User login

Flattening the curve: Viral graphic shows COVID-19 containment needs

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

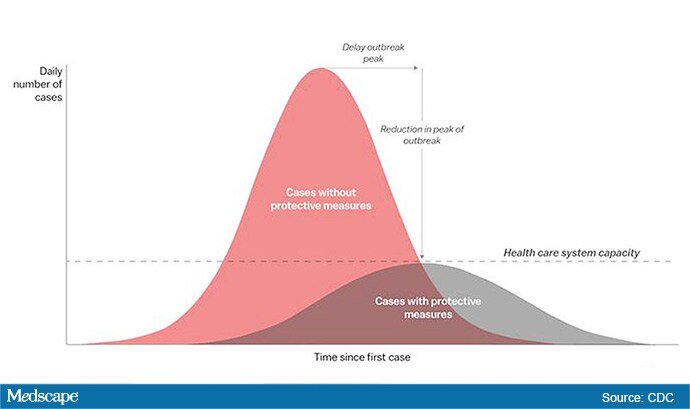

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

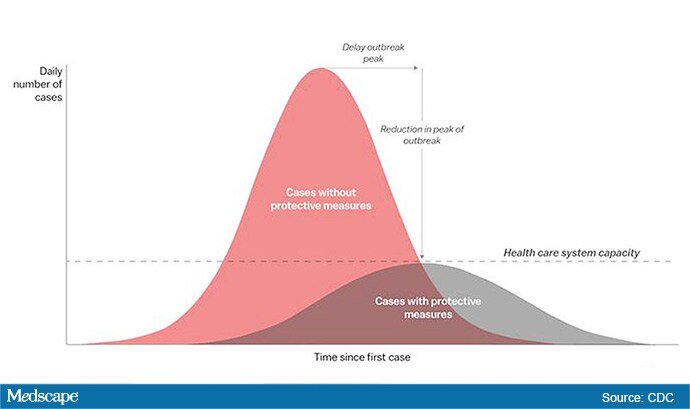

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

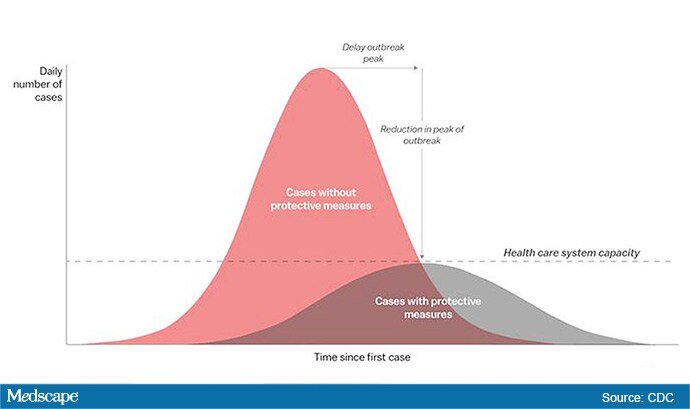

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

Bad behavior by medical trainees target of new proposal

Some instances of unprofessional behavior by medical trainees are universally deemed egregious and worthy of discipline — for example, looking up a friend’s medical data after HIPAA training.

Conversely, some professionalism lapses may be widely thought of as a teaching and consoling moment, such as the human error involved in forgetting a scheduled repositioning of a patient.

But between the extremes is a vast gray area. To deal with those cases appropriately, Jason Wasserman, PhD, and colleagues propose a new framework by which to judge each infraction.

The framework draws from “just culture” concepts used to evaluate medical errors, Wasserman, associate professor of biomedical science at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Rochester, Michigan, told Medscape Medical News. Such an approach takes into account the environment in which the error was made, the knowledge and intent of the person making the error, and the severity and consequences of the infraction so that trainees and institutions can learn from mistakes.

“Trainees by definition are not going to fully get it,” he explained. “By definition they’re not going to fully achieve professional expectations. So how can we respond to the things we need to respond to, but do it in a way that’s educational?”

Wasserman and coauthors’ framework for remediation, which they published February 20 in The New England Journal of Medicine, takes into account several questions: Was the expectation clear? Were there factors beyond the trainees› control? What were the trainees› intentions and did they understand the consequences? Did the person genuinely believe the action was inconsequential?

An example requiring discipline, the authors say, would be using a crib sheet during an exam. In that case the intent is clear, there is no defensible belief that the action is inconsequential, and there is a clear understanding the action is wrong.

But a response of “affirm, support, and advise” is more appropriate, for example, when a student’s alarm doesn’t go off after a power outage and they miss a mandatory meeting.

Wasserman points out that this framework won’t cover all situations.

“This is not an algorithm for answering your questions about what to do,” he said. “It’s an architecture for clarifying the discussion about that. It can really tease out all the threads that need to be considered to best respond to and correct the professionalism lapse, but do it in a way that is developmentally appropriate.”

A Core Competency

For two decades, professionalism has been considered a core competency of medical education. In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties formalized it as such. In 2013, the Association of American Medical Colleges formally required related professionalism competencies.

However, identifying lapses has operated largely on an “I-know-it-when-I-see-it” basis, leading to widely varying remediation practices judged by a small number of faculty members or administrators.

The ideas outlined by Wasserman and colleagues are “a terrific application of the ‘just-culture’ framework,” according to Nicole Treadway, MD, a first-year primary care resident at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

At Emory, discussions of professionalism start from day 1 of medical school and the subject is revisited throughout training in small groups, Treadway told Medscape Medical News.

But, she said, as the authors point out, definitions of unprofessionalism are not always clear and the examples the authors put forward help put lapses in context.

The framework also allows for looking at mistakes in light of the stress trainees encounter and the greater chance of making a professionalism error in those situations, she noted.

In her own work, she says, because she is juggling both inpatient and outpatient care, she is finding it is easy to get behind on correspondence or communicating lab results or having follow-up conversations.

Those delays could be seen as lapses in professionalism, but under this framework, there may be system solutions or training opportunities to consider.

“We do need this organizational architecture, and I think it could serve us well in really helping us identify and appropriately respond to what we see regarding professionalism,” she said.

Framework Helps Standardize Thinking

She said having a universal framework also helps because while standards of professionalism are easier to monitor in a single medical school, when students scatter to other hospitals for clinical training, those hospitals may have different professionalism standards.

Wasserman agrees, saying, “This could be easily adopted in any environment where people deal with professionalism lapses. I don’t even think it’s necessarily relegated to trainees. It’s a great way to think about any kind of lapses, just as hospitals think about medical errors.”

He said the next step is presenting the framework at various medical schools for feedback and research to see whether the framework improves processes.

Potential criticism, he said, might come from those who say such a construct avoids punishing students who make errors.

“There will always be people who say we’re pandering to medical students whenever we worry about the learning environment,” he said. “There are old-school purists who say when people screw up you should punish them.”

But he adds healthcare broadly has moved past that thinking.

“People recognized 20 years ago or more from the standpoint of improving healthcare systems and safety that is a bad strategy. You’ll never get error-free humans working in your system, and what you have to do is consider how the system is functioning and think about ways to optimize the system so people can be their best within it.”

Wasserman and Treadway have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some instances of unprofessional behavior by medical trainees are universally deemed egregious and worthy of discipline — for example, looking up a friend’s medical data after HIPAA training.

Conversely, some professionalism lapses may be widely thought of as a teaching and consoling moment, such as the human error involved in forgetting a scheduled repositioning of a patient.

But between the extremes is a vast gray area. To deal with those cases appropriately, Jason Wasserman, PhD, and colleagues propose a new framework by which to judge each infraction.

The framework draws from “just culture” concepts used to evaluate medical errors, Wasserman, associate professor of biomedical science at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Rochester, Michigan, told Medscape Medical News. Such an approach takes into account the environment in which the error was made, the knowledge and intent of the person making the error, and the severity and consequences of the infraction so that trainees and institutions can learn from mistakes.

“Trainees by definition are not going to fully get it,” he explained. “By definition they’re not going to fully achieve professional expectations. So how can we respond to the things we need to respond to, but do it in a way that’s educational?”

Wasserman and coauthors’ framework for remediation, which they published February 20 in The New England Journal of Medicine, takes into account several questions: Was the expectation clear? Were there factors beyond the trainees› control? What were the trainees› intentions and did they understand the consequences? Did the person genuinely believe the action was inconsequential?

An example requiring discipline, the authors say, would be using a crib sheet during an exam. In that case the intent is clear, there is no defensible belief that the action is inconsequential, and there is a clear understanding the action is wrong.

But a response of “affirm, support, and advise” is more appropriate, for example, when a student’s alarm doesn’t go off after a power outage and they miss a mandatory meeting.

Wasserman points out that this framework won’t cover all situations.

“This is not an algorithm for answering your questions about what to do,” he said. “It’s an architecture for clarifying the discussion about that. It can really tease out all the threads that need to be considered to best respond to and correct the professionalism lapse, but do it in a way that is developmentally appropriate.”

A Core Competency

For two decades, professionalism has been considered a core competency of medical education. In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties formalized it as such. In 2013, the Association of American Medical Colleges formally required related professionalism competencies.

However, identifying lapses has operated largely on an “I-know-it-when-I-see-it” basis, leading to widely varying remediation practices judged by a small number of faculty members or administrators.

The ideas outlined by Wasserman and colleagues are “a terrific application of the ‘just-culture’ framework,” according to Nicole Treadway, MD, a first-year primary care resident at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

At Emory, discussions of professionalism start from day 1 of medical school and the subject is revisited throughout training in small groups, Treadway told Medscape Medical News.

But, she said, as the authors point out, definitions of unprofessionalism are not always clear and the examples the authors put forward help put lapses in context.

The framework also allows for looking at mistakes in light of the stress trainees encounter and the greater chance of making a professionalism error in those situations, she noted.

In her own work, she says, because she is juggling both inpatient and outpatient care, she is finding it is easy to get behind on correspondence or communicating lab results or having follow-up conversations.

Those delays could be seen as lapses in professionalism, but under this framework, there may be system solutions or training opportunities to consider.

“We do need this organizational architecture, and I think it could serve us well in really helping us identify and appropriately respond to what we see regarding professionalism,” she said.

Framework Helps Standardize Thinking

She said having a universal framework also helps because while standards of professionalism are easier to monitor in a single medical school, when students scatter to other hospitals for clinical training, those hospitals may have different professionalism standards.

Wasserman agrees, saying, “This could be easily adopted in any environment where people deal with professionalism lapses. I don’t even think it’s necessarily relegated to trainees. It’s a great way to think about any kind of lapses, just as hospitals think about medical errors.”

He said the next step is presenting the framework at various medical schools for feedback and research to see whether the framework improves processes.

Potential criticism, he said, might come from those who say such a construct avoids punishing students who make errors.

“There will always be people who say we’re pandering to medical students whenever we worry about the learning environment,” he said. “There are old-school purists who say when people screw up you should punish them.”

But he adds healthcare broadly has moved past that thinking.

“People recognized 20 years ago or more from the standpoint of improving healthcare systems and safety that is a bad strategy. You’ll never get error-free humans working in your system, and what you have to do is consider how the system is functioning and think about ways to optimize the system so people can be their best within it.”

Wasserman and Treadway have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some instances of unprofessional behavior by medical trainees are universally deemed egregious and worthy of discipline — for example, looking up a friend’s medical data after HIPAA training.

Conversely, some professionalism lapses may be widely thought of as a teaching and consoling moment, such as the human error involved in forgetting a scheduled repositioning of a patient.

But between the extremes is a vast gray area. To deal with those cases appropriately, Jason Wasserman, PhD, and colleagues propose a new framework by which to judge each infraction.

The framework draws from “just culture” concepts used to evaluate medical errors, Wasserman, associate professor of biomedical science at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Rochester, Michigan, told Medscape Medical News. Such an approach takes into account the environment in which the error was made, the knowledge and intent of the person making the error, and the severity and consequences of the infraction so that trainees and institutions can learn from mistakes.

“Trainees by definition are not going to fully get it,” he explained. “By definition they’re not going to fully achieve professional expectations. So how can we respond to the things we need to respond to, but do it in a way that’s educational?”

Wasserman and coauthors’ framework for remediation, which they published February 20 in The New England Journal of Medicine, takes into account several questions: Was the expectation clear? Were there factors beyond the trainees› control? What were the trainees› intentions and did they understand the consequences? Did the person genuinely believe the action was inconsequential?

An example requiring discipline, the authors say, would be using a crib sheet during an exam. In that case the intent is clear, there is no defensible belief that the action is inconsequential, and there is a clear understanding the action is wrong.

But a response of “affirm, support, and advise” is more appropriate, for example, when a student’s alarm doesn’t go off after a power outage and they miss a mandatory meeting.

Wasserman points out that this framework won’t cover all situations.

“This is not an algorithm for answering your questions about what to do,” he said. “It’s an architecture for clarifying the discussion about that. It can really tease out all the threads that need to be considered to best respond to and correct the professionalism lapse, but do it in a way that is developmentally appropriate.”

A Core Competency

For two decades, professionalism has been considered a core competency of medical education. In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties formalized it as such. In 2013, the Association of American Medical Colleges formally required related professionalism competencies.

However, identifying lapses has operated largely on an “I-know-it-when-I-see-it” basis, leading to widely varying remediation practices judged by a small number of faculty members or administrators.

The ideas outlined by Wasserman and colleagues are “a terrific application of the ‘just-culture’ framework,” according to Nicole Treadway, MD, a first-year primary care resident at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

At Emory, discussions of professionalism start from day 1 of medical school and the subject is revisited throughout training in small groups, Treadway told Medscape Medical News.

But, she said, as the authors point out, definitions of unprofessionalism are not always clear and the examples the authors put forward help put lapses in context.

The framework also allows for looking at mistakes in light of the stress trainees encounter and the greater chance of making a professionalism error in those situations, she noted.

In her own work, she says, because she is juggling both inpatient and outpatient care, she is finding it is easy to get behind on correspondence or communicating lab results or having follow-up conversations.

Those delays could be seen as lapses in professionalism, but under this framework, there may be system solutions or training opportunities to consider.

“We do need this organizational architecture, and I think it could serve us well in really helping us identify and appropriately respond to what we see regarding professionalism,” she said.

Framework Helps Standardize Thinking

She said having a universal framework also helps because while standards of professionalism are easier to monitor in a single medical school, when students scatter to other hospitals for clinical training, those hospitals may have different professionalism standards.

Wasserman agrees, saying, “This could be easily adopted in any environment where people deal with professionalism lapses. I don’t even think it’s necessarily relegated to trainees. It’s a great way to think about any kind of lapses, just as hospitals think about medical errors.”

He said the next step is presenting the framework at various medical schools for feedback and research to see whether the framework improves processes.

Potential criticism, he said, might come from those who say such a construct avoids punishing students who make errors.

“There will always be people who say we’re pandering to medical students whenever we worry about the learning environment,” he said. “There are old-school purists who say when people screw up you should punish them.”

But he adds healthcare broadly has moved past that thinking.

“People recognized 20 years ago or more from the standpoint of improving healthcare systems and safety that is a bad strategy. You’ll never get error-free humans working in your system, and what you have to do is consider how the system is functioning and think about ways to optimize the system so people can be their best within it.”

Wasserman and Treadway have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity expert: Time to embrace growing array of options

MAUI, HAWAII – Specialists who study obesity and embrace the increasing number of treatment options are poised to lead the way in stemming the disease, which Andres Acosta, MD, PhD, calls the “epidemic of the century.”

“Gastroenterologists are in the first line of treatment for obesity management,” said Acosta, who runs the precision medicine for obesity lab at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“Patients with obesity are already in our clinics,” he said in an interview. And too many physicians “are ignoring the problem.”

The vast majority of people with acid reflux have obesity, as do those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, he explained. “By targeting those two areas, we’ll be targeting more than 50% of our patients.” Recurring polyps and colon cancer are also often associated with obesity, he said.

Because of their skill as endoscopists, internists, and nutrition experts, gastroenterologists are uniquely positioned to care for obesity, said Acosta, who is first author of a white paper – Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources – developed by the American Gastroenterological Association with input from nine medical societies.

More treatment choices

Physicians heard an update on options available in the continuum of obesity care from Christopher Thompson, MD, director of endoscopy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, at the Gastroenterology Updates IBD Liver Disease Conference 2020. He discussed the potential weight-loss range and safety profile of each.

Some medications result in a body-weight loss of 5%, whereas gastric bypass surgeries can result in a loss of up to 40%, he said in an interview. And weight loss is typically 10% with intragastric balloon, 15%-20% with aspiration therapies and with endoscopic suturing techniques, and 25%-30% with sleeve gastrectomy.

“It’s nice to be able to offer all of those to patients,” he said, adding that he wants to get the message across to hesitant physicians that obesity management “is not as difficult as they think.”

Physicians can be reluctant to address obesity because of the social stigma associated with excess weight and a discomfort in talking about it.

But “there are ways to open that conversation, and it needs to start happening more,” said Thompson, who pointed out that obesity is the underlying cause of many other illnesses, including diabetes and heart diseases.

And new strategies are in the offing, he explained. His team at Brigham is currently involved in clinical trials to test whether the diversion of food and bile to the lower part of the bowel will generate a metabolic signal that affects insulin resistance and weight, he reported.

They are also testing whether gastric procedures can be combined with small bowel procedures to achieve the weight loss seen with bariatric surgery.

As treatment options for obesity increase, precision medicine will help maximize their potential, said Acosta.

Precision medicine will amp up treatments

Acosta outlined the four categories that patients who are obese generally fall into: those with a “hungry brain,” who think they need to eat more than they do; those with a “hungry gut,” whose gut is not sending the proper signal to the brain that it is full; those with “emotional hunger”; and those with abnormal metabolism.

“For each of those, there are genetic circumstances, metabolism, a hormonal profile, as well as pathophysiologic aspects of obesity, that make these groups unique,” he said.

Deciding which patients should get which treatment is the next frontier, he explained. “For example, if you give an intragastric balloon to all comers, patients will lose about 12% of their body weight. But if you separate responders from nonresponders and you select the right intervention, you can achieve an 18% loss of body weight in the right responders.”

At Mayo, they are working on a blood test to break down phenotypes and identify who will respond best to which treatment, he reported. That could lead to a much more efficient use of scarce resources.

“At the same time, I hope that more insurance companies will cover more obesity treatments,” said Acosta.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MAUI, HAWAII – Specialists who study obesity and embrace the increasing number of treatment options are poised to lead the way in stemming the disease, which Andres Acosta, MD, PhD, calls the “epidemic of the century.”

“Gastroenterologists are in the first line of treatment for obesity management,” said Acosta, who runs the precision medicine for obesity lab at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“Patients with obesity are already in our clinics,” he said in an interview. And too many physicians “are ignoring the problem.”

The vast majority of people with acid reflux have obesity, as do those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, he explained. “By targeting those two areas, we’ll be targeting more than 50% of our patients.” Recurring polyps and colon cancer are also often associated with obesity, he said.

Because of their skill as endoscopists, internists, and nutrition experts, gastroenterologists are uniquely positioned to care for obesity, said Acosta, who is first author of a white paper – Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources – developed by the American Gastroenterological Association with input from nine medical societies.

More treatment choices

Physicians heard an update on options available in the continuum of obesity care from Christopher Thompson, MD, director of endoscopy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, at the Gastroenterology Updates IBD Liver Disease Conference 2020. He discussed the potential weight-loss range and safety profile of each.

Some medications result in a body-weight loss of 5%, whereas gastric bypass surgeries can result in a loss of up to 40%, he said in an interview. And weight loss is typically 10% with intragastric balloon, 15%-20% with aspiration therapies and with endoscopic suturing techniques, and 25%-30% with sleeve gastrectomy.

“It’s nice to be able to offer all of those to patients,” he said, adding that he wants to get the message across to hesitant physicians that obesity management “is not as difficult as they think.”

Physicians can be reluctant to address obesity because of the social stigma associated with excess weight and a discomfort in talking about it.

But “there are ways to open that conversation, and it needs to start happening more,” said Thompson, who pointed out that obesity is the underlying cause of many other illnesses, including diabetes and heart diseases.

And new strategies are in the offing, he explained. His team at Brigham is currently involved in clinical trials to test whether the diversion of food and bile to the lower part of the bowel will generate a metabolic signal that affects insulin resistance and weight, he reported.

They are also testing whether gastric procedures can be combined with small bowel procedures to achieve the weight loss seen with bariatric surgery.

As treatment options for obesity increase, precision medicine will help maximize their potential, said Acosta.

Precision medicine will amp up treatments

Acosta outlined the four categories that patients who are obese generally fall into: those with a “hungry brain,” who think they need to eat more than they do; those with a “hungry gut,” whose gut is not sending the proper signal to the brain that it is full; those with “emotional hunger”; and those with abnormal metabolism.

“For each of those, there are genetic circumstances, metabolism, a hormonal profile, as well as pathophysiologic aspects of obesity, that make these groups unique,” he said.

Deciding which patients should get which treatment is the next frontier, he explained. “For example, if you give an intragastric balloon to all comers, patients will lose about 12% of their body weight. But if you separate responders from nonresponders and you select the right intervention, you can achieve an 18% loss of body weight in the right responders.”

At Mayo, they are working on a blood test to break down phenotypes and identify who will respond best to which treatment, he reported. That could lead to a much more efficient use of scarce resources.

“At the same time, I hope that more insurance companies will cover more obesity treatments,” said Acosta.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MAUI, HAWAII – Specialists who study obesity and embrace the increasing number of treatment options are poised to lead the way in stemming the disease, which Andres Acosta, MD, PhD, calls the “epidemic of the century.”

“Gastroenterologists are in the first line of treatment for obesity management,” said Acosta, who runs the precision medicine for obesity lab at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“Patients with obesity are already in our clinics,” he said in an interview. And too many physicians “are ignoring the problem.”

The vast majority of people with acid reflux have obesity, as do those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, he explained. “By targeting those two areas, we’ll be targeting more than 50% of our patients.” Recurring polyps and colon cancer are also often associated with obesity, he said.

Because of their skill as endoscopists, internists, and nutrition experts, gastroenterologists are uniquely positioned to care for obesity, said Acosta, who is first author of a white paper – Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources – developed by the American Gastroenterological Association with input from nine medical societies.

More treatment choices

Physicians heard an update on options available in the continuum of obesity care from Christopher Thompson, MD, director of endoscopy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, at the Gastroenterology Updates IBD Liver Disease Conference 2020. He discussed the potential weight-loss range and safety profile of each.

Some medications result in a body-weight loss of 5%, whereas gastric bypass surgeries can result in a loss of up to 40%, he said in an interview. And weight loss is typically 10% with intragastric balloon, 15%-20% with aspiration therapies and with endoscopic suturing techniques, and 25%-30% with sleeve gastrectomy.

“It’s nice to be able to offer all of those to patients,” he said, adding that he wants to get the message across to hesitant physicians that obesity management “is not as difficult as they think.”

Physicians can be reluctant to address obesity because of the social stigma associated with excess weight and a discomfort in talking about it.

But “there are ways to open that conversation, and it needs to start happening more,” said Thompson, who pointed out that obesity is the underlying cause of many other illnesses, including diabetes and heart diseases.

And new strategies are in the offing, he explained. His team at Brigham is currently involved in clinical trials to test whether the diversion of food and bile to the lower part of the bowel will generate a metabolic signal that affects insulin resistance and weight, he reported.

They are also testing whether gastric procedures can be combined with small bowel procedures to achieve the weight loss seen with bariatric surgery.

As treatment options for obesity increase, precision medicine will help maximize their potential, said Acosta.

Precision medicine will amp up treatments

Acosta outlined the four categories that patients who are obese generally fall into: those with a “hungry brain,” who think they need to eat more than they do; those with a “hungry gut,” whose gut is not sending the proper signal to the brain that it is full; those with “emotional hunger”; and those with abnormal metabolism.

“For each of those, there are genetic circumstances, metabolism, a hormonal profile, as well as pathophysiologic aspects of obesity, that make these groups unique,” he said.

Deciding which patients should get which treatment is the next frontier, he explained. “For example, if you give an intragastric balloon to all comers, patients will lose about 12% of their body weight. But if you separate responders from nonresponders and you select the right intervention, you can achieve an 18% loss of body weight in the right responders.”

At Mayo, they are working on a blood test to break down phenotypes and identify who will respond best to which treatment, he reported. That could lead to a much more efficient use of scarce resources.

“At the same time, I hope that more insurance companies will cover more obesity treatments,” said Acosta.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM GUILD 2020

Older adults with IBD often undertreated

MAUI, HAWAII – said Christina Ha, MD, from the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles.

Clinicians sometimes fall back on steroids because they are typically inexpensive and because there are fears that the new anti-TNF biologics can cause adverse events in older patients, Ha said at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

“There are not a lot of safety data for the age group, which is not well represented in clinical trials,” she explained. “We can’t necessarily extrapolate data from a study of people with an average age in the 40s to someone in their 70s.”

But, she emphasized, steroid use for more than 3 months is potentially inappropriate.

“If we have a patient on steroids, we should be saying which steroid-sparing strategy will be incorporated into their regimen when we start them on their course of steroids,” she explained.

Ha said she gets asked frequently whether the man-made steroid budesonide, which is readily available, should be considered an acceptable alternative to prednisone.

“Steroids are not maintenance therapies,” she pointed out. “One could argue that maybe someone who has symptomatic mild Crohn’s disease could be kept on low doses of budesonide. But I would argue whether it is really the budesonide that’s helping them or some other disease process related to polypharmacy.”

There are no long-term safety or efficacy data for budesonide in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, she added.

Special considerations

Older patients with IBD have a decreased ability to handle disease activity; they have more comorbidities and a susceptibility to falls, said Ha. Early control of the disease is therefore essential.

Sarcopenia, an inherent part of aging when muscle mass decreases over time, is central to physiologic changes, which have implications for older adults with IBD, she said.

“We’re learning that sarcopenia is also prevalent in our patients with moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease,” she explained. “Sarcopenia is associated with increased risk of infections, hospitalizations, and postoperative complications.”

Other changes occur in the intestines as patients age, Ha reported. “Recent studies have shown that there are changes in the intestinal barrier in terms of the junctions within the mucosal lining that increase intestinal permeability, which may help explain why some patients respond to treatments and others don’t.”

Physical therapy underused

Other treatment options, such as physical therapy, have also been underused in older patients with IBD. For example, there’s often considerable pushback against doing a physical therapy assessment on a hospitalized older patient, said Ha.

Medicare covers up to 80% of those services, but referral wording is key. “They’re not going to cover it for a primary diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s,” she explained. However, “they will cover it for a primary diagnosis of deconditioning with a secondary diagnoses of steroid exposure, anemia, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis.”

Physical therapy can improve muscle function, decrease muscle pain, potentially decrease analgesics, improve bone mass, and decrease joint pain, stress, fatigue, and debility. Fatigue is prevalent in patients with IBD, Ha explained.

Another underused resource is psychosocial assessment, she added. Although depression is not part of the aging process, it is common in those with chronic conditions.

Visits with licensed psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are covered under Medicare Part B, Ha pointed out, as are psychiatric evaluation and testing and individual and group therapy.

Older patients with IBD are often not receiving the care they need, said Uma Mahadevan, MD, a gastroenterologist at UCSF Health in San Francisco.

The need for awareness of polypharmacy, which Ha also discussed, is a concern in all older patients, but especially those with IBD, Mahadevan said in an interview. Clinicians need to be aware of the cascading effect of pharmacy, in which one drug’s adverse effect leads to the prescription of another drug, with different adverse effects.

Ha gave the example of a patient with IBD who started to have diarrhea as an adverse effect of a medication. A clinician might then prescribe a medication for Clostridium difficile, but that might lead to nausea, leading to the prescription of an antinausea medicine.

A multidisciplinary team is needed to perform medication reconciliation, Ha noted.

Correcting anemia important for IBD

Anemia is also underidentified and undertreated in older patients with IBD, Ha said.

“Across the board with inflammatory bowel disease, we don’t do a great job of being aggressive and correcting anemia. That has implications for fatigue and implications with functional status and circulating volume,” she said.

In older patients, it might be that the decline in hemoglobin over time is more important to outcomes than the number itself, she said. “A hemoglobin of 8 g/dL is one thing, but if it was at 12 g/dL 6 months ago, that’s a different story.”

“For older patients, anemia is associated with a high incidence of cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, increased risks of falls and fractures, longer hospitalizations (and thus increased costs of care), increased frailty and dementia, and increased risk of mortality,” Ha said. But, she pointed out, Medicare benefits do cover intravenous iron formulations.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

MAUI, HAWAII – said Christina Ha, MD, from the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles.

Clinicians sometimes fall back on steroids because they are typically inexpensive and because there are fears that the new anti-TNF biologics can cause adverse events in older patients, Ha said at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

“There are not a lot of safety data for the age group, which is not well represented in clinical trials,” she explained. “We can’t necessarily extrapolate data from a study of people with an average age in the 40s to someone in their 70s.”

But, she emphasized, steroid use for more than 3 months is potentially inappropriate.

“If we have a patient on steroids, we should be saying which steroid-sparing strategy will be incorporated into their regimen when we start them on their course of steroids,” she explained.

Ha said she gets asked frequently whether the man-made steroid budesonide, which is readily available, should be considered an acceptable alternative to prednisone.

“Steroids are not maintenance therapies,” she pointed out. “One could argue that maybe someone who has symptomatic mild Crohn’s disease could be kept on low doses of budesonide. But I would argue whether it is really the budesonide that’s helping them or some other disease process related to polypharmacy.”

There are no long-term safety or efficacy data for budesonide in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, she added.

Special considerations

Older patients with IBD have a decreased ability to handle disease activity; they have more comorbidities and a susceptibility to falls, said Ha. Early control of the disease is therefore essential.

Sarcopenia, an inherent part of aging when muscle mass decreases over time, is central to physiologic changes, which have implications for older adults with IBD, she said.

“We’re learning that sarcopenia is also prevalent in our patients with moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease,” she explained. “Sarcopenia is associated with increased risk of infections, hospitalizations, and postoperative complications.”

Other changes occur in the intestines as patients age, Ha reported. “Recent studies have shown that there are changes in the intestinal barrier in terms of the junctions within the mucosal lining that increase intestinal permeability, which may help explain why some patients respond to treatments and others don’t.”

Physical therapy underused

Other treatment options, such as physical therapy, have also been underused in older patients with IBD. For example, there’s often considerable pushback against doing a physical therapy assessment on a hospitalized older patient, said Ha.

Medicare covers up to 80% of those services, but referral wording is key. “They’re not going to cover it for a primary diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s,” she explained. However, “they will cover it for a primary diagnosis of deconditioning with a secondary diagnoses of steroid exposure, anemia, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis.”

Physical therapy can improve muscle function, decrease muscle pain, potentially decrease analgesics, improve bone mass, and decrease joint pain, stress, fatigue, and debility. Fatigue is prevalent in patients with IBD, Ha explained.

Another underused resource is psychosocial assessment, she added. Although depression is not part of the aging process, it is common in those with chronic conditions.

Visits with licensed psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are covered under Medicare Part B, Ha pointed out, as are psychiatric evaluation and testing and individual and group therapy.

Older patients with IBD are often not receiving the care they need, said Uma Mahadevan, MD, a gastroenterologist at UCSF Health in San Francisco.

The need for awareness of polypharmacy, which Ha also discussed, is a concern in all older patients, but especially those with IBD, Mahadevan said in an interview. Clinicians need to be aware of the cascading effect of pharmacy, in which one drug’s adverse effect leads to the prescription of another drug, with different adverse effects.

Ha gave the example of a patient with IBD who started to have diarrhea as an adverse effect of a medication. A clinician might then prescribe a medication for Clostridium difficile, but that might lead to nausea, leading to the prescription of an antinausea medicine.

A multidisciplinary team is needed to perform medication reconciliation, Ha noted.

Correcting anemia important for IBD

Anemia is also underidentified and undertreated in older patients with IBD, Ha said.

“Across the board with inflammatory bowel disease, we don’t do a great job of being aggressive and correcting anemia. That has implications for fatigue and implications with functional status and circulating volume,” she said.

In older patients, it might be that the decline in hemoglobin over time is more important to outcomes than the number itself, she said. “A hemoglobin of 8 g/dL is one thing, but if it was at 12 g/dL 6 months ago, that’s a different story.”

“For older patients, anemia is associated with a high incidence of cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, increased risks of falls and fractures, longer hospitalizations (and thus increased costs of care), increased frailty and dementia, and increased risk of mortality,” Ha said. But, she pointed out, Medicare benefits do cover intravenous iron formulations.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

MAUI, HAWAII – said Christina Ha, MD, from the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles.

Clinicians sometimes fall back on steroids because they are typically inexpensive and because there are fears that the new anti-TNF biologics can cause adverse events in older patients, Ha said at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

“There are not a lot of safety data for the age group, which is not well represented in clinical trials,” she explained. “We can’t necessarily extrapolate data from a study of people with an average age in the 40s to someone in their 70s.”

But, she emphasized, steroid use for more than 3 months is potentially inappropriate.

“If we have a patient on steroids, we should be saying which steroid-sparing strategy will be incorporated into their regimen when we start them on their course of steroids,” she explained.

Ha said she gets asked frequently whether the man-made steroid budesonide, which is readily available, should be considered an acceptable alternative to prednisone.

“Steroids are not maintenance therapies,” she pointed out. “One could argue that maybe someone who has symptomatic mild Crohn’s disease could be kept on low doses of budesonide. But I would argue whether it is really the budesonide that’s helping them or some other disease process related to polypharmacy.”

There are no long-term safety or efficacy data for budesonide in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, she added.

Special considerations

Older patients with IBD have a decreased ability to handle disease activity; they have more comorbidities and a susceptibility to falls, said Ha. Early control of the disease is therefore essential.

Sarcopenia, an inherent part of aging when muscle mass decreases over time, is central to physiologic changes, which have implications for older adults with IBD, she said.

“We’re learning that sarcopenia is also prevalent in our patients with moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease,” she explained. “Sarcopenia is associated with increased risk of infections, hospitalizations, and postoperative complications.”

Other changes occur in the intestines as patients age, Ha reported. “Recent studies have shown that there are changes in the intestinal barrier in terms of the junctions within the mucosal lining that increase intestinal permeability, which may help explain why some patients respond to treatments and others don’t.”

Physical therapy underused

Other treatment options, such as physical therapy, have also been underused in older patients with IBD. For example, there’s often considerable pushback against doing a physical therapy assessment on a hospitalized older patient, said Ha.

Medicare covers up to 80% of those services, but referral wording is key. “They’re not going to cover it for a primary diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s,” she explained. However, “they will cover it for a primary diagnosis of deconditioning with a secondary diagnoses of steroid exposure, anemia, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis.”

Physical therapy can improve muscle function, decrease muscle pain, potentially decrease analgesics, improve bone mass, and decrease joint pain, stress, fatigue, and debility. Fatigue is prevalent in patients with IBD, Ha explained.

Another underused resource is psychosocial assessment, she added. Although depression is not part of the aging process, it is common in those with chronic conditions.

Visits with licensed psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are covered under Medicare Part B, Ha pointed out, as are psychiatric evaluation and testing and individual and group therapy.

Older patients with IBD are often not receiving the care they need, said Uma Mahadevan, MD, a gastroenterologist at UCSF Health in San Francisco.

The need for awareness of polypharmacy, which Ha also discussed, is a concern in all older patients, but especially those with IBD, Mahadevan said in an interview. Clinicians need to be aware of the cascading effect of pharmacy, in which one drug’s adverse effect leads to the prescription of another drug, with different adverse effects.

Ha gave the example of a patient with IBD who started to have diarrhea as an adverse effect of a medication. A clinician might then prescribe a medication for Clostridium difficile, but that might lead to nausea, leading to the prescription of an antinausea medicine.

A multidisciplinary team is needed to perform medication reconciliation, Ha noted.

Correcting anemia important for IBD

Anemia is also underidentified and undertreated in older patients with IBD, Ha said.

“Across the board with inflammatory bowel disease, we don’t do a great job of being aggressive and correcting anemia. That has implications for fatigue and implications with functional status and circulating volume,” she said.

In older patients, it might be that the decline in hemoglobin over time is more important to outcomes than the number itself, she said. “A hemoglobin of 8 g/dL is one thing, but if it was at 12 g/dL 6 months ago, that’s a different story.”

“For older patients, anemia is associated with a high incidence of cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, increased risks of falls and fractures, longer hospitalizations (and thus increased costs of care), increased frailty and dementia, and increased risk of mortality,” Ha said. But, she pointed out, Medicare benefits do cover intravenous iron formulations.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM GUILD 2020

Rising number of young people dying after heavy drinking

MAUI, HAWAII – Alcohol use and deaths related to alcohol-use disorders are increasing, and young adults might be the group to watch, said Norah Terrault, MD, MPH, professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC in Los Angeles.

“A lot of young people are drinking large amounts and they don’t know they’re at risk. They may not drink much during the week but then drink 30 drinks on the weekend,” Dr. Terrault told Medscape Medical News.

The largest relative increase in deaths from alcoholic cirrhosis – 10.5% from 2009 to 2016 – was in the 25- to 34-year age group, she reported here at the Gastroenterology Updates IBD Liver Disease Conference 2020.

This highlights the importance of asking for details about alcohol use during primary care visits; not only how much, but also what time of day, for instance, she explained.

Dr. Terrault’s team at Keck is part of the ACCELERATE-AH consortium, a group of 12 transplant centers looking at patterns of alcohol use before and after liver transplantation.

In their retrospective study of 147 consecutive transplant patients from 2006 to 2018, they found that young age, a history of multiple rehab attempts, and overt encephalopathy at time of transplantation were predictors of alcohol use after the procedure.

Corticosteroids remain the only proven therapy for alcoholic hepatitis. “We have not seen a new therapy in this arena in decades,” said Dr. Terrault. “We really have nothing to offer these patients, yet it’s an incredibly common presentation with a high mortality.”

More treatment options

The good news is that some phase 2 data look promising for new therapies, she reported.

“Some of them are targeting injury and regeneration primarily. Others are looking at the anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects. Some are also looking at how gut permeability and the microbiome are influencing outcomes,” she explained.

Transplantation has become very important for patients who do not respond to current therapy, and selection criteria have evolved over the years to take this into account, she pointed out.

In the early 1980s, alcoholic hepatitis was considered an inappropriate indication for liver transplantation. In the early 2000s, the guidance moved to setting 6 months of alcohol abstinence as a criterion for transplantation. The 6-month rule effectively eliminated patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, who, by the time they needed a new liver, would not have 6 months to live.

Recently, guidelines have added the option of transplantation for patients with alcoholic hepatitis. The option was always there for people who developed alcohol cirrhosis or liver cancer, but now alcoholic hepatitis is recognized as a potential indication for transplantation, Dr. Terrault explained.

Today, transplant centers are moving away from the 6-month rule for two main reasons, she said. One is that few data support the 6-month time period as the duration that makes a difference.

“There is nothing magical about 6 months vs. 3 months or 12 months,” she said, adding that studies have shown that other factors might be better indicators, such as family support and whether the person is employed.

Second, recent studies have shown that rates of 3-year survival are similar in people who did not abstain at all before the procedure and those who undergo transplantation for other reasons.

The ACCELERATE-AH consortium also found that 70% of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis remained abstinent up to 3 years after transplantation.

Anytime we give an organ to anyone on the list, someone else may die without one. Every year, 20% of patients on the list die without a transplant.

The selection process remains complicated and controversial, Dr. Terrault acknowledged.

“Anytime we give an organ to anyone on the list, someone else may die without one. Every year, 20% of patients on the list die without a transplant,” she said.

And there is concern that because patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis present with severe illness, they get moved to the top of the wait list. The rationale for that, she explained, is that it is done that way in other acute situations.

“We transplant individuals who have an acetaminophen overdose, for example. That’s common in many programs,” she said.

“My issue is that some patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis that have a very high severity score, but some of them, just with abstinence, will get better,” said Guadalupe Garcia-Tsao, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

There are cases in which acute alcoholic hepatitis will resolve with abstinence, “and patients can return to an entirely compensated state of cirrhosis, in which they are entirely asymptomatic and they can live,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But it’s hard to know without a control group which patients would have that kind of success with just abstinence, she acknowledged.

Terrault said she agreed, and added that “our tools are not that good,” so determining which patients can be “pulled back from the brink” without transplantation is a challenge.

“There’s still a lot to learn about how we do this, and how we do it well,” she said.

Alcoholic hepatitis as an indication for liver transplantation is rare – less than 1% – but growing.

“This is a potential therapy for your patient who is sick in the ICU with a high severity of disease who has failed steroids. We should call out to see if there’s a transplant program that might be willing to evaluate them,” she said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MAUI, HAWAII – Alcohol use and deaths related to alcohol-use disorders are increasing, and young adults might be the group to watch, said Norah Terrault, MD, MPH, professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC in Los Angeles.

“A lot of young people are drinking large amounts and they don’t know they’re at risk. They may not drink much during the week but then drink 30 drinks on the weekend,” Dr. Terrault told Medscape Medical News.

The largest relative increase in deaths from alcoholic cirrhosis – 10.5% from 2009 to 2016 – was in the 25- to 34-year age group, she reported here at the Gastroenterology Updates IBD Liver Disease Conference 2020.

This highlights the importance of asking for details about alcohol use during primary care visits; not only how much, but also what time of day, for instance, she explained.

Dr. Terrault’s team at Keck is part of the ACCELERATE-AH consortium, a group of 12 transplant centers looking at patterns of alcohol use before and after liver transplantation.

In their retrospective study of 147 consecutive transplant patients from 2006 to 2018, they found that young age, a history of multiple rehab attempts, and overt encephalopathy at time of transplantation were predictors of alcohol use after the procedure.

Corticosteroids remain the only proven therapy for alcoholic hepatitis. “We have not seen a new therapy in this arena in decades,” said Dr. Terrault. “We really have nothing to offer these patients, yet it’s an incredibly common presentation with a high mortality.”

More treatment options

The good news is that some phase 2 data look promising for new therapies, she reported.

“Some of them are targeting injury and regeneration primarily. Others are looking at the anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects. Some are also looking at how gut permeability and the microbiome are influencing outcomes,” she explained.

Transplantation has become very important for patients who do not respond to current therapy, and selection criteria have evolved over the years to take this into account, she pointed out.

In the early 1980s, alcoholic hepatitis was considered an inappropriate indication for liver transplantation. In the early 2000s, the guidance moved to setting 6 months of alcohol abstinence as a criterion for transplantation. The 6-month rule effectively eliminated patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, who, by the time they needed a new liver, would not have 6 months to live.

Recently, guidelines have added the option of transplantation for patients with alcoholic hepatitis. The option was always there for people who developed alcohol cirrhosis or liver cancer, but now alcoholic hepatitis is recognized as a potential indication for transplantation, Dr. Terrault explained.

Today, transplant centers are moving away from the 6-month rule for two main reasons, she said. One is that few data support the 6-month time period as the duration that makes a difference.

“There is nothing magical about 6 months vs. 3 months or 12 months,” she said, adding that studies have shown that other factors might be better indicators, such as family support and whether the person is employed.

Second, recent studies have shown that rates of 3-year survival are similar in people who did not abstain at all before the procedure and those who undergo transplantation for other reasons.

The ACCELERATE-AH consortium also found that 70% of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis remained abstinent up to 3 years after transplantation.

Anytime we give an organ to anyone on the list, someone else may die without one. Every year, 20% of patients on the list die without a transplant.

The selection process remains complicated and controversial, Dr. Terrault acknowledged.

“Anytime we give an organ to anyone on the list, someone else may die without one. Every year, 20% of patients on the list die without a transplant,” she said.

And there is concern that because patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis present with severe illness, they get moved to the top of the wait list. The rationale for that, she explained, is that it is done that way in other acute situations.

“We transplant individuals who have an acetaminophen overdose, for example. That’s common in many programs,” she said.

“My issue is that some patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis that have a very high severity score, but some of them, just with abstinence, will get better,” said Guadalupe Garcia-Tsao, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

There are cases in which acute alcoholic hepatitis will resolve with abstinence, “and patients can return to an entirely compensated state of cirrhosis, in which they are entirely asymptomatic and they can live,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But it’s hard to know without a control group which patients would have that kind of success with just abstinence, she acknowledged.

Terrault said she agreed, and added that “our tools are not that good,” so determining which patients can be “pulled back from the brink” without transplantation is a challenge.

“There’s still a lot to learn about how we do this, and how we do it well,” she said.

Alcoholic hepatitis as an indication for liver transplantation is rare – less than 1% – but growing.

“This is a potential therapy for your patient who is sick in the ICU with a high severity of disease who has failed steroids. We should call out to see if there’s a transplant program that might be willing to evaluate them,” she said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MAUI, HAWAII – Alcohol use and deaths related to alcohol-use disorders are increasing, and young adults might be the group to watch, said Norah Terrault, MD, MPH, professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC in Los Angeles.

“A lot of young people are drinking large amounts and they don’t know they’re at risk. They may not drink much during the week but then drink 30 drinks on the weekend,” Dr. Terrault told Medscape Medical News.

The largest relative increase in deaths from alcoholic cirrhosis – 10.5% from 2009 to 2016 – was in the 25- to 34-year age group, she reported here at the Gastroenterology Updates IBD Liver Disease Conference 2020.

This highlights the importance of asking for details about alcohol use during primary care visits; not only how much, but also what time of day, for instance, she explained.

Dr. Terrault’s team at Keck is part of the ACCELERATE-AH consortium, a group of 12 transplant centers looking at patterns of alcohol use before and after liver transplantation.

In their retrospective study of 147 consecutive transplant patients from 2006 to 2018, they found that young age, a history of multiple rehab attempts, and overt encephalopathy at time of transplantation were predictors of alcohol use after the procedure.

Corticosteroids remain the only proven therapy for alcoholic hepatitis. “We have not seen a new therapy in this arena in decades,” said Dr. Terrault. “We really have nothing to offer these patients, yet it’s an incredibly common presentation with a high mortality.”

More treatment options

The good news is that some phase 2 data look promising for new therapies, she reported.

“Some of them are targeting injury and regeneration primarily. Others are looking at the anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects. Some are also looking at how gut permeability and the microbiome are influencing outcomes,” she explained.

Transplantation has become very important for patients who do not respond to current therapy, and selection criteria have evolved over the years to take this into account, she pointed out.

In the early 1980s, alcoholic hepatitis was considered an inappropriate indication for liver transplantation. In the early 2000s, the guidance moved to setting 6 months of alcohol abstinence as a criterion for transplantation. The 6-month rule effectively eliminated patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, who, by the time they needed a new liver, would not have 6 months to live.

Recently, guidelines have added the option of transplantation for patients with alcoholic hepatitis. The option was always there for people who developed alcohol cirrhosis or liver cancer, but now alcoholic hepatitis is recognized as a potential indication for transplantation, Dr. Terrault explained.

Today, transplant centers are moving away from the 6-month rule for two main reasons, she said. One is that few data support the 6-month time period as the duration that makes a difference.

“There is nothing magical about 6 months vs. 3 months or 12 months,” she said, adding that studies have shown that other factors might be better indicators, such as family support and whether the person is employed.

Second, recent studies have shown that rates of 3-year survival are similar in people who did not abstain at all before the procedure and those who undergo transplantation for other reasons.

The ACCELERATE-AH consortium also found that 70% of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis remained abstinent up to 3 years after transplantation.

Anytime we give an organ to anyone on the list, someone else may die without one. Every year, 20% of patients on the list die without a transplant.

The selection process remains complicated and controversial, Dr. Terrault acknowledged.

“Anytime we give an organ to anyone on the list, someone else may die without one. Every year, 20% of patients on the list die without a transplant,” she said.

And there is concern that because patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis present with severe illness, they get moved to the top of the wait list. The rationale for that, she explained, is that it is done that way in other acute situations.

“We transplant individuals who have an acetaminophen overdose, for example. That’s common in many programs,” she said.

“My issue is that some patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis that have a very high severity score, but some of them, just with abstinence, will get better,” said Guadalupe Garcia-Tsao, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

There are cases in which acute alcoholic hepatitis will resolve with abstinence, “and patients can return to an entirely compensated state of cirrhosis, in which they are entirely asymptomatic and they can live,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But it’s hard to know without a control group which patients would have that kind of success with just abstinence, she acknowledged.

Terrault said she agreed, and added that “our tools are not that good,” so determining which patients can be “pulled back from the brink” without transplantation is a challenge.

“There’s still a lot to learn about how we do this, and how we do it well,” she said.

Alcoholic hepatitis as an indication for liver transplantation is rare – less than 1% – but growing.

“This is a potential therapy for your patient who is sick in the ICU with a high severity of disease who has failed steroids. We should call out to see if there’s a transplant program that might be willing to evaluate them,” she said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM GUILD 2020

Osteoporosis, fracture risk higher in patients with IBD

MAUI, HAWAII –

In the general population, those who develop osteoporosis are typically women who are thin and postmenopausal, and family history, smoking status, and alcohol use usually play a role, Long said at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

But in the population with IBD, the risk for osteoporosis is similar in women and men, age plays a large role, and corticosteroid use seems to be a driving factor in the development of the disease, she explained.

A previous study that looked at fractures in patients with IBD showed that the risk “is 40% greater than in the general population,” Long reported. In patients younger than 40 years, the risk for fracture was 37% higher than in the general population, and this rate increased with age.

Preventing fractures

Fractures to the hip and spine are linked to significant morbidity, including hospitalization, major surgery, and even death, Long noted. But they are one of the preventable downstream effects of IBD, and patients need to understand that there’s something they can do about their elevated risk.