User login

VIDEO: Painful skin conditions need pain management by dermatologists

Patients with painful skin conditions need pain management that is provided by their dermatologists, Robert G. Micheletti, MD, contended in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dermatologists are the experts when it comes to treating painful skin conditions like pyoderma gangrenosum, hidradenitis suppurativa, calciphylaxis, and vasculopathies. “We should be willing to treat the pain that goes with (these conditions), at least within our scope of practice,” said Dr. Micheletti, co-director of the Inpatient Dermatology Consult Service at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “At the same time, we know opioids should be prescribed only when necessary, at the lowest effective dose, and for the shortest possible duration.”

In our exclusive video interview, Dr. Micheletti outlined the keys to successful care of patients with painful skin disease. He described patient characteristics that influence prescribing choices and tips for accurately assessing pain needs with a preference for a conservative regimen that utilizes non-opioids and avoids over-reliance on narcotics.

Source: Micheletti, R., Session F013

Patients with painful skin conditions need pain management that is provided by their dermatologists, Robert G. Micheletti, MD, contended in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dermatologists are the experts when it comes to treating painful skin conditions like pyoderma gangrenosum, hidradenitis suppurativa, calciphylaxis, and vasculopathies. “We should be willing to treat the pain that goes with (these conditions), at least within our scope of practice,” said Dr. Micheletti, co-director of the Inpatient Dermatology Consult Service at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “At the same time, we know opioids should be prescribed only when necessary, at the lowest effective dose, and for the shortest possible duration.”

In our exclusive video interview, Dr. Micheletti outlined the keys to successful care of patients with painful skin disease. He described patient characteristics that influence prescribing choices and tips for accurately assessing pain needs with a preference for a conservative regimen that utilizes non-opioids and avoids over-reliance on narcotics.

Source: Micheletti, R., Session F013

Patients with painful skin conditions need pain management that is provided by their dermatologists, Robert G. Micheletti, MD, contended in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dermatologists are the experts when it comes to treating painful skin conditions like pyoderma gangrenosum, hidradenitis suppurativa, calciphylaxis, and vasculopathies. “We should be willing to treat the pain that goes with (these conditions), at least within our scope of practice,” said Dr. Micheletti, co-director of the Inpatient Dermatology Consult Service at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “At the same time, we know opioids should be prescribed only when necessary, at the lowest effective dose, and for the shortest possible duration.”

In our exclusive video interview, Dr. Micheletti outlined the keys to successful care of patients with painful skin disease. He described patient characteristics that influence prescribing choices and tips for accurately assessing pain needs with a preference for a conservative regimen that utilizes non-opioids and avoids over-reliance on narcotics.

Source: Micheletti, R., Session F013

VIDEO: Delusional parasitosis? Try these real solutions

SAN DIEGO – The path to successful treatment of patients with imagined skin disorders is paved with compassion, according to John Koo, MD, a dermatologist and psychiatrist with the University of California at San Francisco.

When a patient presents with delusional parasitosis -- horror stories about imagined infestations of parasites or bugs – the key to successful treatment is a positive attitude and validation, not denial, Dr. Koo said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

"I cannot afford to go in (the exam room) with a long face," he said. "If I go in and I’m not looking happy, things can deteriorate quickly. So I make sure I go in with the biggest smile on my face like I'm meeting my favorite Hollywood star."

"When I say something like 'It's like a living hell, isn't it,' patients are really touched, he said. The patient’s response is typically 'You're the first dermatologist to understand what I'm going through.' You cannot endorse their delusion, but you can endorse their suffering."

In our video interview, Dr. Koo delved into techniques for the successful work-up and evaluation of patients with delusional parasitosis, the varying degrees of the condition, medications used for treatment, and the prospects for eventual drug-free relief.

Dr. Koo reports no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The path to successful treatment of patients with imagined skin disorders is paved with compassion, according to John Koo, MD, a dermatologist and psychiatrist with the University of California at San Francisco.

When a patient presents with delusional parasitosis -- horror stories about imagined infestations of parasites or bugs – the key to successful treatment is a positive attitude and validation, not denial, Dr. Koo said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

"I cannot afford to go in (the exam room) with a long face," he said. "If I go in and I’m not looking happy, things can deteriorate quickly. So I make sure I go in with the biggest smile on my face like I'm meeting my favorite Hollywood star."

"When I say something like 'It's like a living hell, isn't it,' patients are really touched, he said. The patient’s response is typically 'You're the first dermatologist to understand what I'm going through.' You cannot endorse their delusion, but you can endorse their suffering."

In our video interview, Dr. Koo delved into techniques for the successful work-up and evaluation of patients with delusional parasitosis, the varying degrees of the condition, medications used for treatment, and the prospects for eventual drug-free relief.

Dr. Koo reports no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The path to successful treatment of patients with imagined skin disorders is paved with compassion, according to John Koo, MD, a dermatologist and psychiatrist with the University of California at San Francisco.

When a patient presents with delusional parasitosis -- horror stories about imagined infestations of parasites or bugs – the key to successful treatment is a positive attitude and validation, not denial, Dr. Koo said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

"I cannot afford to go in (the exam room) with a long face," he said. "If I go in and I’m not looking happy, things can deteriorate quickly. So I make sure I go in with the biggest smile on my face like I'm meeting my favorite Hollywood star."

"When I say something like 'It's like a living hell, isn't it,' patients are really touched, he said. The patient’s response is typically 'You're the first dermatologist to understand what I'm going through.' You cannot endorse their delusion, but you can endorse their suffering."

In our video interview, Dr. Koo delved into techniques for the successful work-up and evaluation of patients with delusional parasitosis, the varying degrees of the condition, medications used for treatment, and the prospects for eventual drug-free relief.

Dr. Koo reports no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

Balancing quality and cost of care with patient well-being

Welcome to the first issue of The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology for this year. 2017 was a rollercoaster year for the oncology community, literally from day 1. January 1 saw the kick-off for participation in the MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act] Quality Payment Program, and soon after came the growing concern and uncertainty around the future of President Barack Obama’s Affordable Health Care Act. Attempts during the year to repeal the ACA failed, but with the December passage of the tax bill came Medicare cuts and the repeal of the individual mandate, which will effectively sever crucial revenue sources for the ACA. Nevertheless, against that backdrop, there was a slew of exciting therapeutic approvals – some of them landmark, as my fellow Editor, Linda Bosserman, noted in her year-end editorial (JCSO 2017;15[6]:e283-e290). As often happens, and as noted in the editorial, such advances come with concerns about the high cost of the therapies and their related toxicities, and the combined negative impact of those on quality and cost of care and patient quality of life. (QoL).

In this issue, 2 research articles examine bone metastasis in late-stage disease and their findings underscore the aforementioned importance of care cost and quality and patient QoL. Bone metastases are a common cause of pain in patients with advanced cancer. That pain is often associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and fatigue, and patient QoL will diminish if the pain is not adequately treated. Although radiotherapy is effective in palliating painful bone metastases, relief may be delayed and interim analgesic management needed. Garcia and colleagues (p. e8) examined the frequency of analgesic regimen assessment and intervention during radiation oncology consultations for bone metastases and evaluated the impact on analgesic management before and after implementation of a dedicated palliative radiation oncology service. They found that pain assessment and intervention were not common in the radiation oncology setting before establishment of the service and suggest that integrating palliative care within radiation oncology could improve the quality of pain management and by extension, patient well-being.

Patients with bone metastases are also at greater risk of bone fracture, for which they often are hospitalized at great cost. Nikkel and colleagues sought to determine the primary tumors in patients hospitalized with metastatic disease and who sustained pathologic and nonpathologic fractures, and to estimate the costs and lengths of stay for those hospitalizations (p. e14). The most common primary cancers in these patients were lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and colorectal – a novel finding in this study was that there were almost 4 times as many pathologic fractures from colorectal than from thyroid carcinoma. Patients hospitalized for pathologic fracture had higher billed costs and longer length of stay. The authors emphasize the importance of identifying patients at risk for pathological fracture based on primary tumor type, age, and socio-economic group; improving surveillance; and doing timely osteoporosis screening.

Therapeutic advances and the ensuing new options and combination possibilities are the substrate for our daily engagement with our patients. On page e53, Dr David Henry, the JCSO Editor-in-Chief, talks with Dr Kenneth Anderson of Harvard Medical School about advances in multiple myeloma therapies and how numerous therapy approvals have pushed the disease closer to becoming a manageable, chronic disease. On page e47, Jane de Lartigue describes the latest developments in the therapeutic targeting of altered metabolic pathways in cancer cells.

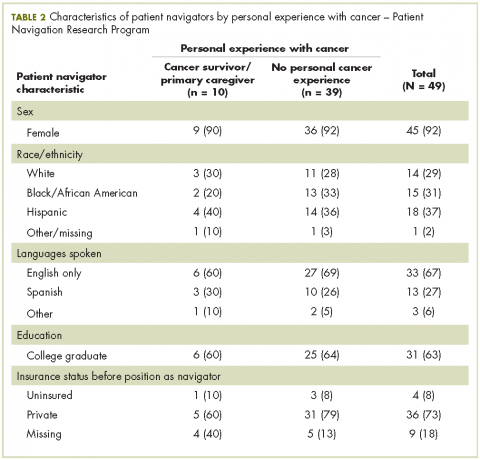

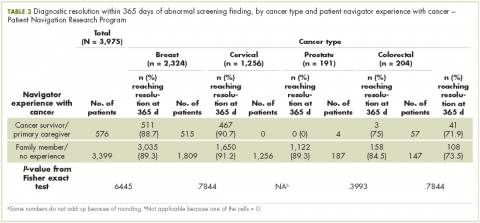

Also in this issue are new approval updates for abemaciclib as the first CDK inhibitor for breast cancer (p. e2) and the checkpoint inhibitors avelumab and durvalumab for metastatic bladder cancer (p. e5), a brief report on whether patient navigators’ personal experience with cancer has any effect on patient experience (p. e43), a research article on physical activity and sedentary behavior in survivors of breast cancer, and Case Reports (pp. e30-e42).

Welcome to the first issue of The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology for this year. 2017 was a rollercoaster year for the oncology community, literally from day 1. January 1 saw the kick-off for participation in the MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act] Quality Payment Program, and soon after came the growing concern and uncertainty around the future of President Barack Obama’s Affordable Health Care Act. Attempts during the year to repeal the ACA failed, but with the December passage of the tax bill came Medicare cuts and the repeal of the individual mandate, which will effectively sever crucial revenue sources for the ACA. Nevertheless, against that backdrop, there was a slew of exciting therapeutic approvals – some of them landmark, as my fellow Editor, Linda Bosserman, noted in her year-end editorial (JCSO 2017;15[6]:e283-e290). As often happens, and as noted in the editorial, such advances come with concerns about the high cost of the therapies and their related toxicities, and the combined negative impact of those on quality and cost of care and patient quality of life. (QoL).

In this issue, 2 research articles examine bone metastasis in late-stage disease and their findings underscore the aforementioned importance of care cost and quality and patient QoL. Bone metastases are a common cause of pain in patients with advanced cancer. That pain is often associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and fatigue, and patient QoL will diminish if the pain is not adequately treated. Although radiotherapy is effective in palliating painful bone metastases, relief may be delayed and interim analgesic management needed. Garcia and colleagues (p. e8) examined the frequency of analgesic regimen assessment and intervention during radiation oncology consultations for bone metastases and evaluated the impact on analgesic management before and after implementation of a dedicated palliative radiation oncology service. They found that pain assessment and intervention were not common in the radiation oncology setting before establishment of the service and suggest that integrating palliative care within radiation oncology could improve the quality of pain management and by extension, patient well-being.

Patients with bone metastases are also at greater risk of bone fracture, for which they often are hospitalized at great cost. Nikkel and colleagues sought to determine the primary tumors in patients hospitalized with metastatic disease and who sustained pathologic and nonpathologic fractures, and to estimate the costs and lengths of stay for those hospitalizations (p. e14). The most common primary cancers in these patients were lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and colorectal – a novel finding in this study was that there were almost 4 times as many pathologic fractures from colorectal than from thyroid carcinoma. Patients hospitalized for pathologic fracture had higher billed costs and longer length of stay. The authors emphasize the importance of identifying patients at risk for pathological fracture based on primary tumor type, age, and socio-economic group; improving surveillance; and doing timely osteoporosis screening.

Therapeutic advances and the ensuing new options and combination possibilities are the substrate for our daily engagement with our patients. On page e53, Dr David Henry, the JCSO Editor-in-Chief, talks with Dr Kenneth Anderson of Harvard Medical School about advances in multiple myeloma therapies and how numerous therapy approvals have pushed the disease closer to becoming a manageable, chronic disease. On page e47, Jane de Lartigue describes the latest developments in the therapeutic targeting of altered metabolic pathways in cancer cells.

Also in this issue are new approval updates for abemaciclib as the first CDK inhibitor for breast cancer (p. e2) and the checkpoint inhibitors avelumab and durvalumab for metastatic bladder cancer (p. e5), a brief report on whether patient navigators’ personal experience with cancer has any effect on patient experience (p. e43), a research article on physical activity and sedentary behavior in survivors of breast cancer, and Case Reports (pp. e30-e42).

Welcome to the first issue of The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology for this year. 2017 was a rollercoaster year for the oncology community, literally from day 1. January 1 saw the kick-off for participation in the MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act] Quality Payment Program, and soon after came the growing concern and uncertainty around the future of President Barack Obama’s Affordable Health Care Act. Attempts during the year to repeal the ACA failed, but with the December passage of the tax bill came Medicare cuts and the repeal of the individual mandate, which will effectively sever crucial revenue sources for the ACA. Nevertheless, against that backdrop, there was a slew of exciting therapeutic approvals – some of them landmark, as my fellow Editor, Linda Bosserman, noted in her year-end editorial (JCSO 2017;15[6]:e283-e290). As often happens, and as noted in the editorial, such advances come with concerns about the high cost of the therapies and their related toxicities, and the combined negative impact of those on quality and cost of care and patient quality of life. (QoL).

In this issue, 2 research articles examine bone metastasis in late-stage disease and their findings underscore the aforementioned importance of care cost and quality and patient QoL. Bone metastases are a common cause of pain in patients with advanced cancer. That pain is often associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and fatigue, and patient QoL will diminish if the pain is not adequately treated. Although radiotherapy is effective in palliating painful bone metastases, relief may be delayed and interim analgesic management needed. Garcia and colleagues (p. e8) examined the frequency of analgesic regimen assessment and intervention during radiation oncology consultations for bone metastases and evaluated the impact on analgesic management before and after implementation of a dedicated palliative radiation oncology service. They found that pain assessment and intervention were not common in the radiation oncology setting before establishment of the service and suggest that integrating palliative care within radiation oncology could improve the quality of pain management and by extension, patient well-being.

Patients with bone metastases are also at greater risk of bone fracture, for which they often are hospitalized at great cost. Nikkel and colleagues sought to determine the primary tumors in patients hospitalized with metastatic disease and who sustained pathologic and nonpathologic fractures, and to estimate the costs and lengths of stay for those hospitalizations (p. e14). The most common primary cancers in these patients were lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and colorectal – a novel finding in this study was that there were almost 4 times as many pathologic fractures from colorectal than from thyroid carcinoma. Patients hospitalized for pathologic fracture had higher billed costs and longer length of stay. The authors emphasize the importance of identifying patients at risk for pathological fracture based on primary tumor type, age, and socio-economic group; improving surveillance; and doing timely osteoporosis screening.

Therapeutic advances and the ensuing new options and combination possibilities are the substrate for our daily engagement with our patients. On page e53, Dr David Henry, the JCSO Editor-in-Chief, talks with Dr Kenneth Anderson of Harvard Medical School about advances in multiple myeloma therapies and how numerous therapy approvals have pushed the disease closer to becoming a manageable, chronic disease. On page e47, Jane de Lartigue describes the latest developments in the therapeutic targeting of altered metabolic pathways in cancer cells.

Also in this issue are new approval updates for abemaciclib as the first CDK inhibitor for breast cancer (p. e2) and the checkpoint inhibitors avelumab and durvalumab for metastatic bladder cancer (p. e5), a brief report on whether patient navigators’ personal experience with cancer has any effect on patient experience (p. e43), a research article on physical activity and sedentary behavior in survivors of breast cancer, and Case Reports (pp. e30-e42).

Topical anticholinergic improved hyperhidrosis in children

SAN DIEGO – A topical anticholinergic drug, glycopyrronium tosylate, was as safe and effective for treating hyperhidrosis in children 9-16 years old as it was in adults in two phase 3 trials that included 25 treated children, raising the prospect it could become the first drug to gain Food and Drug Administration approval for treating pediatric hyperhidrosis.

“Topical glycopyrronium tosylate treatment may provide a much needed treatment option for those with primary axillary hyperhidrosis, including pediatric patients,” Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The data she reported from a post hoc analysis included 25 children. 9-16 years old, who received a daily, topical application of glycopyrronium tosylate to their underarms for 4 weeks and 19 children treated with vehicle only. The children were enrolled in either of a pair of phase 3 pivotal trials that together randomized 697 patients. In November 2017, Dermira, the company developing this drug, submitted an application to the FDA for marketing approval of the agent for adults and children at least 9 years old. A statement from the company said an FDA decision is expected by mid-2018.

Getting approval from the FDA for an effective pediatric hyperhidrosis treatment would be an important advance because nothing now exists in that space, said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics and director of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston.

Based on past FDA actions, safety data from 25 children should be adequate to support pediatric labeling, she said in an interview, though she added that confirmatory safety data from a phase 4 study in children would be a welcome future addition. Hyperhydrosis in adolescents is “underappreciated, underdiagnosed, and is very impactful,” and currently has limited treatment options that are readily available for children, especially effective options for more severe hyperhidrosis.

The pediatric data came from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled ATMOS-1 (DRM04 in Subjects With Axillary Hyperhidrosis) trial. The trial ran at several U.S. and German centers, although only the U.S. centers enrolled pediatric patients.

The two trials enrolled patients with “intolerable or barely tolerable” primary, axillary hyperhidrosis of at least 6 months' duration. After 4 weeks, patients treated with glycopyrronium tosylate had improvements in their daily diary account of axillary sweating and in sweat production. Dr. Hebert and her associates reported overall results from the two trials at various prior dermatology meetings, and the company reported some of the results in a press release, but the results have not yet been published in a journal.

The new, pediatric analysis that Dr. Hebert reported showed that the responder rate based on a 4 point or greater improvement in daily sweat diary assessments occurred in 60% of the actively treated children and in 13% of the controls. A 50% or greater reduction in sweat production occurred in 80% of the treated children and in 55% of controls. Quality of life, measured using the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index improved by an average of 8 points among the treated children, compared with an average 2-point improvement among the controls. This level of improvement among the glycopyrronium-treated patients would have been enough to move patients from the moderate-effect category at baseline to a no- or small-effect category.

The treatment was generally well tolerated, with no serious adverse effects reported and with treatment effects that were primarily as expected from an anticholinergic agent, including dry mouth, pupil dilation, and blurred vision. One of the 25 treated children withdrew because of these effects, which then resolved. Blood testing showed no systemic absorption of the drug, Dr. Hebert said.

The ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 trials were sponsored by Dermira, the company developing glycopyrronium tosylate. Dr. Hebert has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Dermira, and some of the coauthors of the study are Dermira employees. Dr. Hebert is an advisor to the editorial board of Dermatology News.

SOURCE: Hebert A et al. Annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology Abstract 6659.

SAN DIEGO – A topical anticholinergic drug, glycopyrronium tosylate, was as safe and effective for treating hyperhidrosis in children 9-16 years old as it was in adults in two phase 3 trials that included 25 treated children, raising the prospect it could become the first drug to gain Food and Drug Administration approval for treating pediatric hyperhidrosis.

“Topical glycopyrronium tosylate treatment may provide a much needed treatment option for those with primary axillary hyperhidrosis, including pediatric patients,” Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The data she reported from a post hoc analysis included 25 children. 9-16 years old, who received a daily, topical application of glycopyrronium tosylate to their underarms for 4 weeks and 19 children treated with vehicle only. The children were enrolled in either of a pair of phase 3 pivotal trials that together randomized 697 patients. In November 2017, Dermira, the company developing this drug, submitted an application to the FDA for marketing approval of the agent for adults and children at least 9 years old. A statement from the company said an FDA decision is expected by mid-2018.

Getting approval from the FDA for an effective pediatric hyperhidrosis treatment would be an important advance because nothing now exists in that space, said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics and director of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston.

Based on past FDA actions, safety data from 25 children should be adequate to support pediatric labeling, she said in an interview, though she added that confirmatory safety data from a phase 4 study in children would be a welcome future addition. Hyperhydrosis in adolescents is “underappreciated, underdiagnosed, and is very impactful,” and currently has limited treatment options that are readily available for children, especially effective options for more severe hyperhidrosis.

The pediatric data came from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled ATMOS-1 (DRM04 in Subjects With Axillary Hyperhidrosis) trial. The trial ran at several U.S. and German centers, although only the U.S. centers enrolled pediatric patients.

The two trials enrolled patients with “intolerable or barely tolerable” primary, axillary hyperhidrosis of at least 6 months' duration. After 4 weeks, patients treated with glycopyrronium tosylate had improvements in their daily diary account of axillary sweating and in sweat production. Dr. Hebert and her associates reported overall results from the two trials at various prior dermatology meetings, and the company reported some of the results in a press release, but the results have not yet been published in a journal.

The new, pediatric analysis that Dr. Hebert reported showed that the responder rate based on a 4 point or greater improvement in daily sweat diary assessments occurred in 60% of the actively treated children and in 13% of the controls. A 50% or greater reduction in sweat production occurred in 80% of the treated children and in 55% of controls. Quality of life, measured using the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index improved by an average of 8 points among the treated children, compared with an average 2-point improvement among the controls. This level of improvement among the glycopyrronium-treated patients would have been enough to move patients from the moderate-effect category at baseline to a no- or small-effect category.

The treatment was generally well tolerated, with no serious adverse effects reported and with treatment effects that were primarily as expected from an anticholinergic agent, including dry mouth, pupil dilation, and blurred vision. One of the 25 treated children withdrew because of these effects, which then resolved. Blood testing showed no systemic absorption of the drug, Dr. Hebert said.

The ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 trials were sponsored by Dermira, the company developing glycopyrronium tosylate. Dr. Hebert has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Dermira, and some of the coauthors of the study are Dermira employees. Dr. Hebert is an advisor to the editorial board of Dermatology News.

SOURCE: Hebert A et al. Annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology Abstract 6659.

SAN DIEGO – A topical anticholinergic drug, glycopyrronium tosylate, was as safe and effective for treating hyperhidrosis in children 9-16 years old as it was in adults in two phase 3 trials that included 25 treated children, raising the prospect it could become the first drug to gain Food and Drug Administration approval for treating pediatric hyperhidrosis.

“Topical glycopyrronium tosylate treatment may provide a much needed treatment option for those with primary axillary hyperhidrosis, including pediatric patients,” Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The data she reported from a post hoc analysis included 25 children. 9-16 years old, who received a daily, topical application of glycopyrronium tosylate to their underarms for 4 weeks and 19 children treated with vehicle only. The children were enrolled in either of a pair of phase 3 pivotal trials that together randomized 697 patients. In November 2017, Dermira, the company developing this drug, submitted an application to the FDA for marketing approval of the agent for adults and children at least 9 years old. A statement from the company said an FDA decision is expected by mid-2018.

Getting approval from the FDA for an effective pediatric hyperhidrosis treatment would be an important advance because nothing now exists in that space, said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics and director of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston.

Based on past FDA actions, safety data from 25 children should be adequate to support pediatric labeling, she said in an interview, though she added that confirmatory safety data from a phase 4 study in children would be a welcome future addition. Hyperhydrosis in adolescents is “underappreciated, underdiagnosed, and is very impactful,” and currently has limited treatment options that are readily available for children, especially effective options for more severe hyperhidrosis.

The pediatric data came from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled ATMOS-1 (DRM04 in Subjects With Axillary Hyperhidrosis) trial. The trial ran at several U.S. and German centers, although only the U.S. centers enrolled pediatric patients.

The two trials enrolled patients with “intolerable or barely tolerable” primary, axillary hyperhidrosis of at least 6 months' duration. After 4 weeks, patients treated with glycopyrronium tosylate had improvements in their daily diary account of axillary sweating and in sweat production. Dr. Hebert and her associates reported overall results from the two trials at various prior dermatology meetings, and the company reported some of the results in a press release, but the results have not yet been published in a journal.

The new, pediatric analysis that Dr. Hebert reported showed that the responder rate based on a 4 point or greater improvement in daily sweat diary assessments occurred in 60% of the actively treated children and in 13% of the controls. A 50% or greater reduction in sweat production occurred in 80% of the treated children and in 55% of controls. Quality of life, measured using the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index improved by an average of 8 points among the treated children, compared with an average 2-point improvement among the controls. This level of improvement among the glycopyrronium-treated patients would have been enough to move patients from the moderate-effect category at baseline to a no- or small-effect category.

The treatment was generally well tolerated, with no serious adverse effects reported and with treatment effects that were primarily as expected from an anticholinergic agent, including dry mouth, pupil dilation, and blurred vision. One of the 25 treated children withdrew because of these effects, which then resolved. Blood testing showed no systemic absorption of the drug, Dr. Hebert said.

The ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 trials were sponsored by Dermira, the company developing glycopyrronium tosylate. Dr. Hebert has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Dermira, and some of the coauthors of the study are Dermira employees. Dr. Hebert is an advisor to the editorial board of Dermatology News.

SOURCE: Hebert A et al. Annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology Abstract 6659.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

Key clinical point: Max. Daily, topical glycopyrronium tosylate safely controlled pediatric hyperhidrosis.

Major finding: At least a 4-point improvement in the axillary sweating daily diary score occurred in 60% of treated patients and in 13% of controls.

Study details: Post hoc analysis of data from 44 children enrolled in either of two pivotal trials, ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2.

Disclosures: The ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 trials were sponsored by Dermira, the company developing glycopyrronium tosylate. Dr. Hebert has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Dermira, and some of the coauthors of the study are Dermira employees. Dr. Hebert is an adviser to the editorial board of Dermatology News.

Source: Hebert A et al. AAD 2018, Abstract 6659.

VIDEO: Gene test guides need for sentinel node biopsy in elderly melanoma patients

SAN DIEGO – The results of a gene expression test, along with tumor thickness and patient age, can guide the need for sentinel lymph node biopsy, based on results from more than1,400 consecutively tested patients from 26 U.S. surgical oncology, medical oncology and dermatologic practices.

The findings, presented by John Vetto, MD, at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, indicate the DecisionDx test correctly identified patients aged 65 and older with T1-T2 tumors whose risk of sentinel node metastasis was lower than 5%. The most recent melanoma guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that clinicians “discuss and offer” sentinel node biopsy if a patient has a greater than 10% likelihood of a positive node. If the likelihood is 5%-10%, the recommendation is to “discuss and consider” the procedure. But if the likelihood of a positive node is less than 5%, the guidelines recommend against a biopsy.

“Sentinel node biopsy (has) risks, especially in medically compromised older patients,” Dr. Vetto, professor of surgery at the Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, said in an interview, in which he discussed clinical use of the test. “This test offers us a good way to assess the risk/benefit ratio so we can better care for patients, and follow the newest guidelines about sentinel node biopsy.”

The DecisionDx Melanoma, developed by Castle Biosciences, tests for the expression of 28 genes know to play a role in melanoma metastasis, and three control genes. Tumors are stratified either as Class 1, with a 3% chance of spreading within 5 years, or Class 2, with a 69% risk of metastasis. There are two subclasses: 1A, which has an extremely low risk of progression, and 2b, which has an extremely high risk of progression.

For patients with T1-T2 tumors who had a Class 1A test result (lowest risk of recurrence), SLN positivity was 4.6% for all ages, 2.8% in patients 55 years and older, and 1.6% in patients 65 years and older. For patients with T1-T2 tumors who had a Class 2B test result (highest risk of recurrence), SLN positivity was 18.8% for all ages, 16.4% in patients 55 years and older and 11.9% in patients 65 years and older.

Dr. Vetto is a paid speaker for Castle Biosciences.

SOURCE: Vetto et al. AAD 2018 late-breaking research, Abstract 6805

SAN DIEGO – The results of a gene expression test, along with tumor thickness and patient age, can guide the need for sentinel lymph node biopsy, based on results from more than1,400 consecutively tested patients from 26 U.S. surgical oncology, medical oncology and dermatologic practices.

The findings, presented by John Vetto, MD, at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, indicate the DecisionDx test correctly identified patients aged 65 and older with T1-T2 tumors whose risk of sentinel node metastasis was lower than 5%. The most recent melanoma guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that clinicians “discuss and offer” sentinel node biopsy if a patient has a greater than 10% likelihood of a positive node. If the likelihood is 5%-10%, the recommendation is to “discuss and consider” the procedure. But if the likelihood of a positive node is less than 5%, the guidelines recommend against a biopsy.

“Sentinel node biopsy (has) risks, especially in medically compromised older patients,” Dr. Vetto, professor of surgery at the Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, said in an interview, in which he discussed clinical use of the test. “This test offers us a good way to assess the risk/benefit ratio so we can better care for patients, and follow the newest guidelines about sentinel node biopsy.”

The DecisionDx Melanoma, developed by Castle Biosciences, tests for the expression of 28 genes know to play a role in melanoma metastasis, and three control genes. Tumors are stratified either as Class 1, with a 3% chance of spreading within 5 years, or Class 2, with a 69% risk of metastasis. There are two subclasses: 1A, which has an extremely low risk of progression, and 2b, which has an extremely high risk of progression.

For patients with T1-T2 tumors who had a Class 1A test result (lowest risk of recurrence), SLN positivity was 4.6% for all ages, 2.8% in patients 55 years and older, and 1.6% in patients 65 years and older. For patients with T1-T2 tumors who had a Class 2B test result (highest risk of recurrence), SLN positivity was 18.8% for all ages, 16.4% in patients 55 years and older and 11.9% in patients 65 years and older.

Dr. Vetto is a paid speaker for Castle Biosciences.

SOURCE: Vetto et al. AAD 2018 late-breaking research, Abstract 6805

SAN DIEGO – The results of a gene expression test, along with tumor thickness and patient age, can guide the need for sentinel lymph node biopsy, based on results from more than1,400 consecutively tested patients from 26 U.S. surgical oncology, medical oncology and dermatologic practices.

The findings, presented by John Vetto, MD, at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, indicate the DecisionDx test correctly identified patients aged 65 and older with T1-T2 tumors whose risk of sentinel node metastasis was lower than 5%. The most recent melanoma guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that clinicians “discuss and offer” sentinel node biopsy if a patient has a greater than 10% likelihood of a positive node. If the likelihood is 5%-10%, the recommendation is to “discuss and consider” the procedure. But if the likelihood of a positive node is less than 5%, the guidelines recommend against a biopsy.

“Sentinel node biopsy (has) risks, especially in medically compromised older patients,” Dr. Vetto, professor of surgery at the Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, said in an interview, in which he discussed clinical use of the test. “This test offers us a good way to assess the risk/benefit ratio so we can better care for patients, and follow the newest guidelines about sentinel node biopsy.”

The DecisionDx Melanoma, developed by Castle Biosciences, tests for the expression of 28 genes know to play a role in melanoma metastasis, and three control genes. Tumors are stratified either as Class 1, with a 3% chance of spreading within 5 years, or Class 2, with a 69% risk of metastasis. There are two subclasses: 1A, which has an extremely low risk of progression, and 2b, which has an extremely high risk of progression.

For patients with T1-T2 tumors who had a Class 1A test result (lowest risk of recurrence), SLN positivity was 4.6% for all ages, 2.8% in patients 55 years and older, and 1.6% in patients 65 years and older. For patients with T1-T2 tumors who had a Class 2B test result (highest risk of recurrence), SLN positivity was 18.8% for all ages, 16.4% in patients 55 years and older and 11.9% in patients 65 years and older.

Dr. Vetto is a paid speaker for Castle Biosciences.

SOURCE: Vetto et al. AAD 2018 late-breaking research, Abstract 6805

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

Massive liver metastasis from colon adenocarcinoma causing cardiac tamponade

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 About 5% of Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime, of which 20% will present with distant metastasis.2 The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum, and patients may present with signs or symptoms related to disease burden at any of these organs.

Case presentation and summary

A 55-year-old man had presented to an outside hospital in August of 2014 with 6 months of hematochezia and a 40-lb weight loss. He was found to be severely anemic on admission (hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL [normal, 13-17 g/dL], hematocrit, 16% [normal, 35%-45%]). A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a mass of 6.9 x 4.7 x 6.3 cm in the rectosigmoid colon and a mass of 10.0 x 12.0 x 10.7 cm in the right hepatic lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient was taken to the operating room where the rectosigmoid mass was resected completely. The liver mass was deemed unresectable because of its large size, and surgically directed therapy could not be performed. Pathology was consistent with a T3N1 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma 11 cm from the anal verge. Further molecular tumor studies revealed wild type KRAS and NRAS, as well as a BRAF mutation.

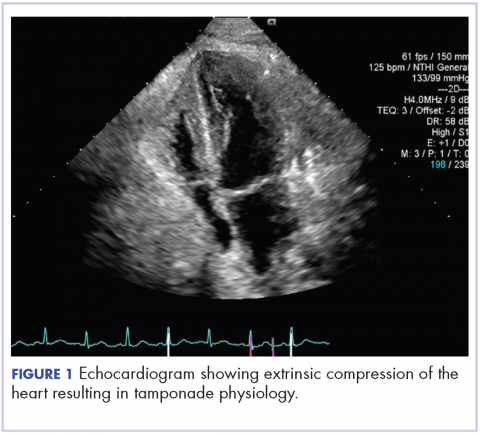

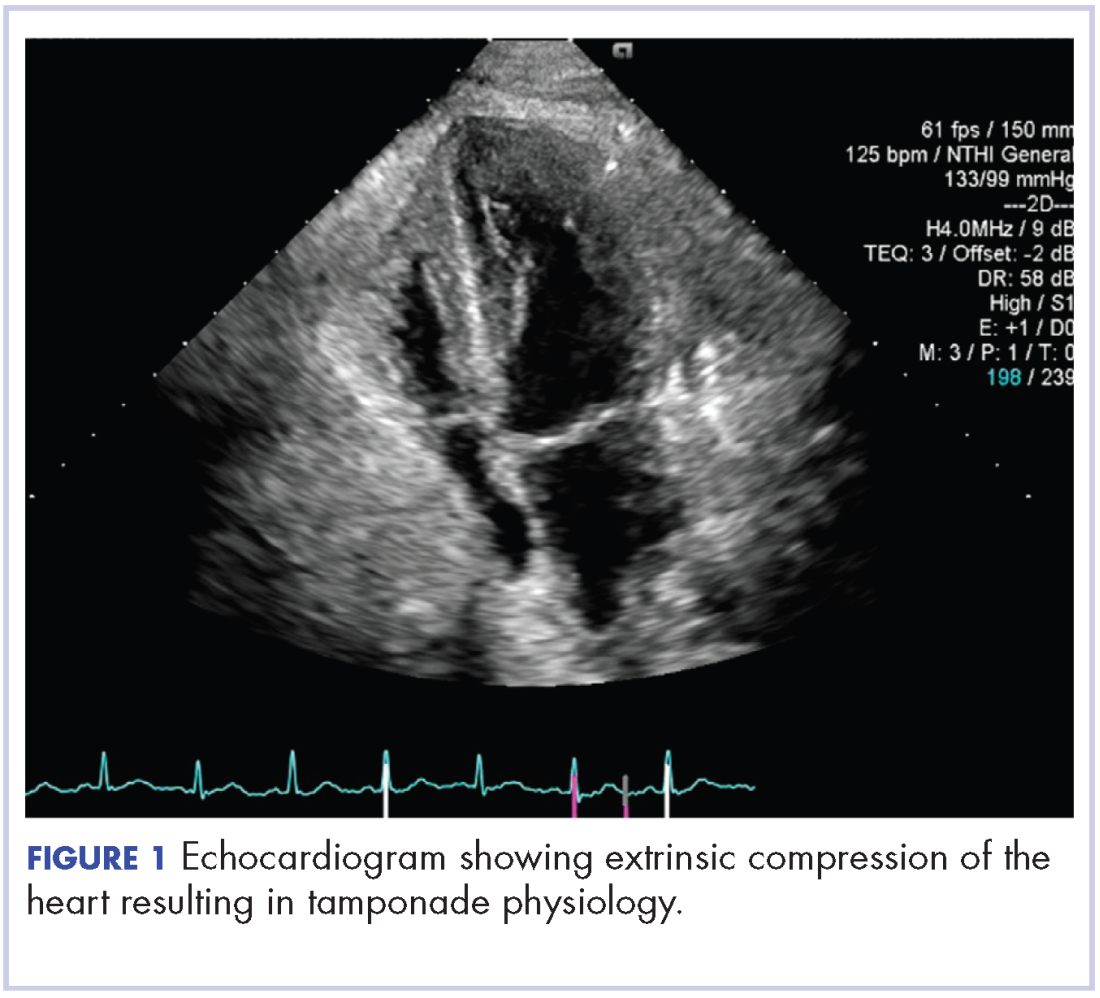

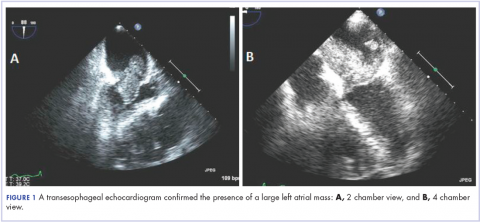

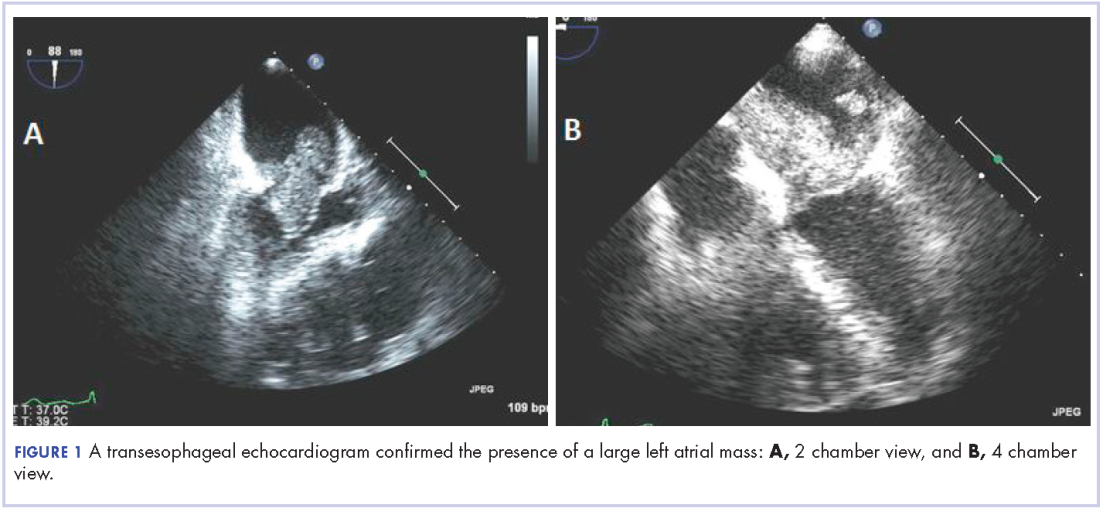

About 4 weeks after the surgery, the patient was seen at our institution for an initial consultation and was noted to have significant anasarca, including 4+ pitting lower extremity edema and scrotal edema. He complained of dyspnea on exertion, which he attributed to deconditioning. His resting heart rate was found to be 123 beats per minute (normal, 60-100 bpm). Jugular venous distention was present. The patient was sent for an urgent echocardiogram, which showed external compression of the right atrium and ventricle by his liver metastasis resulting in tamponade physiology without the presence of any pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

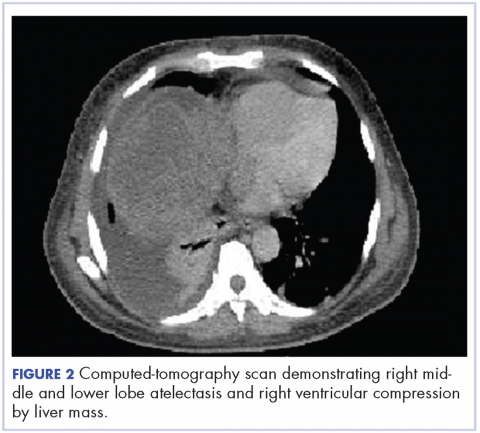

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis at that time showed that the liver mass had increased to 17.6 x 12.1 x 16.1 cm, exerting pressure on the heart and causing atelectasis of the right middle and lower lung lobes (Figure 2).

Treatment plan

The patient was evaluated by surgical oncology for resection, but his cardiovascular status placed him at high risk for perioperative complications, so such surgery was not pursued. Radioembolization was considered but not pursued because the process needed to evaluate, plan, and treat was not considered sufficiently timely. We consulted with our radiation oncology colleagues about external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for rapid palliation. They evaluated the patient and recommended the EBRT, and the patient signed consent for treatment. We performed a CT-based simulation and generated an external beam, linear-accelerator–based treatment plan. The plan consisted of three 15-megavoltage photon fields delivering 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions to the whole liver, with appropriate multileaf collimation blocking to minimize dose to adjacent heart, right lung, and bilateral kidneys (Figure 3).

Before initiation of the EBRT, the patient received systemic chemotherapy with a dose-adjusted FOLFOX regimen (5-FU bolus 200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, with infusional 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). After completing 1 dose of modified FOLFOX, he completed 10 fractions of whole liver radiotherapy with the aforementioned plan. He tolerated the initial treatment well and his subjective symptoms improved. The patient then proceeded to further systemic therapy. After recent data demonstrated improved median progression-free survival and response rates with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (infusional 5-FU 3200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, irinotecan 165 mg/m2, and oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg) versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab,3 we decided to modify his systemic therapy to FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab to induce a better response.

Treatment response

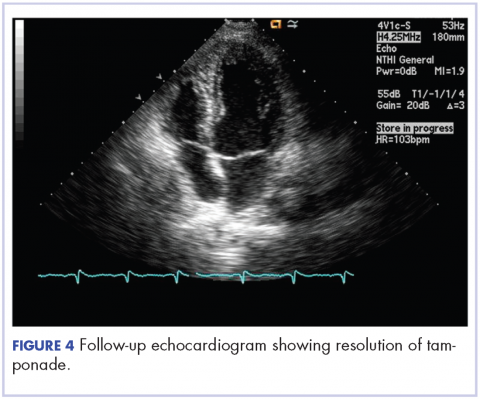

After 2 doses of chemotherapy and completion of radiotherapy, the edema and shortness of breath improved. A follow-up echocardiogram performed a month after completion of EBRT, 1 dose of FOLFOX, and 1 dose of FOLFOXIRI showed resolution of the cardiac compression (Figure 4).

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis obtained after 3 cycles of FOLFOXIRI showed marked decrease in the size of the right lobe hepatic mass from 17.6 x 12.1 cm to 12.0 x 8.0 cm. Given the survival benefit of VEGF inhibition in colon cancer, bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was added to the FOLFOXIRI regimen with cycle 4. Unfortunately, after the 5th cycle, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an increase in size of the hepatic lesions. At this time, FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab were stopped, and given the tumor’s KRAS/NRAS wild type status, systemic therapy was changed to panitumumab (6 mg/kg). The patient initially tolerated treatment well, but after 9 cycles, the total bilirubin started to increase. CT abdomen at this point was consistent with progression of disease. The patient was not eligible for a clinical trial targeting BRAF mutation given the elevated bilirubin. Regorafanib (80 mg daily for 3 weeks on and 1 week off) was started. After the first cycle, the total bilirubin increased further and the regorafanib was dose reduced to 40 mg daily. Unfortunately, a repeat CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated progression of disease, and given that he developed a progressive transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia, hospice care was recommended. The patient died shortly thereafter, about 15 months after his initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Massive liver metastasis in the setting of disseminated cancer is not an uncommon manifestation of advanced cancer that can have life-threatening consequences. In te present case, a bulky liver metastasis caused extrinsic compression of the right atrium, resulting in obvious clinical and echocardiogram-proven cardiac tamponade physiology. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of the treatment of a bulky hepatic metastasis causing cardiac tamponade. In this patient’s case, both radiotherapy and chemotherapy were given safely in rapid sequence resulting in quick resolution of the patient’s symptoms and echocardiogram findings. The presence of a BRAF mutation conferred a poor prognosis and poor response to systemic chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the patient showed good response to a FOLFOXIRI regimen, chosen in this emergent situation given its significantly higher response rates compared with the standard FOLFIRI regimen, which was tolerated well with minimal adverse effects.

Findings from randomized controlled trials examining the role of palliative radiotherapy for metastatic liver disease have suggested that dose escalation above 30 Gy to the whole liver may lead to unacceptably high rates of radiation-induced liver disease, which typically leads to mortality.4-8 Two prospective trials comparing twice daily with daily fractionation have shown no benefit to hyperfractionation, with possibly increased rates of acute toxicity in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma.9,10 There is emerging evidence that partial liver irradiation, in the appropriate setting in the form of boost after whole-liver RT or stereotactic body radiotherapy, may allow for further dose escalation while avoiding clinical hepatitis.11 Although there is no clear consensus about optimal RT dose and fractionation, the aforementioned studies show that dose and fractionation schemes ranging between 21 Gy and 30 Gy in 1.5 Gy to 3 Gy daily fractions likely provide the best therapeutic ratio for whole-liver irradiation.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the resolution of cardiac tamponade from a massive liver colorectal metastasis after chemoradiation and illustrates the potential utility of adding radiotherapy to chemotherapy in an urgent scenario where the former might not typically be considered.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2015.html. Published 2015. Accessed October 10, 2017.

2. Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104-117.

3. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1609-1618.

4. Russell AH, Clyde C, Wasserman TH, Turner SS, Rotman M. Accelerated hyperfractionated hepatic irradiation in the management of patients with liver metastases: results of the RTOG dose escalating protocol. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27(1):117-123.

5. Turek-Maischeider M, Kazem I. Palliative irradiation for liver metastases. JAMA. 1975;232(6):625-628.

6. Sherman DM, Weichselbaum R, Order SE, Cloud L, Trey C, Piro AJ. Palliation of hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1978;41(5):2013-2017.

7. Prasad B, Lee MS, Hendrickson FR. Irradiation of hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:129-132.

8. Borgelt BB, Gelber R, Brady LW, Griffin T, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of hepatic metastases: results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(5):587-591.

9. Raju PI, Maruyama Y, DeSimone P, MacDonald J. Treatment of liver metastases with a combination of chemotherapy and hyperfractionated external radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10(1):41-43.

10. Stillwagon GB, Order SE, Guse C, et al. 194 hepatocellular cancers treated by radiation and chemotherapy combinations: toxicity and response: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(6):1223-1229.

11. Mohiuddin M, Chen E, Ahmad N. Combined liver radiation and chemotherapy for palliation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):722-728.

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 About 5% of Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime, of which 20% will present with distant metastasis.2 The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum, and patients may present with signs or symptoms related to disease burden at any of these organs.

Case presentation and summary

A 55-year-old man had presented to an outside hospital in August of 2014 with 6 months of hematochezia and a 40-lb weight loss. He was found to be severely anemic on admission (hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL [normal, 13-17 g/dL], hematocrit, 16% [normal, 35%-45%]). A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a mass of 6.9 x 4.7 x 6.3 cm in the rectosigmoid colon and a mass of 10.0 x 12.0 x 10.7 cm in the right hepatic lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient was taken to the operating room where the rectosigmoid mass was resected completely. The liver mass was deemed unresectable because of its large size, and surgically directed therapy could not be performed. Pathology was consistent with a T3N1 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma 11 cm from the anal verge. Further molecular tumor studies revealed wild type KRAS and NRAS, as well as a BRAF mutation.

About 4 weeks after the surgery, the patient was seen at our institution for an initial consultation and was noted to have significant anasarca, including 4+ pitting lower extremity edema and scrotal edema. He complained of dyspnea on exertion, which he attributed to deconditioning. His resting heart rate was found to be 123 beats per minute (normal, 60-100 bpm). Jugular venous distention was present. The patient was sent for an urgent echocardiogram, which showed external compression of the right atrium and ventricle by his liver metastasis resulting in tamponade physiology without the presence of any pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis at that time showed that the liver mass had increased to 17.6 x 12.1 x 16.1 cm, exerting pressure on the heart and causing atelectasis of the right middle and lower lung lobes (Figure 2).

Treatment plan

The patient was evaluated by surgical oncology for resection, but his cardiovascular status placed him at high risk for perioperative complications, so such surgery was not pursued. Radioembolization was considered but not pursued because the process needed to evaluate, plan, and treat was not considered sufficiently timely. We consulted with our radiation oncology colleagues about external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for rapid palliation. They evaluated the patient and recommended the EBRT, and the patient signed consent for treatment. We performed a CT-based simulation and generated an external beam, linear-accelerator–based treatment plan. The plan consisted of three 15-megavoltage photon fields delivering 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions to the whole liver, with appropriate multileaf collimation blocking to minimize dose to adjacent heart, right lung, and bilateral kidneys (Figure 3).

Before initiation of the EBRT, the patient received systemic chemotherapy with a dose-adjusted FOLFOX regimen (5-FU bolus 200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, with infusional 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). After completing 1 dose of modified FOLFOX, he completed 10 fractions of whole liver radiotherapy with the aforementioned plan. He tolerated the initial treatment well and his subjective symptoms improved. The patient then proceeded to further systemic therapy. After recent data demonstrated improved median progression-free survival and response rates with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (infusional 5-FU 3200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, irinotecan 165 mg/m2, and oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg) versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab,3 we decided to modify his systemic therapy to FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab to induce a better response.

Treatment response

After 2 doses of chemotherapy and completion of radiotherapy, the edema and shortness of breath improved. A follow-up echocardiogram performed a month after completion of EBRT, 1 dose of FOLFOX, and 1 dose of FOLFOXIRI showed resolution of the cardiac compression (Figure 4).

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis obtained after 3 cycles of FOLFOXIRI showed marked decrease in the size of the right lobe hepatic mass from 17.6 x 12.1 cm to 12.0 x 8.0 cm. Given the survival benefit of VEGF inhibition in colon cancer, bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was added to the FOLFOXIRI regimen with cycle 4. Unfortunately, after the 5th cycle, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an increase in size of the hepatic lesions. At this time, FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab were stopped, and given the tumor’s KRAS/NRAS wild type status, systemic therapy was changed to panitumumab (6 mg/kg). The patient initially tolerated treatment well, but after 9 cycles, the total bilirubin started to increase. CT abdomen at this point was consistent with progression of disease. The patient was not eligible for a clinical trial targeting BRAF mutation given the elevated bilirubin. Regorafanib (80 mg daily for 3 weeks on and 1 week off) was started. After the first cycle, the total bilirubin increased further and the regorafanib was dose reduced to 40 mg daily. Unfortunately, a repeat CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated progression of disease, and given that he developed a progressive transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia, hospice care was recommended. The patient died shortly thereafter, about 15 months after his initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Massive liver metastasis in the setting of disseminated cancer is not an uncommon manifestation of advanced cancer that can have life-threatening consequences. In te present case, a bulky liver metastasis caused extrinsic compression of the right atrium, resulting in obvious clinical and echocardiogram-proven cardiac tamponade physiology. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of the treatment of a bulky hepatic metastasis causing cardiac tamponade. In this patient’s case, both radiotherapy and chemotherapy were given safely in rapid sequence resulting in quick resolution of the patient’s symptoms and echocardiogram findings. The presence of a BRAF mutation conferred a poor prognosis and poor response to systemic chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the patient showed good response to a FOLFOXIRI regimen, chosen in this emergent situation given its significantly higher response rates compared with the standard FOLFIRI regimen, which was tolerated well with minimal adverse effects.

Findings from randomized controlled trials examining the role of palliative radiotherapy for metastatic liver disease have suggested that dose escalation above 30 Gy to the whole liver may lead to unacceptably high rates of radiation-induced liver disease, which typically leads to mortality.4-8 Two prospective trials comparing twice daily with daily fractionation have shown no benefit to hyperfractionation, with possibly increased rates of acute toxicity in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma.9,10 There is emerging evidence that partial liver irradiation, in the appropriate setting in the form of boost after whole-liver RT or stereotactic body radiotherapy, may allow for further dose escalation while avoiding clinical hepatitis.11 Although there is no clear consensus about optimal RT dose and fractionation, the aforementioned studies show that dose and fractionation schemes ranging between 21 Gy and 30 Gy in 1.5 Gy to 3 Gy daily fractions likely provide the best therapeutic ratio for whole-liver irradiation.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the resolution of cardiac tamponade from a massive liver colorectal metastasis after chemoradiation and illustrates the potential utility of adding radiotherapy to chemotherapy in an urgent scenario where the former might not typically be considered.

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 About 5% of Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime, of which 20% will present with distant metastasis.2 The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum, and patients may present with signs or symptoms related to disease burden at any of these organs.

Case presentation and summary

A 55-year-old man had presented to an outside hospital in August of 2014 with 6 months of hematochezia and a 40-lb weight loss. He was found to be severely anemic on admission (hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL [normal, 13-17 g/dL], hematocrit, 16% [normal, 35%-45%]). A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a mass of 6.9 x 4.7 x 6.3 cm in the rectosigmoid colon and a mass of 10.0 x 12.0 x 10.7 cm in the right hepatic lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient was taken to the operating room where the rectosigmoid mass was resected completely. The liver mass was deemed unresectable because of its large size, and surgically directed therapy could not be performed. Pathology was consistent with a T3N1 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma 11 cm from the anal verge. Further molecular tumor studies revealed wild type KRAS and NRAS, as well as a BRAF mutation.

About 4 weeks after the surgery, the patient was seen at our institution for an initial consultation and was noted to have significant anasarca, including 4+ pitting lower extremity edema and scrotal edema. He complained of dyspnea on exertion, which he attributed to deconditioning. His resting heart rate was found to be 123 beats per minute (normal, 60-100 bpm). Jugular venous distention was present. The patient was sent for an urgent echocardiogram, which showed external compression of the right atrium and ventricle by his liver metastasis resulting in tamponade physiology without the presence of any pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis at that time showed that the liver mass had increased to 17.6 x 12.1 x 16.1 cm, exerting pressure on the heart and causing atelectasis of the right middle and lower lung lobes (Figure 2).

Treatment plan

The patient was evaluated by surgical oncology for resection, but his cardiovascular status placed him at high risk for perioperative complications, so such surgery was not pursued. Radioembolization was considered but not pursued because the process needed to evaluate, plan, and treat was not considered sufficiently timely. We consulted with our radiation oncology colleagues about external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for rapid palliation. They evaluated the patient and recommended the EBRT, and the patient signed consent for treatment. We performed a CT-based simulation and generated an external beam, linear-accelerator–based treatment plan. The plan consisted of three 15-megavoltage photon fields delivering 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions to the whole liver, with appropriate multileaf collimation blocking to minimize dose to adjacent heart, right lung, and bilateral kidneys (Figure 3).

Before initiation of the EBRT, the patient received systemic chemotherapy with a dose-adjusted FOLFOX regimen (5-FU bolus 200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, with infusional 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). After completing 1 dose of modified FOLFOX, he completed 10 fractions of whole liver radiotherapy with the aforementioned plan. He tolerated the initial treatment well and his subjective symptoms improved. The patient then proceeded to further systemic therapy. After recent data demonstrated improved median progression-free survival and response rates with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (infusional 5-FU 3200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, irinotecan 165 mg/m2, and oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg) versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab,3 we decided to modify his systemic therapy to FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab to induce a better response.

Treatment response

After 2 doses of chemotherapy and completion of radiotherapy, the edema and shortness of breath improved. A follow-up echocardiogram performed a month after completion of EBRT, 1 dose of FOLFOX, and 1 dose of FOLFOXIRI showed resolution of the cardiac compression (Figure 4).

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis obtained after 3 cycles of FOLFOXIRI showed marked decrease in the size of the right lobe hepatic mass from 17.6 x 12.1 cm to 12.0 x 8.0 cm. Given the survival benefit of VEGF inhibition in colon cancer, bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was added to the FOLFOXIRI regimen with cycle 4. Unfortunately, after the 5th cycle, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an increase in size of the hepatic lesions. At this time, FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab were stopped, and given the tumor’s KRAS/NRAS wild type status, systemic therapy was changed to panitumumab (6 mg/kg). The patient initially tolerated treatment well, but after 9 cycles, the total bilirubin started to increase. CT abdomen at this point was consistent with progression of disease. The patient was not eligible for a clinical trial targeting BRAF mutation given the elevated bilirubin. Regorafanib (80 mg daily for 3 weeks on and 1 week off) was started. After the first cycle, the total bilirubin increased further and the regorafanib was dose reduced to 40 mg daily. Unfortunately, a repeat CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated progression of disease, and given that he developed a progressive transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia, hospice care was recommended. The patient died shortly thereafter, about 15 months after his initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Massive liver metastasis in the setting of disseminated cancer is not an uncommon manifestation of advanced cancer that can have life-threatening consequences. In te present case, a bulky liver metastasis caused extrinsic compression of the right atrium, resulting in obvious clinical and echocardiogram-proven cardiac tamponade physiology. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of the treatment of a bulky hepatic metastasis causing cardiac tamponade. In this patient’s case, both radiotherapy and chemotherapy were given safely in rapid sequence resulting in quick resolution of the patient’s symptoms and echocardiogram findings. The presence of a BRAF mutation conferred a poor prognosis and poor response to systemic chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the patient showed good response to a FOLFOXIRI regimen, chosen in this emergent situation given its significantly higher response rates compared with the standard FOLFIRI regimen, which was tolerated well with minimal adverse effects.

Findings from randomized controlled trials examining the role of palliative radiotherapy for metastatic liver disease have suggested that dose escalation above 30 Gy to the whole liver may lead to unacceptably high rates of radiation-induced liver disease, which typically leads to mortality.4-8 Two prospective trials comparing twice daily with daily fractionation have shown no benefit to hyperfractionation, with possibly increased rates of acute toxicity in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma.9,10 There is emerging evidence that partial liver irradiation, in the appropriate setting in the form of boost after whole-liver RT or stereotactic body radiotherapy, may allow for further dose escalation while avoiding clinical hepatitis.11 Although there is no clear consensus about optimal RT dose and fractionation, the aforementioned studies show that dose and fractionation schemes ranging between 21 Gy and 30 Gy in 1.5 Gy to 3 Gy daily fractions likely provide the best therapeutic ratio for whole-liver irradiation.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the resolution of cardiac tamponade from a massive liver colorectal metastasis after chemoradiation and illustrates the potential utility of adding radiotherapy to chemotherapy in an urgent scenario where the former might not typically be considered.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2015.html. Published 2015. Accessed October 10, 2017.

2. Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104-117.

3. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1609-1618.

4. Russell AH, Clyde C, Wasserman TH, Turner SS, Rotman M. Accelerated hyperfractionated hepatic irradiation in the management of patients with liver metastases: results of the RTOG dose escalating protocol. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27(1):117-123.

5. Turek-Maischeider M, Kazem I. Palliative irradiation for liver metastases. JAMA. 1975;232(6):625-628.

6. Sherman DM, Weichselbaum R, Order SE, Cloud L, Trey C, Piro AJ. Palliation of hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1978;41(5):2013-2017.

7. Prasad B, Lee MS, Hendrickson FR. Irradiation of hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:129-132.

8. Borgelt BB, Gelber R, Brady LW, Griffin T, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of hepatic metastases: results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(5):587-591.

9. Raju PI, Maruyama Y, DeSimone P, MacDonald J. Treatment of liver metastases with a combination of chemotherapy and hyperfractionated external radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10(1):41-43.

10. Stillwagon GB, Order SE, Guse C, et al. 194 hepatocellular cancers treated by radiation and chemotherapy combinations: toxicity and response: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(6):1223-1229.

11. Mohiuddin M, Chen E, Ahmad N. Combined liver radiation and chemotherapy for palliation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):722-728.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2015.html. Published 2015. Accessed October 10, 2017.

2. Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104-117.

3. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1609-1618.

4. Russell AH, Clyde C, Wasserman TH, Turner SS, Rotman M. Accelerated hyperfractionated hepatic irradiation in the management of patients with liver metastases: results of the RTOG dose escalating protocol. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27(1):117-123.

5. Turek-Maischeider M, Kazem I. Palliative irradiation for liver metastases. JAMA. 1975;232(6):625-628.

6. Sherman DM, Weichselbaum R, Order SE, Cloud L, Trey C, Piro AJ. Palliation of hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1978;41(5):2013-2017.

7. Prasad B, Lee MS, Hendrickson FR. Irradiation of hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:129-132.

8. Borgelt BB, Gelber R, Brady LW, Griffin T, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of hepatic metastases: results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(5):587-591.

9. Raju PI, Maruyama Y, DeSimone P, MacDonald J. Treatment of liver metastases with a combination of chemotherapy and hyperfractionated external radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10(1):41-43.

10. Stillwagon GB, Order SE, Guse C, et al. 194 hepatocellular cancers treated by radiation and chemotherapy combinations: toxicity and response: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(6):1223-1229.

11. Mohiuddin M, Chen E, Ahmad N. Combined liver radiation and chemotherapy for palliation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):722-728.

Cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma after placement of Dacron graft

Primary cardiac tumors, either benign or malignant, are very rare. The combined incidence is 0.002% on pooled autopsy series.1 The benign tumors account for 63% of primary cardiac tumors and include myxoma, the most common, and followed by papillary fibroelastoma, fibroma, and hemangioma. The remaining 37% are malignant tumors, essentially predominated by sarcomas.1

Although myxoma is the most common tumor arising in the left atrium, we present a case that shows that sarcoma can also arise from the same chamber. In fact, sarcomas could mimic cardiac myxoma.2 The cardiac sarcomas can have similar clinical presentation and more importantly can share similar histopathological features. Sarcomas may have myxoid features.2 Cases diagnosed as cardiac myxomas should be diligently worked up to rule out the presence of sarcomas with myxoid features. In addition, foreign bodies have been found to induce sarcomas in experimental animals.3,4 In particular, 2 case reports have described sarcomas arising in association with Dacron vascular prostheses in humans.5,6 We present here the case of a patient who was diagnosed with cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma 8 years after the placement of a Dacron graft.

Case presentation and summary

A 56-year-old woman with history of left atrial myxoma status after resection in 2005 and placement of a Dacron graft, morbid obesity, hypertension, and asthma presented to the emergency department with progressively worsening shortness of breath and blurry vision over period of 2 months. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out by electrocardiogram and serial biomarkers. A computed-tomography angiogram was pursued because of her history of left atrial myxoma, and the results suggested the presence of a left atrial tumor. She underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram, which confirmed the presence of a large left atrial mass that likely was attached to the interatrial septum prolapsing across the mitral valve and was suggestive for recurrent left atrial myxoma (Figure 1). The results of a cardiac catheterization showed normal coronaries.

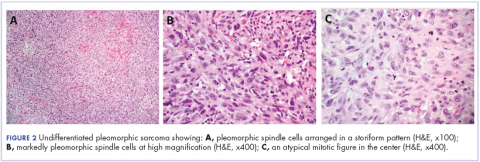

The patient subsequently underwent an excision of the left atrial tumor with profound internal and external myocardial cooling using antegrade blood cardioplegia under mildly hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. Frozen sections showed high-grade malignancy in favor of sarcoma. The hematoxylin and eosin stained permanent sections showed sheets of malignant pleomorphic spindle cells focally arranged in a storiform pattern. There were areas of necrosis and abundant mitotic activity. By immunohistochemical (IHC) stains, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin, and negative for pan-cytokeratin antibody (AE1/AE3), S-100 protein, Melan-A antibody, HMB45, CD34, CD31, myogenin, and MYOD1. IHC stains for CK-OSCAR, desmin, and smooth muscle actin were focally positive, and a ki-67 stain showed a proliferation index of about 80%. The histologic and IHC findings were consistent with a final diagnosis of high-grade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (Figure 2).

A positron emission tomography scan performed November 2013 did not show any other activity. The patient was scheduled for chemotherapy with adriamycin and ifosfamide with a plan for total of 6 cycles. Before her admission for the chemotherapy, the patient was admitted to the hospital for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and had multiple complications requiring prolonged hospitalization and rehabilitation. Repeat imaging 2 months later showed diffuse metastatic disease. However, her performance status had declined and she was not eligible for chemotherapy. She was placed under hospice care.

Discussion

This case demonstrates development of a cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma, a rare tumor, after placement of a Dacron graft. Given that foreign bodies have been found to induce sarcomas in experimental animals,3,4 and a few case reports have described sarcomas arising in association with Dacron vascular prostheses, 5-10 it seems that an exuberant host response around the foreign body might represent an important intermediate step in the development of the sarcoma.

There is no clearly defined pathogenesis that explains the link between a Dacron graft and sarcomas. In 1950s, Oppenheimer and colleagues described the formation of malignant tumors by various types of plastics, including Dacron, that were embedded in rats. 3,4 Most of the tumors were some form of sarcomas. It was inferred that physical properties of the plastics may have some role in tumor development. Plastics in sheet form or film that remained in situ for more than 6 months induced significant number of tumors compared with other forms such as sponges, films with holes, or powders.3,4 The 3-dimensional polymeric structure of the Dacron graft seems to play a role in induction of sarcoma as well. A pore diameter of less than 0.4 mm may increase tumorigenicity.11 The removal of the material before the 6-months mark does not lead to malignant tumors, which further supports the link between Dacron graft and formation of tumor. A pocket is formed around the foreign material after a certain period, as has been shown in histologic studies as the site of tumor origin.9,10

At the molecular level, the MDM-2/p53 pathway has been cited as possible mechanism for pathogenesis of intimal sarcoma.12,13 It has been suggested that endothelial dysplasia occurs as a precursor lesion in these sarcomas.14 The Dacron graft may cause a dysplastic effect on the endothelium leading to this precursor lesion and in certain cases transforming into sarcoma. Further definitive studies are required.

The primary treatment for cardiac sarcoma is surgical removal, although it is not always feasible. Findings in a Mayo clinic study showed that the median survival was 17 months for patients who underwent complete surgical excision, compared with 6 months for those who complete resection was not possible.15 In addition, a 10% survival rate at 1 year has been reported in primary cardiac sarcomas that are treated without any type of surgery.16

There is no clear-cut evidence supporting or refuting adjuvant chemotherapy for cardiac sarcoma. Some have inferred a potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn. The median survival was 16.5 months in a case series of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, compared with 9 months and 11 months in 2 other case series.17,18,19 Multiple chemotherapy regimens have been used in the past for treatment. A retrospective s

Radiation showed some benefit in progression-free survival in a French retrospective study.21 Radiation therapies have been tried in other cases, as well in addition to chemotherapy. However, there is not enough data to support or refute it at this time.15,17,20 Several sporadic cases reported show benefit of cardiac transplantation.21,22

Conclusion

In consideration of the placement of the Dacron graft 8 years before the tumor occurrence, the anatomic proximity of the tumor to the Dacron graft, and the association between sarcoma with Dacron in medical literature, it seems logical to infer that this unusual malignancy in our patient is associated with the Dacron prosthesis.

1. Patil HR, Singh D, Hajdu M. Cardiac sarcoma presenting as heart failure and diagnosed as recurrent myxoma by echocardiogram. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11(4):E12.

2. Awamleh P, Alberca MT, Gamallo C, Enrech S, Sarraj A. Left atrium myxosarcoma: an exceptional cardiac malignant primary tumor. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30(6):306-308.

3. Oppenheimer BS, Oppenheimer ET, Stout AP, Danishefsky I. Malignant tumors resulting from embedding plastics in rodents. Science. 1953;118:305-306.