User login

Call for Articles on Hematology/Oncology

Federal Practitioner articles are now available in PubMed Central, which provides full text access to any reader and is included in all PubMed online searches.

Federal Practitioner is inviting VA, DoD, and PHS health care providers and researchers to contribute to the May 2018 and August 2018 Advances in Hematology and Oncology special issues. The special issues are produced in cooperation with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO). The journal is especially interested in articles on lung, prostate, and head and neck cancers; melanoma and skin cancers; survivorship; patient navigation; lymphomas; leukemias; multiple myeloma; neuroendocrine tumors; and immunotherapies.

Interested authors can send a brief 2 to 3 sentence abstract to fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com by March 15, 2018, or submit a completed article directly into Editorial Manager, a web-based manuscript submission and review system. Federal Practitioner welcomes case studies, literature reviews, original research, program profiles, guest editorials, and other evidence-based articles. The updated and complete submission guidelines, including details about the style and format, can be found here:

http://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/submission-guidelines

All manuscripts submitted to Federal Practitioner for both special and regular issues will be subject to peer review. Peer reviews are conducted in a double-blind fashion, and the reviewers are asked to comment on the manuscript’s importance, accuracy, relevance, clarity, timeliness, balance, and reference citation. Final decisions on all submitted manuscripts are made by the Editorial Advisory Association Hematology/Oncology special issue advisory board.

Federal Practitioner articles are now available in PubMed Central, which provides full text access to any reader and is included in all PubMed online searches.

Federal Practitioner is inviting VA, DoD, and PHS health care providers and researchers to contribute to the May 2018 and August 2018 Advances in Hematology and Oncology special issues. The special issues are produced in cooperation with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO). The journal is especially interested in articles on lung, prostate, and head and neck cancers; melanoma and skin cancers; survivorship; patient navigation; lymphomas; leukemias; multiple myeloma; neuroendocrine tumors; and immunotherapies.

Interested authors can send a brief 2 to 3 sentence abstract to fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com by March 15, 2018, or submit a completed article directly into Editorial Manager, a web-based manuscript submission and review system. Federal Practitioner welcomes case studies, literature reviews, original research, program profiles, guest editorials, and other evidence-based articles. The updated and complete submission guidelines, including details about the style and format, can be found here:

http://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/submission-guidelines

All manuscripts submitted to Federal Practitioner for both special and regular issues will be subject to peer review. Peer reviews are conducted in a double-blind fashion, and the reviewers are asked to comment on the manuscript’s importance, accuracy, relevance, clarity, timeliness, balance, and reference citation. Final decisions on all submitted manuscripts are made by the Editorial Advisory Association Hematology/Oncology special issue advisory board.

Federal Practitioner articles are now available in PubMed Central, which provides full text access to any reader and is included in all PubMed online searches.

Federal Practitioner is inviting VA, DoD, and PHS health care providers and researchers to contribute to the May 2018 and August 2018 Advances in Hematology and Oncology special issues. The special issues are produced in cooperation with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO). The journal is especially interested in articles on lung, prostate, and head and neck cancers; melanoma and skin cancers; survivorship; patient navigation; lymphomas; leukemias; multiple myeloma; neuroendocrine tumors; and immunotherapies.

Interested authors can send a brief 2 to 3 sentence abstract to fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com by March 15, 2018, or submit a completed article directly into Editorial Manager, a web-based manuscript submission and review system. Federal Practitioner welcomes case studies, literature reviews, original research, program profiles, guest editorials, and other evidence-based articles. The updated and complete submission guidelines, including details about the style and format, can be found here:

http://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/submission-guidelines

All manuscripts submitted to Federal Practitioner for both special and regular issues will be subject to peer review. Peer reviews are conducted in a double-blind fashion, and the reviewers are asked to comment on the manuscript’s importance, accuracy, relevance, clarity, timeliness, balance, and reference citation. Final decisions on all submitted manuscripts are made by the Editorial Advisory Association Hematology/Oncology special issue advisory board.

Cognitive impairment in HSCT recipients

New research suggests the risk of cognitive impairment after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is greatest among recipients of myeloablative allogeneic (allo) HSCTs.

Compared to healthy controls, patients who received myeloablative allo-HSCT had a significantly higher risk of global cognitive deficit at a few time points after transplant.

There was a trend toward increased global cognitive deficit in recipients of allo-HSCT who had reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC), but there was no increased risk of global cognitive deficit in recipients of autologous (auto) HSCT.

Researchers reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“With this research from our longitudinal prospective assessment, we are able to deduce that a significant population of allogeneic [HSCT] survivors will experience cognitive impairment that can and will impact different aspects of their lives moving forward,” said study author Noha Sharafeldin, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“And it’s critical that we as clinicians develop interventions for these patients. This research is just the beginning of our figuring out how we can best care for [HSCT] survivors and enable them to live healthy lives.”

This study included 477 patients who underwent HSCT between 2004 and 2014. There were 236 auto-HSCTs, 128 RIC allo-HSCTs, and 113 myeloablative allo-HSCTs.

Patients underwent standardized neuropsychological testing before HSCT as well as at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years after transplant.

There were 429 patients who completed pre-HSCT testing (89.9%), 341 (81.6%) who underwent testing at 6 months after HSCT, 308 (81.5%) at 1 year, 247 (80.7%) at 2 years, and 227 (81.4%) at 3 years.

Testing was conducted on 8 cognitive domains—executive function, verbal fluency and speed, processing speed, working memory, visual and auditory memory, and fine motor dexterity.

The researchers conducted this testing in 99 healthy control subjects as well.

Before and after HSCT

Prior to HSCT, there were no significant differences in the cognitive domains tested between auto-HSCT recipients and controls or between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls.

Recipients of myeloablative allo-HSCT had significantly lower pre-HSCT scores for processing speed (P=0.001), as compared to controls.

After HSCT, there were no significant differences in overall scores between auto-HSCT recipients and controls or between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls.

However, recipients of myeloablative allo-HSCT had significantly lower scores than controls for executive function, verbal speed, processing speed, auditory memory, and fine motor dexterity (P≤0.003 for all).

Outcomes over time

For auto-HSCT recipients, there was a significant improvement from pre-HSCT to 6 months post-HSCT in verbal fluency (P<0.001). Meanwhile, there was a significant decrease in verbal processing and fine motor dexterity (P<0.001 for both).

At 3 years, auto-HSCT recipients had a significant increase in verbal fluency (P<0.001) but a significant decrease in visual memory (P=0.001) and fine motor dexterity (P<0.001).

For RIC allo-HSCT recipients, there was a significant decrease from pre-HSCT to 3 years post-HSCT in executive functioning (P=0.003), verbal fluency (P<0.001), and working memory (P<0.001). There were no significant differences between pre-HSCT and 6-month scores.

For patients who received myeloablative allo-HSCT, the only significant difference from pre-HSCT to 6 months or 3 years was a decrease in fine motor dexterity (P<0.001 for both time points).

Global cognitive deficit

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between auto-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (22.5% vs 17.2%; P=0.28) or at any time point after—6 months (26.1% vs 16.5%; P=0.07), 1 year (21.4% vs 19.5%; P=0.73), 2 years (21.1% vs 16.4%; P=0.43), and 3 years (18.7% vs 8.7%, P=0.11).

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (17.2% for both; P=1.0), at 6 months (22.0% vs 16.5%; P=0.35), 1 year (24.1% vs 19.5%; P=0.46), or 2 years (30.6% vs 16.4%; P=0.05) after HSCT.

However, the prevalence was significantly higher for RIC allo-HSCT recipients 3 years after HSCT (35.4% vs 8.7%; P=0.0012).

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between myeloablative allo-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (22.3% vs 17.2%; P=0.37) or at 1 year after (28.4% vs 19.5%; P=0.20).

However, the prevalence was significantly higher for myeloablative allo-HSCT recipients at 6 months (31.1% vs 16.5%; P=0.03), 2 years (34.6% vs 16.4%; P=0.02), and 3 years after HSCT (36.0% vs 8.7%; P=0.0015).

“From this data, it’s clear that we have to make strides in supporting allogeneic [HSCT] recipients in their recovery to ensure that we are educating patients and their families on signs of cognitive impairment,” Dr Sharafeldin said. “This data will help us identify patients at highest risk of cognitive impairment and inform the development of interventions that facilitate a patient’s recovery and return to normal life.”

New research suggests the risk of cognitive impairment after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is greatest among recipients of myeloablative allogeneic (allo) HSCTs.

Compared to healthy controls, patients who received myeloablative allo-HSCT had a significantly higher risk of global cognitive deficit at a few time points after transplant.

There was a trend toward increased global cognitive deficit in recipients of allo-HSCT who had reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC), but there was no increased risk of global cognitive deficit in recipients of autologous (auto) HSCT.

Researchers reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“With this research from our longitudinal prospective assessment, we are able to deduce that a significant population of allogeneic [HSCT] survivors will experience cognitive impairment that can and will impact different aspects of their lives moving forward,” said study author Noha Sharafeldin, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“And it’s critical that we as clinicians develop interventions for these patients. This research is just the beginning of our figuring out how we can best care for [HSCT] survivors and enable them to live healthy lives.”

This study included 477 patients who underwent HSCT between 2004 and 2014. There were 236 auto-HSCTs, 128 RIC allo-HSCTs, and 113 myeloablative allo-HSCTs.

Patients underwent standardized neuropsychological testing before HSCT as well as at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years after transplant.

There were 429 patients who completed pre-HSCT testing (89.9%), 341 (81.6%) who underwent testing at 6 months after HSCT, 308 (81.5%) at 1 year, 247 (80.7%) at 2 years, and 227 (81.4%) at 3 years.

Testing was conducted on 8 cognitive domains—executive function, verbal fluency and speed, processing speed, working memory, visual and auditory memory, and fine motor dexterity.

The researchers conducted this testing in 99 healthy control subjects as well.

Before and after HSCT

Prior to HSCT, there were no significant differences in the cognitive domains tested between auto-HSCT recipients and controls or between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls.

Recipients of myeloablative allo-HSCT had significantly lower pre-HSCT scores for processing speed (P=0.001), as compared to controls.

After HSCT, there were no significant differences in overall scores between auto-HSCT recipients and controls or between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls.

However, recipients of myeloablative allo-HSCT had significantly lower scores than controls for executive function, verbal speed, processing speed, auditory memory, and fine motor dexterity (P≤0.003 for all).

Outcomes over time

For auto-HSCT recipients, there was a significant improvement from pre-HSCT to 6 months post-HSCT in verbal fluency (P<0.001). Meanwhile, there was a significant decrease in verbal processing and fine motor dexterity (P<0.001 for both).

At 3 years, auto-HSCT recipients had a significant increase in verbal fluency (P<0.001) but a significant decrease in visual memory (P=0.001) and fine motor dexterity (P<0.001).

For RIC allo-HSCT recipients, there was a significant decrease from pre-HSCT to 3 years post-HSCT in executive functioning (P=0.003), verbal fluency (P<0.001), and working memory (P<0.001). There were no significant differences between pre-HSCT and 6-month scores.

For patients who received myeloablative allo-HSCT, the only significant difference from pre-HSCT to 6 months or 3 years was a decrease in fine motor dexterity (P<0.001 for both time points).

Global cognitive deficit

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between auto-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (22.5% vs 17.2%; P=0.28) or at any time point after—6 months (26.1% vs 16.5%; P=0.07), 1 year (21.4% vs 19.5%; P=0.73), 2 years (21.1% vs 16.4%; P=0.43), and 3 years (18.7% vs 8.7%, P=0.11).

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (17.2% for both; P=1.0), at 6 months (22.0% vs 16.5%; P=0.35), 1 year (24.1% vs 19.5%; P=0.46), or 2 years (30.6% vs 16.4%; P=0.05) after HSCT.

However, the prevalence was significantly higher for RIC allo-HSCT recipients 3 years after HSCT (35.4% vs 8.7%; P=0.0012).

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between myeloablative allo-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (22.3% vs 17.2%; P=0.37) or at 1 year after (28.4% vs 19.5%; P=0.20).

However, the prevalence was significantly higher for myeloablative allo-HSCT recipients at 6 months (31.1% vs 16.5%; P=0.03), 2 years (34.6% vs 16.4%; P=0.02), and 3 years after HSCT (36.0% vs 8.7%; P=0.0015).

“From this data, it’s clear that we have to make strides in supporting allogeneic [HSCT] recipients in their recovery to ensure that we are educating patients and their families on signs of cognitive impairment,” Dr Sharafeldin said. “This data will help us identify patients at highest risk of cognitive impairment and inform the development of interventions that facilitate a patient’s recovery and return to normal life.”

New research suggests the risk of cognitive impairment after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is greatest among recipients of myeloablative allogeneic (allo) HSCTs.

Compared to healthy controls, patients who received myeloablative allo-HSCT had a significantly higher risk of global cognitive deficit at a few time points after transplant.

There was a trend toward increased global cognitive deficit in recipients of allo-HSCT who had reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC), but there was no increased risk of global cognitive deficit in recipients of autologous (auto) HSCT.

Researchers reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“With this research from our longitudinal prospective assessment, we are able to deduce that a significant population of allogeneic [HSCT] survivors will experience cognitive impairment that can and will impact different aspects of their lives moving forward,” said study author Noha Sharafeldin, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“And it’s critical that we as clinicians develop interventions for these patients. This research is just the beginning of our figuring out how we can best care for [HSCT] survivors and enable them to live healthy lives.”

This study included 477 patients who underwent HSCT between 2004 and 2014. There were 236 auto-HSCTs, 128 RIC allo-HSCTs, and 113 myeloablative allo-HSCTs.

Patients underwent standardized neuropsychological testing before HSCT as well as at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years after transplant.

There were 429 patients who completed pre-HSCT testing (89.9%), 341 (81.6%) who underwent testing at 6 months after HSCT, 308 (81.5%) at 1 year, 247 (80.7%) at 2 years, and 227 (81.4%) at 3 years.

Testing was conducted on 8 cognitive domains—executive function, verbal fluency and speed, processing speed, working memory, visual and auditory memory, and fine motor dexterity.

The researchers conducted this testing in 99 healthy control subjects as well.

Before and after HSCT

Prior to HSCT, there were no significant differences in the cognitive domains tested between auto-HSCT recipients and controls or between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls.

Recipients of myeloablative allo-HSCT had significantly lower pre-HSCT scores for processing speed (P=0.001), as compared to controls.

After HSCT, there were no significant differences in overall scores between auto-HSCT recipients and controls or between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls.

However, recipients of myeloablative allo-HSCT had significantly lower scores than controls for executive function, verbal speed, processing speed, auditory memory, and fine motor dexterity (P≤0.003 for all).

Outcomes over time

For auto-HSCT recipients, there was a significant improvement from pre-HSCT to 6 months post-HSCT in verbal fluency (P<0.001). Meanwhile, there was a significant decrease in verbal processing and fine motor dexterity (P<0.001 for both).

At 3 years, auto-HSCT recipients had a significant increase in verbal fluency (P<0.001) but a significant decrease in visual memory (P=0.001) and fine motor dexterity (P<0.001).

For RIC allo-HSCT recipients, there was a significant decrease from pre-HSCT to 3 years post-HSCT in executive functioning (P=0.003), verbal fluency (P<0.001), and working memory (P<0.001). There were no significant differences between pre-HSCT and 6-month scores.

For patients who received myeloablative allo-HSCT, the only significant difference from pre-HSCT to 6 months or 3 years was a decrease in fine motor dexterity (P<0.001 for both time points).

Global cognitive deficit

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between auto-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (22.5% vs 17.2%; P=0.28) or at any time point after—6 months (26.1% vs 16.5%; P=0.07), 1 year (21.4% vs 19.5%; P=0.73), 2 years (21.1% vs 16.4%; P=0.43), and 3 years (18.7% vs 8.7%, P=0.11).

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between RIC allo-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (17.2% for both; P=1.0), at 6 months (22.0% vs 16.5%; P=0.35), 1 year (24.1% vs 19.5%; P=0.46), or 2 years (30.6% vs 16.4%; P=0.05) after HSCT.

However, the prevalence was significantly higher for RIC allo-HSCT recipients 3 years after HSCT (35.4% vs 8.7%; P=0.0012).

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of global cognitive deficit between myeloablative allo-HSCT recipients and controls before HSCT (22.3% vs 17.2%; P=0.37) or at 1 year after (28.4% vs 19.5%; P=0.20).

However, the prevalence was significantly higher for myeloablative allo-HSCT recipients at 6 months (31.1% vs 16.5%; P=0.03), 2 years (34.6% vs 16.4%; P=0.02), and 3 years after HSCT (36.0% vs 8.7%; P=0.0015).

“From this data, it’s clear that we have to make strides in supporting allogeneic [HSCT] recipients in their recovery to ensure that we are educating patients and their families on signs of cognitive impairment,” Dr Sharafeldin said. “This data will help us identify patients at highest risk of cognitive impairment and inform the development of interventions that facilitate a patient’s recovery and return to normal life.”

Gait freezing relieved by spinal cord, transcranial direct-current stimulation

The application of transcranial direct-current stimulation and spinal cord stimulation alleviated freezing of gait in two separate studies of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease published online in Movement Disorders.

In the first study, Moria Dagan of Tel Aviv University and her colleagues reported that transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) applied simultaneously to the primary motor cortex (M1) and the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) improved freezing of gait (FOG) more than M1 stimulation alone or sham stimulation in a double-blind, randomized trial of 20 patients. The second study, reported by Olivia Samotus and her associates at the London (Ont.) Health Sciences Centre, found that open-label, midthoracic epidural spinal cord stimulation (SCS) in five patients produced significantly reduced FOG episodes and also provided sustained improvement in gait measurements.

The tDCS study used a crossover design to show that, over the course of four separate, 20-minute tDCS sessions, FOG-provoking test scores improved in 15 of 17 patients who received multitarget stimulation and were significantly improved on average, whereas the scores of patients who had M1 stimulation alone or sham stimulation did not improve. Improvement in FOG severity nearly reached statistical significance when compared with M1 only and sham stimulation (P = .06). Three patients were unable to complete the FOG-provoking test and were excluded from the analysis.

The investigators tested simultaneous tDCS of the M1 and left DLPFC because a previous study showed improvement in FOG after M1 stimulation, and other evidence suggests that FOG might also arise through deficits in executive function mediated by the DLPFC. Previous research in other patient populations has also shown that tDCS improves cognition, gait, and postural control, and a prior study using transcranial magnetic stimulation of the M1 and left DLPFC improved gait and cognition in patients with FOG.

“We suggest that the results move this emerging approach a key step forward, as they support the idea that the cognitive executive circuit plays a role in FOG and the possibility that multitarget stimulation may have value as an intervention for ameliorating FOG,” Ms. Dagan and her colleagues wrote.

In a separate, nonrandomized pilot trial, SCS produced improvements in stride velocity, step length, and single- and double-support phases in follow-up visits out to 6 months post surgery, in addition to significantly decreasing FOG episodes. The study is the first to use objective gait technology to assess the efficacy of SCS for gait in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients. Ms. Samotus and her associates observed these changes after testing a range of pulse width and frequency combinations in each of the five participants to determine which settings best improved gait for each participant. Overall, the results suggest that pulse widths of “300-400 microseconds and frequencies of 30-130 Hz may be safe and possibly effective for reducing FOG frequency and improving gait dysfunction in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients.”

The tDCS trial was supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. One investigator disclosed that he is cofounder and shareholder of Neuroelectrics, which makes brain stimulation technologies such as the ones used in the study. No outside funding was reported for the SCS study. One investigator in the SCS study reported ties to pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers.

SOURCES: Dagan M et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/mds.27300; Samotus O et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 14. doi: 10.1002/mds.27299.

The application of transcranial direct-current stimulation and spinal cord stimulation alleviated freezing of gait in two separate studies of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease published online in Movement Disorders.

In the first study, Moria Dagan of Tel Aviv University and her colleagues reported that transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) applied simultaneously to the primary motor cortex (M1) and the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) improved freezing of gait (FOG) more than M1 stimulation alone or sham stimulation in a double-blind, randomized trial of 20 patients. The second study, reported by Olivia Samotus and her associates at the London (Ont.) Health Sciences Centre, found that open-label, midthoracic epidural spinal cord stimulation (SCS) in five patients produced significantly reduced FOG episodes and also provided sustained improvement in gait measurements.

The tDCS study used a crossover design to show that, over the course of four separate, 20-minute tDCS sessions, FOG-provoking test scores improved in 15 of 17 patients who received multitarget stimulation and were significantly improved on average, whereas the scores of patients who had M1 stimulation alone or sham stimulation did not improve. Improvement in FOG severity nearly reached statistical significance when compared with M1 only and sham stimulation (P = .06). Three patients were unable to complete the FOG-provoking test and were excluded from the analysis.

The investigators tested simultaneous tDCS of the M1 and left DLPFC because a previous study showed improvement in FOG after M1 stimulation, and other evidence suggests that FOG might also arise through deficits in executive function mediated by the DLPFC. Previous research in other patient populations has also shown that tDCS improves cognition, gait, and postural control, and a prior study using transcranial magnetic stimulation of the M1 and left DLPFC improved gait and cognition in patients with FOG.

“We suggest that the results move this emerging approach a key step forward, as they support the idea that the cognitive executive circuit plays a role in FOG and the possibility that multitarget stimulation may have value as an intervention for ameliorating FOG,” Ms. Dagan and her colleagues wrote.

In a separate, nonrandomized pilot trial, SCS produced improvements in stride velocity, step length, and single- and double-support phases in follow-up visits out to 6 months post surgery, in addition to significantly decreasing FOG episodes. The study is the first to use objective gait technology to assess the efficacy of SCS for gait in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients. Ms. Samotus and her associates observed these changes after testing a range of pulse width and frequency combinations in each of the five participants to determine which settings best improved gait for each participant. Overall, the results suggest that pulse widths of “300-400 microseconds and frequencies of 30-130 Hz may be safe and possibly effective for reducing FOG frequency and improving gait dysfunction in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients.”

The tDCS trial was supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. One investigator disclosed that he is cofounder and shareholder of Neuroelectrics, which makes brain stimulation technologies such as the ones used in the study. No outside funding was reported for the SCS study. One investigator in the SCS study reported ties to pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers.

SOURCES: Dagan M et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/mds.27300; Samotus O et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 14. doi: 10.1002/mds.27299.

The application of transcranial direct-current stimulation and spinal cord stimulation alleviated freezing of gait in two separate studies of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease published online in Movement Disorders.

In the first study, Moria Dagan of Tel Aviv University and her colleagues reported that transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) applied simultaneously to the primary motor cortex (M1) and the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) improved freezing of gait (FOG) more than M1 stimulation alone or sham stimulation in a double-blind, randomized trial of 20 patients. The second study, reported by Olivia Samotus and her associates at the London (Ont.) Health Sciences Centre, found that open-label, midthoracic epidural spinal cord stimulation (SCS) in five patients produced significantly reduced FOG episodes and also provided sustained improvement in gait measurements.

The tDCS study used a crossover design to show that, over the course of four separate, 20-minute tDCS sessions, FOG-provoking test scores improved in 15 of 17 patients who received multitarget stimulation and were significantly improved on average, whereas the scores of patients who had M1 stimulation alone or sham stimulation did not improve. Improvement in FOG severity nearly reached statistical significance when compared with M1 only and sham stimulation (P = .06). Three patients were unable to complete the FOG-provoking test and were excluded from the analysis.

The investigators tested simultaneous tDCS of the M1 and left DLPFC because a previous study showed improvement in FOG after M1 stimulation, and other evidence suggests that FOG might also arise through deficits in executive function mediated by the DLPFC. Previous research in other patient populations has also shown that tDCS improves cognition, gait, and postural control, and a prior study using transcranial magnetic stimulation of the M1 and left DLPFC improved gait and cognition in patients with FOG.

“We suggest that the results move this emerging approach a key step forward, as they support the idea that the cognitive executive circuit plays a role in FOG and the possibility that multitarget stimulation may have value as an intervention for ameliorating FOG,” Ms. Dagan and her colleagues wrote.

In a separate, nonrandomized pilot trial, SCS produced improvements in stride velocity, step length, and single- and double-support phases in follow-up visits out to 6 months post surgery, in addition to significantly decreasing FOG episodes. The study is the first to use objective gait technology to assess the efficacy of SCS for gait in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients. Ms. Samotus and her associates observed these changes after testing a range of pulse width and frequency combinations in each of the five participants to determine which settings best improved gait for each participant. Overall, the results suggest that pulse widths of “300-400 microseconds and frequencies of 30-130 Hz may be safe and possibly effective for reducing FOG frequency and improving gait dysfunction in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients.”

The tDCS trial was supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. One investigator disclosed that he is cofounder and shareholder of Neuroelectrics, which makes brain stimulation technologies such as the ones used in the study. No outside funding was reported for the SCS study. One investigator in the SCS study reported ties to pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers.

SOURCES: Dagan M et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/mds.27300; Samotus O et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 14. doi: 10.1002/mds.27299.

FROM MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Freezing of gait–provoking test scores improved in 15 of 17 patients who received simultaneous tDCS to the primary motor cortex and the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Study details: A double-blind, randomized trial of tDCS in 20 Parkinson’s disease patients and a nonrandomized, open-label study of spinal cord stimulation in 5 Parkinson’s patients.

Disclosures: The tDCS trial was supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. One investigator disclosed that he is cofounder and shareholder of Neuroelectrics, which makes brain stimulation technologies such as the ones used in the study. No outside funding was reported for the SCS study. One investigator in the SCS study reported ties to pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers.

Sources: Dagan M et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/mds.27300; Samotus O et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Feb 14. doi: 10.1002/mds.27299.

Trump administration proposes rule to loosen curbs on short-term health plans

Insurers will again be able to sell short-term health insurance good for up to 12 months under a proposed rule released Feb. 20 by the Trump administration that could further roil the marketplace.

“We want to open up affordable alternatives to unaffordable Affordable Care Act policies,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. “This is one step in the direction of providing Americans health insurance options that are more affordable and more suitable to individual and family circumstances.”

The proposed rule said short-term plans could add more choices to the market at lower cost and may offer broader provider networks than Affordable Care Act plans in rural areas.

But most short-term coverage requires answering a string of medical questions, and insurers can reject applicants with preexisting medical problems, which ACA plans cannot do. As a result, the proposed rule also noted that some people who switch to them from ACA coverage may see “reduced access to some services,” and “increased out of pocket costs, possibly leading to financial hardship.”

The directive follows an executive order issued in October to roll back restrictions put in place during the Obama administration that limited these plans to 3 months. The rule comes on the heels of Congress’ approval of tax legislation that in 2019 will end the penalty for people who opt not to carry insurance coverage.

The administration also issued separate regulations Jan. 4 that would make it easier to form “association health plans,” which are offered to small businesses through membership organizations.

Together, the proposed regulations and the elimination of the so-called individual mandate by Congress could further undermine the Affordable Care Act marketplace, critics say.

Seema Verma, who now heads the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which oversees the marketplaces, told reporters Feb. 20 that federal officials believe that between 100,000 and 200,000 “healthy people” now buying insurance through those federal exchanges would switch to the short-term plans, as well as others who are now uninsured.

The new rule is expected to entice younger and healthier people from the general insurance pool by allowing a range of lower-cost options that don’t include all the benefits required by the federal law – including plans that can reject people with preexisting medical conditions. Most short-term coverage excludes benefits for maternity care, preventive care, mental health services, or substance abuse treatment.

“It’s deeply concerning to me, considering the tragedy in Florida and national opioid crisis, that the administration would be encouraging the sale of policies that don’t have to cover mental health and substance abuse,” said Kevin Lucia, a research professor and project director at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

Over time, those remaining in ACA plans will increasingly be those who qualify for premium tax credit subsidies and the sick, who can’t get an alternative like a short-term plan, predict Mr. Lucia and other experts. That, in turn, would drive up ACA premiums further.

“If consumers think Obamacare premiums are high today, wait until people flood into these short-term and association health plans,” said industry consultant Robert Laszewski. “The Trump administration will bring rates down substantially for healthy people, but woe unto those who get a condition and have to go back into Obamacare.”

If 100,000-200,000 people shift from ACA-compliant plans in 2019, this would cause “average monthly individual market premiums … to increase,” the proposed rule states. That, in turn, would cause subsidies for eligible policyholders in the ACA market to rise, costing the government $96 million–$168 million.

Supporters said the rules are needed because the ACA plans have already become too costly for people who don’t receive a government subsidy to help them purchase the coverage. “The current system is failing too many,” said Ms. Verma.

And, many supporters don’t think the change is as significant as skeptics fear.

“It simply reverts back to where the short-term plan rules were prior to Obama limiting those plans,” said Christopher Condeluci, a benefits attorney who also served as tax counsel to the U.S. Senate Finance Committee. “While these plans might not be the best answer, people do need a choice, and this new proposal provides needed choice to a certain subsection of the population.”

But, in their call with reporters, CMS officials said the proposed rule seeks comment on whether there are ways to guarantee renewability of the plans, which currently cannot be renewed. Instead, policyholders must reapply and answer medical questions again. The proposal also seeks comments on whether the plans should be allowed for longer than 12-month periods.

The comment period for the proposed rule runs for 60 days. Ms. Verma said CMS hopes to get final rules out “as quickly as possible,” so insurers could start offering the longer duration plans.

Short-term plans had been designed as temporary coverage, lasting for a few months while, for instance, a worker is between jobs and employer-sponsored insurances. They provide some protection to those who enroll, generally paying a percentage of hospital and doctor bills after the policyholder meets a deductible.

They are generally less expensive than ACA plans, because they cover less. For example, they set annual and lifetime caps on benefits, and few cover prescription drugs.

Most require applicants to pass a medical questionnaire – and they can also exclude coverage for preexisting medical conditions.

The plans are appealing to consumers because they are cheaper than Obamacare plans. They are also attractive to brokers, because they often pay higher commissions than ACA plans. Insurers like them because their profit margins are relatively high – and are not held to the ACA requirement that they spend at least 80 percent of premium revenue on plan members’ medical care.

Extending short-term plans to a full year could be a benefit to consumers because they must pass the health questionnaire only once. Still, if a consumer develops a health condition during the contract’s term, that person would likely be rejected if he or she tried to renew.

Both supporters and critics of short-term plans say consumers who do develop health problems could then sign up for an ACA plan during the next open enrollment because the ACA bars insurers from rejecting people with preexisting conditions.

“We’re going to have two different markets, a Wild West frontier called short-term medical … and a high-risk pool called Obamacare,” said Laszewski.

KHN senior correspondent Phil Galewitz contributed to this article. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Insurers will again be able to sell short-term health insurance good for up to 12 months under a proposed rule released Feb. 20 by the Trump administration that could further roil the marketplace.

“We want to open up affordable alternatives to unaffordable Affordable Care Act policies,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. “This is one step in the direction of providing Americans health insurance options that are more affordable and more suitable to individual and family circumstances.”

The proposed rule said short-term plans could add more choices to the market at lower cost and may offer broader provider networks than Affordable Care Act plans in rural areas.

But most short-term coverage requires answering a string of medical questions, and insurers can reject applicants with preexisting medical problems, which ACA plans cannot do. As a result, the proposed rule also noted that some people who switch to them from ACA coverage may see “reduced access to some services,” and “increased out of pocket costs, possibly leading to financial hardship.”

The directive follows an executive order issued in October to roll back restrictions put in place during the Obama administration that limited these plans to 3 months. The rule comes on the heels of Congress’ approval of tax legislation that in 2019 will end the penalty for people who opt not to carry insurance coverage.

The administration also issued separate regulations Jan. 4 that would make it easier to form “association health plans,” which are offered to small businesses through membership organizations.

Together, the proposed regulations and the elimination of the so-called individual mandate by Congress could further undermine the Affordable Care Act marketplace, critics say.

Seema Verma, who now heads the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which oversees the marketplaces, told reporters Feb. 20 that federal officials believe that between 100,000 and 200,000 “healthy people” now buying insurance through those federal exchanges would switch to the short-term plans, as well as others who are now uninsured.

The new rule is expected to entice younger and healthier people from the general insurance pool by allowing a range of lower-cost options that don’t include all the benefits required by the federal law – including plans that can reject people with preexisting medical conditions. Most short-term coverage excludes benefits for maternity care, preventive care, mental health services, or substance abuse treatment.

“It’s deeply concerning to me, considering the tragedy in Florida and national opioid crisis, that the administration would be encouraging the sale of policies that don’t have to cover mental health and substance abuse,” said Kevin Lucia, a research professor and project director at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

Over time, those remaining in ACA plans will increasingly be those who qualify for premium tax credit subsidies and the sick, who can’t get an alternative like a short-term plan, predict Mr. Lucia and other experts. That, in turn, would drive up ACA premiums further.

“If consumers think Obamacare premiums are high today, wait until people flood into these short-term and association health plans,” said industry consultant Robert Laszewski. “The Trump administration will bring rates down substantially for healthy people, but woe unto those who get a condition and have to go back into Obamacare.”

If 100,000-200,000 people shift from ACA-compliant plans in 2019, this would cause “average monthly individual market premiums … to increase,” the proposed rule states. That, in turn, would cause subsidies for eligible policyholders in the ACA market to rise, costing the government $96 million–$168 million.

Supporters said the rules are needed because the ACA plans have already become too costly for people who don’t receive a government subsidy to help them purchase the coverage. “The current system is failing too many,” said Ms. Verma.

And, many supporters don’t think the change is as significant as skeptics fear.

“It simply reverts back to where the short-term plan rules were prior to Obama limiting those plans,” said Christopher Condeluci, a benefits attorney who also served as tax counsel to the U.S. Senate Finance Committee. “While these plans might not be the best answer, people do need a choice, and this new proposal provides needed choice to a certain subsection of the population.”

But, in their call with reporters, CMS officials said the proposed rule seeks comment on whether there are ways to guarantee renewability of the plans, which currently cannot be renewed. Instead, policyholders must reapply and answer medical questions again. The proposal also seeks comments on whether the plans should be allowed for longer than 12-month periods.

The comment period for the proposed rule runs for 60 days. Ms. Verma said CMS hopes to get final rules out “as quickly as possible,” so insurers could start offering the longer duration plans.

Short-term plans had been designed as temporary coverage, lasting for a few months while, for instance, a worker is between jobs and employer-sponsored insurances. They provide some protection to those who enroll, generally paying a percentage of hospital and doctor bills after the policyholder meets a deductible.

They are generally less expensive than ACA plans, because they cover less. For example, they set annual and lifetime caps on benefits, and few cover prescription drugs.

Most require applicants to pass a medical questionnaire – and they can also exclude coverage for preexisting medical conditions.

The plans are appealing to consumers because they are cheaper than Obamacare plans. They are also attractive to brokers, because they often pay higher commissions than ACA plans. Insurers like them because their profit margins are relatively high – and are not held to the ACA requirement that they spend at least 80 percent of premium revenue on plan members’ medical care.

Extending short-term plans to a full year could be a benefit to consumers because they must pass the health questionnaire only once. Still, if a consumer develops a health condition during the contract’s term, that person would likely be rejected if he or she tried to renew.

Both supporters and critics of short-term plans say consumers who do develop health problems could then sign up for an ACA plan during the next open enrollment because the ACA bars insurers from rejecting people with preexisting conditions.

“We’re going to have two different markets, a Wild West frontier called short-term medical … and a high-risk pool called Obamacare,” said Laszewski.

KHN senior correspondent Phil Galewitz contributed to this article. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Insurers will again be able to sell short-term health insurance good for up to 12 months under a proposed rule released Feb. 20 by the Trump administration that could further roil the marketplace.

“We want to open up affordable alternatives to unaffordable Affordable Care Act policies,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. “This is one step in the direction of providing Americans health insurance options that are more affordable and more suitable to individual and family circumstances.”

The proposed rule said short-term plans could add more choices to the market at lower cost and may offer broader provider networks than Affordable Care Act plans in rural areas.

But most short-term coverage requires answering a string of medical questions, and insurers can reject applicants with preexisting medical problems, which ACA plans cannot do. As a result, the proposed rule also noted that some people who switch to them from ACA coverage may see “reduced access to some services,” and “increased out of pocket costs, possibly leading to financial hardship.”

The directive follows an executive order issued in October to roll back restrictions put in place during the Obama administration that limited these plans to 3 months. The rule comes on the heels of Congress’ approval of tax legislation that in 2019 will end the penalty for people who opt not to carry insurance coverage.

The administration also issued separate regulations Jan. 4 that would make it easier to form “association health plans,” which are offered to small businesses through membership organizations.

Together, the proposed regulations and the elimination of the so-called individual mandate by Congress could further undermine the Affordable Care Act marketplace, critics say.

Seema Verma, who now heads the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which oversees the marketplaces, told reporters Feb. 20 that federal officials believe that between 100,000 and 200,000 “healthy people” now buying insurance through those federal exchanges would switch to the short-term plans, as well as others who are now uninsured.

The new rule is expected to entice younger and healthier people from the general insurance pool by allowing a range of lower-cost options that don’t include all the benefits required by the federal law – including plans that can reject people with preexisting medical conditions. Most short-term coverage excludes benefits for maternity care, preventive care, mental health services, or substance abuse treatment.

“It’s deeply concerning to me, considering the tragedy in Florida and national opioid crisis, that the administration would be encouraging the sale of policies that don’t have to cover mental health and substance abuse,” said Kevin Lucia, a research professor and project director at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

Over time, those remaining in ACA plans will increasingly be those who qualify for premium tax credit subsidies and the sick, who can’t get an alternative like a short-term plan, predict Mr. Lucia and other experts. That, in turn, would drive up ACA premiums further.

“If consumers think Obamacare premiums are high today, wait until people flood into these short-term and association health plans,” said industry consultant Robert Laszewski. “The Trump administration will bring rates down substantially for healthy people, but woe unto those who get a condition and have to go back into Obamacare.”

If 100,000-200,000 people shift from ACA-compliant plans in 2019, this would cause “average monthly individual market premiums … to increase,” the proposed rule states. That, in turn, would cause subsidies for eligible policyholders in the ACA market to rise, costing the government $96 million–$168 million.

Supporters said the rules are needed because the ACA plans have already become too costly for people who don’t receive a government subsidy to help them purchase the coverage. “The current system is failing too many,” said Ms. Verma.

And, many supporters don’t think the change is as significant as skeptics fear.

“It simply reverts back to where the short-term plan rules were prior to Obama limiting those plans,” said Christopher Condeluci, a benefits attorney who also served as tax counsel to the U.S. Senate Finance Committee. “While these plans might not be the best answer, people do need a choice, and this new proposal provides needed choice to a certain subsection of the population.”

But, in their call with reporters, CMS officials said the proposed rule seeks comment on whether there are ways to guarantee renewability of the plans, which currently cannot be renewed. Instead, policyholders must reapply and answer medical questions again. The proposal also seeks comments on whether the plans should be allowed for longer than 12-month periods.

The comment period for the proposed rule runs for 60 days. Ms. Verma said CMS hopes to get final rules out “as quickly as possible,” so insurers could start offering the longer duration plans.

Short-term plans had been designed as temporary coverage, lasting for a few months while, for instance, a worker is between jobs and employer-sponsored insurances. They provide some protection to those who enroll, generally paying a percentage of hospital and doctor bills after the policyholder meets a deductible.

They are generally less expensive than ACA plans, because they cover less. For example, they set annual and lifetime caps on benefits, and few cover prescription drugs.

Most require applicants to pass a medical questionnaire – and they can also exclude coverage for preexisting medical conditions.

The plans are appealing to consumers because they are cheaper than Obamacare plans. They are also attractive to brokers, because they often pay higher commissions than ACA plans. Insurers like them because their profit margins are relatively high – and are not held to the ACA requirement that they spend at least 80 percent of premium revenue on plan members’ medical care.

Extending short-term plans to a full year could be a benefit to consumers because they must pass the health questionnaire only once. Still, if a consumer develops a health condition during the contract’s term, that person would likely be rejected if he or she tried to renew.

Both supporters and critics of short-term plans say consumers who do develop health problems could then sign up for an ACA plan during the next open enrollment because the ACA bars insurers from rejecting people with preexisting conditions.

“We’re going to have two different markets, a Wild West frontier called short-term medical … and a high-risk pool called Obamacare,” said Laszewski.

KHN senior correspondent Phil Galewitz contributed to this article. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Gut-homing protein predicts HIV-acquisition, disease progression in women

Higher frequency of alpha4beta7 expression in the CD4 T cells in the gut was associated with increased HIV acquisition and severity, according to the results of a retrospective comparative analysis of blood samples from patients in the CAPRISA 004 study.

Researchers compared samples from patients who eventually developed HIV with samples from those who did not; they also assessed human study cohorts from Kenya and the RV254/Search 010 cohort in Thailand, according to an online report in Science Translational Medicine. In addition, they obtained data from nonhuman primates (NHPs) challenged with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) to compare results between primate species.

They found that alpha4beta7+ CD4+ T cells were depleted very early in HIV infection, particularly in the gut, and the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) was unable to restore the normal levels of those cells even when provided at the earliest time point. Citing the literature, the researchers speculated that interactions between alpha4beta7 and the HIV env protein may assist the virus in locating its ideal target cells, and that high levels of alpha4beta7+ CD4+ T cells were associated with preferential infection by HIV-1 types containing motifs associated with higher alpha4beta7 binding, which are overrepresented in the region where the CAPRISA004 study was conducted.

“Although the association of alpha4beta7 and HIV expression was relatively modest, results were consistent in independent cohorts in two different countries and in NHPs,” according to Aida Sivro, PhD, of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research and her colleagues on behalf of the CAPRISA004 and RS254 study groups.

NHP studies showed some promise in this regard because, while ART alone did not lead to immune restoration of these T cells, “ART in combination with anti-alpha4beta7 did so in NHPs,” the researchers concluded, suggesting the possibility of additional therapeutic interventions in humans.

The authors reported having no disclosures. The CAPRISA 004 study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the South African Department of Science and Technology.

SOURCE: Sivro A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Jan 24;10(425):eaam6354.

Higher frequency of alpha4beta7 expression in the CD4 T cells in the gut was associated with increased HIV acquisition and severity, according to the results of a retrospective comparative analysis of blood samples from patients in the CAPRISA 004 study.

Researchers compared samples from patients who eventually developed HIV with samples from those who did not; they also assessed human study cohorts from Kenya and the RV254/Search 010 cohort in Thailand, according to an online report in Science Translational Medicine. In addition, they obtained data from nonhuman primates (NHPs) challenged with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) to compare results between primate species.

They found that alpha4beta7+ CD4+ T cells were depleted very early in HIV infection, particularly in the gut, and the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) was unable to restore the normal levels of those cells even when provided at the earliest time point. Citing the literature, the researchers speculated that interactions between alpha4beta7 and the HIV env protein may assist the virus in locating its ideal target cells, and that high levels of alpha4beta7+ CD4+ T cells were associated with preferential infection by HIV-1 types containing motifs associated with higher alpha4beta7 binding, which are overrepresented in the region where the CAPRISA004 study was conducted.

“Although the association of alpha4beta7 and HIV expression was relatively modest, results were consistent in independent cohorts in two different countries and in NHPs,” according to Aida Sivro, PhD, of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research and her colleagues on behalf of the CAPRISA004 and RS254 study groups.

NHP studies showed some promise in this regard because, while ART alone did not lead to immune restoration of these T cells, “ART in combination with anti-alpha4beta7 did so in NHPs,” the researchers concluded, suggesting the possibility of additional therapeutic interventions in humans.

The authors reported having no disclosures. The CAPRISA 004 study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the South African Department of Science and Technology.

SOURCE: Sivro A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Jan 24;10(425):eaam6354.

Higher frequency of alpha4beta7 expression in the CD4 T cells in the gut was associated with increased HIV acquisition and severity, according to the results of a retrospective comparative analysis of blood samples from patients in the CAPRISA 004 study.

Researchers compared samples from patients who eventually developed HIV with samples from those who did not; they also assessed human study cohorts from Kenya and the RV254/Search 010 cohort in Thailand, according to an online report in Science Translational Medicine. In addition, they obtained data from nonhuman primates (NHPs) challenged with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) to compare results between primate species.

They found that alpha4beta7+ CD4+ T cells were depleted very early in HIV infection, particularly in the gut, and the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) was unable to restore the normal levels of those cells even when provided at the earliest time point. Citing the literature, the researchers speculated that interactions between alpha4beta7 and the HIV env protein may assist the virus in locating its ideal target cells, and that high levels of alpha4beta7+ CD4+ T cells were associated with preferential infection by HIV-1 types containing motifs associated with higher alpha4beta7 binding, which are overrepresented in the region where the CAPRISA004 study was conducted.

“Although the association of alpha4beta7 and HIV expression was relatively modest, results were consistent in independent cohorts in two different countries and in NHPs,” according to Aida Sivro, PhD, of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research and her colleagues on behalf of the CAPRISA004 and RS254 study groups.

NHP studies showed some promise in this regard because, while ART alone did not lead to immune restoration of these T cells, “ART in combination with anti-alpha4beta7 did so in NHPs,” the researchers concluded, suggesting the possibility of additional therapeutic interventions in humans.

The authors reported having no disclosures. The CAPRISA 004 study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the South African Department of Science and Technology.

SOURCE: Sivro A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Jan 24;10(425):eaam6354.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: CD4+ T cells expressing the protein were rapidly depleted very early in HIV infection.

Major finding: HIV outcomes and alpha4beta7 expression appear linked.

Study details: Blood samples analyzed from the CAPRISA 004 study comparing HIV-infected patients and controls.

Disclosures: The CAPRISA 004 study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the South African Department of Science and Technology.

Source: Sivro A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Jan 24;10(425):eaam6354.

Making social media work for your practice

Social media use is ubiquitous and, in the digital age, it is the ascendant form of communication. Individuals and organizations, digital immigrants (those born before the widespread adoption of digital technology), and digital natives alike are leveraging social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn, to curate, consume, and share information across the spectrum of demographics and target audiences. In the United States, 7 in 10 Americans are using social media and, although young adults were early adopters, use among older adults is increasing rapidly.1

Furthermore, social media has cultivated remarkable opportunities in the dissemination of health information and disrupted traditional methods of patient–provider communication. The days when medically trained health professionals were the gatekeepers of health information are long gone. Approximately 50% of Americans seek health information online before seeing a physician.2 Patients and other consumers regularly access social media to search for information about diseases and treatments, engage with other patients, identify providers, and to express or rate their satisfaction with providers, clinics, and health systems.3-5 In addition, they trust online health information from doctors more than that from hospitals, health insurers, and drug companies.6 Not surprisingly, this has led to tremendous growth in use of social media by health care providers, hospitals, and health centers. More than 90% of US hospitals have a Facebook page and 50% have a Twitter account.7

There is ample opportunity to close the gap between patient and health care provider engagement in Social media, equip providers with the tools they need to be competent consumers and sharers of information in this digital exchange, and increase the pool of evidence-based information on GI and liver diseases on social media.12 However, there is limited published literature tailored to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. The goal of this article, therefore, is to provide a broad overview of best practices in the professional use of social media and highlight examples of novel applications in clinical practice.

Best practices: Getting started and maintaining a presence on social media

Social media can magnify your professional image, amplify your voice, and extend your reach and influence much faster than other methods. It also can be damaging if not used responsibly. Thus, we recommend the following approaches to responsible use of social media and cultivating your social media presence based on current evidence, professional organizations’ policy statements, and our combined experience. We initially presented these strategies during a Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Disease Week® in Chicago (http://www.ddw.org/education/session-recordings).

Second, as with other aspects of medical training and practice, find a mentor to provide hands-on advice. This is particularly true if your general familiarity with the social media platforms is limited. If this is not available through your network of colleagues or workplace, we recommend exploring opportunities offered through your professional organization(s) such as the aforementioned Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Diseases Week.

Third, know the privacy setting options on your social media platform(s) of choice and use them to your advantage. For example, on Facebook and Twitter, you can select an option that requests your permission before a friend or follower is added to your network. You also can tailor who (such as friends or followers only) can access your posted content directly. However, know that your content still may be made public if it is shared by one of your friends or followers.

Fourth, nurture your social media presence by sharing credible content deliberately, regularly, and, when appropriate, with attribution.

Fifth, diversify your content within the realm of your predefined objectives and/or goals and avoid a singular focus of self-promotion or the appearance of self-promotion. Top social media users suggest, and the authors agree, that your content should be only 25%-33% of your posts.

Sixth, thoroughly vet all content that you share. Avoid automatically sharing articles or posts because of a catchy headline. Read them before you post them. There may be details buried in them that are not credible or with which you do not agree.

Seventh, build community by connecting and engaging with other users on your social media platform(s) of choice.

Eighth, integrate multiple media (i.e., photos, videos, infographics) and/or social media platforms (i.e., embed link to YouTube or a website) to increase engagement.

Ninth, adhere to the code of ethics, governance, and privacy of the profession and of your employer.

Best practices: Privacy and governance in patient-oriented communication on social media

Two factors that have been of pivotal concern with the adoption of social media in the health care arena and led to many health care professionals being laggards as opposed to early adopters are privacy and governance. Will it violate the patient–provider relationship? What about the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act? How do I maintain boundaries between myself and the public at large? These are just a few of the questions that commonly are asked by those who are unfamiliar with social media etiquette for health care professionals. We highly recommend reviewing the position paper regarding online medical professionalism issued by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards as a starting point.13 We believe the following to be contemporary guiding principles for GI health providers for maintaining a digital footprint on social media that reflects the ethical and professional standards of the field.

First, avoid sharing information that could be construed as a patient identifier without documented consent. This includes, but is not limited to, an identifiable specimen or photograph, and stories of care, rare conditions, and complications. Note that dates and location of care can lead to identification of a patient or care episode.

Second, recognize that personal and professional online profiles/pages are discoverable. Many advocate for separating the two as a means of shielding the public from elements of a private persona (i.e., family pictures and controversial opinions). However, the capacity to share and find comments and images on social media is much more powerful than the privacy settings on the various social media platforms. If you establish distinct personal and professional profiles, exercise caution before accepting friend or follow requests from patients on your personal profile. In addition, be cautious with your posts on private social media accounts because they rarely truly are private.

Third, avoid providing specific medical recommendations to individuals. This creates a patient–provider relationship and legal duty. Instead, recommend consultation with a health care provider and consider providing a link to general information on the topic (e.g., AGA information for patients at www.gastro.org/patientinfo).

Fourth, declare conflicts of interest, if applicable, when sharing information involving your clinical, research, and/or business practice.

Fifth, routinely monitor your online presence for accuracy and appropriateness of content posted by you and by others in reference to you. Know that our profession’s ethical standards for behavior extend to social media and we can be held accountable to colleagues and our employer if we violate them.

Many employers have become savvy to issues of governance in use of social media and institute policy recommendations to which employees are expected to adhere. If you are an employee, we recommend checking with your marketing and/or human resources department(s) in regards to this. If you are an employer and do not have such a policy on online professionalism, it is our hope that this article serves as a launching pad.

Novel applications for social media in clinical practice

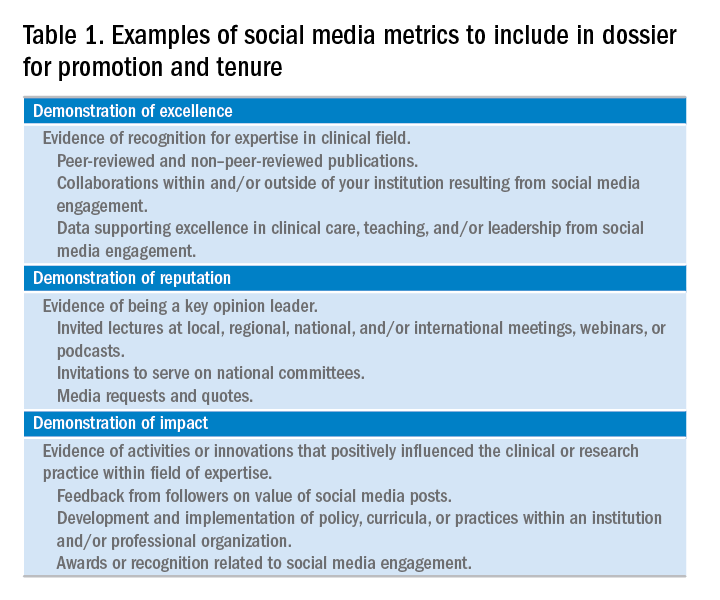

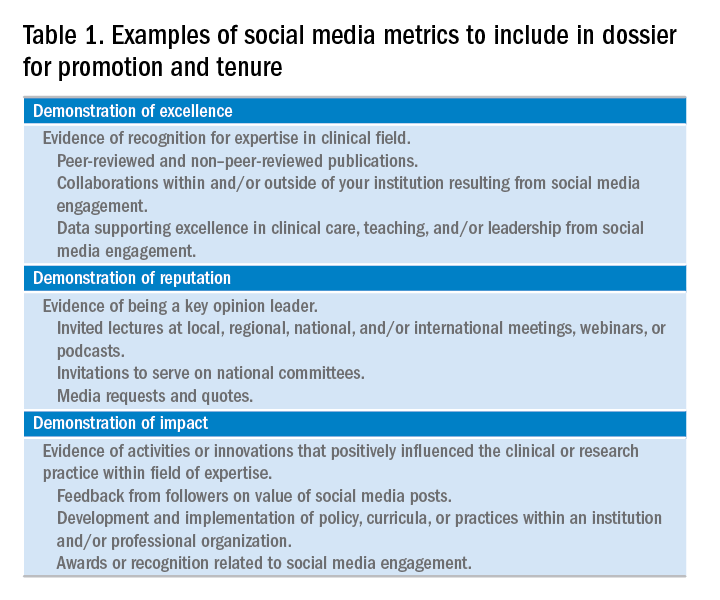

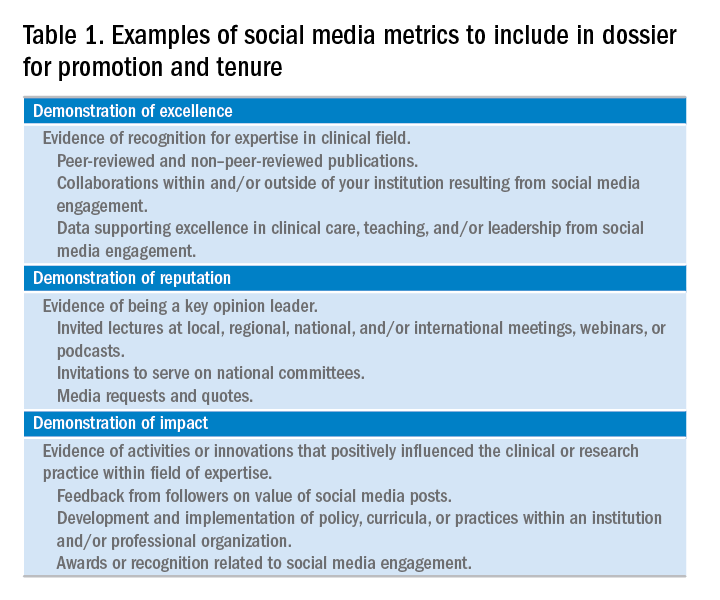

Social media has been shown to be an effective medium for medical education through virtual journal clubs, moderated discussions or chats, and video sharing for teaching procedures, to name a few applications. Social media is used to collect data via polls or surveys, and to disseminate and track the views and downloads of published works. It is also a source for unsolicited, real-time feedback on patient experience and engagement through data-mining techniques, such as natural language processing and, more simply, for solicited feedback for patient satisfaction ratings. However, its role in academic promotion is less clear and is an area for which we see a great opportunity for growth.

Summary

We have outlined a high-level overview for why you should consider establishing and maintaining a professional presence on social media and how to accomplish this. These reasons include sharing information with colleagues, patients, and the public; amplifying the voice of physicians, a view that has diminished in the often-volatile health care environment; and promotion of the value of your work, be it patient care, advocacy, research, or education. You will have a smoother experience if you learn your local rules and policies and abide by our suggestions to avoid adverse outcomes. You will be most effective if you establish goals for your social media participation and revisit these goals over time for continued relevance and success and if you have consistent and valuable output that will support attainment of these goals. Welcome to the GI social media community! Be sure to follow Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the American Gastroenterological Association on Facebook (facebook.com/cghjournal and facebook.com/amergastroassn) and Twitter (@AGA_CGH and @AmerGastroAssn), and the coauthors (@DMGrayMD and @DrDeborahFisher) on Twitter.

References

1. Social Media Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center [updated January 12, 2017]. Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

2. Hesse B.W., Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2618-24.

3. Moorhead S.A., Hazlett D.E., Harrison L., et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85.

4. Chou W.Y., Hunt Y.M., Beckjord E.B. et al. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e48.

5. Chretien K.C., Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;27:1413-21.

6. Social Media ‘likes’ Healthcare. PwC Health Research Institute; 2012. Available from https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/publications/pdf/health-care-social-media-report.pdf. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

7. Griffis H.M., Kilaru A.S., Werner R.M., et al. Use of social media across US hospitals: descriptive analysis of adoption and utilization. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e264.

8. Davis E.D., Tang S.J., Glover P.H., et al. Impact of social media on gastroenterologists in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:258-9.

9. Chiang A.L., Vartabedian B., Spiegel B. Harnessing the hashtag: a standard approach to GI dialogue on social media. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1082-4.

10. Reich J., Guo L., Hall J., et al. A survey of social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2678-87.

11. Timms C., Forton D.M., Poullis A. Social media use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and chronic viral hepatitis. Clin Med. 2014;14:215.

12. Prasad B. Social media, health care, and social networking. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:492-5.

13. Farnan J.M., Snyder Sulmasy L., Worster B.K., et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:620-7.

14. Cabrera D., Vartabedian B.S., Spinner R.J., et al. More than likes and tweets: creating social media portfolios for academic promotion and tenure. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:421-5.

15. Cabrera D. Mayo Clinic includes social media scholarship activities in academic advancement. Available from https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/2016/05/25/mayo-clinic-includes-social-media-scholarship-activities-in-academic-advancement/

Date: May 26, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

16. Freitag C.E., Arnold M.A., Gardner J.M., et al. If you are not on social media, here’s what you’re missing! #DoTheThing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; (Epub ahead of print).

17. Stukus D.R. How I used twitter to get promoted in academic medicine. Available from http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2016/10/used-twitter-get-promoted-academic-medicine.html. Date: October 9, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

Dr. Gray is in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus; Dr. Fisher is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Social media use is ubiquitous and, in the digital age, it is the ascendant form of communication. Individuals and organizations, digital immigrants (those born before the widespread adoption of digital technology), and digital natives alike are leveraging social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn, to curate, consume, and share information across the spectrum of demographics and target audiences. In the United States, 7 in 10 Americans are using social media and, although young adults were early adopters, use among older adults is increasing rapidly.1

Furthermore, social media has cultivated remarkable opportunities in the dissemination of health information and disrupted traditional methods of patient–provider communication. The days when medically trained health professionals were the gatekeepers of health information are long gone. Approximately 50% of Americans seek health information online before seeing a physician.2 Patients and other consumers regularly access social media to search for information about diseases and treatments, engage with other patients, identify providers, and to express or rate their satisfaction with providers, clinics, and health systems.3-5 In addition, they trust online health information from doctors more than that from hospitals, health insurers, and drug companies.6 Not surprisingly, this has led to tremendous growth in use of social media by health care providers, hospitals, and health centers. More than 90% of US hospitals have a Facebook page and 50% have a Twitter account.7

There is ample opportunity to close the gap between patient and health care provider engagement in Social media, equip providers with the tools they need to be competent consumers and sharers of information in this digital exchange, and increase the pool of evidence-based information on GI and liver diseases on social media.12 However, there is limited published literature tailored to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. The goal of this article, therefore, is to provide a broad overview of best practices in the professional use of social media and highlight examples of novel applications in clinical practice.

Best practices: Getting started and maintaining a presence on social media

Social media can magnify your professional image, amplify your voice, and extend your reach and influence much faster than other methods. It also can be damaging if not used responsibly. Thus, we recommend the following approaches to responsible use of social media and cultivating your social media presence based on current evidence, professional organizations’ policy statements, and our combined experience. We initially presented these strategies during a Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Disease Week® in Chicago (http://www.ddw.org/education/session-recordings).

Second, as with other aspects of medical training and practice, find a mentor to provide hands-on advice. This is particularly true if your general familiarity with the social media platforms is limited. If this is not available through your network of colleagues or workplace, we recommend exploring opportunities offered through your professional organization(s) such as the aforementioned Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Diseases Week.