User login

Pediatric Migraine/Headache and Sleep Disturbances

Assessment and treatment of sleep problems in pediatric patients with chronic headache is important, with several contextual and headache diagnostic factors influencing the severity of sleep disturbance, according to a recent retrospective chart review. Researchers evaluated 527 patients, aged 7-17 years, with a primary headache diagnosis of migraine (n=278), tension-type headache (TTH; n=157), and new daily persistent-headache (NDPH; n=92). Patients completed measures of disability, anxiety, and depression and their parents completed measures of sleep disturbance. They found:

- Sleep disturbance was greater in patients with TTH (10.34 ± 5.94) and NDPH (11.52 ± 6.40) than migraine (8.31 ± 5.89).

- Across patient groups, greater sleep disturbance was significantly associated with higher levels of functional disability, anxiety, and depression.

- Additionally, higher pain levels were significantly associated with greater sleep disturbance among TTH patients, with this association non-significant among the other headache groups.

- When simultaneously examining demographic, pain-related, and emotional distress factors, older age, higher levels of disability and depression, and NDPH diagnosis were all significant predictors of greater sleep disturbance.

Pediatric headache and sleep disturbance: A comparison of diagnostic groups. Headache. 2018;58(2):217-228. doi:10.1111/head.13207.

Assessment and treatment of sleep problems in pediatric patients with chronic headache is important, with several contextual and headache diagnostic factors influencing the severity of sleep disturbance, according to a recent retrospective chart review. Researchers evaluated 527 patients, aged 7-17 years, with a primary headache diagnosis of migraine (n=278), tension-type headache (TTH; n=157), and new daily persistent-headache (NDPH; n=92). Patients completed measures of disability, anxiety, and depression and their parents completed measures of sleep disturbance. They found:

- Sleep disturbance was greater in patients with TTH (10.34 ± 5.94) and NDPH (11.52 ± 6.40) than migraine (8.31 ± 5.89).

- Across patient groups, greater sleep disturbance was significantly associated with higher levels of functional disability, anxiety, and depression.

- Additionally, higher pain levels were significantly associated with greater sleep disturbance among TTH patients, with this association non-significant among the other headache groups.

- When simultaneously examining demographic, pain-related, and emotional distress factors, older age, higher levels of disability and depression, and NDPH diagnosis were all significant predictors of greater sleep disturbance.

Pediatric headache and sleep disturbance: A comparison of diagnostic groups. Headache. 2018;58(2):217-228. doi:10.1111/head.13207.

Assessment and treatment of sleep problems in pediatric patients with chronic headache is important, with several contextual and headache diagnostic factors influencing the severity of sleep disturbance, according to a recent retrospective chart review. Researchers evaluated 527 patients, aged 7-17 years, with a primary headache diagnosis of migraine (n=278), tension-type headache (TTH; n=157), and new daily persistent-headache (NDPH; n=92). Patients completed measures of disability, anxiety, and depression and their parents completed measures of sleep disturbance. They found:

- Sleep disturbance was greater in patients with TTH (10.34 ± 5.94) and NDPH (11.52 ± 6.40) than migraine (8.31 ± 5.89).

- Across patient groups, greater sleep disturbance was significantly associated with higher levels of functional disability, anxiety, and depression.

- Additionally, higher pain levels were significantly associated with greater sleep disturbance among TTH patients, with this association non-significant among the other headache groups.

- When simultaneously examining demographic, pain-related, and emotional distress factors, older age, higher levels of disability and depression, and NDPH diagnosis were all significant predictors of greater sleep disturbance.

Pediatric headache and sleep disturbance: A comparison of diagnostic groups. Headache. 2018;58(2):217-228. doi:10.1111/head.13207.

Hidradenitis suppurativa: An underdiagnosed skin problem of women

In recent decades the practice of medicine has drifted away from the performance of a physical examination during most patient encounters and evolved toward the more intensive use of history, imaging, and laboratory studies to guide management decisions. For example, it is common for a woman to present to an emergency department with abdominal or pelvic pain and undergo a computerized tomography scan before an abdominal and pelvic examination is performed. Some authorities believe that the trend to reduce the importance of the physical examination has gone way too far and resulted in a reduction in the quality of health care.1,2

Many skin diseases only can be diagnosed by having the patient disrobe and examining the skin. Gynecologists are uniquely positioned to diagnose important skin diseases because, while performing a reproductive health examination, they may be the first clinicians to directly examine the anogenital area and inner thighs. Skin diseases that are prevalent and can be diagnosed while performing an examination of the anogenital region include lichen sclerosus (LS) and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). The prevalence of each of these conditions is in the range of 1% to 4% of women.3–5

Failure to examine the anogenital area and insufficient attention to the early signs of LS and HS may result in a long delay in the diagnosis.6 In 1 survey, of 517 patients with HS, there was a 7-year interval between the onset of the disease and the diagnosis by a clinician.7 Delay in diagnosis results in increased scarring, which makes it more difficult to effectively treat the disease. In this editorial, I will focus on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of HS.

Diagnosis, presentation, and staging

Hidradenitis suppurativa (from the Greek, hidros means sweat and aden means glands) is a painful, chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disorder affecting the follicular unit. It is manifested by nodules, pustules, sinus tracts, and scars, usually in intertriginous areas. The diagnosis is made by history and physical examination. The 3 cardinal features of HS are 1) deep-seated nodules, comedones, and fibrosis; 2) typical anatomic location of the lesions in the axillae, inguinocrural, and anogenital regions, and 3) chronic relapsing course.8

Disease severity is often assessed using the Hurley staging system:

- stage I: abscess formation without sinus tracts or scarring (FIGURE)

- stage II: recurrent abscesses with tract formation and scarring, widely separated lesions

- stage III: diffuse or near-diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses.

In one report, stage I, II, and III disease was diagnosed in 65%, 31%, and 4% of cases, respectively, indicating that most HS is diagnosed instage I and suitable for treatment by a gynecologist.9

HS typically presents after puberty and women are more commonly affected than men. In one case series including 232 women with HS the regions most commonly affected were: axillae, inguinofemoral, urogenital, and buttocks in 79%, 77%, 51%, and 40% of cases, respectively.10 Risk factors for HS include obesity, cigarette smoking, tight fitting clothing, and chronic friction across the affected skin area.5

Pathogenesis

The pathophysiology of HS is thought to begin with occlusion of the follicle, resulting in follicle rupture deep in the dermis, thereby triggering inflammation, bacterial infection, and scarring. Dermal areas affected by HS have high concentrations of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha, interleukin (IL)-1-beta, IL-23, and IL-32.11,12 Once HS becomes an established process, it is difficult to treat because the dermal inflammatory process and scarring provides a microenvironment that facilitates disease progression. Hence early detection and treatment may result in optimal long-term outcomes.

Read about management of HS by stage

Treatment

Many recommended treatments for HS have not been formally tested in large randomized trials. A recent Cochrane review identified only 12 high-quality trials and the median number of participants was 27 per trial.13 Consequently, most treatment recommendations are based on expert opinion. Recommended treatments include smoking cessation, weight loss, topical and systemic antibiotics, antiandrogens, anti-inflammatory biologics (adalimumab and infliximab), and surgery. Smoking cessation and weight loss are strongly recommended in the initial treatment of HS. Bariatric surgery and significant postprocedure weight loss has been reported to cause a reduction in disease activity.14

Stage I management. For the initial treatment of stage I HS, clindamycin gel 1% applied twice daily to affected areas is recommended.15 Recommended oral antibiotic treatments include tetracycline 500 mg twice daily for 12 weeks16 or doxycycline 100 mg or 200 mg given daily for 10 weeks or clindamycin 300 mg twice daily plus rifampicin 600 mg once daily for 10 weeks.17,18 These antibiotics have both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects.

Hormonal interventions that suppress androgen production or action may help reduce HS disease activity. For women with HS who also need contraception, an estrogen-progestin contraceptive may help reduce HS disease activity in up to 50% of individuals.19 The 5-alpha reductase inhibitor finasteride, at high doses (5 to 15 mg daily), has been reported to reduce HS disease activity.20,21 Finasteride is a teratogen, and the FDA strongly recommends against its use by women. Spironolactone, an anti-mineralocorticoid and antiandrogen, at a dose of 100 mg daily has been reported to reduce disease activity in about 50% of treated individuals and is FDA approved for use in women.22 Among reproductive-age women, spironolactone, which is a teratogen, only should be prescribed to women using an effective form of contraceptive. HS is often associated with obesity and insulin resistance. Metformin 500 mg three times daily has been reported to decrease disease activity.23,24

Stage II or III management. For Hurley stage II or III HS, referral to a dermatologist is warranted. There is evidence that too few people with HS are referred to a dermatologist.25 For severe HS resistant to oral medications, anti-TNF monoclonal antibody treatment with adalimumab (Humira) or infliximab (Remicade) is effective. Adalimumab is administered by subcutaneous injection and is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved to treat HS. Following a loading dose, adalimumab is administered weekly at a dose of 40 mg.26 Infliximab, which is not FDA approved to treat HS, is administered by intravenous infusion at a dose of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6, and then every 8 weeks.27

Surgical management. HS is sometimes treated surgically with laser destruction of lesions, punch debridement, or wide excision of diseased tissue.28,29 There are no high quality clinical trials of surgical treatment of HS. Punch debridement can be performed using a 5- to 7-mm circular skin punch to deeply excise the inflamed follicle. Wide excision can be followed by wound closure with advancement flaps or split-thickness skin grafting. Wound closure by secondary intention is possible but requires many weeks or months of burdensome dressing changes to complete the healing process. Recurrence is common following surgical therapy and ranges from 30% with deroofing or laser treatment to 6% following wide excision and skin graft closure of the wound.30

Physical examination vital to early diagnosis

Delay in diagnosis of an active disease process has many causes, including nonperformance of a physical examination. In a web-based survey of physicians’ experiences with oversights related to the physical examination, 3 problems frequently reported were: nonperformance of any portion of the physical examination, failure to undress the patient to examine the skin, and failure to examine the abdomen and anogenital region in a patient with abdominal or pelvic pain.31 Oversights in the physical examination frequently caused a delay in diagnosis and treatment. With both LS and HS, patients may not recognize that they have a skin disease, or they may be embarrassed to show a clinician a skin change they have noticed. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to achieving a good outcome and make a tremendous difference in the quality of life for the patient. Physical examination is a skill we have learned through diligent study and experience in practice. We can use these skills to greatly improve the lives of our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In recent decades the practice of medicine has drifted away from the performance of a physical examination during most patient encounters and evolved toward the more intensive use of history, imaging, and laboratory studies to guide management decisions. For example, it is common for a woman to present to an emergency department with abdominal or pelvic pain and undergo a computerized tomography scan before an abdominal and pelvic examination is performed. Some authorities believe that the trend to reduce the importance of the physical examination has gone way too far and resulted in a reduction in the quality of health care.1,2

Many skin diseases only can be diagnosed by having the patient disrobe and examining the skin. Gynecologists are uniquely positioned to diagnose important skin diseases because, while performing a reproductive health examination, they may be the first clinicians to directly examine the anogenital area and inner thighs. Skin diseases that are prevalent and can be diagnosed while performing an examination of the anogenital region include lichen sclerosus (LS) and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). The prevalence of each of these conditions is in the range of 1% to 4% of women.3–5

Failure to examine the anogenital area and insufficient attention to the early signs of LS and HS may result in a long delay in the diagnosis.6 In 1 survey, of 517 patients with HS, there was a 7-year interval between the onset of the disease and the diagnosis by a clinician.7 Delay in diagnosis results in increased scarring, which makes it more difficult to effectively treat the disease. In this editorial, I will focus on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of HS.

Diagnosis, presentation, and staging

Hidradenitis suppurativa (from the Greek, hidros means sweat and aden means glands) is a painful, chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disorder affecting the follicular unit. It is manifested by nodules, pustules, sinus tracts, and scars, usually in intertriginous areas. The diagnosis is made by history and physical examination. The 3 cardinal features of HS are 1) deep-seated nodules, comedones, and fibrosis; 2) typical anatomic location of the lesions in the axillae, inguinocrural, and anogenital regions, and 3) chronic relapsing course.8

Disease severity is often assessed using the Hurley staging system:

- stage I: abscess formation without sinus tracts or scarring (FIGURE)

- stage II: recurrent abscesses with tract formation and scarring, widely separated lesions

- stage III: diffuse or near-diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses.

In one report, stage I, II, and III disease was diagnosed in 65%, 31%, and 4% of cases, respectively, indicating that most HS is diagnosed instage I and suitable for treatment by a gynecologist.9

HS typically presents after puberty and women are more commonly affected than men. In one case series including 232 women with HS the regions most commonly affected were: axillae, inguinofemoral, urogenital, and buttocks in 79%, 77%, 51%, and 40% of cases, respectively.10 Risk factors for HS include obesity, cigarette smoking, tight fitting clothing, and chronic friction across the affected skin area.5

Pathogenesis

The pathophysiology of HS is thought to begin with occlusion of the follicle, resulting in follicle rupture deep in the dermis, thereby triggering inflammation, bacterial infection, and scarring. Dermal areas affected by HS have high concentrations of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha, interleukin (IL)-1-beta, IL-23, and IL-32.11,12 Once HS becomes an established process, it is difficult to treat because the dermal inflammatory process and scarring provides a microenvironment that facilitates disease progression. Hence early detection and treatment may result in optimal long-term outcomes.

Read about management of HS by stage

Treatment

Many recommended treatments for HS have not been formally tested in large randomized trials. A recent Cochrane review identified only 12 high-quality trials and the median number of participants was 27 per trial.13 Consequently, most treatment recommendations are based on expert opinion. Recommended treatments include smoking cessation, weight loss, topical and systemic antibiotics, antiandrogens, anti-inflammatory biologics (adalimumab and infliximab), and surgery. Smoking cessation and weight loss are strongly recommended in the initial treatment of HS. Bariatric surgery and significant postprocedure weight loss has been reported to cause a reduction in disease activity.14

Stage I management. For the initial treatment of stage I HS, clindamycin gel 1% applied twice daily to affected areas is recommended.15 Recommended oral antibiotic treatments include tetracycline 500 mg twice daily for 12 weeks16 or doxycycline 100 mg or 200 mg given daily for 10 weeks or clindamycin 300 mg twice daily plus rifampicin 600 mg once daily for 10 weeks.17,18 These antibiotics have both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects.

Hormonal interventions that suppress androgen production or action may help reduce HS disease activity. For women with HS who also need contraception, an estrogen-progestin contraceptive may help reduce HS disease activity in up to 50% of individuals.19 The 5-alpha reductase inhibitor finasteride, at high doses (5 to 15 mg daily), has been reported to reduce HS disease activity.20,21 Finasteride is a teratogen, and the FDA strongly recommends against its use by women. Spironolactone, an anti-mineralocorticoid and antiandrogen, at a dose of 100 mg daily has been reported to reduce disease activity in about 50% of treated individuals and is FDA approved for use in women.22 Among reproductive-age women, spironolactone, which is a teratogen, only should be prescribed to women using an effective form of contraceptive. HS is often associated with obesity and insulin resistance. Metformin 500 mg three times daily has been reported to decrease disease activity.23,24

Stage II or III management. For Hurley stage II or III HS, referral to a dermatologist is warranted. There is evidence that too few people with HS are referred to a dermatologist.25 For severe HS resistant to oral medications, anti-TNF monoclonal antibody treatment with adalimumab (Humira) or infliximab (Remicade) is effective. Adalimumab is administered by subcutaneous injection and is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved to treat HS. Following a loading dose, adalimumab is administered weekly at a dose of 40 mg.26 Infliximab, which is not FDA approved to treat HS, is administered by intravenous infusion at a dose of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6, and then every 8 weeks.27

Surgical management. HS is sometimes treated surgically with laser destruction of lesions, punch debridement, or wide excision of diseased tissue.28,29 There are no high quality clinical trials of surgical treatment of HS. Punch debridement can be performed using a 5- to 7-mm circular skin punch to deeply excise the inflamed follicle. Wide excision can be followed by wound closure with advancement flaps or split-thickness skin grafting. Wound closure by secondary intention is possible but requires many weeks or months of burdensome dressing changes to complete the healing process. Recurrence is common following surgical therapy and ranges from 30% with deroofing or laser treatment to 6% following wide excision and skin graft closure of the wound.30

Physical examination vital to early diagnosis

Delay in diagnosis of an active disease process has many causes, including nonperformance of a physical examination. In a web-based survey of physicians’ experiences with oversights related to the physical examination, 3 problems frequently reported were: nonperformance of any portion of the physical examination, failure to undress the patient to examine the skin, and failure to examine the abdomen and anogenital region in a patient with abdominal or pelvic pain.31 Oversights in the physical examination frequently caused a delay in diagnosis and treatment. With both LS and HS, patients may not recognize that they have a skin disease, or they may be embarrassed to show a clinician a skin change they have noticed. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to achieving a good outcome and make a tremendous difference in the quality of life for the patient. Physical examination is a skill we have learned through diligent study and experience in practice. We can use these skills to greatly improve the lives of our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In recent decades the practice of medicine has drifted away from the performance of a physical examination during most patient encounters and evolved toward the more intensive use of history, imaging, and laboratory studies to guide management decisions. For example, it is common for a woman to present to an emergency department with abdominal or pelvic pain and undergo a computerized tomography scan before an abdominal and pelvic examination is performed. Some authorities believe that the trend to reduce the importance of the physical examination has gone way too far and resulted in a reduction in the quality of health care.1,2

Many skin diseases only can be diagnosed by having the patient disrobe and examining the skin. Gynecologists are uniquely positioned to diagnose important skin diseases because, while performing a reproductive health examination, they may be the first clinicians to directly examine the anogenital area and inner thighs. Skin diseases that are prevalent and can be diagnosed while performing an examination of the anogenital region include lichen sclerosus (LS) and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). The prevalence of each of these conditions is in the range of 1% to 4% of women.3–5

Failure to examine the anogenital area and insufficient attention to the early signs of LS and HS may result in a long delay in the diagnosis.6 In 1 survey, of 517 patients with HS, there was a 7-year interval between the onset of the disease and the diagnosis by a clinician.7 Delay in diagnosis results in increased scarring, which makes it more difficult to effectively treat the disease. In this editorial, I will focus on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of HS.

Diagnosis, presentation, and staging

Hidradenitis suppurativa (from the Greek, hidros means sweat and aden means glands) is a painful, chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disorder affecting the follicular unit. It is manifested by nodules, pustules, sinus tracts, and scars, usually in intertriginous areas. The diagnosis is made by history and physical examination. The 3 cardinal features of HS are 1) deep-seated nodules, comedones, and fibrosis; 2) typical anatomic location of the lesions in the axillae, inguinocrural, and anogenital regions, and 3) chronic relapsing course.8

Disease severity is often assessed using the Hurley staging system:

- stage I: abscess formation without sinus tracts or scarring (FIGURE)

- stage II: recurrent abscesses with tract formation and scarring, widely separated lesions

- stage III: diffuse or near-diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses.

In one report, stage I, II, and III disease was diagnosed in 65%, 31%, and 4% of cases, respectively, indicating that most HS is diagnosed instage I and suitable for treatment by a gynecologist.9

HS typically presents after puberty and women are more commonly affected than men. In one case series including 232 women with HS the regions most commonly affected were: axillae, inguinofemoral, urogenital, and buttocks in 79%, 77%, 51%, and 40% of cases, respectively.10 Risk factors for HS include obesity, cigarette smoking, tight fitting clothing, and chronic friction across the affected skin area.5

Pathogenesis

The pathophysiology of HS is thought to begin with occlusion of the follicle, resulting in follicle rupture deep in the dermis, thereby triggering inflammation, bacterial infection, and scarring. Dermal areas affected by HS have high concentrations of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha, interleukin (IL)-1-beta, IL-23, and IL-32.11,12 Once HS becomes an established process, it is difficult to treat because the dermal inflammatory process and scarring provides a microenvironment that facilitates disease progression. Hence early detection and treatment may result in optimal long-term outcomes.

Read about management of HS by stage

Treatment

Many recommended treatments for HS have not been formally tested in large randomized trials. A recent Cochrane review identified only 12 high-quality trials and the median number of participants was 27 per trial.13 Consequently, most treatment recommendations are based on expert opinion. Recommended treatments include smoking cessation, weight loss, topical and systemic antibiotics, antiandrogens, anti-inflammatory biologics (adalimumab and infliximab), and surgery. Smoking cessation and weight loss are strongly recommended in the initial treatment of HS. Bariatric surgery and significant postprocedure weight loss has been reported to cause a reduction in disease activity.14

Stage I management. For the initial treatment of stage I HS, clindamycin gel 1% applied twice daily to affected areas is recommended.15 Recommended oral antibiotic treatments include tetracycline 500 mg twice daily for 12 weeks16 or doxycycline 100 mg or 200 mg given daily for 10 weeks or clindamycin 300 mg twice daily plus rifampicin 600 mg once daily for 10 weeks.17,18 These antibiotics have both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects.

Hormonal interventions that suppress androgen production or action may help reduce HS disease activity. For women with HS who also need contraception, an estrogen-progestin contraceptive may help reduce HS disease activity in up to 50% of individuals.19 The 5-alpha reductase inhibitor finasteride, at high doses (5 to 15 mg daily), has been reported to reduce HS disease activity.20,21 Finasteride is a teratogen, and the FDA strongly recommends against its use by women. Spironolactone, an anti-mineralocorticoid and antiandrogen, at a dose of 100 mg daily has been reported to reduce disease activity in about 50% of treated individuals and is FDA approved for use in women.22 Among reproductive-age women, spironolactone, which is a teratogen, only should be prescribed to women using an effective form of contraceptive. HS is often associated with obesity and insulin resistance. Metformin 500 mg three times daily has been reported to decrease disease activity.23,24

Stage II or III management. For Hurley stage II or III HS, referral to a dermatologist is warranted. There is evidence that too few people with HS are referred to a dermatologist.25 For severe HS resistant to oral medications, anti-TNF monoclonal antibody treatment with adalimumab (Humira) or infliximab (Remicade) is effective. Adalimumab is administered by subcutaneous injection and is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved to treat HS. Following a loading dose, adalimumab is administered weekly at a dose of 40 mg.26 Infliximab, which is not FDA approved to treat HS, is administered by intravenous infusion at a dose of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6, and then every 8 weeks.27

Surgical management. HS is sometimes treated surgically with laser destruction of lesions, punch debridement, or wide excision of diseased tissue.28,29 There are no high quality clinical trials of surgical treatment of HS. Punch debridement can be performed using a 5- to 7-mm circular skin punch to deeply excise the inflamed follicle. Wide excision can be followed by wound closure with advancement flaps or split-thickness skin grafting. Wound closure by secondary intention is possible but requires many weeks or months of burdensome dressing changes to complete the healing process. Recurrence is common following surgical therapy and ranges from 30% with deroofing or laser treatment to 6% following wide excision and skin graft closure of the wound.30

Physical examination vital to early diagnosis

Delay in diagnosis of an active disease process has many causes, including nonperformance of a physical examination. In a web-based survey of physicians’ experiences with oversights related to the physical examination, 3 problems frequently reported were: nonperformance of any portion of the physical examination, failure to undress the patient to examine the skin, and failure to examine the abdomen and anogenital region in a patient with abdominal or pelvic pain.31 Oversights in the physical examination frequently caused a delay in diagnosis and treatment. With both LS and HS, patients may not recognize that they have a skin disease, or they may be embarrassed to show a clinician a skin change they have noticed. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to achieving a good outcome and make a tremendous difference in the quality of life for the patient. Physical examination is a skill we have learned through diligent study and experience in practice. We can use these skills to greatly improve the lives of our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Migraine Severity, Obesity Link Examined in Women

Associations of migraine severity and presence of associated features with inhibitory control varied by body mass index (BMI) in overweight/obese women with migraine, according to a recent study. These findings, therefore, warrant consideration of weight status in clarifying the role of migraine in executive functioning. Women (n=124) aged 18–50 years with overweight/obesity BMI=35.1 ± 6.4 kg/m2 and migraine completed a 28-day smartphone-based headache diary assessing migraine headache severity (attack frequency, pain intensity) and frequency of associated features (aura, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea). They then completed computerized measures of inhibitory control during an interictal (headache-free) period. Researchers found:

- Participants with higher migraine attack frequency performed worse on the Flanker test (accuracy and reaction time).

- Migraine attack frequency and pain intensity interacted with BMI to predict slower Stroop and/or Flanker Reaction Time (RT).

- More frequent photophobia, phonophobia, and aura were independently related to slower RT on the Stroop and/or Flanker tests, and BMI moderated the relationship between the occurrence of aura and Stroop RT.

The role of migraine headache severity, associated features and interactions with overweight/obesity in inhibitory control. Int J Neurosci. 2018;128(1):63-70. doi:10.1080/00207454.2017.1366474.

Associations of migraine severity and presence of associated features with inhibitory control varied by body mass index (BMI) in overweight/obese women with migraine, according to a recent study. These findings, therefore, warrant consideration of weight status in clarifying the role of migraine in executive functioning. Women (n=124) aged 18–50 years with overweight/obesity BMI=35.1 ± 6.4 kg/m2 and migraine completed a 28-day smartphone-based headache diary assessing migraine headache severity (attack frequency, pain intensity) and frequency of associated features (aura, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea). They then completed computerized measures of inhibitory control during an interictal (headache-free) period. Researchers found:

- Participants with higher migraine attack frequency performed worse on the Flanker test (accuracy and reaction time).

- Migraine attack frequency and pain intensity interacted with BMI to predict slower Stroop and/or Flanker Reaction Time (RT).

- More frequent photophobia, phonophobia, and aura were independently related to slower RT on the Stroop and/or Flanker tests, and BMI moderated the relationship between the occurrence of aura and Stroop RT.

The role of migraine headache severity, associated features and interactions with overweight/obesity in inhibitory control. Int J Neurosci. 2018;128(1):63-70. doi:10.1080/00207454.2017.1366474.

Associations of migraine severity and presence of associated features with inhibitory control varied by body mass index (BMI) in overweight/obese women with migraine, according to a recent study. These findings, therefore, warrant consideration of weight status in clarifying the role of migraine in executive functioning. Women (n=124) aged 18–50 years with overweight/obesity BMI=35.1 ± 6.4 kg/m2 and migraine completed a 28-day smartphone-based headache diary assessing migraine headache severity (attack frequency, pain intensity) and frequency of associated features (aura, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea). They then completed computerized measures of inhibitory control during an interictal (headache-free) period. Researchers found:

- Participants with higher migraine attack frequency performed worse on the Flanker test (accuracy and reaction time).

- Migraine attack frequency and pain intensity interacted with BMI to predict slower Stroop and/or Flanker Reaction Time (RT).

- More frequent photophobia, phonophobia, and aura were independently related to slower RT on the Stroop and/or Flanker tests, and BMI moderated the relationship between the occurrence of aura and Stroop RT.

The role of migraine headache severity, associated features and interactions with overweight/obesity in inhibitory control. Int J Neurosci. 2018;128(1):63-70. doi:10.1080/00207454.2017.1366474.

Carcinoma Erysipeloides of Papillary Serous Ovarian Cancer Mimicking Cellulitis of the Abdominal Wall

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIC ovarian cancer presented with progressing abdominal erythema and pain of 1 month’s duration. She had been diagnosed 4 years prior with grade 3, poorly differentiated papillary serous carcinoma involving the bilateral ovaries, uterine tubes, uterus, and omentum with lymphovascular invasion. She underwent tumor resection and debulking followed by paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy. The cancer recurred 2 years later with carcinomatous ascites. She declined chemotherapy but underwent therapeutic paracentesis.

One month prior to presentation, the patient developed a small, tender, erythematous patch on the abdomen. Her primary physician started her on cephalexin for presumed cellulitis without improvement. The erythema continued to spread on the abdomen with worsening pain, which prompted her presentation to the emergency department. She was admitted and started on intravenous vancomycin.

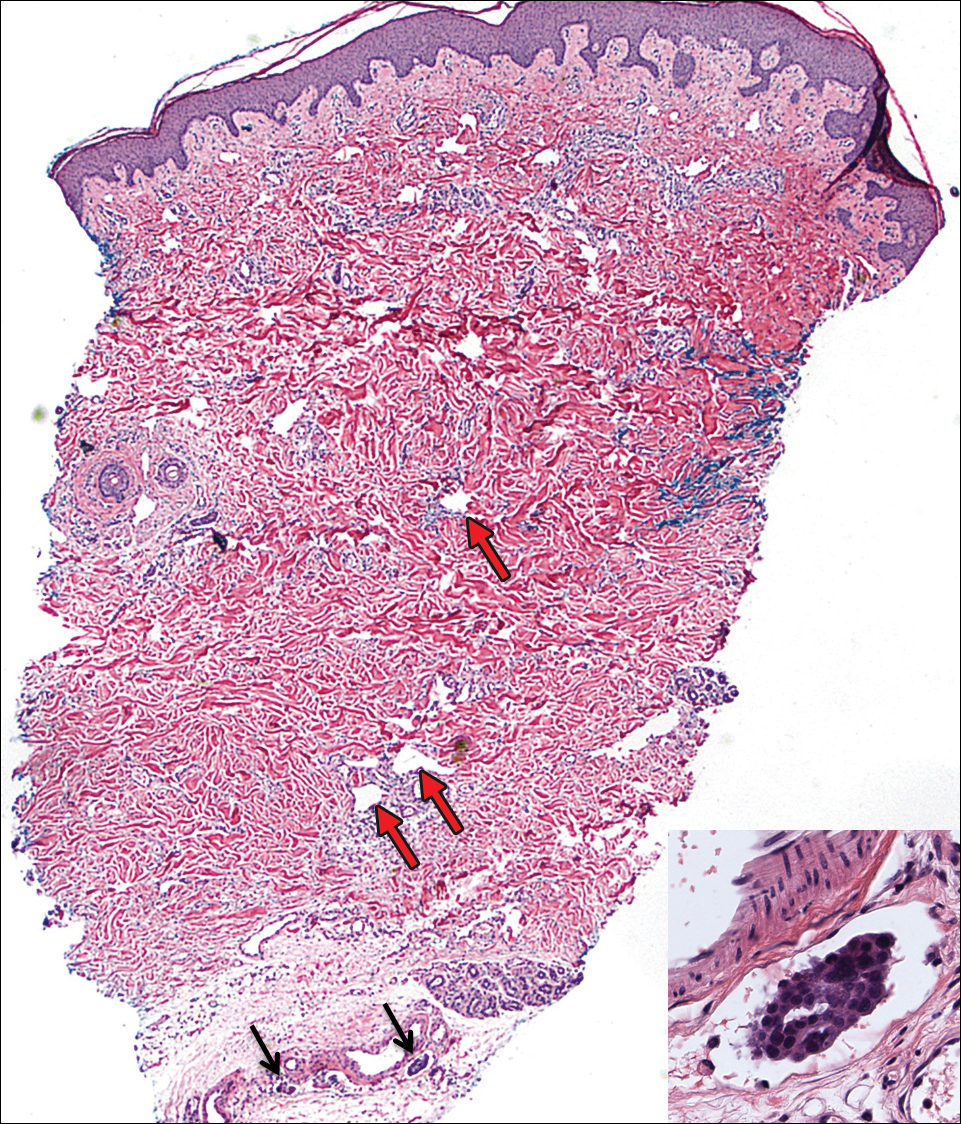

On admission to the hospital, the patient was cachexic and afebrile with a white blood cell count of 10,400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, 15×20-cm, erythematous, blanchable, indurated plaque in the periumbilical region (Figure 1). The plaque was tender to palpation with guarding but no increased warmth. Punch biopsies of the abdominal skin revealed carcinoma within the lymphatic channels in the deep dermis and dilated lymphatics throughout the overlying dermis (Figure 2). These findings were diagnostic for carcinoma erysipeloides. Tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Vancomycin was discontinued, and she was discharged with pain medication. She declined chemotherapy due to the potential side effects and elected to continue symptomatic management with palliative paracentesis. After she was discharged, she underwent a tunneled pleural catheterization for recurrent malignant pleural effusions.

Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous metastasis secondary to internal malignancy that presents as well-demarcated areas of erythema and is sometimes misdiagnosed as cellulitis or erysipelas. Histology is notable for lymphovascular congestion without inflammation. Carcinoma erysipeloides most commonly is associated with breast cancer, but it also has been described in cancers of the prostate, larynx, stomach, lungs, thyroid, parotid gland, fallopian tubes, cervix, pancreas, and metastatic melanoma.1-5 While the pathogenesis of carcinoma erysipeloides is poorly understood, it is thought to occur by direct spread of tumor cells from the lymph nodes to the cutaneous lymphatics, causing obstruction and edema.

Ovarian cancer has the highest mortality of all gynecologic cancers and often is associated with delayed diagnosis. Cutaneous metastasis is a late manifestation often presenting as subcutaneous nodules.6,7 Carcinoma erysipeloides is an even rarer presentation of ovarian cancer, with a poor prognosis and a median survival of 18 months.8 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term carcinoma erysipeloides revealed 9 cases of carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian cancer: 1 describing erythematous papules, plaques, and zosteriform vesicles on the upper thighs to the lower abdomen,9 and 8 describing erythematous plaques on the breasts.8,10 We report a case of carcinoma erysipeloides associated with stage IIIc ovarian cancer localized to the abdominal wall mimicking cellulitis. Our report reminds clinicians of this important diagnosis in ovarian cancer and of the importance of a skin biopsy to expedite a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry using ovarian tumor markers (eg, paired-box gene 8, cancer antigen 125) is an additional tool to accurately identify malignant cells in skin biopsy.8,10 Once diagnosed, primary treatment for carcinoma erysipeloides is treatment of the underlying malignancy.

- Cormio G, Capotorto M, Di Vagno G, et al. Skin metastases in ovarian carcinoma: a report of nine cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:682-685.

- Kim MK, Kim SH, Lee YY, et al. Metastatic skin lesions on lower extremities in a patient with recurrent serous papillary ovarian carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:142-145.

- Karmali S, Rudmik L, Temple W, et al. Melanoma erysipeloides. Can J Surg. 2005;48:159-160.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides of the breast in a patient with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:575-576.

- Hazelrigg DE, Rudolph AH. Inflammatory metastic carcinoma. carcinoma erysipelatoides. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:69-70.

- Cowan LJ, Roller JI, Connelly PJ, et al. Extraovarian stage IV peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma presenting as an asymptomatic skin lesion—a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57:433-435.

- Schonmann R, Altaras M, Biron T, et al. Inflammatory skin metastases from ovarian carcinoma—a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:670-672.

- Klein RL, Brown AR, Gomez-Castro CM, et al. Ovarian cancer metastatic to the breast presenting as inflammatory breast cancer: a case report and literature review. J Cancer. 2010;1:27-31.

- Lee HC, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian clear-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5828-5830.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Photo quiz. rash in a patient with ovarian cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:538, 575-576.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIC ovarian cancer presented with progressing abdominal erythema and pain of 1 month’s duration. She had been diagnosed 4 years prior with grade 3, poorly differentiated papillary serous carcinoma involving the bilateral ovaries, uterine tubes, uterus, and omentum with lymphovascular invasion. She underwent tumor resection and debulking followed by paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy. The cancer recurred 2 years later with carcinomatous ascites. She declined chemotherapy but underwent therapeutic paracentesis.

One month prior to presentation, the patient developed a small, tender, erythematous patch on the abdomen. Her primary physician started her on cephalexin for presumed cellulitis without improvement. The erythema continued to spread on the abdomen with worsening pain, which prompted her presentation to the emergency department. She was admitted and started on intravenous vancomycin.

On admission to the hospital, the patient was cachexic and afebrile with a white blood cell count of 10,400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, 15×20-cm, erythematous, blanchable, indurated plaque in the periumbilical region (Figure 1). The plaque was tender to palpation with guarding but no increased warmth. Punch biopsies of the abdominal skin revealed carcinoma within the lymphatic channels in the deep dermis and dilated lymphatics throughout the overlying dermis (Figure 2). These findings were diagnostic for carcinoma erysipeloides. Tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Vancomycin was discontinued, and she was discharged with pain medication. She declined chemotherapy due to the potential side effects and elected to continue symptomatic management with palliative paracentesis. After she was discharged, she underwent a tunneled pleural catheterization for recurrent malignant pleural effusions.

Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous metastasis secondary to internal malignancy that presents as well-demarcated areas of erythema and is sometimes misdiagnosed as cellulitis or erysipelas. Histology is notable for lymphovascular congestion without inflammation. Carcinoma erysipeloides most commonly is associated with breast cancer, but it also has been described in cancers of the prostate, larynx, stomach, lungs, thyroid, parotid gland, fallopian tubes, cervix, pancreas, and metastatic melanoma.1-5 While the pathogenesis of carcinoma erysipeloides is poorly understood, it is thought to occur by direct spread of tumor cells from the lymph nodes to the cutaneous lymphatics, causing obstruction and edema.

Ovarian cancer has the highest mortality of all gynecologic cancers and often is associated with delayed diagnosis. Cutaneous metastasis is a late manifestation often presenting as subcutaneous nodules.6,7 Carcinoma erysipeloides is an even rarer presentation of ovarian cancer, with a poor prognosis and a median survival of 18 months.8 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term carcinoma erysipeloides revealed 9 cases of carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian cancer: 1 describing erythematous papules, plaques, and zosteriform vesicles on the upper thighs to the lower abdomen,9 and 8 describing erythematous plaques on the breasts.8,10 We report a case of carcinoma erysipeloides associated with stage IIIc ovarian cancer localized to the abdominal wall mimicking cellulitis. Our report reminds clinicians of this important diagnosis in ovarian cancer and of the importance of a skin biopsy to expedite a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry using ovarian tumor markers (eg, paired-box gene 8, cancer antigen 125) is an additional tool to accurately identify malignant cells in skin biopsy.8,10 Once diagnosed, primary treatment for carcinoma erysipeloides is treatment of the underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIC ovarian cancer presented with progressing abdominal erythema and pain of 1 month’s duration. She had been diagnosed 4 years prior with grade 3, poorly differentiated papillary serous carcinoma involving the bilateral ovaries, uterine tubes, uterus, and omentum with lymphovascular invasion. She underwent tumor resection and debulking followed by paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy. The cancer recurred 2 years later with carcinomatous ascites. She declined chemotherapy but underwent therapeutic paracentesis.

One month prior to presentation, the patient developed a small, tender, erythematous patch on the abdomen. Her primary physician started her on cephalexin for presumed cellulitis without improvement. The erythema continued to spread on the abdomen with worsening pain, which prompted her presentation to the emergency department. She was admitted and started on intravenous vancomycin.

On admission to the hospital, the patient was cachexic and afebrile with a white blood cell count of 10,400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, 15×20-cm, erythematous, blanchable, indurated plaque in the periumbilical region (Figure 1). The plaque was tender to palpation with guarding but no increased warmth. Punch biopsies of the abdominal skin revealed carcinoma within the lymphatic channels in the deep dermis and dilated lymphatics throughout the overlying dermis (Figure 2). These findings were diagnostic for carcinoma erysipeloides. Tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Vancomycin was discontinued, and she was discharged with pain medication. She declined chemotherapy due to the potential side effects and elected to continue symptomatic management with palliative paracentesis. After she was discharged, she underwent a tunneled pleural catheterization for recurrent malignant pleural effusions.

Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous metastasis secondary to internal malignancy that presents as well-demarcated areas of erythema and is sometimes misdiagnosed as cellulitis or erysipelas. Histology is notable for lymphovascular congestion without inflammation. Carcinoma erysipeloides most commonly is associated with breast cancer, but it also has been described in cancers of the prostate, larynx, stomach, lungs, thyroid, parotid gland, fallopian tubes, cervix, pancreas, and metastatic melanoma.1-5 While the pathogenesis of carcinoma erysipeloides is poorly understood, it is thought to occur by direct spread of tumor cells from the lymph nodes to the cutaneous lymphatics, causing obstruction and edema.

Ovarian cancer has the highest mortality of all gynecologic cancers and often is associated with delayed diagnosis. Cutaneous metastasis is a late manifestation often presenting as subcutaneous nodules.6,7 Carcinoma erysipeloides is an even rarer presentation of ovarian cancer, with a poor prognosis and a median survival of 18 months.8 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term carcinoma erysipeloides revealed 9 cases of carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian cancer: 1 describing erythematous papules, plaques, and zosteriform vesicles on the upper thighs to the lower abdomen,9 and 8 describing erythematous plaques on the breasts.8,10 We report a case of carcinoma erysipeloides associated with stage IIIc ovarian cancer localized to the abdominal wall mimicking cellulitis. Our report reminds clinicians of this important diagnosis in ovarian cancer and of the importance of a skin biopsy to expedite a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry using ovarian tumor markers (eg, paired-box gene 8, cancer antigen 125) is an additional tool to accurately identify malignant cells in skin biopsy.8,10 Once diagnosed, primary treatment for carcinoma erysipeloides is treatment of the underlying malignancy.

- Cormio G, Capotorto M, Di Vagno G, et al. Skin metastases in ovarian carcinoma: a report of nine cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:682-685.

- Kim MK, Kim SH, Lee YY, et al. Metastatic skin lesions on lower extremities in a patient with recurrent serous papillary ovarian carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:142-145.

- Karmali S, Rudmik L, Temple W, et al. Melanoma erysipeloides. Can J Surg. 2005;48:159-160.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides of the breast in a patient with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:575-576.

- Hazelrigg DE, Rudolph AH. Inflammatory metastic carcinoma. carcinoma erysipelatoides. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:69-70.

- Cowan LJ, Roller JI, Connelly PJ, et al. Extraovarian stage IV peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma presenting as an asymptomatic skin lesion—a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57:433-435.

- Schonmann R, Altaras M, Biron T, et al. Inflammatory skin metastases from ovarian carcinoma—a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:670-672.

- Klein RL, Brown AR, Gomez-Castro CM, et al. Ovarian cancer metastatic to the breast presenting as inflammatory breast cancer: a case report and literature review. J Cancer. 2010;1:27-31.

- Lee HC, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian clear-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5828-5830.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Photo quiz. rash in a patient with ovarian cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:538, 575-576.

- Cormio G, Capotorto M, Di Vagno G, et al. Skin metastases in ovarian carcinoma: a report of nine cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:682-685.

- Kim MK, Kim SH, Lee YY, et al. Metastatic skin lesions on lower extremities in a patient with recurrent serous papillary ovarian carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:142-145.

- Karmali S, Rudmik L, Temple W, et al. Melanoma erysipeloides. Can J Surg. 2005;48:159-160.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides of the breast in a patient with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:575-576.

- Hazelrigg DE, Rudolph AH. Inflammatory metastic carcinoma. carcinoma erysipelatoides. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:69-70.

- Cowan LJ, Roller JI, Connelly PJ, et al. Extraovarian stage IV peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma presenting as an asymptomatic skin lesion—a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57:433-435.

- Schonmann R, Altaras M, Biron T, et al. Inflammatory skin metastases from ovarian carcinoma—a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:670-672.

- Klein RL, Brown AR, Gomez-Castro CM, et al. Ovarian cancer metastatic to the breast presenting as inflammatory breast cancer: a case report and literature review. J Cancer. 2010;1:27-31.

- Lee HC, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian clear-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5828-5830.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Photo quiz. rash in a patient with ovarian cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:538, 575-576.

Practice Points

- Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous marker of metastatic ovarian cancer.

- Clinicians should be aware of carcinoma erysipeloides in ovarian cancer and maintain a low threshold for biopsy for accurate diagnosis and management planning.

Metastatic Melanoma and Prostatic Adenocarcinoma in the Same Sentinel Lymph Node

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

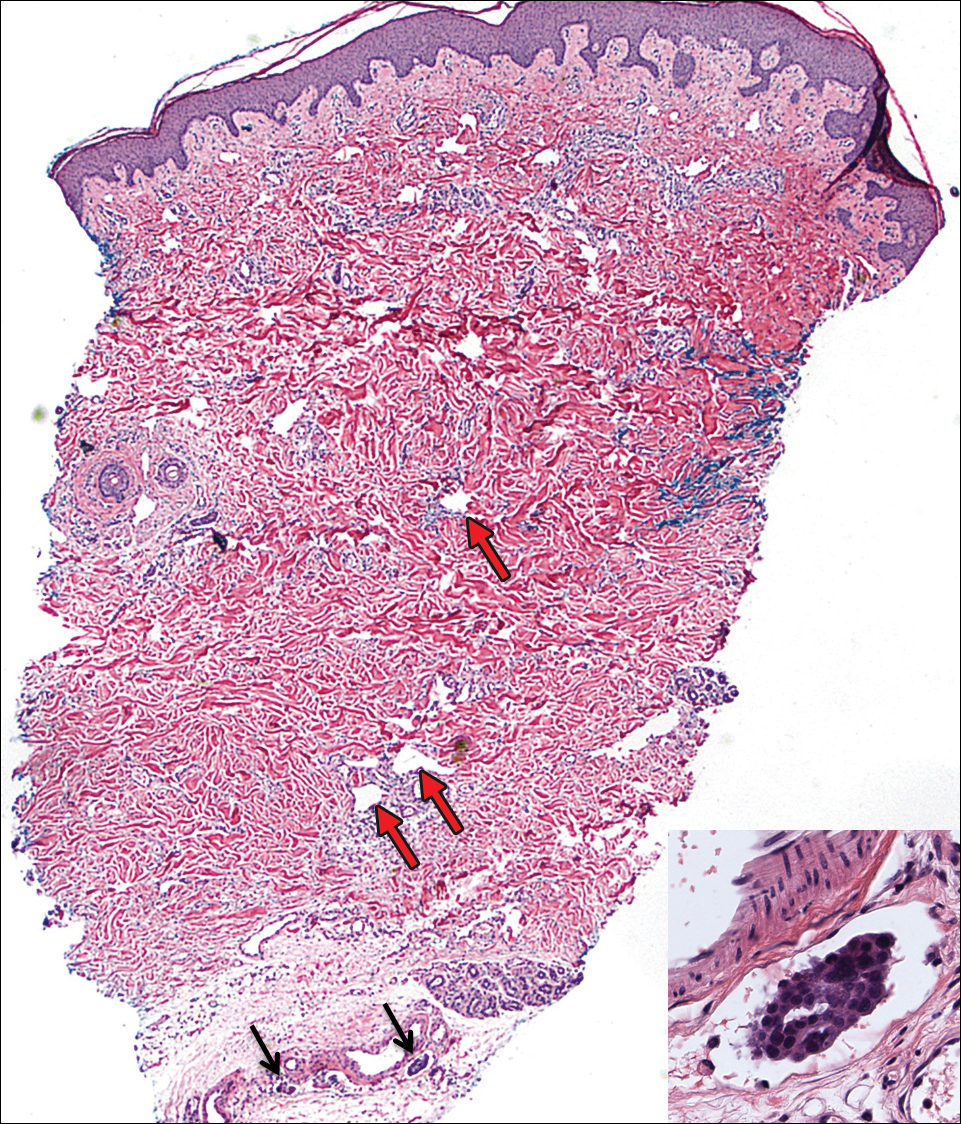

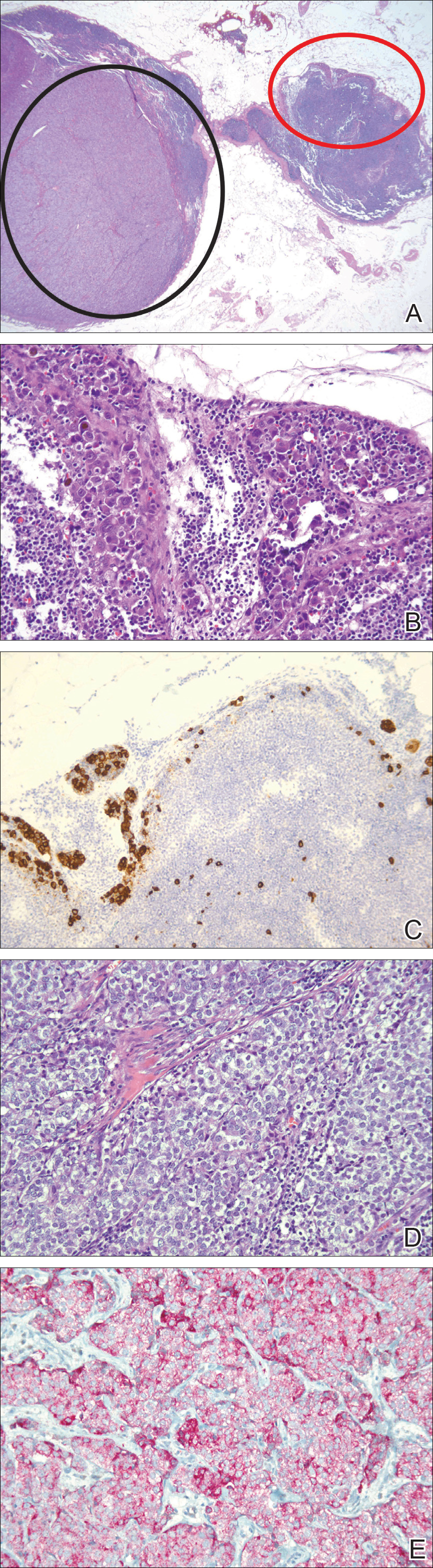

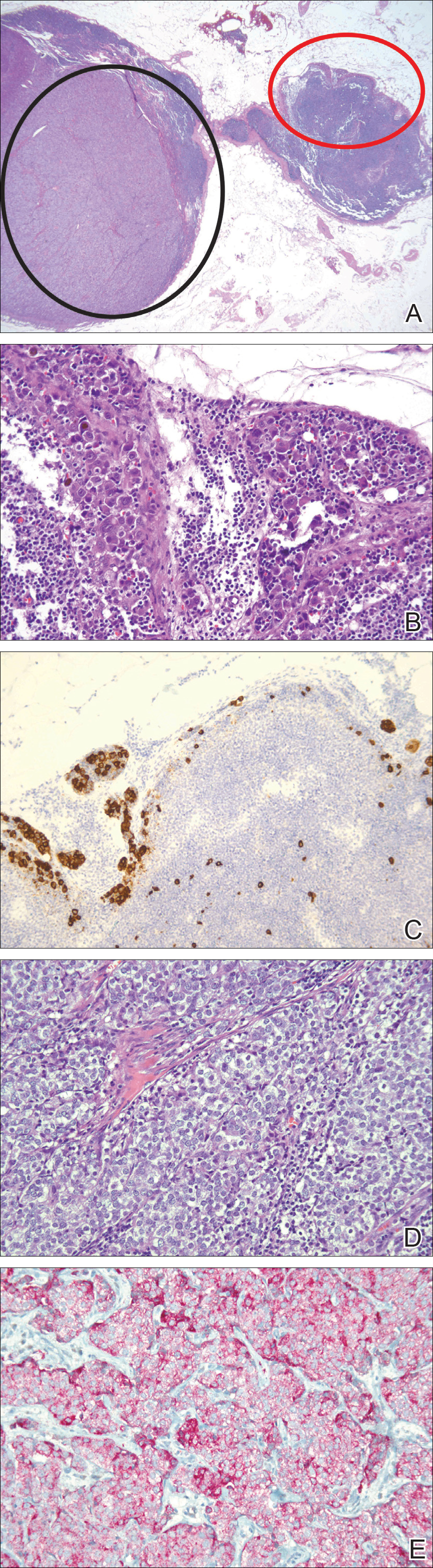

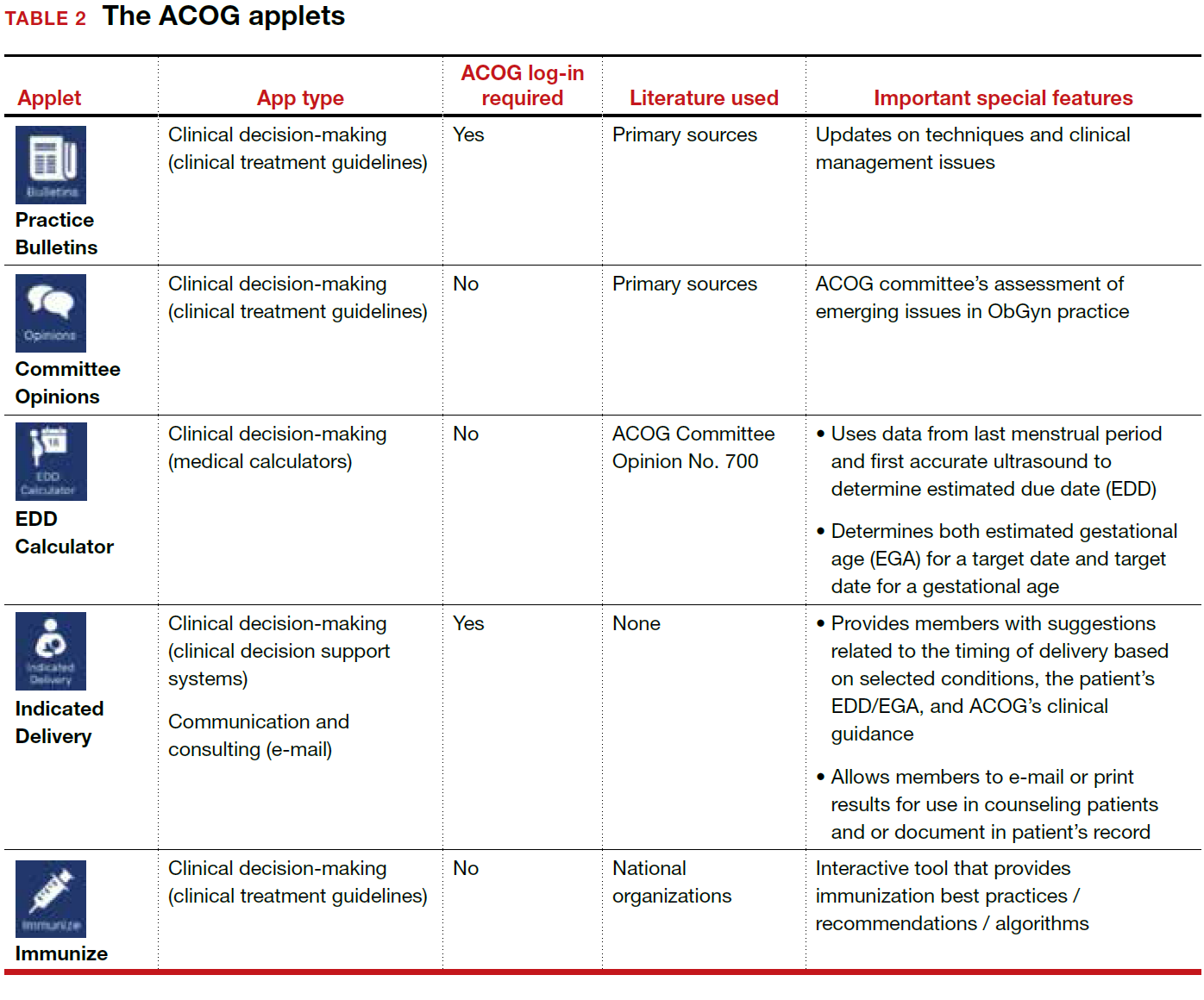

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

Practice Points

- Immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic sources of metastases.

- Thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease.

Updates on health and care utilization by TGNC youth

As we providers begin to gain a better understanding of the complexities of gender identity and expression, studies examining the health of transgender and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) youth are emerging. Multiple studies have demonstrated the mental health disparities that TGNC youth face, but more studies examining other health risks and disparities are needed.

Prevalence of TGNC students higher than expected

Previous studies looking at prevalence rates of TGNC youth often dichotomized gender identities into binary (masculine or feminine) groups and were not inclusive of nonbinary and questioning identities. This may have led to underestimation of the size of this population.2,3 This study assessed for TGNC identities by asking, “Do you consider yourself transgender, genderqueer, gender fluid, or unsure about your gender identity?” Given the prevalence of TGNC identities in this sample, it is likely that TGNC youth will be encountered in general pediatric practice. As such, it is important that we as providers continue to build our competency in working with this population.

Statistically significant differences in health status were identified

Almost two-thirds (62%) of TGNC youth identified their health as poor, fair, or good as opposed to very good or excellent, compared with one-third (33.1%) of cisgender youth. Over half (52%) of TGNC youth reported staying home from school because of illness at least once in the past month, compared with 43% of cisgender youth. About 60% of TGNC youth reported a preventive medical check-up in the past year, compared with 65% of cisgender youth. In terms of long-term health problems, TGNC youth reported higher rates of long-term physical (25% vs. 15%) and mental health (59% vs. 17%) problems than did their cisgender peers.

Role of perceived gender expression

A unique aspect of this study was that it sought to examine the effect of perceived gender expression (the way others interpret a person’s gender presentation; their appearance, style, dress, or the way they walk or talk) on health status and care utilization. Categories of perceived gender expression included very or mostly feminine, somewhat feminine, equally feminine and masculine, somewhat masculine, or very or mostly masculine. The prevalence of TGNC adolescents with an equally feminine and masculine gender expression was highest for both those assigned male (29%) and assigned female (41%) at birth, compared with other perceived gender presentations.

TGNC youth who were perceived to have a gender expression that was incongruent with the sex assigned at birth were at higher risk of reporting poor health status. For example, in TGNC participants who were assigned male at birth, those perceived as equally feminine and masculine (49%) or somewhat masculine (58%) were significantly more likely to report having poorer general health than those with a very masculine perceived gender expression (32%).

Suggestions for providers

The authors of the study and the accompanying commentary by Daniel Shumer, MD, MPH, suggest that there are things we as health care providers can do to address these barriers.

- Recognize that health disparities exist in this population. Individuals perceived as gender nonconforming may be vulnerable to discrimination and have difficulty accessing and receiving heath care, compared with their cisgender peers.

- Screen for health risks and identify barriers to care for TGNC youth while promoting and bolstering wellness within this community.

- Continue to promote access to gender affirming care. Data suggest that children who receive gender affirming care achieve mental health status similar to that of their cisgender peers.3,4,5

- Continue to develop an understanding of how youth understand and express gender.

- Nonbinary youth face unique barriers when accessing health affirming services because of fears that their gender identity may be misunderstood. These barriers lead to delays in seeking health care services, which may lead to poorer outcomes. As providers, educating ourselves about these diverse identities and being respectful of all patients’ identities can help reduce these barriers.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2018 Feb 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1683.

2. J Adolesc Health. 2017 Oct;61(4):521-6.

3. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4079.

4. Pediatrics. 2014 Oct;134(4):696-704.

5. Pediatrics. 2016 Mar;137(3):e20153223.