User login

Do Multivitamin Supplements Lower Mortality Risk in CRC?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Some studies suggest that multivitamin supplements might increase a person’s risk for CRC, and other research indicates that certain components of multivitamins, such as vitamins C and D, may have anti-CRC properties.

- Because as many as half of CRC survivors take a multivitamin, researchers wanted to assess whether multivitamin use affects overall survival among people with CRC.

- In the current prospective cohort study, researchers evaluated the use and dose of multivitamin supplements in 2424 patients with stages I-III CRC, using detailed information from patients in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow‐Up Study.

- The participants completed a mailed questionnaire every 2 years, which included questions about the current use of multivitamin supplements as well as doses per week (0, 1-2, 3-5, 6-9, and ≥ 10 tablets).

- The researchers assessed the potential association between multivitamin use and CRC-related as well as all‐cause mortality.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over a median follow-up period of 11 years, 1512 deaths and 343 cancer-specific deaths occurred.

- For patients diagnosed with CRC, a moderate dose of multivitamins (three to five tablets per week) vs no multivitamin use was associated with a 45% lower risk for cancer-related mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.55; P = .005).

- Moderate multivitamin use was also associated with a lower risk for all-cause mortality (aHR, 0.81; P = .04) as was a higher dose of six to nine tablets per week (aHR, 0.79; P < .001).

- However, high doses of 10 or more tablets per week were associated with a 60% higher risk for cancer-related mortality (aHR, 1.60; P = .02).

IN PRACTICE:

The study findings suggested that moderate multivitamin supplement use may come with a survival benefit in patients with CRC, while high doses may not, but “further studies are needed before making clinical recommendations for multivitamin use in patients with CRC,” the authors said.

SOURCE:

This work, led by Ming‐ming He of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China, was published in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

Given the study’s observational design, residual confounding may be possible. Reverse causation and recall bias are also possible limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, American Institute for Cancer Research, Wellesley College, Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute, and the Entertainment Industry Foundation. Three study authors reported financial relationships outside this work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Some studies suggest that multivitamin supplements might increase a person’s risk for CRC, and other research indicates that certain components of multivitamins, such as vitamins C and D, may have anti-CRC properties.

- Because as many as half of CRC survivors take a multivitamin, researchers wanted to assess whether multivitamin use affects overall survival among people with CRC.

- In the current prospective cohort study, researchers evaluated the use and dose of multivitamin supplements in 2424 patients with stages I-III CRC, using detailed information from patients in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow‐Up Study.

- The participants completed a mailed questionnaire every 2 years, which included questions about the current use of multivitamin supplements as well as doses per week (0, 1-2, 3-5, 6-9, and ≥ 10 tablets).

- The researchers assessed the potential association between multivitamin use and CRC-related as well as all‐cause mortality.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over a median follow-up period of 11 years, 1512 deaths and 343 cancer-specific deaths occurred.

- For patients diagnosed with CRC, a moderate dose of multivitamins (three to five tablets per week) vs no multivitamin use was associated with a 45% lower risk for cancer-related mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.55; P = .005).

- Moderate multivitamin use was also associated with a lower risk for all-cause mortality (aHR, 0.81; P = .04) as was a higher dose of six to nine tablets per week (aHR, 0.79; P < .001).

- However, high doses of 10 or more tablets per week were associated with a 60% higher risk for cancer-related mortality (aHR, 1.60; P = .02).

IN PRACTICE:

The study findings suggested that moderate multivitamin supplement use may come with a survival benefit in patients with CRC, while high doses may not, but “further studies are needed before making clinical recommendations for multivitamin use in patients with CRC,” the authors said.

SOURCE:

This work, led by Ming‐ming He of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China, was published in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

Given the study’s observational design, residual confounding may be possible. Reverse causation and recall bias are also possible limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, American Institute for Cancer Research, Wellesley College, Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute, and the Entertainment Industry Foundation. Three study authors reported financial relationships outside this work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Some studies suggest that multivitamin supplements might increase a person’s risk for CRC, and other research indicates that certain components of multivitamins, such as vitamins C and D, may have anti-CRC properties.

- Because as many as half of CRC survivors take a multivitamin, researchers wanted to assess whether multivitamin use affects overall survival among people with CRC.

- In the current prospective cohort study, researchers evaluated the use and dose of multivitamin supplements in 2424 patients with stages I-III CRC, using detailed information from patients in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow‐Up Study.

- The participants completed a mailed questionnaire every 2 years, which included questions about the current use of multivitamin supplements as well as doses per week (0, 1-2, 3-5, 6-9, and ≥ 10 tablets).

- The researchers assessed the potential association between multivitamin use and CRC-related as well as all‐cause mortality.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over a median follow-up period of 11 years, 1512 deaths and 343 cancer-specific deaths occurred.

- For patients diagnosed with CRC, a moderate dose of multivitamins (three to five tablets per week) vs no multivitamin use was associated with a 45% lower risk for cancer-related mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.55; P = .005).

- Moderate multivitamin use was also associated with a lower risk for all-cause mortality (aHR, 0.81; P = .04) as was a higher dose of six to nine tablets per week (aHR, 0.79; P < .001).

- However, high doses of 10 or more tablets per week were associated with a 60% higher risk for cancer-related mortality (aHR, 1.60; P = .02).

IN PRACTICE:

The study findings suggested that moderate multivitamin supplement use may come with a survival benefit in patients with CRC, while high doses may not, but “further studies are needed before making clinical recommendations for multivitamin use in patients with CRC,” the authors said.

SOURCE:

This work, led by Ming‐ming He of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China, was published in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

Given the study’s observational design, residual confounding may be possible. Reverse causation and recall bias are also possible limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, American Institute for Cancer Research, Wellesley College, Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute, and the Entertainment Industry Foundation. Three study authors reported financial relationships outside this work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Diabetes Tech Falls Short as Hypoglycemic Challenges Persist

TOPLINE:

Despite diabetes technology, many with type 1 diabetes (T1D) miss glycemic targets and experience severe hypoglycemia and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia (IAH).

METHODOLOGY:

- The clinical management of T1D through technology is now recognized as the standard of care, but its real-world impact on glycemic targets and severe hypoglycemic events and IAH is unclear.

- Researchers assessed the self-reported prevalence of glycemic metrics, severe hypoglycemia, and hypoglycemia awareness according to the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and automated insulin delivery (AID) systems.

- They enrolled 2044 individuals diagnosed with T1D for at least 2 years (mean age, 43.0 years; 72.1% women; 95.4% White) from the T1D Exchange Registry and online communities who filled an online survey.

- Participants were stratified on the basis of the presence or absence of CGM and different insulin delivery methods (multiple daily injections, conventional pumps, or AID systems).

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants who achieved glycemic targets (self-reported A1c), had severe hypoglycemia (any low glucose incidence in 12 months), and/or IAH (a modified Gold score on a seven-point Likert scale).

TAKEAWAY:

- Most participants (91.7%) used CGM, and 50.8% of CGM users used an AID system.

- Despite advanced interventions, only 59.6% (95% CI, 57.3%-61.8%) of CGM users met the glycemic target (A1c < 7%), while nearly 40% of CGM users and 35.6% of AID users didn’t reach the target.

- At least one event of severe hypoglycemia in the previous 12 months was reported in 10.8% of CGM users and 16.6% of those using an AID system.

- IAH prevalence was seen in 31.1% (95% CI, 29.0%-33.2%) and 30.3% (95% CI, 17.5%-33.3%) of participants using CGM and CGM + AID, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“Educational initiatives continue to be important for all individuals with type 1 diabetes, and the development of novel therapeutic options and strategies, including bihormonal AID systems and beta-cell replacement, will be required to enable more of these individuals to meet treatment goals,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, published online in Diabetes Care, was led by Jennifer L. Sherr, MD, PhD, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

LIMITATIONS:

The survey participants in this study were from the T1D Exchange online community, who tend to be highly involved, have technology experience, and are more likely to achieve glycemic targets. The data reported as part of the survey were based on self-reports by participants and may be subject to recall bias. Notably, severe hypoglycemic events may be overreported by individuals using CGM and AID systems due to sensor alarms.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Several authors disclosed financial relationships, including grants, consulting fees, honoraria, stock ownership, and employment with pharmaceutical and device companies and other entities.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Despite diabetes technology, many with type 1 diabetes (T1D) miss glycemic targets and experience severe hypoglycemia and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia (IAH).

METHODOLOGY:

- The clinical management of T1D through technology is now recognized as the standard of care, but its real-world impact on glycemic targets and severe hypoglycemic events and IAH is unclear.

- Researchers assessed the self-reported prevalence of glycemic metrics, severe hypoglycemia, and hypoglycemia awareness according to the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and automated insulin delivery (AID) systems.

- They enrolled 2044 individuals diagnosed with T1D for at least 2 years (mean age, 43.0 years; 72.1% women; 95.4% White) from the T1D Exchange Registry and online communities who filled an online survey.

- Participants were stratified on the basis of the presence or absence of CGM and different insulin delivery methods (multiple daily injections, conventional pumps, or AID systems).

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants who achieved glycemic targets (self-reported A1c), had severe hypoglycemia (any low glucose incidence in 12 months), and/or IAH (a modified Gold score on a seven-point Likert scale).

TAKEAWAY:

- Most participants (91.7%) used CGM, and 50.8% of CGM users used an AID system.

- Despite advanced interventions, only 59.6% (95% CI, 57.3%-61.8%) of CGM users met the glycemic target (A1c < 7%), while nearly 40% of CGM users and 35.6% of AID users didn’t reach the target.

- At least one event of severe hypoglycemia in the previous 12 months was reported in 10.8% of CGM users and 16.6% of those using an AID system.

- IAH prevalence was seen in 31.1% (95% CI, 29.0%-33.2%) and 30.3% (95% CI, 17.5%-33.3%) of participants using CGM and CGM + AID, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“Educational initiatives continue to be important for all individuals with type 1 diabetes, and the development of novel therapeutic options and strategies, including bihormonal AID systems and beta-cell replacement, will be required to enable more of these individuals to meet treatment goals,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, published online in Diabetes Care, was led by Jennifer L. Sherr, MD, PhD, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

LIMITATIONS:

The survey participants in this study were from the T1D Exchange online community, who tend to be highly involved, have technology experience, and are more likely to achieve glycemic targets. The data reported as part of the survey were based on self-reports by participants and may be subject to recall bias. Notably, severe hypoglycemic events may be overreported by individuals using CGM and AID systems due to sensor alarms.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Several authors disclosed financial relationships, including grants, consulting fees, honoraria, stock ownership, and employment with pharmaceutical and device companies and other entities.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Despite diabetes technology, many with type 1 diabetes (T1D) miss glycemic targets and experience severe hypoglycemia and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia (IAH).

METHODOLOGY:

- The clinical management of T1D through technology is now recognized as the standard of care, but its real-world impact on glycemic targets and severe hypoglycemic events and IAH is unclear.

- Researchers assessed the self-reported prevalence of glycemic metrics, severe hypoglycemia, and hypoglycemia awareness according to the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and automated insulin delivery (AID) systems.

- They enrolled 2044 individuals diagnosed with T1D for at least 2 years (mean age, 43.0 years; 72.1% women; 95.4% White) from the T1D Exchange Registry and online communities who filled an online survey.

- Participants were stratified on the basis of the presence or absence of CGM and different insulin delivery methods (multiple daily injections, conventional pumps, or AID systems).

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants who achieved glycemic targets (self-reported A1c), had severe hypoglycemia (any low glucose incidence in 12 months), and/or IAH (a modified Gold score on a seven-point Likert scale).

TAKEAWAY:

- Most participants (91.7%) used CGM, and 50.8% of CGM users used an AID system.

- Despite advanced interventions, only 59.6% (95% CI, 57.3%-61.8%) of CGM users met the glycemic target (A1c < 7%), while nearly 40% of CGM users and 35.6% of AID users didn’t reach the target.

- At least one event of severe hypoglycemia in the previous 12 months was reported in 10.8% of CGM users and 16.6% of those using an AID system.

- IAH prevalence was seen in 31.1% (95% CI, 29.0%-33.2%) and 30.3% (95% CI, 17.5%-33.3%) of participants using CGM and CGM + AID, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“Educational initiatives continue to be important for all individuals with type 1 diabetes, and the development of novel therapeutic options and strategies, including bihormonal AID systems and beta-cell replacement, will be required to enable more of these individuals to meet treatment goals,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, published online in Diabetes Care, was led by Jennifer L. Sherr, MD, PhD, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

LIMITATIONS:

The survey participants in this study were from the T1D Exchange online community, who tend to be highly involved, have technology experience, and are more likely to achieve glycemic targets. The data reported as part of the survey were based on self-reports by participants and may be subject to recall bias. Notably, severe hypoglycemic events may be overreported by individuals using CGM and AID systems due to sensor alarms.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Several authors disclosed financial relationships, including grants, consulting fees, honoraria, stock ownership, and employment with pharmaceutical and device companies and other entities.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Bivalent Vaccines Protect Even Children Who’ve Had COVID

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.

But Instead of acting like a cold, it acted like nothing we had seen before, at least in our lifetime. The story of the pandemic is very much a bildungsroman of our immune systems — a story of how our immunity grew up.

The difference between the start of 2020 and now, when infections with the coronavirus remain common but not as deadly, can be measured in terms of immune education. Some of our immune systems were educated by infection, some by vaccination, and many by both.

When the first vaccines emerged in December 2020, the opportunity to educate our immune systems was still huge. Though, at the time, an estimated 20 million had been infected in the US and 350,000 had died, there was a large population that remained immunologically naive. I was one of them.

If 2020 into early 2021 was the era of immune education, the postvaccine period was the era of the variant. From one COVID strain to two, to five, to innumerable, our immune memory — trained on a specific version of the virus or its spike protein — became imperfect again. Not naive; these variants were not “novel” in the way COVID-19 was novel, but they were different. And different enough to cause infection.

Following the playbook of another virus that loves to come dressed up in different outfits, the flu virus, we find ourselves in the booster era — a world where yearly doses of a vaccine, ideally matched to the variants circulating when the vaccine is given, are the recommendation if not the norm.

But questions remain about the vaccination program, particularly around who should get it. And two populations with big question marks over their heads are (1) people who have already been infected and (2) kids, because their risk for bad outcomes is so much lower.

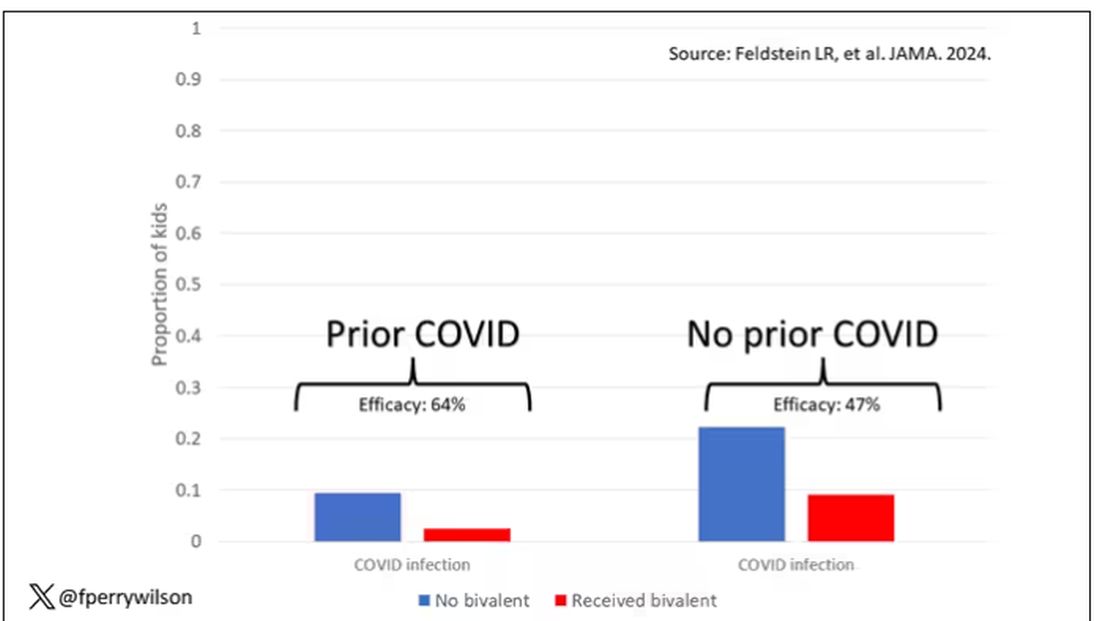

This week, we finally have some evidence that can shed light on these questions. The study under the spotlight is this one, appearing in JAMA, which tries to analyze the ability of the bivalent vaccine — that’s the second one to come out, around September 2022 — to protect kids from COVID-19.

Now, right off the bat, this was not a randomized trial. The studies that established the viability of the mRNA vaccine platform were; they happened before the vaccine was authorized. But trials of the bivalent vaccine were mostly limited to proving immune response, not protection from disease.

Nevertheless, with some good observational methods and some statistics, we can try to tease out whether bivalent vaccines in kids worked.

The study combines three prospective cohort studies. The details are in the paper, but what you need to know is that the special sauce of these studies was that the kids were tested for COVID-19 on a weekly basis, whether they had symptoms or not. This is critical because asymptomatic infections can transmit COVID-19.

Let’s do the variables of interest. First and foremost, the bivalent vaccine. Some of these kids got the bivalent vaccine, some didn’t. Other key variables include prior vaccination with the monovalent vaccine. Some had been vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine before, some hadn’t. And, of course, prior infection. Some had been infected before (based on either nasal swabs or blood tests).

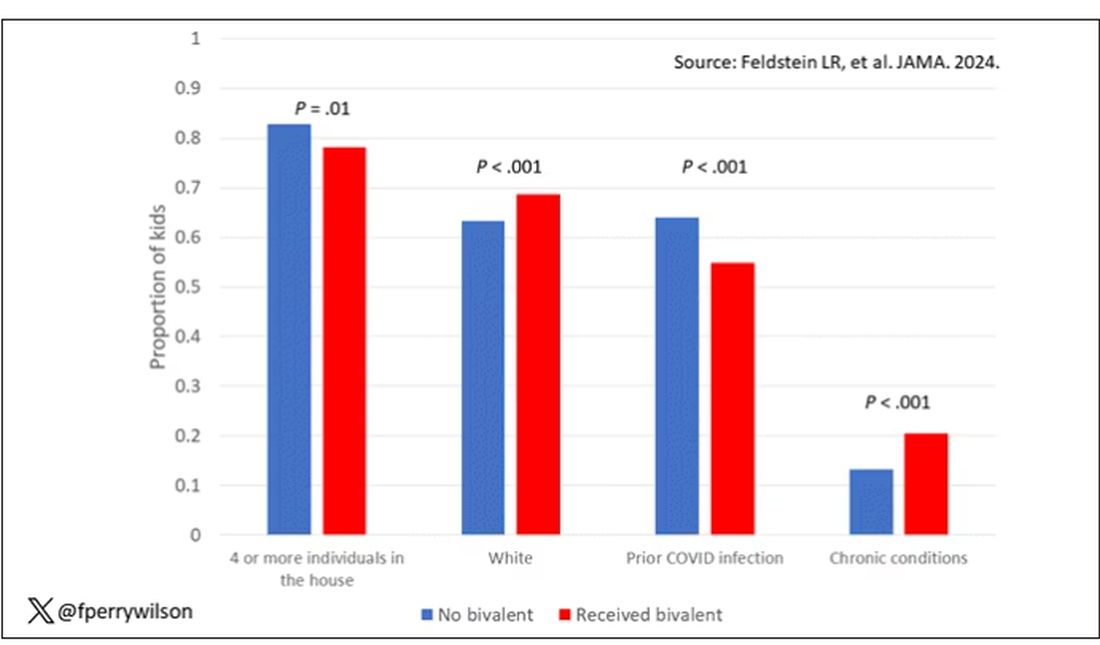

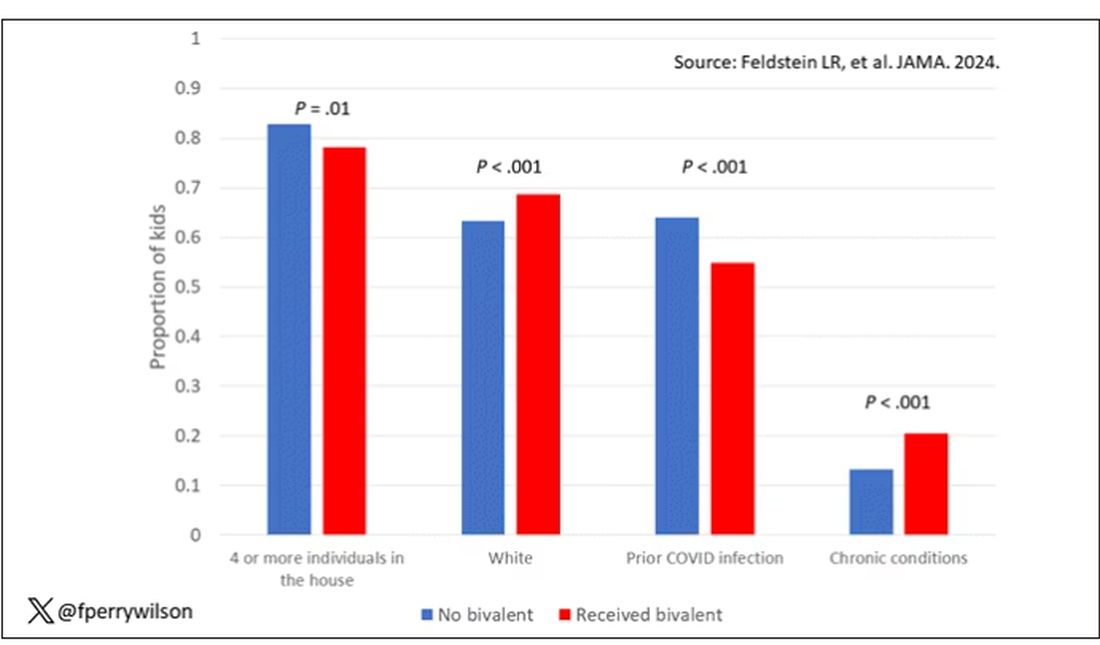

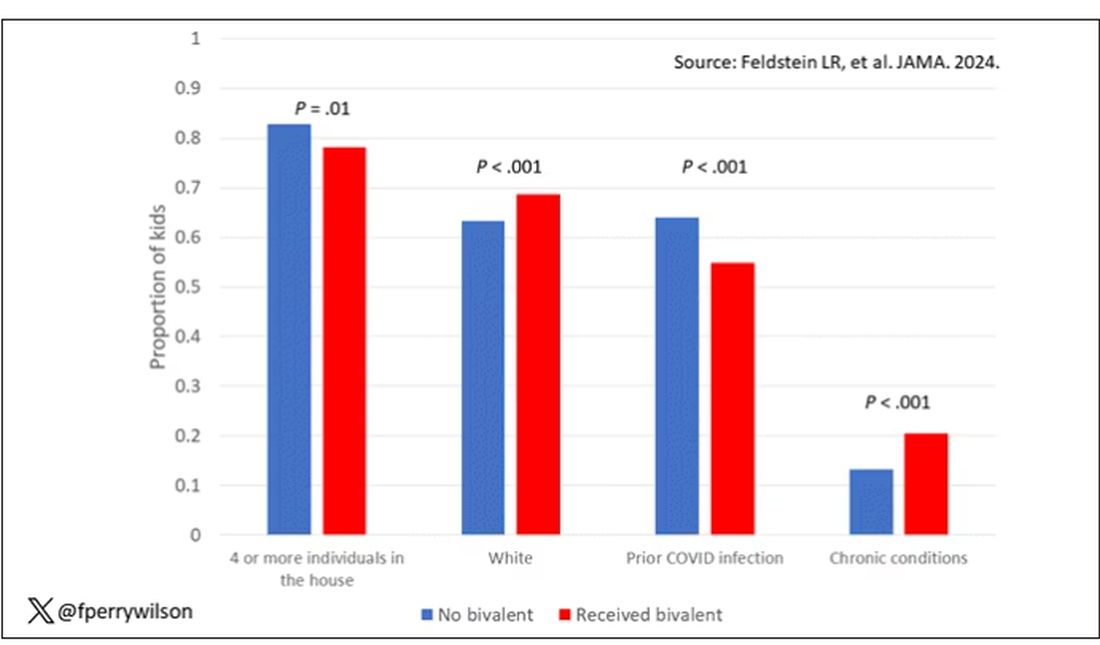

Let’s focus first on the primary exposure of interest: getting that bivalent vaccine. Again, this was not randomly assigned; kids who got the bivalent vaccine were different from those who did not. In general, they lived in smaller households, they were more likely to be White, less likely to have had a prior COVID infection, and quite a bit more likely to have at least one chronic condition.

To me, this constellation of factors describes a slightly higher-risk group; it makes sense that they were more likely to get the second vaccine.

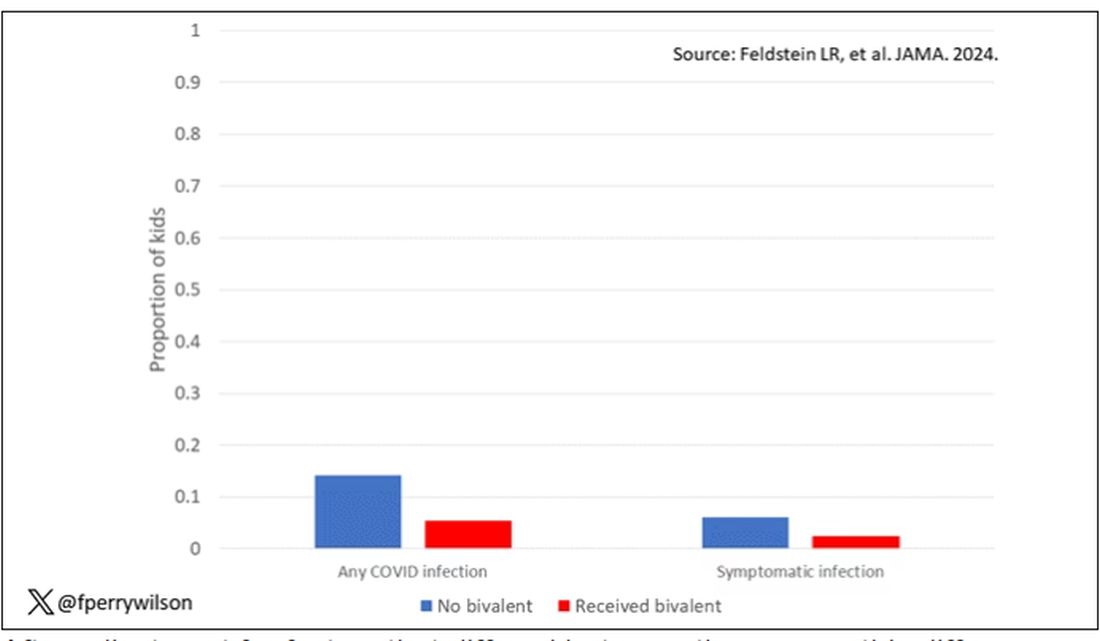

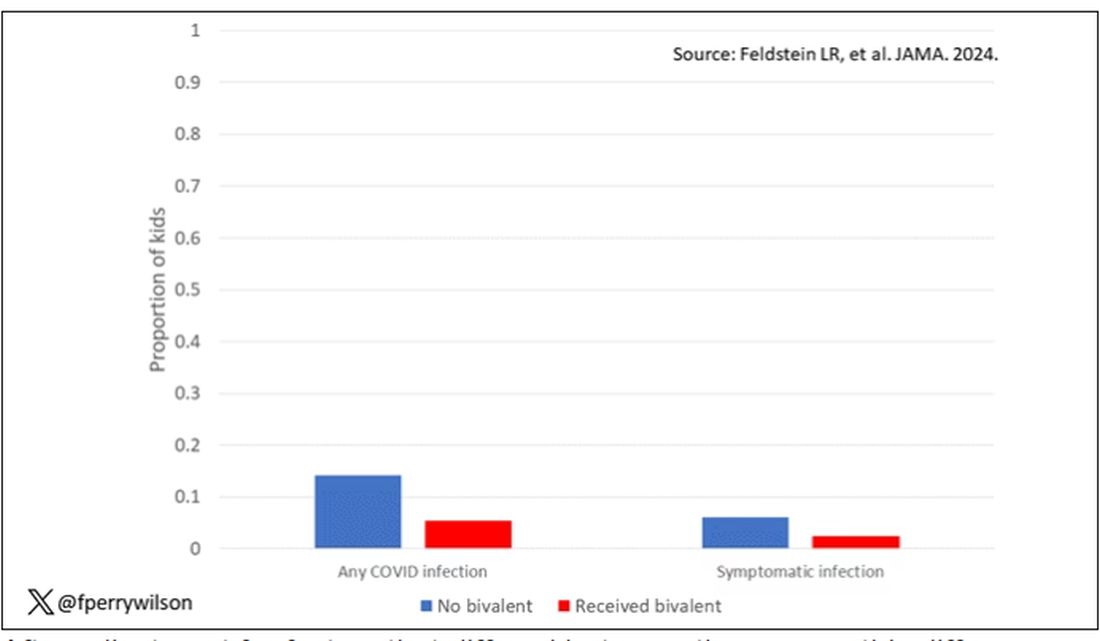

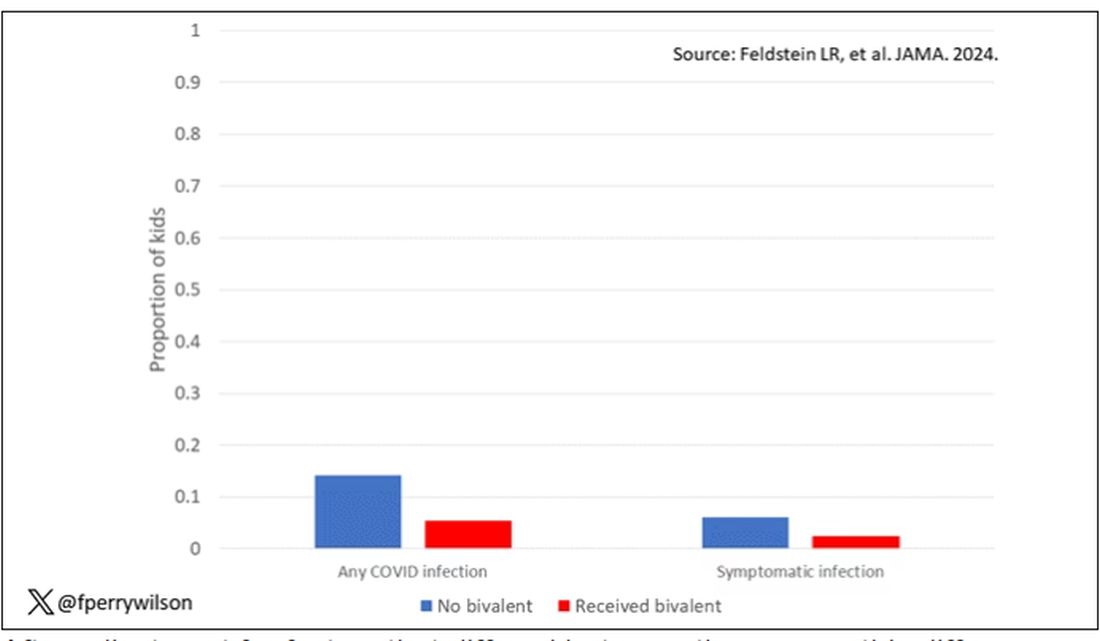

Given those factors, what were the rates of COVID infection? After nearly a year of follow-up, around 15% of the kids who hadn’t received the bivalent vaccine got infected compared with 5% of the vaccinated kids. Symptomatic infections represented roughly half of all infections in both groups.

After adjustment for factors that differed between the groups, this difference translated into a vaccine efficacy of about 50% in this population. That’s our first data point. Yes, the bivalent vaccine worked. Not amazingly, of course. But it worked.

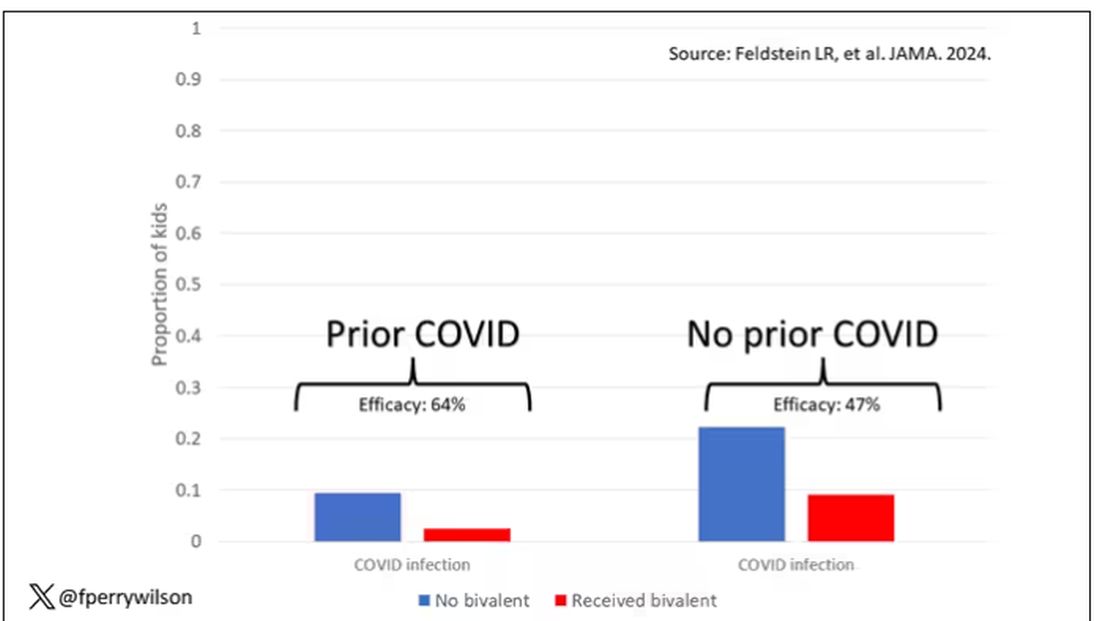

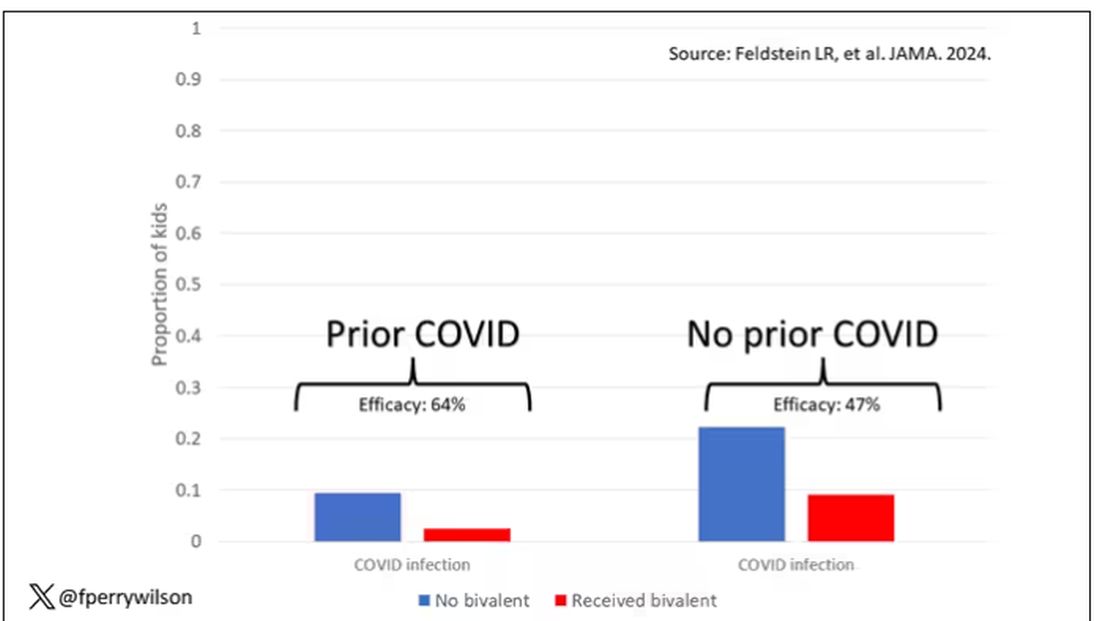

What about the kids who had had a prior COVID infection? Somewhat surprisingly, the vaccine was just as effective in this population, despite the fact that their immune systems already had some knowledge of COVID. Ten percent of unvaccinated kids got infected, even though they had been infected before. Just 2.5% of kids who received the bivalent vaccine got infected, suggesting some synergy between prior infection and vaccination.

These data suggest that the bivalent vaccine did reduce the risk for COVID infection in kids. All good. But the piece still missing is how severe these infections were. It doesn’t appear that any of the 426 infections documented in this study resulted in hospitalization or death, fortunately. And no data are presented on the incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children, though given the rarity, I’d be surprised if any of these kids have this either.

So where are we? Well, it seems that the narrative out there that says “the vaccines don’t work” or “the vaccines don’t work if you’ve already been infected” is probably not true. They do work. This study and others in adults show that. If they work to reduce infections, as this study shows, they will also work to reduce deaths. It’s just that death is fortunately so rare in children that the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death is very large. In that situation, the decision to vaccinate comes down to the risks associated with vaccination. So far, those risk seem very minimal.

Perhaps falling into a flu-like yearly vaccination schedule is not simply the result of old habits dying hard. Maybe it’s actually not a bad idea.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.

But Instead of acting like a cold, it acted like nothing we had seen before, at least in our lifetime. The story of the pandemic is very much a bildungsroman of our immune systems — a story of how our immunity grew up.

The difference between the start of 2020 and now, when infections with the coronavirus remain common but not as deadly, can be measured in terms of immune education. Some of our immune systems were educated by infection, some by vaccination, and many by both.

When the first vaccines emerged in December 2020, the opportunity to educate our immune systems was still huge. Though, at the time, an estimated 20 million had been infected in the US and 350,000 had died, there was a large population that remained immunologically naive. I was one of them.

If 2020 into early 2021 was the era of immune education, the postvaccine period was the era of the variant. From one COVID strain to two, to five, to innumerable, our immune memory — trained on a specific version of the virus or its spike protein — became imperfect again. Not naive; these variants were not “novel” in the way COVID-19 was novel, but they were different. And different enough to cause infection.

Following the playbook of another virus that loves to come dressed up in different outfits, the flu virus, we find ourselves in the booster era — a world where yearly doses of a vaccine, ideally matched to the variants circulating when the vaccine is given, are the recommendation if not the norm.

But questions remain about the vaccination program, particularly around who should get it. And two populations with big question marks over their heads are (1) people who have already been infected and (2) kids, because their risk for bad outcomes is so much lower.

This week, we finally have some evidence that can shed light on these questions. The study under the spotlight is this one, appearing in JAMA, which tries to analyze the ability of the bivalent vaccine — that’s the second one to come out, around September 2022 — to protect kids from COVID-19.

Now, right off the bat, this was not a randomized trial. The studies that established the viability of the mRNA vaccine platform were; they happened before the vaccine was authorized. But trials of the bivalent vaccine were mostly limited to proving immune response, not protection from disease.

Nevertheless, with some good observational methods and some statistics, we can try to tease out whether bivalent vaccines in kids worked.

The study combines three prospective cohort studies. The details are in the paper, but what you need to know is that the special sauce of these studies was that the kids were tested for COVID-19 on a weekly basis, whether they had symptoms or not. This is critical because asymptomatic infections can transmit COVID-19.

Let’s do the variables of interest. First and foremost, the bivalent vaccine. Some of these kids got the bivalent vaccine, some didn’t. Other key variables include prior vaccination with the monovalent vaccine. Some had been vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine before, some hadn’t. And, of course, prior infection. Some had been infected before (based on either nasal swabs or blood tests).

Let’s focus first on the primary exposure of interest: getting that bivalent vaccine. Again, this was not randomly assigned; kids who got the bivalent vaccine were different from those who did not. In general, they lived in smaller households, they were more likely to be White, less likely to have had a prior COVID infection, and quite a bit more likely to have at least one chronic condition.

To me, this constellation of factors describes a slightly higher-risk group; it makes sense that they were more likely to get the second vaccine.

Given those factors, what were the rates of COVID infection? After nearly a year of follow-up, around 15% of the kids who hadn’t received the bivalent vaccine got infected compared with 5% of the vaccinated kids. Symptomatic infections represented roughly half of all infections in both groups.

After adjustment for factors that differed between the groups, this difference translated into a vaccine efficacy of about 50% in this population. That’s our first data point. Yes, the bivalent vaccine worked. Not amazingly, of course. But it worked.

What about the kids who had had a prior COVID infection? Somewhat surprisingly, the vaccine was just as effective in this population, despite the fact that their immune systems already had some knowledge of COVID. Ten percent of unvaccinated kids got infected, even though they had been infected before. Just 2.5% of kids who received the bivalent vaccine got infected, suggesting some synergy between prior infection and vaccination.

These data suggest that the bivalent vaccine did reduce the risk for COVID infection in kids. All good. But the piece still missing is how severe these infections were. It doesn’t appear that any of the 426 infections documented in this study resulted in hospitalization or death, fortunately. And no data are presented on the incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children, though given the rarity, I’d be surprised if any of these kids have this either.

So where are we? Well, it seems that the narrative out there that says “the vaccines don’t work” or “the vaccines don’t work if you’ve already been infected” is probably not true. They do work. This study and others in adults show that. If they work to reduce infections, as this study shows, they will also work to reduce deaths. It’s just that death is fortunately so rare in children that the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death is very large. In that situation, the decision to vaccinate comes down to the risks associated with vaccination. So far, those risk seem very minimal.

Perhaps falling into a flu-like yearly vaccination schedule is not simply the result of old habits dying hard. Maybe it’s actually not a bad idea.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.

But Instead of acting like a cold, it acted like nothing we had seen before, at least in our lifetime. The story of the pandemic is very much a bildungsroman of our immune systems — a story of how our immunity grew up.

The difference between the start of 2020 and now, when infections with the coronavirus remain common but not as deadly, can be measured in terms of immune education. Some of our immune systems were educated by infection, some by vaccination, and many by both.

When the first vaccines emerged in December 2020, the opportunity to educate our immune systems was still huge. Though, at the time, an estimated 20 million had been infected in the US and 350,000 had died, there was a large population that remained immunologically naive. I was one of them.

If 2020 into early 2021 was the era of immune education, the postvaccine period was the era of the variant. From one COVID strain to two, to five, to innumerable, our immune memory — trained on a specific version of the virus or its spike protein — became imperfect again. Not naive; these variants were not “novel” in the way COVID-19 was novel, but they were different. And different enough to cause infection.

Following the playbook of another virus that loves to come dressed up in different outfits, the flu virus, we find ourselves in the booster era — a world where yearly doses of a vaccine, ideally matched to the variants circulating when the vaccine is given, are the recommendation if not the norm.

But questions remain about the vaccination program, particularly around who should get it. And two populations with big question marks over their heads are (1) people who have already been infected and (2) kids, because their risk for bad outcomes is so much lower.

This week, we finally have some evidence that can shed light on these questions. The study under the spotlight is this one, appearing in JAMA, which tries to analyze the ability of the bivalent vaccine — that’s the second one to come out, around September 2022 — to protect kids from COVID-19.

Now, right off the bat, this was not a randomized trial. The studies that established the viability of the mRNA vaccine platform were; they happened before the vaccine was authorized. But trials of the bivalent vaccine were mostly limited to proving immune response, not protection from disease.

Nevertheless, with some good observational methods and some statistics, we can try to tease out whether bivalent vaccines in kids worked.

The study combines three prospective cohort studies. The details are in the paper, but what you need to know is that the special sauce of these studies was that the kids were tested for COVID-19 on a weekly basis, whether they had symptoms or not. This is critical because asymptomatic infections can transmit COVID-19.

Let’s do the variables of interest. First and foremost, the bivalent vaccine. Some of these kids got the bivalent vaccine, some didn’t. Other key variables include prior vaccination with the monovalent vaccine. Some had been vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine before, some hadn’t. And, of course, prior infection. Some had been infected before (based on either nasal swabs or blood tests).

Let’s focus first on the primary exposure of interest: getting that bivalent vaccine. Again, this was not randomly assigned; kids who got the bivalent vaccine were different from those who did not. In general, they lived in smaller households, they were more likely to be White, less likely to have had a prior COVID infection, and quite a bit more likely to have at least one chronic condition.

To me, this constellation of factors describes a slightly higher-risk group; it makes sense that they were more likely to get the second vaccine.

Given those factors, what were the rates of COVID infection? After nearly a year of follow-up, around 15% of the kids who hadn’t received the bivalent vaccine got infected compared with 5% of the vaccinated kids. Symptomatic infections represented roughly half of all infections in both groups.

After adjustment for factors that differed between the groups, this difference translated into a vaccine efficacy of about 50% in this population. That’s our first data point. Yes, the bivalent vaccine worked. Not amazingly, of course. But it worked.

What about the kids who had had a prior COVID infection? Somewhat surprisingly, the vaccine was just as effective in this population, despite the fact that their immune systems already had some knowledge of COVID. Ten percent of unvaccinated kids got infected, even though they had been infected before. Just 2.5% of kids who received the bivalent vaccine got infected, suggesting some synergy between prior infection and vaccination.

These data suggest that the bivalent vaccine did reduce the risk for COVID infection in kids. All good. But the piece still missing is how severe these infections were. It doesn’t appear that any of the 426 infections documented in this study resulted in hospitalization or death, fortunately. And no data are presented on the incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children, though given the rarity, I’d be surprised if any of these kids have this either.

So where are we? Well, it seems that the narrative out there that says “the vaccines don’t work” or “the vaccines don’t work if you’ve already been infected” is probably not true. They do work. This study and others in adults show that. If they work to reduce infections, as this study shows, they will also work to reduce deaths. It’s just that death is fortunately so rare in children that the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death is very large. In that situation, the decision to vaccinate comes down to the risks associated with vaccination. So far, those risk seem very minimal.

Perhaps falling into a flu-like yearly vaccination schedule is not simply the result of old habits dying hard. Maybe it’s actually not a bad idea.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Premeal Stomach-Filling Capsule Effective for Weight Loss

TOPLINE:

Oral intragastric expandable capsules taken twice daily before meals reduce body weight in adults with overweight or obesity compared with placebo, with mild gastrointestinal adverse events.

METHODOLOGY:

- Numerous anti-obesity pharmacotherapies have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing weight, but they may lead to side effects.

- This 24-week phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled study evaluated 2.24 g oral intragastric expandable capsules for weight loss in 280 adults (ages 18-60 years) with overweight or obesity (body mass index ≥ 24 kg/m2).

- One capsule, taken before lunch and dinner with water, expands to fill about one quarter of average stomach volume and then passes through the body, similar to the US Food and Drug Administration–cleared device Plenity.

- Primary endpoints were the percentage change in body weight from baseline and the weight loss response rate (weight loss of at least 5% of baseline body weight) at week 24.

- Researchers analyzed efficacy outcomes in two ways: Intention to treat (a full analysis based on groups to which they were randomly assigned) and per protocol (based on data from participants who follow the protocol).

TAKEAWAY:

- At 24 weeks, the change in mean body weight was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo using the per protocol set (estimated treatment difference [ETD], −3.6%; P < .001), with similar results using the full analysis set.

- The weight loss response rate at 24 weeks was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo using the per protocol set (ETD, 29.6%; P < .001), with similar results using the full analysis set.

- Reduction in fasting insulin levels was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo (P = .008), while improvements in the lipid profile, fasting plasma glucose levels, and heart rate were similar between the groups.

- Gastrointestinal disorders were reported in 25.0% of participants in the intragastric expandable capsule group compared with 21.9% in the placebo group, with most being transient and mild in severity.

IN PRACTICE:

“As a mild and safe anti-obesity medication, intragastric expandable capsules provide a new therapeutic choice for individuals with overweight or obesity, helping them to enhance and maintain the effect of diet restriction,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

Difei Lu, MD, Department of Endocrinology, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China, led the study, which was published online in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included individuals who were overweight or obese, who might have been more willing to lose weight than the general population. Moreover, only 3.25% of the participants had type 2 diabetes, and participants were relatively young. This may have reduced the potential to discover metabolic or cardiovascular improvement by the product.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Xiamen Junde Pharmaceutical Technology. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Oral intragastric expandable capsules taken twice daily before meals reduce body weight in adults with overweight or obesity compared with placebo, with mild gastrointestinal adverse events.

METHODOLOGY:

- Numerous anti-obesity pharmacotherapies have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing weight, but they may lead to side effects.

- This 24-week phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled study evaluated 2.24 g oral intragastric expandable capsules for weight loss in 280 adults (ages 18-60 years) with overweight or obesity (body mass index ≥ 24 kg/m2).

- One capsule, taken before lunch and dinner with water, expands to fill about one quarter of average stomach volume and then passes through the body, similar to the US Food and Drug Administration–cleared device Plenity.

- Primary endpoints were the percentage change in body weight from baseline and the weight loss response rate (weight loss of at least 5% of baseline body weight) at week 24.

- Researchers analyzed efficacy outcomes in two ways: Intention to treat (a full analysis based on groups to which they were randomly assigned) and per protocol (based on data from participants who follow the protocol).

TAKEAWAY:

- At 24 weeks, the change in mean body weight was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo using the per protocol set (estimated treatment difference [ETD], −3.6%; P < .001), with similar results using the full analysis set.

- The weight loss response rate at 24 weeks was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo using the per protocol set (ETD, 29.6%; P < .001), with similar results using the full analysis set.

- Reduction in fasting insulin levels was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo (P = .008), while improvements in the lipid profile, fasting plasma glucose levels, and heart rate were similar between the groups.

- Gastrointestinal disorders were reported in 25.0% of participants in the intragastric expandable capsule group compared with 21.9% in the placebo group, with most being transient and mild in severity.

IN PRACTICE:

“As a mild and safe anti-obesity medication, intragastric expandable capsules provide a new therapeutic choice for individuals with overweight or obesity, helping them to enhance and maintain the effect of diet restriction,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

Difei Lu, MD, Department of Endocrinology, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China, led the study, which was published online in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included individuals who were overweight or obese, who might have been more willing to lose weight than the general population. Moreover, only 3.25% of the participants had type 2 diabetes, and participants were relatively young. This may have reduced the potential to discover metabolic or cardiovascular improvement by the product.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Xiamen Junde Pharmaceutical Technology. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Oral intragastric expandable capsules taken twice daily before meals reduce body weight in adults with overweight or obesity compared with placebo, with mild gastrointestinal adverse events.

METHODOLOGY:

- Numerous anti-obesity pharmacotherapies have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing weight, but they may lead to side effects.

- This 24-week phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled study evaluated 2.24 g oral intragastric expandable capsules for weight loss in 280 adults (ages 18-60 years) with overweight or obesity (body mass index ≥ 24 kg/m2).

- One capsule, taken before lunch and dinner with water, expands to fill about one quarter of average stomach volume and then passes through the body, similar to the US Food and Drug Administration–cleared device Plenity.

- Primary endpoints were the percentage change in body weight from baseline and the weight loss response rate (weight loss of at least 5% of baseline body weight) at week 24.

- Researchers analyzed efficacy outcomes in two ways: Intention to treat (a full analysis based on groups to which they were randomly assigned) and per protocol (based on data from participants who follow the protocol).

TAKEAWAY:

- At 24 weeks, the change in mean body weight was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo using the per protocol set (estimated treatment difference [ETD], −3.6%; P < .001), with similar results using the full analysis set.

- The weight loss response rate at 24 weeks was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo using the per protocol set (ETD, 29.6%; P < .001), with similar results using the full analysis set.

- Reduction in fasting insulin levels was higher with intragastric expandable capsules than with placebo (P = .008), while improvements in the lipid profile, fasting plasma glucose levels, and heart rate were similar between the groups.

- Gastrointestinal disorders were reported in 25.0% of participants in the intragastric expandable capsule group compared with 21.9% in the placebo group, with most being transient and mild in severity.

IN PRACTICE:

“As a mild and safe anti-obesity medication, intragastric expandable capsules provide a new therapeutic choice for individuals with overweight or obesity, helping them to enhance and maintain the effect of diet restriction,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

Difei Lu, MD, Department of Endocrinology, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China, led the study, which was published online in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included individuals who were overweight or obese, who might have been more willing to lose weight than the general population. Moreover, only 3.25% of the participants had type 2 diabetes, and participants were relatively young. This may have reduced the potential to discover metabolic or cardiovascular improvement by the product.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Xiamen Junde Pharmaceutical Technology. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hypertriglyceridemia in Young Adults Raises Red Flag

TOPLINE:

Persistent hypertriglyceridemia is linked to an increased risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D) in young adults, independent of lifestyle factors.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective study analyzed the data of 1,840,251 individuals aged 20-39 years from the South Korean National Health Insurance Service database (mean age 34 years, 71% male).

- The individuals had undergone four consecutive annual health checkups between 2009 and 2012 and had no history of T2D.

- The individuals were sorted into five groups indicating the number of hypertriglyceridemia diagnoses over four consecutive years: 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, defined as serum fasting triglyceride levels of 150 mg/dL or higher.

- Data on lifestyle-related risk factors, such as smoking status and heavy alcohol consumption, were collected through self-reported questionnaires.

- The primary outcome was newly diagnosed cases of T2D. Over a mean follow-up of 6.53 years, a total of 40,286 individuals developed T2D.

TAKEAWAY:

- The cumulative incidence of T2D increased with an increase in exposure scores for hypertriglyceridemia (log-rank test, P < .001), independent of lifestyle-related factors.

- The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 1.25 for participants with an exposure score of 0 and 11.55 for those with a score of 4.

- For individuals with exposure scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4, the adjusted hazard ratios for incident diabetes were 1.674 (95% CI, 1.619-1.732), 2.192 (2.117-2.269), 2.637 (2.548-2.73), and 3.715 (3.6-3.834), respectively, vs those with an exposure score of 0.

- Exploratory subgroup analyses suggested the risk for T2D in persistent hypertriglyceridemia were more pronounced among people in their 20s than in their 30s and in women.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identification of individuals at higher risk based on triglyceride levels and management strategies for persistent hypertriglyceridemia in young adults could potentially reduce the burden of young-onset type 2 diabetes and enhance long-term health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Min-Kyung Lee, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Myongji Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, was published online in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.

LIMITATIONS:

The scoring system based on fasting triglyceride levels of ≥ 150 mg/dL may have limitations, as the cumulative incidence of T2D also varied significantly for mean triglyceride levels. Moreover, relying on a single annual health checkup for hypertriglyceridemia diagnosis might not capture short-term fluctuations. Despite sufficient cases and a high follow-up rate, the study might have underestimated the incidence of T2D.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean Government and the faculty grant of Myongji Hospital. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Persistent hypertriglyceridemia is linked to an increased risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D) in young adults, independent of lifestyle factors.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective study analyzed the data of 1,840,251 individuals aged 20-39 years from the South Korean National Health Insurance Service database (mean age 34 years, 71% male).

- The individuals had undergone four consecutive annual health checkups between 2009 and 2012 and had no history of T2D.

- The individuals were sorted into five groups indicating the number of hypertriglyceridemia diagnoses over four consecutive years: 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, defined as serum fasting triglyceride levels of 150 mg/dL or higher.

- Data on lifestyle-related risk factors, such as smoking status and heavy alcohol consumption, were collected through self-reported questionnaires.

- The primary outcome was newly diagnosed cases of T2D. Over a mean follow-up of 6.53 years, a total of 40,286 individuals developed T2D.

TAKEAWAY:

- The cumulative incidence of T2D increased with an increase in exposure scores for hypertriglyceridemia (log-rank test, P < .001), independent of lifestyle-related factors.

- The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 1.25 for participants with an exposure score of 0 and 11.55 for those with a score of 4.

- For individuals with exposure scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4, the adjusted hazard ratios for incident diabetes were 1.674 (95% CI, 1.619-1.732), 2.192 (2.117-2.269), 2.637 (2.548-2.73), and 3.715 (3.6-3.834), respectively, vs those with an exposure score of 0.

- Exploratory subgroup analyses suggested the risk for T2D in persistent hypertriglyceridemia were more pronounced among people in their 20s than in their 30s and in women.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identification of individuals at higher risk based on triglyceride levels and management strategies for persistent hypertriglyceridemia in young adults could potentially reduce the burden of young-onset type 2 diabetes and enhance long-term health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Min-Kyung Lee, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Myongji Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, was published online in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.

LIMITATIONS:

The scoring system based on fasting triglyceride levels of ≥ 150 mg/dL may have limitations, as the cumulative incidence of T2D also varied significantly for mean triglyceride levels. Moreover, relying on a single annual health checkup for hypertriglyceridemia diagnosis might not capture short-term fluctuations. Despite sufficient cases and a high follow-up rate, the study might have underestimated the incidence of T2D.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean Government and the faculty grant of Myongji Hospital. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Persistent hypertriglyceridemia is linked to an increased risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D) in young adults, independent of lifestyle factors.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective study analyzed the data of 1,840,251 individuals aged 20-39 years from the South Korean National Health Insurance Service database (mean age 34 years, 71% male).

- The individuals had undergone four consecutive annual health checkups between 2009 and 2012 and had no history of T2D.

- The individuals were sorted into five groups indicating the number of hypertriglyceridemia diagnoses over four consecutive years: 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, defined as serum fasting triglyceride levels of 150 mg/dL or higher.

- Data on lifestyle-related risk factors, such as smoking status and heavy alcohol consumption, were collected through self-reported questionnaires.

- The primary outcome was newly diagnosed cases of T2D. Over a mean follow-up of 6.53 years, a total of 40,286 individuals developed T2D.

TAKEAWAY:

- The cumulative incidence of T2D increased with an increase in exposure scores for hypertriglyceridemia (log-rank test, P < .001), independent of lifestyle-related factors.

- The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 1.25 for participants with an exposure score of 0 and 11.55 for those with a score of 4.

- For individuals with exposure scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4, the adjusted hazard ratios for incident diabetes were 1.674 (95% CI, 1.619-1.732), 2.192 (2.117-2.269), 2.637 (2.548-2.73), and 3.715 (3.6-3.834), respectively, vs those with an exposure score of 0.

- Exploratory subgroup analyses suggested the risk for T2D in persistent hypertriglyceridemia were more pronounced among people in their 20s than in their 30s and in women.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identification of individuals at higher risk based on triglyceride levels and management strategies for persistent hypertriglyceridemia in young adults could potentially reduce the burden of young-onset type 2 diabetes and enhance long-term health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Min-Kyung Lee, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Myongji Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, was published online in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.

LIMITATIONS:

The scoring system based on fasting triglyceride levels of ≥ 150 mg/dL may have limitations, as the cumulative incidence of T2D also varied significantly for mean triglyceride levels. Moreover, relying on a single annual health checkup for hypertriglyceridemia diagnosis might not capture short-term fluctuations. Despite sufficient cases and a high follow-up rate, the study might have underestimated the incidence of T2D.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean Government and the faculty grant of Myongji Hospital. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How the New MRSA Antibiotic Cracked AI’s ‘Black Box’

“New antibiotics discovered using AI!”

That’s how headlines read in December 2023, when MIT researchers announced a new class of antibiotics that could wipe out the drug-resistant superbug methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in mice.

Powered by deep learning, the study was a significant breakthrough. Few new antibiotics have come out since the 1960s, and this one in particular could be crucial in fighting tough-to-treat MRSA, which kills more than 10,000 people annually in the United States.

But as remarkable as the antibiotic discovery was, it may not be the most impactful part of this study.

“Of course, we view the antibiotic-discovery angle to be very important,” said Felix Wong, PhD, a colead author of the study and postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts. “But I think equally important, or maybe even more important, is really our method of opening up the black box.”

The black box is generally thought of as impenetrable in complex machine learning models, and that poses a challenge in the drug discovery realm.

“A major bottleneck in AI-ML-driven drug discovery is that nobody knows what the heck is going on,” said Dr. Wong. Models have such powerful architectures that their decision-making is mysterious.

Researchers input data, such as patient features, and the model says what drugs might be effective. But researchers have no idea how the model arrived at its predictions — until now.

What the Researchers Did

Dr. Wong and his colleagues first mined 39,000 compounds for antibiotic activity against MRSA. They fed information about the compounds’ chemical structures and antibiotic activity into their machine learning model. With this, they “trained” the model to predict whether a compound is antibacterial.

Next, they used additional deep learning to narrow the field, ruling out compounds toxic to humans. Then, deploying their various models at once, they screened 12 million commercially available compounds. Five classes emerged as likely MRSA fighters. Further testing of 280 compounds from the five classes produced the final results: Two compounds from the same class. Both reduced MRSA infection in mouse models.

How did the computer flag these compounds? The researchers sought to answer that question by figuring out which chemical structures the model had been looking for.

A chemical structure can be “pruned” — that is, scientists can remove certain atoms and bonds to reveal an underlying substructure. The MIT researchers used the Monte Carlo Tree Search, a commonly used algorithm in machine learning, to select which atoms and bonds to edit out. Then they fed the pruned substructures into their model to find out which was likely responsible for the antibacterial activity.

“The main idea is we can pinpoint which substructure of a chemical structure is causative instead of just correlated with high antibiotic activity,” Dr. Wong said.

This could fuel new “design-driven” or generative AI approaches where these substructures become “starting points to design entirely unseen, unprecedented antibiotics,” Dr. Wong said. “That’s one of the key efforts that we’ve been working on since the publication of this paper.”

More broadly, their method could lead to discoveries in drug classes beyond antibiotics, such as antivirals and anticancer drugs, according to Dr. Wong.

“This is the first major study that I’ve seen seeking to incorporate explainability into deep learning models in the context of antibiotics,” said César de la Fuente, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, whose lab has been engaged in AI for antibiotic discovery for the past 5 years.

“It’s kind of like going into the black box with a magnifying lens and figuring out what is actually happening in there,” Dr. de la Fuente said. “And that will open up possibilities for leveraging those different steps to make better drugs.”

How Explainable AI Could Revolutionize Medicine

In studies, explainable AI is showing its potential for informing clinical decisions as well — flagging high-risk patients and letting doctors know why that calculation was made. University of Washington researchers have used the technology to predict whether a patient will have hypoxemia during surgery, revealing which features contributed to the prediction, such as blood pressure or body mass index. Another study used explainable AI to help emergency medical services providers and emergency room clinicians optimize time — for example, by identifying trauma patients at high risk for acute traumatic coagulopathy more quickly.

A crucial benefit of explainable AI is its ability to audit machine learning models for mistakes, said Su-In Lee, PhD, a computer scientist who led the UW research.

For example, a surge of research during the pandemic suggested that AI models could predict COVID-19 infection based on chest x-rays. Dr. Lee’s research used explainable AI to show that many of the studies were not as accurate as they claimed. Her lab revealed that many models› decisions were based not on pathologies but rather on other aspects such as laterality markers in the corners of x-rays or medical devices worn by patients (like pacemakers). She applied the same model auditing technique to AI-powered dermatology devices, digging into the flawed reasoning in their melanoma predictions.

Explainable AI is beginning to affect drug development too. A 2023 study led by Dr. Lee used it to explain how to select complementary drugs for acute myeloid leukemia patients based on the differentiation levels of cancer cells. And in two other studies aimed at identifying Alzheimer’s therapeutic targets, “explainable AI played a key role in terms of identifying the driver pathway,” she said.

Currently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval doesn’t require an understanding of a drug’s mechanism of action. But the issue is being raised more often, including at December’s Health Regulatory Policy Conference at MIT’s Jameel Clinic. And just over a year ago, Dr. Lee predicted that the FDA approval process would come to incorporate explainable AI analysis.

“I didn’t hesitate,” Dr. Lee said, regarding her prediction. “We didn’t see this in 2023, so I won’t assert that I was right, but I can confidently say that we are progressing in that direction.”

What’s Next?

The MIT study is part of the Antibiotics-AI project, a 7-year effort to leverage AI to find new antibiotics. Phare Bio, a nonprofit started by MIT professor James Collins, PhD, and others, will do clinical testing on the antibiotic candidates.

Even with the AI’s assistance, there’s still a long way to go before clinical approval.

But knowing which elements contribute to a candidate’s effectiveness against MRSA could help the researchers formulate scientific hypotheses and design better validation, Dr. Lee noted. In other words, because they used explainable AI, they could be better positioned for clinical trial success.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“New antibiotics discovered using AI!”

That’s how headlines read in December 2023, when MIT researchers announced a new class of antibiotics that could wipe out the drug-resistant superbug methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in mice.

Powered by deep learning, the study was a significant breakthrough. Few new antibiotics have come out since the 1960s, and this one in particular could be crucial in fighting tough-to-treat MRSA, which kills more than 10,000 people annually in the United States.

But as remarkable as the antibiotic discovery was, it may not be the most impactful part of this study.

“Of course, we view the antibiotic-discovery angle to be very important,” said Felix Wong, PhD, a colead author of the study and postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts. “But I think equally important, or maybe even more important, is really our method of opening up the black box.”

The black box is generally thought of as impenetrable in complex machine learning models, and that poses a challenge in the drug discovery realm.

“A major bottleneck in AI-ML-driven drug discovery is that nobody knows what the heck is going on,” said Dr. Wong. Models have such powerful architectures that their decision-making is mysterious.

Researchers input data, such as patient features, and the model says what drugs might be effective. But researchers have no idea how the model arrived at its predictions — until now.

What the Researchers Did

Dr. Wong and his colleagues first mined 39,000 compounds for antibiotic activity against MRSA. They fed information about the compounds’ chemical structures and antibiotic activity into their machine learning model. With this, they “trained” the model to predict whether a compound is antibacterial.

Next, they used additional deep learning to narrow the field, ruling out compounds toxic to humans. Then, deploying their various models at once, they screened 12 million commercially available compounds. Five classes emerged as likely MRSA fighters. Further testing of 280 compounds from the five classes produced the final results: Two compounds from the same class. Both reduced MRSA infection in mouse models.

How did the computer flag these compounds? The researchers sought to answer that question by figuring out which chemical structures the model had been looking for.

A chemical structure can be “pruned” — that is, scientists can remove certain atoms and bonds to reveal an underlying substructure. The MIT researchers used the Monte Carlo Tree Search, a commonly used algorithm in machine learning, to select which atoms and bonds to edit out. Then they fed the pruned substructures into their model to find out which was likely responsible for the antibacterial activity.

“The main idea is we can pinpoint which substructure of a chemical structure is causative instead of just correlated with high antibiotic activity,” Dr. Wong said.

This could fuel new “design-driven” or generative AI approaches where these substructures become “starting points to design entirely unseen, unprecedented antibiotics,” Dr. Wong said. “That’s one of the key efforts that we’ve been working on since the publication of this paper.”

More broadly, their method could lead to discoveries in drug classes beyond antibiotics, such as antivirals and anticancer drugs, according to Dr. Wong.

“This is the first major study that I’ve seen seeking to incorporate explainability into deep learning models in the context of antibiotics,” said César de la Fuente, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, whose lab has been engaged in AI for antibiotic discovery for the past 5 years.

“It’s kind of like going into the black box with a magnifying lens and figuring out what is actually happening in there,” Dr. de la Fuente said. “And that will open up possibilities for leveraging those different steps to make better drugs.”

How Explainable AI Could Revolutionize Medicine

In studies, explainable AI is showing its potential for informing clinical decisions as well — flagging high-risk patients and letting doctors know why that calculation was made. University of Washington researchers have used the technology to predict whether a patient will have hypoxemia during surgery, revealing which features contributed to the prediction, such as blood pressure or body mass index. Another study used explainable AI to help emergency medical services providers and emergency room clinicians optimize time — for example, by identifying trauma patients at high risk for acute traumatic coagulopathy more quickly.

A crucial benefit of explainable AI is its ability to audit machine learning models for mistakes, said Su-In Lee, PhD, a computer scientist who led the UW research.

For example, a surge of research during the pandemic suggested that AI models could predict COVID-19 infection based on chest x-rays. Dr. Lee’s research used explainable AI to show that many of the studies were not as accurate as they claimed. Her lab revealed that many models› decisions were based not on pathologies but rather on other aspects such as laterality markers in the corners of x-rays or medical devices worn by patients (like pacemakers). She applied the same model auditing technique to AI-powered dermatology devices, digging into the flawed reasoning in their melanoma predictions.

Explainable AI is beginning to affect drug development too. A 2023 study led by Dr. Lee used it to explain how to select complementary drugs for acute myeloid leukemia patients based on the differentiation levels of cancer cells. And in two other studies aimed at identifying Alzheimer’s therapeutic targets, “explainable AI played a key role in terms of identifying the driver pathway,” she said.

Currently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval doesn’t require an understanding of a drug’s mechanism of action. But the issue is being raised more often, including at December’s Health Regulatory Policy Conference at MIT’s Jameel Clinic. And just over a year ago, Dr. Lee predicted that the FDA approval process would come to incorporate explainable AI analysis.

“I didn’t hesitate,” Dr. Lee said, regarding her prediction. “We didn’t see this in 2023, so I won’t assert that I was right, but I can confidently say that we are progressing in that direction.”

What’s Next?

The MIT study is part of the Antibiotics-AI project, a 7-year effort to leverage AI to find new antibiotics. Phare Bio, a nonprofit started by MIT professor James Collins, PhD, and others, will do clinical testing on the antibiotic candidates.

Even with the AI’s assistance, there’s still a long way to go before clinical approval.

But knowing which elements contribute to a candidate’s effectiveness against MRSA could help the researchers formulate scientific hypotheses and design better validation, Dr. Lee noted. In other words, because they used explainable AI, they could be better positioned for clinical trial success.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“New antibiotics discovered using AI!”

That’s how headlines read in December 2023, when MIT researchers announced a new class of antibiotics that could wipe out the drug-resistant superbug methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in mice.

Powered by deep learning, the study was a significant breakthrough. Few new antibiotics have come out since the 1960s, and this one in particular could be crucial in fighting tough-to-treat MRSA, which kills more than 10,000 people annually in the United States.

But as remarkable as the antibiotic discovery was, it may not be the most impactful part of this study.

“Of course, we view the antibiotic-discovery angle to be very important,” said Felix Wong, PhD, a colead author of the study and postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts. “But I think equally important, or maybe even more important, is really our method of opening up the black box.”

The black box is generally thought of as impenetrable in complex machine learning models, and that poses a challenge in the drug discovery realm.

“A major bottleneck in AI-ML-driven drug discovery is that nobody knows what the heck is going on,” said Dr. Wong. Models have such powerful architectures that their decision-making is mysterious.

Researchers input data, such as patient features, and the model says what drugs might be effective. But researchers have no idea how the model arrived at its predictions — until now.

What the Researchers Did

Dr. Wong and his colleagues first mined 39,000 compounds for antibiotic activity against MRSA. They fed information about the compounds’ chemical structures and antibiotic activity into their machine learning model. With this, they “trained” the model to predict whether a compound is antibacterial.

Next, they used additional deep learning to narrow the field, ruling out compounds toxic to humans. Then, deploying their various models at once, they screened 12 million commercially available compounds. Five classes emerged as likely MRSA fighters. Further testing of 280 compounds from the five classes produced the final results: Two compounds from the same class. Both reduced MRSA infection in mouse models.

How did the computer flag these compounds? The researchers sought to answer that question by figuring out which chemical structures the model had been looking for.

A chemical structure can be “pruned” — that is, scientists can remove certain atoms and bonds to reveal an underlying substructure. The MIT researchers used the Monte Carlo Tree Search, a commonly used algorithm in machine learning, to select which atoms and bonds to edit out. Then they fed the pruned substructures into their model to find out which was likely responsible for the antibacterial activity.

“The main idea is we can pinpoint which substructure of a chemical structure is causative instead of just correlated with high antibiotic activity,” Dr. Wong said.

This could fuel new “design-driven” or generative AI approaches where these substructures become “starting points to design entirely unseen, unprecedented antibiotics,” Dr. Wong said. “That’s one of the key efforts that we’ve been working on since the publication of this paper.”

More broadly, their method could lead to discoveries in drug classes beyond antibiotics, such as antivirals and anticancer drugs, according to Dr. Wong.

“This is the first major study that I’ve seen seeking to incorporate explainability into deep learning models in the context of antibiotics,” said César de la Fuente, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, whose lab has been engaged in AI for antibiotic discovery for the past 5 years.

“It’s kind of like going into the black box with a magnifying lens and figuring out what is actually happening in there,” Dr. de la Fuente said. “And that will open up possibilities for leveraging those different steps to make better drugs.”

How Explainable AI Could Revolutionize Medicine

In studies, explainable AI is showing its potential for informing clinical decisions as well — flagging high-risk patients and letting doctors know why that calculation was made. University of Washington researchers have used the technology to predict whether a patient will have hypoxemia during surgery, revealing which features contributed to the prediction, such as blood pressure or body mass index. Another study used explainable AI to help emergency medical services providers and emergency room clinicians optimize time — for example, by identifying trauma patients at high risk for acute traumatic coagulopathy more quickly.

A crucial benefit of explainable AI is its ability to audit machine learning models for mistakes, said Su-In Lee, PhD, a computer scientist who led the UW research.

For example, a surge of research during the pandemic suggested that AI models could predict COVID-19 infection based on chest x-rays. Dr. Lee’s research used explainable AI to show that many of the studies were not as accurate as they claimed. Her lab revealed that many models› decisions were based not on pathologies but rather on other aspects such as laterality markers in the corners of x-rays or medical devices worn by patients (like pacemakers). She applied the same model auditing technique to AI-powered dermatology devices, digging into the flawed reasoning in their melanoma predictions.

Explainable AI is beginning to affect drug development too. A 2023 study led by Dr. Lee used it to explain how to select complementary drugs for acute myeloid leukemia patients based on the differentiation levels of cancer cells. And in two other studies aimed at identifying Alzheimer’s therapeutic targets, “explainable AI played a key role in terms of identifying the driver pathway,” she said.

Currently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval doesn’t require an understanding of a drug’s mechanism of action. But the issue is being raised more often, including at December’s Health Regulatory Policy Conference at MIT’s Jameel Clinic. And just over a year ago, Dr. Lee predicted that the FDA approval process would come to incorporate explainable AI analysis.

“I didn’t hesitate,” Dr. Lee said, regarding her prediction. “We didn’t see this in 2023, so I won’t assert that I was right, but I can confidently say that we are progressing in that direction.”

What’s Next?

The MIT study is part of the Antibiotics-AI project, a 7-year effort to leverage AI to find new antibiotics. Phare Bio, a nonprofit started by MIT professor James Collins, PhD, and others, will do clinical testing on the antibiotic candidates.

Even with the AI’s assistance, there’s still a long way to go before clinical approval.

But knowing which elements contribute to a candidate’s effectiveness against MRSA could help the researchers formulate scientific hypotheses and design better validation, Dr. Lee noted. In other words, because they used explainable AI, they could be better positioned for clinical trial success.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Belantamab Mafodotin Tops Daratumumab in Multiple Myeloma

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Belantamab mafodotin, a first-in-class anti-BCMA monoclonal antibody conjugate, was approved in the US in 2020 for adult patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who had received at least 4 prior therapies. However, in February 2023, the FDA withdrew this approval, following disappointing findings from a large confirmatory trial, called DREAMM-3. Although the agent is still being investigated to treat relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, the current FDA label says the agent is only available in the US through a restricted program.

- Patients with multiple myeloma who relapse often become refractory to frontline triplet or quadruplet regimens and need effective second-line options.