User login

All in the family

Six female doctors from two families share their journeys through medicine.

When Annie Uhing, MD, is stressed about work, she can call her mom. She and her mom are close, yes, but her mom is also a physician and understands the ups and downs of medical education and the unique challenges of being a woman in medicine.

“My mom and I were talking about this the other day – I don’t think we know any other mother-daughter pairs of doctors,” said Dr. Uhing.

In the United States, the number of female physicians has risen steadily since the mid- and late-20th century. As of 2019, women made up more than half of medical school classes across the country and 36.3% of the physician workforce.

Still, most female physicians are concentrated in a handful of specialties (such as pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology) while the percentages of women in other areas remains extremely low (urology and orthopedic surgery). Many female physicians share anecdotal stories about not being taken seriously, like when a patient mistook them for a nurse, or preferred the advice of a male colleague to their own.

To celebrate International Women’s Day, this news organization talked to two families of female doctors about their experiences in medicine and how they inspire and support one another inside and outside the hospital.

Deborah, Charlene, and Annie

When Deborah Gaebler-Spira, MD, started medical school at the University of Illinois in 1975, women made up just 15% of her class. “For me, the idea that as a woman you could have a vocation that could be quite meaningful and self-directed – that was very important,” said Dr. Gaebler-Spira, now a pediatric rehabilitation physician at the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab and professor at Northwestern University in Chicago.

She blocked out a lot of discouragement along the way. In undergrad, the dean of the college warned Dr. Gaebler-Spira she’d never make it as a doctor. In medical school interviews, administrators could be hostile. “There was this feeling that you were taking a place of someone who really deserved it,” she said. When selecting a residency, Dr. Gaebler-Spira decided against a career in obstetrics because of the overt misogyny in the field at the time.

Instead, she went into pediatrics and physical medicine and rehabilitation, eventually working to become an expert in cerebral palsy. Along the way, Dr. Gaebler-Spira made lifelong friends with other female physicians and found strong female mentors, including Billie Adams, MD, and Helen Emery, MD.

When her sister, Charlene Gaebler-Uhing, MD, also decided to go into medicine, Dr. Gaebler-Spira said she “thought it was a sign of sanity as she was always much more competitive than I was! And if I could do it, no question she was able!”

Dr. Gaebler-Uhing, now an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee, followed her older sister’s footsteps to medical school in 1983, after first considering a career in social work.

While there were now more women going into medicine – her medical school class was about 25% women – problems persisted. During clinical rotations in residency, Dr. Gaebler-Uhing was often the only woman on a team and made the conscious decision to go professionally by her nickname, Charlie. “If a woman’s name was on the consult, her opinion and insights did not get the same value or respect as a male physician’s,” she said. “The only way they knew I was a woman was if they really knew me.”

The Gaebler sisters leaned on each other professionally and personally throughout their careers. When both sisters practiced in Chicago, they referred patients to one another. And Dr. Gaebler-Uhing said her older sister was a great role model for how to balance the dual roles of physician and parent, as few of the older female doctors who trained her were married or had a child.

Now Dr. Gaebler-Uhing’s daughter, Annie Uhing, MD, is entering medicine herself. She is currently pediatric resident at the University of Wisconsin American Family Hospital. She plans to do a chief year and then a pediatric endocrinology fellowship.

Growing up, Dr. Uhing wasn’t always sure she wanted to work as much as her parents, who are both doctors. But her mom provided a great example few of her friends had at home: “If you want to work, you should work and do what you want to do and it’s not wrong to want to have a really high-powered job as a woman,” said Dr. Uhing.

Kathryn, Susan, and Rita

The three sisters Kathryn Hudson, MD, Susan Schmidt, MD, and Rita Butler, MD, were inspired to go into medicine by their mother, Rita Watson, MD, who was one of the first female interventional cardiologists in the United States.

“I think we had a front row seat to what being a doctor was like,” said Dr. Hudson, a hematologist and oncologist and director of survivorship at Texas Oncology in Austin. Both parents were MDs – their dad was a pharmaceutical researcher at Merck – and they would excitedly discuss patient cases and drug development at the dinner table, said Dr. Butler, an interventional cardiology fellow at the Lankenau Heart Institute in Wynnewood, Pa.

All three sisters have vivid memories of ‘Take Your Daughter to Work Day’ at their mom’s hospital. “I remember going to Take Your Daughter to Work Day with her and watching her in action and thinking, oh my gosh, my mom is so cool and I want to be like her,” said Dr. Schmidt, a pediatric critical care specialist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia. “I’ve always felt special that my mom was doing something really cool and really saving lives,” said Dr. Schmidt.

Their fourth sibling, John, isn’t a physician and “I honestly wonder if it’s because he never went to Take Your Daughter to Work Day!” said Dr. Butler.

Having a mother who had both a high-powered medical career and a family helped the three women know they could do the same. “It is a difficult journey, don’t get me wrong, but I never questioned that I could do it because my mom did it first,” said Dr. Hudson.

As adults, the sisters confide in one another as they navigate modern motherhood and careers, switching between discussing medical cases and parenting advice.

As hard as their mom worked while they were growing up, she didn’t have the pressure of living up to the “super mom” ideal we have now, said Dr. Butler. “Everyone wants women to work like they don’t have kids and everyone wants women to parent like they don’t have a job,” she said. Having two sisters who can provide reassurance and advice in that area goes a long way, she said.

“I think sharing that experience of navigating motherhood, a medical career, and marriage, and adult life with sisters who are going through all the same things is really special and I feel really fortunate for that,” said Dr. Schmidt.

*This story was updated on 3/8/2022.

Six female doctors from two families share their journeys through medicine.

Six female doctors from two families share their journeys through medicine.

When Annie Uhing, MD, is stressed about work, she can call her mom. She and her mom are close, yes, but her mom is also a physician and understands the ups and downs of medical education and the unique challenges of being a woman in medicine.

“My mom and I were talking about this the other day – I don’t think we know any other mother-daughter pairs of doctors,” said Dr. Uhing.

In the United States, the number of female physicians has risen steadily since the mid- and late-20th century. As of 2019, women made up more than half of medical school classes across the country and 36.3% of the physician workforce.

Still, most female physicians are concentrated in a handful of specialties (such as pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology) while the percentages of women in other areas remains extremely low (urology and orthopedic surgery). Many female physicians share anecdotal stories about not being taken seriously, like when a patient mistook them for a nurse, or preferred the advice of a male colleague to their own.

To celebrate International Women’s Day, this news organization talked to two families of female doctors about their experiences in medicine and how they inspire and support one another inside and outside the hospital.

Deborah, Charlene, and Annie

When Deborah Gaebler-Spira, MD, started medical school at the University of Illinois in 1975, women made up just 15% of her class. “For me, the idea that as a woman you could have a vocation that could be quite meaningful and self-directed – that was very important,” said Dr. Gaebler-Spira, now a pediatric rehabilitation physician at the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab and professor at Northwestern University in Chicago.

She blocked out a lot of discouragement along the way. In undergrad, the dean of the college warned Dr. Gaebler-Spira she’d never make it as a doctor. In medical school interviews, administrators could be hostile. “There was this feeling that you were taking a place of someone who really deserved it,” she said. When selecting a residency, Dr. Gaebler-Spira decided against a career in obstetrics because of the overt misogyny in the field at the time.

Instead, she went into pediatrics and physical medicine and rehabilitation, eventually working to become an expert in cerebral palsy. Along the way, Dr. Gaebler-Spira made lifelong friends with other female physicians and found strong female mentors, including Billie Adams, MD, and Helen Emery, MD.

When her sister, Charlene Gaebler-Uhing, MD, also decided to go into medicine, Dr. Gaebler-Spira said she “thought it was a sign of sanity as she was always much more competitive than I was! And if I could do it, no question she was able!”

Dr. Gaebler-Uhing, now an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee, followed her older sister’s footsteps to medical school in 1983, after first considering a career in social work.

While there were now more women going into medicine – her medical school class was about 25% women – problems persisted. During clinical rotations in residency, Dr. Gaebler-Uhing was often the only woman on a team and made the conscious decision to go professionally by her nickname, Charlie. “If a woman’s name was on the consult, her opinion and insights did not get the same value or respect as a male physician’s,” she said. “The only way they knew I was a woman was if they really knew me.”

The Gaebler sisters leaned on each other professionally and personally throughout their careers. When both sisters practiced in Chicago, they referred patients to one another. And Dr. Gaebler-Uhing said her older sister was a great role model for how to balance the dual roles of physician and parent, as few of the older female doctors who trained her were married or had a child.

Now Dr. Gaebler-Uhing’s daughter, Annie Uhing, MD, is entering medicine herself. She is currently pediatric resident at the University of Wisconsin American Family Hospital. She plans to do a chief year and then a pediatric endocrinology fellowship.

Growing up, Dr. Uhing wasn’t always sure she wanted to work as much as her parents, who are both doctors. But her mom provided a great example few of her friends had at home: “If you want to work, you should work and do what you want to do and it’s not wrong to want to have a really high-powered job as a woman,” said Dr. Uhing.

Kathryn, Susan, and Rita

The three sisters Kathryn Hudson, MD, Susan Schmidt, MD, and Rita Butler, MD, were inspired to go into medicine by their mother, Rita Watson, MD, who was one of the first female interventional cardiologists in the United States.

“I think we had a front row seat to what being a doctor was like,” said Dr. Hudson, a hematologist and oncologist and director of survivorship at Texas Oncology in Austin. Both parents were MDs – their dad was a pharmaceutical researcher at Merck – and they would excitedly discuss patient cases and drug development at the dinner table, said Dr. Butler, an interventional cardiology fellow at the Lankenau Heart Institute in Wynnewood, Pa.

All three sisters have vivid memories of ‘Take Your Daughter to Work Day’ at their mom’s hospital. “I remember going to Take Your Daughter to Work Day with her and watching her in action and thinking, oh my gosh, my mom is so cool and I want to be like her,” said Dr. Schmidt, a pediatric critical care specialist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia. “I’ve always felt special that my mom was doing something really cool and really saving lives,” said Dr. Schmidt.

Their fourth sibling, John, isn’t a physician and “I honestly wonder if it’s because he never went to Take Your Daughter to Work Day!” said Dr. Butler.

Having a mother who had both a high-powered medical career and a family helped the three women know they could do the same. “It is a difficult journey, don’t get me wrong, but I never questioned that I could do it because my mom did it first,” said Dr. Hudson.

As adults, the sisters confide in one another as they navigate modern motherhood and careers, switching between discussing medical cases and parenting advice.

As hard as their mom worked while they were growing up, she didn’t have the pressure of living up to the “super mom” ideal we have now, said Dr. Butler. “Everyone wants women to work like they don’t have kids and everyone wants women to parent like they don’t have a job,” she said. Having two sisters who can provide reassurance and advice in that area goes a long way, she said.

“I think sharing that experience of navigating motherhood, a medical career, and marriage, and adult life with sisters who are going through all the same things is really special and I feel really fortunate for that,” said Dr. Schmidt.

*This story was updated on 3/8/2022.

When Annie Uhing, MD, is stressed about work, she can call her mom. She and her mom are close, yes, but her mom is also a physician and understands the ups and downs of medical education and the unique challenges of being a woman in medicine.

“My mom and I were talking about this the other day – I don’t think we know any other mother-daughter pairs of doctors,” said Dr. Uhing.

In the United States, the number of female physicians has risen steadily since the mid- and late-20th century. As of 2019, women made up more than half of medical school classes across the country and 36.3% of the physician workforce.

Still, most female physicians are concentrated in a handful of specialties (such as pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology) while the percentages of women in other areas remains extremely low (urology and orthopedic surgery). Many female physicians share anecdotal stories about not being taken seriously, like when a patient mistook them for a nurse, or preferred the advice of a male colleague to their own.

To celebrate International Women’s Day, this news organization talked to two families of female doctors about their experiences in medicine and how they inspire and support one another inside and outside the hospital.

Deborah, Charlene, and Annie

When Deborah Gaebler-Spira, MD, started medical school at the University of Illinois in 1975, women made up just 15% of her class. “For me, the idea that as a woman you could have a vocation that could be quite meaningful and self-directed – that was very important,” said Dr. Gaebler-Spira, now a pediatric rehabilitation physician at the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab and professor at Northwestern University in Chicago.

She blocked out a lot of discouragement along the way. In undergrad, the dean of the college warned Dr. Gaebler-Spira she’d never make it as a doctor. In medical school interviews, administrators could be hostile. “There was this feeling that you were taking a place of someone who really deserved it,” she said. When selecting a residency, Dr. Gaebler-Spira decided against a career in obstetrics because of the overt misogyny in the field at the time.

Instead, she went into pediatrics and physical medicine and rehabilitation, eventually working to become an expert in cerebral palsy. Along the way, Dr. Gaebler-Spira made lifelong friends with other female physicians and found strong female mentors, including Billie Adams, MD, and Helen Emery, MD.

When her sister, Charlene Gaebler-Uhing, MD, also decided to go into medicine, Dr. Gaebler-Spira said she “thought it was a sign of sanity as she was always much more competitive than I was! And if I could do it, no question she was able!”

Dr. Gaebler-Uhing, now an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee, followed her older sister’s footsteps to medical school in 1983, after first considering a career in social work.

While there were now more women going into medicine – her medical school class was about 25% women – problems persisted. During clinical rotations in residency, Dr. Gaebler-Uhing was often the only woman on a team and made the conscious decision to go professionally by her nickname, Charlie. “If a woman’s name was on the consult, her opinion and insights did not get the same value or respect as a male physician’s,” she said. “The only way they knew I was a woman was if they really knew me.”

The Gaebler sisters leaned on each other professionally and personally throughout their careers. When both sisters practiced in Chicago, they referred patients to one another. And Dr. Gaebler-Uhing said her older sister was a great role model for how to balance the dual roles of physician and parent, as few of the older female doctors who trained her were married or had a child.

Now Dr. Gaebler-Uhing’s daughter, Annie Uhing, MD, is entering medicine herself. She is currently pediatric resident at the University of Wisconsin American Family Hospital. She plans to do a chief year and then a pediatric endocrinology fellowship.

Growing up, Dr. Uhing wasn’t always sure she wanted to work as much as her parents, who are both doctors. But her mom provided a great example few of her friends had at home: “If you want to work, you should work and do what you want to do and it’s not wrong to want to have a really high-powered job as a woman,” said Dr. Uhing.

Kathryn, Susan, and Rita

The three sisters Kathryn Hudson, MD, Susan Schmidt, MD, and Rita Butler, MD, were inspired to go into medicine by their mother, Rita Watson, MD, who was one of the first female interventional cardiologists in the United States.

“I think we had a front row seat to what being a doctor was like,” said Dr. Hudson, a hematologist and oncologist and director of survivorship at Texas Oncology in Austin. Both parents were MDs – their dad was a pharmaceutical researcher at Merck – and they would excitedly discuss patient cases and drug development at the dinner table, said Dr. Butler, an interventional cardiology fellow at the Lankenau Heart Institute in Wynnewood, Pa.

All three sisters have vivid memories of ‘Take Your Daughter to Work Day’ at their mom’s hospital. “I remember going to Take Your Daughter to Work Day with her and watching her in action and thinking, oh my gosh, my mom is so cool and I want to be like her,” said Dr. Schmidt, a pediatric critical care specialist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia. “I’ve always felt special that my mom was doing something really cool and really saving lives,” said Dr. Schmidt.

Their fourth sibling, John, isn’t a physician and “I honestly wonder if it’s because he never went to Take Your Daughter to Work Day!” said Dr. Butler.

Having a mother who had both a high-powered medical career and a family helped the three women know they could do the same. “It is a difficult journey, don’t get me wrong, but I never questioned that I could do it because my mom did it first,” said Dr. Hudson.

As adults, the sisters confide in one another as they navigate modern motherhood and careers, switching between discussing medical cases and parenting advice.

As hard as their mom worked while they were growing up, she didn’t have the pressure of living up to the “super mom” ideal we have now, said Dr. Butler. “Everyone wants women to work like they don’t have kids and everyone wants women to parent like they don’t have a job,” she said. Having two sisters who can provide reassurance and advice in that area goes a long way, she said.

“I think sharing that experience of navigating motherhood, a medical career, and marriage, and adult life with sisters who are going through all the same things is really special and I feel really fortunate for that,” said Dr. Schmidt.

*This story was updated on 3/8/2022.

Telescoping Stents to Maintain a 3-Way Patency of the Airway

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

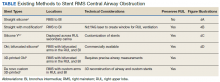

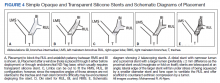

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

Impact of Lithium on Suicidality in the Veteran Population

Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States claiming nearly 48,000 individuals in 2019 and is the second leading cause of death among individuals aged 10 to 34 years.1 From 1999 to 2019, the suicide rate increased by 33%.1 In a retrospective study evaluating suicide risk in > 29,000 men, veterans had a greater risk for suicide in all age groups except for the oldest when compared with nonveterans.2 Another study of > 800,000 veterans found that younger veterans were most at risk for suicide.3 Veterans with completed suicides have a high incidence of affective disorders comorbid with substance use disorders, and therefore it is imperative to optimally treat these conditions to address suicidality.4 Additionally, a retrospective case-control study of veterans who died by suicide matched to controls identified that the cases had significantly higher rates of mental health conditions and suicidal ideation. Given that the veteran population is at higher risk of suicide, research of treatments to address suicidal ideation in veterans is needed.5

Lithium and Antisuicidal Properties

Lithium is the oldest treatment for bipolar disorder and is a long-standing first-line option due to its well-established efficacy as a mood stabilizer.6 Lithium’s antisuicidal properties separate it from the other pharmacologic options for bipolar disorder. A possible explanation for lithium’s unique antisuicidal properties is that these effects are mediated by its impact on aggression and impulsivity, which are both linked to an increased suicide risk.7,8 A meta-analysis by Baldessarini and colleagues demonstrated that patients with mood disorders who were prescribed lithium had a 5 times lower risk of suicide and attempts than did those not treated with lithium.9 Lithium’s current place in therapy is in the treatment of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder augmentation.10-12Smith and colleagues found that in a cohort study of 21,194 veterans diagnosed with mental health conditions and initiated on lithium or valproate, there were no significant differences in associations with suicide observed between these agents over 365 days; however, there was a significant increased risk of suicide among patients discontinuing or modifying lithium within the first 180 days of treatment.13

Currently, lithium is thought to be underutilized at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, based on the number of prescriptions of lithium in the large population of veterans seen by mental health clinicians. MEDVAMC is a 538-bed academic teaching hospital serving approximately 130,000 veterans in southeast Texas. The Mental Health Care Line has 73 inpatient beds and an outpatient clinic serving > 12,000 patients annually. By retrospectively evaluating changes in suicidality in a sample of veterans prescribed lithium, we may be able to better understand the role that lithium plays in a population that has a higher suicide rate than does the general population. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the change in number of suicide attempts from 3 months prior to lithium initiation to 3 months following a 6-month duration of lithium use. The secondary objective was to determine the change in suicidal ideation from the period prior to lithium use to the period following 6 months of lithium use.

Methods

This was a single-site, retrospective chart review conducted between October 2017 and April 2018. Prior to data collection, the MEDVAMC Research and Development committee approved the study as quality assurance research. Patients with an active lithium prescription were identified using the VA Lithium Lab Monitoring Dashboard, which includes all patients on lithium, their lithium level, and other data such as upcoming appointments.

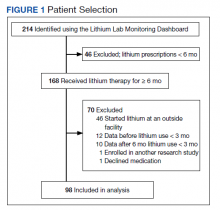

Inclusion criteria consisted of adults who were aged ≥ 18 years, had an active lithium prescription on the date of data extraction, and had an active lithium prescription for at least 6 months. Patients were excluded if they had < 3 months of data before and/or after lithium was used for 6 months, and if they were initiated on lithium outside MEDVAMC. Cumulatively, patients had to have at least 12 months of data: 3 months prior to lithium use, at least 6 months of lithium use, and 9 months after lithium initiation.

Suicide Attempt and Suicidal Ideation Identification

When determining the number of suicide attempts, we recorded 4 data points: Veterans Crisis Line notes documenting suicide attempts, hospital admissions for suicide attempts, suicide behavior reports within the indicated time frame, and mental health progress notes documenting suicide attempts. Suicidal ideation was measured in 4 ways. First, we looked at the percentage of outpatient mental health progress notes documenting suicidal ideation. Second, using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression assessments, we looked at the percentage of patients that indicated several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day to the question, “Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way.”14 Third, we recorded the percentage of suicide risk assessments that patients responded yes to both questions on current preoccupation with suicidal thoughts and serious intent and plan to commit suicide with access to guns, stashed pills, or other means. Finally, we noted the percentage of suicide risk assessments where the assessment of risk was moderate or high.

A retrospective electronic health record (EHR) review was performed and the following information was obtained: patient demographics, lithium refill history, concomitant psychotropic medications and psychotherapy, lithium levels, comorbidities at lithium initiation, presence of a high-risk suicide flag in the EHR, suicide risk assessments, suicide behavior reports, Veteran Crisis Line notes, PHQ-9 assessments, and hospital admission and mental health outpatient notes. The lithium therapeutic range of 0.6-1.2 mmol/L is indicated for bipolar disorder and not other indications where the dose is typically titrated to effect rather than level. Medication possession ratio (MPR) was also calculated for lithium (sum of days’ supply for all fills in period ÷ number of days in period). A high-risk suicide flag alerts clinicians and staff that a mental health professional considers the veteran at risk for suicide.15 Statistical analysis was performed using the paired t test for means to assess proportional differences between variables for the primary and secondary outcomes. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the baseline characteristics.

Results

A total of 214 patients with an active prescription for lithium were identified on the Lithium Lab Monitoring Dashboard on October 31, 2017. After exclusion criteria were applied, 98 patients were included in the study (Figure 1). The 2 most common reasons for exclusion were due to patients not being on lithium for at least 6 months and being initiated on lithium at an outside facility. One patient was enrolled in a lithium research study (the medication ordered was lithium/placebo) and another patient refused all psychotropic medications according to the progress notes.

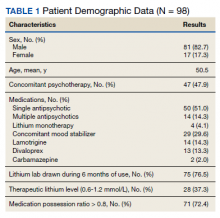

Most of the 98 patients (82.7%) were male with average age 50.5 years (Table 1). Almost half the patients (n = 47) were concomitantly participating in psychotherapy, and 50 (51.0%) patients received at least 1 antipsychotic medication. Twenty-nine patients had an active prescription for an additional mood stabilizer, and only 4 (4.1%) patients received lithium as monotherapy. Only 75 (76.5%) patients had a lithium level drawn during the 6 months of therapy, with 28 (37.3%) patients having a therapeutic lithium level (0.6 - 1.2 mmol/L). Seventy-one patients (72.4% ) were adherent to lithium therapy with a MPR > 0.8.16 Participants had 13 different psychiatric diagnoses at the time of lithium initiation; the most common were bipolar spectrum disorder (n = 38; 38.8%), depressive disorder (n = 27; 27.6%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 26; 26.5%). Of note, 5 patients had a diagnosis of only PTSD without a concomitant mood disorder.

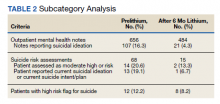

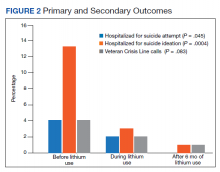

For the primary outcome, hospitalization for a suspected suicide attempt decreased from 4 (4.1%) before lithium use with a mean (SD) 0.04 (0.20) attempts per person to none within 3 months after lithium use for 6 months (t(97) = 2.03, P = .045) (Figure 2). The secondary outcome of hospitalization for suicidal ideations also decreased from 13 (13.3%) before lithium use with a mean (SD) 0.1 (0.3) ideations per person to 1 (1.0%) within 3 months after lithium use for 6 months with a mean (SD) 0.01 (0.1) ideations per person (t(97) = 3.68, P = .0004). Veteran Crisis Line calls also decreased from 4 (4.1%) with a mean (SD) 0.04 (0.2) calls per person to 1 (1.0%) within 3 months after 6 months of lithium with a mean (SD) 0.01 (0.1) calls per person (t(97) = 1.75, P = .08). The comparison of metrics from 3 months before lithium initiation and within 3 months after use saw decreases in all categories (Table 2). Outpatient notes documenting suicidal ideation decreased, as did the number of patients with a high-risk suicide flag.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest lithium may have a role in reducing suicidality in a veteran population. There was a statistically significant reduction in hospitalizations for suicide attempt and suicidal ideation after at least 6 months of lithium use. These results are comparable with a previously published study that observed significant decreases in suicidal behavior and/or hospitalization risks among veterans taking lithium compared with those not taking lithium.17 Our study was similar in respect to the reduced hospitalizations among a veteran population; however, the previous study did not report a difference in suicide attempts and lithium use. This could be related to the longer follow-up time in the previous study (3 years) vs our study (9 months).

Our study identified a significant reduction in Veteran Crisis Line calls after at least 6 months of lithium use. While a reduction in suicidal ideations could be implicated in the decrease in crisis line calls, there may be a confounding variable. It is possible that after lithium initiation, veterans had more frequent contact with health care practitioners due to laboratory test monitoring and follow-up visits and thus had concerns/crises addressed during these interactions ultimately leading to a decreased utilization of the crisis line. Interestingly, there was a reduction in mental health outpatient notes from the prelithium period to the 3-month period that followed 6 months of lithium therapy. However, our study did not report on the number of mental health outpatient notes or visits during the 6-month lithium duration. Additionally, time of year/season could have an impact on suicidality, but this relationship was not evaluated in this study.

The presence of high-risk suicide flags also decreased from the prelithium period to the period 3 months following 6 months of lithium use. High-risk flags are reviewed by the suicide prevention coordinators and mental health professionals every 90 days; therefore, the patients with flags had multiple opportunities for review and thus renewal or discontinuation during the study period. A similar rationale can be applied to the high-risk flag as with the Veteran Crisis Line reduction, although this change could also be representative of a decrease in suicidality. Our study is different from other lithium studies because it included patients with a multitude of psychiatric diagnoses rather than just mood disorders. Five of the patients had a diagnosis of only PTSD and no documented mood disorder at the time of lithium initiation. Additional research is needed on the impact of lithium on suicidality in veterans with PTSD and psychiatric conditions other than mood disorders.

Underutilization of Lithium

Despite widespread knowledge of lithium’s antisuicidal effects, it is underutilized as a mood stabilizer in the US.18 There are various modifiable barriers that impact the prescribing as well as use of lithium. Clinicians may not be fully aware of lithium’s antisuicidal properties and may also have a low level of confidence in patients’ likelihood of adherence to laboratory monitoring.18,19 Due to the narrow therapeutic index of lithium, the consequences of nonadherence to monitoring can be dangerous, which may deter mental health professionals from prescribing this antisuicidal agent. At MEDVAMC, only 72.4% of patients with a lithium prescription had a lithium level drawn within a 6-month period. This could be attributed to patient nonadherence (eg, the test was ordered but the patient did not go) or clinician nonadherence (eg, test was not ordered).

With increased clinician education as well as clinics dedicated to lithium management that allow for closer follow-up, facilities may see an increased level of comfort with lithium use. Lithium management clinics that provide close follow-up may also help address patient-related concerns about adverse effects and allow for close monitoring. To facilitate lithium monitoring at MEDVAMC, mental health practitioners and pharmacists developed a lithium test monitoring menu that serves as a “one-stop shop” for lithium baseline and ongoing test results.

In the future, we may study the impact of this test monitoring menu on lithium prescribing. One may also consider whether lithium levels need to be monitored at different frequencies (eg, less frequently for depression than bipolar disorder) depending on the diagnoses. A better understanding of the necessity for therapeutic monitoring may potentially reduce barriers to prescribing for patients who do not have indications that have a recommended therapeutic range (eg, bipolar disorder).

Lithium Adherence

A primary patient-related concern for low lithium utilization is poor adherence. In this sample, 71 patients (72.4%) were considered fully adherent. This was higher than the rate of 54.1% reported by Sajatovic and colleagues in a study evaluating adherence to lithium and other anticonvulsants in veterans with bipolar disorder.20 Patients’ beliefs about medications and overall health as well as knowledge of the illness and treatment may impact adherence.21 The literature indicates that strategies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and didactic lectures positively impact patients’ attitudes about lithium, which ultimately influences adherence.21-23 Involving a family member or significant other in psychotherapy may also improve lithium adherence.21 Specifically in the VA, to address knowledge deficits and improve overall adherence, the Lithium Lab Monitoring Dashboard could be used to identify and invite new lithium starts to educational groups about lithium. These groups could also serve as lithium management clinics.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. This was a single-site, retrospective chart review with a small sample size. We studied a cross-section of veterans with only active prescriptions, which limited the sample size. The results should be interpreted cautiously because < 40% of patients who had a level drawn were in the therapeutic range. Patients whose lithium levels were outside of the therapeutic range may have not been fully adherent to the medication. Further analysis based on reason for lithium prescription (eg, bipolar disorder vs depression vs aggression/impulsivity in PTSD) may be helpful in better understanding the results.

Additionally, while we collected data on concomitant mood stabilizers and antipsychotics, we did not collect data on concurrent antidepressant therapy and only 4% of patients were on lithium monotherapy. Data regarding veterans undergoing concurrent CBT during their lithium trial were not assessed in this study and could be considered a confounding factor for future studies. We included any Veteran Crisis Line call in our results regardless of the reason for the call, which could have led to overreporting of this suicidality marker.