User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

Climate change: Dermatologists address impact on health, and mobilize to increase awareness

Climate change will increasingly affect the distribution and frequency of insect-borne diseases, cutaneous leishmaniasis, skin cancer, fungal diseases, and a host of other illnesses that have cutaneous manifestations or involve the skin – and dermatologists are being urged to be ready to diagnose clinical findings, counsel patients about risk mitigation, and decrease the carbon footprint of their practices and medical organizations.

“Climate change is not a far-off threat but an urgent health issue,” Misha Rosenbach, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in an editorial with coauthor Mary Sun, a student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. It was first published online in the British Journal of Dermatology last year, titled, “The climate emergency: Why should dermatologists care and how can they act?”.

. Some of the 150-plus members of the ERG have been writing about the dermatologic impacts of climate change – including content that filled the January issue of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology – and speaking about the issues.

A session at the AAD’s virtual annual meeting in April will address climate change and dermatology – the second such session at an annual meeting – and the first two of three planned virtual symposia led by Dr. Rosenbach and his colleagues, have been hosted by the Association of Professors of Dermatology. The ERG encouraged the AAD’s adoption of a position statement in 2018 about climate change and dermatology and its membership in the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health.

“There’s been a lot of conversation in the medical community about the health effects of climate change, but most people leave out the skin,” said Mary L. Williams, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who is a cofounder and coleader with Dr. Rosenbach of the climate change ERG.

“That’s interesting because the skin is the most environmental of all our organs. Of course it will be impacted by all that’s going on,” she said. “We want to bring the dermatologic community and the wider medical community along with us [in appreciating and acting on this knowledge].”

Changing disease patterns

Dr. Rosenbach did not think much about how climate change could affect his patients and his clinical practice until he saw a severe case of hand, foot, and mouth disease in a hospitalized adult in Philadelphia about 10 years ago.

A presentation of the case at an infectious disease conference spurred discussion of how the preceding winters had been warmer and of correlations reported by researchers in China between the incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease – historically a mild infection in children – and average temperature and other meteorological factors. “I knew about climate change, but I never knew we’d see different diseases in our clinical practice, or old diseases affecting new hosts,” Dr. Rosenbach said in an interview.

He pored over the literature to deepen his understanding of climate change science and the impact of climate change on medicine, and found an “emerging focus” on climate change in some medical journals, but “very little in dermatology.” In collaboration with Benjamin Kaffenberger, MD, a dermatologist at The Ohio State University, and colleagues, including an entomologist, Dr. Rosenbach wrote a review of publications relating to climate change and skin disease in North America.

Published in 2017 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the review details how bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites are responding to changing weather patterns in North America, and why dermatologists should be able to recognize changing patterns of disease. Globalization plays a role in changing disease and vector patterns, but “climate change allows expansion of the natural range of pathogens, hosts, reservoirs, and vectors that allow diseases to appear in immunologically naive populations,” they wrote.

Patterns of infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations are already changing. The geographic range of coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, for instance, “has basically doubled in the Southwest U.S., extending up the entire West Coast,” Dr. Rosenbach said, as the result of longer dry seasons and more frequent wind storms that aerosolize the mycosis-causing, soil-dwelling fungal spores.

Lyme disease and associated tick-borne infections continue to expand northward as Ixodes tick vectors move and breed “exactly in sync with a warming world,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “We’re seeing Lyme in Philadelphia in February, whereas in the past we may not have seen it until May ... There are derms in Maine [whose patients have Lyme disease] who may never have seen a case before, and derms in Canada who are making diagnoses of Lyme [for the first time].”

And locally acquired cases of dengue are being reported in Hawaii, Texas, and Florida – and even North Carolina, according to a review of infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations in the issue of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology dedicated to climate change. As with Ixodes ticks, which transmit Lyme disease, rising temperatures lead to longer breeding seasons for Aedes mosquitoes, which transmit dengue. Increased endemicity of dengue is concerning because severe illness is significantly more likely in individuals previously infected with a different serotype.

“Dermatologists should be ready to identify and diagnose these mosquito-borne diseases that we think of as occurring in Central America or tropical regions,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “In my children’s lifetime there will be tropical diseases in New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other such places.”

In his articles and talks, Dr. Rosenbach lays out the science of climate change – for instance, the change in average global temperatures above preindustrial levels (an approximate 1° C rise) , the threshold beyond which the Earth will become less hospitable (1.5° C of warming according to United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the current projections for future warming (an increase of about 3° Celsius by 2100), and the “gold-standard” level of scientific certainty that climate change is human-caused.

Mathematical climate modeling, he emphasized in the interview, can accurately project changes in infection rates. Researchers predicted 10 years ago in a published paper, for instance, that based on global warming patterns, the sand fly vector responsible for cutaneous leishmaniasis would live in the Southern United States and cause endemic infections within 10 years.

And in 2018, Dr. Rosenbach said, a paper in JAMA Dermatology described how more than half – 59% – of the cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed in Texas were endemic, all occurring in people with no prior travel outside the United States.

Dr. Williams’ devotion to climate change and dermatology and to the climate change ERG was inspired in large part by Dr. Rosenbach’s 2017 paper in JAAD. She had long been concerned about climate change, she said, but “the review article was really the impetus for me to think, this is really within my specialty.”

Extreme weather events, and the climate-driven migration expected to increasingly occur, have clear relevance to dermatology, Dr. Williams said. “Often, the most vexing problems that people have when they’re forced out of their homes ... are dermatologic,” she said, like infections from contaminated waters after flooding and the spread of scabies and other communicable diseases due to crowding and unsanitary conditions.

But there are other less obvious ramifications of a changing climate that affect dermatology. Dr. Williams has delved into the literature on heat-related illness, for instance, and found that most research has been in the realm of sports medicine and military health. “Most of us don’t treat serious heat-related illnesses, but our skin is responsible for keeping us cool and there’s an important role for dermatologists to play in knowing how the skin does that and who is at risk for heat illness because the skin is unable to do the full job,” she said.

Research is needed to identify which medications can interfere with the skin’s thermoregulatory responses and put patients at risk, she noted. “And a lot of the work on sweat gland physiology is probably 30 years old now. We should bring to bear contemporary research techniques.”

Dermatology is also “in the early stages of understanding the role that air pollution plays in skin disease,” Dr. Williams said. “Most of the medical literature focuses on the effects of pollution on the lungs and in cardiovascular disease.”

There is evidence linking small particulate matter found in wood smoke and other air pollutants to exacerbations of atopic dermatitis and other inflammatory skin conditions, she noted, but mechanisms need to be explored and health disparities examined. “While we know that there are health disparities in terms of [exposure to] pollution and respiratory illness, we have no idea if this is the case with our skin diseases like atopic dermatitis,” said Dr. Williams.

In general, according to the AAD position statement, low-income and minority communities, in addition to the very young and the very old, “are and will continue to be disproportionately affected by climate change.”

Education and the carbon footprint

Viewing climate change as a social determinant of health (SDH ) – and integrating it into medical training as such – is a topic of active discussion. At UCSF, Sarah J. Coates, MD, a fellow in pediatric dermatology, is working with colleagues to integrate climate change into formal resident education. “We know that climate change affects housing, food security, migration ... and certain populations are and will be especially vulnerable,” she said in an interview. “The effects of climate change fit squarely into the social determinant of health curriculum that we’re building here.”

Dr. Coates began to appreciate the link between climate and infectious diseases – a topic she now writes and speaks about – when she saw several patients with coccidioidomycosis as a dermatology resident at UCSF and learned that the cases represented an epidemic in the Central Valley “resulting from several years of drought.”

Her medical school and residency training were otherwise devoid of any discussion of climate change. At UCSF and nearby Stanford (Calif.) University, this is no longer the case, she and Dr. Williams said. “The medical students here have been quite active and are requesting education,” noted Dr. Williams. “The desire to know more is coming from the bottom.”

Mary E. Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, sees the same interest from physicians-in-training in the Boston area. They want education about climate science, the impact of climate changes on health and risk mitigation, and ways to reduce medicine’s carbon footprint. “We need to teach them and charge them to lead in their communities,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Maloney joined the AAD’s climate change resource group soon after its inception, having realized the urgency of climate change and feeling that she needed “to get passionate and not just do small things.” As a Mohs surgeon, she expects an “explosion” of skin cancer as temperatures and sun exposure continue to increase.

She urges dermatologists to work to decrease the carbon footprint of their practices and to advocate for local hospitals and other clinical institutions to do so. On the AAD website, members now have free access to tools provided by the nonprofit organization My Green Doctor for outpatient offices to lighten their carbon footprints in a cost-effective – or even cost-saving – manner.

Dr. Maloney’s institution has moved to automated lighting systems and the use of LED lights, she said, and has encouraged ride sharing (prior to the pandemic) and computer switch-offs at night. And in her practice, she and a colleague have been working to reduce the purchasing and use of disposable plastics.

Educating patients about the effects of climate change on the health of their skin is another of the missions listed in the AAD’s position statement, and it’s something that Dr. Coates is currently researching. “It seems similar to talking about other social determinants of health,” she said. “Saying to a patient, for instance, ‘we’ve had some really terrible wildfires lately. They’re getting worse as the seasons go on and we know that’s because of climate change. How do you think your current rash relates to the current air quality? How you think the air quality affects your skin?’ ”

Dr. Rosenbach emphasizes that physicians are a broadly trusted group. “I’d tell a patient, ‘you’re the fourth patient I’ve seen with Lyme – we think that’s because it’s been a warmer year due to climate change,’” he said. “I don’t think that bringing up climate change has ever been a source of friction.”

Climate change will increasingly affect the distribution and frequency of insect-borne diseases, cutaneous leishmaniasis, skin cancer, fungal diseases, and a host of other illnesses that have cutaneous manifestations or involve the skin – and dermatologists are being urged to be ready to diagnose clinical findings, counsel patients about risk mitigation, and decrease the carbon footprint of their practices and medical organizations.

“Climate change is not a far-off threat but an urgent health issue,” Misha Rosenbach, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in an editorial with coauthor Mary Sun, a student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. It was first published online in the British Journal of Dermatology last year, titled, “The climate emergency: Why should dermatologists care and how can they act?”.

. Some of the 150-plus members of the ERG have been writing about the dermatologic impacts of climate change – including content that filled the January issue of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology – and speaking about the issues.

A session at the AAD’s virtual annual meeting in April will address climate change and dermatology – the second such session at an annual meeting – and the first two of three planned virtual symposia led by Dr. Rosenbach and his colleagues, have been hosted by the Association of Professors of Dermatology. The ERG encouraged the AAD’s adoption of a position statement in 2018 about climate change and dermatology and its membership in the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health.

“There’s been a lot of conversation in the medical community about the health effects of climate change, but most people leave out the skin,” said Mary L. Williams, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who is a cofounder and coleader with Dr. Rosenbach of the climate change ERG.

“That’s interesting because the skin is the most environmental of all our organs. Of course it will be impacted by all that’s going on,” she said. “We want to bring the dermatologic community and the wider medical community along with us [in appreciating and acting on this knowledge].”

Changing disease patterns

Dr. Rosenbach did not think much about how climate change could affect his patients and his clinical practice until he saw a severe case of hand, foot, and mouth disease in a hospitalized adult in Philadelphia about 10 years ago.

A presentation of the case at an infectious disease conference spurred discussion of how the preceding winters had been warmer and of correlations reported by researchers in China between the incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease – historically a mild infection in children – and average temperature and other meteorological factors. “I knew about climate change, but I never knew we’d see different diseases in our clinical practice, or old diseases affecting new hosts,” Dr. Rosenbach said in an interview.

He pored over the literature to deepen his understanding of climate change science and the impact of climate change on medicine, and found an “emerging focus” on climate change in some medical journals, but “very little in dermatology.” In collaboration with Benjamin Kaffenberger, MD, a dermatologist at The Ohio State University, and colleagues, including an entomologist, Dr. Rosenbach wrote a review of publications relating to climate change and skin disease in North America.

Published in 2017 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the review details how bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites are responding to changing weather patterns in North America, and why dermatologists should be able to recognize changing patterns of disease. Globalization plays a role in changing disease and vector patterns, but “climate change allows expansion of the natural range of pathogens, hosts, reservoirs, and vectors that allow diseases to appear in immunologically naive populations,” they wrote.

Patterns of infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations are already changing. The geographic range of coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, for instance, “has basically doubled in the Southwest U.S., extending up the entire West Coast,” Dr. Rosenbach said, as the result of longer dry seasons and more frequent wind storms that aerosolize the mycosis-causing, soil-dwelling fungal spores.

Lyme disease and associated tick-borne infections continue to expand northward as Ixodes tick vectors move and breed “exactly in sync with a warming world,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “We’re seeing Lyme in Philadelphia in February, whereas in the past we may not have seen it until May ... There are derms in Maine [whose patients have Lyme disease] who may never have seen a case before, and derms in Canada who are making diagnoses of Lyme [for the first time].”

And locally acquired cases of dengue are being reported in Hawaii, Texas, and Florida – and even North Carolina, according to a review of infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations in the issue of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology dedicated to climate change. As with Ixodes ticks, which transmit Lyme disease, rising temperatures lead to longer breeding seasons for Aedes mosquitoes, which transmit dengue. Increased endemicity of dengue is concerning because severe illness is significantly more likely in individuals previously infected with a different serotype.

“Dermatologists should be ready to identify and diagnose these mosquito-borne diseases that we think of as occurring in Central America or tropical regions,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “In my children’s lifetime there will be tropical diseases in New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other such places.”

In his articles and talks, Dr. Rosenbach lays out the science of climate change – for instance, the change in average global temperatures above preindustrial levels (an approximate 1° C rise) , the threshold beyond which the Earth will become less hospitable (1.5° C of warming according to United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the current projections for future warming (an increase of about 3° Celsius by 2100), and the “gold-standard” level of scientific certainty that climate change is human-caused.

Mathematical climate modeling, he emphasized in the interview, can accurately project changes in infection rates. Researchers predicted 10 years ago in a published paper, for instance, that based on global warming patterns, the sand fly vector responsible for cutaneous leishmaniasis would live in the Southern United States and cause endemic infections within 10 years.

And in 2018, Dr. Rosenbach said, a paper in JAMA Dermatology described how more than half – 59% – of the cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed in Texas were endemic, all occurring in people with no prior travel outside the United States.

Dr. Williams’ devotion to climate change and dermatology and to the climate change ERG was inspired in large part by Dr. Rosenbach’s 2017 paper in JAAD. She had long been concerned about climate change, she said, but “the review article was really the impetus for me to think, this is really within my specialty.”

Extreme weather events, and the climate-driven migration expected to increasingly occur, have clear relevance to dermatology, Dr. Williams said. “Often, the most vexing problems that people have when they’re forced out of their homes ... are dermatologic,” she said, like infections from contaminated waters after flooding and the spread of scabies and other communicable diseases due to crowding and unsanitary conditions.

But there are other less obvious ramifications of a changing climate that affect dermatology. Dr. Williams has delved into the literature on heat-related illness, for instance, and found that most research has been in the realm of sports medicine and military health. “Most of us don’t treat serious heat-related illnesses, but our skin is responsible for keeping us cool and there’s an important role for dermatologists to play in knowing how the skin does that and who is at risk for heat illness because the skin is unable to do the full job,” she said.

Research is needed to identify which medications can interfere with the skin’s thermoregulatory responses and put patients at risk, she noted. “And a lot of the work on sweat gland physiology is probably 30 years old now. We should bring to bear contemporary research techniques.”

Dermatology is also “in the early stages of understanding the role that air pollution plays in skin disease,” Dr. Williams said. “Most of the medical literature focuses on the effects of pollution on the lungs and in cardiovascular disease.”

There is evidence linking small particulate matter found in wood smoke and other air pollutants to exacerbations of atopic dermatitis and other inflammatory skin conditions, she noted, but mechanisms need to be explored and health disparities examined. “While we know that there are health disparities in terms of [exposure to] pollution and respiratory illness, we have no idea if this is the case with our skin diseases like atopic dermatitis,” said Dr. Williams.

In general, according to the AAD position statement, low-income and minority communities, in addition to the very young and the very old, “are and will continue to be disproportionately affected by climate change.”

Education and the carbon footprint

Viewing climate change as a social determinant of health (SDH ) – and integrating it into medical training as such – is a topic of active discussion. At UCSF, Sarah J. Coates, MD, a fellow in pediatric dermatology, is working with colleagues to integrate climate change into formal resident education. “We know that climate change affects housing, food security, migration ... and certain populations are and will be especially vulnerable,” she said in an interview. “The effects of climate change fit squarely into the social determinant of health curriculum that we’re building here.”

Dr. Coates began to appreciate the link between climate and infectious diseases – a topic she now writes and speaks about – when she saw several patients with coccidioidomycosis as a dermatology resident at UCSF and learned that the cases represented an epidemic in the Central Valley “resulting from several years of drought.”

Her medical school and residency training were otherwise devoid of any discussion of climate change. At UCSF and nearby Stanford (Calif.) University, this is no longer the case, she and Dr. Williams said. “The medical students here have been quite active and are requesting education,” noted Dr. Williams. “The desire to know more is coming from the bottom.”

Mary E. Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, sees the same interest from physicians-in-training in the Boston area. They want education about climate science, the impact of climate changes on health and risk mitigation, and ways to reduce medicine’s carbon footprint. “We need to teach them and charge them to lead in their communities,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Maloney joined the AAD’s climate change resource group soon after its inception, having realized the urgency of climate change and feeling that she needed “to get passionate and not just do small things.” As a Mohs surgeon, she expects an “explosion” of skin cancer as temperatures and sun exposure continue to increase.

She urges dermatologists to work to decrease the carbon footprint of their practices and to advocate for local hospitals and other clinical institutions to do so. On the AAD website, members now have free access to tools provided by the nonprofit organization My Green Doctor for outpatient offices to lighten their carbon footprints in a cost-effective – or even cost-saving – manner.

Dr. Maloney’s institution has moved to automated lighting systems and the use of LED lights, she said, and has encouraged ride sharing (prior to the pandemic) and computer switch-offs at night. And in her practice, she and a colleague have been working to reduce the purchasing and use of disposable plastics.

Educating patients about the effects of climate change on the health of their skin is another of the missions listed in the AAD’s position statement, and it’s something that Dr. Coates is currently researching. “It seems similar to talking about other social determinants of health,” she said. “Saying to a patient, for instance, ‘we’ve had some really terrible wildfires lately. They’re getting worse as the seasons go on and we know that’s because of climate change. How do you think your current rash relates to the current air quality? How you think the air quality affects your skin?’ ”

Dr. Rosenbach emphasizes that physicians are a broadly trusted group. “I’d tell a patient, ‘you’re the fourth patient I’ve seen with Lyme – we think that’s because it’s been a warmer year due to climate change,’” he said. “I don’t think that bringing up climate change has ever been a source of friction.”

Climate change will increasingly affect the distribution and frequency of insect-borne diseases, cutaneous leishmaniasis, skin cancer, fungal diseases, and a host of other illnesses that have cutaneous manifestations or involve the skin – and dermatologists are being urged to be ready to diagnose clinical findings, counsel patients about risk mitigation, and decrease the carbon footprint of their practices and medical organizations.

“Climate change is not a far-off threat but an urgent health issue,” Misha Rosenbach, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in an editorial with coauthor Mary Sun, a student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. It was first published online in the British Journal of Dermatology last year, titled, “The climate emergency: Why should dermatologists care and how can they act?”.

. Some of the 150-plus members of the ERG have been writing about the dermatologic impacts of climate change – including content that filled the January issue of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology – and speaking about the issues.

A session at the AAD’s virtual annual meeting in April will address climate change and dermatology – the second such session at an annual meeting – and the first two of three planned virtual symposia led by Dr. Rosenbach and his colleagues, have been hosted by the Association of Professors of Dermatology. The ERG encouraged the AAD’s adoption of a position statement in 2018 about climate change and dermatology and its membership in the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health.

“There’s been a lot of conversation in the medical community about the health effects of climate change, but most people leave out the skin,” said Mary L. Williams, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who is a cofounder and coleader with Dr. Rosenbach of the climate change ERG.

“That’s interesting because the skin is the most environmental of all our organs. Of course it will be impacted by all that’s going on,” she said. “We want to bring the dermatologic community and the wider medical community along with us [in appreciating and acting on this knowledge].”

Changing disease patterns

Dr. Rosenbach did not think much about how climate change could affect his patients and his clinical practice until he saw a severe case of hand, foot, and mouth disease in a hospitalized adult in Philadelphia about 10 years ago.

A presentation of the case at an infectious disease conference spurred discussion of how the preceding winters had been warmer and of correlations reported by researchers in China between the incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease – historically a mild infection in children – and average temperature and other meteorological factors. “I knew about climate change, but I never knew we’d see different diseases in our clinical practice, or old diseases affecting new hosts,” Dr. Rosenbach said in an interview.

He pored over the literature to deepen his understanding of climate change science and the impact of climate change on medicine, and found an “emerging focus” on climate change in some medical journals, but “very little in dermatology.” In collaboration with Benjamin Kaffenberger, MD, a dermatologist at The Ohio State University, and colleagues, including an entomologist, Dr. Rosenbach wrote a review of publications relating to climate change and skin disease in North America.

Published in 2017 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the review details how bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites are responding to changing weather patterns in North America, and why dermatologists should be able to recognize changing patterns of disease. Globalization plays a role in changing disease and vector patterns, but “climate change allows expansion of the natural range of pathogens, hosts, reservoirs, and vectors that allow diseases to appear in immunologically naive populations,” they wrote.

Patterns of infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations are already changing. The geographic range of coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, for instance, “has basically doubled in the Southwest U.S., extending up the entire West Coast,” Dr. Rosenbach said, as the result of longer dry seasons and more frequent wind storms that aerosolize the mycosis-causing, soil-dwelling fungal spores.

Lyme disease and associated tick-borne infections continue to expand northward as Ixodes tick vectors move and breed “exactly in sync with a warming world,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “We’re seeing Lyme in Philadelphia in February, whereas in the past we may not have seen it until May ... There are derms in Maine [whose patients have Lyme disease] who may never have seen a case before, and derms in Canada who are making diagnoses of Lyme [for the first time].”

And locally acquired cases of dengue are being reported in Hawaii, Texas, and Florida – and even North Carolina, according to a review of infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations in the issue of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology dedicated to climate change. As with Ixodes ticks, which transmit Lyme disease, rising temperatures lead to longer breeding seasons for Aedes mosquitoes, which transmit dengue. Increased endemicity of dengue is concerning because severe illness is significantly more likely in individuals previously infected with a different serotype.

“Dermatologists should be ready to identify and diagnose these mosquito-borne diseases that we think of as occurring in Central America or tropical regions,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “In my children’s lifetime there will be tropical diseases in New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other such places.”

In his articles and talks, Dr. Rosenbach lays out the science of climate change – for instance, the change in average global temperatures above preindustrial levels (an approximate 1° C rise) , the threshold beyond which the Earth will become less hospitable (1.5° C of warming according to United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the current projections for future warming (an increase of about 3° Celsius by 2100), and the “gold-standard” level of scientific certainty that climate change is human-caused.

Mathematical climate modeling, he emphasized in the interview, can accurately project changes in infection rates. Researchers predicted 10 years ago in a published paper, for instance, that based on global warming patterns, the sand fly vector responsible for cutaneous leishmaniasis would live in the Southern United States and cause endemic infections within 10 years.

And in 2018, Dr. Rosenbach said, a paper in JAMA Dermatology described how more than half – 59% – of the cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed in Texas were endemic, all occurring in people with no prior travel outside the United States.

Dr. Williams’ devotion to climate change and dermatology and to the climate change ERG was inspired in large part by Dr. Rosenbach’s 2017 paper in JAAD. She had long been concerned about climate change, she said, but “the review article was really the impetus for me to think, this is really within my specialty.”

Extreme weather events, and the climate-driven migration expected to increasingly occur, have clear relevance to dermatology, Dr. Williams said. “Often, the most vexing problems that people have when they’re forced out of their homes ... are dermatologic,” she said, like infections from contaminated waters after flooding and the spread of scabies and other communicable diseases due to crowding and unsanitary conditions.

But there are other less obvious ramifications of a changing climate that affect dermatology. Dr. Williams has delved into the literature on heat-related illness, for instance, and found that most research has been in the realm of sports medicine and military health. “Most of us don’t treat serious heat-related illnesses, but our skin is responsible for keeping us cool and there’s an important role for dermatologists to play in knowing how the skin does that and who is at risk for heat illness because the skin is unable to do the full job,” she said.

Research is needed to identify which medications can interfere with the skin’s thermoregulatory responses and put patients at risk, she noted. “And a lot of the work on sweat gland physiology is probably 30 years old now. We should bring to bear contemporary research techniques.”

Dermatology is also “in the early stages of understanding the role that air pollution plays in skin disease,” Dr. Williams said. “Most of the medical literature focuses on the effects of pollution on the lungs and in cardiovascular disease.”

There is evidence linking small particulate matter found in wood smoke and other air pollutants to exacerbations of atopic dermatitis and other inflammatory skin conditions, she noted, but mechanisms need to be explored and health disparities examined. “While we know that there are health disparities in terms of [exposure to] pollution and respiratory illness, we have no idea if this is the case with our skin diseases like atopic dermatitis,” said Dr. Williams.

In general, according to the AAD position statement, low-income and minority communities, in addition to the very young and the very old, “are and will continue to be disproportionately affected by climate change.”

Education and the carbon footprint

Viewing climate change as a social determinant of health (SDH ) – and integrating it into medical training as such – is a topic of active discussion. At UCSF, Sarah J. Coates, MD, a fellow in pediatric dermatology, is working with colleagues to integrate climate change into formal resident education. “We know that climate change affects housing, food security, migration ... and certain populations are and will be especially vulnerable,” she said in an interview. “The effects of climate change fit squarely into the social determinant of health curriculum that we’re building here.”

Dr. Coates began to appreciate the link between climate and infectious diseases – a topic she now writes and speaks about – when she saw several patients with coccidioidomycosis as a dermatology resident at UCSF and learned that the cases represented an epidemic in the Central Valley “resulting from several years of drought.”

Her medical school and residency training were otherwise devoid of any discussion of climate change. At UCSF and nearby Stanford (Calif.) University, this is no longer the case, she and Dr. Williams said. “The medical students here have been quite active and are requesting education,” noted Dr. Williams. “The desire to know more is coming from the bottom.”

Mary E. Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, sees the same interest from physicians-in-training in the Boston area. They want education about climate science, the impact of climate changes on health and risk mitigation, and ways to reduce medicine’s carbon footprint. “We need to teach them and charge them to lead in their communities,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Maloney joined the AAD’s climate change resource group soon after its inception, having realized the urgency of climate change and feeling that she needed “to get passionate and not just do small things.” As a Mohs surgeon, she expects an “explosion” of skin cancer as temperatures and sun exposure continue to increase.

She urges dermatologists to work to decrease the carbon footprint of their practices and to advocate for local hospitals and other clinical institutions to do so. On the AAD website, members now have free access to tools provided by the nonprofit organization My Green Doctor for outpatient offices to lighten their carbon footprints in a cost-effective – or even cost-saving – manner.

Dr. Maloney’s institution has moved to automated lighting systems and the use of LED lights, she said, and has encouraged ride sharing (prior to the pandemic) and computer switch-offs at night. And in her practice, she and a colleague have been working to reduce the purchasing and use of disposable plastics.

Educating patients about the effects of climate change on the health of their skin is another of the missions listed in the AAD’s position statement, and it’s something that Dr. Coates is currently researching. “It seems similar to talking about other social determinants of health,” she said. “Saying to a patient, for instance, ‘we’ve had some really terrible wildfires lately. They’re getting worse as the seasons go on and we know that’s because of climate change. How do you think your current rash relates to the current air quality? How you think the air quality affects your skin?’ ”

Dr. Rosenbach emphasizes that physicians are a broadly trusted group. “I’d tell a patient, ‘you’re the fourth patient I’ve seen with Lyme – we think that’s because it’s been a warmer year due to climate change,’” he said. “I don’t think that bringing up climate change has ever been a source of friction.”

Applying lessons from Oprah to your practice

In my last column, I explained how I’m like Tom Brady. I’m not really. Brady is a Super Bowl–winning quarterback worth over $200 million. No, I’m like Oprah. Well, trying anyway.

Brady and Oprah, in addition to being gazillionaires, have in common that they’re arguably the GOATs (Greatest Of All Time) in their fields. Watching Oprah interview Meghan Markle and Prince Harry was like watching Tom Brady on the jumbotron – she made it look easy. Her ability to create conversation and coax information from guests is hall-of-fame good. But although they are both admirable, trying to be like Brady is useful only for next Thanksgiving when you’re trying to beat your cousins from Massachusetts in touch football. .

1. Prepare ahead. It’s clear that Oprah has binders of notes about her guests and thoroughly reviewed them before she invites them to sit down. We should do the same. Open the chart and read as much as you can before you open the door. Have important information in your head so you don’t have to break from your interview to refer to it.

2. Sprinkle pleasantry. She’d never start an interview with: So why are you here? Nor should we. Even one nonscripted question or comment can help build a little rapport before getting to the work.

3. Be brief. Oprah gets her question out fast, then gets out of the way. And as a bonus, this is the easiest place to shave a few minutes from your appointments from your own end. Think for a second before you speak and try to find the shortest route to your question. Try to keep your questions to just a sentence or two.

4. Stay on it. Once you’ve discovered something relevant, stay with it, resisting the urge to finish the review of symptoms. This is not just to make a diagnosis, but as importantly, trying to diagnose “the real reason” for the visit. Then, when the question is done, own the transition. Oprah uses: “Let’s move on.” This is a bit abrupt for us, but it can be helpful if used sparingly and gently. I might soften this a little by adding “I want to be sure we have enough time to get through everything for you.”

5. Wait. A few seconds seems an eternity on the air (and in clinic), but sometimes the silent pause is just what’s needed to help the patient expand and share.

6. Be nonjudgmental. Most of us believe we’re pretty good at this, yet, it’s sometimes a blind spot. It’s easy to blame the obese patient for his stasis dermatitis or the hidradenitis patient who hasn’t stop smoking for her cysts. It also helps to be nontransactional. If you make patients feel that you’re asking questions only to extract information, you’ll never reach Oprah level.

7. Be in the moment. It is difficult, but when possible, avoid typing notes while you’re still interviewing. We’re not just there to get the facts, we’re also trying to get the story and that sometimes takes really listening.

I’m no more like Oprah than Brady, of course. But it is more fun to close my eyes and imagine myself being her when I see my next patient. That is, until Thanksgiving. Watch out, Bedards from Attleboro.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my last column, I explained how I’m like Tom Brady. I’m not really. Brady is a Super Bowl–winning quarterback worth over $200 million. No, I’m like Oprah. Well, trying anyway.

Brady and Oprah, in addition to being gazillionaires, have in common that they’re arguably the GOATs (Greatest Of All Time) in their fields. Watching Oprah interview Meghan Markle and Prince Harry was like watching Tom Brady on the jumbotron – she made it look easy. Her ability to create conversation and coax information from guests is hall-of-fame good. But although they are both admirable, trying to be like Brady is useful only for next Thanksgiving when you’re trying to beat your cousins from Massachusetts in touch football. .

1. Prepare ahead. It’s clear that Oprah has binders of notes about her guests and thoroughly reviewed them before she invites them to sit down. We should do the same. Open the chart and read as much as you can before you open the door. Have important information in your head so you don’t have to break from your interview to refer to it.

2. Sprinkle pleasantry. She’d never start an interview with: So why are you here? Nor should we. Even one nonscripted question or comment can help build a little rapport before getting to the work.

3. Be brief. Oprah gets her question out fast, then gets out of the way. And as a bonus, this is the easiest place to shave a few minutes from your appointments from your own end. Think for a second before you speak and try to find the shortest route to your question. Try to keep your questions to just a sentence or two.

4. Stay on it. Once you’ve discovered something relevant, stay with it, resisting the urge to finish the review of symptoms. This is not just to make a diagnosis, but as importantly, trying to diagnose “the real reason” for the visit. Then, when the question is done, own the transition. Oprah uses: “Let’s move on.” This is a bit abrupt for us, but it can be helpful if used sparingly and gently. I might soften this a little by adding “I want to be sure we have enough time to get through everything for you.”

5. Wait. A few seconds seems an eternity on the air (and in clinic), but sometimes the silent pause is just what’s needed to help the patient expand and share.

6. Be nonjudgmental. Most of us believe we’re pretty good at this, yet, it’s sometimes a blind spot. It’s easy to blame the obese patient for his stasis dermatitis or the hidradenitis patient who hasn’t stop smoking for her cysts. It also helps to be nontransactional. If you make patients feel that you’re asking questions only to extract information, you’ll never reach Oprah level.

7. Be in the moment. It is difficult, but when possible, avoid typing notes while you’re still interviewing. We’re not just there to get the facts, we’re also trying to get the story and that sometimes takes really listening.

I’m no more like Oprah than Brady, of course. But it is more fun to close my eyes and imagine myself being her when I see my next patient. That is, until Thanksgiving. Watch out, Bedards from Attleboro.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my last column, I explained how I’m like Tom Brady. I’m not really. Brady is a Super Bowl–winning quarterback worth over $200 million. No, I’m like Oprah. Well, trying anyway.

Brady and Oprah, in addition to being gazillionaires, have in common that they’re arguably the GOATs (Greatest Of All Time) in their fields. Watching Oprah interview Meghan Markle and Prince Harry was like watching Tom Brady on the jumbotron – she made it look easy. Her ability to create conversation and coax information from guests is hall-of-fame good. But although they are both admirable, trying to be like Brady is useful only for next Thanksgiving when you’re trying to beat your cousins from Massachusetts in touch football. .

1. Prepare ahead. It’s clear that Oprah has binders of notes about her guests and thoroughly reviewed them before she invites them to sit down. We should do the same. Open the chart and read as much as you can before you open the door. Have important information in your head so you don’t have to break from your interview to refer to it.

2. Sprinkle pleasantry. She’d never start an interview with: So why are you here? Nor should we. Even one nonscripted question or comment can help build a little rapport before getting to the work.

3. Be brief. Oprah gets her question out fast, then gets out of the way. And as a bonus, this is the easiest place to shave a few minutes from your appointments from your own end. Think for a second before you speak and try to find the shortest route to your question. Try to keep your questions to just a sentence or two.

4. Stay on it. Once you’ve discovered something relevant, stay with it, resisting the urge to finish the review of symptoms. This is not just to make a diagnosis, but as importantly, trying to diagnose “the real reason” for the visit. Then, when the question is done, own the transition. Oprah uses: “Let’s move on.” This is a bit abrupt for us, but it can be helpful if used sparingly and gently. I might soften this a little by adding “I want to be sure we have enough time to get through everything for you.”

5. Wait. A few seconds seems an eternity on the air (and in clinic), but sometimes the silent pause is just what’s needed to help the patient expand and share.

6. Be nonjudgmental. Most of us believe we’re pretty good at this, yet, it’s sometimes a blind spot. It’s easy to blame the obese patient for his stasis dermatitis or the hidradenitis patient who hasn’t stop smoking for her cysts. It also helps to be nontransactional. If you make patients feel that you’re asking questions only to extract information, you’ll never reach Oprah level.

7. Be in the moment. It is difficult, but when possible, avoid typing notes while you’re still interviewing. We’re not just there to get the facts, we’re also trying to get the story and that sometimes takes really listening.

I’m no more like Oprah than Brady, of course. But it is more fun to close my eyes and imagine myself being her when I see my next patient. That is, until Thanksgiving. Watch out, Bedards from Attleboro.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Survey explores impact of pandemic on dermatologist happiness, burnout

, according to Medscape’s 2021 Dermatologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report.

In addition, 15% reported being burned out, and 3% reported being depressed, yet about half reported being too busy to seek help for burnout and/or depression.

Those are among the key findings from the Medscape report, which was published online on Feb. 19, 2021. More than 12,000 physicians from 29 specialties, including dermatology, participated in the survey, which explores how physicians are coping with burnout, maintaining their personal wellness, and viewing their workplaces and futures amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

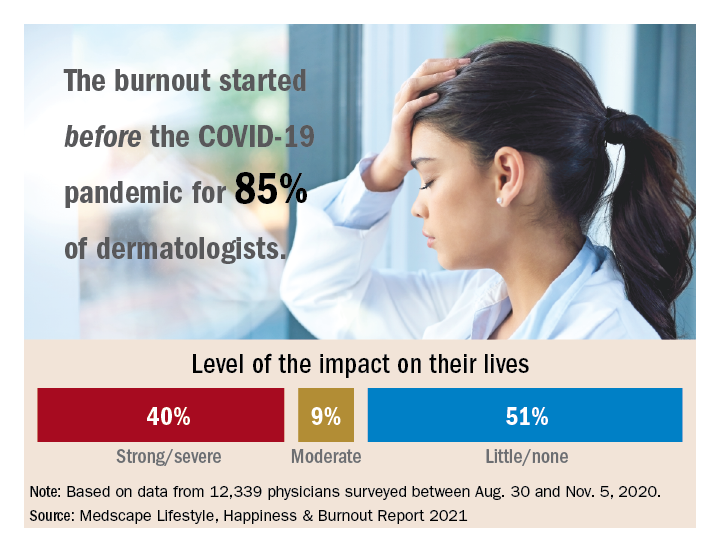

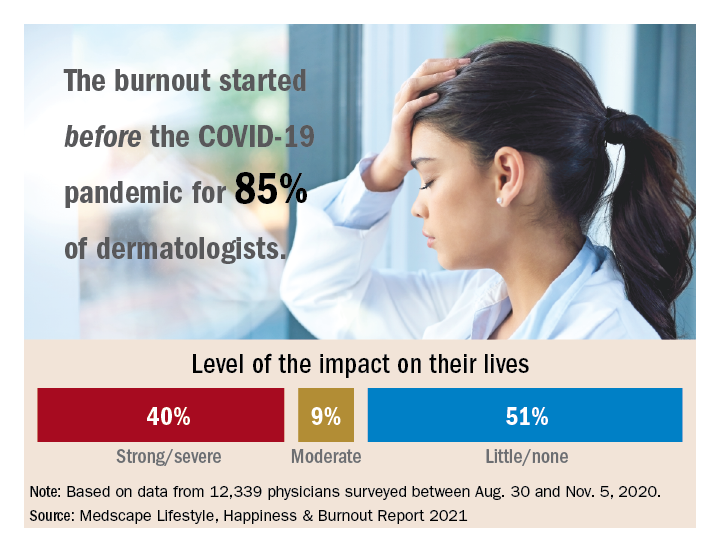

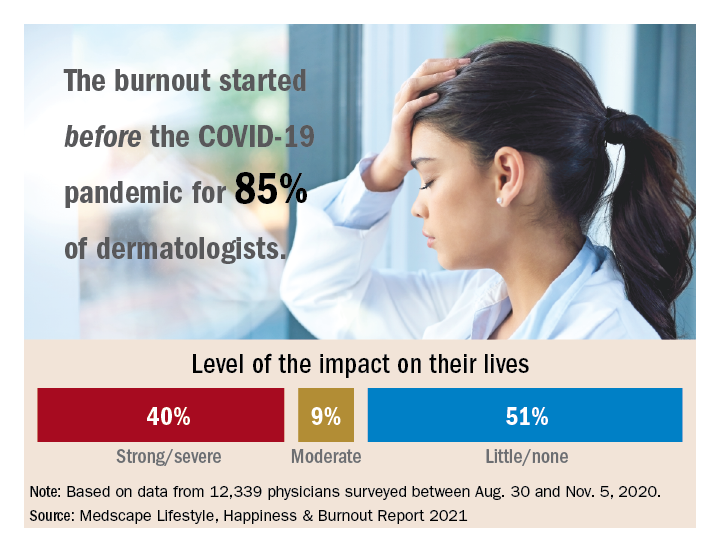

Among dermatologists who reported burnout, 85% said that it started prior to the pandemic, but 15% said it began with the pandemic. That finding resonates with Diane L. Whitaker-Worth, MD, a dermatologist with the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington. “A lot of dermatology practices closed down for a while, which was a huge economic hit,” she said in an interview. “I work for a university, so the stress wasn’t quite as bad. We shut down for about a week, but we canceled a lot of visits. We ramped up quickly, and I would say by the summer more people were coming in. Then we got backlogged. We’re still drowning in the number of patients who want to get in sooner, who can’t get an appointment, who need to be seen. It’s unbelievable, and it’s unrelenting.”

Dermatology trainees were also upended, with many residency programs going virtual. “We had to quickly figure out how to continue educating our residents,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who also directs the university’s dermatology residency program. “What’s reasonable to expect them to be doing in clinic? There were fears about becoming infected [with the] virus. Every week, I had double the amount of work in the bureaucratic realm, trying to figure out how we run our clinic and keep our residents safe but learning. That was hard and the residents were really stressed. They were afraid they were going to get pulled to the ICUs. At that time, we didn’t have adequate PPE, and patients and doctors were dying.”

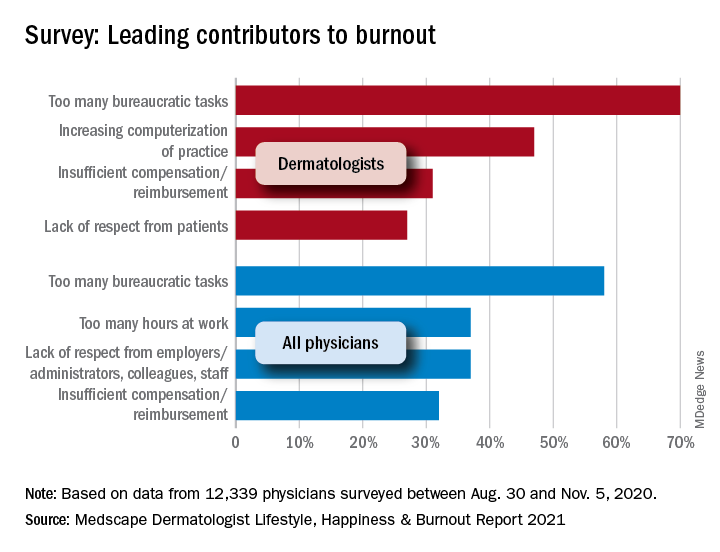

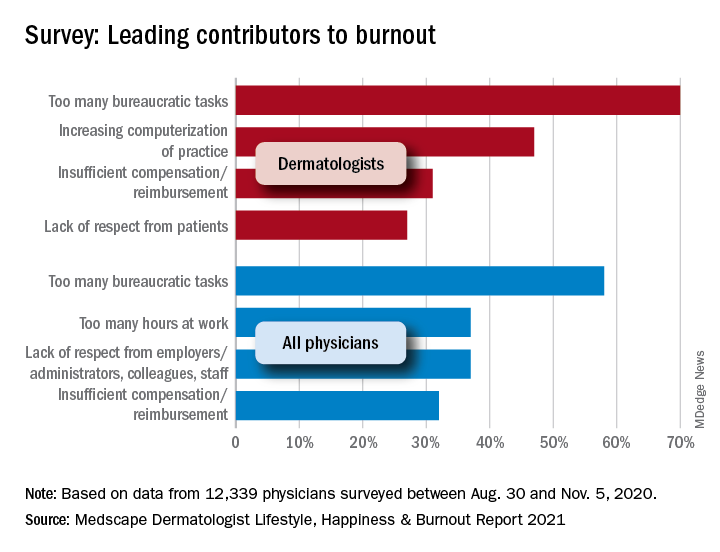

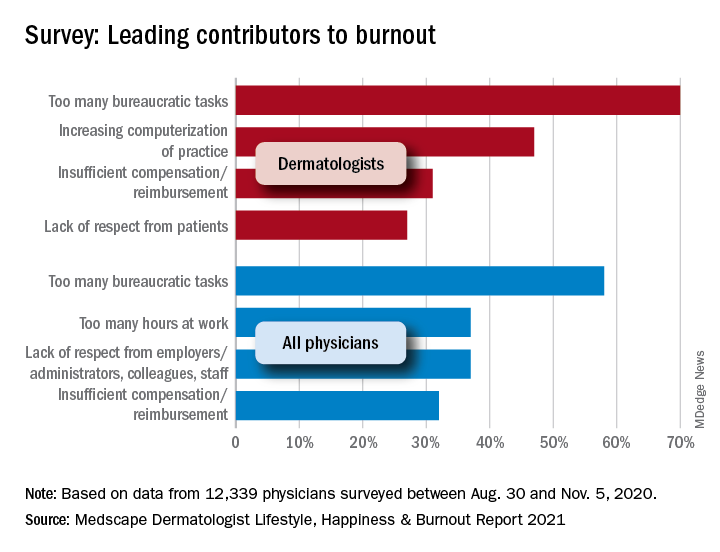

According to the dermatologists who responded to the Medscape survey and reported burnout, the seven chief contributors to burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (70%); increasing computerization of practice (47%); insufficient compensation/reimbursement (31%); lack of respect from patients (27%); government regulations (26%); lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff (23%); and stress from social distancing/societal issues related to COVID-19 (15%).

“Even though dermatologists seemingly have such a nice schedule, compared to a lot of other doctors, it’s still a very stressful occupation,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who coauthored a study on the topic of burnout among female dermatologists. “It is harder to practice now because there are so many people telling us how we have to do things. That will burn you out over time, when control is taken away, when tasks are handed to you randomly by different entities – insurance companies, the government, the electronic medical record.”

Among dermatologists who self-reported burnout on the survey, 51% said it had no impact on their life, 9% said the impact was moderate, while 40% indicated that it had a strong/severe impact. About half (49%) use exercise to cope with burnout, while other key coping strategies include talking with family members/close friends (40%), playing or listening to music (39%), isolating themselves from others (35%), eating junk food (35%), and drinking alcohol (30%). At the same time, only 6% indicated that they are currently seeking professional health for their burnout and/or depression, and 3% indicated that they are planning to seek professional help. When asked why they hadn’t sought help for their burnout and/or depression, 51% of respondents said they were too busy and 36% said their symptoms weren’t severe enough.

Dr. Whitaker-Worth characterized bureaucratic tasks as “a huge cause” of her burnout, but the larger contributor, she said, is managing her role as wife and mother of four children who are currently at home attending online school classes or working remotely, while she juggles her own work responsibilities. “They were stressed,” she said of her children. “The whole world was stressed. There are exceptions, but I still think that women are mostly shouldering the tasks at home. Even if they’re not doing them, they’re still feeling responsible for them. During the pandemic, every aspect of life became harder. Work was harder. Getting kids focused on school was harder. Doing basic tasks like errands was harder.”

Despite the stress and uncertainty generated by the pandemic, Dr. Whitaker-Worth considers dermatology as one of the happier specialties in medicine. “We still have a little more control of our time,” she said. “We are lucky in that we have reasonable hours, not as much in-house call, and a little more control over our day. I think work-life balance is the main thing that drives burnout – over bureaucracy, over everything.”

, according to Medscape’s 2021 Dermatologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report.

In addition, 15% reported being burned out, and 3% reported being depressed, yet about half reported being too busy to seek help for burnout and/or depression.

Those are among the key findings from the Medscape report, which was published online on Feb. 19, 2021. More than 12,000 physicians from 29 specialties, including dermatology, participated in the survey, which explores how physicians are coping with burnout, maintaining their personal wellness, and viewing their workplaces and futures amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among dermatologists who reported burnout, 85% said that it started prior to the pandemic, but 15% said it began with the pandemic. That finding resonates with Diane L. Whitaker-Worth, MD, a dermatologist with the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington. “A lot of dermatology practices closed down for a while, which was a huge economic hit,” she said in an interview. “I work for a university, so the stress wasn’t quite as bad. We shut down for about a week, but we canceled a lot of visits. We ramped up quickly, and I would say by the summer more people were coming in. Then we got backlogged. We’re still drowning in the number of patients who want to get in sooner, who can’t get an appointment, who need to be seen. It’s unbelievable, and it’s unrelenting.”

Dermatology trainees were also upended, with many residency programs going virtual. “We had to quickly figure out how to continue educating our residents,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who also directs the university’s dermatology residency program. “What’s reasonable to expect them to be doing in clinic? There were fears about becoming infected [with the] virus. Every week, I had double the amount of work in the bureaucratic realm, trying to figure out how we run our clinic and keep our residents safe but learning. That was hard and the residents were really stressed. They were afraid they were going to get pulled to the ICUs. At that time, we didn’t have adequate PPE, and patients and doctors were dying.”

According to the dermatologists who responded to the Medscape survey and reported burnout, the seven chief contributors to burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (70%); increasing computerization of practice (47%); insufficient compensation/reimbursement (31%); lack of respect from patients (27%); government regulations (26%); lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff (23%); and stress from social distancing/societal issues related to COVID-19 (15%).

“Even though dermatologists seemingly have such a nice schedule, compared to a lot of other doctors, it’s still a very stressful occupation,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who coauthored a study on the topic of burnout among female dermatologists. “It is harder to practice now because there are so many people telling us how we have to do things. That will burn you out over time, when control is taken away, when tasks are handed to you randomly by different entities – insurance companies, the government, the electronic medical record.”

Among dermatologists who self-reported burnout on the survey, 51% said it had no impact on their life, 9% said the impact was moderate, while 40% indicated that it had a strong/severe impact. About half (49%) use exercise to cope with burnout, while other key coping strategies include talking with family members/close friends (40%), playing or listening to music (39%), isolating themselves from others (35%), eating junk food (35%), and drinking alcohol (30%). At the same time, only 6% indicated that they are currently seeking professional health for their burnout and/or depression, and 3% indicated that they are planning to seek professional help. When asked why they hadn’t sought help for their burnout and/or depression, 51% of respondents said they were too busy and 36% said their symptoms weren’t severe enough.

Dr. Whitaker-Worth characterized bureaucratic tasks as “a huge cause” of her burnout, but the larger contributor, she said, is managing her role as wife and mother of four children who are currently at home attending online school classes or working remotely, while she juggles her own work responsibilities. “They were stressed,” she said of her children. “The whole world was stressed. There are exceptions, but I still think that women are mostly shouldering the tasks at home. Even if they’re not doing them, they’re still feeling responsible for them. During the pandemic, every aspect of life became harder. Work was harder. Getting kids focused on school was harder. Doing basic tasks like errands was harder.”

Despite the stress and uncertainty generated by the pandemic, Dr. Whitaker-Worth considers dermatology as one of the happier specialties in medicine. “We still have a little more control of our time,” she said. “We are lucky in that we have reasonable hours, not as much in-house call, and a little more control over our day. I think work-life balance is the main thing that drives burnout – over bureaucracy, over everything.”

, according to Medscape’s 2021 Dermatologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report.

In addition, 15% reported being burned out, and 3% reported being depressed, yet about half reported being too busy to seek help for burnout and/or depression.

Those are among the key findings from the Medscape report, which was published online on Feb. 19, 2021. More than 12,000 physicians from 29 specialties, including dermatology, participated in the survey, which explores how physicians are coping with burnout, maintaining their personal wellness, and viewing their workplaces and futures amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among dermatologists who reported burnout, 85% said that it started prior to the pandemic, but 15% said it began with the pandemic. That finding resonates with Diane L. Whitaker-Worth, MD, a dermatologist with the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington. “A lot of dermatology practices closed down for a while, which was a huge economic hit,” she said in an interview. “I work for a university, so the stress wasn’t quite as bad. We shut down for about a week, but we canceled a lot of visits. We ramped up quickly, and I would say by the summer more people were coming in. Then we got backlogged. We’re still drowning in the number of patients who want to get in sooner, who can’t get an appointment, who need to be seen. It’s unbelievable, and it’s unrelenting.”

Dermatology trainees were also upended, with many residency programs going virtual. “We had to quickly figure out how to continue educating our residents,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who also directs the university’s dermatology residency program. “What’s reasonable to expect them to be doing in clinic? There were fears about becoming infected [with the] virus. Every week, I had double the amount of work in the bureaucratic realm, trying to figure out how we run our clinic and keep our residents safe but learning. That was hard and the residents were really stressed. They were afraid they were going to get pulled to the ICUs. At that time, we didn’t have adequate PPE, and patients and doctors were dying.”

According to the dermatologists who responded to the Medscape survey and reported burnout, the seven chief contributors to burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (70%); increasing computerization of practice (47%); insufficient compensation/reimbursement (31%); lack of respect from patients (27%); government regulations (26%); lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff (23%); and stress from social distancing/societal issues related to COVID-19 (15%).

“Even though dermatologists seemingly have such a nice schedule, compared to a lot of other doctors, it’s still a very stressful occupation,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who coauthored a study on the topic of burnout among female dermatologists. “It is harder to practice now because there are so many people telling us how we have to do things. That will burn you out over time, when control is taken away, when tasks are handed to you randomly by different entities – insurance companies, the government, the electronic medical record.”

Among dermatologists who self-reported burnout on the survey, 51% said it had no impact on their life, 9% said the impact was moderate, while 40% indicated that it had a strong/severe impact. About half (49%) use exercise to cope with burnout, while other key coping strategies include talking with family members/close friends (40%), playing or listening to music (39%), isolating themselves from others (35%), eating junk food (35%), and drinking alcohol (30%). At the same time, only 6% indicated that they are currently seeking professional health for their burnout and/or depression, and 3% indicated that they are planning to seek professional help. When asked why they hadn’t sought help for their burnout and/or depression, 51% of respondents said they were too busy and 36% said their symptoms weren’t severe enough.

Dr. Whitaker-Worth characterized bureaucratic tasks as “a huge cause” of her burnout, but the larger contributor, she said, is managing her role as wife and mother of four children who are currently at home attending online school classes or working remotely, while she juggles her own work responsibilities. “They were stressed,” she said of her children. “The whole world was stressed. There are exceptions, but I still think that women are mostly shouldering the tasks at home. Even if they’re not doing them, they’re still feeling responsible for them. During the pandemic, every aspect of life became harder. Work was harder. Getting kids focused on school was harder. Doing basic tasks like errands was harder.”

Despite the stress and uncertainty generated by the pandemic, Dr. Whitaker-Worth considers dermatology as one of the happier specialties in medicine. “We still have a little more control of our time,” she said. “We are lucky in that we have reasonable hours, not as much in-house call, and a little more control over our day. I think work-life balance is the main thing that drives burnout – over bureaucracy, over everything.”

Office etiquette: Answering patient phone calls

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.