User login

Unusual Presentation of Erythema Elevatum Diutinum With Underlying Hepatitis B Infection

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) manifests on a clinicopathologic spectrum of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. The lesions typically present as persistent, symmetric, firm, red to purple papules or nodules on the extensor arms and dorsal hands.1,2 Underlying infectious, malignant, or autoimmune processes are commonly associated with the disease, notably Streptococcus infection and IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2,3 Hepatitis virus also is often implicated in association with EED. Cases of EED have been seen with concomitant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.4-6 We report a case of EED presenting in various stages of evolution associated with underlying hepatitis B infection alone.

Case Report

A 57-year-old man originally presented to an outpatient dermatology practice with a nodular, painful, episodic rash on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. A biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with prominent eosinophils. At the time, the skin findings were believed to be a manifestation of drug hypersensitivity, likely to opioid use. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Seven years later, the patient was admitted to the hospital with new-onset burning and stinging red nodules on the dorsum of the hands and persistence of the original episodic rash over the lower legs and bilateral flanks. In the interim, he was briefly treated with an oral prednisone taper and topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone cream 0.1% and clobetasol cream 0.05% without improvement.

On examination deep red to violaceous discrete nodules and plaques with overlying hyperkeratosis involving all distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands and extensor elbows were seen (Figure 1A). On the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1B), anterior legs, and periumbilical area were deeply erythematous papules and plaques with background hyperpigmentation. Across his lower back and bilateral flanks were erythematous papules with central hemorrhagic crusting (Figure 1C).

Pertinent laboratory findings included a positive hepatitis B surface antigen with hepatitis B DNA value 4,313,876 IU/mL and a hepatitis B virus quantitative polymerase chain reaction value of 6.64 U. The etiology was suspected to be intravenous drug abuse; however, the patient denied recreational drug use.

An additional infectious workup was negative for hepatitis C, streptococcus, syphilis, tuberculosis, and HIV. A complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, complement, cryoglobulins, and serum protein electrophoresis were within reference range. Autoimmune serologies were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, anti-Smith, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. Peripheral blood immunophenotyping, lactate dehydrogenase, quantitative immunoglobulins, and age-appropriate cancer screens did not demonstrate evidence for malignancy underlying the disease. Bilateral hand radiographs showed mild periostitis of the proximal phalanges without obvious erosions.

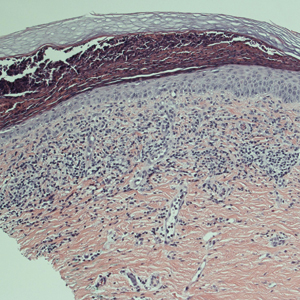

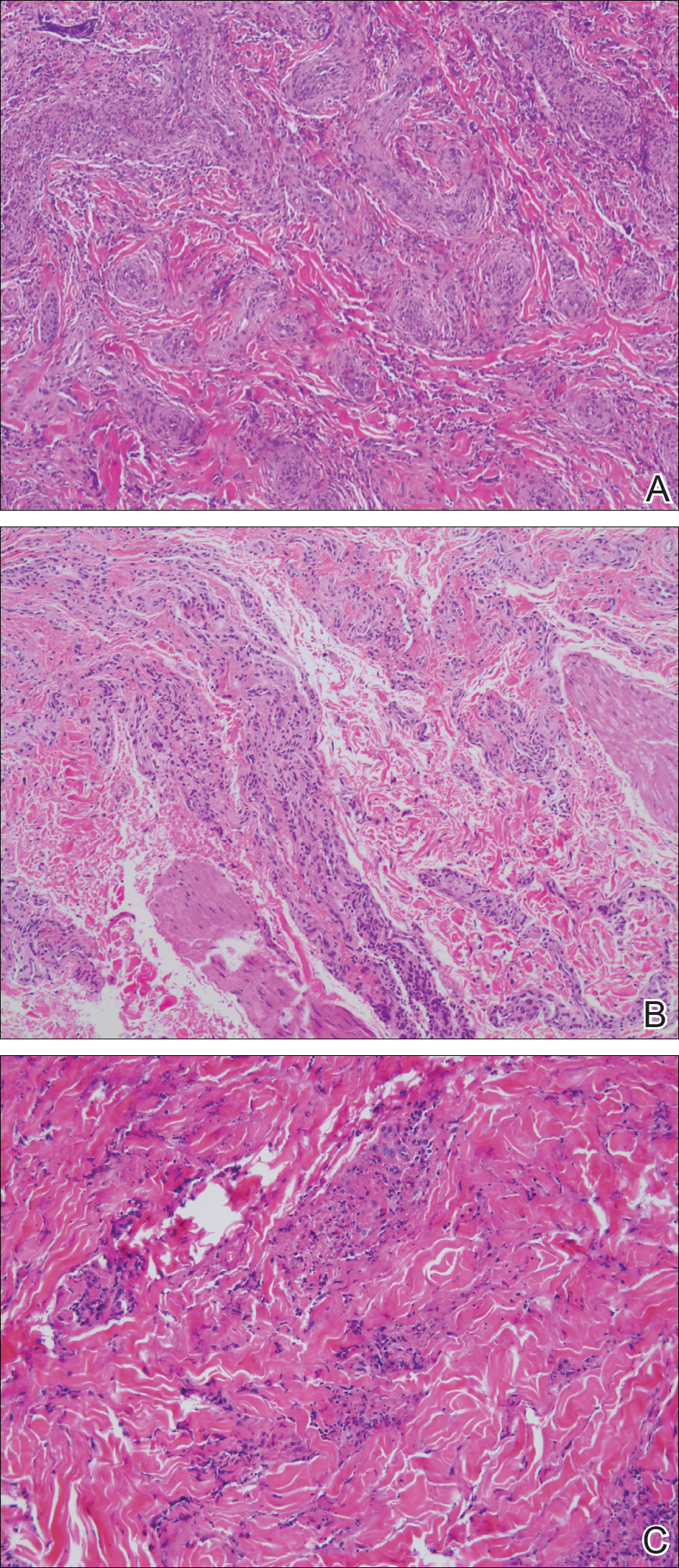

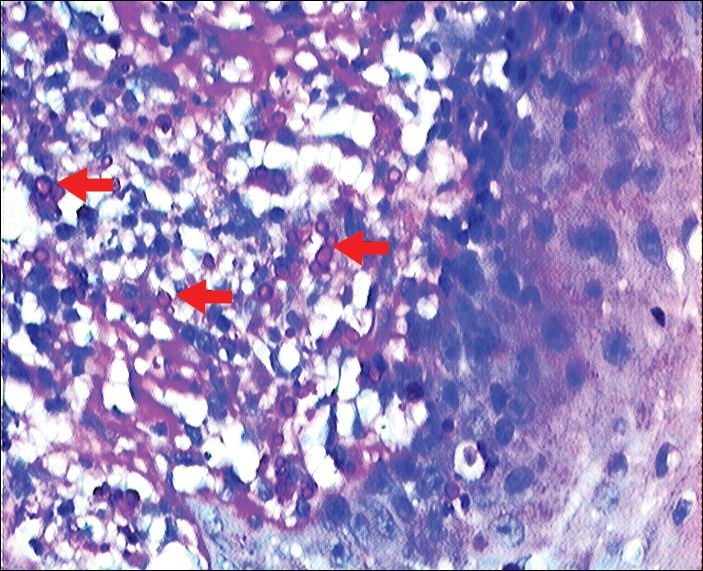

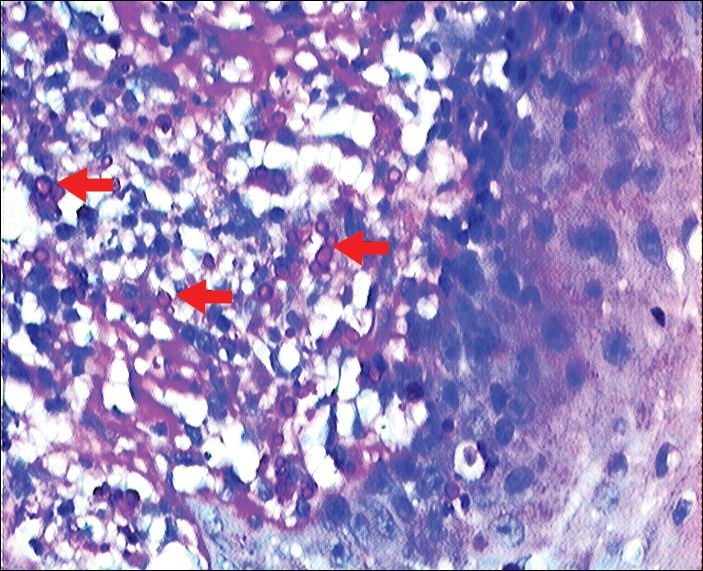

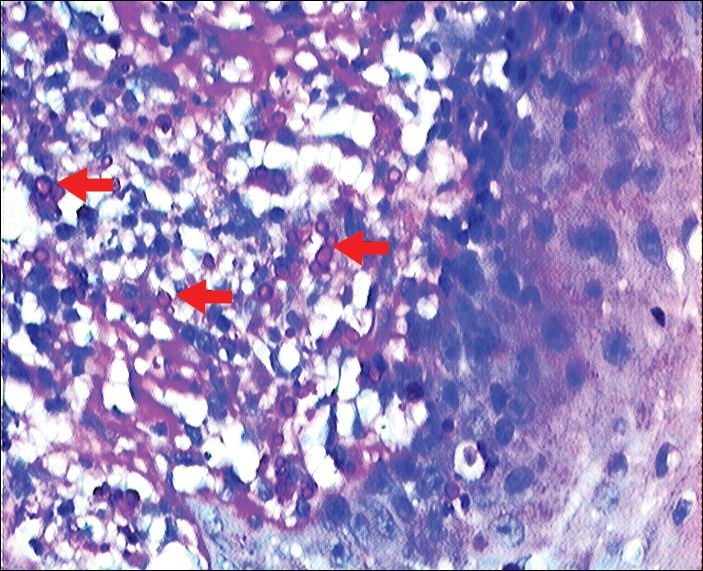

Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the left fifth digit, left posterior arm, and left flank. Tissue of the left fifth digit showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with a concentric pattern resembling onion skin in a background of increased fibrosis. The blood vessels showed focal fibrinoid necrosis (Figure 2A). The biopsy of the left posterior arm showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with an associated mild acute and chronic perivascular inflammation (Figure 2B). The left flank biopsy showed LCV with focal epidermal necrosis (Figure 2C).

The constellation of clinical findings together with the histopathologic changes represented EED in various stages of evolution. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and referred to the infectious disease service for treatment of chronic hepatitis B; however, he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Overview of EED

Erythema elevatum diutinum represents a rare form of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Originally described by Hutchinson7 and Bury8 as symmetric purpuric nodules of the skin, it was later named by Crocker and Williams9 in 1894. The disease classically presents as firm, fixed, red-brown to violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules affecting the extensor upper or lower extremities.1 Lesions are most commonly found symmetrically overlying joints of the hands, feet, elbows, and knees, as well as the Achilles tendon and buttocks.3 Less common locations include the palms and soles, face,10,11 trunk,12 and periauricular region.1 Although they are typically asymptomatic, sensations such as burning, stinging, and pruritus have been noted.1 Our patient was unique because in addition to typical lesions of EED, he presented with crusted papules on the flanks and violaceous papules of the lower legs and periumbilicus.

Etiology

Originally associated with Streptococcus as isolated from EED lesions,3,13 additional infectious etiologies include viral hepatitis,4-6 human herpesvirus 6,14 and rarely HIV.1,15 Hepatitis B and C are well known to be associated with EED, with only rare reports in patients with concomitant HIV infection. Erythema elevatum diutinum also has been described in relationship to myeloproliferative disorders and hematologic malignancies such as IgA myeloma,16 non-Hodgkin lymphoma,17 chronic lymphocytic leukemia,18 and hypergammaglobulinemia.19 In a study of 13 patients with EED, 4 had associated underlying IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2 Autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis,20 ulcerative colitis,21 relapsing polychondritis,22 and systemic lupus erythematosus23 also have been implicated.

Pathogenesis

Although the precise pathogenesis of EED remains unknown, it has been suggested that a complement cascade initiated by immune-complex deposition in postcapillary venules induces an LCV.24,25 Chronic antigenic exposure or high antibody levels26 in the face of infections, autoimmune disease, or malignancy may incite this immune-complex reaction. Skin lesions seen in association with hepatitis reflect circulating immune-complex deposition in vessel walls causing destruction. It has been postulated that the duration of immune complexemia may be sufficient to account for the differences in the type of vascular injury seen in acute versus chronic infection.27

Histopathology

Erythema elevatum diutinum may present on a histopathologic spectrum of LCV, as manifested in our patient. Early lesions show predominantly polymorphonuclear cells with nuclear dust pattern in a wedge-shaped infiltrate with fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid dermis.2,3 Later lesions show vasculitis in addition to dermal aggregates of lymphocytes, neutrophils, fibrosis, and areas of granulation tissue. The fibrosis may be dense and comprised of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.28 Newly formed vessels within the granulation tissue have been postulated to be more susceptible to immune-complex deposition, thus potentiating the process.1,29

Management

Spontaneous resolution of EED may occur, albeit after a prolonged and recurrent course of up to 5 to 10 years.30 Treatment of the underlying cause, when identified, remains paramount. First-line therapy includes dapsone, shown to be effective in reducing lesion size to complete resolution in 80% of the 47 cases reviewed by Momen et al.31 Dapsone monotherapy tends to be less effective in treating nodular lesions associated with HIV-positivity, likely due to the extensive fibrosis.4,31 Combination therapy with dapsone and a sulfonamide,32 niacinamide and tetracycline,33 colchicine,34 or surgical excision35 may be necessary in more resistant cases.

Conclusion

Our case exemplifies the clinical histologic spectrum that EED can present. The constellation of clinical findings was histologically confirmed to be manifestations of the disease in various stages of evolution. When typical lesions of EED present along with cutaneous findings in less common locations, performing multiple biopsies can be helpful. The clinician should retain a high index of suspicion for an underlying etiology and perform a complete workup for infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Wilkinson SM, English JS, Smith NP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinicopathological study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:87-93.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2001;68:41-42, 55.

- Kim H. Erythema elevatum diutinum in an HIV-positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:411-412.

- Revenga F, Vera A, Muñoz A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and AIDS: are they related? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:250-251.

- Hutchinson J. On two remarkable cases of symmetrieal purple congestion of the skin in patches, with induration. Br J Dermatol. 1888;1:10-15.

- Bury JS. A case of erythema with remarkable nodular thickening and induration of the skin associated with intermittent albuminuria. Illustrated Medical News. 1889;3:145-149.

- Crocker HR, Williams C. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1894;6:33-38.

- Barzegar M, Davatchi CC, Akhyani M, et al. An atypical presentation of erythema elevatum diutinum involving palms and soles. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:73-75.

- Futei Y, Konohana I. A case of erythema elevatum diutinum associated with B-cell lymphoma: a rare distribution involving palms, soles and nails. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:116-119.

- Ben-Zvi GT, Bardsley V, Burrows NP. An atypical distribution of erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:269-270.

- Weidman FD, Besancon JH. Erythema elevatum diutinum. role of streptococci, and relationship to other rheumatic dermatoses. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1929;20:593-620.

- Drago F, Semino M, Rampini P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human herpesvirus 6 infection. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:91-92.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:335-338.

- Archimandritis AJ, Fertakis A, Alegakis G, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and IgA myeloma: an interesting association. Br Med J. 1977;2:613-614.

- Hatzitolios A, Tzellos TG, Savopoulos C, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum with rare distribution as a first clinical sign of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a novel association? J Dermatol. 2008;35:297-300.

- Delaporte E, Alfandari S, Fenaux P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:188-189.

- Miyagawa S, Kitamura W, Morita K, et al. Association of hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D syndrome with erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:572-574.

- Collier PM, Neill SM, Branfoot AC, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—a solitary lesion in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:394-395.

- Buahene K, Hudson M, Mowat A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—an unusual association with ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:204-206.

- Bernard P, Bedane C, Delrous JL, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with relapsing polychondritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:312-315.

- Hancox JG, Wallace CA, Sangueza OP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum associated with lupus panniculitis in a patient with discoid lesions of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:652-653.

- Haber H. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1955;67:121-145.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:443-455.

- Walker KD, Badame AJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:948-952.

- Popp JW, Harrist T, Dienstag JL, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with acute and chronic hepatitis. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:623-629.

- Lee AY, Nakagawa H, Nogita T, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: an ultrastructural case study. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:211-217.

- LeBoit PE, Yen TS, Wintroub B. The evolution of lesions in erythema elevatum diutinum. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:392-402.

- Soubeiran E, Wacker J, Hausser I, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum with unusual clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:303-305.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1594-1602.

- Vollum DI. Erythema elevatum diutinum—vesicular lesions and sulfone response. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:178-183.

- Kohler IK, Lorincz AL. Erythema elevatum diutinum treated with niacinamide and tetracycline. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:693-695.

- Henriksson R, Hofor PA, Hörngvist R. Erythema elevatum diutinum—a case successfully treated with colchicine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:451-453.

- Zacaron LH, Gonçalves JC, Curty VM, et al. Clinical and surgical therapeutic approach in erythema elevatum diutinum—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6, suppl 1):15-18.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) manifests on a clinicopathologic spectrum of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. The lesions typically present as persistent, symmetric, firm, red to purple papules or nodules on the extensor arms and dorsal hands.1,2 Underlying infectious, malignant, or autoimmune processes are commonly associated with the disease, notably Streptococcus infection and IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2,3 Hepatitis virus also is often implicated in association with EED. Cases of EED have been seen with concomitant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.4-6 We report a case of EED presenting in various stages of evolution associated with underlying hepatitis B infection alone.

Case Report

A 57-year-old man originally presented to an outpatient dermatology practice with a nodular, painful, episodic rash on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. A biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with prominent eosinophils. At the time, the skin findings were believed to be a manifestation of drug hypersensitivity, likely to opioid use. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Seven years later, the patient was admitted to the hospital with new-onset burning and stinging red nodules on the dorsum of the hands and persistence of the original episodic rash over the lower legs and bilateral flanks. In the interim, he was briefly treated with an oral prednisone taper and topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone cream 0.1% and clobetasol cream 0.05% without improvement.

On examination deep red to violaceous discrete nodules and plaques with overlying hyperkeratosis involving all distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands and extensor elbows were seen (Figure 1A). On the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1B), anterior legs, and periumbilical area were deeply erythematous papules and plaques with background hyperpigmentation. Across his lower back and bilateral flanks were erythematous papules with central hemorrhagic crusting (Figure 1C).

Pertinent laboratory findings included a positive hepatitis B surface antigen with hepatitis B DNA value 4,313,876 IU/mL and a hepatitis B virus quantitative polymerase chain reaction value of 6.64 U. The etiology was suspected to be intravenous drug abuse; however, the patient denied recreational drug use.

An additional infectious workup was negative for hepatitis C, streptococcus, syphilis, tuberculosis, and HIV. A complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, complement, cryoglobulins, and serum protein electrophoresis were within reference range. Autoimmune serologies were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, anti-Smith, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. Peripheral blood immunophenotyping, lactate dehydrogenase, quantitative immunoglobulins, and age-appropriate cancer screens did not demonstrate evidence for malignancy underlying the disease. Bilateral hand radiographs showed mild periostitis of the proximal phalanges without obvious erosions.

Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the left fifth digit, left posterior arm, and left flank. Tissue of the left fifth digit showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with a concentric pattern resembling onion skin in a background of increased fibrosis. The blood vessels showed focal fibrinoid necrosis (Figure 2A). The biopsy of the left posterior arm showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with an associated mild acute and chronic perivascular inflammation (Figure 2B). The left flank biopsy showed LCV with focal epidermal necrosis (Figure 2C).

The constellation of clinical findings together with the histopathologic changes represented EED in various stages of evolution. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and referred to the infectious disease service for treatment of chronic hepatitis B; however, he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Overview of EED

Erythema elevatum diutinum represents a rare form of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Originally described by Hutchinson7 and Bury8 as symmetric purpuric nodules of the skin, it was later named by Crocker and Williams9 in 1894. The disease classically presents as firm, fixed, red-brown to violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules affecting the extensor upper or lower extremities.1 Lesions are most commonly found symmetrically overlying joints of the hands, feet, elbows, and knees, as well as the Achilles tendon and buttocks.3 Less common locations include the palms and soles, face,10,11 trunk,12 and periauricular region.1 Although they are typically asymptomatic, sensations such as burning, stinging, and pruritus have been noted.1 Our patient was unique because in addition to typical lesions of EED, he presented with crusted papules on the flanks and violaceous papules of the lower legs and periumbilicus.

Etiology

Originally associated with Streptococcus as isolated from EED lesions,3,13 additional infectious etiologies include viral hepatitis,4-6 human herpesvirus 6,14 and rarely HIV.1,15 Hepatitis B and C are well known to be associated with EED, with only rare reports in patients with concomitant HIV infection. Erythema elevatum diutinum also has been described in relationship to myeloproliferative disorders and hematologic malignancies such as IgA myeloma,16 non-Hodgkin lymphoma,17 chronic lymphocytic leukemia,18 and hypergammaglobulinemia.19 In a study of 13 patients with EED, 4 had associated underlying IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2 Autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis,20 ulcerative colitis,21 relapsing polychondritis,22 and systemic lupus erythematosus23 also have been implicated.

Pathogenesis

Although the precise pathogenesis of EED remains unknown, it has been suggested that a complement cascade initiated by immune-complex deposition in postcapillary venules induces an LCV.24,25 Chronic antigenic exposure or high antibody levels26 in the face of infections, autoimmune disease, or malignancy may incite this immune-complex reaction. Skin lesions seen in association with hepatitis reflect circulating immune-complex deposition in vessel walls causing destruction. It has been postulated that the duration of immune complexemia may be sufficient to account for the differences in the type of vascular injury seen in acute versus chronic infection.27

Histopathology

Erythema elevatum diutinum may present on a histopathologic spectrum of LCV, as manifested in our patient. Early lesions show predominantly polymorphonuclear cells with nuclear dust pattern in a wedge-shaped infiltrate with fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid dermis.2,3 Later lesions show vasculitis in addition to dermal aggregates of lymphocytes, neutrophils, fibrosis, and areas of granulation tissue. The fibrosis may be dense and comprised of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.28 Newly formed vessels within the granulation tissue have been postulated to be more susceptible to immune-complex deposition, thus potentiating the process.1,29

Management

Spontaneous resolution of EED may occur, albeit after a prolonged and recurrent course of up to 5 to 10 years.30 Treatment of the underlying cause, when identified, remains paramount. First-line therapy includes dapsone, shown to be effective in reducing lesion size to complete resolution in 80% of the 47 cases reviewed by Momen et al.31 Dapsone monotherapy tends to be less effective in treating nodular lesions associated with HIV-positivity, likely due to the extensive fibrosis.4,31 Combination therapy with dapsone and a sulfonamide,32 niacinamide and tetracycline,33 colchicine,34 or surgical excision35 may be necessary in more resistant cases.

Conclusion

Our case exemplifies the clinical histologic spectrum that EED can present. The constellation of clinical findings was histologically confirmed to be manifestations of the disease in various stages of evolution. When typical lesions of EED present along with cutaneous findings in less common locations, performing multiple biopsies can be helpful. The clinician should retain a high index of suspicion for an underlying etiology and perform a complete workup for infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) manifests on a clinicopathologic spectrum of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. The lesions typically present as persistent, symmetric, firm, red to purple papules or nodules on the extensor arms and dorsal hands.1,2 Underlying infectious, malignant, or autoimmune processes are commonly associated with the disease, notably Streptococcus infection and IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2,3 Hepatitis virus also is often implicated in association with EED. Cases of EED have been seen with concomitant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.4-6 We report a case of EED presenting in various stages of evolution associated with underlying hepatitis B infection alone.

Case Report

A 57-year-old man originally presented to an outpatient dermatology practice with a nodular, painful, episodic rash on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. A biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with prominent eosinophils. At the time, the skin findings were believed to be a manifestation of drug hypersensitivity, likely to opioid use. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Seven years later, the patient was admitted to the hospital with new-onset burning and stinging red nodules on the dorsum of the hands and persistence of the original episodic rash over the lower legs and bilateral flanks. In the interim, he was briefly treated with an oral prednisone taper and topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone cream 0.1% and clobetasol cream 0.05% without improvement.

On examination deep red to violaceous discrete nodules and plaques with overlying hyperkeratosis involving all distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands and extensor elbows were seen (Figure 1A). On the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1B), anterior legs, and periumbilical area were deeply erythematous papules and plaques with background hyperpigmentation. Across his lower back and bilateral flanks were erythematous papules with central hemorrhagic crusting (Figure 1C).

Pertinent laboratory findings included a positive hepatitis B surface antigen with hepatitis B DNA value 4,313,876 IU/mL and a hepatitis B virus quantitative polymerase chain reaction value of 6.64 U. The etiology was suspected to be intravenous drug abuse; however, the patient denied recreational drug use.

An additional infectious workup was negative for hepatitis C, streptococcus, syphilis, tuberculosis, and HIV. A complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, complement, cryoglobulins, and serum protein electrophoresis were within reference range. Autoimmune serologies were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, anti-Smith, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. Peripheral blood immunophenotyping, lactate dehydrogenase, quantitative immunoglobulins, and age-appropriate cancer screens did not demonstrate evidence for malignancy underlying the disease. Bilateral hand radiographs showed mild periostitis of the proximal phalanges without obvious erosions.

Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the left fifth digit, left posterior arm, and left flank. Tissue of the left fifth digit showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with a concentric pattern resembling onion skin in a background of increased fibrosis. The blood vessels showed focal fibrinoid necrosis (Figure 2A). The biopsy of the left posterior arm showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with an associated mild acute and chronic perivascular inflammation (Figure 2B). The left flank biopsy showed LCV with focal epidermal necrosis (Figure 2C).

The constellation of clinical findings together with the histopathologic changes represented EED in various stages of evolution. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and referred to the infectious disease service for treatment of chronic hepatitis B; however, he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Overview of EED

Erythema elevatum diutinum represents a rare form of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Originally described by Hutchinson7 and Bury8 as symmetric purpuric nodules of the skin, it was later named by Crocker and Williams9 in 1894. The disease classically presents as firm, fixed, red-brown to violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules affecting the extensor upper or lower extremities.1 Lesions are most commonly found symmetrically overlying joints of the hands, feet, elbows, and knees, as well as the Achilles tendon and buttocks.3 Less common locations include the palms and soles, face,10,11 trunk,12 and periauricular region.1 Although they are typically asymptomatic, sensations such as burning, stinging, and pruritus have been noted.1 Our patient was unique because in addition to typical lesions of EED, he presented with crusted papules on the flanks and violaceous papules of the lower legs and periumbilicus.

Etiology

Originally associated with Streptococcus as isolated from EED lesions,3,13 additional infectious etiologies include viral hepatitis,4-6 human herpesvirus 6,14 and rarely HIV.1,15 Hepatitis B and C are well known to be associated with EED, with only rare reports in patients with concomitant HIV infection. Erythema elevatum diutinum also has been described in relationship to myeloproliferative disorders and hematologic malignancies such as IgA myeloma,16 non-Hodgkin lymphoma,17 chronic lymphocytic leukemia,18 and hypergammaglobulinemia.19 In a study of 13 patients with EED, 4 had associated underlying IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2 Autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis,20 ulcerative colitis,21 relapsing polychondritis,22 and systemic lupus erythematosus23 also have been implicated.

Pathogenesis

Although the precise pathogenesis of EED remains unknown, it has been suggested that a complement cascade initiated by immune-complex deposition in postcapillary venules induces an LCV.24,25 Chronic antigenic exposure or high antibody levels26 in the face of infections, autoimmune disease, or malignancy may incite this immune-complex reaction. Skin lesions seen in association with hepatitis reflect circulating immune-complex deposition in vessel walls causing destruction. It has been postulated that the duration of immune complexemia may be sufficient to account for the differences in the type of vascular injury seen in acute versus chronic infection.27

Histopathology

Erythema elevatum diutinum may present on a histopathologic spectrum of LCV, as manifested in our patient. Early lesions show predominantly polymorphonuclear cells with nuclear dust pattern in a wedge-shaped infiltrate with fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid dermis.2,3 Later lesions show vasculitis in addition to dermal aggregates of lymphocytes, neutrophils, fibrosis, and areas of granulation tissue. The fibrosis may be dense and comprised of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.28 Newly formed vessels within the granulation tissue have been postulated to be more susceptible to immune-complex deposition, thus potentiating the process.1,29

Management

Spontaneous resolution of EED may occur, albeit after a prolonged and recurrent course of up to 5 to 10 years.30 Treatment of the underlying cause, when identified, remains paramount. First-line therapy includes dapsone, shown to be effective in reducing lesion size to complete resolution in 80% of the 47 cases reviewed by Momen et al.31 Dapsone monotherapy tends to be less effective in treating nodular lesions associated with HIV-positivity, likely due to the extensive fibrosis.4,31 Combination therapy with dapsone and a sulfonamide,32 niacinamide and tetracycline,33 colchicine,34 or surgical excision35 may be necessary in more resistant cases.

Conclusion

Our case exemplifies the clinical histologic spectrum that EED can present. The constellation of clinical findings was histologically confirmed to be manifestations of the disease in various stages of evolution. When typical lesions of EED present along with cutaneous findings in less common locations, performing multiple biopsies can be helpful. The clinician should retain a high index of suspicion for an underlying etiology and perform a complete workup for infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Wilkinson SM, English JS, Smith NP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinicopathological study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:87-93.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2001;68:41-42, 55.

- Kim H. Erythema elevatum diutinum in an HIV-positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:411-412.

- Revenga F, Vera A, Muñoz A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and AIDS: are they related? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:250-251.

- Hutchinson J. On two remarkable cases of symmetrieal purple congestion of the skin in patches, with induration. Br J Dermatol. 1888;1:10-15.

- Bury JS. A case of erythema with remarkable nodular thickening and induration of the skin associated with intermittent albuminuria. Illustrated Medical News. 1889;3:145-149.

- Crocker HR, Williams C. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1894;6:33-38.

- Barzegar M, Davatchi CC, Akhyani M, et al. An atypical presentation of erythema elevatum diutinum involving palms and soles. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:73-75.

- Futei Y, Konohana I. A case of erythema elevatum diutinum associated with B-cell lymphoma: a rare distribution involving palms, soles and nails. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:116-119.

- Ben-Zvi GT, Bardsley V, Burrows NP. An atypical distribution of erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:269-270.

- Weidman FD, Besancon JH. Erythema elevatum diutinum. role of streptococci, and relationship to other rheumatic dermatoses. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1929;20:593-620.

- Drago F, Semino M, Rampini P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human herpesvirus 6 infection. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:91-92.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:335-338.

- Archimandritis AJ, Fertakis A, Alegakis G, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and IgA myeloma: an interesting association. Br Med J. 1977;2:613-614.

- Hatzitolios A, Tzellos TG, Savopoulos C, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum with rare distribution as a first clinical sign of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a novel association? J Dermatol. 2008;35:297-300.

- Delaporte E, Alfandari S, Fenaux P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:188-189.

- Miyagawa S, Kitamura W, Morita K, et al. Association of hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D syndrome with erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:572-574.

- Collier PM, Neill SM, Branfoot AC, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—a solitary lesion in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:394-395.

- Buahene K, Hudson M, Mowat A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—an unusual association with ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:204-206.

- Bernard P, Bedane C, Delrous JL, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with relapsing polychondritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:312-315.

- Hancox JG, Wallace CA, Sangueza OP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum associated with lupus panniculitis in a patient with discoid lesions of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:652-653.

- Haber H. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1955;67:121-145.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:443-455.

- Walker KD, Badame AJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:948-952.

- Popp JW, Harrist T, Dienstag JL, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with acute and chronic hepatitis. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:623-629.

- Lee AY, Nakagawa H, Nogita T, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: an ultrastructural case study. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:211-217.

- LeBoit PE, Yen TS, Wintroub B. The evolution of lesions in erythema elevatum diutinum. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:392-402.

- Soubeiran E, Wacker J, Hausser I, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum with unusual clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:303-305.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1594-1602.

- Vollum DI. Erythema elevatum diutinum—vesicular lesions and sulfone response. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:178-183.

- Kohler IK, Lorincz AL. Erythema elevatum diutinum treated with niacinamide and tetracycline. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:693-695.

- Henriksson R, Hofor PA, Hörngvist R. Erythema elevatum diutinum—a case successfully treated with colchicine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:451-453.

- Zacaron LH, Gonçalves JC, Curty VM, et al. Clinical and surgical therapeutic approach in erythema elevatum diutinum—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6, suppl 1):15-18.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Wilkinson SM, English JS, Smith NP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinicopathological study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:87-93.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2001;68:41-42, 55.

- Kim H. Erythema elevatum diutinum in an HIV-positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:411-412.

- Revenga F, Vera A, Muñoz A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and AIDS: are they related? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:250-251.

- Hutchinson J. On two remarkable cases of symmetrieal purple congestion of the skin in patches, with induration. Br J Dermatol. 1888;1:10-15.

- Bury JS. A case of erythema with remarkable nodular thickening and induration of the skin associated with intermittent albuminuria. Illustrated Medical News. 1889;3:145-149.

- Crocker HR, Williams C. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1894;6:33-38.

- Barzegar M, Davatchi CC, Akhyani M, et al. An atypical presentation of erythema elevatum diutinum involving palms and soles. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:73-75.

- Futei Y, Konohana I. A case of erythema elevatum diutinum associated with B-cell lymphoma: a rare distribution involving palms, soles and nails. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:116-119.

- Ben-Zvi GT, Bardsley V, Burrows NP. An atypical distribution of erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:269-270.

- Weidman FD, Besancon JH. Erythema elevatum diutinum. role of streptococci, and relationship to other rheumatic dermatoses. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1929;20:593-620.

- Drago F, Semino M, Rampini P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human herpesvirus 6 infection. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:91-92.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:335-338.

- Archimandritis AJ, Fertakis A, Alegakis G, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and IgA myeloma: an interesting association. Br Med J. 1977;2:613-614.

- Hatzitolios A, Tzellos TG, Savopoulos C, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum with rare distribution as a first clinical sign of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a novel association? J Dermatol. 2008;35:297-300.

- Delaporte E, Alfandari S, Fenaux P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:188-189.

- Miyagawa S, Kitamura W, Morita K, et al. Association of hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D syndrome with erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:572-574.

- Collier PM, Neill SM, Branfoot AC, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—a solitary lesion in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:394-395.

- Buahene K, Hudson M, Mowat A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—an unusual association with ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:204-206.

- Bernard P, Bedane C, Delrous JL, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with relapsing polychondritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:312-315.

- Hancox JG, Wallace CA, Sangueza OP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum associated with lupus panniculitis in a patient with discoid lesions of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:652-653.

- Haber H. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1955;67:121-145.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:443-455.

- Walker KD, Badame AJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:948-952.

- Popp JW, Harrist T, Dienstag JL, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with acute and chronic hepatitis. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:623-629.

- Lee AY, Nakagawa H, Nogita T, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: an ultrastructural case study. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:211-217.

- LeBoit PE, Yen TS, Wintroub B. The evolution of lesions in erythema elevatum diutinum. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:392-402.

- Soubeiran E, Wacker J, Hausser I, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum with unusual clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:303-305.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1594-1602.

- Vollum DI. Erythema elevatum diutinum—vesicular lesions and sulfone response. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:178-183.

- Kohler IK, Lorincz AL. Erythema elevatum diutinum treated with niacinamide and tetracycline. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:693-695.

- Henriksson R, Hofor PA, Hörngvist R. Erythema elevatum diutinum—a case successfully treated with colchicine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:451-453.

- Zacaron LH, Gonçalves JC, Curty VM, et al. Clinical and surgical therapeutic approach in erythema elevatum diutinum—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6, suppl 1):15-18.

Practice Points

- Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) often is associated with an underlying infectious process, including hepatitis B and hepatitis C, or a hematologic or autoimmune condition.

- If EED is suspected clinically, it may be beneficial to perform multiple biopsies from lesions at different stages of evolution to establish the diagnosis.

- First-line therapy includes treatment of any underlying condition and dapsone.

MRSA in Dermatology Inpatients With a Vesiculobullous Disorder

Methicillin, cloxacillin, flucloxacillin, and cefoxitin are stable, penicillinase-producing β-lactam antibiotics; Staphylococcus aureus strains resistant to these agents are designated as methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA). Based on genotypic and phenotypic differences there are 2 strains of MRSA: hospital acquired and community acquired.

The potential for nosocomial transmission and the limited number of antibiotics available to treat MRSA are problematic. Moreover, MRSA has emerged worldwide as a major nosocomial pathogen that contributes to morbidity and mortality. Methicillin-resistant S aureus infection in vesiculobullous disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is known to contribute to mortality.1

The reported prevalence of MRSA in India ranges from 12% to 38.44%.2-4 We frequently encounter MRSA in dermatology inpatients, especially those with a vesiculobullous disorder. The primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of MRSA in dermatology inpatients with a vesiculobullous disorder; the secondary objective was to determine if MRSA contributes to mortality.

Materials and Methods

A 1-year prospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted in a tertiary-care center. The study population included all dermatology inpatients with a vesiculobullous disorder. Patients with a vesiculobullous disorder secondary to a primary viral or bacterial disorder were excluded. Permission to conduct the study was granted by the institution’s Human Ethics Committee.

All patients underwent a detailed history and clinical examination. Routine hematology testing, urinalysis, measurement of the blood glucose level, and other investigations relevant to the vesiculobullous disorder were performed. Special investigations were Gram staining, culture, and susceptibility testing of material from a nasal swab and a swab of a representative skin lesion.

Detection of MRSA

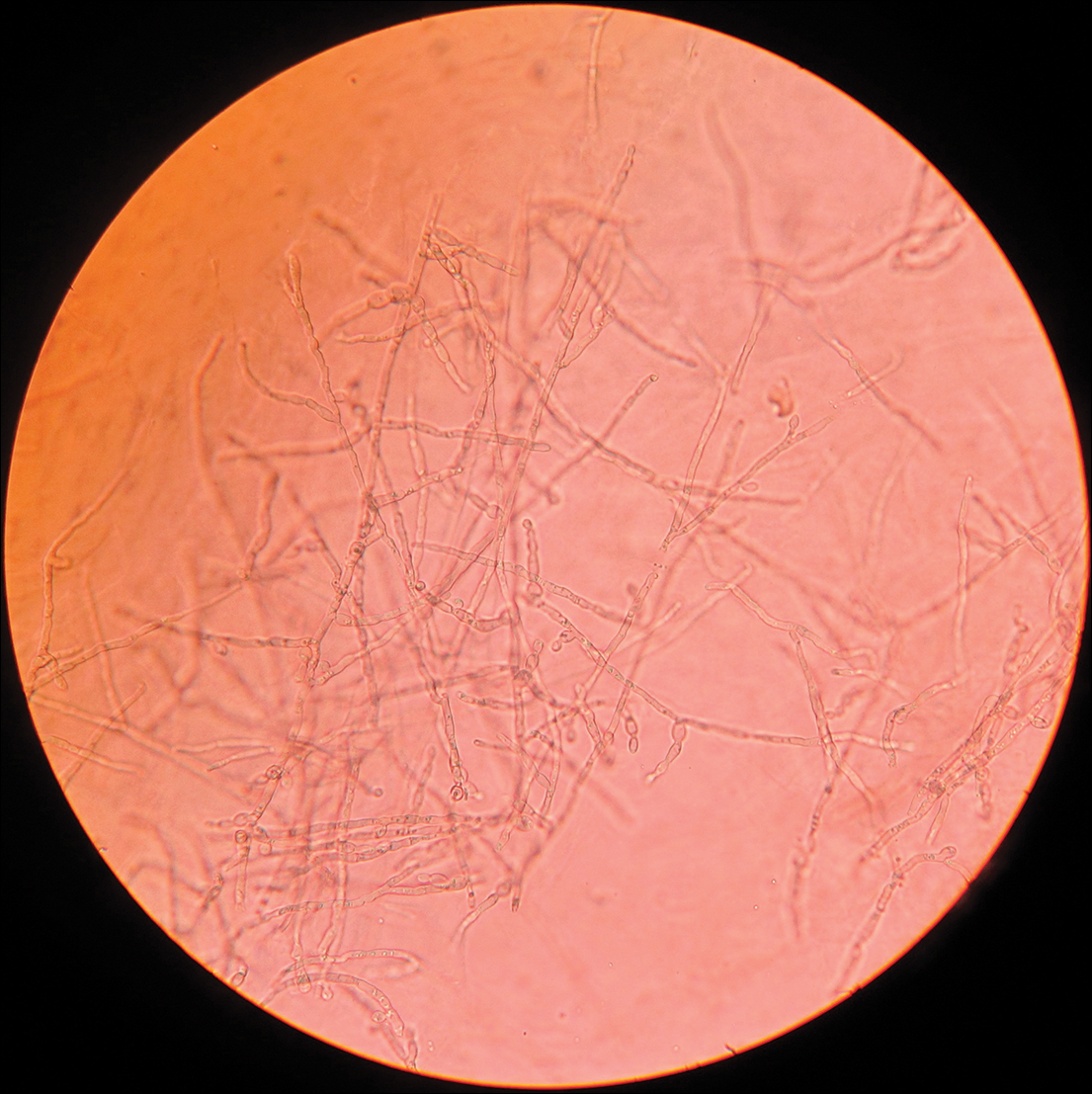

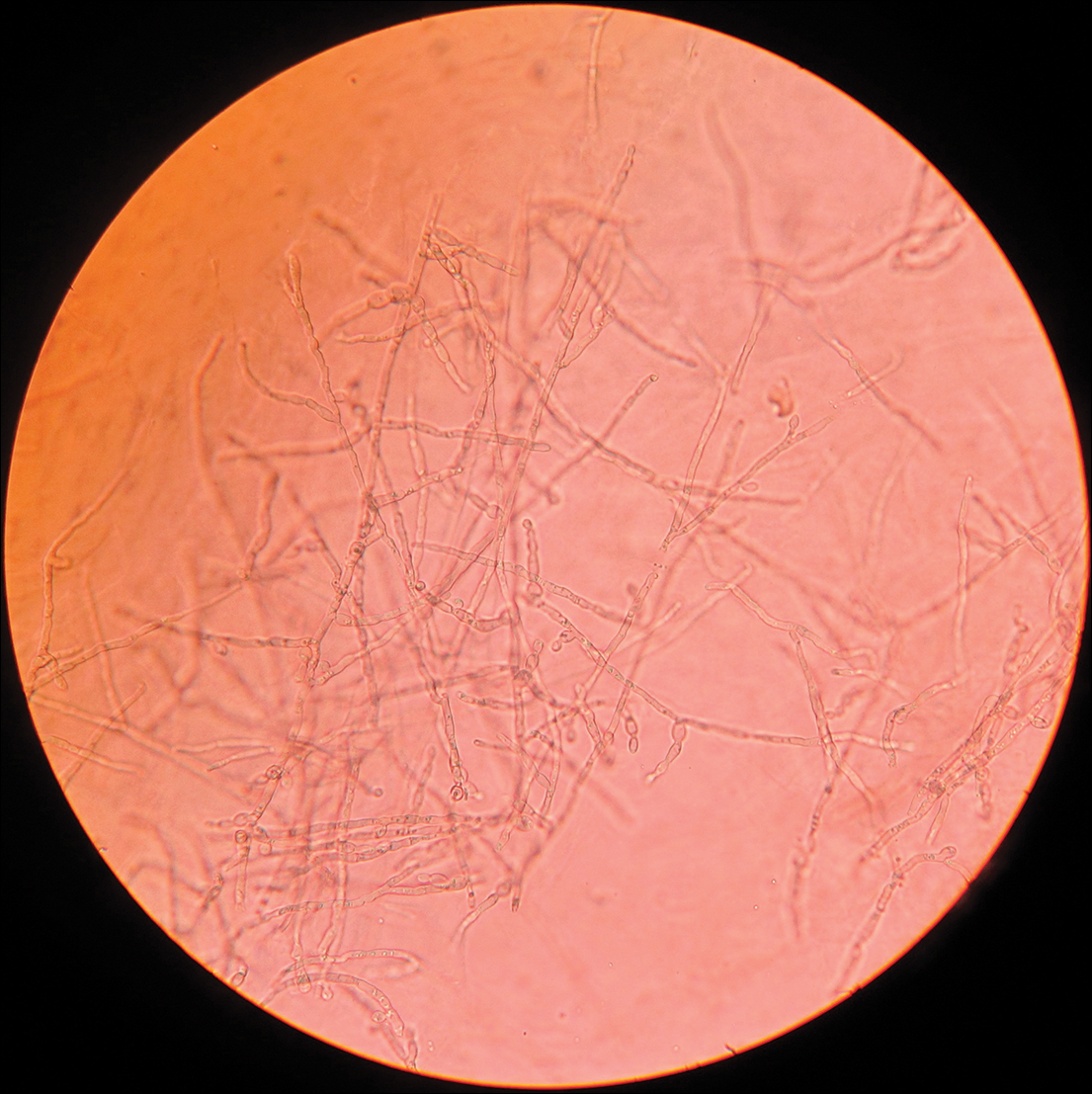

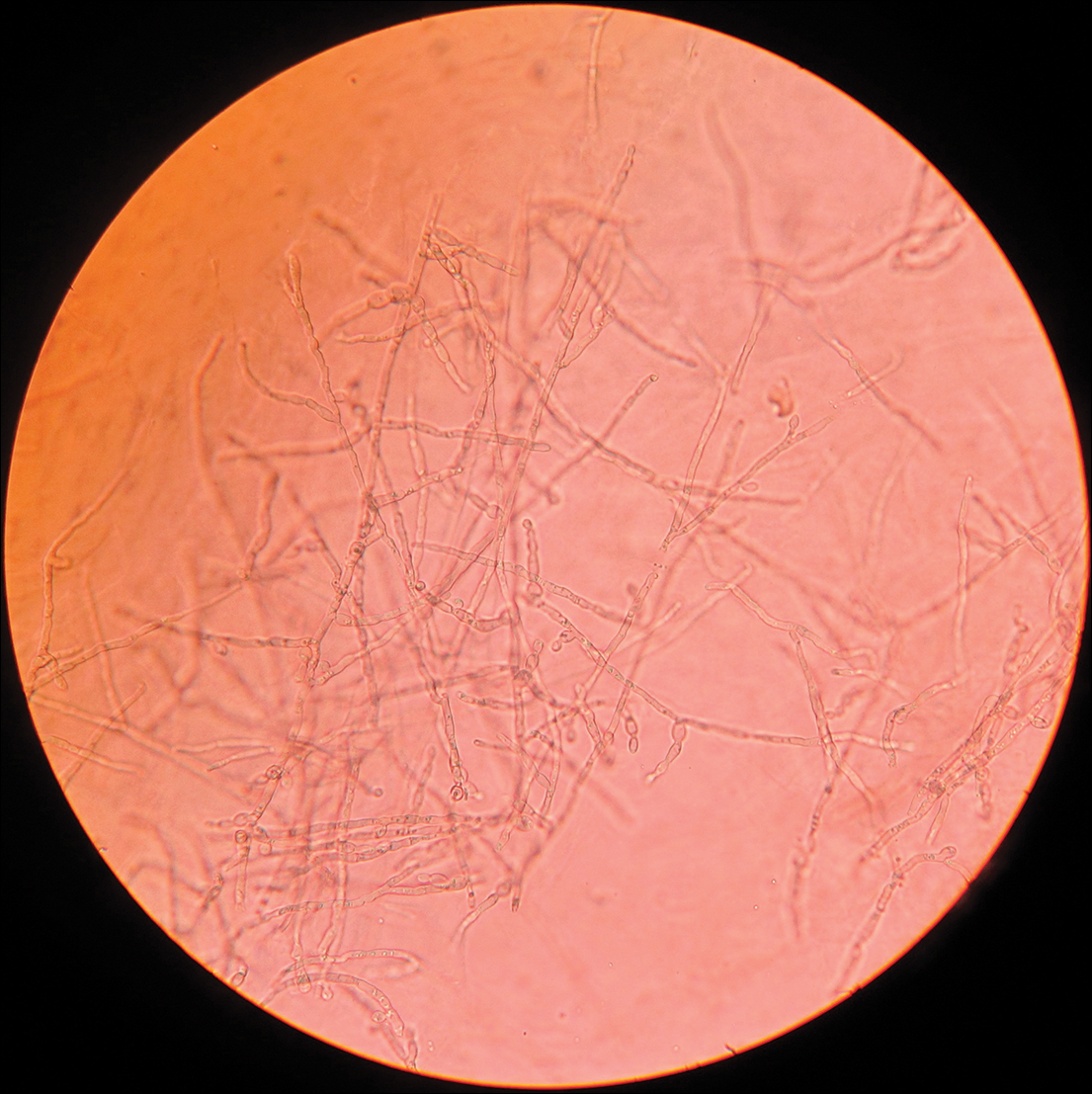

Skin lesions were thoroughly cleaned with sterile normal saline. Specimens of pus were drawn with a sterile swab for Gram staining, culture, and susceptibility testing and were analyzed in the institution’s microbiology department. A direct colony suspension (equivalent to McFarland Standard No. 0.5) was inoculated on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate, incorporating cefoxitin, linezolid, vancomycin, amikacin, and rifampicin supplemented with sodium chloride 2% and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Staphylococcus aureus colonies were identified by their smooth, convex, shiny, and opaque appearance with a golden yellow pigment, as well as by coagulase positivity, mannitol fermentation, and production of phosphatase.

Methicillin-resistant S aureus was defined as an isolate having a minimum inhibitory concentration of more than 2 μg/mL of cefoxitin; a methicillin-sensitive S aureus isolate was defined as having a minimum inhibitory concentration of less than or equal to 2 μg/mL of cefoxitin. Specimens showing moderate to heavy growth of MRSA were included in the study. For specimens showing mild growth, testing was repeated; if no growth was seen on repeat testing, results were interpreted as negative.

Data were collected and analyzed for frequency and percentage; P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

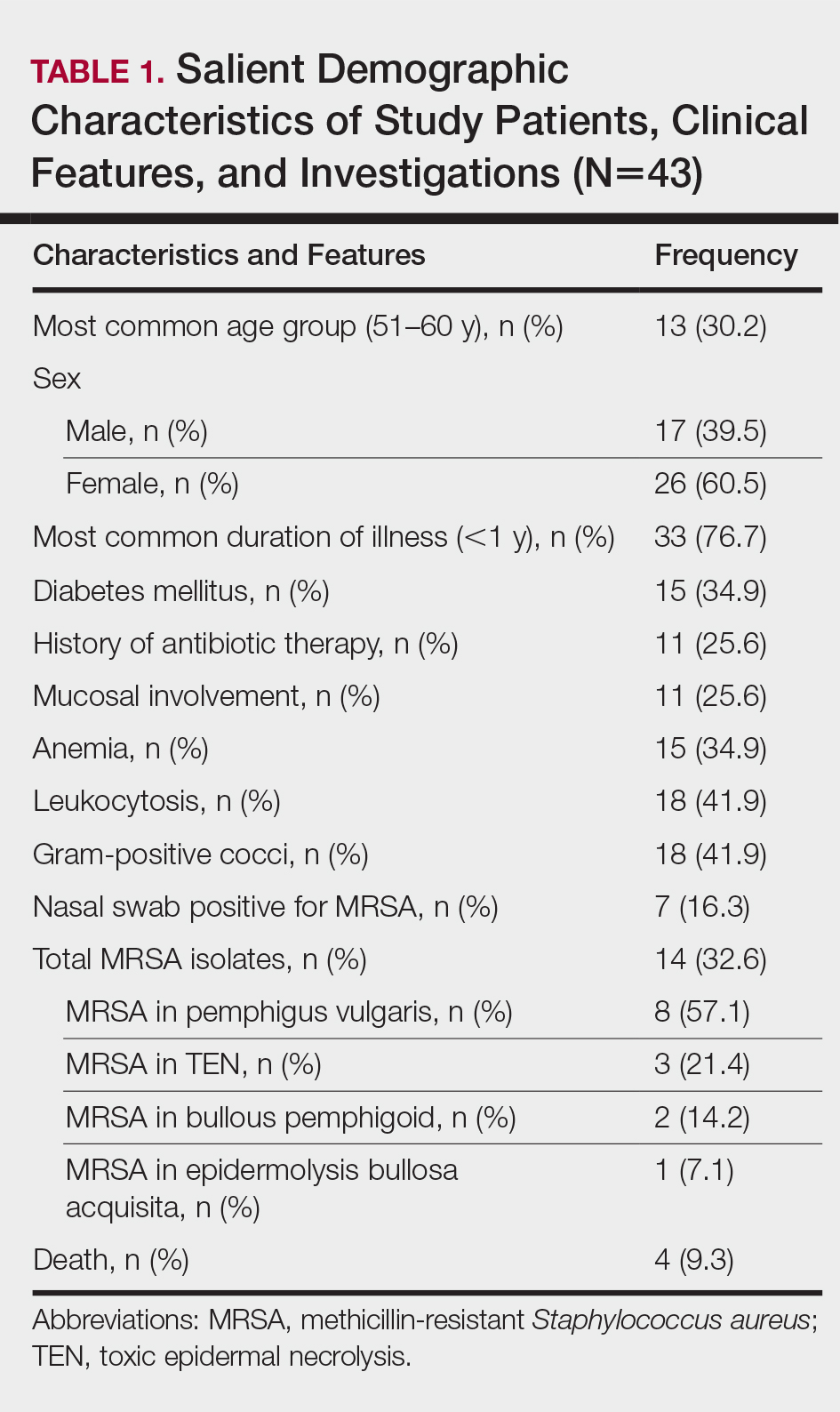

The number of patients analyzed in the study period was 43. Table 1 shows their salient demographic characteristics, clinical features, and findings of the investigation. The youngest patient was aged 13 years; the oldest was aged 80 years. The male to female ratio was 0.65 to 1. The most common primary lesion was a combined vesicle and bulla (34 patients [79.1%]); the most common secondary lesion was a combination of erosion with crusting (22 patients [51.2%]).

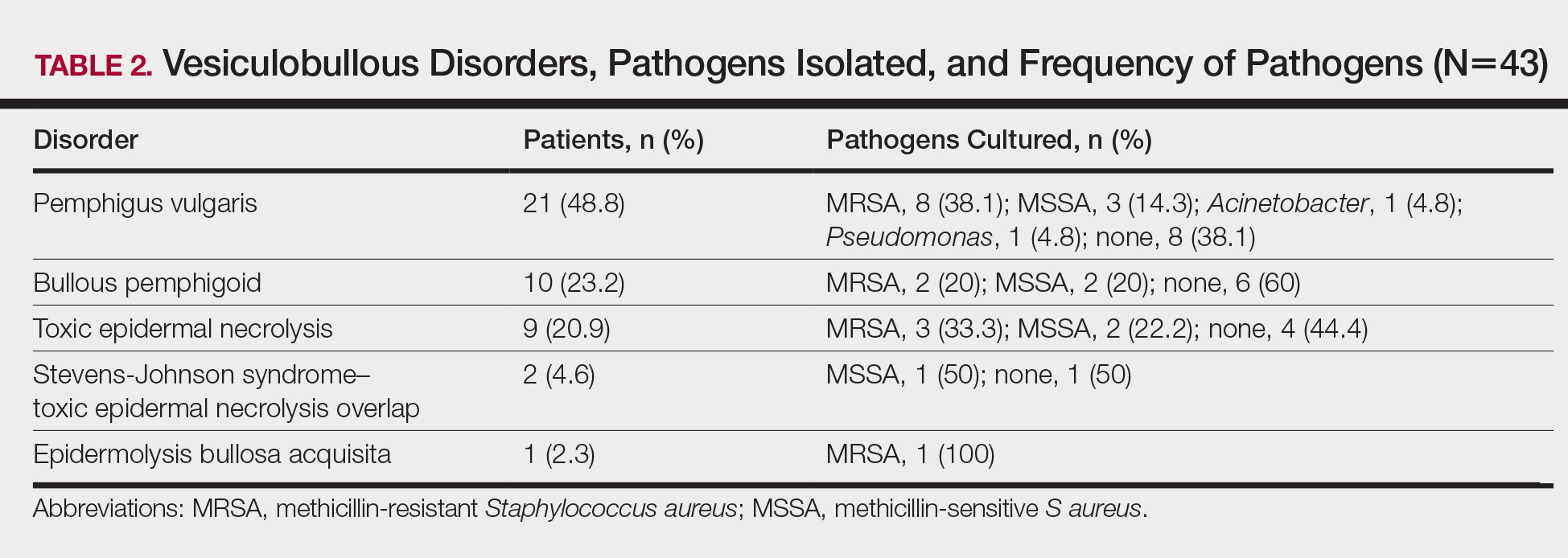

Table 2 lists the types of vesiculobullous disorders seen in this study. Pemphigus vulgaris was the most common (21 patients [48.8%])(Figure 1). Drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders (eg, TEN) were noted in 11 patients (25.6%)(Figure 2).

Table 2 also lists pathogens cultured in the study group. There were 24 bacterial isolates, of which S aureus accounted for 22 (91.7%). Methicillin-resistant S aureus was cultured in 14 patients (32.6%); culture was sterile in 19 patients (44.2%).

Among the 22 cultured staphylococcal species, MRSA accounted for 14 (63.6%) and constituted 58.3% (14/24) of all bacterial isolates. The nasal swab for MRSA was positive in 4 PV patients (9.3%), 2 TEN patients (4.6%), and 1 bullous pemphigoid patient (2.3%). Methicillin-resistant S aureus was most commonly cultured in PV patients (8/14 [57.1%]).

All MRSA strains (100%) were sensitive to vancomycin and linezolid; 34 (79.1%) were sensitive to amikacin. Additionally, 100% of MRSA strains were resistant to oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin.

Three patients with PV (7.0%) and 1 patient with TEN (2.3%) died during the course of the study; only 1 death (2.3%) occurred in a patient who had a positive MRSA culture.

Comment

In this 1-year study, we tested and followed 43 patients with autoimmune and drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders. Vesiculobullous disorders in dermatology inpatients are a cause of great concern. When lesions rupture, they leave behind a large area of erosion that forms a nidus of bacterial colonization; often, these bacteria cause severe infection, including septicemia, and result in death.5 Moreover, autoimmune bullous disorders usually require a prolonged hospital stay and powerful immunosuppressive drugs, which contributes to bacterial infection, especially MRSA.6

The age of patients in this study ranged from 13 to 80 years; most patients were in the 6th decade, a pattern seen in studies worldwide.5 In a study by Kanwar and De,7 however, most cases were aged 20 to 40 years.7 In our study, there was a female preponderance (male to female ratio of 0.65 to 1).

Studies have shown that the duration of illness in vesiculobullous disorder is directly associated with MRSA infection. However, in our study with MRSA detected in 14 patients, most patients had a duration of illness less than 1 year (statistically insignificant [P>.05]), a finding similar to Shafi et al.8

The symptomatic nature of these diseases, their unsightly appearance, and mucous-membrane involvement of vesiculobullous disorders prompts these patients to present to the hospital early. However, a prolonged hospital stay by patients with an autoimmune vesiculobullous disorders sets the stage for MRSA colonization.

In this study, diabetes mellitus (DM) was seen in 15 patients (34.9%); 5 of them had MRSA infection (statistically insignificant [P>.05]). Diabetes mellitus contributing to sepsis and MRSA infection, which in turn contributes to morbidity and mortality, has been well-documented.2,4,9

Methicillin-resistant S aureus in this study was isolated most often from blisters and erosions. Vesiculobullous disorders and drug reactions (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, TEN) are characterized by blisters that rupture to form erosions and crusting, which form fissures in the epidermal barrier function that are nidi for colonization by microbes, especially S aureus and MRSA in particular; later, these bacteria can enter dermal vessels and then the bloodstream, leading to septicemia.10

The prevalence of MRSA in this study was 32.6% (14/43), which is high compared to other studies.2-4 Pemphigus vulgaris was the most common disorder infected by MRSA in this study (57.1% [8/14] of MRSA isolates)(Table 1), a finding that reveals that the incidence of MRSA is high among staphylococcal isolates in vesiculobullous disorders. However, the high incidence of MRSA in this study could be a reflection of the number of patients with a severe and chronic vesiculobullous disorder, such as PV, and serious drug reactions such as TEN referred to our tertiary-care center, where we get a large number of patients affected by autoimmune and drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders. Similar findings have been reported by Stryjewski et al.11

A high prevalence of MRSA in a dermatology unit has grave consequences, contributing to morbidity and mortality in particular among patients with a vesiculobullous disorder. Immunosuppressive therapy and comorbidities such as DM contribute to MRSA colonization in vesiculobullous disorders.12 Overcrowding and poor sterilization techniques in public hospitals in India may contribute to the high prevalence of MRSA seen in hospital units.

Patients with a vesiculobullous disorder who are chronic nasal carriers of MRSA are at risk for cutaneous MRSA infection, which in turn can lead to MRSA septicemia and an elevated risk of death. In this study, however, a nasal swab was positive for MRSA in only 7 patients. One patient with MRSA colonization died, which was statistically insignificant (P=1).

In this study, all MRSA strains (100%) were resistant to first-line antibiotics, such as oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin; all strains were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid.

Conclusion

Our study shows that MRSA is becoming the prominent pathogen in nosocomial infections, especially in bedridden patients, which has grave implications. The use of a prophylactic S aureus conjugate vaccine in patients with a chronic vesiculobullous disorder might be justified in the future.15 We found a high prevalence (32.6%) of MRSA in vesiculobullous disorders, no relationship between DM and MRSA colonization, PV was the most common disorder complicated by MRSA, no relationship between nasal colonization and MRSA infection, no relationship between death during the study period and MRSA infection, 100% of MRSA strains were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid, and 79.1% of MRSA strains were susceptible to amikacin.

- Nair SP. A retrospective study of mortality of pemphigus patients in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:706-709.

- Sachdev D, Amladi S, Natarj G, et al. An outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in dermatology inpatients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:377-380.

- Vijayamohan N, Nair SP. A study of the prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology inpatients. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:441-445.

- Malhotra SK, Malhotra S, Dhaliwal GS, et al. Bacterial study of pyodermas in a tertiary care dermatological center. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:358-361.

- Valencia IC, Kirsner RS, Kerdel FA. Microbiological evaluation of skin wounds: alarming trends towards antibiotic resistance in an inpatient dermatology service during a 10-year period. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:845-849.

- Lehman JS, Murell DF, Camilleri MJ, et al. Infection and infection prevention in patients treated with immunosuppressive medications for autoimmune bullous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:591-598.

- Kanwar AJ, De D. Pemphigus in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:439-449.

- Shafi M, Khatri ML, Mashima M, et al. Pemphigus: a clinical study of 109 cases from Tripoli, Libya. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1994;60:140-143.

- Torres K, Sampathkumar P. Predictors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization at hospital admission. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:1043-1047.

- Miller LG, Quan C, Shay A, et al. A prospective investigation of outcomes after hospital discharge for endemic, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:483-492.

- Stryjewski M, Chambers HF. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(suppl 5):S368-S377.

- Mutasim DF. Management of autoimmune bullous diseases: pharmacology and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:859-877.

- Cohen PR. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections: a review of epidemiology, clinical features, management, and prevention. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1-11.

- Elston DM. Methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: management principles and selection of antibiotic therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:157-164.

- Shinefield H, Black S, Fattom A, et al. Use of a Staphylococcus aureus conjugate vaccine in patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2001;346:491-496.

Methicillin, cloxacillin, flucloxacillin, and cefoxitin are stable, penicillinase-producing β-lactam antibiotics; Staphylococcus aureus strains resistant to these agents are designated as methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA). Based on genotypic and phenotypic differences there are 2 strains of MRSA: hospital acquired and community acquired.

The potential for nosocomial transmission and the limited number of antibiotics available to treat MRSA are problematic. Moreover, MRSA has emerged worldwide as a major nosocomial pathogen that contributes to morbidity and mortality. Methicillin-resistant S aureus infection in vesiculobullous disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is known to contribute to mortality.1

The reported prevalence of MRSA in India ranges from 12% to 38.44%.2-4 We frequently encounter MRSA in dermatology inpatients, especially those with a vesiculobullous disorder. The primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of MRSA in dermatology inpatients with a vesiculobullous disorder; the secondary objective was to determine if MRSA contributes to mortality.

Materials and Methods

A 1-year prospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted in a tertiary-care center. The study population included all dermatology inpatients with a vesiculobullous disorder. Patients with a vesiculobullous disorder secondary to a primary viral or bacterial disorder were excluded. Permission to conduct the study was granted by the institution’s Human Ethics Committee.

All patients underwent a detailed history and clinical examination. Routine hematology testing, urinalysis, measurement of the blood glucose level, and other investigations relevant to the vesiculobullous disorder were performed. Special investigations were Gram staining, culture, and susceptibility testing of material from a nasal swab and a swab of a representative skin lesion.

Detection of MRSA

Skin lesions were thoroughly cleaned with sterile normal saline. Specimens of pus were drawn with a sterile swab for Gram staining, culture, and susceptibility testing and were analyzed in the institution’s microbiology department. A direct colony suspension (equivalent to McFarland Standard No. 0.5) was inoculated on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate, incorporating cefoxitin, linezolid, vancomycin, amikacin, and rifampicin supplemented with sodium chloride 2% and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Staphylococcus aureus colonies were identified by their smooth, convex, shiny, and opaque appearance with a golden yellow pigment, as well as by coagulase positivity, mannitol fermentation, and production of phosphatase.

Methicillin-resistant S aureus was defined as an isolate having a minimum inhibitory concentration of more than 2 μg/mL of cefoxitin; a methicillin-sensitive S aureus isolate was defined as having a minimum inhibitory concentration of less than or equal to 2 μg/mL of cefoxitin. Specimens showing moderate to heavy growth of MRSA were included in the study. For specimens showing mild growth, testing was repeated; if no growth was seen on repeat testing, results were interpreted as negative.

Data were collected and analyzed for frequency and percentage; P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

The number of patients analyzed in the study period was 43. Table 1 shows their salient demographic characteristics, clinical features, and findings of the investigation. The youngest patient was aged 13 years; the oldest was aged 80 years. The male to female ratio was 0.65 to 1. The most common primary lesion was a combined vesicle and bulla (34 patients [79.1%]); the most common secondary lesion was a combination of erosion with crusting (22 patients [51.2%]).

Table 2 lists the types of vesiculobullous disorders seen in this study. Pemphigus vulgaris was the most common (21 patients [48.8%])(Figure 1). Drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders (eg, TEN) were noted in 11 patients (25.6%)(Figure 2).

Table 2 also lists pathogens cultured in the study group. There were 24 bacterial isolates, of which S aureus accounted for 22 (91.7%). Methicillin-resistant S aureus was cultured in 14 patients (32.6%); culture was sterile in 19 patients (44.2%).

Among the 22 cultured staphylococcal species, MRSA accounted for 14 (63.6%) and constituted 58.3% (14/24) of all bacterial isolates. The nasal swab for MRSA was positive in 4 PV patients (9.3%), 2 TEN patients (4.6%), and 1 bullous pemphigoid patient (2.3%). Methicillin-resistant S aureus was most commonly cultured in PV patients (8/14 [57.1%]).

All MRSA strains (100%) were sensitive to vancomycin and linezolid; 34 (79.1%) were sensitive to amikacin. Additionally, 100% of MRSA strains were resistant to oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin.

Three patients with PV (7.0%) and 1 patient with TEN (2.3%) died during the course of the study; only 1 death (2.3%) occurred in a patient who had a positive MRSA culture.

Comment

In this 1-year study, we tested and followed 43 patients with autoimmune and drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders. Vesiculobullous disorders in dermatology inpatients are a cause of great concern. When lesions rupture, they leave behind a large area of erosion that forms a nidus of bacterial colonization; often, these bacteria cause severe infection, including septicemia, and result in death.5 Moreover, autoimmune bullous disorders usually require a prolonged hospital stay and powerful immunosuppressive drugs, which contributes to bacterial infection, especially MRSA.6

The age of patients in this study ranged from 13 to 80 years; most patients were in the 6th decade, a pattern seen in studies worldwide.5 In a study by Kanwar and De,7 however, most cases were aged 20 to 40 years.7 In our study, there was a female preponderance (male to female ratio of 0.65 to 1).

Studies have shown that the duration of illness in vesiculobullous disorder is directly associated with MRSA infection. However, in our study with MRSA detected in 14 patients, most patients had a duration of illness less than 1 year (statistically insignificant [P>.05]), a finding similar to Shafi et al.8

The symptomatic nature of these diseases, their unsightly appearance, and mucous-membrane involvement of vesiculobullous disorders prompts these patients to present to the hospital early. However, a prolonged hospital stay by patients with an autoimmune vesiculobullous disorders sets the stage for MRSA colonization.

In this study, diabetes mellitus (DM) was seen in 15 patients (34.9%); 5 of them had MRSA infection (statistically insignificant [P>.05]). Diabetes mellitus contributing to sepsis and MRSA infection, which in turn contributes to morbidity and mortality, has been well-documented.2,4,9

Methicillin-resistant S aureus in this study was isolated most often from blisters and erosions. Vesiculobullous disorders and drug reactions (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, TEN) are characterized by blisters that rupture to form erosions and crusting, which form fissures in the epidermal barrier function that are nidi for colonization by microbes, especially S aureus and MRSA in particular; later, these bacteria can enter dermal vessels and then the bloodstream, leading to septicemia.10

The prevalence of MRSA in this study was 32.6% (14/43), which is high compared to other studies.2-4 Pemphigus vulgaris was the most common disorder infected by MRSA in this study (57.1% [8/14] of MRSA isolates)(Table 1), a finding that reveals that the incidence of MRSA is high among staphylococcal isolates in vesiculobullous disorders. However, the high incidence of MRSA in this study could be a reflection of the number of patients with a severe and chronic vesiculobullous disorder, such as PV, and serious drug reactions such as TEN referred to our tertiary-care center, where we get a large number of patients affected by autoimmune and drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders. Similar findings have been reported by Stryjewski et al.11

A high prevalence of MRSA in a dermatology unit has grave consequences, contributing to morbidity and mortality in particular among patients with a vesiculobullous disorder. Immunosuppressive therapy and comorbidities such as DM contribute to MRSA colonization in vesiculobullous disorders.12 Overcrowding and poor sterilization techniques in public hospitals in India may contribute to the high prevalence of MRSA seen in hospital units.

Patients with a vesiculobullous disorder who are chronic nasal carriers of MRSA are at risk for cutaneous MRSA infection, which in turn can lead to MRSA septicemia and an elevated risk of death. In this study, however, a nasal swab was positive for MRSA in only 7 patients. One patient with MRSA colonization died, which was statistically insignificant (P=1).

In this study, all MRSA strains (100%) were resistant to first-line antibiotics, such as oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin; all strains were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid.

Conclusion

Our study shows that MRSA is becoming the prominent pathogen in nosocomial infections, especially in bedridden patients, which has grave implications. The use of a prophylactic S aureus conjugate vaccine in patients with a chronic vesiculobullous disorder might be justified in the future.15 We found a high prevalence (32.6%) of MRSA in vesiculobullous disorders, no relationship between DM and MRSA colonization, PV was the most common disorder complicated by MRSA, no relationship between nasal colonization and MRSA infection, no relationship between death during the study period and MRSA infection, 100% of MRSA strains were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid, and 79.1% of MRSA strains were susceptible to amikacin.

Methicillin, cloxacillin, flucloxacillin, and cefoxitin are stable, penicillinase-producing β-lactam antibiotics; Staphylococcus aureus strains resistant to these agents are designated as methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA). Based on genotypic and phenotypic differences there are 2 strains of MRSA: hospital acquired and community acquired.

The potential for nosocomial transmission and the limited number of antibiotics available to treat MRSA are problematic. Moreover, MRSA has emerged worldwide as a major nosocomial pathogen that contributes to morbidity and mortality. Methicillin-resistant S aureus infection in vesiculobullous disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is known to contribute to mortality.1

The reported prevalence of MRSA in India ranges from 12% to 38.44%.2-4 We frequently encounter MRSA in dermatology inpatients, especially those with a vesiculobullous disorder. The primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of MRSA in dermatology inpatients with a vesiculobullous disorder; the secondary objective was to determine if MRSA contributes to mortality.

Materials and Methods

A 1-year prospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted in a tertiary-care center. The study population included all dermatology inpatients with a vesiculobullous disorder. Patients with a vesiculobullous disorder secondary to a primary viral or bacterial disorder were excluded. Permission to conduct the study was granted by the institution’s Human Ethics Committee.

All patients underwent a detailed history and clinical examination. Routine hematology testing, urinalysis, measurement of the blood glucose level, and other investigations relevant to the vesiculobullous disorder were performed. Special investigations were Gram staining, culture, and susceptibility testing of material from a nasal swab and a swab of a representative skin lesion.

Detection of MRSA

Skin lesions were thoroughly cleaned with sterile normal saline. Specimens of pus were drawn with a sterile swab for Gram staining, culture, and susceptibility testing and were analyzed in the institution’s microbiology department. A direct colony suspension (equivalent to McFarland Standard No. 0.5) was inoculated on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate, incorporating cefoxitin, linezolid, vancomycin, amikacin, and rifampicin supplemented with sodium chloride 2% and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Staphylococcus aureus colonies were identified by their smooth, convex, shiny, and opaque appearance with a golden yellow pigment, as well as by coagulase positivity, mannitol fermentation, and production of phosphatase.

Methicillin-resistant S aureus was defined as an isolate having a minimum inhibitory concentration of more than 2 μg/mL of cefoxitin; a methicillin-sensitive S aureus isolate was defined as having a minimum inhibitory concentration of less than or equal to 2 μg/mL of cefoxitin. Specimens showing moderate to heavy growth of MRSA were included in the study. For specimens showing mild growth, testing was repeated; if no growth was seen on repeat testing, results were interpreted as negative.

Data were collected and analyzed for frequency and percentage; P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

The number of patients analyzed in the study period was 43. Table 1 shows their salient demographic characteristics, clinical features, and findings of the investigation. The youngest patient was aged 13 years; the oldest was aged 80 years. The male to female ratio was 0.65 to 1. The most common primary lesion was a combined vesicle and bulla (34 patients [79.1%]); the most common secondary lesion was a combination of erosion with crusting (22 patients [51.2%]).

Table 2 lists the types of vesiculobullous disorders seen in this study. Pemphigus vulgaris was the most common (21 patients [48.8%])(Figure 1). Drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders (eg, TEN) were noted in 11 patients (25.6%)(Figure 2).

Table 2 also lists pathogens cultured in the study group. There were 24 bacterial isolates, of which S aureus accounted for 22 (91.7%). Methicillin-resistant S aureus was cultured in 14 patients (32.6%); culture was sterile in 19 patients (44.2%).

Among the 22 cultured staphylococcal species, MRSA accounted for 14 (63.6%) and constituted 58.3% (14/24) of all bacterial isolates. The nasal swab for MRSA was positive in 4 PV patients (9.3%), 2 TEN patients (4.6%), and 1 bullous pemphigoid patient (2.3%). Methicillin-resistant S aureus was most commonly cultured in PV patients (8/14 [57.1%]).

All MRSA strains (100%) were sensitive to vancomycin and linezolid; 34 (79.1%) were sensitive to amikacin. Additionally, 100% of MRSA strains were resistant to oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin.

Three patients with PV (7.0%) and 1 patient with TEN (2.3%) died during the course of the study; only 1 death (2.3%) occurred in a patient who had a positive MRSA culture.

Comment

In this 1-year study, we tested and followed 43 patients with autoimmune and drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders. Vesiculobullous disorders in dermatology inpatients are a cause of great concern. When lesions rupture, they leave behind a large area of erosion that forms a nidus of bacterial colonization; often, these bacteria cause severe infection, including septicemia, and result in death.5 Moreover, autoimmune bullous disorders usually require a prolonged hospital stay and powerful immunosuppressive drugs, which contributes to bacterial infection, especially MRSA.6

The age of patients in this study ranged from 13 to 80 years; most patients were in the 6th decade, a pattern seen in studies worldwide.5 In a study by Kanwar and De,7 however, most cases were aged 20 to 40 years.7 In our study, there was a female preponderance (male to female ratio of 0.65 to 1).

Studies have shown that the duration of illness in vesiculobullous disorder is directly associated with MRSA infection. However, in our study with MRSA detected in 14 patients, most patients had a duration of illness less than 1 year (statistically insignificant [P>.05]), a finding similar to Shafi et al.8

The symptomatic nature of these diseases, their unsightly appearance, and mucous-membrane involvement of vesiculobullous disorders prompts these patients to present to the hospital early. However, a prolonged hospital stay by patients with an autoimmune vesiculobullous disorders sets the stage for MRSA colonization.

In this study, diabetes mellitus (DM) was seen in 15 patients (34.9%); 5 of them had MRSA infection (statistically insignificant [P>.05]). Diabetes mellitus contributing to sepsis and MRSA infection, which in turn contributes to morbidity and mortality, has been well-documented.2,4,9

Methicillin-resistant S aureus in this study was isolated most often from blisters and erosions. Vesiculobullous disorders and drug reactions (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, TEN) are characterized by blisters that rupture to form erosions and crusting, which form fissures in the epidermal barrier function that are nidi for colonization by microbes, especially S aureus and MRSA in particular; later, these bacteria can enter dermal vessels and then the bloodstream, leading to septicemia.10

The prevalence of MRSA in this study was 32.6% (14/43), which is high compared to other studies.2-4 Pemphigus vulgaris was the most common disorder infected by MRSA in this study (57.1% [8/14] of MRSA isolates)(Table 1), a finding that reveals that the incidence of MRSA is high among staphylococcal isolates in vesiculobullous disorders. However, the high incidence of MRSA in this study could be a reflection of the number of patients with a severe and chronic vesiculobullous disorder, such as PV, and serious drug reactions such as TEN referred to our tertiary-care center, where we get a large number of patients affected by autoimmune and drug-induced vesiculobullous disorders. Similar findings have been reported by Stryjewski et al.11

A high prevalence of MRSA in a dermatology unit has grave consequences, contributing to morbidity and mortality in particular among patients with a vesiculobullous disorder. Immunosuppressive therapy and comorbidities such as DM contribute to MRSA colonization in vesiculobullous disorders.12 Overcrowding and poor sterilization techniques in public hospitals in India may contribute to the high prevalence of MRSA seen in hospital units.

Patients with a vesiculobullous disorder who are chronic nasal carriers of MRSA are at risk for cutaneous MRSA infection, which in turn can lead to MRSA septicemia and an elevated risk of death. In this study, however, a nasal swab was positive for MRSA in only 7 patients. One patient with MRSA colonization died, which was statistically insignificant (P=1).

In this study, all MRSA strains (100%) were resistant to first-line antibiotics, such as oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefoxitin; all strains were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid.

Conclusion

Our study shows that MRSA is becoming the prominent pathogen in nosocomial infections, especially in bedridden patients, which has grave implications. The use of a prophylactic S aureus conjugate vaccine in patients with a chronic vesiculobullous disorder might be justified in the future.15 We found a high prevalence (32.6%) of MRSA in vesiculobullous disorders, no relationship between DM and MRSA colonization, PV was the most common disorder complicated by MRSA, no relationship between nasal colonization and MRSA infection, no relationship between death during the study period and MRSA infection, 100% of MRSA strains were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid, and 79.1% of MRSA strains were susceptible to amikacin.

- Nair SP. A retrospective study of mortality of pemphigus patients in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:706-709.

- Sachdev D, Amladi S, Natarj G, et al. An outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in dermatology inpatients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:377-380.

- Vijayamohan N, Nair SP. A study of the prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology inpatients. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:441-445.

- Malhotra SK, Malhotra S, Dhaliwal GS, et al. Bacterial study of pyodermas in a tertiary care dermatological center. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:358-361.

- Valencia IC, Kirsner RS, Kerdel FA. Microbiological evaluation of skin wounds: alarming trends towards antibiotic resistance in an inpatient dermatology service during a 10-year period. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:845-849.

- Lehman JS, Murell DF, Camilleri MJ, et al. Infection and infection prevention in patients treated with immunosuppressive medications for autoimmune bullous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:591-598.

- Kanwar AJ, De D. Pemphigus in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:439-449.

- Shafi M, Khatri ML, Mashima M, et al. Pemphigus: a clinical study of 109 cases from Tripoli, Libya. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1994;60:140-143.

- Torres K, Sampathkumar P. Predictors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization at hospital admission. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:1043-1047.

- Miller LG, Quan C, Shay A, et al. A prospective investigation of outcomes after hospital discharge for endemic, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:483-492.

- Stryjewski M, Chambers HF. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(suppl 5):S368-S377.

- Mutasim DF. Management of autoimmune bullous diseases: pharmacology and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:859-877.

- Cohen PR. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections: a review of epidemiology, clinical features, management, and prevention. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1-11.

- Elston DM. Methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: management principles and selection of antibiotic therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:157-164.

- Shinefield H, Black S, Fattom A, et al. Use of a Staphylococcus aureus conjugate vaccine in patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2001;346:491-496.

- Nair SP. A retrospective study of mortality of pemphigus patients in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:706-709.

- Sachdev D, Amladi S, Natarj G, et al. An outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in dermatology inpatients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:377-380.

- Vijayamohan N, Nair SP. A study of the prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology inpatients. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:441-445.

- Malhotra SK, Malhotra S, Dhaliwal GS, et al. Bacterial study of pyodermas in a tertiary care dermatological center. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:358-361.

- Valencia IC, Kirsner RS, Kerdel FA. Microbiological evaluation of skin wounds: alarming trends towards antibiotic resistance in an inpatient dermatology service during a 10-year period. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:845-849.

- Lehman JS, Murell DF, Camilleri MJ, et al. Infection and infection prevention in patients treated with immunosuppressive medications for autoimmune bullous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:591-598.

- Kanwar AJ, De D. Pemphigus in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:439-449.

- Shafi M, Khatri ML, Mashima M, et al. Pemphigus: a clinical study of 109 cases from Tripoli, Libya. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1994;60:140-143.

- Torres K, Sampathkumar P. Predictors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization at hospital admission. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:1043-1047.

- Miller LG, Quan C, Shay A, et al. A prospective investigation of outcomes after hospital discharge for endemic, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:483-492.

- Stryjewski M, Chambers HF. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(suppl 5):S368-S377.

- Mutasim DF. Management of autoimmune bullous diseases: pharmacology and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:859-877.

- Cohen PR. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections: a review of epidemiology, clinical features, management, and prevention. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1-11.

- Elston DM. Methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: management principles and selection of antibiotic therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:157-164.

- Shinefield H, Black S, Fattom A, et al. Use of a Staphylococcus aureus conjugate vaccine in patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2001;346:491-496.

Practice Points

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in vesiculobullous disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris and toxic epidermal necrolysis is known to contribute to an increase in disease-related mortality.

- Methicillin-resistant S aureus is becoming the prominent pathogen in nosocomial infections, especially in bedridden patients.

- The prevalence of MRSA in vesiculobullous disorders is high; pemphigus vulgaris is the most common vesiculobullous disorder complicated by MRSA.

- Early diagnosis of MRSA helps reduce morbidity and mortality and improves the patient’s prognosis.

Sweet Syndrome With Aseptic Splenic Abscesses and Multiple Myeloma

To the Editor: