User login

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

A woman in her mid-50s had been seen by a breast surgeon for 16 years for regular mammograms and sonograms. In May 2009, the breast surgeon misinterpreted a mammogram as negative, as did a radiologist who re-read the mammogram weeks later. In December 2010, the patient returned to the breast surgeon with nipple discharge. No further testing was conducted. In October 2011, the patient was found to have Stage IIIA breast cancer involving 4 lymph nodes. She underwent left radical mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and breast reconstruction. At time of trial, the cancer had invaded her vertebrae, was Stage IV, and most likely incurable.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: Although the surgeon admittedly did not possess the qualifications required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act, he interpreted about 5,000 mammograms per year in his office. In this case, he failed to detect a small breast tumor in May 2009. He also failed to perform testing when the patient reported nipple discharge. A more timely diagnosis of breast cancer at Stage I would have provided a 90% chance of long-term survival.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The defense held the radiologist fully liable because the surgeon was not a qualified interpreter of mammography, therefore relying on the radiologist’s interpretation. The radiologist was legally responsible for the missed diagnosis.

VERDICT: A $15M New York verdict was reached, finding the breast surgeon 75% at fault and the radiologist 25%. The radiologist settled before the trial (the jury was not informed of this). The breast surgeon was responsible for $11.25M. The defense indicated intent to appeal.

Alleged failure to evacuate uterus after cesarean delivery

A 37-year-old woman underwent cesarean delivery (CD) performed by 2 ObGyns. After delivery, she began to hemorrhage and the uterus became atonic. Hysterectomy was performed but the bleeding did not stop. The ObGyns called in 3 other ObGyns. During exploratory laparotomy, the bleeding was halted.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She and her husband had hoped to have more children but the hysterectomy precluded that. She sued all 5 ObGyns, alleging that the delivering ObGyns failed to properly perform the CD and that each physician failed to properly perform the laparotomy, causing a large scar. The claim was discontinued against the 3 surgical ObGyns; trial addressed the 2 delivering ObGyns.

The patient’s expert ObGyn remarked that the hemorrhage was caused by a small placental remnant that remained in the uterus as a result of inadequate evacuation following delivery. The presence of the remnant was indicated by the uterine atony and should have prompted immediate investigation. The physicians’ notes did not document exploration of the uterus prior to closure.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The defense’s expert contended that atony would not be a result of a small remnant of placenta. The patient’s uterus was properly evacuated, the hemorrhage was an unforeseeable complication, and the ObGyns properly addressed the hemorrhage.

VERDICT: A New York defense verdict was returned.

Alleged bowel injury during hysterectomy

Two days after a woman underwent a hysterectomy performed by her ObGyn, she went to the emergency department with increasing pain. Her ObGyn admitted her to the hospital. A general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy the next day that revealed an abscess; a 1-cm perforation of the patient’s bowel was surgically repaired. The patient had a difficult recovery. She developed pneumonia and respiratory failure. She underwent multiple repair surgeries for recurrent abscesses and fistulas because the wound was slow to heal.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn’s surgical technique was negligent. He injured the bowel when inserting a trocar and did not identify the injury in a timely manner. The expert witness commented that such an injury can sometimes be a surgical complication, but not in this case: the ObGyn rushed the procedure because he had another patient waiting for CD at another hospital.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn denied negligence and contended that the trocar used in surgery was too blunt to have caused a perforation. It would have been obvious to the ObGyn during surgery if a perforation had occurred. The perforation developed days after surgery within an abscess.

VERDICT: A Mississippi defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

A woman in her mid-50s had been seen by a breast surgeon for 16 years for regular mammograms and sonograms. In May 2009, the breast surgeon misinterpreted a mammogram as negative, as did a radiologist who re-read the mammogram weeks later. In December 2010, the patient returned to the breast surgeon with nipple discharge. No further testing was conducted. In October 2011, the patient was found to have Stage IIIA breast cancer involving 4 lymph nodes. She underwent left radical mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and breast reconstruction. At time of trial, the cancer had invaded her vertebrae, was Stage IV, and most likely incurable.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: Although the surgeon admittedly did not possess the qualifications required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act, he interpreted about 5,000 mammograms per year in his office. In this case, he failed to detect a small breast tumor in May 2009. He also failed to perform testing when the patient reported nipple discharge. A more timely diagnosis of breast cancer at Stage I would have provided a 90% chance of long-term survival.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The defense held the radiologist fully liable because the surgeon was not a qualified interpreter of mammography, therefore relying on the radiologist’s interpretation. The radiologist was legally responsible for the missed diagnosis.

VERDICT: A $15M New York verdict was reached, finding the breast surgeon 75% at fault and the radiologist 25%. The radiologist settled before the trial (the jury was not informed of this). The breast surgeon was responsible for $11.25M. The defense indicated intent to appeal.

Alleged failure to evacuate uterus after cesarean delivery

A 37-year-old woman underwent cesarean delivery (CD) performed by 2 ObGyns. After delivery, she began to hemorrhage and the uterus became atonic. Hysterectomy was performed but the bleeding did not stop. The ObGyns called in 3 other ObGyns. During exploratory laparotomy, the bleeding was halted.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She and her husband had hoped to have more children but the hysterectomy precluded that. She sued all 5 ObGyns, alleging that the delivering ObGyns failed to properly perform the CD and that each physician failed to properly perform the laparotomy, causing a large scar. The claim was discontinued against the 3 surgical ObGyns; trial addressed the 2 delivering ObGyns.

The patient’s expert ObGyn remarked that the hemorrhage was caused by a small placental remnant that remained in the uterus as a result of inadequate evacuation following delivery. The presence of the remnant was indicated by the uterine atony and should have prompted immediate investigation. The physicians’ notes did not document exploration of the uterus prior to closure.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The defense’s expert contended that atony would not be a result of a small remnant of placenta. The patient’s uterus was properly evacuated, the hemorrhage was an unforeseeable complication, and the ObGyns properly addressed the hemorrhage.

VERDICT: A New York defense verdict was returned.

Alleged bowel injury during hysterectomy

Two days after a woman underwent a hysterectomy performed by her ObGyn, she went to the emergency department with increasing pain. Her ObGyn admitted her to the hospital. A general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy the next day that revealed an abscess; a 1-cm perforation of the patient’s bowel was surgically repaired. The patient had a difficult recovery. She developed pneumonia and respiratory failure. She underwent multiple repair surgeries for recurrent abscesses and fistulas because the wound was slow to heal.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn’s surgical technique was negligent. He injured the bowel when inserting a trocar and did not identify the injury in a timely manner. The expert witness commented that such an injury can sometimes be a surgical complication, but not in this case: the ObGyn rushed the procedure because he had another patient waiting for CD at another hospital.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn denied negligence and contended that the trocar used in surgery was too blunt to have caused a perforation. It would have been obvious to the ObGyn during surgery if a perforation had occurred. The perforation developed days after surgery within an abscess.

VERDICT: A Mississippi defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

A woman in her mid-50s had been seen by a breast surgeon for 16 years for regular mammograms and sonograms. In May 2009, the breast surgeon misinterpreted a mammogram as negative, as did a radiologist who re-read the mammogram weeks later. In December 2010, the patient returned to the breast surgeon with nipple discharge. No further testing was conducted. In October 2011, the patient was found to have Stage IIIA breast cancer involving 4 lymph nodes. She underwent left radical mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and breast reconstruction. At time of trial, the cancer had invaded her vertebrae, was Stage IV, and most likely incurable.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: Although the surgeon admittedly did not possess the qualifications required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act, he interpreted about 5,000 mammograms per year in his office. In this case, he failed to detect a small breast tumor in May 2009. He also failed to perform testing when the patient reported nipple discharge. A more timely diagnosis of breast cancer at Stage I would have provided a 90% chance of long-term survival.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The defense held the radiologist fully liable because the surgeon was not a qualified interpreter of mammography, therefore relying on the radiologist’s interpretation. The radiologist was legally responsible for the missed diagnosis.

VERDICT: A $15M New York verdict was reached, finding the breast surgeon 75% at fault and the radiologist 25%. The radiologist settled before the trial (the jury was not informed of this). The breast surgeon was responsible for $11.25M. The defense indicated intent to appeal.

Alleged failure to evacuate uterus after cesarean delivery

A 37-year-old woman underwent cesarean delivery (CD) performed by 2 ObGyns. After delivery, she began to hemorrhage and the uterus became atonic. Hysterectomy was performed but the bleeding did not stop. The ObGyns called in 3 other ObGyns. During exploratory laparotomy, the bleeding was halted.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She and her husband had hoped to have more children but the hysterectomy precluded that. She sued all 5 ObGyns, alleging that the delivering ObGyns failed to properly perform the CD and that each physician failed to properly perform the laparotomy, causing a large scar. The claim was discontinued against the 3 surgical ObGyns; trial addressed the 2 delivering ObGyns.

The patient’s expert ObGyn remarked that the hemorrhage was caused by a small placental remnant that remained in the uterus as a result of inadequate evacuation following delivery. The presence of the remnant was indicated by the uterine atony and should have prompted immediate investigation. The physicians’ notes did not document exploration of the uterus prior to closure.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The defense’s expert contended that atony would not be a result of a small remnant of placenta. The patient’s uterus was properly evacuated, the hemorrhage was an unforeseeable complication, and the ObGyns properly addressed the hemorrhage.

VERDICT: A New York defense verdict was returned.

Alleged bowel injury during hysterectomy

Two days after a woman underwent a hysterectomy performed by her ObGyn, she went to the emergency department with increasing pain. Her ObGyn admitted her to the hospital. A general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy the next day that revealed an abscess; a 1-cm perforation of the patient’s bowel was surgically repaired. The patient had a difficult recovery. She developed pneumonia and respiratory failure. She underwent multiple repair surgeries for recurrent abscesses and fistulas because the wound was slow to heal.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn’s surgical technique was negligent. He injured the bowel when inserting a trocar and did not identify the injury in a timely manner. The expert witness commented that such an injury can sometimes be a surgical complication, but not in this case: the ObGyn rushed the procedure because he had another patient waiting for CD at another hospital.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn denied negligence and contended that the trocar used in surgery was too blunt to have caused a perforation. It would have been obvious to the ObGyn during surgery if a perforation had occurred. The perforation developed days after surgery within an abscess.

VERDICT: A Mississippi defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy Added to Recommended Uniform Screening Panel

Screening will enable early detection, but the treatment’s exceptional cost could present a barrier to patients.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is now among the disorders officially included in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), which state public health departments use to screen newborns for genetic disorders.

Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Alex M. Azar II formally added SMA to the panel on July 2 on the recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

“Adding SMA to the list will help ensure that babies born with SMA are identified, so that they have the opportunity to benefit from early treatment and intervention,” according to a statement from the Muscular Dystrophy Association about the decision. “This testing can also provide families with a genetic diagnosis—information that often is required to determine whether their child is eligible to participate in clinical trials.”

Adding SMA to the RUSP does not mean that states must screen newborns for the disorder. Each state’s public health apparatus decides independently whether to accept the recommendation and which disorders on the RUSP to screen for. Most states screen for most disorders on the RUSP. Evidence compiled by the advisory committee suggested a wide variation in resources, infrastructure, funding, and time to implementation among states.

Drug Approval Raised Ethical Questions

An estimated one in 11,000 newborns has SMA, a disorder caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. SMA affects motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, thus leading to motor weakness and atrophy. The only treatment for SMA had been palliative care until the FDA approved nusinersen for the disorder in December 2016. The drug’s approval has raised ethical questions.1–3

After reviewing the evidence at its February 8 meeting, the advisory committee recommended adding SMA screening to the RUSP in a March 8 letter from committee chair Joseph A. Bocchini Jr, MD, Professor and Chair of Pediatrics at Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport.

Secretary Azar accepted the recommendation based on the evidence the committee provided; he also requested a follow-up report within two years “describing the status of implementing newborn screening for SMA and clinical outcomes of early treatment, including any potential harms, for infants diagnosed with SMA.”

The advisory committee makes its recommendations to HHS about which heritable disorders to include in the RUSP after it has assessed a systematic, evidence-based review conducted by an external, independent group. Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, Professor of Pediatrics at the Ohio State University and Division Chief of Ambulatory Pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, led the review group for SMA. Dr. Kemper is also deputy editor of Pediatrics and a member of the US Preventive Services Task Force.

According to Secretary Azar’s summary in his July 2 letter of acceptance, the evidence review suggested that “early screening and treatment can lead to decreased mortality for individuals with SMA and improved motor milestones.”

“SMA can be detected through newborn screening, and treatment is now available that can not only reduce the risk of death, but decrease the development of neurologic impairment,” he said in an interview. “As with adding any condition to newborn screening, public health laboratories will need to develop strategies to incorporate the screening test. The current FDA-approved treatment, nusinersen, is delivered by lumbar puncture into the spinal fluid. In addition, there are exciting advances in gene therapy leading to new treatment approaches.”

Symptom Onset Distinguishes the Types of SMA

Approximately 95% of SMA cases result from the deletion of exon 7 from both alleles of SMN1. Other, rarer cases are caused by mutations in different genes. Without the SMN protein produced by SMN1, a person gradually loses muscle function.

A similar gene, SMN2, also can produce the SMN protein, but in much lower amounts—typically less than 10% of what a person needs. People can, however, have multiple copies of SMN2, which can produce slightly more SMN protein and slow the disease process.

The five types of SMA are determined according to symptom onset, which directly correlates with disorder severity and prognosis. Approximately 54% of SMA cases are Type I, in which progressive weakness occurs over the first six months of life and results in early death. Only 18% of children with Type I live past age 4, and 68% die by age 2. Type 0 is rarer, but more severe, usually causing fetal loss or early infant death.

Type II represents 18% of SMA cases and causes progressive weakness by age 15 months. Most people with Type II survive to their 30s but later experience respiratory failure and rarely reach their 40s. Individuals with Types III and IV typically have a normal lifespan and only begin to see progressive muscle weakness after age 1 or in adulthood.

Dr. Kemper’s group focused on the three types diagnosed in infancy: Types I, II, and III. “It will be critical to make sure that infants diagnosed with SMA through newborn screening receive follow-up shortly afterward to determine whether they would benefit from nusinersen,” said Dr. Kemper. “More information is needed about the long-term outcomes of those infants who begin treatment following newborn screening, so we not only know about outcomes in later childhood and adolescence, but treatment approaches can be further refined and personalized.”

Long-Term Data on Nusinersen Are Lacking

Nusinersen alters the splicing of precursor messenger RNA in SMN2 so that the mRNA strands are longer, which increases the amount of SMN protein produced. Concerns about the medication, however, have included its cost—$750,000 in the first year and $375,000 every following year for life—and potential adverse events from repeated administration. Nusinersen is injected into the spinal canal four times in the first year and once annually thereafter, and the painful injections require patient immobilization. Potential adverse events include thrombocytopenia and nephrotoxicity, along with potential complications from repeated lumbar punctures over time.2

Other concerns about the drug include its limited evidence base, lack of long-term data, associated costs with administration (eg, travel costs), the potential for patients taking nusinersen to be excluded from future clinical trials on other treatments, and ensuring parents have enough information on the drug’s limitations and potential risks to provide adequate informed consent.2

Yet evidence to date is favorable in children with early onset SMA. Dr. Bocchini wrote in the letter to Secretary Azar that “limited data suggest that treatment effect is greater when the treatment is initiated before symptoms develop and when the individual has more copies of SMN2.”

Dr. Kemper’s group concluded that screening can detect SMA in newborns and that treatment can modify the disease course. “Grey literature suggests those with total disease duration less than or equal to 12 weeks before nusinersen treatment were more likely to have better outcomes than those with longer periods of disease duration.

“Presymptomatic treatment alters the natural history” of the disorder, the group found, although outcome data past age 1 are not yet available. Based on findings from a New York pilot program, they predicted that nationwide newborn screening would avert 33 deaths and 48 cases of children who were dependent on a ventilator among an annual cohort of four million births.

At the time of the evidence review, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, Utah, and Wisconsin initiated pilot programs or whole-population mandated screening for SMA. Of the three states that reported costs, all reported costs of $1 or less per screen.

The research for the evidence review was funded by a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. No disclosures were provided for evidence review group members.

—Tara Haelle

References

1. King NMP, Bishop CE. New treatments for serious conditions: ethical implications. Gene Ther. 2017;24(9):534-538.

2. Gerrity MS, Prasad V, Obley AJ. Concerns about the approval of nusinersen sodium by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):743-744.

3. Burgart AM, Magnus D, Tabor HK, et al. Ethical challenges confronted when providing nusinersen treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):188-192.

Screening will enable early detection, but the treatment’s exceptional cost could present a barrier to patients.

Screening will enable early detection, but the treatment’s exceptional cost could present a barrier to patients.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is now among the disorders officially included in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), which state public health departments use to screen newborns for genetic disorders.

Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Alex M. Azar II formally added SMA to the panel on July 2 on the recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

“Adding SMA to the list will help ensure that babies born with SMA are identified, so that they have the opportunity to benefit from early treatment and intervention,” according to a statement from the Muscular Dystrophy Association about the decision. “This testing can also provide families with a genetic diagnosis—information that often is required to determine whether their child is eligible to participate in clinical trials.”

Adding SMA to the RUSP does not mean that states must screen newborns for the disorder. Each state’s public health apparatus decides independently whether to accept the recommendation and which disorders on the RUSP to screen for. Most states screen for most disorders on the RUSP. Evidence compiled by the advisory committee suggested a wide variation in resources, infrastructure, funding, and time to implementation among states.

Drug Approval Raised Ethical Questions

An estimated one in 11,000 newborns has SMA, a disorder caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. SMA affects motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, thus leading to motor weakness and atrophy. The only treatment for SMA had been palliative care until the FDA approved nusinersen for the disorder in December 2016. The drug’s approval has raised ethical questions.1–3

After reviewing the evidence at its February 8 meeting, the advisory committee recommended adding SMA screening to the RUSP in a March 8 letter from committee chair Joseph A. Bocchini Jr, MD, Professor and Chair of Pediatrics at Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport.

Secretary Azar accepted the recommendation based on the evidence the committee provided; he also requested a follow-up report within two years “describing the status of implementing newborn screening for SMA and clinical outcomes of early treatment, including any potential harms, for infants diagnosed with SMA.”

The advisory committee makes its recommendations to HHS about which heritable disorders to include in the RUSP after it has assessed a systematic, evidence-based review conducted by an external, independent group. Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, Professor of Pediatrics at the Ohio State University and Division Chief of Ambulatory Pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, led the review group for SMA. Dr. Kemper is also deputy editor of Pediatrics and a member of the US Preventive Services Task Force.

According to Secretary Azar’s summary in his July 2 letter of acceptance, the evidence review suggested that “early screening and treatment can lead to decreased mortality for individuals with SMA and improved motor milestones.”

“SMA can be detected through newborn screening, and treatment is now available that can not only reduce the risk of death, but decrease the development of neurologic impairment,” he said in an interview. “As with adding any condition to newborn screening, public health laboratories will need to develop strategies to incorporate the screening test. The current FDA-approved treatment, nusinersen, is delivered by lumbar puncture into the spinal fluid. In addition, there are exciting advances in gene therapy leading to new treatment approaches.”

Symptom Onset Distinguishes the Types of SMA

Approximately 95% of SMA cases result from the deletion of exon 7 from both alleles of SMN1. Other, rarer cases are caused by mutations in different genes. Without the SMN protein produced by SMN1, a person gradually loses muscle function.

A similar gene, SMN2, also can produce the SMN protein, but in much lower amounts—typically less than 10% of what a person needs. People can, however, have multiple copies of SMN2, which can produce slightly more SMN protein and slow the disease process.

The five types of SMA are determined according to symptom onset, which directly correlates with disorder severity and prognosis. Approximately 54% of SMA cases are Type I, in which progressive weakness occurs over the first six months of life and results in early death. Only 18% of children with Type I live past age 4, and 68% die by age 2. Type 0 is rarer, but more severe, usually causing fetal loss or early infant death.

Type II represents 18% of SMA cases and causes progressive weakness by age 15 months. Most people with Type II survive to their 30s but later experience respiratory failure and rarely reach their 40s. Individuals with Types III and IV typically have a normal lifespan and only begin to see progressive muscle weakness after age 1 or in adulthood.

Dr. Kemper’s group focused on the three types diagnosed in infancy: Types I, II, and III. “It will be critical to make sure that infants diagnosed with SMA through newborn screening receive follow-up shortly afterward to determine whether they would benefit from nusinersen,” said Dr. Kemper. “More information is needed about the long-term outcomes of those infants who begin treatment following newborn screening, so we not only know about outcomes in later childhood and adolescence, but treatment approaches can be further refined and personalized.”

Long-Term Data on Nusinersen Are Lacking

Nusinersen alters the splicing of precursor messenger RNA in SMN2 so that the mRNA strands are longer, which increases the amount of SMN protein produced. Concerns about the medication, however, have included its cost—$750,000 in the first year and $375,000 every following year for life—and potential adverse events from repeated administration. Nusinersen is injected into the spinal canal four times in the first year and once annually thereafter, and the painful injections require patient immobilization. Potential adverse events include thrombocytopenia and nephrotoxicity, along with potential complications from repeated lumbar punctures over time.2

Other concerns about the drug include its limited evidence base, lack of long-term data, associated costs with administration (eg, travel costs), the potential for patients taking nusinersen to be excluded from future clinical trials on other treatments, and ensuring parents have enough information on the drug’s limitations and potential risks to provide adequate informed consent.2

Yet evidence to date is favorable in children with early onset SMA. Dr. Bocchini wrote in the letter to Secretary Azar that “limited data suggest that treatment effect is greater when the treatment is initiated before symptoms develop and when the individual has more copies of SMN2.”

Dr. Kemper’s group concluded that screening can detect SMA in newborns and that treatment can modify the disease course. “Grey literature suggests those with total disease duration less than or equal to 12 weeks before nusinersen treatment were more likely to have better outcomes than those with longer periods of disease duration.

“Presymptomatic treatment alters the natural history” of the disorder, the group found, although outcome data past age 1 are not yet available. Based on findings from a New York pilot program, they predicted that nationwide newborn screening would avert 33 deaths and 48 cases of children who were dependent on a ventilator among an annual cohort of four million births.

At the time of the evidence review, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, Utah, and Wisconsin initiated pilot programs or whole-population mandated screening for SMA. Of the three states that reported costs, all reported costs of $1 or less per screen.

The research for the evidence review was funded by a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. No disclosures were provided for evidence review group members.

—Tara Haelle

References

1. King NMP, Bishop CE. New treatments for serious conditions: ethical implications. Gene Ther. 2017;24(9):534-538.

2. Gerrity MS, Prasad V, Obley AJ. Concerns about the approval of nusinersen sodium by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):743-744.

3. Burgart AM, Magnus D, Tabor HK, et al. Ethical challenges confronted when providing nusinersen treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):188-192.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is now among the disorders officially included in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), which state public health departments use to screen newborns for genetic disorders.

Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Alex M. Azar II formally added SMA to the panel on July 2 on the recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

“Adding SMA to the list will help ensure that babies born with SMA are identified, so that they have the opportunity to benefit from early treatment and intervention,” according to a statement from the Muscular Dystrophy Association about the decision. “This testing can also provide families with a genetic diagnosis—information that often is required to determine whether their child is eligible to participate in clinical trials.”

Adding SMA to the RUSP does not mean that states must screen newborns for the disorder. Each state’s public health apparatus decides independently whether to accept the recommendation and which disorders on the RUSP to screen for. Most states screen for most disorders on the RUSP. Evidence compiled by the advisory committee suggested a wide variation in resources, infrastructure, funding, and time to implementation among states.

Drug Approval Raised Ethical Questions

An estimated one in 11,000 newborns has SMA, a disorder caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. SMA affects motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, thus leading to motor weakness and atrophy. The only treatment for SMA had been palliative care until the FDA approved nusinersen for the disorder in December 2016. The drug’s approval has raised ethical questions.1–3

After reviewing the evidence at its February 8 meeting, the advisory committee recommended adding SMA screening to the RUSP in a March 8 letter from committee chair Joseph A. Bocchini Jr, MD, Professor and Chair of Pediatrics at Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport.

Secretary Azar accepted the recommendation based on the evidence the committee provided; he also requested a follow-up report within two years “describing the status of implementing newborn screening for SMA and clinical outcomes of early treatment, including any potential harms, for infants diagnosed with SMA.”

The advisory committee makes its recommendations to HHS about which heritable disorders to include in the RUSP after it has assessed a systematic, evidence-based review conducted by an external, independent group. Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, Professor of Pediatrics at the Ohio State University and Division Chief of Ambulatory Pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, led the review group for SMA. Dr. Kemper is also deputy editor of Pediatrics and a member of the US Preventive Services Task Force.

According to Secretary Azar’s summary in his July 2 letter of acceptance, the evidence review suggested that “early screening and treatment can lead to decreased mortality for individuals with SMA and improved motor milestones.”

“SMA can be detected through newborn screening, and treatment is now available that can not only reduce the risk of death, but decrease the development of neurologic impairment,” he said in an interview. “As with adding any condition to newborn screening, public health laboratories will need to develop strategies to incorporate the screening test. The current FDA-approved treatment, nusinersen, is delivered by lumbar puncture into the spinal fluid. In addition, there are exciting advances in gene therapy leading to new treatment approaches.”

Symptom Onset Distinguishes the Types of SMA

Approximately 95% of SMA cases result from the deletion of exon 7 from both alleles of SMN1. Other, rarer cases are caused by mutations in different genes. Without the SMN protein produced by SMN1, a person gradually loses muscle function.

A similar gene, SMN2, also can produce the SMN protein, but in much lower amounts—typically less than 10% of what a person needs. People can, however, have multiple copies of SMN2, which can produce slightly more SMN protein and slow the disease process.

The five types of SMA are determined according to symptom onset, which directly correlates with disorder severity and prognosis. Approximately 54% of SMA cases are Type I, in which progressive weakness occurs over the first six months of life and results in early death. Only 18% of children with Type I live past age 4, and 68% die by age 2. Type 0 is rarer, but more severe, usually causing fetal loss or early infant death.

Type II represents 18% of SMA cases and causes progressive weakness by age 15 months. Most people with Type II survive to their 30s but later experience respiratory failure and rarely reach their 40s. Individuals with Types III and IV typically have a normal lifespan and only begin to see progressive muscle weakness after age 1 or in adulthood.

Dr. Kemper’s group focused on the three types diagnosed in infancy: Types I, II, and III. “It will be critical to make sure that infants diagnosed with SMA through newborn screening receive follow-up shortly afterward to determine whether they would benefit from nusinersen,” said Dr. Kemper. “More information is needed about the long-term outcomes of those infants who begin treatment following newborn screening, so we not only know about outcomes in later childhood and adolescence, but treatment approaches can be further refined and personalized.”

Long-Term Data on Nusinersen Are Lacking

Nusinersen alters the splicing of precursor messenger RNA in SMN2 so that the mRNA strands are longer, which increases the amount of SMN protein produced. Concerns about the medication, however, have included its cost—$750,000 in the first year and $375,000 every following year for life—and potential adverse events from repeated administration. Nusinersen is injected into the spinal canal four times in the first year and once annually thereafter, and the painful injections require patient immobilization. Potential adverse events include thrombocytopenia and nephrotoxicity, along with potential complications from repeated lumbar punctures over time.2

Other concerns about the drug include its limited evidence base, lack of long-term data, associated costs with administration (eg, travel costs), the potential for patients taking nusinersen to be excluded from future clinical trials on other treatments, and ensuring parents have enough information on the drug’s limitations and potential risks to provide adequate informed consent.2

Yet evidence to date is favorable in children with early onset SMA. Dr. Bocchini wrote in the letter to Secretary Azar that “limited data suggest that treatment effect is greater when the treatment is initiated before symptoms develop and when the individual has more copies of SMN2.”

Dr. Kemper’s group concluded that screening can detect SMA in newborns and that treatment can modify the disease course. “Grey literature suggests those with total disease duration less than or equal to 12 weeks before nusinersen treatment were more likely to have better outcomes than those with longer periods of disease duration.

“Presymptomatic treatment alters the natural history” of the disorder, the group found, although outcome data past age 1 are not yet available. Based on findings from a New York pilot program, they predicted that nationwide newborn screening would avert 33 deaths and 48 cases of children who were dependent on a ventilator among an annual cohort of four million births.

At the time of the evidence review, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, Utah, and Wisconsin initiated pilot programs or whole-population mandated screening for SMA. Of the three states that reported costs, all reported costs of $1 or less per screen.

The research for the evidence review was funded by a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. No disclosures were provided for evidence review group members.

—Tara Haelle

References

1. King NMP, Bishop CE. New treatments for serious conditions: ethical implications. Gene Ther. 2017;24(9):534-538.

2. Gerrity MS, Prasad V, Obley AJ. Concerns about the approval of nusinersen sodium by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):743-744.

3. Burgart AM, Magnus D, Tabor HK, et al. Ethical challenges confronted when providing nusinersen treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):188-192.

Does TBI Increase the Risk of Suicide?

Compared with the general population, people who seek medical attention for TBI may have almost twice the risk of suicide.

Residents of Denmark who seek medical attention for traumatic brain injury (TBI) have an increased risk of suicide, compared with the general Danish population without TBI, according to a study published in the August 14 issue of JAMA. “Additional analyses revealed that the risk of suicide was higher for individuals with severe TBI, numerous medical contacts, and longer hospital stays,” said lead author Trine Madsen, PhD. Individuals were at highest risk in the first six months after discharge, said Dr. Madsen, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the Danish Research Institute for Suicide Prevention in Hellerup.

A history of TBI previously has been associated with higher rates of self-harm, suicide, and death than are found in the general population. However, previous studies have been limited by methodological shortcomings, such as small sample sizes and low numbers of suicide cases with TBI. Dr. Madsen and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study using nationwide registers covering 7,418,391 individuals living in Denmark between 1980 and 2014 with 164,265,624 person-years’ follow-up. Of these people, 567,823 (7.6%) had a medical contact for TBI, which included mild TBI (ie, concussion), skull fracture without documented TBI, and severe TBI (ie, head injuries with evidence of structural brain injury).

Of 34,529 individuals who died by suicide, 3,536 (10.2%) had medical contact for TBI, including 2,701 for mild TBI, 174 for skull fracture without documented TBI, and 661 for severe TBI. The absolute suicide rate was 41 per 100,000 person-years among those with TBI versus 20 per 100,000 person-years among those with no diagnosis of TBI. After accounting for relevant covariates such as fractures not involving the skull, psychiatric diagnoses, and deliberate self-harm, the adjusted incidence ratio was 1.90.

This study “provides insights into the underappreciated relationship between TBI and suicide,” said Lee Goldstein, MD, PhD, and Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. “The results … point to an important clinical triad—TBI history, recent injury (especially with long hospital stays), and more numerous postinjury medical contacts for TBI—that serves as a red flag for increased suicide risk,” said Dr. Goldstein, who is affiliated with Boston University School of Medicine, and Dr. Diaz-Arrastia, of the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. The results “indicate that increased suicide risk is relevant across all TBI severity levels, including the far more common mild injuries. Clinicians, health care professionals, and mental health practitioners must take notice of this important information.”

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Goldstein L, Diaz-Arrastia R. Traumatic brain injury and risk of suicide. JAMA. 2018;320(6):554-556.

Madsen T, Erlangsen A, Orlovska S, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of suicide. JAMA. 2018;320(6):580-588.

Compared with the general population, people who seek medical attention for TBI may have almost twice the risk of suicide.

Compared with the general population, people who seek medical attention for TBI may have almost twice the risk of suicide.

Residents of Denmark who seek medical attention for traumatic brain injury (TBI) have an increased risk of suicide, compared with the general Danish population without TBI, according to a study published in the August 14 issue of JAMA. “Additional analyses revealed that the risk of suicide was higher for individuals with severe TBI, numerous medical contacts, and longer hospital stays,” said lead author Trine Madsen, PhD. Individuals were at highest risk in the first six months after discharge, said Dr. Madsen, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the Danish Research Institute for Suicide Prevention in Hellerup.

A history of TBI previously has been associated with higher rates of self-harm, suicide, and death than are found in the general population. However, previous studies have been limited by methodological shortcomings, such as small sample sizes and low numbers of suicide cases with TBI. Dr. Madsen and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study using nationwide registers covering 7,418,391 individuals living in Denmark between 1980 and 2014 with 164,265,624 person-years’ follow-up. Of these people, 567,823 (7.6%) had a medical contact for TBI, which included mild TBI (ie, concussion), skull fracture without documented TBI, and severe TBI (ie, head injuries with evidence of structural brain injury).

Of 34,529 individuals who died by suicide, 3,536 (10.2%) had medical contact for TBI, including 2,701 for mild TBI, 174 for skull fracture without documented TBI, and 661 for severe TBI. The absolute suicide rate was 41 per 100,000 person-years among those with TBI versus 20 per 100,000 person-years among those with no diagnosis of TBI. After accounting for relevant covariates such as fractures not involving the skull, psychiatric diagnoses, and deliberate self-harm, the adjusted incidence ratio was 1.90.

This study “provides insights into the underappreciated relationship between TBI and suicide,” said Lee Goldstein, MD, PhD, and Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. “The results … point to an important clinical triad—TBI history, recent injury (especially with long hospital stays), and more numerous postinjury medical contacts for TBI—that serves as a red flag for increased suicide risk,” said Dr. Goldstein, who is affiliated with Boston University School of Medicine, and Dr. Diaz-Arrastia, of the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. The results “indicate that increased suicide risk is relevant across all TBI severity levels, including the far more common mild injuries. Clinicians, health care professionals, and mental health practitioners must take notice of this important information.”

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Goldstein L, Diaz-Arrastia R. Traumatic brain injury and risk of suicide. JAMA. 2018;320(6):554-556.

Madsen T, Erlangsen A, Orlovska S, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of suicide. JAMA. 2018;320(6):580-588.

Residents of Denmark who seek medical attention for traumatic brain injury (TBI) have an increased risk of suicide, compared with the general Danish population without TBI, according to a study published in the August 14 issue of JAMA. “Additional analyses revealed that the risk of suicide was higher for individuals with severe TBI, numerous medical contacts, and longer hospital stays,” said lead author Trine Madsen, PhD. Individuals were at highest risk in the first six months after discharge, said Dr. Madsen, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the Danish Research Institute for Suicide Prevention in Hellerup.

A history of TBI previously has been associated with higher rates of self-harm, suicide, and death than are found in the general population. However, previous studies have been limited by methodological shortcomings, such as small sample sizes and low numbers of suicide cases with TBI. Dr. Madsen and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study using nationwide registers covering 7,418,391 individuals living in Denmark between 1980 and 2014 with 164,265,624 person-years’ follow-up. Of these people, 567,823 (7.6%) had a medical contact for TBI, which included mild TBI (ie, concussion), skull fracture without documented TBI, and severe TBI (ie, head injuries with evidence of structural brain injury).

Of 34,529 individuals who died by suicide, 3,536 (10.2%) had medical contact for TBI, including 2,701 for mild TBI, 174 for skull fracture without documented TBI, and 661 for severe TBI. The absolute suicide rate was 41 per 100,000 person-years among those with TBI versus 20 per 100,000 person-years among those with no diagnosis of TBI. After accounting for relevant covariates such as fractures not involving the skull, psychiatric diagnoses, and deliberate self-harm, the adjusted incidence ratio was 1.90.

This study “provides insights into the underappreciated relationship between TBI and suicide,” said Lee Goldstein, MD, PhD, and Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. “The results … point to an important clinical triad—TBI history, recent injury (especially with long hospital stays), and more numerous postinjury medical contacts for TBI—that serves as a red flag for increased suicide risk,” said Dr. Goldstein, who is affiliated with Boston University School of Medicine, and Dr. Diaz-Arrastia, of the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. The results “indicate that increased suicide risk is relevant across all TBI severity levels, including the far more common mild injuries. Clinicians, health care professionals, and mental health practitioners must take notice of this important information.”

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Goldstein L, Diaz-Arrastia R. Traumatic brain injury and risk of suicide. JAMA. 2018;320(6):554-556.

Madsen T, Erlangsen A, Orlovska S, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of suicide. JAMA. 2018;320(6):580-588.

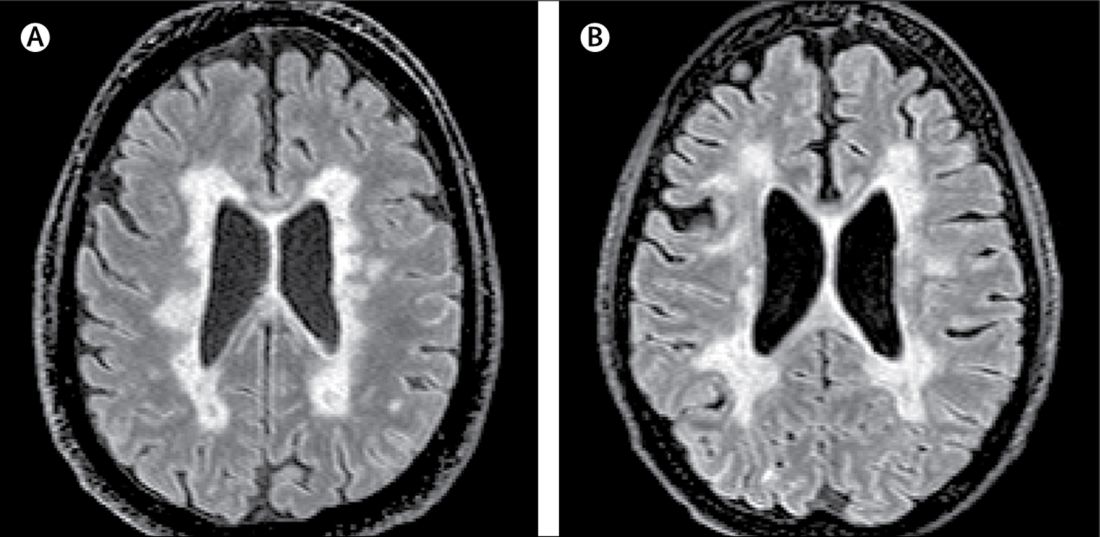

Serum Nf-L shows promise as biomarker for BMT response in MS

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Serum and cerebrospinal fluid Nf-L levels declines significantly after bone marrow transplant (P less than .05) and did not differ from the levels in controls.

Study details: An analysis of paired samples from 23 patients with multiple sclerosis and 5 controls.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

Source: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

Inherited mutations drive 12% of Nigerian breast cancer

About one in eight Nigerian women with breast cancer has an inherited mutation of the BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, or TP53 gene.

A new analysis of the Nigerian Breast Cancer Study confirmed that these inherited mutations drive about 12% of the country’s breast cancer cases. The findings could pave the way for the first large-scale national breast cancer gene screening program, wrote Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, MD, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“We suggest that genomic sequencing to identify women at extremely high risk of breast cancer could be a highly innovative approach to tailored risk management and life-saving interventions,” wrote Dr. Olopade, director of the Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics at the University of Chicago, and her colleagues. “Nigeria now has data to prioritize the integration of genetic testing into its cancer control plan. Women with an extremely high risk of breast cancer because of mutations in these genes can be identified inexpensively and unambiguously and offered interventions to reduce cancer risk.”

And, since about half of the sisters and daughters of affected women will carry the same mutation, such a screening program could reach far beyond every index patient identified, the investigators noted.

“If these women at very high risk can be identified either through their relatives with breast cancer or in the general population, resources can be focused particularly on their behalf. For as-yet unaffected women at high genetic risk, these resources would be intensive surveillance for early detection of breast cancer and, after childbearing is completed, the possibility of preventive salpingo-oophorectomy. Integrated population screening for cancer for all women is the goal, but focused outreach to women at extremely high risk represents an especially efficient use of resources and an attainable evidence-based global health approach.”

The Nigerian Breast Cancer Study enrolled 1,136 women with invasive breast cancer from 1998 to 2014. These were compared with 997 women without cancer, matched from the same communities. Genetic sequencing searched for mutations in both known and breast cancer genes.

Cases and controls were a mean of 47 years old; only 6% of cases reported a family history of breast cancer. Of 577 patients with information on tumor stage, 86% (497) were diagnosed at stage III (241) or IV (256).

Among the cases, 167 (14.7%) carried a mutation in a breast cancer risk gene, compared with 1.8% of controls. BRCA1 was the most common mutation, occurring in 7% of patients; these women were 23 times more likely to develop breast cancer than were those without the gene (odds ratio, 23.4). BRCA2 was the next most common, occurring in 4% of cases and conferring a nearly 11-fold increased risk (OR, 10.76). PALB2 occurred in 11 cases (1%) and no controls, and TP53 in four cases (0.4%).

Women with the BRCA1 mutation were diagnosed at a significantly younger age than were other patients (42.6 vs. 47.9 years), as were carriers of the TP53 mutation (32.8 vs. 47.6 years).

Ten other genes (ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CHEK1, CHEK2, GEN1, NBN, RAD51C, RAD51D, and XRCC2) carried a mutation in at least one patient each. “When limited to mutations in the four high-risk genes, 11%-12% of cases in this study carried a loss-of-function variant.”

Dr. Olopade had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Olopade et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.3977.

The findings of the Nigerian Breast Cancer Study make a case for large-scale breast cancer gene screening. But even in a wealthy country with good infrastructure, such a program would be dauntingly complex, Ophira Ginsburg, MD, and Paul Brennan, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Given the estimated 40,983 women in Nigeria younger than age 65 years who will be newly diagnosed with breast cancer in 2030, the estimated mutation carrier frequency for a high-risk gene of 11%-12% translates to approximately 5,000 women with breast cancer each year who might benefit directly from tailored risk-reducing strategies. Moreover, 50% of these women’s sisters and daughters would also stand to benefit,” they wrote.

However, 32 million women would need to be screened to find the 220,000 with one of the mutations – a task that is “clearly beyond the scope of most countries.

“Furthermore, women with pathogenic variants would require intensive follow-up and intervention strategies to reduce their risk of developing breast, ovarian/fallopian tube, and potentially other cancers depending on the gene involved. Importantly, this approach would not address the larger problem of the high breast cancer mortality among the vast majority of women without a pathogenic variant but who make up approximately 85% of the breast cancer burden.”

The World Health Organization recognizes this challenge; the agency doesn’t even recommend mammogram-based population screening unless there is a basic, reliable infrastructure including electricity, quality-assurance measures, referral and recall mechanisms, and monitoring and evaluation frameworks. But WHO does suggest some core elements to guide a country’s comprehensive cancer management strategy, including:

• Considering the whole continuum from prevention to palliation.

• Providing a sustainable strategic plan on the basis of the country’s cancer burden, risk factor prevalence, and the resources available to implement the plan.

• Developing an evidence-based approach generated by population-based cancer registries.

“As many countries improve their cancer systems, investing in human resources, infrastructure, monitoring, and evaluation, it is timely to consider how to evaluate readiness to undertake a population-level cancer genetics intervention and consider the core elements that should be in place to make a substantive effect on cancer mortality.”

Dr. Ginsburg is with the Perlmutter Cancer Center of New York University. Dr. Brennan is with the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

The findings of the Nigerian Breast Cancer Study make a case for large-scale breast cancer gene screening. But even in a wealthy country with good infrastructure, such a program would be dauntingly complex, Ophira Ginsburg, MD, and Paul Brennan, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Given the estimated 40,983 women in Nigeria younger than age 65 years who will be newly diagnosed with breast cancer in 2030, the estimated mutation carrier frequency for a high-risk gene of 11%-12% translates to approximately 5,000 women with breast cancer each year who might benefit directly from tailored risk-reducing strategies. Moreover, 50% of these women’s sisters and daughters would also stand to benefit,” they wrote.

However, 32 million women would need to be screened to find the 220,000 with one of the mutations – a task that is “clearly beyond the scope of most countries.

“Furthermore, women with pathogenic variants would require intensive follow-up and intervention strategies to reduce their risk of developing breast, ovarian/fallopian tube, and potentially other cancers depending on the gene involved. Importantly, this approach would not address the larger problem of the high breast cancer mortality among the vast majority of women without a pathogenic variant but who make up approximately 85% of the breast cancer burden.”

The World Health Organization recognizes this challenge; the agency doesn’t even recommend mammogram-based population screening unless there is a basic, reliable infrastructure including electricity, quality-assurance measures, referral and recall mechanisms, and monitoring and evaluation frameworks. But WHO does suggest some core elements to guide a country’s comprehensive cancer management strategy, including:

• Considering the whole continuum from prevention to palliation.

• Providing a sustainable strategic plan on the basis of the country’s cancer burden, risk factor prevalence, and the resources available to implement the plan.

• Developing an evidence-based approach generated by population-based cancer registries.

“As many countries improve their cancer systems, investing in human resources, infrastructure, monitoring, and evaluation, it is timely to consider how to evaluate readiness to undertake a population-level cancer genetics intervention and consider the core elements that should be in place to make a substantive effect on cancer mortality.”

Dr. Ginsburg is with the Perlmutter Cancer Center of New York University. Dr. Brennan is with the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

The findings of the Nigerian Breast Cancer Study make a case for large-scale breast cancer gene screening. But even in a wealthy country with good infrastructure, such a program would be dauntingly complex, Ophira Ginsburg, MD, and Paul Brennan, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Given the estimated 40,983 women in Nigeria younger than age 65 years who will be newly diagnosed with breast cancer in 2030, the estimated mutation carrier frequency for a high-risk gene of 11%-12% translates to approximately 5,000 women with breast cancer each year who might benefit directly from tailored risk-reducing strategies. Moreover, 50% of these women’s sisters and daughters would also stand to benefit,” they wrote.

However, 32 million women would need to be screened to find the 220,000 with one of the mutations – a task that is “clearly beyond the scope of most countries.

“Furthermore, women with pathogenic variants would require intensive follow-up and intervention strategies to reduce their risk of developing breast, ovarian/fallopian tube, and potentially other cancers depending on the gene involved. Importantly, this approach would not address the larger problem of the high breast cancer mortality among the vast majority of women without a pathogenic variant but who make up approximately 85% of the breast cancer burden.”

The World Health Organization recognizes this challenge; the agency doesn’t even recommend mammogram-based population screening unless there is a basic, reliable infrastructure including electricity, quality-assurance measures, referral and recall mechanisms, and monitoring and evaluation frameworks. But WHO does suggest some core elements to guide a country’s comprehensive cancer management strategy, including:

• Considering the whole continuum from prevention to palliation.

• Providing a sustainable strategic plan on the basis of the country’s cancer burden, risk factor prevalence, and the resources available to implement the plan.

• Developing an evidence-based approach generated by population-based cancer registries.

“As many countries improve their cancer systems, investing in human resources, infrastructure, monitoring, and evaluation, it is timely to consider how to evaluate readiness to undertake a population-level cancer genetics intervention and consider the core elements that should be in place to make a substantive effect on cancer mortality.”

Dr. Ginsburg is with the Perlmutter Cancer Center of New York University. Dr. Brennan is with the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

About one in eight Nigerian women with breast cancer has an inherited mutation of the BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, or TP53 gene.

A new analysis of the Nigerian Breast Cancer Study confirmed that these inherited mutations drive about 12% of the country’s breast cancer cases. The findings could pave the way for the first large-scale national breast cancer gene screening program, wrote Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, MD, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“We suggest that genomic sequencing to identify women at extremely high risk of breast cancer could be a highly innovative approach to tailored risk management and life-saving interventions,” wrote Dr. Olopade, director of the Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics at the University of Chicago, and her colleagues. “Nigeria now has data to prioritize the integration of genetic testing into its cancer control plan. Women with an extremely high risk of breast cancer because of mutations in these genes can be identified inexpensively and unambiguously and offered interventions to reduce cancer risk.”

And, since about half of the sisters and daughters of affected women will carry the same mutation, such a screening program could reach far beyond every index patient identified, the investigators noted.

“If these women at very high risk can be identified either through their relatives with breast cancer or in the general population, resources can be focused particularly on their behalf. For as-yet unaffected women at high genetic risk, these resources would be intensive surveillance for early detection of breast cancer and, after childbearing is completed, the possibility of preventive salpingo-oophorectomy. Integrated population screening for cancer for all women is the goal, but focused outreach to women at extremely high risk represents an especially efficient use of resources and an attainable evidence-based global health approach.”

The Nigerian Breast Cancer Study enrolled 1,136 women with invasive breast cancer from 1998 to 2014. These were compared with 997 women without cancer, matched from the same communities. Genetic sequencing searched for mutations in both known and breast cancer genes.