User login

Revised McDonald Criteria Allow Substitution for Dissemination in Time

PARIS—Recommended revisions to the 2010 McDonald diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) include changes that are intended to enable neurologists to diagnose MS sooner in patients with a high likelihood of the disease. One addition allows the use of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands in lieu of demonstration of dissemination in time to make a diagnosis of MS in patients with a clinically isolated syndrome and demonstration of dissemination in space clinically or by MRI. Symptomatic and cortical lesions also may satisfy diagnostic criteria, according to the recommendations. In addition, the revised criteria include guidance to reduce the risk of misdiagnosing MS.

Jeffrey A. Cohen, MD, a neurologist with the Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, presented the 2017 proposed revisions at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

Dr. Cohen and Alan J. Thompson, MD, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, cochaired the International Panel on Diagnosis of MS, which drafted the new recommendations. The panel convened in November 2016 and May 2017. The meetings were organized under the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in MS and supported by the US National MS Society and the European Committee for Treatment and Research in MS (ECTRIMS). The panel’s recommendations have been submitted for publication and are in the late stages of revision, Dr. Cohen said.

Facilitate Diagnosis

New data regarding the utility of MRI, CSF, and other tests in the diagnostic process motivated neurologists to reconvene the panel. In addition, “there has been increasing recognition of the continued frequency and potential consequences of misdiagnosis of MS,” Dr. Cohen said.

“We felt that the 2010 McDonald criteria overall performed well,” he said. “We did not anticipate making major changes to the criteria. But we sought to simplify and clarify some of the components of the 2010 criteria. We wanted to facilitate the ability to make the diagnosis of MS in patients who had a high likelihood of the disease but were not currently diagnosable by the 2010 criteria. We wanted to preserve the specificity of the 2010 criteria but promote their appropriate application … to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis.” Finally, the panel “wanted to ensure that any proposed changes did not weaken the existing criteria and were supported by reasonable evidence,” he said. Dr. Cohen highlighted five of the panel’s key revisions.

Recommended Changes

First and probably most controversially, “we propose that in a patient with a typical clinically isolated syndrome, and with fulfillment by either clinical or MRI criteria for dissemination in space, that the presence of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands now allows for diagnosis of MS,” Dr. Cohen said. “It does not represent demonstration of dissemination in time per se, but it allows substitution for demonstration of dissemination in time.”

A second recommendation is that symptomatic and asymptomatic MRI lesions can be considered in the determination of dissemination in space and time. In the 2010 criteria, a symptomatic lesion in a patient with a brainstem or spinal cord syndrome could not be included as MRI evidence of dissemination in time and space.

Third, in addition to juxtacortical lesions, cortical lesions can demonstrate dissemination in space. Neurologists’ ability to detect purely cortical MRI

Fourth, the criteria for primary progressive MS now allow the inclusion of symptomatic and cortical lesions as evidence of the disease. These criteria otherwise have not changed.

Finally, the panel recommends that neurologists determine a provisional disease course, as specified by Lublin et al, at the time of diagnosis and then periodically reevaluate the provisional course based on accumulated evidence.

Avoiding Misdiagnosis

“Much of our discussion started with the issue of misdiagnosis and differential diagnosis in MS,” Dr. Cohen said. “The potential differential diagnosis of MS is quite broad, and misdiagnosis remains an issue even today with advancements in MRI and other testing.” Solomon et al found that neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSDs) were the disorders most commonly misdiagnosed as MS. Physicians also misdiagnosed common conditions like migraine as MS. “Misdiagnosis may have harmful consequences, including inappropriate institution of disease therapy,” Dr. Cohen said.

Neurologists now recognize that aquaporin 4–related NMOSD is a distinct disorder from MS. “However, if you think back to the time that the 2010 criteria were developed, the relationship between NMOSD and MS was not quite as clear. Substantial data have been published since that time,” Dr. Cohen said. “We agreed that the McDonald criteria and the formal criteria for NMOSD largely distinguish the two diseases. However, there may be cases in which there is some uncertainty. Our recommendation is that … the possibility of NMOSD should be considered in all patients being evaluated for MS,” and any patient with features suggesting NMOSD should undergo aquaporin 4 testing.

In general, neurologists should recognize that the McDonald criteria originally were developed to make the diagnosis of MS in patients who have a high likelihood of the disease, not to differentiate MS from other disorders, he said. “Historical events being taken to represent a prior attack should be interpreted with caution if there is no corroborating objective evidence,” Dr. Cohen said. “In cases in which the diagnosis of MS is uncertain, further testing should be pursued. And in some cases, a clinician may want to postpone making a diagnosis pending the accumulation of sufficient data.” CSF testing and spinal MRI are not required to make the diagnosis of MS, but there should be a low threshold for obtaining them.

While data generally support the validity of the 2010 McDonald criteria in geographically diverse populations, children, and older individuals, neurologists should address potentially relevant alternative diagnoses that may be more common in these and other populations (eg, patients with comorbidities), such as infections and nutritional deficiencies.

MAGNIMS Proposal

Several proposals generated discussion during the panel meetings but were not adopted, primarily because the evidence did not justify changing the current criteria. For instance, the 2016 MAGNIMS MRI criteria propose that the number of acquired periventricular lesions be increased from one to three to provide additional specificity. “We reviewed those data … and felt that the modest increase in specificity did not justify making the change,” Dr. Cohen said. The panel also discussed incorporating optic nerve involvement into the criteria, but this proposal was not included in the update.

“The 2017 revisions further refine the well-established McDonald criteria,” Dr. Cohen said. “The appropriate application of the criteria is critical to avoid misdiagnosis. Fundamentally, MS remains a clinical diagnosis. … It requires rigorous synthesis of clinical, imaging, and laboratory data by a clinician with expertise in MS.”

Making a Diagnosis Sooner

Neurologists have been diagnosing MS in patients sooner. At the same time, misdiagnosing other conditions as MS can have profound consequences, including the potentially serious side effects of disease-modifying therapy, said Jeremy Chataway, PhD, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, in a lecture about the application of the proposed criteria. He described cases in which the 2017 proposed criteria—by allowing the inclusion of a symptomatic spinal cord lesion, or by substituting CSF-specific oligoclonal bands in place of dissemination in time—would have allowed neurologists to diagnose MS sooner. In one case, a patient might have received a diagnosis of MS about two years earlier.

Sometimes a diagnosis of MS “is obvious,” Dr. Chataway said. “Sometimes it is hard, even with advanced MRI. You can see the gradation that is required … to get us to the correct diagnosis.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292-302.

Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: A multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

PARIS—Recommended revisions to the 2010 McDonald diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) include changes that are intended to enable neurologists to diagnose MS sooner in patients with a high likelihood of the disease. One addition allows the use of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands in lieu of demonstration of dissemination in time to make a diagnosis of MS in patients with a clinically isolated syndrome and demonstration of dissemination in space clinically or by MRI. Symptomatic and cortical lesions also may satisfy diagnostic criteria, according to the recommendations. In addition, the revised criteria include guidance to reduce the risk of misdiagnosing MS.

Jeffrey A. Cohen, MD, a neurologist with the Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, presented the 2017 proposed revisions at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

Dr. Cohen and Alan J. Thompson, MD, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, cochaired the International Panel on Diagnosis of MS, which drafted the new recommendations. The panel convened in November 2016 and May 2017. The meetings were organized under the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in MS and supported by the US National MS Society and the European Committee for Treatment and Research in MS (ECTRIMS). The panel’s recommendations have been submitted for publication and are in the late stages of revision, Dr. Cohen said.

Facilitate Diagnosis

New data regarding the utility of MRI, CSF, and other tests in the diagnostic process motivated neurologists to reconvene the panel. In addition, “there has been increasing recognition of the continued frequency and potential consequences of misdiagnosis of MS,” Dr. Cohen said.

“We felt that the 2010 McDonald criteria overall performed well,” he said. “We did not anticipate making major changes to the criteria. But we sought to simplify and clarify some of the components of the 2010 criteria. We wanted to facilitate the ability to make the diagnosis of MS in patients who had a high likelihood of the disease but were not currently diagnosable by the 2010 criteria. We wanted to preserve the specificity of the 2010 criteria but promote their appropriate application … to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis.” Finally, the panel “wanted to ensure that any proposed changes did not weaken the existing criteria and were supported by reasonable evidence,” he said. Dr. Cohen highlighted five of the panel’s key revisions.

Recommended Changes

First and probably most controversially, “we propose that in a patient with a typical clinically isolated syndrome, and with fulfillment by either clinical or MRI criteria for dissemination in space, that the presence of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands now allows for diagnosis of MS,” Dr. Cohen said. “It does not represent demonstration of dissemination in time per se, but it allows substitution for demonstration of dissemination in time.”

A second recommendation is that symptomatic and asymptomatic MRI lesions can be considered in the determination of dissemination in space and time. In the 2010 criteria, a symptomatic lesion in a patient with a brainstem or spinal cord syndrome could not be included as MRI evidence of dissemination in time and space.

Third, in addition to juxtacortical lesions, cortical lesions can demonstrate dissemination in space. Neurologists’ ability to detect purely cortical MRI

Fourth, the criteria for primary progressive MS now allow the inclusion of symptomatic and cortical lesions as evidence of the disease. These criteria otherwise have not changed.

Finally, the panel recommends that neurologists determine a provisional disease course, as specified by Lublin et al, at the time of diagnosis and then periodically reevaluate the provisional course based on accumulated evidence.

Avoiding Misdiagnosis

“Much of our discussion started with the issue of misdiagnosis and differential diagnosis in MS,” Dr. Cohen said. “The potential differential diagnosis of MS is quite broad, and misdiagnosis remains an issue even today with advancements in MRI and other testing.” Solomon et al found that neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSDs) were the disorders most commonly misdiagnosed as MS. Physicians also misdiagnosed common conditions like migraine as MS. “Misdiagnosis may have harmful consequences, including inappropriate institution of disease therapy,” Dr. Cohen said.

Neurologists now recognize that aquaporin 4–related NMOSD is a distinct disorder from MS. “However, if you think back to the time that the 2010 criteria were developed, the relationship between NMOSD and MS was not quite as clear. Substantial data have been published since that time,” Dr. Cohen said. “We agreed that the McDonald criteria and the formal criteria for NMOSD largely distinguish the two diseases. However, there may be cases in which there is some uncertainty. Our recommendation is that … the possibility of NMOSD should be considered in all patients being evaluated for MS,” and any patient with features suggesting NMOSD should undergo aquaporin 4 testing.

In general, neurologists should recognize that the McDonald criteria originally were developed to make the diagnosis of MS in patients who have a high likelihood of the disease, not to differentiate MS from other disorders, he said. “Historical events being taken to represent a prior attack should be interpreted with caution if there is no corroborating objective evidence,” Dr. Cohen said. “In cases in which the diagnosis of MS is uncertain, further testing should be pursued. And in some cases, a clinician may want to postpone making a diagnosis pending the accumulation of sufficient data.” CSF testing and spinal MRI are not required to make the diagnosis of MS, but there should be a low threshold for obtaining them.

While data generally support the validity of the 2010 McDonald criteria in geographically diverse populations, children, and older individuals, neurologists should address potentially relevant alternative diagnoses that may be more common in these and other populations (eg, patients with comorbidities), such as infections and nutritional deficiencies.

MAGNIMS Proposal

Several proposals generated discussion during the panel meetings but were not adopted, primarily because the evidence did not justify changing the current criteria. For instance, the 2016 MAGNIMS MRI criteria propose that the number of acquired periventricular lesions be increased from one to three to provide additional specificity. “We reviewed those data … and felt that the modest increase in specificity did not justify making the change,” Dr. Cohen said. The panel also discussed incorporating optic nerve involvement into the criteria, but this proposal was not included in the update.

“The 2017 revisions further refine the well-established McDonald criteria,” Dr. Cohen said. “The appropriate application of the criteria is critical to avoid misdiagnosis. Fundamentally, MS remains a clinical diagnosis. … It requires rigorous synthesis of clinical, imaging, and laboratory data by a clinician with expertise in MS.”

Making a Diagnosis Sooner

Neurologists have been diagnosing MS in patients sooner. At the same time, misdiagnosing other conditions as MS can have profound consequences, including the potentially serious side effects of disease-modifying therapy, said Jeremy Chataway, PhD, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, in a lecture about the application of the proposed criteria. He described cases in which the 2017 proposed criteria—by allowing the inclusion of a symptomatic spinal cord lesion, or by substituting CSF-specific oligoclonal bands in place of dissemination in time—would have allowed neurologists to diagnose MS sooner. In one case, a patient might have received a diagnosis of MS about two years earlier.

Sometimes a diagnosis of MS “is obvious,” Dr. Chataway said. “Sometimes it is hard, even with advanced MRI. You can see the gradation that is required … to get us to the correct diagnosis.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292-302.

Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: A multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

PARIS—Recommended revisions to the 2010 McDonald diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) include changes that are intended to enable neurologists to diagnose MS sooner in patients with a high likelihood of the disease. One addition allows the use of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands in lieu of demonstration of dissemination in time to make a diagnosis of MS in patients with a clinically isolated syndrome and demonstration of dissemination in space clinically or by MRI. Symptomatic and cortical lesions also may satisfy diagnostic criteria, according to the recommendations. In addition, the revised criteria include guidance to reduce the risk of misdiagnosing MS.

Jeffrey A. Cohen, MD, a neurologist with the Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, presented the 2017 proposed revisions at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

Dr. Cohen and Alan J. Thompson, MD, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, cochaired the International Panel on Diagnosis of MS, which drafted the new recommendations. The panel convened in November 2016 and May 2017. The meetings were organized under the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in MS and supported by the US National MS Society and the European Committee for Treatment and Research in MS (ECTRIMS). The panel’s recommendations have been submitted for publication and are in the late stages of revision, Dr. Cohen said.

Facilitate Diagnosis

New data regarding the utility of MRI, CSF, and other tests in the diagnostic process motivated neurologists to reconvene the panel. In addition, “there has been increasing recognition of the continued frequency and potential consequences of misdiagnosis of MS,” Dr. Cohen said.

“We felt that the 2010 McDonald criteria overall performed well,” he said. “We did not anticipate making major changes to the criteria. But we sought to simplify and clarify some of the components of the 2010 criteria. We wanted to facilitate the ability to make the diagnosis of MS in patients who had a high likelihood of the disease but were not currently diagnosable by the 2010 criteria. We wanted to preserve the specificity of the 2010 criteria but promote their appropriate application … to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis.” Finally, the panel “wanted to ensure that any proposed changes did not weaken the existing criteria and were supported by reasonable evidence,” he said. Dr. Cohen highlighted five of the panel’s key revisions.

Recommended Changes

First and probably most controversially, “we propose that in a patient with a typical clinically isolated syndrome, and with fulfillment by either clinical or MRI criteria for dissemination in space, that the presence of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands now allows for diagnosis of MS,” Dr. Cohen said. “It does not represent demonstration of dissemination in time per se, but it allows substitution for demonstration of dissemination in time.”

A second recommendation is that symptomatic and asymptomatic MRI lesions can be considered in the determination of dissemination in space and time. In the 2010 criteria, a symptomatic lesion in a patient with a brainstem or spinal cord syndrome could not be included as MRI evidence of dissemination in time and space.

Third, in addition to juxtacortical lesions, cortical lesions can demonstrate dissemination in space. Neurologists’ ability to detect purely cortical MRI

Fourth, the criteria for primary progressive MS now allow the inclusion of symptomatic and cortical lesions as evidence of the disease. These criteria otherwise have not changed.

Finally, the panel recommends that neurologists determine a provisional disease course, as specified by Lublin et al, at the time of diagnosis and then periodically reevaluate the provisional course based on accumulated evidence.

Avoiding Misdiagnosis

“Much of our discussion started with the issue of misdiagnosis and differential diagnosis in MS,” Dr. Cohen said. “The potential differential diagnosis of MS is quite broad, and misdiagnosis remains an issue even today with advancements in MRI and other testing.” Solomon et al found that neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSDs) were the disorders most commonly misdiagnosed as MS. Physicians also misdiagnosed common conditions like migraine as MS. “Misdiagnosis may have harmful consequences, including inappropriate institution of disease therapy,” Dr. Cohen said.

Neurologists now recognize that aquaporin 4–related NMOSD is a distinct disorder from MS. “However, if you think back to the time that the 2010 criteria were developed, the relationship between NMOSD and MS was not quite as clear. Substantial data have been published since that time,” Dr. Cohen said. “We agreed that the McDonald criteria and the formal criteria for NMOSD largely distinguish the two diseases. However, there may be cases in which there is some uncertainty. Our recommendation is that … the possibility of NMOSD should be considered in all patients being evaluated for MS,” and any patient with features suggesting NMOSD should undergo aquaporin 4 testing.

In general, neurologists should recognize that the McDonald criteria originally were developed to make the diagnosis of MS in patients who have a high likelihood of the disease, not to differentiate MS from other disorders, he said. “Historical events being taken to represent a prior attack should be interpreted with caution if there is no corroborating objective evidence,” Dr. Cohen said. “In cases in which the diagnosis of MS is uncertain, further testing should be pursued. And in some cases, a clinician may want to postpone making a diagnosis pending the accumulation of sufficient data.” CSF testing and spinal MRI are not required to make the diagnosis of MS, but there should be a low threshold for obtaining them.

While data generally support the validity of the 2010 McDonald criteria in geographically diverse populations, children, and older individuals, neurologists should address potentially relevant alternative diagnoses that may be more common in these and other populations (eg, patients with comorbidities), such as infections and nutritional deficiencies.

MAGNIMS Proposal

Several proposals generated discussion during the panel meetings but were not adopted, primarily because the evidence did not justify changing the current criteria. For instance, the 2016 MAGNIMS MRI criteria propose that the number of acquired periventricular lesions be increased from one to three to provide additional specificity. “We reviewed those data … and felt that the modest increase in specificity did not justify making the change,” Dr. Cohen said. The panel also discussed incorporating optic nerve involvement into the criteria, but this proposal was not included in the update.

“The 2017 revisions further refine the well-established McDonald criteria,” Dr. Cohen said. “The appropriate application of the criteria is critical to avoid misdiagnosis. Fundamentally, MS remains a clinical diagnosis. … It requires rigorous synthesis of clinical, imaging, and laboratory data by a clinician with expertise in MS.”

Making a Diagnosis Sooner

Neurologists have been diagnosing MS in patients sooner. At the same time, misdiagnosing other conditions as MS can have profound consequences, including the potentially serious side effects of disease-modifying therapy, said Jeremy Chataway, PhD, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, in a lecture about the application of the proposed criteria. He described cases in which the 2017 proposed criteria—by allowing the inclusion of a symptomatic spinal cord lesion, or by substituting CSF-specific oligoclonal bands in place of dissemination in time—would have allowed neurologists to diagnose MS sooner. In one case, a patient might have received a diagnosis of MS about two years earlier.

Sometimes a diagnosis of MS “is obvious,” Dr. Chataway said. “Sometimes it is hard, even with advanced MRI. You can see the gradation that is required … to get us to the correct diagnosis.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292-302.

Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: A multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

‘Tea with Freud’: Engaging, authentic, but nonanalytic

If I traveled back in time to meet with a 60-year-old Sigmund Freud, the first thing I would say to him is: “Stop smoking, and get out of Austria!”

That was my thought as I read “Tea with Freud: An Imaginary Conversation about How Psychotherapy Really Works” (Dog Ear Publishing, 2016), in which the author, psychiatrist Steven B. Sandler, MD, holds a series of imaginary meetings with Freud to discuss the evolution of psychoanalysis into Sandler’s preferred mode of short-term dynamic psychotherapy (STDP) and to present case material for Freud’s supervision.

The chapters in “Tea with Freud” alternate between the imagined meetings with Freud and Sandler’s clinical work, presented from what I assume are transcripts of videotaped sessions with some disguises and composites to protect patients’ privacy. These clinical vignettes bring the reader into the nitty-gritty of the treatment room, which may be highly instructive for a lay person – particularly one who has never been in therapy.

At the same time, the book has the potential to be quite misleading. This would not be the case if Sandler were simply trying to introduce the reader to STDP. Instead, he attempts to convince the reader, and apparently himself, that the therapy he practices is a modern rendition of psychoanalysis because it tries to access the patient’s unacceptable, unconscious feelings; encourages her to “remember with emotion” or “experience” her feelings; and leads to some sort of cathartic resolution and improvement in symptoms and outlook.

While, “Aha!” moments and cathartic abreaction were characteristic of very early analyses, modern psychoanalysis is about slow but permanent change in character structure. The unwritten message in the book is that Freud’s true heirs practice psychotherapy as Sandler does. He does not seem to consider the significance of the many psychoanalysts, myself included, practicing psychoanalysis today.

Sandler uses a (mercifully) attenuated Davanloo technique to provoke patients into dramatic enactments. He is highly directive, with statements like, “We don’t solve any particular problem if we jump around all over.” I wonder how he can possibly learn about his patients when he begins with a foregone conclusion about where they should be headed.

His treatments are very brief. During his first session with a patient named Carla, he deduces that she is suffering from unresolved anger related to childhood trauma and manifesting it in chronic anxiety with angry outbursts. He then proceeds to “cure” her in five sessions.

Sandler wonders why some of his patients relapse and decides it is because they have not explored their “positive memories” in treatment, as though memories were univalent.

And he talks way too much.

All of this is decidedly un-analytic, which, again, would not matter if he were only trying to demonstrate STDP in action. Nonanalytic psychotherapies are entitled to be nonanalytic. Sandler has Freud point out precisely these analytic errors, so he must be aware that he is making them. And, yet, he stubbornly maintains his position that his work is analytic. What a waste of time travel it would be to meet with Freud only to reinforce one’s own opinions.

“Tea with Freud” is a way for Sandler to promote STDP and his theories about “positive memories” using an established authority, Freud, to validate them. This makes the book disappointing, but fortunately, there is something more to it. I kept wondering why it was so important to the author to seek out Freud’s – that is, his father’s – approval for his work. The book never answers that question. But in his attempts to understand his motives, Sandler, who is very adept at describing his own thoughts and feelings, becomes a model for the awareness of internal states and the effects of unconscious processes. Perhaps this is the most important lesson in “Tea with Freud.”

Dr. Twersky-Kengmana is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice in New York.

If I traveled back in time to meet with a 60-year-old Sigmund Freud, the first thing I would say to him is: “Stop smoking, and get out of Austria!”

That was my thought as I read “Tea with Freud: An Imaginary Conversation about How Psychotherapy Really Works” (Dog Ear Publishing, 2016), in which the author, psychiatrist Steven B. Sandler, MD, holds a series of imaginary meetings with Freud to discuss the evolution of psychoanalysis into Sandler’s preferred mode of short-term dynamic psychotherapy (STDP) and to present case material for Freud’s supervision.

The chapters in “Tea with Freud” alternate between the imagined meetings with Freud and Sandler’s clinical work, presented from what I assume are transcripts of videotaped sessions with some disguises and composites to protect patients’ privacy. These clinical vignettes bring the reader into the nitty-gritty of the treatment room, which may be highly instructive for a lay person – particularly one who has never been in therapy.

At the same time, the book has the potential to be quite misleading. This would not be the case if Sandler were simply trying to introduce the reader to STDP. Instead, he attempts to convince the reader, and apparently himself, that the therapy he practices is a modern rendition of psychoanalysis because it tries to access the patient’s unacceptable, unconscious feelings; encourages her to “remember with emotion” or “experience” her feelings; and leads to some sort of cathartic resolution and improvement in symptoms and outlook.

While, “Aha!” moments and cathartic abreaction were characteristic of very early analyses, modern psychoanalysis is about slow but permanent change in character structure. The unwritten message in the book is that Freud’s true heirs practice psychotherapy as Sandler does. He does not seem to consider the significance of the many psychoanalysts, myself included, practicing psychoanalysis today.

Sandler uses a (mercifully) attenuated Davanloo technique to provoke patients into dramatic enactments. He is highly directive, with statements like, “We don’t solve any particular problem if we jump around all over.” I wonder how he can possibly learn about his patients when he begins with a foregone conclusion about where they should be headed.

His treatments are very brief. During his first session with a patient named Carla, he deduces that she is suffering from unresolved anger related to childhood trauma and manifesting it in chronic anxiety with angry outbursts. He then proceeds to “cure” her in five sessions.

Sandler wonders why some of his patients relapse and decides it is because they have not explored their “positive memories” in treatment, as though memories were univalent.

And he talks way too much.

All of this is decidedly un-analytic, which, again, would not matter if he were only trying to demonstrate STDP in action. Nonanalytic psychotherapies are entitled to be nonanalytic. Sandler has Freud point out precisely these analytic errors, so he must be aware that he is making them. And, yet, he stubbornly maintains his position that his work is analytic. What a waste of time travel it would be to meet with Freud only to reinforce one’s own opinions.

“Tea with Freud” is a way for Sandler to promote STDP and his theories about “positive memories” using an established authority, Freud, to validate them. This makes the book disappointing, but fortunately, there is something more to it. I kept wondering why it was so important to the author to seek out Freud’s – that is, his father’s – approval for his work. The book never answers that question. But in his attempts to understand his motives, Sandler, who is very adept at describing his own thoughts and feelings, becomes a model for the awareness of internal states and the effects of unconscious processes. Perhaps this is the most important lesson in “Tea with Freud.”

Dr. Twersky-Kengmana is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice in New York.

If I traveled back in time to meet with a 60-year-old Sigmund Freud, the first thing I would say to him is: “Stop smoking, and get out of Austria!”

That was my thought as I read “Tea with Freud: An Imaginary Conversation about How Psychotherapy Really Works” (Dog Ear Publishing, 2016), in which the author, psychiatrist Steven B. Sandler, MD, holds a series of imaginary meetings with Freud to discuss the evolution of psychoanalysis into Sandler’s preferred mode of short-term dynamic psychotherapy (STDP) and to present case material for Freud’s supervision.

The chapters in “Tea with Freud” alternate between the imagined meetings with Freud and Sandler’s clinical work, presented from what I assume are transcripts of videotaped sessions with some disguises and composites to protect patients’ privacy. These clinical vignettes bring the reader into the nitty-gritty of the treatment room, which may be highly instructive for a lay person – particularly one who has never been in therapy.

At the same time, the book has the potential to be quite misleading. This would not be the case if Sandler were simply trying to introduce the reader to STDP. Instead, he attempts to convince the reader, and apparently himself, that the therapy he practices is a modern rendition of psychoanalysis because it tries to access the patient’s unacceptable, unconscious feelings; encourages her to “remember with emotion” or “experience” her feelings; and leads to some sort of cathartic resolution and improvement in symptoms and outlook.

While, “Aha!” moments and cathartic abreaction were characteristic of very early analyses, modern psychoanalysis is about slow but permanent change in character structure. The unwritten message in the book is that Freud’s true heirs practice psychotherapy as Sandler does. He does not seem to consider the significance of the many psychoanalysts, myself included, practicing psychoanalysis today.

Sandler uses a (mercifully) attenuated Davanloo technique to provoke patients into dramatic enactments. He is highly directive, with statements like, “We don’t solve any particular problem if we jump around all over.” I wonder how he can possibly learn about his patients when he begins with a foregone conclusion about where they should be headed.

His treatments are very brief. During his first session with a patient named Carla, he deduces that she is suffering from unresolved anger related to childhood trauma and manifesting it in chronic anxiety with angry outbursts. He then proceeds to “cure” her in five sessions.

Sandler wonders why some of his patients relapse and decides it is because they have not explored their “positive memories” in treatment, as though memories were univalent.

And he talks way too much.

All of this is decidedly un-analytic, which, again, would not matter if he were only trying to demonstrate STDP in action. Nonanalytic psychotherapies are entitled to be nonanalytic. Sandler has Freud point out precisely these analytic errors, so he must be aware that he is making them. And, yet, he stubbornly maintains his position that his work is analytic. What a waste of time travel it would be to meet with Freud only to reinforce one’s own opinions.

“Tea with Freud” is a way for Sandler to promote STDP and his theories about “positive memories” using an established authority, Freud, to validate them. This makes the book disappointing, but fortunately, there is something more to it. I kept wondering why it was so important to the author to seek out Freud’s – that is, his father’s – approval for his work. The book never answers that question. But in his attempts to understand his motives, Sandler, who is very adept at describing his own thoughts and feelings, becomes a model for the awareness of internal states and the effects of unconscious processes. Perhaps this is the most important lesson in “Tea with Freud.”

Dr. Twersky-Kengmana is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice in New York.

Accounting 101: Basics you need to know

Physicians practice medicine and communicate within the world of medical language, yet there is a lack of awareness and understanding by many health care professionals of the universal language of business, which is accounting. Just as Latin provides the basic framework for medically related terminology, accounting is the standard language used to convey financial information to both internal and external stakeholders.

Accounting principles are important to physicians at any level. Whether you are starting out in private practice, running a clinical department, or working as an executive in a health care system, most decisions are based on the interpretation of financial data using accounting principles. Accounting standards in the United States are developed by the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) and established as a set of principles and guidelines called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).1–3

Accrual- vs cash-based accounting

There are 2 approaches to recording financial transactions: accrual- and cash-based accounting methods. The main difference between them is in the timing of the recorded financial transactions (when revenue and expenses are recognized on the accounting books). Under GAAP, the matching principle, which is one of the most basic and utilized guidelines of accounting, specifies that accrual accounting be used. In the United States, most businesses (publically traded companies and moderate- to large-sized companies) use accrual accounting, while some individual and smaller businesses, including health care services such as physician practices, use the cash method.1–4

Accrual-based accounting

Accrual-based accounting specifies that revenues are recorded when they are earned, and expenses are recorded when they occur. A health care business may earn revenue for services on one day, but the cash may not be received or recorded on the accounting books for several weeks or months and at an amount less than billed.

Accrual-based accounting provides a more accurate representation of a business’ financial performance, since it uses the principle in which expenses are matched to revenues in the same time period. This enables a more precise representation of true financial performance during a given time frame.1–4

Cash-based accounting

Cash-based accounting is the easiest method to understand and implement because financial transactions are recorded in the accounting books when money is received or spent without the need for complex accounting techniques or integration of accounts receivable or payable.

Despite the ease of use and simplicity in tracking cash flow, this method can be deceiving because revenue may be received or expenses may need to be paid at times that are not consistent with when the revenue has been earned or expenses incurred. This can result in misleading information on the business’ health and the accuracy of tracking financial performance over time, since revenue and expenses for a particular transaction may occur at different times.1–4

Which accounting process to choose?

Even though accrual-based accounting may provide a more accurate financial representation of a business’ performance, many smaller businesses, including physician practices, prefer to use cash-based accounting. In addition, many health care businesses are eligible to use cash-based accounting per Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules by qualifying for the Gross Receipts Test and being a qualified Personal Service Corporation (PSC):

- The Gross Receipts Test states that if the average annual gross receipts of the business are less than $5 million, the business can use the cash-based accounting method.

- If at least 95% of a business activity involves performing health care services, and at least 95% of the business is owned by employees performing health care services, then the business qualifies as a PSC that may use the cash-based accounting method.

Many physician practices qualify to use cash-based accounting, which reduces the complexity of following accrual-based accounting rules and simplifies overall cash-flow management.5

Read about insurance, capital equipment depreciation, more

CASE New practice opens

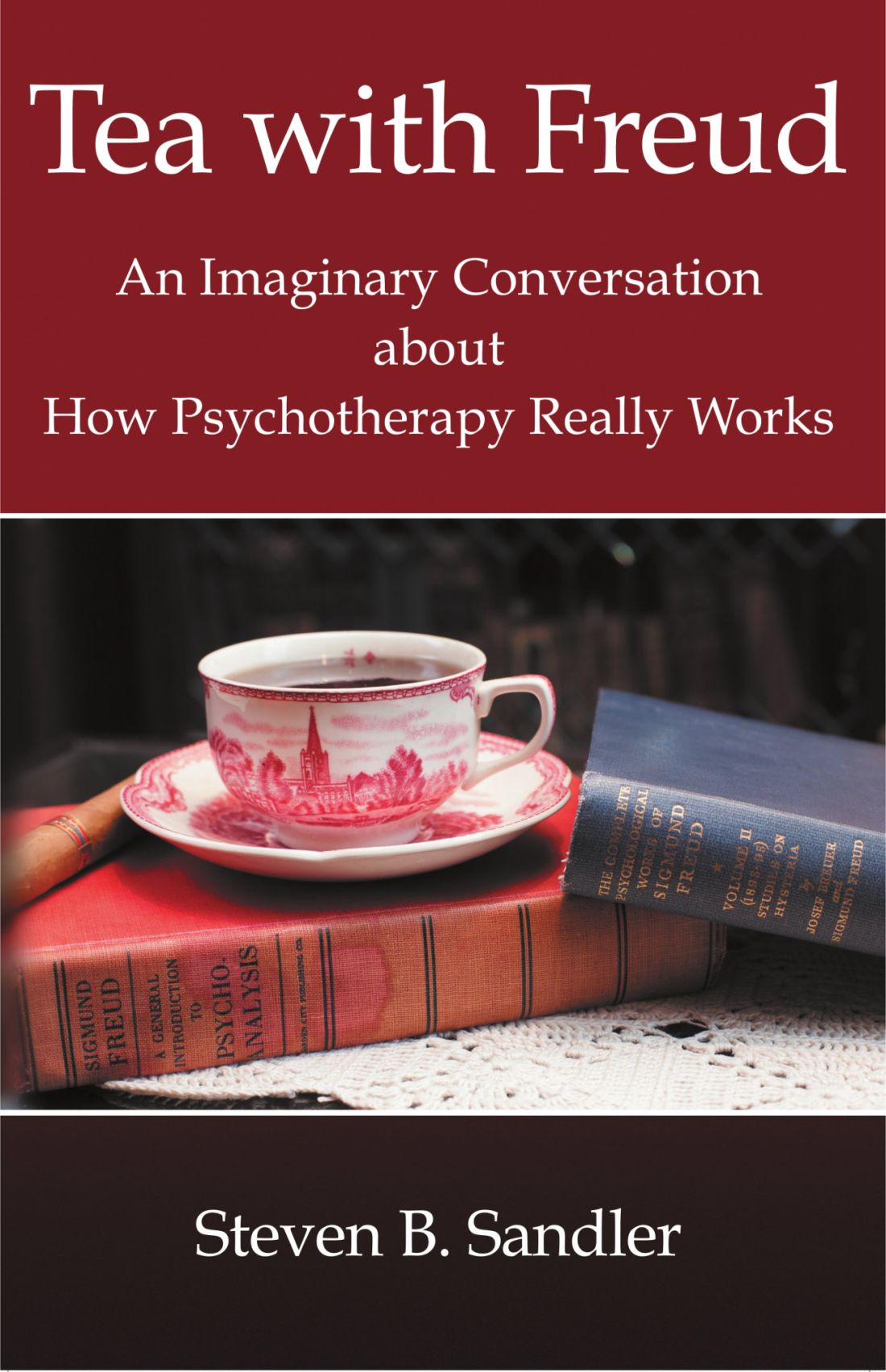

Practice A opens its practice on January 1. The practice borrows $20,000 from the bank to purchase hysteroscopic equipment for office-based tubal sterilizations and an additional $50,000 for an ultrasound machine. Both loans have a 5% annual interest rate amortized over 5 years. The practice leases office space and pays rent 2 months in advance at $8,000 ($4,000 per month). On January 1, the practice pays a $1,200 premium for annual property and liability insurance and $12,500 for the first quarter payment for professional liability insurance ($50,000 annually, paid quarterly). Other costs the practice pays in January include: utilities, $400; EHR licensing, $300; technical support, $200; and salaries, $10,000.

The practice purchases 4 sets of sterilization spring devices at $1,500 each ($6,000) to have in stock. One hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is performed on a patient in January using 1 device. The practice is reimbursed $2,500 for the procedure.

In January, the practice bills $150,000 in charges, but after insurance contractual adjustments, January’s revenue is $50,000. Actual cash payments from billings received are $10,000 in January, $30,000 in February, and $10,000 in March.

At first glance, there is a noticeable difference on the sales or recognition of revenues based on the type of accounting (TABLE). With the accrual method, because the billing charges are submitted in January when the services were provided (minus the insurance contractual adjustments), the $50,000 revenue is immediately counted and recognized, even though the practice only received $10,000 cash for those billings during January. While the benefit to accrual accounting is the timely recognition of the revenue when the service was provided, the downside is that much of those billings might actually be paid over 90 days, and some of those billings may go unpaid by the insurance company or the patients, which would require adjustments in later months.

The cash-based method is simpler to understand because the cash received for the month is recognized as the revenue, regardless of the amount charged that month.

Merchandise. In the accrual method, the cost of merchandise sold (the hysteroscopic sterilization implants) is recognized as an expense when the revenue is generated from its sale. In this case, the date that the patient has the hysteroscopic in-office sterilization procedure is when the revenue and the expense of the implant are recognized.

In a cash-based accounting method, the $6,000 cost of the implants is recognized at the time of purchase in January.

Lease. In this scenario, even though 2 months of lease for the office were paid, the accrual method only recognizes the January payment; the second payment is recognized in February. In the cash method, because both months were paid in January, the total expense of $8,000 is recognized in January.

Property liability insurance. The property liability insurance payment is required at the start of the year. In accrual accounting, this expense is divided over 12 months, while in the cash method, the expense is counted at the time the payment is made.

Professional liability insurance. The professional liability insurance expense of $50,000 per year is made in quarterly payments, so for the accrual method, the annual amount would be distributed over 12 months at $4,200 per month. With the cash method, it would be paid—and recognized as an expense—quarterly at $12,500, starting in January.

Capital equipment depreciation. Capital medical equipment (hysteroscopy and ultrasound) can be depreciated using a straight-line 5-year depreciation. A total $70,000 worth of equipment divided by 5 years is $14,000 per year, depreciated over 5 years. One-twelfth of $14,000 equals $1,167, which is recorded as a January depreciation expense. Because the Internal Revenue Code requires capital assets to be depreciated, even for cash-basis taxpayers, the common practice is to record depreciation expense for both cash- and accrual-basis income accounting.6

Interest on loans. A loan’s principal payment will not be included on the income statement. The principal payment, a reduction of a liability (loans payable), is reported on the balance sheet. Only the interest portion of a loan payment is reported on the income statement (interest expense). In accrual accounting, the accrued interest on the loan payment for the year is $3,500 ($292 for January). For the cash-basis method, because the interest is paid annually at year-end, interest will not be expensed until December.

Taxes. The IRS states that, “Individuals, including sole proprietors, partners, and S corporation shareholders, generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $1,000 or more when their return is filed. Corporations generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $500 or more when their return is filed.”7

Assuming 35% tax liability, the accrual method would create a tax liability of $9,744 on a profit of $27,841. With the cash method, there would be no tax liability because there was no net profit.

Other expenses. The utilities, EHR licensing, tech support, and salaries are expensed the same way for both methods.

Net income. The resulting final net income is vastly different for the month of January depending on the accounting method utilized. The accrual method results in a net income of $18,097, while the cash-basis method results in a net loss of $29,767. Over the course of the year, these imbalances are likely to even out.

Related article:

Business law critical to your practice

Choosing an accounting method

Depending on the accounting method, a practice’s performance and profit will seem very different. The type of accounting method chosen will depend on what goals the owners want to achieve.

The accrual method provides a more accurate picture of business flow and performance and will be less subject to monthly variations due to large purchases or variations in expenses. If the practice chooses this method using an income statement, it should also employ a cash-flow statement.

The cash method of accounting will give a convenient and practical summary of the practice’s cash flow.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- About the FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board website. http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/PageSectionPage&cid=1176154526495. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- What is the difference between accrual accounting and cash accounting? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-difference-between-accrual-accounting-and-cash-accounting.asp. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Accounting Basics (Explanation). Part 2: Income Statement. Accounting Coach. https://www.accountingcoach.com/accounting-basics/explanation/2. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Stickney C, Weil R. Financial Accounting: An Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses. 11th ed. Nashville, TN: Southwestern College Publishing Group; 2006:97-110.

- Internal Revenue Service. Publication 538 (12/2016), Accounting Periods and Methods. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p538#en_US_201612_publink1000270634. Revised December 2016. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Klinefelter D, McCorkle D, Klose S. Financial Management: Cash vs. Accrual Accounting. Risk Management. AgriLife Extension. Texas A&M System. http://agrilife.org/agecoext/files/2013/10/rm5-16.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Internal Revenue Service. Small Business and Self-Employed Tax Center: Estimated Taxes. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes. Updated November 2, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017.

Physicians practice medicine and communicate within the world of medical language, yet there is a lack of awareness and understanding by many health care professionals of the universal language of business, which is accounting. Just as Latin provides the basic framework for medically related terminology, accounting is the standard language used to convey financial information to both internal and external stakeholders.

Accounting principles are important to physicians at any level. Whether you are starting out in private practice, running a clinical department, or working as an executive in a health care system, most decisions are based on the interpretation of financial data using accounting principles. Accounting standards in the United States are developed by the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) and established as a set of principles and guidelines called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).1–3

Accrual- vs cash-based accounting

There are 2 approaches to recording financial transactions: accrual- and cash-based accounting methods. The main difference between them is in the timing of the recorded financial transactions (when revenue and expenses are recognized on the accounting books). Under GAAP, the matching principle, which is one of the most basic and utilized guidelines of accounting, specifies that accrual accounting be used. In the United States, most businesses (publically traded companies and moderate- to large-sized companies) use accrual accounting, while some individual and smaller businesses, including health care services such as physician practices, use the cash method.1–4

Accrual-based accounting

Accrual-based accounting specifies that revenues are recorded when they are earned, and expenses are recorded when they occur. A health care business may earn revenue for services on one day, but the cash may not be received or recorded on the accounting books for several weeks or months and at an amount less than billed.

Accrual-based accounting provides a more accurate representation of a business’ financial performance, since it uses the principle in which expenses are matched to revenues in the same time period. This enables a more precise representation of true financial performance during a given time frame.1–4

Cash-based accounting

Cash-based accounting is the easiest method to understand and implement because financial transactions are recorded in the accounting books when money is received or spent without the need for complex accounting techniques or integration of accounts receivable or payable.

Despite the ease of use and simplicity in tracking cash flow, this method can be deceiving because revenue may be received or expenses may need to be paid at times that are not consistent with when the revenue has been earned or expenses incurred. This can result in misleading information on the business’ health and the accuracy of tracking financial performance over time, since revenue and expenses for a particular transaction may occur at different times.1–4

Which accounting process to choose?

Even though accrual-based accounting may provide a more accurate financial representation of a business’ performance, many smaller businesses, including physician practices, prefer to use cash-based accounting. In addition, many health care businesses are eligible to use cash-based accounting per Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules by qualifying for the Gross Receipts Test and being a qualified Personal Service Corporation (PSC):

- The Gross Receipts Test states that if the average annual gross receipts of the business are less than $5 million, the business can use the cash-based accounting method.

- If at least 95% of a business activity involves performing health care services, and at least 95% of the business is owned by employees performing health care services, then the business qualifies as a PSC that may use the cash-based accounting method.

Many physician practices qualify to use cash-based accounting, which reduces the complexity of following accrual-based accounting rules and simplifies overall cash-flow management.5

Read about insurance, capital equipment depreciation, more

CASE New practice opens

Practice A opens its practice on January 1. The practice borrows $20,000 from the bank to purchase hysteroscopic equipment for office-based tubal sterilizations and an additional $50,000 for an ultrasound machine. Both loans have a 5% annual interest rate amortized over 5 years. The practice leases office space and pays rent 2 months in advance at $8,000 ($4,000 per month). On January 1, the practice pays a $1,200 premium for annual property and liability insurance and $12,500 for the first quarter payment for professional liability insurance ($50,000 annually, paid quarterly). Other costs the practice pays in January include: utilities, $400; EHR licensing, $300; technical support, $200; and salaries, $10,000.

The practice purchases 4 sets of sterilization spring devices at $1,500 each ($6,000) to have in stock. One hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is performed on a patient in January using 1 device. The practice is reimbursed $2,500 for the procedure.

In January, the practice bills $150,000 in charges, but after insurance contractual adjustments, January’s revenue is $50,000. Actual cash payments from billings received are $10,000 in January, $30,000 in February, and $10,000 in March.

At first glance, there is a noticeable difference on the sales or recognition of revenues based on the type of accounting (TABLE). With the accrual method, because the billing charges are submitted in January when the services were provided (minus the insurance contractual adjustments), the $50,000 revenue is immediately counted and recognized, even though the practice only received $10,000 cash for those billings during January. While the benefit to accrual accounting is the timely recognition of the revenue when the service was provided, the downside is that much of those billings might actually be paid over 90 days, and some of those billings may go unpaid by the insurance company or the patients, which would require adjustments in later months.

The cash-based method is simpler to understand because the cash received for the month is recognized as the revenue, regardless of the amount charged that month.

Merchandise. In the accrual method, the cost of merchandise sold (the hysteroscopic sterilization implants) is recognized as an expense when the revenue is generated from its sale. In this case, the date that the patient has the hysteroscopic in-office sterilization procedure is when the revenue and the expense of the implant are recognized.

In a cash-based accounting method, the $6,000 cost of the implants is recognized at the time of purchase in January.

Lease. In this scenario, even though 2 months of lease for the office were paid, the accrual method only recognizes the January payment; the second payment is recognized in February. In the cash method, because both months were paid in January, the total expense of $8,000 is recognized in January.

Property liability insurance. The property liability insurance payment is required at the start of the year. In accrual accounting, this expense is divided over 12 months, while in the cash method, the expense is counted at the time the payment is made.

Professional liability insurance. The professional liability insurance expense of $50,000 per year is made in quarterly payments, so for the accrual method, the annual amount would be distributed over 12 months at $4,200 per month. With the cash method, it would be paid—and recognized as an expense—quarterly at $12,500, starting in January.

Capital equipment depreciation. Capital medical equipment (hysteroscopy and ultrasound) can be depreciated using a straight-line 5-year depreciation. A total $70,000 worth of equipment divided by 5 years is $14,000 per year, depreciated over 5 years. One-twelfth of $14,000 equals $1,167, which is recorded as a January depreciation expense. Because the Internal Revenue Code requires capital assets to be depreciated, even for cash-basis taxpayers, the common practice is to record depreciation expense for both cash- and accrual-basis income accounting.6

Interest on loans. A loan’s principal payment will not be included on the income statement. The principal payment, a reduction of a liability (loans payable), is reported on the balance sheet. Only the interest portion of a loan payment is reported on the income statement (interest expense). In accrual accounting, the accrued interest on the loan payment for the year is $3,500 ($292 for January). For the cash-basis method, because the interest is paid annually at year-end, interest will not be expensed until December.

Taxes. The IRS states that, “Individuals, including sole proprietors, partners, and S corporation shareholders, generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $1,000 or more when their return is filed. Corporations generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $500 or more when their return is filed.”7

Assuming 35% tax liability, the accrual method would create a tax liability of $9,744 on a profit of $27,841. With the cash method, there would be no tax liability because there was no net profit.

Other expenses. The utilities, EHR licensing, tech support, and salaries are expensed the same way for both methods.

Net income. The resulting final net income is vastly different for the month of January depending on the accounting method utilized. The accrual method results in a net income of $18,097, while the cash-basis method results in a net loss of $29,767. Over the course of the year, these imbalances are likely to even out.

Related article:

Business law critical to your practice

Choosing an accounting method

Depending on the accounting method, a practice’s performance and profit will seem very different. The type of accounting method chosen will depend on what goals the owners want to achieve.

The accrual method provides a more accurate picture of business flow and performance and will be less subject to monthly variations due to large purchases or variations in expenses. If the practice chooses this method using an income statement, it should also employ a cash-flow statement.

The cash method of accounting will give a convenient and practical summary of the practice’s cash flow.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Physicians practice medicine and communicate within the world of medical language, yet there is a lack of awareness and understanding by many health care professionals of the universal language of business, which is accounting. Just as Latin provides the basic framework for medically related terminology, accounting is the standard language used to convey financial information to both internal and external stakeholders.

Accounting principles are important to physicians at any level. Whether you are starting out in private practice, running a clinical department, or working as an executive in a health care system, most decisions are based on the interpretation of financial data using accounting principles. Accounting standards in the United States are developed by the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) and established as a set of principles and guidelines called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).1–3

Accrual- vs cash-based accounting

There are 2 approaches to recording financial transactions: accrual- and cash-based accounting methods. The main difference between them is in the timing of the recorded financial transactions (when revenue and expenses are recognized on the accounting books). Under GAAP, the matching principle, which is one of the most basic and utilized guidelines of accounting, specifies that accrual accounting be used. In the United States, most businesses (publically traded companies and moderate- to large-sized companies) use accrual accounting, while some individual and smaller businesses, including health care services such as physician practices, use the cash method.1–4

Accrual-based accounting

Accrual-based accounting specifies that revenues are recorded when they are earned, and expenses are recorded when they occur. A health care business may earn revenue for services on one day, but the cash may not be received or recorded on the accounting books for several weeks or months and at an amount less than billed.

Accrual-based accounting provides a more accurate representation of a business’ financial performance, since it uses the principle in which expenses are matched to revenues in the same time period. This enables a more precise representation of true financial performance during a given time frame.1–4

Cash-based accounting

Cash-based accounting is the easiest method to understand and implement because financial transactions are recorded in the accounting books when money is received or spent without the need for complex accounting techniques or integration of accounts receivable or payable.

Despite the ease of use and simplicity in tracking cash flow, this method can be deceiving because revenue may be received or expenses may need to be paid at times that are not consistent with when the revenue has been earned or expenses incurred. This can result in misleading information on the business’ health and the accuracy of tracking financial performance over time, since revenue and expenses for a particular transaction may occur at different times.1–4

Which accounting process to choose?

Even though accrual-based accounting may provide a more accurate financial representation of a business’ performance, many smaller businesses, including physician practices, prefer to use cash-based accounting. In addition, many health care businesses are eligible to use cash-based accounting per Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules by qualifying for the Gross Receipts Test and being a qualified Personal Service Corporation (PSC):

- The Gross Receipts Test states that if the average annual gross receipts of the business are less than $5 million, the business can use the cash-based accounting method.

- If at least 95% of a business activity involves performing health care services, and at least 95% of the business is owned by employees performing health care services, then the business qualifies as a PSC that may use the cash-based accounting method.

Many physician practices qualify to use cash-based accounting, which reduces the complexity of following accrual-based accounting rules and simplifies overall cash-flow management.5

Read about insurance, capital equipment depreciation, more

CASE New practice opens

Practice A opens its practice on January 1. The practice borrows $20,000 from the bank to purchase hysteroscopic equipment for office-based tubal sterilizations and an additional $50,000 for an ultrasound machine. Both loans have a 5% annual interest rate amortized over 5 years. The practice leases office space and pays rent 2 months in advance at $8,000 ($4,000 per month). On January 1, the practice pays a $1,200 premium for annual property and liability insurance and $12,500 for the first quarter payment for professional liability insurance ($50,000 annually, paid quarterly). Other costs the practice pays in January include: utilities, $400; EHR licensing, $300; technical support, $200; and salaries, $10,000.

The practice purchases 4 sets of sterilization spring devices at $1,500 each ($6,000) to have in stock. One hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is performed on a patient in January using 1 device. The practice is reimbursed $2,500 for the procedure.

In January, the practice bills $150,000 in charges, but after insurance contractual adjustments, January’s revenue is $50,000. Actual cash payments from billings received are $10,000 in January, $30,000 in February, and $10,000 in March.

At first glance, there is a noticeable difference on the sales or recognition of revenues based on the type of accounting (TABLE). With the accrual method, because the billing charges are submitted in January when the services were provided (minus the insurance contractual adjustments), the $50,000 revenue is immediately counted and recognized, even though the practice only received $10,000 cash for those billings during January. While the benefit to accrual accounting is the timely recognition of the revenue when the service was provided, the downside is that much of those billings might actually be paid over 90 days, and some of those billings may go unpaid by the insurance company or the patients, which would require adjustments in later months.

The cash-based method is simpler to understand because the cash received for the month is recognized as the revenue, regardless of the amount charged that month.

Merchandise. In the accrual method, the cost of merchandise sold (the hysteroscopic sterilization implants) is recognized as an expense when the revenue is generated from its sale. In this case, the date that the patient has the hysteroscopic in-office sterilization procedure is when the revenue and the expense of the implant are recognized.

In a cash-based accounting method, the $6,000 cost of the implants is recognized at the time of purchase in January.

Lease. In this scenario, even though 2 months of lease for the office were paid, the accrual method only recognizes the January payment; the second payment is recognized in February. In the cash method, because both months were paid in January, the total expense of $8,000 is recognized in January.

Property liability insurance. The property liability insurance payment is required at the start of the year. In accrual accounting, this expense is divided over 12 months, while in the cash method, the expense is counted at the time the payment is made.

Professional liability insurance. The professional liability insurance expense of $50,000 per year is made in quarterly payments, so for the accrual method, the annual amount would be distributed over 12 months at $4,200 per month. With the cash method, it would be paid—and recognized as an expense—quarterly at $12,500, starting in January.

Capital equipment depreciation. Capital medical equipment (hysteroscopy and ultrasound) can be depreciated using a straight-line 5-year depreciation. A total $70,000 worth of equipment divided by 5 years is $14,000 per year, depreciated over 5 years. One-twelfth of $14,000 equals $1,167, which is recorded as a January depreciation expense. Because the Internal Revenue Code requires capital assets to be depreciated, even for cash-basis taxpayers, the common practice is to record depreciation expense for both cash- and accrual-basis income accounting.6

Interest on loans. A loan’s principal payment will not be included on the income statement. The principal payment, a reduction of a liability (loans payable), is reported on the balance sheet. Only the interest portion of a loan payment is reported on the income statement (interest expense). In accrual accounting, the accrued interest on the loan payment for the year is $3,500 ($292 for January). For the cash-basis method, because the interest is paid annually at year-end, interest will not be expensed until December.

Taxes. The IRS states that, “Individuals, including sole proprietors, partners, and S corporation shareholders, generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $1,000 or more when their return is filed. Corporations generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $500 or more when their return is filed.”7

Assuming 35% tax liability, the accrual method would create a tax liability of $9,744 on a profit of $27,841. With the cash method, there would be no tax liability because there was no net profit.

Other expenses. The utilities, EHR licensing, tech support, and salaries are expensed the same way for both methods.

Net income. The resulting final net income is vastly different for the month of January depending on the accounting method utilized. The accrual method results in a net income of $18,097, while the cash-basis method results in a net loss of $29,767. Over the course of the year, these imbalances are likely to even out.

Related article:

Business law critical to your practice

Choosing an accounting method

Depending on the accounting method, a practice’s performance and profit will seem very different. The type of accounting method chosen will depend on what goals the owners want to achieve.

The accrual method provides a more accurate picture of business flow and performance and will be less subject to monthly variations due to large purchases or variations in expenses. If the practice chooses this method using an income statement, it should also employ a cash-flow statement.

The cash method of accounting will give a convenient and practical summary of the practice’s cash flow.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- About the FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board website. http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/PageSectionPage&cid=1176154526495. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- What is the difference between accrual accounting and cash accounting? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-difference-between-accrual-accounting-and-cash-accounting.asp. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Accounting Basics (Explanation). Part 2: Income Statement. Accounting Coach. https://www.accountingcoach.com/accounting-basics/explanation/2. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Stickney C, Weil R. Financial Accounting: An Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses. 11th ed. Nashville, TN: Southwestern College Publishing Group; 2006:97-110.

- Internal Revenue Service. Publication 538 (12/2016), Accounting Periods and Methods. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p538#en_US_201612_publink1000270634. Revised December 2016. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Klinefelter D, McCorkle D, Klose S. Financial Management: Cash vs. Accrual Accounting. Risk Management. AgriLife Extension. Texas A&M System. http://agrilife.org/agecoext/files/2013/10/rm5-16.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Internal Revenue Service. Small Business and Self-Employed Tax Center: Estimated Taxes. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes. Updated November 2, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- About the FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board website. http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/PageSectionPage&cid=1176154526495. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- What is the difference between accrual accounting and cash accounting? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-difference-between-accrual-accounting-and-cash-accounting.asp. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Accounting Basics (Explanation). Part 2: Income Statement. Accounting Coach. https://www.accountingcoach.com/accounting-basics/explanation/2. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Stickney C, Weil R. Financial Accounting: An Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses. 11th ed. Nashville, TN: Southwestern College Publishing Group; 2006:97-110.

- Internal Revenue Service. Publication 538 (12/2016), Accounting Periods and Methods. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p538#en_US_201612_publink1000270634. Revised December 2016. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Klinefelter D, McCorkle D, Klose S. Financial Management: Cash vs. Accrual Accounting. Risk Management. AgriLife Extension. Texas A&M System. http://agrilife.org/agecoext/files/2013/10/rm5-16.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Internal Revenue Service. Small Business and Self-Employed Tax Center: Estimated Taxes. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes. Updated November 2, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017.

Inhaled loxapine quells agitation in personality disorders

PARIS – The inhaled powder formulation of loxapine appears to be a safe and effective treatment for acute agitation in patients with personality disorders, Diego R. Mendez Mareque, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Inhaled loxapine is approved for the treatment of acute agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. Its use in patients with borderline personality and other personality disorders is off label. But this inhaled typical antipsychotic shows promise in filling an unmet need for a rapid-acting, minimally invasive treatment for acute agitation in patients with personality disorders, a very common scenario in psychiatric wards and emergency departments, and one that can quickly escalate to aggression and violence, noted Dr. Mendez Mareque of the Galician Health Service in Ferrol, Spain.

He presented a prospective, longitudinal, observational pilot study of 14 patients with personality disorders treated with a single 10-mg dose of inhaled loxapine while experiencing acute agitation in a psychiatric emergency department or psychiatric ward. Their mean baseline score on the Excited Component of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-EC) was 20.8 out of a possible 35 points. The scale assesses five domains: excitement, tension, uncooperativeness, hostility, and poor impulse control.

Within 10 minutes after administration of inhaled loxapine by a health care professional, 11 patients showed a significant drop on the PANSS-EC. They were calm, nonsedated, and ready for assessment. Within 20 minutes, their PANSS-EC scores were reduced by roughly half, compared with baseline.

Three patients were nonresponders. They received rescue treatment with oral or injectable antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.

None of the 14 patients had a history of airway disease, and none experienced bronchospasm, a known possible side effect of inhaled loxapine, the psychiatrist noted.

The results of this Spanish observational study confirm the benefits of inhaled loxapine for treating agitation in patients with borderline personality disorder previously described in a German case series (J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015 Dec;35[6]:741-3).

Dr. Mendez Mareque reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

PARIS – The inhaled powder formulation of loxapine appears to be a safe and effective treatment for acute agitation in patients with personality disorders, Diego R. Mendez Mareque, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Inhaled loxapine is approved for the treatment of acute agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. Its use in patients with borderline personality and other personality disorders is off label. But this inhaled typical antipsychotic shows promise in filling an unmet need for a rapid-acting, minimally invasive treatment for acute agitation in patients with personality disorders, a very common scenario in psychiatric wards and emergency departments, and one that can quickly escalate to aggression and violence, noted Dr. Mendez Mareque of the Galician Health Service in Ferrol, Spain.

He presented a prospective, longitudinal, observational pilot study of 14 patients with personality disorders treated with a single 10-mg dose of inhaled loxapine while experiencing acute agitation in a psychiatric emergency department or psychiatric ward. Their mean baseline score on the Excited Component of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-EC) was 20.8 out of a possible 35 points. The scale assesses five domains: excitement, tension, uncooperativeness, hostility, and poor impulse control.

Within 10 minutes after administration of inhaled loxapine by a health care professional, 11 patients showed a significant drop on the PANSS-EC. They were calm, nonsedated, and ready for assessment. Within 20 minutes, their PANSS-EC scores were reduced by roughly half, compared with baseline.

Three patients were nonresponders. They received rescue treatment with oral or injectable antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.

None of the 14 patients had a history of airway disease, and none experienced bronchospasm, a known possible side effect of inhaled loxapine, the psychiatrist noted.