User login

Which antibiotics should be used with caution in pregnant women with UTI?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Lower urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy. Approximately 5% to 10% of all pregnant women have asymptomatic bacteriuria, which usually antedates the pregnancy and is detected at the time of the first prenatal appointment. Another 2% to 3% develop acute cystitis during pregnancy. The dominant organisms that cause lower UTIs in pregnant women are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus species, group B streptococci, enterococci, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus.

One goal of treating asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis is to prevent ascending infection (pyelonephritis), which can be associated with preterm delivery, sepsis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Another key goal is to use an antibiotic that eradicates the uropathogen without causing harm to either the mother or fetus.

In 2009, Crider and colleagues reported that 2 of the most commonly used antibiotics for UTIs, sulfonamides and nitrofurantoin, were associated with a disturbing spectrum of birth defects.1 Following that report, in 2011 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion that recommended against the use of these 2 agents in the first trimester of pregnancy unless other antibiotics were unlikely to be effective.2

Details of the study

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention investigators recently conducted a study to assess the effect of these ACOG recommendations on clinical practice. Ailes and co-workers used the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Database to examine antibiotic prescriptions filled by pregnant women with UTIs.

The database included 482,917 pregnancies in 2014 eligible for analysis. A total of 7.2% (n = 34,864) of pregnant women were treated as outpatients for a UTI within the 90-day interval before the last menstrual period or during the pregnancy. Among these women, the most commonly prescribed antibiotics during the first trimester were nitrofurantoin (34.7%), ciprofloxacin (10.5%), cephalexin (10.3%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (7.6%).

The authors concluded that 43% of women used an antibiotic (nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) in the first trimester that had potential teratogenicity, despite the precautionary statement articulated in the ACOG committee opinion.2

Antibiotic-associated effects

Of all the antibiotics that could be used to treat a lower UTI in pregnancy, nitrofurantoin probably has the greatest appeal. The drug is highly concentrated in the urine and is very active against all the common uropathogens except Proteus species. It is not absorbed significantly outside the lower urinary tract, and thus it does not alter the natural flora of the bowel or vagina (such alteration would predispose the patient to antibiotic-associated diarrhea or vulvovaginal candidiasis). Nitrofurantoin is inexpensive and usually is very well tolerated.

In the National Birth Defects Prevention Study by Crider and colleagues, nitrofurantoin was associated with anophthalmia or microphthalmos (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 3.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–12.2), hypoplastic left heart syndrome (AOR, 4.2; 95% CI, 1.9–9.1), atrial septal defects (AOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1–3.4), and cleft lip with cleft palate (AOR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.9).1 Other investigations, including one published as recently as 2013, have not documented these same associations.3

Similarly, the combination of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole also has considerable appeal for treating lower UTIs in pregnancy because it is highly active against most uropathogens, is inexpensive, and usually is very well tolerated. The report by Crider and colleagues, however, was even more worrisome with respect to the possible teratogenicity of this antibiotic.1 The authors found that use of this antibiotic in the first trimester was associated with anencephaly (AOR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.3–8.8), coarctation of the aorta (AOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.6), hypoplastic left heart (AOR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.3–7.6), choanal atresia (AOR, 8.0; 95% CI, 2.7–23.5), transverse limb deficiency (AOR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.0–5.9), and diaphragmatic hernia (AOR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.1–5.4). Again, other authors, using different epidemiologic methods, have not found the same associations.3

Study strengths and weaknesses

The National Birth Defects Prevention Study by Crider and colleagues was a large, well-funded, and well-designed epidemiologic study. It included more than 13,000 patients from 10 different states.

Nevertheless, the study had certain limitations.4 The findings are subject to recall bias because the investigators questioned patients about antibiotic use after, rather than during, pregnancy. Understandably, the investigators were not able to verify the prescriptions for antibiotics by reviewing each individual medical record. In fact, one-third of study participants were unable to recall the exact name of the antibiotic they received. The authors did not precisely distinguish between single-agent sulfonamides and the combination drug, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, although it seems reasonable to assume that the majority of the prescriptions were for the latter. Finally, given the observational nature of the study, the authors could not be certain that the observed associations were due to the antibiotic, the infection for which the drug was prescribed, or another confounding factor.

Pending the publication of additional investigations, I believe that the guidance outlined below is prudent.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should not be used for treating UTIs in the first trimester of pregnancy unless no other antibiotic is likely to be effective. This drug also should be avoided just prior to expected delivery because it can displace bilirubin from protein-binding sites in the newborn and increase the risk of neonatal jaundice.

There may be instances in which trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be used even early in pregnancy, such as to provide prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci infection in women with human immunodeficiency virus.

To exercise an abundance of caution, I recommend that nitrofurantoin not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy unless no other antibiotic is likely to be effective.

Alternative antibiotics that might be used in the first trimester for treatment of UTIs include ampicillin, amoxicillin, cephalexin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Substantial evidence supports the safety of these antibiotics in early pregnancy. Unless no other drug is likely to be effective, I would not recommend use of a quinolone antibiotic, such as ciprofloxacin, because of concern about the possible injurious effect of these agents on cartilaginous tissue in the developing fetus.

Neither trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole nor nitrofurantoin should be used at any time in pregnancy in a patient who has glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency or who may be at increased risk for this disorder.2

-- Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, Berry RJ, Hobbs CA, Hu DJ. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects: National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(11):978–985.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 494: Sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1484–1485.

- Nordeng H, Lupattelli A, Romoren M, Koren G. Neonatal outcomes after gestational exposure to nitrofurantoin. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):306–313.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 717: Sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):e150–e152. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002300.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Lower urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy. Approximately 5% to 10% of all pregnant women have asymptomatic bacteriuria, which usually antedates the pregnancy and is detected at the time of the first prenatal appointment. Another 2% to 3% develop acute cystitis during pregnancy. The dominant organisms that cause lower UTIs in pregnant women are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus species, group B streptococci, enterococci, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus.

One goal of treating asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis is to prevent ascending infection (pyelonephritis), which can be associated with preterm delivery, sepsis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Another key goal is to use an antibiotic that eradicates the uropathogen without causing harm to either the mother or fetus.

In 2009, Crider and colleagues reported that 2 of the most commonly used antibiotics for UTIs, sulfonamides and nitrofurantoin, were associated with a disturbing spectrum of birth defects.1 Following that report, in 2011 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion that recommended against the use of these 2 agents in the first trimester of pregnancy unless other antibiotics were unlikely to be effective.2

Details of the study

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention investigators recently conducted a study to assess the effect of these ACOG recommendations on clinical practice. Ailes and co-workers used the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Database to examine antibiotic prescriptions filled by pregnant women with UTIs.

The database included 482,917 pregnancies in 2014 eligible for analysis. A total of 7.2% (n = 34,864) of pregnant women were treated as outpatients for a UTI within the 90-day interval before the last menstrual period or during the pregnancy. Among these women, the most commonly prescribed antibiotics during the first trimester were nitrofurantoin (34.7%), ciprofloxacin (10.5%), cephalexin (10.3%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (7.6%).

The authors concluded that 43% of women used an antibiotic (nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) in the first trimester that had potential teratogenicity, despite the precautionary statement articulated in the ACOG committee opinion.2

Antibiotic-associated effects

Of all the antibiotics that could be used to treat a lower UTI in pregnancy, nitrofurantoin probably has the greatest appeal. The drug is highly concentrated in the urine and is very active against all the common uropathogens except Proteus species. It is not absorbed significantly outside the lower urinary tract, and thus it does not alter the natural flora of the bowel or vagina (such alteration would predispose the patient to antibiotic-associated diarrhea or vulvovaginal candidiasis). Nitrofurantoin is inexpensive and usually is very well tolerated.

In the National Birth Defects Prevention Study by Crider and colleagues, nitrofurantoin was associated with anophthalmia or microphthalmos (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 3.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–12.2), hypoplastic left heart syndrome (AOR, 4.2; 95% CI, 1.9–9.1), atrial septal defects (AOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1–3.4), and cleft lip with cleft palate (AOR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.9).1 Other investigations, including one published as recently as 2013, have not documented these same associations.3

Similarly, the combination of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole also has considerable appeal for treating lower UTIs in pregnancy because it is highly active against most uropathogens, is inexpensive, and usually is very well tolerated. The report by Crider and colleagues, however, was even more worrisome with respect to the possible teratogenicity of this antibiotic.1 The authors found that use of this antibiotic in the first trimester was associated with anencephaly (AOR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.3–8.8), coarctation of the aorta (AOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.6), hypoplastic left heart (AOR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.3–7.6), choanal atresia (AOR, 8.0; 95% CI, 2.7–23.5), transverse limb deficiency (AOR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.0–5.9), and diaphragmatic hernia (AOR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.1–5.4). Again, other authors, using different epidemiologic methods, have not found the same associations.3

Study strengths and weaknesses

The National Birth Defects Prevention Study by Crider and colleagues was a large, well-funded, and well-designed epidemiologic study. It included more than 13,000 patients from 10 different states.

Nevertheless, the study had certain limitations.4 The findings are subject to recall bias because the investigators questioned patients about antibiotic use after, rather than during, pregnancy. Understandably, the investigators were not able to verify the prescriptions for antibiotics by reviewing each individual medical record. In fact, one-third of study participants were unable to recall the exact name of the antibiotic they received. The authors did not precisely distinguish between single-agent sulfonamides and the combination drug, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, although it seems reasonable to assume that the majority of the prescriptions were for the latter. Finally, given the observational nature of the study, the authors could not be certain that the observed associations were due to the antibiotic, the infection for which the drug was prescribed, or another confounding factor.

Pending the publication of additional investigations, I believe that the guidance outlined below is prudent.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should not be used for treating UTIs in the first trimester of pregnancy unless no other antibiotic is likely to be effective. This drug also should be avoided just prior to expected delivery because it can displace bilirubin from protein-binding sites in the newborn and increase the risk of neonatal jaundice.

There may be instances in which trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be used even early in pregnancy, such as to provide prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci infection in women with human immunodeficiency virus.

To exercise an abundance of caution, I recommend that nitrofurantoin not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy unless no other antibiotic is likely to be effective.

Alternative antibiotics that might be used in the first trimester for treatment of UTIs include ampicillin, amoxicillin, cephalexin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Substantial evidence supports the safety of these antibiotics in early pregnancy. Unless no other drug is likely to be effective, I would not recommend use of a quinolone antibiotic, such as ciprofloxacin, because of concern about the possible injurious effect of these agents on cartilaginous tissue in the developing fetus.

Neither trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole nor nitrofurantoin should be used at any time in pregnancy in a patient who has glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency or who may be at increased risk for this disorder.2

-- Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Lower urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy. Approximately 5% to 10% of all pregnant women have asymptomatic bacteriuria, which usually antedates the pregnancy and is detected at the time of the first prenatal appointment. Another 2% to 3% develop acute cystitis during pregnancy. The dominant organisms that cause lower UTIs in pregnant women are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus species, group B streptococci, enterococci, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus.

One goal of treating asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis is to prevent ascending infection (pyelonephritis), which can be associated with preterm delivery, sepsis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Another key goal is to use an antibiotic that eradicates the uropathogen without causing harm to either the mother or fetus.

In 2009, Crider and colleagues reported that 2 of the most commonly used antibiotics for UTIs, sulfonamides and nitrofurantoin, were associated with a disturbing spectrum of birth defects.1 Following that report, in 2011 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion that recommended against the use of these 2 agents in the first trimester of pregnancy unless other antibiotics were unlikely to be effective.2

Details of the study

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention investigators recently conducted a study to assess the effect of these ACOG recommendations on clinical practice. Ailes and co-workers used the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Database to examine antibiotic prescriptions filled by pregnant women with UTIs.

The database included 482,917 pregnancies in 2014 eligible for analysis. A total of 7.2% (n = 34,864) of pregnant women were treated as outpatients for a UTI within the 90-day interval before the last menstrual period or during the pregnancy. Among these women, the most commonly prescribed antibiotics during the first trimester were nitrofurantoin (34.7%), ciprofloxacin (10.5%), cephalexin (10.3%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (7.6%).

The authors concluded that 43% of women used an antibiotic (nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) in the first trimester that had potential teratogenicity, despite the precautionary statement articulated in the ACOG committee opinion.2

Antibiotic-associated effects

Of all the antibiotics that could be used to treat a lower UTI in pregnancy, nitrofurantoin probably has the greatest appeal. The drug is highly concentrated in the urine and is very active against all the common uropathogens except Proteus species. It is not absorbed significantly outside the lower urinary tract, and thus it does not alter the natural flora of the bowel or vagina (such alteration would predispose the patient to antibiotic-associated diarrhea or vulvovaginal candidiasis). Nitrofurantoin is inexpensive and usually is very well tolerated.

In the National Birth Defects Prevention Study by Crider and colleagues, nitrofurantoin was associated with anophthalmia or microphthalmos (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 3.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–12.2), hypoplastic left heart syndrome (AOR, 4.2; 95% CI, 1.9–9.1), atrial septal defects (AOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1–3.4), and cleft lip with cleft palate (AOR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.9).1 Other investigations, including one published as recently as 2013, have not documented these same associations.3

Similarly, the combination of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole also has considerable appeal for treating lower UTIs in pregnancy because it is highly active against most uropathogens, is inexpensive, and usually is very well tolerated. The report by Crider and colleagues, however, was even more worrisome with respect to the possible teratogenicity of this antibiotic.1 The authors found that use of this antibiotic in the first trimester was associated with anencephaly (AOR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.3–8.8), coarctation of the aorta (AOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.6), hypoplastic left heart (AOR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.3–7.6), choanal atresia (AOR, 8.0; 95% CI, 2.7–23.5), transverse limb deficiency (AOR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.0–5.9), and diaphragmatic hernia (AOR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.1–5.4). Again, other authors, using different epidemiologic methods, have not found the same associations.3

Study strengths and weaknesses

The National Birth Defects Prevention Study by Crider and colleagues was a large, well-funded, and well-designed epidemiologic study. It included more than 13,000 patients from 10 different states.

Nevertheless, the study had certain limitations.4 The findings are subject to recall bias because the investigators questioned patients about antibiotic use after, rather than during, pregnancy. Understandably, the investigators were not able to verify the prescriptions for antibiotics by reviewing each individual medical record. In fact, one-third of study participants were unable to recall the exact name of the antibiotic they received. The authors did not precisely distinguish between single-agent sulfonamides and the combination drug, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, although it seems reasonable to assume that the majority of the prescriptions were for the latter. Finally, given the observational nature of the study, the authors could not be certain that the observed associations were due to the antibiotic, the infection for which the drug was prescribed, or another confounding factor.

Pending the publication of additional investigations, I believe that the guidance outlined below is prudent.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should not be used for treating UTIs in the first trimester of pregnancy unless no other antibiotic is likely to be effective. This drug also should be avoided just prior to expected delivery because it can displace bilirubin from protein-binding sites in the newborn and increase the risk of neonatal jaundice.

There may be instances in which trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be used even early in pregnancy, such as to provide prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci infection in women with human immunodeficiency virus.

To exercise an abundance of caution, I recommend that nitrofurantoin not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy unless no other antibiotic is likely to be effective.

Alternative antibiotics that might be used in the first trimester for treatment of UTIs include ampicillin, amoxicillin, cephalexin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Substantial evidence supports the safety of these antibiotics in early pregnancy. Unless no other drug is likely to be effective, I would not recommend use of a quinolone antibiotic, such as ciprofloxacin, because of concern about the possible injurious effect of these agents on cartilaginous tissue in the developing fetus.

Neither trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole nor nitrofurantoin should be used at any time in pregnancy in a patient who has glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency or who may be at increased risk for this disorder.2

-- Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, Berry RJ, Hobbs CA, Hu DJ. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects: National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(11):978–985.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 494: Sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1484–1485.

- Nordeng H, Lupattelli A, Romoren M, Koren G. Neonatal outcomes after gestational exposure to nitrofurantoin. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):306–313.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 717: Sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):e150–e152. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002300.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, Berry RJ, Hobbs CA, Hu DJ. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects: National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(11):978–985.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 494: Sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1484–1485.

- Nordeng H, Lupattelli A, Romoren M, Koren G. Neonatal outcomes after gestational exposure to nitrofurantoin. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):306–313.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 717: Sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):e150–e152. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002300.

MDedge Daily News: How real is triptans’ serotonin syndrome risk?

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

How real is triptans’ serotonin syndrome risk? Are free testosterone and frailty linked? Breast cancer mortality trends keep moving, and what pioglitazone may offer NASH patients.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

How real is triptans’ serotonin syndrome risk? Are free testosterone and frailty linked? Breast cancer mortality trends keep moving, and what pioglitazone may offer NASH patients.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

How real is triptans’ serotonin syndrome risk? Are free testosterone and frailty linked? Breast cancer mortality trends keep moving, and what pioglitazone may offer NASH patients.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Healthy Food May Come at Higher Price for Native Americans

Healthy foods may be available in grocery stores in rural American Indian communities, but the price can be high. Researchers from University of Washington looked at the availability and cost of 68 food items that comprise the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S), which evaluates whether food items adhere to the USDA Thrifty Food Plan (TFP). The TFP “market basket” represents the minimal cost of a healthy diet for a family of 4 for 1 week. The study included 27 stores within a 90-mile radius of the town center of a large American Indian reservation: 13 convenience stores, 10 grocery stores, 3 discount/dollar stores, and 1 discount supermarket. Of the surveyed stores, 10 were on the reservation, including 4 grocery stores.

All NEMS-S foods were available at the discount supermarket, and about 97% of the foods were available at the grocery stores. Convenience and discount/dollar stores were less likely to carry the foods.

The cost of a TFP market basket ranged from 3% lower to 24% higher than the national average. It also varied among the community stores: The TFP cost > 15% at the discount supermarket than at grocery stores ($152.91 vs $179.52). However, the researchers note that the cost of foods that made up the TFP market basket varied across food groups. For instance, the mean cost of dairy products was 43% lower at the discount supermarket than at the grocery stores, while fresh fruits and vegetables were 6% higher.

Healthy foods may be available in grocery stores in rural American Indian communities, but the price can be high. Researchers from University of Washington looked at the availability and cost of 68 food items that comprise the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S), which evaluates whether food items adhere to the USDA Thrifty Food Plan (TFP). The TFP “market basket” represents the minimal cost of a healthy diet for a family of 4 for 1 week. The study included 27 stores within a 90-mile radius of the town center of a large American Indian reservation: 13 convenience stores, 10 grocery stores, 3 discount/dollar stores, and 1 discount supermarket. Of the surveyed stores, 10 were on the reservation, including 4 grocery stores.

All NEMS-S foods were available at the discount supermarket, and about 97% of the foods were available at the grocery stores. Convenience and discount/dollar stores were less likely to carry the foods.

The cost of a TFP market basket ranged from 3% lower to 24% higher than the national average. It also varied among the community stores: The TFP cost > 15% at the discount supermarket than at grocery stores ($152.91 vs $179.52). However, the researchers note that the cost of foods that made up the TFP market basket varied across food groups. For instance, the mean cost of dairy products was 43% lower at the discount supermarket than at the grocery stores, while fresh fruits and vegetables were 6% higher.

Healthy foods may be available in grocery stores in rural American Indian communities, but the price can be high. Researchers from University of Washington looked at the availability and cost of 68 food items that comprise the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S), which evaluates whether food items adhere to the USDA Thrifty Food Plan (TFP). The TFP “market basket” represents the minimal cost of a healthy diet for a family of 4 for 1 week. The study included 27 stores within a 90-mile radius of the town center of a large American Indian reservation: 13 convenience stores, 10 grocery stores, 3 discount/dollar stores, and 1 discount supermarket. Of the surveyed stores, 10 were on the reservation, including 4 grocery stores.

All NEMS-S foods were available at the discount supermarket, and about 97% of the foods were available at the grocery stores. Convenience and discount/dollar stores were less likely to carry the foods.

The cost of a TFP market basket ranged from 3% lower to 24% higher than the national average. It also varied among the community stores: The TFP cost > 15% at the discount supermarket than at grocery stores ($152.91 vs $179.52). However, the researchers note that the cost of foods that made up the TFP market basket varied across food groups. For instance, the mean cost of dairy products was 43% lower at the discount supermarket than at the grocery stores, while fresh fruits and vegetables were 6% higher.

Team identifies biomarkers for cGVHD in kids

SALT LAKE CITY—Researchers say they have identified prognostic biomarkers for chronic graft-vs-host disease (cGVHD) in children.

The group found that recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) and regulatory T cells expressing CD31 and CD45RA (Treg RTEs) were significantly lower at day 100 after transplant in patients who developed cGVHD.

Because prior research indicated that RTEs are higher in adults with cGVHD, the researchers concluded that thymic function may play a bigger role in cGVHD development for children than for adults.

Geoff D.E. Cuvelier, MD, of CancerCare Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada, presented these findings at the 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 104).

“Our group became interested in these populations of recent thymic emigrants when 2 adult studies1,2 . . . showed that higher proportions of recent thymic emigrants at day 100 were prognostic for the development of chronic graft-vs-host disease,” Dr Cuvelier said.

This led his group to evaluate whether RTEs (CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ T cells), as well as Treg RTEs—Tregs (CD4+CD25+CD127Low) that co-express naïve and recently emigrated markers (CD45RA+CD31+)—are prognostic for pediatric cGVHD at day 100 after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT).

The researchers’ study enrolled patients younger than 18 years of age who underwent allo-HSCT to treat malignant and non-malignant diseases. There were 144 patients who had 1 year of follow-up after allo-HSCT.

Thirty-seven of the patients (25.7%) had cGVHD, and 34 (23.6%) had late acute GVHD (post-day 100). The remaining 73 patients (50.7%) had neither cGVHD nor late acute GVHD, so they served as controls.

Twenty cases of cGVHD were severe, 12 were moderate, and 5 were mild. cGVHD was initially diagnosed at a mean of 192 days post-transplant. The median number of organ systems involved was 3 (range, 1-6). Seventeen patients (46%) had overlap syndrome.

The researchers found that RTEs as a percentage of CD4 T cells were significantly lower at day 100 in patients with cGVHD than in controls—7.8% and 13.5%, respectively (P=0.007). The difference between controls and patients with late acute GVHD was not significant—13.5% and 9.4%, respectively (P=0.08).

Treg RTEs as a percentage of all Tregs were also significantly lower at day 100 in patients with cGVHD than in controls—6.4% and 13.2%, respectively (P=0.002). Again, the difference between controls and patients with late acute GVHD was not significant—13.2% and 9.1%, respectively (P=0.06).

However, further analysis revealed that percentages of RTEs and Treg RTEs were significantly lower at day 100 in patients who developed any type of GVHD after day 100.

The percentage of RTEs was 13.5% in controls and 8.5% in patients with any GVHD after day 100 (P=0.009). The percentage of Treg RTEs was 13.2% and 7.6%, respectively (P=0.004).

“Both recent thymic emigrants and Treg RTEs at day 100 are prognostic biomarkers for chronic graft-vs-host disease in children in this large, multi-institutional, prospective trial,” Dr Cuvelier said in closing.

“Unlike adults, in children, RTEs are proportionally lower, not higher, in patients that later develop chronic GVHD compared to no chronic GVHD. This may suggest that thymic dysfunction and thymic output may play a greater role in chronic GVHD development in children compared to adults.”

To expand upon this research, Dr Cuvelier and his colleagues are planning to begin model building using prognostic cellular and plasma biomarkers at day 100 to determine high-risk profiles for cGVHD.

1. Greinix HT et al; CD19+CD21low B Cells and CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ T Cells Correlate with First Diagnosis of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. BBMT 2015; 21(2):250-258.

2. Li AM et al. An Early Naïve T Cell Population Lacking PD1 Expression at Day 100 As A Prognostic Biomarker of Chronic GVHD. TSS 2017; 210.6.

SALT LAKE CITY—Researchers say they have identified prognostic biomarkers for chronic graft-vs-host disease (cGVHD) in children.

The group found that recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) and regulatory T cells expressing CD31 and CD45RA (Treg RTEs) were significantly lower at day 100 after transplant in patients who developed cGVHD.

Because prior research indicated that RTEs are higher in adults with cGVHD, the researchers concluded that thymic function may play a bigger role in cGVHD development for children than for adults.

Geoff D.E. Cuvelier, MD, of CancerCare Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada, presented these findings at the 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 104).

“Our group became interested in these populations of recent thymic emigrants when 2 adult studies1,2 . . . showed that higher proportions of recent thymic emigrants at day 100 were prognostic for the development of chronic graft-vs-host disease,” Dr Cuvelier said.

This led his group to evaluate whether RTEs (CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ T cells), as well as Treg RTEs—Tregs (CD4+CD25+CD127Low) that co-express naïve and recently emigrated markers (CD45RA+CD31+)—are prognostic for pediatric cGVHD at day 100 after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT).

The researchers’ study enrolled patients younger than 18 years of age who underwent allo-HSCT to treat malignant and non-malignant diseases. There were 144 patients who had 1 year of follow-up after allo-HSCT.

Thirty-seven of the patients (25.7%) had cGVHD, and 34 (23.6%) had late acute GVHD (post-day 100). The remaining 73 patients (50.7%) had neither cGVHD nor late acute GVHD, so they served as controls.

Twenty cases of cGVHD were severe, 12 were moderate, and 5 were mild. cGVHD was initially diagnosed at a mean of 192 days post-transplant. The median number of organ systems involved was 3 (range, 1-6). Seventeen patients (46%) had overlap syndrome.

The researchers found that RTEs as a percentage of CD4 T cells were significantly lower at day 100 in patients with cGVHD than in controls—7.8% and 13.5%, respectively (P=0.007). The difference between controls and patients with late acute GVHD was not significant—13.5% and 9.4%, respectively (P=0.08).

Treg RTEs as a percentage of all Tregs were also significantly lower at day 100 in patients with cGVHD than in controls—6.4% and 13.2%, respectively (P=0.002). Again, the difference between controls and patients with late acute GVHD was not significant—13.2% and 9.1%, respectively (P=0.06).

However, further analysis revealed that percentages of RTEs and Treg RTEs were significantly lower at day 100 in patients who developed any type of GVHD after day 100.

The percentage of RTEs was 13.5% in controls and 8.5% in patients with any GVHD after day 100 (P=0.009). The percentage of Treg RTEs was 13.2% and 7.6%, respectively (P=0.004).

“Both recent thymic emigrants and Treg RTEs at day 100 are prognostic biomarkers for chronic graft-vs-host disease in children in this large, multi-institutional, prospective trial,” Dr Cuvelier said in closing.

“Unlike adults, in children, RTEs are proportionally lower, not higher, in patients that later develop chronic GVHD compared to no chronic GVHD. This may suggest that thymic dysfunction and thymic output may play a greater role in chronic GVHD development in children compared to adults.”

To expand upon this research, Dr Cuvelier and his colleagues are planning to begin model building using prognostic cellular and plasma biomarkers at day 100 to determine high-risk profiles for cGVHD.

1. Greinix HT et al; CD19+CD21low B Cells and CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ T Cells Correlate with First Diagnosis of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. BBMT 2015; 21(2):250-258.

2. Li AM et al. An Early Naïve T Cell Population Lacking PD1 Expression at Day 100 As A Prognostic Biomarker of Chronic GVHD. TSS 2017; 210.6.

SALT LAKE CITY—Researchers say they have identified prognostic biomarkers for chronic graft-vs-host disease (cGVHD) in children.

The group found that recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) and regulatory T cells expressing CD31 and CD45RA (Treg RTEs) were significantly lower at day 100 after transplant in patients who developed cGVHD.

Because prior research indicated that RTEs are higher in adults with cGVHD, the researchers concluded that thymic function may play a bigger role in cGVHD development for children than for adults.

Geoff D.E. Cuvelier, MD, of CancerCare Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada, presented these findings at the 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 104).

“Our group became interested in these populations of recent thymic emigrants when 2 adult studies1,2 . . . showed that higher proportions of recent thymic emigrants at day 100 were prognostic for the development of chronic graft-vs-host disease,” Dr Cuvelier said.

This led his group to evaluate whether RTEs (CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ T cells), as well as Treg RTEs—Tregs (CD4+CD25+CD127Low) that co-express naïve and recently emigrated markers (CD45RA+CD31+)—are prognostic for pediatric cGVHD at day 100 after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT).

The researchers’ study enrolled patients younger than 18 years of age who underwent allo-HSCT to treat malignant and non-malignant diseases. There were 144 patients who had 1 year of follow-up after allo-HSCT.

Thirty-seven of the patients (25.7%) had cGVHD, and 34 (23.6%) had late acute GVHD (post-day 100). The remaining 73 patients (50.7%) had neither cGVHD nor late acute GVHD, so they served as controls.

Twenty cases of cGVHD were severe, 12 were moderate, and 5 were mild. cGVHD was initially diagnosed at a mean of 192 days post-transplant. The median number of organ systems involved was 3 (range, 1-6). Seventeen patients (46%) had overlap syndrome.

The researchers found that RTEs as a percentage of CD4 T cells were significantly lower at day 100 in patients with cGVHD than in controls—7.8% and 13.5%, respectively (P=0.007). The difference between controls and patients with late acute GVHD was not significant—13.5% and 9.4%, respectively (P=0.08).

Treg RTEs as a percentage of all Tregs were also significantly lower at day 100 in patients with cGVHD than in controls—6.4% and 13.2%, respectively (P=0.002). Again, the difference between controls and patients with late acute GVHD was not significant—13.2% and 9.1%, respectively (P=0.06).

However, further analysis revealed that percentages of RTEs and Treg RTEs were significantly lower at day 100 in patients who developed any type of GVHD after day 100.

The percentage of RTEs was 13.5% in controls and 8.5% in patients with any GVHD after day 100 (P=0.009). The percentage of Treg RTEs was 13.2% and 7.6%, respectively (P=0.004).

“Both recent thymic emigrants and Treg RTEs at day 100 are prognostic biomarkers for chronic graft-vs-host disease in children in this large, multi-institutional, prospective trial,” Dr Cuvelier said in closing.

“Unlike adults, in children, RTEs are proportionally lower, not higher, in patients that later develop chronic GVHD compared to no chronic GVHD. This may suggest that thymic dysfunction and thymic output may play a greater role in chronic GVHD development in children compared to adults.”

To expand upon this research, Dr Cuvelier and his colleagues are planning to begin model building using prognostic cellular and plasma biomarkers at day 100 to determine high-risk profiles for cGVHD.

1. Greinix HT et al; CD19+CD21low B Cells and CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ T Cells Correlate with First Diagnosis of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. BBMT 2015; 21(2):250-258.

2. Li AM et al. An Early Naïve T Cell Population Lacking PD1 Expression at Day 100 As A Prognostic Biomarker of Chronic GVHD. TSS 2017; 210.6.

CHMP backs bosutinib for newly diagnosed CML

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the approved use of bosutinib (BOSULIF) to include treatment of patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

Bosutinib is currently approved in Europe to treat patients with Ph+ CML in chronic, accelerated, or blast phase who have received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and for whom imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are not considered appropriate treatment options.

The CHMP’s opinion on bosutinib will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC). If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the commission will grant a centralized marketing authorization that will be valid in the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The CHMP’s recommendation for bosutinib is based on results from the BFORE trial, which were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The publication included data on 536 patients newly diagnosed with chronic phase CML. They were randomized 1:1 to receive bosutinib (n=268) or imatinib (n=268).

The modified intent-to-treat population included Ph+ patients with e13a2/e14a2 transcripts who had at least 12 months of follow-up. In this group, there were 246 patients in the bosutinib arm and 241 in the imatinib arm.

In the modified intent-to-treat population, the rate of major molecular response at 12 months was 47.2% in the bosutinib arm and 36.9% in the imatinib arm (P=0.02). The rate of complete cytogenetic response was 77.2% and 66.4%, respectively (P<0.008).

In the entire study population, 22.0% of patients receiving bosutinib and 26.8% of those receiving imatinib discontinued treatment—12.7% and 8.7%, respectively, due to drug-related toxicity.

Adverse events that were more common in the bosutinib arm than the imatinib arm included grade 3 or higher diarrhea (7.8% vs 0.8%), increased alanine levels (19% vs 1.5%), increased aspartate levels (9.7% vs 1.9%), cardiovascular events (3% vs 0.4%), and peripheral vascular events (1.5% vs 1.1%).

Cerebrovascular events were more common with imatinib than bosutinib (0.4% and 0%, respectively).

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the approved use of bosutinib (BOSULIF) to include treatment of patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

Bosutinib is currently approved in Europe to treat patients with Ph+ CML in chronic, accelerated, or blast phase who have received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and for whom imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are not considered appropriate treatment options.

The CHMP’s opinion on bosutinib will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC). If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the commission will grant a centralized marketing authorization that will be valid in the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The CHMP’s recommendation for bosutinib is based on results from the BFORE trial, which were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The publication included data on 536 patients newly diagnosed with chronic phase CML. They were randomized 1:1 to receive bosutinib (n=268) or imatinib (n=268).

The modified intent-to-treat population included Ph+ patients with e13a2/e14a2 transcripts who had at least 12 months of follow-up. In this group, there were 246 patients in the bosutinib arm and 241 in the imatinib arm.

In the modified intent-to-treat population, the rate of major molecular response at 12 months was 47.2% in the bosutinib arm and 36.9% in the imatinib arm (P=0.02). The rate of complete cytogenetic response was 77.2% and 66.4%, respectively (P<0.008).

In the entire study population, 22.0% of patients receiving bosutinib and 26.8% of those receiving imatinib discontinued treatment—12.7% and 8.7%, respectively, due to drug-related toxicity.

Adverse events that were more common in the bosutinib arm than the imatinib arm included grade 3 or higher diarrhea (7.8% vs 0.8%), increased alanine levels (19% vs 1.5%), increased aspartate levels (9.7% vs 1.9%), cardiovascular events (3% vs 0.4%), and peripheral vascular events (1.5% vs 1.1%).

Cerebrovascular events were more common with imatinib than bosutinib (0.4% and 0%, respectively).

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the approved use of bosutinib (BOSULIF) to include treatment of patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

Bosutinib is currently approved in Europe to treat patients with Ph+ CML in chronic, accelerated, or blast phase who have received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and for whom imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are not considered appropriate treatment options.

The CHMP’s opinion on bosutinib will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC). If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the commission will grant a centralized marketing authorization that will be valid in the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The CHMP’s recommendation for bosutinib is based on results from the BFORE trial, which were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The publication included data on 536 patients newly diagnosed with chronic phase CML. They were randomized 1:1 to receive bosutinib (n=268) or imatinib (n=268).

The modified intent-to-treat population included Ph+ patients with e13a2/e14a2 transcripts who had at least 12 months of follow-up. In this group, there were 246 patients in the bosutinib arm and 241 in the imatinib arm.

In the modified intent-to-treat population, the rate of major molecular response at 12 months was 47.2% in the bosutinib arm and 36.9% in the imatinib arm (P=0.02). The rate of complete cytogenetic response was 77.2% and 66.4%, respectively (P<0.008).

In the entire study population, 22.0% of patients receiving bosutinib and 26.8% of those receiving imatinib discontinued treatment—12.7% and 8.7%, respectively, due to drug-related toxicity.

Adverse events that were more common in the bosutinib arm than the imatinib arm included grade 3 or higher diarrhea (7.8% vs 0.8%), increased alanine levels (19% vs 1.5%), increased aspartate levels (9.7% vs 1.9%), cardiovascular events (3% vs 0.4%), and peripheral vascular events (1.5% vs 1.1%).

Cerebrovascular events were more common with imatinib than bosutinib (0.4% and 0%, respectively).

CHMP supports approval of denosumab in MM

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the current indication for denosumab (XGEVA®).

The CHMP said the drug should be approved for use in preventing skeletal related events (SREs) in adults with advanced malignancies involving bone, which includes multiple myeloma (MM).

Denosumab is currently approved in Europe to prevent SREs—defined as radiation to bone, pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, and spinal cord compression—in adults with bone metastases from solid tumors.

The drug is also approved for the treatment of adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumor of bone that is unresectable or where surgical resection is likely to result in severe morbidity.

The CHMP’s opinion on expanding the indication for denosumab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the commission will grant a centralized marketing authorization that will be valid in the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The CHMP’s recommendation for denosumab is based on data from the ’482 study, which were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

In this phase 3 trial, denosumab proved non-inferior to zoledronic acid for delaying SREs in patients with newly diagnosed MM and bone disease.

Researchers randomized 1718 patients to receive subcutaneous denosumab at 120 mg and intravenous placebo every 4 weeks (n=859) or intravenous zoledronic acid at 4 mg (adjusted for renal function at baseline) and subcutaneous placebo every 4 weeks (n=859). All patients also received investigators’ choice of first-line MM therapy.

The median time to first on-study SRE was 22.8 months for patients in the denosumab arm and 24 months for those in the zoledronic acid arm (hazard ratio=0.98; 95% confidence interval: 0.85-1.14; P non-inferiority=0.010).

There were fewer renal treatment-emergent adverse events in the denosumab arm than the zoledronic acid arm—10% and 17%, respectively.

But there were more hypocalcemia adverse events in the denosumab arm than the zoledronic acid arm—17% and 12%, respectively.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the current indication for denosumab (XGEVA®).

The CHMP said the drug should be approved for use in preventing skeletal related events (SREs) in adults with advanced malignancies involving bone, which includes multiple myeloma (MM).

Denosumab is currently approved in Europe to prevent SREs—defined as radiation to bone, pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, and spinal cord compression—in adults with bone metastases from solid tumors.

The drug is also approved for the treatment of adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumor of bone that is unresectable or where surgical resection is likely to result in severe morbidity.

The CHMP’s opinion on expanding the indication for denosumab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the commission will grant a centralized marketing authorization that will be valid in the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The CHMP’s recommendation for denosumab is based on data from the ’482 study, which were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

In this phase 3 trial, denosumab proved non-inferior to zoledronic acid for delaying SREs in patients with newly diagnosed MM and bone disease.

Researchers randomized 1718 patients to receive subcutaneous denosumab at 120 mg and intravenous placebo every 4 weeks (n=859) or intravenous zoledronic acid at 4 mg (adjusted for renal function at baseline) and subcutaneous placebo every 4 weeks (n=859). All patients also received investigators’ choice of first-line MM therapy.

The median time to first on-study SRE was 22.8 months for patients in the denosumab arm and 24 months for those in the zoledronic acid arm (hazard ratio=0.98; 95% confidence interval: 0.85-1.14; P non-inferiority=0.010).

There were fewer renal treatment-emergent adverse events in the denosumab arm than the zoledronic acid arm—10% and 17%, respectively.

But there were more hypocalcemia adverse events in the denosumab arm than the zoledronic acid arm—17% and 12%, respectively.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the current indication for denosumab (XGEVA®).

The CHMP said the drug should be approved for use in preventing skeletal related events (SREs) in adults with advanced malignancies involving bone, which includes multiple myeloma (MM).

Denosumab is currently approved in Europe to prevent SREs—defined as radiation to bone, pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, and spinal cord compression—in adults with bone metastases from solid tumors.

The drug is also approved for the treatment of adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumor of bone that is unresectable or where surgical resection is likely to result in severe morbidity.

The CHMP’s opinion on expanding the indication for denosumab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the commission will grant a centralized marketing authorization that will be valid in the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The CHMP’s recommendation for denosumab is based on data from the ’482 study, which were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

In this phase 3 trial, denosumab proved non-inferior to zoledronic acid for delaying SREs in patients with newly diagnosed MM and bone disease.

Researchers randomized 1718 patients to receive subcutaneous denosumab at 120 mg and intravenous placebo every 4 weeks (n=859) or intravenous zoledronic acid at 4 mg (adjusted for renal function at baseline) and subcutaneous placebo every 4 weeks (n=859). All patients also received investigators’ choice of first-line MM therapy.

The median time to first on-study SRE was 22.8 months for patients in the denosumab arm and 24 months for those in the zoledronic acid arm (hazard ratio=0.98; 95% confidence interval: 0.85-1.14; P non-inferiority=0.010).

There were fewer renal treatment-emergent adverse events in the denosumab arm than the zoledronic acid arm—10% and 17%, respectively.

But there were more hypocalcemia adverse events in the denosumab arm than the zoledronic acid arm—17% and 12%, respectively.

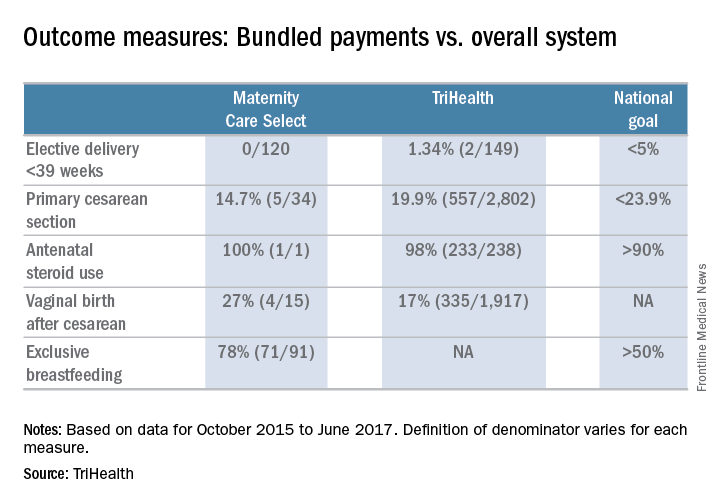

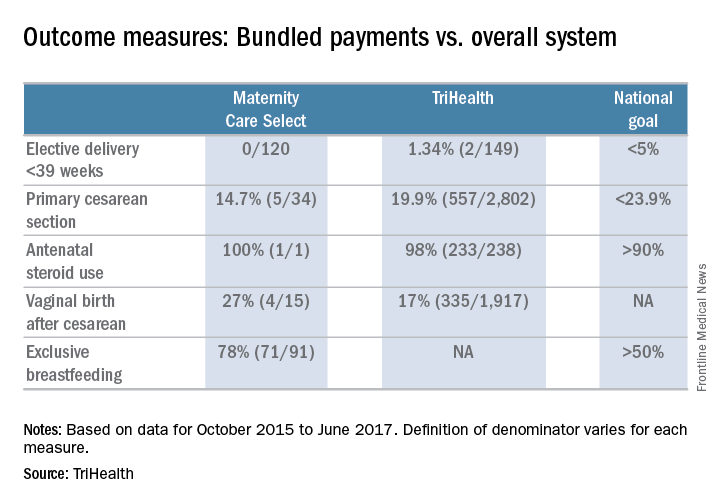

Maternity care: The challenge of paying for value

TriHealth of Cincinnati is testing the waters of value-based payment for maternity care.

The impetus came from a Cincinnati-based employer that contracts with TriHealth under its self-insured health care plan, according to Jennifer Pavelka, project lead for the health system’s Maternity Bundling Care Select Program.

“Employers are looking at the value proposition and are having keen interest in the achievement of the triple aim of optimal outcomes, optimal experience, both with a mindfulness on value, Ms. Pavelka said in an interview. “An employer that had extensive experience with other episodes of care [payments], particularly in the space of knee and hip replacements in the orthopedic world, wanted to dip their toe into a value-based program for maternity.”

“Many forays into value-based payments are very much code driven, saying this code, this service is included in the bundle and this is not,” Ms. Pavelka said. “Part of what makes our work really challenging and exciting is the fact that we have taken in the realm of the methodology and philosophy of bundles, we are implementing a prospective bundled payment model.”

Their engaged physician community has been a key factor in early successes, she added. “What heartens me the most is the degree to which the physicians have really led and informed that evolution of the program and the commitment on the partner side to say first and foremost what does the evidence say, what is clinically appropriate. That has always been our North Star.”

Even with the guidelines of eligibility, patient selection is at the physician’s discretion.

And doctors are helping to shape how women are included in the process.

“We actually have two tiers,” Dr. Marcotte said. “Tier one is the uncomplicated pregnancy and our first project was really to get consensus [around those patients]. There was quite a bit of engagement. We had several meetings at the beginning of our project to help build consensus and we continue to look at that as new evidence comes out to make sure that we are staying consistent with best practice.”

The second tier focuses on more complicated pregnancies.

“There was a reengagement with providers, both our subspecialists in maternal fetal medicine and our generalists [ob.gyns.], to rethink what are the essential elements of best practice care for a patient that has certain complications like hypertension or twins or some of the other things that we included in the tier two clinical care pathways.”

So far, very early results show that those in the bundle are in fact seeing better outcomes, something that in general is expected of a value-based payment model.

The bundled payment program also is opening the door to new service that can be provided to maternity patients.

“We are still relatively early in that journey,” Dr. Marcotte said. “We have a full-time concierge navigator who really works with this population, and we are beginning to make plans to expand that service to more patients beyond just our one population that are in the bundled care package. That’s one concrete area.”

He continued: “I think there is recognition of the need to provide more [patient] education and resources for our entire population that we are working with. Lastly, I think some of our specialized obstetric services for women with complicated pregnancies have gotten a boost. We can additionally provide those kind of services that might be extended beyond just our local community and provide attractive things that can be best in class for even those complicated pregnancies.”

TriHealth really found the key with its early and robust physician involvement, according to Malini Nijagal, MD, associate professor of ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

“The strong sense that I have is that there is a bit of a disconnect, where it feels on the ground like people believe that value-based payment models may be good for finance and health care expenditures but they are not going to be good for patients and providers,” Dr. Nijagal said in an interview. “I totally disagree.”

Rather, value-based payment models are a way to increase provider autonomy.

“Specific to maternity care and across health care, at this point, insurers are the ones who decide what services we can provide,” she said. “They have their fee schedules and that limits what we can do. What value-based payments and episode payments allow us to do is that, as providers, if we end up saving money from avoiding unnecessary interventions and diagnostics, we then get some of that money back to provide services that may not be covered.”

Dr. Nijagal and her colleagues looked at maternity care bundles and episode payment models in state Medicaid programs, managed care plans, and self-insured employers and found that physicians and other providers can benefit from participation in four ways, by:

- Finding opportunities to improve outcomes and patient experience.

- Developing better quality metrics.

- Reducing waste in the system.

- Creating stronger health care teams.

Value-based payments can “actually bring together hospitals and health care providers onto the same team and the way they do that is by tying the payment together,” Dr. Nijagal said.

The biggest challenge, according to Dr. Nijagal, is that the conversion takes time and the patience to realize that benefits will likely not be fully realized until the system is able to get to a prospective payment model, in which the real innovation can take place (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan 12. doi. org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.014).

“We are having to prioritize just getting providers to agree to doing them and because of that, we are not actually seeing the improvements in quality and cost that we would expect,” Dr. Nijagal said. “For example, a number of the programs that have been rolled out have been the upside risk only, which is superimportant because that is the way you are going to get people to feel more comfortable. It’s a stepping-stone, but you are not going to see the benefits.” And if you can’t prove benefit, it will be harder to get people to move to a two-sided risk model where the real innovation can take place.

To that end, TriHealth provides full transparency with the program so physicians can see how patients in the bundle are doing compared to the overall TriHealth patient population.

“We provide those to them in a dashboard on a monthly basis with transparency so they can see how the other providers in other practices are doing within the system,” Dr, Marcotte said.

TriHealth of Cincinnati is testing the waters of value-based payment for maternity care.

The impetus came from a Cincinnati-based employer that contracts with TriHealth under its self-insured health care plan, according to Jennifer Pavelka, project lead for the health system’s Maternity Bundling Care Select Program.

“Employers are looking at the value proposition and are having keen interest in the achievement of the triple aim of optimal outcomes, optimal experience, both with a mindfulness on value, Ms. Pavelka said in an interview. “An employer that had extensive experience with other episodes of care [payments], particularly in the space of knee and hip replacements in the orthopedic world, wanted to dip their toe into a value-based program for maternity.”

“Many forays into value-based payments are very much code driven, saying this code, this service is included in the bundle and this is not,” Ms. Pavelka said. “Part of what makes our work really challenging and exciting is the fact that we have taken in the realm of the methodology and philosophy of bundles, we are implementing a prospective bundled payment model.”

Their engaged physician community has been a key factor in early successes, she added. “What heartens me the most is the degree to which the physicians have really led and informed that evolution of the program and the commitment on the partner side to say first and foremost what does the evidence say, what is clinically appropriate. That has always been our North Star.”

Even with the guidelines of eligibility, patient selection is at the physician’s discretion.

And doctors are helping to shape how women are included in the process.

“We actually have two tiers,” Dr. Marcotte said. “Tier one is the uncomplicated pregnancy and our first project was really to get consensus [around those patients]. There was quite a bit of engagement. We had several meetings at the beginning of our project to help build consensus and we continue to look at that as new evidence comes out to make sure that we are staying consistent with best practice.”

The second tier focuses on more complicated pregnancies.

“There was a reengagement with providers, both our subspecialists in maternal fetal medicine and our generalists [ob.gyns.], to rethink what are the essential elements of best practice care for a patient that has certain complications like hypertension or twins or some of the other things that we included in the tier two clinical care pathways.”

So far, very early results show that those in the bundle are in fact seeing better outcomes, something that in general is expected of a value-based payment model.

The bundled payment program also is opening the door to new service that can be provided to maternity patients.

“We are still relatively early in that journey,” Dr. Marcotte said. “We have a full-time concierge navigator who really works with this population, and we are beginning to make plans to expand that service to more patients beyond just our one population that are in the bundled care package. That’s one concrete area.”

He continued: “I think there is recognition of the need to provide more [patient] education and resources for our entire population that we are working with. Lastly, I think some of our specialized obstetric services for women with complicated pregnancies have gotten a boost. We can additionally provide those kind of services that might be extended beyond just our local community and provide attractive things that can be best in class for even those complicated pregnancies.”

TriHealth really found the key with its early and robust physician involvement, according to Malini Nijagal, MD, associate professor of ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

“The strong sense that I have is that there is a bit of a disconnect, where it feels on the ground like people believe that value-based payment models may be good for finance and health care expenditures but they are not going to be good for patients and providers,” Dr. Nijagal said in an interview. “I totally disagree.”

Rather, value-based payment models are a way to increase provider autonomy.

“Specific to maternity care and across health care, at this point, insurers are the ones who decide what services we can provide,” she said. “They have their fee schedules and that limits what we can do. What value-based payments and episode payments allow us to do is that, as providers, if we end up saving money from avoiding unnecessary interventions and diagnostics, we then get some of that money back to provide services that may not be covered.”

Dr. Nijagal and her colleagues looked at maternity care bundles and episode payment models in state Medicaid programs, managed care plans, and self-insured employers and found that physicians and other providers can benefit from participation in four ways, by:

- Finding opportunities to improve outcomes and patient experience.

- Developing better quality metrics.

- Reducing waste in the system.

- Creating stronger health care teams.

Value-based payments can “actually bring together hospitals and health care providers onto the same team and the way they do that is by tying the payment together,” Dr. Nijagal said.

The biggest challenge, according to Dr. Nijagal, is that the conversion takes time and the patience to realize that benefits will likely not be fully realized until the system is able to get to a prospective payment model, in which the real innovation can take place (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan 12. doi. org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.014).

“We are having to prioritize just getting providers to agree to doing them and because of that, we are not actually seeing the improvements in quality and cost that we would expect,” Dr. Nijagal said. “For example, a number of the programs that have been rolled out have been the upside risk only, which is superimportant because that is the way you are going to get people to feel more comfortable. It’s a stepping-stone, but you are not going to see the benefits.” And if you can’t prove benefit, it will be harder to get people to move to a two-sided risk model where the real innovation can take place.

To that end, TriHealth provides full transparency with the program so physicians can see how patients in the bundle are doing compared to the overall TriHealth patient population.

“We provide those to them in a dashboard on a monthly basis with transparency so they can see how the other providers in other practices are doing within the system,” Dr, Marcotte said.

TriHealth of Cincinnati is testing the waters of value-based payment for maternity care.

The impetus came from a Cincinnati-based employer that contracts with TriHealth under its self-insured health care plan, according to Jennifer Pavelka, project lead for the health system’s Maternity Bundling Care Select Program.

“Employers are looking at the value proposition and are having keen interest in the achievement of the triple aim of optimal outcomes, optimal experience, both with a mindfulness on value, Ms. Pavelka said in an interview. “An employer that had extensive experience with other episodes of care [payments], particularly in the space of knee and hip replacements in the orthopedic world, wanted to dip their toe into a value-based program for maternity.”

“Many forays into value-based payments are very much code driven, saying this code, this service is included in the bundle and this is not,” Ms. Pavelka said. “Part of what makes our work really challenging and exciting is the fact that we have taken in the realm of the methodology and philosophy of bundles, we are implementing a prospective bundled payment model.”

Their engaged physician community has been a key factor in early successes, she added. “What heartens me the most is the degree to which the physicians have really led and informed that evolution of the program and the commitment on the partner side to say first and foremost what does the evidence say, what is clinically appropriate. That has always been our North Star.”

Even with the guidelines of eligibility, patient selection is at the physician’s discretion.

And doctors are helping to shape how women are included in the process.

“We actually have two tiers,” Dr. Marcotte said. “Tier one is the uncomplicated pregnancy and our first project was really to get consensus [around those patients]. There was quite a bit of engagement. We had several meetings at the beginning of our project to help build consensus and we continue to look at that as new evidence comes out to make sure that we are staying consistent with best practice.”

The second tier focuses on more complicated pregnancies.

“There was a reengagement with providers, both our subspecialists in maternal fetal medicine and our generalists [ob.gyns.], to rethink what are the essential elements of best practice care for a patient that has certain complications like hypertension or twins or some of the other things that we included in the tier two clinical care pathways.”

So far, very early results show that those in the bundle are in fact seeing better outcomes, something that in general is expected of a value-based payment model.

The bundled payment program also is opening the door to new service that can be provided to maternity patients.

“We are still relatively early in that journey,” Dr. Marcotte said. “We have a full-time concierge navigator who really works with this population, and we are beginning to make plans to expand that service to more patients beyond just our one population that are in the bundled care package. That’s one concrete area.”

He continued: “I think there is recognition of the need to provide more [patient] education and resources for our entire population that we are working with. Lastly, I think some of our specialized obstetric services for women with complicated pregnancies have gotten a boost. We can additionally provide those kind of services that might be extended beyond just our local community and provide attractive things that can be best in class for even those complicated pregnancies.”

TriHealth really found the key with its early and robust physician involvement, according to Malini Nijagal, MD, associate professor of ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

“The strong sense that I have is that there is a bit of a disconnect, where it feels on the ground like people believe that value-based payment models may be good for finance and health care expenditures but they are not going to be good for patients and providers,” Dr. Nijagal said in an interview. “I totally disagree.”

Rather, value-based payment models are a way to increase provider autonomy.

“Specific to maternity care and across health care, at this point, insurers are the ones who decide what services we can provide,” she said. “They have their fee schedules and that limits what we can do. What value-based payments and episode payments allow us to do is that, as providers, if we end up saving money from avoiding unnecessary interventions and diagnostics, we then get some of that money back to provide services that may not be covered.”

Dr. Nijagal and her colleagues looked at maternity care bundles and episode payment models in state Medicaid programs, managed care plans, and self-insured employers and found that physicians and other providers can benefit from participation in four ways, by:

- Finding opportunities to improve outcomes and patient experience.

- Developing better quality metrics.

- Reducing waste in the system.

- Creating stronger health care teams.

Value-based payments can “actually bring together hospitals and health care providers onto the same team and the way they do that is by tying the payment together,” Dr. Nijagal said.

The biggest challenge, according to Dr. Nijagal, is that the conversion takes time and the patience to realize that benefits will likely not be fully realized until the system is able to get to a prospective payment model, in which the real innovation can take place (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan 12. doi. org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.014).

“We are having to prioritize just getting providers to agree to doing them and because of that, we are not actually seeing the improvements in quality and cost that we would expect,” Dr. Nijagal said. “For example, a number of the programs that have been rolled out have been the upside risk only, which is superimportant because that is the way you are going to get people to feel more comfortable. It’s a stepping-stone, but you are not going to see the benefits.” And if you can’t prove benefit, it will be harder to get people to move to a two-sided risk model where the real innovation can take place.

To that end, TriHealth provides full transparency with the program so physicians can see how patients in the bundle are doing compared to the overall TriHealth patient population.

“We provide those to them in a dashboard on a monthly basis with transparency so they can see how the other providers in other practices are doing within the system,” Dr, Marcotte said.

Taming or teaching the tiger? Myths and management of childhood aggression

How to deal with aggression delivered by a child’s peers is a common concern and social dilemma for both parents and children. How does a child ward off aggressive peers without getting hurt or in trouble while also not looking weak or whiny? What can parents do to stop their child from being hurt or frightened but also not humiliate them or interfere with their learning important life skills by being over protective?

Children do not want to fight, but they do want to be treated fairly. Frustration, with its associated feelings of anger, is the most common reason for aggression. Being a child is certainly full of its frustrations because, while autonomy and desires are increasing, opportunities expand at a slower rate, particularly for children with developmental weaknesses or economic disadvantage. Fear and a lack of coping skills are other major reasons for resorting to aggressive responses.

Physical bullying affects 21% of students in grades 3-12 and is a risk factor for aggression at all ages. A full one-third of 9th-12th graders report having been in a physical fight in the last year. In grade school age and adolescence, factors known to be associated with peer aggression include the humiliation of school failure, substance use, and anger from experiencing parental or sibling aggression.

One would think a universal goal of parents would be to raise their children to get along with others without fighting. Unfortunately, some parents actually espouse childrearing methods that directly or indirectly make fighting more likely.

Essentially all toddlers and preschoolers can be aggressive at times to get things they want (instrumental) or when angry in the beginning of their second year of life; this peaks in the third year and typically declines after age 3 years. But for some 10% of children, aggression remains high. What parent and child factors set children up for such persistent aggression?

Parents have many reasons for how they raise their children, but some myths about parenting that persist promote aggression.

“My child will love me more if I am more permissive.”

Infants and toddlers develop self-regulation skills better when it is gradually expected of them with encouragement and support from their parents. Parents may feel that they are showing love to their toddler by having a “relaxed” home with few limits and no specific bedtime or rules. These parents also may “rescue” their child from frustrating situations by giving in to their demands or removing them from even mildly stressful situations.

These strategies can interfere with the progressive development of frustration tolerance, a key life skill. A lack of routines, inadequate sleep or food, overstimulation by noise, frightening experiences (including fighting in the home or neighborhood), or violent media exposure sets toddlers up to be out of control and thereby increases dysregulation. In addition, the dysregulated child may then act up, which can invoke punishment from that same parent.