics with our patients along with other risk factors, we may compromise our ability to give them the best advice and treatment.

Our patients have a right to their own spiritual and political ideology. If it differs dramatically from our own, this should not influence our commitment to care for them. But we have an obligation to challenge unfounded beliefs about medicine and counter with scientific facts. There are times when individual freedoms must be secondary to public health. Ultimately, it is up to the patient to choose, but they should not be given a “free pass” on the basis of religion or politics. If I know something is true and I would do it myself or recommend it for my family, I have an obligation to provide this recommendation to my patients.

Religious preference is included in medical records. It is not appropriate to add political preference, but the patient benefits if a long-term caregiver knows this information.

During the pandemic, for the first time in my 40+ years of practice, some patients questioned my recommendations and placed equal or greater weight on religion, politics, or conspiracy theories. This continues to be a very real struggle.

Knowing and understanding our patients as individuals is critical to providing optimum care and that means tackling these formally taboo topics. If having a potentially uncomfortable conversation with patients allows us to save one life, it is worth it.

Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no relevant conflict of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From our first days as medical students, we are told that politics and religion are topics to be avoided with patients, but I disagree. Knowing more about our patients allows us to deliver better care.

Politics and religion: New risk factors

The importance of politics and religion in the health of patients was clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lives were needlessly lost because of stands taken based on religious beliefs or a political ideology. Families, friends, and the community at large were impacted.

Over my years of practice, I have found that while these are difficult topics to address, they should not be avoided. Studies have shown that open acknowledgement of religious beliefs can affect both clinical outcomes and well-being. Religion and spirituality are as much a part of our patient’s lives as the physical parameters that we measure. To neglect these significant aspects is to miss the very essence of the individual.

I made it a practice to ask patients about their religious beliefs, the extent to which religion shaped their life, and whether they were part of a church community. Knowing this allowed me to separate deep personal belief from stances based on personal freedom, misinformation, conspiracies, and politics.

I found that information about political leanings flowed naturally in discussions with patients as we trusted and respected each other over time. If I approached politics objectively and nonjudgmentally, it generally led to meaningful conversation. This helped me to understand the patient as an individual and informed my diagnosis and treatment plan.

Politics as stress

For example, on more than one occasion, a patient with atrial fibrillation presented with persistent elevated blood pressure and pulse rate despite adherence to the medical regimen that I had prescribed. After a few minutes of discussion, it was clear that excessive attention to political commentary on TV and social media raised their anxiety and anger level, putting them at greater risk for adverse outcomes. I advised that they refocus their leisure activities rather than change or increase medication.

It is disappointing to see how one of the great scientific advances of our lifetime, vaccination science, has been tarnished because of political or religious ideology and to see the extent to which these beliefs influenced COVID-19 vaccination compliance. As health care providers, we must promote information based on the scientific method. If patients challenge us and point out that recommendations based on science seem to change over time, we must explain that science evolves on the basis of new information objectively gathered. We need to find out what information the patient has gotten from the Internet, TV, or conspiracy theories and counter this with scientific facts. If we do not discuss religion and politics with our patients along with other risk factors, we may compromise our ability to give them the best advice and treatment.

Our patients have a right to their own spiritual and political ideology. If it differs dramatically from our own, this should not influence our commitment to care for them. But we have an obligation to challenge unfounded beliefs about medicine and counter with scientific facts. There are times when individual freedoms must be secondary to public health. Ultimately, it is up to the patient to choose, but they should not be given a “free pass” on the basis of religion or politics. If I know something is true and I would do it myself or recommend it for my family, I have an obligation to provide this recommendation to my patients.

Religious preference is included in medical records. It is not appropriate to add political preference, but the patient benefits if a long-term caregiver knows this information.

During the pandemic, for the first time in my 40+ years of practice, some patients questioned my recommendations and placed equal or greater weight on religion, politics, or conspiracy theories. This continues to be a very real struggle.

Knowing and understanding our patients as individuals is critical to providing optimum care and that means tackling these formally taboo topics. If having a potentially uncomfortable conversation with patients allows us to save one life, it is worth it.

Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no relevant conflict of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From our first days as medical students, we are told that politics and religion are topics to be avoided with patients, but I disagree. Knowing more about our patients allows us to deliver better care.

Politics and religion: New risk factors

The importance of politics and religion in the health of patients was clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lives were needlessly lost because of stands taken based on religious beliefs or a political ideology. Families, friends, and the community at large were impacted.

Over my years of practice, I have found that while these are difficult topics to address, they should not be avoided. Studies have shown that open acknowledgement of religious beliefs can affect both clinical outcomes and well-being. Religion and spirituality are as much a part of our patient’s lives as the physical parameters that we measure. To neglect these significant aspects is to miss the very essence of the individual.

I made it a practice to ask patients about their religious beliefs, the extent to which religion shaped their life, and whether they were part of a church community. Knowing this allowed me to separate deep personal belief from stances based on personal freedom, misinformation, conspiracies, and politics.

I found that information about political leanings flowed naturally in discussions with patients as we trusted and respected each other over time. If I approached politics objectively and nonjudgmentally, it generally led to meaningful conversation. This helped me to understand the patient as an individual and informed my diagnosis and treatment plan.

Politics as stress

For example, on more than one occasion, a patient with atrial fibrillation presented with persistent elevated blood pressure and pulse rate despite adherence to the medical regimen that I had prescribed. After a few minutes of discussion, it was clear that excessive attention to political commentary on TV and social media raised their anxiety and anger level, putting them at greater risk for adverse outcomes. I advised that they refocus their leisure activities rather than change or increase medication.

It is disappointing to see how one of the great scientific advances of our lifetime, vaccination science, has been tarnished because of political or religious ideology and to see the extent to which these beliefs influenced COVID-19 vaccination compliance. As health care providers, we must promote information based on the scientific method. If patients challenge us and point out that recommendations based on science seem to change over time, we must explain that science evolves on the basis of new information objectively gathered. We need to find out what information the patient has gotten from the Internet, TV, or conspiracy theories and counter this with scientific facts. If we do not discuss religion and politics with our patients along with other risk factors, we may compromise our ability to give them the best advice and treatment.

Our patients have a right to their own spiritual and political ideology. If it differs dramatically from our own, this should not influence our commitment to care for them. But we have an obligation to challenge unfounded beliefs about medicine and counter with scientific facts. There are times when individual freedoms must be secondary to public health. Ultimately, it is up to the patient to choose, but they should not be given a “free pass” on the basis of religion or politics. If I know something is true and I would do it myself or recommend it for my family, I have an obligation to provide this recommendation to my patients.

Religious preference is included in medical records. It is not appropriate to add political preference, but the patient benefits if a long-term caregiver knows this information.

During the pandemic, for the first time in my 40+ years of practice, some patients questioned my recommendations and placed equal or greater weight on religion, politics, or conspiracy theories. This continues to be a very real struggle.

Knowing and understanding our patients as individuals is critical to providing optimum care and that means tackling these formally taboo topics. If having a potentially uncomfortable conversation with patients allows us to save one life, it is worth it.

Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no relevant conflict of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No such thing as an easy fix

Recently an article crossed my screen that drinking 4 cups of tea per day lowered the risk of type 2 diabetes by 17%. As these thing always seem to, it ended with a variant of “further research is needed.”

Encouraging? Sure. Definite? Nope.

I’ve seen plenty of articles suggesting coffee and/or tea have health benefits, though specifically on what varies, from lifespan to lowering the risk of a chronic medical condition (in this case, type 2 diabetes).

There are always numerous variables that aren’t clear. What kind of tea? Decaf or regular? Hot or iced? When you say cup, what do you mean? A lot of people, including me, probably consider anything smaller that a Starbucks grande to be for wimps.

While I can’t think of any off the top of my head, there’s probably a reasonable chance that, if I looked, I could find something that says coffee or tea are bad for you in some way, too.

Not that I’m planning on changing my already caffeinated drinking habits, which is probably the crux of these things for most of us. In a given day I have 1-2 cups of coffee and 3-4 bottles of diet green tea. Maybe 1-2 Diet Cokes in there some days. In winter more hot black tea. I’m probably a poster child for methylyxanthine toxicity.

I have no idea if all that coffee and tea are doing anything besides keeping me awake and alert for my patients. If they are, I certainly hope they’re lowering my risk of something bad.

Articles like this always get attention, and are often picked up by the general media. People love to think something so simple as drinking more tea or coffee would make a big difference in their lives. So it gets forwarded, people never read past the first paragraph or two, and don’t make it to the “further research is needed” line.

If an article ever came out refuting it, it probably wouldn’t get nearly as much press (who wants to read bad news?) and would be quickly forgotten outside of medical circles.

But the reality is that people are really looking for shortcuts. Unless you live under a rock, it’s pretty clear to both medical and lay people that such things as exercise and a healthy diet can help avoid multiple chronic health conditions. This doesn’t mean most of us, myself included, will do such faithfully. It just takes less time and effort to drink more tea than it does to go to the gym, so we want to believe.

That’s just human nature.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently an article crossed my screen that drinking 4 cups of tea per day lowered the risk of type 2 diabetes by 17%. As these thing always seem to, it ended with a variant of “further research is needed.”

Encouraging? Sure. Definite? Nope.

I’ve seen plenty of articles suggesting coffee and/or tea have health benefits, though specifically on what varies, from lifespan to lowering the risk of a chronic medical condition (in this case, type 2 diabetes).

There are always numerous variables that aren’t clear. What kind of tea? Decaf or regular? Hot or iced? When you say cup, what do you mean? A lot of people, including me, probably consider anything smaller that a Starbucks grande to be for wimps.

While I can’t think of any off the top of my head, there’s probably a reasonable chance that, if I looked, I could find something that says coffee or tea are bad for you in some way, too.

Not that I’m planning on changing my already caffeinated drinking habits, which is probably the crux of these things for most of us. In a given day I have 1-2 cups of coffee and 3-4 bottles of diet green tea. Maybe 1-2 Diet Cokes in there some days. In winter more hot black tea. I’m probably a poster child for methylyxanthine toxicity.

I have no idea if all that coffee and tea are doing anything besides keeping me awake and alert for my patients. If they are, I certainly hope they’re lowering my risk of something bad.

Articles like this always get attention, and are often picked up by the general media. People love to think something so simple as drinking more tea or coffee would make a big difference in their lives. So it gets forwarded, people never read past the first paragraph or two, and don’t make it to the “further research is needed” line.

If an article ever came out refuting it, it probably wouldn’t get nearly as much press (who wants to read bad news?) and would be quickly forgotten outside of medical circles.

But the reality is that people are really looking for shortcuts. Unless you live under a rock, it’s pretty clear to both medical and lay people that such things as exercise and a healthy diet can help avoid multiple chronic health conditions. This doesn’t mean most of us, myself included, will do such faithfully. It just takes less time and effort to drink more tea than it does to go to the gym, so we want to believe.

That’s just human nature.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently an article crossed my screen that drinking 4 cups of tea per day lowered the risk of type 2 diabetes by 17%. As these thing always seem to, it ended with a variant of “further research is needed.”

Encouraging? Sure. Definite? Nope.

I’ve seen plenty of articles suggesting coffee and/or tea have health benefits, though specifically on what varies, from lifespan to lowering the risk of a chronic medical condition (in this case, type 2 diabetes).

There are always numerous variables that aren’t clear. What kind of tea? Decaf or regular? Hot or iced? When you say cup, what do you mean? A lot of people, including me, probably consider anything smaller that a Starbucks grande to be for wimps.

While I can’t think of any off the top of my head, there’s probably a reasonable chance that, if I looked, I could find something that says coffee or tea are bad for you in some way, too.

Not that I’m planning on changing my already caffeinated drinking habits, which is probably the crux of these things for most of us. In a given day I have 1-2 cups of coffee and 3-4 bottles of diet green tea. Maybe 1-2 Diet Cokes in there some days. In winter more hot black tea. I’m probably a poster child for methylyxanthine toxicity.

I have no idea if all that coffee and tea are doing anything besides keeping me awake and alert for my patients. If they are, I certainly hope they’re lowering my risk of something bad.

Articles like this always get attention, and are often picked up by the general media. People love to think something so simple as drinking more tea or coffee would make a big difference in their lives. So it gets forwarded, people never read past the first paragraph or two, and don’t make it to the “further research is needed” line.

If an article ever came out refuting it, it probably wouldn’t get nearly as much press (who wants to read bad news?) and would be quickly forgotten outside of medical circles.

But the reality is that people are really looking for shortcuts. Unless you live under a rock, it’s pretty clear to both medical and lay people that such things as exercise and a healthy diet can help avoid multiple chronic health conditions. This doesn’t mean most of us, myself included, will do such faithfully. It just takes less time and effort to drink more tea than it does to go to the gym, so we want to believe.

That’s just human nature.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How to make the best of your worst reviews

I have a love-hate relationship with patient reviews and satisfaction scores. I love good reviews and hate bad ones. Actually, I skim good reviews and then dwell for days on the negative ones, trying to rack my brain as to what I did wrong. Like everyone else, I have off days when I’m tired or distracted or just overwhelmed. Though I try to bring my A game to every patient visit, realistically, I know that I don’t always achieve this. But, for me, the difference in my best visits and good-enough visits is the difference between a 4-star and 5-star review. What’s up with those 1-star reviews?

Many, many years ago, when patient satisfaction scores were in their infancy, our clinic rewarded any physician who got a 100% satisfaction score. On the surface that makes perfect sense – of course, our patients should be satisfied 100% of the time, right? When I asked one of the winners of this competition how he did it (I never scored 100%), he told me, “I just do whatever the patient wants me to do.” Yikes, I thought at the time. That may be the recipe for an A+ for patient satisfaction but not for quality or outcomes.

Sometimes, I know that they are going to be unhappy, such as when I decline to refill their drug of abuse. Other times, I have to exercise my best medical judgment and hope that my explanation does not alienate the patient. After all, when I say “no” to a patient request, it is with their overall health and well-being in mind. But I would be lying if I said that I have matured to the point that I’m not bothered by a negative review or a patient choosing to take their care elsewhere.

Most of us seek and welcome feedback. Over time, I’ve learned to do this during the visit by asking “Am I giving you too much information?” or “What do you think of the plan?” or “What’s most important to you?” There are times when I conclude the visit and know that the patient is not satisfied but remain unable to ferret out where I let them down – even, on occasion, when I ask them directly. Ideally, any feedback we get from our patients, positive or negative, would be specific and actionable. It rarely is.

There is no doubt we have entered the era of consumer medicine. Everything from the physical appearance of our clinics to the response time to electronic messages is fair game in how patients judge us. As we all know, patients assume competence – they are not usually impressed by your training or quality outcomes because they already believe you are clinically competent (or arguably they’d never set foot in your office). Instead of judging us how we often judge ourselves, patients form opinions about us by how we enter the room, whether we sit or stand, how long they wait in the exam room before we come in, or whether they like the nurse with whom we work. So many subtle things – many of which are outside of our control.

I often struggle with staying on time. When I am invariably walking into the room late, I make a point of thanking patients for their patience. When I’m very late, I offer a more detailed, HIPAA-compliant explanation. What I wish my patients saw was that I am often accommodating a patient who arrives late for their appointment or who wants me to address every concern they’ve had for the past 5 years. While I aspire to not allow the patient’s perception of the visit to unduly influence how I handle the visit, it inevitably does. I do want to have patients who are happy with their experience.

One of my friends is enviously pragmatic in her view on patient experience. “I’m not their friend and they don’t have to like me.” She emphasizes the clinical care she is providing and does not allow patients who are upset with some aspect of the care to weigh heavy on her. It may be that specialists are more likely to enjoy the luxury of putting aside how patients feel about them personally. In primary care, the patient-physician relationship is so central to what we do that ignoring your “likability” has the potential to threaten your professional viability.

I conclude this blog much like I started it. My desire is to allow the negative reviews, particularly if they have nothing actionable in them, to roll off my back and to keep my focus on the clinical care that I am providing. In actuality, I care deeply about how my patients experience their visit with me and will likely continue to take my reviews to heart.

Dr. Frank is a family physician in Neenah, Wisc. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I have a love-hate relationship with patient reviews and satisfaction scores. I love good reviews and hate bad ones. Actually, I skim good reviews and then dwell for days on the negative ones, trying to rack my brain as to what I did wrong. Like everyone else, I have off days when I’m tired or distracted or just overwhelmed. Though I try to bring my A game to every patient visit, realistically, I know that I don’t always achieve this. But, for me, the difference in my best visits and good-enough visits is the difference between a 4-star and 5-star review. What’s up with those 1-star reviews?

Many, many years ago, when patient satisfaction scores were in their infancy, our clinic rewarded any physician who got a 100% satisfaction score. On the surface that makes perfect sense – of course, our patients should be satisfied 100% of the time, right? When I asked one of the winners of this competition how he did it (I never scored 100%), he told me, “I just do whatever the patient wants me to do.” Yikes, I thought at the time. That may be the recipe for an A+ for patient satisfaction but not for quality or outcomes.

Sometimes, I know that they are going to be unhappy, such as when I decline to refill their drug of abuse. Other times, I have to exercise my best medical judgment and hope that my explanation does not alienate the patient. After all, when I say “no” to a patient request, it is with their overall health and well-being in mind. But I would be lying if I said that I have matured to the point that I’m not bothered by a negative review or a patient choosing to take their care elsewhere.

Most of us seek and welcome feedback. Over time, I’ve learned to do this during the visit by asking “Am I giving you too much information?” or “What do you think of the plan?” or “What’s most important to you?” There are times when I conclude the visit and know that the patient is not satisfied but remain unable to ferret out where I let them down – even, on occasion, when I ask them directly. Ideally, any feedback we get from our patients, positive or negative, would be specific and actionable. It rarely is.

There is no doubt we have entered the era of consumer medicine. Everything from the physical appearance of our clinics to the response time to electronic messages is fair game in how patients judge us. As we all know, patients assume competence – they are not usually impressed by your training or quality outcomes because they already believe you are clinically competent (or arguably they’d never set foot in your office). Instead of judging us how we often judge ourselves, patients form opinions about us by how we enter the room, whether we sit or stand, how long they wait in the exam room before we come in, or whether they like the nurse with whom we work. So many subtle things – many of which are outside of our control.

I often struggle with staying on time. When I am invariably walking into the room late, I make a point of thanking patients for their patience. When I’m very late, I offer a more detailed, HIPAA-compliant explanation. What I wish my patients saw was that I am often accommodating a patient who arrives late for their appointment or who wants me to address every concern they’ve had for the past 5 years. While I aspire to not allow the patient’s perception of the visit to unduly influence how I handle the visit, it inevitably does. I do want to have patients who are happy with their experience.

One of my friends is enviously pragmatic in her view on patient experience. “I’m not their friend and they don’t have to like me.” She emphasizes the clinical care she is providing and does not allow patients who are upset with some aspect of the care to weigh heavy on her. It may be that specialists are more likely to enjoy the luxury of putting aside how patients feel about them personally. In primary care, the patient-physician relationship is so central to what we do that ignoring your “likability” has the potential to threaten your professional viability.

I conclude this blog much like I started it. My desire is to allow the negative reviews, particularly if they have nothing actionable in them, to roll off my back and to keep my focus on the clinical care that I am providing. In actuality, I care deeply about how my patients experience their visit with me and will likely continue to take my reviews to heart.

Dr. Frank is a family physician in Neenah, Wisc. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I have a love-hate relationship with patient reviews and satisfaction scores. I love good reviews and hate bad ones. Actually, I skim good reviews and then dwell for days on the negative ones, trying to rack my brain as to what I did wrong. Like everyone else, I have off days when I’m tired or distracted or just overwhelmed. Though I try to bring my A game to every patient visit, realistically, I know that I don’t always achieve this. But, for me, the difference in my best visits and good-enough visits is the difference between a 4-star and 5-star review. What’s up with those 1-star reviews?

Many, many years ago, when patient satisfaction scores were in their infancy, our clinic rewarded any physician who got a 100% satisfaction score. On the surface that makes perfect sense – of course, our patients should be satisfied 100% of the time, right? When I asked one of the winners of this competition how he did it (I never scored 100%), he told me, “I just do whatever the patient wants me to do.” Yikes, I thought at the time. That may be the recipe for an A+ for patient satisfaction but not for quality or outcomes.

Sometimes, I know that they are going to be unhappy, such as when I decline to refill their drug of abuse. Other times, I have to exercise my best medical judgment and hope that my explanation does not alienate the patient. After all, when I say “no” to a patient request, it is with their overall health and well-being in mind. But I would be lying if I said that I have matured to the point that I’m not bothered by a negative review or a patient choosing to take their care elsewhere.

Most of us seek and welcome feedback. Over time, I’ve learned to do this during the visit by asking “Am I giving you too much information?” or “What do you think of the plan?” or “What’s most important to you?” There are times when I conclude the visit and know that the patient is not satisfied but remain unable to ferret out where I let them down – even, on occasion, when I ask them directly. Ideally, any feedback we get from our patients, positive or negative, would be specific and actionable. It rarely is.

There is no doubt we have entered the era of consumer medicine. Everything from the physical appearance of our clinics to the response time to electronic messages is fair game in how patients judge us. As we all know, patients assume competence – they are not usually impressed by your training or quality outcomes because they already believe you are clinically competent (or arguably they’d never set foot in your office). Instead of judging us how we often judge ourselves, patients form opinions about us by how we enter the room, whether we sit or stand, how long they wait in the exam room before we come in, or whether they like the nurse with whom we work. So many subtle things – many of which are outside of our control.

I often struggle with staying on time. When I am invariably walking into the room late, I make a point of thanking patients for their patience. When I’m very late, I offer a more detailed, HIPAA-compliant explanation. What I wish my patients saw was that I am often accommodating a patient who arrives late for their appointment or who wants me to address every concern they’ve had for the past 5 years. While I aspire to not allow the patient’s perception of the visit to unduly influence how I handle the visit, it inevitably does. I do want to have patients who are happy with their experience.

One of my friends is enviously pragmatic in her view on patient experience. “I’m not their friend and they don’t have to like me.” She emphasizes the clinical care she is providing and does not allow patients who are upset with some aspect of the care to weigh heavy on her. It may be that specialists are more likely to enjoy the luxury of putting aside how patients feel about them personally. In primary care, the patient-physician relationship is so central to what we do that ignoring your “likability” has the potential to threaten your professional viability.

I conclude this blog much like I started it. My desire is to allow the negative reviews, particularly if they have nothing actionable in them, to roll off my back and to keep my focus on the clinical care that I am providing. In actuality, I care deeply about how my patients experience their visit with me and will likely continue to take my reviews to heart.

Dr. Frank is a family physician in Neenah, Wisc. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is corporate telepsychiatry the solution to access to care problems?

When Sue W’s mother died in 2018, she struggled terribly. She was already seeing a psychotherapist and was taking duloxetine, prescribed by her primary care physician. But her grief was profound, and her depression became paralyzing. She needed to see a psychiatrist, and there were many available in or near her hometown, a Connecticut suburb of New York City, but neither Sue, her therapist, nor her primary care doctor could find a psychiatrist who participated with her insurance. Finally, she was given the name of a psychiatrist in Manhattan who practiced online, and she made an appointment on the Skypiatrist (a telepsychiatry group founded in 2016) website.

“I hesitated about it at first,” Sue said. “The doctor was nice, and I liked the convenience. Appointments were 15 minutes long, although the first session was longer. He focused on the medications, which was okay because I already have a therapist. And it was really easy. I made appointments on their website and I saw the doctor through the same site, and I really liked that I could send him messages.” The psychiatrist was responsive when Sue had trouble coming off duloxetine, and he gave her instructions for a slower taper. The treatment was affordable and accessible, and she got better.

When you also consider that many private-practice psychiatrists do not participate with insurance panels, online companies that do accept insurance may add value, convenience, and access.

Cerebral, the largest online psychiatric service in the country, began seeing patients in January 2020, offering medications and psychotherapy. They participate with a number of commercial insurers, and this varies by state, but not with Medicaid or Medicare. Patients pay a monthly fee, and an initial 30-minute medication evaluation session is conducted, often with a nurse practitioner. They advertise wait times of less than 7 days.

Another company, Done, offers treatment specifically for ADHD. They don’t accept insurance for appointments; patients must submit their own claims for reimbursement. Their pricing structure involves a fee of $199 for the first month, then $79 a month thereafter, which does not include medications. Hims – another online company – targets men with a variety of health issues, including mental health problems.

Some of these internet companies have been in the news recently for concerns related to quality of care and prescribing practices. A The Wall Street Journal article of March 26, 2022, quoted clinicians who had previously worked for Cerebral and Done who left because they felt pressured to see patients quickly and to prescribe stimulants. Not all of the prescribers were unhappy, however. Yina Cruz-Harris, a nurse practitioner at Done who has a doctorate in nursing practice, said that she manages 2,300 patients with ADHD for Done. Virtually all are on stimulants. She renews each patient’s monthly prescription from her New Jersey home, based mostly on online forms filled out by the patients. She’s fast, doing two renewals per minute, and Done pays her almost $10 per patient, working out to around $20,000 in monthly earnings.

In May, the Department of Justice began looking into Cerebral’s practices around controlled substances and more recently, Cerebral has been in the news for complaints from patients that they have been unable to reach their prescribers when problems arise. Some pharmacy chains have refused to fill prescriptions for controlled medications from online telehealth providers, and some online providers, including Cerebral, are no longer prescribing controlled substances. A front-page The Wall Street Journal article on Aug. 19, 2022, told the story of a man with a history of addiction who was prescribed stimulants after a brief appointment with a prescriber at Done. Family and friends in his sober house believe that the stimulants triggered a relapse, and he died of an opioid overdose.

During the early days of the pandemic, nonemergency psychiatric care was shut down and we all became virtual psychiatrists. Many of us saw new patients and prescribed controlled medications to people we had never met in real life.

“John Brown,” MD, PhD, spoke with me on the condition that I don’t use his real name or the name of the practice he left. He was hired by a traditional group practice with a multidisciplinary staff and several offices in his state. Most of the clinicians worked part time and were contractual employees, and Dr. Brown was hired to develop a specialty service. He soon learned that the practice – which participates with a number of insurance plans – was not financially stable, and it was acquired by an investment firm with no medical experience.

“They wanted everyone to work 40-hour weeks and see 14 patients a day, including 3-4 new patients, and suddenly everyone was overextended and exhausted. Overnight, most of the therapists left, and they hired nurse practitioners to replace many of the psychiatrists. People weren’t getting good care.” While this was not a telepsychiatry startup, it was a corporate takeover of a traditional practice that was unable to remain financially solvent while participating with insurance panels.

Like Sue W, Elizabeth K struggled to get treatment for ADHD even before the pandemic.

“I work multiple part-time jobs, don’t own a car, and don’t have insurance. Before telehealth became available, it was difficult and discouraging for me to maintain consistent treatment. It took me months to get initial appointments with a doctor and I live in one of the largest cities in the country.” She was pleased with the care she received by Done.

“I was pleasantly surprised by the authenticity and thoroughness of my first telehealth provider,” Elizabeth noted. “She remembered and considered more about me, my medical history, and details of my personal life than nearly every psychiatric doctor I’ve ever seen. They informed me of the long-term effects of medications and the importance of routine cardiovascular check-ups. Also, they wouldn’t prescribe more than 5 mg of Adderall (even though I had been prescribed 30-90 mg a day for most of my life) until I completed a medical check-up with blood pressure and blood test results.”

Corporate telepsychiatry may fill an important void and provide care to many people who have been unable to access traditional treatment. Something, however, has to account for the fact that care is more affordable through startups than through traditional psychiatric practices. Startups have expensive technological and infrastructure costs and added layers of administration. This translates to either higher volumes with shorter appointments, less compensation for prescribers, or both. How this will affect the future of psychiatric care remains to be seen.

Dr. Miller, is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When Sue W’s mother died in 2018, she struggled terribly. She was already seeing a psychotherapist and was taking duloxetine, prescribed by her primary care physician. But her grief was profound, and her depression became paralyzing. She needed to see a psychiatrist, and there were many available in or near her hometown, a Connecticut suburb of New York City, but neither Sue, her therapist, nor her primary care doctor could find a psychiatrist who participated with her insurance. Finally, she was given the name of a psychiatrist in Manhattan who practiced online, and she made an appointment on the Skypiatrist (a telepsychiatry group founded in 2016) website.

“I hesitated about it at first,” Sue said. “The doctor was nice, and I liked the convenience. Appointments were 15 minutes long, although the first session was longer. He focused on the medications, which was okay because I already have a therapist. And it was really easy. I made appointments on their website and I saw the doctor through the same site, and I really liked that I could send him messages.” The psychiatrist was responsive when Sue had trouble coming off duloxetine, and he gave her instructions for a slower taper. The treatment was affordable and accessible, and she got better.

When you also consider that many private-practice psychiatrists do not participate with insurance panels, online companies that do accept insurance may add value, convenience, and access.

Cerebral, the largest online psychiatric service in the country, began seeing patients in January 2020, offering medications and psychotherapy. They participate with a number of commercial insurers, and this varies by state, but not with Medicaid or Medicare. Patients pay a monthly fee, and an initial 30-minute medication evaluation session is conducted, often with a nurse practitioner. They advertise wait times of less than 7 days.

Another company, Done, offers treatment specifically for ADHD. They don’t accept insurance for appointments; patients must submit their own claims for reimbursement. Their pricing structure involves a fee of $199 for the first month, then $79 a month thereafter, which does not include medications. Hims – another online company – targets men with a variety of health issues, including mental health problems.

Some of these internet companies have been in the news recently for concerns related to quality of care and prescribing practices. A The Wall Street Journal article of March 26, 2022, quoted clinicians who had previously worked for Cerebral and Done who left because they felt pressured to see patients quickly and to prescribe stimulants. Not all of the prescribers were unhappy, however. Yina Cruz-Harris, a nurse practitioner at Done who has a doctorate in nursing practice, said that she manages 2,300 patients with ADHD for Done. Virtually all are on stimulants. She renews each patient’s monthly prescription from her New Jersey home, based mostly on online forms filled out by the patients. She’s fast, doing two renewals per minute, and Done pays her almost $10 per patient, working out to around $20,000 in monthly earnings.

In May, the Department of Justice began looking into Cerebral’s practices around controlled substances and more recently, Cerebral has been in the news for complaints from patients that they have been unable to reach their prescribers when problems arise. Some pharmacy chains have refused to fill prescriptions for controlled medications from online telehealth providers, and some online providers, including Cerebral, are no longer prescribing controlled substances. A front-page The Wall Street Journal article on Aug. 19, 2022, told the story of a man with a history of addiction who was prescribed stimulants after a brief appointment with a prescriber at Done. Family and friends in his sober house believe that the stimulants triggered a relapse, and he died of an opioid overdose.

During the early days of the pandemic, nonemergency psychiatric care was shut down and we all became virtual psychiatrists. Many of us saw new patients and prescribed controlled medications to people we had never met in real life.

“John Brown,” MD, PhD, spoke with me on the condition that I don’t use his real name or the name of the practice he left. He was hired by a traditional group practice with a multidisciplinary staff and several offices in his state. Most of the clinicians worked part time and were contractual employees, and Dr. Brown was hired to develop a specialty service. He soon learned that the practice – which participates with a number of insurance plans – was not financially stable, and it was acquired by an investment firm with no medical experience.

“They wanted everyone to work 40-hour weeks and see 14 patients a day, including 3-4 new patients, and suddenly everyone was overextended and exhausted. Overnight, most of the therapists left, and they hired nurse practitioners to replace many of the psychiatrists. People weren’t getting good care.” While this was not a telepsychiatry startup, it was a corporate takeover of a traditional practice that was unable to remain financially solvent while participating with insurance panels.