User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Palmoplantar Eruption in a Patient With Mercury Poisoning

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

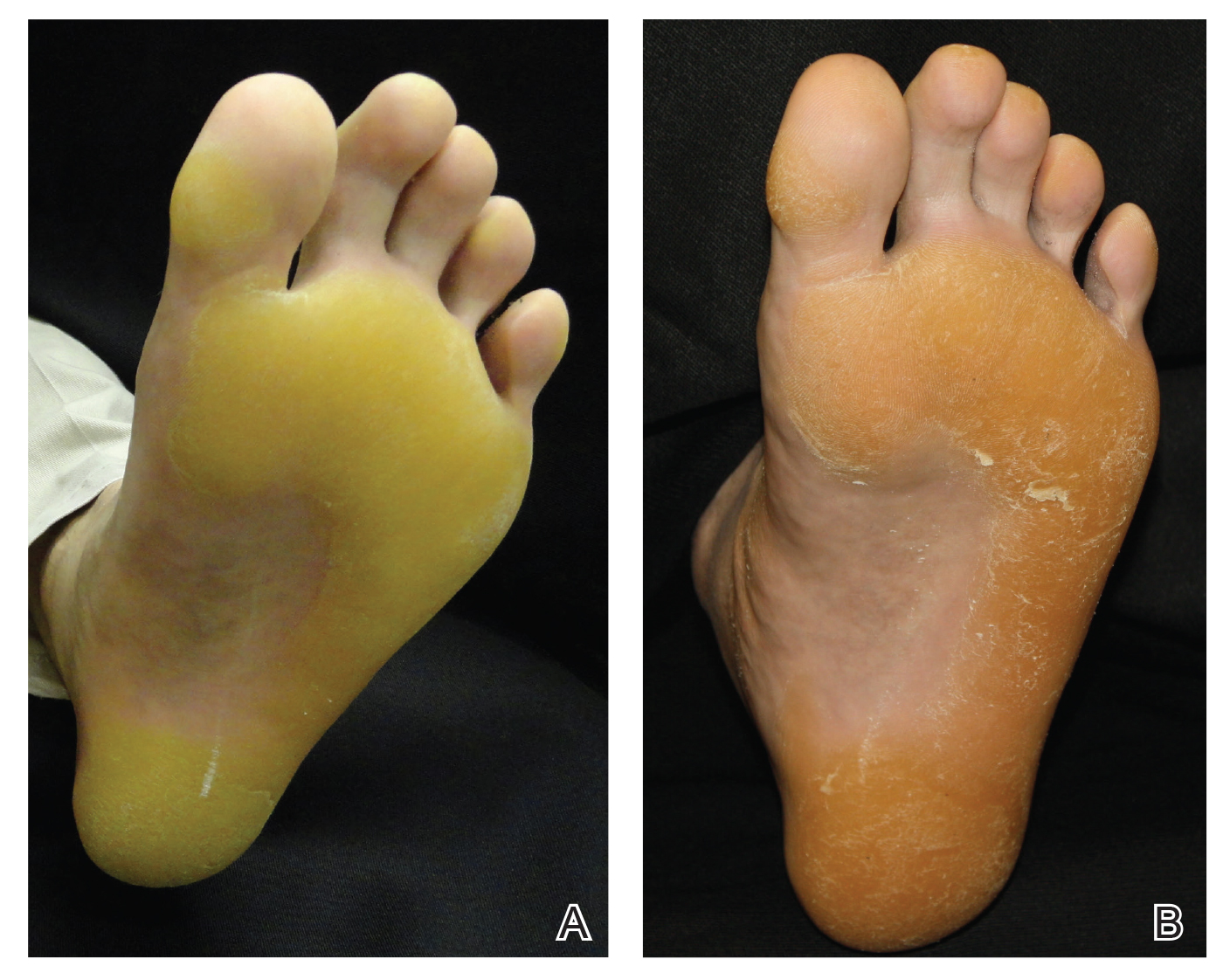

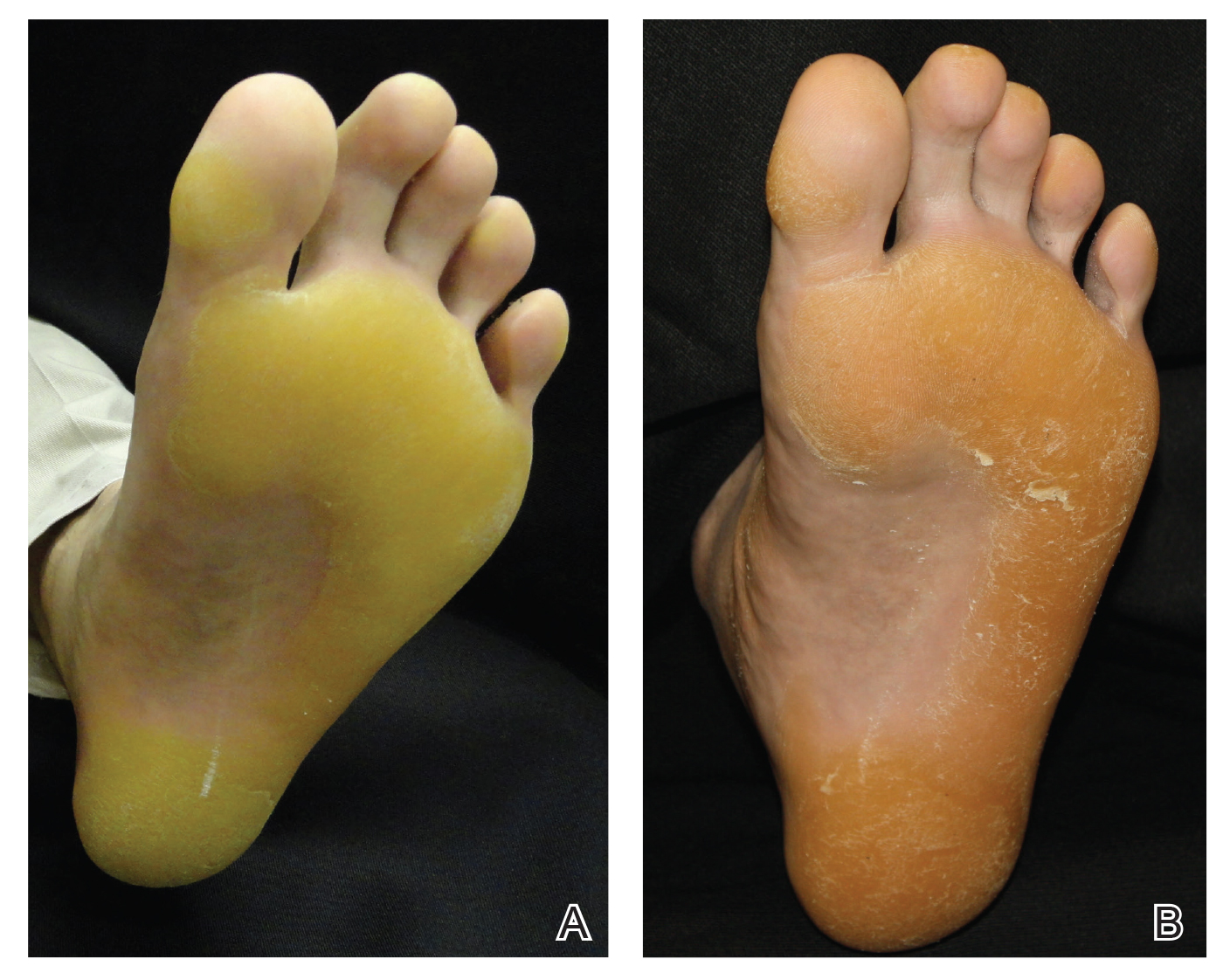

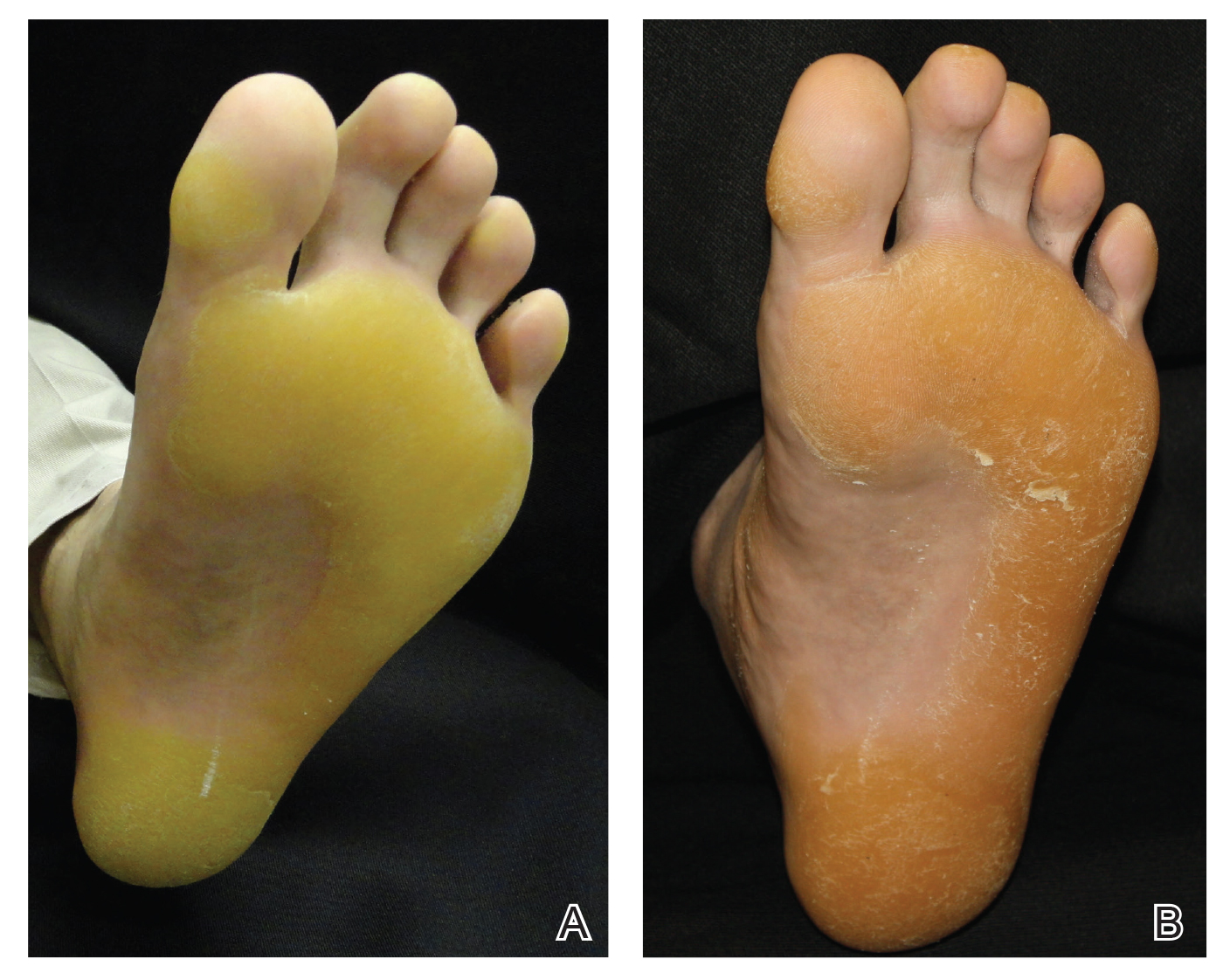

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

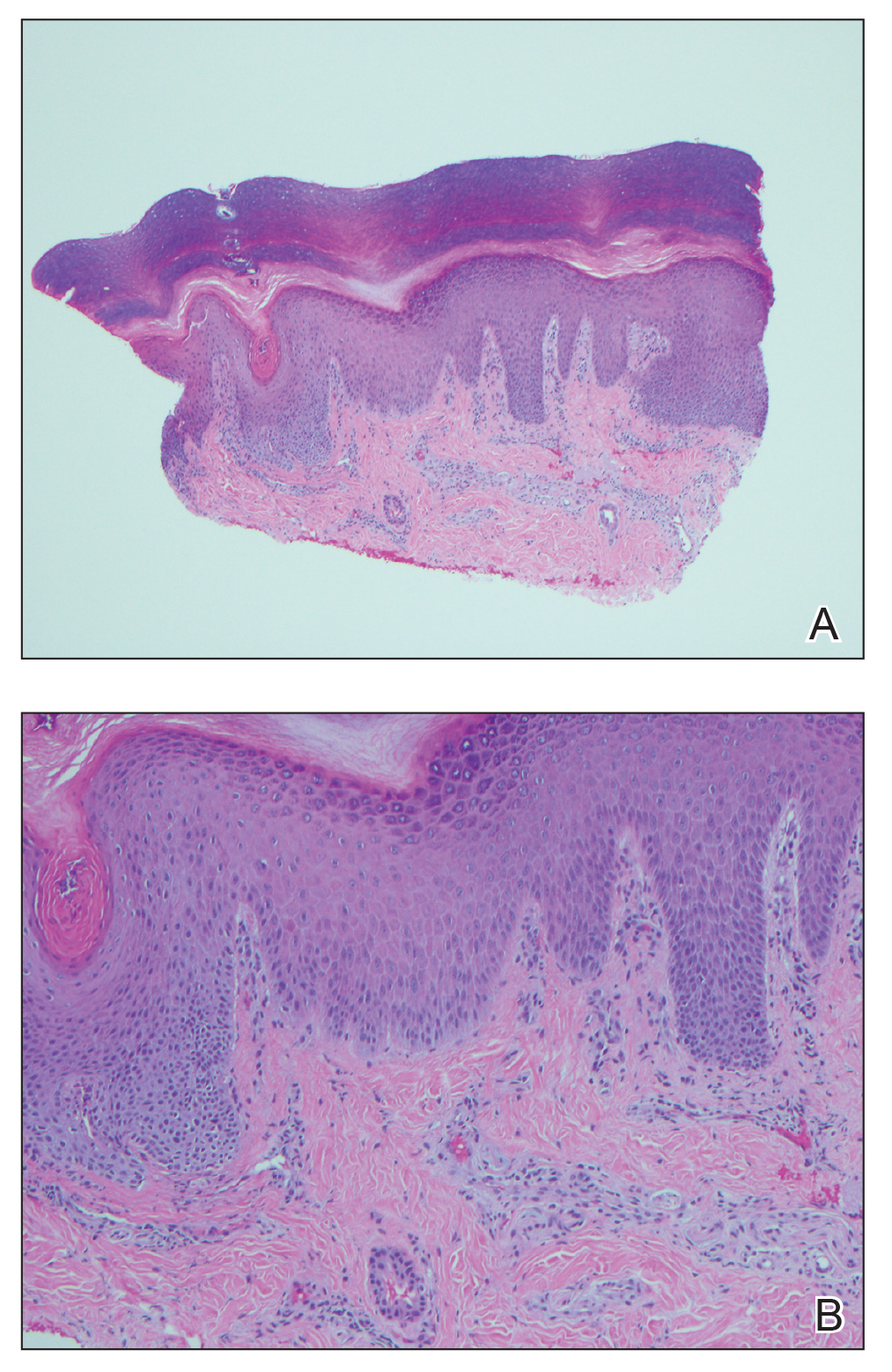

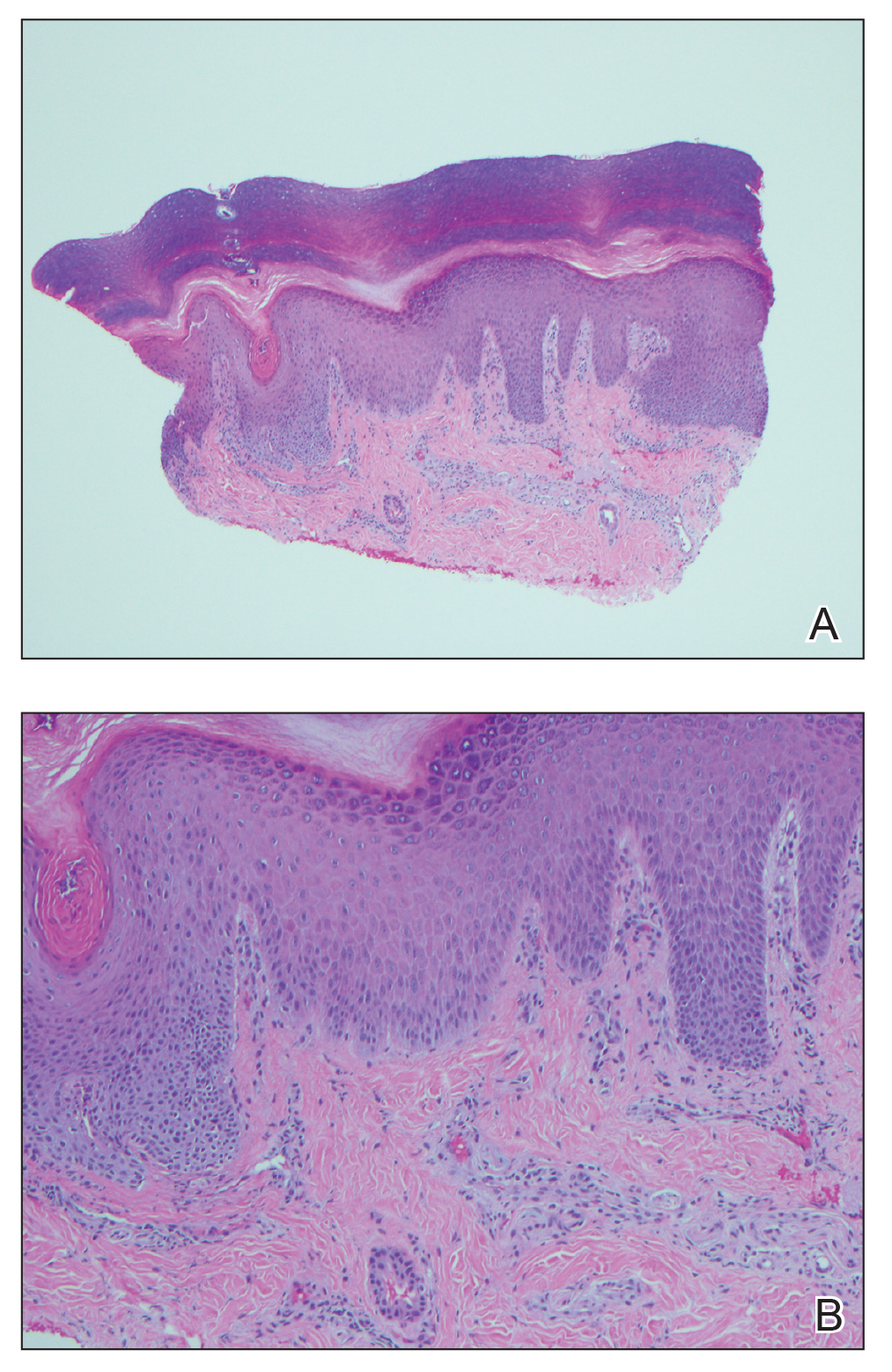

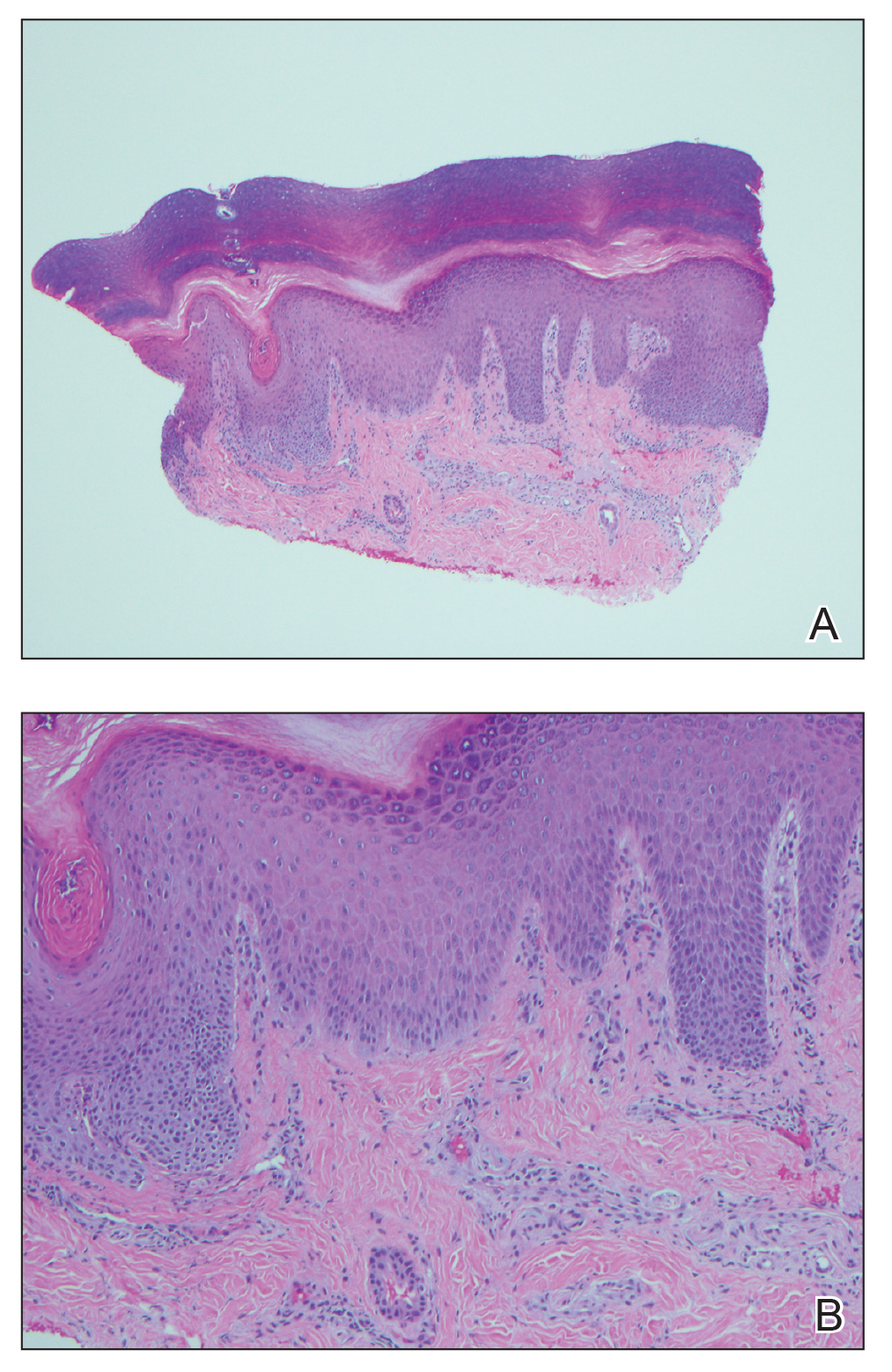

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

Practice Points

- The dermatologic and histologic presentation of mercury exposure may be nonspecific, requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion to make a diagnosis.

- Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with a rash of the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms.

What’s Eating You? Human Flea (Pulex irritans)

Characteristics

The ubiquitous human flea, Pulex irritans, is a hematophagous wingless ectoparasite in the order Siphonaptera (wingless siphon) that survives by consuming the blood of its mammalian and avian hosts. Due to diseases such as the bubonic plague, fleas have claimed more victims than all the wars ever fought; in the 14th century, the Black Death caused more than 200 million deaths. Fleas fossilized in amber have been found to be 200 million years old and closely resemble the modern human flea, demonstrating the resilience of the species.

The adult human flea is a small, reddish brown, laterally compressed, wingless insect that is approximately 2- to 3.5-mm long (females, 2.5–3.5 mm; males, 2–2.5 mm) and enclosed by a tough cuticle. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), P irritans has no combs or ctenidia (Figure 1). Fleas have large powerful hind legs enabling them to jump horizontally or vertically 200 times their body length (equivalent to a 6-foot human jumping 1200 feet) using stored muscle energy in a pad on the hind legs composed of the elastic protein resilin.1 They feed off a wide variety of hosts, including humans, pigs, cats, dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, chickens, owls, foxes, rabbits, mice, and feral cats. The flea’s mouthparts are highly specialized for piercing the skin and sucking its blood meal via direct capillary cannulation.

Life Cycle

There are 4 stages of the flea life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Most adult flea species mate on the host; the female will lay an average of 4 to 8 small white eggs on the host after each blood meal, laying more than 400 eggs during her lifetime. The eggs then drop from the host and hatch in approximately 4 to 6 days to become larvae. The active larvae feed on available organic matter in their environment, such as their parents’ feces and detritus, while undergoing 3 molts within 1 week to several months.2 The larva then spins a silken cocoon from modified salivary glands to form the pupa. In favorable conditions, the pupa lasts only a few weeks; however, it can last for a year or more in unfavorable conditions. Triggers for emergence of the adult flea from the pupa include high humidity, warm temperatures, increased levels of carbon dioxide, and vibrations including sound. An adult P irritans flea can live for a few weeks to more than 1.5 years in favorable conditions of lower air temperature, high relative humidity, and access to a host.3

Related Diseases

Pulex irritans can be a vector for several human diseases. Yersinia pestis is a gram-negative bacteria that causes plague, a highly virulent disease that killed millions of people during its 3 largest human pandemics. The black rat (Rattus rattus) and the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) have been implicated as initial vectors; however, transmission may be human-to-human with pneumonic plague, and septicemic plague may be spread via Pulex fleas or body lice.4,5 In 1971, Y pestis was isolated from P irritans on a dog in the home of a plague patient in Kayenta, Arizona.6Yersinia pestis bacterial DNA also was extracted from P irritans during a plague outbreak in Madagascar in 20147 and was implicated in epidemiologic studies of plague in Tanzania from 1986 to 2004, suggesting it also plays a role in endemic disease.8

Bartonellosis is an emerging disease caused by different species of the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Bartonella transmitted by lice, ticks, and fleas. Bartonella quintana causes trench fever primarily transmitted by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis, and resulted in more than 1 million cases during World War I. Trench fever is characterized by headache, fever, dizziness, and shin pain that lasts 1 to 3 days and recurs in cycles every 4 to 6 days. Other clinical manifestations of B quintana include chronic bacteremia, endocarditis, lymphadenopathy, and bacillary angiomatosis.9Bartonella henselae causes cat scratch fever, characterized by lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, joint pain, and lethargy from infected cat scratches or the bite of an infected flea. Bartonella rochalimae also has been found to cause a trench fever–like bacteremia.10Bartonella species have been found in P irritans, and the flea is implicated as a vector of bartonellosis in humans.11-15

Rickettsioses are worldwide diseases caused by the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Rickettsia transmitted to humans via hematophagous arthropods. The rickettsiae traditionally have been classified into the spotted fever or typhus groups. The spotted fever group (ie, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Mediterranean spotted fever) is transmitted via ticks. The typhus group is transmitted via lice (epidemic typhus) and fleas (endemic or murine typhus). Murine typhus can be caused by Rickettsia typhi in warm coastal areas around the world where the main mammal reservoir is the rat and the rat flea vector X cheopis. Clinical signs of infection are abrupt onset of fever, headaches, myalgia, malaise, and chills, with a truncal maculopapular rash progressing peripherally several days after the initial clinical signs. Rash is present in up to 50% of cases.16Rickettsia felis is an emerging flea-borne pathogen causing an acute febrile illness usually transmitted via the cat flea C felis.17Rickettsia species DNA have been found to be present in P irritans from dogs18 and livestock19 and pose a risk for causing rickettsioses in humans.

Environmental Treatment and Prevention

Flea bites present as intense, pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that usually are located on the lower extremities but also can be present on exposed areas of the upper extremities and hands (Figure 2). Human fleas infest clothing, and bites can be widespread. Topical antipruritics and corticosteroids can be used for controlling itch and the intense cutaneous inflammatory response. The flea host should be identified in areas of the home, school, farm, work, or local environment. House pets should be examined and treated by a veterinarian. The pet’s bedding should be washed and dried at high temperatures, and carpets and floors should be routinely vacuumed or cleaned to remove eggs, larvae, flea feces, and/or pupae. The killing of adult fleas with insecticidal products (eg, imidacloprid, fipronil, spinosad, selamectin, lufenuron, ivermectin) is the primary method of flea control. Use of insect growth regulators such as pyriproxyfen inhibits adult reproduction and blocks the organogenesis of immature larval stages via hormonal or enzymatic actions.20 The combination of an insecticide and an insect growth regulator appears to be most effective in their synergistic actions against adult fleas and larvae. There have been reports of insecticidal resistance in the flea population, especially with pyrethroids.21,22 A professional exterminator and veterinarian should be consulted. In recalcitrant cases, evaluation for other wild mammals or birds should be performed in unoccupied areas of the home such as the attic, crawl spaces, and basements, as well as inside walls.

Conclusion

The human flea, P irritans, is an important vector in the transmission of human diseases such as the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses. Flea bites present as intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that most commonly present on the lower extremities. Flea bites can be treated with topical steroids, and fleas can be controlled by a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

- Burrow M. How fleas jump. J Exp Biol. 2009;18:2881-2883.

- Buckland PC, Sandler JP. A biogeography of the human flea, Pulex irritans L (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Biogeogr. 1989;16:115-120.

- Krasnov BR. Life cycles. In: Krasnov BR, ed. Functional and Evolutional Ecology of Fleas. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008:45-67.

- Dean KR, Krauer F, Walloe L, et al. Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the second pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1304-1309.

- Hufthammer AK, Walloe L. Rats cannot have been intermediate hosts for Yersinia pestis during medieval plague epidemics in Northern Europe. J Archeol Sci. 2013;40:1752-1759.

- Archibald WS, Kunitz SJ. Detection of plague by testing serums of dogs on the Navajo Reservation. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:377-380.

- Ratovonjato J, Rajerison M, Rahelinirina S, et al. Yersinia pestis in Pulex irritans fleas during plague outbreak, Madagascar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1414-1415.

- Laudisoit A, Leirs H, Makundi RH, et al. Plague and the human flea, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:687-693.

- Foucault C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana characteristics and clinical management. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:217-223.

- Eremeeva ME, Gerns HL, Lydy SL, et al. Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2381-2387.11.

- Marquez FJ, Millan J, Rodriguez-Liebana JJ, et al. Detection and identification of Bartonella sp. in fleas from carnivorous mammals in Andalusia, Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:393-398.

- Perez-Martinez L, Venzal JM, Portillo A, et al. Bartonella rochalimae and other Bartonella spp. in fleas, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1150-1152.

- Sofer S, Gutierrez DM, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Molecular detection of zoonotic bartonellae (B. henselae, B. elizabethae and B. rochalimae) in fleas collected from dogs in Israel. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:344-348.

- Zouari S, Khrouf F, M’ghirbi Y, et al. First molecular detection and characterization of zoonotic Bartonella species in fleas infesting domestic animals in Tunisia. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:436.

- Rolain JM, Bourry, O, Davoust B, et al. Bartonella quintana and Rickettsia felis in Gabon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1742-1744.

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;166:16-24.

- Brown L, Macaluso KR. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:27-39.

- Oteo JA, Portillo A, Potero F, et al. ‘Candidatus Rickettsia asemboensis’ and Wolbachia spp. in Ctenocephalides felis and Pulex irritans fleas removed from dogs in Ecuador. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:455.

- Ghavami MB, Mirzadeh H, Mohammadi J, et al. Molecular survey of ITS spacer and Rickettsia infection in human flea, Pulex irritans. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:1433-1442.

- Traversa D. Fleas infesting pets in the era of emerging extra-intestinal nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:59.

- Rust MK. Insecticide resistance in fleas. Insects. 2016;7:10.

- Ghavami MB, Haghi FP, Alibabaei Z, et al. First report of target site insensitivity to pyrethroids in human flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pest Biochem Physiol. 2018;146:97-105.

Characteristics

The ubiquitous human flea, Pulex irritans, is a hematophagous wingless ectoparasite in the order Siphonaptera (wingless siphon) that survives by consuming the blood of its mammalian and avian hosts. Due to diseases such as the bubonic plague, fleas have claimed more victims than all the wars ever fought; in the 14th century, the Black Death caused more than 200 million deaths. Fleas fossilized in amber have been found to be 200 million years old and closely resemble the modern human flea, demonstrating the resilience of the species.

The adult human flea is a small, reddish brown, laterally compressed, wingless insect that is approximately 2- to 3.5-mm long (females, 2.5–3.5 mm; males, 2–2.5 mm) and enclosed by a tough cuticle. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), P irritans has no combs or ctenidia (Figure 1). Fleas have large powerful hind legs enabling them to jump horizontally or vertically 200 times their body length (equivalent to a 6-foot human jumping 1200 feet) using stored muscle energy in a pad on the hind legs composed of the elastic protein resilin.1 They feed off a wide variety of hosts, including humans, pigs, cats, dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, chickens, owls, foxes, rabbits, mice, and feral cats. The flea’s mouthparts are highly specialized for piercing the skin and sucking its blood meal via direct capillary cannulation.

Life Cycle

There are 4 stages of the flea life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Most adult flea species mate on the host; the female will lay an average of 4 to 8 small white eggs on the host after each blood meal, laying more than 400 eggs during her lifetime. The eggs then drop from the host and hatch in approximately 4 to 6 days to become larvae. The active larvae feed on available organic matter in their environment, such as their parents’ feces and detritus, while undergoing 3 molts within 1 week to several months.2 The larva then spins a silken cocoon from modified salivary glands to form the pupa. In favorable conditions, the pupa lasts only a few weeks; however, it can last for a year or more in unfavorable conditions. Triggers for emergence of the adult flea from the pupa include high humidity, warm temperatures, increased levels of carbon dioxide, and vibrations including sound. An adult P irritans flea can live for a few weeks to more than 1.5 years in favorable conditions of lower air temperature, high relative humidity, and access to a host.3

Related Diseases

Pulex irritans can be a vector for several human diseases. Yersinia pestis is a gram-negative bacteria that causes plague, a highly virulent disease that killed millions of people during its 3 largest human pandemics. The black rat (Rattus rattus) and the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) have been implicated as initial vectors; however, transmission may be human-to-human with pneumonic plague, and septicemic plague may be spread via Pulex fleas or body lice.4,5 In 1971, Y pestis was isolated from P irritans on a dog in the home of a plague patient in Kayenta, Arizona.6Yersinia pestis bacterial DNA also was extracted from P irritans during a plague outbreak in Madagascar in 20147 and was implicated in epidemiologic studies of plague in Tanzania from 1986 to 2004, suggesting it also plays a role in endemic disease.8

Bartonellosis is an emerging disease caused by different species of the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Bartonella transmitted by lice, ticks, and fleas. Bartonella quintana causes trench fever primarily transmitted by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis, and resulted in more than 1 million cases during World War I. Trench fever is characterized by headache, fever, dizziness, and shin pain that lasts 1 to 3 days and recurs in cycles every 4 to 6 days. Other clinical manifestations of B quintana include chronic bacteremia, endocarditis, lymphadenopathy, and bacillary angiomatosis.9Bartonella henselae causes cat scratch fever, characterized by lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, joint pain, and lethargy from infected cat scratches or the bite of an infected flea. Bartonella rochalimae also has been found to cause a trench fever–like bacteremia.10Bartonella species have been found in P irritans, and the flea is implicated as a vector of bartonellosis in humans.11-15

Rickettsioses are worldwide diseases caused by the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Rickettsia transmitted to humans via hematophagous arthropods. The rickettsiae traditionally have been classified into the spotted fever or typhus groups. The spotted fever group (ie, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Mediterranean spotted fever) is transmitted via ticks. The typhus group is transmitted via lice (epidemic typhus) and fleas (endemic or murine typhus). Murine typhus can be caused by Rickettsia typhi in warm coastal areas around the world where the main mammal reservoir is the rat and the rat flea vector X cheopis. Clinical signs of infection are abrupt onset of fever, headaches, myalgia, malaise, and chills, with a truncal maculopapular rash progressing peripherally several days after the initial clinical signs. Rash is present in up to 50% of cases.16Rickettsia felis is an emerging flea-borne pathogen causing an acute febrile illness usually transmitted via the cat flea C felis.17Rickettsia species DNA have been found to be present in P irritans from dogs18 and livestock19 and pose a risk for causing rickettsioses in humans.

Environmental Treatment and Prevention

Flea bites present as intense, pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that usually are located on the lower extremities but also can be present on exposed areas of the upper extremities and hands (Figure 2). Human fleas infest clothing, and bites can be widespread. Topical antipruritics and corticosteroids can be used for controlling itch and the intense cutaneous inflammatory response. The flea host should be identified in areas of the home, school, farm, work, or local environment. House pets should be examined and treated by a veterinarian. The pet’s bedding should be washed and dried at high temperatures, and carpets and floors should be routinely vacuumed or cleaned to remove eggs, larvae, flea feces, and/or pupae. The killing of adult fleas with insecticidal products (eg, imidacloprid, fipronil, spinosad, selamectin, lufenuron, ivermectin) is the primary method of flea control. Use of insect growth regulators such as pyriproxyfen inhibits adult reproduction and blocks the organogenesis of immature larval stages via hormonal or enzymatic actions.20 The combination of an insecticide and an insect growth regulator appears to be most effective in their synergistic actions against adult fleas and larvae. There have been reports of insecticidal resistance in the flea population, especially with pyrethroids.21,22 A professional exterminator and veterinarian should be consulted. In recalcitrant cases, evaluation for other wild mammals or birds should be performed in unoccupied areas of the home such as the attic, crawl spaces, and basements, as well as inside walls.

Conclusion

The human flea, P irritans, is an important vector in the transmission of human diseases such as the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses. Flea bites present as intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that most commonly present on the lower extremities. Flea bites can be treated with topical steroids, and fleas can be controlled by a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

Characteristics

The ubiquitous human flea, Pulex irritans, is a hematophagous wingless ectoparasite in the order Siphonaptera (wingless siphon) that survives by consuming the blood of its mammalian and avian hosts. Due to diseases such as the bubonic plague, fleas have claimed more victims than all the wars ever fought; in the 14th century, the Black Death caused more than 200 million deaths. Fleas fossilized in amber have been found to be 200 million years old and closely resemble the modern human flea, demonstrating the resilience of the species.

The adult human flea is a small, reddish brown, laterally compressed, wingless insect that is approximately 2- to 3.5-mm long (females, 2.5–3.5 mm; males, 2–2.5 mm) and enclosed by a tough cuticle. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), P irritans has no combs or ctenidia (Figure 1). Fleas have large powerful hind legs enabling them to jump horizontally or vertically 200 times their body length (equivalent to a 6-foot human jumping 1200 feet) using stored muscle energy in a pad on the hind legs composed of the elastic protein resilin.1 They feed off a wide variety of hosts, including humans, pigs, cats, dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, chickens, owls, foxes, rabbits, mice, and feral cats. The flea’s mouthparts are highly specialized for piercing the skin and sucking its blood meal via direct capillary cannulation.

Life Cycle

There are 4 stages of the flea life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Most adult flea species mate on the host; the female will lay an average of 4 to 8 small white eggs on the host after each blood meal, laying more than 400 eggs during her lifetime. The eggs then drop from the host and hatch in approximately 4 to 6 days to become larvae. The active larvae feed on available organic matter in their environment, such as their parents’ feces and detritus, while undergoing 3 molts within 1 week to several months.2 The larva then spins a silken cocoon from modified salivary glands to form the pupa. In favorable conditions, the pupa lasts only a few weeks; however, it can last for a year or more in unfavorable conditions. Triggers for emergence of the adult flea from the pupa include high humidity, warm temperatures, increased levels of carbon dioxide, and vibrations including sound. An adult P irritans flea can live for a few weeks to more than 1.5 years in favorable conditions of lower air temperature, high relative humidity, and access to a host.3

Related Diseases

Pulex irritans can be a vector for several human diseases. Yersinia pestis is a gram-negative bacteria that causes plague, a highly virulent disease that killed millions of people during its 3 largest human pandemics. The black rat (Rattus rattus) and the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) have been implicated as initial vectors; however, transmission may be human-to-human with pneumonic plague, and septicemic plague may be spread via Pulex fleas or body lice.4,5 In 1971, Y pestis was isolated from P irritans on a dog in the home of a plague patient in Kayenta, Arizona.6Yersinia pestis bacterial DNA also was extracted from P irritans during a plague outbreak in Madagascar in 20147 and was implicated in epidemiologic studies of plague in Tanzania from 1986 to 2004, suggesting it also plays a role in endemic disease.8

Bartonellosis is an emerging disease caused by different species of the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Bartonella transmitted by lice, ticks, and fleas. Bartonella quintana causes trench fever primarily transmitted by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis, and resulted in more than 1 million cases during World War I. Trench fever is characterized by headache, fever, dizziness, and shin pain that lasts 1 to 3 days and recurs in cycles every 4 to 6 days. Other clinical manifestations of B quintana include chronic bacteremia, endocarditis, lymphadenopathy, and bacillary angiomatosis.9Bartonella henselae causes cat scratch fever, characterized by lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, joint pain, and lethargy from infected cat scratches or the bite of an infected flea. Bartonella rochalimae also has been found to cause a trench fever–like bacteremia.10Bartonella species have been found in P irritans, and the flea is implicated as a vector of bartonellosis in humans.11-15

Rickettsioses are worldwide diseases caused by the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Rickettsia transmitted to humans via hematophagous arthropods. The rickettsiae traditionally have been classified into the spotted fever or typhus groups. The spotted fever group (ie, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Mediterranean spotted fever) is transmitted via ticks. The typhus group is transmitted via lice (epidemic typhus) and fleas (endemic or murine typhus). Murine typhus can be caused by Rickettsia typhi in warm coastal areas around the world where the main mammal reservoir is the rat and the rat flea vector X cheopis. Clinical signs of infection are abrupt onset of fever, headaches, myalgia, malaise, and chills, with a truncal maculopapular rash progressing peripherally several days after the initial clinical signs. Rash is present in up to 50% of cases.16Rickettsia felis is an emerging flea-borne pathogen causing an acute febrile illness usually transmitted via the cat flea C felis.17Rickettsia species DNA have been found to be present in P irritans from dogs18 and livestock19 and pose a risk for causing rickettsioses in humans.

Environmental Treatment and Prevention

Flea bites present as intense, pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that usually are located on the lower extremities but also can be present on exposed areas of the upper extremities and hands (Figure 2). Human fleas infest clothing, and bites can be widespread. Topical antipruritics and corticosteroids can be used for controlling itch and the intense cutaneous inflammatory response. The flea host should be identified in areas of the home, school, farm, work, or local environment. House pets should be examined and treated by a veterinarian. The pet’s bedding should be washed and dried at high temperatures, and carpets and floors should be routinely vacuumed or cleaned to remove eggs, larvae, flea feces, and/or pupae. The killing of adult fleas with insecticidal products (eg, imidacloprid, fipronil, spinosad, selamectin, lufenuron, ivermectin) is the primary method of flea control. Use of insect growth regulators such as pyriproxyfen inhibits adult reproduction and blocks the organogenesis of immature larval stages via hormonal or enzymatic actions.20 The combination of an insecticide and an insect growth regulator appears to be most effective in their synergistic actions against adult fleas and larvae. There have been reports of insecticidal resistance in the flea population, especially with pyrethroids.21,22 A professional exterminator and veterinarian should be consulted. In recalcitrant cases, evaluation for other wild mammals or birds should be performed in unoccupied areas of the home such as the attic, crawl spaces, and basements, as well as inside walls.

Conclusion

The human flea, P irritans, is an important vector in the transmission of human diseases such as the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses. Flea bites present as intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that most commonly present on the lower extremities. Flea bites can be treated with topical steroids, and fleas can be controlled by a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

- Burrow M. How fleas jump. J Exp Biol. 2009;18:2881-2883.

- Buckland PC, Sandler JP. A biogeography of the human flea, Pulex irritans L (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Biogeogr. 1989;16:115-120.

- Krasnov BR. Life cycles. In: Krasnov BR, ed. Functional and Evolutional Ecology of Fleas. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008:45-67.

- Dean KR, Krauer F, Walloe L, et al. Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the second pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1304-1309.

- Hufthammer AK, Walloe L. Rats cannot have been intermediate hosts for Yersinia pestis during medieval plague epidemics in Northern Europe. J Archeol Sci. 2013;40:1752-1759.

- Archibald WS, Kunitz SJ. Detection of plague by testing serums of dogs on the Navajo Reservation. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:377-380.

- Ratovonjato J, Rajerison M, Rahelinirina S, et al. Yersinia pestis in Pulex irritans fleas during plague outbreak, Madagascar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1414-1415.

- Laudisoit A, Leirs H, Makundi RH, et al. Plague and the human flea, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:687-693.

- Foucault C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana characteristics and clinical management. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:217-223.

- Eremeeva ME, Gerns HL, Lydy SL, et al. Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2381-2387.11.

- Marquez FJ, Millan J, Rodriguez-Liebana JJ, et al. Detection and identification of Bartonella sp. in fleas from carnivorous mammals in Andalusia, Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:393-398.

- Perez-Martinez L, Venzal JM, Portillo A, et al. Bartonella rochalimae and other Bartonella spp. in fleas, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1150-1152.

- Sofer S, Gutierrez DM, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Molecular detection of zoonotic bartonellae (B. henselae, B. elizabethae and B. rochalimae) in fleas collected from dogs in Israel. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:344-348.

- Zouari S, Khrouf F, M’ghirbi Y, et al. First molecular detection and characterization of zoonotic Bartonella species in fleas infesting domestic animals in Tunisia. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:436.

- Rolain JM, Bourry, O, Davoust B, et al. Bartonella quintana and Rickettsia felis in Gabon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1742-1744.

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;166:16-24.

- Brown L, Macaluso KR. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:27-39.

- Oteo JA, Portillo A, Potero F, et al. ‘Candidatus Rickettsia asemboensis’ and Wolbachia spp. in Ctenocephalides felis and Pulex irritans fleas removed from dogs in Ecuador. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:455.

- Ghavami MB, Mirzadeh H, Mohammadi J, et al. Molecular survey of ITS spacer and Rickettsia infection in human flea, Pulex irritans. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:1433-1442.

- Traversa D. Fleas infesting pets in the era of emerging extra-intestinal nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:59.

- Rust MK. Insecticide resistance in fleas. Insects. 2016;7:10.

- Ghavami MB, Haghi FP, Alibabaei Z, et al. First report of target site insensitivity to pyrethroids in human flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pest Biochem Physiol. 2018;146:97-105.

- Burrow M. How fleas jump. J Exp Biol. 2009;18:2881-2883.

- Buckland PC, Sandler JP. A biogeography of the human flea, Pulex irritans L (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Biogeogr. 1989;16:115-120.

- Krasnov BR. Life cycles. In: Krasnov BR, ed. Functional and Evolutional Ecology of Fleas. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008:45-67.

- Dean KR, Krauer F, Walloe L, et al. Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the second pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1304-1309.

- Hufthammer AK, Walloe L. Rats cannot have been intermediate hosts for Yersinia pestis during medieval plague epidemics in Northern Europe. J Archeol Sci. 2013;40:1752-1759.

- Archibald WS, Kunitz SJ. Detection of plague by testing serums of dogs on the Navajo Reservation. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:377-380.

- Ratovonjato J, Rajerison M, Rahelinirina S, et al. Yersinia pestis in Pulex irritans fleas during plague outbreak, Madagascar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1414-1415.

- Laudisoit A, Leirs H, Makundi RH, et al. Plague and the human flea, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:687-693.

- Foucault C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana characteristics and clinical management. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:217-223.

- Eremeeva ME, Gerns HL, Lydy SL, et al. Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2381-2387.11.

- Marquez FJ, Millan J, Rodriguez-Liebana JJ, et al. Detection and identification of Bartonella sp. in fleas from carnivorous mammals in Andalusia, Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:393-398.

- Perez-Martinez L, Venzal JM, Portillo A, et al. Bartonella rochalimae and other Bartonella spp. in fleas, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1150-1152.

- Sofer S, Gutierrez DM, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Molecular detection of zoonotic bartonellae (B. henselae, B. elizabethae and B. rochalimae) in fleas collected from dogs in Israel. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:344-348.

- Zouari S, Khrouf F, M’ghirbi Y, et al. First molecular detection and characterization of zoonotic Bartonella species in fleas infesting domestic animals in Tunisia. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:436.

- Rolain JM, Bourry, O, Davoust B, et al. Bartonella quintana and Rickettsia felis in Gabon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1742-1744.

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;166:16-24.

- Brown L, Macaluso KR. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:27-39.

- Oteo JA, Portillo A, Potero F, et al. ‘Candidatus Rickettsia asemboensis’ and Wolbachia spp. in Ctenocephalides felis and Pulex irritans fleas removed from dogs in Ecuador. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:455.

- Ghavami MB, Mirzadeh H, Mohammadi J, et al. Molecular survey of ITS spacer and Rickettsia infection in human flea, Pulex irritans. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:1433-1442.

- Traversa D. Fleas infesting pets in the era of emerging extra-intestinal nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:59.

- Rust MK. Insecticide resistance in fleas. Insects. 2016;7:10.

- Ghavami MB, Haghi FP, Alibabaei Z, et al. First report of target site insensitivity to pyrethroids in human flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pest Biochem Physiol. 2018;146:97-105.

Practice Points

- The human flea, Pulex irritans, is a vector for various human diseases including the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses.

- Presenting symptoms of flea bites include intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules on exposed areas of skin.

- The primary method of flea control includes a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

Intraoperative Tissue Expansion to Allow Primary Linear Closure of 2 Large Adjacent Surgical Defects

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5

In our patient, closing the high-tension wound of the scalp would have prevented both wounds from being closed in a linear fashion without first stretching the tissue. Although Zitelli5 has cited that many wounds will heal well on their own despite a large size, many patients prefer the cosmetic appearance and shorter healing time of wounds that have been closed with sutures, particularly if those defects are greater than 8-mm wide. In contrast, patients preferred the cosmetic appearance of 4-mm wounds that healed via secondary intention.6 In our case, we closed the majority of the wound and left a small 4-mm-wide portion to heal on its own. The overall outcome was excellent and healed much quicker than leaving the entire scalp defect to heal by secondary intention.

The other methods of closure, such as a 2-to-Z flap, would have been difficult given the orientation of the lesions and the island between them.2 To create this flap, an extensive amount of undermining would have been necessary, leading to serious disruption of the blood and nerve supply and an increased risk for flap necrosis. Creating 1 large wound and repairing with a flap would have similar requirements and complications.

Intraoperative tissue relaxation can be used to allow primary closure of adjacent wounds without the need for undermining. Prior research has shown that 30 minutes of stress relaxation with 20 Newtons of applied tension yields a 65% reduction in wound-closure tension.7 Orienting the devices between 45° to 90° angles to one another creates opposing tension vectors so that the closure of one defect does not prevent the closure of the other defect. Even in cases in which the defects cannot be completely approximated, closing the wound edges to create a smaller central defect can decrease healing time and lead to an excellent cosmetic outcome without the need for a flap or graft.

The SUTUREGARD ISR suture retention bridge also is cost-effective for the surgeon and the patient. The device and suture-guide washer are included in a set that retails for $35 each or $300 for a box of 12.8 The suture most commonly used to secure the device in our practice is 2-0 nylon and retails for approximately $34 for a box of 12,9 which brings the total cost with the device to around $38 per use. The updated Current Procedural Terminology guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services define that an intermediate repair requires a layered closure and may include, but does not require, limited undermining. A complex linear closure must meet criteria for an intermediate closure plus at least 1 additional criterion, such as exposure of cartilage, bone, or tendons within the defect; extensive undermining; wound-edge debridement; involvement of free margins; or use of a retention suture.10 Use of a suture retention bridge such as the SUTUREGARD ISR device and therefore a retention suture qualifies the repair as a complex linear closure. Overall, use of the device expands the surgeon’s choices for surgical closures and helps to limit the need for larger, more invasive repair procedures.

- McGinness JL, Parlette HL. A novel technique using a rotation flap for repairing adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:272-275.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. 2-to-Z flap for reconstruction of adjacent skin defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E77-E78.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. The use of a suture retention device to enhance tissue expansion and healing in the repair of scalp and lower leg wounds. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:655-661.

- Zivony D, Siegle RJ. Burrow’s wedge advancement flaps for reconstruction of adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1162-1164.

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106.

- Christenson LJ, Phillips PK, Weaver AL, et al. Primary closure vs second-intention treatment of skin punch biopsy sites: a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1093-1099.

- Lear W, Blattner CM, Mustoe TA, et al. In vivo stress relaxation of human scalp. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:85-89.

- SUTUREGARD purchasing facts. SUTUREGARD® Medical Inc website. https://suturegard.com/SUTUREGARD-Purchasing-Facts. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shop products: suture with needle McKesson nonabsorbable uncoated black suture monofilament nylon size 2-0 18 inch suture 1-needle 26 mm length 3/8 circle reverse cutting needle. McKesson website. https://mms.mckesson.com/catalog?query=1034509. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Norris S. 2020 CPT updates to wound repair guidelines. Zotec Partners website. http://zotecpartners.com/resources/2020-cpt-updates-to-wound-repair-guidelines/. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5