User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

The Importance of Service Learning in Dermatology Residency: An Actionable Approach to Improve Resident Education and Skin Health Equity

Access to specialty care such as dermatology is a challenge for patients living in underserved communities.1 In 2019, there were 29.6 million individuals without health insurance in the United States—9.2% of the population—up from 28.6 million the prior year.2 Furthermore, Black and Hispanic patients, American Indian and Alaskan Natives, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders are more likely to be uninsured than their White counterparts.3 Community service activities such as free skin cancer screenings, partnerships with community practices, and teledermatology consultations through free clinics are instrumental in mitigating health care disparities and improving access to dermatologic care. In this article, we build on existing models from dermatology residency programs across the country to propose actionable methods to expand service-learning opportunities in dermatology residency training and increase health care equity in dermatology.

Why Service Learning?

Service learning is an educational approach that combines learning objectives with community service to provide a comprehensive scholastic experience and meet societal needs.4 In pilot studies of family medicine residents, service-learning initiatives enhanced the standard residency curriculum by promoting clinical practice resourcefulness.5 Dermatology Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements mandate that residents demonstrate an awareness of the larger context of health care, including social determinants of health.6 Likewise, dermatology residents must recognize the impact of socioeconomic status on health care utilization, treatment options, and patient adherence. With this understanding, residents can advocate for quality patient care and improve community-based health care systems.6

Service-learning projects can effectively meet the specific health needs of a community. In a service-learning environment, residents will understand a community-based health care approach and work with attending physician role models who exhibit a community service ethic.7 Residents also can gain interprofessional experience through collaborating with a team of social workers, community health workers, care coordinators, pharmacists, nurses, medical students, and attending physicians. Furthermore, residents can practice communicating effectively with patients and families across a range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. Interprofessional, team-based care and interpersonal skill acquisition are both Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for dermatology training.6 Through increased service-learning opportunities, dermatology trainees will learn to recognize and mitigate social determinants of health with a holistic, patient-centered treatment plan.

Free or low-cost medical clinics provide health care to more than 15 million Americans, many of whom identify with marginalized racial and ethnic groups.8 In a dermatology access study, a sample of clinics listed in the National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics database were contacted regarding the availability of dermatologic care; however, more than half of the sites were unresponsive or closed, and the remaining clinics offered limited access to dermatology services.9 The scarcity of free and low-cost dermatologic services likely contributes to adverse skin health outcomes for patients in underserved communities.10 By increasing service learning within dermatology residency training programs, access to dermatologic care will improve for underserved and uninsured populations.

Actionable Methods to Increase Service Learning in Dermatology Residency Training Programs

Utilize Programming Offered Through National Dermatology Associations and Societies

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has developed programming through which faculty, residents, and private practice dermatologists perform community service targeting underserved populations. SPOT me , a skin cancer screening program, is the AAD’s longest-standing public health program through which it provides complimentary screening forms, handouts, and advertisements to facilitate skin cancer screening. AccessDerm is the AAD’s philanthropic teledermatology program that delivers dermatologic care to underserved communities. Camp Discovery and the Shade Structure Grant Program are additional initiatives promoted by the AAD to support volunteer services for communities while learning about dermatology. Residents may apply for AAD grants to subsidize participation in the Native American Health Service Resident Rotation Program, the Skin Care for Developing Countries program, or an international grant.

The Women’s Dermatologic Society hosts 3 primary umbrella community outreach initiatives: Play Safe in the Sun, Coast-2-Coast, and the Transforming Interconnecting Project Program Women’s Shelter Initiative. From uplifting and educating individuals in women’s shelters about skin care, oral hygiene, self-care, nutrition, and social skills to providing complimentary skin cancer screenings, the Women’s Dermatologic Society provides easily accessible tool kits and syllabi to facilitate project composition and completion by its members.

Implement Residency Class Service-Learning Projects

Incoming dermatology residents are regularly encouraged to draft research proposals at the beginning of each academic year. Encouraging residency classes to work collectively on a dermatology service-learning project likely will increase resident camaraderie and project success while minimizing internal competition. In developing a service-learning proposal, residents should engage with community leaders and groups to best understand how to meet the skin health needs of underserved communities. The project should have clear objectives, benchmarks, and full support of the dermatology department. Short-term service-learning projects are completed when set goals are achieved, while sustainable projects continue with each new resident class.

Partner With Existing Community or Federally Funded Clinics

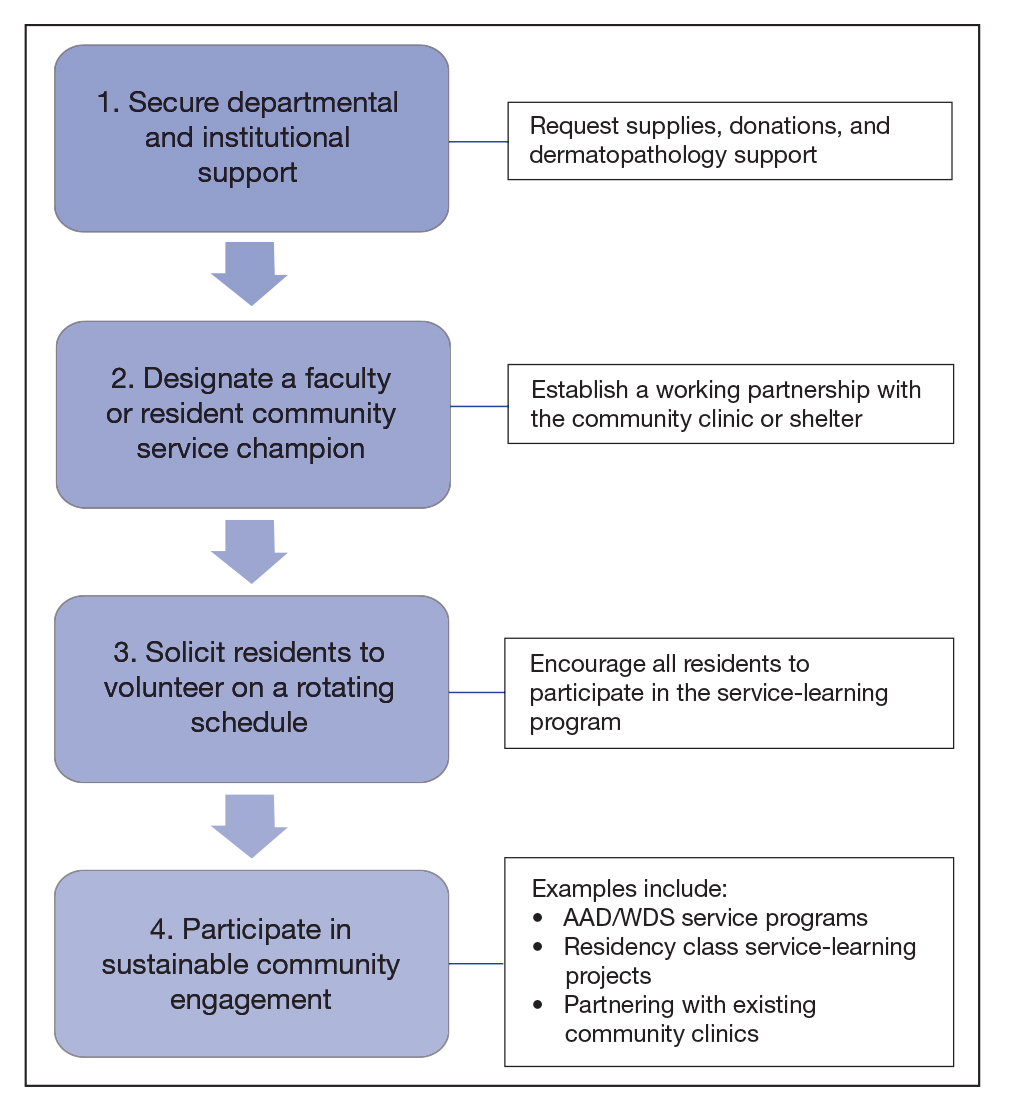

Establishing partnerships with free or federally funded health centers is a reliable way to increase service-learning opportunities in dermatology residency training. Personal malpractice carriers often include free clinic coverage, and most states offer limited liability or immunity for physicians who volunteer their professional services or subsidize malpractice insurance purchases.11 In light of the global coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, teledermatology options should be explored alongside in-person services. Although logistics may vary based on institutional preference, the following are our recommendations for building community partnerships for dermatology service learning (Figure):

• Secure departmental and institutional support. This includes requesting supplies, donations, and dermatopathology support

• Designate a resident or faculty community service champion to lead clinic correspondence and oversee operative logistics. This individual will establish a working partnership with the community clinic, assess the needs of the patient population, and manage the clinic schedule. The champion also will initiate and maintain open lines of communication with community providers for continuity of care. This partnership with community providers allows for shared resources and mutual learning

• Solicit residents to volunteer on a rotating schedule. Although some residents are fully committed to community service and health care justice, all residents need to participate in the service-learning program

• Participate in sustainable community engagement on a schedule that suits the needs of the community and takes into consideration resident and attending availability

Final Thoughts

Service learning in dermatology residency training is essential to improve access to equitable dermatologic care and train clinically competent dermatologists who have experience practicing in resource-limited settings. Service learning places cultural awareness and an understanding of socioeconomic determinants of health at the forefront.12 Some dermatology residency programs treat a high percentage of medically underserved patients; others have integrated service learning into dermatology rotations, and a few programs offer community engagement–focused residency tracks.13-16 Each dermatology program should evaluate its workforce, resources, and nearby underserved communities to strategically develop a program-specific service-learning program. Service-learning clinics often are the sole means by which patients from underserved communities receive dermatologic care.17 A commitment to service learning in dermatology residency programs will improve skin health equity and improve dermatology residency education.

- Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley J, et al. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1459-1468.

- Broaddus M, Aron-Dine A. Uninsured rate rose again in 2019, further eroding earlier progress. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities website. Published September 15, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/uninsured-rate-rose-again-in-2019-further-eroding-earlier-progress

- Artiga S, Orgera K, Damico A. Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/

- Martinez MG. H.R.2010 - 103rd Congress (1993-1994): National and Community Service Trust Act of 1993. AmeriCorps website. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/2010

- Gefter L, Merrell SB, Rosas LG, et al. Service-based learning for residents: a success for communities and medical education. Fam Med. 2015;47:803-806.

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. Updated July 1, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/080_Dermatology_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-161626-133

- 7. Blanco G, Vasquez R, Nezafati K, et al. How residency programs can foster practice for the underserved. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:158-159.

- Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:946.

- Madray V, Ginjupalli S, Hashmi O, et al. Access to dermatology services at free medical clinics: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:245-246.

- Shi L, Stevens GD. Vulnerability and unmet health care needs: the influence of multiple risk factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:148-154.

- Benrud L, Darrah J, Johnson A. Liability considerations for physician volunteers in the US. Virtual Mentor. 2010;12:207-212.

- Service-learning plays vital role in understanding social determinants of health. AAMC website. Published September 27, 2016. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/service-learning-plays-vital-role-understanding-social-determinants-health

- Sheu J, Gonzalez E, Gaeta JM, et al. Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program–Harvard Dermatology collaboration: a service-learning model providing care for an underserved population. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:789-790.

- Ojeda VD, Romero L, Ortiz A. A model for sustainable laser tattoo removal services for adult probationers. Int J Prison Health. 2019;15:308-315.

- Diversity & Community Track (Dermatology Diversity and Community Engagement residency position). Penn Medicine Dermatology website. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://dermatology.upenn.edu/residents/diversity-community-track/

- Duke Dermatology Diversity and Community Engagement residency position (1529080A2). Duke Dermatology website. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://dermatology.duke.edu/node/4742

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59.

Access to specialty care such as dermatology is a challenge for patients living in underserved communities.1 In 2019, there were 29.6 million individuals without health insurance in the United States—9.2% of the population—up from 28.6 million the prior year.2 Furthermore, Black and Hispanic patients, American Indian and Alaskan Natives, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders are more likely to be uninsured than their White counterparts.3 Community service activities such as free skin cancer screenings, partnerships with community practices, and teledermatology consultations through free clinics are instrumental in mitigating health care disparities and improving access to dermatologic care. In this article, we build on existing models from dermatology residency programs across the country to propose actionable methods to expand service-learning opportunities in dermatology residency training and increase health care equity in dermatology.

Why Service Learning?

Service learning is an educational approach that combines learning objectives with community service to provide a comprehensive scholastic experience and meet societal needs.4 In pilot studies of family medicine residents, service-learning initiatives enhanced the standard residency curriculum by promoting clinical practice resourcefulness.5 Dermatology Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements mandate that residents demonstrate an awareness of the larger context of health care, including social determinants of health.6 Likewise, dermatology residents must recognize the impact of socioeconomic status on health care utilization, treatment options, and patient adherence. With this understanding, residents can advocate for quality patient care and improve community-based health care systems.6

Service-learning projects can effectively meet the specific health needs of a community. In a service-learning environment, residents will understand a community-based health care approach and work with attending physician role models who exhibit a community service ethic.7 Residents also can gain interprofessional experience through collaborating with a team of social workers, community health workers, care coordinators, pharmacists, nurses, medical students, and attending physicians. Furthermore, residents can practice communicating effectively with patients and families across a range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. Interprofessional, team-based care and interpersonal skill acquisition are both Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for dermatology training.6 Through increased service-learning opportunities, dermatology trainees will learn to recognize and mitigate social determinants of health with a holistic, patient-centered treatment plan.

Free or low-cost medical clinics provide health care to more than 15 million Americans, many of whom identify with marginalized racial and ethnic groups.8 In a dermatology access study, a sample of clinics listed in the National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics database were contacted regarding the availability of dermatologic care; however, more than half of the sites were unresponsive or closed, and the remaining clinics offered limited access to dermatology services.9 The scarcity of free and low-cost dermatologic services likely contributes to adverse skin health outcomes for patients in underserved communities.10 By increasing service learning within dermatology residency training programs, access to dermatologic care will improve for underserved and uninsured populations.

Actionable Methods to Increase Service Learning in Dermatology Residency Training Programs

Utilize Programming Offered Through National Dermatology Associations and Societies

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has developed programming through which faculty, residents, and private practice dermatologists perform community service targeting underserved populations. SPOT me , a skin cancer screening program, is the AAD’s longest-standing public health program through which it provides complimentary screening forms, handouts, and advertisements to facilitate skin cancer screening. AccessDerm is the AAD’s philanthropic teledermatology program that delivers dermatologic care to underserved communities. Camp Discovery and the Shade Structure Grant Program are additional initiatives promoted by the AAD to support volunteer services for communities while learning about dermatology. Residents may apply for AAD grants to subsidize participation in the Native American Health Service Resident Rotation Program, the Skin Care for Developing Countries program, or an international grant.

The Women’s Dermatologic Society hosts 3 primary umbrella community outreach initiatives: Play Safe in the Sun, Coast-2-Coast, and the Transforming Interconnecting Project Program Women’s Shelter Initiative. From uplifting and educating individuals in women’s shelters about skin care, oral hygiene, self-care, nutrition, and social skills to providing complimentary skin cancer screenings, the Women’s Dermatologic Society provides easily accessible tool kits and syllabi to facilitate project composition and completion by its members.

Implement Residency Class Service-Learning Projects

Incoming dermatology residents are regularly encouraged to draft research proposals at the beginning of each academic year. Encouraging residency classes to work collectively on a dermatology service-learning project likely will increase resident camaraderie and project success while minimizing internal competition. In developing a service-learning proposal, residents should engage with community leaders and groups to best understand how to meet the skin health needs of underserved communities. The project should have clear objectives, benchmarks, and full support of the dermatology department. Short-term service-learning projects are completed when set goals are achieved, while sustainable projects continue with each new resident class.

Partner With Existing Community or Federally Funded Clinics

Establishing partnerships with free or federally funded health centers is a reliable way to increase service-learning opportunities in dermatology residency training. Personal malpractice carriers often include free clinic coverage, and most states offer limited liability or immunity for physicians who volunteer their professional services or subsidize malpractice insurance purchases.11 In light of the global coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, teledermatology options should be explored alongside in-person services. Although logistics may vary based on institutional preference, the following are our recommendations for building community partnerships for dermatology service learning (Figure):

• Secure departmental and institutional support. This includes requesting supplies, donations, and dermatopathology support

• Designate a resident or faculty community service champion to lead clinic correspondence and oversee operative logistics. This individual will establish a working partnership with the community clinic, assess the needs of the patient population, and manage the clinic schedule. The champion also will initiate and maintain open lines of communication with community providers for continuity of care. This partnership with community providers allows for shared resources and mutual learning

• Solicit residents to volunteer on a rotating schedule. Although some residents are fully committed to community service and health care justice, all residents need to participate in the service-learning program

• Participate in sustainable community engagement on a schedule that suits the needs of the community and takes into consideration resident and attending availability

Final Thoughts

Service learning in dermatology residency training is essential to improve access to equitable dermatologic care and train clinically competent dermatologists who have experience practicing in resource-limited settings. Service learning places cultural awareness and an understanding of socioeconomic determinants of health at the forefront.12 Some dermatology residency programs treat a high percentage of medically underserved patients; others have integrated service learning into dermatology rotations, and a few programs offer community engagement–focused residency tracks.13-16 Each dermatology program should evaluate its workforce, resources, and nearby underserved communities to strategically develop a program-specific service-learning program. Service-learning clinics often are the sole means by which patients from underserved communities receive dermatologic care.17 A commitment to service learning in dermatology residency programs will improve skin health equity and improve dermatology residency education.

Access to specialty care such as dermatology is a challenge for patients living in underserved communities.1 In 2019, there were 29.6 million individuals without health insurance in the United States—9.2% of the population—up from 28.6 million the prior year.2 Furthermore, Black and Hispanic patients, American Indian and Alaskan Natives, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders are more likely to be uninsured than their White counterparts.3 Community service activities such as free skin cancer screenings, partnerships with community practices, and teledermatology consultations through free clinics are instrumental in mitigating health care disparities and improving access to dermatologic care. In this article, we build on existing models from dermatology residency programs across the country to propose actionable methods to expand service-learning opportunities in dermatology residency training and increase health care equity in dermatology.

Why Service Learning?

Service learning is an educational approach that combines learning objectives with community service to provide a comprehensive scholastic experience and meet societal needs.4 In pilot studies of family medicine residents, service-learning initiatives enhanced the standard residency curriculum by promoting clinical practice resourcefulness.5 Dermatology Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements mandate that residents demonstrate an awareness of the larger context of health care, including social determinants of health.6 Likewise, dermatology residents must recognize the impact of socioeconomic status on health care utilization, treatment options, and patient adherence. With this understanding, residents can advocate for quality patient care and improve community-based health care systems.6

Service-learning projects can effectively meet the specific health needs of a community. In a service-learning environment, residents will understand a community-based health care approach and work with attending physician role models who exhibit a community service ethic.7 Residents also can gain interprofessional experience through collaborating with a team of social workers, community health workers, care coordinators, pharmacists, nurses, medical students, and attending physicians. Furthermore, residents can practice communicating effectively with patients and families across a range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. Interprofessional, team-based care and interpersonal skill acquisition are both Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for dermatology training.6 Through increased service-learning opportunities, dermatology trainees will learn to recognize and mitigate social determinants of health with a holistic, patient-centered treatment plan.

Free or low-cost medical clinics provide health care to more than 15 million Americans, many of whom identify with marginalized racial and ethnic groups.8 In a dermatology access study, a sample of clinics listed in the National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics database were contacted regarding the availability of dermatologic care; however, more than half of the sites were unresponsive or closed, and the remaining clinics offered limited access to dermatology services.9 The scarcity of free and low-cost dermatologic services likely contributes to adverse skin health outcomes for patients in underserved communities.10 By increasing service learning within dermatology residency training programs, access to dermatologic care will improve for underserved and uninsured populations.

Actionable Methods to Increase Service Learning in Dermatology Residency Training Programs

Utilize Programming Offered Through National Dermatology Associations and Societies

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has developed programming through which faculty, residents, and private practice dermatologists perform community service targeting underserved populations. SPOT me , a skin cancer screening program, is the AAD’s longest-standing public health program through which it provides complimentary screening forms, handouts, and advertisements to facilitate skin cancer screening. AccessDerm is the AAD’s philanthropic teledermatology program that delivers dermatologic care to underserved communities. Camp Discovery and the Shade Structure Grant Program are additional initiatives promoted by the AAD to support volunteer services for communities while learning about dermatology. Residents may apply for AAD grants to subsidize participation in the Native American Health Service Resident Rotation Program, the Skin Care for Developing Countries program, or an international grant.

The Women’s Dermatologic Society hosts 3 primary umbrella community outreach initiatives: Play Safe in the Sun, Coast-2-Coast, and the Transforming Interconnecting Project Program Women’s Shelter Initiative. From uplifting and educating individuals in women’s shelters about skin care, oral hygiene, self-care, nutrition, and social skills to providing complimentary skin cancer screenings, the Women’s Dermatologic Society provides easily accessible tool kits and syllabi to facilitate project composition and completion by its members.

Implement Residency Class Service-Learning Projects

Incoming dermatology residents are regularly encouraged to draft research proposals at the beginning of each academic year. Encouraging residency classes to work collectively on a dermatology service-learning project likely will increase resident camaraderie and project success while minimizing internal competition. In developing a service-learning proposal, residents should engage with community leaders and groups to best understand how to meet the skin health needs of underserved communities. The project should have clear objectives, benchmarks, and full support of the dermatology department. Short-term service-learning projects are completed when set goals are achieved, while sustainable projects continue with each new resident class.

Partner With Existing Community or Federally Funded Clinics

Establishing partnerships with free or federally funded health centers is a reliable way to increase service-learning opportunities in dermatology residency training. Personal malpractice carriers often include free clinic coverage, and most states offer limited liability or immunity for physicians who volunteer their professional services or subsidize malpractice insurance purchases.11 In light of the global coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, teledermatology options should be explored alongside in-person services. Although logistics may vary based on institutional preference, the following are our recommendations for building community partnerships for dermatology service learning (Figure):

• Secure departmental and institutional support. This includes requesting supplies, donations, and dermatopathology support

• Designate a resident or faculty community service champion to lead clinic correspondence and oversee operative logistics. This individual will establish a working partnership with the community clinic, assess the needs of the patient population, and manage the clinic schedule. The champion also will initiate and maintain open lines of communication with community providers for continuity of care. This partnership with community providers allows for shared resources and mutual learning

• Solicit residents to volunteer on a rotating schedule. Although some residents are fully committed to community service and health care justice, all residents need to participate in the service-learning program

• Participate in sustainable community engagement on a schedule that suits the needs of the community and takes into consideration resident and attending availability

Final Thoughts

Service learning in dermatology residency training is essential to improve access to equitable dermatologic care and train clinically competent dermatologists who have experience practicing in resource-limited settings. Service learning places cultural awareness and an understanding of socioeconomic determinants of health at the forefront.12 Some dermatology residency programs treat a high percentage of medically underserved patients; others have integrated service learning into dermatology rotations, and a few programs offer community engagement–focused residency tracks.13-16 Each dermatology program should evaluate its workforce, resources, and nearby underserved communities to strategically develop a program-specific service-learning program. Service-learning clinics often are the sole means by which patients from underserved communities receive dermatologic care.17 A commitment to service learning in dermatology residency programs will improve skin health equity and improve dermatology residency education.

- Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley J, et al. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1459-1468.

- Broaddus M, Aron-Dine A. Uninsured rate rose again in 2019, further eroding earlier progress. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities website. Published September 15, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/uninsured-rate-rose-again-in-2019-further-eroding-earlier-progress

- Artiga S, Orgera K, Damico A. Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/

- Martinez MG. H.R.2010 - 103rd Congress (1993-1994): National and Community Service Trust Act of 1993. AmeriCorps website. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/2010

- Gefter L, Merrell SB, Rosas LG, et al. Service-based learning for residents: a success for communities and medical education. Fam Med. 2015;47:803-806.

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. Updated July 1, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/080_Dermatology_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-161626-133

- 7. Blanco G, Vasquez R, Nezafati K, et al. How residency programs can foster practice for the underserved. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:158-159.

- Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:946.

- Madray V, Ginjupalli S, Hashmi O, et al. Access to dermatology services at free medical clinics: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:245-246.

- Shi L, Stevens GD. Vulnerability and unmet health care needs: the influence of multiple risk factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:148-154.

- Benrud L, Darrah J, Johnson A. Liability considerations for physician volunteers in the US. Virtual Mentor. 2010;12:207-212.

- Service-learning plays vital role in understanding social determinants of health. AAMC website. Published September 27, 2016. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/service-learning-plays-vital-role-understanding-social-determinants-health

- Sheu J, Gonzalez E, Gaeta JM, et al. Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program–Harvard Dermatology collaboration: a service-learning model providing care for an underserved population. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:789-790.

- Ojeda VD, Romero L, Ortiz A. A model for sustainable laser tattoo removal services for adult probationers. Int J Prison Health. 2019;15:308-315.

- Diversity & Community Track (Dermatology Diversity and Community Engagement residency position). Penn Medicine Dermatology website. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://dermatology.upenn.edu/residents/diversity-community-track/

- Duke Dermatology Diversity and Community Engagement residency position (1529080A2). Duke Dermatology website. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://dermatology.duke.edu/node/4742

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59.

- Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley J, et al. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1459-1468.

- Broaddus M, Aron-Dine A. Uninsured rate rose again in 2019, further eroding earlier progress. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities website. Published September 15, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/uninsured-rate-rose-again-in-2019-further-eroding-earlier-progress

- Artiga S, Orgera K, Damico A. Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/

- Martinez MG. H.R.2010 - 103rd Congress (1993-1994): National and Community Service Trust Act of 1993. AmeriCorps website. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/2010

- Gefter L, Merrell SB, Rosas LG, et al. Service-based learning for residents: a success for communities and medical education. Fam Med. 2015;47:803-806.

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. Updated July 1, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/080_Dermatology_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-161626-133

- 7. Blanco G, Vasquez R, Nezafati K, et al. How residency programs can foster practice for the underserved. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:158-159.

- Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:946.

- Madray V, Ginjupalli S, Hashmi O, et al. Access to dermatology services at free medical clinics: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:245-246.

- Shi L, Stevens GD. Vulnerability and unmet health care needs: the influence of multiple risk factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:148-154.

- Benrud L, Darrah J, Johnson A. Liability considerations for physician volunteers in the US. Virtual Mentor. 2010;12:207-212.

- Service-learning plays vital role in understanding social determinants of health. AAMC website. Published September 27, 2016. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/service-learning-plays-vital-role-understanding-social-determinants-health

- Sheu J, Gonzalez E, Gaeta JM, et al. Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program–Harvard Dermatology collaboration: a service-learning model providing care for an underserved population. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:789-790.

- Ojeda VD, Romero L, Ortiz A. A model for sustainable laser tattoo removal services for adult probationers. Int J Prison Health. 2019;15:308-315.

- Diversity & Community Track (Dermatology Diversity and Community Engagement residency position). Penn Medicine Dermatology website. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://dermatology.upenn.edu/residents/diversity-community-track/

- Duke Dermatology Diversity and Community Engagement residency position (1529080A2). Duke Dermatology website. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://dermatology.duke.edu/node/4742

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59.

Practice Points

- In 2019, nearly 30 million Americans did not have health insurance. Dermatologists in the United States should be cognizant of the challenges faced by underserved patients when accessing dermatologic care.

- Service learning is an educational approach that combines learning objectives with community service to provide a comprehensive learning experience, meet societal needs, and fulfill Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements.

- Actionable methods to increase service learning in dermatology residency training include volunteering in community service programs offered by national dermatology organizations, implementing service-learning projects, and partnering with free and federally funded community practices.

- Dermatology residents who participate in service learning will help increase access to equitable dermatologic care and experience practicing in settings with limited resources.

Onychomycosis: New Developments in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Antifungal Medication Safety

Onychomycosis is the most prevalent nail condition worldwide and has a significant impact on quality of life.1 There were 10 million physician visits for nail fungal infections in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2007 to 2016, which was more than double the number of all other nail diagnoses combined.2 Therefore, it is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the most current data on diagnosis and treatment of this extremely common nail disease as well as antifungal medication safety.

Onychomycosis Diagnosis

Diagnosis of onychomycosis using clinical examination alone has poor sensitivity and specificity and may lead to progression of disease and unwanted side effects from inappropriate therapy.3,4 Dermoscopy is a useful adjunct but diagnostically is still inferior compared to mycologic testing.5 Classical methods of diagnosis include potassium hydroxide staining with microscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology. Polymerase chain reaction is a newer technique with wide accessibility and excellent sensitivity and specificity.6 Although these techniques have excellent diagnostic accuracy both alone and in combination, the ideal test would have 100% sensitivity and specificity and would not require nail sampling. Artificial intelligence recently has been studied for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. In a prospective study of 90 patients with onychodystrophy who had photographs of the nails taken by nonphysicians, deep neural networks showed comparable sensitivity (70.2% vs 73.0%) and specificity (72.7% vs 49.7%) for diagnosis of onychomycosis vs clinical examination by dermatologists with a mean of 5.6 years of experience.7 Therefore, artificial intelligence may be considered as a supplement to clinical examination for dermatology residents and junior attending dermatologists and may be superior to clinical examination by nondermatologists, but mycologic confirmation is still necessary before initiating onychomycosis treatment.

Treatment of Onychomycosis

There are 3 topical therapies (ciclopirox lacquer 8%, efinaconazole solution 10%, and tavaborole solution 5%) and 3 oral therapies (terbinafine, itraconazole, and griseofulvin) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for onychomycosis therapy. Griseofulvin rarely is used due to the availability of more efficacious treatment options. Fluconazole is an off-label treatment that often is used in the United States.8

There are new data on the efficacy and safety of topical onychomycosis treatments in children. A phase 4 open‐label study of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks was performed in children aged 6 to 16 years with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (N=62).9,10 The medication was both well tolerated and safe in children. The only treatment-related adverse event was onychocryptosis, which was reported by 2 patients. At week 52, mycologic cure was 65% and complete cure was 40% (N=50). In a pharmacokinetic assessment performed in a subset of 17 patients aged 12 to 16 years, efinaconazole was measured at very low levels in plasma.9

A phase 4 open-label study also was performed to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of tavaborole for treatment of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis in children aged 6 years to under 17 years (N=55).11 Tavaborole solution 5% was applied once daily for 48 weeks; at week 52, mycologic and complete cures were 36.2% and 8.5%, respectively (N=47). Systemic exposure was low (Cmax=5.9 ng/mL [day 29]) in a subset of patients aged 12 years to under 17 years (N=37), and the medication demonstrated good safety and tolerability.11

Fosravuconazole was approved for treatment of onychomycosis in Japan in 2018. In a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of oral fosravuconazole 100 mg once daily (n=101) vs placebo (n=52) for 12 weeks in patients with onychomycosis (mean age, 58.4 years), the complete cure rate at 48 weeks was 59.4%.12 In a small trial of 37 elderly patients (mean age, 78.1 years), complete cure rates were 5.0% in patients with a nail plate thickness of 3 mm or greater and 58.8% in those with a thickness lessthan 3 mm, and there were no severe adverse events.13 In addition to excellent efficacy and proven safety in elderly adults, the main advantage of fosravuconazole is less-potent inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A compared to other triazole antifungals, with no contraindicated drugs listed.

Safety of Antifungals

There are new data describing the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients. In a nationwide cohort study conducted in Denmark (1,650,649 pregnancies [942 oral terbinafine exposed, 9420 unexposed matched cohorts]), there was no association between oral or topical terbinafine exposure during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth weight, low birth weight, or stillbirth.14 In a small study of 13 kidney transplant recipients taking oral tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or everolimus who were treated with oral terbinafine, there were no severe drug interactions and no clinical consequences in renal grafts.15

There also is new information on laboratory abnormalities in adults, children, and patients with comorbidities who are taking oral terbinafine. In a retrospective study of 944 adult patients without pre-existing hepatic or hematologic conditions who were prescribed 3 months of oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, abnormal monitoring liver function tests (LFTs) and complete blood cell counts (CBCs) were uncommon (2.4% and 2.8%, respectively) and mild and resolved after treatment completion. In addition, patients with laboratory abnormalities were an average of 14.8 years older and approximately 3-times more likely to be 65 years or older compared to the overall study population.16 There were similar findings in a retrospective study of 134 children 18 years or younger who were prescribed oral terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. Abnormal monitoring LFTs and CBCs were uncommon (1.7% and 4.4%, respectively) and mild, resolving after after treatment completion.17 Finally, in a study of 255 patients with a pre-existing liver or hematologic condition who were prescribed oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, worsening of LFT or CBC values were rare, and all resolved after treatment completion or medication discontinuation.18

Final Thoughts

Mycologic confirmation is still necessary before treatment despite encouraging data on use of artificial intelligence for diagnosis of onychomycosis. Efinaconazole solution 10% and tavaborole solution 5% have shown good safety, tolerability, and efficacy in children with onychomycosis. Recent data suggest the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and kidney transplant recipients, but these findings must be corroborated before its use in these populations. Fosravuconazole is a promising systemic treatment for onychomycosis with no drug-drug interactions reported to date. While baseline laboratory testing is recommended before prescribing terbinafine, interval laboratory monitoring may not be necessary in healthy adults.19 Prospective studies are necessary to corroborate these findings before formal recommendations can be made for prescribing terbinafine in the special populations discussed above, including children, and for interval laboratory monitoring.

- Stewart CR, Algu L, Kamran R, et al. Effect of onychomycosis and treatment on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review [published online June 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.143

- Lipner SR, Hancock JE, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1679337

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis--a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Confirmatory testing for onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:847.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Kim YJ, Han SS, Yang HJ, et al. Prospective, comparative evaluation of a deep neural network and dermoscopy in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234334.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Efinaconazole 10% topical solution for the treatment of onychomycosis in pediatric patients: open-label phase 4 study [published online July 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1004

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of efinaconazole 10% topical solution for onychomycosis treatment in pediatric patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:867-872.

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Watanabe S, Tsubouchi I, Okubo A. Efficacy and safety of fosravuconazole L-lysine ethanolate, a novel oral triazole antifungal agent, for the treatment of onychomycosis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase III study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1151-1159.

- Noguchi H, Matsumoto T, Kimura U, et al. Fosravuconazole to treat severe onychomycosis in the elderly [published online October 25, 2020]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15651

- Andersson NW, Thomsen SF, Andersen JT. Exposure to terbinafine in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birth weight, and stillbirth: a nationwide cohort study [published online October 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.034

- Moreno-Sabater A, Ouali N, Chasset F, et al. Severe onychomycosis management with oral terbinafine in a kidney transplantation setting: clinical follow-up by image analysis [published online November 27, 2020]. Mycoses. doi:10.1111/myc.13220

- Wang Y, Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:497-499.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections [published online January 27, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients with preexisting liver and hematologic diseases prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:220-221.

- Lamisil. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022071s003lbl.pdf

Onychomycosis is the most prevalent nail condition worldwide and has a significant impact on quality of life.1 There were 10 million physician visits for nail fungal infections in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2007 to 2016, which was more than double the number of all other nail diagnoses combined.2 Therefore, it is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the most current data on diagnosis and treatment of this extremely common nail disease as well as antifungal medication safety.

Onychomycosis Diagnosis

Diagnosis of onychomycosis using clinical examination alone has poor sensitivity and specificity and may lead to progression of disease and unwanted side effects from inappropriate therapy.3,4 Dermoscopy is a useful adjunct but diagnostically is still inferior compared to mycologic testing.5 Classical methods of diagnosis include potassium hydroxide staining with microscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology. Polymerase chain reaction is a newer technique with wide accessibility and excellent sensitivity and specificity.6 Although these techniques have excellent diagnostic accuracy both alone and in combination, the ideal test would have 100% sensitivity and specificity and would not require nail sampling. Artificial intelligence recently has been studied for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. In a prospective study of 90 patients with onychodystrophy who had photographs of the nails taken by nonphysicians, deep neural networks showed comparable sensitivity (70.2% vs 73.0%) and specificity (72.7% vs 49.7%) for diagnosis of onychomycosis vs clinical examination by dermatologists with a mean of 5.6 years of experience.7 Therefore, artificial intelligence may be considered as a supplement to clinical examination for dermatology residents and junior attending dermatologists and may be superior to clinical examination by nondermatologists, but mycologic confirmation is still necessary before initiating onychomycosis treatment.

Treatment of Onychomycosis

There are 3 topical therapies (ciclopirox lacquer 8%, efinaconazole solution 10%, and tavaborole solution 5%) and 3 oral therapies (terbinafine, itraconazole, and griseofulvin) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for onychomycosis therapy. Griseofulvin rarely is used due to the availability of more efficacious treatment options. Fluconazole is an off-label treatment that often is used in the United States.8

There are new data on the efficacy and safety of topical onychomycosis treatments in children. A phase 4 open‐label study of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks was performed in children aged 6 to 16 years with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (N=62).9,10 The medication was both well tolerated and safe in children. The only treatment-related adverse event was onychocryptosis, which was reported by 2 patients. At week 52, mycologic cure was 65% and complete cure was 40% (N=50). In a pharmacokinetic assessment performed in a subset of 17 patients aged 12 to 16 years, efinaconazole was measured at very low levels in plasma.9

A phase 4 open-label study also was performed to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of tavaborole for treatment of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis in children aged 6 years to under 17 years (N=55).11 Tavaborole solution 5% was applied once daily for 48 weeks; at week 52, mycologic and complete cures were 36.2% and 8.5%, respectively (N=47). Systemic exposure was low (Cmax=5.9 ng/mL [day 29]) in a subset of patients aged 12 years to under 17 years (N=37), and the medication demonstrated good safety and tolerability.11

Fosravuconazole was approved for treatment of onychomycosis in Japan in 2018. In a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of oral fosravuconazole 100 mg once daily (n=101) vs placebo (n=52) for 12 weeks in patients with onychomycosis (mean age, 58.4 years), the complete cure rate at 48 weeks was 59.4%.12 In a small trial of 37 elderly patients (mean age, 78.1 years), complete cure rates were 5.0% in patients with a nail plate thickness of 3 mm or greater and 58.8% in those with a thickness lessthan 3 mm, and there were no severe adverse events.13 In addition to excellent efficacy and proven safety in elderly adults, the main advantage of fosravuconazole is less-potent inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A compared to other triazole antifungals, with no contraindicated drugs listed.

Safety of Antifungals

There are new data describing the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients. In a nationwide cohort study conducted in Denmark (1,650,649 pregnancies [942 oral terbinafine exposed, 9420 unexposed matched cohorts]), there was no association between oral or topical terbinafine exposure during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth weight, low birth weight, or stillbirth.14 In a small study of 13 kidney transplant recipients taking oral tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or everolimus who were treated with oral terbinafine, there were no severe drug interactions and no clinical consequences in renal grafts.15

There also is new information on laboratory abnormalities in adults, children, and patients with comorbidities who are taking oral terbinafine. In a retrospective study of 944 adult patients without pre-existing hepatic or hematologic conditions who were prescribed 3 months of oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, abnormal monitoring liver function tests (LFTs) and complete blood cell counts (CBCs) were uncommon (2.4% and 2.8%, respectively) and mild and resolved after treatment completion. In addition, patients with laboratory abnormalities were an average of 14.8 years older and approximately 3-times more likely to be 65 years or older compared to the overall study population.16 There were similar findings in a retrospective study of 134 children 18 years or younger who were prescribed oral terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. Abnormal monitoring LFTs and CBCs were uncommon (1.7% and 4.4%, respectively) and mild, resolving after after treatment completion.17 Finally, in a study of 255 patients with a pre-existing liver or hematologic condition who were prescribed oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, worsening of LFT or CBC values were rare, and all resolved after treatment completion or medication discontinuation.18

Final Thoughts

Mycologic confirmation is still necessary before treatment despite encouraging data on use of artificial intelligence for diagnosis of onychomycosis. Efinaconazole solution 10% and tavaborole solution 5% have shown good safety, tolerability, and efficacy in children with onychomycosis. Recent data suggest the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and kidney transplant recipients, but these findings must be corroborated before its use in these populations. Fosravuconazole is a promising systemic treatment for onychomycosis with no drug-drug interactions reported to date. While baseline laboratory testing is recommended before prescribing terbinafine, interval laboratory monitoring may not be necessary in healthy adults.19 Prospective studies are necessary to corroborate these findings before formal recommendations can be made for prescribing terbinafine in the special populations discussed above, including children, and for interval laboratory monitoring.

Onychomycosis is the most prevalent nail condition worldwide and has a significant impact on quality of life.1 There were 10 million physician visits for nail fungal infections in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2007 to 2016, which was more than double the number of all other nail diagnoses combined.2 Therefore, it is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the most current data on diagnosis and treatment of this extremely common nail disease as well as antifungal medication safety.

Onychomycosis Diagnosis

Diagnosis of onychomycosis using clinical examination alone has poor sensitivity and specificity and may lead to progression of disease and unwanted side effects from inappropriate therapy.3,4 Dermoscopy is a useful adjunct but diagnostically is still inferior compared to mycologic testing.5 Classical methods of diagnosis include potassium hydroxide staining with microscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology. Polymerase chain reaction is a newer technique with wide accessibility and excellent sensitivity and specificity.6 Although these techniques have excellent diagnostic accuracy both alone and in combination, the ideal test would have 100% sensitivity and specificity and would not require nail sampling. Artificial intelligence recently has been studied for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. In a prospective study of 90 patients with onychodystrophy who had photographs of the nails taken by nonphysicians, deep neural networks showed comparable sensitivity (70.2% vs 73.0%) and specificity (72.7% vs 49.7%) for diagnosis of onychomycosis vs clinical examination by dermatologists with a mean of 5.6 years of experience.7 Therefore, artificial intelligence may be considered as a supplement to clinical examination for dermatology residents and junior attending dermatologists and may be superior to clinical examination by nondermatologists, but mycologic confirmation is still necessary before initiating onychomycosis treatment.

Treatment of Onychomycosis

There are 3 topical therapies (ciclopirox lacquer 8%, efinaconazole solution 10%, and tavaborole solution 5%) and 3 oral therapies (terbinafine, itraconazole, and griseofulvin) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for onychomycosis therapy. Griseofulvin rarely is used due to the availability of more efficacious treatment options. Fluconazole is an off-label treatment that often is used in the United States.8

There are new data on the efficacy and safety of topical onychomycosis treatments in children. A phase 4 open‐label study of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks was performed in children aged 6 to 16 years with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (N=62).9,10 The medication was both well tolerated and safe in children. The only treatment-related adverse event was onychocryptosis, which was reported by 2 patients. At week 52, mycologic cure was 65% and complete cure was 40% (N=50). In a pharmacokinetic assessment performed in a subset of 17 patients aged 12 to 16 years, efinaconazole was measured at very low levels in plasma.9

A phase 4 open-label study also was performed to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of tavaborole for treatment of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis in children aged 6 years to under 17 years (N=55).11 Tavaborole solution 5% was applied once daily for 48 weeks; at week 52, mycologic and complete cures were 36.2% and 8.5%, respectively (N=47). Systemic exposure was low (Cmax=5.9 ng/mL [day 29]) in a subset of patients aged 12 years to under 17 years (N=37), and the medication demonstrated good safety and tolerability.11

Fosravuconazole was approved for treatment of onychomycosis in Japan in 2018. In a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of oral fosravuconazole 100 mg once daily (n=101) vs placebo (n=52) for 12 weeks in patients with onychomycosis (mean age, 58.4 years), the complete cure rate at 48 weeks was 59.4%.12 In a small trial of 37 elderly patients (mean age, 78.1 years), complete cure rates were 5.0% in patients with a nail plate thickness of 3 mm or greater and 58.8% in those with a thickness lessthan 3 mm, and there were no severe adverse events.13 In addition to excellent efficacy and proven safety in elderly adults, the main advantage of fosravuconazole is less-potent inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A compared to other triazole antifungals, with no contraindicated drugs listed.

Safety of Antifungals

There are new data describing the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients. In a nationwide cohort study conducted in Denmark (1,650,649 pregnancies [942 oral terbinafine exposed, 9420 unexposed matched cohorts]), there was no association between oral or topical terbinafine exposure during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth weight, low birth weight, or stillbirth.14 In a small study of 13 kidney transplant recipients taking oral tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or everolimus who were treated with oral terbinafine, there were no severe drug interactions and no clinical consequences in renal grafts.15

There also is new information on laboratory abnormalities in adults, children, and patients with comorbidities who are taking oral terbinafine. In a retrospective study of 944 adult patients without pre-existing hepatic or hematologic conditions who were prescribed 3 months of oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, abnormal monitoring liver function tests (LFTs) and complete blood cell counts (CBCs) were uncommon (2.4% and 2.8%, respectively) and mild and resolved after treatment completion. In addition, patients with laboratory abnormalities were an average of 14.8 years older and approximately 3-times more likely to be 65 years or older compared to the overall study population.16 There were similar findings in a retrospective study of 134 children 18 years or younger who were prescribed oral terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. Abnormal monitoring LFTs and CBCs were uncommon (1.7% and 4.4%, respectively) and mild, resolving after after treatment completion.17 Finally, in a study of 255 patients with a pre-existing liver or hematologic condition who were prescribed oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, worsening of LFT or CBC values were rare, and all resolved after treatment completion or medication discontinuation.18

Final Thoughts

Mycologic confirmation is still necessary before treatment despite encouraging data on use of artificial intelligence for diagnosis of onychomycosis. Efinaconazole solution 10% and tavaborole solution 5% have shown good safety, tolerability, and efficacy in children with onychomycosis. Recent data suggest the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and kidney transplant recipients, but these findings must be corroborated before its use in these populations. Fosravuconazole is a promising systemic treatment for onychomycosis with no drug-drug interactions reported to date. While baseline laboratory testing is recommended before prescribing terbinafine, interval laboratory monitoring may not be necessary in healthy adults.19 Prospective studies are necessary to corroborate these findings before formal recommendations can be made for prescribing terbinafine in the special populations discussed above, including children, and for interval laboratory monitoring.

- Stewart CR, Algu L, Kamran R, et al. Effect of onychomycosis and treatment on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review [published online June 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.143

- Lipner SR, Hancock JE, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1679337

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis--a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Confirmatory testing for onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:847.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Kim YJ, Han SS, Yang HJ, et al. Prospective, comparative evaluation of a deep neural network and dermoscopy in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234334.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Efinaconazole 10% topical solution for the treatment of onychomycosis in pediatric patients: open-label phase 4 study [published online July 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1004

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of efinaconazole 10% topical solution for onychomycosis treatment in pediatric patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:867-872.

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Watanabe S, Tsubouchi I, Okubo A. Efficacy and safety of fosravuconazole L-lysine ethanolate, a novel oral triazole antifungal agent, for the treatment of onychomycosis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase III study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1151-1159.

- Noguchi H, Matsumoto T, Kimura U, et al. Fosravuconazole to treat severe onychomycosis in the elderly [published online October 25, 2020]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15651

- Andersson NW, Thomsen SF, Andersen JT. Exposure to terbinafine in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birth weight, and stillbirth: a nationwide cohort study [published online October 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.034

- Moreno-Sabater A, Ouali N, Chasset F, et al. Severe onychomycosis management with oral terbinafine in a kidney transplantation setting: clinical follow-up by image analysis [published online November 27, 2020]. Mycoses. doi:10.1111/myc.13220

- Wang Y, Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:497-499.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections [published online January 27, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients with preexisting liver and hematologic diseases prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:220-221.

- Lamisil. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022071s003lbl.pdf

- Stewart CR, Algu L, Kamran R, et al. Effect of onychomycosis and treatment on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review [published online June 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.143

- Lipner SR, Hancock JE, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1679337

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis--a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Confirmatory testing for onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:847.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Kim YJ, Han SS, Yang HJ, et al. Prospective, comparative evaluation of a deep neural network and dermoscopy in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234334.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Efinaconazole 10% topical solution for the treatment of onychomycosis in pediatric patients: open-label phase 4 study [published online July 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1004

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of efinaconazole 10% topical solution for onychomycosis treatment in pediatric patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:867-872.

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Watanabe S, Tsubouchi I, Okubo A. Efficacy and safety of fosravuconazole L-lysine ethanolate, a novel oral triazole antifungal agent, for the treatment of onychomycosis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase III study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1151-1159.

- Noguchi H, Matsumoto T, Kimura U, et al. Fosravuconazole to treat severe onychomycosis in the elderly [published online October 25, 2020]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15651

- Andersson NW, Thomsen SF, Andersen JT. Exposure to terbinafine in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birth weight, and stillbirth: a nationwide cohort study [published online October 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.034

- Moreno-Sabater A, Ouali N, Chasset F, et al. Severe onychomycosis management with oral terbinafine in a kidney transplantation setting: clinical follow-up by image analysis [published online November 27, 2020]. Mycoses. doi:10.1111/myc.13220

- Wang Y, Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:497-499.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections [published online January 27, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients with preexisting liver and hematologic diseases prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:220-221.

- Lamisil. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022071s003lbl.pdf

Hyperkeratotic Nummular Plaques on the Upper Trunk

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

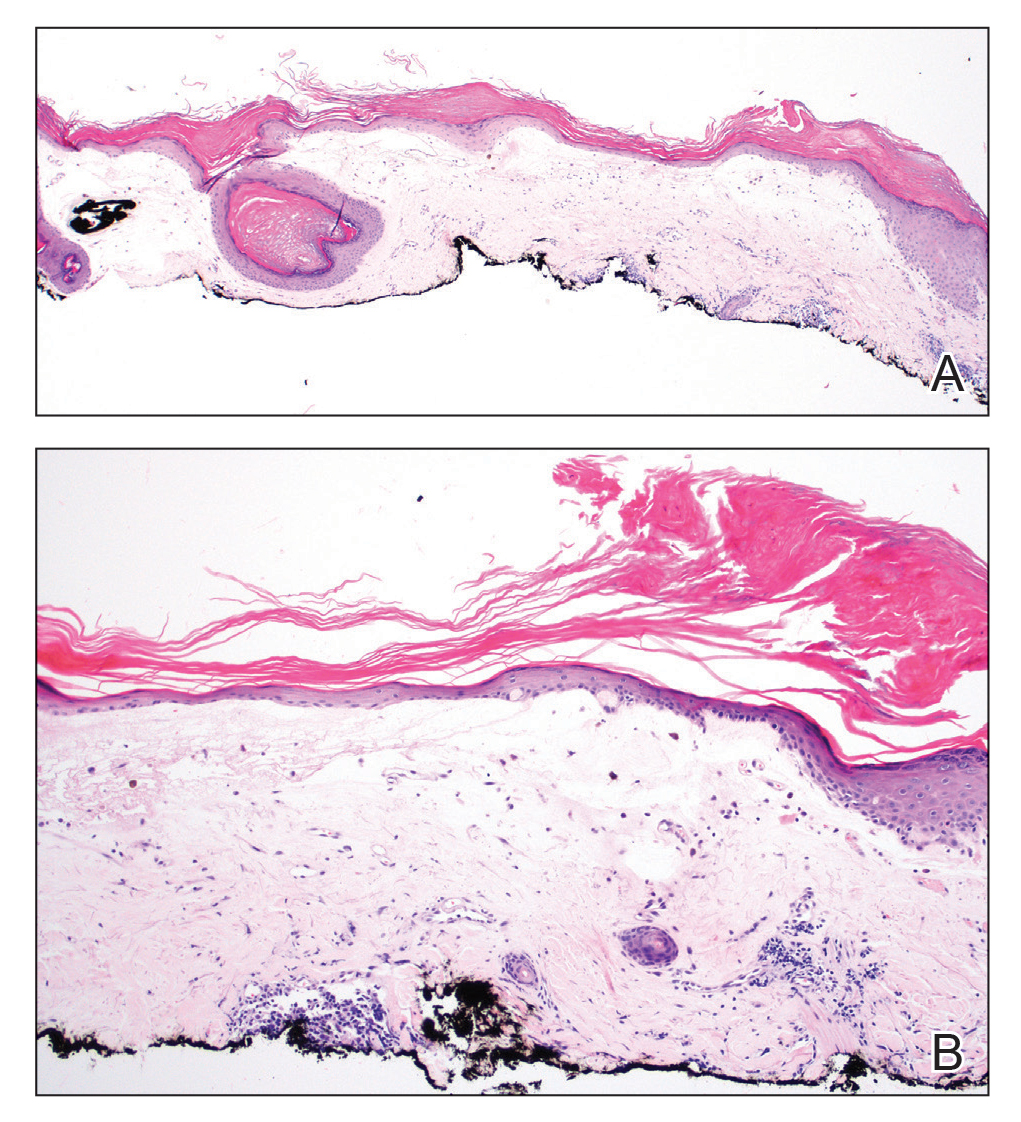

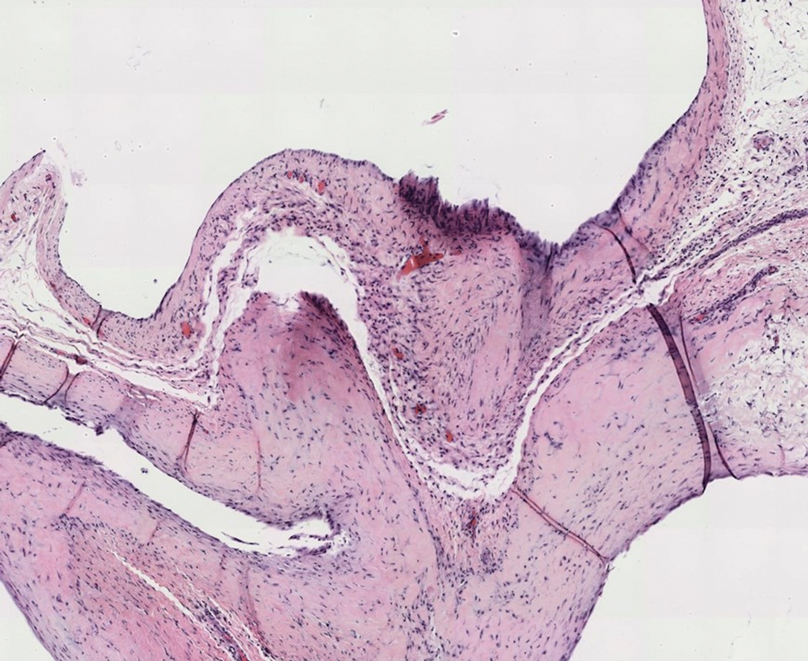

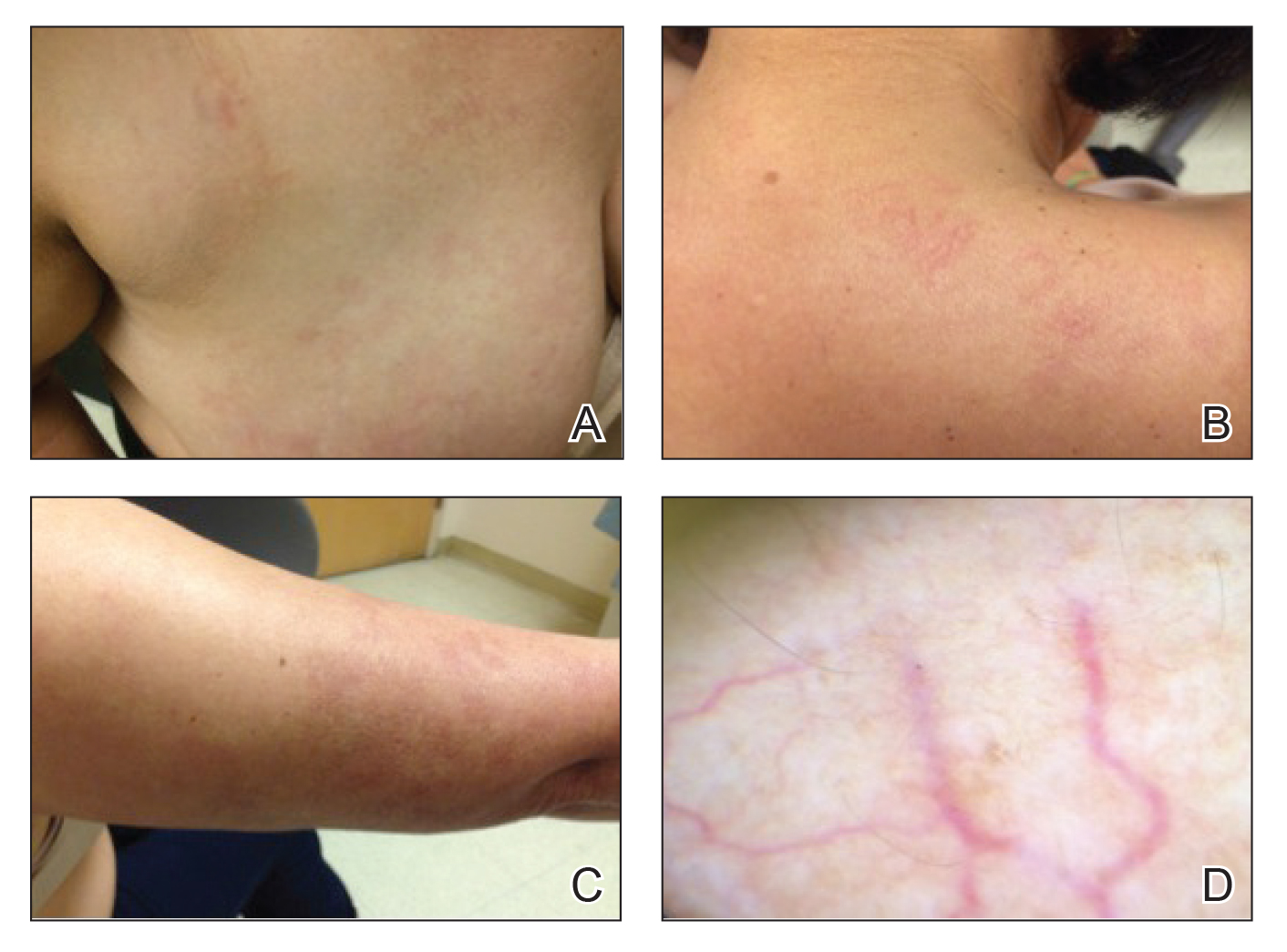

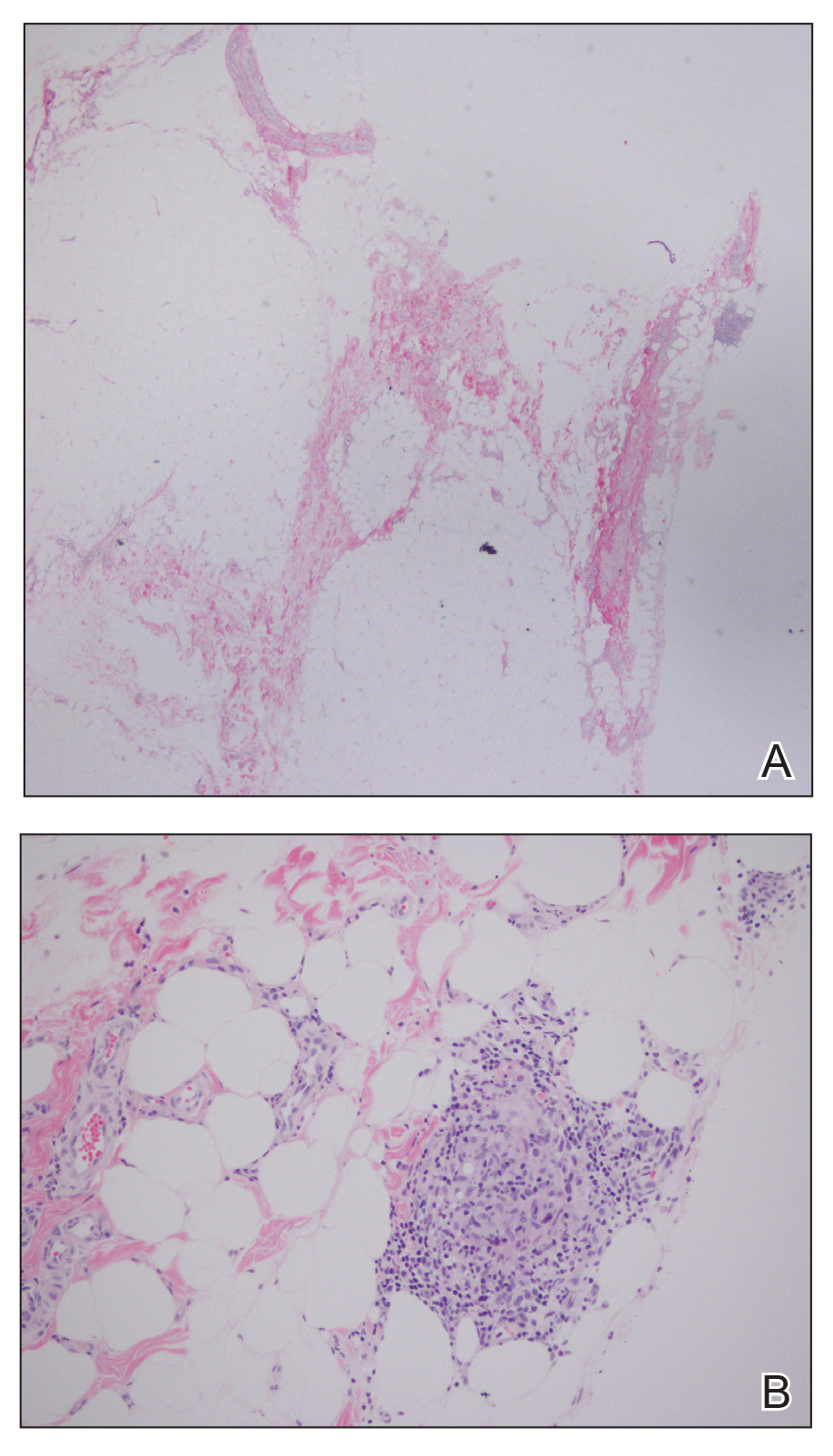

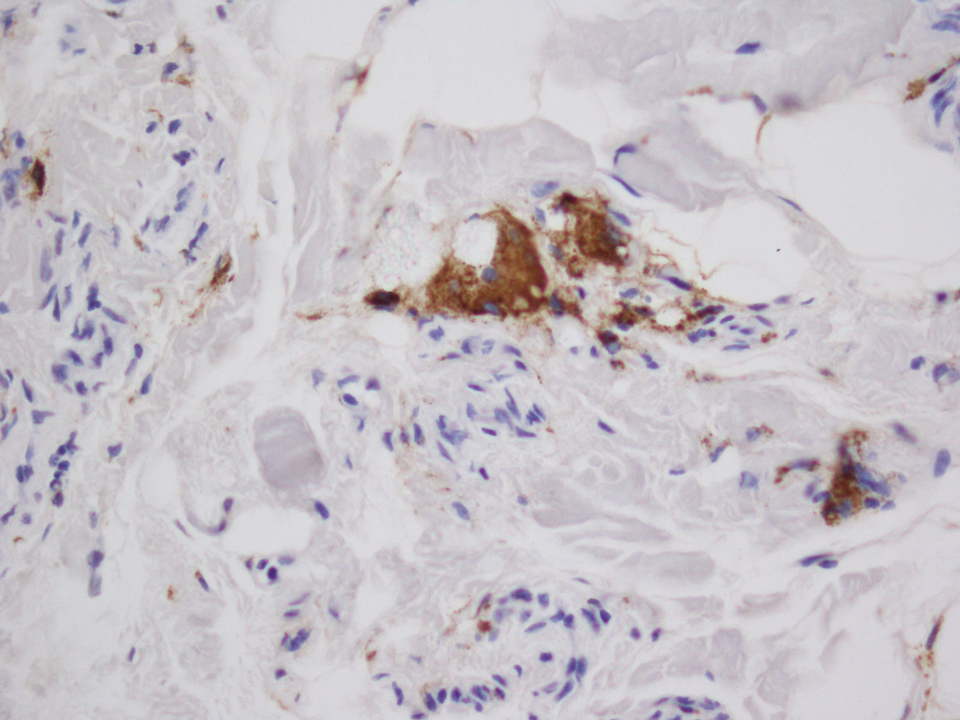

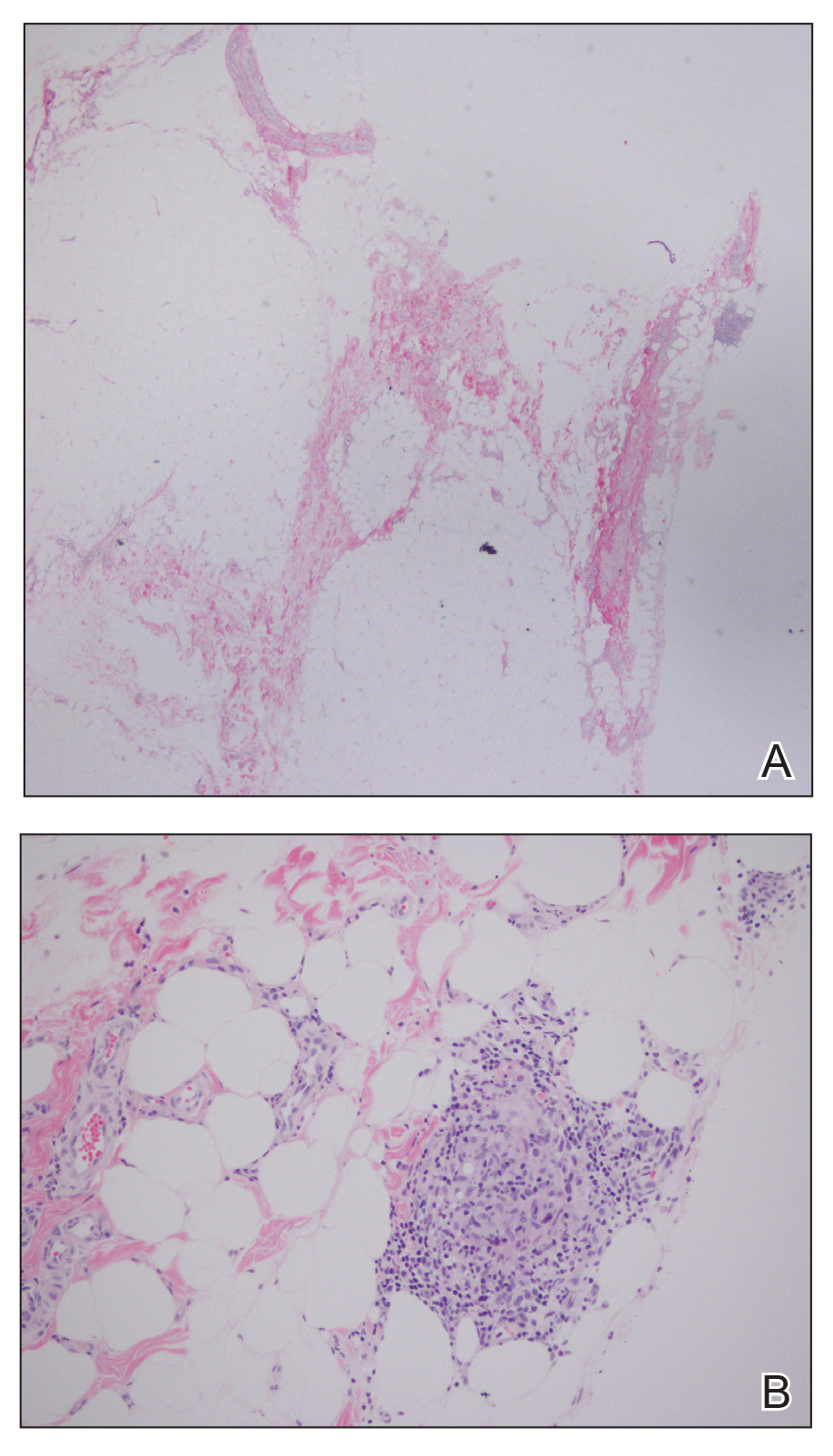

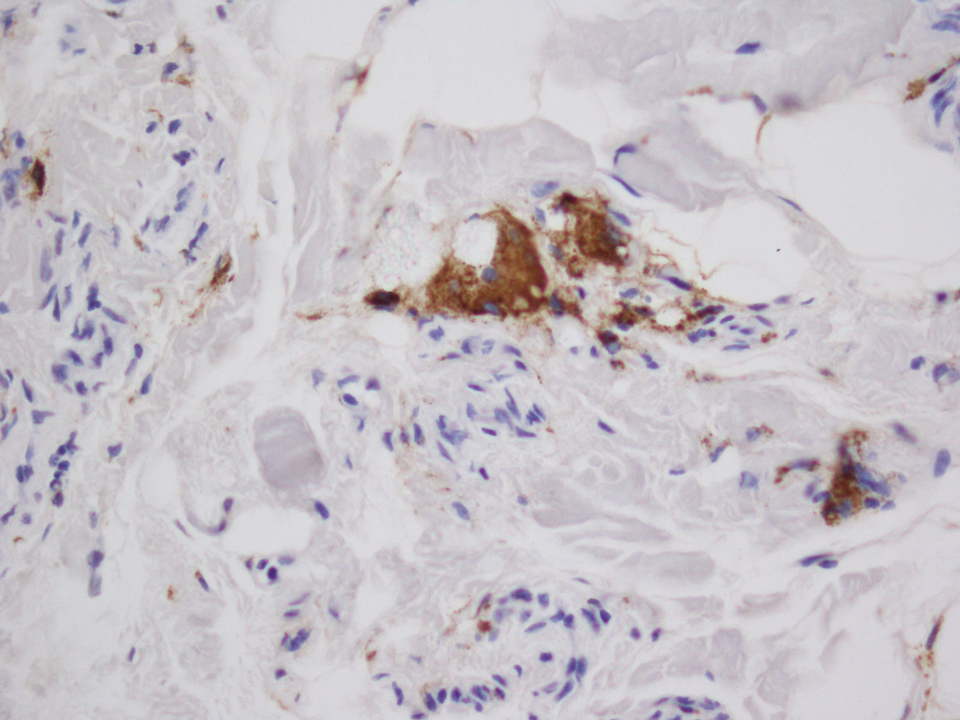

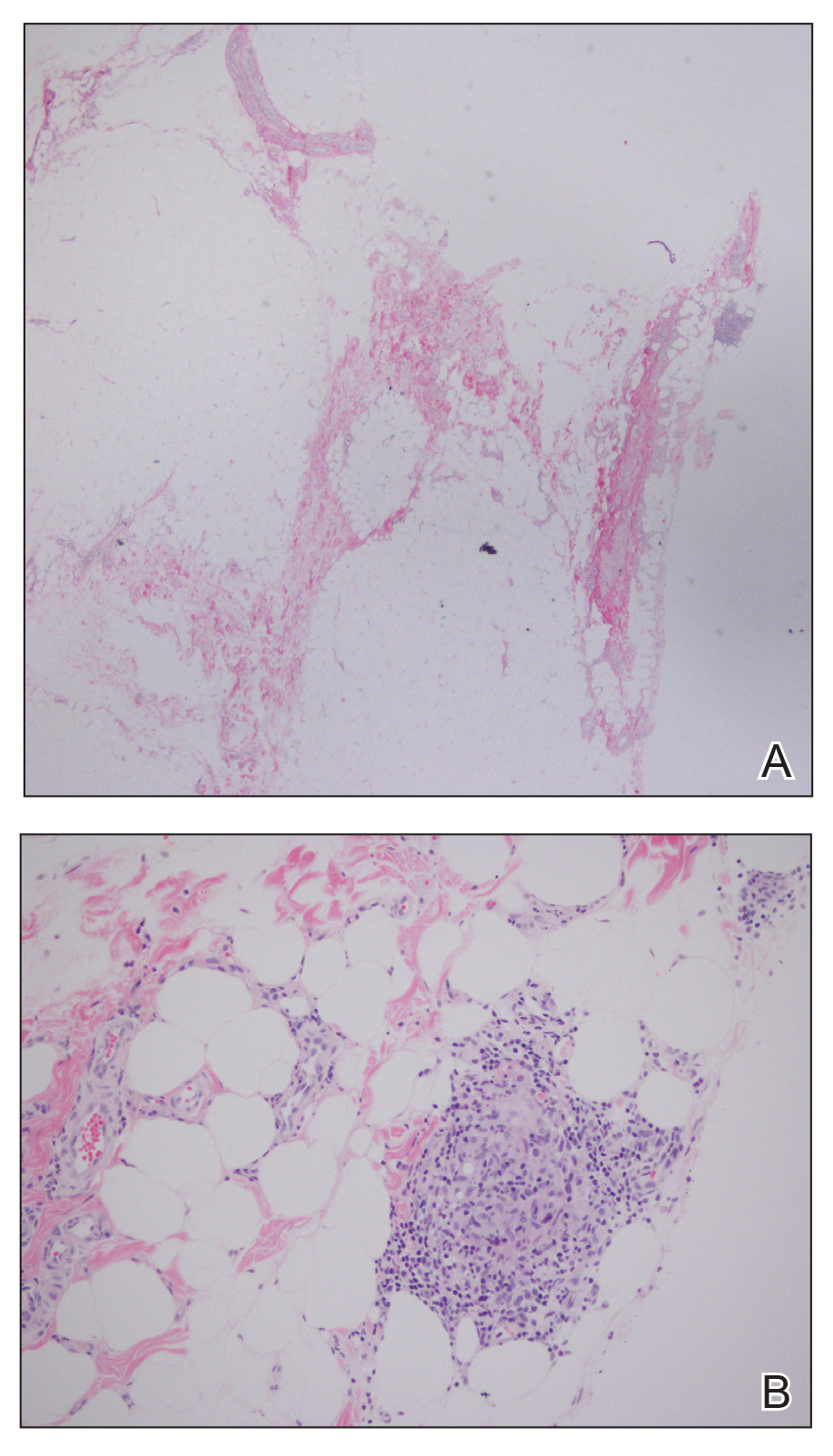

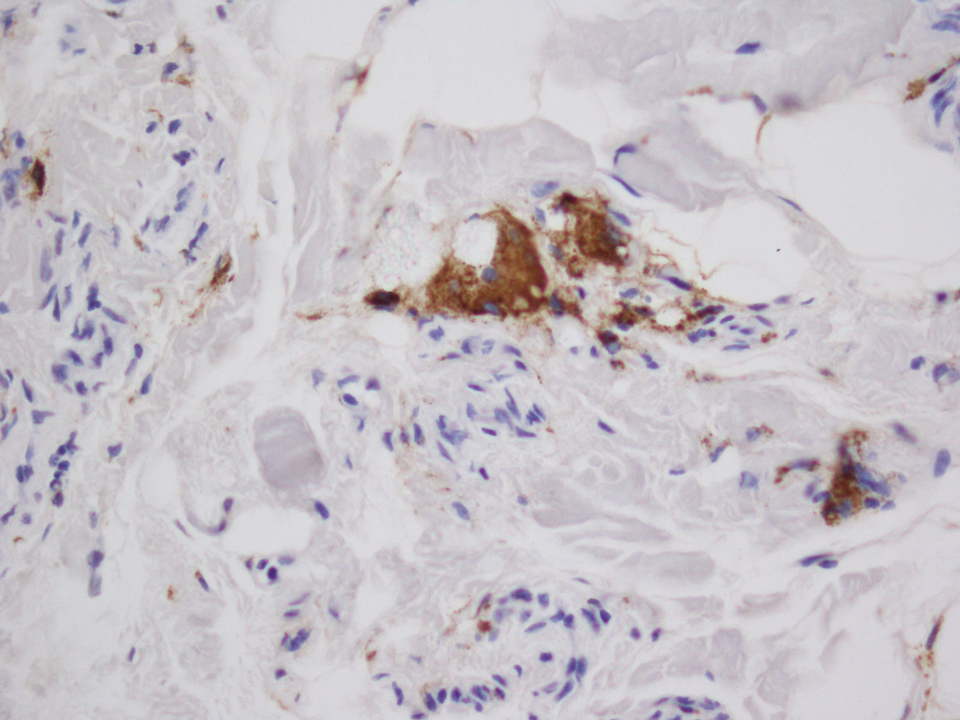

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

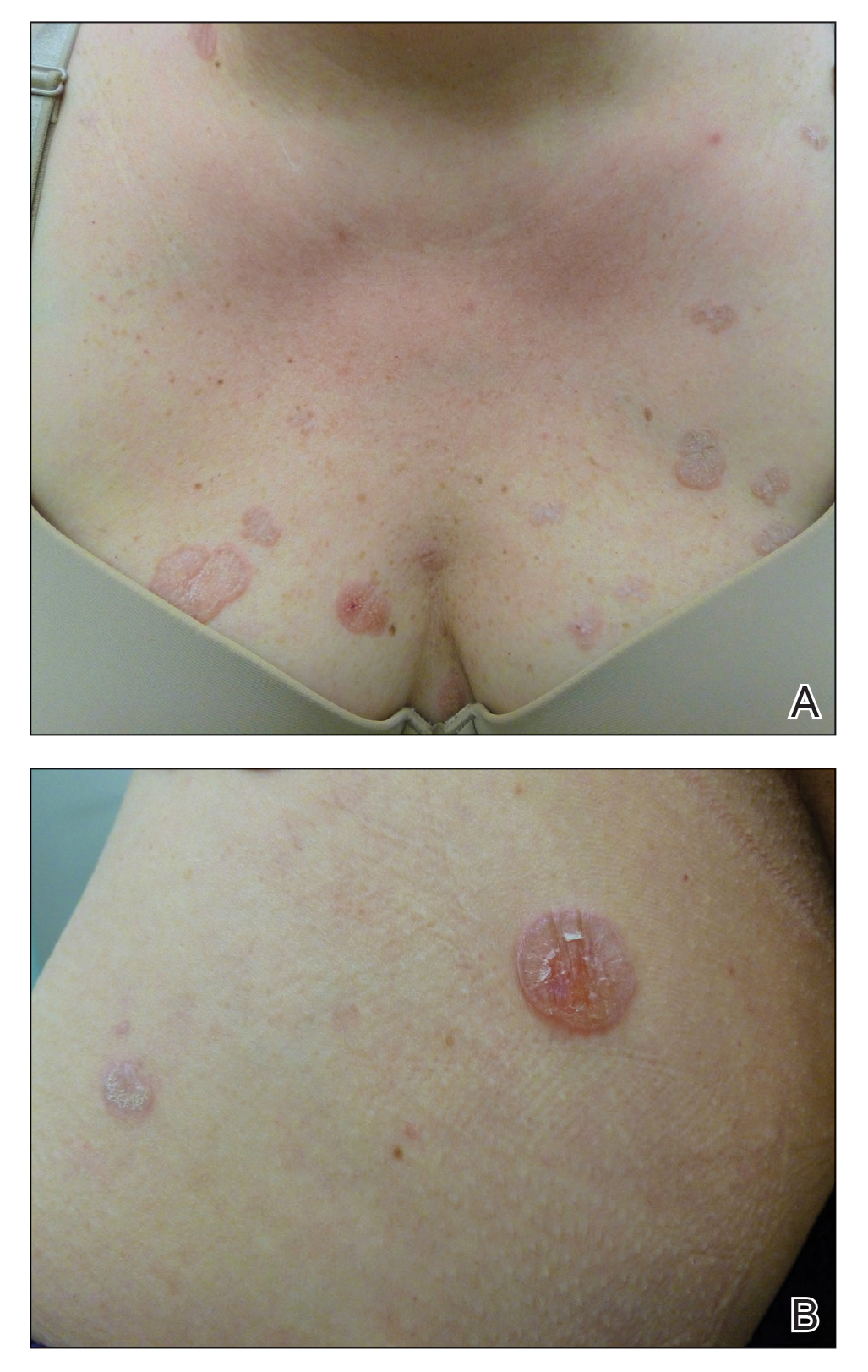

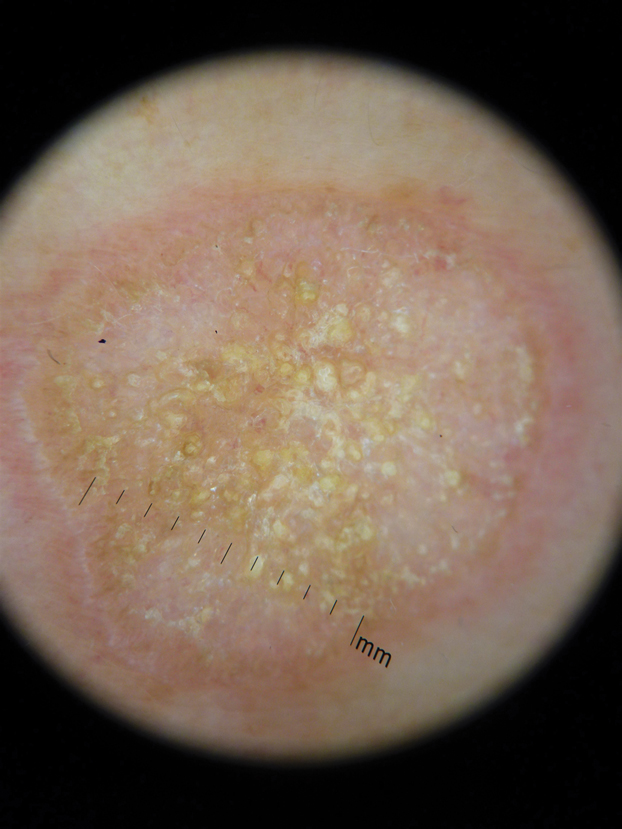

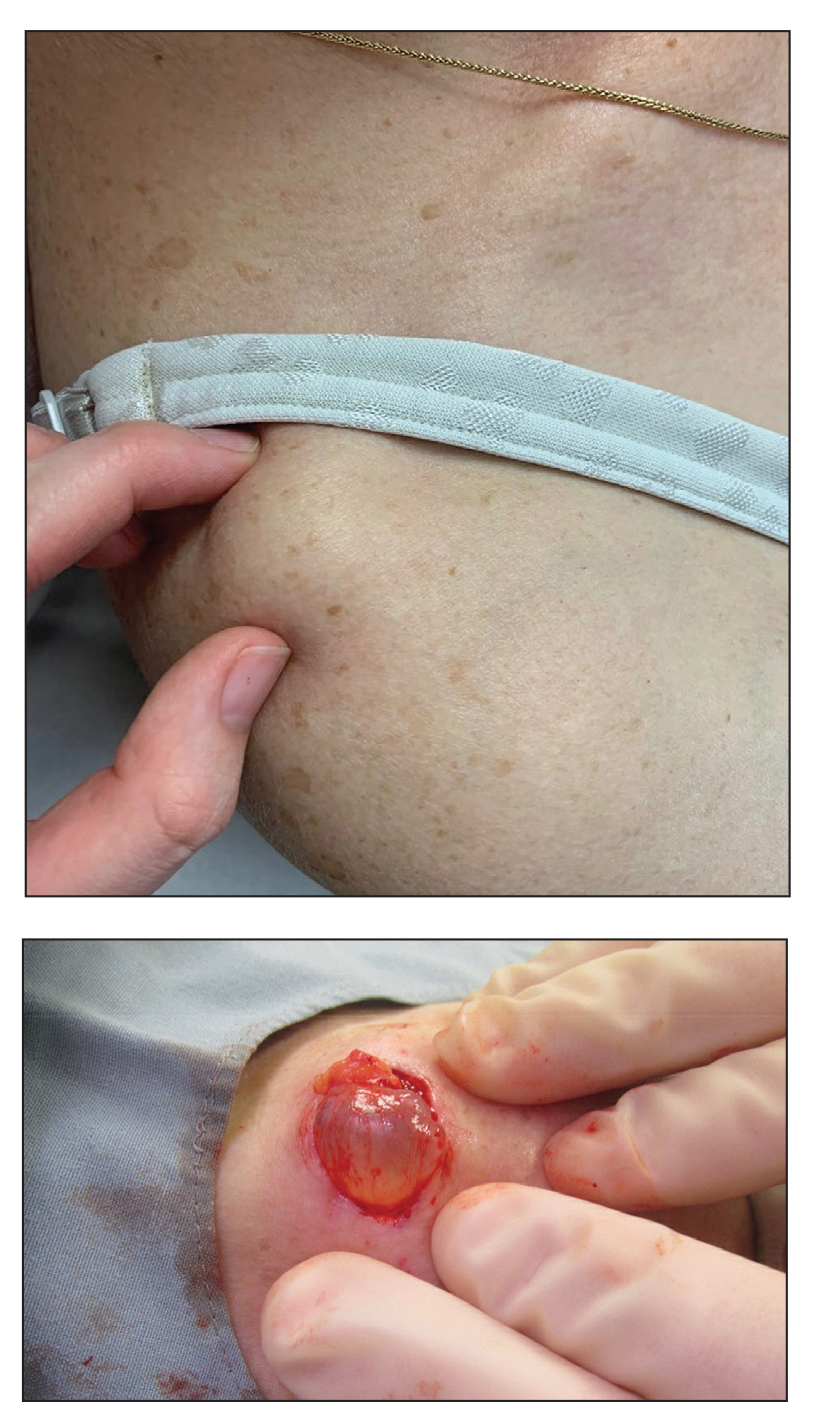

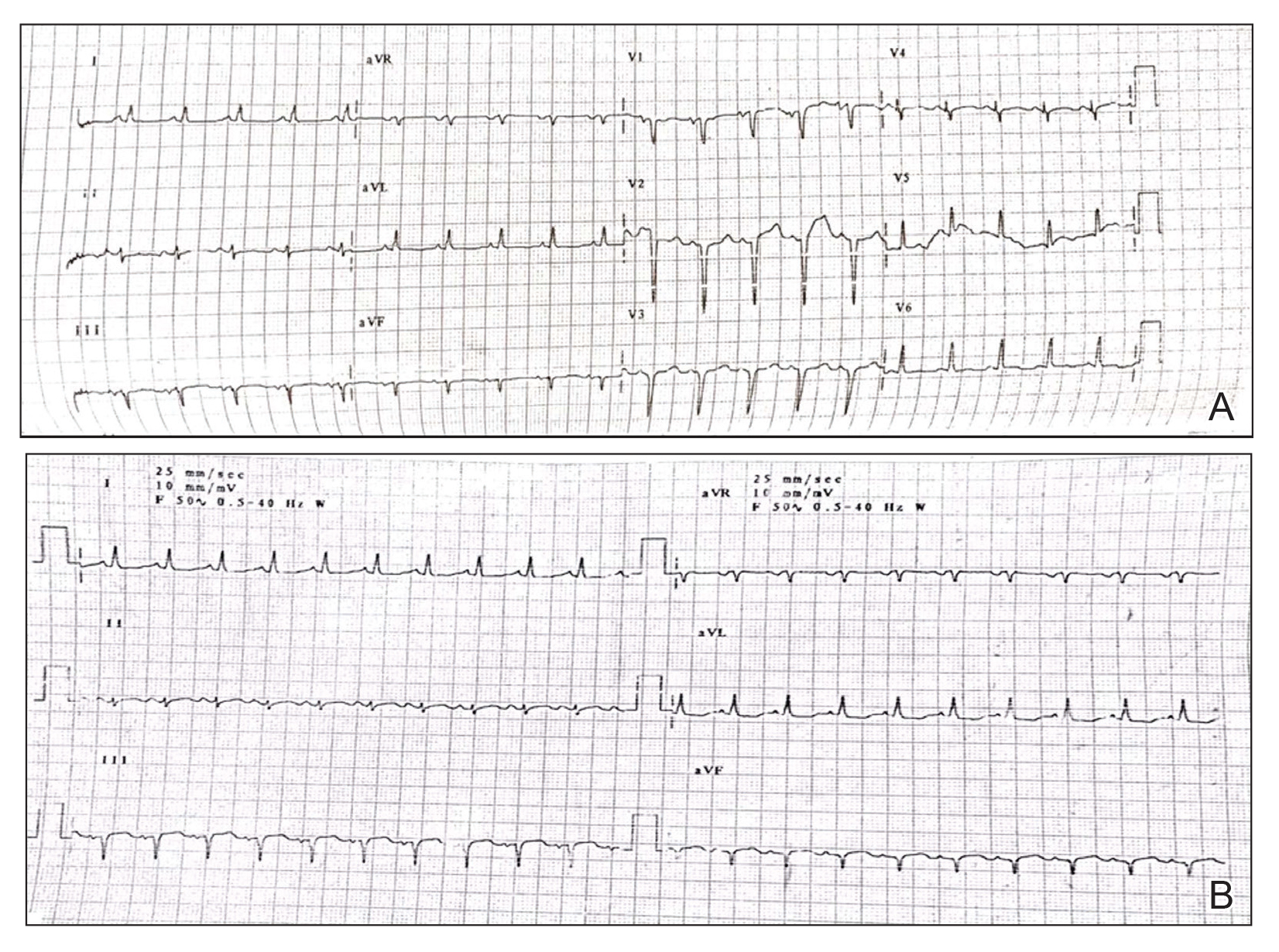

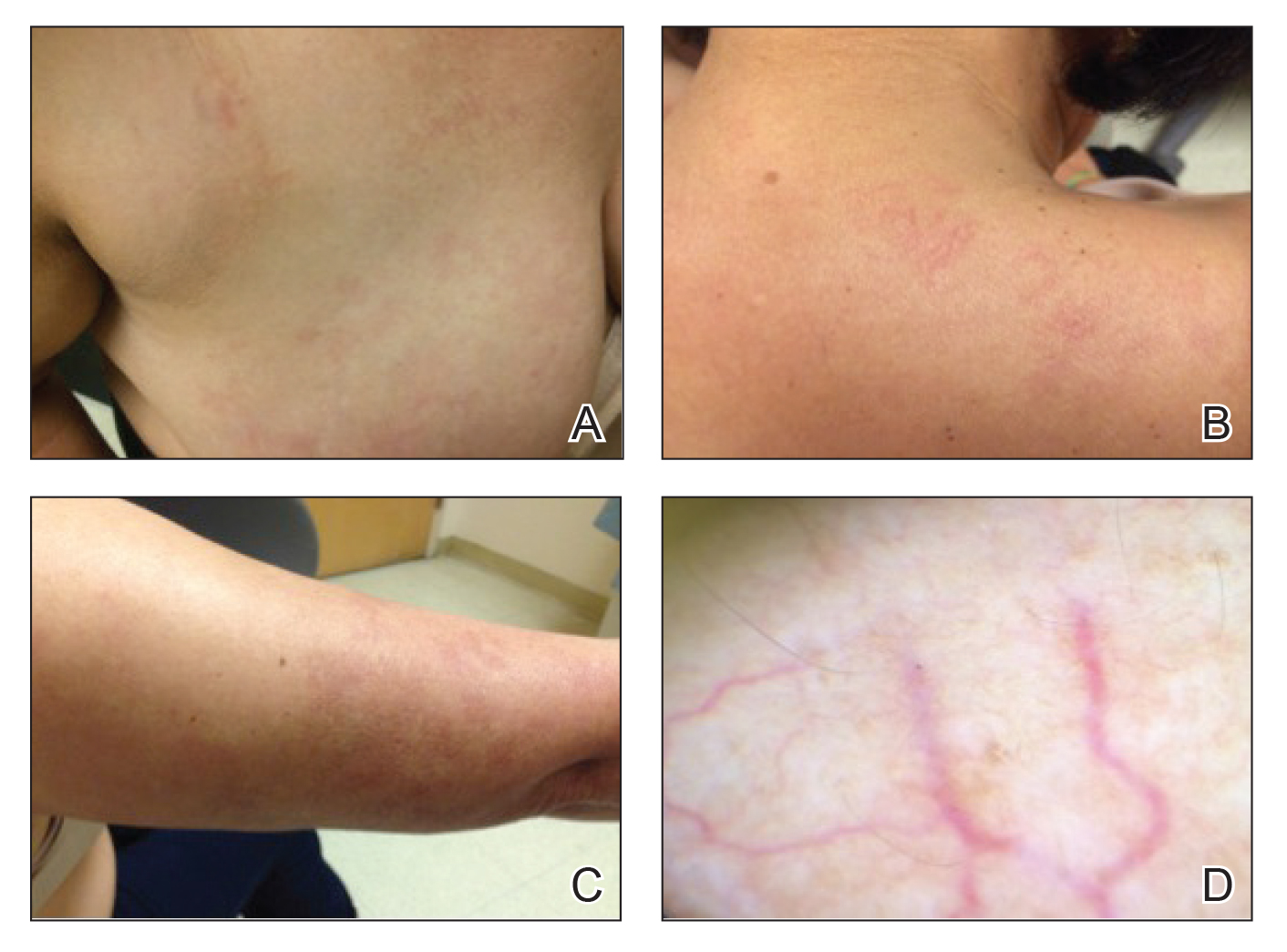

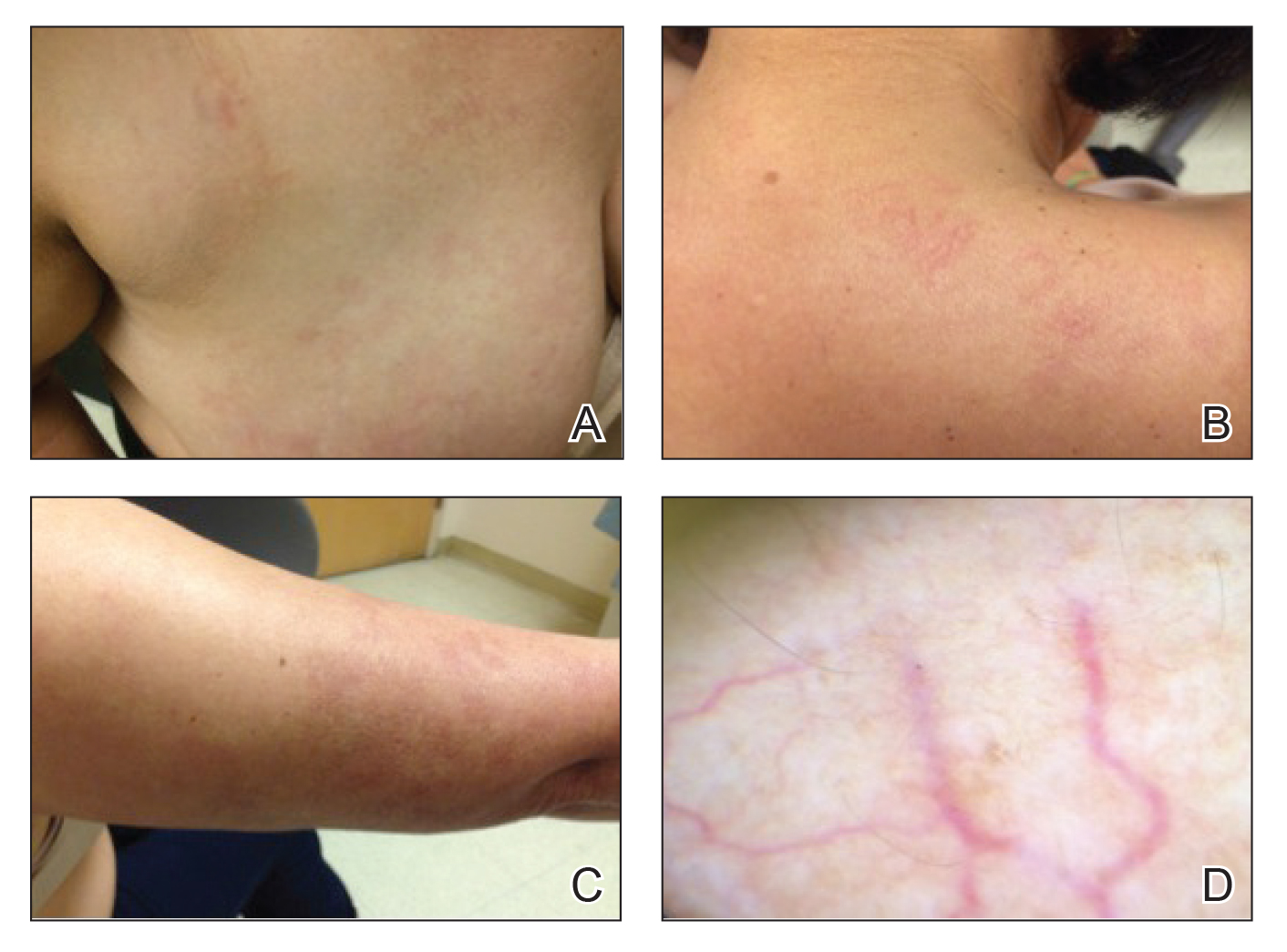

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.