User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Emergency Contraception Recommended for Teens on Isotretinoin

TORONTO —

That was one of the main messages from Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, Penn State University, Hershey, who discussed hormonal therapies for pediatric acne at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Many doctors are reluctant to prescribe EC, which refers to contraceptive methods used to prevent unintended pregnancy after unprotected sexual intercourse or contraceptive failure, whether that’s from discomfort with EC or lack of training, Dr. Zaenglein said in an interview.

Isotretinoin, a retinoid marketed as Accutane and other brand names, is an effective treatment for acne but carries serious teratogenicity risks; the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy is designed to manage this risk and minimize fetal exposure. Yet from 2011 to 2017, 210-310 pregnancies per year were reported to the Food and Drug Administration, according to a 2019 study.

There is a knowledge gap regarding EC among dermatologists who prescribe isotretinoin, which “is perpetuated by the iPLEDGE program because it is inadequate in guiding clinicians or educating patients about the use of EC,” Dr. Zaenglein and colleagues wrote in a recently published viewpoint on EC prescribing in patients on isotretinoin.

Types of EC include oral levonorgestrel (plan B), available over the counter; oral ulipristal acetate (ella), which requires a prescription; and the copper/hormonal intrauterine device.

Not all teens taking isotretinoin can be trusted to be sexually abstinent. Dr. Zaenglein cited research showing 39% of female high school students have had sexual relations. “In my opinion, these patients should have emergency contraception prescribed to them as a backup,” she said.

Dr. Zaenglein believes there’s a fair amount of “misunderstanding” about EC, with many people thinking it’s an abortion pill. “It’s a totally different medicine. This is contraception; if you’re pregnant, it’s not going to affect your fetus.”

Outgoing SPD President Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, agreed that Dr. Zaenglein raised an important issue. “She has identified a practice gap and a knowledge gap that we need to address,” she said in an interview.

When discussing contraception with female patients taking isotretinoin, assume they’re sexually active or could be, Dr. Zaenglein told meeting attendees. Be explicit about the risks to the fetus and consider their past compliance.

Complex Disorder

During her presentation, Dr. Zaenglein described acne as a “very complex, multifactorial inflammatory disorder” of the skin. It involves four steps: Increased sebum production, hyperkeratinization, Cutibacterium acnes, and inflammation. External factors such as diet, genes, and the environment play a role.

“But at the heart of all of it is androgens; if you didn’t have androgens, you wouldn’t have acne.” That’s why some acne treatments block androgen receptors.

Clinicians are increasingly using one such therapy, spironolactone, to treat acne in female adolescents. Dr. Zaenglein referred to a Mayo Clinic study of 80 patients (mean age, 19 years), who had moderate to severe acne treated with a mean dose of 100 mg/day, that found 80% had improvement with a favorable side effect profile. This included nearly 23% who had a complete response (90% or more) and 36% who had a partial response (more than 50%); 20% had no response.

However, response rates are higher in adults, said Dr. Zaenglein, noting that spironolactone works “much better” in adult women.

Side effects of spironolactone can include menstrual disturbances, breast enlargement and tenderness, and premenstrual syndrome–like symptoms.

Dermatologists should also consider combined oral contraceptives (COCs) in their adolescent patients with acne. These have an estrogen component as well as a progestin component.

They have proven effectiveness for acne in adolescents, yet a US survey of 170 dermatology residents found only 60% felt comfortable prescribing them to healthy adolescents. The survey also found only 62% of respondents felt adequately trained on the efficacy of COCs, and 42% felt adequately trained on their safety.

Contraindications for COCs include thrombosis, migraine with aura, lupus, seizures, and hypertension. Complex valvular heart disease and liver tumors also need to be ruled out, said Dr. Zaenglein. One of the “newer concerns” with COCs is depression. “There’s biological plausibility because, obviously, hormones impact the brain.”

Preventing Drug Interactions

Before prescribing hormonal therapy, clinicians should carry out an acne assessment, aimed in part at preventing drug interactions. “The one we mostly have to watch out for is rifampin,” an antibiotic that could interact with COCs, said Dr. Zaenglein.

The herbal supplement St John’s Wort can reduce the efficacy of COCs. “You also want to make sure that they’re not on any medicines that will increase potassium, such as ACE inhibitors,” said Dr. Zaenglein. But tetracyclines, ampicillin, or metronidazole are usually “all okay” when combined with COCs.

It’s important to get baseline blood pressure levels and to check these along with weight on a regular basis, she added.

Always Consider PCOS

Before starting hormonal therapy, she advises dermatologists to “always consider” polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a condition that’s “probably much underdiagnosed.” Acne is common in adolescents with PCOS. She suggests using a PCOS checklist, a reminder to ask about irregular periods, hirsutism, signs of insulin resistance such as increased body mass index, a history of premature adrenarche, and a family history of PCOS, said Dr. Zaenglein, noting that a person with a sibling who has PCOS has about a 40% chance of developing the condition.

“We play an important role in getting kids diagnosed at an early age so that we can make interventions because the impact of the metabolic syndrome can have lifelong effects on their cardiovascular system, as well as infertility.”

Dr. Zaenglein is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Acne Guidelines work group, the immediate past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society, a member of the AAD iPLEDGE work group, co–editor in chief of Pediatric Dermatology, an advisory board member of Ortho Dermatologics, and a consultant for Church & Dwight. Dr. Maguiness had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TORONTO —

That was one of the main messages from Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, Penn State University, Hershey, who discussed hormonal therapies for pediatric acne at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Many doctors are reluctant to prescribe EC, which refers to contraceptive methods used to prevent unintended pregnancy after unprotected sexual intercourse or contraceptive failure, whether that’s from discomfort with EC or lack of training, Dr. Zaenglein said in an interview.

Isotretinoin, a retinoid marketed as Accutane and other brand names, is an effective treatment for acne but carries serious teratogenicity risks; the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy is designed to manage this risk and minimize fetal exposure. Yet from 2011 to 2017, 210-310 pregnancies per year were reported to the Food and Drug Administration, according to a 2019 study.

There is a knowledge gap regarding EC among dermatologists who prescribe isotretinoin, which “is perpetuated by the iPLEDGE program because it is inadequate in guiding clinicians or educating patients about the use of EC,” Dr. Zaenglein and colleagues wrote in a recently published viewpoint on EC prescribing in patients on isotretinoin.

Types of EC include oral levonorgestrel (plan B), available over the counter; oral ulipristal acetate (ella), which requires a prescription; and the copper/hormonal intrauterine device.

Not all teens taking isotretinoin can be trusted to be sexually abstinent. Dr. Zaenglein cited research showing 39% of female high school students have had sexual relations. “In my opinion, these patients should have emergency contraception prescribed to them as a backup,” she said.

Dr. Zaenglein believes there’s a fair amount of “misunderstanding” about EC, with many people thinking it’s an abortion pill. “It’s a totally different medicine. This is contraception; if you’re pregnant, it’s not going to affect your fetus.”

Outgoing SPD President Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, agreed that Dr. Zaenglein raised an important issue. “She has identified a practice gap and a knowledge gap that we need to address,” she said in an interview.

When discussing contraception with female patients taking isotretinoin, assume they’re sexually active or could be, Dr. Zaenglein told meeting attendees. Be explicit about the risks to the fetus and consider their past compliance.

Complex Disorder

During her presentation, Dr. Zaenglein described acne as a “very complex, multifactorial inflammatory disorder” of the skin. It involves four steps: Increased sebum production, hyperkeratinization, Cutibacterium acnes, and inflammation. External factors such as diet, genes, and the environment play a role.

“But at the heart of all of it is androgens; if you didn’t have androgens, you wouldn’t have acne.” That’s why some acne treatments block androgen receptors.

Clinicians are increasingly using one such therapy, spironolactone, to treat acne in female adolescents. Dr. Zaenglein referred to a Mayo Clinic study of 80 patients (mean age, 19 years), who had moderate to severe acne treated with a mean dose of 100 mg/day, that found 80% had improvement with a favorable side effect profile. This included nearly 23% who had a complete response (90% or more) and 36% who had a partial response (more than 50%); 20% had no response.

However, response rates are higher in adults, said Dr. Zaenglein, noting that spironolactone works “much better” in adult women.

Side effects of spironolactone can include menstrual disturbances, breast enlargement and tenderness, and premenstrual syndrome–like symptoms.

Dermatologists should also consider combined oral contraceptives (COCs) in their adolescent patients with acne. These have an estrogen component as well as a progestin component.

They have proven effectiveness for acne in adolescents, yet a US survey of 170 dermatology residents found only 60% felt comfortable prescribing them to healthy adolescents. The survey also found only 62% of respondents felt adequately trained on the efficacy of COCs, and 42% felt adequately trained on their safety.

Contraindications for COCs include thrombosis, migraine with aura, lupus, seizures, and hypertension. Complex valvular heart disease and liver tumors also need to be ruled out, said Dr. Zaenglein. One of the “newer concerns” with COCs is depression. “There’s biological plausibility because, obviously, hormones impact the brain.”

Preventing Drug Interactions

Before prescribing hormonal therapy, clinicians should carry out an acne assessment, aimed in part at preventing drug interactions. “The one we mostly have to watch out for is rifampin,” an antibiotic that could interact with COCs, said Dr. Zaenglein.

The herbal supplement St John’s Wort can reduce the efficacy of COCs. “You also want to make sure that they’re not on any medicines that will increase potassium, such as ACE inhibitors,” said Dr. Zaenglein. But tetracyclines, ampicillin, or metronidazole are usually “all okay” when combined with COCs.

It’s important to get baseline blood pressure levels and to check these along with weight on a regular basis, she added.

Always Consider PCOS

Before starting hormonal therapy, she advises dermatologists to “always consider” polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a condition that’s “probably much underdiagnosed.” Acne is common in adolescents with PCOS. She suggests using a PCOS checklist, a reminder to ask about irregular periods, hirsutism, signs of insulin resistance such as increased body mass index, a history of premature adrenarche, and a family history of PCOS, said Dr. Zaenglein, noting that a person with a sibling who has PCOS has about a 40% chance of developing the condition.

“We play an important role in getting kids diagnosed at an early age so that we can make interventions because the impact of the metabolic syndrome can have lifelong effects on their cardiovascular system, as well as infertility.”

Dr. Zaenglein is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Acne Guidelines work group, the immediate past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society, a member of the AAD iPLEDGE work group, co–editor in chief of Pediatric Dermatology, an advisory board member of Ortho Dermatologics, and a consultant for Church & Dwight. Dr. Maguiness had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TORONTO —

That was one of the main messages from Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, Penn State University, Hershey, who discussed hormonal therapies for pediatric acne at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Many doctors are reluctant to prescribe EC, which refers to contraceptive methods used to prevent unintended pregnancy after unprotected sexual intercourse or contraceptive failure, whether that’s from discomfort with EC or lack of training, Dr. Zaenglein said in an interview.

Isotretinoin, a retinoid marketed as Accutane and other brand names, is an effective treatment for acne but carries serious teratogenicity risks; the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy is designed to manage this risk and minimize fetal exposure. Yet from 2011 to 2017, 210-310 pregnancies per year were reported to the Food and Drug Administration, according to a 2019 study.

There is a knowledge gap regarding EC among dermatologists who prescribe isotretinoin, which “is perpetuated by the iPLEDGE program because it is inadequate in guiding clinicians or educating patients about the use of EC,” Dr. Zaenglein and colleagues wrote in a recently published viewpoint on EC prescribing in patients on isotretinoin.

Types of EC include oral levonorgestrel (plan B), available over the counter; oral ulipristal acetate (ella), which requires a prescription; and the copper/hormonal intrauterine device.

Not all teens taking isotretinoin can be trusted to be sexually abstinent. Dr. Zaenglein cited research showing 39% of female high school students have had sexual relations. “In my opinion, these patients should have emergency contraception prescribed to them as a backup,” she said.

Dr. Zaenglein believes there’s a fair amount of “misunderstanding” about EC, with many people thinking it’s an abortion pill. “It’s a totally different medicine. This is contraception; if you’re pregnant, it’s not going to affect your fetus.”

Outgoing SPD President Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, agreed that Dr. Zaenglein raised an important issue. “She has identified a practice gap and a knowledge gap that we need to address,” she said in an interview.

When discussing contraception with female patients taking isotretinoin, assume they’re sexually active or could be, Dr. Zaenglein told meeting attendees. Be explicit about the risks to the fetus and consider their past compliance.

Complex Disorder

During her presentation, Dr. Zaenglein described acne as a “very complex, multifactorial inflammatory disorder” of the skin. It involves four steps: Increased sebum production, hyperkeratinization, Cutibacterium acnes, and inflammation. External factors such as diet, genes, and the environment play a role.

“But at the heart of all of it is androgens; if you didn’t have androgens, you wouldn’t have acne.” That’s why some acne treatments block androgen receptors.

Clinicians are increasingly using one such therapy, spironolactone, to treat acne in female adolescents. Dr. Zaenglein referred to a Mayo Clinic study of 80 patients (mean age, 19 years), who had moderate to severe acne treated with a mean dose of 100 mg/day, that found 80% had improvement with a favorable side effect profile. This included nearly 23% who had a complete response (90% or more) and 36% who had a partial response (more than 50%); 20% had no response.

However, response rates are higher in adults, said Dr. Zaenglein, noting that spironolactone works “much better” in adult women.

Side effects of spironolactone can include menstrual disturbances, breast enlargement and tenderness, and premenstrual syndrome–like symptoms.

Dermatologists should also consider combined oral contraceptives (COCs) in their adolescent patients with acne. These have an estrogen component as well as a progestin component.

They have proven effectiveness for acne in adolescents, yet a US survey of 170 dermatology residents found only 60% felt comfortable prescribing them to healthy adolescents. The survey also found only 62% of respondents felt adequately trained on the efficacy of COCs, and 42% felt adequately trained on their safety.

Contraindications for COCs include thrombosis, migraine with aura, lupus, seizures, and hypertension. Complex valvular heart disease and liver tumors also need to be ruled out, said Dr. Zaenglein. One of the “newer concerns” with COCs is depression. “There’s biological plausibility because, obviously, hormones impact the brain.”

Preventing Drug Interactions

Before prescribing hormonal therapy, clinicians should carry out an acne assessment, aimed in part at preventing drug interactions. “The one we mostly have to watch out for is rifampin,” an antibiotic that could interact with COCs, said Dr. Zaenglein.

The herbal supplement St John’s Wort can reduce the efficacy of COCs. “You also want to make sure that they’re not on any medicines that will increase potassium, such as ACE inhibitors,” said Dr. Zaenglein. But tetracyclines, ampicillin, or metronidazole are usually “all okay” when combined with COCs.

It’s important to get baseline blood pressure levels and to check these along with weight on a regular basis, she added.

Always Consider PCOS

Before starting hormonal therapy, she advises dermatologists to “always consider” polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a condition that’s “probably much underdiagnosed.” Acne is common in adolescents with PCOS. She suggests using a PCOS checklist, a reminder to ask about irregular periods, hirsutism, signs of insulin resistance such as increased body mass index, a history of premature adrenarche, and a family history of PCOS, said Dr. Zaenglein, noting that a person with a sibling who has PCOS has about a 40% chance of developing the condition.

“We play an important role in getting kids diagnosed at an early age so that we can make interventions because the impact of the metabolic syndrome can have lifelong effects on their cardiovascular system, as well as infertility.”

Dr. Zaenglein is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Acne Guidelines work group, the immediate past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society, a member of the AAD iPLEDGE work group, co–editor in chief of Pediatric Dermatology, an advisory board member of Ortho Dermatologics, and a consultant for Church & Dwight. Dr. Maguiness had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SPD 2024

Several Skin Conditions More Likely in Children With Obesity

TORONTO — results of new research show.

The retrospective cohort study found markedly higher rates of skin infections, atopic dermatitis (AD), and acanthosis nigricans among children with overweight, compared with children with average weight.

“Many conditions associated with obesity are strong predictors of cardiovascular mortality as these children age, so doctors can play a key role in advocating for weight loss strategies in this population,” lead study author Samantha Epstein, third-year medical student at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, said in an interview. The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Previous research has linked obesity, a chronic inflammatory condition, to psoriasis, AD, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), acne vulgaris, infections, and rosacea in adults. However, there’s scant research exploring the connection between obesity and cutaneous conditions in children.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, childhood obesity is defined as a body mass index, which is weight in kg divided by the square of height in m2, at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex in children aged 2 years or older.

For the study, Ms. Epstein and coauthor Sonal D. Shah, MD, associate professor, Department of Dermatology, Case Western Reserve University, and a board-certified pediatric dermatologist accessed a large national research database and used diagnostic codes to identify over 1 million children (mean age, 8.5 years). Most (about 44%) were White; about one-quarter were Black. The groups were propensity matched, so there were about equal numbers of youngsters with and without obesity and of boys and girls.

They collected data on AD, HS, rosacea, psoriasis, and acanthosis nigricans (a thickened purplish discoloration typically found in body folds around the armpits, groin, and neck). They also gathered information on comorbidities.

Acanthosis nigricans, which is linked to metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance , was more prevalent among children with obesity (20,885 cases in the with-obesity group and 336 in the without-obesity group, for a relative risk [RR] of 62.16 and an odds ratio [OR] of 64.38).

Skin and subcutaneous tissue infections were also more common among those with obesity (14,795 cases) vs 4720 cases among those without obesity (RR, 3.14; OR, 3.2). As for AD, there were 11,892 cases in the with-obesity group and 2983 in the without-obesity group (RR, 3.99; OR, 4.06). There were 1166 cases of psoriasis among those with obesity and 408 among those without obesity (RR, 2.86; OR, 2.88).

HS (587 cases in the with-obesity group and 70 in the without-obesity group; RR, 8.39; OR, 8.39) and rosacea (351 in the with-obesity group and 138 in the without-obesity group; RR, 2.54; OR, 2.55) were the least common skin conditions.

Higher Comorbidity Rates

Compared with their average-weight counterparts, the children with obesity had higher rates of comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes. Ms. Epstein noted that children with diabetes and obesity had increased risks for every skin condition except for infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue when compared with children without obesity.

Such infections were the most common skin conditions among children without obesity. “This was expected just due to the fact that children are outside, they’re playing in the grass and the dirt, and they get infected,” said Ms. Epstein. Still, these infections were three times more common in youngsters with obesity.

Although acanthosis nigricans is “highly correlated” with type 2 diabetes, “not as many children as we would expect in this population have developed type 2 diabetes,” said Ms. Epstein. This might make some sense, though, because these children are still quite young. “When dermatologists recognize this skin condition, they can advocate for weight loss management to try to prevent it.”

Other conditions seen more often in the overweight children with overweight included: hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, polycystic ovarian syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, major depressive disorder, depressive episodes, and anxiety (all P < .001).

Commenting on the results, Sonia Havele, MD, a pediatrician and dermatology resident at Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Missouri, said in an interview that the study reflects trends that she and her colleagues see in clinic: There are more common skin conditions in their patients with obesity.

She agreed that it offers an opening for education. “The results of this study highlight the opportunity we have as pediatric dermatologists to provide additional counseling on obesity and offer referrals to our colleagues in endocrinology, gastroenterology, and nutrition if needed.”

No conflicts of interest were reported.

TORONTO — results of new research show.

The retrospective cohort study found markedly higher rates of skin infections, atopic dermatitis (AD), and acanthosis nigricans among children with overweight, compared with children with average weight.

“Many conditions associated with obesity are strong predictors of cardiovascular mortality as these children age, so doctors can play a key role in advocating for weight loss strategies in this population,” lead study author Samantha Epstein, third-year medical student at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, said in an interview. The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Previous research has linked obesity, a chronic inflammatory condition, to psoriasis, AD, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), acne vulgaris, infections, and rosacea in adults. However, there’s scant research exploring the connection between obesity and cutaneous conditions in children.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, childhood obesity is defined as a body mass index, which is weight in kg divided by the square of height in m2, at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex in children aged 2 years or older.

For the study, Ms. Epstein and coauthor Sonal D. Shah, MD, associate professor, Department of Dermatology, Case Western Reserve University, and a board-certified pediatric dermatologist accessed a large national research database and used diagnostic codes to identify over 1 million children (mean age, 8.5 years). Most (about 44%) were White; about one-quarter were Black. The groups were propensity matched, so there were about equal numbers of youngsters with and without obesity and of boys and girls.

They collected data on AD, HS, rosacea, psoriasis, and acanthosis nigricans (a thickened purplish discoloration typically found in body folds around the armpits, groin, and neck). They also gathered information on comorbidities.

Acanthosis nigricans, which is linked to metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance , was more prevalent among children with obesity (20,885 cases in the with-obesity group and 336 in the without-obesity group, for a relative risk [RR] of 62.16 and an odds ratio [OR] of 64.38).

Skin and subcutaneous tissue infections were also more common among those with obesity (14,795 cases) vs 4720 cases among those without obesity (RR, 3.14; OR, 3.2). As for AD, there were 11,892 cases in the with-obesity group and 2983 in the without-obesity group (RR, 3.99; OR, 4.06). There were 1166 cases of psoriasis among those with obesity and 408 among those without obesity (RR, 2.86; OR, 2.88).

HS (587 cases in the with-obesity group and 70 in the without-obesity group; RR, 8.39; OR, 8.39) and rosacea (351 in the with-obesity group and 138 in the without-obesity group; RR, 2.54; OR, 2.55) were the least common skin conditions.

Higher Comorbidity Rates

Compared with their average-weight counterparts, the children with obesity had higher rates of comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes. Ms. Epstein noted that children with diabetes and obesity had increased risks for every skin condition except for infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue when compared with children without obesity.

Such infections were the most common skin conditions among children without obesity. “This was expected just due to the fact that children are outside, they’re playing in the grass and the dirt, and they get infected,” said Ms. Epstein. Still, these infections were three times more common in youngsters with obesity.

Although acanthosis nigricans is “highly correlated” with type 2 diabetes, “not as many children as we would expect in this population have developed type 2 diabetes,” said Ms. Epstein. This might make some sense, though, because these children are still quite young. “When dermatologists recognize this skin condition, they can advocate for weight loss management to try to prevent it.”

Other conditions seen more often in the overweight children with overweight included: hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, polycystic ovarian syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, major depressive disorder, depressive episodes, and anxiety (all P < .001).

Commenting on the results, Sonia Havele, MD, a pediatrician and dermatology resident at Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Missouri, said in an interview that the study reflects trends that she and her colleagues see in clinic: There are more common skin conditions in their patients with obesity.

She agreed that it offers an opening for education. “The results of this study highlight the opportunity we have as pediatric dermatologists to provide additional counseling on obesity and offer referrals to our colleagues in endocrinology, gastroenterology, and nutrition if needed.”

No conflicts of interest were reported.

TORONTO — results of new research show.

The retrospective cohort study found markedly higher rates of skin infections, atopic dermatitis (AD), and acanthosis nigricans among children with overweight, compared with children with average weight.

“Many conditions associated with obesity are strong predictors of cardiovascular mortality as these children age, so doctors can play a key role in advocating for weight loss strategies in this population,” lead study author Samantha Epstein, third-year medical student at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, said in an interview. The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Previous research has linked obesity, a chronic inflammatory condition, to psoriasis, AD, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), acne vulgaris, infections, and rosacea in adults. However, there’s scant research exploring the connection between obesity and cutaneous conditions in children.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, childhood obesity is defined as a body mass index, which is weight in kg divided by the square of height in m2, at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex in children aged 2 years or older.

For the study, Ms. Epstein and coauthor Sonal D. Shah, MD, associate professor, Department of Dermatology, Case Western Reserve University, and a board-certified pediatric dermatologist accessed a large national research database and used diagnostic codes to identify over 1 million children (mean age, 8.5 years). Most (about 44%) were White; about one-quarter were Black. The groups were propensity matched, so there were about equal numbers of youngsters with and without obesity and of boys and girls.

They collected data on AD, HS, rosacea, psoriasis, and acanthosis nigricans (a thickened purplish discoloration typically found in body folds around the armpits, groin, and neck). They also gathered information on comorbidities.

Acanthosis nigricans, which is linked to metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance , was more prevalent among children with obesity (20,885 cases in the with-obesity group and 336 in the without-obesity group, for a relative risk [RR] of 62.16 and an odds ratio [OR] of 64.38).

Skin and subcutaneous tissue infections were also more common among those with obesity (14,795 cases) vs 4720 cases among those without obesity (RR, 3.14; OR, 3.2). As for AD, there were 11,892 cases in the with-obesity group and 2983 in the without-obesity group (RR, 3.99; OR, 4.06). There were 1166 cases of psoriasis among those with obesity and 408 among those without obesity (RR, 2.86; OR, 2.88).

HS (587 cases in the with-obesity group and 70 in the without-obesity group; RR, 8.39; OR, 8.39) and rosacea (351 in the with-obesity group and 138 in the without-obesity group; RR, 2.54; OR, 2.55) were the least common skin conditions.

Higher Comorbidity Rates

Compared with their average-weight counterparts, the children with obesity had higher rates of comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes. Ms. Epstein noted that children with diabetes and obesity had increased risks for every skin condition except for infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue when compared with children without obesity.

Such infections were the most common skin conditions among children without obesity. “This was expected just due to the fact that children are outside, they’re playing in the grass and the dirt, and they get infected,” said Ms. Epstein. Still, these infections were three times more common in youngsters with obesity.

Although acanthosis nigricans is “highly correlated” with type 2 diabetes, “not as many children as we would expect in this population have developed type 2 diabetes,” said Ms. Epstein. This might make some sense, though, because these children are still quite young. “When dermatologists recognize this skin condition, they can advocate for weight loss management to try to prevent it.”

Other conditions seen more often in the overweight children with overweight included: hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, polycystic ovarian syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, major depressive disorder, depressive episodes, and anxiety (all P < .001).

Commenting on the results, Sonia Havele, MD, a pediatrician and dermatology resident at Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Missouri, said in an interview that the study reflects trends that she and her colleagues see in clinic: There are more common skin conditions in their patients with obesity.

She agreed that it offers an opening for education. “The results of this study highlight the opportunity we have as pediatric dermatologists to provide additional counseling on obesity and offer referrals to our colleagues in endocrinology, gastroenterology, and nutrition if needed.”

No conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM SPD 2024

Topical Ruxolitinib: Analysis Finds Repigmentation Rates in Adolescents with Vitiligo

data showed.

“We consider repigmenting vitiligo a two-step process, where the overactive immune system needs to be calmed down and then the melanocytes need to repopulate to the white areas,” one of the study investigators, David Rosmarin, MD, chair of the Department of Dermatology at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the study results were presented during a poster session. “In younger patients, it may be that the melanocytes are more rapidly repigmenting the patches, which is why we see this effect.”

Ruxolitinib, 1.5% cream (Opzelura) is a Janus kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years of age and older. Dr. Rosmarin and colleagues sought to evaluate differences in rates of complete or near-complete repigmentation and repigmentation by body region between adolescents 12-17 years of age and adults 18 years of age and older who applied ruxolitinib cream twice daily. The researchers evaluated patients who were initially randomized to ruxolitinib cream, 1.5% in the pivotal TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies and applied it for up to 104 weeks. Complete facial improvement was defined as 100% improvement on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI 100) from baseline, and near-total improvement was categorized as a ≥ 75% or ≥ 90% improvement from baseline on the Total body VASI (T-VASI). Responses for each of six body regions, excluding the face, were assessed by the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline on the T-VASI.

Compared with adults, a greater proportion of adolescents achieved F-VASI 100 at week 24 (5.7% [3/53] vs 2.9% [10/341], respectively), but there were no differences between the two groups at week 52 (8.0% [4/50] vs 8.0% [24/300]). Response rates were greater among adolescents vs adults for T-VASI 75 at weeks 24 (13.2% [7/53] vs 5.6% [19/341]) and 52 (22.0% [11/50] vs 20.3% [61/300]), as well as T-VASI 90 at weeks 24 (3.8% [2/53] vs 0.3% [1/341]) and 52 (12.0% [6/50] vs 4.0% [12/300]).

The researchers observed that VASI 50 responses by body region were generally similar between adolescents and adults, but a greater proportion of adolescents achieved a VASI 50 in lower extremities (67.3% [33/49] vs 51.8% [118/228]) and feet (37.5% [12/32] vs 27.9% [51/183]) at week 52.

“Adolescents repigmented more rapidly than adults, so that at 24 weeks, more teens had complete facial repigmentation and T-VASI 75 and T-VASI 90 results,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “With continued use of ruxolitinib cream, both more adults and adolescents achieved greater repigmentation.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was only vehicle controlled up through 24 weeks and that, after week 52, there were fewer patients who completed the long-term extension.

“The take-home message is that ruxolitinib cream can effectively and safely help many patients repigment, including adolescents,” he said.

The study was funded by topical ruxolitinib manufacturer Incyte. Dr. Rosmarin disclosed that he has consulted, spoken for, or conducted trials for AbbVie, Abcuro, Almirall, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena, Astria, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant Sciences, Dermira, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Merck, Nektar, Novartis, Pfizer, RAPT, Regeneron, Recludix Pharma, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Viela Bio, and Zura.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

data showed.

“We consider repigmenting vitiligo a two-step process, where the overactive immune system needs to be calmed down and then the melanocytes need to repopulate to the white areas,” one of the study investigators, David Rosmarin, MD, chair of the Department of Dermatology at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the study results were presented during a poster session. “In younger patients, it may be that the melanocytes are more rapidly repigmenting the patches, which is why we see this effect.”

Ruxolitinib, 1.5% cream (Opzelura) is a Janus kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years of age and older. Dr. Rosmarin and colleagues sought to evaluate differences in rates of complete or near-complete repigmentation and repigmentation by body region between adolescents 12-17 years of age and adults 18 years of age and older who applied ruxolitinib cream twice daily. The researchers evaluated patients who were initially randomized to ruxolitinib cream, 1.5% in the pivotal TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies and applied it for up to 104 weeks. Complete facial improvement was defined as 100% improvement on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI 100) from baseline, and near-total improvement was categorized as a ≥ 75% or ≥ 90% improvement from baseline on the Total body VASI (T-VASI). Responses for each of six body regions, excluding the face, were assessed by the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline on the T-VASI.

Compared with adults, a greater proportion of adolescents achieved F-VASI 100 at week 24 (5.7% [3/53] vs 2.9% [10/341], respectively), but there were no differences between the two groups at week 52 (8.0% [4/50] vs 8.0% [24/300]). Response rates were greater among adolescents vs adults for T-VASI 75 at weeks 24 (13.2% [7/53] vs 5.6% [19/341]) and 52 (22.0% [11/50] vs 20.3% [61/300]), as well as T-VASI 90 at weeks 24 (3.8% [2/53] vs 0.3% [1/341]) and 52 (12.0% [6/50] vs 4.0% [12/300]).

The researchers observed that VASI 50 responses by body region were generally similar between adolescents and adults, but a greater proportion of adolescents achieved a VASI 50 in lower extremities (67.3% [33/49] vs 51.8% [118/228]) and feet (37.5% [12/32] vs 27.9% [51/183]) at week 52.

“Adolescents repigmented more rapidly than adults, so that at 24 weeks, more teens had complete facial repigmentation and T-VASI 75 and T-VASI 90 results,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “With continued use of ruxolitinib cream, both more adults and adolescents achieved greater repigmentation.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was only vehicle controlled up through 24 weeks and that, after week 52, there were fewer patients who completed the long-term extension.

“The take-home message is that ruxolitinib cream can effectively and safely help many patients repigment, including adolescents,” he said.

The study was funded by topical ruxolitinib manufacturer Incyte. Dr. Rosmarin disclosed that he has consulted, spoken for, or conducted trials for AbbVie, Abcuro, Almirall, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena, Astria, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant Sciences, Dermira, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Merck, Nektar, Novartis, Pfizer, RAPT, Regeneron, Recludix Pharma, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Viela Bio, and Zura.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

data showed.

“We consider repigmenting vitiligo a two-step process, where the overactive immune system needs to be calmed down and then the melanocytes need to repopulate to the white areas,” one of the study investigators, David Rosmarin, MD, chair of the Department of Dermatology at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the study results were presented during a poster session. “In younger patients, it may be that the melanocytes are more rapidly repigmenting the patches, which is why we see this effect.”

Ruxolitinib, 1.5% cream (Opzelura) is a Janus kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years of age and older. Dr. Rosmarin and colleagues sought to evaluate differences in rates of complete or near-complete repigmentation and repigmentation by body region between adolescents 12-17 years of age and adults 18 years of age and older who applied ruxolitinib cream twice daily. The researchers evaluated patients who were initially randomized to ruxolitinib cream, 1.5% in the pivotal TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies and applied it for up to 104 weeks. Complete facial improvement was defined as 100% improvement on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI 100) from baseline, and near-total improvement was categorized as a ≥ 75% or ≥ 90% improvement from baseline on the Total body VASI (T-VASI). Responses for each of six body regions, excluding the face, were assessed by the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline on the T-VASI.

Compared with adults, a greater proportion of adolescents achieved F-VASI 100 at week 24 (5.7% [3/53] vs 2.9% [10/341], respectively), but there were no differences between the two groups at week 52 (8.0% [4/50] vs 8.0% [24/300]). Response rates were greater among adolescents vs adults for T-VASI 75 at weeks 24 (13.2% [7/53] vs 5.6% [19/341]) and 52 (22.0% [11/50] vs 20.3% [61/300]), as well as T-VASI 90 at weeks 24 (3.8% [2/53] vs 0.3% [1/341]) and 52 (12.0% [6/50] vs 4.0% [12/300]).

The researchers observed that VASI 50 responses by body region were generally similar between adolescents and adults, but a greater proportion of adolescents achieved a VASI 50 in lower extremities (67.3% [33/49] vs 51.8% [118/228]) and feet (37.5% [12/32] vs 27.9% [51/183]) at week 52.

“Adolescents repigmented more rapidly than adults, so that at 24 weeks, more teens had complete facial repigmentation and T-VASI 75 and T-VASI 90 results,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “With continued use of ruxolitinib cream, both more adults and adolescents achieved greater repigmentation.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was only vehicle controlled up through 24 weeks and that, after week 52, there were fewer patients who completed the long-term extension.

“The take-home message is that ruxolitinib cream can effectively and safely help many patients repigment, including adolescents,” he said.

The study was funded by topical ruxolitinib manufacturer Incyte. Dr. Rosmarin disclosed that he has consulted, spoken for, or conducted trials for AbbVie, Abcuro, Almirall, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena, Astria, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant Sciences, Dermira, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Merck, Nektar, Novartis, Pfizer, RAPT, Regeneron, Recludix Pharma, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Viela Bio, and Zura.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SPD 2024

Mysteries Persist About Tissue Resident Memory T Cells in Psoriasis

SEATTLE — In fact, flare-ups often recur at the same site, a phenomenon that might be driven by these resident memory cells, according to Liv Eidsmo, MD, PhD.

This has led to their use as biomarkers in clinical trials for new therapies, but TRM T cells have a complex biology that is far from fully understood, Dr. Eidsmo said at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. “With time, we’re understanding that the regulation of the functionality is more complicated than we thought, so following these cells as a positive outcome of a clinical trial is a little bit premature,” said Dr. Eidsmo, who is a consultant dermatologist at the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Treatment strategies focus on inhibition of interleukin (IL)-23, which is an activator of TRM T cells and probably keeps them alive, according to Dr. Eidsmo. “The hope is that these cells can be silenced by IL-23 inhibition, which is a great idea, and it probably works. It’s just a matter of what is the readout of long-term remission, because the big challenge in the clinical world is when do we stop these expensive biological treatments? When can we feel secure that patients are in deep remission?” she asked.

TRM cells are also far from the only immune cells involved in psoriasis. Others include keratinocytes, Langerhans cells, and fibroblasts. Dr. Eidsmo referenced a recent spatial analysis that used single-cell and spatial RNA sequencing to identify the localization of specific cell populations and inflammatory pathways within psoriasis lesions and epidermal compartments as well as also suggested crosstalk links between cell types. Epigenetic changes in stem cells may also maintain a lower threshold for tissue inflammation.

Dr. Eidsmo advised caution in eliminating TRM T cells, which play a key role in protecting against melanoma and other cancers, especially later in life. “We don’t want to get rid of them. We want to have the right balance.”

She noted a study in her own lab that mapped TRM T cells in healthy epidermis and found that they could be renewed from both circulating precursors and cells within the epidermis. “So getting rid of the mature TRM T cells will most likely just lead to a new generation of the same subset.”

Other data show that there are a wide range of subsets of TRM T cells, and she recommended focusing on the functionality of TRM T cells rather than sheer numbers. “This is something we’re working on now: Can we change the functionality [of TRM T cells], rather than eradicate them and hope for the best in the next generation? Can we change the functionality of the T cells we already have in the skin?”

There is also epigenetic data in TRM T cells, keratinocytes, stem cells, and other cells thus suggesting complexity and plasticity in the system that remains poorly understood.

Taken together, the research is at too early of a stage to be clinically useful, said Dr. Eidsmo. “We need to go back to the drawing board and just realize what we need to measure, and with the new techniques coming out, maybe spatial [measurement] at a high resolution, we can find biomarkers that better dictate the future of this. Be a little bit wary when you read the outcomes from the clinical trials that are ongoing, because right now, it’s a bit of a race between different biologics. These cells are used as a readout of efficacy of the treatments, and we’re not quite there yet.”

During the Q&A session after the presentation, one audience member asked about the heterogeneity of cells found within the skin of patients with psoriasis and pointed out that many proinflammatory cells likely play a role in tumor control. Dr. Eidsmo responded that her group’s analysis of a large database of patients with metastatic melanoma found that a factor that is important to the development of TRM T cells was strongly correlated to survival in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving immune checkpoint blockade. “So we really don’t want to eradicate them,” she said.

Also during the Q&A, Iain McInnes, MD, PhD, commented about the need to understand the previous events that drove the creation of memory T cells. “For me, the question is about the hierarchy, the primacy of what really drives the memory. In the infectious world, we’re trained to think [that memory responses] are T cell driven memory, but I wonder whether you have an idea of whether the T cell is responding to other memories, particularly in the stroma. Because certainly in the arthropathies, we have really good evidence now of epigenetic change in the synovial stroma and subsets,” said Dr. McInnes, who is director of the Institute of Infection, Immunity, and Inflammation at the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland.

Dr. Eidsmo responded that she believes responses are different among different individuals. “We know too little about how these two systems interact with one another. I think the TRM T cells are very good at amplifying the stroma to recruit cells in. I think we need to think of two-step therapies. You need to normalize this [stromal] environment. How you can do that, I don’t know.”

Dr. McInnes agreed. “As a myeloid doctor, I strongly believe that perpetuators are innate and the adaptive is following on. But how do we test that? That’s really hard,” he said.

Dr. Eidsmo did not list any disclosures. Dr. McInnes has financial relationships with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer, Compugen, Cabaletta, Causeway, Dextera, Eli Lilly, Celgene, MoonLake, Pfizer, Novartis, Janssen, Roche, Versus Arthritis, MRC, and UCB.

SEATTLE — In fact, flare-ups often recur at the same site, a phenomenon that might be driven by these resident memory cells, according to Liv Eidsmo, MD, PhD.

This has led to their use as biomarkers in clinical trials for new therapies, but TRM T cells have a complex biology that is far from fully understood, Dr. Eidsmo said at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. “With time, we’re understanding that the regulation of the functionality is more complicated than we thought, so following these cells as a positive outcome of a clinical trial is a little bit premature,” said Dr. Eidsmo, who is a consultant dermatologist at the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Treatment strategies focus on inhibition of interleukin (IL)-23, which is an activator of TRM T cells and probably keeps them alive, according to Dr. Eidsmo. “The hope is that these cells can be silenced by IL-23 inhibition, which is a great idea, and it probably works. It’s just a matter of what is the readout of long-term remission, because the big challenge in the clinical world is when do we stop these expensive biological treatments? When can we feel secure that patients are in deep remission?” she asked.

TRM cells are also far from the only immune cells involved in psoriasis. Others include keratinocytes, Langerhans cells, and fibroblasts. Dr. Eidsmo referenced a recent spatial analysis that used single-cell and spatial RNA sequencing to identify the localization of specific cell populations and inflammatory pathways within psoriasis lesions and epidermal compartments as well as also suggested crosstalk links between cell types. Epigenetic changes in stem cells may also maintain a lower threshold for tissue inflammation.

Dr. Eidsmo advised caution in eliminating TRM T cells, which play a key role in protecting against melanoma and other cancers, especially later in life. “We don’t want to get rid of them. We want to have the right balance.”

She noted a study in her own lab that mapped TRM T cells in healthy epidermis and found that they could be renewed from both circulating precursors and cells within the epidermis. “So getting rid of the mature TRM T cells will most likely just lead to a new generation of the same subset.”

Other data show that there are a wide range of subsets of TRM T cells, and she recommended focusing on the functionality of TRM T cells rather than sheer numbers. “This is something we’re working on now: Can we change the functionality [of TRM T cells], rather than eradicate them and hope for the best in the next generation? Can we change the functionality of the T cells we already have in the skin?”

There is also epigenetic data in TRM T cells, keratinocytes, stem cells, and other cells thus suggesting complexity and plasticity in the system that remains poorly understood.

Taken together, the research is at too early of a stage to be clinically useful, said Dr. Eidsmo. “We need to go back to the drawing board and just realize what we need to measure, and with the new techniques coming out, maybe spatial [measurement] at a high resolution, we can find biomarkers that better dictate the future of this. Be a little bit wary when you read the outcomes from the clinical trials that are ongoing, because right now, it’s a bit of a race between different biologics. These cells are used as a readout of efficacy of the treatments, and we’re not quite there yet.”

During the Q&A session after the presentation, one audience member asked about the heterogeneity of cells found within the skin of patients with psoriasis and pointed out that many proinflammatory cells likely play a role in tumor control. Dr. Eidsmo responded that her group’s analysis of a large database of patients with metastatic melanoma found that a factor that is important to the development of TRM T cells was strongly correlated to survival in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving immune checkpoint blockade. “So we really don’t want to eradicate them,” she said.

Also during the Q&A, Iain McInnes, MD, PhD, commented about the need to understand the previous events that drove the creation of memory T cells. “For me, the question is about the hierarchy, the primacy of what really drives the memory. In the infectious world, we’re trained to think [that memory responses] are T cell driven memory, but I wonder whether you have an idea of whether the T cell is responding to other memories, particularly in the stroma. Because certainly in the arthropathies, we have really good evidence now of epigenetic change in the synovial stroma and subsets,” said Dr. McInnes, who is director of the Institute of Infection, Immunity, and Inflammation at the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland.

Dr. Eidsmo responded that she believes responses are different among different individuals. “We know too little about how these two systems interact with one another. I think the TRM T cells are very good at amplifying the stroma to recruit cells in. I think we need to think of two-step therapies. You need to normalize this [stromal] environment. How you can do that, I don’t know.”

Dr. McInnes agreed. “As a myeloid doctor, I strongly believe that perpetuators are innate and the adaptive is following on. But how do we test that? That’s really hard,” he said.

Dr. Eidsmo did not list any disclosures. Dr. McInnes has financial relationships with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer, Compugen, Cabaletta, Causeway, Dextera, Eli Lilly, Celgene, MoonLake, Pfizer, Novartis, Janssen, Roche, Versus Arthritis, MRC, and UCB.

SEATTLE — In fact, flare-ups often recur at the same site, a phenomenon that might be driven by these resident memory cells, according to Liv Eidsmo, MD, PhD.

This has led to their use as biomarkers in clinical trials for new therapies, but TRM T cells have a complex biology that is far from fully understood, Dr. Eidsmo said at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. “With time, we’re understanding that the regulation of the functionality is more complicated than we thought, so following these cells as a positive outcome of a clinical trial is a little bit premature,” said Dr. Eidsmo, who is a consultant dermatologist at the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Treatment strategies focus on inhibition of interleukin (IL)-23, which is an activator of TRM T cells and probably keeps them alive, according to Dr. Eidsmo. “The hope is that these cells can be silenced by IL-23 inhibition, which is a great idea, and it probably works. It’s just a matter of what is the readout of long-term remission, because the big challenge in the clinical world is when do we stop these expensive biological treatments? When can we feel secure that patients are in deep remission?” she asked.

TRM cells are also far from the only immune cells involved in psoriasis. Others include keratinocytes, Langerhans cells, and fibroblasts. Dr. Eidsmo referenced a recent spatial analysis that used single-cell and spatial RNA sequencing to identify the localization of specific cell populations and inflammatory pathways within psoriasis lesions and epidermal compartments as well as also suggested crosstalk links between cell types. Epigenetic changes in stem cells may also maintain a lower threshold for tissue inflammation.

Dr. Eidsmo advised caution in eliminating TRM T cells, which play a key role in protecting against melanoma and other cancers, especially later in life. “We don’t want to get rid of them. We want to have the right balance.”

She noted a study in her own lab that mapped TRM T cells in healthy epidermis and found that they could be renewed from both circulating precursors and cells within the epidermis. “So getting rid of the mature TRM T cells will most likely just lead to a new generation of the same subset.”

Other data show that there are a wide range of subsets of TRM T cells, and she recommended focusing on the functionality of TRM T cells rather than sheer numbers. “This is something we’re working on now: Can we change the functionality [of TRM T cells], rather than eradicate them and hope for the best in the next generation? Can we change the functionality of the T cells we already have in the skin?”

There is also epigenetic data in TRM T cells, keratinocytes, stem cells, and other cells thus suggesting complexity and plasticity in the system that remains poorly understood.

Taken together, the research is at too early of a stage to be clinically useful, said Dr. Eidsmo. “We need to go back to the drawing board and just realize what we need to measure, and with the new techniques coming out, maybe spatial [measurement] at a high resolution, we can find biomarkers that better dictate the future of this. Be a little bit wary when you read the outcomes from the clinical trials that are ongoing, because right now, it’s a bit of a race between different biologics. These cells are used as a readout of efficacy of the treatments, and we’re not quite there yet.”

During the Q&A session after the presentation, one audience member asked about the heterogeneity of cells found within the skin of patients with psoriasis and pointed out that many proinflammatory cells likely play a role in tumor control. Dr. Eidsmo responded that her group’s analysis of a large database of patients with metastatic melanoma found that a factor that is important to the development of TRM T cells was strongly correlated to survival in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving immune checkpoint blockade. “So we really don’t want to eradicate them,” she said.

Also during the Q&A, Iain McInnes, MD, PhD, commented about the need to understand the previous events that drove the creation of memory T cells. “For me, the question is about the hierarchy, the primacy of what really drives the memory. In the infectious world, we’re trained to think [that memory responses] are T cell driven memory, but I wonder whether you have an idea of whether the T cell is responding to other memories, particularly in the stroma. Because certainly in the arthropathies, we have really good evidence now of epigenetic change in the synovial stroma and subsets,” said Dr. McInnes, who is director of the Institute of Infection, Immunity, and Inflammation at the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland.

Dr. Eidsmo responded that she believes responses are different among different individuals. “We know too little about how these two systems interact with one another. I think the TRM T cells are very good at amplifying the stroma to recruit cells in. I think we need to think of two-step therapies. You need to normalize this [stromal] environment. How you can do that, I don’t know.”

Dr. McInnes agreed. “As a myeloid doctor, I strongly believe that perpetuators are innate and the adaptive is following on. But how do we test that? That’s really hard,” he said.

Dr. Eidsmo did not list any disclosures. Dr. McInnes has financial relationships with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer, Compugen, Cabaletta, Causeway, Dextera, Eli Lilly, Celgene, MoonLake, Pfizer, Novartis, Janssen, Roche, Versus Arthritis, MRC, and UCB.

FROM GRAPPA 2024

Cyclosporine for Recalcitrant Bullous Pemphigoid Induced by Nivolumab Therapy for Malignant Melanoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of advanced-stage melanoma, with remarkably improved progression-free survival.1 Anti–programmed death receptor 1 (anti–PD-1) therapies, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are a class of checkpoint inhibitors that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for unresectable metastatic melanoma. Anti–PD-1 agents block the interaction of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) found on tumor cells with the PD-1 receptor on T cells, facilitating a positive immune response.2

Although these therapies have demonstrated notable antitumor efficacy, they also give rise to numerous immune-related adverse events (irAEs). As many as 70% of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors experience some type of organ system irAE, of which 30% to 40% are cutaneous.3-6 Dermatologic adverse events are the most common irAEs, specifically spongiotic dermatitis, lichenoid dermatitis, pruritus, and vitiligo.7 Bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune bullous skin disorder caused by autoantibodies to basement membrane zone antigens, is a rare but potentially serious cutaneous irAE.8 Systemic corticosteroids commonly are used to treat immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP; other options include tetracyclines for maintenance therapy and rituximab for corticosteroid-refractory BP associated with anti-PD-1.9 We present a case of recalcitrant BP secondary to nivolumab therapy in a patient with metastatic melanoma who had near-complete resolution of BP following 2 months of cyclosporine.

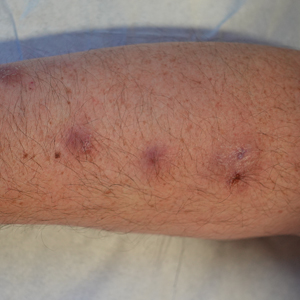

A 41-year-old man presented with a generalized papular skin eruption of 1 month’s duration. He had a history of stage IIIC malignant melanoma of the lower right leg with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy. The largest lymph node deposit was 0.03 mm without extracapsular extension. Whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed no evidence of distant disease. The patient was treated with wide local excision with clear surgical margins plus 12 cycles of nivolumab, which was discontinued due to colitis. Four months after the final cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed widespread erythematous papules with hemorrhagic yellow crusting and no mucosal involvement. He was referred to dermatology by his primary oncologist for further evaluation.

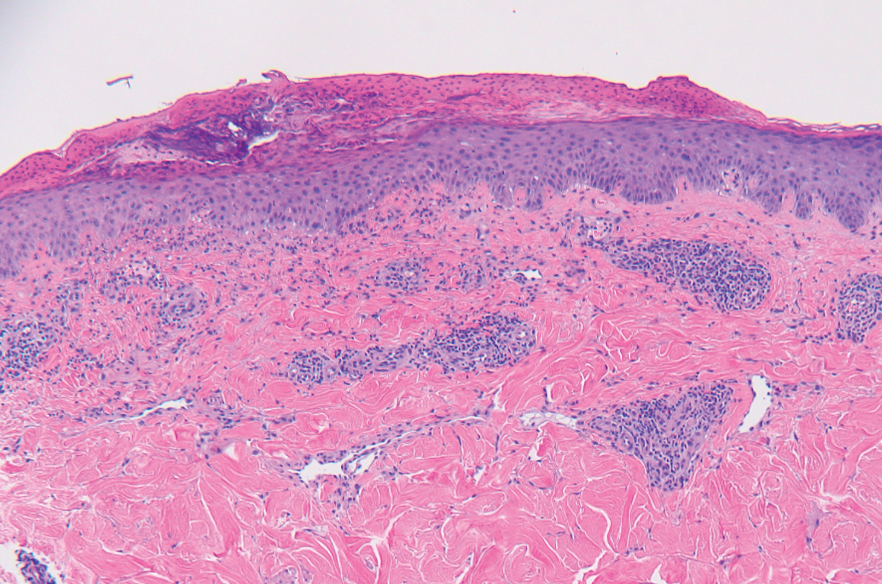

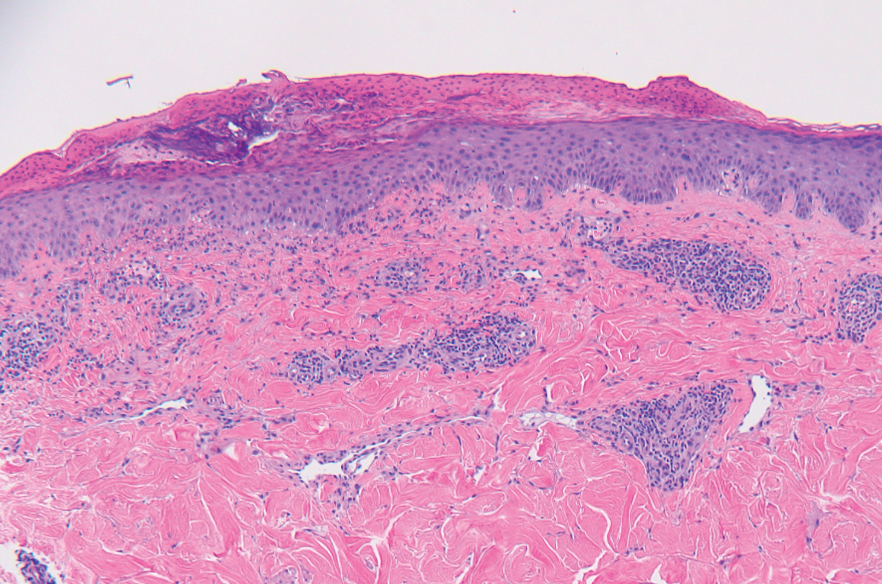

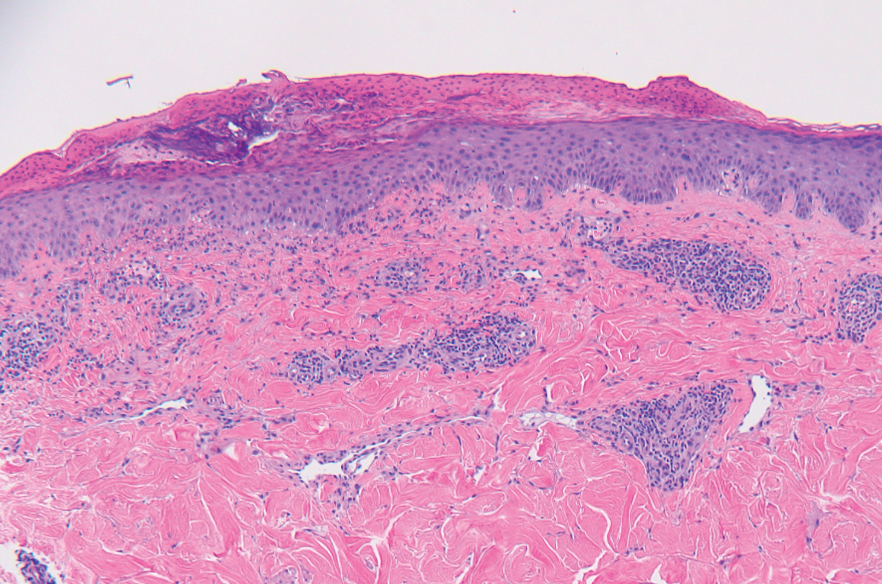

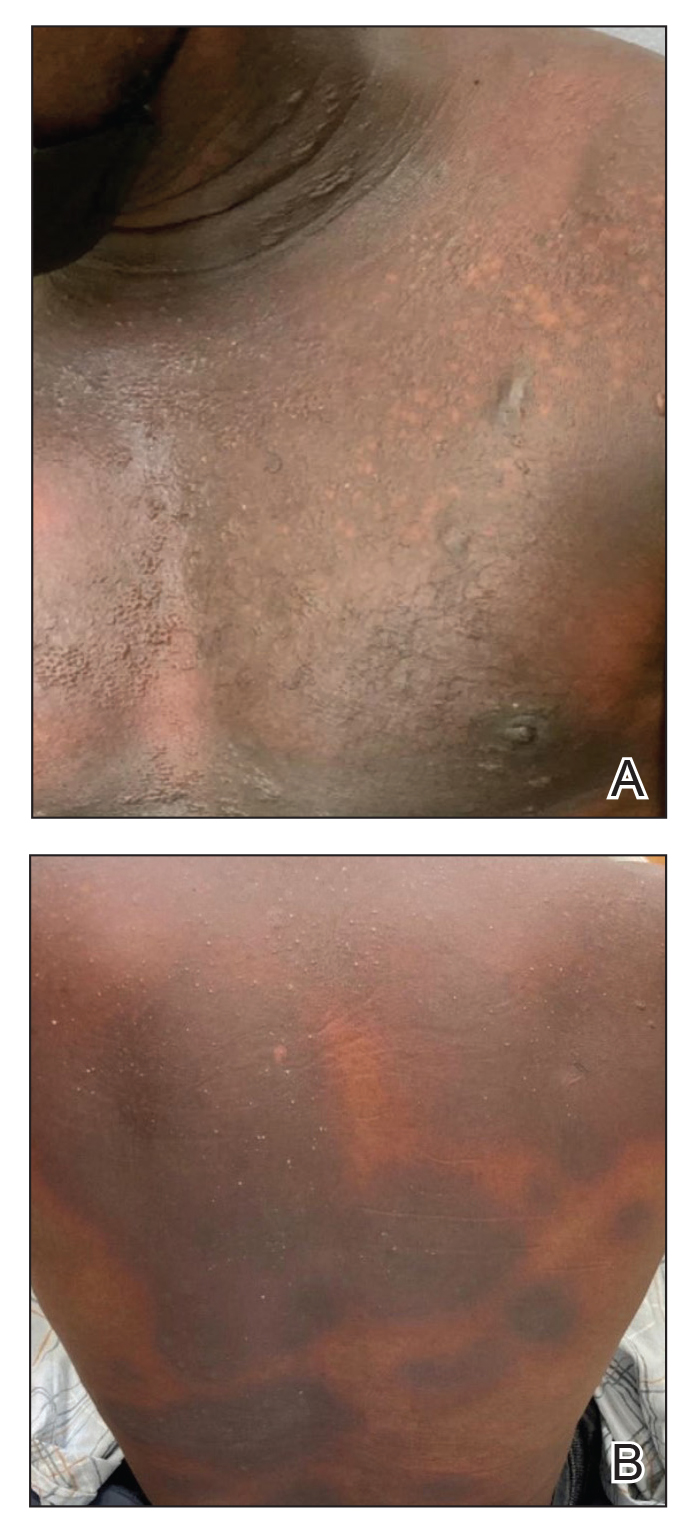

A punch biopsy from the abdomen showed parakeratosis with leukocytoclasis and a superficial dermal infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed linear basement membrane deposits of IgG and C3, consistent with subepidermal blistering disease. Indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated trace IgG and IgG4 antibodies localized to the epidermal roof of salt-split skin and was negative for IgA antibodies. An enzyme-linked immunoassay was positive for BP antigen 2 (BP180) antibodies (98.4 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]) and negative for BP antigen 1 (BP230) antibodies (4.3 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]). Overall, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of BP.

The patient was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily with initial response; however, there was disease recurrence with tapering. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily were added as steroid-sparing agents, as prednisone was discontinued due to mood changes. Three months after the prednisone taper, the patient continued to develop new blisters. He completed treatment with doxycycline and nicotinamide. Rituximab 375 mg weekly was then initiated for 4 weeks.

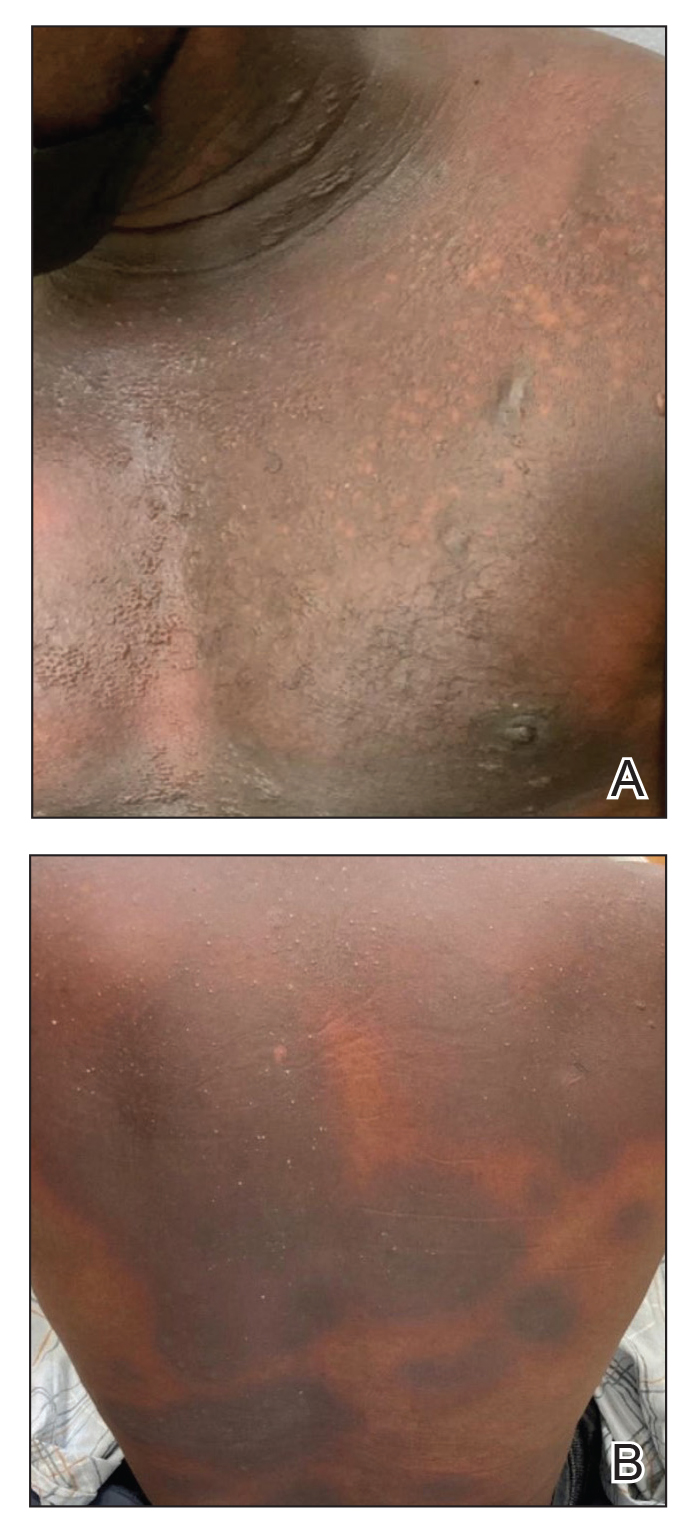

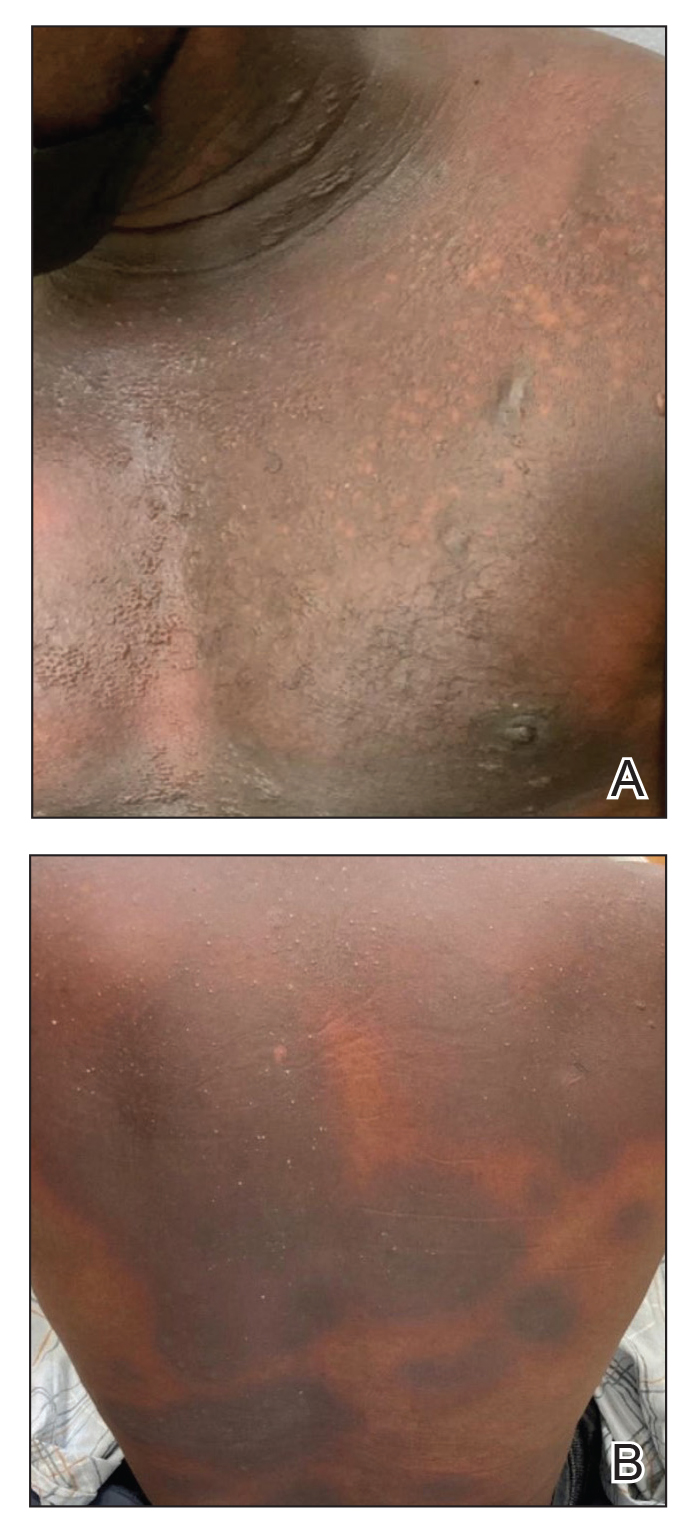

At 2-week follow-up after completing the rituximab course, the patient reported worsening symptoms and presented with new bullae on the abdomen and upper extremities (Figure 2). Because of the recent history of mood changes while taking prednisone, a trial of cyclosporine 100 mg twice daily (1.37 mg/kg/d) was initiated, with notable improvement within 2 weeks of treatment. After 2 months of cyclosporine, approximately 90% of the rash had resolved with a few tense bullae remaining on the left frontal scalp but no new flares (Figure 3). One month after treatment ended, the patient remained clear of lesions without relapse.

Programmed death receptor 1 inhibitors have shown dramatic efficacy for a growing number of solid and hematologic malignancies, especially malignant melanoma. However, their use is accompanied by nonspecific activation of the immune system, resulting in a variety of adverse events, many manifesting on the skin. Several cases of BP in patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been reported.9 Cutaneous irAEs usually manifest within 3 weeks of initiation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy; however, the onset of BP typically occurs later at approximately 21 weeks.4,9 Our patient developed cutaneous manifestations 4 months after cessation of nivolumab.

Bullous pemphigoid classically manifests with pruritus and tense bullae. Notably, our patient’s clinical presentation included a widespread eruption of papules without bullae, which was similar to a review by Tsiogka et al,9 which reported that one-third of patients first present with a nonspecific cutaneous eruption. Bullous pemphigoid induced by anti–PD-1 may manifest differently than traditional BP, illuminating the importance of a thorough diagnostic workup.

Although the pathogenesis of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP has not been fully elucidated, it is hypothesized to be caused by increased T cell cytotoxic activity leading to tumor lysis and release of numerous autoantigens. These autoantigens cause priming of abnormal T cells that can lead to further tissue damage in peripheral tissue and to generation of aberrant B cells and subsequent autoantibodies such as BP180 in germinal centers.4,10,11

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor that reduces synthesis of IL-2, resulting in reduced cell activation.12 Therefore, cyclosporine may alleviate BP in patients who are being treated, or were previously treated, with an immune checkpoint inhibitor by suppressing T cell–mediated immune reaction and may be a rapid alternative for patients who cannot tolerate systemic steroids.

Treatment options for mild to moderate cases of BP include topical corticosteroids and antihistamines, while severe cases may require high-dose systemic corticosteroids. In recalcitrant cases, rituximab infusion with or without intravenous immunoglobulin often is utilized.8,13 The use of cyclosporine for various bullous disorders, including pemphigus vulgaris and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, has been described.14 In recent years there has been a shift away from the use of cyclosporine for these conditions following the introduction of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen on B lymphocytes. We utilized cyclosporine in our patient after he experienced worsening symptoms 1 month after completing treatment with rituximab.

Improvement from rituximab therapy may be delayed because it can take months to deplete CD20+ B lymphocytes from circulation, which may necessitate additional immunosuppressants or re-treatment with rituximab.15,16 In these instances, cyclosporine may be beneficial as a low-cost alternative in patients who are unable to tolerate systemic steroids, with a relatively good safety profile. The dosage of cyclosporine prescribed to the patient was chosen based on Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation management guidelines for psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies, which recommends an initial dosage of 1 to 3 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses.17

As immunotherapy for treating various cancers gains popularity, the frequency of dermatologic irAEs will increase. Therefore, dermatologists must be aware of the array of cutaneous manifestations, such as BP, and potential treatment options. When first-line and second-line therapies are contraindicated or do not provide notable improvement, cyclosporine may be an effective alternative for immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23-34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504030

- Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00561

- Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, et al; . Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:95. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.06

- Kumar V, Chaudhary N, Garg M, et al. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:49. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00049

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Schauer F, Rafei-Shamsabadi D, Mai S, et al. Hemidesmosomal reactivity and treatment recommendations in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced bullous pemphigoid—a retrospective, monocentric study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:953546. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.953546

- Tsiogka A, Bauer JW, Patsatsi A. Bullous pemphigoid associated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00377. doi:10.2340/00015555-3740

- Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, et al. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:664-669. doi:10.1111/ijd.13984

- Yang H, Yao Z, Zhou X, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors: insights into immunological dysregulation. Clin Immunol. 2020;213:108377. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108377

- Russell G, Graveley R, Seid J, et al. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine and effects on connective tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992;21(6 suppl 3):16-22. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(92)90009-3

- Ahmed AR, Shetty S, Kaveri S, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid (BP) with a novel protocol: a retrospective study with a 6-year follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:700-708.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.030

- Amor KT, Ryan C, Menter A. The use of cyclosporine in dermatology: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:925-946. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.063

- Schmidt E, Hunzelmann N, Zillikens D, et al. Rituximab in refractory autoimmune bullous diseases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:503-508. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02151.x

- Kasperkiewicz M, Shimanovich I, Ludwig RJ, et al. Rituximab for treatment-refractory pemphigus and pemphigoid: a case series of 17 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:552-558.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of advanced-stage melanoma, with remarkably improved progression-free survival.1 Anti–programmed death receptor 1 (anti–PD-1) therapies, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are a class of checkpoint inhibitors that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for unresectable metastatic melanoma. Anti–PD-1 agents block the interaction of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) found on tumor cells with the PD-1 receptor on T cells, facilitating a positive immune response.2

Although these therapies have demonstrated notable antitumor efficacy, they also give rise to numerous immune-related adverse events (irAEs). As many as 70% of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors experience some type of organ system irAE, of which 30% to 40% are cutaneous.3-6 Dermatologic adverse events are the most common irAEs, specifically spongiotic dermatitis, lichenoid dermatitis, pruritus, and vitiligo.7 Bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune bullous skin disorder caused by autoantibodies to basement membrane zone antigens, is a rare but potentially serious cutaneous irAE.8 Systemic corticosteroids commonly are used to treat immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP; other options include tetracyclines for maintenance therapy and rituximab for corticosteroid-refractory BP associated with anti-PD-1.9 We present a case of recalcitrant BP secondary to nivolumab therapy in a patient with metastatic melanoma who had near-complete resolution of BP following 2 months of cyclosporine.

A 41-year-old man presented with a generalized papular skin eruption of 1 month’s duration. He had a history of stage IIIC malignant melanoma of the lower right leg with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy. The largest lymph node deposit was 0.03 mm without extracapsular extension. Whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed no evidence of distant disease. The patient was treated with wide local excision with clear surgical margins plus 12 cycles of nivolumab, which was discontinued due to colitis. Four months after the final cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed widespread erythematous papules with hemorrhagic yellow crusting and no mucosal involvement. He was referred to dermatology by his primary oncologist for further evaluation.

A punch biopsy from the abdomen showed parakeratosis with leukocytoclasis and a superficial dermal infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed linear basement membrane deposits of IgG and C3, consistent with subepidermal blistering disease. Indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated trace IgG and IgG4 antibodies localized to the epidermal roof of salt-split skin and was negative for IgA antibodies. An enzyme-linked immunoassay was positive for BP antigen 2 (BP180) antibodies (98.4 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]) and negative for BP antigen 1 (BP230) antibodies (4.3 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]). Overall, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of BP.

The patient was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily with initial response; however, there was disease recurrence with tapering. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily were added as steroid-sparing agents, as prednisone was discontinued due to mood changes. Three months after the prednisone taper, the patient continued to develop new blisters. He completed treatment with doxycycline and nicotinamide. Rituximab 375 mg weekly was then initiated for 4 weeks.

At 2-week follow-up after completing the rituximab course, the patient reported worsening symptoms and presented with new bullae on the abdomen and upper extremities (Figure 2). Because of the recent history of mood changes while taking prednisone, a trial of cyclosporine 100 mg twice daily (1.37 mg/kg/d) was initiated, with notable improvement within 2 weeks of treatment. After 2 months of cyclosporine, approximately 90% of the rash had resolved with a few tense bullae remaining on the left frontal scalp but no new flares (Figure 3). One month after treatment ended, the patient remained clear of lesions without relapse.