User login

FDA approves first targeted treatment for rare DMD mutation

, the agency has announced.

This particular mutation of the DMD gene “is amenable to exon 45 skipping,” the FDA noted in a press release. The agency added that this is its first approval of a targeted treatment for patients with the mutation.

“Developing drugs designed for patients with specific mutations is a critical part of personalized medicine,” Eric Bastings, MD, deputy director of the Office of Neuroscience at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

The approval was based on results from a 43-person randomized controlled trial. Patients who received casimersen had a greater increase in production of the muscle-fiber protein dystrophin compared with their counterparts who received placebo.

Approved – with cautions

The FDA noted that DMD prevalence worldwide is about 1 in 3,600 boys – although it can also affect girls in rare cases. Symptoms of the disorder are commonly first observed around age 3 years but worsen steadily over time. DMD gene mutations lead to a decrease in dystrophin.

As reported by Medscape Medical News in August, the FDA approved viltolarsen (Viltepso, NS Pharma) for the treatment of DMD in patients with a confirmed mutation amenable to exon 53 skipping, following approval of golodirsen injection (Vyondys 53, Sarepta Therapeutics) for the same indication in December 2019.

The DMD gene mutation that is amenable to exon 45 skipping is present in about 8% of patients with DMD.

The trial that carried weight with the FDA included 43 male participants with DMD aged 7-20 years. All were confirmed to have the exon 45-skipping gene mutation and all were randomly assigned 2:1 to received IV casimersen 30 mg/kg or matching placebo.

Results showed that, between baseline and 48 weeks post treatment, the casimersen group showed a significantly higher increase in levels of dystrophin protein than in the placebo group.

Upper respiratory tract infections, fever, joint and throat pain, headache, and cough were the most common adverse events experienced by the active-treatment group.

Although the clinical studies assessing casimersen did not show any reports of kidney toxicity, the adverse event was observed in some nonclinical studies. Therefore, clinicians should monitor kidney function in any patient receiving this treatment, the FDA recommended.

Overall, “the FDA has concluded that the data submitted by the applicant demonstrated an increase in dystrophin production that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit” in this patient population, the agency said in its press release.

However, it noted that definitive clinical benefits such as improved motor function were not “established.”

“In making this decision, the FDA considered the potential risks associated with the drug, the life-threatening and debilitating nature of the disease, and the lack of [other] available therapy,” the agency said.

It added that the manufacturer is currently conducting a multicenter study focused on the safety and efficacy of the drug in ambulatory patients with DMD.

The FDA approved casimersen using its Accelerated Approval pathway, granted Fast Track and Priority Review designations to its applications, and gave the treatment Orphan Drug designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the agency has announced.

This particular mutation of the DMD gene “is amenable to exon 45 skipping,” the FDA noted in a press release. The agency added that this is its first approval of a targeted treatment for patients with the mutation.

“Developing drugs designed for patients with specific mutations is a critical part of personalized medicine,” Eric Bastings, MD, deputy director of the Office of Neuroscience at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

The approval was based on results from a 43-person randomized controlled trial. Patients who received casimersen had a greater increase in production of the muscle-fiber protein dystrophin compared with their counterparts who received placebo.

Approved – with cautions

The FDA noted that DMD prevalence worldwide is about 1 in 3,600 boys – although it can also affect girls in rare cases. Symptoms of the disorder are commonly first observed around age 3 years but worsen steadily over time. DMD gene mutations lead to a decrease in dystrophin.

As reported by Medscape Medical News in August, the FDA approved viltolarsen (Viltepso, NS Pharma) for the treatment of DMD in patients with a confirmed mutation amenable to exon 53 skipping, following approval of golodirsen injection (Vyondys 53, Sarepta Therapeutics) for the same indication in December 2019.

The DMD gene mutation that is amenable to exon 45 skipping is present in about 8% of patients with DMD.

The trial that carried weight with the FDA included 43 male participants with DMD aged 7-20 years. All were confirmed to have the exon 45-skipping gene mutation and all were randomly assigned 2:1 to received IV casimersen 30 mg/kg or matching placebo.

Results showed that, between baseline and 48 weeks post treatment, the casimersen group showed a significantly higher increase in levels of dystrophin protein than in the placebo group.

Upper respiratory tract infections, fever, joint and throat pain, headache, and cough were the most common adverse events experienced by the active-treatment group.

Although the clinical studies assessing casimersen did not show any reports of kidney toxicity, the adverse event was observed in some nonclinical studies. Therefore, clinicians should monitor kidney function in any patient receiving this treatment, the FDA recommended.

Overall, “the FDA has concluded that the data submitted by the applicant demonstrated an increase in dystrophin production that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit” in this patient population, the agency said in its press release.

However, it noted that definitive clinical benefits such as improved motor function were not “established.”

“In making this decision, the FDA considered the potential risks associated with the drug, the life-threatening and debilitating nature of the disease, and the lack of [other] available therapy,” the agency said.

It added that the manufacturer is currently conducting a multicenter study focused on the safety and efficacy of the drug in ambulatory patients with DMD.

The FDA approved casimersen using its Accelerated Approval pathway, granted Fast Track and Priority Review designations to its applications, and gave the treatment Orphan Drug designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the agency has announced.

This particular mutation of the DMD gene “is amenable to exon 45 skipping,” the FDA noted in a press release. The agency added that this is its first approval of a targeted treatment for patients with the mutation.

“Developing drugs designed for patients with specific mutations is a critical part of personalized medicine,” Eric Bastings, MD, deputy director of the Office of Neuroscience at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

The approval was based on results from a 43-person randomized controlled trial. Patients who received casimersen had a greater increase in production of the muscle-fiber protein dystrophin compared with their counterparts who received placebo.

Approved – with cautions

The FDA noted that DMD prevalence worldwide is about 1 in 3,600 boys – although it can also affect girls in rare cases. Symptoms of the disorder are commonly first observed around age 3 years but worsen steadily over time. DMD gene mutations lead to a decrease in dystrophin.

As reported by Medscape Medical News in August, the FDA approved viltolarsen (Viltepso, NS Pharma) for the treatment of DMD in patients with a confirmed mutation amenable to exon 53 skipping, following approval of golodirsen injection (Vyondys 53, Sarepta Therapeutics) for the same indication in December 2019.

The DMD gene mutation that is amenable to exon 45 skipping is present in about 8% of patients with DMD.

The trial that carried weight with the FDA included 43 male participants with DMD aged 7-20 years. All were confirmed to have the exon 45-skipping gene mutation and all were randomly assigned 2:1 to received IV casimersen 30 mg/kg or matching placebo.

Results showed that, between baseline and 48 weeks post treatment, the casimersen group showed a significantly higher increase in levels of dystrophin protein than in the placebo group.

Upper respiratory tract infections, fever, joint and throat pain, headache, and cough were the most common adverse events experienced by the active-treatment group.

Although the clinical studies assessing casimersen did not show any reports of kidney toxicity, the adverse event was observed in some nonclinical studies. Therefore, clinicians should monitor kidney function in any patient receiving this treatment, the FDA recommended.

Overall, “the FDA has concluded that the data submitted by the applicant demonstrated an increase in dystrophin production that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit” in this patient population, the agency said in its press release.

However, it noted that definitive clinical benefits such as improved motor function were not “established.”

“In making this decision, the FDA considered the potential risks associated with the drug, the life-threatening and debilitating nature of the disease, and the lack of [other] available therapy,” the agency said.

It added that the manufacturer is currently conducting a multicenter study focused on the safety and efficacy of the drug in ambulatory patients with DMD.

The FDA approved casimersen using its Accelerated Approval pathway, granted Fast Track and Priority Review designations to its applications, and gave the treatment Orphan Drug designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeated ketamine infusions linked to rapid relief of PTSD

Repeated intravenous infusions of ketamine provide rapid relief for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, new research suggests.

In what investigators are calling the first randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic PTSD, 30 patients received six infusions of ketamine or midazolam (used as a psychoactive placebo) over 2 consecutive weeks.

Between baseline and week 2, those receiving ketamine showed significantly greater improvement than those receiving midazolam. Total scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) for the first group were almost 12 points lower than the latter group at week 2, meeting the study’s primary outcome measure.

In addition, 67% vs. 20% of the patients, respectively, were considered to be treatment responders; time to loss of response for those in the ketamine group was 28 days.

Although the overall findings were as expected, “what was surprising was how robust the results were,” lead author Adriana Feder, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization.

It was also a bit surprising that, in a study of just 30 participants, “we were able to show such a clear difference” between the two treatment groups, said Dr. Feder, who is also a coinventor on issued patents for the use of ketamine as therapy for PTSD, and codirector of the Ehrenkranz Lab for the Study of Human Resilience at Mount Sinai.

The findings were published online Jan. 5 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Unmet need

Ketamine is a glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for anesthetic use in 1970. It has also been shown to be effective for treatment-resistant depression.

PTSD has a lifetime prevalence of about 6% in the United States. “While trauma-focused psychotherapies have the most empirical support, they are limited by significant rates of nonresponse, partial response, and treatment dropout,” the investigators write. Also, there are “few available pharmacotherapies for PTSD, and their efficacy is insufficient,” they add.

“There’s a real need for new treatment interventions that are effective for PTSD and also work rapidly, because it can take weeks to months for currently available treatments to work for PTSD,” Dr. Feder said.

The researchers previously conducted a “proof-of-concept” randomized controlled trial of single infusions of ketamine for chronic PTSD. Results published in 2014 in JAMA Psychiatry showed significant reduction in PTSD symptoms 24 hours after infusion.

For the current study, the investigative team wanted to assess whether ketamine was viable as a longer-term treatment.

“We were encouraged by our initial promising findings” of the earlier trial, Dr. Feder said. “We wanted to do the second study to see if ketamine really works for PTSD, to see if we could replicate the rapid improvement and also examine whether a course of six infusions over 2 weeks could maintain the improvement.”

Thirty patients (aged 18-70; mean age, 39 years) with chronic PTSD from civilian or military trauma were enrolled (mean PTSD duration, 15 years).

The most cited primary trauma was sexual assault or molestation (n = 13), followed by physical assault or abuse (n = 8), witnessing a violent assault or death (n = 4), witnessing the 9/11 attacks (n = 3), and combat exposure (n = 2).

During the 2-week treatment phase, half of the patients were randomly assigned to receive six infusions of ketamine hydrochloride at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg (86.7% women; mean CAPS-5 score, 42), while the other half received six infusions of midazolam at a dose of 0.045 mg/kg (66.7% women; mean CAPS-5 score, 40).

In addition to the primary outcome measure of 2-week changes on the CAPS-5, secondary outcomes included score changes on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R).

Treatment response was defined as a 30% or more improvement in symptoms on the CAPS-5. A number of measures were also used to assess potential treatment-related adverse events (AEs).

Safe, effective

Results showed significantly lower total CAPS-5 scores for the ketamine group vs. the midazolam group at week 1 (score difference, 8.8 points; P = .03) and at week 2 (score difference, 11.88 points; P = .004).

Those receiving ketamine also showed improvements in three of the four PTSD symptom clusters on the CAPS-5: avoidance (P < .0001), negative mood and cognitions (P = .02), and intrusions (P = .03). The fourth symptom cluster – arousal and reactivity – did not show a significant improvement.

In addition, the ketamine group showed significantly greater improvement scores on the MADRS at both week 1 and week 2.

Treatment response at 2 weeks was achieved by 10 members of the ketamine group and by three members of the midazolam group (P = .03).

Secondary analyses showed rapid improvement in the treatment responders within the ketamine group, with a mean change of 26 points on the total IES-R score between baseline and 24 hours after their first infusion, and a mean change of 13.4 points on the MADRS total past-24-hour score, a 53% improvement on average.

“A response at 2 weeks is very rapid but they got better sometimes within the first day,” Dr. Feder noted.

There were no serious AEs reported. Although some dissociative symptoms occurred during ketamine infusions, with the highest levels reported at the end of the infusion, these symptoms had resolved by the next assessment, conducted 2 hours after infusion.

The most frequently reported AE in the ketamine group, compared with midazolam, after the start of infusions was blurred vision (53% vs. 0%), followed by dizziness (33% vs. 13%), fatigue (33% vs. 87%), headache (27% vs. 13%), and nausea or vomiting (20% vs. 7%).

‘Large-magnitude improvement’

The overall findings show that, in this patient population, “repeated intravenous ketamine infusions administered over 2 weeks were associated with a large-magnitude, clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms,” the investigators write.

The results “were very satisfying,” added Dr. Feder. “It was heartening also to hear what some of the participants would say. Some told us about how their symptoms and feelings had changed during the course of treatment with ketamine, where they felt stronger and better able to cope with their trauma and memories.”

She noted, however, that this was not a study designed to specifically assess ketamine in treatment-resistant PTSD. “Some patients had had multiple treatments before that hadn’t worked, while others had not received treatment before. Efficacy for treatment-resistant PTSD is an important question for future research,” Dr. Feder said.

Other areas worth future exploration include treatment efficacy in patients with different types of trauma and whether outcomes can last longer in patients receiving ketamine plus psychotherapy treatment, she noted.

“I don’t want to ignore the fact that currently available treatments work for a number of people with chronic PTSD. But because there are many more for whom [the treatments] don’t work, or they’re insufficiently helped by those treatments, this is certainly one potentially very promising approach that can be added” to a clinician’s toolbox, Dr. Feder said.

Speaks to clinical utility

Commenting for this news organization, Gerard Sanacora, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, called this a “very solid and well-designed” study.

“It definitely builds on what’s been found in the past, but it’s a critical piece of information speaking to the clinical utility of this treatment for PTSD,” said Dr. Sanacora, who is also director of the Yale Depression Research Program and was not involved with the current research.

He agreed with the investigators that PTSD has long been a condition that is difficult to treat.

“It’s an area that has a great unmet need for treatment options. Beyond that, as ketamine is becoming more widely used, there’s increasing demand for off-label uses. This [study] actually provides some evidence that there may be efficacy there,” Dr. Sanacora said.

Although he cautioned that this was a small study, and thus further research with a larger patient population will be needed, it provides a compelling foundation to build upon.

“This study provides clear evidence to support a larger study to really give a definitive statement on the efficacy and safety of its use for PTSD. I don’t think this is the study that provides that definitive evidence, but it is a very strong indication, and it very strongly supports the initiation of a large study to address that,” said Dr. Sanacora.

He noted that, although he’s used the term “cautious optimism” for studies in the past, he has “real optimism” that ketamine will be effective for PTSD based on the results of this current study.

“We still need some more data to really convince us of that before we can say with any clear statement that it is effective and safe, but I’m very optimistic,” Dr. Sanacora concluded.

The study was funded by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Mount Sinai Innovation Partners and the Mount Sinai i3 Accelerator, Gerald and Glenda Greenwald, and the Ehrenkranz Laboratory for Human Resilience. Dr. Feder is a coinventor on issued patents for the use of ketamine as therapy for PTSD. A list of all disclosures for the other study authors are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeated intravenous infusions of ketamine provide rapid relief for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, new research suggests.

In what investigators are calling the first randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic PTSD, 30 patients received six infusions of ketamine or midazolam (used as a psychoactive placebo) over 2 consecutive weeks.

Between baseline and week 2, those receiving ketamine showed significantly greater improvement than those receiving midazolam. Total scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) for the first group were almost 12 points lower than the latter group at week 2, meeting the study’s primary outcome measure.

In addition, 67% vs. 20% of the patients, respectively, were considered to be treatment responders; time to loss of response for those in the ketamine group was 28 days.

Although the overall findings were as expected, “what was surprising was how robust the results were,” lead author Adriana Feder, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization.

It was also a bit surprising that, in a study of just 30 participants, “we were able to show such a clear difference” between the two treatment groups, said Dr. Feder, who is also a coinventor on issued patents for the use of ketamine as therapy for PTSD, and codirector of the Ehrenkranz Lab for the Study of Human Resilience at Mount Sinai.

The findings were published online Jan. 5 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Unmet need

Ketamine is a glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for anesthetic use in 1970. It has also been shown to be effective for treatment-resistant depression.

PTSD has a lifetime prevalence of about 6% in the United States. “While trauma-focused psychotherapies have the most empirical support, they are limited by significant rates of nonresponse, partial response, and treatment dropout,” the investigators write. Also, there are “few available pharmacotherapies for PTSD, and their efficacy is insufficient,” they add.

“There’s a real need for new treatment interventions that are effective for PTSD and also work rapidly, because it can take weeks to months for currently available treatments to work for PTSD,” Dr. Feder said.

The researchers previously conducted a “proof-of-concept” randomized controlled trial of single infusions of ketamine for chronic PTSD. Results published in 2014 in JAMA Psychiatry showed significant reduction in PTSD symptoms 24 hours after infusion.

For the current study, the investigative team wanted to assess whether ketamine was viable as a longer-term treatment.

“We were encouraged by our initial promising findings” of the earlier trial, Dr. Feder said. “We wanted to do the second study to see if ketamine really works for PTSD, to see if we could replicate the rapid improvement and also examine whether a course of six infusions over 2 weeks could maintain the improvement.”

Thirty patients (aged 18-70; mean age, 39 years) with chronic PTSD from civilian or military trauma were enrolled (mean PTSD duration, 15 years).

The most cited primary trauma was sexual assault or molestation (n = 13), followed by physical assault or abuse (n = 8), witnessing a violent assault or death (n = 4), witnessing the 9/11 attacks (n = 3), and combat exposure (n = 2).

During the 2-week treatment phase, half of the patients were randomly assigned to receive six infusions of ketamine hydrochloride at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg (86.7% women; mean CAPS-5 score, 42), while the other half received six infusions of midazolam at a dose of 0.045 mg/kg (66.7% women; mean CAPS-5 score, 40).

In addition to the primary outcome measure of 2-week changes on the CAPS-5, secondary outcomes included score changes on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R).

Treatment response was defined as a 30% or more improvement in symptoms on the CAPS-5. A number of measures were also used to assess potential treatment-related adverse events (AEs).

Safe, effective

Results showed significantly lower total CAPS-5 scores for the ketamine group vs. the midazolam group at week 1 (score difference, 8.8 points; P = .03) and at week 2 (score difference, 11.88 points; P = .004).

Those receiving ketamine also showed improvements in three of the four PTSD symptom clusters on the CAPS-5: avoidance (P < .0001), negative mood and cognitions (P = .02), and intrusions (P = .03). The fourth symptom cluster – arousal and reactivity – did not show a significant improvement.

In addition, the ketamine group showed significantly greater improvement scores on the MADRS at both week 1 and week 2.

Treatment response at 2 weeks was achieved by 10 members of the ketamine group and by three members of the midazolam group (P = .03).

Secondary analyses showed rapid improvement in the treatment responders within the ketamine group, with a mean change of 26 points on the total IES-R score between baseline and 24 hours after their first infusion, and a mean change of 13.4 points on the MADRS total past-24-hour score, a 53% improvement on average.

“A response at 2 weeks is very rapid but they got better sometimes within the first day,” Dr. Feder noted.

There were no serious AEs reported. Although some dissociative symptoms occurred during ketamine infusions, with the highest levels reported at the end of the infusion, these symptoms had resolved by the next assessment, conducted 2 hours after infusion.

The most frequently reported AE in the ketamine group, compared with midazolam, after the start of infusions was blurred vision (53% vs. 0%), followed by dizziness (33% vs. 13%), fatigue (33% vs. 87%), headache (27% vs. 13%), and nausea or vomiting (20% vs. 7%).

‘Large-magnitude improvement’

The overall findings show that, in this patient population, “repeated intravenous ketamine infusions administered over 2 weeks were associated with a large-magnitude, clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms,” the investigators write.

The results “were very satisfying,” added Dr. Feder. “It was heartening also to hear what some of the participants would say. Some told us about how their symptoms and feelings had changed during the course of treatment with ketamine, where they felt stronger and better able to cope with their trauma and memories.”

She noted, however, that this was not a study designed to specifically assess ketamine in treatment-resistant PTSD. “Some patients had had multiple treatments before that hadn’t worked, while others had not received treatment before. Efficacy for treatment-resistant PTSD is an important question for future research,” Dr. Feder said.

Other areas worth future exploration include treatment efficacy in patients with different types of trauma and whether outcomes can last longer in patients receiving ketamine plus psychotherapy treatment, she noted.

“I don’t want to ignore the fact that currently available treatments work for a number of people with chronic PTSD. But because there are many more for whom [the treatments] don’t work, or they’re insufficiently helped by those treatments, this is certainly one potentially very promising approach that can be added” to a clinician’s toolbox, Dr. Feder said.

Speaks to clinical utility

Commenting for this news organization, Gerard Sanacora, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, called this a “very solid and well-designed” study.

“It definitely builds on what’s been found in the past, but it’s a critical piece of information speaking to the clinical utility of this treatment for PTSD,” said Dr. Sanacora, who is also director of the Yale Depression Research Program and was not involved with the current research.

He agreed with the investigators that PTSD has long been a condition that is difficult to treat.

“It’s an area that has a great unmet need for treatment options. Beyond that, as ketamine is becoming more widely used, there’s increasing demand for off-label uses. This [study] actually provides some evidence that there may be efficacy there,” Dr. Sanacora said.

Although he cautioned that this was a small study, and thus further research with a larger patient population will be needed, it provides a compelling foundation to build upon.

“This study provides clear evidence to support a larger study to really give a definitive statement on the efficacy and safety of its use for PTSD. I don’t think this is the study that provides that definitive evidence, but it is a very strong indication, and it very strongly supports the initiation of a large study to address that,” said Dr. Sanacora.

He noted that, although he’s used the term “cautious optimism” for studies in the past, he has “real optimism” that ketamine will be effective for PTSD based on the results of this current study.

“We still need some more data to really convince us of that before we can say with any clear statement that it is effective and safe, but I’m very optimistic,” Dr. Sanacora concluded.

The study was funded by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Mount Sinai Innovation Partners and the Mount Sinai i3 Accelerator, Gerald and Glenda Greenwald, and the Ehrenkranz Laboratory for Human Resilience. Dr. Feder is a coinventor on issued patents for the use of ketamine as therapy for PTSD. A list of all disclosures for the other study authors are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeated intravenous infusions of ketamine provide rapid relief for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, new research suggests.

In what investigators are calling the first randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic PTSD, 30 patients received six infusions of ketamine or midazolam (used as a psychoactive placebo) over 2 consecutive weeks.

Between baseline and week 2, those receiving ketamine showed significantly greater improvement than those receiving midazolam. Total scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) for the first group were almost 12 points lower than the latter group at week 2, meeting the study’s primary outcome measure.

In addition, 67% vs. 20% of the patients, respectively, were considered to be treatment responders; time to loss of response for those in the ketamine group was 28 days.

Although the overall findings were as expected, “what was surprising was how robust the results were,” lead author Adriana Feder, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization.

It was also a bit surprising that, in a study of just 30 participants, “we were able to show such a clear difference” between the two treatment groups, said Dr. Feder, who is also a coinventor on issued patents for the use of ketamine as therapy for PTSD, and codirector of the Ehrenkranz Lab for the Study of Human Resilience at Mount Sinai.

The findings were published online Jan. 5 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Unmet need

Ketamine is a glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for anesthetic use in 1970. It has also been shown to be effective for treatment-resistant depression.

PTSD has a lifetime prevalence of about 6% in the United States. “While trauma-focused psychotherapies have the most empirical support, they are limited by significant rates of nonresponse, partial response, and treatment dropout,” the investigators write. Also, there are “few available pharmacotherapies for PTSD, and their efficacy is insufficient,” they add.

“There’s a real need for new treatment interventions that are effective for PTSD and also work rapidly, because it can take weeks to months for currently available treatments to work for PTSD,” Dr. Feder said.

The researchers previously conducted a “proof-of-concept” randomized controlled trial of single infusions of ketamine for chronic PTSD. Results published in 2014 in JAMA Psychiatry showed significant reduction in PTSD symptoms 24 hours after infusion.

For the current study, the investigative team wanted to assess whether ketamine was viable as a longer-term treatment.

“We were encouraged by our initial promising findings” of the earlier trial, Dr. Feder said. “We wanted to do the second study to see if ketamine really works for PTSD, to see if we could replicate the rapid improvement and also examine whether a course of six infusions over 2 weeks could maintain the improvement.”

Thirty patients (aged 18-70; mean age, 39 years) with chronic PTSD from civilian or military trauma were enrolled (mean PTSD duration, 15 years).

The most cited primary trauma was sexual assault or molestation (n = 13), followed by physical assault or abuse (n = 8), witnessing a violent assault or death (n = 4), witnessing the 9/11 attacks (n = 3), and combat exposure (n = 2).

During the 2-week treatment phase, half of the patients were randomly assigned to receive six infusions of ketamine hydrochloride at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg (86.7% women; mean CAPS-5 score, 42), while the other half received six infusions of midazolam at a dose of 0.045 mg/kg (66.7% women; mean CAPS-5 score, 40).

In addition to the primary outcome measure of 2-week changes on the CAPS-5, secondary outcomes included score changes on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R).

Treatment response was defined as a 30% or more improvement in symptoms on the CAPS-5. A number of measures were also used to assess potential treatment-related adverse events (AEs).

Safe, effective

Results showed significantly lower total CAPS-5 scores for the ketamine group vs. the midazolam group at week 1 (score difference, 8.8 points; P = .03) and at week 2 (score difference, 11.88 points; P = .004).

Those receiving ketamine also showed improvements in three of the four PTSD symptom clusters on the CAPS-5: avoidance (P < .0001), negative mood and cognitions (P = .02), and intrusions (P = .03). The fourth symptom cluster – arousal and reactivity – did not show a significant improvement.

In addition, the ketamine group showed significantly greater improvement scores on the MADRS at both week 1 and week 2.

Treatment response at 2 weeks was achieved by 10 members of the ketamine group and by three members of the midazolam group (P = .03).

Secondary analyses showed rapid improvement in the treatment responders within the ketamine group, with a mean change of 26 points on the total IES-R score between baseline and 24 hours after their first infusion, and a mean change of 13.4 points on the MADRS total past-24-hour score, a 53% improvement on average.

“A response at 2 weeks is very rapid but they got better sometimes within the first day,” Dr. Feder noted.

There were no serious AEs reported. Although some dissociative symptoms occurred during ketamine infusions, with the highest levels reported at the end of the infusion, these symptoms had resolved by the next assessment, conducted 2 hours after infusion.

The most frequently reported AE in the ketamine group, compared with midazolam, after the start of infusions was blurred vision (53% vs. 0%), followed by dizziness (33% vs. 13%), fatigue (33% vs. 87%), headache (27% vs. 13%), and nausea or vomiting (20% vs. 7%).

‘Large-magnitude improvement’

The overall findings show that, in this patient population, “repeated intravenous ketamine infusions administered over 2 weeks were associated with a large-magnitude, clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms,” the investigators write.

The results “were very satisfying,” added Dr. Feder. “It was heartening also to hear what some of the participants would say. Some told us about how their symptoms and feelings had changed during the course of treatment with ketamine, where they felt stronger and better able to cope with their trauma and memories.”

She noted, however, that this was not a study designed to specifically assess ketamine in treatment-resistant PTSD. “Some patients had had multiple treatments before that hadn’t worked, while others had not received treatment before. Efficacy for treatment-resistant PTSD is an important question for future research,” Dr. Feder said.

Other areas worth future exploration include treatment efficacy in patients with different types of trauma and whether outcomes can last longer in patients receiving ketamine plus psychotherapy treatment, she noted.

“I don’t want to ignore the fact that currently available treatments work for a number of people with chronic PTSD. But because there are many more for whom [the treatments] don’t work, or they’re insufficiently helped by those treatments, this is certainly one potentially very promising approach that can be added” to a clinician’s toolbox, Dr. Feder said.

Speaks to clinical utility

Commenting for this news organization, Gerard Sanacora, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, called this a “very solid and well-designed” study.

“It definitely builds on what’s been found in the past, but it’s a critical piece of information speaking to the clinical utility of this treatment for PTSD,” said Dr. Sanacora, who is also director of the Yale Depression Research Program and was not involved with the current research.

He agreed with the investigators that PTSD has long been a condition that is difficult to treat.

“It’s an area that has a great unmet need for treatment options. Beyond that, as ketamine is becoming more widely used, there’s increasing demand for off-label uses. This [study] actually provides some evidence that there may be efficacy there,” Dr. Sanacora said.

Although he cautioned that this was a small study, and thus further research with a larger patient population will be needed, it provides a compelling foundation to build upon.

“This study provides clear evidence to support a larger study to really give a definitive statement on the efficacy and safety of its use for PTSD. I don’t think this is the study that provides that definitive evidence, but it is a very strong indication, and it very strongly supports the initiation of a large study to address that,” said Dr. Sanacora.

He noted that, although he’s used the term “cautious optimism” for studies in the past, he has “real optimism” that ketamine will be effective for PTSD based on the results of this current study.

“We still need some more data to really convince us of that before we can say with any clear statement that it is effective and safe, but I’m very optimistic,” Dr. Sanacora concluded.

The study was funded by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Mount Sinai Innovation Partners and the Mount Sinai i3 Accelerator, Gerald and Glenda Greenwald, and the Ehrenkranz Laboratory for Human Resilience. Dr. Feder is a coinventor on issued patents for the use of ketamine as therapy for PTSD. A list of all disclosures for the other study authors are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Microvascular injury of brain, olfactory bulb seen in COVID-19

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution

The investigators examined brains from a convenience sample of 19 patients (mean age, 50 years), all of whom died from COVID-19 between March and July 2020.

An 11.7-tesla scanner was used to obtain magnetic resonance microscopy images for 13 of the patients. In order to scan the olfactory bulb, the scanner was set at a resolution of 25 mcm; for the brain, it was set at 100 mcm.

Chromogenic immunostaining was used to assess brain abnormalities found in 10 of the patients. Multiplex fluorescence imaging was also used for some of the patients.

For 18 study participants, a histopathological brain examination was performed. In the patients who also had medical histories available to the researchers, five had mild respiratory syndrome, four had acute respiratory distress syndrome, two had pulmonary embolism, one had delirium, and three had unknown symptoms.

The punctate hyperintensities found on magnetic resonance microscopy were also found on histopathological exam. Collagen IV immunostaining showed a thinning in the basal lamina of endothelial cells in these areas.

In addition to congested blood vessels, punctate hypointensities were linked to areas of fibrinogen leakage – but also to “relatively intact vasculature,” the investigators reported.

“There was minimal perivascular inflammation in the specimens examined, but there was no vascular occlusion,” they added.

SARS-CoV-2 was also not found in any of the participants. “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that viral copy numbers were below the level of detection by our assays,” the researchers noted.

In 13 of the patients, hypertrophic astrocytes, macrophage infiltrates, and perivascular-activated microglia were found. Eight patients showed CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in spaces and lumens next to endothelial cells.

Finally, five patients showed activated microglia next to neurons. This is “suggestive of neuronophagia in the olfactory bulb, substantial nigra, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the pre-Bötzinger complex in the medulla, which is involved in the generation of spontaneous rhythmic breathing,” wrote the investigators.

In summary, vascular pathology was found in 10 cases, perivascular infiltrates were present in 13 cases, acute ischemic hypoxic neurons were present in 6 cases, and changes suggestive of neuronophagia were present in 5 cases.

The researchers noted that, although the study findings may be helpful when interpreting brain changes on MRI scan in this patient population, availability of clinical information for the participants was limited.

Therefore, “no conclusions can be drawn in relation to neurologic features of COVID-19,” they wrote.

The study was funded by NINDS. Dr. Lee and all but one of the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships; the remaining investigator reported having received grants from NINDS during the conduct of this study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution

The investigators examined brains from a convenience sample of 19 patients (mean age, 50 years), all of whom died from COVID-19 between March and July 2020.

An 11.7-tesla scanner was used to obtain magnetic resonance microscopy images for 13 of the patients. In order to scan the olfactory bulb, the scanner was set at a resolution of 25 mcm; for the brain, it was set at 100 mcm.

Chromogenic immunostaining was used to assess brain abnormalities found in 10 of the patients. Multiplex fluorescence imaging was also used for some of the patients.

For 18 study participants, a histopathological brain examination was performed. In the patients who also had medical histories available to the researchers, five had mild respiratory syndrome, four had acute respiratory distress syndrome, two had pulmonary embolism, one had delirium, and three had unknown symptoms.

The punctate hyperintensities found on magnetic resonance microscopy were also found on histopathological exam. Collagen IV immunostaining showed a thinning in the basal lamina of endothelial cells in these areas.

In addition to congested blood vessels, punctate hypointensities were linked to areas of fibrinogen leakage – but also to “relatively intact vasculature,” the investigators reported.

“There was minimal perivascular inflammation in the specimens examined, but there was no vascular occlusion,” they added.

SARS-CoV-2 was also not found in any of the participants. “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that viral copy numbers were below the level of detection by our assays,” the researchers noted.

In 13 of the patients, hypertrophic astrocytes, macrophage infiltrates, and perivascular-activated microglia were found. Eight patients showed CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in spaces and lumens next to endothelial cells.

Finally, five patients showed activated microglia next to neurons. This is “suggestive of neuronophagia in the olfactory bulb, substantial nigra, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the pre-Bötzinger complex in the medulla, which is involved in the generation of spontaneous rhythmic breathing,” wrote the investigators.

In summary, vascular pathology was found in 10 cases, perivascular infiltrates were present in 13 cases, acute ischemic hypoxic neurons were present in 6 cases, and changes suggestive of neuronophagia were present in 5 cases.

The researchers noted that, although the study findings may be helpful when interpreting brain changes on MRI scan in this patient population, availability of clinical information for the participants was limited.

Therefore, “no conclusions can be drawn in relation to neurologic features of COVID-19,” they wrote.

The study was funded by NINDS. Dr. Lee and all but one of the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships; the remaining investigator reported having received grants from NINDS during the conduct of this study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution

The investigators examined brains from a convenience sample of 19 patients (mean age, 50 years), all of whom died from COVID-19 between March and July 2020.

An 11.7-tesla scanner was used to obtain magnetic resonance microscopy images for 13 of the patients. In order to scan the olfactory bulb, the scanner was set at a resolution of 25 mcm; for the brain, it was set at 100 mcm.

Chromogenic immunostaining was used to assess brain abnormalities found in 10 of the patients. Multiplex fluorescence imaging was also used for some of the patients.

For 18 study participants, a histopathological brain examination was performed. In the patients who also had medical histories available to the researchers, five had mild respiratory syndrome, four had acute respiratory distress syndrome, two had pulmonary embolism, one had delirium, and three had unknown symptoms.

The punctate hyperintensities found on magnetic resonance microscopy were also found on histopathological exam. Collagen IV immunostaining showed a thinning in the basal lamina of endothelial cells in these areas.

In addition to congested blood vessels, punctate hypointensities were linked to areas of fibrinogen leakage – but also to “relatively intact vasculature,” the investigators reported.

“There was minimal perivascular inflammation in the specimens examined, but there was no vascular occlusion,” they added.

SARS-CoV-2 was also not found in any of the participants. “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that viral copy numbers were below the level of detection by our assays,” the researchers noted.

In 13 of the patients, hypertrophic astrocytes, macrophage infiltrates, and perivascular-activated microglia were found. Eight patients showed CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in spaces and lumens next to endothelial cells.

Finally, five patients showed activated microglia next to neurons. This is “suggestive of neuronophagia in the olfactory bulb, substantial nigra, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the pre-Bötzinger complex in the medulla, which is involved in the generation of spontaneous rhythmic breathing,” wrote the investigators.

In summary, vascular pathology was found in 10 cases, perivascular infiltrates were present in 13 cases, acute ischemic hypoxic neurons were present in 6 cases, and changes suggestive of neuronophagia were present in 5 cases.

The researchers noted that, although the study findings may be helpful when interpreting brain changes on MRI scan in this patient population, availability of clinical information for the participants was limited.

Therefore, “no conclusions can be drawn in relation to neurologic features of COVID-19,” they wrote.

The study was funded by NINDS. Dr. Lee and all but one of the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships; the remaining investigator reported having received grants from NINDS during the conduct of this study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘She’s not a real doctor, she’s a psych doctor’

During a particularly hectic day, Janeni Nayagan, MD, a first-year resident in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Cooper University Hospital, Camden, N.J., was taken aback – but not surprised – by a patient’s comment.

In the middle of an emergent situation, she overheard a patient say that Dr. Nayagan wasn’t a “real doctor, she’s a psych doctor.”

“When it happened, I wasn’t particularly angry. It was something I knew I would hear eventually because I’d heard of others experiencing it,” Dr. Nayagan said in an interview. “Psychiatry is one of the fields of medicine that is often questioned in terms of legitimacy, and I knew that when I applied for psych residency,” she said.

Nevertheless, she wrote a post about the incident on Twitter, and she discovered she was far from alone. She posted her original tweet at the start of a night shift and was surprised by the number of responses when she opened her account the next day.

So far, Dr. Nayagan’s initial tweet has garnered 86 replies, 960 likes, and 35 retweets. Some clinicians reported similar experiences from both patients and colleagues, and others offered advice on how to handle such slights.

“There were a lot from people within mental health, but I also received responses from pathologists, radiologists, and others. I didn’t realize how much this experience pervaded through medicine, where a certain specialty would be told: You’re not a real doctor. So it was nice having that support,” Dr. Nayagan said.

Dr. Nayagan noted that psychiatrists encounter “specialty bias” to a greater extent than other medical professionals, and it can be a deterrent for medical students when considering psychiatry as a career path.

“It is something that has been around for a while, but it’s surprising that it’s still prevalent in 2020,” Dr. Nayagan said.

‘Busting the myth’

This type of bias is real, agreed Kaz Nelson, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and vice chair for education at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and former director of the psychiatry residency program at the school for 8 years.

She said there is “discrimination” toward psychiatrists, but noted that the problem is improving.

“I think we’re better now than 2 years or 5 years or 10 years ago, so we’re heading in the right direction. But ,” Dr. Nelson said in an interview.

“Psychiatrists have the same robust biomedical training as all specialties. They completed medical school and have this additional specialty and in some cases subspecialty training that is comprehensive of biology, psychology, and social components. We call that using a biopsychosocial model,” she said.

However, she noted that, when talking with students about the field of psychiatry, there’s an awareness “that perhaps we aren’t wearing a white coat” or a stethoscope around the neck.

“That gets translated as, You are giving up medicine – you got this medical training, and you’re not using it. And I have to bust that myth and convey that it really is a privilege to be able to integrate these aspects of knowledge and expertise. It’s in no way giving up medicine – we’re practicing medicine every single day,” said Dr. Nelson.

Remnants of stigma remain

Tristan Gorrindo, MD, deputy medical director and chief of the division of education at the American Psychiatric Association, noted “remnants of stigma” still occur.

“In my mind, it’s really a misunderstanding of the relationship between mental health and physical health,” Dr. Gorrindo said in an interview.

“There’s still this notion that holds over from an old belief that the mind and the body are separate. However, the contemporary thinking in most of modern medicine is that mental illness and physical illness are really one and the same, and they influence each other in a very dynamic way all the time,” he said.

“Psychiatrists stand in both worlds. They’re really the bridge to both the psychiatric and physical aspects,” he added.

Dr. Gorrindo agreed with Dr. Nelson that this understanding has become more prevalent during past few decades.

“Within society, it’s become much more acceptable for people to talk about their mental illness and seek treatment. In a way, shedding daylight on this issue has allowed psychiatry to step forward and demonstrate its value,” he said.

“I think over time we’re going to see that stigma or specialty bias become an anachronism that will fall by the wayside as we see psychiatry more broadly integrated and accepted within the entire house of medicine,” said Dr. Gorrindo.

Taking a toll

Although some responders on Twitter advised Dr. Nayagan and other psychiatrists to “educate with a smile” when faced with specialty discrimination, Dr. Nelson noted that it’s important to recognize that experiencing “microaggressions” takes a toll.

“Anytime you’re given a signal that you aren’t really a physician or you’re not doing a real job, whether it’s based on race, gender, ethnicity, or being a psychiatrist, there is a cost. I’d say, know what you’re doing and hold your head up high, but recognize that there’s a cost for which you may need community and support from colleagues,” she said.

“Together, our culture is changing, and the future is bright. But it’s a little bit of an oversimplification to say, ‘Just brush it off.’ We must recognize that there’s a burden that comes from those forms of exclusion,” Dr. Nelson concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

During a particularly hectic day, Janeni Nayagan, MD, a first-year resident in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Cooper University Hospital, Camden, N.J., was taken aback – but not surprised – by a patient’s comment.

In the middle of an emergent situation, she overheard a patient say that Dr. Nayagan wasn’t a “real doctor, she’s a psych doctor.”

“When it happened, I wasn’t particularly angry. It was something I knew I would hear eventually because I’d heard of others experiencing it,” Dr. Nayagan said in an interview. “Psychiatry is one of the fields of medicine that is often questioned in terms of legitimacy, and I knew that when I applied for psych residency,” she said.

Nevertheless, she wrote a post about the incident on Twitter, and she discovered she was far from alone. She posted her original tweet at the start of a night shift and was surprised by the number of responses when she opened her account the next day.

So far, Dr. Nayagan’s initial tweet has garnered 86 replies, 960 likes, and 35 retweets. Some clinicians reported similar experiences from both patients and colleagues, and others offered advice on how to handle such slights.

“There were a lot from people within mental health, but I also received responses from pathologists, radiologists, and others. I didn’t realize how much this experience pervaded through medicine, where a certain specialty would be told: You’re not a real doctor. So it was nice having that support,” Dr. Nayagan said.

Dr. Nayagan noted that psychiatrists encounter “specialty bias” to a greater extent than other medical professionals, and it can be a deterrent for medical students when considering psychiatry as a career path.

“It is something that has been around for a while, but it’s surprising that it’s still prevalent in 2020,” Dr. Nayagan said.

‘Busting the myth’

This type of bias is real, agreed Kaz Nelson, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and vice chair for education at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and former director of the psychiatry residency program at the school for 8 years.

She said there is “discrimination” toward psychiatrists, but noted that the problem is improving.

“I think we’re better now than 2 years or 5 years or 10 years ago, so we’re heading in the right direction. But ,” Dr. Nelson said in an interview.

“Psychiatrists have the same robust biomedical training as all specialties. They completed medical school and have this additional specialty and in some cases subspecialty training that is comprehensive of biology, psychology, and social components. We call that using a biopsychosocial model,” she said.

However, she noted that, when talking with students about the field of psychiatry, there’s an awareness “that perhaps we aren’t wearing a white coat” or a stethoscope around the neck.

“That gets translated as, You are giving up medicine – you got this medical training, and you’re not using it. And I have to bust that myth and convey that it really is a privilege to be able to integrate these aspects of knowledge and expertise. It’s in no way giving up medicine – we’re practicing medicine every single day,” said Dr. Nelson.

Remnants of stigma remain

Tristan Gorrindo, MD, deputy medical director and chief of the division of education at the American Psychiatric Association, noted “remnants of stigma” still occur.

“In my mind, it’s really a misunderstanding of the relationship between mental health and physical health,” Dr. Gorrindo said in an interview.

“There’s still this notion that holds over from an old belief that the mind and the body are separate. However, the contemporary thinking in most of modern medicine is that mental illness and physical illness are really one and the same, and they influence each other in a very dynamic way all the time,” he said.

“Psychiatrists stand in both worlds. They’re really the bridge to both the psychiatric and physical aspects,” he added.

Dr. Gorrindo agreed with Dr. Nelson that this understanding has become more prevalent during past few decades.

“Within society, it’s become much more acceptable for people to talk about their mental illness and seek treatment. In a way, shedding daylight on this issue has allowed psychiatry to step forward and demonstrate its value,” he said.

“I think over time we’re going to see that stigma or specialty bias become an anachronism that will fall by the wayside as we see psychiatry more broadly integrated and accepted within the entire house of medicine,” said Dr. Gorrindo.

Taking a toll

Although some responders on Twitter advised Dr. Nayagan and other psychiatrists to “educate with a smile” when faced with specialty discrimination, Dr. Nelson noted that it’s important to recognize that experiencing “microaggressions” takes a toll.

“Anytime you’re given a signal that you aren’t really a physician or you’re not doing a real job, whether it’s based on race, gender, ethnicity, or being a psychiatrist, there is a cost. I’d say, know what you’re doing and hold your head up high, but recognize that there’s a cost for which you may need community and support from colleagues,” she said.

“Together, our culture is changing, and the future is bright. But it’s a little bit of an oversimplification to say, ‘Just brush it off.’ We must recognize that there’s a burden that comes from those forms of exclusion,” Dr. Nelson concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

During a particularly hectic day, Janeni Nayagan, MD, a first-year resident in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Cooper University Hospital, Camden, N.J., was taken aback – but not surprised – by a patient’s comment.

In the middle of an emergent situation, she overheard a patient say that Dr. Nayagan wasn’t a “real doctor, she’s a psych doctor.”

“When it happened, I wasn’t particularly angry. It was something I knew I would hear eventually because I’d heard of others experiencing it,” Dr. Nayagan said in an interview. “Psychiatry is one of the fields of medicine that is often questioned in terms of legitimacy, and I knew that when I applied for psych residency,” she said.

Nevertheless, she wrote a post about the incident on Twitter, and she discovered she was far from alone. She posted her original tweet at the start of a night shift and was surprised by the number of responses when she opened her account the next day.

So far, Dr. Nayagan’s initial tweet has garnered 86 replies, 960 likes, and 35 retweets. Some clinicians reported similar experiences from both patients and colleagues, and others offered advice on how to handle such slights.

“There were a lot from people within mental health, but I also received responses from pathologists, radiologists, and others. I didn’t realize how much this experience pervaded through medicine, where a certain specialty would be told: You’re not a real doctor. So it was nice having that support,” Dr. Nayagan said.

Dr. Nayagan noted that psychiatrists encounter “specialty bias” to a greater extent than other medical professionals, and it can be a deterrent for medical students when considering psychiatry as a career path.

“It is something that has been around for a while, but it’s surprising that it’s still prevalent in 2020,” Dr. Nayagan said.

‘Busting the myth’

This type of bias is real, agreed Kaz Nelson, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and vice chair for education at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and former director of the psychiatry residency program at the school for 8 years.

She said there is “discrimination” toward psychiatrists, but noted that the problem is improving.

“I think we’re better now than 2 years or 5 years or 10 years ago, so we’re heading in the right direction. But ,” Dr. Nelson said in an interview.

“Psychiatrists have the same robust biomedical training as all specialties. They completed medical school and have this additional specialty and in some cases subspecialty training that is comprehensive of biology, psychology, and social components. We call that using a biopsychosocial model,” she said.

However, she noted that, when talking with students about the field of psychiatry, there’s an awareness “that perhaps we aren’t wearing a white coat” or a stethoscope around the neck.

“That gets translated as, You are giving up medicine – you got this medical training, and you’re not using it. And I have to bust that myth and convey that it really is a privilege to be able to integrate these aspects of knowledge and expertise. It’s in no way giving up medicine – we’re practicing medicine every single day,” said Dr. Nelson.

Remnants of stigma remain

Tristan Gorrindo, MD, deputy medical director and chief of the division of education at the American Psychiatric Association, noted “remnants of stigma” still occur.

“In my mind, it’s really a misunderstanding of the relationship between mental health and physical health,” Dr. Gorrindo said in an interview.

“There’s still this notion that holds over from an old belief that the mind and the body are separate. However, the contemporary thinking in most of modern medicine is that mental illness and physical illness are really one and the same, and they influence each other in a very dynamic way all the time,” he said.

“Psychiatrists stand in both worlds. They’re really the bridge to both the psychiatric and physical aspects,” he added.

Dr. Gorrindo agreed with Dr. Nelson that this understanding has become more prevalent during past few decades.

“Within society, it’s become much more acceptable for people to talk about their mental illness and seek treatment. In a way, shedding daylight on this issue has allowed psychiatry to step forward and demonstrate its value,” he said.

“I think over time we’re going to see that stigma or specialty bias become an anachronism that will fall by the wayside as we see psychiatry more broadly integrated and accepted within the entire house of medicine,” said Dr. Gorrindo.

Taking a toll

Although some responders on Twitter advised Dr. Nayagan and other psychiatrists to “educate with a smile” when faced with specialty discrimination, Dr. Nelson noted that it’s important to recognize that experiencing “microaggressions” takes a toll.

“Anytime you’re given a signal that you aren’t really a physician or you’re not doing a real job, whether it’s based on race, gender, ethnicity, or being a psychiatrist, there is a cost. I’d say, know what you’re doing and hold your head up high, but recognize that there’s a cost for which you may need community and support from colleagues,” she said.

“Together, our culture is changing, and the future is bright. But it’s a little bit of an oversimplification to say, ‘Just brush it off.’ We must recognize that there’s a burden that comes from those forms of exclusion,” Dr. Nelson concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

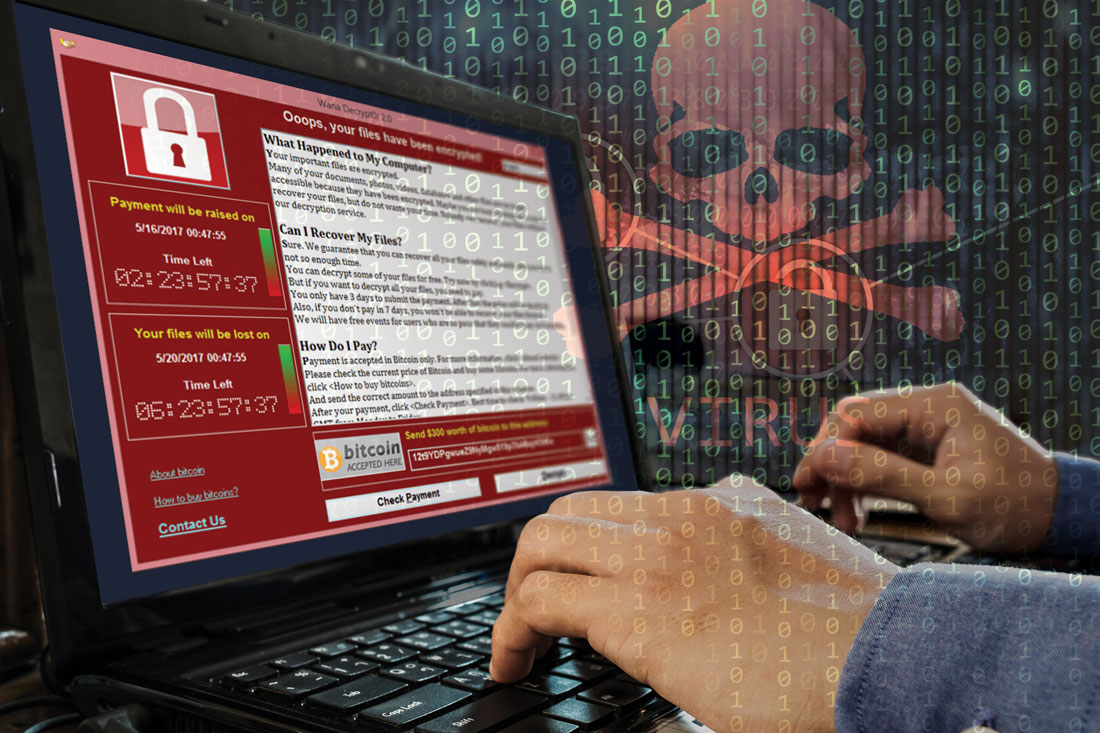

FBI warns of ‘imminent’ cyberattacks on U.S. hospitals

Amid recent reports of hackers targeting and blackmailing health care systems and even patients, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other agencies have issued warning of “imminent” cyberattacks on more U.S. hospitals.

A new report released by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, part of the Department of Homeland Security, noted that the FBI and the Department of Health & Human Services have “credible information of an increased and imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and health care providers.”

The agencies are urging “timely and reasonable precautions” to protect health care networks from these threats.

As reported, hackers accessed patient records at Vastaamo, Finland’s largest private psychotherapy system, and emailed some patients last month demanding €200 in bitcoin or else personal health data would be released online.

In June, the University of California, San Francisco, experienced an information technology (IT) “security incident” that led to the payout of $1.14 million to individuals responsible for a malware attack in exchange for the return of data.

In addition, last week, Sky Lakes Medical Center in Klamath Falls, Ore., released a statement in which it said there had been a ransomware attack on its computer systems. Although “there is no evidence that patient information has been compromised,” some of its systems are still down.

“We’re open for business, it’s just not business as usual,” Tom Hottman, public information officer at Sky Lakes, said in an interview.

Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at Columbia University, New York, said in an interview, “People have known for a long time that there are nefarious actors out there.” He said all health care systems should be prepared to deal with these problems.

“In the face of a warning from the FBI, I’d say that’s even more important now,” Dr. Appelbaum added.

‘Malicious cyber actors’

In the new CISA report, the agency noted that it, the FBI, and the HHS have been assessing “malicious cyber actors” targeting health care systems with malware loaders such as TrickBot and BazarLoader, which often lead to data theft, ransomware attacks, and service disruptions.

“The cybercriminal enterprise behind TrickBot, which is likely also the creator of BazarLoader malware, has continued to develop new functionality and tools, increasing the ease, speed, and profitability of victimization,” the report authors wrote.

Phishing campaigns often contain attachments with malware or links to malicious websites. “Loaders start the infection chain by distributing the payload,” the report noted. A backdoor mechanism is then installed on the victim’s device.

In addition to TrickBot and BazarLoader (or BazarBackdoor), the report discussed other malicious tools, including Ryuk and Conti, which are types of ransomware that can infect systems for hackers’ financial gain.

“These issues will be particularly challenging for organizations within the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, administrators will need to balance this risk when determining their cybersecurity investments,” the agencies wrote.

Dr. Appelbaum said his organization is taking the warning seriously.

“When the report first came out, I received emails from every system that I’m affiliated with warning about it and encouraging me as a member of the medical staff to take the usual prudent precautions,” such as not opening attachments or links from unknown sources, he said.

“The FBI warning has what seems like very reasonable advice, which is that every system should automatically back up their data off site in a separate system that’s differently accessible,” he added.

After a ransomware attack, the most recently entered information may not be backed up and could get lost, but “that’s a lot easier to deal with then losing access to all of your medical records,” said Dr. Appelbaum.

Ipsit Vahia, MD, medical director at the Institute for Technology and Psychiatry at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., noted that, in answer to the FBI warning, he has heard that many centers, including his own, are warning their clinicians not to open any email attachments at this time.

Recent attacks

UCSF issued a statement noting that malware detected in early June led to the encryption of “a limited number of servers” in its medical school, making them temporarily inaccessible.

“We do not currently believe patient medical records were exposed,” the university said in the statement.

It added that because the encrypted data were necessary for “some of the academic work” conducted at UCSF, they agreed to pay a portion of the ransom demand – about $1.14 million. The hackers then provided a tool that unlocked the encrypted data.

“We continue to cooperate with law enforcement and we appreciate everyone’s understanding that we are limited in what we can share while we continue our investigation,” the statement reads. UCSF declined a request for further comment.

At Sky Lakes Medical Center, computer systems are still down after its ransomware attack, including use of electronic medical records, but the Oregon-based health care system is still seeing patients.

They are “being interviewed old school,” with the admitting process being conducted on paper, “but patient care goes on,” said Mr. Hottman.

In addition to a teaching hospital, Sky Lakes comprises specialty and primary care clinics, including a cancer treatment center. All remain open to patients at this time.

Diagnostic imaging is also continuing, but “getting the image to a place it can be read” has become more complicated, said Mr. Hottman.

“We have some work-arounds in process, and a plan is being assembled that we think will be in place as early as this weekend so that we can get those images read starting next week,” he said.

In addition, “scheduling is a little clunky,” he reported. However, “we have an awesome staff with a good attitude, so there’s still a whole lot we can do.”

He also noted that his institution has reconfirmed that, as of Nov. 4, no patient data had been compromised.

‘Especially chilling’

Targeting hospitals through cyberattacks isn’t new. In 2017, the WannaCry virus affected more than 200,000 computers in 150 countries, including the operating system of the U.K. National Health Service. The cyberattack locked clinicians out of NHS patient records and other digital tools for 3 days.

Dr. Appelbaum noted that, as hospital systems become more dependent on the Internet and on electronic communications, they become more vulnerable to data breaches.

“I think it’s clear that there have been concerted efforts lately to undertake attacks on health care IT systems to either hold them hostage, as in a ransomware attack, or to download files and use that information for profit,” he said.

Still, Dr. Vahia noted that contacting patients directly, which occurred in the Finland data breach and blackmail scheme, is something new. It is “especially chilling” that individual psychiatric patients were targeted.

It’s difficult to overstate how big a deal this is, and we should be treating it with the appropriate level of urgency,” he said in an interview.

“It shows how badly things can go wrong when security is compromised; and it should make us take a step back and survey the world of digital health to gain recognition of how much risk there might be that we haven’t really understood before,” Dr. Vahia said.

Clinical tips

Asked whether he had any tips to share with clinicians, Mr. Hottman noted that the best time to have a plan is before something dire happens.

“I would make [the possibility of cyberattacks] part of the emergency preparedness program. What if you don’t have access to computers? What do you do?” It’s important to answer those questions prior to systems going down, he said.

Mr. Hottman reported that after a mechanical failure last year put their computer systems offline for a day, “we started putting all critical information on paper and in a binder,” including phone numbers for the state police.

Dr. Vahia noted that another important step for clinicians “is to just pause and take stock of how digitally dependent” health care is becoming. He also warned that precautions should be taken regarding wearables and apps, as well as for electronic medical records. He noted the importance of strong passwords and two-step verification processes.

Even with the risks, digital technology has had a major impact on health care efficiency. “It’s not perfect, the work is ongoing, and there are big questions that need to be addressed, but in the end, the ability of technology when used right and securely” leads to better patient care, he said.

John Torous, MD, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, agreed that digital health care is and will remain very important; but at the same time, security issues need proper attention.

“When you look back at medical hacks that have happened, there’s often a human error behind it. It’s rare for someone to break encryption. I think we have pretty darn good security, but we need to realize that sometimes errors will happen,” he said in an interview.

As an example, Dr. Torous, who is also chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Health and Technology Committee, cited phishing emails, which depend on a user clicking a link that can cause a virus to be downloaded into their network.

“You can be cautious, but it takes just one person to download an attachment with a virus in it” to cause disruptions, Dr. Torous said.

Telehealth implications

After its data breach, Vastaamo posted on its website a notice that video is never recorded during the centers’ telehealth sessions, and so patients need not worry that any videos could be leaked online.

Asked whether video is commonly recorded during telehealth sessions in the United States, Dr. Vahia said that he was not aware of sessions being recorded, especially because the amount of the data would be too great to store indefinitely.

Dr. Appelbaum agreed and said that, to his knowledge, no clinicians at Columbia University are recording telehealth sessions. He said that it would represent a privacy threat, and he noted that most health care providers “don’t have the time to go back and watch videos of their interactions with patients.”