User login

Atopic dermatitis: Dupilumab safe and effective in real world

Key clinical point: Dupilumab effectively reduced signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD) along with a tolerable safety profile in a real-world setting during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Major finding: At least 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index was achieved by 66.6%, 89.5%, and 95.8% patients at 16 weeks, 1 year, and 2 years of dupilumab therapy, respectively, with persistence rates being >90% throughout the 2 years of therapy. The most reported adverse events were infections, with a mild course of COVID-19 being the most reported (4.7%), followed by ocular complications (2.5%).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, multicenter study including 360 adults with severe AD who received ≥1 dose of dupilumab.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Some authors declared serving as a consultant, speaker, or investigator for several sources.

Source: Kojanova M et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: real-world data from the Czech Republic BIOREP registry. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2043545

Key clinical point: Dupilumab effectively reduced signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD) along with a tolerable safety profile in a real-world setting during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Major finding: At least 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index was achieved by 66.6%, 89.5%, and 95.8% patients at 16 weeks, 1 year, and 2 years of dupilumab therapy, respectively, with persistence rates being >90% throughout the 2 years of therapy. The most reported adverse events were infections, with a mild course of COVID-19 being the most reported (4.7%), followed by ocular complications (2.5%).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, multicenter study including 360 adults with severe AD who received ≥1 dose of dupilumab.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Some authors declared serving as a consultant, speaker, or investigator for several sources.

Source: Kojanova M et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: real-world data from the Czech Republic BIOREP registry. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2043545

Key clinical point: Dupilumab effectively reduced signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD) along with a tolerable safety profile in a real-world setting during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Major finding: At least 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index was achieved by 66.6%, 89.5%, and 95.8% patients at 16 weeks, 1 year, and 2 years of dupilumab therapy, respectively, with persistence rates being >90% throughout the 2 years of therapy. The most reported adverse events were infections, with a mild course of COVID-19 being the most reported (4.7%), followed by ocular complications (2.5%).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, multicenter study including 360 adults with severe AD who received ≥1 dose of dupilumab.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Some authors declared serving as a consultant, speaker, or investigator for several sources.

Source: Kojanova M et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: real-world data from the Czech Republic BIOREP registry. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2043545

Age and sex determine risk for acne in patients with atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Risk for acne was comparable in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) and matched reference individuals from the general population; however, the risk varied with age and sex, with males and older patients appearing to be at higher risk.

Major finding: Although the overall risk for acne was similar among patients with AD vs. reference individuals (hazard ratio [HR] 0.96; P = .4623), the risk was significantly higher in males with AD (HR 1.22; P = .0234) and in patients aged 30-39 (HR 1.41; P = .0156) and ≥40 (HR 2.07; P = .0002) years.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective cohort study including 6,600 adults and adolescents with AD matched with 66,000 reference individuals without AD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared serving as an advisory board member, investigator, speaker, consultant, or receiving honoraria, fees, research funding, and research support from several sources.

Source: Thyssen JP et al. Incidence, prevalence and risk of acne in adolescent and adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a matched cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 (Feb 26). Doi: 10.1111/jdv.18027

Key clinical point: Risk for acne was comparable in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) and matched reference individuals from the general population; however, the risk varied with age and sex, with males and older patients appearing to be at higher risk.

Major finding: Although the overall risk for acne was similar among patients with AD vs. reference individuals (hazard ratio [HR] 0.96; P = .4623), the risk was significantly higher in males with AD (HR 1.22; P = .0234) and in patients aged 30-39 (HR 1.41; P = .0156) and ≥40 (HR 2.07; P = .0002) years.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective cohort study including 6,600 adults and adolescents with AD matched with 66,000 reference individuals without AD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared serving as an advisory board member, investigator, speaker, consultant, or receiving honoraria, fees, research funding, and research support from several sources.

Source: Thyssen JP et al. Incidence, prevalence and risk of acne in adolescent and adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a matched cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 (Feb 26). Doi: 10.1111/jdv.18027

Key clinical point: Risk for acne was comparable in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) and matched reference individuals from the general population; however, the risk varied with age and sex, with males and older patients appearing to be at higher risk.

Major finding: Although the overall risk for acne was similar among patients with AD vs. reference individuals (hazard ratio [HR] 0.96; P = .4623), the risk was significantly higher in males with AD (HR 1.22; P = .0234) and in patients aged 30-39 (HR 1.41; P = .0156) and ≥40 (HR 2.07; P = .0002) years.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective cohort study including 6,600 adults and adolescents with AD matched with 66,000 reference individuals without AD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared serving as an advisory board member, investigator, speaker, consultant, or receiving honoraria, fees, research funding, and research support from several sources.

Source: Thyssen JP et al. Incidence, prevalence and risk of acne in adolescent and adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a matched cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 (Feb 26). Doi: 10.1111/jdv.18027

Disease severity predicts persistent sleep disturbance from atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: A significant proportion of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) experience sleep disturbance (SD), which usually improves overtime; however, patients with moderate-to-severe AD are more likely to experience a persistent SD course.

Major finding: At least 3 nights of SD were reported by 34.2% of patients at baseline; however only 12.3% of patients reported persistent SD at the first and second follow-ups, and only 11.5% of patients with severe SD at baseline experienced persistent SD scores at the second follow-up. Severe/very severe AD vs. mild AD was a significant predictor of increased nights of SD by eczema (adjusted odds ratio 16.20; P < .0001).

Study details: This prospective, dermatology practice-based study included 1,295 patients with mild (40.5%), moderate (35.1%), or severe/very severe (24.4%) AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Dermatology Foundation, and an unrestricted research grant from Galderma. R Chavda and S Gabriel declared being employees of and JI Silverberg declared being a consultant for Galderma.

Source: Manjunath J et al. longitudinal course of sleep disturbance and relationship with itch in adult atopic dermatitis in clinical practice. Dermatitis. 2022 (Mar 3). Doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000859

Key clinical point: A significant proportion of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) experience sleep disturbance (SD), which usually improves overtime; however, patients with moderate-to-severe AD are more likely to experience a persistent SD course.

Major finding: At least 3 nights of SD were reported by 34.2% of patients at baseline; however only 12.3% of patients reported persistent SD at the first and second follow-ups, and only 11.5% of patients with severe SD at baseline experienced persistent SD scores at the second follow-up. Severe/very severe AD vs. mild AD was a significant predictor of increased nights of SD by eczema (adjusted odds ratio 16.20; P < .0001).

Study details: This prospective, dermatology practice-based study included 1,295 patients with mild (40.5%), moderate (35.1%), or severe/very severe (24.4%) AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Dermatology Foundation, and an unrestricted research grant from Galderma. R Chavda and S Gabriel declared being employees of and JI Silverberg declared being a consultant for Galderma.

Source: Manjunath J et al. longitudinal course of sleep disturbance and relationship with itch in adult atopic dermatitis in clinical practice. Dermatitis. 2022 (Mar 3). Doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000859

Key clinical point: A significant proportion of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) experience sleep disturbance (SD), which usually improves overtime; however, patients with moderate-to-severe AD are more likely to experience a persistent SD course.

Major finding: At least 3 nights of SD were reported by 34.2% of patients at baseline; however only 12.3% of patients reported persistent SD at the first and second follow-ups, and only 11.5% of patients with severe SD at baseline experienced persistent SD scores at the second follow-up. Severe/very severe AD vs. mild AD was a significant predictor of increased nights of SD by eczema (adjusted odds ratio 16.20; P < .0001).

Study details: This prospective, dermatology practice-based study included 1,295 patients with mild (40.5%), moderate (35.1%), or severe/very severe (24.4%) AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Dermatology Foundation, and an unrestricted research grant from Galderma. R Chavda and S Gabriel declared being employees of and JI Silverberg declared being a consultant for Galderma.

Source: Manjunath J et al. longitudinal course of sleep disturbance and relationship with itch in adult atopic dermatitis in clinical practice. Dermatitis. 2022 (Mar 3). Doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000859

Atopic dermatitis and serum lipids: What is the link?

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) was negatively associated with some serum lipids, indicating AD being intrinsically protective for dyslipidemia.

Major finding: AD was significantly associated with lower levels of total cholesterol (β −0.004; P < .001), triglycerides (β −0.006; P = .006), and low-density lipoprotein (β −0.004; P < .001) but not with high-density lipoprotein (P = .794).

Study details: The data come from a large-scale, cross-sectional study including 13,822 patients with AD and 67,896 patients with asthma.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China Precision Medicine Initiative and the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities. The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Source: Tang Z et al. Association between atopic dermatitis, asthma, and serum lipids: A UK Biobank based observational study and Mendelian randomization analysis. Front Med. 2022 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.810092

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) was negatively associated with some serum lipids, indicating AD being intrinsically protective for dyslipidemia.

Major finding: AD was significantly associated with lower levels of total cholesterol (β −0.004; P < .001), triglycerides (β −0.006; P = .006), and low-density lipoprotein (β −0.004; P < .001) but not with high-density lipoprotein (P = .794).

Study details: The data come from a large-scale, cross-sectional study including 13,822 patients with AD and 67,896 patients with asthma.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China Precision Medicine Initiative and the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities. The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Source: Tang Z et al. Association between atopic dermatitis, asthma, and serum lipids: A UK Biobank based observational study and Mendelian randomization analysis. Front Med. 2022 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.810092

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) was negatively associated with some serum lipids, indicating AD being intrinsically protective for dyslipidemia.

Major finding: AD was significantly associated with lower levels of total cholesterol (β −0.004; P < .001), triglycerides (β −0.006; P = .006), and low-density lipoprotein (β −0.004; P < .001) but not with high-density lipoprotein (P = .794).

Study details: The data come from a large-scale, cross-sectional study including 13,822 patients with AD and 67,896 patients with asthma.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China Precision Medicine Initiative and the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities. The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Source: Tang Z et al. Association between atopic dermatitis, asthma, and serum lipids: A UK Biobank based observational study and Mendelian randomization analysis. Front Med. 2022 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.810092

Moisturizer containing urea and glycerol shows skin barrier-strengthening effects in atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: A 4-week treatment with a test cream (TC) containing only 2% urea and 20% glycerol significantly reduced sodium lauryl sulphate-induced skin irritation in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) compared with a no treatment control (NTC) and two reference creams.

Major finding: After 28 days, there was a significant reduction in transepidermal water loss with TC vs. NTC (P < .001), paraffin cream (P < .001), and glycerol cream (P = .021); objective redness was lower with TC vs. NTC (P = .002) and paraffin cream (P < .001). The TC was well tolerated with no evidence of stinging or redness.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 trial including 49 adults with AD who were randomly assigned to receive either a TC containing urea and glycerol, a glycerol-containing moisturizer, a simple paraffin cream containing no humectant, or NTC.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Perrigo Nordic. The authors declared serving as consultants, investigators, or advisory board members for and receiving research grants from several sources. Three authors declared being employees of Perrigo Nordic.

Source: Danby SG et al. Different types of emollient cream exhibit diverse physiological effects on the skin barrier in adults with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/ced.15141

Key clinical point: A 4-week treatment with a test cream (TC) containing only 2% urea and 20% glycerol significantly reduced sodium lauryl sulphate-induced skin irritation in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) compared with a no treatment control (NTC) and two reference creams.

Major finding: After 28 days, there was a significant reduction in transepidermal water loss with TC vs. NTC (P < .001), paraffin cream (P < .001), and glycerol cream (P = .021); objective redness was lower with TC vs. NTC (P = .002) and paraffin cream (P < .001). The TC was well tolerated with no evidence of stinging or redness.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 trial including 49 adults with AD who were randomly assigned to receive either a TC containing urea and glycerol, a glycerol-containing moisturizer, a simple paraffin cream containing no humectant, or NTC.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Perrigo Nordic. The authors declared serving as consultants, investigators, or advisory board members for and receiving research grants from several sources. Three authors declared being employees of Perrigo Nordic.

Source: Danby SG et al. Different types of emollient cream exhibit diverse physiological effects on the skin barrier in adults with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/ced.15141

Key clinical point: A 4-week treatment with a test cream (TC) containing only 2% urea and 20% glycerol significantly reduced sodium lauryl sulphate-induced skin irritation in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) compared with a no treatment control (NTC) and two reference creams.

Major finding: After 28 days, there was a significant reduction in transepidermal water loss with TC vs. NTC (P < .001), paraffin cream (P < .001), and glycerol cream (P = .021); objective redness was lower with TC vs. NTC (P = .002) and paraffin cream (P < .001). The TC was well tolerated with no evidence of stinging or redness.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 trial including 49 adults with AD who were randomly assigned to receive either a TC containing urea and glycerol, a glycerol-containing moisturizer, a simple paraffin cream containing no humectant, or NTC.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Perrigo Nordic. The authors declared serving as consultants, investigators, or advisory board members for and receiving research grants from several sources. Three authors declared being employees of Perrigo Nordic.

Source: Danby SG et al. Different types of emollient cream exhibit diverse physiological effects on the skin barrier in adults with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/ced.15141

Upadacitinib shows favorable long-term benefit-risk profile in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib showed sustained efficacy through 52 weeks in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) along with an acceptable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, a 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI75) was achieved by 82.0% and 79.1% of patients continuing 15 mg upadacitinib and 84.9% and 84.3% of patients continuing 30 mg upadacitinib in Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2, respectively. More than 80% of patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib at week 16 achieved EASI75 at week 52. No new adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a 52-week analysis of two ongoing phase 3 trials, Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2, including 1,609 adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 15 mg upadacitinib once daily, 30 mg upadacitinib, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Three authors reported ties with various sources, including AbbVie, with some receiving payments or personal fees and being employees or stockholders of AbbVie.

Source: Simpson EL et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: Analysis of follow-up data from the Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Mar 9). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib showed sustained efficacy through 52 weeks in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) along with an acceptable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, a 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI75) was achieved by 82.0% and 79.1% of patients continuing 15 mg upadacitinib and 84.9% and 84.3% of patients continuing 30 mg upadacitinib in Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2, respectively. More than 80% of patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib at week 16 achieved EASI75 at week 52. No new adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a 52-week analysis of two ongoing phase 3 trials, Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2, including 1,609 adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 15 mg upadacitinib once daily, 30 mg upadacitinib, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Three authors reported ties with various sources, including AbbVie, with some receiving payments or personal fees and being employees or stockholders of AbbVie.

Source: Simpson EL et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: Analysis of follow-up data from the Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Mar 9). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib showed sustained efficacy through 52 weeks in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) along with an acceptable safety profile.

Major finding: At week 52, a 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI75) was achieved by 82.0% and 79.1% of patients continuing 15 mg upadacitinib and 84.9% and 84.3% of patients continuing 30 mg upadacitinib in Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2, respectively. More than 80% of patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib at week 16 achieved EASI75 at week 52. No new adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a 52-week analysis of two ongoing phase 3 trials, Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2, including 1,609 adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 15 mg upadacitinib once daily, 30 mg upadacitinib, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Three authors reported ties with various sources, including AbbVie, with some receiving payments or personal fees and being employees or stockholders of AbbVie.

Source: Simpson EL et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: Analysis of follow-up data from the Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Mar 9). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029

Walking 10,000 steps a day: Desirable goal or urban myth?

Some myths never die. The idea of taking 10,000 steps a day is one of them. What started as a catchy marketing slogan has become a mantra for anyone promoting physical activity.

It all began in 1965 when the Japanese company Yamasa Tokei began selling a new step-counter which they called manpo-kei (ten-thousand steps meter). They coupled the product launch with an ad campaign – “Let’s walk 10,000 steps a day!” – in a bid to encourage physical activity. The threshold was always somewhat arbitrary, but the idea of 10,000 steps cemented itself in the public consciousness from that point forward.

To be fair, there is nothing wrong with taking 10,000 steps a day, and it does roughly correlate with the generally recommended amount of physical activity. Most people will take somewhere between 5,000 and 7,500 steps a day even if they lead largely sedentary lives. If you add 30 minutes of walking to your daily routine, that will account for an extra 3,000-4,000 steps and bring you close to that 10,000-step threshold. As such, setting a 10,000-step target is a potentially useful shorthand for people aspiring to achieve ideal levels of physical activity.

But walking fewer steps still has a benefit. A study in JAMA Network Open followed a cohort of 2,110 adults from the CARDIA study and found, rather unsurprisingly, that those with more steps per day had lower rates of all-cause mortality. But interestingly, those who averaged 7,000-10,000 steps per day did just as well as those who walked more than 10,000 steps, suggesting that the lower threshold was probably the inflection point.

Other research has shown that improving your step count is probably more important than achieving any specific threshold. In one Canadian study, patients with diabetes were randomized to usual care or to an exercise prescription from their physicians. The intervention group improved their daily step count from around 5,000 steps per day to about 6,200 steps per day. While the increase was less than the researchers had hoped for, it still resulted in improvements in blood sugar control. In another study, a 24-week walking program reduced blood pressure by 11 points in postmenopausal women, even though their increased daily step counts fell shy of the 10,000 goal at about 9,000 steps. Similarly, a small Japanese study found that enrolling postmenopausal women in a weekly exercise program helped improve their lipid profile even though they only increased their daily step count from 6,800 to 8,500 steps per day. And an analysis of U.S. NHANES data showed a mortality benefit when individuals taking more than 8,000 steps were compared with those taking fewer than 4,000 steps per day. The benefits largely plateaued beyond 9,000-10,000 steps.

The reality is that walking 10,000 steps a day is a laudable goal and is almost certainly beneficial. But even lower levels of physical activity have benefits. The trick is not so much to aim for some theoretical ideal but to improve upon your current baseline. Encouraging patients to get into the habit of taking a daily walk (be it in the morning, during lunchtime, or in the evening) is going to pay dividends regardless of their daily step count. The point is that when it comes to physical activity, the greatest benefit seems to be when we go from doing nothing to doing something.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Queen Elizabeth Health Complex, Montreal. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some myths never die. The idea of taking 10,000 steps a day is one of them. What started as a catchy marketing slogan has become a mantra for anyone promoting physical activity.

It all began in 1965 when the Japanese company Yamasa Tokei began selling a new step-counter which they called manpo-kei (ten-thousand steps meter). They coupled the product launch with an ad campaign – “Let’s walk 10,000 steps a day!” – in a bid to encourage physical activity. The threshold was always somewhat arbitrary, but the idea of 10,000 steps cemented itself in the public consciousness from that point forward.

To be fair, there is nothing wrong with taking 10,000 steps a day, and it does roughly correlate with the generally recommended amount of physical activity. Most people will take somewhere between 5,000 and 7,500 steps a day even if they lead largely sedentary lives. If you add 30 minutes of walking to your daily routine, that will account for an extra 3,000-4,000 steps and bring you close to that 10,000-step threshold. As such, setting a 10,000-step target is a potentially useful shorthand for people aspiring to achieve ideal levels of physical activity.

But walking fewer steps still has a benefit. A study in JAMA Network Open followed a cohort of 2,110 adults from the CARDIA study and found, rather unsurprisingly, that those with more steps per day had lower rates of all-cause mortality. But interestingly, those who averaged 7,000-10,000 steps per day did just as well as those who walked more than 10,000 steps, suggesting that the lower threshold was probably the inflection point.

Other research has shown that improving your step count is probably more important than achieving any specific threshold. In one Canadian study, patients with diabetes were randomized to usual care or to an exercise prescription from their physicians. The intervention group improved their daily step count from around 5,000 steps per day to about 6,200 steps per day. While the increase was less than the researchers had hoped for, it still resulted in improvements in blood sugar control. In another study, a 24-week walking program reduced blood pressure by 11 points in postmenopausal women, even though their increased daily step counts fell shy of the 10,000 goal at about 9,000 steps. Similarly, a small Japanese study found that enrolling postmenopausal women in a weekly exercise program helped improve their lipid profile even though they only increased their daily step count from 6,800 to 8,500 steps per day. And an analysis of U.S. NHANES data showed a mortality benefit when individuals taking more than 8,000 steps were compared with those taking fewer than 4,000 steps per day. The benefits largely plateaued beyond 9,000-10,000 steps.

The reality is that walking 10,000 steps a day is a laudable goal and is almost certainly beneficial. But even lower levels of physical activity have benefits. The trick is not so much to aim for some theoretical ideal but to improve upon your current baseline. Encouraging patients to get into the habit of taking a daily walk (be it in the morning, during lunchtime, or in the evening) is going to pay dividends regardless of their daily step count. The point is that when it comes to physical activity, the greatest benefit seems to be when we go from doing nothing to doing something.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Queen Elizabeth Health Complex, Montreal. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some myths never die. The idea of taking 10,000 steps a day is one of them. What started as a catchy marketing slogan has become a mantra for anyone promoting physical activity.

It all began in 1965 when the Japanese company Yamasa Tokei began selling a new step-counter which they called manpo-kei (ten-thousand steps meter). They coupled the product launch with an ad campaign – “Let’s walk 10,000 steps a day!” – in a bid to encourage physical activity. The threshold was always somewhat arbitrary, but the idea of 10,000 steps cemented itself in the public consciousness from that point forward.

To be fair, there is nothing wrong with taking 10,000 steps a day, and it does roughly correlate with the generally recommended amount of physical activity. Most people will take somewhere between 5,000 and 7,500 steps a day even if they lead largely sedentary lives. If you add 30 minutes of walking to your daily routine, that will account for an extra 3,000-4,000 steps and bring you close to that 10,000-step threshold. As such, setting a 10,000-step target is a potentially useful shorthand for people aspiring to achieve ideal levels of physical activity.

But walking fewer steps still has a benefit. A study in JAMA Network Open followed a cohort of 2,110 adults from the CARDIA study and found, rather unsurprisingly, that those with more steps per day had lower rates of all-cause mortality. But interestingly, those who averaged 7,000-10,000 steps per day did just as well as those who walked more than 10,000 steps, suggesting that the lower threshold was probably the inflection point.

Other research has shown that improving your step count is probably more important than achieving any specific threshold. In one Canadian study, patients with diabetes were randomized to usual care or to an exercise prescription from their physicians. The intervention group improved their daily step count from around 5,000 steps per day to about 6,200 steps per day. While the increase was less than the researchers had hoped for, it still resulted in improvements in blood sugar control. In another study, a 24-week walking program reduced blood pressure by 11 points in postmenopausal women, even though their increased daily step counts fell shy of the 10,000 goal at about 9,000 steps. Similarly, a small Japanese study found that enrolling postmenopausal women in a weekly exercise program helped improve their lipid profile even though they only increased their daily step count from 6,800 to 8,500 steps per day. And an analysis of U.S. NHANES data showed a mortality benefit when individuals taking more than 8,000 steps were compared with those taking fewer than 4,000 steps per day. The benefits largely plateaued beyond 9,000-10,000 steps.

The reality is that walking 10,000 steps a day is a laudable goal and is almost certainly beneficial. But even lower levels of physical activity have benefits. The trick is not so much to aim for some theoretical ideal but to improve upon your current baseline. Encouraging patients to get into the habit of taking a daily walk (be it in the morning, during lunchtime, or in the evening) is going to pay dividends regardless of their daily step count. The point is that when it comes to physical activity, the greatest benefit seems to be when we go from doing nothing to doing something.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Queen Elizabeth Health Complex, Montreal. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Common eye disorder in children tied to mental illness

Misaligned eyes in children are associated with an increased prevalence of mental illness, results of a large study suggest.

“Psychiatrists who have a patient with depression or anxiety and notice that patient also has strabismus might think about the link between those two conditions and refer that patient,” study investigator Stacy L. Pineles, MD, professor, department of ophthalmology, University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 10 in JAMA Ophthalmology.

A common condition

Strabismus, a condition in which the eyes don’t line up or are “crossed,” is one of the most common eye diseases in children, with some estimates suggesting it affects more than 1.5 million American youth.

Patients with strabismus have problems making eye contact and are affected socially and functionally, said Dr. Pineles. They’re often met with a negative bias, as shown by children’s responses to pictures of faces with and without strabismus, she said.

There is a signal from previous research suggesting that strabismus is linked to a higher risk of mental illness. However, most of these studies were small and had relatively homogenous populations, said Dr. Pineles.

The new study includes over 12 million children (mean age, 8.0 years) from a private health insurance claims database that represents diverse races and ethnicities as well as geographic regions across the United States.

The sample included 352,636 children with strabismus and 11,652,553 children with no diagnosed eye disease who served as controls. Most participants were White (51.6%), came from a family with an annual household income of $40,000 or more (51.0%), had point-of-service insurance (68.7%), and had at least one comorbid condition (64.5%).

The study evaluated five mental illness diagnoses. These included anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, substance use or addictive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Overall, children with strabismus had a higher prevalence of all these illnesses, with the exception of substance use disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, census region, education level of caregiver, family net worth, and presence of at least one comorbid condition, the odds ratios among those with versus without strabismus were: 2.01 (95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.04; P < .001) for anxiety disorder, 1.83 (95% CI, 1.76-1.90; P < .001) for schizophrenia, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.59-1.70; P < .001) for bipolar disorder, and 1.61 (95% CI, 1.59-1.63; P < .001) for depressive disorder.

Substance use disorder had a negative unadjusted association with strabismus, but after adjustment for confounders, the association was not significant (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97-1.02; P = .48).

Dr. Pineles noted that the study participants, who were all under age 19, may be too young to have substance use disorders.

The results for substance use disorders provided something of an “internal control” and reaffirmed results for the other four conditions, said Dr. Pineles.

“When you do research on such a large database, you’re very likely to find significant associations; the dataset is so large that even very small differences become statistically significant. It was interesting that not everything gave us a positive association.”

Researchers divided the strabismus group into those with esotropia, where the eyes turn inward (52.2%), exotropia, where they turn outward (46.3%), and hypertropia, where one eye wanders upward (12.5%). Investigators found that all three conditions were associated with increased risk of anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia.

Investigators note that rates in the current study were lower than in previous studies, which showed that children with congenital esotropia were 2.6 times more likely to receive a mental health diagnosis, and children with intermittent exotropia were 2.7 times more likely to receive a mental health diagnosis.

“It is probable that our study found a lower risk than these studies, because our study was cross-sectional and claims based, whereas these studies observed the children to early adulthood and were based on medical records,” the investigators note.

It’s impossible to determine from this study how strabismus is connected to mental illness. However, Dr. Pineles believes depression and anxiety might be tied to strabismus via teasing, which affects self-esteem, although genetics could also play a role. For conditions such as schizophrenia, a shared genetic link with strabismus might be more likely, she added.

“Schizophrenia is a pretty severe diagnosis, so just being teased or having poor self-esteem is probably not enough” to develop schizophrenia.

Based on her clinical experience, Dr. Pineles said that realigning the eyes of patients with milder forms of depression or anxiety “definitely anecdotally helps these patients a lot.”

Dr. Pineles and colleagues have another paper in press that examines mental illnesses and other serious eye disorders in children and shows similar findings, she said.

Implications for insurance coverage?

In an accompanying editorial, experts, led by S. Grace Prakalapakorn, MD, department of ophthalmology and pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted the exclusion of children covered under government insurance or without insurance is an important study limitation, largely because socioeconomic status is a risk factor for poor mental health.

The editorialists point to studies showing that surgical correction of ocular misalignments may be associated with reduced anxiety and depression. However, health insurance coverage for such surgical correction “may not be available owing to a misconception that these conditions are ‘cosmetic’.”

Evidence of the broader association of strabismus with physical and mental health “may play an important role in shifting policy to promote insurance coverage for timely strabismus care,” they write.

As many mental health disorders begin in childhood or adolescence, “it is paramount to identify, address, and, if possible, prevent mental health disorders at a young age, because failure to intervene in a timely fashion can have lifelong health consequences,” say Dr. Prakalapakorn and colleagues.

With mental health conditions and disorders increasing worldwide, compounded by the stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional studies are needed to explore the causal relationships between ocular and psychiatric phenomena, their treatment, and outcomes, they add.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Eye Institute and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. Dr. Pineles has reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Commentary author Manpreet K. Singh, MD, has reported receiving research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Stanford’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Johnson & Johnson, Allergan, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; serving on the advisory board for Sunovion and Skyland Trail; serving as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson; previously serving as a consultant for X, the moonshot factory, Alphabet, and Limbix Health; receiving honoraria from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; and receiving royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing and Thrive Global. Commentary author Nathan Congdon, MD, has reported receiving personal fees from Belkin Vision outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Misaligned eyes in children are associated with an increased prevalence of mental illness, results of a large study suggest.

“Psychiatrists who have a patient with depression or anxiety and notice that patient also has strabismus might think about the link between those two conditions and refer that patient,” study investigator Stacy L. Pineles, MD, professor, department of ophthalmology, University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 10 in JAMA Ophthalmology.

A common condition

Strabismus, a condition in which the eyes don’t line up or are “crossed,” is one of the most common eye diseases in children, with some estimates suggesting it affects more than 1.5 million American youth.

Patients with strabismus have problems making eye contact and are affected socially and functionally, said Dr. Pineles. They’re often met with a negative bias, as shown by children’s responses to pictures of faces with and without strabismus, she said.

There is a signal from previous research suggesting that strabismus is linked to a higher risk of mental illness. However, most of these studies were small and had relatively homogenous populations, said Dr. Pineles.

The new study includes over 12 million children (mean age, 8.0 years) from a private health insurance claims database that represents diverse races and ethnicities as well as geographic regions across the United States.

The sample included 352,636 children with strabismus and 11,652,553 children with no diagnosed eye disease who served as controls. Most participants were White (51.6%), came from a family with an annual household income of $40,000 or more (51.0%), had point-of-service insurance (68.7%), and had at least one comorbid condition (64.5%).

The study evaluated five mental illness diagnoses. These included anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, substance use or addictive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Overall, children with strabismus had a higher prevalence of all these illnesses, with the exception of substance use disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, census region, education level of caregiver, family net worth, and presence of at least one comorbid condition, the odds ratios among those with versus without strabismus were: 2.01 (95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.04; P < .001) for anxiety disorder, 1.83 (95% CI, 1.76-1.90; P < .001) for schizophrenia, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.59-1.70; P < .001) for bipolar disorder, and 1.61 (95% CI, 1.59-1.63; P < .001) for depressive disorder.

Substance use disorder had a negative unadjusted association with strabismus, but after adjustment for confounders, the association was not significant (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97-1.02; P = .48).

Dr. Pineles noted that the study participants, who were all under age 19, may be too young to have substance use disorders.

The results for substance use disorders provided something of an “internal control” and reaffirmed results for the other four conditions, said Dr. Pineles.

“When you do research on such a large database, you’re very likely to find significant associations; the dataset is so large that even very small differences become statistically significant. It was interesting that not everything gave us a positive association.”

Researchers divided the strabismus group into those with esotropia, where the eyes turn inward (52.2%), exotropia, where they turn outward (46.3%), and hypertropia, where one eye wanders upward (12.5%). Investigators found that all three conditions were associated with increased risk of anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia.

Investigators note that rates in the current study were lower than in previous studies, which showed that children with congenital esotropia were 2.6 times more likely to receive a mental health diagnosis, and children with intermittent exotropia were 2.7 times more likely to receive a mental health diagnosis.

“It is probable that our study found a lower risk than these studies, because our study was cross-sectional and claims based, whereas these studies observed the children to early adulthood and were based on medical records,” the investigators note.

It’s impossible to determine from this study how strabismus is connected to mental illness. However, Dr. Pineles believes depression and anxiety might be tied to strabismus via teasing, which affects self-esteem, although genetics could also play a role. For conditions such as schizophrenia, a shared genetic link with strabismus might be more likely, she added.

“Schizophrenia is a pretty severe diagnosis, so just being teased or having poor self-esteem is probably not enough” to develop schizophrenia.

Based on her clinical experience, Dr. Pineles said that realigning the eyes of patients with milder forms of depression or anxiety “definitely anecdotally helps these patients a lot.”

Dr. Pineles and colleagues have another paper in press that examines mental illnesses and other serious eye disorders in children and shows similar findings, she said.

Implications for insurance coverage?

In an accompanying editorial, experts, led by S. Grace Prakalapakorn, MD, department of ophthalmology and pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted the exclusion of children covered under government insurance or without insurance is an important study limitation, largely because socioeconomic status is a risk factor for poor mental health.

The editorialists point to studies showing that surgical correction of ocular misalignments may be associated with reduced anxiety and depression. However, health insurance coverage for such surgical correction “may not be available owing to a misconception that these conditions are ‘cosmetic’.”

Evidence of the broader association of strabismus with physical and mental health “may play an important role in shifting policy to promote insurance coverage for timely strabismus care,” they write.

As many mental health disorders begin in childhood or adolescence, “it is paramount to identify, address, and, if possible, prevent mental health disorders at a young age, because failure to intervene in a timely fashion can have lifelong health consequences,” say Dr. Prakalapakorn and colleagues.

With mental health conditions and disorders increasing worldwide, compounded by the stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional studies are needed to explore the causal relationships between ocular and psychiatric phenomena, their treatment, and outcomes, they add.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Eye Institute and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. Dr. Pineles has reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Commentary author Manpreet K. Singh, MD, has reported receiving research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Stanford’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Johnson & Johnson, Allergan, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; serving on the advisory board for Sunovion and Skyland Trail; serving as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson; previously serving as a consultant for X, the moonshot factory, Alphabet, and Limbix Health; receiving honoraria from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; and receiving royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing and Thrive Global. Commentary author Nathan Congdon, MD, has reported receiving personal fees from Belkin Vision outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Misaligned eyes in children are associated with an increased prevalence of mental illness, results of a large study suggest.

“Psychiatrists who have a patient with depression or anxiety and notice that patient also has strabismus might think about the link between those two conditions and refer that patient,” study investigator Stacy L. Pineles, MD, professor, department of ophthalmology, University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 10 in JAMA Ophthalmology.

A common condition

Strabismus, a condition in which the eyes don’t line up or are “crossed,” is one of the most common eye diseases in children, with some estimates suggesting it affects more than 1.5 million American youth.

Patients with strabismus have problems making eye contact and are affected socially and functionally, said Dr. Pineles. They’re often met with a negative bias, as shown by children’s responses to pictures of faces with and without strabismus, she said.

There is a signal from previous research suggesting that strabismus is linked to a higher risk of mental illness. However, most of these studies were small and had relatively homogenous populations, said Dr. Pineles.

The new study includes over 12 million children (mean age, 8.0 years) from a private health insurance claims database that represents diverse races and ethnicities as well as geographic regions across the United States.

The sample included 352,636 children with strabismus and 11,652,553 children with no diagnosed eye disease who served as controls. Most participants were White (51.6%), came from a family with an annual household income of $40,000 or more (51.0%), had point-of-service insurance (68.7%), and had at least one comorbid condition (64.5%).

The study evaluated five mental illness diagnoses. These included anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, substance use or addictive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Overall, children with strabismus had a higher prevalence of all these illnesses, with the exception of substance use disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, census region, education level of caregiver, family net worth, and presence of at least one comorbid condition, the odds ratios among those with versus without strabismus were: 2.01 (95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.04; P < .001) for anxiety disorder, 1.83 (95% CI, 1.76-1.90; P < .001) for schizophrenia, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.59-1.70; P < .001) for bipolar disorder, and 1.61 (95% CI, 1.59-1.63; P < .001) for depressive disorder.

Substance use disorder had a negative unadjusted association with strabismus, but after adjustment for confounders, the association was not significant (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97-1.02; P = .48).

Dr. Pineles noted that the study participants, who were all under age 19, may be too young to have substance use disorders.

The results for substance use disorders provided something of an “internal control” and reaffirmed results for the other four conditions, said Dr. Pineles.

“When you do research on such a large database, you’re very likely to find significant associations; the dataset is so large that even very small differences become statistically significant. It was interesting that not everything gave us a positive association.”

Researchers divided the strabismus group into those with esotropia, where the eyes turn inward (52.2%), exotropia, where they turn outward (46.3%), and hypertropia, where one eye wanders upward (12.5%). Investigators found that all three conditions were associated with increased risk of anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia.

Investigators note that rates in the current study were lower than in previous studies, which showed that children with congenital esotropia were 2.6 times more likely to receive a mental health diagnosis, and children with intermittent exotropia were 2.7 times more likely to receive a mental health diagnosis.

“It is probable that our study found a lower risk than these studies, because our study was cross-sectional and claims based, whereas these studies observed the children to early adulthood and were based on medical records,” the investigators note.

It’s impossible to determine from this study how strabismus is connected to mental illness. However, Dr. Pineles believes depression and anxiety might be tied to strabismus via teasing, which affects self-esteem, although genetics could also play a role. For conditions such as schizophrenia, a shared genetic link with strabismus might be more likely, she added.

“Schizophrenia is a pretty severe diagnosis, so just being teased or having poor self-esteem is probably not enough” to develop schizophrenia.

Based on her clinical experience, Dr. Pineles said that realigning the eyes of patients with milder forms of depression or anxiety “definitely anecdotally helps these patients a lot.”

Dr. Pineles and colleagues have another paper in press that examines mental illnesses and other serious eye disorders in children and shows similar findings, she said.

Implications for insurance coverage?

In an accompanying editorial, experts, led by S. Grace Prakalapakorn, MD, department of ophthalmology and pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted the exclusion of children covered under government insurance or without insurance is an important study limitation, largely because socioeconomic status is a risk factor for poor mental health.

The editorialists point to studies showing that surgical correction of ocular misalignments may be associated with reduced anxiety and depression. However, health insurance coverage for such surgical correction “may not be available owing to a misconception that these conditions are ‘cosmetic’.”

Evidence of the broader association of strabismus with physical and mental health “may play an important role in shifting policy to promote insurance coverage for timely strabismus care,” they write.

As many mental health disorders begin in childhood or adolescence, “it is paramount to identify, address, and, if possible, prevent mental health disorders at a young age, because failure to intervene in a timely fashion can have lifelong health consequences,” say Dr. Prakalapakorn and colleagues.

With mental health conditions and disorders increasing worldwide, compounded by the stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional studies are needed to explore the causal relationships between ocular and psychiatric phenomena, their treatment, and outcomes, they add.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Eye Institute and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. Dr. Pineles has reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Commentary author Manpreet K. Singh, MD, has reported receiving research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Stanford’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Johnson & Johnson, Allergan, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; serving on the advisory board for Sunovion and Skyland Trail; serving as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson; previously serving as a consultant for X, the moonshot factory, Alphabet, and Limbix Health; receiving honoraria from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; and receiving royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing and Thrive Global. Commentary author Nathan Congdon, MD, has reported receiving personal fees from Belkin Vision outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinical Presentation of Subacute Combined Degeneration in a Patient With Chronic B12 Deficiency

Subacute combined degeneration (SCD) is an acquired neurologic complication of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) or, rarely, vitamin B9 (folate) deficiency. SCD is characterized by progressive demyelination of the dorsal and lateral spinal cord, resulting in peripheral neuropathy; gait ataxia; impaired proprioception, vibration, and fine touch; optic neuropathy; and cognitive impairment.1 In addition to SCD, other neurologic manifestations of B12 deficiency include dementia, depression, visual symptoms due to optic atrophy, and behavioral changes.2 The prevalence of SCD in the US has not been well documented, but B12 deficiency is reported at 6% in those aged < 60 years and 20% in those > 60 years.3

Causes of B12 and B9 deficiency include advanced age, low nutritional intake (eg, vegan diet), impaired absorption (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune pernicious anemia, gastrectomy, pancreatic disease), alcohol use, tapeworm infection, medications, and high metabolic states.2,4 Impaired B12 absorption is common in patients taking medications, such as metformin and proton pump inhibitors (PPI), due to suppression of ileal membrane transport and intrinsic factor activity.5-7 B-vitamin deficiency can be exacerbated by states of increased cellular turnover, such as polycythemia vera, due to elevated DNA synthesis.

Patients may experience permanent neurologic damage when the diagnosis and treatment of SCD are missed or delayed. Early diagnosis of SCD can be challenging due to lack of specific hematologic markers. In addition, many other conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, malnutrition, toxic neuropathy, sarcoidosis, HIV, multiple sclerosis, polycythemia vera, and iron deficiency anemia have similar presentations and clinical findings.8 Anemia and/or macrocytosis are not specific to B12 deficiency.4 In addition, patients with B12 deficiency may have a normal complete blood count (CBC); those with concomitant iron deficiency may have minimal or no mean corpuscular volume (MCV) elevation.4 In patients suspected to have B12 deficiency based on clinical presentation or laboratory findings of macrocytosis, serum methylmalonic acid (MMA) can serve as a direct measure of B12 activity, with levels > 0.75 μmol/L almost always indicating cobalamin deficiency. 9 On the other hand, plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) is a sensitive marker for B12 deficiency. The active form of B12, holotranscobalamin, has also emerged as a specific measure of B12 deficiency.9 However, in patients with SCD, measurement of these markers may be unnecessary due to the severity of their clinical symptoms.

The diagnosis of SCD is further complicated because not all individuals who develop B12 or B9 deficiency will develop SCD. It is difficult to determine which patients will develop SCD because the minimum level of serum B12 required for normal function is unknown, and recent studies indicate that SCD may occur even at low-normal B12 and B9 levels.2,4,10 Commonly, a serum B12 level of < 200 pg/mL is considered deficient, while a level between 200 and 300 pg/mL is considered borderline.4 The goal level of serum B12 is > 300 pg/mL, which is considered normal.4 While serologic findings of B-vitamin deficiency are only moderately specific, radiographic findings are highly sensitive and specific for SCD. According to Briani and colleagues, the most consistent finding in SCD on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a “symmetrical, abnormally increased T2 signal intensity, commonly confined to posterior or posterior and lateral columns in the cervical and thoracic spinal cord.”2

We present a case of SCD in a patient with low-normal vitamin B12 levels who presented with progressive sensorimotor deficits and vision loss. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with SCD by radiologic workup. His course was complicated by worsening neurologic deficits despite B12 replacement. The progression of his clinical symptoms demonstrates the need for prompt, aggressive B12 replacement in patients diagnosed with SCD.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man presented for neurologic evaluation of progressive gait disturbance, paresthesia, blurred vision, and increasing falls despite use of a walker. Pertinent medical history included polycythemia vera requiring phlebotomy for approximately 9 years, alcohol use disorder (18 servings weekly), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a remote episode of transient ischemic attack (TIA). The patient reported a 5-year history of burning pain in all extremities. A prior physician diagnosis attributed the symptoms to polyneuropathy secondary to iron deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic phlebotomy for polycythemia vera and high erythrogenesis. He was prescribed gabapentin 600 mg 3 times daily for pain control. B12 deficiency was considered an unlikely etiology due to a low-normal serum level of 305 pg/mL (reference range, 190-950 pg/mL) and normocytosis, with MCV of 88 fL (reference range, 80-100 fL). The patient also reported a 3-year history of blurred vision, which was initially attributed to be secondary to diabetic retinopathy. One week prior to presenting to our clinic, he was evaluated by ophthalmology for new-onset, bilateral central visual field defects, and he was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

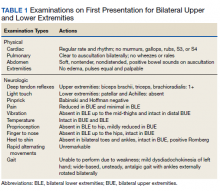

Ophthalmology suspected B12 deficiency. Notable findings included reduced deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the upper extremities and absent DTRs in the lower extremities, reduced sensation to light touch in all extremities, absent sensation to pinprick, vibration, and temperature in the lower extremities, positive Romberg sign, and a wide-based antalgic gait with the ankles externally rotated bilaterally (Table 1)

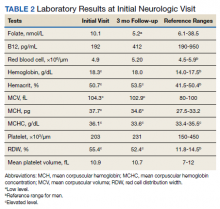

Previous cardiac evaluation failed to provide a diagnosis for syncopal episodes. MRI of the brain revealed nonspecific white matter changes consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. Electromyography was limited due to pain but showed severe peripheral neuropathy. Laboratory results showed megalocytosis, low-normal serum B12 levels, and low serum folate levels (Table 2). The patient was diagnosed with polyneuropathy and was given intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 1000 mcg once and a daily multivitamin (containing 25 mcg of B12). He was counseled on alcohol abstinence and medication adherence and was scheduled for follow-up in 3 months. He continued outpatient phlebotomy every 6 weeks for polycythemia.

At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported medication adherence, continued alcohol use, and worsening of symptoms. Falls, which now occurred 2 to 3 times weekly despite proper use of a walker, were described as sudden loss of bilateral lower extremity strength without loss of consciousness, palpitations, or other prodrome. Laboratory results showed minimal changes. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated similar deficits as on initial presentation. The patient received one additional B12 1000 mcg IM. Gabapentin was replaced with pregabalin 75 mg twice daily due to persistent uncontrolled pain and paresthesia. The patient was scheduled for a 3-month followup (6 months from initial visit) and repeat serology.

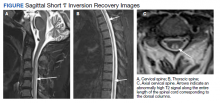

At 6-month follow-up, the patient showed continued progression of disease with significant difficulty using the walker, worsening falls, and wheelchair use required. Physical examination showed decreased sensation bilaterally up to the knees, absent bilateral patellar and Achilles reflexes, and unsteady gait. Laboratory results showed persistent subclinical B12 deficiency. MRI of the brain and spine showed high T2 signaling in a pattern highly specific for SCD. A formal diagnosis of SCD was made. The patient received an additional B12 1000 mcg IM once. Follow-up phone call with the patient 1 month later revealed no progression or improvement of symptoms.

Radiographic Findings

MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine demonstrated abnormal high T2 signal starting from C2 and extending along the course of the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (Figure). MRI in SCD classically shows symmetric, bilateral high T2 signal within the dorsal columns; on axial images, there is typically an inverted “V” sign.2,4 There can also be abnormal cerebral white matter change; however, MRI of the brain in this patient did not show any abnormalities.2 The imaging differential for this appearance includes other metabolic deficiencies/toxicities: copper deficiency; vitamin E deficiency; methotrexateinduced myelopathy, and infectious causes: HIV vacuolar myelopathy; and neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis).4

Discussion

This case demonstrates the clinical and radiographic findings of SCD and underscores the need for high-intensity dosing of B12 replacement in patients with SCD to prevent progression of the disease and development of morbidities.

Symptoms of SCD may manifest even when the vitamin levels are in low-normal levels. Its presentation is often nonspecific, thus radiologic workup is beneficial to elucidate the clinical picture. We support the use of spinal MRI in patients with clinical suspicion of SCD to help rule out other causes of myelopathy. However, an MRI is not indicated in all patients with B12 deficiency, especially those without myelopathic symptoms. Additionally, follow-up spinal MRIs are useful in monitoring the progression or improvement of SCD after B12 replacement.2 It is important to note that the MRI findings in SCD are not specific to B12 deficiency; other causes may present with similar radiographic findings.4 Therefore, radiologic findings must be correlated with a patient’s clinical presentation.

B12 replacement improves and may resolve clinical symptoms and abnormal radiographic findings of SCD. The treatment duration of B12 deficiency depends on the underlying etiology. Reversible causes, such as metformin use > 4 months, PPI use > 12 months, and dietary deficiency, require treatment until appropriate levels are reached and symptoms are resolved.4,11 The need for chronic metformin and PPI use should also be reassessed regularly. In patients who require long-term metformin use, IM administration of B12 1000 mcg annually should be considered, which will ensure adequate storage for more than 1 year.12,13 In patients who require long-term PPI use, the risk and benefits of continued use should be measured, and if needed, the lowest possible effective PPI dose is recommended.14 Irreversible causes of B12 deficiency, such as advanced age, prior gastrectomy, chronic pancreatitis, or autoimmune pernicious anemia, require lifelong supplementation of B12.4,11

In general, oral vitamin B12 replacement at 1000 to 2000 mcg daily may be as effective as parenteral replacement in patients with mild to moderate deficiency or neurologic symptoms.11 On the other hand, patients with SCD often require parenteral replacement of B12 due to the severity of their deficiency or neurologic symptoms, need for more rapid improvement in symptoms, and prevention of irreversible neurological deficits. 4,11 Appropriate B12 replacement in SCD requires intensive initial therapy which may involve IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 weeks and additional IM supplementation every 2 to 3 months afterward until resolution of deficiency.4,14 IM replacement may also be considered in patients who are nonadherent to oral replacement or have an underlying gastrointestinal condition that impairs enteral absorption.4,11

B12 deficiency is frequently undertreated and can lead to progression of disease with significant morbidity. The need for highintensity dosing of B12 replacement is crucial in patients with SCD. Failure to respond to treatment, as shown from the lack of improvement of serum markers or symptoms, likely suggests undertreatment, treatment nonadherence, iron deficiency anemia, an unidentified malabsorption syndrome, or other diagnoses. In our case, significant undertreatment, compounded by his suspected iron deficiency anemia secondary to his polycythemia vera and chronic phlebotomies, are the most likel etiologies for his lack of clinical improvement.

Multiple factors may affect the prognosis of SCD. Males aged < 50 years with absence of anemia, spinal cord atrophy, Romberg sign, Babinski sign, or sensory deficits on examination have increased likelihood of eventual recovery of signs and symptoms of SCD; those with less spinal cord involvement (< 7 cord segments), contrast enhancement, and spinal cord edema also have improved outcomes.4,15

Conclusion

SCD is a rare but serious complication of chronic vitamin B12 deficiency that presents with a variety of neurological findings and may be easily confused with other illnesses. The condition is easily overlooked or misdiagnosed; thus, it is crucial to differentiate B12 deficiency from other common causes of neurologic symptoms. Specific findings on MRI are useful to support the clinical diagnosis of SCD and guide clinical decisions. Given the prevalence of B12 deficiency in the older adult population, clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of these conditions in patients who present with progressive neuropathy. Once a patient is diagnosed with SCD secondary to a B12 deficiency, appropriate B12 replacement is critical. Appropriate B12 replacement is aggressive and involves IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by additional IM administration every 2 months before transitioning to oral therapy. As seen in this case, failure to adequately replenish B12 can lead to progression or lack of resolution of SCD symptoms.

1. Gürsoy AE, Kolukısa M, Babacan-Yıldız G, Celebi A. Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord due to Different Etiologies and Improvement of MRI Findings. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:159649. doi:10.1155/2013/159649

2. Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Citton V, et al. Cobalamin deficiency: clinical picture and radiological findings. Nutrients. 2013;5(11):4521-4539. Published 2013 Nov 15. doi:10.3390/nu5114521

3. Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ. 2014;349:g5226. Published 2014 Sep 4. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226

4. Qudsiya Z, De Jesus O. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. [Updated 2021 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK559316/

5. de Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Long term treatment with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c2181. Published 2010 May 20. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2181

6. Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB, et al. Longterm Metformin Use and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1754-1761. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-3754

7. Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2435-2442. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280490

8. Mihalj M, Titlic´ M, Bonacin D, Dogaš Z. Sensomotor axonal peripheral neuropathy as a first complication of polycythemia rubra vera: A report of 3 cases. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:385-387. Published 2013 Sep 25. doi:10.12659/AJCR.884016

9. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

10. Cao J, Xu S, Liu C. Is serum vitamin B12 decrease a necessity for the diagnosis of subacute combined degeneration?: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19700.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019700

11. Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):384-389.

12. Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):359-367. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2012.06.001

13. Mahajan R, Gupta K. Revisiting Metformin: Annual Vitamin B12 Supplementation may become Mandatory with Long-Term Metformin Use. J Young Pharm. 2010;2(4):428-429. doi:10.4103/0975-1483.71621

14. Parks NE. Metabolic and Toxic Myelopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2021;27(1):143-162. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000963

15. Vasconcelos OM, Poehm EH, McCarter RJ, Campbell WW, Quezado ZM. Potential outcome factors in subacute combined degeneration: review of observational studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1063-1068. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00525.x

Subacute combined degeneration (SCD) is an acquired neurologic complication of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) or, rarely, vitamin B9 (folate) deficiency. SCD is characterized by progressive demyelination of the dorsal and lateral spinal cord, resulting in peripheral neuropathy; gait ataxia; impaired proprioception, vibration, and fine touch; optic neuropathy; and cognitive impairment.1 In addition to SCD, other neurologic manifestations of B12 deficiency include dementia, depression, visual symptoms due to optic atrophy, and behavioral changes.2 The prevalence of SCD in the US has not been well documented, but B12 deficiency is reported at 6% in those aged < 60 years and 20% in those > 60 years.3

Causes of B12 and B9 deficiency include advanced age, low nutritional intake (eg, vegan diet), impaired absorption (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune pernicious anemia, gastrectomy, pancreatic disease), alcohol use, tapeworm infection, medications, and high metabolic states.2,4 Impaired B12 absorption is common in patients taking medications, such as metformin and proton pump inhibitors (PPI), due to suppression of ileal membrane transport and intrinsic factor activity.5-7 B-vitamin deficiency can be exacerbated by states of increased cellular turnover, such as polycythemia vera, due to elevated DNA synthesis.

Patients may experience permanent neurologic damage when the diagnosis and treatment of SCD are missed or delayed. Early diagnosis of SCD can be challenging due to lack of specific hematologic markers. In addition, many other conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, malnutrition, toxic neuropathy, sarcoidosis, HIV, multiple sclerosis, polycythemia vera, and iron deficiency anemia have similar presentations and clinical findings.8 Anemia and/or macrocytosis are not specific to B12 deficiency.4 In addition, patients with B12 deficiency may have a normal complete blood count (CBC); those with concomitant iron deficiency may have minimal or no mean corpuscular volume (MCV) elevation.4 In patients suspected to have B12 deficiency based on clinical presentation or laboratory findings of macrocytosis, serum methylmalonic acid (MMA) can serve as a direct measure of B12 activity, with levels > 0.75 μmol/L almost always indicating cobalamin deficiency. 9 On the other hand, plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) is a sensitive marker for B12 deficiency. The active form of B12, holotranscobalamin, has also emerged as a specific measure of B12 deficiency.9 However, in patients with SCD, measurement of these markers may be unnecessary due to the severity of their clinical symptoms.

The diagnosis of SCD is further complicated because not all individuals who develop B12 or B9 deficiency will develop SCD. It is difficult to determine which patients will develop SCD because the minimum level of serum B12 required for normal function is unknown, and recent studies indicate that SCD may occur even at low-normal B12 and B9 levels.2,4,10 Commonly, a serum B12 level of < 200 pg/mL is considered deficient, while a level between 200 and 300 pg/mL is considered borderline.4 The goal level of serum B12 is > 300 pg/mL, which is considered normal.4 While serologic findings of B-vitamin deficiency are only moderately specific, radiographic findings are highly sensitive and specific for SCD. According to Briani and colleagues, the most consistent finding in SCD on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a “symmetrical, abnormally increased T2 signal intensity, commonly confined to posterior or posterior and lateral columns in the cervical and thoracic spinal cord.”2

We present a case of SCD in a patient with low-normal vitamin B12 levels who presented with progressive sensorimotor deficits and vision loss. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with SCD by radiologic workup. His course was complicated by worsening neurologic deficits despite B12 replacement. The progression of his clinical symptoms demonstrates the need for prompt, aggressive B12 replacement in patients diagnosed with SCD.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man presented for neurologic evaluation of progressive gait disturbance, paresthesia, blurred vision, and increasing falls despite use of a walker. Pertinent medical history included polycythemia vera requiring phlebotomy for approximately 9 years, alcohol use disorder (18 servings weekly), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a remote episode of transient ischemic attack (TIA). The patient reported a 5-year history of burning pain in all extremities. A prior physician diagnosis attributed the symptoms to polyneuropathy secondary to iron deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic phlebotomy for polycythemia vera and high erythrogenesis. He was prescribed gabapentin 600 mg 3 times daily for pain control. B12 deficiency was considered an unlikely etiology due to a low-normal serum level of 305 pg/mL (reference range, 190-950 pg/mL) and normocytosis, with MCV of 88 fL (reference range, 80-100 fL). The patient also reported a 3-year history of blurred vision, which was initially attributed to be secondary to diabetic retinopathy. One week prior to presenting to our clinic, he was evaluated by ophthalmology for new-onset, bilateral central visual field defects, and he was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

Ophthalmology suspected B12 deficiency. Notable findings included reduced deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the upper extremities and absent DTRs in the lower extremities, reduced sensation to light touch in all extremities, absent sensation to pinprick, vibration, and temperature in the lower extremities, positive Romberg sign, and a wide-based antalgic gait with the ankles externally rotated bilaterally (Table 1)