User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Population-level rate of SUDEP may have decreased

NEW ORLEANS – according to data described at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Whether this decrease resulted from an improved understanding of SUDEP risk or a focus on risk-reduction strategies is unknown, said Daniel Friedman, MD, associate professor of neurology at the New York University Langone Health.

In addition, the rates of SUDEP in various populations differ according to their socioeconomic status. Differences in access to care are a potential, but unconfirmed, explanation for this association, said Dr. Friedman. Another possible explanation is that confounders such as mental health disorders, substance abuse, and insufficient social support affect individuals’ ability to manage their disorder.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues initially examined SUDEP rates over time in a cohort of patients who received vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) implantation for drug-resistant epilepsy. They analyzed data for 40,443 patients who underwent surgery during 1988-2012. The age-adjusted SUDEP rate per 1,000 person-years of follow-up decreased significantly from 2.47 in years 1-2 to 1.68 in years 3-10. “There was no control group, so we couldn’t necessarily attribute the SUDEP rate reduction to the intervention,” said Dr. Friedman. A study by Tomson et al of patients with epilepsy who received VNS implantation had similar findings.

The literature about the mechanisms of SUDEP and reduction of SUDEP risk has increased in recent years. Neurologists have advocated for greater disclosure to patients of SUDEP risk, as well as better risk counseling. Dr. Friedman and his colleagues decided to investigate whether these factors have affected the risk of SUDEP during the past decade.

They retrospectively examined data for people whose deaths had been investigated at medical examiner’s offices in New York City, San Diego County, and Maryland. They focused on decedents for whom epilepsy or seizure was listed as a cause or contributor to death or as a comorbid condition on the death certificate. They reviewed all available reports, including investigator notes, autopsy reports, and medical records. Next, Dr. Friedman and his colleagues calculated the annual SUDEP rate as a proportion of the general population, estimated using annual Census and American Community Survey data. They used the Mann-Kendall test to analyze the trends in SUDEP rate during 2009-2015.

Of 1,466 deaths in people with epilepsy during this period, 1,124 were classified as definite SUDEP, probable SUDEP, or near SUDEP. Approximately 63% of SUDEP cases were male, and 45% were African-American. The mean age at death was 38 years.

Dr. Friedman’s group found a significant decrease in the overall incidence of SUDEP in the total population during 2009-2015. When they examined the three regions separately, they found decreases in SUDEP incidence in New York City and Maryland, but not in San Diego County. They found no difference in SUDEP rates by season or by day of the week.

In a subsequent analysis, Dr. Friedman and his colleagues adjudicated all deaths related to seizure and epilepsy in the three regions during 2009-2010 and 2014-2015 and identified all cases of definite and probable SUDEP. The estimated rate of SUDEP decreased by about 36% from the first period to the second period. SUDEP rates as a proportion of the total population in those regions also declined.

The investigators also examined differences in estimated SUDEP rates in the United States according to median household income. In New York, the zip codes with the highest SUDEP rates tended to have the lowest median household incomes. The zip codes in the lowest quartile of family household income had a SUDEP rate more than twice as high as that in the zip codes in the highest income quartile. This association held true for the period from 2009-2010 and for 2014-2015.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues received funding from Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures, which is affiliated with the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and NYU Langone Health.

SOURCE: Cihan E et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.419.

NEW ORLEANS – according to data described at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Whether this decrease resulted from an improved understanding of SUDEP risk or a focus on risk-reduction strategies is unknown, said Daniel Friedman, MD, associate professor of neurology at the New York University Langone Health.

In addition, the rates of SUDEP in various populations differ according to their socioeconomic status. Differences in access to care are a potential, but unconfirmed, explanation for this association, said Dr. Friedman. Another possible explanation is that confounders such as mental health disorders, substance abuse, and insufficient social support affect individuals’ ability to manage their disorder.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues initially examined SUDEP rates over time in a cohort of patients who received vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) implantation for drug-resistant epilepsy. They analyzed data for 40,443 patients who underwent surgery during 1988-2012. The age-adjusted SUDEP rate per 1,000 person-years of follow-up decreased significantly from 2.47 in years 1-2 to 1.68 in years 3-10. “There was no control group, so we couldn’t necessarily attribute the SUDEP rate reduction to the intervention,” said Dr. Friedman. A study by Tomson et al of patients with epilepsy who received VNS implantation had similar findings.

The literature about the mechanisms of SUDEP and reduction of SUDEP risk has increased in recent years. Neurologists have advocated for greater disclosure to patients of SUDEP risk, as well as better risk counseling. Dr. Friedman and his colleagues decided to investigate whether these factors have affected the risk of SUDEP during the past decade.

They retrospectively examined data for people whose deaths had been investigated at medical examiner’s offices in New York City, San Diego County, and Maryland. They focused on decedents for whom epilepsy or seizure was listed as a cause or contributor to death or as a comorbid condition on the death certificate. They reviewed all available reports, including investigator notes, autopsy reports, and medical records. Next, Dr. Friedman and his colleagues calculated the annual SUDEP rate as a proportion of the general population, estimated using annual Census and American Community Survey data. They used the Mann-Kendall test to analyze the trends in SUDEP rate during 2009-2015.

Of 1,466 deaths in people with epilepsy during this period, 1,124 were classified as definite SUDEP, probable SUDEP, or near SUDEP. Approximately 63% of SUDEP cases were male, and 45% were African-American. The mean age at death was 38 years.

Dr. Friedman’s group found a significant decrease in the overall incidence of SUDEP in the total population during 2009-2015. When they examined the three regions separately, they found decreases in SUDEP incidence in New York City and Maryland, but not in San Diego County. They found no difference in SUDEP rates by season or by day of the week.

In a subsequent analysis, Dr. Friedman and his colleagues adjudicated all deaths related to seizure and epilepsy in the three regions during 2009-2010 and 2014-2015 and identified all cases of definite and probable SUDEP. The estimated rate of SUDEP decreased by about 36% from the first period to the second period. SUDEP rates as a proportion of the total population in those regions also declined.

The investigators also examined differences in estimated SUDEP rates in the United States according to median household income. In New York, the zip codes with the highest SUDEP rates tended to have the lowest median household incomes. The zip codes in the lowest quartile of family household income had a SUDEP rate more than twice as high as that in the zip codes in the highest income quartile. This association held true for the period from 2009-2010 and for 2014-2015.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues received funding from Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures, which is affiliated with the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and NYU Langone Health.

SOURCE: Cihan E et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.419.

NEW ORLEANS – according to data described at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Whether this decrease resulted from an improved understanding of SUDEP risk or a focus on risk-reduction strategies is unknown, said Daniel Friedman, MD, associate professor of neurology at the New York University Langone Health.

In addition, the rates of SUDEP in various populations differ according to their socioeconomic status. Differences in access to care are a potential, but unconfirmed, explanation for this association, said Dr. Friedman. Another possible explanation is that confounders such as mental health disorders, substance abuse, and insufficient social support affect individuals’ ability to manage their disorder.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues initially examined SUDEP rates over time in a cohort of patients who received vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) implantation for drug-resistant epilepsy. They analyzed data for 40,443 patients who underwent surgery during 1988-2012. The age-adjusted SUDEP rate per 1,000 person-years of follow-up decreased significantly from 2.47 in years 1-2 to 1.68 in years 3-10. “There was no control group, so we couldn’t necessarily attribute the SUDEP rate reduction to the intervention,” said Dr. Friedman. A study by Tomson et al of patients with epilepsy who received VNS implantation had similar findings.

The literature about the mechanisms of SUDEP and reduction of SUDEP risk has increased in recent years. Neurologists have advocated for greater disclosure to patients of SUDEP risk, as well as better risk counseling. Dr. Friedman and his colleagues decided to investigate whether these factors have affected the risk of SUDEP during the past decade.

They retrospectively examined data for people whose deaths had been investigated at medical examiner’s offices in New York City, San Diego County, and Maryland. They focused on decedents for whom epilepsy or seizure was listed as a cause or contributor to death or as a comorbid condition on the death certificate. They reviewed all available reports, including investigator notes, autopsy reports, and medical records. Next, Dr. Friedman and his colleagues calculated the annual SUDEP rate as a proportion of the general population, estimated using annual Census and American Community Survey data. They used the Mann-Kendall test to analyze the trends in SUDEP rate during 2009-2015.

Of 1,466 deaths in people with epilepsy during this period, 1,124 were classified as definite SUDEP, probable SUDEP, or near SUDEP. Approximately 63% of SUDEP cases were male, and 45% were African-American. The mean age at death was 38 years.

Dr. Friedman’s group found a significant decrease in the overall incidence of SUDEP in the total population during 2009-2015. When they examined the three regions separately, they found decreases in SUDEP incidence in New York City and Maryland, but not in San Diego County. They found no difference in SUDEP rates by season or by day of the week.

In a subsequent analysis, Dr. Friedman and his colleagues adjudicated all deaths related to seizure and epilepsy in the three regions during 2009-2010 and 2014-2015 and identified all cases of definite and probable SUDEP. The estimated rate of SUDEP decreased by about 36% from the first period to the second period. SUDEP rates as a proportion of the total population in those regions also declined.

The investigators also examined differences in estimated SUDEP rates in the United States according to median household income. In New York, the zip codes with the highest SUDEP rates tended to have the lowest median household incomes. The zip codes in the lowest quartile of family household income had a SUDEP rate more than twice as high as that in the zip codes in the highest income quartile. This association held true for the period from 2009-2010 and for 2014-2015.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues received funding from Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures, which is affiliated with the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and NYU Langone Health.

SOURCE: Cihan E et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.419.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: Data indicate a decline over time in the incidence of SUDEP.

Major finding: The incidence of SUDEP declined by 36% from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of medical examiner data on 1,466 deaths in people with epilepsy.

Disclosures: Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures provided funding for the study.

Source: Cihan E et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.419.

Looking back to reflect on how far we’ve come

During the holiday break I took some time to organize a lot of old family pictures: deleting duplicates, merging those I pulled off my dad’s computer when he died (which was over 5 years ago), importing ones I took with old digital cameras that were in separate folders ... a bunch of stuff. Some were even childhood pics of me that had been scanned into digital formats. Lots of gigabytes. Lots of time spent watching the little “importing” wheel spin.

As I scrolled through them – literally 5,891 pics and 679 videos – I watched as it became more than a bunch of photos. I watched myself grow up, go through medical school, get married, raise a family. My hair went from brown to gray and receding. My kids went from toddlers to young adults about to leave for college.

It was the story of my life. Without meaning to, it’s what the pictures had become.

It was late at night, but I kept scrolling back and forth. My parents, wife, and others aged in front of me.

Looking in the mirror, or seeing others each day, we never notice the slow changes that time brings. You don’t really see it just thumbing through old photos, either.

But here, in the photos app (something entirely undreamed of in my childhood), I was watching it like it was a movie. Even childhood pictures of my parents. Them dating and getting married. Holding me after bringing me home from the hospital.

I’m certainly not the first to have these thoughts, nor will I be the last. We all go through life in a somewhat organized yet haphazard way, and only when looking backward do we really see how far we’ve come ... often realizing we’re past the halfway point.

Not that this is a bad thing. I mean, that’s life on Earth. It has its good and bad, and aging is part of the rules for all of us.

I suppose you could look at this in terms of our profession. We all (or at least most of us) start out as hospital patients. As we get older and become doctors, hopefully we need to see our own kind less often while at the same time seeing others as patients. As time goes by, most of us start to need to see doctors again, and as we retire and stop practicing medicine, we move back toward being patients ourselves.

For me, the pictures bring back memories and strike emotions in the way hearing or reading stories never can. They give new life to long-forgotten thoughts. Happy and sad, but overall a feeling of contentment that, so far, I feel like I’ve done more good than bad, more right than wrong.

I hope I always feel that way.

I hope everyone else does, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

During the holiday break I took some time to organize a lot of old family pictures: deleting duplicates, merging those I pulled off my dad’s computer when he died (which was over 5 years ago), importing ones I took with old digital cameras that were in separate folders ... a bunch of stuff. Some were even childhood pics of me that had been scanned into digital formats. Lots of gigabytes. Lots of time spent watching the little “importing” wheel spin.

As I scrolled through them – literally 5,891 pics and 679 videos – I watched as it became more than a bunch of photos. I watched myself grow up, go through medical school, get married, raise a family. My hair went from brown to gray and receding. My kids went from toddlers to young adults about to leave for college.

It was the story of my life. Without meaning to, it’s what the pictures had become.

It was late at night, but I kept scrolling back and forth. My parents, wife, and others aged in front of me.

Looking in the mirror, or seeing others each day, we never notice the slow changes that time brings. You don’t really see it just thumbing through old photos, either.

But here, in the photos app (something entirely undreamed of in my childhood), I was watching it like it was a movie. Even childhood pictures of my parents. Them dating and getting married. Holding me after bringing me home from the hospital.

I’m certainly not the first to have these thoughts, nor will I be the last. We all go through life in a somewhat organized yet haphazard way, and only when looking backward do we really see how far we’ve come ... often realizing we’re past the halfway point.

Not that this is a bad thing. I mean, that’s life on Earth. It has its good and bad, and aging is part of the rules for all of us.

I suppose you could look at this in terms of our profession. We all (or at least most of us) start out as hospital patients. As we get older and become doctors, hopefully we need to see our own kind less often while at the same time seeing others as patients. As time goes by, most of us start to need to see doctors again, and as we retire and stop practicing medicine, we move back toward being patients ourselves.

For me, the pictures bring back memories and strike emotions in the way hearing or reading stories never can. They give new life to long-forgotten thoughts. Happy and sad, but overall a feeling of contentment that, so far, I feel like I’ve done more good than bad, more right than wrong.

I hope I always feel that way.

I hope everyone else does, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

During the holiday break I took some time to organize a lot of old family pictures: deleting duplicates, merging those I pulled off my dad’s computer when he died (which was over 5 years ago), importing ones I took with old digital cameras that were in separate folders ... a bunch of stuff. Some were even childhood pics of me that had been scanned into digital formats. Lots of gigabytes. Lots of time spent watching the little “importing” wheel spin.

As I scrolled through them – literally 5,891 pics and 679 videos – I watched as it became more than a bunch of photos. I watched myself grow up, go through medical school, get married, raise a family. My hair went from brown to gray and receding. My kids went from toddlers to young adults about to leave for college.

It was the story of my life. Without meaning to, it’s what the pictures had become.

It was late at night, but I kept scrolling back and forth. My parents, wife, and others aged in front of me.

Looking in the mirror, or seeing others each day, we never notice the slow changes that time brings. You don’t really see it just thumbing through old photos, either.

But here, in the photos app (something entirely undreamed of in my childhood), I was watching it like it was a movie. Even childhood pictures of my parents. Them dating and getting married. Holding me after bringing me home from the hospital.

I’m certainly not the first to have these thoughts, nor will I be the last. We all go through life in a somewhat organized yet haphazard way, and only when looking backward do we really see how far we’ve come ... often realizing we’re past the halfway point.

Not that this is a bad thing. I mean, that’s life on Earth. It has its good and bad, and aging is part of the rules for all of us.

I suppose you could look at this in terms of our profession. We all (or at least most of us) start out as hospital patients. As we get older and become doctors, hopefully we need to see our own kind less often while at the same time seeing others as patients. As time goes by, most of us start to need to see doctors again, and as we retire and stop practicing medicine, we move back toward being patients ourselves.

For me, the pictures bring back memories and strike emotions in the way hearing or reading stories never can. They give new life to long-forgotten thoughts. Happy and sad, but overall a feeling of contentment that, so far, I feel like I’ve done more good than bad, more right than wrong.

I hope I always feel that way.

I hope everyone else does, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Ray Barfield Part II: Philosophy and Medicine

In part I of the conversation, Dr. Barfield and MDedge host Nick Andrews discussed physician burnout and Dr. Barfield’s journey back to medicine. In this episode, Dr. Barfield and Nick discuss philosophy and science.

You can listen to part I of this conversation here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

In part I of the conversation, Dr. Barfield and MDedge host Nick Andrews discussed physician burnout and Dr. Barfield’s journey back to medicine. In this episode, Dr. Barfield and Nick discuss philosophy and science.

You can listen to part I of this conversation here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

In part I of the conversation, Dr. Barfield and MDedge host Nick Andrews discussed physician burnout and Dr. Barfield’s journey back to medicine. In this episode, Dr. Barfield and Nick discuss philosophy and science.

You can listen to part I of this conversation here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

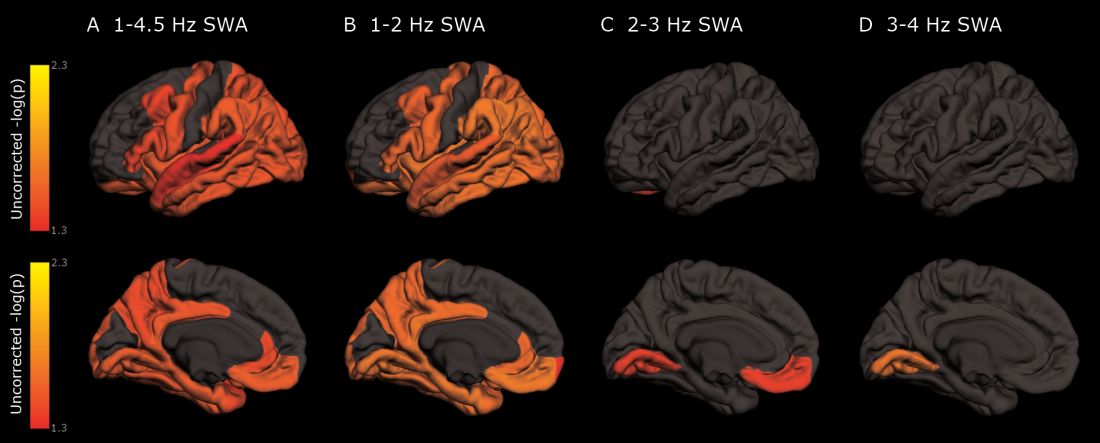

Deep sleep decreases, Alzheimer’s increases

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Sleep disorders in children with ADHD treated with off-label medications

Sleep problems in children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder are treated with a variety of medications, many off label for sleep and unstudied for safety and effectiveness in children, a study of Medicaid prescriptions has found.

“Sleep disorders coexist with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for many children and are associated with neuropsychiatric, physiologic, and medication-related outcomes,” wrote Tracy Klein, PhD, of Washington State University, Vancouver, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Pediatric Health Care. These patients can have sleep disordered breathing and behavioral issues occurring around bedtime. Known adverse effects of the stimulant and nonstimulant medications used to treat ADHD can include sleep disturbance, delayed circadian rhythm, insomnia, and somnolence. Yet, research on both sleep problems in children with ADHD and prescribing patterns is scanty, according to the investigators.

Dr. Klein and her colleagues conducted a study aimed at identifying the off-label medications being prescribed to potentiate sleep in children with ADHD, and the characteristics of the children and their prescribers. They used 5 years of pharmacy claims for children in Oregon insured through Medicaid and had a provider diagnosis of ADHD during Jan. 1, 2012, to Dec. 31, 2016. The children were aged 3-18 years and the prescriptions measured were the number of 30-day prescriptions. Prescribers were identified by national provider identifier taxonomies (nurse, physician, other prescriber), and classified as either generalist or specialist. The medications were classified as controlled or uncontrolled as determined by Title 21 of the U.S. Controlled Substances Act.

The data yielded 14,567 prescriptions for 2,518 children for a 30-day supply of medication known to potentiate sleep but off-label for children. Children aged 3-11 years comprised about 38% of these patients. Some children were prescribed more than one of these medications. Medications specifically on label for sleep but not indicated for children were not included. Those medications indicated for comorbid conditions and those indicated for ADHD that specifically cause somnolence were excluded.

The uncontrolled medications prescribed in this sample were amitriptyline, doxepin, hydroxyzine, low-dose quetiapine, and trazodone. The controlled medications identified were clonazepam and lorazepam, and a few prescriptions for phenobarbital.

Most of the prescriptions (63.8%) went to older children aged 12-18 years and most prescriptions (66.3%) went to males. The most commonly prescribed noncontrolled medication was trazodone (5,190 prescriptions), followed by hydroxyzine (2,539), and quetiapine (2,402). The most frequently prescribed controlled medication was clonazepam (2,145), followed by lorazepam (534).

Specialist prescribers wrote most of the prescriptions for this patient group, but no differences were found in prescribing patterns between specialists and generalists.

Dr. Klein and her colleagues noted that 871 unique children were prescribed 5,190 30-day−supply prescriptions for trazodone, including 23 children under age 5. Trazodone is a serotonin modulator indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder, but has not been studied for safety and efficacy in children and has no Food and Drug Administration indication for children. “Hydroxyzine, quetiapine, and amitriptyline also were prescribed for a large number of children, including some for children as young as 3 years, despite lack of approval for use to induce to sleep and increased potential for significant adverse reactions in children,” they wrote.

Dr. Klein suggested that prescribers receive pressure from families to “do something” for their children, who may be disruptive day and night. “Prescribers may be unaware that trazodone, which is commonly used in practice, has never been approved for treatment of insomnia in children or adults. Insurance may not adequately fund other options, such as extensive behavioral therapy,” she stated in an interview. These medications come with some risk for children, Dr. Klein noted.

especially if their reaction to it is behavioral.” There is also potential for unanticipated drug interactions between off-label medications prescribed for sleep and drugs prescribed to treat ADHD.

This study has limitations related to the absence of detailed clinical explanatory information found in claims data. Information on adherence to treatment and adverse events, for example, is not contained in claims data. The study does not address the overall rates of sleep disorders in children with ADHD nor the percentage of children with ADHD who are prescribed any medication to potentiate sleep but looks at which off-label drugs are being prescribed, to which children, and by whom.

“Most medications prescribed in this study, used to induce sleep or treat insomnia, have not been studied for safety and efficacy in children, and their use should not be extrapolated from adult studies,” the researchers concluded.

They reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Klein T et al. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.10.002.

Sleep problems in children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder are treated with a variety of medications, many off label for sleep and unstudied for safety and effectiveness in children, a study of Medicaid prescriptions has found.

“Sleep disorders coexist with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for many children and are associated with neuropsychiatric, physiologic, and medication-related outcomes,” wrote Tracy Klein, PhD, of Washington State University, Vancouver, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Pediatric Health Care. These patients can have sleep disordered breathing and behavioral issues occurring around bedtime. Known adverse effects of the stimulant and nonstimulant medications used to treat ADHD can include sleep disturbance, delayed circadian rhythm, insomnia, and somnolence. Yet, research on both sleep problems in children with ADHD and prescribing patterns is scanty, according to the investigators.

Dr. Klein and her colleagues conducted a study aimed at identifying the off-label medications being prescribed to potentiate sleep in children with ADHD, and the characteristics of the children and their prescribers. They used 5 years of pharmacy claims for children in Oregon insured through Medicaid and had a provider diagnosis of ADHD during Jan. 1, 2012, to Dec. 31, 2016. The children were aged 3-18 years and the prescriptions measured were the number of 30-day prescriptions. Prescribers were identified by national provider identifier taxonomies (nurse, physician, other prescriber), and classified as either generalist or specialist. The medications were classified as controlled or uncontrolled as determined by Title 21 of the U.S. Controlled Substances Act.

The data yielded 14,567 prescriptions for 2,518 children for a 30-day supply of medication known to potentiate sleep but off-label for children. Children aged 3-11 years comprised about 38% of these patients. Some children were prescribed more than one of these medications. Medications specifically on label for sleep but not indicated for children were not included. Those medications indicated for comorbid conditions and those indicated for ADHD that specifically cause somnolence were excluded.

The uncontrolled medications prescribed in this sample were amitriptyline, doxepin, hydroxyzine, low-dose quetiapine, and trazodone. The controlled medications identified were clonazepam and lorazepam, and a few prescriptions for phenobarbital.

Most of the prescriptions (63.8%) went to older children aged 12-18 years and most prescriptions (66.3%) went to males. The most commonly prescribed noncontrolled medication was trazodone (5,190 prescriptions), followed by hydroxyzine (2,539), and quetiapine (2,402). The most frequently prescribed controlled medication was clonazepam (2,145), followed by lorazepam (534).

Specialist prescribers wrote most of the prescriptions for this patient group, but no differences were found in prescribing patterns between specialists and generalists.

Dr. Klein and her colleagues noted that 871 unique children were prescribed 5,190 30-day−supply prescriptions for trazodone, including 23 children under age 5. Trazodone is a serotonin modulator indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder, but has not been studied for safety and efficacy in children and has no Food and Drug Administration indication for children. “Hydroxyzine, quetiapine, and amitriptyline also were prescribed for a large number of children, including some for children as young as 3 years, despite lack of approval for use to induce to sleep and increased potential for significant adverse reactions in children,” they wrote.

Dr. Klein suggested that prescribers receive pressure from families to “do something” for their children, who may be disruptive day and night. “Prescribers may be unaware that trazodone, which is commonly used in practice, has never been approved for treatment of insomnia in children or adults. Insurance may not adequately fund other options, such as extensive behavioral therapy,” she stated in an interview. These medications come with some risk for children, Dr. Klein noted.

especially if their reaction to it is behavioral.” There is also potential for unanticipated drug interactions between off-label medications prescribed for sleep and drugs prescribed to treat ADHD.

This study has limitations related to the absence of detailed clinical explanatory information found in claims data. Information on adherence to treatment and adverse events, for example, is not contained in claims data. The study does not address the overall rates of sleep disorders in children with ADHD nor the percentage of children with ADHD who are prescribed any medication to potentiate sleep but looks at which off-label drugs are being prescribed, to which children, and by whom.

“Most medications prescribed in this study, used to induce sleep or treat insomnia, have not been studied for safety and efficacy in children, and their use should not be extrapolated from adult studies,” the researchers concluded.

They reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Klein T et al. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.10.002.

Sleep problems in children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder are treated with a variety of medications, many off label for sleep and unstudied for safety and effectiveness in children, a study of Medicaid prescriptions has found.

“Sleep disorders coexist with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for many children and are associated with neuropsychiatric, physiologic, and medication-related outcomes,” wrote Tracy Klein, PhD, of Washington State University, Vancouver, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Pediatric Health Care. These patients can have sleep disordered breathing and behavioral issues occurring around bedtime. Known adverse effects of the stimulant and nonstimulant medications used to treat ADHD can include sleep disturbance, delayed circadian rhythm, insomnia, and somnolence. Yet, research on both sleep problems in children with ADHD and prescribing patterns is scanty, according to the investigators.

Dr. Klein and her colleagues conducted a study aimed at identifying the off-label medications being prescribed to potentiate sleep in children with ADHD, and the characteristics of the children and their prescribers. They used 5 years of pharmacy claims for children in Oregon insured through Medicaid and had a provider diagnosis of ADHD during Jan. 1, 2012, to Dec. 31, 2016. The children were aged 3-18 years and the prescriptions measured were the number of 30-day prescriptions. Prescribers were identified by national provider identifier taxonomies (nurse, physician, other prescriber), and classified as either generalist or specialist. The medications were classified as controlled or uncontrolled as determined by Title 21 of the U.S. Controlled Substances Act.

The data yielded 14,567 prescriptions for 2,518 children for a 30-day supply of medication known to potentiate sleep but off-label for children. Children aged 3-11 years comprised about 38% of these patients. Some children were prescribed more than one of these medications. Medications specifically on label for sleep but not indicated for children were not included. Those medications indicated for comorbid conditions and those indicated for ADHD that specifically cause somnolence were excluded.

The uncontrolled medications prescribed in this sample were amitriptyline, doxepin, hydroxyzine, low-dose quetiapine, and trazodone. The controlled medications identified were clonazepam and lorazepam, and a few prescriptions for phenobarbital.

Most of the prescriptions (63.8%) went to older children aged 12-18 years and most prescriptions (66.3%) went to males. The most commonly prescribed noncontrolled medication was trazodone (5,190 prescriptions), followed by hydroxyzine (2,539), and quetiapine (2,402). The most frequently prescribed controlled medication was clonazepam (2,145), followed by lorazepam (534).

Specialist prescribers wrote most of the prescriptions for this patient group, but no differences were found in prescribing patterns between specialists and generalists.

Dr. Klein and her colleagues noted that 871 unique children were prescribed 5,190 30-day−supply prescriptions for trazodone, including 23 children under age 5. Trazodone is a serotonin modulator indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder, but has not been studied for safety and efficacy in children and has no Food and Drug Administration indication for children. “Hydroxyzine, quetiapine, and amitriptyline also were prescribed for a large number of children, including some for children as young as 3 years, despite lack of approval for use to induce to sleep and increased potential for significant adverse reactions in children,” they wrote.

Dr. Klein suggested that prescribers receive pressure from families to “do something” for their children, who may be disruptive day and night. “Prescribers may be unaware that trazodone, which is commonly used in practice, has never been approved for treatment of insomnia in children or adults. Insurance may not adequately fund other options, such as extensive behavioral therapy,” she stated in an interview. These medications come with some risk for children, Dr. Klein noted.

especially if their reaction to it is behavioral.” There is also potential for unanticipated drug interactions between off-label medications prescribed for sleep and drugs prescribed to treat ADHD.

This study has limitations related to the absence of detailed clinical explanatory information found in claims data. Information on adherence to treatment and adverse events, for example, is not contained in claims data. The study does not address the overall rates of sleep disorders in children with ADHD nor the percentage of children with ADHD who are prescribed any medication to potentiate sleep but looks at which off-label drugs are being prescribed, to which children, and by whom.

“Most medications prescribed in this study, used to induce sleep or treat insomnia, have not been studied for safety and efficacy in children, and their use should not be extrapolated from adult studies,” the researchers concluded.

They reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Klein T et al. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.10.002.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC HEALTH CARE

Key clinical point: The most commonly prescribed off-label medications prescribed to children were trazodone (5,190), hydroxyzine (2,539), quetiapine (2,402), and clonazepam (2,145).

Major finding: Most of the prescriptions (63.8%) went to older children aged 12-18 years, and most prescriptions (66.3%) went to males.

Study details: Medicaid claims data for Jan. 1, 2012, to Dec. 31, 2016, yielding 14,567 prescriptions of off-label medications for 2,518 children.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no disclosures.

Source: Klein T et al. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.10.002.

Onset of pediatric status epilepticus may have a circadian pattern

NEW ORLEANS – according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. The number of episodes is greatest between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. and smallest between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m.

“Our findings may inform the increase in preventive monitoring, such as video monitoring or seizure-tracking devices for patients,” said Justice Clark, MPH, a program coordinator at Boston Children’s Hospital. “They may also inform chronotherapeutic strategies.”

Research suggests that various types of seizures cluster at different times of the day. Data about the circadian distribution of status epilepticus, however, are limited.

Ms. Clark and colleagues conducted a prospective observational study at 25 hospitals in the United States and Canada from June 2011 to January 2018. Eligible participants were between ages 1 month and 21 years, had focal or generalized convulsive status epilepticus, and had failed to respond to one benzodiazepine and one nonbenzodiazepine antiseizure medication. For patients with more than one episode of refractory status epilepticus during the study, the researchers included only the first episode.

The investigators examined whether the temporal distribution of pediatric refractory status epilepticus onset followed a circadian pattern using a cosinor analysis with a 12-hour cycle. They used the midline-estimating statistic of rhythm (MESOR) technique to estimate the mean number of refractory status epilepticus episodes per hour if onset was evenly distributed. The amplitude in this analysis was the difference in number of episodes per hour between the MESOR and the peak or the MESOR and the trough.

Ms. Clark and her colleagues included 300 patients in their analysis, each of whom had one episode. Approximately 45% of participants were female. The population’s median age was 4.2 years, and the median duration of status epilepticus was 120 minutes.

The MESOR was 12.5 episodes per hour, and the amplitude was 2.4 episodes per hour, indicating that the distribution was not even over 24 hours. The peak number of onsets was between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., and the trough was between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m.

A secondary analysis examined the circadian distribution of time to treatment with rescue medications. The distribution of time to treatment with the first benzodiazepine did not differ significantly from a uniform distribution. The time to treatment with the first nonbenzodiazepine antiseizure medication, however, was not uniformly distributed. The longest time to treatment occurred between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m., and the shortest time was between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m. “Although fewer refractory status epilepticus episodes occurred at night, the time to antiseizure medication administration was the longest [during that period]. Thus, nighttime refractory status epilepticus episodes may be at higher risk for delayed treatment,” said Ms. Clark. A limitation of this analysis is that it was influenced by outliers, she added.

The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation and the Epilepsy Research Fund supported the study.

SOURCE: Clark J et al. AES 2018. Abstract 3.426.

NEW ORLEANS – according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. The number of episodes is greatest between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. and smallest between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m.

“Our findings may inform the increase in preventive monitoring, such as video monitoring or seizure-tracking devices for patients,” said Justice Clark, MPH, a program coordinator at Boston Children’s Hospital. “They may also inform chronotherapeutic strategies.”

Research suggests that various types of seizures cluster at different times of the day. Data about the circadian distribution of status epilepticus, however, are limited.

Ms. Clark and colleagues conducted a prospective observational study at 25 hospitals in the United States and Canada from June 2011 to January 2018. Eligible participants were between ages 1 month and 21 years, had focal or generalized convulsive status epilepticus, and had failed to respond to one benzodiazepine and one nonbenzodiazepine antiseizure medication. For patients with more than one episode of refractory status epilepticus during the study, the researchers included only the first episode.

The investigators examined whether the temporal distribution of pediatric refractory status epilepticus onset followed a circadian pattern using a cosinor analysis with a 12-hour cycle. They used the midline-estimating statistic of rhythm (MESOR) technique to estimate the mean number of refractory status epilepticus episodes per hour if onset was evenly distributed. The amplitude in this analysis was the difference in number of episodes per hour between the MESOR and the peak or the MESOR and the trough.

Ms. Clark and her colleagues included 300 patients in their analysis, each of whom had one episode. Approximately 45% of participants were female. The population’s median age was 4.2 years, and the median duration of status epilepticus was 120 minutes.

The MESOR was 12.5 episodes per hour, and the amplitude was 2.4 episodes per hour, indicating that the distribution was not even over 24 hours. The peak number of onsets was between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., and the trough was between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m.

A secondary analysis examined the circadian distribution of time to treatment with rescue medications. The distribution of time to treatment with the first benzodiazepine did not differ significantly from a uniform distribution. The time to treatment with the first nonbenzodiazepine antiseizure medication, however, was not uniformly distributed. The longest time to treatment occurred between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m., and the shortest time was between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m. “Although fewer refractory status epilepticus episodes occurred at night, the time to antiseizure medication administration was the longest [during that period]. Thus, nighttime refractory status epilepticus episodes may be at higher risk for delayed treatment,” said Ms. Clark. A limitation of this analysis is that it was influenced by outliers, she added.

The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation and the Epilepsy Research Fund supported the study.

SOURCE: Clark J et al. AES 2018. Abstract 3.426.

NEW ORLEANS – according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. The number of episodes is greatest between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. and smallest between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m.

“Our findings may inform the increase in preventive monitoring, such as video monitoring or seizure-tracking devices for patients,” said Justice Clark, MPH, a program coordinator at Boston Children’s Hospital. “They may also inform chronotherapeutic strategies.”

Research suggests that various types of seizures cluster at different times of the day. Data about the circadian distribution of status epilepticus, however, are limited.

Ms. Clark and colleagues conducted a prospective observational study at 25 hospitals in the United States and Canada from June 2011 to January 2018. Eligible participants were between ages 1 month and 21 years, had focal or generalized convulsive status epilepticus, and had failed to respond to one benzodiazepine and one nonbenzodiazepine antiseizure medication. For patients with more than one episode of refractory status epilepticus during the study, the researchers included only the first episode.

The investigators examined whether the temporal distribution of pediatric refractory status epilepticus onset followed a circadian pattern using a cosinor analysis with a 12-hour cycle. They used the midline-estimating statistic of rhythm (MESOR) technique to estimate the mean number of refractory status epilepticus episodes per hour if onset was evenly distributed. The amplitude in this analysis was the difference in number of episodes per hour between the MESOR and the peak or the MESOR and the trough.

Ms. Clark and her colleagues included 300 patients in their analysis, each of whom had one episode. Approximately 45% of participants were female. The population’s median age was 4.2 years, and the median duration of status epilepticus was 120 minutes.

The MESOR was 12.5 episodes per hour, and the amplitude was 2.4 episodes per hour, indicating that the distribution was not even over 24 hours. The peak number of onsets was between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., and the trough was between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m.

A secondary analysis examined the circadian distribution of time to treatment with rescue medications. The distribution of time to treatment with the first benzodiazepine did not differ significantly from a uniform distribution. The time to treatment with the first nonbenzodiazepine antiseizure medication, however, was not uniformly distributed. The longest time to treatment occurred between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m., and the shortest time was between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m. “Although fewer refractory status epilepticus episodes occurred at night, the time to antiseizure medication administration was the longest [during that period]. Thus, nighttime refractory status epilepticus episodes may be at higher risk for delayed treatment,” said Ms. Clark. A limitation of this analysis is that it was influenced by outliers, she added.

The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation and the Epilepsy Research Fund supported the study.

SOURCE: Clark J et al. AES 2018. Abstract 3.426.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: The onset of pediatric refractory status epilepticus is not distributed uniformly across the day.

Major finding: Episodes peaked between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m.

Study details: A prospective, observational study conducted at 25 hospitals that included 300 patients.

Disclosures: The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation and the Epilepsy Research Fund funded the study.

Source: Clark J et al. AES 2018. Abstract 3.426.

Think outside lower body for pelvic pain

Also today, treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure decreased amyloid levels, spending on medical marketing increased by more than $12 billion over that past two decades, and one expert has advice on how you can get your work published.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure decreased amyloid levels, spending on medical marketing increased by more than $12 billion over that past two decades, and one expert has advice on how you can get your work published.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure decreased amyloid levels, spending on medical marketing increased by more than $12 billion over that past two decades, and one expert has advice on how you can get your work published.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

RE-SPECT ESUS: Dabigatran matched aspirin for second stroke prevention

MONTREAL – For the second time in the past year, an anticoagulant failed to show superiority when it was compared with aspirin for preventing a second stroke in patients who had had an index embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS). But the most recent results gave a tantalizing suggestion that the anticoagulant approach might be effective for older patients, those at least 75 years old, possibly because these patients have the highest incidence of atrial fibrillation.

“The fact that we saw a treatment benefit in patients 75 and older [in a post hoc, subgroup analysis] means that development of atrial fibrillation (AF) is probably the most important factor,” Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Another clue that incident AF drove a treatment benefit hidden in the new trial’s overall neutral result was that a post hoc, landmark analysis showed that, while the rate of second strokes was identical during the first year of follow-up in patients on either aspirin or the anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) after an index ESUS, patients on dabigatran had significantly fewer second strokes during subsequent follow-up.

More follow-up time was needed to see a benefit from anticoagulation because “it takes time for AF to develop, and then once a patient has AF, it takes time for a stroke to occur,” explained Dr. Diener, professor of neurology at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Essen, Germany.

The RE-SPECT ESUS (Dabigatran Etexilate for Secondary Stroke Prevention in Patients With Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial randomized 5,390 patients at more than 500 sites in 41 countries, including the United States, within 6 months of an index ESUS who had no history of AF and no severe renal impairment. All enrollees had to have less than 6 minutes of AF episodes during at least 20 hours of cardiac monitoring, and they had to be free of flow-limiting stenoses (50% or more) in arteries supplying their stroke region. Patients received either 150 mg or 110 mg of dabigatran twice daily depending on their age and renal function or 100 mg of aspirin daily. About a quarter of patients randomized to dabigatran received the lower dosage. The enrolled patients averaged 66 years old, almost two-thirds were men, and they started treatment a median of 44 days after their index stroke.

During a median 19 months’ follow-up, the incidence of a second stroke of any type was 4.1%/year among the patients on dabigatran and 4.8%/year among those on aspirin, a difference that was not statistically significant. However, the post hoc landmark analysis showed a significant reduction in second strokes with dabigatran treatment after the first year. In addition, a post hoc subgroup analysis showed that, among patients aged at least 75 years old, treatment with dabigatran linked with a statistically significant 37% reduction in second strokes, compared with treatment with aspirin, Dr. Diener reported.

The primary safety endpoint was major bleeds, as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, which occurred in 1.7%/year of patients on dabigatran and 1.4%/year of those on aspirin, a difference that was not statistically significant. Patients on dabigatran had a significant excess of major bleeds combined with clinically significant nonmajor bleeds: 3.3%/year versus 2.3%/year among those on aspirin.

A little over 4 months before Dr. Diener’s report, a separate research group published primary results from the NAVIGATE ESUS (Rivaroxaban Versus Aspirin in Secondary Prevention of Stroke and Prevention of Systemic Embolism in Patients With Recent Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial, which compared the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto) with aspirin for prevention of a second stroke in 7,213 ESUS patients. The results showed no significant efficacy difference between rivaroxaban and aspirin (N Engl J Med. 2018 June 7;378[23]:2191-2201).

RE-SPECT ESUS was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets dabigatran (Pradaxa). Dr. Diener has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, as well as several other companies.

SOURCE: Diener H-C et al. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(2_suppl):27. Abstract 100.

MONTREAL – For the second time in the past year, an anticoagulant failed to show superiority when it was compared with aspirin for preventing a second stroke in patients who had had an index embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS). But the most recent results gave a tantalizing suggestion that the anticoagulant approach might be effective for older patients, those at least 75 years old, possibly because these patients have the highest incidence of atrial fibrillation.

“The fact that we saw a treatment benefit in patients 75 and older [in a post hoc, subgroup analysis] means that development of atrial fibrillation (AF) is probably the most important factor,” Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Another clue that incident AF drove a treatment benefit hidden in the new trial’s overall neutral result was that a post hoc, landmark analysis showed that, while the rate of second strokes was identical during the first year of follow-up in patients on either aspirin or the anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) after an index ESUS, patients on dabigatran had significantly fewer second strokes during subsequent follow-up.

More follow-up time was needed to see a benefit from anticoagulation because “it takes time for AF to develop, and then once a patient has AF, it takes time for a stroke to occur,” explained Dr. Diener, professor of neurology at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Essen, Germany.

The RE-SPECT ESUS (Dabigatran Etexilate for Secondary Stroke Prevention in Patients With Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial randomized 5,390 patients at more than 500 sites in 41 countries, including the United States, within 6 months of an index ESUS who had no history of AF and no severe renal impairment. All enrollees had to have less than 6 minutes of AF episodes during at least 20 hours of cardiac monitoring, and they had to be free of flow-limiting stenoses (50% or more) in arteries supplying their stroke region. Patients received either 150 mg or 110 mg of dabigatran twice daily depending on their age and renal function or 100 mg of aspirin daily. About a quarter of patients randomized to dabigatran received the lower dosage. The enrolled patients averaged 66 years old, almost two-thirds were men, and they started treatment a median of 44 days after their index stroke.

During a median 19 months’ follow-up, the incidence of a second stroke of any type was 4.1%/year among the patients on dabigatran and 4.8%/year among those on aspirin, a difference that was not statistically significant. However, the post hoc landmark analysis showed a significant reduction in second strokes with dabigatran treatment after the first year. In addition, a post hoc subgroup analysis showed that, among patients aged at least 75 years old, treatment with dabigatran linked with a statistically significant 37% reduction in second strokes, compared with treatment with aspirin, Dr. Diener reported.

The primary safety endpoint was major bleeds, as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, which occurred in 1.7%/year of patients on dabigatran and 1.4%/year of those on aspirin, a difference that was not statistically significant. Patients on dabigatran had a significant excess of major bleeds combined with clinically significant nonmajor bleeds: 3.3%/year versus 2.3%/year among those on aspirin.

A little over 4 months before Dr. Diener’s report, a separate research group published primary results from the NAVIGATE ESUS (Rivaroxaban Versus Aspirin in Secondary Prevention of Stroke and Prevention of Systemic Embolism in Patients With Recent Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial, which compared the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto) with aspirin for prevention of a second stroke in 7,213 ESUS patients. The results showed no significant efficacy difference between rivaroxaban and aspirin (N Engl J Med. 2018 June 7;378[23]:2191-2201).

RE-SPECT ESUS was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets dabigatran (Pradaxa). Dr. Diener has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, as well as several other companies.

SOURCE: Diener H-C et al. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(2_suppl):27. Abstract 100.

MONTREAL – For the second time in the past year, an anticoagulant failed to show superiority when it was compared with aspirin for preventing a second stroke in patients who had had an index embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS). But the most recent results gave a tantalizing suggestion that the anticoagulant approach might be effective for older patients, those at least 75 years old, possibly because these patients have the highest incidence of atrial fibrillation.

“The fact that we saw a treatment benefit in patients 75 and older [in a post hoc, subgroup analysis] means that development of atrial fibrillation (AF) is probably the most important factor,” Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Another clue that incident AF drove a treatment benefit hidden in the new trial’s overall neutral result was that a post hoc, landmark analysis showed that, while the rate of second strokes was identical during the first year of follow-up in patients on either aspirin or the anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) after an index ESUS, patients on dabigatran had significantly fewer second strokes during subsequent follow-up.

More follow-up time was needed to see a benefit from anticoagulation because “it takes time for AF to develop, and then once a patient has AF, it takes time for a stroke to occur,” explained Dr. Diener, professor of neurology at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Essen, Germany.

The RE-SPECT ESUS (Dabigatran Etexilate for Secondary Stroke Prevention in Patients With Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial randomized 5,390 patients at more than 500 sites in 41 countries, including the United States, within 6 months of an index ESUS who had no history of AF and no severe renal impairment. All enrollees had to have less than 6 minutes of AF episodes during at least 20 hours of cardiac monitoring, and they had to be free of flow-limiting stenoses (50% or more) in arteries supplying their stroke region. Patients received either 150 mg or 110 mg of dabigatran twice daily depending on their age and renal function or 100 mg of aspirin daily. About a quarter of patients randomized to dabigatran received the lower dosage. The enrolled patients averaged 66 years old, almost two-thirds were men, and they started treatment a median of 44 days after their index stroke.

During a median 19 months’ follow-up, the incidence of a second stroke of any type was 4.1%/year among the patients on dabigatran and 4.8%/year among those on aspirin, a difference that was not statistically significant. However, the post hoc landmark analysis showed a significant reduction in second strokes with dabigatran treatment after the first year. In addition, a post hoc subgroup analysis showed that, among patients aged at least 75 years old, treatment with dabigatran linked with a statistically significant 37% reduction in second strokes, compared with treatment with aspirin, Dr. Diener reported.

The primary safety endpoint was major bleeds, as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, which occurred in 1.7%/year of patients on dabigatran and 1.4%/year of those on aspirin, a difference that was not statistically significant. Patients on dabigatran had a significant excess of major bleeds combined with clinically significant nonmajor bleeds: 3.3%/year versus 2.3%/year among those on aspirin.

A little over 4 months before Dr. Diener’s report, a separate research group published primary results from the NAVIGATE ESUS (Rivaroxaban Versus Aspirin in Secondary Prevention of Stroke and Prevention of Systemic Embolism in Patients With Recent Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial, which compared the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto) with aspirin for prevention of a second stroke in 7,213 ESUS patients. The results showed no significant efficacy difference between rivaroxaban and aspirin (N Engl J Med. 2018 June 7;378[23]:2191-2201).

RE-SPECT ESUS was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets dabigatran (Pradaxa). Dr. Diener has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, as well as several other companies.

SOURCE: Diener H-C et al. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(2_suppl):27. Abstract 100.

REPORTING FROM THE WORLD STROKE CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A second stroke occurred at 4.1%/year with dabigatran and 4.8%/year with aspirin, not a statistically significant difference.

Study details: RE-SPECT ESUS, an international randomized trial with 5,390 ESUS patients.

Disclosures: RE-SPECT ESUS was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets dabigatran (Pradaxa). Dr. Diener has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, as well as several other companies.

Source: Diener H-C et al. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(2_suppl):27. Abstract 100.

Gout’s Golden Globe, resistance is fecal, eucalyptus eulogy

Eucalyptus eulogy

(“Taps” quietly plays in the background ... ) In some sad news, Quincy the diabetic koala has passed on to that great eucalyptus tree in the sky. The furry type 1 diabetic lived in San Diego, where he was recently fitted with a cutting-edge continuous glucose monitor (CGM). This allowed Quincy more time for his favorite activities (chewing and sleeping) and less time spent with pesky skin pricks.

Quincy died of pneumonia, and it is unclear whether his death was diabetes related. All we know is that he will be missed greatly. He was beloved by those with diabetes everywhere, animal or otherwise. Quincy’s successful CGM procedure also gives endocrinologists hope that the technology could eventually be used for similarly fragile humans, like babies. R.I.P., Quincy; we loved you. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to his favorite charity, the Drop Bear Awareness Association.

What’s Latin for ‘poop’?

The study of the human microbiota has become incredibly important in recent years, but there’s no getting away from the fact that it entails experimenting on poop. Remarkably, no one’s come up with a proper technical name for this unsavory activity. However, thanks to a collaboration between a gastroenterologist and a classics professor at the University of North Carolina, that deficiency is no more. You’ve met the in vivo and in vitro study. Now, please welcome the “in vimo” study!

Why in vimo? The term fecal or “in feco” might seem obvious. But the Latin root word never referred to poop, and if there’s one thing scientists can’t have, it’s improper Latin usage. The Romans, it turns out, had lots of words for poop. The root word of laetamen referred to fertility, richness, and happiness – a tempting prospect – but was mostly used to refer to farm animal dung. Merda mostly referred to smell or stench, and stercus shared the same root word as scatology, which refers to obscene literature. Fimus, which specifically refers to manure, was thus the most precise, and it was used by literary giants such as Livy, Virgil, and Tacitus. A clear winner, and the in vimo study flushed the rest of the competition away.

And just in case you think these researchers are no fun, the name they chose for the active enzymes collected from their in vimo samples? Poopernatants. Yes, even doctors enjoy a good poop joke.

The new Breakfast Club

Researchers at the University of Illinois and the University of Texas have collaborated to study something that most of us fear greatly: high school cliques. The researchers, who may or may not have peaked in high school, took a look at high school peer crowds and influences that form those tight-knit bonds that last all of 4 years.

The study found that most of the classic cliques – the jocks, the popular crowd, the brains, the stoners, the loners – are still alive and well in today’s American school system. However, at least one new group has emerged in the last decade: the “anime/manga fans.” Researchers noted that although schools have become much more diverse, racial and ethnic stereotypes are alive and well. Thank God we only have to do high school once.

Resistance is fecal

And now, just in case you were wondering how long it would take to put our newfound knowledge of “in vimo” to use, here comes a study that has “in vimo” written all over it (metaphorically speaking, of course).

Researchers in Sweden and Finland decided to take a look at antibiotic resistance genes in sewage, because “antibiotics consumed by humans and animals are released into the environment in urine and fecal material contained in treated wastewaters and sludge applied to land.” Then they compared the abundance of the mobile antibiotic resistance genes with the abundance of a human fecal pollution marker.

That marker – a virus that infects bacteria in human feces but is rare in other animals – was “highly correlated to the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in environmental samples,” they said in a separate written statement, which “indicates that fecal pollution can largely explain the increase in resistant bacteria often found in human-impacted environments.” The name of that marker, the virus found in feces, happens to be “crAssphage.” And yes, the A really is capitalized. Really. We are not making this up.

Gout wins a Golden Globe

Gout has a new poster girl: Great Britain’s Queen Anne. She’s been dead for more than 4 centuries, but a Hollywood version of this stout monarch is turning a famously royal affliction into the disease of the moment.

The credit goes to actress Olivia Colman, who just won a Golden Globe award for her brilliant performance in the earthy comedy “The Favourite.” Ms. Colman transforms the pain-wracked Queen Anne into a needy, manipulative, and loopy monarch who still manages to draw our sympathy.

Besides flummoxing American spell-checkers with its title, The Favourite glories in stretching the truth about the queen’s private life. But she really does seem to have had the “disease of kings,” which has long been linked to the rich, fatty diets enjoyed by blue bloods.

Now, there’s talk that high-protein, meat-friendly keto and paleo diets are boosting rates among the young. This theory got an airing last week in a New York Magazine article titled “Why Gout Is Making a Comeback.”

The truth may be more complicated. Over the last few years, researchers have cast doubt on the keto-leads-to-gout theory and suggested that fructose in sugar may be the real culprit. According to this hypothesis, gout afflicted British royals as they developed a communal sweet tooth during the early days of the sugar trade. Gout then spread to the general population as sugar became more accessible.

The gout debate will continue. As for Olivia Colman, she will soon grace smaller screens with her performance as Queen Elizabeth II in Netflix’s series “The Crown.”

QE II isn’t known for having suffered from any major diseases. But at her next checkup, we do think she should have that stiff upper lip looked at.

Eucalyptus eulogy

(“Taps” quietly plays in the background ... ) In some sad news, Quincy the diabetic koala has passed on to that great eucalyptus tree in the sky. The furry type 1 diabetic lived in San Diego, where he was recently fitted with a cutting-edge continuous glucose monitor (CGM). This allowed Quincy more time for his favorite activities (chewing and sleeping) and less time spent with pesky skin pricks.

Quincy died of pneumonia, and it is unclear whether his death was diabetes related. All we know is that he will be missed greatly. He was beloved by those with diabetes everywhere, animal or otherwise. Quincy’s successful CGM procedure also gives endocrinologists hope that the technology could eventually be used for similarly fragile humans, like babies. R.I.P., Quincy; we loved you. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to his favorite charity, the Drop Bear Awareness Association.

What’s Latin for ‘poop’?

The study of the human microbiota has become incredibly important in recent years, but there’s no getting away from the fact that it entails experimenting on poop. Remarkably, no one’s come up with a proper technical name for this unsavory activity. However, thanks to a collaboration between a gastroenterologist and a classics professor at the University of North Carolina, that deficiency is no more. You’ve met the in vivo and in vitro study. Now, please welcome the “in vimo” study!

Why in vimo? The term fecal or “in feco” might seem obvious. But the Latin root word never referred to poop, and if there’s one thing scientists can’t have, it’s improper Latin usage. The Romans, it turns out, had lots of words for poop. The root word of laetamen referred to fertility, richness, and happiness – a tempting prospect – but was mostly used to refer to farm animal dung. Merda mostly referred to smell or stench, and stercus shared the same root word as scatology, which refers to obscene literature. Fimus, which specifically refers to manure, was thus the most precise, and it was used by literary giants such as Livy, Virgil, and Tacitus. A clear winner, and the in vimo study flushed the rest of the competition away.

And just in case you think these researchers are no fun, the name they chose for the active enzymes collected from their in vimo samples? Poopernatants. Yes, even doctors enjoy a good poop joke.

The new Breakfast Club

Researchers at the University of Illinois and the University of Texas have collaborated to study something that most of us fear greatly: high school cliques. The researchers, who may or may not have peaked in high school, took a look at high school peer crowds and influences that form those tight-knit bonds that last all of 4 years.

The study found that most of the classic cliques – the jocks, the popular crowd, the brains, the stoners, the loners – are still alive and well in today’s American school system. However, at least one new group has emerged in the last decade: the “anime/manga fans.” Researchers noted that although schools have become much more diverse, racial and ethnic stereotypes are alive and well. Thank God we only have to do high school once.

Resistance is fecal

And now, just in case you were wondering how long it would take to put our newfound knowledge of “in vimo” to use, here comes a study that has “in vimo” written all over it (metaphorically speaking, of course).

Researchers in Sweden and Finland decided to take a look at antibiotic resistance genes in sewage, because “antibiotics consumed by humans and animals are released into the environment in urine and fecal material contained in treated wastewaters and sludge applied to land.” Then they compared the abundance of the mobile antibiotic resistance genes with the abundance of a human fecal pollution marker.

That marker – a virus that infects bacteria in human feces but is rare in other animals – was “highly correlated to the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in environmental samples,” they said in a separate written statement, which “indicates that fecal pollution can largely explain the increase in resistant bacteria often found in human-impacted environments.” The name of that marker, the virus found in feces, happens to be “crAssphage.” And yes, the A really is capitalized. Really. We are not making this up.

Gout wins a Golden Globe

Gout has a new poster girl: Great Britain’s Queen Anne. She’s been dead for more than 4 centuries, but a Hollywood version of this stout monarch is turning a famously royal affliction into the disease of the moment.

The credit goes to actress Olivia Colman, who just won a Golden Globe award for her brilliant performance in the earthy comedy “The Favourite.” Ms. Colman transforms the pain-wracked Queen Anne into a needy, manipulative, and loopy monarch who still manages to draw our sympathy.

Besides flummoxing American spell-checkers with its title, The Favourite glories in stretching the truth about the queen’s private life. But she really does seem to have had the “disease of kings,” which has long been linked to the rich, fatty diets enjoyed by blue bloods.

Now, there’s talk that high-protein, meat-friendly keto and paleo diets are boosting rates among the young. This theory got an airing last week in a New York Magazine article titled “Why Gout Is Making a Comeback.”

The truth may be more complicated. Over the last few years, researchers have cast doubt on the keto-leads-to-gout theory and suggested that fructose in sugar may be the real culprit. According to this hypothesis, gout afflicted British royals as they developed a communal sweet tooth during the early days of the sugar trade. Gout then spread to the general population as sugar became more accessible.

The gout debate will continue. As for Olivia Colman, she will soon grace smaller screens with her performance as Queen Elizabeth II in Netflix’s series “The Crown.”

QE II isn’t known for having suffered from any major diseases. But at her next checkup, we do think she should have that stiff upper lip looked at.

Eucalyptus eulogy

(“Taps” quietly plays in the background ... ) In some sad news, Quincy the diabetic koala has passed on to that great eucalyptus tree in the sky. The furry type 1 diabetic lived in San Diego, where he was recently fitted with a cutting-edge continuous glucose monitor (CGM). This allowed Quincy more time for his favorite activities (chewing and sleeping) and less time spent with pesky skin pricks.

Quincy died of pneumonia, and it is unclear whether his death was diabetes related. All we know is that he will be missed greatly. He was beloved by those with diabetes everywhere, animal or otherwise. Quincy’s successful CGM procedure also gives endocrinologists hope that the technology could eventually be used for similarly fragile humans, like babies. R.I.P., Quincy; we loved you. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to his favorite charity, the Drop Bear Awareness Association.

What’s Latin for ‘poop’?

The study of the human microbiota has become incredibly important in recent years, but there’s no getting away from the fact that it entails experimenting on poop. Remarkably, no one’s come up with a proper technical name for this unsavory activity. However, thanks to a collaboration between a gastroenterologist and a classics professor at the University of North Carolina, that deficiency is no more. You’ve met the in vivo and in vitro study. Now, please welcome the “in vimo” study!

Why in vimo? The term fecal or “in feco” might seem obvious. But the Latin root word never referred to poop, and if there’s one thing scientists can’t have, it’s improper Latin usage. The Romans, it turns out, had lots of words for poop. The root word of laetamen referred to fertility, richness, and happiness – a tempting prospect – but was mostly used to refer to farm animal dung. Merda mostly referred to smell or stench, and stercus shared the same root word as scatology, which refers to obscene literature. Fimus, which specifically refers to manure, was thus the most precise, and it was used by literary giants such as Livy, Virgil, and Tacitus. A clear winner, and the in vimo study flushed the rest of the competition away.

And just in case you think these researchers are no fun, the name they chose for the active enzymes collected from their in vimo samples? Poopernatants. Yes, even doctors enjoy a good poop joke.

The new Breakfast Club

Researchers at the University of Illinois and the University of Texas have collaborated to study something that most of us fear greatly: high school cliques. The researchers, who may or may not have peaked in high school, took a look at high school peer crowds and influences that form those tight-knit bonds that last all of 4 years.