User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Anticoagulation no benefit in presumed AFib detected by cardiac devices

AMSTERDAM – Among patients with atrial high-rate episodes detected by implantable devices, anticoagulation with edoxaban did not significantly reduce the incidence of a composite outcome of cardiovascular death, stroke, or systemic embolism in comparison with placebo but was associated with a higher bleeding risk in the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial.

“ They do not need to be anticoagulated. That is a relief,” the lead investigator of the trial, Paulus Kirchhof, MD, University Heart and Vascular Center Hamburg (Germany), said in an interview.

Dr. Kirchhof pointed out that this result was unexpected. “Many of us thought that because atrial high-rate episodes look like AF[ib] when they occur, then they are an indication for anticoagulation. But based on these results from the first-ever randomized trial on this population, there is no need for anticoagulation in these patients.”

Dr. Kirchhof presented the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The study was also simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial recruited patients with implanted devices that enable continuous monitoring of atrial rhythm, such as pacemakers and defibrillators. “Because we can record the rhythm day and night with these devices, they pick up small abnormalities. About 20% of these patients experience these occasional atrial high-rate episodes – short episodes that look like AF[ib], but they are rare and brief,” Dr. Kirchhof noted.

He explained that whether the occurrence of these atrial high-rate episodes in patients without AFib, as documented on a conventional electrocardiogram, justifies the initiation of anticoagulants has been unclear. “But this trial tells us that these episodes are different to AF[ib] that is diagnosed on ECG,” he added.

Another finding in the trial was that among these patients, there was an unexpectedly low rate of stroke, despite the patients’ having a CHADSVASC score of 4.

“Based on the result of this trial, these occasional atrial high-rate episodes do not appear to be associated with stroke. It appears quite benign,” Dr. Kirchhof said.

Implications for wearable technology?

He said the results may also have implications for wearable devices that pick up abnormal heart rhythm, such as smartwatches.

“We don’t know exactly what these wearable technologies are picking up, but most likely it is these atrial high-rate episodes. But we need more research on the value of these wearable technologies; we need randomized trials in this particular patient population before we consider anticoagulation in these patients,” Dr. Kirchhof stated.

The NOAH-AFNET 6 study was an event-driven, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial involving 2,536 patients aged 65 years or older who had atrial high-rate episodes that lasted for at least 6 minutes and who had at least one additional risk factor for stroke.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban or placebo. The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, stroke, or systemic embolism, evaluated in a time-to-event analysis. The safety outcome was a composite of death from any cause or major bleeding.

The mean age of the patients was 78 years, 37.4% were women, and the median duration of atrial high-rate episodes was 2.8 hours. The trial was terminated early, at a median follow-up of 21 months, on the basis of safety concerns and the results of an independent, informal assessment of futility for the efficacy of edoxaban; at termination, the planned enrollment had been completed.

Results showed that a primary efficacy outcome event occurred in 83 patients (3.2% per patient-year) in the edoxaban group and in 101 patients (4.0% per patient-year) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-1.08; P = .15). The incidence of stroke was approximately 1% per patient-year in both groups.

A safety outcome event occurred in 149 patients (5.9% per patient-year) in the edoxaban group and in 114 patients (4.5% per patient-year) in the placebo group (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.02-1.67; P = .03).

ECG-diagnosed AFib developed in 462 of 2,536 patients (18.2% total, 8.7% per patient-year).

In the NEJM article, the authors wrote that the findings of this trial – the low incidence of stroke that was not further reduced by treatment with edoxaban – may make it appropriate to withhold anticoagulant therapy for patients with atrial high-rate episodes.

The main difference between the population studied in this trial and patients with AFib, as documented on an ECG, appears to be the paucity and brevity of atrial arrhythmias in patients with atrial high-rate episodes (termed low arrhythmia burden). Published reports show that a low arrhythmia burden contributes to a low incidence of stroke among patients with AFib, the study authors wrote.

They added that the low rate of stroke in this trial suggests that in addition to clinical risk prediction formulas for stroke, methods to improve the estimation of stroke risk among patients with infrequent atrial arrhythmias detected by long-term monitoring are needed to guide decision-making on the use of anticoagulation.

Commenting on the NOAH-AFNET 6 results, the comoderator of the ESC HOTLINE session at which they were presented, Barbara Casadei, MD, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, said: “Finally we know what to with these patients. Before we just had a variety of opinions with no evidence. I think that the trial really highlights that patients who come to the doctor with symptoms of AF[ib] or who have ECG-documented AF[ib] have a much higher risk of cardioembolic stroke than patients in whom this presumed AF[ib] is picked up incidentally from implanted devices.”

She added: “The stroke rates are very low in this trial, so anticoagulation was never going to work. But this is an important finding. We know that anticoagulants are not a free lunch. There is a significant bleeding risk. These results suggest that unless a patient has clinical AF[ib] that shows up on an ECG then we need to more cautious in prescribing anticoagulation.”

Also commenting on the study, immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology Ed Fry, MD, Ascension Indiana St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, said the management of patients with implanted cardiac devices or personal wearable technology that has picked up an abnormal rhythm suggestive of AFib was a big question in clinical practice.

“These episodes could be AF[ib], which comes with an increased stroke risk, but it could also be something else like atrial tachycardia or supraventricular tachycardia, which do not confer an increased stroke risk,” he explained.

“This study shows that without a firm diagnosis of AF[ib] on an ECG or some sort of continuous AF[ib] monitoring device, we are going to be anticoagulating people who don’t need it. They were exposed to the risk of bleeding without getting the benefit of a reduction in stroke risk,” Dr. Fry noted.

“The important outcome from this trial is that it gives comfort in we can be more confident in withholding anticoagulation until we get a firm diagnosis of AF[ib]. If we have a high index of suspicion that this could be AF[ib], then we can arrange for a further testing,” he added.

Second trial reporting soon

A trial similar to NOAH-AFNET 6 is currently underway – the ARTESIA trial, which is expected to be reported later in 2023.

“We are in close contact with the leadership of that trial, and we hope to do some meta-analysis,” Dr. Kirchhof said. “But I think today we’ve gone from no evidence to one outcome-based trial which shows there is no reason to use anticoagulation in these patients with atrial high-rate episodes. I think this is reason to change practice now, but yes, of course we need to look at the data in totality once the second trial has reported.”

But the lead investigator of the ARTESIA trial, Stuart Connolly, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., does not believe the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial should change practice at this time.

“This trial fails to adequately address the critical issue that drives clinical decision-making in these patients because it is underpowered for the most important endpoint of stroke,” he said in an interview.

“The key question is whether anticoagulation reduces stroke in these patients,” he added. “To answer that, a clinical trial needs to have a lot of strokes, and this trial had very few. The trial was stopped early and had way too few strokes to properly answer this key question.”

The NOAH-AFNET 6 trial was an investigator-initiated trial funded by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Daiichi Sankyo Europe. Dr. Kirchhof reported research support from several drug and device companies active in AFib. He is also listed as an inventor on two patents held by the University of Hamburg on AFib therapy and AFib markers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AMSTERDAM – Among patients with atrial high-rate episodes detected by implantable devices, anticoagulation with edoxaban did not significantly reduce the incidence of a composite outcome of cardiovascular death, stroke, or systemic embolism in comparison with placebo but was associated with a higher bleeding risk in the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial.

“ They do not need to be anticoagulated. That is a relief,” the lead investigator of the trial, Paulus Kirchhof, MD, University Heart and Vascular Center Hamburg (Germany), said in an interview.

Dr. Kirchhof pointed out that this result was unexpected. “Many of us thought that because atrial high-rate episodes look like AF[ib] when they occur, then they are an indication for anticoagulation. But based on these results from the first-ever randomized trial on this population, there is no need for anticoagulation in these patients.”

Dr. Kirchhof presented the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The study was also simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial recruited patients with implanted devices that enable continuous monitoring of atrial rhythm, such as pacemakers and defibrillators. “Because we can record the rhythm day and night with these devices, they pick up small abnormalities. About 20% of these patients experience these occasional atrial high-rate episodes – short episodes that look like AF[ib], but they are rare and brief,” Dr. Kirchhof noted.

He explained that whether the occurrence of these atrial high-rate episodes in patients without AFib, as documented on a conventional electrocardiogram, justifies the initiation of anticoagulants has been unclear. “But this trial tells us that these episodes are different to AF[ib] that is diagnosed on ECG,” he added.

Another finding in the trial was that among these patients, there was an unexpectedly low rate of stroke, despite the patients’ having a CHADSVASC score of 4.

“Based on the result of this trial, these occasional atrial high-rate episodes do not appear to be associated with stroke. It appears quite benign,” Dr. Kirchhof said.

Implications for wearable technology?

He said the results may also have implications for wearable devices that pick up abnormal heart rhythm, such as smartwatches.

“We don’t know exactly what these wearable technologies are picking up, but most likely it is these atrial high-rate episodes. But we need more research on the value of these wearable technologies; we need randomized trials in this particular patient population before we consider anticoagulation in these patients,” Dr. Kirchhof stated.

The NOAH-AFNET 6 study was an event-driven, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial involving 2,536 patients aged 65 years or older who had atrial high-rate episodes that lasted for at least 6 minutes and who had at least one additional risk factor for stroke.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban or placebo. The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, stroke, or systemic embolism, evaluated in a time-to-event analysis. The safety outcome was a composite of death from any cause or major bleeding.

The mean age of the patients was 78 years, 37.4% were women, and the median duration of atrial high-rate episodes was 2.8 hours. The trial was terminated early, at a median follow-up of 21 months, on the basis of safety concerns and the results of an independent, informal assessment of futility for the efficacy of edoxaban; at termination, the planned enrollment had been completed.

Results showed that a primary efficacy outcome event occurred in 83 patients (3.2% per patient-year) in the edoxaban group and in 101 patients (4.0% per patient-year) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-1.08; P = .15). The incidence of stroke was approximately 1% per patient-year in both groups.

A safety outcome event occurred in 149 patients (5.9% per patient-year) in the edoxaban group and in 114 patients (4.5% per patient-year) in the placebo group (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.02-1.67; P = .03).

ECG-diagnosed AFib developed in 462 of 2,536 patients (18.2% total, 8.7% per patient-year).

In the NEJM article, the authors wrote that the findings of this trial – the low incidence of stroke that was not further reduced by treatment with edoxaban – may make it appropriate to withhold anticoagulant therapy for patients with atrial high-rate episodes.

The main difference between the population studied in this trial and patients with AFib, as documented on an ECG, appears to be the paucity and brevity of atrial arrhythmias in patients with atrial high-rate episodes (termed low arrhythmia burden). Published reports show that a low arrhythmia burden contributes to a low incidence of stroke among patients with AFib, the study authors wrote.

They added that the low rate of stroke in this trial suggests that in addition to clinical risk prediction formulas for stroke, methods to improve the estimation of stroke risk among patients with infrequent atrial arrhythmias detected by long-term monitoring are needed to guide decision-making on the use of anticoagulation.

Commenting on the NOAH-AFNET 6 results, the comoderator of the ESC HOTLINE session at which they were presented, Barbara Casadei, MD, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, said: “Finally we know what to with these patients. Before we just had a variety of opinions with no evidence. I think that the trial really highlights that patients who come to the doctor with symptoms of AF[ib] or who have ECG-documented AF[ib] have a much higher risk of cardioembolic stroke than patients in whom this presumed AF[ib] is picked up incidentally from implanted devices.”

She added: “The stroke rates are very low in this trial, so anticoagulation was never going to work. But this is an important finding. We know that anticoagulants are not a free lunch. There is a significant bleeding risk. These results suggest that unless a patient has clinical AF[ib] that shows up on an ECG then we need to more cautious in prescribing anticoagulation.”

Also commenting on the study, immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology Ed Fry, MD, Ascension Indiana St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, said the management of patients with implanted cardiac devices or personal wearable technology that has picked up an abnormal rhythm suggestive of AFib was a big question in clinical practice.

“These episodes could be AF[ib], which comes with an increased stroke risk, but it could also be something else like atrial tachycardia or supraventricular tachycardia, which do not confer an increased stroke risk,” he explained.

“This study shows that without a firm diagnosis of AF[ib] on an ECG or some sort of continuous AF[ib] monitoring device, we are going to be anticoagulating people who don’t need it. They were exposed to the risk of bleeding without getting the benefit of a reduction in stroke risk,” Dr. Fry noted.

“The important outcome from this trial is that it gives comfort in we can be more confident in withholding anticoagulation until we get a firm diagnosis of AF[ib]. If we have a high index of suspicion that this could be AF[ib], then we can arrange for a further testing,” he added.

Second trial reporting soon

A trial similar to NOAH-AFNET 6 is currently underway – the ARTESIA trial, which is expected to be reported later in 2023.

“We are in close contact with the leadership of that trial, and we hope to do some meta-analysis,” Dr. Kirchhof said. “But I think today we’ve gone from no evidence to one outcome-based trial which shows there is no reason to use anticoagulation in these patients with atrial high-rate episodes. I think this is reason to change practice now, but yes, of course we need to look at the data in totality once the second trial has reported.”

But the lead investigator of the ARTESIA trial, Stuart Connolly, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., does not believe the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial should change practice at this time.

“This trial fails to adequately address the critical issue that drives clinical decision-making in these patients because it is underpowered for the most important endpoint of stroke,” he said in an interview.

“The key question is whether anticoagulation reduces stroke in these patients,” he added. “To answer that, a clinical trial needs to have a lot of strokes, and this trial had very few. The trial was stopped early and had way too few strokes to properly answer this key question.”

The NOAH-AFNET 6 trial was an investigator-initiated trial funded by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Daiichi Sankyo Europe. Dr. Kirchhof reported research support from several drug and device companies active in AFib. He is also listed as an inventor on two patents held by the University of Hamburg on AFib therapy and AFib markers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AMSTERDAM – Among patients with atrial high-rate episodes detected by implantable devices, anticoagulation with edoxaban did not significantly reduce the incidence of a composite outcome of cardiovascular death, stroke, or systemic embolism in comparison with placebo but was associated with a higher bleeding risk in the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial.

“ They do not need to be anticoagulated. That is a relief,” the lead investigator of the trial, Paulus Kirchhof, MD, University Heart and Vascular Center Hamburg (Germany), said in an interview.

Dr. Kirchhof pointed out that this result was unexpected. “Many of us thought that because atrial high-rate episodes look like AF[ib] when they occur, then they are an indication for anticoagulation. But based on these results from the first-ever randomized trial on this population, there is no need for anticoagulation in these patients.”

Dr. Kirchhof presented the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The study was also simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial recruited patients with implanted devices that enable continuous monitoring of atrial rhythm, such as pacemakers and defibrillators. “Because we can record the rhythm day and night with these devices, they pick up small abnormalities. About 20% of these patients experience these occasional atrial high-rate episodes – short episodes that look like AF[ib], but they are rare and brief,” Dr. Kirchhof noted.

He explained that whether the occurrence of these atrial high-rate episodes in patients without AFib, as documented on a conventional electrocardiogram, justifies the initiation of anticoagulants has been unclear. “But this trial tells us that these episodes are different to AF[ib] that is diagnosed on ECG,” he added.

Another finding in the trial was that among these patients, there was an unexpectedly low rate of stroke, despite the patients’ having a CHADSVASC score of 4.

“Based on the result of this trial, these occasional atrial high-rate episodes do not appear to be associated with stroke. It appears quite benign,” Dr. Kirchhof said.

Implications for wearable technology?

He said the results may also have implications for wearable devices that pick up abnormal heart rhythm, such as smartwatches.

“We don’t know exactly what these wearable technologies are picking up, but most likely it is these atrial high-rate episodes. But we need more research on the value of these wearable technologies; we need randomized trials in this particular patient population before we consider anticoagulation in these patients,” Dr. Kirchhof stated.

The NOAH-AFNET 6 study was an event-driven, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial involving 2,536 patients aged 65 years or older who had atrial high-rate episodes that lasted for at least 6 minutes and who had at least one additional risk factor for stroke.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban or placebo. The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, stroke, or systemic embolism, evaluated in a time-to-event analysis. The safety outcome was a composite of death from any cause or major bleeding.

The mean age of the patients was 78 years, 37.4% were women, and the median duration of atrial high-rate episodes was 2.8 hours. The trial was terminated early, at a median follow-up of 21 months, on the basis of safety concerns and the results of an independent, informal assessment of futility for the efficacy of edoxaban; at termination, the planned enrollment had been completed.

Results showed that a primary efficacy outcome event occurred in 83 patients (3.2% per patient-year) in the edoxaban group and in 101 patients (4.0% per patient-year) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-1.08; P = .15). The incidence of stroke was approximately 1% per patient-year in both groups.

A safety outcome event occurred in 149 patients (5.9% per patient-year) in the edoxaban group and in 114 patients (4.5% per patient-year) in the placebo group (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.02-1.67; P = .03).

ECG-diagnosed AFib developed in 462 of 2,536 patients (18.2% total, 8.7% per patient-year).

In the NEJM article, the authors wrote that the findings of this trial – the low incidence of stroke that was not further reduced by treatment with edoxaban – may make it appropriate to withhold anticoagulant therapy for patients with atrial high-rate episodes.

The main difference between the population studied in this trial and patients with AFib, as documented on an ECG, appears to be the paucity and brevity of atrial arrhythmias in patients with atrial high-rate episodes (termed low arrhythmia burden). Published reports show that a low arrhythmia burden contributes to a low incidence of stroke among patients with AFib, the study authors wrote.

They added that the low rate of stroke in this trial suggests that in addition to clinical risk prediction formulas for stroke, methods to improve the estimation of stroke risk among patients with infrequent atrial arrhythmias detected by long-term monitoring are needed to guide decision-making on the use of anticoagulation.

Commenting on the NOAH-AFNET 6 results, the comoderator of the ESC HOTLINE session at which they were presented, Barbara Casadei, MD, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, said: “Finally we know what to with these patients. Before we just had a variety of opinions with no evidence. I think that the trial really highlights that patients who come to the doctor with symptoms of AF[ib] or who have ECG-documented AF[ib] have a much higher risk of cardioembolic stroke than patients in whom this presumed AF[ib] is picked up incidentally from implanted devices.”

She added: “The stroke rates are very low in this trial, so anticoagulation was never going to work. But this is an important finding. We know that anticoagulants are not a free lunch. There is a significant bleeding risk. These results suggest that unless a patient has clinical AF[ib] that shows up on an ECG then we need to more cautious in prescribing anticoagulation.”

Also commenting on the study, immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology Ed Fry, MD, Ascension Indiana St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, said the management of patients with implanted cardiac devices or personal wearable technology that has picked up an abnormal rhythm suggestive of AFib was a big question in clinical practice.

“These episodes could be AF[ib], which comes with an increased stroke risk, but it could also be something else like atrial tachycardia or supraventricular tachycardia, which do not confer an increased stroke risk,” he explained.

“This study shows that without a firm diagnosis of AF[ib] on an ECG or some sort of continuous AF[ib] monitoring device, we are going to be anticoagulating people who don’t need it. They were exposed to the risk of bleeding without getting the benefit of a reduction in stroke risk,” Dr. Fry noted.

“The important outcome from this trial is that it gives comfort in we can be more confident in withholding anticoagulation until we get a firm diagnosis of AF[ib]. If we have a high index of suspicion that this could be AF[ib], then we can arrange for a further testing,” he added.

Second trial reporting soon

A trial similar to NOAH-AFNET 6 is currently underway – the ARTESIA trial, which is expected to be reported later in 2023.

“We are in close contact with the leadership of that trial, and we hope to do some meta-analysis,” Dr. Kirchhof said. “But I think today we’ve gone from no evidence to one outcome-based trial which shows there is no reason to use anticoagulation in these patients with atrial high-rate episodes. I think this is reason to change practice now, but yes, of course we need to look at the data in totality once the second trial has reported.”

But the lead investigator of the ARTESIA trial, Stuart Connolly, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., does not believe the NOAH-AFNET 6 trial should change practice at this time.

“This trial fails to adequately address the critical issue that drives clinical decision-making in these patients because it is underpowered for the most important endpoint of stroke,” he said in an interview.

“The key question is whether anticoagulation reduces stroke in these patients,” he added. “To answer that, a clinical trial needs to have a lot of strokes, and this trial had very few. The trial was stopped early and had way too few strokes to properly answer this key question.”

The NOAH-AFNET 6 trial was an investigator-initiated trial funded by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Daiichi Sankyo Europe. Dr. Kirchhof reported research support from several drug and device companies active in AFib. He is also listed as an inventor on two patents held by the University of Hamburg on AFib therapy and AFib markers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2023

Cardiac arrest centers no benefit in OHCA without STEMI

Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) without ST-segment elevation who were transported to the nearest hospital emergency department had outcomes similar to those of patients transported to specialist cardiac arrest centers, in the ARREST trial.

Both groups had the same 30-day survival, the primary outcome, as well as 3-month survival and neurologic outcomes.

senior author Simon R. Redwood, MD, principal investigator of ARREST, from Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Trust Hospitals and King’s College, London, said during a press briefing. “These results may allow better resource allocation elsewhere.”

Importantly, this study excluded patients who clearly had myocardial infarction (MI), he stressed. Cardiac arrest can result from cardiac causes or from other events, including trauma, overdose, drowning, or electrocution, he noted.

On the other hand, patients with MI “will benefit from going straight to a heart attack center and having an attempt at reopening the artery,” he emphasized.

Tiffany Patterson, PhD, clinical lead of ARREST, with the same affiliations as Dr. Redwood, presented the trial findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Amsterdam, on Aug. 27. The study was simultaneously published online in The Lancet.

Observational studies of registry data suggest that postarrest care for patients resuscitated after cardiac arrest, without ST-segment elevation, may be best delivered in a specialized center, she noted.

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation called for a randomized clinical trial of patients resuscitated after cardiac arrest without ST-segment elevation to clarify this.

In the ARREST trial, among 800 patients with return of spontaneous circulation following OHCA without ST-segment elevation who were randomly assigned to be transported to specialized centers or an emergency department, there was no survival benefit, she summarized.

ARREST was “not simply a negative trial, but a new evidence-based starting point,” according to the trial discussant Lia Crotti, MD, PhD, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano and University Milano-Bicocca, Italy.

She drew attention to two findings: First, among the 862 patients who were enrolled, whom paramedics judged as being without an obvious noncardiac cause of the cardiac arrest, “only 60% ended up having a cardiac cause for their cardiac arrest and only around one quarter of the total had coronary artery disease.”

The small number of patients who could have benefited from early access to a catheterization laboratory probably contributed to the negative result obtained in this trial, with the loss of statistical power, she said.

Second, London is a dense urban area with high-quality acute care hospitals, so the standard of care in the nearest emergency department may be not so different from that in cardiac arrest centers, she noted. Furthermore, four of the seven cardiac arrest centers have an emergency department, and some of the standard care patients may have been transported there.

“If the clinical trial would be extended to the entire country, including rural areas, maybe the result would be different,” she said.

The study authors acknowledge that the main limitation of this study was that “it was done across London with a dense population in a small geographic area,” and “the London Ambulance Service has rapid response times and short transit times and delivers high quality prehospital care, which could limit generalizability.”

Asked during the press conference here why the results were so different from the registry study findings, Dr. Redwood said, “We’ve seen time and time again that registry data think they are telling us the answer. They’re actually not.”

The session cochairs, Rudolf de Boer, MD, PhD, of Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and Faiez Zannad, MD, PhD, from University of Lorraine–Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France, each congratulated the researchers on a well-done study.

Dr. de Boer wanted to know whether, for example, 100% of these resuscitated OHCA patients without ST-segment elevation had a cardiac cause, “Would results differ? Or is this just real life?” he asked. Dr. Patterson replied that the paramedics excluded obvious noncardiac causes and the findings were based on current facilities.

“Does this trial provide a definitive answer?” Dr. de Boer asked. Dr. Patterson replied that for the moment, subgroup analysis did not identify any subgroup that might benefit from expedited transport to a cardiac arrest center.

Dr. Zannad wanted to know how informed consent was obtained. Dr. Patterson noted that they have an excellent ethical committee that allowed them to undertake this research in vulnerable patients. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient once the initial emergency had passed if they had regained capacity.

Rationale and trial findings

“It’s very well established that early bystander CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation], early defibrillation, and advanced in-hospital care improves survival,” Dr. Redwood noted. “Despite this, only 1 in 10 survive to leave the hospital.”

Therefore, “a cardiac arrest center has been proposed as a way of improving outcome.” These centers have a catheterization laboratory, open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, advanced critical care including advanced ventilation, temperature management of the patient, hemodynamic support, and neuroprognostication and rehab “because often these patients will have brain injury.

“There’s quite overwhelming registry data to suggest that these cardiac arrest centers improve outcome,” he said, “but these are limited by bias.”

Between January 2018 and December 2022, London Ambulance paramedics randomly assigned 862 patients who were successfully resuscitated and without a confirmed MI to be transported the nearest hospital emergency department or the catheterization laboratory in a cardiac arrest center.

Data were available for 822 participants. They had a mean age of 63 years, and 68% were male.

The primary endpoint, 30-day mortality, occurred in 258 (63%) of 411 participants in the cardiac arrest center group and in 258 (63%) of 412 in the standard care group (unadjusted risk ratio for survival, 1.00; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90-1.11; P = 0.96).

Mortality at 3 months was similar in both groups: 64% in the standard care group and 65% in the cardiac arrest center group.

Neurologic outcomes at discharge and 3 months were similar in both groups.

Eight (2%) of 414 patients in the cardiac arrest center group and three (1%) of 413 in the standard care group had serious adverse events, none of which were deemed related to the trial intervention.

A cardiac cause of arrest was identified in roughly 60% of patients in each group, and of these, roughly 42% were coronary causes, 33% were arrhythmia, and 17% were cardiomyopathy.

The median time from cardiac arrest to hospital arrival was 84 minutes in the cardiac arrest center group and 77 minutes in the standard care group.

“Surprising and important RCT evidence”

In an accompanying editorial, Carolina Malta Hansen, MD, PhD, University of Copenhagen, and colleagues wrote that “this study provides randomized trial evidence that in urban settings such as London, there is no survival advantage of a strategy of transporting patients who have been resuscitated to centres with specialty expertise in care of cardiac arrest.

“This result is surprising and important, since this complex and critically ill population would be expected to benefit from centres with more expertise.”

However, “it would be a mistake to conclude that the trial results apply to regions where local hospitals provide a lower quality of care than those in this trial,” they cautioned.

“Where does this leave the medical community, researchers, and society in general?” they asked rhetorically. “Prioritising a minimum standard of care at local hospitals caring for this population is at least as important as ensuring high-quality care or advanced treatment at tertiary centres.

“This trial also calls for more focus on the basics, including efforts to increase bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and early defibrillation, aspects of care that are currently being assessed in two ongoing clinical trials (NCT04660526 and NCT03835403) and are most strongly associated with improved survival, when coupled with high-quality prehospital care with trained staff and short response times,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by the British Heart Foundation. The authors reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. The financial disclosures of the editorialists are listed with the editorial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) without ST-segment elevation who were transported to the nearest hospital emergency department had outcomes similar to those of patients transported to specialist cardiac arrest centers, in the ARREST trial.

Both groups had the same 30-day survival, the primary outcome, as well as 3-month survival and neurologic outcomes.

senior author Simon R. Redwood, MD, principal investigator of ARREST, from Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Trust Hospitals and King’s College, London, said during a press briefing. “These results may allow better resource allocation elsewhere.”

Importantly, this study excluded patients who clearly had myocardial infarction (MI), he stressed. Cardiac arrest can result from cardiac causes or from other events, including trauma, overdose, drowning, or electrocution, he noted.

On the other hand, patients with MI “will benefit from going straight to a heart attack center and having an attempt at reopening the artery,” he emphasized.

Tiffany Patterson, PhD, clinical lead of ARREST, with the same affiliations as Dr. Redwood, presented the trial findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Amsterdam, on Aug. 27. The study was simultaneously published online in The Lancet.

Observational studies of registry data suggest that postarrest care for patients resuscitated after cardiac arrest, without ST-segment elevation, may be best delivered in a specialized center, she noted.

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation called for a randomized clinical trial of patients resuscitated after cardiac arrest without ST-segment elevation to clarify this.

In the ARREST trial, among 800 patients with return of spontaneous circulation following OHCA without ST-segment elevation who were randomly assigned to be transported to specialized centers or an emergency department, there was no survival benefit, she summarized.

ARREST was “not simply a negative trial, but a new evidence-based starting point,” according to the trial discussant Lia Crotti, MD, PhD, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano and University Milano-Bicocca, Italy.

She drew attention to two findings: First, among the 862 patients who were enrolled, whom paramedics judged as being without an obvious noncardiac cause of the cardiac arrest, “only 60% ended up having a cardiac cause for their cardiac arrest and only around one quarter of the total had coronary artery disease.”

The small number of patients who could have benefited from early access to a catheterization laboratory probably contributed to the negative result obtained in this trial, with the loss of statistical power, she said.

Second, London is a dense urban area with high-quality acute care hospitals, so the standard of care in the nearest emergency department may be not so different from that in cardiac arrest centers, she noted. Furthermore, four of the seven cardiac arrest centers have an emergency department, and some of the standard care patients may have been transported there.

“If the clinical trial would be extended to the entire country, including rural areas, maybe the result would be different,” she said.

The study authors acknowledge that the main limitation of this study was that “it was done across London with a dense population in a small geographic area,” and “the London Ambulance Service has rapid response times and short transit times and delivers high quality prehospital care, which could limit generalizability.”

Asked during the press conference here why the results were so different from the registry study findings, Dr. Redwood said, “We’ve seen time and time again that registry data think they are telling us the answer. They’re actually not.”

The session cochairs, Rudolf de Boer, MD, PhD, of Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and Faiez Zannad, MD, PhD, from University of Lorraine–Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France, each congratulated the researchers on a well-done study.

Dr. de Boer wanted to know whether, for example, 100% of these resuscitated OHCA patients without ST-segment elevation had a cardiac cause, “Would results differ? Or is this just real life?” he asked. Dr. Patterson replied that the paramedics excluded obvious noncardiac causes and the findings were based on current facilities.

“Does this trial provide a definitive answer?” Dr. de Boer asked. Dr. Patterson replied that for the moment, subgroup analysis did not identify any subgroup that might benefit from expedited transport to a cardiac arrest center.

Dr. Zannad wanted to know how informed consent was obtained. Dr. Patterson noted that they have an excellent ethical committee that allowed them to undertake this research in vulnerable patients. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient once the initial emergency had passed if they had regained capacity.

Rationale and trial findings

“It’s very well established that early bystander CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation], early defibrillation, and advanced in-hospital care improves survival,” Dr. Redwood noted. “Despite this, only 1 in 10 survive to leave the hospital.”

Therefore, “a cardiac arrest center has been proposed as a way of improving outcome.” These centers have a catheterization laboratory, open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, advanced critical care including advanced ventilation, temperature management of the patient, hemodynamic support, and neuroprognostication and rehab “because often these patients will have brain injury.

“There’s quite overwhelming registry data to suggest that these cardiac arrest centers improve outcome,” he said, “but these are limited by bias.”

Between January 2018 and December 2022, London Ambulance paramedics randomly assigned 862 patients who were successfully resuscitated and without a confirmed MI to be transported the nearest hospital emergency department or the catheterization laboratory in a cardiac arrest center.

Data were available for 822 participants. They had a mean age of 63 years, and 68% were male.

The primary endpoint, 30-day mortality, occurred in 258 (63%) of 411 participants in the cardiac arrest center group and in 258 (63%) of 412 in the standard care group (unadjusted risk ratio for survival, 1.00; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90-1.11; P = 0.96).

Mortality at 3 months was similar in both groups: 64% in the standard care group and 65% in the cardiac arrest center group.

Neurologic outcomes at discharge and 3 months were similar in both groups.

Eight (2%) of 414 patients in the cardiac arrest center group and three (1%) of 413 in the standard care group had serious adverse events, none of which were deemed related to the trial intervention.

A cardiac cause of arrest was identified in roughly 60% of patients in each group, and of these, roughly 42% were coronary causes, 33% were arrhythmia, and 17% were cardiomyopathy.

The median time from cardiac arrest to hospital arrival was 84 minutes in the cardiac arrest center group and 77 minutes in the standard care group.

“Surprising and important RCT evidence”

In an accompanying editorial, Carolina Malta Hansen, MD, PhD, University of Copenhagen, and colleagues wrote that “this study provides randomized trial evidence that in urban settings such as London, there is no survival advantage of a strategy of transporting patients who have been resuscitated to centres with specialty expertise in care of cardiac arrest.

“This result is surprising and important, since this complex and critically ill population would be expected to benefit from centres with more expertise.”

However, “it would be a mistake to conclude that the trial results apply to regions where local hospitals provide a lower quality of care than those in this trial,” they cautioned.

“Where does this leave the medical community, researchers, and society in general?” they asked rhetorically. “Prioritising a minimum standard of care at local hospitals caring for this population is at least as important as ensuring high-quality care or advanced treatment at tertiary centres.

“This trial also calls for more focus on the basics, including efforts to increase bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and early defibrillation, aspects of care that are currently being assessed in two ongoing clinical trials (NCT04660526 and NCT03835403) and are most strongly associated with improved survival, when coupled with high-quality prehospital care with trained staff and short response times,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by the British Heart Foundation. The authors reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. The financial disclosures of the editorialists are listed with the editorial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) without ST-segment elevation who were transported to the nearest hospital emergency department had outcomes similar to those of patients transported to specialist cardiac arrest centers, in the ARREST trial.

Both groups had the same 30-day survival, the primary outcome, as well as 3-month survival and neurologic outcomes.

senior author Simon R. Redwood, MD, principal investigator of ARREST, from Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Trust Hospitals and King’s College, London, said during a press briefing. “These results may allow better resource allocation elsewhere.”

Importantly, this study excluded patients who clearly had myocardial infarction (MI), he stressed. Cardiac arrest can result from cardiac causes or from other events, including trauma, overdose, drowning, or electrocution, he noted.

On the other hand, patients with MI “will benefit from going straight to a heart attack center and having an attempt at reopening the artery,” he emphasized.

Tiffany Patterson, PhD, clinical lead of ARREST, with the same affiliations as Dr. Redwood, presented the trial findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Amsterdam, on Aug. 27. The study was simultaneously published online in The Lancet.

Observational studies of registry data suggest that postarrest care for patients resuscitated after cardiac arrest, without ST-segment elevation, may be best delivered in a specialized center, she noted.

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation called for a randomized clinical trial of patients resuscitated after cardiac arrest without ST-segment elevation to clarify this.

In the ARREST trial, among 800 patients with return of spontaneous circulation following OHCA without ST-segment elevation who were randomly assigned to be transported to specialized centers or an emergency department, there was no survival benefit, she summarized.

ARREST was “not simply a negative trial, but a new evidence-based starting point,” according to the trial discussant Lia Crotti, MD, PhD, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano and University Milano-Bicocca, Italy.

She drew attention to two findings: First, among the 862 patients who were enrolled, whom paramedics judged as being without an obvious noncardiac cause of the cardiac arrest, “only 60% ended up having a cardiac cause for their cardiac arrest and only around one quarter of the total had coronary artery disease.”

The small number of patients who could have benefited from early access to a catheterization laboratory probably contributed to the negative result obtained in this trial, with the loss of statistical power, she said.

Second, London is a dense urban area with high-quality acute care hospitals, so the standard of care in the nearest emergency department may be not so different from that in cardiac arrest centers, she noted. Furthermore, four of the seven cardiac arrest centers have an emergency department, and some of the standard care patients may have been transported there.

“If the clinical trial would be extended to the entire country, including rural areas, maybe the result would be different,” she said.

The study authors acknowledge that the main limitation of this study was that “it was done across London with a dense population in a small geographic area,” and “the London Ambulance Service has rapid response times and short transit times and delivers high quality prehospital care, which could limit generalizability.”

Asked during the press conference here why the results were so different from the registry study findings, Dr. Redwood said, “We’ve seen time and time again that registry data think they are telling us the answer. They’re actually not.”

The session cochairs, Rudolf de Boer, MD, PhD, of Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and Faiez Zannad, MD, PhD, from University of Lorraine–Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France, each congratulated the researchers on a well-done study.

Dr. de Boer wanted to know whether, for example, 100% of these resuscitated OHCA patients without ST-segment elevation had a cardiac cause, “Would results differ? Or is this just real life?” he asked. Dr. Patterson replied that the paramedics excluded obvious noncardiac causes and the findings were based on current facilities.

“Does this trial provide a definitive answer?” Dr. de Boer asked. Dr. Patterson replied that for the moment, subgroup analysis did not identify any subgroup that might benefit from expedited transport to a cardiac arrest center.

Dr. Zannad wanted to know how informed consent was obtained. Dr. Patterson noted that they have an excellent ethical committee that allowed them to undertake this research in vulnerable patients. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient once the initial emergency had passed if they had regained capacity.

Rationale and trial findings

“It’s very well established that early bystander CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation], early defibrillation, and advanced in-hospital care improves survival,” Dr. Redwood noted. “Despite this, only 1 in 10 survive to leave the hospital.”

Therefore, “a cardiac arrest center has been proposed as a way of improving outcome.” These centers have a catheterization laboratory, open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, advanced critical care including advanced ventilation, temperature management of the patient, hemodynamic support, and neuroprognostication and rehab “because often these patients will have brain injury.

“There’s quite overwhelming registry data to suggest that these cardiac arrest centers improve outcome,” he said, “but these are limited by bias.”

Between January 2018 and December 2022, London Ambulance paramedics randomly assigned 862 patients who were successfully resuscitated and without a confirmed MI to be transported the nearest hospital emergency department or the catheterization laboratory in a cardiac arrest center.

Data were available for 822 participants. They had a mean age of 63 years, and 68% were male.

The primary endpoint, 30-day mortality, occurred in 258 (63%) of 411 participants in the cardiac arrest center group and in 258 (63%) of 412 in the standard care group (unadjusted risk ratio for survival, 1.00; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90-1.11; P = 0.96).

Mortality at 3 months was similar in both groups: 64% in the standard care group and 65% in the cardiac arrest center group.

Neurologic outcomes at discharge and 3 months were similar in both groups.

Eight (2%) of 414 patients in the cardiac arrest center group and three (1%) of 413 in the standard care group had serious adverse events, none of which were deemed related to the trial intervention.

A cardiac cause of arrest was identified in roughly 60% of patients in each group, and of these, roughly 42% were coronary causes, 33% were arrhythmia, and 17% were cardiomyopathy.

The median time from cardiac arrest to hospital arrival was 84 minutes in the cardiac arrest center group and 77 minutes in the standard care group.

“Surprising and important RCT evidence”

In an accompanying editorial, Carolina Malta Hansen, MD, PhD, University of Copenhagen, and colleagues wrote that “this study provides randomized trial evidence that in urban settings such as London, there is no survival advantage of a strategy of transporting patients who have been resuscitated to centres with specialty expertise in care of cardiac arrest.

“This result is surprising and important, since this complex and critically ill population would be expected to benefit from centres with more expertise.”

However, “it would be a mistake to conclude that the trial results apply to regions where local hospitals provide a lower quality of care than those in this trial,” they cautioned.

“Where does this leave the medical community, researchers, and society in general?” they asked rhetorically. “Prioritising a minimum standard of care at local hospitals caring for this population is at least as important as ensuring high-quality care or advanced treatment at tertiary centres.

“This trial also calls for more focus on the basics, including efforts to increase bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and early defibrillation, aspects of care that are currently being assessed in two ongoing clinical trials (NCT04660526 and NCT03835403) and are most strongly associated with improved survival, when coupled with high-quality prehospital care with trained staff and short response times,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by the British Heart Foundation. The authors reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. The financial disclosures of the editorialists are listed with the editorial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2023

No reduction in AFib after noncardiac surgery with colchicine: COP-AF

Trends were seen with reductions in events, but these did not reach significance. However, benefit was seen in a post-hoc analysis looking at a composite of both of those endpoints, the researchers note, as well as a composite of vascular death, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important perioperative AFib, the researchers report.

“We interpret that as there is a trend that is promising, a trend that needs to be further explored,” lead author David Conen, MD, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “We think that further studies are needed to tease out which patients can benefit from colchicine and in what setting it can be used.”

Treatment was safe, with no effect on the risk for sepsis or infection, but it did cause an increase in noninfectious diarrhea. “These events were mostly benign and did not increase length of stay, and only one patient was readmitted because of diarrhea,” Dr. Conen noted.

Results of the COP-AF trial were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, Amsterdam, and published online in The Lancet .

Inflammation and perioperative AFib

AFib and MINS are common complications in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery, Dr. Conen explained. The literature suggests AFib occurs in about 10% and MINS in about 20% of these patients, “and patients with these complications have a much higher risk of additional complications, such as stroke or MI [myocardial infarction],” Dr. Conen said.

Both disorders are associated with high levels of inflammatory biomarkers, so they set out to test colchicine, a well-known anti-inflammatory drug used in higher doses to treat common clinical disorders, such as gout and pericarditis. Small, randomized trials had shown it reduced the incidence of perioperative AFib after cardiac surgery, he noted.

Low-dose colchicine (LoDoCo, Agepha Pharma) was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk for MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, or death in patients with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It was approved on the basis of the LoDoCo 2 trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease and the COLCOT trial in patients with recent MI.

COP-AF was a randomized trial, conducted at 45 sites in 11 countries, and enrolled 3,209 patients aged 55 years or older (51.6% male) undergoing major noncardiac thoracic surgery. Patients were excluded if they had previous AFib, had any contraindications to colchicine, or required colchicine on a clinical basis.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive oral colchicine at a dose of 0.5 mg twice daily (1,608 patients) or placebo (1,601 patients). Treatment was begun within 4 hours before surgery and continued for 10 days. Health care providers and patients, as well as data collectors and adjudicators, were blinded to treatment assignment.

The co-primary outcomes were clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS over 14 days of follow-up. The trial was originally looking only at clinically important AFib, Dr. Conen noted, but after the publication of LoDoCo 2 and COLCOT, “MINS was added as an independent co-primary outcome,” requiring more patients to achieve adequate power.

The main safety outcomes were a composite of sepsis or infection, along with noninfectious diarrhea.

Clinically important AFib was defined as AFib that results in angina, heart failure, or symptomatic hypotension or required treatment with a rate-controlling drug, antiarrhythmic drug, or electrical cardioversion. “This definition was chosen because of its prognostic relevance, and to avoid adding short, asymptomatic AFib episodes of uncertain clinical relevance to the primary outcome,” Dr. Conen said during his presentation.

MINS was defined as an MI or any postoperative troponin elevation that was judged by an adjudication panel to be of ischemic origin.

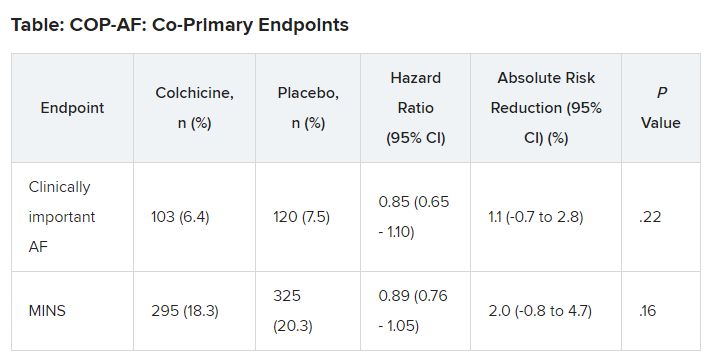

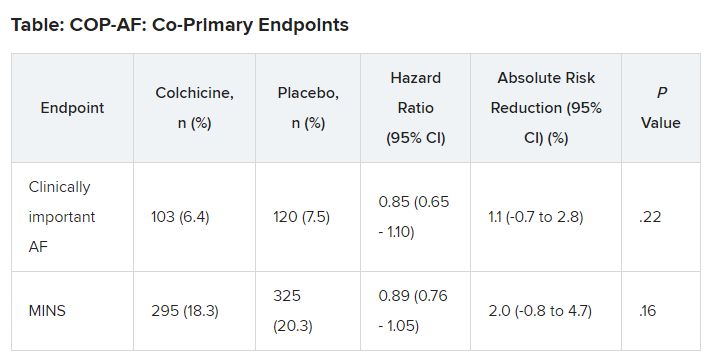

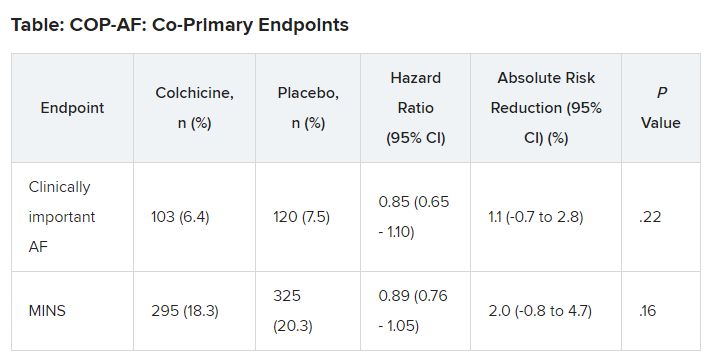

At 14 days, there was no significant difference between groups on either of the co-primary end points.

No significant differences but positive trends were similarly seen in secondary outcomes of a composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MINS, and nonfatal stroke; the composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke; MINS not fulfilling the fourth universal definition of MI; or MI.

There were no differences in time to chest tube removal, days in hospital, nights in the step-down unit, or nights in the intensive care unit.

In terms of safety, there was no difference between groups on sepsis or infection, which occurred in 6.4% of patients in the colchicine group and 5.2% of those in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.66).

Noninfectious diarrhea was more common with colchicine, with 134 events (8.3%) versus 38 with placebo (2.4%), for an HR of 3.64 (95% CI, 2.54-5.22).

“In two post hoc analyses, colchicine significantly reduced the composite of the two co-primary outcomes,” Dr. Conen noted in his presentation. Clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS occurred in 22.4% in the colchicine group and 25.9% in the placebo group (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02).

“Colchicine also significantly reduced the composite of vascular mortality, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important AFib,” he said; 22.6% of patients in the colchicine group had one of these events versus 26.4% of those in the placebo group (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.96; P = .01).

The researchers also reported significant interactions on both co-primary outcomes for the type of incision, “suggesting that stronger and statistically significant effects among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery as opposed to nonthoracoscopic surgery,” Dr. Conen said.

Patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery treated with colchicine had a reduced risk for clinically important AFib (n = 2,397; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.77), but colchicine treatment increased the risk in patients having open surgery (n = 784; HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.07-2.35; P for interaction < .0001).

There was a beneficial effect on MINS with colchicine among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), but no effect was seen among those having open surgery (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.87-1.53; P for interaction = .041).

Low-risk patients

Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, Montreal Heart Institute and Université de Montréal, was the invited discussant for the COP-AF presentation and congratulated the researchers on “a job well done.”

He made the point that the risk for perioperative AFib has decreased substantially with the greater use of thoracoscopic rather than open surgical approaches. The population of this trial was relatively young, with an average age of 68 years; the presence of concomitant CVD was low, at about 9%; by design, patients with previous AFib were excluded; and only about 20% of patients had surgery with an open approach.

“So that population of patients were probably at relatively low risk of atrial fibrillation, and sure enough, the incidence of perioperative AFib in that population at 7.5% was lower than the assumed rate in the statistical powering of the study at 9%,” Dr. Tardif noted.

The post-hoc analyses showed a “nominally significant effect on the composite of MINS and AFib; however, that combination is fairly difficult to justify given the different pathophysiology and clinical consequences of both outcomes,” he pointed out.

The incidence of postoperative MI as a secondary outcome was low, less than 1%, as was the incidence of postoperative stroke in that study, Dr. Tardif added. “Given the link between presence of blood in the pericardium as a trigger for AFib, it would be interesting to know the incidence of perioperative pericarditis in COP-AF.”

In conclusion, he said, “when trying to put these results into the bigger picture of colchicine in cardiovascular disease, I believe we need large, well-powered clinical trials to determine the value of colchicine to reduce the risk of AFib after cardiac surgery and after catheter ablation,” Dr. Tardif said.

“We all know that colchicine represents the first line of therapy for the treatment of acute and recurrent pericarditis, and finally, low-dose colchicine, at a lower dose than was used in COP-AF, 0.5 mg once daily, is the first anti-inflammatory agent approved by both U.S. FDA and Health Canada to reduce the risk of atherothombotic events in patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease], I believe offering a new pillar of treatment for the prevention of ischemic events in such patients.”

Session co-moderator Franz Weidinger, MD, Landstrasse Clinic, Vienna, Austria, called the COP-AF results “very important” but also noted that they show “the challenge of doing well-powered randomized trials these days when we have patients so well treated for a wide array of cardiovascular disease.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); Accelerating Clinical Trials Consortium; Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan for the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario; Population Health Research Institute; Hamilton Health Sciences; Division of Cardiology at McMaster University, Canada; Hanela Foundation, Switzerland; and General Research Fund, Research Grants Council, Hong Kong. Dr. Conen reports receiving research grants from CIHR, speaker fees from Servier outside the current study, and advisory board fees from Roche Diagnostics and Trimedics outside the current study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Trends were seen with reductions in events, but these did not reach significance. However, benefit was seen in a post-hoc analysis looking at a composite of both of those endpoints, the researchers note, as well as a composite of vascular death, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important perioperative AFib, the researchers report.

“We interpret that as there is a trend that is promising, a trend that needs to be further explored,” lead author David Conen, MD, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “We think that further studies are needed to tease out which patients can benefit from colchicine and in what setting it can be used.”

Treatment was safe, with no effect on the risk for sepsis or infection, but it did cause an increase in noninfectious diarrhea. “These events were mostly benign and did not increase length of stay, and only one patient was readmitted because of diarrhea,” Dr. Conen noted.

Results of the COP-AF trial were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, Amsterdam, and published online in The Lancet .

Inflammation and perioperative AFib

AFib and MINS are common complications in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery, Dr. Conen explained. The literature suggests AFib occurs in about 10% and MINS in about 20% of these patients, “and patients with these complications have a much higher risk of additional complications, such as stroke or MI [myocardial infarction],” Dr. Conen said.

Both disorders are associated with high levels of inflammatory biomarkers, so they set out to test colchicine, a well-known anti-inflammatory drug used in higher doses to treat common clinical disorders, such as gout and pericarditis. Small, randomized trials had shown it reduced the incidence of perioperative AFib after cardiac surgery, he noted.

Low-dose colchicine (LoDoCo, Agepha Pharma) was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk for MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, or death in patients with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It was approved on the basis of the LoDoCo 2 trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease and the COLCOT trial in patients with recent MI.

COP-AF was a randomized trial, conducted at 45 sites in 11 countries, and enrolled 3,209 patients aged 55 years or older (51.6% male) undergoing major noncardiac thoracic surgery. Patients were excluded if they had previous AFib, had any contraindications to colchicine, or required colchicine on a clinical basis.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive oral colchicine at a dose of 0.5 mg twice daily (1,608 patients) or placebo (1,601 patients). Treatment was begun within 4 hours before surgery and continued for 10 days. Health care providers and patients, as well as data collectors and adjudicators, were blinded to treatment assignment.

The co-primary outcomes were clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS over 14 days of follow-up. The trial was originally looking only at clinically important AFib, Dr. Conen noted, but after the publication of LoDoCo 2 and COLCOT, “MINS was added as an independent co-primary outcome,” requiring more patients to achieve adequate power.

The main safety outcomes were a composite of sepsis or infection, along with noninfectious diarrhea.

Clinically important AFib was defined as AFib that results in angina, heart failure, or symptomatic hypotension or required treatment with a rate-controlling drug, antiarrhythmic drug, or electrical cardioversion. “This definition was chosen because of its prognostic relevance, and to avoid adding short, asymptomatic AFib episodes of uncertain clinical relevance to the primary outcome,” Dr. Conen said during his presentation.

MINS was defined as an MI or any postoperative troponin elevation that was judged by an adjudication panel to be of ischemic origin.

At 14 days, there was no significant difference between groups on either of the co-primary end points.

No significant differences but positive trends were similarly seen in secondary outcomes of a composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MINS, and nonfatal stroke; the composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke; MINS not fulfilling the fourth universal definition of MI; or MI.

There were no differences in time to chest tube removal, days in hospital, nights in the step-down unit, or nights in the intensive care unit.

In terms of safety, there was no difference between groups on sepsis or infection, which occurred in 6.4% of patients in the colchicine group and 5.2% of those in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.66).

Noninfectious diarrhea was more common with colchicine, with 134 events (8.3%) versus 38 with placebo (2.4%), for an HR of 3.64 (95% CI, 2.54-5.22).

“In two post hoc analyses, colchicine significantly reduced the composite of the two co-primary outcomes,” Dr. Conen noted in his presentation. Clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS occurred in 22.4% in the colchicine group and 25.9% in the placebo group (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02).

“Colchicine also significantly reduced the composite of vascular mortality, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important AFib,” he said; 22.6% of patients in the colchicine group had one of these events versus 26.4% of those in the placebo group (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.96; P = .01).

The researchers also reported significant interactions on both co-primary outcomes for the type of incision, “suggesting that stronger and statistically significant effects among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery as opposed to nonthoracoscopic surgery,” Dr. Conen said.

Patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery treated with colchicine had a reduced risk for clinically important AFib (n = 2,397; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.77), but colchicine treatment increased the risk in patients having open surgery (n = 784; HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.07-2.35; P for interaction < .0001).

There was a beneficial effect on MINS with colchicine among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), but no effect was seen among those having open surgery (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.87-1.53; P for interaction = .041).

Low-risk patients

Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, Montreal Heart Institute and Université de Montréal, was the invited discussant for the COP-AF presentation and congratulated the researchers on “a job well done.”

He made the point that the risk for perioperative AFib has decreased substantially with the greater use of thoracoscopic rather than open surgical approaches. The population of this trial was relatively young, with an average age of 68 years; the presence of concomitant CVD was low, at about 9%; by design, patients with previous AFib were excluded; and only about 20% of patients had surgery with an open approach.

“So that population of patients were probably at relatively low risk of atrial fibrillation, and sure enough, the incidence of perioperative AFib in that population at 7.5% was lower than the assumed rate in the statistical powering of the study at 9%,” Dr. Tardif noted.

The post-hoc analyses showed a “nominally significant effect on the composite of MINS and AFib; however, that combination is fairly difficult to justify given the different pathophysiology and clinical consequences of both outcomes,” he pointed out.

The incidence of postoperative MI as a secondary outcome was low, less than 1%, as was the incidence of postoperative stroke in that study, Dr. Tardif added. “Given the link between presence of blood in the pericardium as a trigger for AFib, it would be interesting to know the incidence of perioperative pericarditis in COP-AF.”

In conclusion, he said, “when trying to put these results into the bigger picture of colchicine in cardiovascular disease, I believe we need large, well-powered clinical trials to determine the value of colchicine to reduce the risk of AFib after cardiac surgery and after catheter ablation,” Dr. Tardif said.

“We all know that colchicine represents the first line of therapy for the treatment of acute and recurrent pericarditis, and finally, low-dose colchicine, at a lower dose than was used in COP-AF, 0.5 mg once daily, is the first anti-inflammatory agent approved by both U.S. FDA and Health Canada to reduce the risk of atherothombotic events in patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease], I believe offering a new pillar of treatment for the prevention of ischemic events in such patients.”

Session co-moderator Franz Weidinger, MD, Landstrasse Clinic, Vienna, Austria, called the COP-AF results “very important” but also noted that they show “the challenge of doing well-powered randomized trials these days when we have patients so well treated for a wide array of cardiovascular disease.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); Accelerating Clinical Trials Consortium; Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan for the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario; Population Health Research Institute; Hamilton Health Sciences; Division of Cardiology at McMaster University, Canada; Hanela Foundation, Switzerland; and General Research Fund, Research Grants Council, Hong Kong. Dr. Conen reports receiving research grants from CIHR, speaker fees from Servier outside the current study, and advisory board fees from Roche Diagnostics and Trimedics outside the current study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Trends were seen with reductions in events, but these did not reach significance. However, benefit was seen in a post-hoc analysis looking at a composite of both of those endpoints, the researchers note, as well as a composite of vascular death, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important perioperative AFib, the researchers report.

“We interpret that as there is a trend that is promising, a trend that needs to be further explored,” lead author David Conen, MD, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “We think that further studies are needed to tease out which patients can benefit from colchicine and in what setting it can be used.”

Treatment was safe, with no effect on the risk for sepsis or infection, but it did cause an increase in noninfectious diarrhea. “These events were mostly benign and did not increase length of stay, and only one patient was readmitted because of diarrhea,” Dr. Conen noted.

Results of the COP-AF trial were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, Amsterdam, and published online in The Lancet .

Inflammation and perioperative AFib

AFib and MINS are common complications in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery, Dr. Conen explained. The literature suggests AFib occurs in about 10% and MINS in about 20% of these patients, “and patients with these complications have a much higher risk of additional complications, such as stroke or MI [myocardial infarction],” Dr. Conen said.

Both disorders are associated with high levels of inflammatory biomarkers, so they set out to test colchicine, a well-known anti-inflammatory drug used in higher doses to treat common clinical disorders, such as gout and pericarditis. Small, randomized trials had shown it reduced the incidence of perioperative AFib after cardiac surgery, he noted.

Low-dose colchicine (LoDoCo, Agepha Pharma) was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk for MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, or death in patients with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It was approved on the basis of the LoDoCo 2 trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease and the COLCOT trial in patients with recent MI.

COP-AF was a randomized trial, conducted at 45 sites in 11 countries, and enrolled 3,209 patients aged 55 years or older (51.6% male) undergoing major noncardiac thoracic surgery. Patients were excluded if they had previous AFib, had any contraindications to colchicine, or required colchicine on a clinical basis.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive oral colchicine at a dose of 0.5 mg twice daily (1,608 patients) or placebo (1,601 patients). Treatment was begun within 4 hours before surgery and continued for 10 days. Health care providers and patients, as well as data collectors and adjudicators, were blinded to treatment assignment.

The co-primary outcomes were clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS over 14 days of follow-up. The trial was originally looking only at clinically important AFib, Dr. Conen noted, but after the publication of LoDoCo 2 and COLCOT, “MINS was added as an independent co-primary outcome,” requiring more patients to achieve adequate power.

The main safety outcomes were a composite of sepsis or infection, along with noninfectious diarrhea.

Clinically important AFib was defined as AFib that results in angina, heart failure, or symptomatic hypotension or required treatment with a rate-controlling drug, antiarrhythmic drug, or electrical cardioversion. “This definition was chosen because of its prognostic relevance, and to avoid adding short, asymptomatic AFib episodes of uncertain clinical relevance to the primary outcome,” Dr. Conen said during his presentation.

MINS was defined as an MI or any postoperative troponin elevation that was judged by an adjudication panel to be of ischemic origin.

At 14 days, there was no significant difference between groups on either of the co-primary end points.

No significant differences but positive trends were similarly seen in secondary outcomes of a composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MINS, and nonfatal stroke; the composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke; MINS not fulfilling the fourth universal definition of MI; or MI.

There were no differences in time to chest tube removal, days in hospital, nights in the step-down unit, or nights in the intensive care unit.

In terms of safety, there was no difference between groups on sepsis or infection, which occurred in 6.4% of patients in the colchicine group and 5.2% of those in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.66).

Noninfectious diarrhea was more common with colchicine, with 134 events (8.3%) versus 38 with placebo (2.4%), for an HR of 3.64 (95% CI, 2.54-5.22).